- Faculty of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities, Kaunas University of Technology, Kaunas, Lithuania

Introduction: The present study was conducted to address the lack of qualitative data on the motivations for pursuing a career in teaching. A strategically important aspect of the current and projected teacher shortage in many countries is the experience and skills that career changers bring to the educational environment. Research has shown a trend for specific prestige characteristics to dominate as an aspect of the attractiveness of the teaching profession. However, the prestige of the teaching profession is a dynamic phenomenon, and in many contexts worldwide, it is low or declining. Therefore, what motivates individuals from other career paths to become teachers and counterbalance the profession’s low prestige is a highly relevant and under-researched issue, as this understanding can help teacher educators address the expectations of career changers. The main aim was to identify the specific motivations that prompt individuals from diverse professions to pursue teaching as a career in a context of low professional prestige.

Methods: Qualitative data was gathered from 109 career-change teaching students (hereafter, CCTs). A reflexive thematic analysis of the motives of career-changing teachers revealed that intrinsic and altruistic motives align with the findings of other studies but differ in some aspects.

Results and discussion: That is, their commitment to improving the world is inspired by the desire to contribute to enhancing education and to realise their perceived professional and personal potential without fear of professional challenges such as low popularity, relatively low salaries, and high responsibilities. CCTs’ motives for transitioning into teaching from other fields have revealed that teaching was a natural continuation of their previous careers, a way to contribute to the improvement of the educational system, a means to become part of an organization, and (in the case of emigrants) to join the ethnic community. The study concludes with recommendations and suggestions for career education specialists, teacher education institutions, and potential avenues for further research.

1 Introduction

Teachers play a highly important role in providing quality education. Every country aspires to such a provision because it is the key to societal growth (European Council, 2020) and one of the Sustainable Development Goals—4, quality education for all (The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2024b). However, the challenges of social and environmental change (e.g., rapid digitalization and threats such as pandemics and climate change) have imposed new requirements and expectations on teachers, reducing their security and stability (European Commission, European Education, Culture Executive, Agency, Motiejunaite-Schulmeister et al., 2021). In many countries, the profession suffers from low prestige; this, along with the associated daily stress, feelings of worthlessness, and exhaustion, makes teaching an unattractive career option for many (Yinon and Orland-Barak, 2017; The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2024a). Additionally, a widespread perception exists in many countries that teaching is a backup career for those unable to pursue prestigious and financially rewarding alternatives (Imanuel-Noy and Schatz-Oppenheimer, 2023; Richardson et al., 2014; Siostrom et al., 2023). Partly due to this—and with a few notable exceptions—there is a global shortage of teachers (Craig et al., 2023; Siostrom et al., 2023; The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2024a). The problem stems from the fact that teachers in their 60s are retiring but are not being replaced by younger individuals, and some of the latter do not immediately join the sector (European Commission, European Education, Culture Executive, Agency, Motiejunaite-Schulmeister et al., 2021). Additionally, schools with pupils from low socio-economic status are approximately six times more likely to experience teacher shortages than wealthier schools (OECD, 2018). To resolve this issue, research and political attention must be directed toward teacher training, career development, retention, and attracting specialists in specific fields (Dawborn-Gundlach et al., 2025; Frison et al., 2023; Hogg et al., 2023). Career-changing teachers (CCTs, also referred to as second-career teachers) are part of a broader educational strategy aimed at addressing current and projected teacher shortages (Dadvand et al., 2024; Negrea, 2024). A career change is a transition from one job to another in a different field largely unrelated to previous job skills or responsibilities (Carless and Arnup, 2011). Previous studies have analyzed career change as a mid-life transition around the age of 40, when individuals experience lower career satisfaction and decide on alternative careers (Wilkins, 2017). These individuals have been referred to as career switchers (Mayotte, 2003) or mid-career entrants (Marinell and Johnson, 2014). But contemporary socio-economic changes have also modified the profile of career changers (Bar-Tal et al., 2020; Dadvand et al., 2024). Career change teachers are defined as persons who begin to work as teachers later in life (Hogg et al., 2023; Priyadharshini and Robinson-Pant, 2003), at the age of 21 or 25 (Varadharajan and Buchanan, 2021), and have at least 6 months full-time work experience or 3 years occupied in a career other than that of teaching; this may include full- or part-time, paid or unpaid work, and/or parenting and volunteer work (Williams and Forgasz, 2009). The literature also suggests that CCTs should refer to individuals who enter teaching after transitioning from other professions without considering age (Beutel et al., 2019). CCTs who solve the teacher shortage problem are game-changers, as they fill vacant positions and bring valuable skills and knowledge to the teaching profession due to their previous work experience (Tigchelaar et al., 2008; Williams, 2013). They offer broader competence as well as unique life experiences (den Hertog et al., 2023; Hogg et al., 2023; Siostrom et al., 2023; Stanišauskienė, 2022; Varadharajan and Buchanan, 2021). Studies have shown that CCTs have all the characteristics of qualified teachers: a good work ethic (Williams, 2010), well-developed communication skills and empathy toward pupils and parents (Whannell and Allen, 2014), and strong motivation and dedication for teaching (Bauer et al., 2017; Wilkins and Comber, 2015; Williams and Forgasz, 2009; Zuzovsky and Donitsa-Schmidt, 2014). They are also able to respond to unpredictable circumstances (Bar-Tal and Gilat, 2019) and show a greater interest in professional development (Callahan and Brantlinger, 2023; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2025). However, the work and life experience advantage of career-changing teachers does not automatically translate into better teaching skills, i.e., they are less effective in teaching the subjects they teach (Boyd et al., 2011). CCTs often report feelings of frustration because they have underestimated the demands of a new profession (Siostrom, 2024) and experience reality shock at the beginning of their work, especially when faced with the responsibilities of a classroom teacher (Kelchtermans and Ballet, 2002), the heavy workload (Dadvand et al., 2024), and the school’s inability to provide the support and recognition of their previous skills, expertise, and experience (White et al., 2024). And while recent research (Dadvand et al., 2024) reveals that CCTs are reflective about their decision-making and determined to remain teachers despite the challenges, another proportion of CCTs tend to leave teaching quickly (Dadvand et al., 2024; Siostrom et al., 2023; Siostrom, 2024).

Since the mid-20th century, considerable attention has been devoted to understanding why people choose to transition into teaching careers. The reasons have been classified into extrinsic and intrinsic categories, including altruistic (Brookhart and Freeman, 1992; Sinclair, 2008), pragmatic, altruistic, and personal motivations (Laming and Horne, 2013), as well as contextual, extrinsic, altruistic, and intrinsic motivations (Siostrom et al., 2023). At the same time, career change has been analyzed as a set of value-expectation motives (Hunter-Johnson, 2015; Watt and Richardson, 2007) or the result of social and personal factors (Bauer et al., 2017). One aspect of the attractiveness of the teaching profession is the prestige associated with it, which is a factor in career choice (Fico, 2024; Pérez-Díaz and Rodríguez, 2014). In some countries of the world (Dolton et al., 2018; Finnish National Agency for Education, 2018; Korhonen and Portaankorva-Koivisto, 2021; Lucksnat et al., 2022; Wrona et al., 2025), teaching is highly valued and respected, e.g., in Finland, Ireland, Germany, Singapore, Spain, Poland, Turkey, the prestige of the teaching profession is high and can attract career changers motivated by the desire to become part of a prestigious profession (Gorard et al., 2024). But in other contexts, where the profession is undervalued, its prestige is moderate, as in Australia, Belgium, and France (Coppe et al., 2023; Farges, 2025; Mockler, 2022), low or falling, like in the United States, and Lithuania (Bakonis, 2021; Callahan and Brantlinger, 2023), these attitudes can act as a dissuasion (Gorard et al., 2024; Siostrom et al., 2023). De Camargo and Whiley (2020) argue that the prestige of a profession is a dynamic and multidimensional phenomenon, encompassing not only social status but also income, educational attainment, professionalism at work, and societal attitudes toward a profession. Teachers’ professional prestige is determined by the income they earn or can earn, the psychological comfort they feel, and the perception of the respect shown by society to the teaching community (Mockler, 2022). Teacher shortages are often linked to a decline in the prestige of the teaching profession (De Camargo and Whiley, 2020; Gorard et al., 2024). Many concerns about the prestige of the teaching profession are voiced in the media, highlighting the profession’s low prestige and influencing public thinking, thereby creating a culture of “teacher-bashing” (Mockler, 2022). In many countries, the low or declining prestige of the teaching profession in society is reflected in the low take-up of teaching by young people who have graduated from general education, not only because of low salaries, age and gender disparities within the teaching community, or limited career opportunities but also because of a lack of freedom of autonomy, a lack of confidence in the teaching profession as a professional (Bakonis, 2021). Fico (2022) states that one of the reasons for the decline in professional prestige is the high level of responsibility in the teaching profession. Thus, what motives career changers have in deciding to go into teaching outweigh the low prestige of the profession is a highly relevant and under-researched issue, as this understanding may help to change the discourse on teaching careers in society and offer support and preparation programmes that match CCTs’ expectations (Frison et al., 2023). To assist in the career transition process, it is necessary to investigate the reasons why educated individuals with work experience in other fields decide to pursue teaching careers more deeply (Negrea, 2024; Nilsson and Cederqvist, 2025; Smetana and Kushki, 2021).

