- Department of Educational Research, Lancaster University, Lancaster, England, United Kingdom

Introduction: Participatory evaluation has gained attention as a collaborative approach to institutional assessment, promoting shared decision-making and stakeholder engagement. However, its effectiveness within higher education, particularly in the Gulf region, remains underexplored. This study aims to examine how a participatory evaluation process influences institutional performance and stakeholder engagement in a higher education institute in the United Arab Emirates.

Methods: A qualitative case study approach was adopted, using document review, an evaluation scale, and semi-structured interviews with 17 stakeholders. This multi-method design enabled triangulation of institutional data and stakeholder perspectives, strengthening the credibility and depth of the findings. The approach was chosen to provide a comprehensive understanding of both measurable institutional changes and the experiences of those involved in the participatory evaluation process.

Results and discussion: The findings indicate strengthened quality assurance systems, enhancements in academic programs, and increased stakeholder engagement. Participants reported a greater sense of empowerment, improved collaboration, and capacity building, though stakeholder diversity was moderate and involvement of non-evaluators partial. Conceptually, the study situates participatory evaluation within institutional quality assurance frameworks, challenging traditional top-down models. Practically, it offers higher education institutions in similar contexts a structured approach to fostering inclusive decision-making and sustainable institutional self-improvement.

1 Introduction

The landscape of higher education is undergoing rapid transformation due to technological advancements, globalization, workforce shifts, and the growing emphasis on skills-based education (INQAAHE., 2022). These macro-level changes have significantly heightened stakeholder expectations regarding educational quality and student outcomes (Dunn et al., 2010). A pervasive challenge for the contemporary labor market, for instance, is the persistent misalignment between the expertise offered by educational institutions and industry demands (Ilyasov et al., 2023). Addressing these complex issues necessitates the implementation of robust quality assurance (QA) systems that effectively align institutional objectives with external expectations while fostering continuous and meaningful improvement. Consequently, higher education institutions must adeptly navigate these shifts, ensuring not only internal excellence but also accountability to external regulatory bodies and the public (Pham et al., 2022).

Despite the clear need for effective QA, traditional quality assurance systems often face significant challenges. Many institutions, for example, tend to prioritize compliance with external mandates over substantive internal enhancement (Huisman and Westerheijden, 2010), largely due to an overreliance on external quality assurance tools. Critically, external evaluations are frequently criticized for focusing on peripheral aspects rather than core student learning outcomes (Stensaker, 2018), with research indicating limited evidence of their direct impact on enhancing teaching effectiveness (Bloch et al., 2021). Furthermore, such systems can struggle to adapt to dynamic pedagogical and technological environments (Hopbach and Flierman, 2020). As a result, accountability-driven evaluations are often perceived as bureaucratic exercises detached from academic realities (Ryan, 2015), leading to faculty dissatisfaction with their level of engagement in quality processes. This pervasive disconnect raises fundamental concerns about whether quality assurance should primarily emphasize compliance or genuinely prioritize institutional growth and student learning (Ryan, 2015). Moreover, these accountability-driven models frequently overlook crucial stakeholder perspectives, marginalizing context-specific insights necessary for authentic enhancement (Burns et al., 2021). Therefore, a growing consensus, highlighted by Houston and Paewai (2013), suggests that effective quality assurance models must explicitly emphasize collaboration, stakeholder empowerment, and adaptability to institutional needs to genuinely foster institutional effectiveness. This recognition underscores the imperative for quality assurance models that actively engage faculty and staff in program improvement (Kis, 2005), advocating for integrated internal and external quality assurance, robust self-evaluation, and a commitment to continuous improvement.

In response to these identified limitations of traditional approaches, participatory evaluation emerges as a potentially transformative tool for driving self-improvement and fostering collaboration within quality assurance systems. As a subset of collaborative approaches to evaluation (CAE), participatory evaluation inherently involves evaluators working closely with non-evaluators to collectively generate insights (Cousins, 2019). This approach actively promotes broad stakeholder engagement in decision-making, planning, and implementation processes (Montano et al., 2023). Conceptually, it is defined as an applied social research method that purposefully integrates multiple perspectives (Cousins and Earl, 2004). Within higher education, participatory evaluation has been applied to assess program effectiveness, e-learning initiatives, curriculum development, and co-design initiatives (Bovill and Woolmer, 2020; Karaçoban and Karakuş, 2022), demonstrating its versatility. Its key features—shared control of the evaluation process, broad stakeholder involvement, and high engagement levels (King et al., 2007)—are precisely what address the shortcomings of compliance-focused models. By prioritizing collaboration and valuing diverse forms of knowledge, this approach not only enhances decision-making but also promotes social learning and builds institutional trust (Keseru et al., 2021).

Despite its clear potential, participatory evaluation still faces challenges in higher education, often being applied post-implementation with an overemphasis on quantitative outcomes (Knippschild and Vock, 2016). Critically, stakeholder engagement in institutional performance evaluation remains underexplored with limited methodological approaches in existing research (Burns et al., 2021). Large-scale institutional evaluations are rarely viewed as valuable learning opportunities (Hachmann, 2011), and existing studies predominantly apply participatory evaluation at the programmatic level, with few examining its role in broader institutional quality assurance. This research gap is particularly pronounced in the Gulf region, where top-down regulatory models dominate and tailored evaluative approaches for higher education remain scarce, underscoring the need for the present study.

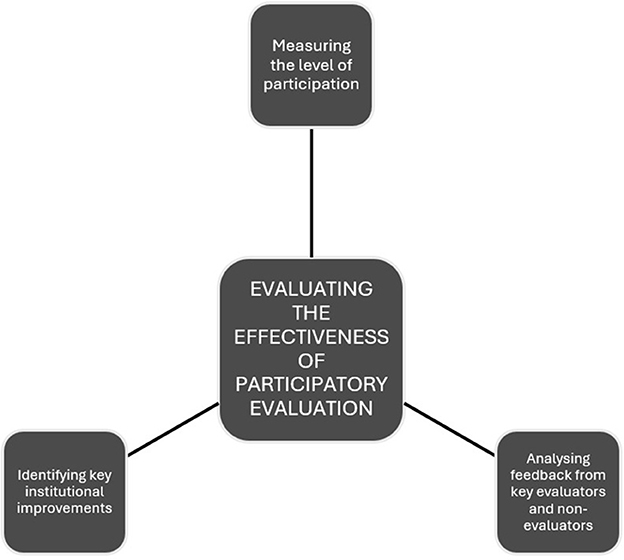

This study investigates the effectiveness of participatory evaluation as an institutional quality assurance tool within a higher education institution in the UAE. It introduces a three-fold model encompassing (1) the identification of institutional improvements resulting from participatory evaluation, (2) the measurement of stakeholder engagement, and (3) the analysis of participant feedback (Figure 1). Using an interpretivist/constructivist approach, this qualitative study employs institutional document analysis, (Daigneault and Jacob, 2009) participatory evaluation scale, and semi-structured interviews to assess the model's impact. This multi-method design enables triangulation of data sources, which helps to strengthen the credibility and depth of the findings. By combining institutional records, quantitative participation metrics, and qualitative narratives, the approach captures both measurable institutional changes and stakeholder perspectives, reflecting the multi-faceted nature of participatory evaluation in higher education. Such methodological pluralism is particularly important in contexts where diverse stakeholder experiences and institutional dynamics interact to shape outcomes.

