- 1School of Language and Liberal Studies, Fanshawe College, London, ON, Canada

- 2English Language Department, Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

This study investigates Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) in English as a foreign language (EFL) classrooms in Egyptian higher education. The study was conducted at multiple universities in Egypt, where English is widely taught and learned as a foreign language. Data was collected through a questionnaire completed by 49 EFL instructors, supplemented by five one-to-one semi-structured interviews with participants from the questionnaire. The results demonstrate that EFL teachers generally acknowledge and frequently observe FLA among students, particularly during speaking activities. Specific sub-skills such as summarizing and presenting were identified as anxiety-inducing. Although some instructors consider FLA motivating, others view it as detrimental to student progress. Instructors also suggest creating supportive environments where mistakes are valued as part of the learning process to mitigate FLA. Interestingly, it was found that instructors themselves may experience FLA, particularly when speaking with native speakers or teaching in a second language (L2). Strategies suggested by instructors to alleviate FLA include group discussions, role plays, individual activities with preparation, and peer support. Overall, instructors' attitudes, rapport, and feedback play a crucial role in managing FLA levels in the classroom. This study contributes to raising awareness among stakeholders toward FLA in Egypt and the broader EFL context.

Introduction

Over the years, Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) has been investigated by researchers and educators in various classroom contexts, and it is defined as “the worry and negative emotional reaction aroused when learning or using a second language” (MacIntyre, 1998, p. 27). Some researchers (e.g., Gürsoy and Akin, 2013; Horwitz et al., 1986; Öztürk and Gürbüz, 2013; Ran et al., 2022; Russell, 2020) have investigated this issue and underlined the different variables that correlate with it. A few studies (e.g., Öztürk and Gürbüz, 2013; Park and French, 2013; Shi and Zhang, 2023) explored student-related variables such as age, gender, self-esteem, self-perceived competence, and proficiency level, while others concentrated on college English teachers' and prospective teachers' FLA (e.g., Liu and Wu, 2021; Tüm, 2019). In addition, researchers such as Javaid et al. (2023) and Ran et al. (2022) investigated all four language skills, while others, such as Alla et al. (2020) and Russell (2020), chose to focus on FLA and how it affects online and in-person learning and learners' FLA.

Furthermore, although other studies (e.g., Liu and Wu, 2021; Tüm, 2019) have examined teacher-related anxiety, little attention has been given to how teachers themselves experience and cope with FLA, particularly in contexts where both instructors and students use English as an additional language. Existing research often generalizes FLA experiences across different EFL settings, overlooking the sociocultural and institutional factors that shape anxiety in specific contexts. In particular, limited research has explored FLA in the Egyptian EFL classroom, where English is widely taught, yet both students and instructors encounter unique linguistic, pedagogical, and cultural challenges. Therefore, it is essential to investigate how EFL teachers in Egyptian higher education perceive, influence, and manage FLA.

This study, based on the research of Attia (2015), aims to explore teachers' perceptions and attitudes toward FLA and the effects of different activities on anxiety levels. In a sense, the study examines how teachers perceive FLA, their influence, and how they manage it. In addition, it discusses the various activities teachers use in class and how they may affect FLA. Furthermore, the study explores all four language skills (i.e., reading, writing, listening, and speaking) and how teachers address FLA when different skills are involved, providing a comprehensive overview of how FLA interacts with these skills. This broad overview helps clarify whether teachers are aware that different skills can cause anxiety, especially with some literature suggesting that teachers tend to focus more on one skill, speaking, and view it as the most anxiety-provoking. This study is guided by the following research questions:

1. How do EFL teachers in Egyptian higher education institutions perceive FLA in their classrooms, and what strategies do they report using to mitigate or exacerbate it?

2. To what extent do EFL teachers in Egypt experience FLA themselves, and how does it manifest in their teaching experiences?

The following section provides a general overview of EFL in the Egyptian context and a more detailed examination of FLA in the literature.

EFL in the Egyptian context

One of the reasons for the spread of the English language in many countries is globalization; Phillipson (2017) underlined that globalization played an important role in the spread of the English language, with countries such as the US and UK portraying English as “[…] the sole language of globalization,” which he described as being “patently false” (p. 328). In addition to globalization, the perceived superiority of the English language over other languages has significantly contributed to its widespread use (Phillipson, 2017). This perception was partly shaped by misleading scientific studies that falsely claimed the colonizers' language indicated higher intelligence (Liggett, 2014). In a sense, people in colonized regions were often drawn to the colonizer's language and culture, perceiving it as superior or believing it could offer better opportunities in life. Consequently, colonialism was pivotal in promoting the spread of English across many countries and regions during the British colonial era (Schneider, 2018).

Colonialism and its effects were not far from Egypt, as the British military occupied Egypt in 1882, and Egypt's independence was only declared decades later, in 1922; however, “Britain did not withdraw all its troops until after the 1956 Suez Crisis” (University of Cambridge, n.d.). Therefore, the English language has been officially present in the Egyptian context and its educational institutions for about 150 years (Latif, 2018).

At present, English is the main foreign language taught in Egyptian educational institutions, and it is widely used in different areas of everyday life in Egypt, including commerce, media, tourism, business, science, and technology (Latif, 2018; Schaub, 2000). As a result, many people in Egypt strongly desire to learn English, and English instruction receives considerable attention from the Egyptian government and families (Latif, 2018). Such interest in the language, learning it and speaking it with certain accents, is partly due to English being viewed as a form of linguistic capital, and speaking it well grants individuals access to certain communities and jobs. Morrison and Lui (2000) define linguistic capital as “fluency in, and comfort with, a high-status, world-wide language which is used by groups who possess economic, social, cultural and political power and status in local and global society” (p. 473). Attia (2023) underlines that linguistic capital is also connected to other forms of capital (i.e., cultural, economic, and educational capitals), which explains, to a certain extent, why there is a strong pursuit to perfect the language to gain access to such capitals. Moreover, most companies require English language skills, even if the job will be mainly conducted in Arabic, and many job interviews are also conducted in English. Consequently, the widespread and strong presence of English in Egypt warrants further examination of the language, its use, and the challenges it poses in the EFL classroom.

Literature review and conceptual framework

This section explores FLA's meaning and how it has been studied in existing literature. By reviewing key theories and research, we aim to set the stage for understanding how FLA impacts EFL classrooms, particularly in the Egyptian context.

Foreign language anxiety (FLA)

Horwitz et al. (1986) defined FLA as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process” (p. 128). They explained that FLA represents the specific beliefs and feelings of some learners while learning a second/foreign language. Several researchers have investigated FLA and taken different positions on it. Some of them highlighted the negative association between FLA, academic achievement, and foreign language proficiency (Botes et al., 2020; Jugo, 2020). For example, Jugo (2020) underlined in his study investigating Filipino learners that students' FLA levels correlated negatively with their proficiency, highlighting that the more anxious learners had lower English language proficiency. Other researchers (e.g., Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre, 1995; Park and French, 2013) explained that the relationship between language anxiety and different variables is not simple and can be a cause or an effect of poor achievement, depending on the situation. To clarify, when investigating the effects of gender on FLA, Park and French (2013) underlined that females had higher levels of FLA; however, anxiety had a facilitative nature, leading to students with higher levels of anxiety receiving higher grades. According to the researchers, this facilitative effect is attributed to the teachers and their handling of learners' anxiety in the classroom, which ultimately leads to positive outcomes.