2 Literature review

The mounting literature on the motives for CCTs (e.g., Geoghegan, 2023; Hogg et al., 2023; Imanuel-Noy and Schatz-Oppenheimer, 2023; Kavanagh, 2024; Nilsson and Cederqvist, 2025; Watters and Diezmann, 2015) draws on several theories of motivation, including expectancy-value theory, achievement theory, and self-determination theory. According to self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2020), there are extrinsic and intrinsic motives for CCTs’ choice to teach, with a particular emphasis on altruistic motives. Research on CCT motivation (Geoghegan, 2023; Hunter-Johnson, 2015; Koç, 2019; Kavanagh, 2024; Laming and Horne, 2013; Zuzovsky and Donitsa-Schmidt, 2014) has shown that individuals have a blend of extrinsic, intrinsic, and altruistic motives in their decision to pursue teaching. Extrinsic motives are the motivating forces for action that originate from outside sources (Ryan and Deci, 2020). Extrinsic motivation consists of incentives and rewards that are seen as controlling or compelling a person to behave in a certain way. External determinants of the CCT’s choice to teach include the influence of family members, relatives who are teachers (Geoghegan, 2023; Lucksnat et al., 2022), job security and stability, opportunities for continuous professional development (Berger and D’Ascoli, 2012), positive previous teaching experience (Lucksnat et al., 2022; Siostrom, 2024; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2025), policy initiatives and recruitment programmes offering financial incentives, schools as workplace environments (Berger and D’Ascoli, 2012; Callahan and Brantlinger, 2023), the need to change careers because of the economy and the pension and health care benefits in the teaching profession (Bunn and Wake, 2015).

Intrinsic motives lead to action because they are enjoyable, promote personal fulfillment, and are interesting (Ryan and Deci, 2020). For CCTs, these include a long-standing desire to teach from childhood (i.e., Bauer et al., 2017), the ability to teach, the desire to work with children and adolescents (i.e., Lucksnat et al., 2022), the search for meaning in a career (Hunter-Johnson, 2015), the pursuit of a work-life balance (Berger and D’Ascoli, 2012), a passion for the subject, and the pursuit of personal fulfillment (Alvariñas-Villaverde et al., 2022; Geoghegan, 2023). A type of intrinsic motivation is altruistic motivation, which focuses on enhancing the wellbeing of others (Friedman, 2016) by selflessly thinking and caring about the interests of others (Knell and Castro, 2014). Altruistic motives are associated with social value and desire to make a difference in the education of children and young people when teachers prioritize the well-being of students over their own personal wellbeing (Bauer et al., 2017; Laming and Horne, 2013), as well as serving the community and the common good (Hunter-Johnson, 2015; Tigchelaar et al., 2008). Moreover, altruistic, service-oriented goals and other intrinsic motivations are the main reasons why teacher candidates choose a teaching career (Bauer et al., 2017).

Notwithstanding, these categories are insufficient to convey the complex influence of interrelated motives. The Factors Influencing Teaching as a Career Choice model (FIT-Choice; Watt and Richardson, 2007) is based on the theories of expectancy and value (Eccles, 2009) and social cognitive career (Lent et al., 1993). The FIT-Choice model comprises five groups of motives, including: “socialization influences,” “task perceptions,” “self-perceptions,” “values,” and “fallback career.” Socialization influences include both encouragement and discouragement, as well as dissuasion from becoming a teacher. Task perception, or the perception of a teacher’s performance, encompasses the demands placed upon them (such as competence and readiness to overcome difficulties) and the rewards offered (e.g., social status and salary). When assessing self-perception, emphasis is placed on a person’s perceived teaching abilities. The construct of values in this model consists of “intrinsic value,” “personal utility value” (i.e., job security, time for family, job transferability), and “social utility value” (i.e., shaping the future of children/adolescents, enhancing social equality, and so on). Negative motivation is also assessed and revealed by the statements describing the fallback career position (Watt and Richardson, 2007).

Research indicates that career transitions are associated with challenges of resistance and adaptation (McMahon and Abkhezr, 2025). One of the universal challenges of CCTs in different cultural contexts is the difficulty of managing classrooms and teaching pupils (Dadvand et al., 2024; Shwartz and Dori, 2020; Troesch and Bauer, 2020). Without adequate support, CCTs, especially in hard-to-staff schools, experience significant practice shock, which brings back the issue of teacher shortage (Troesch and Bauer, 2020). Secondly, according to the novice-expert theory, CCTs are “experienced novices” with a dual identity – that of their previous profession and that of their new profession as teachers (Dadvand et al., 2024; Troesch and Bauer, 2020; White et al., 2024). They need recognition for their extensive experience but also support in developing their new identity and competencies as teachers, as they often construct their teaching careers independently and face additional qualification requirements, mastering teaching skills and developing a holistic, empathic approach (Aslan and Eröz, 2025). Without adequate support, CCTs, especially in hard-to-staff schools, experience significant practice shock, which brings back the issue of teacher shortage (Troesch and Bauer, 2020).

In Lithuania, teacher qualifications can be obtained at universities and colleges through parallel, sequential, or concurrent studies (Eurydice, 2025). Teacher training programs are provided by teacher training centeres and higher education institutions. There are various alternative ways to become a teacher. One of them is that a person who already has a higher education degree can participate in a teacher training program. Paradoxically, although a special evaluation committee assesses the motivation of students applying to pedagogy programs at universities and colleges (Eurydice, 2025), the prevailing opinion in Lithuania is that teaching programs are chosen mainly by unmotivated students who lack strong academic backgrounds (Gruodyte and Pasvenskiene, 2013). A teaching career begins with the first phase of pedagogical interns’ status, which helps inexperienced teachers integrate into the teaching community and receive professional assistance and support. After successfully completing an internship, teachers work independently (Eurydice, 2025).

Although no studies have been found on the relationship between the motives for CCTs’ career choice and the level of prestige in a given country, it is still possible to observe a tendency toward a certain dominance of some motives related to prestige as an aspect of the attractiveness of the teaching profession (Pérez-Díaz and Rodríguez, 2014; Fico, 2024; Gorard et al., 2024).

In countries where the prestige of the teaching profession is relatively high due to public trust and respect for the professionalism of teachers, decent salaries, and so on (Barron et al., 2023; Frison et al., 2023), as in Finland, Ireland, Bahamas, Malaysia, Germany, Turkey, the predominant motivation for CCTs was a long-held dream to become a teacher, the influence of family members who had also been teachers, positive previous teaching and learning experiences and loss of a job, lack of interest in a previous job (Geoghegan, 2023; Kavanagh, 2024). Research has also shown that intrinsic value and self-perceived pedagogical ability were the most important factors in the transition to teaching, followed by social benefit values, such as shaping the future of children and adolescents or making a social contribution. Family time and social influence motives were the least important factors (Fray and Gore, 2018; Lucksnat et al., 2022). Similar motives for choosing to teach have been revealed by other studies (Zuzovsky and Donitsa-Schmidt, 2014; Koç, 2019): changing careers to teaching in search of spiritual satisfaction, balance between work and other life roles, job security, wanting to have a career that is in line with one’s personal values, and a sense of disappointment with one’s previous career.

In Lithuania, there is an ongoing debate about the teaching profession lacking prestige due to several factors. Since the perception of prestige stems from various sources, the image of teachers portrayed in the media influences how they perceive the significance of their work, its importance to society, and their ability to make a positive impact on the world (Jung and Heppner, 2017). The image of the Lithuanian teacher communicated in the news media is dual: teachers are shown as role models, taking initiative and acting in the face of challenges, but at the same time, they are portrayed as victims with no hope left (Zdanavičiūtė, 2025). In addition, the teachers’ work prestige is also shaped by the perception of a lack of prestige in the profession among existing teachers, due to the signals sent by their immediate environment (Budreikaitė and Raišienė, 2024). Teaching, a strongly feminized occupation in Lithuania, is not seen as an attractive and worthy career path (Bakonis, 2021; Bilbokaitė and Bilbokaitė-Skiauterienė, 2017). This negative picture is eroding the prestige of the teaching profession despite the national policy goal to make the teaching profession prestigious by 2025.

In countries where the prestige of the teaching profession is low or declining, such as the United States and Lithuania, career changers are motivated to teach because they find it personally rewarding or because it makes them feel effective. These motivations reflected both intrinsic motivations, driven by a passion for the work, and extrinsic motivations, influenced by lifestyle factors, as well as motivating social influences, including former teachers, family background, parents, colleagues, and friends. These social influences inspired altruistic motives to help children and make a difference in the world, while extrinsic motives were perhaps the least frequent (Callahan and Brantlinger, 2023, Mičiulienė and Kovalčikienė, 2023; Tichnor-Wagner et al., 2025), and altruistic motivation dominate the motivation of the study participants from low or declining prestige contexts. However, these findings show that there is a particular lack of research in contexts where the teaching profession has low prestige and low attractiveness, which is why, according to Alvariñas-Villaverde et al. (2022), it is important to focus on improving the selection and training of future teachers, starting with a more profound knowledge and understanding of their motivations for making the transition to a career in teaching. Therefore, it is crucial to comprehend the factors that motivate individuals to transition into teaching in a context of low professional prestige.

