- 1Educational Research Center, College of Education, Duhail, Qatar

- 2Department of Education Science, College of Education, Duhail, Qatar

- 3The Social and Economic Survey Research Institute, Qatar University, Duhail, Qatar

This study critically examines how English-language newspaper discourse in Qatar and the UAE constructs and legitimizes neoliberal ideologies surrounding higher education institutions and international branch campuses. Drawing on critical theory and critical discourse analysis, we delve into the discourses used in newspaper articles published between 2010 and 2024. We explore the underlying meanings, ideologies, and power relations embedded in the discourses that present institutions of higher education as providers of world-class education and models of best practices. Our findings reveal common themes shared across the two countries, emphasizing commitment to excellence, global leadership, world-class education, and best practices. At the same time, distinctions unique to each are identified, suggesting different approaches to holistic development, diversity, inclusivity, and the importance attributed to international recognition and rankings. This study enriches our understanding of the way neoliberal ideologies permeate discourses, influencing and being influenced by the academic landscape, thus charting new paths for future directions in this area.

1 Introduction

Over the past few decades, higher education (HE) in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region, which comprises Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), has undergone significant transformations. As part of their national development strategies, the six GCC states have launched major reforms aligned with their long-term visions, including Bahrain Vision 2030, Kuwait Vision 2035, Oman Vision 2040, Saudi Vision 2030, and UAE Vision 2021 (Badry, 2019). Central to these visions is the imperative to modernize education systems to meet labor market demands, stimulate economic growth, and foster global competitiveness.

This study examines how English-language newspapers in Qatar and the UAE discursively construct higher education institutions (HEIs) and international branch campuses (IBCs) in ways that reflect state interests. Through a critical analysis of media narratives, it investigates how neoliberal language and framing reinforce dominant ideologies that promote HEIs and IBCs as instruments of economic diversification, social ordering, and global positioning. A key feature of higher education reform in the GCC is its emphasis on internationalization and the pursuit of “world-class” standards. This has led to the proliferation of HEIs, including IBCs affiliated with prestigious Western universities, transforming the region into a global hub for transnational education. These institutions are often portrayed as beacons of innovation and progress, embodying broader neoliberal principles such as globalization, privatization, and marketization (Badry and Willoughby, 2016; Chougule, 2022).

While these institutions are praised for their contributions to human capital development and innovation, their impact on local culture, economy, and society deserves critical scrutiny. This study examines the complex socio-cultural implications of neoliberal higher education models, focusing on the tensions between adopting “world-class” education practices and preserving cultural and educational diversity in a globalized context. By exploring how media discourses shape public perceptions and influence higher education policies in the GCC, the study sheds light on the intersection of neoliberal ideologies, national development goals, and efforts to preserve cultural identity.

While these narratives highlight the role of HEIs and IBCs in advancing human capital and innovation, their broader socio-cultural implications require critical scrutiny. This study explores the tensions between adopting globally recognized education models and preserving cultural identity and educational plurality within the GCC context. By analyzing media discourse, the research aims to reveal how public perceptions are shaped and how policy agendas are discursively legitimized.

Although much scholarly attention has been given to the economic and policy frameworks underpinning higher education reform in the Gulf, the role of media as a discursive actor in this landscape remains under examined. This study addresses that gap by analyzing how state-aligned newspapers frame HEIs and IBCs as exemplars of “world-class” and “best practice” models, consequently sustaining and promoting neoliberal educational reforms in Qatar and the UAE.

The next section sets the stage for the remainder of this paper by outlining the historical and strategic context of higher education reform in the GCC, followed by a review of the literature, situating the discussion within global trends of internationalization, marketization, and neoliberalism, and their influence on HE. It then explains the rationale for employing Critical Theory and Critical Discourse Analysis to examine media representations in Qatar and the UAE. The methodology section describes the research design, data selection, and analytical procedures. Finally, the findings are presented thematically and discussed in relation to the broader implications for higher education and media discourse in the region.

2 Background

The higher education (HE) sector in the GCC region is undergoing profound transformations, mirroring global shifts driven by internationalization, marketization, and neoliberalism. These intersecting forces have redefined the purpose and structure of HE, steering institutions toward global rankings, international partnerships, and performance-based evaluations. Market-oriented reforms have introduced competition among institutions, shaped funding mechanisms, and prioritized employability and economic returns over broader educational values. As a result, academic institutions increasingly operate within quasi-market environments, where privatization and corporate models influence governance, accountability, and strategic priorities. These developments have significant implications for the autonomy, inclusiveness, and cultural orientation of higher education in the region (Zajda and Rust, 2021).

The demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the GCC play a key role in shaping its HE landscape. Rapid population growth and a significant youth bulge have fueled rising demand for HEIs, while the large expatriate population has made English the primary language of instruction. This shift has broadened student diversity, enhanced employability, and increased access to education, yet it has also highlighted gender disparities, evident in the separation of campuses for male and female students. Specifically, female enrolment has surged, with women now making up about two-thirds of the student body in regional universities. Women tend to pursue disciplines such as the social sciences and humanities, a trend influenced by the socio-cultural evolution of women in the GCC and their efforts to reconcile external influences with traditional cultural and religious values (Abdallah, 2021).

Despite advancements in higher education infrastructure and student recruitment, significant challenges persist, particularly in access and affordability, highlighting the need for more equitable and inclusive education systems. In response, GCC governments have actively expanded higher education to align with broader goals of building sustainable, knowledge-based economies (Abu-Shawish et al., 2021). The forces of globalization, internationalization, and neoliberalism have reshaped HE operations and priorities, influencing curricula, student mobility, research collaboration, funding, and governance across GCC states (Badry and Willoughby, 2016; Hall, 2018). However, these shifts have also raised concerns about the commodification of education, academic freedom, cultural preservation, and equitable access.

3 Review of literature

In today’s rapidly evolving world, higher education (HE) is being redefined by global trends such as internationalization, marketization, and neoliberalism. These forces significantly influence the scope and operations of higher education institutions (HEIs), significantly influencing their roles and practices (Tight, 2021; Zajda, 2020). A salient manifestation of this transformation is the expansion of cross-border education, which illustrates the growing importance of global interconnectedness and knowledge exchange in shaping contemporary HE. An important outcome of these developments is the proliferation of IBCs in the GCC region. Countries such as Qatar and the UAE have sought to position themselves as higher education hubs, adopting neoliberal, market-driven strategies to attract foreign investment and elevate their global standing. The introduction of Western, primarily American, models of HE in the GCC has garnered significant attention, highlighting the extent to which global forces are influencing the region’s educational landscape.

Yet, the emphasis on market-oriented excellence in the GCC raises important critical concerns. Butler and Spoelstra argue that academic “excellence” is a performative and ideological construct that privileges competitiveness and conformity to neoliberal norms. These frameworks may compromise academic integrity, limit intellectual diversity, and marginalize local educational values. In the GCC, aligning HE with neoliberal priorities risks favoring Western-centric models at the expense of contextually grounded alternatives. Although scholars have examined the rise of HEIs and IBCs in the region (e.g., Badry and Willoughby, 2016; Chougule, 2022), limited research investigates how these institutions are represented in local media. Furthermore, few studies employ Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to unpack the ideological underpinnings of educational narratives in Gulf newspapers. To address these gaps, this study provides a critical analysis of media discourses surrounding HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE. By examining the representation of these institutions in local newspapers, this research aims to uncover the intersections of global influences, local ideologies, and educational policies in the region’s HE landscape.

3.1 Internationalization, marketization, neoliberalism, and IBCs

In many countries, IBCs have become integral components of HEIs, embodying the global trends of internationalization, marketization, and neoliberalism. The confluence of these developments affects HEIs and IBCs in many ways, including their organizational structures, program offerings, and their broader mission (Ibrahim and Barnawi, 2022). As a result, HEIs and IBCs find themselves facing the challenge of maneuvering through a complex terrain where global perspectives, market forces and neoliberal ideology collectively determine their academic priorities, resource allocation, and overall institutional identity.

