- 1School of Education, University at Albany (SUNY), Albany, NY, United States

- 2Department of Educational Policy and Leadership, School of Education, University at Albany (SUNY), Albany, NY, United States

Research has demonstrated the difficulties faced by educators during the COVID-19 pandemic. In these unprecedented conditions, educators were asked to manage their emotions in new and challenging ways, thus exacerbating their relatively high levels of stress levels and burnout. We contribute to research on the pandemic's impact on educators through a qualitative case study conducted with 88 educators working in six schools across New York State. In this paper, we explore these educators' experiences of emotional labor during the pandemic, drawing attention to the ways educators managed emotions along display rules that compelled them to mask signs of stress and maintain a positive attitude. Through the constant-comparison method of data analysis, we found collegial support to be a crucial resource which participants drew on to manage their emotions in this highly stressful context. These findings have important implications for educators and policymakers as stress is a major contributor to the workforce shortages many schools across the United States are currently experiencing.

Introduction

Recent research has provided copious evidence that educators' stress levels increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Leo et al., 2022; Hirshberg et al., 2023; Kush et al., 2022). Scholars have demonstrated that educators experienced challenging emotions throughout the pandemic's unprecedented disruptions thus increasing their levels of stress and burnout (Kraft et al., 2020; Snow et al., 2023; Steiner and Woo, 2021). While the worst of pandemic-related challenges subsided by the 2023–24 school year, its impacts on youth and the educators who serve them have been deep and lingering (Hirshberg et al., 2023; Richard et al., 2023)—offering good reason for more scholarship.

In this paper, we draw on qualitative data gathered in summer/fall of 2022 among 88 educators working in six different P-12 schools in New York State. Through the lens of emotional labor, we explore how educators experienced the pandemic and with a focus on how they managed and displayed emotions educators which often conflicted with their actual feelings. In particular, we draw attention to the “display rules” (Hochschild, 1983; Stark and Bettini, 2021; Zheng et al., 2024b) which shape the ways individuals publicly express their emotions. For instance, data collected in this study illustrate how participants felt the need to demonstrate positivity in front of their students despite rising levels of stress. Although positivity—which can be defined as a range of emotions, behaviors, and feelings that elicit good feelings (Seligman et al., 2009)—can provide important benefits to individuals' mental and physical health as well as job performance (Caprara et al., 2012; Lauriola and Iani, 2015; Milioni et al., 2016), “relentless” positivity (Ehrenreich, 2009) may undermine individuals' ability to receive negative information or share disconcerting opinions. Moreover, educators' overly positive stance may prompt educational leaders and policymakers to overlook deeper, structural changes needed to improve conditions in schools and may draw, instead, attention to improving individual characteristics such as determination, grit, and perseverance (Collinson, 2012; Pascoe, 2023). As our findings suggest, educators who feel obligated to express emotions which conflict with their actual feelings may experience heightened levels of stress.

As school districts throughout the United States—and in New York State where this study was conducted—continue to experience workforce shortages, it is crucial to understand educators' experiences of stress and particularly how they manage emotions (Darling-Hammond, 2022; Gardner and Slattery, 2024; Marshall et al., 2022; Steiner and Woo, 2021; Wiggan et al., 2021). This focus on how educators manage emotions is important for educators themselves but also for youth who may suffer negative impacts when educators struggle with stress (Burić and Frenzel, 2021; Hamilton and Doss, 2020; Schonert-Reichl, 2017).

In what follows, we discuss related scholarship on teacher emotions and recent work highlighting educator stress during the pandemic. We then turn to a critique of positivity before exploring our data through the lens of emotional labor. We conclude this article with a discussion of what this research contributes to our understandings of educators' stress and implications for educator shortages facing schools across the United States.

The emotions of teaching

As Hargreaves wrote decades ago, emotions are “at the heart of teaching” (Hargreaves, 1998, p. 835). Indeed since his declaration, decades of research have elaborated on the various ways emotions deeply impact educators' identities, their teaching quality, and their students' experiences in school settings (e.g., Kelchtermans, 2005; Lortie, 1975; Snow et al., 2023; Zembylas, 2003; Zheng et al., 2024b).

The large and growing corpus of literature examining teachers' emotions has identified numerous factors at both the institutional and individual level that contribute to the character of educators' emotional experiences and the kinds of emotional labor they perform (Brown et al., 2023; Horner et al., 2020). In a study of 53 Canadian teachers, Hargreaves (2001) found that five factors impact the emotional work performed by educators: relationships with colleagues; feelings of appreciation and acknowledgment; personal support and social acceptance; cooperation, collaboration, and conflict; and trust and betrayal. Chen's (2016) model highlights several variables which positively impact educators' emotional work: Positive interactions with students and colleagues, recognition from families and the public, while perceptions of unfair treatment, competition with colleagues, work-life imbalances, and pressures from policy changes can impact a teachers' emotions negatively.

Teachers' emotions cannot be understood without taking into account the wider context in which they are expressed (Brown et al., 2023; Gallant, 2013). Emotions are not simply individual displays but are “sociocultural constructions” which are embedded in both proximal relationships with students, families, and colleagues and also situated in the wider political and cultural milieu which inform definitions of “good” teaching (de Ruiter et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2023; Purper et al., 2023). For instance, teachers' own teaching philosophy, their views toward their students and colleagues, and their personalities may contribute to what Zembylas calls an “emotional ecology” (2007). Teachers working in schools undergoing significant changes or directly impacted by educational reforms may also experience different emotions than those working in more stable contexts (Wilcox and Lawson, 2018; Snow et al., 2023; Van Veen and Sleegers, 2006; Wang et al., 2021). For instance, researchers have found that the shift to high-stakes accountability which links teacher evaluations to students' performance on exams may heighten teachers' stress levels (Guenther, 2021; Towers et al., 2022).

Because emotion is an intimate part of teaching, teachers' professional identities are linked to the emotional displays expected in schools and classrooms (Aldrup et al., 2024; Brown et al., 2014; O'Connor, 2008). To this point, researchers have found that teachers' own self-definitions of good teaching are strongly linked with the display of positive emotions and suppression of negative ones (Burić et al., 2021; Nias, 1987; Zembylas, 2003). As such, teachers' identities are often connected with the expectation to be caring and kind toward their students (Jones and Kessler, 2020; Nichols et al., 2017; Noddings, 2012). As part of their job duties, teachers often feel expected to exhibit emotions such as kindness, caring, and enthusiasm while regulating negative emotions such as anger, frustration, and sadness (Chang et al., 2022; Fan and Wang, 2022; Wróbel, 2013). In short, the display of positive emotions is closely associated with being a “good” teacher (Noddings, 2012; Sutton, 2004).

Positive impacts on teachers' performance and higher rates of workforce retention can occur when teachers feel less pressured to display emotions that do not match their actual feelings (Humphrey et al., 2015). Emotions can also motivate teachers to pursue and fulfill goals, focus their attention, spur problem-solving, and heighten memory recall (Frenzel et al., 2021; Sutton and Wheatley, 2003). Teachers also gain personal and professional satisfaction from having positive impacts on students or when they are given recognition by supervisors, families, and colleagues for their performance (Lortie, 1975; Noddings, 2012). Teachers' emotions can impact not only their own wellbeing, but their students' as well. For instance, educators who must consistently manage challenging emotions may experience emotional exhaustion and are more likely to leave the profession thus leaving their students with new relationships to develop and new classroom routines to perform (Kariou et al., 2021; Yilmaz et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2024a). Educators' emotional displays also may influence their students' motivation and levels of engagement in the classroom and can also impact their achievement (Burić and Frenzel, 2021; Schonert-Reichl, 2017; Sutton and Wheatley, 2003; Wang et al., 2019).

Further, it is crucial to understand how emotional labor and emotions themselves may be “racialized.” For instance, researchers have noted how educators of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds experience and express emotional labor differently (Evans and Moore, 2015; Matias, 2016). As Leonardo and Zembylas (2013) explain, emotionality is crucial to the perpetuation of Whiteness as an exclusionary category. In this sense, Whiteness relies on specific emotional practices to define itself and set itself apart from non-Whiteness as particular emotions “become attached” to individuals (Leonardo and Zembylas, 2013). This line of inquiry has shown how people of color may be stereotyped as overly emotional or “difficult” if they choose to speak out against racial inequities they encounter (Evans and Moore, 2015). In contrast, White educators may perform emotions such as pity or sympathy toward their non-White students to maintain the status quo and avoid more challenging discussions about racial injustice (Leonardo and Gamez-Djokic, 2019; Matias, 2016).