FLA, learner-related variables, and the four skills

Several learner-related variables affect FLA, including learners' attitudes, self-perceived competence, self-evaluation, identity, foreign language performance, age, and proficiency levels. Cognitive differences—such as those outlined in the Theory of Multiple Intelligences—may also influence how students experience language learning and affective responses, such as anxiety (Abushihab, 2024).

In particular, learners' attitudes, self-perceptions, self-evaluation, self-esteem, and positive orientation are viewed as important variables influencing FLA. Studies show that the more positive these factors are, the lower the learners' anxiety levels tend to be (Huang, 2014; Jin and Dewaele, 2018; Jugo, 2020; Liu and Chen, 2013; Luo, 2018; Ran et al., 2022). These findings suggest that FLA is shaped by multiple psychological factors that instructors must consider in their teaching. For example, Ran et al. (2022) emphasized a strong link between foreign language achievement, self-evaluation, and FLA, noting that students who rated their English listening, writing, and reading skills more highly tended to experience lower levels of anxiety. More recently, Alzobidy et al. (2024) emphasized the role of multimedia in supporting cognitive engagement and reducing the mental load of EFL learners, suggesting that well-designed multimodal instruction may also contribute to lowering anxiety in skill-based tasks.

Beyond psychological traits, many studies (e.g., Ay, 2010; Javaid et al., 2023; Machida, 2015; Merç, 2011; Ran et al., 2022; Young, 1990; Zhang, 2019) have examined how specific language skills—listening, speaking, reading, and writing—affect levels of FLA. For instance, Ay (2010) explored anxiety in relation to these four skills across different proficiency levels and found that a balanced focus on both receptive and productive skills can help reduce learners' anxiety.

Furthermore, recent research (e.g., Alla et al., 2020; Russell, 2020; Shi and Zhang, 2023) has investigated FLA in online learning environments, especially relevant due to the shift caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Alla et al. (2020) found both positive and negative effects of distance learning on FLA: while communication apprehension and fear of negative evaluation increased, test anxiety and fear of making mistakes decreased. These findings highlight the importance of understanding students' psychological and cognitive traits and addressing FLA in both face-to-face and online contexts.

Alleviating FLA in the classroom

Due to the various effects of FLA on the learners and learning environment, many studies focused on teachers' roles and strategies to alleviate FLA. For example, many studies (e.g., Algazo, 2023, 2024; Al-Shahwan, 2024; Bruen and Kelly, 2017) have highlighted that the exclusive use of a second language (L2) in the classroom can have a negative impact on L2 learners. These studies also noted that teachers who allow limited use of the first language (L1) in their L2 classes can increase student motivation and create a more relaxed learning atmosphere. Other studies (e.g., Chan and Lo, 2022; Cheng, 2018; Gacs et al., 2020; Halimi et al., 2019; Jin et al., 2017, 2020, 2021; Koch and Terrell, 1991; Lo, 2022; Toyama and Yamazaki, 2022) have also suggested increasing instructors' awareness of FLA, providing instructors' support, employing motivational strategies, incorporating board games, utilizing contracted speaking, fostering students' enjoyment, and utilizing specific feedback methods to alleviate FLA in L2 classes and enhance their academic performance. For example, Halimi et al. (2019) underlined different motivational strategies that teachers can use in class to reduce anxiety, such as providing positive feedback, being familiar with students' learning preferences, avoiding competitions between students, and focusing on pair and group work. Also, Jin et al. (2020) highlighted the role of contracted speaking, that is, students sign a contract to commit to speaking in FL class, which led to the reduction of FLA levels in a short period of time (p. 1).

While focusing on the learners and their struggle with FLA in the classroom, remarkably, few studies (e.g., Gannoun and Deris, 2022; Kobul and Saraçoglu, 2020; Liu and Wu, 2021; Machida, 2015; Merç, 2011) focused on teachers suffering from FLA. For instance, Liu and Wu (2021) shed light on the general anxiety of college teachers in China, stemming from their teaching load, grant applications, and research publications. They also discussed teachers' FLA, which stemmed from teachers' confidence in their English competence and apprehension of speaking English. Teachers' FLA is an important point that merits further exploration and should complement the work conducted on FLA, the classroom, and EFL learners.

The affective filter hypothesis

The Affective Filter Hypothesis was proposed to explain why some learners are unable to acquire language successfully, despite being exposed to considerable amounts of comprehensible input (Lightbown and Spada, 2013). The hypothesis states that having understandable input is not a sufficient prerequisite for learning a target language and that many affective elements will influence the learning outcome during the L2 acquisition process. These affective elements act as filters and mental blocks (Krashen, 1985), controlling understandable input entry to the Language Acquisition Device (LAD).

Based on the hypothesis, the language input cannot be converted into intake before the affective filter (Lai and Wei, 2019). Many affective factors may influence language acquisition (Lai and Wei, 2019); (1) Motivation, in which language learners have clear goals that determine the learning outcomes. (2) Characters in which language learning is somehow linked to the learner's self-confidence (i.e., more self-confidence means more language learning progress). (3) Emotion: This refers to the level of anxiety that can hinder input and language learning.

The third affective filter, emotions, is the one that this study will focus on, as students' and teachers' anxiety levels affect their learning and teaching experiences. Such an effect plays a crucial role in the relationship between learners and teachers, as well as the foreign language, a relationship that crystallizes in the ESL classroom. As mentioned in the literature review, FLA can negatively affect students' foreign language proficiency (Jugo, 2020), foreign language achievement, and self-evaluation (Ran et al., 2022). Furthermore, teachers' general anxiety was influenced by their teaching load, grant applications, and research publications, and some teachers faced FLA due to their low confidence in their English competence (Liu and Wu, 2021).

In this study, the Affective Filter Hypothesis is employed to understand and analyze students' FLA levels, how their teachers perceive them, and how teachers can support learners when they notice signs of FLA. The hypothesis is also utilized to explore teachers' FLA, its impact on their teaching experience, and strategies for overcoming FLA in the classroom. Such a lens is utilized to investigate teachers' confidence and anxiety levels while teaching to understand how FLA affects instructors, specifically those who speak English as an Additional Language in the Egyptian EFL classroom in higher education. Despite the initial focus on students and their FLA, it was essential to dive into teachers' FLA, which was expressed and commented on by some of the teacher participants. With the English language being a requirement for various jobs, a tool to enter certain circles and spaces, and due to various misconceptions about native and non-native teachers and their teaching and spoken abilities, which are reinforced by global ideologies of native-speakerism and neoliberal market pressures in English language teaching (Clymer et al., 2020), it is essential to explore FLA in the Egyptian context to explore where it originates, how to alleviate it, and how to utilize it for the best of both learners and teachers.

The previous overview of the literature provides a general idea of the extensive literature conducted on FLA over the past few decades. The current study will delve deeper to explore FLA and its effects on learners and teachers, as well as teachers' awareness of this phenomenon, and provide suggestions to support learners.

Methodology

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining both quantitative and qualitative research to provide a comprehensive understanding of how EFL teachers perceive and experience FLA. By integrating statistical analysis with personal insights, this approach allows us to see not just the broader patterns but also the authentic voices and experiences behind the numbers.