3.2 Internationalization

A frequently cited definition of HE internationalization is Knight’s (2003) description: “Internationalizations at the national, sector, and institutional levels is defined as the process of integrating an international, intercultural, or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of post-secondary education” (p. 2). This integration promotes cross-cultural exchange and globalized academic engagement (Clarke and Kirby, 2022). Indeed, IBCs exemplify this trend by offering an avenue for institutions to extend their educational presence abroad, facilitating the exchange of students, faculty, curricula, and knowledge (Sellami et al., 2022).

In the GCC, the internationalization of HE presents both promising opportunities and significant challenges. It contributes to enhancing the global visibility and competitive positioning of HEIs, enabling them to participate more actively in the international academic landscape (Alsharari, 2018). The recruitment of international faculty, the presence of culturally diverse student populations, and the development of cross-border research collaborations foster meaningful intercultural dialogue and facilitate the transfer of knowledge across institutional and national boundaries. Additionally, strategic partnerships with globally recognized universities have played a key role in introducing innovative pedagogical approaches and advanced technologies, thereby enriching teaching and learning practices within local contexts (Pagani et al., 2020).

3.3 Marketization

Marketization embodies the growing influence of market principles, such as competition, privatization, and consumer choice, within HE (Lynch, 2006), thrusting them toward a business-oriented modus operandi. HEIs are not merely viewed as academic extensions but as market entities, competing for students, resources, and prestige. As a result, branding, financial viability, and reputation management become critical institutional priorities.

In the GCC, the expansion of private HEIs and IBCs reflects broader market influences. Institutions compete for student enrolment and scarce resources, often adopting business-like strategies to secure their positions in a competitive marketplace (Hannan and Liu, 2023; Song, 2021). This transformation has redefined HE as a commercial enterprise, where market responsiveness and institutional agility are increasingly emphasized. Institutions find themselves entrapped in a competitive web, wherein success is measured not only by academic excellence but also by the ability to negotiate through interaction among market forces.

3.4 Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism, which advocates for free-markets, privatization, and restrained state intervention, has exerted substantial influence on HE policy (Busch, 2017; Mintz, 2021). As Harvey (2005) contends, neoliberalism is an ideology, sometimes dubbed theory, of political economy is a hegemonic discourse that “proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade.” (p. 2). The core tenets of neoliberalism prioritize financial autonomy, operational efficiency, and adaptability to market demands.

Within the GCC context, neoliberalism has driven HE reforms aligned with economic diversification strategies. Traditionally reliant on oil revenues, these states have reoriented toward knowledge-based economies, emphasizing innovation, research, and skills development (Sellami et al., 2022). Public-private partnerships and the attraction of foreign universities reflect this shift, enabling expanded access, diversified funding, and increased institutional efficiency. Curricula are increasingly aligned with labor market needs, aiming to produce employable graduates. Declining public funding has compelled HEIs to seek alternative revenue sources, while heightened accountability measures ensure alignment with international benchmarks (Anwar et al., 2020). However, as Ong (2006) argues, neoliberalism often coexists with strong state control, producing hybrid models where market logics and state imperatives are selectively combined, which is clearly observable in Qatar and the UAE.

The advent of public-private HE partnerships epitomizes the neoliberal ethos, as these collaborations with private institutions and foreign universities aim to enhance efficiency, diversify funding sources, and expand educational capacities. In the GCC, there is a commitment to embracing a neoliberal approach that prioritizes skills-based education. This involves aligning curricula with market demands, ultimately aiming to foster a workforce that is prepared for employment opportunities. Moreover, the reduction of government funding for HE prompts HEIs to seek alternative financial streams, including tuition fees and external grants. Finally, the neoliberal emphasis on accountability and quality assurance manifests in the implementation of rigorous evaluation mechanisms for universities, faculty, and students, matching educational outcomes with international benchmarks to ensure efficient resource allocation (Anwar et al., 2020).

4 Media, neoliberalism, and public discourse

While neoliberalism provides a useful framework for analyzing global educational transformations, it is not a monolithic ideology. Rather, it intersects with other discourses, including nationalism, managerialism, and developmentalism, resulting in complex and context-specific articulations. In the Gulf, neoliberal logics are often entangled with state-led modernization agendas and national identity-building projects. For example, while market-oriented reforms emphasize privatization and competition, they coexist with strong state regulation and centralized control over education policy and media narratives. These hybrid configurations reflect what Ong (2006) calls “neoliberalism as exception,” where market logics are selectively applied alongside state-centric imperatives. Recognizing these intersections provides a more informed understanding of how neoliberalism is locally embedded and adapted in the Qatari and Emirati higher education contexts.

Although a substantial body of literature has addressed the proliferation of HEIs and IBCs in the region, comparatively less attention has been given to the role of the media in framing these developments. This study addresses that gap by foregrounding how state-aligned newspapers function as discursive instruments that help legitimize neoliberal education models. By examining how these media outlets represent HEIs and IBCs, the study uncovers the discursive strategies through which neoliberal ideologies are normalized and rendered commonsensical within public discourse, potentially influencing both perception and policy.

Apple’s (2004) conceptualization of neoliberalism as a dichotomy – “state = bad/private = good” – offers a useful lens for understanding how privatized and competitive models of higher education are valorized. Indeed, media narratives often advance the desirability of deregulation, privatization, and entrepreneurial logics while downplaying the role of the state in providing equitable, accessible public education. These ideological framings not only shape how higher education institutions are perceived but also reflect broader narratives that endorse market-based solutions as inherently superior.

This interaction is particularly salient in Qatar and the UAE, where media systems are either directly state-controlled or operate within heavily regulated environments. In these contexts, newspapers frequently serve as extensions of official discourse, reflecting state priorities such as attracting foreign investment, maintaining social hierarchies, and promoting intellectual orthodoxy. Our analysis reveals how media discourses on HEIs and IBCs employ market-oriented language and uncritical portrayals to align institutional representations with these strategic state interests.

Contrary to a common assumption that media portrayals of neoliberalism in higher education are inherently critical, the evidence suggests otherwise. Studies have shown that media representations often reinforce neoliberal ideals by promoting the commodification of knowledge and the logic of competition, while eliding structural concerns such as widening inequality, rising tuition fees, and the erosion of academic autonomy (Giroux, 2014; Brown, 2015). Moreover, the literature frequently implies a passive audience, overlooking the interpretive agency of students, educators, and the public, who may contest or reframe dominant media narratives (Mansfield, 2018).

To advance a critical and comprehensive account, it is essential to adopt a multi-faceted approach that examines the interplay between media narratives, political structures, and audience reception. Such an approach not only reveals how media serve to legitimize dominant neoliberal ideologies but also illustrates their potential to act as sites of contestation and critical engagement. As Davies and Bansel (2007) argue, understanding the media’s role in higher education requires attending to how narratives can simultaneously uphold and challenge neoliberal ideals. This duality highlights the complexity of media influence and invites further inquiry into the ways media discourses shape, sustain, or disrupt educational imaginaries in the Gulf.

4.1 International branch campuses in the GCC: gems in the desert?

The need to enhance HE has been driving both government-funded and private H Institutions (HEIs) to invest in education and research, contributing to science, innovation, and overall social and economic development. The adoption of neoliberal models has intensified competition in the HE market in the region, leading to the emergence of “hybrid” public universities that derive significant financial gains from the marketization of teaching and research (Mouwen, 2000, p. 47). The region’s universities are actively commercializing their academic and research activities, emulating successful examples in the West to boost their revenues.

At present, two prominent trends typify HE in the Arab world: privatization and internationalization. Governments are increasingly relying on private HE to achieve strategic national policy goals, focusing on economic development and capacity building. This is apparent in the establishment of education hubs and initiatives to attract international education providers (Lane, 2011). There has been a significant rise in the number of IBCs in the GCC, particularly in comparison to other Arab states. HEIs in the region demonstrate a clear inclination toward recruiting faculty and researchers from Western nations to meet Western accreditation standards.