These impacts on teachers are crucial given the workforce shortages experienced by school districts across the U.S. (Marshall et al., 2022; Steiner and Woo, 2021; Wiggan et al., 2021). As Wiggan et al. (2021) note, by 2030 an additional 1.5 million teachers will be needed to staff schools across the country. In New York State, where this study was conducted, 18 areas have been identified as having teacher shortages compared to only three a decade earlier (Gardner and Slattery, 2024).

Educator emotion during the COVID-19 pandemic

Reports of teachers' heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic have become widespread (Leo et al., 2022; Hirshberg et al., 2023; Kush et al., 2022; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021). A variety of factors have been implicated in these reports including the abrupt shift to remote teaching, concerns over teaching effectiveness (Kim and Asbury, 2020; Pressley and Ha, 2021), and teachers' worries over their students' and their own safety during the pandemic (Wilcox et al., 2021; Klapproth et al., 2020; Snow et al., 2023).

The pandemic also required educators to manage their emotions in uniquely challenging contexts. For instance, some research has found that educators felt anxiety and concern for their students during periods of school closures and social distancing despite often feeling unable to directly support them (Bintliff, 2020; Herman et al., 2021). Recognizing the struggles of many of their students, teachers often felt the need to protect students from their own negative feelings about the pandemic (Santihastuti et al., 2022). As Chang et al. (2022) demonstrate in their mixed-methods study of teacher burnout during the pandemic, suppressing negative emotions can lead to negative consequences such as burnout and reduced enthusiasm for teaching.

The abrupt shift to remote teaching also precipitated emotional responses from educators. For many educators, remote teaching was an unprecedented situation in which they were asked to display shift rapidly to new teaching modalities (Auger and Formentin, 2021). Large numbers of disengaged and chronically absent students during periods of remote teaching dampened the rewarding aspects of teaching for many educators and made it difficult to maintain the same levels of confidence and efficacy in their teaching many felt (Hargreaves, 2021). Even after schools reopened, educators frequently continued to worry over their teaching effectiveness as social distancing measures, at times, made it hard to implement high quality instructional practices (Love and Marshall, 2022). Additionally, the challenging, and sometimes contentious, relationships between educators and families over social-distancing rules also contributed to feelings of frustration and being unappreciated for some teachers (Leo et al., 2024; Hartney and Finger, 2020). In some cases, educators felt frustrated as they were regularly not included in decision-making processes impacting their teaching practice and wellbeing (Leo et al., 2023).

How students experienced the COVID-19 pandemic, however, was not uniform. Research has shown that the pandemic had disproportionate impacts across communities and therefore impacted educators and their emotions differently. For instance, students of color incurred disproportionate impacts from the pandemic as their families were more likely to contract the virus due to their overrepresentation as “essential workers” (Hassan and Daniel, 2020; Allen et al., 2021). Moreover, for youth of color, COVID-19 existed alongside other pandemics of systemic racism and police-related violence (Curchin et al., 2024; Wallace and Wallace, 2021). The uneven effects of the pandemic (and multiplier effect of several pandemics disproportionately affecting youth of color) created additional stressors and challenges for educators who served racially-minoritized populations (Wilcox et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2021; Kraft et al., 2020).

The limits of positivity

Positivity is certainly not without its benefits. Research has shown that a positive outlook can serve as a resource on which individuals may draw in efforts to manage stress during challenging times (Alessandri et al., 2012; Caprara et al., 2017). A range of studies—a thorough review of which is beyond the scope of this paper—have found associations between positivity and beneficial outcomes to both physical and mental health (e.g., Rasmussen and Wallio, 2008; Scheier et al., 2001). According to psychologists, positivity can encourage individuals to engage in healthy behaviors and promote resiliency as difficulties are viewed as temporary or able to be overcome (Peterson, 2006; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Bandura (1994), for instance, suggests that a positive assessment of one's own abilities may actually promote better outcomes. In other words, if one views a situation as amenable to their influence, then they are more likely to create desired impacts (Ahmad and Safaria, 2013; Bandura et al., 2001; Walton and Cohen, 2003).

Biologists have found that positive expectations can even impact one's immunological responses such as in cases where patients' actual prognoses may improve if they believe a medicine to be effective in treating their ailment (regardless of that medicine's actual efficacy; Benedetti, 2020). Those demonstrating higher levels of positivity are also found to be happier, less depressed, and report more life satisfaction—all indicators which are associated with decreased stress (Alessandri et al., 2012; Caprara et al., 2012; Lauriola and Iani, 2015; Milioni et al., 2016).

Recent scholarship has highlighted the potential for positive thinking to buffer against some of the negative impacts experienced by individuals during the pandemic (Ahorsu et al., 2020; Vos et al., 2021; Yildirim et al., 2022). Yildirim and Güler (2021), for instance, found that positivity mediated the effect of pandemic-induced stress among 3,109 Turkish adults. Others have found that optimism during the pandemic increased levels of resilience, thus serving as a “protective factor” against mental and physical ailments (Arslan et al., 2020; Burt and Eubank, 2021; Krifa et al., 2022). Ferreira et al. (2021) reported similar findings in a survey of 586 Portuguese adults—positivity predicted lower levels of depression among respondents. These studies, among others (Leslie-Miller et al., 2021; Thartori et al., 2021), suggest that positive emotions and optimism can serve as a resource upon which individuals may draw during times of stress and upheaval. Such findings are significant given the high rates of pandemic-related stress reported by educators described above.

Although these findings highlight the potential benefits brought to individuals who think positively, other scholars have highlighted the pitfalls of positive thinking. Ehrenreich (2009), for instance, argues that “relentless promotion of positive thinking” has undermined individuals' ability to receive or critically analyze upsetting information. Drawing on her own experience of being diagnosed with cancer, she criticizes the encouragement of positivity as a panacea for those facing challenging circumstances (Ehrenreich, 2009). Collinson (2012) likewise notes that excessive positivity can stifle the voices of those expressing dissent or alternative ideas and discourage those in power from admitting errors or lapses in judgment. France (2021), a teacher who left the profession during the pandemic, criticizes his experiences of “toxic positivity” in the workplace. France (2021) concurs with Collinson (2012), noting that toxic positivity suppresses dissenting viewpoints and fails to acknowledge the tangible resources and supports that teachers need to meet the demands placed on them. As he writes, mandated forms of positivity encourages teachers to “put their students and their schools before themselves and their own families” (France, 2021, p. 1).

In an ethnographic study of an American high school, Pascoe (2023), argues that a culture of kindness and positivity is not only ineffective for tackling educational inequalities, but may ultimately distract those with good intentions from seeking long-lasting solutions. In these cases, positivity may actually obscure the structural changes needed to ameliorate difficulties and instead place these responsibilities onto individuals (Cerulo, 2019; Shiller, 2005). The concept of “cruel optimism” coined by the philosopher Berlant (2010), refers to a similar situation in which individuals attach themselves to a desired outcome which has become impossible to attain. This attachment, writes Berlant, turns cruel when it becomes an “obstacle to [one's] flourishing” (Berlant, 2010, p. 1). Optimism can become harmful when individuals view their individual shortcomings as the reason behind an inability to attain positive outcomes while neglecting the wider social, political, and economic factors that can enable or constrain success (Leo, 2022; Bartlett et al., 2018; Sweeny and Shepperd, 2010).

Pandemic-related research has provided some validation of the concerns raised above. For instance, several studies have found that individuals who hold “unrealistic” levels of optimism about one's vulnerability to COVID-19 may have made them less likely to engage in precautionary behaviors and thus more likely to contract the virus (Dolinski et al., 2020; Van Bavel et al., 2020; Vieites et al., 2021). In these situations, individuals may falsely believe that negative events (such as contracting COVID-19 or becoming seriously ill from it) are less likely to happen to them than to other people (Gassen et al., 2021). Moreover, overly optimistic views about the pandemic, warns Holmes et al. (2021), may turn into a simple aspiration to return to “normal.” Such desires may unintentionally serve to reproduce inequities which existed prior to—and may have been exacerbated during—the pandemic such as the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic on people of color and those from lower socioeconomic households (Allen, 2021; Hassan and Daniel, 2020; Jones et al., 2021).