To guide this investigation, the study addresses the following research questions:

• What key institutional improvements emerged from the participatory evaluation as demonstrated through external reports?

• To what extent was the evaluation participatory?

• What insights did evaluators, participants, and leadership gain from the participatory evaluation?

By conceptualizing participatory evaluation as a dynamic, iterative process rather than a static assessment tool, this study advances theoretical understandings of collaborative evaluation and institutional self-improvement. Practically, it positions participatory evaluation as a viable institutional-level quality assurance mechanism, bridging the gap between compliance and meaningful enhancement. In doing so, it offers empirical evidence for integrating participatory evaluation into higher education governance, particularly in regions where top-down models dominate. The study contributes to regional scholarship by providing a transferable framework for institutional assessment and quality enhancement in Gulf-based and similar educational contexts.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Context

This study examines a higher education institute in the United Arab Emirates that offers bachelor programs in maritime transport, marine engineering, and maritime logistics. The institute has 23 faculty members, 36 administrative staff, and 402 students. While some faculty hold terminal academic degrees, the majority are master mariners and chief engineers with extensive professional experience in the maritime sector.

The institute operates under multiple regulatory bodies: the Commission for Academic Accreditation (CAA) of the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure (responsible for maritime education and certification), and the National Qualifications Frameworks (as a recognized training provider).

To address outstanding compliance issues flagged by these regulators, the Chancellor implemented a system-wide action plan covering academic and administrative functions. However, after 6 months, many requirements remained unmet.

Reflecting on my role as a researcher, I observed that evaluation was often perceived as an intimidating accreditation exercise focused on non-compliance rather than improvement. To shift this perception and foster a more collaborative quality assurance culture, I adopted a participatory evaluation approach. This method aimed to engage stakeholders, co-create context-specific knowledge, and enhance institutional effectiveness through shared ownership and meaningful dialogue.

2.2 Research design

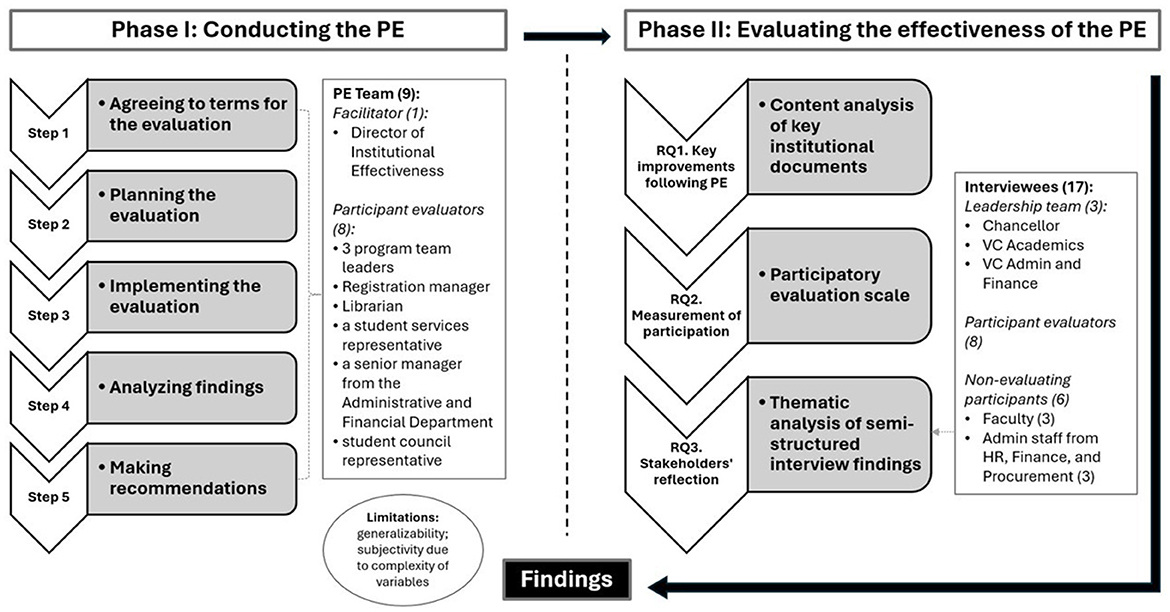

This was a non-experimental, descriptive qualitative study that was conducted over two phases: (I) conducting the participatory evaluation as described by Crishna (2007) and (II) evaluating the effectiveness of the evaluation through monitoring institutional improvements, measuring the level of participation, and capturing insight from multiple evaluating and non-evaluating stakeholders. Figure 2 presents the research design adopted in this study. It is noteworthy that the second phase began 8 months after completion of the participatory evaluation. This was to allow sufficient time for action plans to mature and key internal and external reviews to be completed before making judgments on the level of effectiveness of the evaluation.

2.3 The types of data collected and analyzed

Data was collected using document review, a participatory evaluation scale, and semi-structured interviews. Triangulation, a core methodological strategy in qualitative research, was purposefully employed in this study to enhance the credibility, confirmability, and depth of our findings. This involved primarily using methodological triangulation by combining diverse data collection methods (document review, an evaluation scale, and semi-structured interviews) and data source triangulation by gathering perspectives from various stakeholders and institutional records. This multi-method approach was particularly appropriate for examining the multifaceted influence of participatory evaluation, which entailed understanding both its tangible impacts on institutional performance (e.g., changes in quality assurance systems, academic programs) and the subjective experiences and perceptions of stakeholders (e.g., empowerment, collaboration).

In general, the study utilized an inductive approach to coding and analysis, in which the researcher attempts to make meaning of the data without the influence of preconceived notions, allowing the data to speak for themselves through a bottom-up analytical approach (Wyse et al., 2017). As highlighted by Hillebrand and Berg (2000), inductive coding works well with single cases or when one wants to explore a phenomenon.

An inductive conventional content analysis was conducted for coding and analysis of key internal documents and external reports prior to and following the participatory evaluation to identify the main areas of improvement that took place after completion of the self-assessment and action plans developed by the stakeholders (RQ.1). Using a specialized Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis software, the process included data collection, developing an e-codebook, determining coding rules, iteration on the coding rules, data analysis, and interpretation of the results.