The vivid and heightened expansion of IBCs in GCC countries is part of a broader trend characterized by the massification and internationalization of HE on a global scale. Concurrent with the fervent pursuit of advanced educational initiatives in these nations is a discernible surge in the establishment of IBCs, commencing notably in the year 2000 (Sellami et al., 2022). Present-day records illustrate that GCC states have accrued a track record of hosting an influx of satellite IBCs, as documented by Colombo and Committeri (2014). This phenomenon is highlighted by the proliferation of diverse foreign – mainly American – branch campuses, engaged in the establishment of branch campuses within the GCC where “the American model runs supreme” (Coffman, 2005, p. 18). As such, the GCC has become what Romani (2009, p. 2) characterizes as the “heavyweight academic actor in the Arab world.”

4.2 Not all that glitters is gold

IBCs have become an integral part of GCC governments’ strategic policy agendas to diversify their economies and foster sustainable, knowledge-based societies (Jafar and Knight, 2020). However, the establishment of IBCs has sparked diverse reactions, span ardent support to vehement criticism. The discourse underpinning IBCs is characterized by a dialectic tension: proponents extol their virtues while skeptics scrutinize potential pitfalls. As the global educational landscape stands at a critical juncture, an informed examination of the implications of IBCs is required to enhance our understanding of the uncharted territories within internationalized HE.

IBCs, strategically positioned across various world regions, serve as catalysts for cultural exchange; they enrich educational experiences by preparing students for an interconnected global society (Jones et al., 2021). Proponents argue that IBCs democratize education by expanding global access to high-quality international academic programs (Hsieh, 2020). These campuses, often affiliated with prestigious institutions, transcend geographical boundaries, facilitating the dissemination of knowledge and fostering inclusive education (Fischer et al., 2021). Beyond education, advocates emphasize IBCs’ potential to foster cross-cultural collaboration and international understanding (Green and Baxter, 2022). Additionally, IBCs contribute to the economic and diplomatic interests of both host and home countries, acting as conduits for investment and promoting international cooperation on multiple fronts (Wilkins, 2020).

5 Theoretical framework

This study draws on Critical Theory (CT) and Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to examine how discourse reflects and perpetuates power relations in the distribution of social goods, including education, health, and other public services, with a particular focus on the portrayal of higher education institutions (HEIs) and international branch campuses (IBCs) in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). CT, rooted in the work of Habermas (1989, 2006), highlights the role of discourse in shaping social structures and critiques the role of commercial mass media in sustaining dominant ideological orders. Within this framework, the study situates neoliberalism as a central force influencing contemporary educational policy, particularly in the Gulf region.

Language is treated as inherently political, functioning not only as a vehicle of communication but also as a mechanism through which ideologies are reproduced and material resources distributed. As Gee (2011) contends, discourse analysis can help us understand “problems and controversies [.] about the distribution of social goods, who gets helped, and who gets harmed” (p. 10). This aligns with the critical sociological perspective that views reality as socially constructed and discourse as a central medium through which dominant narratives, and the interests they serve, are naturalized (Marger, 1993).

Building on this theoretical foundation, the study employs CDA to interrogate how English-language newspapers in Qatar and the UAE discursively frame HEIs and IBCs in ways that legitimize neoliberal reforms. CDA is not used here as a singular, prescriptive method but rather as an assemblage of interrelated analytical approaches that together enable a multi-dimensional exploration of power, ideology, and discourse. Fairclough’s (2003) three-dimensional model guides the analysis of linguistic features, production and consumption practices, and their embeddedness in broader socio-political structures. Van Dijk’s (2006, 2015) socio-cognitive approach informs the study’s attention to how ideological schemata are embedded within textual macrostructures and local meanings. In parallel, Wodak’s (1999) discourse-historical method enables contextualizing these discursive representations within the specific political and institutional histories of the Gulf region.

Together, these approaches enable a detailed and multi-dimensional analysis that goes beyond surface-level representations to interrogate how media discourses actively shape and normalize market-oriented logics within higher education. By linking linguistic choices to broader institutional and ideological structures, the study reveals how dominant narratives in state-aligned newspapers work to legitimize neoliberal reforms as inevitable or desirable. This discursive framing privileges particular policy directions, including privatization, competitiveness, and internationalization, and also obscures alternative educational imaginaries that prioritize equity, public good, or local relevance. In doing so, the media play a central role in sustaining asymmetrical power relations through the naturalization of specific ideologies.

To deepen our understanding of how language functions ideologically in journalistic discourse, this study draws on semiotic traditions rooted in the Prague School, particularly the concepts of markedness theory, foregrounding, functional sentence perspective, and the aesthetic function of language. These principles illuminate how journalistic texts convey information and construct interpretive frameworks by symbolically elevating terms such as “world-class” and “excellence,” while backgrounding alternative lexical choices. This semiotic lens enriches our interpretation of the aestheticization of higher education discourse in Qatar and the UAE, highlighting how such language contributes to the symbolic construction of ideological norms within public discourse (Fowler, 2013; Lo, 2024).

Our analysis focuses on identifying specific discursive mechanisms and practices in newspaper articles that link state strategies with uncritical, neoliberal representations of higher education. We examine how these articles employ market-oriented language to describe educational institutions and outcomes, often framing international partnerships and branch campuses in an unequivocally positive light. Additionally, we explore the emphasis placed on global rankings and competitiveness within these narratives. Our investigation also considers the minimal critical examination of potential cultural or social impacts presented in these articles, as well as the limited representation of diverse voices or perspectives. By examining these discursive practices, we aim to uncover how media narratives reinforce dominant ideologies and state agendas regarding higher education, foreign investment, and social structures in Qatar and the UAE.

Our study extends the application of CT and CDA to the specific context of newspaper representations of HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE. This approach allows us to uncover how media discourses not only reflect but also actively shape public understanding of higher education policies and institutions. By examining the language and rhetoric used in newspaper articles, we can identify the discursive strategies employed to promote certain educational models while potentially marginalizing others. This analysis provides novel insights into the role of media in reinforcing or challenging dominant ideologies in the context of higher education development in the Gulf region. Following Burdett and O’Donnell (2016), we argue that educational systems, as socio-political constructs, embed ideologies via policies, communications, and practices, which reflect broader socio-political and economic influences.

6 Problem statement

Media discourse and rhetoric surrounding HEIs and IBCs in the GCC consistently emphasize their role in promoting economic development and global competitiveness. These narratives serve as powerful tools to justify government investments in these institutions and shape HE policies. However, the alignment of these discourses with neoliberal principles and their potential impact on HE and society remain largely understudied. Our current research critically examines newspaper discourses on HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE.

Existing literature has extensively explored the expansion of HEIs and IBCs in the Gulf region, emphasizing their role in economic diversification and human capital development (e.g., Badry and Willoughby, 2016; Chougule, 2022). However, limited attention has been given to how these institutions are represented in local media, particularly through a critical lens. By interrogating the rhetoric, policies, and practices underpinning these institutions, we seek to unveil the hidden ideologies and interests. Our multidisciplinary approach integrates perspectives from education, sociology, economics, and critical theory to understand the complex relationships between HE, economic development, and neoliberalism in these countries.

Newspapers in the GCC play a key role in shaping public perceptions and influencing policy decisions regarding higher education. As Richter and Kozman (2021) note, media in Qatar and the UAE are predominantly state-controlled or heavily regulated, with censorship and self-censorship shaping the narratives. This regulatory environment is crucial for understanding how newspaper discourses reinforce state agendas and dominant ideologies in HE. By employing critical discourse analysis (CDA), this research reveals how these narratives legitimize certain educational models while potentially marginalizing alternative perspectives.

Using CT and CDA as methodological tools, this study aims to decipher the meanings, ideologies, and power relations embedded in newspaper discourses promoting HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE. Beyond examining the discourses justifying the establishment of HEIs and IBCs, we also investigate the impact of neoliberalism on HE policies and practices in both countries. Ultimately, our analysis will inform discussions on educational reform and policy implementation, and further enhance HE quality in both countries, shedding light on cultural, economic, and political factors shaping educational aspirations.

