- 1Department of Psychology, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA, United States

- 2Department of Social Welfare, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Objective: This study examined the associations between discrimination, social anxiety, and self-esteem among racially and ethnically minoritized college students. Additionally, we explored how ethnic-racial identity affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition influenced these relationships.

Method: The sample consisted of 3,257 Black, Latinx, and Asian American college students (Mage= 19.94) from 30 universities in the United States who participated in an online multi-university study.

Results: Findings revealed that discrimination was associated with increased social anxiety but not self-esteem. We also discovered that school ethnic-racial composition played a role in the relationship between discrimination and self-esteem when diversity was both high and low.

Conclusion: These findings highlight the importance of understanding the role of school diversity in students' mental health and provide valuable insight for school personnel and policy makers who are dedicated to promoting more supportive school environments.

Introduction

Attending college is widely seen as a major milestone in the United States. Despite being an important and exciting time for many students, college can also introduce race-related stressors that can affect various aspects of mental health (e.g., social anxiety) and psychological wellbeing (e.g., self-esteem; Schmitt et al., 2014) among students from ethnically and racially minoritized groups (e.g., Black, Latinx, and Asian American). Notably, cultural assets (e.g., family ethnic socialization and ethnic-racial identity) can counteract the harmful effects of race-related stressors, such as discrimination, and protect students' developmental and psychological outcomes (Neblett et al., 2012). Additionally, the ethnic-racial composition of a student's university can play a role in how discrimination relates to mental health (Bellmore et al., 2004) and psychological wellbeing (Brittian et al., 2013a). Guided by an integrative developmental model, which emphasizes how racially and ethnically minoritized individuals might be more susceptible to discrimination (Castro et al., 2024; Coll et al., 1996), we examined how discrimination relates to social anxiety and self-esteem among ethnically and racially minoritized college students in the United States, and how family ethnic socialization, ethnic-racial identity, and school ethnic-racial composition might influence these relationships.

Discrimination as a risk factor

For many ethnically and racially minoritized college students, discrimination, the unjust or prejudicial treatment of individuals based on ethnic or racial group membership, is a prevalent and potent stressor (Bravo et al., 2023). At universities where most students identify as White, for instance, ethnically and racially minoritized students often report experiencing both interpersonal and vicarious discrimination (Jochman et al., 2019), facing daily microaggressions (Blume et al., 2012; Mills, 2020), being ignored in the classroom due to their ethnic or racial identities (Farber et al., 2020), or hearing other students using hostile slurs (Lui and Anglin, 2022). Unfortunately, these problems even persist at minority-serving institutions (Flores et al., 2024), with one study documenting racial stereotyping faced by Asian students and Latinx students being called ethnic slurs (Palmer and Maramba, 2015). Additionally, as college classrooms have extended to virtual learning spaces, experiences of racial discrimination online have also increased sharply (Cavalhieri et al., 2024; Lu and Wang, 2022).

The prevalence of this mistreatment is especially problematic since exposure to discrimination is detrimental to health and wellbeing (Bhui, 2016; Pascoe and Smart Richman, 2009). Research has linked discrimination to a host of physical and psychological risks, including elevated depressive symptoms (Farber et al., 2020; Hwang and Goto, 2008; Stein et al., 2019), poorer sleep quality (Bethea et al., 2019; Hoggard and Hill, 2016), lower self-esteem (Becerra et al., 2021), higher blood pressure (Steffen et al., 2003), increased irritability (Chao et al., 2012), substance abuse (Landrine and Klonoff, 2000; Metzger et al., 2018), heightened anxiety (Gaylord-Harden and Cunningham, 2009; Jochman et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2020; Pachter et al., 2018) and suicidal ideation (Hollingsworth et al., 2017; Hong et al., 2018). For ethnically and racially minoritized students, prior research reveals that hostile or negative campus climates marked by discrimination can heighten students' vigilance and affect their development including psychological wellbeing (Koo, 2021). Importantly, discriminatory treatment and the significant social, financial, and academic challenges of higher education can compound these health risks and outcomes for ethnically and racially minoritized students. As such, characterizing the effects of discrimination on indices of wellbeing may help clarify and combat the contextual risk factors that undermine the success of ethnically and racially minoritized students.