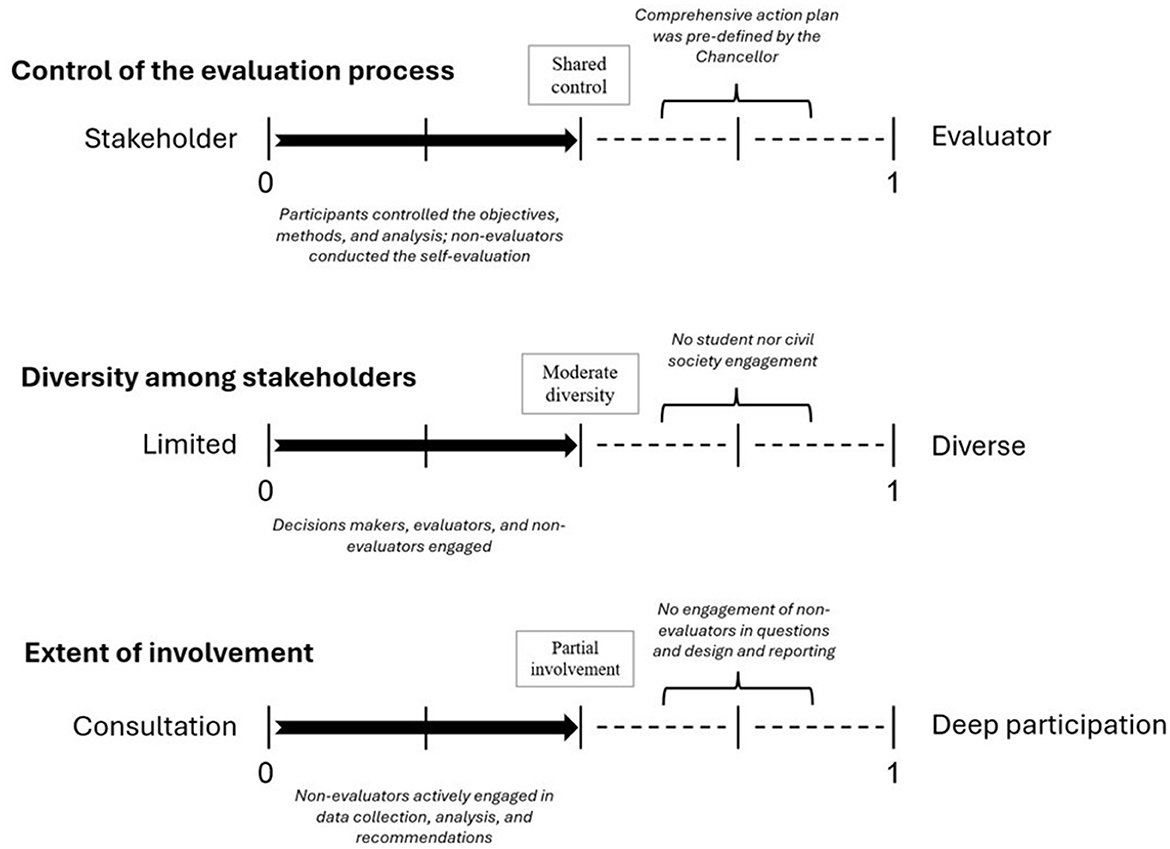

The second research question was addressed using an evaluation scale developed by Daigneault and Jacob (2009), where the participatory index is based on three main items: (a) control of the evaluation process, (b) diversity of stakeholders, and (c) extent of involvement. In their study, Daigneault and Jacob (2009) aimed to clarify the conceptual ambiguity surrounding participatory evaluation. They conducted a systematic analysis of the concept and subsequently developed a scale that enables evaluators to measure the extent to which an evaluation incorporates participatory elements. Connors and Magilvy (2011) proposed that the scale would be beneficial for assessment researchers in empirical studies and for practitioners as a means of self-reflection.

When applying the measurement index, an evaluation must be scored at the minimal level (at least 0.25) on all three dimensions to be considered “participatory,“ as all are necessary components. An overall participation score is also determined based on the interaction of the ratings of the three dimensions; a lower score on any one dimension limits the degree to which the evaluation is rated as participatory. A score of 1.00 on all dimensions would indicate the ideal of participatory evaluation.

Lasty, thematic analysis was used to sort and categorize data to make meaning of the participants responses during the interviews (RQ3). Following a process of transcription and familiarization, sub-codes were identified and grouped together using a codebook to form codes, which, ultimately, were used to identify patterns in the data that will be presented as themes. Classical analysis as described by Leech and Onwuegbuzie (2007) was used where I counted how often a code was used to assist in determining which codes are most important. Finally, I moved from a semantic analysis (description of data) to a latent level analysis where data were interpreted to facilitate answering the research questions.

2.4 The sample selected

Upon completion of the participatory evaluation, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposively selected sample including the senior leadership team (Chancellor, the Vice Chancellor of Academic Affairs, and Vice Chancellor of Administration and Finance), the evaluation team (three program team leaders, the registrar, the librarian, a student services representative, and a senior manager from the Administrative and Financial Department), and the participants (3 faculty members from each program, three staff representing the Human Resources, Finance, and Facilities Management Departments).

A total of 17 interviews were conducted with 65% male and 35% female interviewees. The evaluation team comprised 47% of the interviewees, with the leadership team and the non-evaluating participants forming 18% and 35% of the total interviewees, respectively.

3 Results

This section is divided into two parts: phase (I) a description of the participatory evaluation conducted, and phase (II) examining the key improvements (research question 1), extent of participation (research question 2), and main lessons learned from the participatory evaluation (research question 3).

3.1 Phase I: description of the evaluation conducted

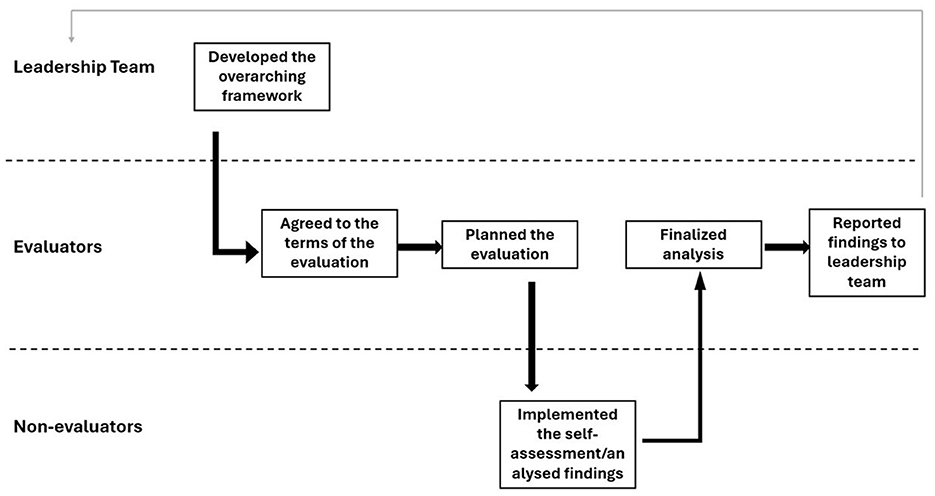

This study's first phase involved implementing a participatory evaluation following the framework described by Crishna (2007). The process included agreeing on evaluation terms, planning, implementation, analysis, and recommendations. Figure 3 summarizes the steps taken per stakeholder.

3.1.1 Agreeing on evaluation terms

To ensure conceptual sampling, an evaluation team was formed, including three program leaders, the registrar, the librarian, a student services representative, a senior administrator from the Administrative and Financial Department, and a student council representative (one facilitator and eight participant evaluators).

Following the Chancellor's approval, an initial meeting was held to formalize the team, outline objectives, and establish deliverables and timelines. The team collectively agreed that an external evaluation alone would not provide a comprehensive view and opted for a self-evaluation approach, enabling stakeholders to reflect on action plan progress and challenges.