Newspapers play a significant role in shaping public perception and policy decisions regarding higher education in rapidly developing Gulf nations. As noted by Richter and Kozman (2021), media in Qatar and the UAE are predominantly state-controlled or heavily regulated, with censorship and self-censorship being common practices. This context is crucial for understanding how newspaper discourses may reinforce dominant ideologies and government agendas regarding higher education. While existing research has provided valuable insights into the expansion of HEIs and IBCs in the Gulf region, there are several limitations in the current body of literature. For instance, much of the extant research focuses primarily on the economic and policy aspects of HEI/IBC expansion, often overlooking the crucial role of media in shaping public perception and legitimizing these institutions.

This gap in the literature limits our understanding of how neoliberal ideologies are disseminated and reinforced through public discourse. Moreover, previous studies have largely neglected the application of critical discourse analysis to newspaper narratives about HEIs and IBCs in the Gulf region. This methodological gap has resulted in a lack of in-depth analysis of the ideological underpinnings and power structures embedded in media representations of these institutions. By addressing these gaps, our research complements existing literature and offers novel interpretations of the media’s role in shaping public perception and policy decisions regarding higher education in the Gulf region. This approach provides an improved understanding of the complex dynamics influencing the development of neoliberal higher education models in Qatar and the UAE.

Our study seeks to address these limitations by critically analyzing newspaper discourses surrounding higher education institutions (HEIs) and international branch campuses (IBCs) in Qatar and the UAE, revealing the underlying ideologies and power structures embedded in media narratives. Using critical discourse analysis, we examine the discursive strategies employed to frame these institutions as models of “world-class” education and “best practices,” while exploring the tensions between global aspirations and local cultural preservation reflected in newspaper narratives. Additionally, we investigate the role of the media in legitimizing specific educational models and policies while potentially marginalizing alternative perspectives.

The present study’s questions are as follows:

1 What ideologies and power structures underpin newspaper discourses pertaining to HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE?

2 How do newspaper articles construct ideologies and power structures, and frame HEIs and IBCs as models of best practices in HE?

3 What discursive strategies are employed by these newspaper articles to present HEIs and IBCs as best practice models in HE?

7 Methods

In our research, we delve into the discourses surrounding HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE. Drawing from Gee (2011), we seek to understand how “in language there are important connections among saying (informing), doing (action), and being (identity) to know who is saying it and what the person saying it is trying to do” (p. 2). Leveraging CT and CDA as analytical tools, we uncover power ideologies and analyze narrative representations across newspapers about the establishment of HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE. Arguably, the expansion of these institutions intersects with geopolitical and socio-economic agendas. By analyzing language and rhetoric employed we recognize discourse’s role in shaping perceptions and legitimizing or contesting neoliberal HEI/IBC models. Our analysis concentrates on how ideology permeates language and tries to determine whose interests these discourses attend to; the analysis enhances our understanding of the implications of rapid HEI/IBC proliferation as integral components of national development strategies.

7.1 Data samples and selection procedures

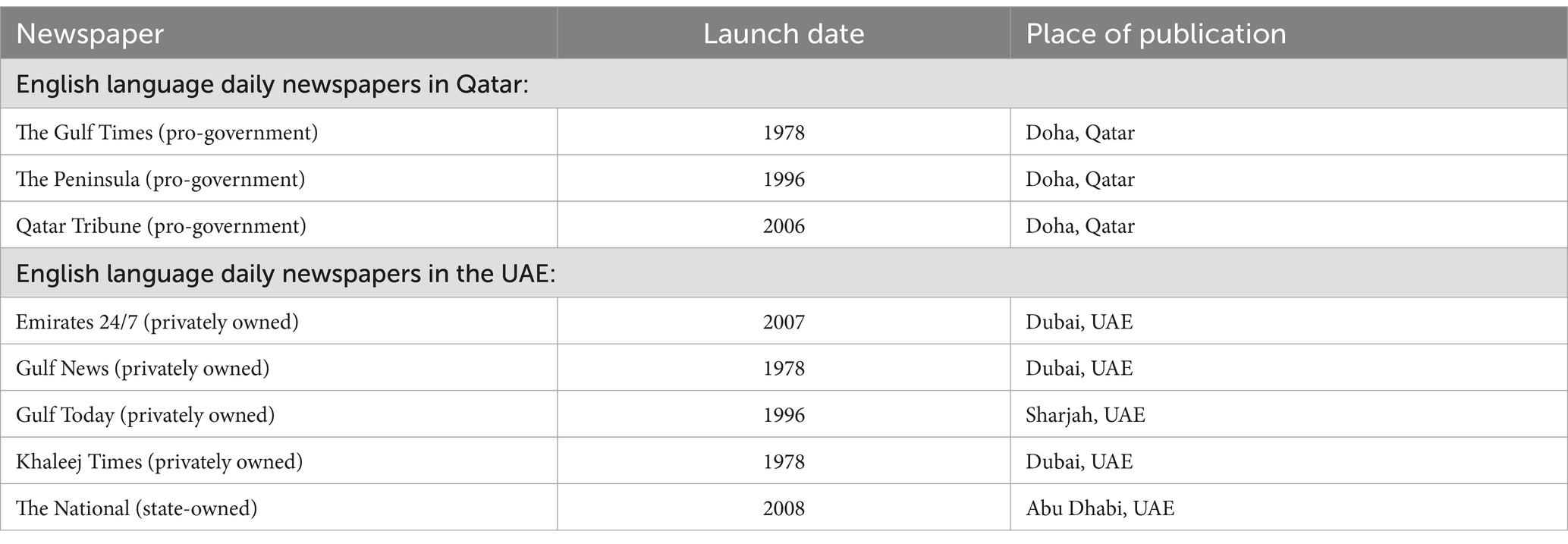

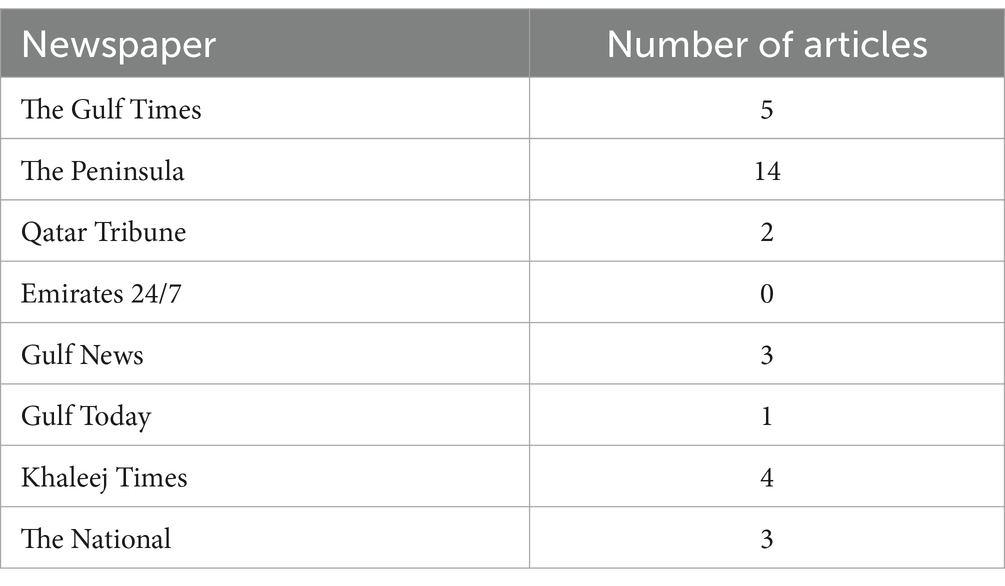

This study employed purposeful sampling as a technique that made it possible to “discover, understand, and gain insight and therefore […] select a sample from which the most can be learned” (Merriam, 2009, p. 249). Our sample consisted of newspaper articles. As is shown in Table 1, the data sources used included all English language newspapers published in Qatar (n = 3) and the UAE (n = 5) between 2010 and 2024.