In the following sections, we draw on the concept of “emotional labor” (Caringi et al., 2012; Hochschild, 1983) to explore educators' emotional experiences during the pandemic. In particular, we draw attention to the way positivity acted as an implicit “display rule” (Hochschild, 1983; Horner et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2024a) which molded the way educators expressed their emotions.

Conceptual framework

This study utilizes the concept of emotional labor to guide our interpretation of the qualitative data collected from P-12 school educators (Hochschild, 1983; Stark and Bettini, 2021; Zheng et al., 2024b). As introduced above, the term “emotional labor” first came to prominence through Hochschild's (1983) book The Managed Heart where she outlined the growing demands on service workers to manage their emotions in ways prescribed by employers and clients. According to Hochschild, emotional labor is “the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display [that is] sold for a wage” (Hochschild, 1983, p. 7). It is characterized by face-to-face contact with the public, the provocation of emotional states in workers, and the exercise of control from managers over the emotional responses by workers (Caringi et al., 2012; Hochschild, 1983).

This “management of feeling” (Hochschild, 1983, p. 7) is communicated to workers through emotional “display rules” which discipline workers by restricting the ways they may express their emotions. Educators may conform to perceived display rules for a variety of reasons including providing emotional support to colleagues and students and to demonstrate their professional competence (Horner et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2023; Stark and Bettini, 2021). Display rules are not simple expressions of one's innate feelings, instead they may be seen as exercises of institutional and ideological power which educators may conform to or resist in different moments and through different actions (Benesch, 2018; Chang et al., 2022; de Ruiter et al., 2021). Workers may incur stress and exhaustion as they seek to conform to display rules by exhibiting emotions which conflict with their actual feelings (Brotheridge and Grandey, 2002). In contrast, conforming to display rules which coincide with educators' actual feelings and emotions can heighten enthusiasm and caring for students and improve teaching effectiveness (Burić and Frenzel, 2021; Zheng et al., 2024a). Two related strategies identified in the emotional labor literature include “surface acting” which involves a superficial display of emotion without genuinely feeling that emotion, and “deep acting” where workers try to alter their felt emotions in order to align them more closely to the expectations of their employers and the consumers they serve (Ashkanasy and Dorris, 2017; Aldrup et al., 2024; Hochschild, 1983). While such efforts involve what others have identified as emotional regulation (e.g., Fan and Wang, 2022), we utilize the framework of emotional labor, in particular, to highlight the display rules which guide teachers' behaviors, and by extension, their experiences of stress.

The forms of emotional labor performed by workers are influenced by socio-cultural as well as political-economic factors (Ashkanasy, 2003; Brown et al., 2023). For instance, as postindustrial economies further transition to service work, emotional labor will become a greater part of workers' duties and responsibilities (Tsang, 2011). In such contexts, emotional displays are not only an integral part of service workers' job duties but also become a commodity that itself is sold to consumers (e.g., “service with a smile”; Hochschild, 1983). Hochschild's original scholarship among flight attendants explicitly calls attention to the emotional labor performed by women in historically feminized professions (Benesch and Prior, 2023), however, as critics note, the increasing number of men in service positions draws attention to how men must also contend with expectations to manage their emotions (Cameron, 2000). And, as discussed above, emotional labor is also “racialized” as emotional responses may be interpreted differently depending on the racial identity of the person performing them (Evans and Moore, 2015; Leonardo and Zembylas, 2013). As Matias (2016) has shown, emotions such as pity or sympathy may be utilized by White educators in efforts to avoid deeper discussion about racial privilege and structural disadvantage.

Research questions

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the stress it entailed, it is crucial to understand the forms of emotional labor performed by educators. To this end, this study draws on qualitative data gathered from 88 educators in New York State to investigate the following research questions:

(1) What emotions did educators experience during the pandemic, and what forms of emotional labor did they perform?

a. What display rules guided educators' expression of emotion?

(2) How did the emotional labor performed by educators relate to their reported stress levels?

Methods

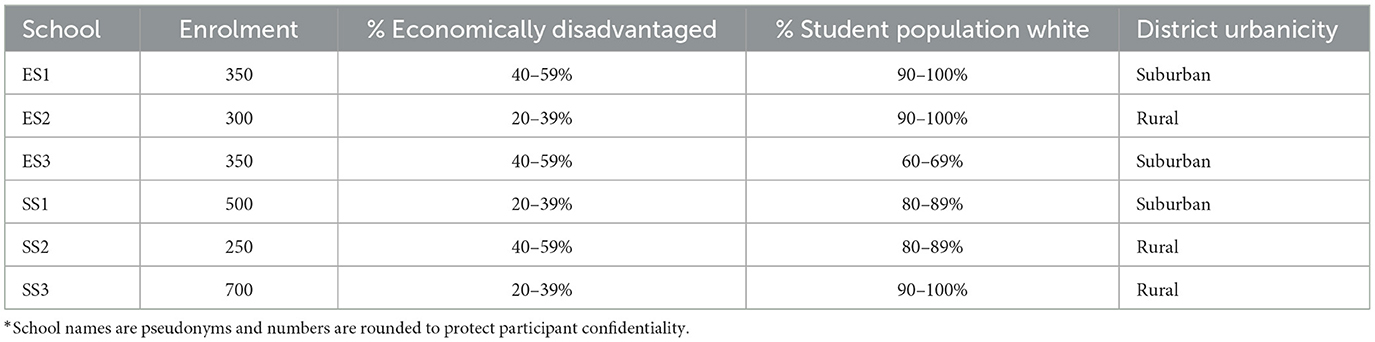

Six schools were recruited for this study using a statewide survey conducted in spring of 2021 which explored educators' experiences of stress and job satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic (Wilcox et al., 2021). From the larger sample of schools (n=38) that participated in the survey, six schools were invited to participate in the second phase of study as participants in these schools reported lower rates of stress and higher rates of job satisfaction compared to educators in schools serving demographically similar populations. The logic of this sampling choice was to inquire into what might have mitigated educators' stress and positively influenced their job satisfaction. This purposive sample was also designed to represent a range of community and school demographics including taking into consideration such factors as urbanicity, school level, and student population served (see Table 1). Despite our attempt to investigate a representational sample of New York State educators, the 38 schools that participated served largely White student populations, posing a limitation to the study which we discuss in further detail in the final sections of this paper. Qualitative research often poses limitations for the sample sizes involved, yet its strength lies in its ability to provide a space for participants to articulate firsthand their experiences of a particular phenomenon. In this case, we aimed to elevate the voices of educators who expressed, in their own words, their experiences during the pandemic and factors which exacerbated and mitigated their stress levels.

Data collection

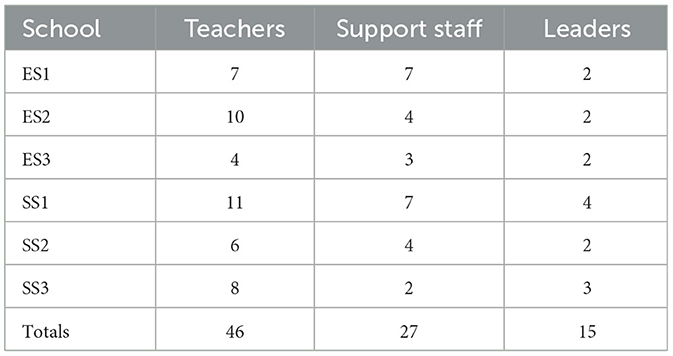

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was granted by the researchers' university (study 21E027), and all participants underwent informed consent procedures prior to data collection. After securing school and district permission, in-person site visits were conducted from June 2022 through November 2022 by an interdisciplinary research team comprised of university researchers and two doctoral students certified in Human Subjects research by the IRB. During visits, researchers conducted interviews and focus groups with teachers, support staff members (school counselors, school psychologists, and social workers) and school and district leaders (see Table 2). A total of 88 educators (including classroom teachers and support staff) across the six schools participated in the study and they are the focus of this study. To maintain confidentiality, we refer to schools by ES (elementary school) or SS (secondary school) and have rounded off the demographic statistics of each school (see Table 1).