3.1.2 Planning the evaluation

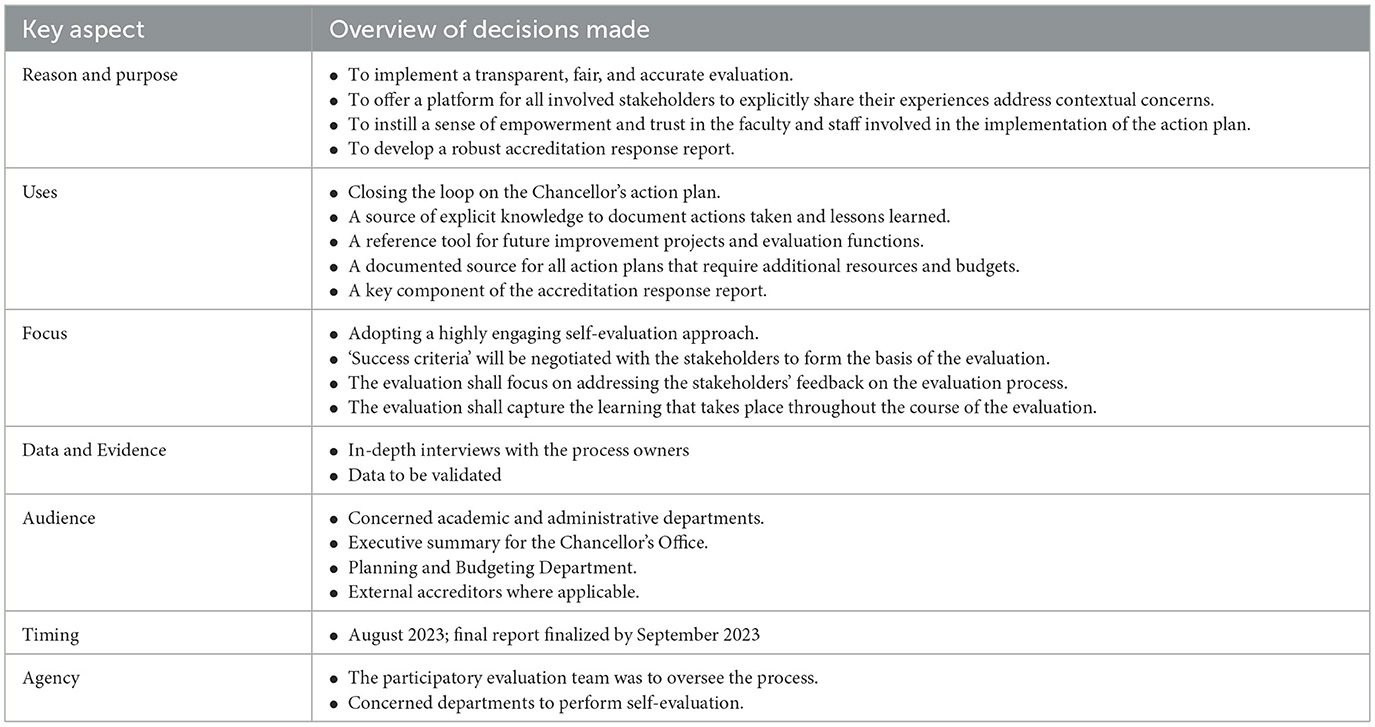

The next meeting focused on structuring the evaluation, identifying data needs, stakeholders to engage, logistical arrangements, reporting templates, and how findings would be utilized.

To guide the process, the RUFDATA model (Saunders, 2000) was introduced, facilitating structured decision-making for evaluation design. Table 1 outlines the team's key discussions and decisions based on RUFDATA's seven components.

3.1.3 Implementing the evaluation

The team split into pairs to conduct semi-structured face-to-face interviews with department heads and staff. These interviews enabled stakeholders to self-assess their performance, identify facilitating and hindering factors, and suggest improvements for future challenges.

Each group assigned a third participant to review findings before analysis, enhancing reliability. Draft departmental reports, supported by institutional documents, were compiled and validated by the facilitator.

3.1.4 Analyzing findings

Small groups analyzed the draft reports and supporting documents, identifying emerging themes and concepts. Key findings were then presented to the full evaluation team for validation. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Triangulation was applied where possible by comparing data from multiple institutional roles.

3.1.5 Making recommendations

The final step involved sharing findings with study participants for validation, ensuring the action plan aligned with stakeholder perspectives, timelines, and institutional priorities. A final report was produced and disseminated to the leadership team and all participants.

3.2 Phase II: exploring the key improvements, level of participation, and main lessons learned from conducting the participatory evaluation

