- 1Ruppin Academic Center, Emek Hefer, Israel

- 2Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel, Emek Yezreel, Northern District, Israel

- 3Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nuremberg, Germany

Introduction: This study explored the contribution of various contact modes of adult children with their parents to the children's emotional closeness with parents and to the children's life satisfaction.

Methods: Students at colleges and universities in Israel (N = 557) and in Germany (N = 535) were recruited during 2010-2011 and 2013-2014, respectively, through convenience sampling and completed web-based questionnaires reporting on the frequency of each contact mode with their parents (phone, in-person, and digital), their emotional closeness with their parents and their own satisfaction with life. Structural equation models tested the associations between the study variables among the Israeli and German samples while comparing them across the samples.

Results: The results in both samples showed positive associations between the adult children's phone contact and emotional closeness with both parents and between in-person contact and emotional closeness with fathers. Among both samples, phone contact emerged as the strongest contributor to higher emotional closeness. Digital contact was associated with higher emotional closeness with both parents in the German sample only. Emotional closeness with either parent was associated with adult children's higher life satisfaction in both countries.

Discussion: During the pre-COVID-19 era, in both Germany and Israel, direct and synchronous vocal communication contributed to intergenerational connections and wellbeing.

Introduction

The importance of contact between adult children and their parents to the children's wellbeing is well established among young adults (Fingerman et al., 2020). Indeed, young adulthood is an important developmental period where one's well-being is dependent on both acquisition of independence and supportive relatedness to parents (Cohrdes et al., 2023), marking this life stage as an interesting venture point to explore differential modes of contact with parents and their implications for the wellbeing of young adults. However, the differential significance of various contact modes with parents to the wellbeing of adult children in young adulthood has not been sufficiently addressed. The current study aimed to fill this gap while examining the contribution of various contact modes between adult children and their parents (phone, in-person, or digital) to the children's emotional closeness to parents and to their life satisfaction. The strength of this study is that it includes the collection of cross-cultural data gathered from adult children from both Israel and Germany. Israel is a relatively young country that features a unique blend of traditional Jewish family values and norms alongside modern features (Bar-Tur et al., 2018). Israel has the highest fertility rate per-woman among the OECD countries (OECD, 2019). Germany is an older, more secular society with nearly one-third of German citizens reporting no religious affiliation, and is among the lowest fertility-rate-countries in the OECD countries (OECD, 2019).

Adult children's relationships with their parents are among the most crucial relationships for life-long emotional bonds (Fingerman et al., 2020; Martinez-Escudero et al., 2020; Merz et al., 2008; Suitor et al., 2022). Modern technology provides communication tools that enable more social interaction than in past years, allowing adult children to choose how to connect with their parents. The increase in contact frequency also reflects changes in social and family trends that highlight greater connectedness and more frequent communication (Fingerman et al., 2020). Geographical proximity has thus become a less crucial factor in sustaining emotional closeness between adult children and their parents. Frequency and modes of contact may vary according to needs, characteristics, and relationship quality (Chaie et al., 2020). Differences in communication modes may be linked to differences in the affective qualities of the relationship between adult children and their parents, which may be positive, ambivalent, or conflicted. It follows that frequent contact between adult children and their parents can be expected to impact their respective moods and stress levels (Birditt et al., 2017; Fingerman et al., 2012, 2020).

Today's contact rates between adult children and their parents are high compared to past years. Modes of contact can be in person, by telephone, or by text (Fingerman et al., 2016b, 2020). Findings from the Health, Aging, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) survey revealed that nearly 80% of adult children living apart from their parents have at least a weekly contact with them, and more than two thirds have several weekly contacts (Szydlik, 2016). While contact frequency may be associated with greater emotional closeness (Fingerman et al., 2012), some studies found that the frequency of contact in families may not directly reflect emotional closeness (Fingerman et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2012; Van Gaalen and Dykstra, 2006). These mixed findings may be explained by parents' and adult children's individual differences, relationship quality, and their respective inclinations to use specific modes of contact (Chaie et al., 2020; Norris et al., 2003).

Students report more frequent contact and greater involvement with their parents than non-students of a similar age. Moreover, students are also more likely to speak with parents by telephone and in person than non-students and receive more emotional support from their parents than do non-students, thus contributing to their life satisfaction (Fingerman et al., 2012). Telephone contact may supplement and compensate for less frequent in-person contact when students live far from their parents (Attias-Donfut and Wolff, 2000; Fingerman et al., 2012, 2016b).

Students who reported more frequent telephone conversations with their parents also reported more satisfying, intimate, and supportive relationships with them (Gentzler et al., 2011). In contrast, students who reported more frequent technology-based communication with their parents reported higher levels of loneliness and attachment anxiety (Ramsey et al., 2013).

Research on the association between the type of communication technology and the nature of the personal relationship indicated that communication methods that included both verbal and non-verbal cues (in-person contact as well as telephone and video calls) were positively associated with higher overall relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction (Goodman-Deane et al., 2016). Conversely, contact methods offering fewer cues, such as text messaging, were negatively associated with both relationship satisfaction and life satisfaction (Goodman-Deane et al., 2016). However, studies examining the impact of communication technologies on wellbeing revealed mixed findings, such that some studies suggested that technology use was associated positively with wellbeing and relationship quality (Grieve et al., 2013; Kraut et al., 2002; Wang and Wang, 2011). It seems, then, that modern technology's effect on individuals' relationship quality and life satisfaction depends on the communication mode, the person's age, and with whom they want to be in contact. People's choices tend to be guided at least partly by assessments of expected value (Kumar and Epley, 2021).

Another study found that telephone-use satisfies the need for companionship, closeness, and care more than other media (Ramirez et al., 2008). Telephone use tends to occur within close relationships such as families, romantic couples, and friends (Jin and Park, 2010; Jin and Pena, 2010; Utz, 2007). A person's voice has been shown to reveal the human-like attributes of interpersonal warmth and intellectual competence that are lacking in digital text communication (Schroeder and Epley, 2015, 2016; Schroeder et al., 2017), In a field experiment, Kumar and Epley (2021) asked participants to reconnect with an old friend via phone or email. Results indicated that voice-based interactions (phone, video chat, and voice chat) were associated with stronger social bonds than text-based interactions (email, text chat), suggesting that the human voice has the potential to evoke a sense of connection with another person and better understanding. Thus, the closer people feel to the person they want to communicate with, the more likely they would choose synchronic, voice-based communication (Kumar and Epley, 2020).

Decisions about how to interact with others were found to be guided partly by the expected outcomes of the interaction: Voice-based calls vs. voiceless text-based messages may have uniquely desirable effects on the quality of the relationship (Kumar and Epley, 2021). Phone calls, thus, could lead to a stronger sense of connection. Moreover, live voice-based interaction enables more responsiveness than text chat and thus, contributes more to one's feeling of connectedness with another person. In the same vein, social vocalizations have been found to release oxytocin in humans (Seltzer et al., 2010). Thus, the human voice may provide a crucial cue for generating the wellbeing that comes from a positive social connection (Kumar and Epley, 2020).

The chosen modes of contact between adult children and their parents as well as their association with the children's relationship quality and wellbeing may, however, vary by age and characteristics of the children and the parents, such as parents' health difficulties and gender (Barca et al., 2014; Chaie et al., 2020; Gilligan et al., 2022). Adult children's contact with their parents may be relatively more important to their wellbeing when they are younger. For example, adolescents encountering a stressful event who called their mothers and heard their mother's voice were calmer and more relaxed than those who texted with their mothers (Seltzer et al., 2012). The same has been reported regarding young adult students (Gentzler et al., 2011).