Setting and participants

The study was conducted at multiple universities in Egypt, including both governmental and private institutions. The focus was on preparatory English programs and English departments at various universities. English is a mandatory subject across the various schools and departments of these universities, and the commitment to integrating English into these universities' curricula provides an ideal environment for studying the role of FLA among both students and teachers in the Egyptian context. Some of the programs that participated in the study were the Intensive English Program (IEP) at the American University in Cairo (AUC), the School of Continuing Education (SCE), which is affiliated with the AUC, English Language Institute (ELI) at the Arab Academy for Science and Technology, and various English department at Future University of Egypt and the Faculty of Arts at Aswan and Mansura Universities.

For the participants, two data collection methods were employed in this study: an online questionnaire and voluntary semi-structured interviews. Questionnaire participants consisted of 49 EFL Instructors who worked at eight universities and various language academies in different governorates in Egypt, including Cairo, Alexandria, Mansoura, and Aswan, among others, and who taught in different departments and faculties. The participants spoke different languages: 43 spoke Arabic as their first language, five spoke English as their first language, and one spoke Hungarian as their L1. The participants' ages ranged from 23 to 55, and their teaching experience varied, spanning from novice instructors with 1 year of experience to those with up to 15 years of experience.

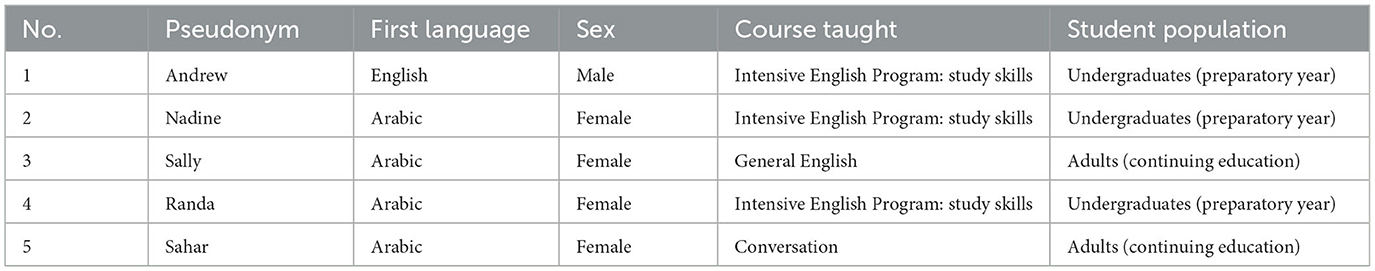

Regarding the interviews, the participants were primarily from a private university and its affiliated adult education center in Cairo. The sample consisted of five instructors, and participation in the interviews was voluntary. Instructors who were interested in participating were asked to indicate this in the questionnaire and provide their email address. The interviews were conducted one-on-one and were semi-structured, with a duration of between 30 and 45 min each. The semi-structured format was chosen to avoid confining the researcher to a predetermined set of questions and to allow for the exploration of any new and interesting points that might arise during the interview. Details about the teacher participants are included in Table 1.

This study employed a convenience sampling method to recruit participants, as it was the most suitable approach given the study's constraints and the characteristics of the research setting. Although convenience sampling carries a risk of bias, steps were taken to minimize its impact by maximizing participant numbers and implementing predefined selection criteria to enhance diversity and representativeness. Specifically, participants were required to meet the following conditions:

1. They had to be English teachers at an Egyptian university at the time of data collection.

2. For the interview phase, participants needed at least 1 year of teaching experience and prior participation in the online questionnaire.

The experience requirement for interviewees was essential for the qualitative phase of the study, as it aimed to elicit in-depth descriptions of participants' perceptions and practices regarding FLA.

Data collection

The data collection procedures continued for 4 weeks. As mentioned earlier, two instruments were used to gather the data from the teacher participants: an online questionnaire and individual semi-structured interviews. Prior to collecting data, an ethics approval was sought from the Research Ethics Board (REB) at the American University in Cairo. The ethics detailed participants' rights and details of the study. The participants were informed that they can withdraw from the study at any point and that their identity will be anonymous.

Teachers' questionnaire

The questionnaire was the first tool used to collect data from the participants. An online questionnaire was designed by the first author, inviting all potential participants in the study to complete it. Forty-nine instructors completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to understand how instructors perceive FLA and how they deal with it when it arises in their classes. It also explored the types of activities that instructors use, whether they think they cause anxiety or not, and which of them increases or decreases anxiety levels. It also investigated the effect of different skills and sub-skills on FLA levels, instructors' awareness of their potential influence on FLA, and the effects of different feedback strategies they use on FLA levels.

Interviews

Five instructors were interviewed after completing the teachers' questionnaire, and the data yielded from the questionnaire were elaborated on during the interviews. The teachers interviewed expressed their interest in participating in the interview phase, and they were recruited. The interviews were one-on-one semi-structured, and each interview lasted 30–45 min.

The instructors were asked to reflect on some of their answers in the questionnaire, and the researcher followed up with additional questions to gain an in-depth understanding of the instructors' perceptions of FLA and related variables. Instructors were asked to provide detailed answers to various questions related to their awareness and understanding of FLA and the effects they believe they have on it. They were also asked about the various variables that could affect FLA levels, such as sex, feedback strategies, and different classroom activities. The researcher referred to the teachers' answers in the questionnaire and asked them to elaborate on those answers and give their reasons for each. In addition, instructors were asked to provide examples to clarify their responses.

Questionnaire and interview design and validation

The first author designed the first draft of the questionnaire items and interview questions after carefully reviewing the relevant literature. To ensure they were valid and effective, experts in the field reviewed the initial drafts, assessing each question for clarity, relevance, and alignment with the study's goals.

Following this, a pilot study was conducted to assess the effectiveness of the questionnaire items and their reliability. The first draft was given to a sample of potential participants who were excluded from the main study. The goal was to spot any confusing or unclear questions that might make it difficult for participants to respond accurately. To help refine the questionnaire, participants were encouraged to share open-ended feedback on the clarity of the questions, their wording, and the response options.

Similarly, for the interview questions, a mock interview was conducted with an instructor who was excluded from the main study. The instructor worked at a language center, teaching English as a foreign language. The interview protocol was followed with her, and feedback from the mock interview helped assess the flow, clarity, and relevance of the questions to the study's objectives, as well as the time required for the interview. The researcher conducted a 45-min interview with the teacher, asking all the questions that had been designed by the researcher. After the interview, the researcher invited the teacher to underline any items that they felt were redundant and/or unclear. Based on the insights gathered from the pilot study, necessary revisions were made. Any unclear, redundant, or potentially misleading questions were refined or removed. After these adjustments, the final version of the questionnaire and interview questions was ready for data collection.

Data analysis

A quantitative method was used to analyze teachers' questionnaires. The data was organized in an Excel sheet and statistically analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). Descriptive analysis (Dornyei, 2007) was employed to calculate the mean and standard deviation, summarizing teachers' views on the most anxiety-provoking skills, sub-skills, and activities. This approach allowed for a clear understanding of trends in the data by organizing and summarizing the responses into interpretable patterns.