Social anxiety

Discrimination affects health and wellbeing, including elevating anxiety. Such adverse effects have been observed across different forms of discrimination (e.g., subtle, overt, institutional, vicarious; MacIntyre et al., 2023) and among diverse ethnic and racial groups (e.g., Black, Latinx, Asian; Blume et al., 2012; Bravo et al., 2021; Carter and Forsyth, 2010; Chen et al., 2014; Hwang and Goto, 2008; Martinez et al., 2022). However, much of this work defines anxiety as a broad psychopathological construct. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, anxiety consists of distinct subcomponents, such as generalized anxiety, panic disorder, specific phobia, and social anxiety (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). While research has documented consistent links between discrimination and anxiety, more broadly, there has been relatively less work exploring the effects of discrimination on specific facets of anxiety, like social anxiety. This is consequential as discrimination is a form of social stress that conditions how future social interactions are experienced. Whereas, generalized anxiety consists of enduring worry about a range of everyday situations and life events, social anxiety is characterized by a chronic, persistent fear of being watched and judged by certain types of people (Bögels et al., 2010). As such, it is conceivable that adverse social experiences like discrimination may elevate social anxiety symptoms, in particular. For instance, a recent study of Black young adults found discrimination was predictive of social anxiety but not generalized anxiety. This is especially notable because individuals with social anxiety, even when compared to individuals with other anxiety disorders (Lochner et al., 2003; Norton et al., 1996), experience a host of social, occupational, and personal challenges that can impair quality of life (Dryman et al., 2016).

The current study seeks to build on prior work by examining the effects of ethnic discrimination on social anxiety among historically underrepresented racial/ethnic college students (e.g., Black, Latinx, and Asian). Ethnically and racially minoritized individuals exhibit higher levels of social anxiety relative to their White peers (Lesure-Lester and King, 2004). Moreover, social anxiety can be especially detrimental during late adolescence and emerging adulthood, developmental periods already characterized by challenging social and emotional transitions. As such, a comprehensive understanding of the effect of discrimination on social anxiety represents a key step in promoting the success and wellbeing of ethnically and racially minoritized students in higher education.

Self-esteem

Self-esteem, defined as an individual's variability in how positively or negatively they perceive themselves (Rosenberg, 1965), is an important component of college students' self-concept that is also linked to psychosocial and academic adjustment. Self-esteem tends to increase in the transition from adolescence into adulthood, and for ethnically and racially minoritized college students, higher self-esteem is predictive of positive developmental outcomes, such as academic adjustment (Grant-Vallone et al., 2003) and health (Cheng et al., 2020; Corning, 2002). As such, identifying stressors detrimental to self-esteem is critical to supporting ethnically and racially minoritized students' success in higher education.

One such stressor known to impact self-esteem negatively is discrimination. Previous work has consistently linked discrimination exposure to reduced self-esteem in Black (Utsey et al., 2000), Latinx (Becerra et al., 2021), and Asian American (Wei et al., 2013) college students. Importantly, these studies recruited samples from specific regions in the United States, limiting the generalizability of their findings. The current study builds on this work by examining the relationship between ethnic discrimination and self-esteem in a sample of Black, Latinx, and Asian American college students recruited from multiple regions in the United States.

Protective and contextual factors

Ethnic-racial identity

Ethnic-racial identity, a multifaceted construct that is comprised of one's ability to explore, resolve, and affirm one's identity in relation to their ethnic-racial group (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004), is known to promote healthy development (Yip et al., 2019). Oftentimes, research explores the developmental influences of ethnic-racial identity (i.e., exploration, resolution, and affirmation) in tandem. However, an individual examination of these domains may clarify their potentially unique contributions to the link between risk factors and developmental outcomes. Therefore, the current study focuses on ethnic-racial identity affirmation, which has been examined at a lower frequency compared to exploration and resolution.

