- Department of Curriculum Studies and Higher Education, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

Introduction: Although literature shows that libraries can play a significant role in student learning, very little is known about how the availability of libraries can transform rural education ecosystems. This study, therefore, positions libraries as innovative hubs for improving how teachers teach and students learn in rural schools, often incapacitated by resource scarcity in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

Methods: Deploying the theoretical lens of Todd and Kuhlthau's Model of the School Library as a Dynamic Agent of Learning, this qualitative study explores the potential of school libraries as innovative pedagogical hubs to improve teaching and learning in rural schools. The study adopts a multiple case study design by purposively selecting six schools as research sites in a rural school district of the Eastern Cape in South Africa. Using a sample of 12 teachers, data were collected through semi-structured interviews and processed using content and thematic analyses.

Results: The findings indicate that school libraries can improve teachers' lesson preparation and learner engagement by encouraging learner-centered environments and curriculum differentiation. Libraries also help mitigate resource inadequacies, enhancing teachers' subject knowledge and pedagogy. By establishing and maintaining functional school libraries as innovative pedagogical hubs, instead of mere repositories of information, school libraries can enhance the quality of teaching and learning in rural schools.

Discussion: The other quintessential findings of this study were that libraries catalyzed learners' self-directed learning and the quest to find more information on the concepts they were learning. This nurtured their critical thinking, creativity, and research skills. The study advocates the development of curriculum policy guidelines that prioritize the availability of school libraries to promote quality teaching and learning in rural education ecosystems.

1 Introduction

For decades, numerous organizations have advocated for education for all, irrespective of social class, gender, and other discriminatory attributes. For instance, the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal Number 4 calls for all citizens of the world to have access to opportunities for quality education (Dei and Asante, 2022). A study conducted in South Australia by Dix et al. (2020) established that schools with a qualified teacher librarian are more likely to have improved student literacy outcomes, thereby improving the quality of education for both urban and rural schools. In a similar study conducted in 10 New Jersey public schools in the USA, Todd (2021, p. 1) concluded that school libraries “are the multiple faces of the future global citizens that we nurture in our schools” to ensure the provision of quality education. Agenda 2063, The Africa We Want, also advocates for access and improvement of education in the African context (African Union Commission, 2016). South Africa's National Development Plan Centers its vision on quality education to promote social justice (National Planning Commission, 2013). Teachers are viewed as the key role players and drivers in the provision of quality education. There is consensus in literature that the holistic development of learners is dependent on teachers as cornerstones of innovation that promote quality teaching and learning (Grigoropoulos and Gialamas, 2018; Mojapelo, 2016; Mahwasane, 2022). Teachers' pedagogical practices are vital in realizing quality and efficiency in teaching-learning spaces (Sefoka, 2021). The dynamism in global knowledge production and development suggests that teachers must be able to face continual challenges within the teaching and learning environment if they are to meet learners' continuously evolving needs (Grigoropoulos and Gialamas, 2018). However, the role of school libraries as innovative teaching-learning hubs in a dynamic and highly digitalized 21st century has often been overlooked, if not ignored.

Libraries are spaces where young people gather the knowledge, skills, and practices required to nurture them into informed, knowledgeable, and reflective individuals in a digitally connected global society (Todd, 2021). The school library is, therefore, a safe place in which to discover information, question the world of ideas, explore conflicting perspectives, and make planned and accidental discoveries. Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) seminal study established that school libraries provide significant opportunities for students to learn and grow. Based on their research findings, Todd and Kuhlthau (2005, p. 87) concluded that: “When effective school libraries are in place, students do learn: 13,000 students cannot be wrong.”

The findings from Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) large-scale study indicate that students enjoyed the instructional assistance provided by a library and its potential to develop in-depth exploration and research skills and that this instruction positively impacted their performance. Dix et al. (2020) concur those libraries that are functional and effective play the role of instructional agents that allow students to be engaged actively and meaningfully in information-finding efforts. Mahwasane (2022) and Ngulube (2019) also point out that active engagement provided by a library develops students into explorers who can formulate and focus their searches in a safe and supportive environment. According to Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) ground-breaking study, students prefer a library environment that builds on existing knowledge and links to the curriculum and content required to efficiently assist them in completing their learning tasks.

Organizations such as the International Federation of Library Associations and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organizations (UNESCO) continue to emphasize the significance of school libraries as tools that assist in enhancing quality education (Hauke et al., 2021). However, the profound impact that libraries as pedagogical hubs can have in shaping young minds in schools and enhancing learner achievement is often overlooked (Subramaniam et al., 2015). The potential of school libraries to transcend their conventional functions and emerge as dynamic agents of pedagogical innovation has not been fully explored.

School libraries, which are recognized globally as resources that enhance research, critical thinking, and problem solving for both teachers and learners, are a farfetched dream for many rural schools in South Africa (Ngulube, 2019; Mahwasane, 2022). For the few rural schools that are privileged to have a library, it is either poorly resourced or poorly managed. Some of these libraries have been turned into storage spaces as school authorities lack the adequate knowledge and initiative to turn them into teaching and learning hubs (Mojapelo, 2016). As such, a lack of knowledge on how school libraries can improve teaching and learning widens the educational disparities in South African schools, especially those located in rural areas that often lack adequate teaching and learning resources. Reconceptualising school libraries as innovative learning hubs offers unique opportunities to tackle educational inequalities and improve learners' academic success in marginalized and impoverished schools. This study, therefore, investigates the transformative capacity of school libraries and how they can enhance student engagement, improve teacher pedagogies, and create a more inclusive learning environment. By studying six rural South African schools where new libraries were established, this research sought to shed light on the transformation of school libraries from passive resource centers to active facilitation centers for teaching and learning. The study's objective was to investigate how school libraries can serve as innovative pedagogical hubs capable of enhancing the quality of teaching and learning in under-resourced rural South African schools. Deriving from this objective, the key question underpinning the study is: How can school libraries be utilized as innovative hubs to transform teaching and learning in rural education ecosystems?