While these are the only English language newspapers in Qatar and the UAE, information concerning their daily circulation is either outdated (dating back to 2002) or not available at all. The distribution of articles across the newspapers is presented in Table 2.

We selected newspaper articles for analysis as they are a central platform for disseminating official narratives and shaping public perceptions of higher education policies. Through examining these texts, we aim to uncover how neoliberal ideologies are embedded in media discourses and potentially legitimized through their repetitive framing and presentation. The selection of the newspaper articles sampled for this study took into consideration several inclusion and exclusion criteria.

7.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A search for newspaper articles published between 2010 and 2024 in Qatar and the UAE was undertaken, using the terms “higher education,” “university,” “college,” “International Branch Campus,” “IBCs,” “world class,” “world-class,” “best practice,” “best practices,” and the words “Qatar” and “UEA.” The search was further narrowed by the additional terms “policy,’ “education,” “studies,” “studying,” “learning,” “teaching,” and “instruction.” Titles and publication years were two other criteria included in this research. Newspapers articles published in languages other than English were excluded and, to maintain focus on both countries, newspapers from outside these two countries were not included in our search. Similarly, newspaper articles not related to HE and those not within the 2010–2024 period were not considered in this study. Our search yielded 21 newspaper articles in Qatar and 11 in the UAE. However, Emirates 24/7 was excluded from our analysis because no relevant article appeared in it.

The media in Qatar are predominantly state-controlled, with recent liberalization efforts following the emergence of privately-owned outlets. By contrast, the UAE’s media is more diversified, with a mix of government-owned, semi-private, and private outlets. In both countries strict regulations are enforced regarding content, with censorship and self-censorship being common practices to avoid social, cultural, and political sensitivities (Bumetea, 2013). Moreover, the two countries have regulatory bodies that oversee media content to ensure alignment with national values and interests. Despite being subsidized by government funding, the press is essentially privately owned. Foreign press is subjected to censorship upon entry, a practice common in both countries.

The search terms “world-class” and “best practice(s)” were deliberately included due to their prominence in neoliberal discourse on higher education. These terms commonly appear in institutional and policy rhetoric to signal alignment with international standards, excellence, and global competitiveness, which are central themes in media portrayals of higher education reform in the GCC. Their inclusion enabled us to capture discursive framings that valorize market-oriented ideals and to identify instances where media discourse reinforced the legitimization of such narratives. Additional terms such as “policy,” “learning,” and “instruction” were chosen to broaden the scope of relevant articles while maintaining thematic alignment with educational discourse.

7.3 Data analysis

The researchers conducted a close reading of selected texts to identify discourses promoting neoliberal ideologies in higher education institutions (HEIs) and international branch campuses (IBCs) in Qatar and the UAE. Newspapers, as powerful communication media, play a crucial role in disseminating the perspectives of influential actors, reflecting and reinforcing power dynamics in society. By analyzing these texts, we aimed to uncover how media framing shapes public perceptions of the establishment and presence of HEIs and IBCs in these two countries.

We conducted a multi-stage analysis informed by Fairclough, van Dijk, and Wodak. After close reading, we used NVivo to code lexical and rhetorical patterns such as legitimation strategies, metaphors of excellence, and invocations of global benchmarks. We then interpreted these codes through a critical lens to assess how they reproduce neoliberal values. Fairclough’s model structured our analysis across textual, discursive, and social dimensions. Van Dijk’s emphasis on mental models guided our interpretation of ideological presuppositions, and Wodak’s method helped us link these to specific historical and policy contexts in Qatar and the UAE.

We then employed critical discourse analysis (CDA) to explore several key elements. This included an investigation of lexical choices and rhetorical devices used to frame HEIs and IBCs, as well as the presuppositions and implications embedded in the texts. Additionally, we analyzed the representation of social actors and their roles within the discourse, as well as the intertextuality and interdiscursivity that linked these texts to broader neoliberal discourses.

Simultaneously, we coded the texts to identify recurring themes and patterns pertinent to our research questions. Finally, we synthesized the findings from the CT, CDA, and thematic analysis to construct a comprehensive understanding of how newspaper discourses serve to construct and legitimize neoliberal ideologies in higher education. This approach allowed us to uncover both explicit and implicit ways in which power, ideology, and discourse intersect in the representation of HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE.

We employed Fairclough’s three-dimensional framework for CDA, focusing on linguistic features, text production and consumption processes, and the broader social context. Van Dijk’s socio-cognitive approach informed our analysis of how ideologies are reproduced in discourse, examining macrostructures, local meanings, and rhetorical strategies. Wodak’s discourse-historical approach guided our consideration of the historical and political contexts surrounding the newspaper articles.

We initiated our analysis with an initial close reading of the articles, which allowed us to identify recurring themes and discursive patterns. This preliminary examination laid the groundwork for a more detailed CDA, where we meticulously analyzed linguistic features, rhetorical strategies, and ideological framing in each article. The final stage involved a comprehensive thematic analysis, in which we categorized and synthesized the findings from our CDA.

To ensure a systematic and thorough analysis of the data, we employed NVivo software to code the articles. This powerful tool enabled us to create nodes for various elements of our analysis, including linguistic features such as lexical choices and metaphors, rhetorical strategies like legitimation and presupposition, and thematic content encompassing concepts like “world-class education” and “economic development.” This methodical approach allowed us to uncover the intricate relationships between language, power, and ideology in the context of higher education in Qatar and the UAE.

Adopting an interpretative, contextual, and constructivist approach (Richardson, 2007), we sought to uncover the underlying meanings embedded in the data. This approach facilitated the interpretation of texts within their broader institutional and socio-cultural contexts, allowing us to explore how stakeholders frame and negotiate the evolving landscape of higher education. Our analysis focused on neoliberal terminology, framing devices, and rhetorical strategies that present HEIs and policies uncritically. We examined how these discursive practices align with and reinforce state strategies on foreign investment, intellectual conservatism, and social hierarchies.

The researchers conducted a close reading of selected texts to identify discourses promoting neoliberal ideologies in higher education institutions (HEIs) and international branch campuses (IBCs) in Qatar and the UAE. Newspapers, as powerful communication media, play a central role in disseminating the perspectives of influential actors, reflecting and reinforcing power dynamics within society. Through the analysis of these texts, the aim was to uncover how media framing shapes public perceptions regarding the establishment and presence of HEIs and IBCs in both countries.

The analysis followed a structured, multi-step process, guided by the seminal works of Fairclough (1998, 2003), van Dijk (2006), and Wodak (1999), integrating CT, CDA, and thematic analysis.

The first stage involved close reading of each text to identify key themes and discursive strategies related to neoliberal ideologies in higher education. Using CT as a lens, the second stage examined how power structures and dominant ideologies were reflected in the language used to describe HEIs and IBCs. The third stage applied CDA techniques, focusing on lexical choices, rhetorical devices, presuppositions, and the representation of social actors. Additionally, CDA considered intertextuality and interdiscursivity in relation to broader neoliberal discourses. In parallel, the texts were coded through a thematic analysis to capture recurring themes and patterns related to the research questions.

The findings from CT, CDA, and thematic analysis were then synthesized to develop a comprehensive understanding of how newspaper discourses construct and legitimize neoliberal ideologies in higher education. This integrated approach revealed both explicit and implicit ways in which power, ideology, and discourse intersect in the representation of HEIs and IBCs in Qatar and the UAE. The analysis drew on Fairclough’s three-dimensional framework for CDA, which explores linguistic features, the processes of text production and consumption, and the broader social context. Van Dijk’s socio-cognitive approach provided insights into how ideologies are reproduced in discourse, analyzing macrostructures, local meanings, and rhetorical strategies. Wodak’s discourse-historical approach further informed the understanding of the historical and political contexts surrounding the newspaper articles.