Our research team crafted and used interview and focus group protocols informed by several lines of inquiry (leadership, curriculum and instruction, social-emotional learning, youth mental health, and parent-family engagement) with a focus on literature related to adaptation during crises (Yin, 2018). While portions of each protocol differed slightly depending on the role of the participant, we maintained the same themes across all interviews to be able to compare responses across staff members. The interview and focus group questions below were asked to all participants and participants' responses serve as the primary data sources for this analysis1:

1. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic (spring of 2020), please describe some of the major issues you have encountered as an educator.

a. Focusing on an example, please share:

i. How did you address this issue?

ii. Who else was involved in addressing this issue?

iii. How did you communicate with (or get input from) those affected most directly by this issue?

iv. What were/have been your lessons learned in addressing this issue?

v. [For leaders only]: What kinds of measures or actions did you take to mitigate negative effects of this issue on your staff?

2. How would you characterize how and to what extent the pandemic and your experience of it in this school has impacted your levels of stress at work, your job satisfaction and/or your future career plans?

a. What kinds of things have helped or hindered you to manage your stress, job responsibilities, and work-life balance?

b. What do you wish you had more of in terms of resources or support to do your job during these times?

Our research team used recommended practices (see Brinkman and Kvale, 2014) to increase the trustworthiness of qualitative research studies in several ways. First, two or more interviewers were engaged in each site visit and in the process of interpretive memoing. The interpretive memos were crafted during and after site visits and invited the research team to consider the overarching themes that emerged during interviews and focus groups and engage in researcher triangulation as team members shared varied interpretations of the data. These memos provided opportunities to reflect on the ways in which our identities and positions impacted data collection and our interpretations of the data probing into, for example, discrepancies in our interpretations (Creswell and Poth, 2023). This was essential, since our class and race positions provided us with advantages which may not have been shared by participants and the students they served. Although these memos and the conversations which they facilitated cannot eliminate bias, our overall goal in this research was to use recommended strategies as outlined above to ensure the trustworthiness of our interpretations and amplify the voices of the educators in this study. We revisit limitations of our findings in the final sections of the paper.

Data analysis

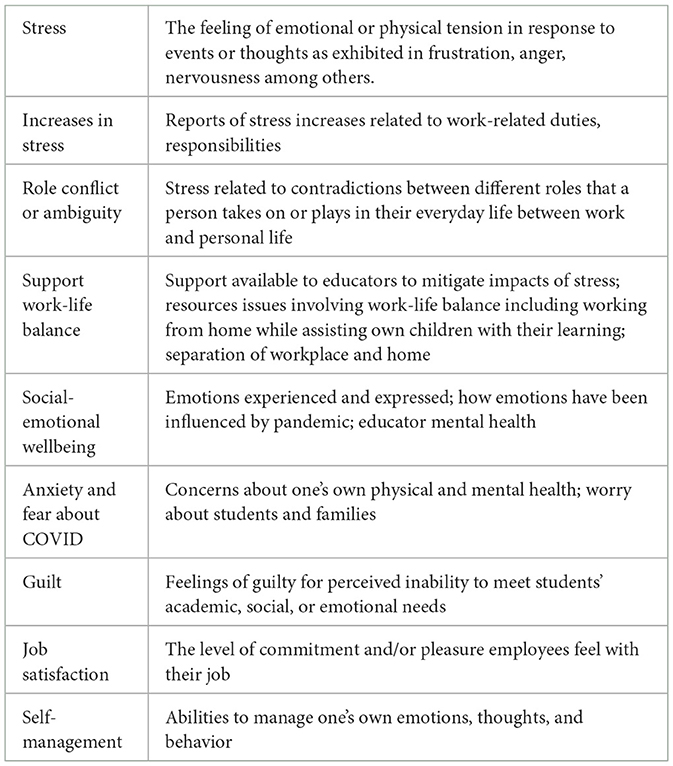

Next, our research team members confirmed the accuracy of interview and focus transcriptions through multiple listenings. Team members utilized NVivo 12 qualitative software (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) to code data using the constant-comparison method whereby parent codes are first created from the lines of inquiry and literature review, and more specific subcodes are then developed through inductive coding (Miles et al., 2014). After reviewing code reports, research team members crafted individual school case studies and to enhance credibility, we engaged in member-checking with principals of participating schools (which resulted in only minor edits such as corrected acronyms; Maxwell, 2012).

For this study, data coded in parent codes related to stress, job satisfaction, school climate and culture, and social-emotional wellbeing were further examined through the lens of emotional labor resulting in subcodes including guilt, self-management, and anxiety. Intercoder reliability tests were not appropriate at this stage of analysis as only the lead author conducted this phase of coding, however, as the primary coder the lead author took steps to increase validity by writing reflexive memos during the coding process and consulting with other researchers involved in the data collection process to confer about preliminary findings. A portion of the codebook used in this analysis and a sample of coded text is available in Appendices A, B in order to illustrate the coding process.

Positionality statement

To dispel notions of the “detached observer” (Rosaldo, 1993), we seek to clarify how our identities, interests, and backgrounds may have influenced this research project. As White, middle-class university researchers, our upbringing may not have matched those of our participants and thus affected our ability to understand firsthand their experiences. This is especially true for the lead author as a male with no K-12 school teaching experience (as compared to the co-author who is female and has public-school teaching experience). Second, we do not claim to be neutral as our intent with this research is not simply to describe the challenges faced by educators but also improve their experiences and capacities to support their students. While these limitations may have impacted participants' interactions with us and our interpretation of the collected data, we feel that the efforts described above aimed at increasing trustworthiness and rigor have been effective in mitigating potential biases. As qualitative educational researchers, our goal is to amplify the voices of educators and learn from their experiences; we hope this paper has contributed to that effort.

Findings

As the findings below illustrate, participants struggled to manage increasing emotions of stress and discontent during the pandemic. Educators recounted intense feelings of worry and concern about their students, especially during school closures, as well as guilt for their perceived inability to support students more directly. Despite these challenges, educators expressed the urge to mask negative emotions in front of their students and maintain a positive emotional display. Collegial support emerged as a crucial resource which participants drew on to manage their emotions in this highly stressful context.

Stress, worry, and guilt

In interviews and focus groups, educators described increasing levels of stress and discomfort during the pandemic and described experiences of emotional labor. Many educators, for instance, explained how they struggled to meet new teaching demands initiated during the rapid transition to remote learning. Educators not only felt unprepared to utilize the technology needed to teach remotely but also that this shift undermined their self-efficacy and confidence. As two teachers from ES3, an elementary school situated in a suburb of New York's capital city, Albany, explained:

Teacher 1: So I went from where I was confident in the classroom—because I knew how to do and I knew how to get the academics across to my kids, and you know and do the best I could to now I have these kids in front of me and they're relying on me. And their parents are relying on me to continue to educate them. And I don't know what I'm doing.

Teacher 2: You feel incompetent and like I am completely overwhelmed, and I do not know how to engage them because I'm not engaged... I'm like two seconds ahead of them or you have kids telling you what to do: “[Teacher's name] you know you can just push that button down there.” I mean, it's crazy. It was just crazy.

Like the two teachers above, a district leader from ES2, a rural school located at the foot of the Adirondack Mountains in New York, explained how many teachers in their district experienced “pain and frustration” as they felt unable to meet their own high standards during the pandemic:

But [teachers] weren't satisfied with doing anything less than what they normally do. So a lot of their pain and frustration came from “I'm not being the teacher that these kids deserve. Whether it's to the kids in front of me or the kids at home when I have them both. I can't be my best to any of them.” Which, again, just shows that commitment and dedication, but that was the hard part.

Especially during periods of remote learning, many educators felt that they were unable to teach effectively and moreover could not support their students emotionally. During an interview, another teacher from ES6 elaborated on the challenges of teaching through the pandemic:

It was really hard knowing that you were failing your students and you tried and tried. But you also had to put yourself in the shoes of those families and they were really just trying to survive and have their basic needs met. If they weren't able to sign in every day you were just checking in to make sure if everything was okay, if there was anything we could do to help the family out. That was really just tough.