2 Literature review

2.1 Significance of libraries as teaching-learning hubs

School libraries have played a significant role in enhancing and providing support to teaching and learning throughout the years as they have evolved from being just places where books are found and mere repositories of information to multifaceted spaces that promote research, inquiry learning, and supplement conventional teaching (Souza and Balduíno, 2023). School libraries are seeds in which knowledge is stored and mined for the growth of innovative, effective, and efficient teacher pedagogies that promote learner achievement (Mondal, 2021). They also provide essential resources that supplement and scaffold traditional teaching. Malekani and Mubofu (2019) point out that school libraries act as extra or second classrooms for learners, which go the extra mile of not only providing quality education but also nurturing learners' moral development. Libraries empower educational institutions to produce resourceful individuals who positively impact national development (Mahwasane, 2017). Among the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), SDG4 focuses on access to quality education, which includes but is not limited to the provision of learning opportunities that go beyond the classroom, fostering a lifelong learning culture and inclusive education of all (Adipat and Chotikapanich, 2022; Dei and Asante, 2022).

2.2 Role of libraries in bridging the teaching-learning gap

As Olajide et al. (2023) put it, school libraries are prolific educational resources that allow learners to inquire more deeply into knowledge, enhancing their comprehension skills, which traditional pedagogies may not adequately provide. School libraries are a necessary resource in rural schools because they promote dynamic, transformational, engaging, and collaborative educational environments (Schultz-Jones et al., 2021; Mahwasane, 2022). Libraries also promote curiosity in learners making them develop an interest in all subjects, including STEAM disciplines. The wealth of knowledge discovery that libraries offer aligns with STEAM education, which requires teaching and learning to develop explorative inquiry, critical thinking, problem-solving, and experiential skills (Mitchell et al., 2020). Consequently, establishing effective school libraries with knowledgeable librarians and library programs that integrate available information with subject content is essential in creating teaching and learning that is innovative and stimulating.

2.3 Challenges in rural education ecosystems

Countries that are categorized as developed have heeded the call by various organizations such as the International Federation of Library Associations, and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organizations (UNESCO) to ensure schools have well-resourced and staffed school libraries that are integrated into the curriculum and co-curricular needs (IFLA School Libraries Section Standing Committee, 2015; Oberg, 2018). However, in developing and underdeveloped countries such as South Africa, several challenges are experienced, including establishing and maintaining functional libraries, especially in rural areas (Mojapelo, 2016). In South Africa, schools located in rural ecologies face severe challenges like a lack of basic teaching-learning resources, textbooks, laboratory equipment, internet access, digital resources, and funding constraints (National Education Infrastructure Management System, 2020; Netshivhumbe and Mudau, 2021; Shikalepo, 2020). Rural areas are characterized by marginalization and are plagued by inefficient health services and systemic poverty, resulting in schools lacking basic infrastructure and resources (Du Plessis and Mestry, 2019; Muremela et al., 2021).

Mojapelo (2016) paints a grim picture of library establishments and maintenance in rural South Africa. This is linked to the lack of policy specifications and resources, which can be traced back to the inequalities inherited from the apartheid era. As such, library access in rural areas in South Africa appears to be a farfetched dream that is unattainable, leading to learning that is deprived of valuable resources and opportunities for learners' academic growth (Ngulube, 2019). These challenges affect not only the establishment and maintenance of school libraries. Bopape et al. (2021) point out that community libraries are also affected as they lack space and have outdated resources and internet access. Yet, school libraries have the potential to play a critical role in rural schools by serving as information repositories and dispensers that support teachers and learners (Mahwasane, 2017; Oluwaniyi, 2015).

3 Conceptual framework

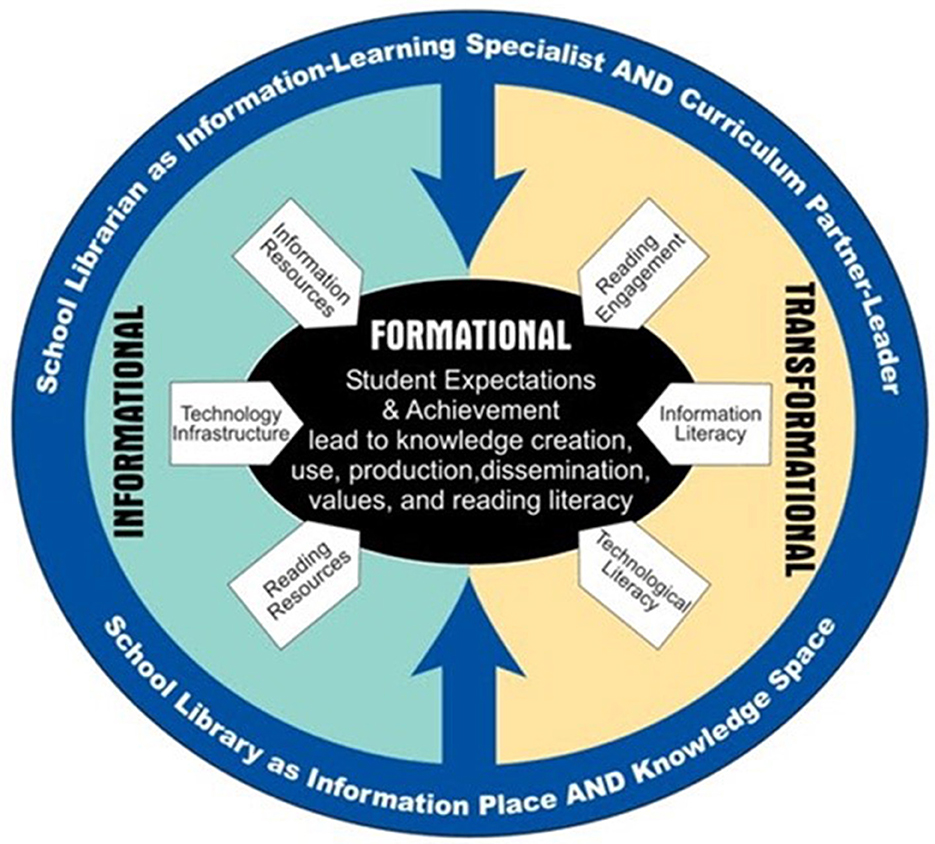

The conceptual framework illuminating this study is directly adopted from Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) model of the school library as a dynamic agent of learning (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of the school library as a dynamic agent of learning (Todd and Kuhlthau, 2005, p. 6).