3 Materials and methods

The paper conducts a qualitative study with the primary aim of investigating in greater depth the reasons why educated individuals with work experience in other fields choose to pursue teaching careers, despite the low prestige associated with teaching professionals.

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical research standards and approved by the Kaunas University of Technology Research Ethics Committee (No. M6-2024-05). As all participants were adult students (CCT), written consent forms were not required by the approving body. Instead, students were informed in writing about the study’s aim, the voluntary nature of their participation, and the confidentiality of their responses. They indicated their consent by confirming their willingness to have their reflections included in the study via email reply with their name. This pathway was approved by the ethics committee as sufficient documentation of consent, given the low-risk nature of the research and the adult status of participants.

3.1 Participants

The purposive sample consisted of individuals with a higher education in a field other than teaching and enrolled in a 1-year teacher education program at one of the largest Lithuanian universities. Inclusion criteria were: (1) enrollment in the teacher education program and (2) completion of an introductory reflection task. Participation in the study was based on these written reflections, after obtaining the students’ informed consent to have their texts analyzed for research purposes. Six students did not agree to participate. A total of 109 reflections were eligible for analysis. The remainder were coded with the letter ‘T’ and a number to maintain confidentiality.

The sample was not homogeneous in terms of gender, with 102 females and seven males. The sample was diverse in terms of age, with 42 (38%) individuals aged 23–30, 47 (43%) aged 31–40, 16 (15%) aged 41–50, and 4 (4%) aged 51 and above.

All the participants held bachelor’s degrees, some had master’s degrees, and several had a Ph.D. All of them had a non-teaching-related education. Their previous vocations covered more than 50 different fields, including accounting, finance, mathematics, programming, economics, chemical engineering, advertising, architecture, art studies, journalism, political science, philosophy, psychology, medicine, military science, sports, dance, and several other disciplines.

3.2 Data collection and analysis

At the beginning of their studies (first month of the program), all participants were asked to complete a written reflective assignment, submitted online through the university’s learning platform. The prompt was: Please write a reflection on your career pathway and your motives for choosing teaching as a profession.’ No minimum requirement was imposed; however, students were advised to provide a thoughtful and detailed narrative. The resulting reflections ranged in length from approximately 730–2,400 words, providing rich material for qualitative analysis. Given the relatively large sample size for qualitative research, thematic saturation was not the primary principle guiding data collection; instead, all reflections were included to ensure comprehensive coverage of the sample. During the analytic process, we monitored the emergence of new themes and found that patterns recurred across participants, suggesting that the dataset was sufficiently rich for in-depth reflexive thematic analysis.

The completeness, depth, and diversity of the responses led the present researchers to assume that the CCTs had openly expressed their opinions and were based on their unique experiences, thereby generating a detailed picture of the development of their motivation for choosing a teaching career. The research participants wrote their answers in their mother tongue, Lithuanian. All selected quotes were translated from Lithuanian into English with the help of translators/interpreters. To ensure accuracy and preserve the meaning of participants’ expressions, translations were checked through peer review by a second researcher familiar with the study context. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved collaboratively. No formal back-translation was conducted, as the peer review process ensured conceptual equivalence and clarity for an international readership.

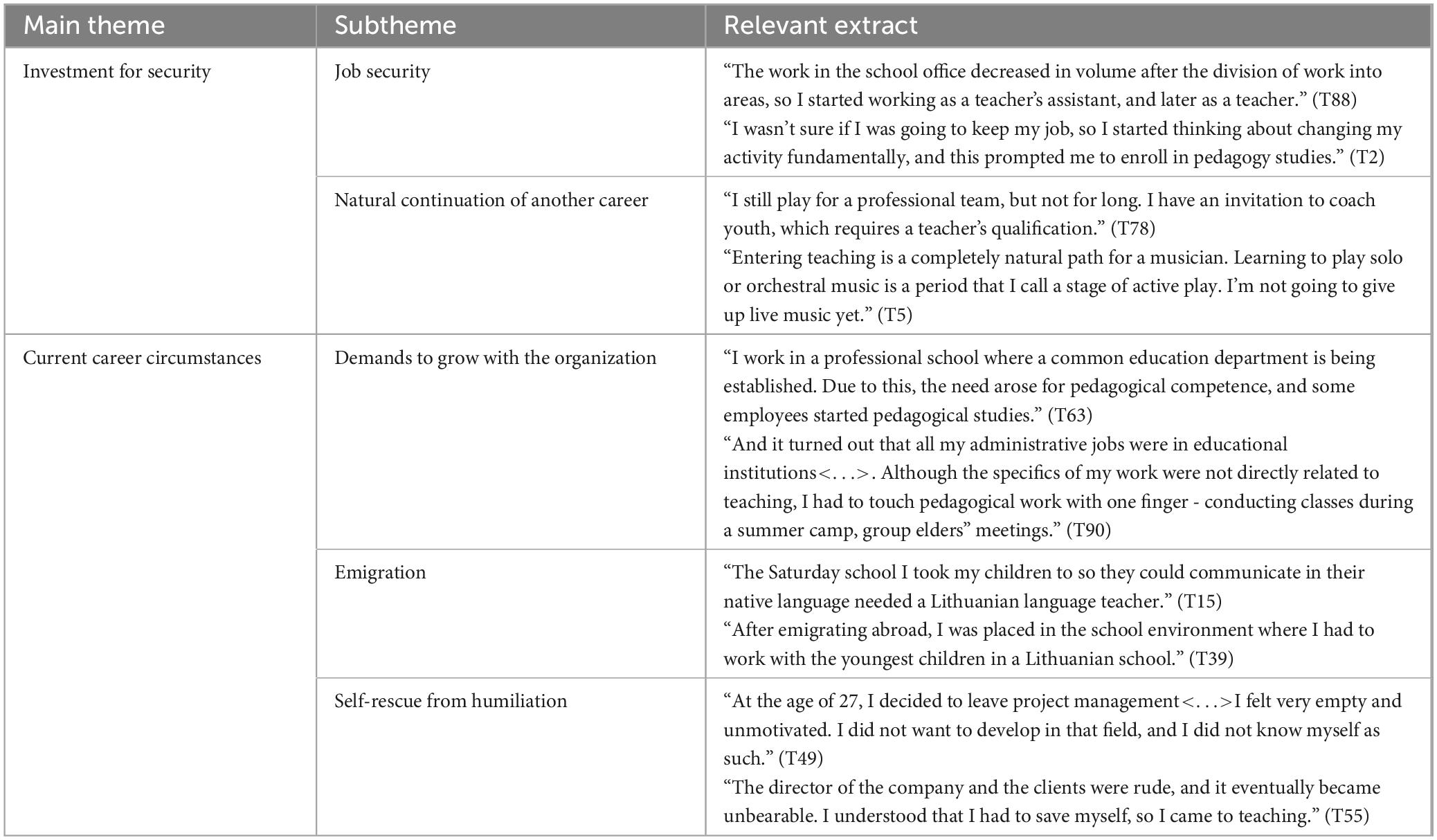

The data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2021). The first author conducted the initial coding and developed candidate themes, engaging in ongoing reflexive reflection to consider how her position as a teacher educator shaped her interpretations. The analytic process was iterative: codes were generated inductively from the data, clustered into patterns of meaning, and gradually developed into themes through repeated reading, writing, and discussion. An audit trail was maintained through analytic memos and documented theme revisions, ensuring transparency in the decision-making process. Final themes were refined through reflexive dialogue among the researchers rather than through coder agreement. Table 1 presents themes, subthemes, and illustrative quotes to demonstrate the analytic process.

The initial themes and sub-themes were revised in accordance with the research question of why participants chose to change their occupations and become teachers at that time. The description of the analysis aims to convey to the reader the participant’s experience through direct quotations. During the mapping phase, the researchers discussed and selected a visual solution that would best reflect the participants’ motives.

4 Results

Based on a qualitative thematic analysis, two groups of themes related to the motives for choosing the teaching profession were identified: extrinsic motivations and intrinsic motivations, including altruistic motivations.