Synchronic live-voice contact, such as telephone calls, carry certain benefits to relationships: Even when conducted across geographically remote locations, online conversations with parents can offer greater intimacy than face-to-face meetings. Face-to-face encounters may not lead to one-to-one contact. It often involves some activities or other family members thus impeding private conversations between adult children and their parents and therefore may highlight ambivalent aspects of the relationship (Fingerman et al., 2012). Given the noted qualities of telephone contact, we assumed that adult children's frequency of telephone contact with their parents would be associated with greater emotional closeness with parents than in-person and digital contact. We also assumed that ratings by adult children of their emotional closeness with their parents would, in turn, be associated with higher life satisfaction among the adult children. Due to the universal nature of the strong bond between adult children and their parents (e.g., Bar-Tur et al., 2018), we assumed that the association between frequency of contact, emotional closeness, and the adult children's life satisfaction would be similar across the examined samples, i.e., the Israeli and German samples.

The current study examined the hypothesized associations in both Israel and Germany to enhance ecological validity by comparing two countries that represent distinct cultural contexts along the familistic-individualistic spectrum, a dimension that may play a central role in shaping family relations (Bar-Tur et al., 2018; Dykstra and Fokkema, 2011). Building on previous research examining adult children's contact frequency with their parents across Germany, Hong Kong, Korea, and the United States (Fingerman et al., 2016a), the current study aimed to extend this comparison to the Israeli cultural context. Israel, due to its small geographic size, higher fertility rate, and stronger adherence to religious norms, is generally considered as family-oriented society. In such contexts, co-residence or geographical proximity, frequent intergenerational contact, and strong family obligation norms are more common compared to Germany (Bar-Tur et al., 2018; Dykstra and Fokkema, 2011; OECD, 2019). In contrast, Germany is often described as more individualistic or autonomous, characterized by lower fertility rates, weaker adherence to religious affiliation, greater geographical distance between family members, less frequent intergenerational contact, and fewer exchanges of support among families (Bar-Tur et al., 2018; Dykstra and Fokkema, 2011; OECD, 2019).

The present study examined the associations among contact modes with parents, emotional closeness, and the adult children's life satisfaction in German and Israeli student samples, collected during 2010-2011 in Germany and during 2013-2014 in Israel. Although the asymmetry in data collection periods may limit the comparability of the samples, comparing these two samples allowed us to contrast the two different cultural contexts by examining whether the hypothesized associations hold in both family-oriented and individualistic societies. Furthermore, the current study's period (2010-2014) preceded the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent surge in technology use within families, such as the increased adoption of video calls (Nowland et al., 2024). The current examination may therefore serve as a historical baseline for understanding the contribution of relatively stable contact modes, such as phone contact, to young adults' emotional closeness and life satisfaction, in comparison to more time-sensitive practices, such as text messaging and electronic mail.

The study hypotheses

Based on the reviewed studies showing that the frequency of contact between young adults and their parents is related to both emotional closeness and the young adult's wellbeing (Fingerman et al., 2012) and evidence underscoring the particular significance of phone contact, which can supplement and compensate for less frequent in-person contact and provide richer affective exchange and communication cues compared to digital communication (Gentzler et al., 2011; Goodman-Deane et al., 2016; Fingerman et al., 2012, 2016b; Schroeder and Epley, 2015, 2016; Schroeder et al., 2017), we formulated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Frequency of contact mode between adult children and their parents (in-person, phone, or digital) will be associated with emotional closeness with the parents, which, in turn, will be associated with the adult children's reports of higher life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): The associations in H1 will be similar among Israeli and German samples.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): There will be variability between each mode of contact and its respective association with emotional closeness between adult children and their parents, with telephone contact yielding a stronger association with emotional closeness than in-person and digital contact.

Materials and methods

Participants

In Israel, young adults are drafted into compulsory military service between ages 18–21. For most Israelis, post-high school academic training and adult life begin at age 21 and therefore, recruitment of participants included only participants aging 21 years old and above. Given the relatively older Israeli sample and the study focus on young adults, we excluded Israeli and German participants over age 40 (162 Israeli and 32 German participants were excluded), resulting in an overall sample of adult children aged 21-40 consisting of 557 Israelis and 535 Germans. The age range of 21 to 40 years was chosen in accordance with the definition of “emerging adulthood” as a developmental period typically encompassing the college years in Israel and Germany, characterized by identity exploration occurring between the constraints of adolescence and the responsibilities of adulthood (Arnett, 2007). This age range is commonly used in studies examining young adults' relationships with their parents and also accounts for the mandatory military service in Israel that often delays the onset of higher education (e.g., Bar-Tur et al., 2018, 2019; Birditt et al., 2009). In the present samples, the majority of Israeli and German participants (92.1% and 88.0%, respectively) were aged 21-29, with the reminder aged 30-40.

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the two samples. Participants reported the quality of their relationships with their living mother and father, separately. In both samples, most participants had two living parents, and there were more female than male participants, with most reporting that they were single and in good health. The Israeli sample was slightly older and had a higher proportion of females than the German sample. Compared with the German sample, Israeli participants were more likely to live with their parents, to have a partner, to be employed and to be in good health. In both samples, on average, the participants' parents were in their 50s, living with a partner, working, and in good health. The Israeli parents were slightly older, and had a higher likelihood to be working and to be in better health than the German parents. German fathers were more likely to hold an academic degree than the Israeli fathers.

Table 1. Background characteristics of the participants and their parents in the German and Israeli samples.

Measures

Contact with parents

Participants were asked to indicate the frequency of each mode of contact with their mother and father separately: (a) in-person (“how often have you seen your mother/father in person?”), (b) by phone (“how often have you spoken with your mother/father on the telephone?”), and (c) by digital contact (text messaging or electronic mail, “how often have you had contact with your mother/father via electronic mail, instant or text messaging”). This 3-item measure was applied by Fingerman et al. (2012) to assess contact frequency between adult children and their parents and was translated to Hebrew and German by Bar-Tur et al. (2018). Note, that in-person contact among participants who lived with their parents referred to intentional interactions, beyond routine cohabitation. phone contact mode referred to synchronous voice calls without video, with no distinction made between landline, mobile and VoIP (Voice Over Internet Protocol) calls. Voice notes and video calls were not assessed. Each mode of contact was rated on an eight-point scale: less than once a year or not at all (0), once a year (1), a few times a year (6.5), monthly (12), a few times a month (32), weekly (52), a few times a week (188.5), and daily (325). Higher scores indicated greater contact frequency within each mode (in-person, phone, or digital). These scale values follow a recommended adjustment of ordinal to interval scale (Frankel and Dewitt, 1989). The Israeli questionnaire included two items querying for (1) text messaging (2) and electronic mail. To correct the unintended inconsistency between the questionnaires, the mean of the items assessing text messaging and electronic mail was calculated to correspond to the German questionnaire which included a single item referring to both text messaging and electronic mail.

Emotional closeness

Participants were asked to rate the degree of emotional closeness with each of their parents (hereinafter “emotional closeness”) as follows: “Generally, how would you rate the emotional closeness between you and your mother/father?” This single-item measure was adapted from Umberson (1992) social support index and translated to Hebrew and German by Bar-Tur et al. (2018). The question was presented on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (low) to 5 (high; Bar-Tur et al., 2018, 2019). Participants' raw scores were used, with higher scores indicating greater emotional closeness. In the Israeli questionnaire, this item was rated on a 1 to 10 scale. To correct this unintended inconsistency between the questionnaires, the Israeli scale was converted from 1 to 10 to a 1 to 5 scale to correspond to the German scale, such that each two adjacent categories were merged into a single category.