Within the dynamic realm of education, school libraries are essential for supporting students' lifelong learning and intellectual development (Nayak and Bankapur, 2016). Todd and Kuhlthau's model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the dynamic nature of school libraries as agencies of learning. Libraries have interconnected formational, informational, and transformational elements. These elements, as Todd and Kuhlthau (2005) posit, function interdependently to ensure effective information access and learning for students. The cohesive, interlinked, and unified ways the elements work illustrate the role of school libraries as dynamic agency for teacher and student learning (Dix et al., 2020). Todd and Kuhlthau (2005) regard the library as an instructional agent from which teachers and students can benefit through operational engagement. They further argue that perceiving the school library as an agent of learning eliminates the passive view that libraries are just an agency for the supply and exchange of information.

Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) model of the school library as a dynamic agent of learning is an appropriate framework for illuminating the current study for three reasons. Firstly, the model helps in exploring the role of school libraries as innovative teaching-learning hubs in rural education ecosystems experiencing resource marginalization. Libraries can create spaces where students are empowered to learn, collaborate, and cultivate a lifelong yearning for knowledge acquisition and creation (Nayak and Bankapur, 2016). Secondly, the model is useful in guiding our study as it reinforces the positive role played by libraries in schools such as maximizing learning opportunities and outcomes. Thirdly, Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) model helps in understanding how school libraries develop learners' (as well as teachers') higher-order thinking skills, the ability to engage in reasoned conversation, and recognize knowledge as problematic, fluid, and continuously evolving.

4 Research methodology

This paper is generated from a bigger project that initiated and established school libraries in three primary and three secondary schools in a rural school district in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The project was a multi-sectoral collaborative effort involving university lecturers, librarians, and district and school management officials who saw potential in improving teaching and learning by establishing school libraries in a rural education ecosystem.

4.1 Ethical considerations

The study was granted ethical clearance by the University of the Free State and the Eastern Cape Provincial Department of Education. The Ethical Clearance Number is UFS-HSD2022/0428/22/4. The project has a signed memorandum of understanding with the six schools that participated in the study. The 12 teachers who directly participated in this research signed informed consent forms, which emphasized that taking part in the study was voluntary. They were free to withdraw from the research at any time without providing reasons, and there were no repercussions for doing so.

4.2 Research approach

A qualitative research approach (Creswell, 2020; Leedy and Ormrod, 2020), which required the gathering of in-depth data from research participants in their natural settings, was adopted for this study. The sampled teachers shared their perspectives and lived experiences (Aspers and Corte, 2019) on the establishment and access to school libraries in their natural and familiar rural environments. This enabled the researchers to gain in-depth insights into how school libraries can contribute to teachers' innovative and improved pedagogical practices.

4.3 Research paradigm

The study was framed using the interpretive paradigm (Creswell and Poth, 2018). This paradigm assumes that knowledge is derived from an individual's interpretation of their lived experiences. The sampled teachers shared their views and understanding of how the established libraries assisted and brought innovation into their teaching and learning spaces, as well as pedagogical practices.

4.4 Research design

A multiple case study design (Halkias et al., 2022) was employed involving six rural schools to gather data on teachers' conceptualization of the role of school libraries and their lived experiences in using them to improve their classroom practices. Yin (2018) posits that using two or more cases that share similar characteristics but differ in other ways is useful in gaining a deeper understanding of the same phenomenon across multiple research sites and settings. The six schools served as multiple case studies in this research, which selected two teachers as study participants from each school.

4.5 Setting and sampling procedure

The schools in which the libraries were established were the research sites for this study. Three primary and three secondary schools were sampled from a rural education district in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Six schools in which libraries were established by a group of three university lecturers, three librarians, three Department of Education officials from the district, and the school stakeholders were the research sites. Two teachers were sampled from each school, giving a total sample size of 12. The selected teachers were teaching across all the four phases, that is, the Foundation Phase (Grades 1 to 3), the Intermediate Phase (Grades 4 to 6), the Senior Phase (Grades 7 to 9), and the Further Education and Training Phase (Grades 10 to 12). Subjects taught by participants are regarded as critical subjects in the South African education context; these were mathematics, natural sciences, physical sciences, technical subjects (engineering, graphics and design, and technical sciences), and life skills. The teachers were purposively selected based on the subjects they taught. The languages—though regarded as critical subjects—were excluded from this study because the focus was on mathematics, the sciences, and life skills. Mathematics and the sciences are regarded as difficult by both teachers and students, as evidenced by poor performance in public examinations (Kusuma and Susantini, 2022; Kusuma et al., 2020; Subramaniam et al., 2015). By establishing school libraries in the six targeted schools, the current study investigates whether libraries would improve the teaching and learning of mathematics and the sciences in rural primary and secondary schools.