The main themes in the questionnaire were: the types of activities teachers use and whether they think they cause anxiety or not, the effect of different skills and sub-skills on FLA levels, teachers' awareness of their potential influence on FLA, and the effects of different feedback strategies teachers use on FLA levels. Descriptive analysis offered an overview of the central tendencies and variability in responses, facilitating the identification of key areas of concern related to FLA.

Regarding the qualitative phase, the teachers' interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and thematically coded through a three-phase process: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding (Lichtman, 2013; Merriam and Tisdell, 2016).

In the first phase, open coding, the data were fragmented into smaller units, such as individual words, phrases, and key concepts. This stage involved a meticulous examination of interview transcripts to capture recurring ideas. For instance, multiple instructors frequently referenced terms like “student hesitation,” “fear of making mistakes,” and “pressure to perform,” indicating prevalent themes of anxiety tied to oral communication.

During the second phase, axial coding, these initial codes were systematically categorized into broader themes based on their relationships. Emerging themes included teachers‘ awareness of FLA, the role of feedback in anxiety levels, activity-based anxiety triggers, and teachers' own experiences with anxiety.

In the final phase, selective coding, the most important themes were carefully chosen and refined to highlight key insights. At this stage, the data were pieced together to tell a clear and meaningful story about how FLA affects the classroom. In the following section, a detailed, theme-based representation of the study's results will be presented, highlighting the significant findings from the data collection methods.

Results

The study's results, collected from the online questionnaire and interviews, highlighted teachers' perceptions of their influence on the issue of FLA and identified practical activities to address it in the EFL classroom.

Awareness of FLA in the EFL classroom

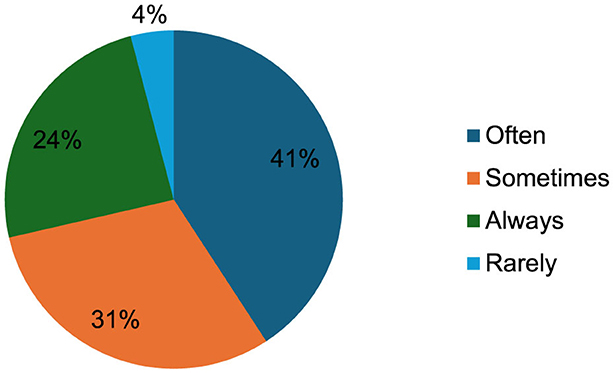

The results of the study have shown that teachers manifested an awareness and understanding, at least to some extent, of FLA, and they provided several definitions indicating that FLA is related to the different skills and the foreign language learning environment, and that even some teachers suffer from this issue. Even though the term itself was new to some of the teachers, they could guess what it means, or what they think it means, and how it manifests in their students. Prior to asking teachers about the specific skills that induced anxiety, they were asked about how frequently they noticed FLA in their classroom. Figure 1 illustrates the frequency and percentage of their answers.

The results have shown that over 40% of the participants often notice FLA in their classroom, and < 31% sometimes notice this issue. More than 24% said they always notice FLA in class, while < 5% rarely notice it. This shows that most of the questionnaire participants noticed students' anxiety in their EFL classes.

When asked about teachers' awareness of FLA in the classroom, most of the interview teacher participants explained that not all teachers are aware of this issue for different reasons, such as the difficulty of detecting FLA for teachers in general and novice teachers in particular. In addition, they mentioned that even when teachers notice FLA, they do not necessarily relate it to the foreign language but to different reasons, such as students' character, sex, or cultural reasons. One of the interesting points that Randa mentioned was, “I think they are aware, but not necessarily give it much attention or give students who suffer from it extra attention.” She explained that this, in some cases, can be due to the large number of students or to the fact that the teachers might believe that this is not their responsibility but the counseling center's responsibility.

Teachers' perception of FLA and four skills

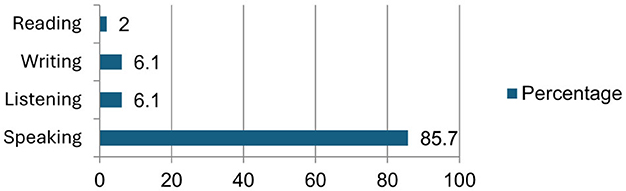

Most of the teacher participants in the questionnaire mentioned that FLA is associated with anxiety about speaking in a foreign language. Some of the participants in the interviews expressed similar ideas as well. Three teachers, Sally, Andrew, and Nadine, mentioned that speaking is the most anxiety-provoking.

At the same time, the other two participants, Sahar and Randa, explained that FLA is not related to a specific skill but depends on the learners themselves. Andrew, for example, indicated that he related FLA to speaking, because he had personal experience with FLA while studying Arabic as an L2 and specifically while speaking with native speakers. Figure 2 presents the results teachers provided in the questionnaire in response to the relation between anxiety and different language skills, and the skill they believe is the most anxiety-provoking.

Over 85% of the questionnaire teacher participants and three of the teacher interviewees, Sally, Andrew, and Nadine, viewed speaking as the most anxiety-provoking of the four skills. Less than 15% of the teacher participants viewed other skills, such as reading, writing, and listening, to be the most anxiety-provoking.

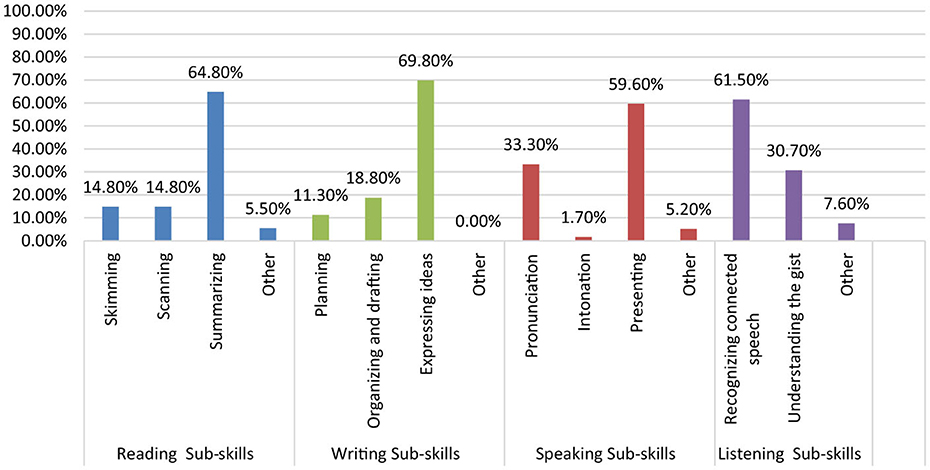

The analysis of the questionnaire also showed that teachers viewed some of the sub-skills to be more anxiety-provoking for students than others; Over 71% of the participants indicated that summarizing is the most anxiety-provoking reading sub-skill, and over 69% believed that expressing ideas is the most anxiety-provoking writing sub-skill. Presenting was the most anxiety-provoking speaking sub-skill, with a percentage of over 59%, and over 61% indicated that recognizing connected speech is the most anxiety-provoking listening sub-skill. Figure 3 presents the responses provided by the teacher participants with respect to the most anxiety-provoking sub-skills.