Life satisfaction

Adult children's life satisfaction (hereinafter “life satisfaction”) was assessed as follows: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” The question was presented on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (dissatisfied) to 5 (satisfied) with higher scores indicating greater life satisfaction. This single-item measure was developed to assess life satisfaction as the cognitive component of subjective wellbeing (Diener et al., 2000) and was translated to Hebrew and German by Bar-Tur et al. (2018). In the German questionnaire, this item was rated on a 1 to 10 scale. The German scale was converted from a 1 to 10 to a 1 to 5 scale by the same procedure described above to ensure correspondence with the Israeli scale.

Covariates

The study hypotheses controlled for main socio-demographic variables: age (in years), gender (man/woman), and living with mother, father, or both (yes/no).

Procedure

Students in Germany were recruited during 2010-2011, and students in Israel were recruited during 2013-2014. Although the data collection periods were not synchronous, this contrastive comparison was designed to examine the hypothesized associations across two cultural contexts within the same broader pre-COVID-19 and pre-intensified-technology era (Nowland et al., 2024). All participants were recruited through targeted sampling by approaching college and university students who were requested to distribute the survey to other students such that a snowball sampling procedure was implemented. All participants verified that they were current students, completed web-based questionnaires, and were told that participation is voluntary and anonymous. The questionnaires were translated from English to Hebrew and German by Hebrew or German native speakers fluent in English, respectively. This study received ethical approval by the authors' Institutional Review Boards.

Analytic strategy

To examine the model fit (H1; See Figures 1, 2), two structural equation models were created in Amos (version 23), one for the Israeli sample and one for the German sample. Each model's goodness-of-fit was tested by several indices (Hu and Bentler, 1999). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) index was used with values smaller than 0.09, indicating good fit. The normed fit index (NFI) and the comparative fit index (CFI) were also used with values higher than 0.95, indicating good fit. The controlled variables (age, gender, and living with mother, father, or both) were entered into the models as exogenous variables associated with each contact variable, emotional closeness, and life satisfaction. These variables were controlled for as they differentiated between the two samples and were central to the current study's dependent variables (Bar-Tur et al., 2018). Missing data in AMOS were treated via maximum likelihood estimation imputations.

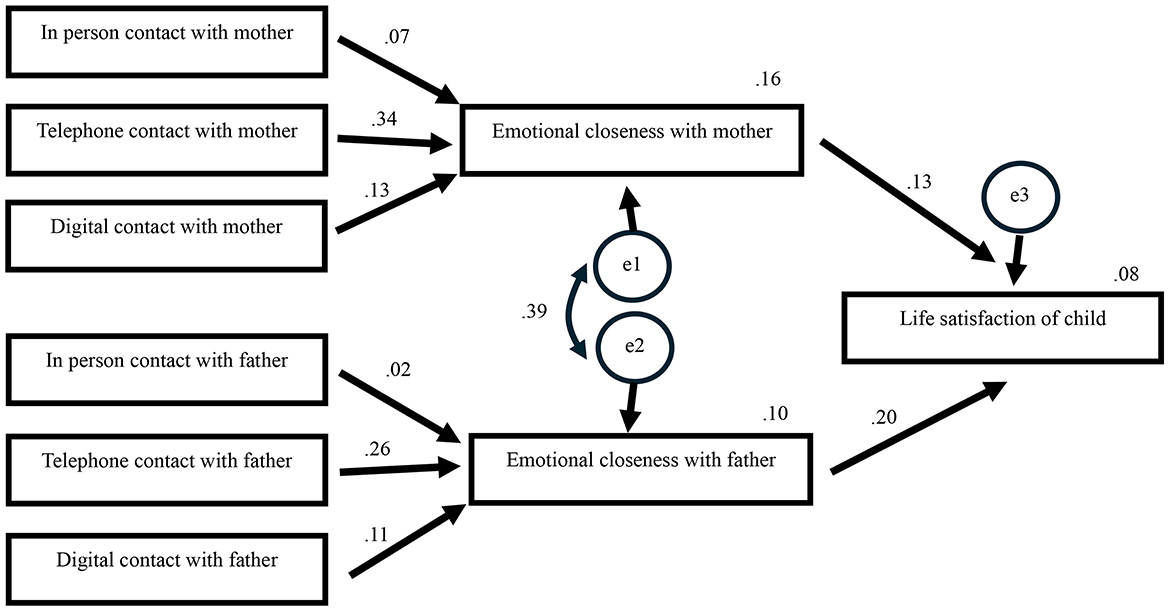

Figure 1. Structural equation model examining the association between modes of contact, emotional closeness with mothers and fathers, and the child's life satisfaction in Israel (N = 557). The model presents standardized regression coefficients (single-headed arrows) and Pearson correlation (dual-headed arrow). The proportion of the explained variance is presented above the dependent variables. The exogenous variables were allowed to correlate. However, these correlations are omitted from the figure for brevity.

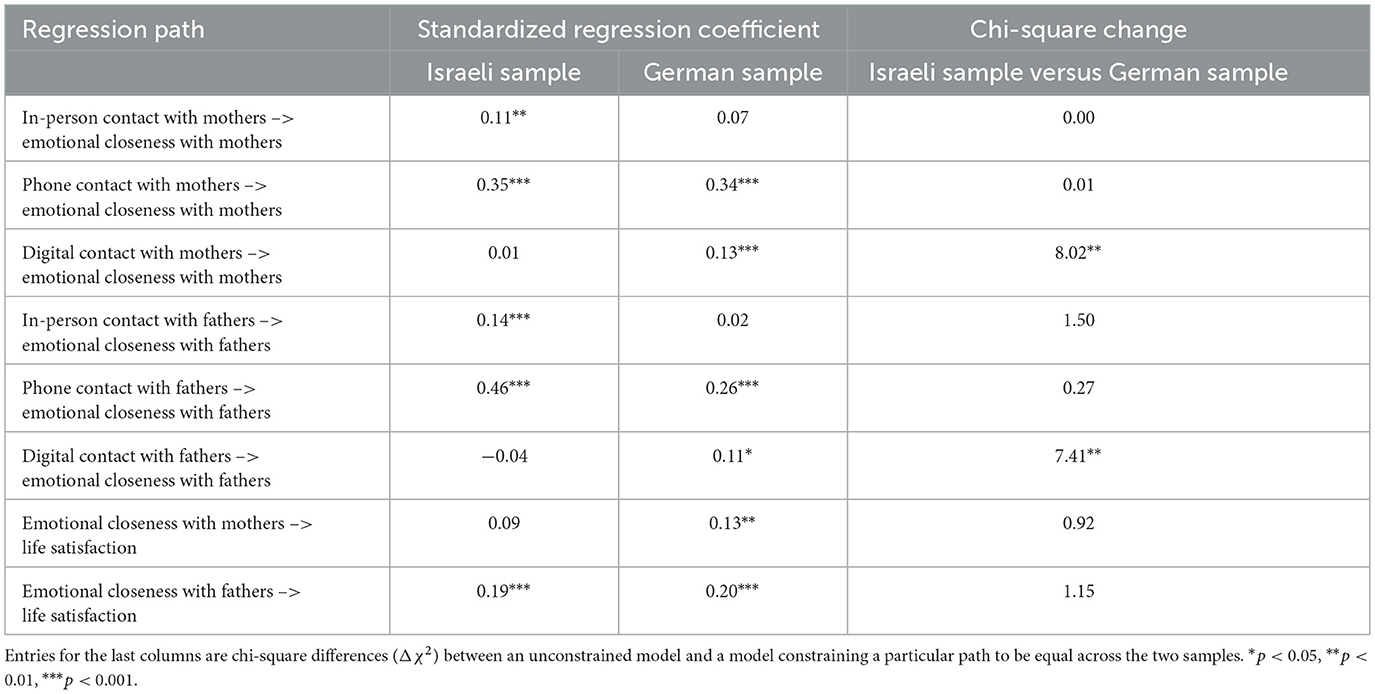

Figure 2. Structural equation model examining the association between modes of contact, emotional closeness with mothers and fathers, and the child's life satisfaction in Germany (N = 535). The model presents standardized regression coefficients (single-headed arrows) and Pearson correlation (dual-headed arrow). The proportion of the explained variance is presented above the dependent variables. The exogenous variables were allowed to correlate. However, these correlations are omitted from the figure for brevity.