Other participants recounted similar feelings of worry and concern about students' wellbeing especially when schools were closed. “It was super emotional for us, because we wanted to keep abreast of the kids,” said one teacher from SS1, a secondary school located in a suburb of the city of Utica. At SS3, a school classified as rural though located just seven miles east of a small city in New York, a support staff member expressed concern about youth living in precarious situations and worried when she could not keep tabs on them:

And [we] worry, and then where are they? And knowing the environments that some kids go [home] to, and school was their safe place. And when they're not connecting with you online, you know, where are they? Are they okay? Are they eating? Are they safe?

An educator from ES3 likewise explained how she had lost sleep because she was unable to confirm one students' safety. “Those are the families that we worried about, like, I know, both of us [her husband] stayed up at night thinking about this little girl, and just worried about her and, was she with mom and dad, or was she with grandma?” she explained.

Leaders also recounted feelings of stress and guilt, however, these feelings were often in relation to their perceived inability to support staff during the pandemic and the need to enforce mandates which were unpopular (Grissom and Condon, 2021; LaVenia et al., 2024). A district leader from SS3 reflected on the “horrible” feeling of watching staff members experiencing stress and negative emotions:

I felt horrible that the employees were stressed, horrible. I kept writing to them, “If you need anything, please let us know. What can I do? Can I cover your class?” like those kinds of things because you could see them crumbling, you could see the stress. You know, in some cases, people gained weight, in some cases they lost weight and lost family members. You could just see they were wearing it, and unhappy employees aren't good for kids. So I felt that stress to try to make people feel happy.

“Surface acting” during a pandemic

The data above demonstrate how educators experienced stress, guilt, and worry during the pandemic. In this section, we describe how educators in this study felt the need to mask these emotions in front of students. Through the lens of emotional labor, we explore how this “display rule” encouraged educators to engage in “surface acting” (Hochschild, 1983; Zheng et al., 2024a) by showing positivity despite their actual feelings.

In interviews and focus groups, educators made clear the connection they felt between their own emotions and the way those emotions impact students in their schools. For instance, in describing the school community, a support staff member from ES2 drew a correlation between staff members' emotions and those of their students. “This building is a happy place, our kids run into the building in the morning. And I think in large part, that's because our staff is happy to be here too,” she said. At ES2, this notion extended to the pandemic, as educators were quick to recognize the way that their own emotional displays could influence students. For instance, in a focus group with support staff members, educators expressed the need to mask their actual feelings of stress and discomfort in front of students:

Support Staff 1: I think, too, our staff did a really good job of even though they might have been anxious, they didn't act that way in the classroom. And that rubs off on the kids, you know, they noticed that. The teachers were very much like, “Okay, that's going to be okay, we're okay, this is what we're doing.” And so even though that may not have been what was really going on in their heads, they made this really conscious effort to make the kids be like, you know, we got this we know things are different. I feel like that really helped.

Support Staff 2: I agree. I think that was a real anchor for the kids. And for the families, too.

Educators at other schools described similar forms of “surface acting” where they felt the urge to mask their actual emotions in front of students. A teacher from SS3, for instance, explained the challenge she faced managing emotions in front of students and the tacit explanation for educators at her school overcome obstacles simply through individual grit and perseverance:

[School name] teachers, just, you know, can find their boots, they pull them up, you know, put your big girl pants on and you just do it. But I think I'm to the point where, like, I'm done, you know, like, I'm like, hoping to survive two more years, so I can retire. I mean, that's, and I never really thought like that. I mean, we've gone through other stressful times in this district, but this is, you know, emotionally stressful. And there's just some times that I have to go and take a deep breath, count to 10, you know, even with them [students] in the room, because it's, you know, but I think we mask it.

Leaders also performed emotional labor during the pandemic, though—as implied in the previous section—their emotional labor typically involved managing emotions during interactions with staff, community members, and students' families (LaVenia et al., 2024). For instance, the principal of ES10 described the challenge of communicating with teachers and family members who were unhappy with decisions involving school closures or social distancing mandates:

There was a lot of emotion. It was the most stressful year of my life as an administrator—there's no doubt. People were angry. People were frustrated. They were upset about things. And it was really just trying to maintain calm. You know, not allow somebody's emotion to elevate my emotion. Because man, it would have been really easy.

The principal from SS2, for example, explained his need to maintain a positive attitude in front of students and staff despite feeling “spent”:

I didn't want them to see that I was spent. No, it means you're always trying to just to have that game face on. Try to be as positive as possible. Because everyone, like, you'll get through this. We got it. They'll be alright.

An important finding which emerged from these data was that educators did not feel it was administrators or other leaders who imposed the display rule of positivity, but rather was an implicit expectation that was part of educators' job duties. As a support staff from SS3 explained:

[My] husband works for the state. And you know, the expectations weren't the same that was placed on educators. Educators, I felt there was a high expectation that you're going to just keep this going. And you don't have the tools to do that. And that's not coming from administration.

A similar sentiment was articulated by an educator from ES1 who suggested that it was educators themselves who imposed these high standards, “Our expectations for our community weren't too high and unmanageable, and then that trickled to us too.” He then continued, “But as educators, we hold ourselves to a higher standard. So we did that ourselves. I don't think administration pushed that onto us, which was super helpful.” Likewise, another educator from SS3 described the pressure of maintaining a “high standard” for their students despite feeling uncertain they would be able to meet these expectations:

In talking with some colleagues after going through that [remote instruction], and then coming back this year where, “okay, we're back to normal” where it's not normal. We still came back with masks, we still came back social distancing…. And I feel a lot of that was carried into this year that you still have to be the strong person when you're like, wait, I'm still like, I still have PTSD, literally from, you know, the previous year. So I feel like that was really hard. And I can't say it's a fault of, I don't think we're unique in that. I think it's education. I feel the educational system just had a really, there was a high standard a high demand to not cut our stockholders short, which are students, right, in the community. And I think for the most part we rose to the occasion the best we can. But I don't think anybody would say we did a great job. I mean, people tell us we did but nobody feels like they did it.

Emotional labor and the role of colleagues

An important way educators managed their emotions during the pandemic was through support of colleagues (Schiller et al., 2023). These findings validate previous work highlighting the potential for collegial relationships to offset workplace stress among teachers (e.g., Kelchtermans, 2006; Shah, 2012; Vangrieken et al., 2015).

Educators explained how their colleagues assisted them not only with academic guidance or technical assistance but with crucial emotional support during challenging moments. “I really relied on my coworkers to help me get through it and to give me advice and help with the academics and the management and all of that,” said a teacher from ES2. When asked what things helped him handle the challenges of the pandemic, another teacher from ES2 pointed to his colleagues as creating a crucial space where he could express his actual emotions rather than needing to engage in the types of “surface acting” (Hochschild, 1983) described above:

And you know what else, it's like when the kids left and if you just lost it, you were like, it was just a brutal day. And you just lost your junk… Like you can lose it, and you could lose it with your colleagues, and it was okay. You could be angry, frustrated, mad at the world. And it was okay to be angry, frustrated, mad, or mad at the world. Because if we weren't allowed to be that, then we couldn't have come back and restarted every day.

A teacher from SS3 had a similar reply when describing the supports and resources on which he could draw during the pandemic. In his view, colleagues provided a way to collectively acknowledge the challenges they faced even if they felt their struggles, in other contexts, fell on “deaf ears”:

And just being able to talk to colleagues, acknowledging that you're not alone, that you're in it with everybody else. Even if you feel like the voice of the teachers is kind of falling on deaf ears at times, just being able to be there for each other I think has been important.

In many cases, educators explained how colleagues helped them cope with challenging situations which were not only related to their job duties but also stemmed from personal difficulties. For instance, during a teacher focus group at ES1, three teachers recalled how their colleagues helped mitigate stress from both work and non-work related sources:

Teacher 1: I've called her [the principal] crying. I felt comfortable to just say… this is happening. It [the principal's response] was just, “Do your best.”

Teacher 2: And the times she talked you off ledges at 7 in the morning.