4.1 Extrinsic motivation for choosing a turn to a teaching career

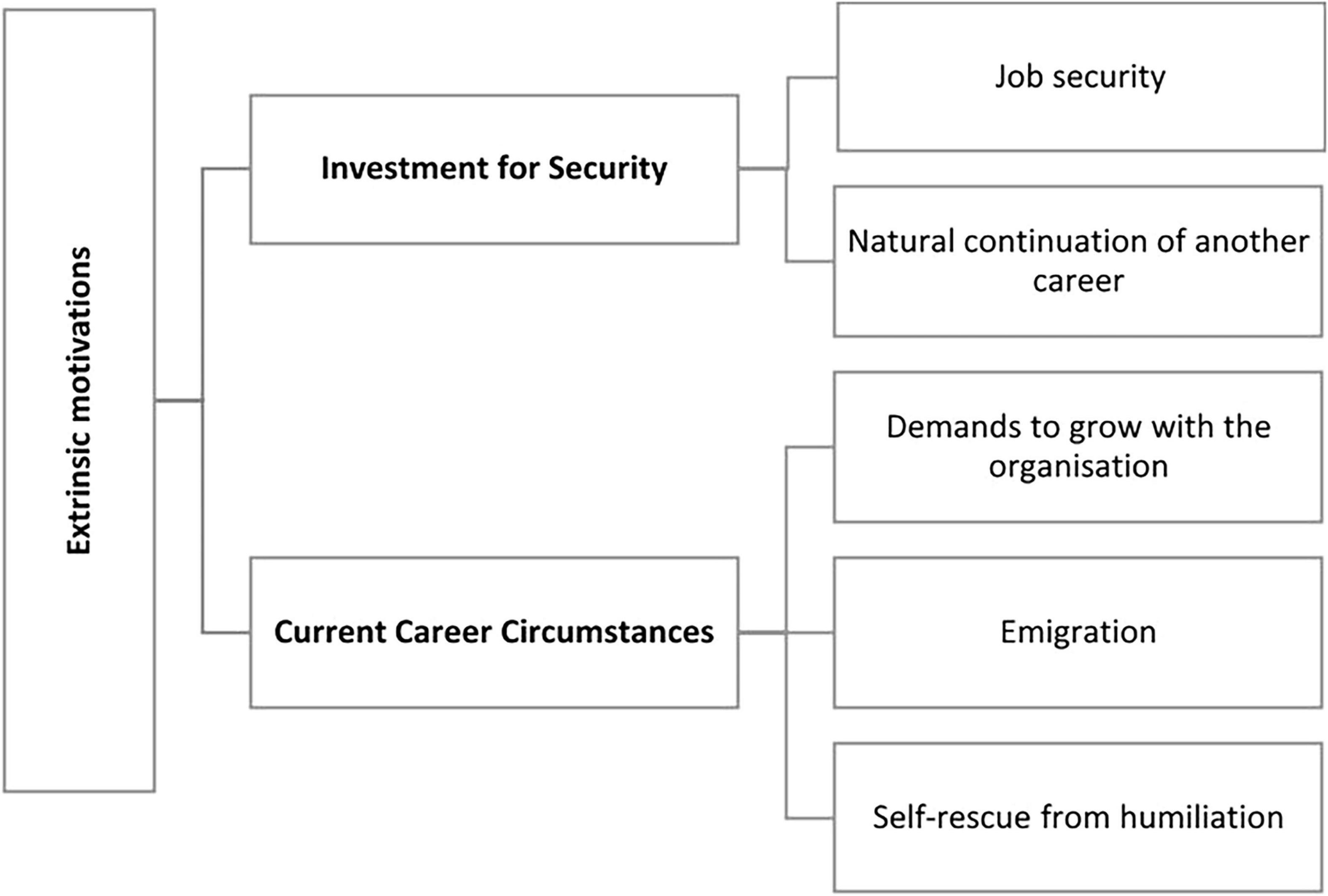

Extrinsic motives originate from the environment, including changes in the labor market and career circumstances (Ryan and Deci, 2020). In this group of motives, the following themes were identified: “Investment for security” and “Current career circumstances” (Figure 1).

4.1.1 Investment for security

The theme “Investment for security” indicated that the participants took a pragmatic approach to their potential teaching careers, basing their decisions on life circumstances and the need for financial security and stability. Regarding the subtheme “Job security,” the responses suggested that the participants chose pedagogy studies simply to maintain an existing position or to obtain a new one at the same or a different educational institution: “Changes awaited a reduction in dietitian positions (where one specialist is assigned to four preschool education institutions) and completely different working conditions. I wasn’t sure if I would keep my job, so I started thinking about fundamentally changing my activity, which prompted me to enroll in pedagogy studies” (T2).

The subtheme “Natural continuation of another career” was also associated with career security. The participants found it quite natural to deviate from the standard career trajectory of a professional musician, dancer, or athlete. A teaching career here was referred to as Option B, better than nothing and the like: “Entering teaching is a completely natural path for a musician. Learning to play solo or orchestral music is a stage I refer to as a period of active play. I’m not going to give up live music yet, but I’m well aware that, just like in sports, in music, you need to get off the stage in good time” (T5). Moreover, the knowledge and experience gained in such fields can be beneficial in other areas, including teaching.

4.1.2 Current career circumstances

The theme, “Current career circumstances,” revealed three subthemes: “Demands to grow with the organization,” “Emigration,” and “Self-rescue from humiliation.” These were motivated by the external circumstances of some of participants’ current work situations, eventually causing them to move into teaching. The first subtheme referred to a situation where organizational change and professional development required pedagogical competence. The development of the educational organization was one such example: “I work in a professional school where a common education department is being established. Due to this, the need arose for pedagogical competence, and some employees started pedagogical studies” (T63).

Moving with one’s family to another country disrupted the normal flow of work for some participants, affecting not only the process of establishing oneself in a new community but also finding a new career. The second sub-theme, “Emigration,” showed that family movement to another country and shared cultural values led to a turn to teaching for at least one participant: “On Saturdays, we drive our children to a Lithuanian school so that they can improve their mother tongue and learn more about Lithuanian culture and traditions. I didn’t even notice how I joined educational activities because here, where we live, only a limited number can teach in Lithuanian” (T50); “after emigrating abroad, I was placed in the school environment where I had to work with the youngest children in a Lithuanian school” (T39).

The last subtheme, “Self-rescuing from humiliation,” drew our attention to the adverse circumstances of some participants’ previous work, which prompted them to change careers to avoid further embarrassment. As one participant noted, “Tension and stress were constantly present when I worked at the building company.” As a woman architect, “I experienced discrimination. The director of the company and the clients were rude, and it eventually became unbearable. I understood that I had to save myself, so I came to teaching” (T55). Indeed, previous studies have shown that changes in circumstances or work trauma (e.g., Savickas, 2020) can lead individuals to devise an exit strategy.

4.2 Intrinsic motivations

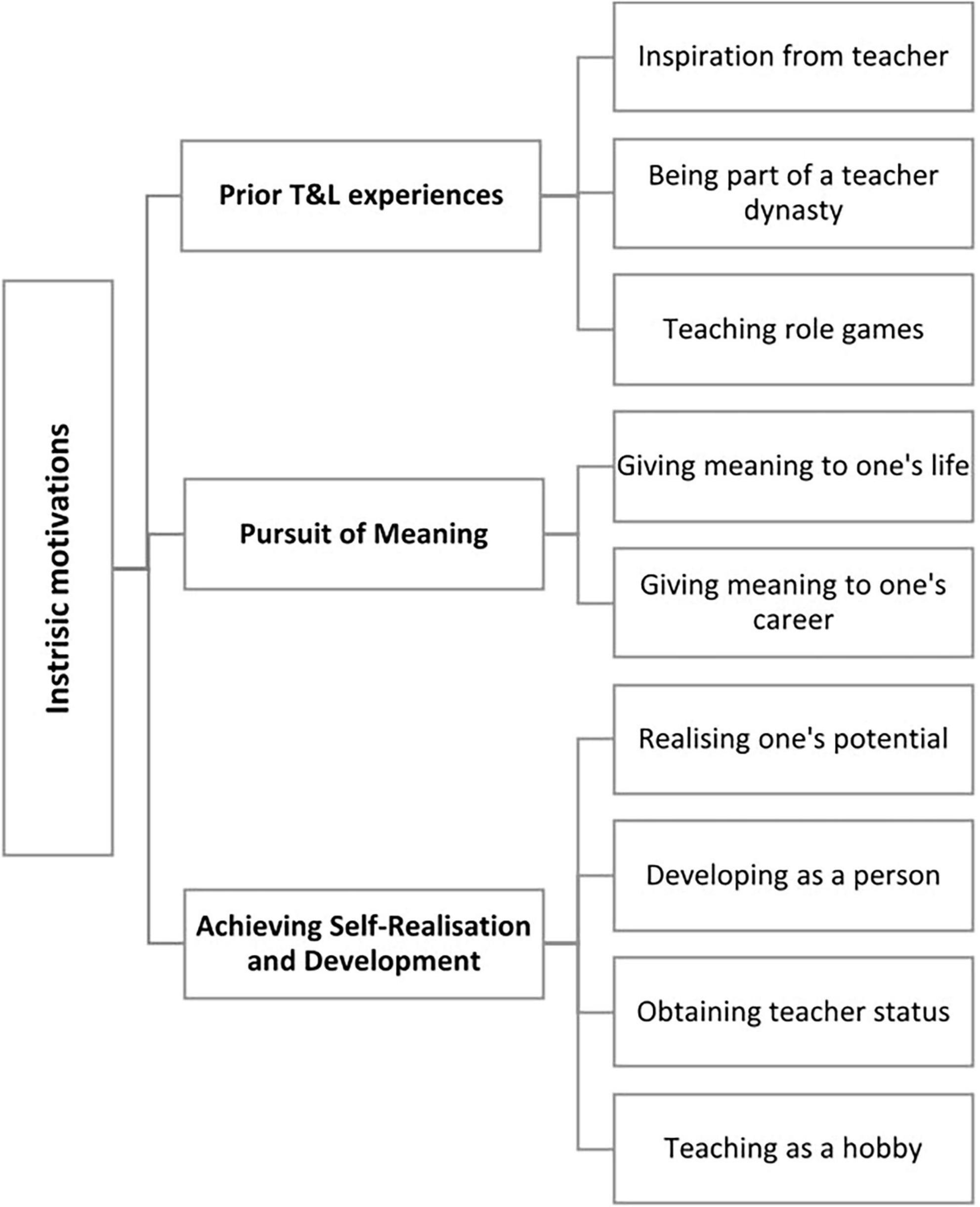

Intrinsic motives stem from a person’s values, characteristics, experiences, and expectations (Ryan and Deci, 2020). Within this group, the following themes were identified: “Prior T&L experiences,” “Pursuit of meaning,” and “Achieving self-realization and development” (Figure 2).