3.2.1 Key improvements that took place following implementing the improvement plan

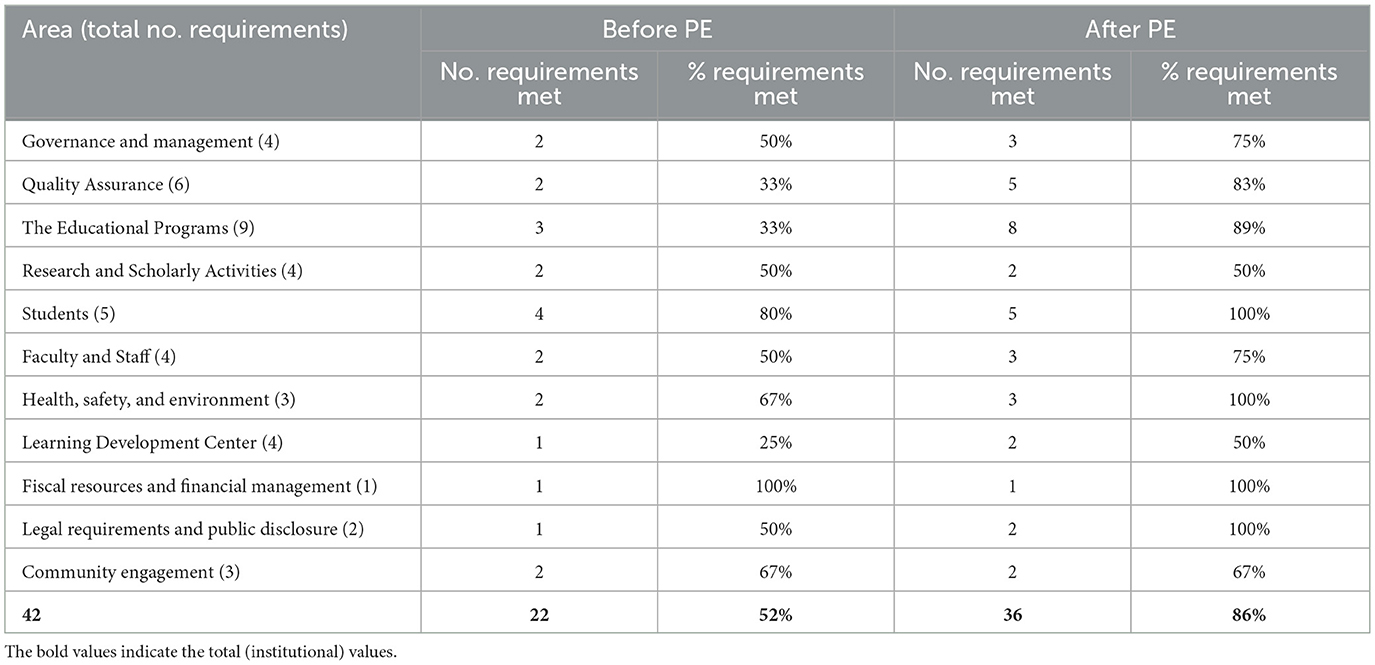

The participatory evaluation led to significant institutional improvements, as evidenced by internal and external reports comparing compliance levels before and after the evaluation. Quality assurance demonstrated a 50% increase in compliance, reflecting strengthened institutional commitment to academic standards. Similarly, educational programs showed notable progress, reaching an 89% compliance rate post-evaluation. The domain of health, safety, and the environment also improved substantially, achieving full compliance and increasing the number of requirements met from two to three. Legal requirements and public disclosure exhibited similar progress, attaining full compliance after the evaluation. Governance and management demonstrated a 25% increase in compliance, indicating a positive shift toward more effective leadership and governance practices. The most significant improvement was observed in the student-focused category, where compliance reached 100%, highlighting the institution's strengthened commitment to enhancing the student experience.

In contrast, some areas did not demonstrate as clear or substantial improvement. Research and scholarly activities remained stable, with compliance levels unchanged at 50%, indicating no significant progress in this area. Community engagement also showed no notable change, maintaining a compliance level of 67%. While the Learning Development Center experienced a 25% increase in compliance following the evaluation, further development is needed to fully meet institutional requirements. Fiscal resources and financial management remained at full compliance both before and after the participatory evaluation. Table 2 provides a detailed summary of these findings.

3.2.2 The level of participation as measured by the participatory evaluation index

This study applied the participatory scale developed by Daigneault and Jacob (2009) before and after conducting the participatory evaluation. While the Chancellor's improvement action plan was not inherently participatory, the values derived from its development and dissemination served as a baseline for assessing changes after the participatory evaluation.

The first dimension assessed was control of the evaluation process. This required that non-evaluators not only be involved but also have the authority to formally or informally influence the evaluation. Control was measured throughout the entire evaluation process. Initially, the evaluation process was exclusively controlled by the evaluator, with a baseline rating of 0.00. Following the participatory evaluation, control increased to a shared arrangement between participants, evaluators, and non-participating sponsors, resulting in a score of 0.50. This improvement stemmed from the participants' involvement in defining the evaluation objectives, selecting data collection methods, and analyzing results. However, they did not have significant influence over the original mandate and criteria outlined in the Chancellor's earlier report. Additionally, the self-evaluation approach ensured active participation, as non-evaluators identified performance criteria for each theme and provided key documents as supporting evidence.

The second dimension, diversity of stakeholders, considered the extent to which different groups were involved in the evaluation process. The scale identifies four categories of non-evaluators: policymakers and decision-makers, implementers and deliverers, target populations and beneficiaries, and civil society representatives. Each group's involvement contributes 0.25 to the total score. Prior to the participatory evaluation, only the Chancellor, a policymaker, was engaged in the action plan's development, resulting in a baseline score of 0.00. The participatory evaluation broadened decision-maker involvement by including vice chancellors, program chairs, and heads of departments, as well as implementers such as faculty and administrative representatives. However, the process did not include beneficiaries, as the invited student representative did not participate, nor did it involve civil society representatives. This resulted in a post-evaluation score of 0.50, indicating moderate diversity.

The third dimension, extent of involvement, measured the degree to which non-evaluators participated in four key technical tasks: defining evaluation questions and design, data collection and analysis, making judgments and recommendations, and reporting and dissemination. The evaluation team collaborated to establish evaluation questions and design, and non-evaluators actively participated in data collection and analysis by reviewing institutional documents. They also contributed to the judgment and recommendations phase through self-evaluation, identifying key areas for improvement and enhancement. However, the reporting and dissemination phase was managed by the evaluation team, with non-evaluators not directly involved in formalizing the final report. As a result, non-evaluators were engaged in two out of four technical tasks, yielding a score of 0.50 for this dimension.

Collectively, all aspects of the evaluation index exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.25 required for an evaluation to be considered participatory. The overall participatory evaluation score, derived from summing the three dimensions, was 1.5 out of a possible 3, indicating an average level of participation. Figure 4 presents a summary of the evaluation index findings and the rationale behind the assigned scores.