In many cases, affirmation, or the extent to which one feels negatively or positively about their ethnic-racial identity in relation to their ethnic-racial group (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) has been found to promote positive developmental outcomes among ethnically and racially minoritized populations (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2020). For example, in a sample of Asian college students, affirmation was positively associated with psychological wellbeing (Iwamoto and Liu, 2010) and self-esteem (Umaña-Taylor and Shin, 2007). Affirmation has also been linked to lower anxiety and depressive symptoms among ethnically and racially diverse young adults (Brittian et al., 2013b). Importantly, there has been less work characterizing how affirmation influences mental health and psychological wellbeing in the context of discrimination. Accordingly, the current study aims to explore if ethnic-racial affirmation might buffer the influence of discrimination on social anxiety and self-esteem.

Family ethnic socialization

Family ethnic socialization, the process by which caregivers and families make meaningful efforts to teach their children about their ethnic group's culture and values (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009), emerges as early as infancy and continues to play an important role into adolescence and young adulthood (Loyd et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2020). In this regard, families socialize their children in a variety of ways, including speaking in their native language and taking their children to events that reflect their culture, which allows for youth to learn to be both prideful and aware of their position in society (Hughes et al., 2006). Family ethnic socialization oftentimes contributes to positive ethnic-racial identity development (Hughes et al., 2006). For example, in a sample of Black adolescents, family ethnic socialization practices were positively related to ethnic-racial identity (Peck et al., 2014). Given that family ethnic socialization has been shown to predict positive developmental outcomes for adolescents, it is also important to learn if this positive association continues into emerging adulthood, given the decreasingly influential role family members play as adolescents enter adulthood.

Few studies among ethnically and racially minoritized college-going individuals investigate family's important role. In a sample of Latina college students, family socialization was a protective factor in the face of discrimination (Sanchez et al., 2018). In cases where discrimination might be more visible, some young adults rely heavily on their families for emotional and social support, which could be a possible avenue for ethnic socialization to occur (Luyckx et al., 2006). Here, we aim to explore the potential for family ethnic socialization to buffer the influence of discrimination on social anxiety and self-esteem among college students.

School ethnic-racial composition

In an educational context, the ethnic and racial makeup of a given academic institution might affect student's developmental and academic outcomes. Several studies have identified associations between the ethnic-racial composition of a school and the mental health and psychological wellbeing of its students. For example, adolescents (i.e., Black and Latinx students) feel less socially anxious and lonely in schools with more ethnic and racial diversity (Bellmore et al., 2004). Additionally, higher levels of ethnic and racial diversity are associated with lower levels of discrimination among adolescents (Bellmore et al., 2012). Notably, much of the research examining the effects of school ethnic-racial composition on psychological wellbeing has focused on adolescents and has not considered whether these differences persist in the context of discriminatory experiences among college students.

For college students, the ethnic-racial composition of academic institutions might amplify the effect of discriminatory experiences on students' social anxiety and self-esteem. Given previous work documenting how more diversity within a school context has been found to be associated with better mental health outcomes for adolescents (DuPont-Reyes and Villatoro, 2019), it is important that we also examine these associations in the context of discrimination. Limited research examines the potentially protective nature of ethnic-racial school composition for college students in the face of discrimination. The current study will fill this gap by investigating the role of ethnic-racial school composition in the association between discrimination, social anxiety, and self-esteem among ethnically and racially minoritized college students.

Gender differences

Gender may also play an important role in shaping students' experiences with discrimination, sociocultural context, and psychological outcomes. Although much of the existing literature focuses on adolescents, some findings suggests that women report higher levels of family ethnic socialization compared to their peers which would be due to gender norms and family involvement (Umaña-Taylor and Fine, 2004). In terms of psychological outcomes such as social anxiety and mental health, college women reported higher anxiety related symptoms while men reported higher levels of self-esteem (Norberg et al., 2010; Zuckerman et al., 2016). Given these patterns, it is important to continue to explore gender differences to better understand how gender plays a role with racialized experiences, sociocultural context, and psychological outcomes among college students.