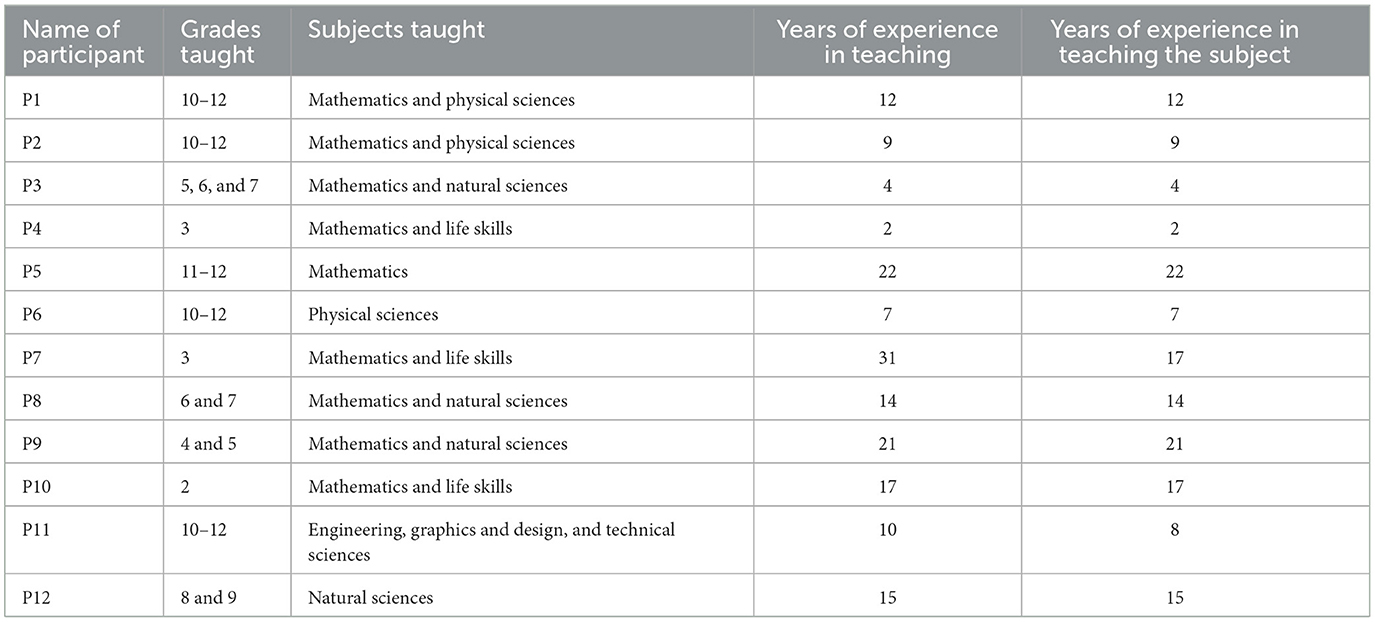

4.6 Case description

A profile of the participants sampled in this study is provided in Table 1 below. To adhere to ethical requirements of anonymity, participants' identities were concealed by using numbers in place of their actual names. Participants were numbered 1 to 12. Tags P1 to P12 were used to present data and discuss the findings. The 12 participants were teaching mathematics and the sciences in different classes ranging from Grades 2 to 12. Their experience as classroom practitioners teaching the specified subjects ranged from 2 to 31 years.

4.7 Data collection

Data for this study were gathered through semi-structured interviews. The main benefit of this type of interview, according to Ruslin et al. (2022), is that it affords researchers the flexibility to modify the questions they ask depending on the answers given by the respondents. Researchers can use probing questions to follow up on responses given (Ruslin et al., 2022; Shoozan and Mohamad, 2024), allowing them to discover deeper information than initially anticipated. Though an interview protocol was prepared beforehand as a guide to the interview conversation, probing, and follow-up questions were not confined to the schedule, affording researchers novel, and profound insights into the phenomena under discussion.

4.8 Data analysis

Qualitative content analysis (Roller, 2019) was used to categorize data into manageable units. The researchers examined data and extracted common concepts, which they classified into categories (Bingham and Witkowsky, 2022). After data categorization, similar categories were analyzed and compacted to generate themes that are aligned to the research question anchoring this study. The research question driving the study is: “How can school libraries be used as innovative hubs to transform teaching and learning in rural education ecosystems?” Five themes guided the presentation of data on the potential of school libraries as innovative pedagogical hubs. The four themes those linchpins the presentation of findings are unpacked in the subsequent section.

5 Presentation of findings

This study sought to explore the potential of school libraries as innovative pedagogical hubs. Data generated from the 12 interviews with teachers is presented utilizing five themes, which are: (i) improved lesson preparation, (ii) increased learner engagement, (iii) promotion of learner-centered environments, (iv) curriculum differentiation, and (v) mitigating resource scarcity in rural schools.

5.1 Improved lesson preparation

Data revealed how the school library acted as an additional information center that assisted teachers in enhancing their knowledge of subject matter and improving their pedagogical skills for content presentation in class. P3 explained that:

On my side libraries contribute a lot. It makes my teaching easier than going around to find information. Compared to previous years when we did not have a library, it has helped a lot, as we go to the library as teachers to gain more knowledge on what we teach. We no longer use the old teaching styles, as we also use e-learning now. The collaboration with other teachers due to library access has enabled us to connect and it is easy to get information.

P4 added:

We need to be equipped with resources as teachers. We need different books to prepare for a lesson, and the library, therefore, helps us in that way, though it still needs more resources for Mathematics and other subjects.

According to P5:

First of all, we do not have enough textbooks. So, the visuals that are available in the library help us to show the learners, for example, some of the geometric figures they do not know and cannot see. So, it provides support with visuals where our learners can see what you are talking about, instead of drawing on the chalkboard. When I sit there and plan to prepare a lesson, I see that I can use this part for the introductory part of a lesson. As learners are different … now we have visuals, but we still need audio-visual support as well.

P7 also remarked that: “The library gives more information, especially in these subjects that are not easy to understand, like mathematics and the sciences.”

In the above verbatim quotations, all four participants pointed out how the newly established school libraries have afforded them easy access to a variety of visual materials, extra resources, and additional textbooks that improved their lesson preparation and subsequent presentations. Data from the interviews provided evidence on the dynamic role the school libraries played in improving lesson preparation as one aspect that can improve classroom practice. Resources available in the library offered a myriad of visual resources that provided teachers with support to transcend traditional teaching approaches they previously used before school libraries were established.