4.2.1 Prior T&L experiences

The first theme, “Prior T&L experiences,” connects three subthemes: “Inspiration from teacher,” “Being part of a teacher dynasty,” and “Teaching role games.” Regarding the former, the participants wrote about their teachers and their influence on the formation of their personality and professional identity; for instance, “I wanted to become a primary school teacher because I had a wonderful teacher myself.” “Her wide smile, sincerity, friendliness, and the ability to communicate with children still live in my memory” (T31). Teachers of senior classes who were able to interest their students in particular subjects and form a close and positive relationship with them were also mentioned: “I’ve always admired my singing teacher so much. She was, I thought, perfect: talented, cool and confident. After finishing school, I chose to study at the music academy” (T41).

The second subtheme included references to the metaphor of an “inherited career” (Inkson, 2004). The statements in this subtheme highlighted the uniqueness of the teaching profession and the influence of an intimate social environment—namely, the immediate family and relatives—on career choice: “My parents, uncles, aunts, and especially my grandparents, constantly dreamed about me as a child…” “Maybe they saw that my character traits were suited to this job, maybe because it was considered an honorable and prestigious profession 30-odd years ago” (T32). However, several generations of teachers in one family, a factor that in many cases favored the choice of a teaching career, could also work in the opposite way to prove and consolidate their individuality: “But it was time to search for myself… and here the “family career” was no longer satisfying at all” (T35).

The subtheme “Teaching role games” demonstrated their preference for teaching activities, which they described in detail and vividness. T25 wrote that “I really liked dictating to the students, reading fairy tales, analyzing them, and performing various mathematical calculations.” Another wrote, “I often taught my imaginary students, explaining and repeating tasks aloud” (T15). These and similar quotes suggested that the participants had a strong and very early interest in teaching, but they did not emphasize this aspect. Instead, they believed that being a teacher “was the dream of all girls” (T42) or that “all children used to play this way” (T43).

4.2.2 Pursuit of meaning

The theme “Pursuit of meaning” revealed that the participants had a desire to act wisely and not waste their time. Indeed, this was regarded as the principal motive for changing careers. There are two subthemes here: “Giving meaning to one’s career” and “Giving meaning to one’s life.” The first of these referred to the notion that a teaching career was somewhat idealized and presented as being a through-route to giving meaning to one’s life: “I did not feel happy, and I did not want to waste the rest of my life on insignificant things, I wanted to make myself meaningful somehow, to bring universal benefit. Working in a school and with children fills me with the hope that I can contribute to their education and increase their awareness. It seems that communicating with me motivates them to try harder and become better students… and so far, I feel happy doing it” (T10). In another subtheme, greater emphasis was placed on personal position and the value derived from teaching: “My career is focused primarily on the experience of a meaningful life, on the desire to “harvest every day” (carpe diem), on the desire to know myself and follow my own path. This is why, “I changed my profession and my place of residence. Additionally, my intended career is closely related to my abilities and developed competencies, that is, what I do best and what I am able to study most intensively to excel in” (T12).

4.2.3 Achieving self-realization and development

Under the theme “Achieving self-realization and development,” the participants were pleased to discover that pedagogical activities enabled them to maximize their potential, leverage their strengths, and make progress. Four subthemes emerged: “Realizing yourself best,” “Developing as a person,” “Obtaining teacher status,” and “Teaching as a hobby.” The first of these included statements that emphasized the opportunities that teaching allowed the participants to apply their competencies and personal qualities: “I realized that the activities were much more interesting and meaningful for me, and they consisted of pedagogical rather than therapeutic activities. So, after realizing this, I stopped my master’s studies in art therapy, enrolled in a master’s program in painting, and chose my current course” (T8); “I started systematically reading lectures on the topic of preparing sports cars.” “I realized two things: that I had something to say, and I liked to say it” (T39).

As part of the subtheme “Developing as a person,” the participants described the significance of personal growth and personality change in the teaching context: “I couldn’t begin to count the number of discoveries I made while working as a teacher. Having been naive and rather narcissistic, I became much more responsible. For the first time in my life, I experienced what it means to immerse myself in the process. I learned to give, and I felt that by giving, I received even more in return” (T11); “Being a teacher frees creativity – every lesson, I create something new” (T21); “It strengthens my self-esteem and gives me self-confidence, and it gives me a lot of confidence.” “I don’t consider it a job, more a way of life” (T10); “It teaches me responsibility – I grew up with problems, but I accepted that I am responsible for their [the pupils’] knowledge and, in some sense, their future” (T41).

We identified several statements that we decided to code under the subtheme “Obtaining teacher status.” Here, some participants spoke about rejection. They explained that a teacher’s career is a means of self-affirmation, of being able to prove the legitimacy of one’s voice: “Because of the great shortage and need for school leaders in Lithuania in recent years, I plan to use my legal and pedagogical experience as a school leader in the future” (T91); “I will have the opportunity to join associations, to express my views during meetings on all the issues being discussed” (T71). It seemed that this was a revelation after the struggle to overcome one’s or others’ stereotypes: “Though neither positive nor negative experiences at school drove me to become a teacher. A job that doesn’t require mental work. I wanted a challenge, something interesting, engaging, enchanting. And then I realized: that’s what working with children is all about!” (T86).

Other participants described a joy in teaching that we grouped under the subtheme “Teaching as a hobby.” For T105, the feeling experienced when standing in front of the students was indescribable: “It felt as if I remembered a favorite long-forgotten song… I am continuing my career as a chemistry scientist, and one or two days a week, I will be working in a school. It is like a hobby to me.” Self-realization and development as a CCT gave her a feeling of joy and satisfaction.

4.3 Altruistic motivations

Altruistic motives are intrinsic motivations related to social value, which enhance the wellbeing of others and serve the greater good of society. In this group, the following themes were identified: “Being useful” and “Commitment to improving the world” (Figure 3).

4.3.1 Being useful

The theme “Being useful” indicates that participants are focused on enhancing the wellbeing of others, concerned about the public interest, and willing to share their resources selflessly. Three subthemes emerged: “Helping others,” “Making social contribution,” and “Sharing own academic knowledge.” The subtheme “Helping others” revealed that the participants were already orientated toward supporting others and caring for weaker peers and other living beings in their childhood: “Even as a child, I dreamed of becoming a veterinarian, but I imagined that teaching activity is very beautiful and more “caring” than the work of a veterinarian. In the long run, this desire coincided with the knowledge that I could take care of the weaker than myself, and it made me happy” (T14). The latter participant was aware of the universality of her inclination to help others and how it could be applied to her teaching activities. This inclination was a sign to some that they should teach: “Both at school and at university, I was the first to help a classmate and explain tasks or a topic and this gave me great pleasure” (T27).

The subtheme “Making social contribution” comprised statements in which the participants expressed the desire to benefit others by engaging in the activities they preferred, especially with children and young people: “I chose pedagogy studies very thoughtfully and purposefully; I had a mission to educate and accompany young people in their choices through the activities that were interesting to me, namely, cooking and handicrafts” (T15).

The subtheme “Sharing own academic knowledge” summarized the participants’ commitment to self-as-expert-efficacy. As one respondent explained, “It is important to show students that exact formulas are used in drawing houses and bridges. As I used to be an architect, I can do that” (T92). The statements relating to the theme “Pursuit of meaning” provided evidence that meaningful activities brought great satisfaction to the participants.

4.3.2 Commitment to improving the world

The theme, “Commitment to improving the world,” referred to the participants’ desire to change their situation at school and the vision they had for the schools of the future; these were the reasons why they decided to pursue a career in teaching. There were two subthemes: “Shaping future of children” and “Making the world a better place.”

Under the first of these subthemes, the participants expressed a personal interest in reforming education in Lithuania, particularly in providing schoolchildren with a better future. In the words of one participant: “While I was studying abroad, I had many good ideas on how to change the structure of lessons, the microclimate of the classroom, and attitudes toward students. I always wanted to implement my new ideas and changes in the school. Because my children are currently at school, I actively participate in their learning” (T7).

The subtheme “Making the world a better place” comprised expressions of desire and a determination to work for a better future for everyone: “I want to work purposefully with a class, to raise people who understand and appreciate culture and who are able to think independently and critically” (T14); and another CCT shared: “I’m excited about being given the opportunity to work as part of a great team with a shared idea of improving community life through education and training” (T29).