Teacher 3: I was going through a lot in my personal life. And this is what I had that was a foundation. Like when everything else seemed to be like I don't know… I don't know. I still had the school, and I didn't fear for my job, so I was able to keep doing my best.

Likewise, the principal at SS2 explained how a meeting with principals across the district began with the intent of sharing leadership strategies during the pandemic and morphed into a support group:

[T]hen we meet as a principal group. And a lot of times just to vent. Just to vent. Sometimes there's just telling jokes, we would realize, because we did, and we had an administrator who left with mental health leave. And so, we're trying to help him, and we could see stress levels rising. So, we'd be like, hey, we need to meet quick, and we just need a group for maybe 15 minutes, and just tell [name of principal at nearby school] to do something nice to get some just to get some laughter.

During a focus group among support staff members at ES1, participants recounted a similar experience of mutual support during the pandemic and a feeling of trust and comfort sharing problems which may not have been school related.

Support Staff 2: You know, everyone was very generous with their time, they had their own classes, and their own whatever, but they were like we are all on the same sinking ship together, you had no problem texting someone at ten o'clock, “Can you talk now? “Sure, call me.” … There was no, we don't have time for that or we aren't getting paid enough. It was never like that in this building.

Support Staff 3: No, it wasn't.

Support Staff 2: How could we pull the other one up on the ship?

Support Staff 3: Someone's going off the deep end. You gotta help [teacher name], she's sinking.

Support Staff 1: I mean I was going to retire last year, I keep trying to, but these two [Support Staff 2 and Support Staff 3] keep pulling me off the ledge.

A teacher from ES2 described feeling anxiety and nervousness that many educators experienced as schools began to reopen again, yet explained how colleagues mutually supported one another during this stressful time. Such moments are important reminders that positive emotions—when felt authentically—can serve to mitigate stress and promote resilience (Caprara et al., 2017; Humphrey et al., 2015):

Everybody knew how to pull on each other's strength. And if I was personally completely freaked out over the fact that we were all going to be back together again, other people were feeling the same thing, and we were feeding off of each other's, “We're going to make it, we're going to do it, we can make this happen.”

As these findings demonstrate, colleagues were a crucial source of emotional support for those struggling during the pandemic. Colleagues not only assisted educators with meeting new job demands such as the technology required for remote teaching, but also helped them cope with the stress and adverse emotions they were experiencing during the pandemic. Importantly, colleagues also provided spaces for educators to “vent” or express their actual emotions rather than feeling the need to mask them as they did in front of students.

Discussion and conclusion

The findings above demonstrate that educators experienced a range of challenging emotions and stressful conditions during the pandemic. As found in other studies, educators in this study contended with their feelings of concern about their students and guilt that they could not adequately meet their needs during the pandemic (Bintliff, 2020; Herman et al., 2021). In particular, the rapid shift to remote teaching left many educators feeling unprepared and doubting their teaching effectiveness (Auger and Formentin, 2021). These concerns, along with the challenges of engaging students remotely, dampened the joyful and rewarding aspects of teaching that prior research has correlated with teacher job satisfaction and retention (Hargreaves, 2021). Educators reported struggling to manage the expression of these emotions in ways which conformed to workplace norms, or display rules, which prescribed positivity in front of students. Lastly, we described how colleagues served as important sources of support for educators by creating spaces for them to express their felt emotions and vent frustrations.

Several implications may be drawn from these findings. First, this study highlights the centrality of emotions in educators' work as well the utility of emotional labor as a conceptual framework to examine how educators manage emotions in various contexts. As our data demonstrate, educators felt pressured to confirm to display rules which urged them to mask their negative emotions in front of students. Yet, as educators explained, it was not leaders or administrators who enforced this display rule, but educators themselves who described an internalized expectation that they express positivity in front of students no matter the situation. Such findings highlight the need for continued study of how educators internalize, resist, and transform socially constructed notions of the “good” educator (Zembylas, 2007). Moreover, the way emotional display rules may be communicated and enforced to educators implicitly calls attention to the complicated ways in which service workers are (self-)disciplined in a postindustrial economy (Horner et al., 2020).

Second, the significance of collegial relationships was made clear through interviews and focus groups in this study (Vangrieken et al., 2015). Colleagues provided not only a source of emotional support for one another but also created spaces where educators felt they could express their emotions more authentically and resist both surface acting and deep acting. These findings coincide with prior research which has found that collegial relationships may help offset workplace stress and burnout (Kelchtermans, 2006; Shah, 2012). Yet, while their solidarity is admirable, supportive colleagues alone cannot be responsible for mitigating educators' stress. Additional practices to alleviate educator stress should include access to mental health counseling from trained professionals, mindfulness practices, and mentorship programs in combination with an ease in educators' workloads (Jakubowski and Sitko-Dominik, 2021; Sharplin et al., 2011). For instance, LaVenia et al. (2024) suggest that educators may be supported through the development of “communities of emotional practice” which provide colleagues with ways to mutually support one another especially in expressing and managing emotions.

Third, though we organized our findings thematically—and not by educator role—it is important to note the varied forms of emotional labor performed by educators in different positions. For instance, while participants across different roles exhibited forms of surface acting, we found that, for leaders, these instances often involved family members and teachers. Indeed, this paper echoes recent scholarship which found that—like teachers—leaders incurred high levels of stress and burnout during the pandemic (Grissom and Condon, 2021; LaVenia et al., 2024). Such findings remind us that educator workforce shortages facing districts across the U.S. also include leaders who in our study also performed emotional labor as they attempted to buffer other staff from stressors (Wilcox et al., 2024; DeMatthews et al., 2022).

Lastly, while this study has critically explored the ways in which positivity operated as a display rule for educators, we do not mean to suggest positive thinking is intrinsically a bad thing. For instance, other scholarship generated from this study noted how some participants experienced positive emotions during the pandemic such as a sense of pride and accomplishment that they felt from overcoming adversities and renewed enthusiasm for the possibilities to adapt and innovate during the pandemic (Wilcox et al., 2022). As this scholarship (and the quote at the end of the findings section) illustrates, positive emotions may promote resilience among educators and be beneficial to both them and their students when they are felt authentically (Sutton and Wheatley, 2003). Framed through the lens of emotional labor, educators may reap benefits when they are engaged in deep acting rather than surface acting (Caringi et al., 2012; Hochschild, 1983). Although maintaining a positive view during stressful times may mitigate harmful impacts in the near term, this approach may obscure deeper, structural changes which may be needed to attain desired outcomes in the long term (e.g., teacher job satisfaction and retention; Collinson, 2012; Pascoe, 2023). Moreover, it is crucial that calls for post-COVID-19 pandemic positivity is not accompanied by a return to the status quo which overlooks significant inequities associated with other pandemics (e.g., of systemic racism) that continue to disadvantage marginalized and vulnerable youth (Holmes et al., 2021; Ladson-Billings, 2021). Citing the Holocaust survivor and psychologist Frankl, Gotlib (2021), proposes we adopt a “tragic optimism” which seeks to acknowledge the many tragedies of the pandemic as an imperative to improve ourselves and our society.

Ultimately, this study calls attention to the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic induced school disruptions on educators' emotions and stress levels with specific attention to how educators managed emotions (specifically display rules) that compelled them to mask signs of stress and maintain a positive attitude. As stress and emotional burnout are closely linked with turnover and attrition, it is crucial that educators are provided with outlets to express their genuine feelings while also having access to resources and supports which can reduce their stress levels (Li and Yao, 2022). Although supportive and responsive leaders who acknowledge teachers' challenges without imposing unrealistic expectations have been found to reduce the stress and improve the wellbeing of educators (Prilleltensky et al., 2016), leaders in this study, also experienced increases to their stress levels and struggled to manage their emotions (Grissom and Condon, 2021; LaVenia et al., 2024). Facilitating conditions which provide “psychic rewards” that educators gain from the joy and excitement of teaching can potentially help retain teachers in districts where shortages are occurring (Lortie, 1975). However, such efforts should not overlook tangible incentives—such as higher pay and secure employment—which are crucial considerations for educators who are considering leaving the field or for young adults contemplating a career in teaching (McCarthy et al., 2022). Educators must also be provided with the necessary resources they need to meet their job demands. Even as educators were being hailed as “essential workers,” (Beames et al., 2021) they were often unable to meet the increasing duties of their jobs thus causing a mismatch between job demands and the tangible and intangible resources at their disposal to meet these new demands (Leo et al., 2023; Bakker and Demerouti, 2017). These endeavors are imperative not only to ensure educators are supported but also to ensure that the needs of the students they serve will be met now, and in the future, when inevitable adversities will be encountered (Schonert-Reichl, 2017).