5.2 Increased learner engagement

The findings of the study indicated the role libraries played in motivating learners. This increased learner engagement during lessons and even after, as they were able to visit the library to consolidate what they had learnt or to read ahead in preparation for upcoming lessons.

P1 was full of praise for the library as an innovation hub:

We are fortunate as a school as many schools have no libraries. It creates a lot of impact for learners because they are always in the library. The posters make it easier for them to understand than using their books. The environment of the library is very unique and clean. So, the learning environment becomes fruitful. I would say, it changes the learning environment, especially for learners who are doing grade 12; they are very happy.

P9 emphasized the success of the school libraries in enhancing learner involvement:

The library use for learner engagement is very successful. You, as the university, delivered a lot of resources that are useful. We go with the learners to the library to show them what we are talking about when teaching. We start by presenting a lesson in class, and then go and engage learners in the library. Before we had the library, learners were unable to be engaged in what is presented in class, and now the library is here and there is someone who assists them there, with visuals and they get so happy.

Similar sentiments were echoed by P10, who remarked that:

Learners go to the library and do research, improving their reading and writing. They have a variety of resources, and they learn by doing instead of listening. Now that we have a library, it has become interesting to teach Mathematics.

These extracts from participant interviews show teachers' appreciation of the school library resources and their benefits to learner engagement. The data revealed how school libraries provided learners greater accessibility to knowledge, motivated independent research, and active involvement in the search for new knowledge. This promoted increased learner engagement with library resources as well as participation in classroom activities during lessons. School libraries, therefore, support the important drive for innovative pedagogy that is in sync with the rapidly changing 21st century. The evidence of improved research skills and independent learning, as well as active participation, also showed the dynamic role libraries played in ensuring effective teaching and learner agency.

5.3 Promoting learner-centered environments

Data from the semi-structured interviews also indicated that libraries assisted teachers in promoting learner-centered environments. The participants shared that the school libraries stimulated learners' quest to find more information through self-directed learning. This developed learners' critical thinking skills as they gained a deeper understanding of the concepts they were learning.

P12 explained that:

Having a library in the school helps learners with the resources that are available to label, for example, body systems. It helps in the classroom as I and the learners are part of using the library resources. Learners have gotten used to using books. It forms part of the teaching and learning process as there are visuals that assist in demonstrating to learners what you mean. Our library is new, but I can already see that there is going to be an improvement in teaching and learning as learners can go to the library without my presence which is not there in many schools. We need more charts though.

P2 elaborated:

The school library is a very powerful tool in teaching and learning, as our learners need to collect more information beyond the classroom. So, one of the ways, as this is a village without access to the internet, the library provides them with such information. It stimulates learner thinking as they have access to different materials such as textbooks, which improves their understanding of the concepts. Sometimes in class, we have challenges of time constraints, and the library empowers them with a deeper understanding of concepts. As teachers, especially in Maths and Sciences, we bring different methods to solve problems in these critical subjects, but with the assistance of the library, the learners are able to find more easier methods to solve the problems that we may have not discussed in class.

P4 had this to share:

In teaching, we talk a lot, but when problem-solving is needed, you must explain. When you are talking about these things theoretically, the library most of the time shows them concrete material and they start thinking deeply which makes them inquisitive, especially planets and earth, but they need to see them…, the library provides that which makes it easy to understand.

In the same vein, P8 shared similar sentiments:

Kids are by nature curious, they always ask questions, how, when, what, how did it come to this, and why are we saying the buildings outside are standing still because of the air pressure that is less outside than inside? The libraries create enthusiasm for them to learn more about any content you have delivered as a teacher. It stimulates their thinking skills. The library wins them to know more independently as an individual and think beyond while they are in primary, and in that way, it creates a springboard for them when they progress to higher classes. Take the ear section, for example, who knows if any of the kids will want to be ear doctors in the future? Extra resources such as the library assist in taking learners further in critical thinking and thinking beyond.

The excerpts from the data collected revealed how the school libraries provided learners with resources to explore concepts further in the absence of the teacher. The newly established school libraries served as catalysts for creating learner-centered environments outside the classrooms. School libraries provide opportunity and space for learners to quench their curiosity and show initiative to search for answers to questions that interest and intrigue them. When learners explore new ideas in the library on their own, this helps in creating a learner-centered environment outside classroom spaces.

5.4 Curriculum differentiation

The data revealed that school library access assisted teachers with curriculum differentiation, to cater for learner diversity. The library provides space for learners to search for new knowledge across subjects, emphasize cross-cutting concepts and show relationships between and across subject disciplines.

P2 remarked that:

“We are able to do curriculum differentiation. Some learners learn better from the charts and others by reading different textbooks available in the library. Availability of different books and different charts enable us to integrate Mathematics with other subjects”

P6 also said:

Libraries assist in …. what do we call this thing, I just forgot the word we normally use..., subject integration. In Maths, we have a chapter that teaches about time zones, and that time zone, for you to be able to teach mathematically to them, you must go a little bit into Geography on the movement of the earth, how it rotates, lines of longitude and the differentiation of hours. Having a library helps integrate the knowledge of these two subjects and gives a more meaningful understanding to the learners.

The extracts above highlight the significance of library access in schools in facilitating teaching across subjects, and the cross-pollination of knowledge across disciplines, made possible by the availability of additional resources in the library. Due to the availability of the newly established school libraries, learners could grasp and understand concepts more meaningfully, according to their preferred learning style.

5.5 Mitigating resource scarcity in rural schools

The participants identified resource scarcity as a challenge in their rural schools. But the newly established school libraries supplemented the availability of teaching and learning materials. The teachers interviewed in this study pointed out that the new school libraries had colorful charts that attracted learners' visual attention, thereby enhancing and extending the knowledge found in textbooks.