3.2.3 The key lessons learned from the participatory evaluation exercise

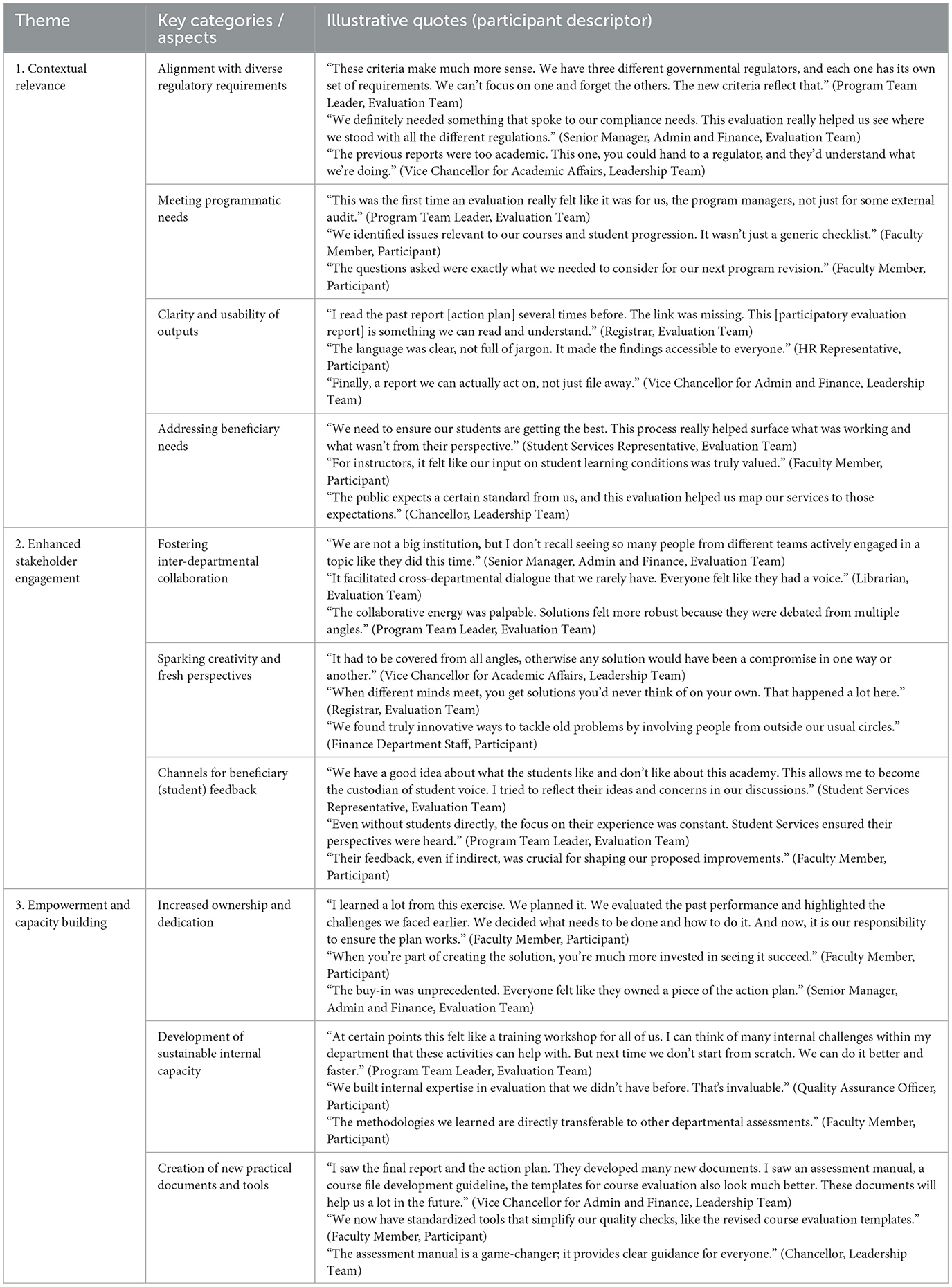

Thematic analysis of the semi-structured interview data revealed three overarching themes reflecting participants' experiences and perceptions of the participatory evaluation process: contextual relevance, enhanced stakeholder engagement, and empowerment and capacity building. Table 3 provides a comprehensive summary of these themes, along with key categories and illustrative quotes from various participants, offering a transparent overview of how these findings emerged from the data. The subsequent narrative elaborates on each theme, providing a deeper understanding of its nuances and implications.

The first predominant theme highlighted by interviewees was the relevance of the participatory evaluation to the institutional context. Participants consistently emphasized that the evaluation's design, questions, and outcomes were perceived as deeply aligned with the specific needs and operational realities of the higher education institute, moving beyond generic assessment frameworks. This relevance was multifaceted, encompassing alignment with diverse external regulatory requirements and meeting the granular needs of internal programmatic managers.

Several interviewees articulated how the participatory approach ensured the evaluation criteria were not only comprehensive but also practical for navigating the complex regulatory landscape of the region. As one Program Team Leader succinctly put it:

These criteria make much more sense. We have three different governmental regulators, and each one has its own set of requirements. We can's focus on one and forget the others. The new criteria reflect that.

This sentiment was echoed by the Senior Manager, Admin and Finance, Evaluation Team, who noted:

We definitely needed something that spoke to our compliance needs. This evaluation really helped us see where we stood with all the different regulations

This underscored the direct applicability of the evaluation's outputs to external accountability. Beyond compliance, the evaluation was also praised for its utility at the program level. A Program Team Leader remarked:

This was the first time an evaluation really felt like it was for us, the program managers, not just for some external audit

The resulting evaluation reports and action plans were consistently lauded for their clarity and usability. The Registrar confirmed this, stating:

I read the past report [action plan] several times before. The link was missing. This [participatory evaluation report] is something we can read and understand.

This improved comprehensibility ensured that the findings were accessible and actionable for a wide range of stakeholders, fostering a sense of ownership over the outcomes. Finally, the evaluation's relevance extended to addressing the needs of key beneficiaries. While direct student representation was not feasible, the presence of a Student Services representative ensured that insights into student and instructor experiences were integrated, directly impacting the perceived value and comprehensiveness of the evaluation.

The second significant theme that emerged from the interviews was the marked improvement in stakeholder engagement throughout the evaluation process. Participants consistently highlighted how the participatory approach fostered a collaborative environment that transcended traditional departmental silos, sparking creativity and encouraging the exchange of diverse perspectives.

Interviewees requently pointed to the unprecedented level of inter-departmental collaboration. A Senior Senior Manager, Admin and Finance observed:

We are not a big institution, but I don't recall seeing so many people from different teams actively engaged in a topic like they did this time.

This indicated a departure from typical operational patterns, fostering a more unified and inclusive approach to problem-solving. This collaboration was not merely about presence but about genuine interaction and the sharing of insights. The Registrar highlighted the generative nature of this engagement:

When different minds meet, you get solutions you'd never think of on your own. That happened a lot here.

This dynamic exchange of ideas was seen as crucial for developing comprehensive and robust solutions, ensuring that issues were ”covered from all angles“ (Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs). While the initial plan to include a student representative did not materialize, the engagement mechanisms still ensured student voices were heard. A Student Services Representative played a pivotal role in this, articulating:

We have a good idea about what the student like and don't like about this academy. This allows me to become the custodian of student voice. I tried to reflect their ideas and concerns in our discussions.

This underscores how the participatory framework created channels, even indirect ones, for beneficiary feedback, reinforcing the comprehensive nature of the engagement.

The third and equally impactful theme identified by interviewees was the profound sense of empowerment and tangible capacity building experienced by participants. The direct involvement of stakeholders in determining the direction, execution, and interpretation of the evaluation fostered a strong sense of ownership and equipped them with new skills and tools for future self-improvement initiatives.

Participants described a clear progression from mere involvement to genuine ownership of the evaluation outcomes. A Faculty Member eloquently captured this sentiment:

I learned a lot from this exercise. We planned it. We evaluated the past performance and highlighted the challenges we faced earlier. We decided what needs to be done and how to do it. And now, it is our responsibility to ensure the plan works.

This sense of shared responsibility and dedication was a powerful driver for commitment to implementing the resulting action plan. Beyond ownership, the process served as a significant learning experience, effectively building internal capacity within the institution. A Program Team Leader described it as feeling “like a training workshop for all of us,” emphasizing the practical skills gained. They added, “I can think of many internal challenges within my department that these activities can help with. But next time we don't start from scratch. We can do it better and faster,” highlighting the transferability and sustainability of the newly acquired knowledge and processes. Furthermore, the participatory evaluation led to the creation of concrete, practical documents and tools that would serve the institution long after the evaluation concluded. The Vice Chancellor for Admin and Finance, proudly stated:

I saw the final report and the action plan. They developed many new documents. I saw an assessment manual, a course file development guideline, the templates for course evaluation also look much better. These documents will help us a lot in the future.

These tangible outputs are clear evidence of the enhanced internal capacity and the lasting legacy of the participatory approach.

4 Discussion

The current study aimed to examine how a participatory evaluation process influences institutional performance and stakeholder engagement within a higher education institute in the United Arab Emirates. The findings, derived from a robust multi-method approach including compliance data, a participatory evaluation index, and qualitative interviews, reveal a nuanced picture of the impacts and dynamics of this approach.