Expressing ideas was the most anxiety-provoking writing sub-skill, but Nadine and Sally highlighted that planning, brainstorming, and outlining are more anxiety-provoking. They mentioned that some students did not learn how to do this before joining college. For example, Nadine said, “When you are faced with this blank piece of paper and you have absolutely nothing written on it, […] this is stressful.” Both instructors highlighted that teaching students writing techniques and giving them the tools alleviates this type of anxiety.

Presenting was the most anxiety-provoking speaking sub-skill, but all the interview participants referred to this as anxiety about public speaking and not FLA. Recognizing connected speech was the most anxiety-provoking listening sub-skill, and one of the teachers, Sally, mentioned that this is because students tend to get stuck on the words they do not know, because they believe they need to understand every single word.

Facilitative and debilitating anxiety

During the interviews, three teachers, Sally, Andrew, and Sahar, viewed anxiety as having both positive and negative effects, while the other two, Nadine and Randa, mainly viewed anxiety as having negative effects on students in the EFL classrooms. Participants highlighted that FLA could positively affect students, motivating them and pushing them to work harder. Sally, for example, shared an example of one of her students who had FLA; however, it positively affected her, as she chose to learn the language to help her children. Sally added:

For her, being anxious and feeling uneasy is one of the reasons that pushed her to learn English in particular. She wanted to help her child, and she wanted her child not to depend on private tutors. She wanted to be part of her child's improvement.

Her language anxiety was coupled with intrinsic motivation, and as a result, she was motivated and performed better in class. Anxiety becomes negative, however, when it impedes students' development and participation in class. Randa and Nadine viewed anxiety to mainly have negative effects on students in this specific context, and Nadine explained that anxiety “affects them [students] in a very negative way, and it might also impede their development at that point if it is a very severe case.” The examples and quotes shared by the instructors underline how FLA can have different effects on learners, highlighting the need for instructors to understand how FLA affects their students and how to handle its negative effects on the learners.

Teachers' effects on FLA levels

During the interviews, the participants were asked about the possible effect of teachers on FLA anxiety levels, and they mentioned that teachers could affect students' anxiety levels based on their attitude, rapport, and feedback strategies. They indicated that teachers could alleviate anxiety by providing students with a friendly and supportive learning environment where mistakes are tolerated and considered part of learning a foreign language. Teacher participants highlighted that being aggressive and unfriendly with students would increase FLA levels in the classroom. Andrew, for example, mentioned that he frequently uses the term “teachable moment” with his students when they make mistakes to highlight that mistakes are a way of learning and that students should not be ashamed or embarrassed of making mistakes. Nadine also referred to this point and added, “I think by showing them that we are not there to judge them, we can alleviate some of this anxiety.” Randa and Sally mentioned that feedback is one of the things that can raise students' anxiety levels if the teacher uses a sarcastic tone or if s/he over-corrects the students. Randa mentioned that teachers “should let few mistakes pass and just focus on the main things.” Awareness of how teachers can affect learners' anxiety levels is essential in creating an anxiety-free learning environment through being compassionate with the learners, acknowledging that mistakes are part of the learning process, and offering selective constructive feedback.

Teachers suffering from FLA

During the interviews, teachers were asked about the possibility of EFL teachers suffering from anxiety, and some of them were surprised at this question, as they believed that it is not possible for FL teachers to suffer from anxiety. Nadine claimed that FL teachers could not possibly suffer from anxiety, as “it would be very hard for someone who struggles with learning a language to become a language teacher unless they are very special.” Randa also expressed a similar opinion, but when she was asked again about having met a teacher who suffers from FLA, she mentioned one of her colleagues in the United States who refused to speak in English with foreigners even though she was an experienced English teacher. Andrew mentioned a related point, and he explained that it is not necessarily related to facing FLA issues inside the classroom but when speaking with natives or with a teacher with a higher proficiency level.

The other two participants, Sahar and Sally, explained that teachers could have FLA issues if they have a student who does not speak their L1. They feel obliged to speak English during the whole class period without possibly resorting to using the L1 to overcome some difficulties in the L2 classroom. Sahar, for example, mentioned that this could be anxiety-provoking, as the teacher might have to “stick to the L2 all the time without translating anything, and sometimes she [the teacher] cannot find the proper words.” Moreover, Sally indicated that teachers might face this issue while taking standardized tests but not in the classroom, as FLA would disappear once they start teaching.

Useful activities to deal with FLA

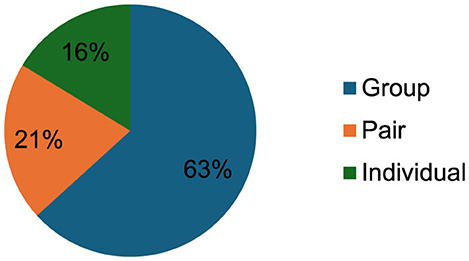

The interviewed teachers mentioned that among the different activities utilized in the classroom, group activities are the least anxiety-provoking, followed by pair and individual activities. The results are illustrated in the following Figure 4.

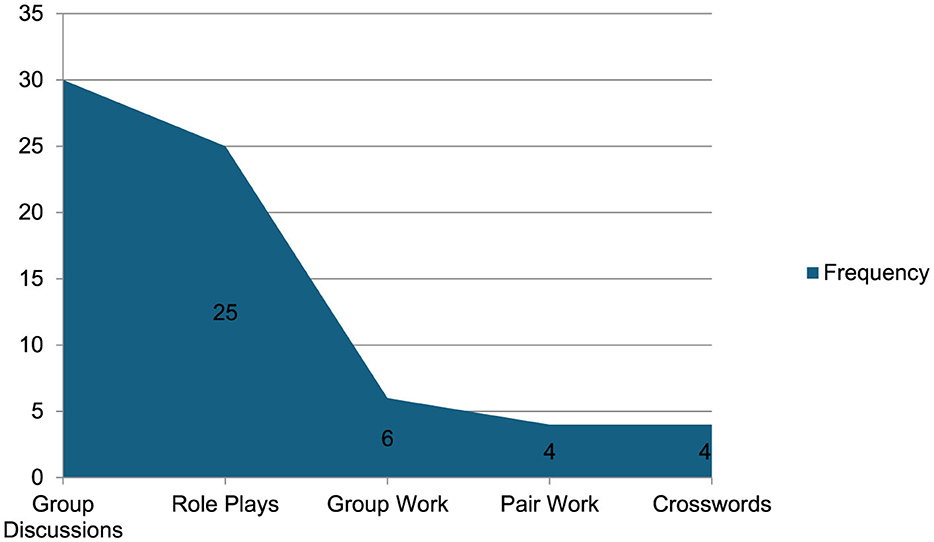

In the questionnaire, teachers were asked to choose the activities that they believed helped alleviate anxiety, and they mentioned using group discussions, role-plays, group and pair work, and crosswords. The activities that were most dominant and frequent were group discussions and role-plays. A text analysis software was used to count the frequency of the activities listed by the participants, and the results are presented in Figure 5.

In the interviews, the participants expressed similar opinions, explaining how group discussions, competitions, and other group activities are relaxing to students. They indicated that individual activities could be anxiety-provoking, as students might feel on the spot, and that is why the teachers suggested giving the students the chance to prepare their answers with their classmates to “lower the affective filter,” as Randa pointed out. Another teacher participant, Sahar, said: “[…] it is less threatening to speak to your peers, especially where it is a group work where one task is involved, and they have to complete something together.” Looking at the activities from another perspective, Andrew claimed that group work causes higher levels of anxiety, as it could be overwhelming for some students. He added that individual activities are more relaxing as students work independently and at their own pace.