The integration of CT and CDA began with CT’s focus on identifying the broader power structures and ideologies within the higher education systems of Qatar and the UAE. This theoretical lens then informed the CDA, which was conducted in three distinct stages: first, an initial close reading to identify recurring themes and discursive patterns; second, a detailed CDA examining linguistic features, rhetorical strategies, and ideological framing; and third, a thematic analysis to categorize and synthesize the findings. NVivo software was used to code the articles systematically, creating nodes for linguistic features (e.g., lexical choices, metaphors), rhetorical strategies (e.g., legitimation, presupposition), and thematic content (e.g., “world-class education,” “economic development”).

Adopting an interpretative, contextual, and constructivist approach (Richardson, 2007), the analysis aimed to uncover the underlying meanings embedded within the texts. This approach enabled an exploration of the interplay between texts, producers, and consumers, interpreting the content within its broader institutional and socio-cultural contexts. The analysis paid particular attention to neoliberal terminology, framing devices, and rhetorical strategies that presented HEIs and policies uncritically. It examined how these discursive practices align with and reinforce state strategies regarding foreign investment, intellectual conservatism, and social hierarchies, thereby constructing a legitimizing narrative for the neoliberal agenda in higher education.

8 Findings

The themes discussed below emerged inductively through iterative coding and interpretation of the newspaper texts. While our theoretical framework sensitized us to power and ideology, we remained open to discovering unexpected framings and discursive tensions during analysis. What follows are the dominant patterns that surfaced across the dataset. Our analysis reveals that the press plays a significant role in promoting neoliberal models of higher education in Qatar and the UAE, often in a manner that appears complicit and uncritical. Our use of the term “promoting” refers specifically to the way newspaper articles reproduce and frame neoliberal discourses, particularly through uncritical repetition of government statements, valorization of global rankings, and consistent use of market-oriented language. This pattern of repetition and endorsement suggests a discursive alignment with state-driven reforms, which, in the absence of counter-narratives, operates as a legitimizing mechanism rather than neutral reportage.

Newspapers frequently reproduce government narratives by quoting officials and repeating policy statements without providing critical analysis or alternative viewpoints. This uncritical reproduction reinforces the dominant discourse and limits public debate. Additionally, the consistent use of neoliberal language, including terms such as “world-class,” “excellence,” and “global competitiveness,” frames higher education in market-oriented terms, emphasizing its alignment with global economic imperatives.

Another prominent theme in the media coverage is the focus on rankings and international recognition. Universities are frequently celebrated for their positions in global rankings and their attainment of international accreditations, which promotes a competitive, market-driven view of higher education. However, this emphasis often overshadows the potential impacts of these policies on local culture and values, perspectives that are rarely represented in newspaper coverage. Critical voices that challenge the neoliberal framing or question its alignment with socio-cultural contexts are notably underrepresented.

In Qatar and the UAE, narratives advocating for the establishment of “world-class” and “best practice” higher education institutions align closely with neoliberal principles of privatization and marketization. Governments are portrayed as actively endorsing policies to attract foreign higher education institutions (HEIs), and the framing of these institutions in media discourse reflects the complexities of negotiating their establishment. From a discourse perspective, local HEIs are often celebrated as paragons of academic excellence, innovation, and research. Their affiliations with prestigious Western institutions are frequently highlighted as rhetorical devices to validate neoliberal policies, underscoring the perceived benefits of aligning with global standards.

This media framing resonates with Habermas’s (1989) critique of commercial mass media, which he argues often supports dominant power structures. In this case, the overwhelmingly positive portrayal of government policies and emphasis on global competitiveness by the press contribute to the normalization of neoliberal ideologies in higher education. The consistent narrative reinforces public acceptance of the market-driven transformation of education systems.

The pursuit of international standards and the aspiration to achieve “world-class” status in higher education are central themes across Qatar and the UAE.

Media coverage emphasizes a commitment to excellence, global leadership, and partnerships, presenting these objectives as justifications for extensive reforms and investments. While both countries share common goals, they also manifest distinctive approaches to holistic development, diversity, inclusivity, and the value placed on international recognition and rankings. These distinctions reflect the unique socio-political and cultural contexts shaping each country’s higher education system. Ultimately, the interplay between global aspirations and local priorities highlights both the convergences and divergences in their educational strategies, as reported in the media.

8.1 Commitment to excellence

Our analysis of Qatar and the UAE’s newspaper reports reveals a shared commitment to excellence in teaching, research, and innovation within both countries’ HE systems. The newspaper rhetoric used consistently emphasizes quality and highlights achievements and milestones, reinforcing the role of these nations as providers of high-quality education. This ongoing dedication to investing in HE is reported as a catalyst for societal advancement and economic progress. Additionally, the designation of HEIs and IBCs as “world-class” constructs a narrative of excellence and “best practices” that dovetails with a strong emphasis on economic growth and knowledge-based economies. Through overwhelmingly positive language and carefully chosen terms, including “world-class,” “cutting-edge,” and “multidisciplinary ecosystem,” the aim is to influence perceptions and create favorable impressions of HEIs in Qatar and the UAE, reinforcing their position on the global map of HE.

In Qatar’s newspaper coverage, commitment to excellence in HE is prominently featured, as evidenced by narratives from The Peninsula, Gulf Times, and Qatar Tribune. Interestingly, UAE newspapers do not mention excellence in HE. Qatar’s newspapers report the country’s progressive initiatives and unwavering pursuit of excellence in transforming its HE sector. A recent article in Gulf Times (October 30, 2023) lauds Qatar’s efforts to enhance HE, confirming that “Qatar has taken significant steps toward revolutionizing its higher education,” demonstrating its strong commitment to excellence in academia.’ Additionally, Qatar Tribune (May 15, 2023) notes the “legacy of excellence” of Texas A&M University-Qatar, an IBC housed in Qatar’s Education City. This corroborates an earlier report in The Peninsula (February 12, 2018), which revealed that Qatar University “rigorously pursued educational excellence.” Subsumed under the theme of commitment to excellence, two distinct subthemes emerge: the aspiration for “world-class” standards and the embrace of “best practices.”

8.2 World-class education and best practices

The discourse used in newspaper reporting of HEIs in Qatar and the UAE often employs the term “world-class education,” signifying the pursuit of excellence in teaching, research, and knowledge dissemination. This pursuit not only elevates the standing of individual institutions but also contributes significantly to the advancement of societies and economies worldwide. For instance, The Peninsula (August 17, 2022) reports the country’s efforts “to promote the country as a world-class education hub,” aiming to attract learners from around the globe. Gulf Times (October 30, 2023) cites Qatar’s commitment to achieving the goals outlined in the Qatar National Vision 2030: “the establishment of world-class educational institutions and initiatives, is a testament to the country’s commitment to realizing the goals of the QNV 2030.” An excerpt from Qatar Tribune dated August 15, 2023, highlights Qatar’s “Education City being home to many world-class universities.”

Across Qatar and the UAE’s newspapers, the discourse promoting the ideals of “world-class” and “best practice” HE is also evident in the recurrent use of phrases such as “international recognition,” “academic excellence,” “cutting-edge education,” and “remarkable milestones.” These core values and attributes are reflective of societal values and aspirations within the HE sector of each country. Ample evidence shows a consistent emphasis on quality, excellence, and advancement in accordance with global standards. Overall, the language used in the newspaper narratives portrays Qatar and the UAE as forward-thinking countries that are actively seeking to advance their educational standards to meet international standards. By emphasizing achievements, quality, and research, the two countries position themselves as key education players in the region, committed to providing world-class education and contributing to the advancement of knowledge and innovation.

Qatar’s commitment to HE is exemplified by its strategic partnerships with leading universities from the United States, Europe, and other regions, fostering knowledge exchange and sharing best practices. The Peninsula (February 12, 2018) indicates that Qatar University “has earned a good reputation as one of the most prestigious universities in the region.” An article released by the Gulf Times on June 26, 2023, titled “Education core pillar of Qatar National Vision” demonstrates that the University of Doha for Science and Technology strives “to provide world-class education and offer our students programs that give them real-life experiences and prepare them to lead the careers of the future.” These reports highlight the significant role of HEIs in shaping the future of the region and the world at large.