4.1 Connecting institutional improvements with participatory dynamics

The study demonstrates significant improvements in key institutional performance areas following the participatory evaluation, particularly in quality assurance, educational programs, and student-focused categories, with compliance rates increasing substantially, even reaching 100% in student-focused areas. This tangible progress underscores the pragmatic efficacy of participatory evaluation in leveraging evaluative evidence for practical problem-solving, as posited by Cousins (2019). The direct involvement of diverse stakeholders facilitated a collective learning process, enabling a hands-on understanding and modification of academic and administrative functions. The enhanced clarity and usability of the evaluation outputs, a key aspect highlighted in the qualitative data (Contextual Relevance theme), likely contributed to the effective implementation of the improvement plan and thus, the observed compliance gains. This suggests a direct link where the perceived value and accessibility of the evaluation's outputs, driven by participatory design, enabled more effective organizational action.

However, areas such as research and scholarly activities, and community engagement, did not exhibit similar improvements. This discrepancy in outcomes can be attributed to the specific focus and scope of the participatory evaluation, which was more acutely aligned with immediate institutional needs in quality assurance and academic programs. The qualitative data on ”Contextual Relevance“ further supports this, indicating that the evaluation's design was purposefully tailored to address the most pressing, localized concerns, which might have naturally de-emphasized broader, more complex areas that require different long-term strategies beyond the scope of this particular evaluation cycle.

4.2 The transformative power of stakeholder engagement and empowerment

Beyond measurable compliance, the study revealed a profound transformative shift in the institutional culture from hierarchical to inclusive and collaborative, representing perhaps the most significant achievement. Historically characterized by autocratic evaluations dominated by external bodies, the adoption of participatory evaluation democratized the process, fostering greater stakeholder involvement and a crucial shift in power dynamics. This aligns with the qualitative theme of “Enhanced Stakeholder Engagement,” where participants reported unprecedented inter-departmental collaboration and the sparking of creativity through diverse perspectives. The “Empowerment and Capacity Building” theme further illuminates this, as stakeholders reported increased ownership and dedication, coupled with the development of sustainable internal capacity through new skills and practical tools (e.g., assessment manuals, course file guidelines).

This cultural transformation was demonstrably facilitated by senior management's creation of a permissive environment, allowing frontline staff to innovate and learn, consistent with (Ogunlayi and Britton, 2017) emphasis on supportive leadership for continuous improvement. The self-evaluation process, significantly influenced by non-evaluators (as reflected in the moderate “Control of the Evaluation Process” score of 0.50 on the participatory index), reinforced this inclusive culture, cultivating shared responsibility and enhancing collective problem-solving capabilities. The triangulation of data here is particularly powerful: the qualitative narratives explain the drivers of the observed cultural shift, while the participatory index quantifies the extent to which control was shared and diversity was achieved, providing a concrete measure of the engagement discussed qualitatively. The moderate score on the index, despite strong qualitative reports of empowerment, suggests that even partial shifts in control and diversity can yield substantial perceived benefits and cultural change.

4.3 Navigating participation levels, ethical complexities, and future sustainability

While the participatory evaluation achieved an overall score of 1.5 out of a possible 3 on the Daigneault and Jacob (2009) participatory scale, indicating an average level of participation, this score provides valuable insights into areas for refinement. Specifically, the moderate scores (0.50 each) for “Control of the Evaluation Process,” “Diversity of Stakeholders,” and “Extent of Involvement” highlight both successes and limitations. Participants gained significant influence over objectives and methods, but not the original mandate, which prevented a higher control score. Similarly, while decision-makers and implementers were well-represented, the absence of direct student participation (a crucial beneficiary group) and civil society representatives limited the diversity score. This qualitative insight, emerging from the “Enhanced Stakeholder Engagement” theme, corroborates the quantitative limitation in the diversity index. Furthermore, while stakeholders were actively involved in defining questions, data collection, and recommendations, their non-involvement in formal reporting and dissemination explains the moderate score for “Extent of Involvement.”

These dynamics underscore that adopting a participatory approach inevitably raises new ethical considerations, particularly concerning power dynamics. As Bussu et al. (2020) note, such approaches necessitate a re-evaluation of traditional ethical principles like anonymity and consent. Ensuring that all participants feel respected and valued within the shared control framework remains a critical challenge, requiring careful navigation.

Looking forward, a key challenge for senior managers is sustaining this cultural shift and embedding a continuous learning culture. The principles of participatory design, emphasizing shared power and incorporating input from those affected (Cossham and Irvine, 2021), are critical for long-term transformation. The insights gained from the qualitative themes, particularly the desire for continued “Capacity Building,” reinforce the need for ongoing professional development and institutional support to empower evaluators and embed these practices.

4.4 Balancing internal and external imperatives

The findings also highlight the imperative of balancing internal and external evaluation systems. The study's ability to measure key achievements through the improvement plan relied on observing the findings of external accreditation reports, demonstrating how internal participatory evaluations (which provide rich, context-specific insights and foster a learning culture) can be effectively complemented by external evaluations to add credibility and accountability (Morra et al., 2009). This integrated approach provides a robust quality assurance framework that both enhances institutional performance and builds a more engaged and empowered community. The qualitative emphasis on “Contextual Relevance” — meeting diverse regulatory requirements — directly feeds into this balance, suggesting that the internal participatory process made external compliance more achievable and understandable.

The absence of direct student involvement, noted in the participatory index and subtly within the qualitative feedback, represents a crucial area for future development. Strategies to raise awareness and actively incorporate student voices are vital not only for providing valuable insights but also for fostering their ownership and commitment, aligning with the broader goals of a participatory culture.

In conclusion, this study confirms that participatory evaluation offers a powerful mechanism for driving institutional improvement in higher education. Its strength lies in its ability to foster relevant, engaged, and empowering processes that lead to tangible outcomes and cultural transformation. The triangulation of quantitative performance data, participatory index scores, and rich qualitative narratives provides a robust evidence base, demonstrating how the process of participation (quantified by the index and explained by qualitative themes) directly contributes to both the outcomes of improvement and the cultural shifts within the institution.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

This study provides compelling evidence of the transformative impact of a participatory evaluation process within a higher education institution in the United Arab Emirates. By integrating quantitative analysis of compliance improvements with a participatory index and rich qualitative insights from stakeholders, the research demonstrates that such an approach not only drives tangible enhancements in institutional performance across key areas like quality assurance, academic programs, and student-focused initiatives, but also profoundly influences organizational culture.

The findings underscore the pragmatic utility of participatory evaluation in fostering contextual relevance and facilitating the effective application of evaluative evidence for problem-solving. More significantly, the study highlights a crucial shift from a hierarchical to a more inclusive and collaborative institutional culture, characterized by enhanced stakeholder engagement, increased ownership, and substantial capacity building among participants. This cultural transformation, supported by enabling leadership, emerged as a potent driver for continuous improvement. While the participatory index indicated an average level of participation, the qualitative data elucidated the depth of the experienced empowerment and the specific mechanisms through which partial involvement yielded significant benefits, thereby showcasing the strength of methodological triangulation.

In sum, this study contributes to the literature by empirically demonstrating how participatory evaluation can challenge traditional top-down quality assurance models, offering a robust framework for fostering inclusive decision-making and sustainable self-improvement in higher education, particularly within under-researched contexts like the Gulf region.