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Discussion

The study examines career changers in a national context where the teaching profession has low prestige. We aimed to identify the motives that encourage individuals to change careers and transition into teaching in a context of low professional prestige. Our findings align with prior studies that show continuity between previous careers and teaching. In this Lithuanian context, the continuity appears more pronounced because many participants drew on domain expertise from arts and sports. We view this as a context-specific emphasis rather than a new category. As previous studies have shown, this motive is related to the question of teacher identity. The possibility of reconciling a new teaching career with a previous career strengthens CCTs confidence (Aslan and Eröz, 2025; Bar-Tal and Gilat, 2019; Dadvand et al., 2024; Hogg et al., 2023). The second alignment with previous CCT studies (e.g., Troesch and Bauer, 2020) was represented in the group of motives we categorized as “Commitment to improving the world.” These were ambitions inspired by the desire to contribute to the improvement of education while not being fearful of its shortcomings. In some studies of a country where the teaching profession has low prestige (Mičiulienė and Kovalčikienė, 2023), the idea of improving the education system has been linked to the altruistic values of teachers. In contrast, the present instance was more proactive, as it altered one’s career trajectory. The third finding was a new group of motives: “Current career circumstances” (i.e., “Demands to grow with the organization,” “Emigration,” and “Self-rescue from humiliation”), which seem to have arisen in an attempt to adapt to the complex conditions of a modern career (Savickas, 2020). A person chooses to become a teacher to grow with an organization and to preserve their and their children’s cultural identity in the context of migration. The preparation and attitude, abilities, and actions that are necessary to pursue the most suitable type of work and perform current and planned career development tasks highlighted the career adaptability and psychological resources for managing career change, new duties (tasks), and work traumas (Savickas, 2020; Del Corso, 2015) at critical points in their lives (Watters and Diezmann, 2015) that the CCTs possessed. This shows that external circumstances and stimuli become internal motivations, as noted in previous studies (Siostrom et al., 2023). This shows that external circumstances and stimuli become internal motivations, as noted in previous studies (Siostrom et al., 2023), that intrinsic, extrinsic, and altruistic motivations should not be viewed as entirely separate categories, but rather as intersecting and sometimes overlapping aspects. Indeed, several themes we identified, such as participants’ desire to “Give meaning to one’s career” (intrinsic) while seeking “Self-rescue from humiliation” (extrinsic), illustrate this variability. Similarly, altruistic motivations were often intertwined with intrinsic satisfaction, for example, when participants reported feeling personal satisfaction specifically from helping others (Hogg et al., 2023).

The motives behind the CCT’s decision to become a teacher reflected the influence of the social context and the participants’ internal needs. The findings of the present study confirmed some previous research (Watt and Richardson, 2012; Laming and Horne, 2013; Siostrom et al., 2023) regarding internal values, specifically the pursuit of self-realization and the desire to contribute to societal improvement. Moreover, the participants, when reflecting on their decision to choose a turn to teaching, revealed how they thought about their new profession. Some of them viewed it as an attractive career based on their memory of childhood games, while others knew that it would only become attractive when they had acquired some experience; this would not only change the way they assessed the barriers but also give them an insight into the extent to which those barriers had disappeared, or at least had diminished, had become surmountable, or perhaps had equipped them with the resources to complete their journey. The roots of their decision often lie in childhood, for example, in their positive experiences with games and learning. The metaphor of an inherited career (Inkson, 2004) revealed the sometimes-significant role of the family’s (acceptable, established) career model and financial and educational opportunities. This metaphor highlights the influence of social class and ethnicity on family or kinship values. Several generations of teachers in one’s family reinforced the decision to choose a teaching career, despite the public perception of the profession as unattractive. The intimate environment in which the personality grows and develops can have a great influence, along with a positive teaching role model.

The pursuit of career security and stability was a significant motivator for choosing a career in teaching. For example, the optimization of school networks and the need for continually updated qualification requirements for educational institution employees mean that, as in other sectors, it is not easy to remain a competitive specialist in one’s field and retain one’s job. Disregarding the prevailing opinion that the work of a teacher is difficult and poorly paid, the participants associated the job with stable income and social guarantees and identified the profession as one that will always be needed: “No matter what happens, people will not go without food, treatment, and education. Artificial intelligence cannot replace real, live contact” (T34). On the other hand, some of the participants were professionals (e.g., athletes and performers) who sought to acquire a teaching certificate because it would give them a chance to work in the same field after going beyond their professional career stage and using their previous professional expertise as transfer or adaptive expertise (den Hertog et al., 2023). However, none of the participants who discussed teaching as a guarantor of financial security referred to it as a “backup career,” namely, an option for those unable to pursue prestigious and financially rewarding occupations (Richardson et al., 2014; Imanuel-Noy and Schatz-Oppenheimer, 2023; Siostrom et al., 2023).

The motivation to choose teaching due to its potential for wide social impact confirmed Schein’s (1990) theory of career anchors, one of which is ‘service/dedication to a cause.’ As T37 noted, “Teaching is a meaningful and significant activity for me.” “I feel good at school; it’s nice to see students show an interest in chemistry and to hear that I helped them understand or learn.” The juxtaposition, even identification, of the meaning of life and usefulness to society revealed the values of those who had chosen teaching as a career and their profound and sincere sense of engagement (Wilkins and Comber, 2015).

The pursuit of meaning was linked to the metaphor of teaching as a “carrier of meaning,” as described in career construction theory (Savickas, 2020). It also indicated the participant’s level of motivation and dedication (Bauer et al., 2017). Prevailing idealistic motives for choosing a career—to be useful to society, to realize oneself, to create a better school for our children, to make the world a better place, and so on—appeared to suggest that the participants saw teaching as a vocation. It may, therefore, be assumed that those who saw meaning in their work shared a core of values (Stanišauskienė, 2022).

The motive of achieving self-realization and development was associated with a metaphor enunciated by Inkson (2004), whereby the correspondence of a person’s characteristics to a particular field of activity is described as “being in one’s sled,” “finding one’s place in life,” and so on. Moreover, this metaphor is related to professional inclinations, where a strong correlation exists between a person’s interests, abilities, and specific professional attributes. The participants regarded teaching as an opportunity to express their creativity and satisfy this need. It was noticeable that the sense of satisfaction provided by self-realization helped to break down the boundaries between work and leisure. Indeed, the former provided as much pleasure as leisure time: ‘In this job, I am able to fully reveal my creative side, my ability to organize various activities, to raise children. I felt that I could fully realize myself, and work itself became a kind of free time. After graduating in non-pedagogically based studies and realizing that pedagogy was, in fact, the field in which I wanted to work, I enrolled in a teaching course (T6).

Several career change motives can overlap because an individual may assume different roles throughout their life (Watters and Diezmann, 2015). The theory of career construction (Savickas, 2020) emphasizes the intertwining of social roles: for instance, the role of a citizen fosters the development of youth citizenship, along with respect for the homeland and its culture. As in previous studies (Wilkins and Comber, 2015), the role of the mother or father encouraged some of the participants to delve into the theories and practices of education, and this inevitably trapped them in the whirlwind of educational issues: “For years I had been dreaming of a different kind of school, and when life took such an interesting and unlikely turn so the possibility arose of establishing one, I didn’t hesitate for a moment…” And here I am. Discovering the way to a child’s heart, I try to accompany them on their educational journey. The pedagogical path is based on years of experience as a mother, observing children, understanding them, and achieving success in working with adolescents, as well as rebellion against the system (T64). Sometimes, this involvement exceeds the boundaries of the mother’s or father’s role and becomes the primary motivation for choosing a teaching career, i.e., its social utility value (Watt and Richardson, 2007). In every society where the teaching profession lacks prestige, those who have chosen a teaching career often encounter discouragement in the form of low status and a perception that their job is a form of backup occupation. A teacher’s social roles intertwine in a unique pattern of primary and secondary ones, which provide the energy to act, shape career-related decisions, and influence career trajectories (Siostrom et al., 2023). The motives for choosing a teaching career (e.g., the pursuit of meaning, professional and personal development, and personal growth) reveal the drive and inner potential of those who choose to make the leap, making it possible to predict the intense dynamics of their decision (Bar-Tal and Gilat, 2019; Varadharajan and Buchanan, 2021).

5.2 Limitations of the present study

First, we noticed that the participants’ change of career was influenced not by one, but by several motives; therefore, the chosen method of thematic qualitative analysis was insufficient to categorize them and reveal the connections between these motives. The second limitation was the use of reflective writing alone to gather data. We recognize that relying on reflective writing rather than interviews may limit our ability to explore participants’ motivations in real time. As Grigorovicius (2025) notes, online reflective essays provide participants with an excellent opportunity to express their experiences in detail and at their own pace, allowing for introspective insights that may not be apparent during interviews. However, we recognize that the lack of direct follow-up questions may limit the ability to further clarify or explore emerging themes.

The third limitation was that the participants were just starting their careers. It may have been that they had an idealistic view of teaching and had yet to be encumbered by the realities of their chosen path. Moreover, when analyzing the motives for a teaching career, the differences in their teaching experience were not taken into consideration (e.g., in terms of duration; Varadharajan and Buchanan, 2021).