To compare the model paths between the Israeli and German samples (H2), differences were calculated between the chi-square goodness-of-fit measures of each model and the equivalent model, fixing this path to be equal across the two samples. A significant chi-square difference means that a particular path significantly differentiates the two samples.

To compare the associations of each mode of contact with emotional closeness in the same model (H3), each pair of paths was constrained to be equal. The chi-square goodness-of-fit measure of the unconstrained model was compared with this measure in the constrained model such that a significant result indicated a difference between the pair of associations. According to common recommendations (Cohen, 1988; Fritz et al., 2012), 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 beta coefficients and 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 Cohen's d coefficients were considered as representing small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.

Results

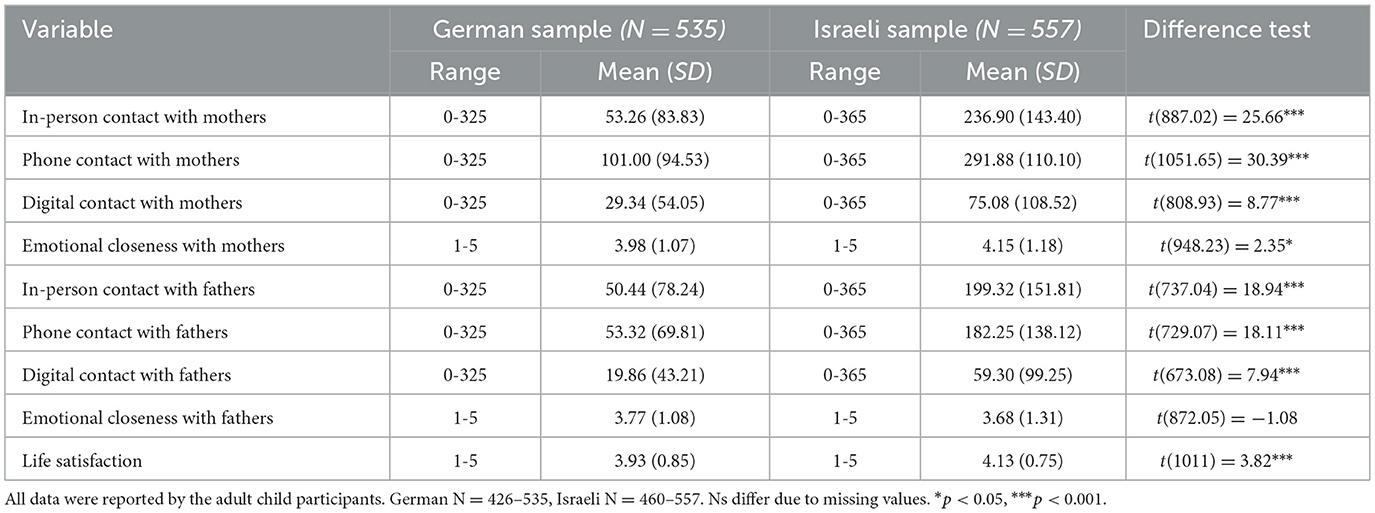

Descriptive statistics of the study variables (contact variables with mothers and fathers, emotional closeness with mothers and fathers, and life satisfaction of the adult child in each of the samples) are presented in Table 2. As shown in Table 2, Israeli, compared to German, participants reported more frequent in-person, telephone and digital contact with their mothers and fathers with medium to large effect sizes. Moreover, Israeli participants reported higher emotional closeness with their mothers, as compared to German participants with a small effect size. No significant difference was found between Israeli and German participants regarding their emotional closeness with their fathers. Lastly, Israeli participants reported on higher life satisfaction compared to the German participants with a small effect size.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the study variables among the participants in the German and Israeli samples.

Associations between the frequency of contact, emotional closeness with parents, and adult children's life satisfaction (hypothesis 1)

The models examining the associations of the frequency of each mode of contact with either mothers or fathers (in-person, phone, and digital) with emotional closeness, that in turn was associated with the adult children's life satisfaction showed adequate fit in both Israeli and German samples (see Figures 1, 2). The fit measures in the Israeli sample were Chi-square = 65.78, df = 12, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.090; NFI = 0.954; CFI =0.962. The fit measures in the German sample were Chi-square = 16.58, df = 12, p = 0.166; RMSEA = 0.027; NFI = 0.982; CFI =0.995. Controlling for adult child age, gender, and living with mother, father, or both did not change the models' fit to the data.

Table 3 presents the associations between the frequency of each contact mode with either parent and emotional closeness as well as the associations between emotional closeness with either parent and the adult children's life satisfaction.

Table 3. Structural equation models examining the association between modes of contact, emotional closeness with mothers and fathers, and the child's life satisfaction in Israel (N = 557) and in Germany (N = 535).

In-person contact

Small positive associations were found between in-person contact with either mothers or fathers and emotional closeness in the Israeli sample. The German sample yielded no associations between in-person contact with mothers or fathers and emotional closeness.

Telephone contact

Medium to strong positive associations were found between phone contact with mothers and fathers and emotional closeness in both Israel and Germany.

Digital contact

Weak positive associations were found between digital contact with mothers and fathers and emotional closeness in Germany. No associations were found in the Israeli sample between digital contact with either mothers or fathers and emotional closeness.

Emotional closeness

Emotional closeness with mothers was significantly associated with higher life satisfaction among German participants with a small effect size, while no such association was found in among Israeli participants. Emotional closeness with fathers was significantly associated with higher life satisfaction of participants in both countries with small to medium effect sizes.

Comparisons of the associations of frequency of contact, emotional closeness with parents, and adult children's life satisfaction between the Israeli and German samples (hypothesis 2)

Comparisons were conducted between each model path in the Israeli and German samples. These comparisons were performed by constraining the relevant path in the model to be equal in the two samples and comparing the chi-square goodness-of-fit measure of the unconstrained model with this measure in the constrained model. As can be seen in Table 3, the associations between digital contact and emotional closeness with either mothers or fathers were stronger in Germany compared to Israel. No other differences were evident in the model paths between the Israeli and German samples (see Table 3).

Comparisons between the associations of each mode of contact with emotional closeness (hypothesis 3)

The frequency of phone contact with Israeli mothers contributed more strongly to emotional closeness than in-person and digital contact frequencies. This conclusion was derived by constraining each pair of paths to be equal and comparing the chi-square measures of the constrained and unconstrained models: Comparing in-person to phone contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness yielded a significant difference, chi-square = 19.53, df = 1, p < 0.001; comparing phone contact to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness also yielded a significant difference, chi-square = 31.86, df = 1, p < 0.001; and comparing in-person to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness yielded a non-significant difference, chi-square = 2.25, df = 1, p = 0.134. Hence, phone contact with Israeli mothers was a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than in-person and digital contact.