To conclude, it is crucial for institutions to prioritize collaborative evaluations as a strategic necessity in order to not only comply with external regulations but also foster internal cultures of ongoing enhancement. Organizations may effectively navigate the complicated evaluation functions by incorporating the input and viewpoints of stakeholders, demonstrating agility, adaptability, and a dedication to continuous improvement.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Lancaster University Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AE: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Open access funding provided by Lancaster University.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bloch, C., Degn, L., Nygaard, S., and Haase, S. (2021). Does quality work work? A systematic review of academic literature on quality initiatives in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 46, 701–718. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1813250

Bovill, C., and Woolmer, C. (2020). Student Engagement in Evaluation. London: Routledge eBooks, 83–96. doi: 10.4324/9780429023033-7

Burns, D., Howard, J., and Ospina, S. (2021). The SAGE Handbook of Participatory Research and Inquiry. London: In SAGE Publications Ltd eBooks. doi: 10.4135/9781529769432

Bussu, S., Lalani, M., Pattison, S., and Marshall, M. (2020). Engaging with care: ethical issues in participatory research. Qual. Res. 21, 667–685. doi: 10.1177/1468794120904883

Connors, S. C., and Magilvy, J. K. (2011). Assessing vital signs: applying two participatory evaluation frameworks to the evaluation of a college of nursing. Eval. Program Plann. 34, 79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2010.12.001

Cossham, A., and Irvine, J. (2021). Participatory design, co-production, and curriculum renewal. J. Educ. Libr. Inf. Sci. 62, 383–402. doi: 10.3138/jelis-62-4-2020-0089

Cousins, J. B. (2019). Collaborative Approaches to Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Incorporated. doi: 10.4135/9781544344669

Cousins, J. B., and Earl, L. M. (2004). The Case for Participatory Evaluation: Theory, Research, Practice. In Routledge eBooks, 15–32. doi: 10.4324/9780203695104-9

Crishna, B. (2007). Participatory evaluation (II) – translating concepts of reliability and validity in fieldwork. Child Care Health Dev. 33, 224–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00658.x

Daigneault, P. M., and Jacob, S. (2009). Toward accurate measurement of participation. Am. J. Eval. 30, 330–348. doi: 10.1177/1098214009340580

Dunn, D. S., McCarthy, M. A., Baker, S. C., and Halonen, J. S. (2010). Using Quality Benchmarks for Assessing and Developing Undergraduate Programs. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Hachmann, V. (2011). From mutual learning to joint working: europeanization processes in the interreg b programmes. European Planning Studies 19, 1537–1555. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2011.594667

Hillebrand, J. D., and Berg, B. L. (2000). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Teach. Sociol. 28:87. doi: 10.2307/1319429

Hopbach, A., and Flierman, A. (2020). “Higher education: a rapidly changing world and a next step for the standards and guidelines for quality assurance in the european higher education area,” in Advancing Quality in Higher Education: Celebrating 20 Years of ENQA (ENQA: Yerevan), 29–36.

Houston, D., and Paewai, S. (2013). Knowledge, power and meanings shaping quality assurance in higher education: a systemic critique. Qual. High. Educ. 19, 261–282. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2013.849786

Huisman, J., and Westerheijden, D. F. (2010). Bologna and quality assurance: progress made or pulling the wrong cart? Qual. High. Educ. 16, 63–66. doi: 10.1080/13538321003679531

Ilyasov, A., Imanova, S., Mushtagov, A., and Sadigova, Z. (2023). Modernization of quality assurance system in higher education of Azerbaijan. Qual. High. Educ. 29, 23–41. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2022.2100606

INQAAHE. (2022). International Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Tertiary Education. Available online at: https://www.inqaahe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/INQAAHE-International-Standards-and-Guidelines-ISG.pdf#:~:text=The%20INQAAHE%20International%20Standards%20and%20Guidelines%20of%20Quality,providers%20and%20their%20external%20quality%20assurance%20bodies%20globally (Accessed March 5, 2025).

Karaçoban, F., and Karakuş, M. (2022). Evaluation of the curriculum of the teaching in the multigrade classrooms course: Participatory evaluation approach. Pegem J. Educ. Instr. 12, 84–99. doi: 10.47750/pegegog.12.01.09

Keseru, I., Coosemans, T., and Macharis, C. (2021). Stakeholders' preferences for the future of transport in Europe: participatory evaluation of scenarios combining scenario planning and the multi-actor multi-criteria analysis. Futures 127:102690. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2020.102690

King, J. A., Cousins, J. B., and Whitmore, E. (2007). Making sense of participatory evaluation: framing participatory evaluation. New Dir. Eval. 2007, 83–105. doi: 10.1002/ev.226

Kis, V. (2005). Quality assurance in tertiary education: current practices in OECD countries and a literature review on potential effects. Tertiary Rev. 14, 1–47.

Knippschild, R., and Vock, A. (2016). The conformance and performance principles in territorial cooperation: a critical reflection on the evaluation of INTERREG projects. Reg. Stud. 51, 1735–1745. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1255323

Leech, N. L., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: a call for data analysis triangulation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 22, 557–584. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

Montano, L. J., Font, X., Elsenbroich, C., and Ribeiro, M. A. (2023). Co-learning through participatory evaluation: an example using theory of change in a large-scale EU-funded tourism intervention. J. Sustain. Tour. 33, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2023.2227781

Morra, I, Linda, G, and Rist, R. C. (2009). The Road to Results. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-7891-5

Ogunlayi, F., and Britton, P. (2017). Achieving a ‘top-down' change agenda by driving and supporting a collaborative ‘bottom-up' process: case study of a large-scale enhanced recovery programme. BMJ Open Quality 6:e000008. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000008

Pham, N. T. T., Nguyen, C. H., Pham, H. T., and Ta, H. T. T. (2022). Internal quality assurance of academic programs: a case study in Vietnamese higher education. SAGE Open 12:215824402211444. doi: 10.1177/21582440221144419

Ryan, T. (2015). Quality assurance in higher education: a review of literature. High. Learn. Res. Commun. 5:n4. doi: 10.18870/hlrc.v5i4.257

Saunders, M. (2000). Beginning an evaluation with RUFDATA: theorizing a practical approach to evaluation planning. Evaluation 6, 7–21. doi: 10.1177/13563890022209082

Stensaker, B. (2018). Quality assurance and the battle for legitimacy – discourses, disputes and dependencies. High. Educ. Eval. Dev. 12, 54–62. doi: 10.1108/HEED-10-2018-0024

Keywords: participatory evaluation, institutional performance, higher education, stakeholder engagement, quality assurance, case study

Citation: Elhakim A (2025) The effectiveness of using participatory evaluation in enhancing institutional performance: a case study from the United Arab Emirates. Front. Educ. 10:1596743. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1596743

Received: 20 March 2025; Accepted: 08 September 2025;

Published: 29 September 2025.

Edited by:

Mona Hmoud AlSheikh, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Angélica Monteiro, University of Porto, PortugalMercedes Gaitan-Angulo, Konrad Lorenz University Foundation, Colombia

Copyright © 2025 Elhakim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ahmed Elhakim, YWxoYWtpbV9hQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Ahmed Elhakim

Ahmed Elhakim