P2 narrated that:

First of all, we do not have enough textbooks, for example in Mathematics. The visuals that are provided in the library are very useful in showing the learners some of the geometric figures. For example, which we cannot show them in class.

P4 also had similar views:

The library has textbooks; there are books they can read for enjoyment, dictionaries for further understanding, and there are resources available in the libraries that are not available in the classroom. Learners can use the library in their leisure time, maybe in the afternoon. It is flexible enough to be used according to the learner's individual needs.

P9 added:

It helps us sequence our teaching. For example, there is Analytical geometry, etc. The description given by the teacher in the lesson is not enough; learners need to identify with the beautiful colorful charts, not the black and white illustrations found in the textbooks. So the library helps a lot in supplementing the meager teaching-learning resources available to the teacher. Some of us are not artistic you know.

The data presented emphasized the critical role the school libraries played in addressing resource disparities in their teaching and learning. This underlines the significance of school libraries as they are flexible resources that go beyond what the classroom environment can provide. The school libraries, therefore, not only assist with sequencing lessons but also in alleviating challenges experienced by teachers, such as a lack of artistic skills.

6 Discussion of findings

The findings revealed the significant role played by newly established school libraries in enhancing teachers' pedagogy and supporting learner initiative for self-directed learning in rural education ecosystems. These findings aligns with Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) model of the school library as a dynamic agent of learning which suggests that libraries are critical in supporting students' as well as teachers' lifelong learning and intellectual development. The dynamic role played by these innovative information hubs, as portrayed by participants in the data presented, seems to speak to existing literature on the invaluable contribution of libraries as innovative teaching -learning hubs (Mahwasane, 2022; Mojapelo, 2016; Ngulube, 2019; Todd and Kuhlthau, 2005). The participants explained how the new school libraries assisted them with improving lesson preparation, increasing learner engagement, promoting learner-centered environments, stimulating curriculum differentiation, and mitigating resource scarcity in rural education landscapes. Kalyani and Rajasekaran (2018) note how the teaching and learning environment calls for innovative pedagogies in the 21st century. The current study showed how school libraries create innovative learning environments that stimulate learners' interests, leading to an efficient educational ecosystem in resource-deprived rural settings. Todd and Kuhlthau's model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the constantly evolving nature of school libraries as agencies of learning.

Lesson preparation requires comprehensive planning that involves resources to structure the lesson effectively to achieve its intended outcomes while catering to the diverse needs of each learner. The findings of the study revealed how the school libraries played the role of being multi-faceted information hubs that extended what the classroom could offer, and also assisted teachers with lesson preparation (Mahwasane, 2017, 2022). As the participants shared, sometimes an explanation of a concept in class is not enough as learners may need visual or concrete material to understand that concept and the newly created libraries in the six schools provided these visual and concrete learning materials. The library also assisted teachers in crafting their lesson plans using the additional visual and concrete resources available in the library. Grigoropoulos and Gialamas (2018) emphasize that the foundations and drivers of innovation in education are the teachers. But the teachers also need resources like libraries to plan for their lessons (Bopape et al., 2021). Teachers need to plan their lessons with care and adequate information to ensure that the lessons stimulate the interest of the learners. Therefore, as Sefoka (2021) posits, their pedagogical practices are the basis for the quality, effectiveness, and efficiency of the teaching and learning space to keep up with the pace of knowledge development (Grigoropoulos and Gialamas, 2018). Hence, school libraries are emerging as potential hubs for such knowledge and information (Mondal, 2021).

The findings further revealed how school libraries promoted learner engagement and learner-centered environments. The findings showed that the school libraries provided a flexible space for learners to conduct inquiry-driven searches independently, which promoted critical thinking and independent learning, as recommended by Todd and Kuhlthau's (2005) model of the school library as a dynamic agent of learning. Learners with access to school libraries, as the data indicated, were provided with opportunities to explore and deepen their comprehension of subject content. These findings support the notion of school libraries as second classrooms that foster learner development and quality education (Malekani and Mubofu, 2019). As argued by Mahwasane (2017), school libraries are powerhouses that empower educational institutions to develop individuals who are resourceful and can positively impact society. Olajide et al. (2023) state that school libraries allow learners to be explorative and go beyond what traditional teaching can achieve. This concurs with how school libraries inculcate curiosity in learners which promotes interest in STEAM subjects assumed to be challenging yet important (Mitchell et al., 2020).

School libraries were also found to be resources that promoted curriculum differentiation, also known as subject integration. The school libraries, as the findings indicated, facilitated curriculum differentiation by providing teachers with a variety of resources that allowed them to teach across multiple subjects and also to cater to learner diversity. Such integration enhanced the grasping of concepts more meaningfully and identifying the relations between subjects, which supported a holistic approach to teaching. Todd and Kuhlthau (2005) emphasize the interconnectedness of library elements, which are informational, transformational, and formational. These three elements work in a unified and interdependent manner to ensure that teaching and learning are effective. Dix et al. (2020) argue that the cohesive and unified way in which the elements work shows how the school library is a dynamic agent of learning, operating for the benefit of both teachers and students.

Rural school contexts in South Africa are characterized by limited resources which affect the provision of quality education. South African rural contexts, much as they boast beautiful landscapes and great natural beauty, lack essential teaching resources, including textbooks, lab equipment, ICT, internet access, and funding (National Education Infrastructure Management System, 2020; Shikalepo, 2020; Netshivhumbe and Mudau, 2021). The findings of this study also revealed how teachers struggled with inadequate resources such as textbooks. The findings speak to the marginalization and impoverishment so conspicuous in rural areas and their schools because of the shortage of basic human needs such as efficient health services, poor infrastructure and widespread poverty (Du Plessis and Mestry, 2019; Mojapelo, 2016; Muremela et al., 2021). The participants painted a picture of how the new school libraries assisted in mitigating the resource scarcity, indicating the profound impact of library resources in shaping teaching and learning for improved learner achievement (Subramaniam et al., 2015). School libraries, therefore, contribute to the accomplishment of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (quality education) through the provision of varied materials (Dei and Asante, 2022).