Similarly, in examining Israeli participants' contacts with their fathers, we found that phone contact was a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than in-person and digital contact modes. Furthermore, in-person contact with Israeli fathers was a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than digital contact. As mentioned above, these conclusions were derived from comparing the various pairs of model paths: Comparing in-person to phone contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness yielded a significant difference, chi-square = 23.60, df = 1, p < 0.001; comparing phone to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness also yielded a significant difference, chi-square = 37.61, df = 1, p < 0.001; and comparing in-person to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness also yielded a significant difference, chi-square = 7.77, df = 1, p = 0.005. Therefore, phone contact with Israeli fathers was a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than in-person and digital contact. Moreover, in-person contact with Israeli fathers was a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than digital contact.

Upon examining German participants' contact modes with their mothers, we found that phone contact was a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than in-person contact. As mentioned above, this conclusion was derived from comparing the various pairs of models paths: Comparing in-person and phone contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness yielded a significant difference, chi-square = 14.51, df = 1, p < 0.001; comparing phone to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness yielded a non-significant difference, chi-square = 1.56, df = 1, p = 0.212; and comparing in-person to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness also yielded a non-significant difference, chi-square = 2.85, df = 1, p = 0.091. Hence, the only significant difference between the model paths showed that phone contact with German mothers had a stronger association with emotional closeness compared to in-person contact.

Upon examining German participants' contact modes with their fathers, we found that phone contact was a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than in-person contact, similar to the results regarding the mothers in Germany. This conclusion was derived from comparing the various pairs of model paths with emotional closeness: comparing in-person to phone contact frequencies' respective association with emotional closeness yielded a significant difference, chi-square = 13.24, df = 1, p < 0.001; comparing phone to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness yielded a non-significant difference, chi-square = 0.69, df = 1, p = 0.408; and comparing in-person to digital contact frequencies' respective associations with emotional closeness also yielded a non-significant difference, chi-square = 3.43, df = 1, p = 0.064.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between adult children and their parents in Germany and Israel by examining the frequencies of three modes of contact: in-person, phone, and digital. Specifically, we studied the respective contribution that each of the modes made to the adult children's life satisfaction as a function of their emotional closeness with their parents.

The models examining the contribution of the three modes of contact to life satisfaction through emotional closeness were found suitable in both countries, suggesting that the frequency of contact of adult children with their parents is associated with emotional closeness with the parents, and is therefore pertinent to adult children's life satisfaction. The study further elaborated on the respective contributions of the three modes of contact to the emotional closeness of adult children with their parents. In both the Israeli and German samples, phone contact was positively associated with emotional closeness between the adult children and their parents with medium to strong effect sizes. This is consistent with previous studies (Gentzler et al., 2011; Ramsey et al., 2013). Positive, but weak associations were found between in-person contact with mothers and fathers and emotional closeness in the Israeli sample, unlike in the German sample, where no such associations were found. As for digital contact, weak positive associations were found between frequency of digital contact with mothers and fathers and emotional closeness in the German sample, unlike the Israeli sample, where no such associations were found.

Regarding emotional closeness and its association with life satisfaction, positive associations were found between emotional closeness with fathers and adult children's life satisfaction for both the Israeli and German samples with small to medium effect sizes. However, only in the German sample did this association prove significant with mothers, with a small effect size. This absence of a significant association in the Israeli sample may be due to cultural differences so that emotional closeness with parents in Israel may be strong and independent of other personal characteristics such as the adult child's life satisfaction. Indeed, a previous study reported on higher emotional closeness between adult children and their mothers in Israel than in Germany (Bar-Tur et al., 2018). The lack of association between emotional closeness with mothers and adult children's life satisfaction in Israel may also reflect the ambivalence and conflict that can characterize emotionally close relationships (Fingerman et al., 2012). Gender differences in these relationships may play a role, such that the relationships with mothers may be more robust and less affected by parents' or adult children's personal characteristics (Chaie et al., 2020). Studies have reported that adult children tend to feel closer and more attached to their mothers than to their fathers (Golish, 2000) and that adult children's contact with mothers is more frequent than with their fathers (Birditt et al., 2009; Fingerman et al., 2012).

Hypothesis 3 predicted differences in the associations of the three modes of contact. Specifically, phone contact with parents was hypothesized to be associated with stronger adult child-parent emotional closeness than in-person and digital contact. The findings revealed that both German and Israeli adult children's phone contact with their mothers and fathers was indeed a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than in-person and digital contact with them. Moreover, Israeli adult children's in-person contact was found to be a stronger contributor to emotional closeness than digital contact with their fathers only. No other differences were found between the associations of digital, phone, and in-person contact modes with emotional closeness in the German sample.

The findings for both samples regarding the differences between the three modes of contact confirmed the significant contribution of phone contact to emotional closeness. This is consistent with reports that phone contact is a preferred and more beneficial mode of communication in intimate relationships in general (Kumar and Epley, 2020, 2021), and in particular, between adult children and their parents (Gentzler et al., 2011; Ramsey et al., 2013; Seltzer et al., 2012).

As suggested by these studies, adult children appear to interact more freely in phone communication and maintain a better flow of conversation with their parents than when meeting them in person or communicating by text messages. By responding to what they hear from their parents via the telephone, they may feel more “in sync” than in an asynchronous text chat, and hence, more connected. When there are positive and close relationships, adult children may initiate more frequent interaction with their parents via the phone. Telephone contact is more discretionary, and adult children can choose when and from where to communicate with their parents. It may be more flexible and easier to schedule than video calls because one may be able to converse with others while walking, running, involved in other tasks, or in bed without video. Personal contacts involving face-to-face meetings are often associated with family gatherings involving other family members or other people so that the opportunity for discussion of personal issues may be more limited than that created by phone contact. When adult children live closer to their parents, visiting may be more obligatory than enjoyable (Chaie et al., 2020). In-person meetings may impose more demands on adult children such that the children may find themselves unable to determine meeting duration or may find it difficult to extricate themselves from problematic encounters.

The weak associations of digital contact with emotional closeness found in the present study may be explained by the fact that digital contact is an indirect and less personal form of communication that does not offer immediate feedback. Indeed, a previous finding showed that young adults invested efforts to limit smartphone use for work in order to be more present with their families (Schuster et al., 2023), such that digital contact seems less personal and more associated to work. Another study showed that digital contact between young adults and their extended families was present regardless of the degree of closeness in these relationships, suggesting that digital contact does not promote closeness in families (Hessel, 2023). Digital textual communication may make it difficult to transmit and receive emotional reactions as visual and aural cues are absent. Some parents may also lack access or mastery of digital communication, leaving phone communication as the only remote option.

The present findings, which indicate that phone contact was more strongly associated with young adult's emotional closeness to their parents than digital contact, should be interpreted in light of the period during which the data were collected. This study took place between 2010 and 2014, before the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent rise in technology-mediated communication within families (Nowland et al., 2024). Accordingly, these findings may suggest that relatively stable and established forms of contact, such as phone communication, played a particularly significant role in fostering emotional closeness within families, compared to newer, evolving digital contact modes. Future studies using contemporary samples are needed to examine whether these patterns persist in the current technological and social context.