The teachers also indicated that, at some point, anxiety could stem not from the activity itself but from how the teacher approaches it. For example, Sally indicated that sometimes, if the teacher is rigorous and serious, this can lead to a “demotivating atmosphere,” which raises students' anxiety and lowers their interest in participating in class.

Furthermore, Randa highlighted the role peers play in this issue and that sometimes if the students are not friends, this can lead to higher levels of anxiety. She also suggested administering a questionnaire on activity preference on the very first day of class so that she is aware of the activities they are more comfortable with. It is important to note that she mentioned that giving them the questionnaire was not a complete success, and she noted that “very few of them are honest with themselves, and they say I prefer to work by myself.” Such findings underline the need for teachers to experiment and use various activities while observing their effects on the learners and implementing any modifications needed to accommodate their needs.

FLA in the Egyptian classroom proved to be an intricate topic that affects both the learners and teachers. The results of the study underlined how teachers and learners are prone to FLA and how anxiety stems from different sources. For example, for teachers, it can stem from speaking to someone who speaks English as their first language. As for students, it can originate from the teachers' attitudes, types of activities used, or specific skills being practiced. Teachers' awareness of FLA was evident, and such awareness assisted the teachers in understanding the types of activities and feedback that can affect their learners' FLA levels. Such awareness is essential in supporting the learners and providing them with a welcoming and inclusive learning environment.

Discussion

Teachers in this study identified FLA as a significant factor impacting students' engagement and language learning. The results revealed that over 40% of teachers often notice FLA in their classrooms, with most of them associating this anxiety primarily with speaking skills. This aligns with previous studies that have shown that speaking is the most stressful aspect of learning a new language. Students, in particular, often worry about making mistakes, being judged, or struggling to find the right words quickly in real-time communication (Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre, 1995; Park and French, 2013). The Affective Filter Hypothesis (Krashen, 1985) explains this phenomenon, suggesting that heightened anxiety acts as a psychological barrier that hinders language input from becoming comprehensible intake, thereby limiting fluency and participation.

In the Egyptian context, where English is regarded as essential for career success and social status (Latif, 2018), FLA can be particularly evident. Many students feel pressured to perform well, which increases their anxiety. Teachers in this study also observed that certain speaking tasks—such as summarizing, presenting, and engaging in spontaneous conversations—tend to heighten students' anxiety. This observation aligns with findings in existing literature (e.g., Javaid et al., 2023; Shi and Zhang, 2023).

To address this issue, teachers can ease pressure by incorporating group discussions and structured speaking tasks that allow for preparation. Small changes—such as offering encouragement, pairing students up, and prioritizing communication over perfection—can make a big difference in reducing FLA and building students' confidence in using English.

The teachers' awareness of FLA and their ability to recognize its manifestations in students are crucial for creating a supportive learning environment. Such an environment, according to the teacher participants, can assist in reducing FLA levels, which conforms with Young's (1990) results on the need to provide a relaxing and positive learning environment. As this study shows, while most teachers are aware of FLA, not all are fully familiar with its nuances or its specific triggers. For instance, some teachers attributed students' anxiety to factors unrelated to language learning, such as personal characteristics or cultural reasons. This suggests that there is still a need for greater teacher training and awareness regarding the specific nature of FLA and its impact on language learning.

The study's findings also highlight teachers' dual role in reducing or increasing FLA in the classroom. Teachers' attitudes, feedback strategies, and the classroom environment they create significantly influence students' anxiety levels. Conversely, the study also found that teachers who are overly critical or fail to acknowledge students' anxiety can unintentionally increase FLA. This confirms that teachers can both alleviate and increase FLA in their EFL classes. These findings underscore the need for professional development programs to better equip teachers with strategies to recognize and address FLA.

Furthermore, a key finding of the study is the identification of specific language skills and sub-skills that are particularly anxiety-provoking for students. Speaking was identified as the most anxiety-inducing skill, with over 85% of teacher participants highlighting it as such. This finding is consistent with the existing literature, which considers speaking as the most challenging aspect of language learning, often due to the immediate nature of oral communication and the fear of public speaking (Park and French, 2013). However, the study also sheds light on other sub-skills, such as summarizing, expressing ideas in writing, and recognizing connected speech, which were identified as particularly anxiety-provoking by both students and teachers. These findings suggest that FLA is not limited to speaking but can permeate other aspects of language learning, depending on the context and the individual learner. Therefore, by providing students with clear strategies and tools for tackling these tasks, teachers can reduce the cognitive load and anxiety associated with them, thereby lowering the affective filter and facilitating more effective language learning.

This study explored FLA among teachers, particularly those who speak English as Second or Additional language. FLA among L2 teachers is relatively underexplored in the literature, yet it has significant implications for both teaching effectiveness and teacher wellbeing. The study found that while some teachers were initially surprised by the idea of teachers experiencing FLA, others acknowledged that it could occur, particularly when teachers feel pressured to exclusively use the L2 in the classroom or when interacting with native speakers. This finding aligns with Liu and Wu's (2021) research, which notes that non-native language teachers may experience anxiety due to perceived language inadequacies, especially when required to use the target language exclusively. This anxiety can, in turn, affect their teaching practices, potentially leading to a more rigid or less confident teaching style, which could increase FLA among students. One way to support teachers is to cater to their wellbeing through positive psychology, which refers to “the study of the conditions and processes that contribute to the flourishing or optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions” (Gable and Haidt, 2005, p. 103), and by fostering resilience and self-efficacy-key factors in reducing the negative impact of anxiety in language learning and teaching contexts (Rayyan et al., 2023). Utilizing positive psychology should not only assist in enhancing teachers' mood, focus, and optimism, and reducing their stress level but also it has professional benefits “like stronger teacher-student relationships and improved student confidence, engagement, and self-regulation” (Lo and Punzalan, 2025, p. 14). Assisting teachers in this manner assists in creating a more positive teaching and learning environments.

The study also explored the effectiveness of different classroom activities in alleviating FLA, with a particular focus on group vs. individual activities. The findings revealed that group activities, such as discussions and role plays, were generally perceived as less anxiety-provoking than individual tasks, which aligns with Koch and Terrell (1991). These findings on group activities alleviating FLA align with Toyama and Yamazaki's (2022) work on collectivist cultures/regions having higher levels of FLA, which clarifies and underscores teachers' preference for group activities to reduce FLA levels, as Egypt has a collectivist culture. This is also consistent with the Affective Filter Hypothesis, which suggests that collaborative activities can help lower the affective filter by providing a sense of shared responsibility and reducing the pressure on individual students (Krashen, 1985). However, the study also noted that the effectiveness of these activities in reducing anxiety depends on how the teacher implements them. For instance, a strict teacher may create a demotivating environment in the classroom, which could increase anxiety even during group activities. Moreover, the study found that peer dynamics play a crucial role in the success of group activities, with anxiety levels potentially rising if students are not comfortable with their group members.

In addition, considering the challenges faced by postgraduate and transitioning students, it is recommended that universities provide targeted English for Academic Purposes (EAP) support. Workshops, writing clinics, and language support services tailored to academic communication can greatly benefit students navigating unfamiliar academic environments and expectations.