Limitations

Several important limitations to this study must be mentioned. Despite our efforts to recruit a range of schools, rural and suburban schools serving majority White student populations are overrepresented in this study. It is crucial that additional research examines the experiences of educators working in urban settings and those serving more ethnically diverse populations especially considering the disproportionate impacts of the pandemic on racialized minorities (Baker et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2023). Such work can help elucidate the different forms of emotional labor performed by educators working in varied contexts. Generalizations drawn from this study must therefore be made with care as it is possible educators in other locations may have had different experiences of emotional labor than those who participated in this study. In line with Zembylas' (2007) notion of an “emotional ecology,” these data must be situated in both the immediate and broader contexts in which they were collected.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available in order to protect participants' identities.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University at Albany (SUNY), Institutional Review Board (Office of Regulatory & Research Compliance). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^A detailed report on the full methods and procedures used for this project is available on the researchers' website: https://ny-kids.org/wp-content/uploads/NYKids-COVID-Response-Study-Phase-II-Methods-Procedures.pdf.

References

Ahmad, A., and Safaria, T. (2013). Effects of self-efficacy on students' academic performance. J. Educ. Health Commun. Psychol. 2, 22–29.

Ahorsu, D. K., Lin, C. Y., and Pakpour, A. H. (2020). The association between health status and insomnia, mental health, and preventive behaviors: the mediating role of fear of COVID-19. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 6:2333721420966081. doi: 10.1177/2333721420966081

Aldrup, K., Carstensen, B., and Klusmann, U. (2024). The role of teachers' emotion regulation in teaching effectiveness: a systematic review integrating four lines of research. Educ. Psychol. 59, 89–110. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2023.2282446

Alessandri, G., Caprara, G. V., and Tisak, J. (2012). The unique contribution of positive orientation to optimal functioning: further explorations. Eur. Psychol. 17, 44–54. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000070

Allen, B. (2021). Emotion and COVID-19: toward an equitable pandemic response. J. Bioeth. Inq. 18, 403–406. doi: 10.1007/s11673-021-10120-4

Allen, U., Collins, T., Dei, G. J., Henry, F., Ibrahim, A., James, C., et al. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 in Racialized Communities. Ottawa, ON: Royal Society of Canada.

Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., Karataş, Z., Kabasakal, Z., and Kılınç, M. (2020). Meaningful living to promote complete mental health among university students in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 20, 930—942. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00416-8

Ashkanasy, N. M. (2003). “Emotions in organizations: a multi-level perspective,” in Multi-level issues in Organizational Behavior and Strategy, eds. F. Dansereau and F.J. Yammarino (Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 9–54. doi: 10.1016/S1475-9144(03)02002-2

Ashkanasy, N. M., and Dorris, A. D. (2017). Emotions in the workplace. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 4, 67–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113231

Auger, G. A., and Formentin, M. J. (2021). This is depressing: the emotional labor of teaching during the pandemic spring 2020. Journal. Mass Commun. Educ. 76, 376–393. doi: 10.1177/10776958211012900

Baker, C. N., Peele, H., Daniels, M., Saybe, M., Whalen, K., Overstreet, S., et al. (2021). The experience of COVID-19 and its impact on teachers' mental health, coping, and teaching. School Psych. Rev. 50, 491–504. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2020.1855473

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 1–13. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056

Bandura, A. (1994). “Self-efficacy,” in Encyclopedia of Human Behavior, Vol. 4, ed. V. S. Ramachaudran (New York, NY: Academic Press), 71–81.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., and Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children's aspirations and career trajectories. Child Dev. 72, 187–206. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00273

Bartlett, L., Oliveira, G., and Ungemah, L. (2018). Cruel optimism: migration and schooling for Dominican newcomer immigrant youth. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 49, 444–461. doi: 10.1111/aeq.12265

Beames, J. R., Christensen, H., and Werner-Seidler, A. (2021). School teachers: the forgotten frontline workers of COVID-19. Austral. Psychiatry 29, 420–422. doi: 10.1177/10398562211006145

Benedetti, F. (2020). Placebo Effects. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198843177.001.0001

Benesch, S. (2018). Emotions as agency: feeling rules, emotion labor, and English language teachers' decision-making. System 79, 60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.03.015

Benesch, S., and Prior, M. T. (2023). Rescuing “emotion labor” from (and for) language teacher emotion research. System 113:102995. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2023.102995

Berlant, L. (2010). “Cruel optimism,” in The Affect Theory Reader, eds. M. Gregg and G. Seigworth (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), 93–117. doi: 10.1215/9780822393047-004

Bintliff, A. (2020). How COVID-19 has influenced teachers' well-being. Psychology Today, September 8.

Brinkman, S., and Kvale, S. (2014). Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Interviewing, 3rd Edn. London: Sage.

Brotheridge, C. M., and Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: comparing two perspectives of “people work”. J. Vocat. Behav. 60, 17–39. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.2001.1815

Brown, E. L., Horner, C. G., Kerr, M. M., and Scanlon, C. L. (2014). United States teachers' emotional labor and professional identities. KEDI J. Educ. Policy 11, 205–225. doi: 10.22804/kjep.2014.11.2.004

Brown, E. L., Stark, K., Vesely, C., and Choe, J. (2023). “Acting often and everywhere:” teachers' emotional labor across professional interactions and responsibilities. Teach. Teach. Educ. 132:104227. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104227

Burić, I., and Frenzel, A. C. (2021). Teacher emotional labour, instructional strategies, and students' academic engagement: a multilevel analysis. Teach. Teach. 27, 335–352. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2020.1740194

Burić, I., Kim, L. E., and Hodis, F. (2021). Emotional labor profiles among teachers: associations with positive affective, motivational, and well-being factors. J. Educ. Psychol. 113, 1227–1242. doi: 10.1037/edu0000654

Burt, K. G., and Eubank, J. M. (2021). Optimism, resilience, and other health-protective factors among students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Effect. Teach. Higher Educ. 4, 1–17. doi: 10.36021/jethe.v4i1.206

Cameron, D. (2000). Styling the worker: gender and the commodification of language in the globalized service economy. J. Sociolinguist. 4, 323–347. doi: 10.1111/1467-9481.00119

Caprara, G. V., Alessandri, G., and Eisenberg, N. (2012). Prosociality: the contribution of traits, values, and self-efficacy beliefs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102:1289. doi: 10.1037/a0025626

Caprara, G. V., Eisenberg, N., and Alessandri, G. (2017). Positivity: the dispositional basis of happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 18, 353–371. doi: 10.1007/s10902-016-9728-y

Caringi, J. C., Lawson, H. A., and Devlin, M. (2012). Planning for emotional labor and secondary traumatic stress in child welfare organizations. J. Fam. Strengths 12, 11–31. doi: 10.58464/2168-670X.1139

Cerulo, K. A. (2019). Never Saw it Coming: Cultural Challenges to Envisioning the Worst. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Chang, M. L., Gaines, R. E., and Mosley, K. C. (2022). Effects of autonomy support and emotion regulation on teacher burnout in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 13:846290. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.846290

Chen, J. (2016). Understanding teacher emotions: the development of a teacher emotion inventory. Teach. Teach. Educ. 55, 68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.001

Collinson, D. (2012). Prozac leadership and the limits of positive thinking. Leadership 8, 87–107. doi: 10.1177/1742715011434738

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2023). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Curchin, E., Dahill-Brown, S., and Lavery, L. (2024). Reckoning with the “other” pandemic: How teachers' unions responded to calls for racial justice amidst COVID-19. Educ. Res. 53, 296–307. doi: 10.3102/0013189X241235634

Darling-Hammond, L. (2022). Reimagining American education: possible futures: the policy changes we need to get there. Phi Delta Kappan 103, 54–57. doi: 10.1177/00317217221100012

de Ruiter, J. A., Poorthuis, A. M., and Koomen, H. M. (2021). Teachers' emotional labor in response to daily events with individual students: the role of teacher–student relationship quality. Teach. Teach. Educ. 107:103467. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103467