While our study found a positive association between the frequency of digital contact with both parents and emotional closeness in Germany, no such association was found in Israel. Whereas digital contact may be preferred in Germany, in Israel, a direct contact with parents, such as telephone calls, is favored (Bar-Tur et al., 2018; Lang and Rohr, 2012).

This may suggest that when there are strong emotional bonds between adult children and their parents, they feel more comfortable communicating by telephone than through text. As for German adult children and their parents, it seems that digital contact may be more acceptable as a mode of communication. The larger physical distances, and higher tendency of adult children to live apart of their parents in Germany, may explain this finding. In comparison to Israel, it seems that digital communication may be perceived by adult children in Germany as less of an intrusion upon their autonomy and privacy therefore allowing precise and efficient communication.

Furthermore, the relatively stronger association between digital contact and emotional closeness in Germany compared to Israel, may be explained by cultural differences between the two countries. Despite considerable individual variation in adherence to family-oriented norms within each country, Germany is often characterized as an individualistic or autonomous society, whereas Israel is typically described as a family-oriented and traditional society marked by high levels of familial involvement (Bar-Tur et al., 2018; Dykstra and Fokkema, 2011). These cultural orientations may, at least in part, account for the greater tendency of German students to live separately from their parents compared to Israeli students. This pattern was evident in the present findings, in which 8% of the German participants lived with their parents compared to 54.3% in the Israeli sample. Previous reports similarly show that approximately 86% of young adults in Israel live with their parents (Kahan-Strawczynski et al., 2016), compared to only about 15-20% in Germany (Sompolska-Rzechuła and Kurdyś-Kujawska, 2022). Living apart from parents may increase reliance on digital media to maintain emotional closeness and compensate for physical distance. Indeed, previous research has shown that following the transition to college, students tend to increase their digital communication while reducing face-to-face interactions with their home friends (Kempnich et al., 2024).

The present findings regarding the contribution of contact modes to emotional closeness between young adults and their parents can be interpreted in light of the framework of platformization (Sefton-Green et al., 2025). This contemporary perspective emphasizes that communication platforms not only enable and mediate family connections but also shape and constrain how communication unfolds within families, influencing the use and meaning of all contact modes. Although the current study reflects a historical snapshot collected prior to the widespread expansion of technology-based family communication (Nowland et al., 2024), it nevertheless aligns with the notion of platformization by suggesting that all examined contact modes (in-person, phone, and digital) operate within broader platformized conditions that may shape how family relationships are maintained and how emotional closeness is experienced. Overall, this study supports previous reports revealing the importance of maintaining long-term emotional closeness between adult children and parents (Bar-Tur et al., 2018, 2019; Fingerman et al., 2020). Our findings emphasized that, regardless of cultural, epochal or societal characteristics, emotional closeness in the parent-child relationship is a constant in human life and critical to adult children's wellbeing, alongside their need for individuation and autonomy. The study further supports the importance of maintaining the adult child-parent relationship, regardless of contact mode, as maintaining the relationship can contribute to adult children's life satisfaction, and more frequent contact may promote this goal. The importance of this study is that it highlights the efficacy of traditional, synchronic telephone contact between adult children and their parents, in comparison to in-person and more modern modes of text communication.

Limitations

This study's cross-sectional nature may suggest the possibility of reverse causation to explain the study's findings such that a definite causation path may not be ascertained. Another limitation is that the cross-national comparison contains inherent issues (Cohen, 2007), as matched samples across nations are difficult to obtain. Students in Israel may differ from students in Germany in ways that elicit more frequent contact with parents. These additional factors were not assessed in the present study.

The relatively broad age-range of the current study (21-40 years) may limit the ability to identify patterns of associations specific to narrower age groups. For example, it is plausible that satisfaction with life and emotional closeness among younger participants rely more strongly on contact with parents, given their higher dependency and lower relationship tensions (Birditt et al., 2009), compared to older participants. Future studies should therefore focus on more specific age ranges to capture potential developmental differences. Moreover, due to the convenience sampling approach of the current study, the student participants aged 21-40 in both countries do not represent the multi-cultural and socio-economically diverse composition of their respective societies. Therefore, this study's convenience sampling method limits the external validity of the comparison between the two nations. Specifically, the current samples consisted primarily of participants whose parents were generally healthy and employed. The consistent findings indicating that phone contact was associated with greater emotional closeness and higher life satisfaction among these samples underscore the important role of this contact mode in family relationships, regardless of health-related factors. However, the findings may not be representative of populations in which parents' health conditions create stronger obligations within the parent-child relationship. In such contexts, telephone contact might play an even more prominent role in fostering emotional closeness and supporting adult children's wellbeing. For example, previous research has shown that higher levels of family obligation are associated with more frequent phone contact between adult children and their parents (Stein et al., 2016). We sought to address this issue by using similar data collection methods across the two samples and controlling for socio-demographic variables. For future research, we recommend studies with more diverse populations that apply probability sampling methods, alongside qualitative studies that could further illuminate both the similarities and the differences between the two nations.

Another limitation concerns the temporal discrepancy between the data collection periods in the two samples (2010-2011 in Germany and 2013-2014 in Israel). In addition, the measurement scales used in the Israeli and German samples differed slightly. While the cultural comparison between the more familistic Israeli context and the more individualistic German context is valuable, these temporal and methodological differences may have increased measurement error and introduced potential confounds that could affect the comparability of the two samples. Furthermore, the current study did not assess the distinct contribution of different technological media (such as video calls vs. phone calls) to emotional closeness and students' life satisfaction. Although most students tend to communicate with their parents primarily through text or phone calls (Stein et al., 2016), future studies should examine specific contact modes, as different communication technologies may uniquely shape relationship quality and wellbeing among students and their parents.

In addition, the exact physical distance between participants and their parents was not assessed in the present study, although this variable may have significant implications for the frequency and meaning of young adults' phone and in-person contact frequency with their parents. Previous research has shown that physical distance from parents can have meaningful implications for young adults (Choi et al., 2020). Although controlling for co-residence with parents did not affect the current results, this variable does not substitute for direct measurement of residential distance, which may influence how different modes of contact are used and experienced. Future studies should therefore examine the role of residential distance in shaping the associations tested in the current model.

Another limitation is the use of single-item measures of the research variables. The validity of single-item measures for subjective wellbeing was proven in the past (Cheung and Lucas, 2014), but future studies may use multi-item measures to improve the evaluation of the study variables. Furthermore, the use of self-report assessments is subject to social desirability bias, such that participants' responses may differ from what their parents would have reported had they been participated in the study (Cheng et al., 2013; Kwon and Oh, 2023; Lin, 2008; Zarit et al., 2014). Future studies should survey the perspectives of parents of adult children. Further studies may also evaluate the present study's variables with respect to adult children and parents' technology-competence and attitudinal outlook toward online communication (Ledbetter, 2010).

Conclusions

Whereas social and cultural factors may explain some of the differences we found between the two nations (Bar-Tur et al., 2018; Kohli, 1999; Kohli et al., 2010), these differences were minor, with more similarities than disparities. Moreover, emotional closeness appears to comprise a significant component in the relationships of adult children and their parents in Germany and Israel. Our finding that phone communication was the most prominent contact mode, which had the strongest association with emotional closeness may come as a surprise in era of digital innovation. Irrespective of communication mode and geographical proximity, an on-going contact between adult children and their parents may be fundamental to enhanced emotional closeness and life satisfaction.