Interestingly, one participant, Andrew, suggested that individual activities could be less anxiety-provoking for some students as they allow learners to work at their own pace without the pressure of group dynamics. This points to the importance of recognizing individual differences in FLA and suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective in alleviating anxiety. Teachers should consider offering a variety of activities and allowing students to choose the ones they are most comfortable with, thereby accommodating different learning styles and anxiety levels. These insights contribute to our understanding of FLA in EFL classrooms and pave the way for future research to explore intervention strategies that can more effectively address anxiety among students and teachers.

Conclusion

This study investigated teachers' awareness of the FLA phenomenon in Egyptian EFL classes in higher education. It also explored the effects of different activities on FLA levels and how teachers perceive the most and least anxiety-provoking skills, i.e., listening, reading, writing, and speaking. Teachers from various backgrounds, with differing levels of teaching experience, and who taught different courses were included in this study. Both quantitative and qualitative instruments, including teacher interviews and a questionnaire, were used to address the research questions.

The findings highlighted the importance of teachers' awareness of FLA in EFL classrooms to effectively address it and assist learners who struggle with this issue. Teachers demonstrated an awareness of FLA, at least to some extent, and recognized its effects on both the learning and teaching environments. The study also underscored the impact of different activities on FLA and the importance of teachers being aware of these activities and students‘ preferences.

Awareness of these factors can help teachers design lesson plans that include a variety of relaxing activities and games that are not anxiety-provoking for students. Also, with assessments representing an anxiety-provoking experience for many students, designing assessments that are engaging, collaborative, or gamified can transform potentially anxiety-inducing tasks into opportunities for positive effect and intrinsic motivation. The results also included various suggestions from teachers, supported by previous research, on how to handle FLA better, such as providing students with a friendly and motivating learning environment and using a variety of activities. In addition, the study emphasized the teacher's role in alleviating FLA and the various steps they can take to manage it. Moreover, teachers should use a variety of activities and adapt them to suit students' different learning styles. Discussing FLA with students could also be beneficial.

Focusing on teachers' wellbeing and using positive psychology is one of the suggestions to improve the teaching and learning environments in the classroom, offering teachers techniques on how to care for themselves to be able to care for their students and cater to their needs. Schools and universities can offer professional development sessions and workshops based on positive psychology to assist teachers in their journey toward a more positive teaching experience.

The present study included only interviews with teachers, and future research is suggested to include data from student interviews to provide a broader perspective on FLA. Future studies could also include a more diverse sample from different classes/courses in various universities, possibly comparing FLA levels at private and public universities in Egypt. Moreover, further comparisons could be made between teachers from different backgrounds and/or countries and students from different cultural and educational backgrounds to explore how they perceive FLA and its related variables.

Finally, this study has a few limitations; however, they do not significantly impact its validity. First, the sample size of 49 EFL instructors and five interviewees may limit generalizability. Nevertheless, since participants come from different universities and backgrounds, their perspectives still provide valuable insights into FLA in Egyptian EFL classrooms. Second, self-reported data may introduce bias, but the study mitigates this by triangulating questionnaire responses with in-depth interviews, enhancing reliability. Finally, the use of convenience sampling may reduce representativeness. However, the diverse backgrounds of participants and the study's exploratory nature help address this concern, paving the way for future research with larger, randomized samples.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the American University in Cairo, case number #2014-2015-64. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SA: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization. MA: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1614353/full#supplementary-material

References

Abushihab, I. (2024). The theory of multiple intelligences and its implications in teaching foreign languages: an analytical study. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 59, 44–51. doi: 10.35741/issn.0258-2724.59.1.4

Algazo, M. (2023). Functions of L1 use in the L2 classes: Jordanian EFL teachers' perspectives. World J. Engl. Lang. 13, 1–8. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v13n1p1

Algazo, M. (2024). First language use in the second language classroom in public secondary schools in Jordan: Policy and practice (Unpublished PhD thesis, Western University).

Alla, L., Tamila, D., Neonila, K., and Tamara, G. (2020). Foreign language anxiety: classroom vs distance learning. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 8, 6684–6691. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2020.081233

Al-Shahwan, R. (2024). The attitudes of students at the translation department at Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan towards using translation from English language into Arabic language by the instructors as a medium of instruction in translation courses. Al-Zaytoonah Univ. Jordan J. Human Soc. Stud. 5, 176–190. doi: 10.15849/ZJJHSS.240330.09

Alzobidy, S., Al-qadi, M. J., Belhassen, S. B., Mohammad, I., Naser, M., Ahmad, S., et al. (2024). The effect of multi-media usage in cognitive demands for teaching EFL among jordanian secondary school learners. World J. English Lang. 14, 471–481. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v14n3p471

Attia, S. (2023). Hiring criteria and employability of ESL/EFL instructors in the TESOL job market in Canada and the United Arab Emirates (PhD thesis, University of Western, Ontario, Canada).

Attia, S. S. (2015). Foreign language anxiety: perceptions and attitudes in the Egyptian ESL classroom (MA thesis, American University in Cairo, Cairo, Egypt). Available at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/85/ (Accessed August 11, 2025).

Ay, S. (2010). Young adolescent students' foreign language anxiety in relation to language skills at different levels. J. Int. Soc. Res. 3, 83–91.

Botes, E., Dewaele, J.-M., and Greiff, S. (2020). The foreign language classroom anxiety scale and academic achievement: an overview of the prevailing literature and a meta-analysis. J. Psychol. Lang. Learn. 2, 26–56. doi: 10.52598/jpll/2/1/3

Bruen, J., and Kelly, N. (2017). Using a shared L1 to reduce cognitive overload and anxiety levels in the L2 classroom. Lang. Learn. J. 45, 368–381. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2014.908405

Chan, S., and Lo, N. (2022). “Is extra English for academic purposes (EAP) support required for degree holders pursuing master programmes in less familiar fields?,” in Annual Conference of Hong Kong Association for Educational, Communications and Technology (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 43–59. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-9217-9_4

Cheng, Y. C. (2018). The effect of using board games in reducing language anxiety and improving oral performance (MA thesis, the University of Mississippi). Available online at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/899 (Accessed August 11, 2025).