In parallel, UAE newspaper discourse displays a similar quest for “world-class” standing. Together, newspaper narratives paint a promising picture of a nation poised to transform its HE through strategic partnerships, technological empowerment, and a commitment to inclusivity and global best practices. As reported by Khaleej Times (November 25, 2022), the UAE has made significant leaps to establish “a world-class education system that leaves no one behind, powered by the ceaseless embrace of technology, underpinned by gender parity and inclusion, and given wing by unparalleled creativity and innovation,” in a statement by the Minister of State for International Cooperation and Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi’s chair of the board of trustees.

Emphasizing Khalifa University’s commitment “to deliver world-class education in line with international standards and best practices,” as outlined by The National (July 4, 2023), Khalifa University’s objective is reported to encapsulate the region’s ambition to not only elevate its HE to meet global benchmarks but also to create an environment that nurtures innovation, inclusivity, and excellence. Across the region, government efforts to improve HE were reported to be oriented toward meeting international benchmarks against international standards and maintaining high educational levels, as was evident in the rhetoric of “best practices,” “academic rigor,” “commitment to quality education,” and “highest quality research.”

8.3 Global leadership and recognition

The analysis of the discourse used in newspaper reporting further unveiled a collective ambition of HEIs in Qatar and the UAE to assert leadership on the regional education map is evident and position themselves as hubs of world-class HE while also underscoring a strong emphasis on quality and the recognition of each institution’s accomplishments. A strong emphasis on maintaining a global outlook and achieving international recognition was also reported in the newspaper articles, with institutions aligning their academic programs with international standards. Accordingly, universities were frequently presented in terms of their achievements and rankings, portraying them as emblematic of academic excellence. For example, HEIs’ rankings in prestigious international indices, such as the Times HE Young University Rankings, serve to validate efforts to enhance HE.

In articulating aspirations for global recognition and conformity with international benchmarks, newspaper discourse in Qatar and the UAE depicts HE using terms such as “globally-renowned education,” “international recognition,” and “alignment with global standards” (e.g., Gulf Times, 2023; Peninsula Newspaper, 2018, 2022, 2023). These depictions, which denote a deliberate emphasis on the pursuit of global recognition and competitiveness within the GCC, are indicative of a strategic ambition to assert the prominence of Qatar and the UAE’s HEIs as reputed players in the international arena, all the while committing to adhere to established global standards. Moreover, the recurring mentions of the terms “innovative teaching methods,” “cutting-edge educational technologies” and the integration of “21st century skills,” suggesting a collective commitment to staying at the forefront of educational practices and a shared goal of keeping pace with global advancements in the field of HE.

A recent piece by The Peninsula (May 7, 2023) reports on Qatar University’s ranking in 2023 stating that “This new ranking also places QU in 4th place in the Arab world.” It comments “This recognition is a testament to QU’s unwavering commitment to providing a world-class research environment and to advancing knowledge in this vital field, making it one of the best research institutions in the world.” In an article titled “NU 12th in ranking of US colleges,” The Peninsula (September 14, 2015) reports how Northwestern University – an IBC housed in Qatar – prides itself in “the world class academic experience we provide.” Another notable excerpt from The Peninsula (May 2022) refers to HEC Paris in Qatar as “bringing world-class executive education to the region,” noting that this IBC “topped the FT rankings for preparation, participant quality, teaching methods and materials, faculty, new skills and learning, follow-up, aims achieved and value for money.”

UAE-based newspapers echo a similar pattern demonstrating the fervor surrounding world-class acclaim. For instance, the Gulf News (July 15, 2023) coverage of UAE-based Abu Dhabi University ranking 58th globally in the Times rating reported a “well-deserved recognition by the prestigious Times Higher Education Young University Rankings 2023.” The article adds this is “a testament to [our] unwavering commitment […] to go above and beyond to equip our students with the needed skillset and cutting-edge educational methods …” While the discourse in this example highlights inclusivity and creativity, which are values often associated with social-democratic models, the framing of a “world-class education system” within the context of rankings, technological embrace, and competitiveness reflects the underlying logic of neoliberalism. As Ball (2012) notes, neoliberal discourses often appropriate the language of equity and innovation while anchoring it in market-oriented reforms. Terms like “world-class,” though rhetorically progressive, function as ideological shorthand for alignment with international benchmarks, competitiveness, and performance-based legitimacy. Thus, their invocation in policy and media texts reinforces neoliberal priorities by tying educational legitimacy to global visibility, brand prestige, and measurable outcomes, rather than intrinsic commitments to public good or collective welfare.

A recent Khaleej Times article (January 24, 2024), titled “UAE: A World-Class Destination for Your Education,” writes that 10 universities featured in the 2020 QS Arab Region University Rankings, and eight in the 2021 World University Rankings, with Khalifa University of Science and Technology being one of the UAE’s top HEIs. The National (July 4, 2023) underlines the international acclaim of UAE’s HEIs, noting, “Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi and UAEU in Al Ain were listed in the top 300 in the 2024 University Rankings by Quacquarelli Symonds.” The newspaper underscores the HEIs’ commitment to “deliver world-class education in line with international standards and best practices.”

8.4 Collaboration and partnerships

The analysis of the newspaper narratives presented Qatar and the UAE as leveraging international – mainly Western – models of education, valued for their role as vehicles for establishing their HEIs as hot beds of academic excellence and innovation. Nevertheless, beneath these narratives, which portray the two countries as champions of global leadership and innovation, lie localized and sovereign social and political agendas. The two countries profess their identities within the global educational landscape, intertwining the global and the local in their quest for educational excellence. The educational initiatives created by each, including the establishment of IBCs, are often tailored to reflect and reinforce local political priorities.

The newspaper narratives further illustrate initiatives aiming at advancing educational excellence through forging collaboration and partnerships with renowned international HEIs, reflecting what is described as “a real spirit of collaboration” (Qatar Tribune, August 15, 2023). These initiatives are depicted as a cornerstone of their pursuit of world-class standards. Concerted efforts by Qatar and the UAE are portrayed as deliberate actions to leverage global expertise through collaborations with foreign HEIs, underlining the value of global cooperation in enhancing educational quality. The narratives portray collaborations and partnerships with prestigious international universities as catalysts for joint research ventures and initiatives geared toward sharing best practices and fostering knowledge exchange.

Collaboration with reputed institutions demonstrates a commitment to high-quality education and validates the credibility and legitimacy of HEIs in both countries. The discourse in the selected newspaper articles positions Qatar and the UAE as regional and international leaders in HE. For example, The Peninsula (October 7, 2023) reports Qatar University’s strategic partnership with leading online learning platform Coursera, aimed at enhancing cross-skilling of current QU students, elevating graduate skills for future employment, and providing professional development opportunities for faculty. Similarly, Gulf Times (June 26, 2023) discusses Qatar’s efforts to strengthen its HE sector through international collaborations, facilitating expertise transfer and the development of academic programs and research centers.

This narrative is reinforced in Gulf Times (October 30, 2023), which cites that “collaboration with Ulster University, resulting in the establishment of CUC Ulster University in Qatar … reflects Qatar’s proactive approach to integrating global academic excellence into its higher education system,” exemplifying successful international partnerships. Interestingly, examination of UAE newspapers shows a lack of discussion on excellence in HE.

8.5 Qatar versus UAE narratives: contrasts

The discursive depictions of HEIs in Qatar and the UAE’s newspaper coverage exhibit distinct differences, primarily due to varying ideologies, objectives, target audiences, and economic interests. Coverage of international recognition and rankings discloses distinct approaches, albeit with shared themes. While both countries report achievements and international acclaim in global rankings, Qatar’s discussions tend to encompass a broader spectrum of factors beyond academic excellence alone, reflecting a wide-ranging approach to assessing institutional success. In contrast, UAE’s newspapers emphasize international recognition and rankings as key indicators of academic excellence.