Todd and Kuhlthau (2005) argue that considering and perceiving the school library's core role from the angle of being an agent of learning eliminates the passive view that libraries are just an agency of the supply and exchange of information. Having said this, a limitation to the findings of this study is that data was used to validate Todd and Kuhlthau's model of the school library as a dynamic agent of learning. This makes the findings of the study vulnerable to the risk of theory confirmation instead of capturing new or unexpected insights emerging from the research participants.

7 Conclusion and recommendations

This study aimed at exploring and positioning school libraries as innovative pedagogical hubs in a rural education ecosystem in South Africa using case studies of six purposively sampled schools. The findings revealed that school libraries played a dynamic role in enhancing teaching and learning at these schools as they improved lesson preparation, promoted learner engagement, provided learner-centered environments, assisted with curriculum differentiation, and mitigated resource scarcity. This study has demonstrated the significant role played by school libraries in enhancing the quality of teaching and learning, positively impacting teaching and learning. School libraries have traditionally served as repositories of information. However, this study positioned them as innovative pedagogical development hubs, essentially rethinking their conventional role and suggesting a shift toward more active engagement in the teaching and learning process. The establishment of more school libraries in rural education landscapes can assist to bridge the gap that traditional teaching may miss and, thus, could contribute to an improved teaching-learning environment in impoverished rural education ecosystems. As the educational landscape continues to evolve, school libraries will remain essential partners in fostering the intellectual growth of future generations. The study concludes that, by transforming school libraries from mere repositories of information to innovative pedagogical hubs, libraries have the potential to enhance the quality of teaching and learning significantly. This study, therefore, recommends and advocates for the prioritization of school library provision and access in rural schools if United Nations Sustainable Development Goal Number 4 (which calls for quality education) is to be attained in marginalized and impoverished rural education ecosystems, not only in South Africa but the world over.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of the Free State and the Eastern Cape Provincial Department of Education. The Ethical Clearance Number is UFS-HSD2022/0428/22/4. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

LM-Z: Funding acquisition, Visualization, Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. GC: Conceptualization, Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. A word of gratitude also goes to the National Research Fund (NRF) for funding the project from which this article has been extracted.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants who contributed to this article by sharing their experiences and insights.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adipat, S., and Chotikapanich, R. (2022). Sustainable development goal 4: an education goal to achieve equitable quality education. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 11, 174–183. doi: 10.36941/ajis-2022-0159

African Union Commission (2016). Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. Available online at: http://www.agenda2063.au.int/en/home (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Aspers, P., and Corte, U. (2019). What is qualitative in qualitative research? Qual. Sociol. 42, 139–160. doi: 10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7

Bingham, A., and Witkowsky, P. (2022). Deductive and Inductive Approaches to Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bopape, S. T., Dikotla, M., Mahlatji, M., Ntsala, M. N., and Lefose, M. (2021). Public and community libraries in Limpopo Province, South Africa: prospects and challenges. South Afr. J. Libr. Info. Sci. 87, 9–19. doi: 10.7553/87-1-1810

Creswell, J. (2020). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Qualitative and Quantitative Research, 6th Edn. London: Pearson.

Creswell, J., and Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dei, D.-G. J., and Asante, F. Y. (2022). Role of academic libraries in the achievement of quality education as a sustainable development goal. Libr. Manag. 43, 439–459. doi: 10.1108/LM-02-2022-0013

Dix, K., Felgate, R., Ahmed, S. K., Carslake, T., and Sniedze, S. (2020). School Libraries in South Australia 2019 Census. Australian Council for Educational Research. Available online at: https://research.acer.edu.au/tll_misc/33/

Du Plessis, P., and Mestry, R. (2019). Teachers for rural schools – a challenge for South Africa. South Afr. J. Educ. 39, S1–S9. doi: 10.15700/saje.v39ns1a1774

Grigoropoulos, J. E., and Gialamas, S. (2018). Educator leaders: inspiring learners to transform society by becoming architects of their own learning. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 14, 33–38. doi: 10.29329/ijpe.2018.157.4

Halkias, D., Neubert, M., Thurman, P. W., and Harkiolakis, N. (2022). The Multiple Case Study Design. New York: Routledge.

Hauke, P., Latimer, K., and Niess, R. (Eds.). (2021). New Libraries in Old Buildings. Berlin: De Gruyter.

IFLA School Libraries Section Standing Committee (2015). IFLA School Library Guidelines (2nd rev Edn.). International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Available online at: https://www.ifla.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/assets/school-libraries-resource-centers/publications/ifla-school-library-guidelines.pdf

Kalyani, D., and Rajasekaran, K. (2018). Innovative teaching and learning. J. Appl. Adv. Res. 3:23. doi: 10.21839/jaar.2018.v3iS1.162

Kusuma, A. E., and Susantini, E. (2022). The effect of rode learning model on enhancing students' communication skills. Stud. Learn. Teach. 3, 132–140. doi: 10.46627/silet.v3i3.170

Kusuma, A. E., Wasis, S. E., and Rusmansyah (2020). Physics innovative learning: RODE learning model to train student communication skills. J. Phys. 1422:12016. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1422/1/012016

Leedy, P., and Ormrod, J. (2020). Practical Research: Planning and Design (12th Edn.). London: Pearson.