Clymer, E., Alghazo, S., and Naimi, T. (2020). CALL, native-speakerism/culturism, and neoliberalism. Interchange 51, 209–237. doi: 10.1007/s10780-019-09379-9

Gable, S. L., and Haidt, J. (2005). What (and why) is positive psychology? Rev. General Psychol. 9, 103–110. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.103

Gacs, A., Goertler, S., and Spasova, S. (2020). Planned online language education versus crisis-prompted online language teaching: lessons for the future. Foreign Lang. Ann. 53, 380–392. doi: 10.1111/flan.12460

Gannoun, H., and Deris, F. D. (2022). Teaching anxiety in foreign language classroom: a review of literature. Arab. World Engl. J. 14, 379–393. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol14no1.24

Gürsoy, E., and Akin, F. (2013). Is younger really better? Anxiety about learning a foreign language in Turkish children. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 41, 827–841. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2013.41.5.827

Halimi, F., Daniel, C. E., and AlShammari, I. A. (2019). The manifestation of English learning anxiety in Kuwaiti ESL classrooms and its effective reduction. J. Classroom Interaction 54, 60–76.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., and Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Lang. J. 70, 125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Huang, Y. W. (2014). Self and language anxiety. Engl. Lang. Literat. Stud. 4, 66–77. doi: 10.5539/ells.v4n2p66

Javaid, Z. K., Andleeb, Z., and Rana, S. (2023). Psychological perspective on advanced learners' foreign language-related emotions across the four skills. Voyage J. Educ. Stud. 3, 191–207. doi: 10.58622/vjes.v3i2.57

Jin, Y., De Bot, K., and Keijzer, M. (2017). Affective and situational correlates of foreign language proficiency: a study of Chinese university learners of English and Japanese. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 7, 105–125. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.6

Jin, Y., Dewaele, J. M., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2021). Reducing anxiety in the foreign language classroom: a positive psychology approach. System 101, 1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102604

Jin, Y., Zhang, L. J., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2020). Contracting students for the reduction of foreign language classroom anxiety: an approach nurturing positive mindsets and behaviors. Front. Psychol. 11:1471. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01471

Jin, Y. X., and Dewaele, J.-M. (2018). The effect of positive orientation and perceived social support on foreign language classroom anxiety. System 74, 149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.01.002

Jugo, R. R. (2020). Language anxiety in focus: the case of Filipino undergraduate teacher education learners. Educ. Res. Int. 2020, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2020/7049837

Kobul, M. K., and Saraçoglu, I. N. (2020). Foreign language teaching anxiety of non-native pre-service and in-service EFL teachers. J. Hist. Cult. Art Res. 9, 350–365. doi: 10.7596/taksad.v9i3.2143

Koch, A., and Terrell, T. D. (1991). “Affective reactions of foreign language students to natural approach activities and teaching techniques,” in Language Anxiety: From Theory and Research to Classroom Implications, eds. E. K. Horwitz and D. J. Young (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall), 109–126.

Lai, W., and Wei, L. (2019). A critical evaluation of Krashen's monitor model. Theory Prac. Lang. Stud. 9, 1459–1464. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0911.13

Latif, M. M. A. (2018). English language teaching research in Egypt: trends and challenges. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 39, 818–829. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2018.1445259

Lichtman, M. (2013). Qualitative Research in Education: A User's Guide, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Liggett, T. (2014). The mapping of a framework: critical race theory and TESOL. Urban Rev. 46, 112–124. doi: 10.1007/s11256-013-0254-5

Liu, H. J., and Chen, T. H. (2013). Foreign language anxiety in young learners: how it relates to multiple intelligences, learner attitudes, and perceived competence. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 4, 932–938. doi: 10.4304/jltr.4.5.932-938

Liu, M., and Wu, B. (2021). Teaching anxiety and foreign language anxiety among Chinese college English teachers. SAGE Open 11, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/21582440211016556

Lo, N. P. K. (2022). Case study of EAP assessments and the affective advantages of student enjoyment in Hong Kong higher education. J. Asia TEFL 19, 1088–1097. doi: 10.18823/asiatefl.2022.19.3.24.1088

Lo, N. P. K., and Punzalan, C. H. (2025). The impact of positive psychology on language teachers in higher education. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Prac. 22, 1–19. doi: 10.53761/5ckx2h71

Luo, H. (2018). Predictors of foreign language anxiety: a study of college-level L2 learners of Chinese. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 41, 3–24. doi: 10.1515/cjal-2018-0001

Machida, T. (2015). Japanese elementary school teachers and English language anxiety. TESOL J. 7, 40–66. doi: 10.1002/tesj.189

MacIntyre, P. D. (1995). How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply to Sparks and Ganschow. Modern Lang. J. 79, 90–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05418.x

MacIntyre, P. D. (1998). “Language anxiety: a review of the research for language teachers,” in Affect in Foreign Language and Second Language Learning, ed. D. J. Young (Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill), 24–45.

Merç, A. (2011). Sources of foreign language student teacher anxiety: a qualitative inquiry. Turkish Online J. Qual. Inquiry 2, 80–94. doi: 10.17569/tojqi.08990

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Morrison, K., and Lui, I. (2000). Ideology, linguistic capital and the medium of instruction in Hong Kong. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 21, 471–486. doi: 10.1080/01434630008666418

Öztürk, G., and Gürbüz, N. (2013). The impact of gender on foreign language speaking anxiety and motivation. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 70, 654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.106

Park, G. P., and French, B. F. (2013). Gender differences in the foreign language classroom anxiety scale. System 41, 462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2013.04.001

Phillipson, R. (2017). Myths and realities of ‘global' English. Lang. Policy 16, 313–331. doi: 10.1007/s10993-016-9409-z

Ran, C., Wang, Y., and Zhu, W. (2022). Comparison of foreign language anxiety based on four language skills in Chinese college students. BMC Psychiatry 22, 1–558. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04201-w

Rayyan, M., Zidouni, S., Abusalim, N., and Alghazo, S. (2023). Resilience and self-efficacy in a study abroad context: a case study. Cogent Educ. 10, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2023.2199631

Russell, V. (2020). Language anxiety and the online learner. Foreign Lang. Ann. 53, 338–352. doi: 10.1111/flan.12461

Schaub, M. (2000). English in the Arab republic of Egypt. World Engl. 19, 225–238. doi: 10.1111/1467-971X.00171

Schneider, E. W. (2018). “English and colonialism,” in The Routledge Handbook of English Language Studies (Abingdon: Routledge), 42–58. doi: 10.4324/9781351001724-4

Shi, Z. T., and Zhang, R. H. (2023). Investigating Chinese university-level L2 learners' foreign language anxiety in online English classes. Open J. Modern Linguist. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.4236/ojml.2023.131001

Toyama, M., and Yamazaki, Y. (2022). Foreign language anxiety and individualism-collectivism culture: a top-down approach for a country/regional-level analysis. SAGE Open 12, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/21582440211069143

Tüm, D. Ö. (2019). Foreign language anxiety among prospective language teachers. Folklor/Edebiyat 25, 317–332. doi: 10.22559/folklor.946

University of Cambridge (n.d.). Conflicting Chronologies: Britain in Egypt. Available at: https://www.whipplelib.hps.cam.ac.uk/special/exhibitions-and-displays/conflicting-chronologies/britain-egypt (Accessed August 11, 2025).

Young, D. J. (1990). An investigation of students' perspectives on anxiety and speaking. For. Lang. Ann. 23, 539–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.1990.tb00424.x

Keywords: Foreign language anxiety (FLA), English as a foreign language (EFL), teachers' perceptions, classroom anxiety, class activities

Citation: Attia S and Algazo M (2025) Foreign language anxiety in EFL classrooms: teachers' perceptions, challenges, and strategies for mitigation. Front. Educ. 10:1614353. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1614353

Received: 18 April 2025; Accepted: 25 July 2025;

Published: 22 August 2025.

Edited by:

Meenakshi Sharma Yadav, King Khalid University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Noble Lo, Lancaster University, United KingdomYinxing Jin, Hainan Normal University, China

Vegneskumar Maniam, University of New England, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Attia and Algazo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Muath Algazo, bS5hbGdhem9AenVqLmVkdS5qbw==

Shaden Attia1

Shaden Attia1 Muath Algazo

Muath Algazo