Current study

This study explored the influence of discrimination on social anxiety and self-esteem among historically underrepresented college students. Additionally, we explored the potential moderating role of ethnic-racial identity affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition. Two research questions guide this study: (1) How does discrimination affect social anxiety and self-esteem? and (2) Do affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition influence those associations? We hypothesized that discrimination would be associated with increased social anxiety and reduced self-esteem. Additionally, we hypothesized that affirmation and family ethnic socialization would buffer the effect of discrimination on social anxiety and self-esteem. Finally, we hypothesized that the influence of discrimination on social anxiety and self-esteem would differ as a function of school ethnic-racial composition.

Method

Participants and procedure

The sample for this study consisted of 3,257 undergraduate students (Mage= 19.94, SD = 1.99, 18–29 years, 72% women) from 30 universities in the United States who participated in the Multisite University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC; Weisskirch et al., 2013). The different university sites included research-intensive universities, regional comprehensive universities, private institutions, and liberal arts colleges. Participants in the current study identified as 44% Latinx/Hispanic, 30% Asian/Asian American, and 26% Black/African American. Participants reported their family income, with 29% below $30k, 25% between $30k and $50k, 27% between $50k and $100k, 15% over $100k, and 3% did not report an income. Prior to participating in this study, all participants provided informed consent. This consent was obtained through an online consent form distributed by their respective instructors. The study itself consisted of an online survey, with participants dedicating ~90 min to complete. Participants were made aware that their participation was completely voluntary (for full study methodology, see Castillo and Schwartz, 2013; Weisskirch et al., 2013). Each university's Institutional Review Board approved the procedures for data collection and participant recruitment. Students received course credit for their participation in the form of extra credit or experimental credit for participating in this research study. The dataset analyzed for this study is not publicly available but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Measures

Discrimination

Discrimination was measured using nine items from the perceived discrimination subscale of the Scale of Ethnic Experiences (SEE; Malcarne et al., 2006). Participants were asked to share their views of America's perception and treatment of their respective ethnic groups. Sample items included “In America, the opinions of people from my ethnic group are treated less important than those of other ethnic groups” and “My ethnic group is often criticized in this country.” Participants rated the items on a five-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, with higher values reflecting higher levels of discrimination. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha for this scale was 0.82. The SEE perceived discrimination subscale has shown evidence of construct and convergent validity across diverse racial and ethnic groups with significant associations with ethnic identity in the original validation study (Malcarne et al., 2006).

Ethnic-racial identity affirmation

Ethnic-racial identity affirmation was measured using six items from the subscale of the Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). This scale measured participants' feelings and sense of belonging toward their ethnic group. Sample items included “If I could choose, I would prefer to be of a different ethnicity” and “I am not happy with my ethnicity.” Participants' responses were scored with a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = does not describe me at all to 4 = describes me very well. Items were reverse scored, such that higher values reflected higher levels of affirmation. In this study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.86, consistent with previous studies (Brittian et al., 2013b). The affirmation subscale has also demonstrated construct and convergent validity in diverse samples (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004).

Family ethnic socialization

Family ethnic socialization was measured using the 12-item Familial Ethnic Socialization measure (FES; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Items in the scale included a series of statements asking participants about different ways their families might have introduced or taught them about their ethnic/cultural background. Sample items included “My family celebrates holidays that are specific to my ethnic/cultural background” and “My family listens to music sung or played by artists from my ethnic/cultural background.” Participants responded using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much, with higher values reflecting higher levels of family ethnic socialization. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.93. The FES scale has demonstrated a strong construct and convergent validity in relation to ethnic identity in the original validation study (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004).