Mahwasane, N. (2022). Prevailing status of school libraries in South Africa: challenges and suggestions. J. Sociol. Soc. Anthropol. 13, 87–97. doi: 10.31901/24566764.2022/13.3-4.384

Mahwasane, N. P. (2017). The influence of school library resources on students' learning: a concept paper. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 17, 190–196. doi: 10.1080/09751122.2017.1305739

Malekani, A., and Mubofu, C. M. (2019). Challenges of school libraries and quality education in Tanzania: a review. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2334, 1–4. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2334

Mitchell, B., Ratcliffe, C., and LaConte, K. (2020). STEAM learning in public libraries: a “Guide on the Side” approach for inclusive learning. Child. Libr. 18:7. doi: 10.5860/cal.18.3.7

Mojapelo, S. M. (2016). Challenges in establishing and maintaining functional school libraries: lessons from Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 50, 410–426. doi: 10.1177/0961000616667801

Mondal, H. (2021). Overviews of knowledge management with the role of library and library professionals in the 21st century [Paper presentation]. Knowledge Management in Higher Education Institutions, Manipal University and University Library Uva Wellassa, Srilanka.

Muremela, G., Kutame, A., Kapueja, I., and Adigun, O. T. (2021). Retaining scarce skills teachers in a South African rural community: an exploration of associated issues. Afr. Identities 21, 1–17. doi: 10.31920/2516-5305/2020/17n3a4

National Planning Commission (2013). National development plan vision 2030. Available online at: http://www.gov.za/issues/national-developmentplan-2030 (Accessed May 15, 2024).

National Education Infrastructure Management System (2020). School Infrastructure Report 2020. Department of Basic Education. Available online at: https://equaleducation.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/DBE-NEIMS-REPORT-2020.docx.pdf

Nayak, S. N., and Bankapur, V. M. (2016). “Foster with school libraries: impact on intellectual, mental, social and educational development of a child,” in National Conference Proceedings School Libraries in Digital Age (COSCOLIDIA) (Belgaum: Bharatesh Education Trust), 1–11. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319930872_Foster_with_School_Libraries_Impact_on_Intellectual_Mental_Social_and_Educational_Development_of_a_Child

Netshivhumbe, P. N., and Mudau, A. V. (2021). Teaching challenges in the senior phase natural sciences classroom in South African schools: a case study of Vhembe district in the Limpopo province. J. Educ. Gifted Young Scient. 9, 299–315. doi: 10.17478/jegys.988313

Ngulube, B. (2019). “School libraries are a must in every learning environment: advocating Libraries in High Schools in South Africa,” in Handbook of Research on Advocacy, Promotion, and Public Programming for Memory Institutions (London: IGI Global Scientific Publishing), 297–312.

Oberg, D. (2018). New international school library guidelines. Knowl. Quest 46, 24–31. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1182645.pdf

Olajide, O., Oyeniran, K. G., Anyakorah, O. Z., Omolehin, R. J., and Lucas-Elumah, B. A. (2023). Influence of school library on implementing qualitative science education in Nigeria: impediments and the possibilities. Communicate 25, 228–246. Available online at: https://www.cjolis.org/index.php/cjolis/article/view/38

Oluwaniyi, S. A. (2015). Preservation of information resources in selected school libraries in Ibadan North Local Government Area of Oyo State, Nigeria. Libr. Philos. Pract. 1, 1–32. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1220

Roller, M. R. (2019). A quality approach to qualitative content analysis: similarities and differences compared to other qualitative methods. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 20, 1–21. doi: 10.17169/fqs-20.3.3385

Ruslin, R., Mashuri, S., Rasak, M. S. A., Alhabsyi, F., and Syam, H. (2022). Semi-structured interview: a methodological reflection on the development of a qualitative research instrument in educational studies. IOSR J. Res. Method Educ. 12, 22–29. doi: 10.9790/7388-1201052229

Schultz-Jones, B., Farabough, M., and Hoyt, R. (2021). “Towards consensus on the school library learning environment: a systematic search and review,” in IASL Annual Conference Proceedings. doi: 10.29173/iasl7471

Sefoka, I. M. (2021). Building the builders to ensure delivery of good quality education in South Africa: a critical legal insight. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 11:64. doi: 10.36941/jesr-2021-0077

Shikalepo, E. E. (2020). Challenges facing teaching at rural schools: a review of related literature. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 4, 211–218. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340272978_Challenges_Facing_Learning_at_Rural_Schools_A_Review_of_Related_Literature

Shoozan, A., and Mohamad, M. (2024). Application of interview protocol refinement framework in systematically developing and refining a semi-structured interview protocol. SHS Web Conf. 182:04006. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/202418204006

Souza, A., and Balduíno, Â. (2023). School library. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 10, 61–66. doi: 10.22161/ijaers.107.9

Subramaniam, M., Ahn, J., Waugh, A., Taylor, N. G., Druin, A., Fleischmann, K. R., et al. (2015). The role of school librarians in enhancing science learning. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 47, 3–16. doi: 10.1177/0961000613493920

Todd, R., and Kuhlthau, C. (2005). Student learning through Ohio School Libraries, Part 1: how effective school libraries help students. Sch. Libr. Worldwide 11, 89–110. doi: 10.29173/slw6958

Todd, R. J. (2021). “From learning to read to reading to learn: school libraries, literacy and guided inquiry,” in IASL Annual Conference Proceedings.

Keywords: innovative pedagogy, rural ecosystem, rural schools, school libraries, teaching and learning

Citation: Mdodana-Zide L and Chimbi GT (2025) Transforming education in a rural ecosystem: school libraries as hubs for teaching-learning innovation. Front. Educ. 10:1601206. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1601206

Received: 27 March 2025; Accepted: 15 July 2025;

Published: 30 July 2025.

Edited by:

Kizito Ndihokubwayo, Parabolum Publishing, United StatesReviewed by:

Ramanan Thankavadivel, University of Colombo, Sri LankaIrella Bogut, Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Croatia

Copyright © 2025 Mdodana-Zide and Chimbi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Godsend T. Chimbi, Q2hpbWJpR1RAdWZzLmFjLnph

Lulama Mdodana-Zide

Lulama Mdodana-Zide Godsend T. Chimbi

Godsend T. Chimbi