Implications

Our findings support the notion that relationships of adult children with their parents continue to be significant but complex, especially when the children grow older and there is a need for close ties as well as for separation and individuation. Since connection is vital for adult children and their parents, they may be encouraged to communicate in a synchronic and vocal mode that enables them to engage in private meaningful conversation. Parents' voices and tones of voice may be calming and encouraging in the conversation, especially when children need emotional support (Seltzer et al., 2012). Although text-based media can be excellent for scheduling meetings and sending short messages, emotional contact with the parents may be better maintained when adult children and parents converse by telephone. Conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, the current study demonstrated that in routine times, telephone communication served as an important supplement to face-to-face meetings. Situations that prevent adult children from meeting their parents in person, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, may further underscore this effect, suggesting that phone contact can become even more important to maintaining close family relationships during such crises (Nowland et al., 2024).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board at Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nuremberg, Germany. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KI: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB-T: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RL: Writing – review & editing. FL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: what is it, and what is it good for? Child Dev. Perspect. 1, 68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x

Attias-Donfut, C., and Wolff, F. C. (2000). “The redistributive effects of generational transfers,” in The Myth of Generational Conflict: The Family and State in Ageing Societies, eds. S. Arbor and and C. Attias-Donfut (London, UK: Routledge), 22–46.

Barca, M., Thorsen, K., Engedal, K., Haugen, P., and Johannessen, A. (2014). Nobody asked me how I felt: experiences of adult children of persons with young-onset dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr.. 26, 1935–1944. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213002639

Bar-Tur, L., Ifrah, K., Moore, D., Kamin, S. T., and Lang, F. R. (2018). How do emotional closeness and support from parents relate to Israeli and German students' life satisfaction? J. Fam. Issues 39, 3096–3123. doi: 10.1177/0192513X18770213

Bar-Tur, L., Ifrah, K., Moore, D., and Katzman, B. (2019). Exchange of emotional support between adult children and their parents and the children's well-being. J. Child Fam. Stud. 28, 1250–1262. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01355-2

Birditt, K. S., Manalel, J. A., Kim, K., Zarit, S. H., and Fingerman, K. L. (2017). Daily interactions with aging parents and adult children: Associations with negative affect and diurnal cortisol. J. Fam. Psychol. 31, 699–709. doi: 10.1037/fam0000317

Birditt, K. S., Miller, L. M., Fingerman, K. L., and Lefkowitz, E. S. (2009). Tensions in the parent and adult child relationship: Links to solidarity and ambivalence. Psychol. Aging 24, 287–295. doi: 10.1037/a0015196

Chaie, H. W., Zarit, S. H., and Fingerman, K. L. (2020). Revisiting intergenerational contact and relationship quality in later life: Parental characteristics matter. Res. Aging 42, 139–149. doi: 10.1177/0164027519899576

Cheng, Y. P., Birditt, K. S., Zarit, S. H., and Fingerman, K. L. (2013). Young adults' provision of support to middle-aged parents. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 70, 407–416. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt108

Cheung, F., and Lucas, R. E. (2014). Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Qual. Life Res. 23, 2809–2818. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4

Choi, H., Schoeni, R. F., Wiemers, E. E., Hotz, V. J., and Seltzer, J. A. (2020). Spatial distance between parents and adult children in the United States. J. Marriage Fam. 82, 822–840. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12606

Cohen, D. (2007). “Methods in cultural psychology,” in Handbook of Cultural Psychology, eds. S. Kitayama and D. Cohen (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 196–236.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohrdes, C., Meyrose, A. K., Ravens-Sieberer, U., and Hölling, H. (2023). Adolescent family characteristics partially explain differences in emerging adulthood subjective well-being after the experience of major life events: Results from the German KiGGS Cohort Study. J. Adult Dev. 30, 237–255. doi: 10.1007/s10804-022-09424-5

Diener, E., Gohm, C. L., Suh, E., and Oishi, S. (2000). Similarity of the relations between marital status and subjective well-being across cultures. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 31, 419–436. doi: 10.1177/0022022100031004001

Dykstra, P. A., and Fokkema, T. (2011). Relationships between parents and their adult children: A West European typology of late-life families. Ageing Soc, 31, 545–569. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X10001108

Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y. P., Kim, K., Fung, H. H., Han, G., Lang, F. R., Lee, W., and Wagner, J. (2016a). Parental involvement with college students in Germany, Hong Kong, Korea, and the United States. J. Fam. Issues 37, 1384–1411. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14541444

Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y. P., Tighe, L., Birditt, K. S., and Zarit, S. (2012). “Relationships between young adults and their parents,” in Early Adulthood in a Family Context, eds. A. Booth, S. L. Brown, N. S. Landale, W. D. Manning, and S. M. McHale (New York, NY: Springer), 59–85. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1436-0_5

Fingerman, K. L., Huo, M., and Birditt, K. S. (2020). A decade of research on intergenerational ties: Technological, economic, political, and demographic changes. J. Marriage Fam. 82, 383–403. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12604

Fingerman, K. L., Kim, K., Birditt, K. S., and Zarit, S. H. (2016b). The ties that bind: midlife parents' daily experiences with grown children. J. Marriage Fam. 78, 431–450. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12273

Frankel, B. G., and Dewitt, D. J. (1989). Geographical distance and intergenerational contact: An empirical examination of the relationship. J. Aging Stud. 3, 139–162. doi: 10.1016/0890-4065(89)90013-3

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., and Richler, J. J. (2012). Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 141, 2–18. doi: 10.1037/a0024338

Gentzler, A. L., Oberhauser, A. M., Westerman, D., and Nadorff, D. K. (2011). College students' use of electronic communication with parents: Links to loneliness, attachment, and relationship quality. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 14, 71–74. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0409

Gilligan, M., Suitor, J. J., and Pillemer, K. (2022). Patterns and processes of intergenerational estrangement: A Qualitative study of mother–adult child relationships across time. Res. Aging 44, 436–447. doi: 10.1177/01640275211036966

Golish, T. D. (2000). Changes in closeness between adult children and their parents: A turning point analysis. Commun. Rep. 13, 79–97. doi: 10.1080/08934210009367727

Goodman-Deane, J., Mieczakowski, A., Johnson, D., Goldhaber, T., and Clarkson, P. J. (2016). The impact of communication technologies on life and relationship satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 57, 219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.053

Grieve, R., Indian, M., Witteveen, K., Tolan, G. A., and Marrington, J. (2013). Face-to-face or Facebook: can social connectedness be derived online? Comput. Hum. Behav. 29, 604–609. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.11.017

Guo, M., Chi, I., and Silverstein, M. (2012). The structure of intergenerational relations in rural China: A latent class analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 74, 1114–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01014.x

Hessel, H. (2023). A typology of US emerging adults' online and offline connectedness with extended family. J. Adult Dev. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10804-023-09452-9

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jin, B., and Park, N. (2010). In-person contact begets calling and texting: Interpersonal motives for cell phone use, face-to-face interaction, and loneliness. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 13, 611–618. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0314

Jin, B., and Pena, J. (2010). Mobile communication in romantic relationships: Mobile phone use, relational uncertainty, love, commitment, and attachment styles. Commun. Rep. 23, 39–51. doi: 10.1080/08934211003598742

Kahan-Strawczynski, P., Amiel, S., and Konstantinov, V. (2016). Status of young adults in Israel in key areas of life. Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute. Available online at: https://brookdale-web.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2018/01/736-16_Eng_summary.pdf (Accessed November 25, 2025).