DeMatthews, D. E., Knight, D. S., and Shin, J. (2022). The principal-teacher churn: understanding the relationship between leadership turnover and teacher attrition. Educ. Admin. Q. 58, 76–109. doi: 10.1177/0013161X211051974

Dolinski, D., Dolinska, B., Zmaczynska-Witek, B., Banach, M., and Kulesza, W. (2020). Unrealistic optimism in the time of coronavirus pandemic: may it help to kill, if so—whom: disease or the person? J. Clin. Med. 9:1464. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051464

Ehrenreich, B. (2009). Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking has Undermined America. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

Evans, L., and Moore, W. L. (2015). Impossible burdens: white institutions, emotional labor, and micro-resistance. Soc. Probl. 62, 439–454. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spv009

Fan, J., and Wang, Y. (2022). English as a foreign language teachers' professional success in the Chinese context: the effects of well-being and emotion regulation. Front. Psychol. 13:952503. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.952503

Ferreira, M. J., Sofia, R., Carreno, D. F., Eisenbeck, N., Jongenelen, I., and Cruz, J. F. A. (2021). Dealing with the pandemic of COVID-19 in Portugal: on the important role of positivity, experiential avoidance, and coping strategies. Front. Psychol. 12:647984. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647984

Frenzel, A. C., Daniels, L., and Burić, I. (2021). Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students. Educ. Psychol. 56, 250–264. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2021.1985501

Gallant, A. (2013). “Self-conscious emotion: how two teachers explore the emotional work of teaching,” in Emotion and School: Understanding How the Hidden Curriculum Influences Relationships, Leadership, Teaching and Learning (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing), 163–181. doi: 10.1108/S1479-3687(2013)0000018013

Gardner, J., and Slattery, M. (2024). Overcoming the Teacher Shortage: Recruitment, Retention, and Cost Strategies [Presentation]. New York City, NY: New York State School Board's Association Annual Convention & Education Expo.

Gassen, J., Nowak, T. J., Henderson, A. D., Weaver, S. P., Baker, E. J., Muehlenbein, M. P., et al. (2021). Unrealistic optimism and risk for COVID-19 disease. Front. Psychol. 12:647461. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647461

Gotlib, A. (2021). Letting go of familiar narratives as Tragic Optimism in the era of COVID-19. J. Med. Human. 42, 81–101. doi: 10.1007/s10912-021-09680-8

Grissom, J. A., and Condon, L. (2021). Leading schools and districts in times of crisis. Educ. Res. 50, 315–324. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211023112

Guenther, A. R. (2021). “It should be helping me improve, not telling me I'm a bad teacher”: the influence of accountability-focused evaluations on teachers' professional identities. Teach. Teach. Educ. 108:103511. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103511

Hamilton, L., and Doss, C. (2020). Supports for Social and Emotional Learning in American Schools and Classrooms: Findings from the American Teacher Panel. RAND Corporation. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA397-1.html (Accessed February 10, 2022).

Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotional practice of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 14, 835–854. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00025-0

Hargreaves, A. (2001). Emotional geographies of teaching. Teach. Coll. Rec. 103, 1056–1080. doi: 10.1111/0161-4681.00142

Hargreaves, A. (2021). What the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us about teachers and teaching. Facets 6, 1835–1863. doi: 10.1139/facets-2021-0084

Hartney, M. T., and Finger, L. K. (2020). Politics, Markets, and Pandemics; Public Education's Response to COVID-19 (EdWorkingPaper No. 20–304). Providence, RI: Annenberg Institute at Brown University. doi: 10.1017/S1537592721000955

Hassan, S., and Daniel, B. J. (2020). During a pandemic, the digital divide, racism and social class collide: the implications of COVID-19 for black students in high schools. Child Youth Serv. 41, 253–255. doi: 10.1080/0145935X.2020.1834956

Herman, K. C., Sebastian, J., Reinke, W. M., and Huang, F. L. (2021). Individual and school predictors of teacher stress, coping, and wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. School Psychol. 36:483. doi: 10.1037/spq0000456

Hirshberg, M. J., Davidson, R. J., and Goldberg, S. B. (2023). Educators are not alright: mental health during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 52, 48–52. doi: 10.3102/0013189X221142595

Hochschild, A. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Holmes, C., Krautwurst, U., Graham, K., and Fernandez, V. (2021). “No silver bullet solution”: cruel optimism and Canada's COVID-19 public health messages. Anthropologica 63, 1–20. doi: 10.18357/anthropologica6312021326

Horner, C. G., Brown, E. L., Mehta, S., and Scanlon, C. L. (2020). Feeling and acting like a teacher: reconceptualizing teachers' emotional labor. Teach. Coll. Rec. 122, 1–36. doi: 10.1177/016146812012200502

Humphrey, R. H., Ashforth, B. E., and Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). The bright side of emotional labor. J. Organ. Behav. 36, 749–769. doi: 10.1002/job.2019

Jakubowski, T. D., and Sitko-Dominik, M. M. (2021). Teachers' mental health during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. PLoS ONE 16:e0257252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257252

Jones, A. L., and Kessler, M. A. (2020). Teachers' emotion and identity work during a pandemic. Front. Educ. 5:583775. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.583775

Jones, T. M., Diaz, A., Bruick, S., McCowan, K., Wong, D. W., Chatterji, A., et al. (2021). Experiences and perceptions of school staff regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and racial equity: the role of colorblindness. Sch. Psychol. 36, 546–554. doi: 10.1037/spq0000464

Kariou, A., Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., and Lainidi, O. (2021). Emotional labor and burnout among teachers: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:12760. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312760

Kelchtermans, G. (2005). Teachers' emotions in educational reforms: self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 995–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009

Kelchtermans, G. (2006). Teacher collaboration and collegiality as workplace conditions: a review. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 52, 220–237. doi: 10.25656/01:4454

Kim, L. E., and Asbury, K. (2020). “Like a rug had been pulled from under you”: the impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK Lockdown. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 1062–1083. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12381

Klapproth, F., Federkeil, L., Heinschke, F., and Jungmann, T. (2020). Teachers' experiences of stress and their coping strategies during COVID-19 induced distance teaching. J. Pedagogical Res. 4, 444–452. doi: 10.33902/JPR.2020062805

Kraft, M. A., Simon, N. S., and Lyon, M. A. (2020). “Sustaining a sense of success: the importance of teacher working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic,” in EdWorkingPaper No. 20-279 (Providence, RI: Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University).

Krifa, I., van Zyl, L. E., Braham, A., Ben Nasr, S., and Shankland, R. (2022). Mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: the role of optimism and emotional regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1413. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031413

Kush, J. M., Badillo-Goicoechea, E., Musci, R. J., and Stuart, E. A. (2022). Teachers' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Res. 51, 593–597. doi: 10.3102/0013189X221134281

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). I'm here for the hard re-set: post pandemic pedagogy to preserve our culture. Equity Excellence Educ. 54, 68–78. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2020.1863883

Lauriola, M., and Iani, L. (2015). Does positivity mediate the relation of extraversion and neuroticism with subjective happiness? PLoS ONE 10:e0121991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121991

LaVenia, K. N., Horner, C. G., and May, J. J. (2024). “Educational leadership as emotional labor: a framework for the values-driven emotion work of school leaders,” in Supporting Leaders for School Improvement through Self-care and Wellbeing, eds. B. W. Carpenter, J. Mahfouz, and K. Robinson (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 239–255.

Leo, A. (2022). High expectations, cautionary tales, and familial obligations: the multiple effects of family on the educational aspirations of first-generation immigrant and refugee youth. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 53, 27–46. doi: 10.1111/aeq.12407

Leo, A., Holdsworth, E. A., and Wilcox, K. C. (2023). The impact of job demand, control and support on New York state elementary teachers' stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education 3–13, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2023.2261476

Leo, A., Holdsworth, E. A., Wilcox, K. C., Khan, M. I., Ávila, J. A. M., and Tobin, J. (2022). Gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-method study of teacher stress and work-life balance. Community Work Fam. 25, 682–703. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2022.2124905