Newspaper narratives also disclose a contrast between Qatar’s focus on holistic personal development and the UAE’s emphasis on economic pragmatism, indicating differences in educational objectives and interactions between economic ambitions, cultural values, and educational philosophies. Qatar’s newspapers champion a comprehensive approach to learning that promotes academic excellence and the cultivation of students’ skills, character, and overall wellbeing, transcending immediate economic returns to foster well-rounded individuals. In contrast, the UAE’s newspapers prioritize the country’s educational strategy as linked to the demands of the modern workforce and broader economic objectives, emphasizing education as a conduit for economic development and workforce preparation.

The depiction of diversity and inclusivity in HE sharply contrasts between Qatar and UAE newspaper narratives, revealing differences in policy orientation and public engagement. Whereas Qatari newspapers suggest a reluctance to directly engage with these matters, in stark contrast, UAE newspapers deliberately affirm the country’s dedication to delivering education catering to diverse communities and nationalities. This approach showcases the UAE’s commitment to celebrating cultural diversity. These contrasts underscore the importance of national context in shaping the localization of global neoliberal tropes. The comparative lens adopted in this study offers a valuable contribution to the literature by illustrating how similar ideologies are articulated through distinct rhetorical strategies that align with specific socio-political and media structures.

The consistent valorization of “world-class” education, international rankings, and global competitiveness across the media texts analyzed reveals a clear alignment with neoliberal ideals. These discursive patterns reflect more than aspirational rhetoric as they instantiate a unidirectional ideological movement toward market-oriented reform. Even when packaged with language of inclusion or creativity, the dominant framing ties educational value to performative criteria: competitiveness, institutional branding, and economic returns. This coherence across representations suggests that the discourse is not merely informed by global educational trends, but is firmly rooted in neoliberal rationalities that prioritize efficiency, competition, and private sector alignment over collective, civic, or rights-based educational values.

9 Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze newspaper discourse narratives underlying HEIs and IBCs in two GCC states, as communicated in local English newspapers. The study subscribes to the view that the establishment of HEIs and IBCs, which are glamorized as emblems of progress and development, is justified through discourses that advocate for world-class education (Siltaoja et al., 2019) and best practices (Zajda and Majhanovich, 2022). These discourses echo a neoliberal agenda that prioritizes economic growth over social welfare. Rooted in the critical paradigm, our analysis has shown how power operates to normalize ideas within discourse. We view discourse as “a faithful reflection of an underlying ideology, which emerges in the selection of the news elements (what is included and what is not as a part of the information), in the interpretation” (Paniagua et al., 2007, p. 11) and a tool generating “regimes of truth,” actively shaping social order and constituting reality (Foucault, 1980).

Central to GCC countries’ strategic visions lies a clear emphasis on raising educational standards to match international excellence benchmarks. Unsurprisingly, the proliferation of HEIs and IBCs – often heralded as beacons of world-class quality and best practices – in Qatar and the UAE reflects a discourse entrenched within the overarching neoliberal ideology. The discursive framing of HEIs and IBCs is clearly woven into a rhetoric that champions progress and the pursuit of global excellence. Frequent invocations of “world class” and “best practice” in newspaper narratives signifies a deliberate positioning within a globally competitive educational arena designating a commitment to neoliberal ideals, market-oriented standards, and global competitiveness. The narratives invite closer examination, suggesting that the true measure of excellence extends beyond global rankings to encompass societal impact and the achievement of a comprehensive educational mandate. This challenges the notion that excellence can be captured by adherence to neoliberal benchmarks alone.

The newspapers’ overwhelmingly positive portrayal of government policies concerning HEIs in Qatar and the UAE can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, this positivity may result from the media’s alignment with governmental visions of HE, often emphasizing progress and development, thus reinforcing the state’s agenda. Secondly, the media’s reliance on official government sources may lead to the replication of government narratives, potentially skewing perceptions favorably toward HEIs and related policies. This tendency is exacerbated by societal hierarchies and media constraints in the GCC, where deference to authority figures is expected.

The newspaper narratives need to be interpreted against the socio-cultural backdrop surrounding GCC media outlets, which tend to refrain from critiquing government policies, primarily because of official control including direct ownership, funding, and regulatory frameworks (Richter and Kozman, 2021). Influenced by socio-political emphasis on consensus, cultural norms of authority respect, and economic dependencies, this environment limits public criticism of government actions, including education policies. State-affiliated media dominance and restricted independent journalism further reduce critical discourse on educational reforms, resulting in cautious media attitudes toward challenging governmental policies, including in education.

The narratives in local and international newspapers about HEIs and IBCs often encapsulate tensions that stem from competing discourses. On the one hand, these institutions are framed as hubs of innovation, global engagement, and cultural exchange, fulfilling a utopian vision of higher education as a public good that transcends national borders. Terms such as “world class” and “best practices” are employed to position these institutions as symbols of excellence and progress. This celebratory discourse constructs HEIs and IBCs as key actors in facilitating knowledge economies, enhancing employability, and driving societal advancement. Despite rhetorical tensions, our analysis reveals a largely unidirectional discursive trajectory: one that consistently advances neoliberal norms as the central framework for legitimizing higher education policy and practice. The media’s repetitive use of market-aligned vocabulary, celebration of competitive metrics, and omission of alternative models reinforces a single ideological orientation rather than presenting a plurality of educational imaginaries.

As Lo (2024) observes, the Prague School’s emphasis on functional sentence perspective and the aesthetic function of language provides a valuable lens for understanding how terms like “world-class” operate as ideologically marked signifiers. Rather than serving as mere descriptors, such terms are foregrounded to carry symbolic weight, aligning institutional narratives with global imaginaries of prestige and modernity. Viewed through a semiotic lens, the recurrent use of elevated terminology, including “excellence,” “cutting-edge,” and “world-class,” can be seen as a form of ideological encoding. Drawing on the Prague School’s theory of markedness and foregrounding, these expressions function as symbolic shorthand for valorized neoliberal ideals. Their repetition in media texts transforms ostensibly descriptive language into persuasive rhetoric that legitimizes particular visions of higher education aligned with market-driven values and state agendas. This is particularly evident in the recurrent invocation of “world-class” across media discourse, which, despite surface-level associations with inclusivity, operates as a performative and aspirational marker of neoliberal alignment, privileging metrics-driven competitiveness over contextually embedded notions of equity or public good.

This semiotic perspective adds a critical interpretive layer to our discourse analysis. It illustrates how the aesthetic structuring of language contributes to the normalization of neoliberal ideology. By foregrounding certain lexical choices while marginalizing alternative framings, media discourse constructs an idealized image of higher education, one that privileges marketable outcomes, global visibility, and institutional competitiveness. In doing so, it elevates the neoliberal university as an aspirational norm, shaping both public perception and policy endorsement.

These insights point to the need for future critical discourse analyses to incorporate semiotic frameworks, particularly in contexts where ideological framing and linguistic aesthetics intersect. In Qatar and the UAE, where the media plays a central role in legitimizing state-led development narratives, understanding how meaning is constructed through both form and content deepens our grasp of how neoliberalism is discursively reproduced within the higher education sphere. We acknowledge, however, that media texts alone do not determine meaning. Audiences are not passive recipients but interpret media content through various filters shaped by social position, experience, and critical engagement (Hall, 1980).

While this study has primarily focused on how media texts discursively construct and legitimize neoliberal ideologies, it is important to acknowledge that media effects are not uniformly received. Even in heavily regulated environments such as Qatar and the UAE, audiences may not be passive recipients of dominant narratives. Readers may engage in resistant or negotiated readings, reinterpreting media messages based on their own social positions, experiences, and critical faculties. Recognizing this potential for audience agency adds a necessary dimension of reflexivity to our analysis and invites further research into how such media discourses are consumed, contested, or rearticulated within the public sphere.

On the other hand, the same narratives simultaneously reveal a deep alignment with neoliberal ideologies. The focus on terms like “knowledge transfer” and the economic contributions of HEIs and IBCs reflects a market-oriented view of higher education, where success is measured predominantly in economic and utilitarian terms. Such framing underscores the commodification of knowledge and education, portraying them as tradable goods in the global market. This creates a tension between the idealized portrayal of HEIs and IBCs as altruistic centers of learning and their role as agents of privatization, market competition, and global economic strategies.