One more limitation worth mentioning stems from the predominance of female participants in our sample (102 out of 109), which reflects the existing link between school level and the feminization of the teaching profession, where women occupy many teaching positions, which is characteristic not only of Lithuania (Kaminskiene and Galkiene, 2024) but also internationally (Kammermeier et al., 2025). Therefore, future research is encouraged to investigate the motives of CCT for transitioning to teaching, considering that gender assignment and expectations may influence perceptions of the suitability of a profession based on gender.

5.3 Practical recommendations

The findings of the present study have several implications. First, in the world of education politics, systemic changes are needed to ensure the recognition of the factors that determine the motives of CCTs (e.g., self-realization, personal development, the pursuit of meaning, and a simple change in career). Previous work knowledge and capabilities should be recognized as transferable competencies (den Hertog et al., 2023) and serve as a basis for lowering the requirements for work experience during their studies. Secondly, the prestige of the teaching profession could be improved through the dissemination of public information, wherein respect for teachers, trust, and the uniqueness of the CCT experience is acknowledged. Although the participants did not refer to any difficulties in registering for pedagogy studies, it should nevertheless be the case that the administrators of teacher training programmes should pay heed to how applicants have arrived at their decision (Williams et al., 2016; Korhonen and Portaankorva-Koivisto, 2021), for instance, their work mindset, personal qualities, career experience, and their professional identity and status.

For career education specialists and career consultants, it would be beneficial to expose adults in various professional fields to the teaching profession as a potential second career choice, emphasizing the positive aspects of a teacher’s vocation, including the competencies and personality qualities required of a teacher. Higher education institutions should create a conducive environment for students who are inclined toward pedagogical activities and allow them to test themselves by working as a teaching assistant, in a club, or acting as a camp leader. Their attention should be drawn to teaching values and the personality traits associated with the profession, and they should be encouraged to self-assess their professional suitability. Career education specialists in schools should strengthen collaboration between teachers and parents at different educational levels, thereby dissuading them from discouraging their offspring from choosing a career in the sector. Meanwhile, the heads of educational institutions should be obligated to provide CCTs with working conditions that enable them to concentrate on building relationships with students, deepening their subject and pedagogical competencies, and presenting opportunities for creativity and self-expression without burdening them with excessive documentation management and similar tasks.

We concur with the notion that the global shortage of teachers renders the need for scientific research on CCTs particularly urgent (Yinon and Orland-Barak, 2017; Hogg et al., 2023), especially from the perspective of teaching quality (Frison et al., 2023). The data in the present study were collected from CCTs’ reflections, but future researchers might undertake in-depth interviews that might yield valuable information on motivating factors, including those that shape the career trajectories of CCTs currently working in schools. A greater understanding of career change can also be a means of encouraging career development and opening up new directions. The ways different motives interact should also be explored further, for instance, how they reinforce individual effects and encourage proactive behaviors when individuals are deciding on distinct career paths.

5.4 Resume

It is hoped that this study will contribute to an understanding of the factors that motivate individuals from outside the education sector to join the teaching profession in contexts where the teaching profession has low prestige. The qualitative research strategy employed here enabled us to identify a range of motives and connect these with individual life stories and diverse learning experiences. Motives often derive from two temporal phases of a person’s development: childhood and the present moment. In Lithuanian context the continuity appears more pronounced because many participants drew on domain expertise. We view this as a context specific emphasis. Some of the motives revealed herein confirmed those unearthed in previous studies. They include internal values, a striving for meaning, the pursuit of self-realization, and the desire to contribute to the improvement of society. The findings also highlighted the need to assess the individual’s career adaptability; for instance, do they possess the necessary psychological resources to cope with changes in career, new duties, unforeseen crises, and so on? Finally, the study has revealed the significance of shared accumulated experience, the desire held by many CCTs to improve education systems, grow together as part of organizations, and, more broadly, preserve one’s own and one’s children’s cultural identity in migration contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kaunas University of Technology (No. M6-2024-05). As the participants were adults, written consent was not required. They were informed in writing about the purpose of the study, voluntary participation, and confidentiality, and gave their consent by responding via email and providing their first and last names. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional requirements, and data management procedures were in line with the requirements of the GDPR. The ethics committee approved this procedure as sufficient documentation for this low-risk study.

Author contributions

AA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VS: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the helpful feedback and suggestions offered by the reviewers.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alvariñas-Villaverde, M., Domínguez-Alonso, J., Pumares-Lavandeira, L., and Portela-Pino, I. (2022). Initial motivations for choosing teaching as a career. Front. Psychol. 13:842557. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842557

Aslan, R., and Eröz, B. (2025). Transferring skills, transforming careers: Examining second career teachers. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 1–10. doi: 10.1057/s41599-025-04357-2

Bakonis, E. (2021). Svarbūs žingsniai didinant mokytojo profesijos prestižą // Important steps to raise the profile of the teaching profession [Important steps to raise the profile of the teaching profession]. Švietimo Problemos Analizë 3:193. Lithuanian.

Barron, P., Cord, L., Cuesta, J., Espinoza, S., Larson, G., and Woolcock, M. (2023). Social sustainability in development: meeting the challenges of the 21st century. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

Bar-Tal, S., and Gilat, I. (2019). Second-career teachers looking in the mirror. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 11, 27–50.

Bar-Tal, S., Chamo, N., Ram, D., Snapir, Z., and Gilat, I. (2020). First steps in a second career: Characteristics of the transition to the teaching profession among novice teachers. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 660–675. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1708895

Bauer, C., Thomas, S., and Sim, C. (2017). Mature age professionals: Factors influencing their decision to make a career change into teaching. Issues Educ. Res. 27, 185–197.

Berger, J. L., and D’Ascoli, Y. (2012). Becoming a VET teacher as a second career: Investigating the determinants of career choice and their relation to perceptions about prior occupation. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 317–341. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2012.700046

Beutel, D., Crosswell, L., and Broadley, T. (2019). Teaching as a ‘take-home’ job: Understanding resilience strategies and resources for career change preservice teachers. Aust. Educ. Res. 46, 607–620. doi: 10.1007/s13384-023-00609-9

Bilbokaitė, R., and Bilbokaitė-Skiauterienė, I. (2017). “Reputation of pedagogues and image of this profession in Lithuania: Political, social and educational aspects,” in ICERI2017 Proceedings (IATED), 3586–3593.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., O’Brien, R., et al. (2011). The effectiveness and retention of teachers with prior career experience. Econ. Educ. Rev. 30, 1229–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.08.004

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

Brookhart, S. M., and Freeman, D. J. (1992). Characteristics of entering teacher candidates. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 37–60. doi: 10.3102/00346543062001037

Budreikaitė, J., and Raišienė, A. G. (2024). Mokytojų reikšmijautos charakteristikos demografinių kintamųjų požiūriu// [Teachers’ significance characteristics in terms of demographic variables]. Pedagogika 156, 119–142. Lithuanian. doi: 10.15823/p.2024.156.6

Bunn, G., and Wake, D. (2015). Motivating factors of nontraditional post-baccalaureate students pursuing initial teacher licensure. Teach. Educ. 50, 47–66. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2014.975304

Callahan, P. C., and Brantlinger, A. (2023). Altruism, jobs, and alternative certification: Mathematics teachers’ reasons for entry and their retention. Educ. Urban Soc. 55, 1089–1119. doi: 10.1177/00131245221110559

Carless, S. A., and Arnup, J. L. (2011). A longitudinal study of the determinants and outcomes of career change. J. Vocat. Behav. 78, 80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.09.002

Coppe, T., Marz, V., and Raemdonck, I. (2023). Second career teachers’ work socialization process in TVET: A mixed-method social network perspective. Teach. Educ. 121, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103914

Craig, C. J., Hill-Jackson, V., and Kwok, A. (2023). Teacher shortages: What are we short of? J. Teach. Educ. 74, 209–213. doi: 10.1177/00224871231166244

Dadvand, B., van Driel, J., Speldewinde, C., and Dawborn-Gundlach, M. (2024). Career change teachers in hard-to-staff schools: Should I stay or leave? Aust. Educ. Res. 51, 481–496. doi: 10.1007/s13384-023-00609-9

Dawborn-Gundlach, M., Dadvand, B., van Driel, J., and Speldewinde, C. (2025). Supporting career-change teachers: Developing resilience and identity. Educ. Res. 67, 135–151. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2025.2459378

De Camargo, C. R., and Whiley, L. A. (2020). The mythologisation of key workers: Occupational prestige gained, sustained. and lost? Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 40, 849–859. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0310

Del Corso, J. (2015). “Work traumas and unanticipated career transitions,” in Exploring New horizons in career counselling: converting challenges into opportunities, eds K. Maree and A. DiFabio (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 189–204. doi: 10.1007/978-94-6300-154-0_11

den Hertog, G., Louws, M., van Rijswijk, M., and van Tartwijk, J. (2023). Utilising previous professional expertise by second-career teachers: Analysing case studies using the lens of transfer and adaptive expertise. Teach. Educ. Res. 133:104290. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104290

Dolton, P., Marcenaro, O., Vries, R., and She, P. (2018). Global teacher status index 2018. London: Varkey Foundation.