Kempnich, M., Wölfer, R., Hewstone, M., and Dunbar, R. I. M. (2024). How the size and structure of egocentric networks change during a life transition. Adv. Life Course Res. 61:100632. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2024.100632

Kohli, M. (1999). Private and public transfers between generations: Linking the family and the state. Eur. Soc. 1, 81–104. doi: 10.1080/14616696.1999.10749926

Kohli, M., Albertini, M., and Künemund, H. (2010). “Linkages among adult family generations: Evidence from comparative survey research,” in Family, Kinship and State in Contemporary Europe. Vol 3, Perspectives on Theory and Policy, eds. P. Heady and M. Kohli (Frankfurt, Germany: Frankfurt am Main Campus), 195–220.

Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J., Helgeson, V., and Crawford, A. (2002). Internet paradox revisited. J. Soc. Issues 58, 49–74. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00248

Kumar, A., and Epley, N. (2020). Research: Type less, talk more. Harvard Business Review. Available online at: https://hbr.org/2020/10/research-type-less-talk-more (Accessed December 8, 2025).

Kumar, A., and Epley, N. (2021). It's surprisingly nice to hear you: misunderstanding the impact of communication media can lead to suboptimal choices of how to connect with others. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen.. 150, 595–607. doi: 10.1037/xge0000962

Kwon, H. J., and Oh, J. (2023). Comparing older parents' and adult children's fear of falling and perceptions of age-friendly home modification: an integration of the theories of planned behavior and protection motivation. Behav. Sci. 2013, 403. doi: 10.3390/bs13050403

Lang, F. R., and Rohr, M. K. (2012). “Family and care in later adulthood: A lifespan motivational model of family care giving,” in Family, Ties, and Care: family transformation in a Plural Modernity, eds. H. Bertram and N. Ehlert (Opladen, Germany: Barbara Budrich Publishers), 271–288.

Ledbetter, A. M. (2010). Family communication patterns and communication competence as predictors of online communication attitude: evaluating a dual pathway model. J. Fam. Commun. 10, 99–115. doi: 10.1080/15267431003595462

Lin, I.-F. (2008). Mother and daughter reports about upward transfers. J. Marriage Fam. 70, 815–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00524.x

Martinez-Escudero, J. A., Villarejo, S., Garcia, O. F., and Garcia, F. (2020). Parental socialization and its impact across the lifespan. Behav. Sci. 2020:101. doi: 10.3390/bs10060101

Merz, E. M., Schuengel, C., and Schulze, H. J. (2008). Inter-generational relationships at different ages: an attachment perspective. Ageing Soc. 28, 717–736. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X08007046

Norris, J. E., Pratt, M. W., and Kuiack, S. L. (2003). “Parent-child relations in adulthood: an intergenerational family systems perspective,” in Handbook of Dynamics in Parent-Child Relations, ed. L. Kuczynski (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 325–344 doi: 10.4135/9781452229645.n16

Nowland, R., McNally, L., and Gregory, P. (2024). Parents' use of digital technology for social connection during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. Scand. J. Psychol. 65, 533–548. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12998

Ramirez, A., Jr, Dimmick, J., Feaster, J., and Lin, S.-F. (2008). Revisiting interpersonal media competition: the gratification niches of instant messaging, email, and the telephone. Commun. Res. 35, 529–547. doi: 10.1177/0093650208315979

Ramsey, M. A., Gentzler, A. L., Morey, J. N., Oberhauser, A. M., and Westerman, D. (2013). College students' use of communication technology with parents: comparisons between two cohorts in 2009 and 2011. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 16, 747–752. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0534

Schroeder, J., and Epley, N. (2015). The sound of intellect: speech reveals a thoughtful mind, increasing a job candidate's appeal. Psychol. Sci. 26, 877–891. doi: 10.1177/0956797615572906

Schroeder, J., and Epley, N. (2016). Mistaking minds and machines: How speech affects dehumanization and anthropomorphism. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145:1427. doi: 10.1037/xge0000214

Schroeder, J., Kardas, M., and Epley, N. (2017). The humanizing voice: Speech reveals, and text conceals, a more thoughtful mind in the midst of disagreement. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1745–1762. doi: 10.1177/0956797617713798

Schuster, A. M., Cotten, S. R., and Meshi, D. (2023). Established adults, who self-identify as smartphone and/or social media overusers, struggle to balance smartphone use for personal and work purposes. J. Adult Dev. 30, 78–89. doi: 10.1007/s10804-022-09426-3

Sefton-Green, J., Mannell, K., and Erstad, O. (2025). “The platformization of the family,” in Towards a Research Agenda, eds. J. Sefton-Green, K. Mannell and O. Erstad (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan). doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-74881-3

Seltzer, L. J., Prososki, A. R., Ziegler, T. E., and Pollak, S. D. (2012). Instant messages vs. speech: hormones and why we still need to hear each other. Evol. Hum. Behav. 33, 42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.05.004

Seltzer, L. J., Ziegler, T. E., and Pollak, S. D. (2010). Social vocalizations can release oxytocin in humans. Proc. R. Soc. B. 227, 2661–2666. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0567

Sompolska-Rzechuła, A., and Kurdyś-Kujawska, A. (2022). Generation of young adults living with their parents in European Union countries. Sustainability 14:4272. doi: 10.3390/su14074272

Stein, C. H., Osborn, L. A., and Greenberg, S. C. (2016). Understanding young adults' reports of contact with their parents in a digital world: psychological and familial relationship factors. J. Child Fam. Stud. 25, 1802–1814. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0366-0

Suitor, J. J., Hou, Y., Stepniak, C., Frase, R. T., and Ogle, D. (2022). “Parent-adult child ties and older adult health and well-being,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.013.383

Szydlik, M. (2016). “Contact: staying in touch,” in Sharing Lives: Adult Children and Parents (London: Routledge), 61–76. doi: 10.4324/9781315647319-4

Umberson, D. (1992). Relationships between adult children and their parents: Psychological consequences for both generations. J. Marriage Fam. 54, 664–674. doi: 10.2307/353252

Utz, S. (2007). Media use in long-distance friendships. Inf. Commun. Soc. 10, 694–713. doi: 10.1080/13691180701658046

Van Gaalen, R. I., and Dykstra, P. A. (2006). Solidarity and conflict between adult children and parents: a latent class analysis. J. Marriage Fam. 68, 947–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00306.x

Wang, J., and Wang, H. (2011). The predictive effects of online communication on well-being among Chinese adolescents. Psychology 2, 359–362. doi: 10.4236/psych.2011.24056

Keywords: adult children, intergenerational relationships, young adulthood, contact modes, life satisfaction

Citation: Ifrah K, Bar-Tur L, Lifshitz R and Lang FR (2025) Phone contact with parents contributed to emotional closeness and life satisfaction of Israeli and German students during 2010–2014. Front. Educ. 10:1613861. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1613861

Received: 23 July 2025; Revised: 09 November 2025;

Accepted: 17 November 2025; Published: 18 December 2025.

Edited by:

Yang Liu, Jishou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Tayyeb Ramazan, The University of Lahore, PakistanMariángeles Castro-Sánchez, Universidad Austral, Argentina

Copyright © 2025 Ifrah, Bar-Tur, Lifshitz and Lang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kfir Ifrah, a2ZpcmlAcnVwcGluLmFjLmls

†ORCID: Frieder R. Lang orcid.org/0000-0002-2660-1619

Kfir Ifrah

Kfir Ifrah Liora Bar-Tur

Liora Bar-Tur Rinat Lifshitz

Rinat Lifshitz Frieder R. Lang

Frieder R. Lang