Eccles, J. (2009). Who am I and what am I going to do with my life? Personal and collective identities as motivators of action. Educ. Psychol. 44, 78–89. doi: 10.1080/00461520902832368

European Commission, European Education, Culture Executive, Agency, Motiejunaite-Schulmeister, A., De Coster, I., et al. (2021). Teachers in Europe – Careers, development and well-being. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Council. (2020). Council conclusions on European teachers and trainers for the future (2020/C 193/04), 11-19. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52020XG0609(02)&rid=5 (accessed June 9, 2020).

Eurydice (2025). Initial education for teachers working in early childhood and school education – Lithuania. Brussels: European Commission.

Farges, G. (2025). Roughly in the middle. Variations in the subjective social status of teachers in France. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 46, 469–488. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2025.2476697

Fico, M. (2022). “Prestige of the teaching profession: Development of the research tool,” in Teaching & learning for an inclusive, interconnected world. Proceedings of ATEE/IDD/GCTE Conference, 127–143.

Fico, M. (2024). Additional pedagogical education as a prerequisite for entering the profession: Prestige of the teaching profession and self-efficacy. Pedagogika 153, 120–143. doi: 10.15823/p.2024.153.6

Finnish National Agency for Education (2018). Finish teachers and principals in figures. Finland: Finnish National Agency for Education.

Fray, L., and Gore, J. (2018). Why people choose teaching: A scoping review of empirical studies, 2007–2016. Teach. Educ. Res. 75, 153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.009

Friedman, I. A. (2016). Being a teacher: Altruistic and narcissistic expectations of pre-service teachers. Teach. Teach. 22, 625–648. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2016.1158469

Frison, D., Del Gobbo, G., Bresges, A., and Dawkins, V. (2023). Second-Career Teachers: First reflections on non-traditional pathways toward the teaching profession. Form. Insegn. 21, 210–218. doi: 10.7346/-fei-XXI-01-23_26

Geoghegan, A. (2023). Changing career to teaching? The influential factors which motivate Irish career change teachers to choose teaching as a new career. Ir. Educ. Stud. 42, 805–824. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2023.2260809

Gorard, S., Ledger, M., See, B. H., and Morris, R. (2024). What are the key predictors of international teacher shortages? Res. Pap. Educ. 40, 515–542. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2024.2414427

Grigorovicius, M. (2025). Online reflective essays: A guide for qualitative researchers. Int. J. Qual. Methods 24, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/16094069251321256

Gruodyte, E., and Pasvenskiene, A. (2013). The legal status of Lithuanian teachers. Int’l J. Educ. L. Pol’y 9, 89–102.

Hogg, L., Elvira, Q., and Yates, A. (2023). What can teacher educators learn from career-change teachers’ perceptions and experiences: A systematic literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 132:104208. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104208

Hunter-Johnson, Y. O. (2015). Demystifying the mystery of second career teachers’ motivation to teach. Qual. Rep. 20, 1359–1370. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2267

Imanuel-Noy, D., and Schatz-Oppenheimer, O. (2023). Relationships are with people-not with lines of computer code: Changing career from hi-tech to teaching. Aust. J. Career Dev. 32, 69–79. doi: 10.1177/10384162221142367

Inkson, K. (2004). Images of career: Nine key metaphors. J. Vocat. Behav. 65, 96–111. doi: 10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00053-8

Jung, A. K., and Heppner, M. J. (2017). Development and validation of a work mattering scale (WMS). J. Career Assess. 25, 467–483. doi: 10.1177/1069072715599412

Kaminskiene, L., and Galkiene, A. (2024). “Teacher education in Lithuania: Striving for the prestige of the teaching profession or for a stronger agency?,” in The reform of teacher education in the post-soviet space, ed. I. Menter (Milton Park: Routledge), 166–179.

Kammermeier, M., Muckenthaler, M., Weiß, S., and Kiel, E. (2025). Feminization of teaching: Gender and motivational factors of choosing teaching as a career. Front. Educ. 10:1471015. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1471015

Kavanagh, B. (2024). An exploration of the motivations for changing career and the formation of professional teacher identity among second-career teachers working within the FET sector of the city of Dublin ETB. [dissertation]. Dublin: Dublin City University.

Kelchtermans, G., and Ballet, K. (2002). The micropolitics of teacher induction. A narrative-biographical study on teacher socialisation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 18, 105–120. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00053-1

Knell, P. F., and Castro, A. J. (2014). Why people choose to teach in urban schools: The case for a push–pull factor analysis. Educ. Forum 78, 150–163. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2013.878775

Koç, M. H. (2019). Second career teachers: Reasons for career change and adaptation. Cukurova Univ. Fac. Ed. 48, 207–235. doi: 10.14812/cuefd.453434

Korhonen, V., and Portaankorva-Koivisto, P. (2021). Adult learners’ career paths – from IT profession to education within two-year study programme in Finnish university context. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 40, 142–154. doi: 10.1080/02601370.2021.1900939

Laming, M., and Horne, M. (2013). Career change teachers: Pragmatic choice or a vocation postponed? Teach. Teach. 19, 326–343. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2012.754163

Lent, R. W., Lopez, F. G., and Bieschke, K. J. (1993). Predicting mathematics–related choice and success behaviors: Test of an expanded social cognitive model. J. Vocat. Behav. 42, 223–236. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1993.1016

Lucksnat, C., Richter, E., Schipolowski, S., Hoffmann, L., and Richter, D. (2022). How do traditionally and alternatively certified teachers differ? A comparison of their motives for teaching, their well-being, and their intention to stay in the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 117:103784. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103784

Marinell, W. H., and Johnson, S. M. (2014). Midcareer entrants to teaching: Who they are and how they may, or may not, change teaching. Educ. Policy 28, 743–779. doi: 10.1177/0895904813475709

Mayotte, G. A. (2003). Stepping stones to success: Previously developed career competencies and their benefits to career switchers transitioning to teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 19, 681–695. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2003.03.002

McMahon, M., and Abkhezr, P. (2025). Career adaptability and career resilience: a systems perspective. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guidance 1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10775-025-09739-1

Mičiulienė, R., and Kovalčikienė, K. (2023). Motivation to become a vocational teacher as a second career: a mixed method study. Vocat. Learn. 16, 395–419. doi: 10.1007/s12186-023-09321-2

Mockler, N. (2022). No wonder no one wants to be a teacher: world-first study looks at 65,000 news articles about Australian teachers. Melbourne: The Conversation.

Negrea, V. (2024). Exploring career changers’ experiences in a school-based initial teacher education programme for science teachers in England. Int. J. Educ. Res. 125:102342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102342

Nilsson, P., and Cederqvist, A. M. (2025). Building teacher knowledge and identity–career changers′ transition into teaching through a short teacher education programme. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 48, 132–152. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2024.2432406

OECD. (2018). Education at a glance 2018: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing, doi: 10.1787/eag-2018-en

Pérez-Díaz, V., and Rodríguez, J. C. (2014). Teachers’ prestige in Spain: Probing the public’s and the teachers’ contrary views. Eur. J. Educ. 49, 365–377. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12087

Priyadharshini, E., and Robinson-Pant, A. (2003). The attractions of teaching: An investigation into why people change careers to teach. J. Educ. Teach. 29, 95–112. doi: 10.1080/0260747032000092639

Richardson, P. W., Karabenick, S. A., and Watt, H. M. (2014). Teacher motivation. Theory and practice. Hoboken: Routledge.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101860. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Savickas, M. L. (2020). “Career construction theory and counseling model,” in Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work, eds R. W. Lent and S. D. Brown (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 165–200.

Shwartz, G., and Dori, Y. J. (2020). Transition into teaching: Second career teachers’ professional identity. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Tech. Ed. 16:em1891. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/8502

Sinclair, C. (2008). “How can what we know about motivation to teach improve the quality of initial teacher education and its practicum?,” in Motivation and practice for the classroom, eds P. A. Towndrow, C. Koh, and T. H. Soon (Rotterdam: Sense), 37–61. doi: 10.1163/9789087906030_004

Siostrom, E. (2024). Deciding (not) to become a STEM teacher: Career changers’ perspectives on student behaviour, teacher roles, teacher education, and the social value of the profession. Res. Sci. Educ. 55, 709–732. doi: 10.1007/s11165-024-10215-z

Siostrom, E., Mills, R., and Bourke, T. (2023). A scoping review of factors that influence career changers’ motivations and decisions when considering teaching. Teach. Teach. 29, 850–869. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2023.2208051

Smetana, L. K., and Kushki, A. (2021). Exploring career change transitions through a dialogic conceptualization of science teacher identity. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 32, 167–187. doi: 10.1080/1046560X.2020.1802683

Stanišauskienė, V. (2022). Kodël tampama mokytoju? Mokytojo karjeros trajektorijà brėžiantys veiksniai. Mokslo studija. // Why become a teacher? Factors Shaping a Teacher’s Career Trajectory. Research study. Kaunas: Technologija, doi: 10.5755/e01.9786090217740