School ethnic-racial composition

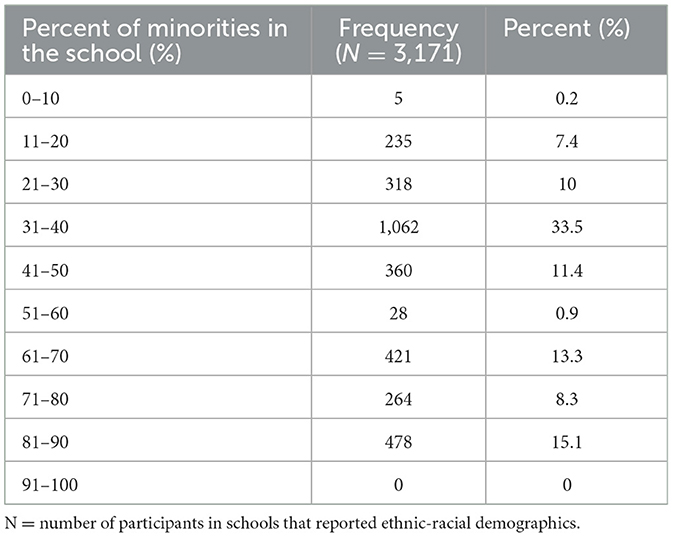

School ethnic-racial composition was collected during the Fall of 2008 and publicly reported by each university's Office of Institutional Research. A proportion variable was created for the proportion of ethnic-racial minority students (e.g., Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian/Pacific Islander), including international students and excluding non-reporters, by dividing the number of ethnic-racial minority students by the total number of enrolled students. Some universities did not publicly report ethnic-racial demographics. In this study, scores ranged from 0.08 to 0.83, with higher values reflecting a higher proportion of ethnic-racial minority students enrolled in each university (see Table 1).

Social anxiety

Social anxiety was measured using the 19-item Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick and Clarke, 1998). Participants were asked to consider how they interact with other people and the way it makes them feel. Sample items included “I find it easy to think of things to talk about” and “I feel tense when I am alone with just one other person.” Participants rated the items using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, with higher values reflecting higher levels of social anxiety. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.93. The SIAS has demonstrated strong construct and convergent validity, with previous research showing significant relationships with related constructs (Rodebaugh et al., 2006).

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965). This 10-item scale included a series of statements assessing participants' confidence in their self-worth. Sample items included “I am able to do things as well as most other people” and “I certainly feel useless at times.” Participants rated the items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, with higher values reflecting higher levels of self-esteem. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha for the self-esteem scale was 0.88. The RSES has demonstrated a strong construct and convergent validity with related measures across adolescent and adult populations (Gray-Little et al., 1997; Robins et al., 2001).

Analytic plan

We used R 4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2021) software to analyze data for the proposed research questions. Before conducting main analyses, we examined whether the data met assumptions needed for linear regression and interaction models. All continuous variables were assessed for normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity. To address multicollinearity issues, all variables of interest were mean centered prior to interaction analysis (Aiken and West, 1991). Missingness across study variables ranged from 2.6% (e.g., gender) to 21.8% (e.g., self-esteem). To assess whether the data were missing at random (MAR), we conducted a series of logistic regressions predicting missingness (0 = missing, 1 = present) on the outcome variables (i.e., self-esteem and social anxiety) using all primary predictors and covariates. For the self-esteem outcome, missingness was significantly associated with gender (B = 0.022, p = 0.02), such that men were more likely than women to have missing data. Additionally, family ethnic socialization predicted missingness on self-esteem (B = −0.01, p = 0.03), indicating that participants reporting higher levels of family ethnic socialization were also more likely to have missing data on this outcome. No predictors or covariates significantly predicted missingness for the social anxiety variable (ps > 0.05). Based on these findings, we concluded that there were no strong systematic patterns of attrition that would bias the results, and we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation to handle missing data in all models (Enders, 2010).

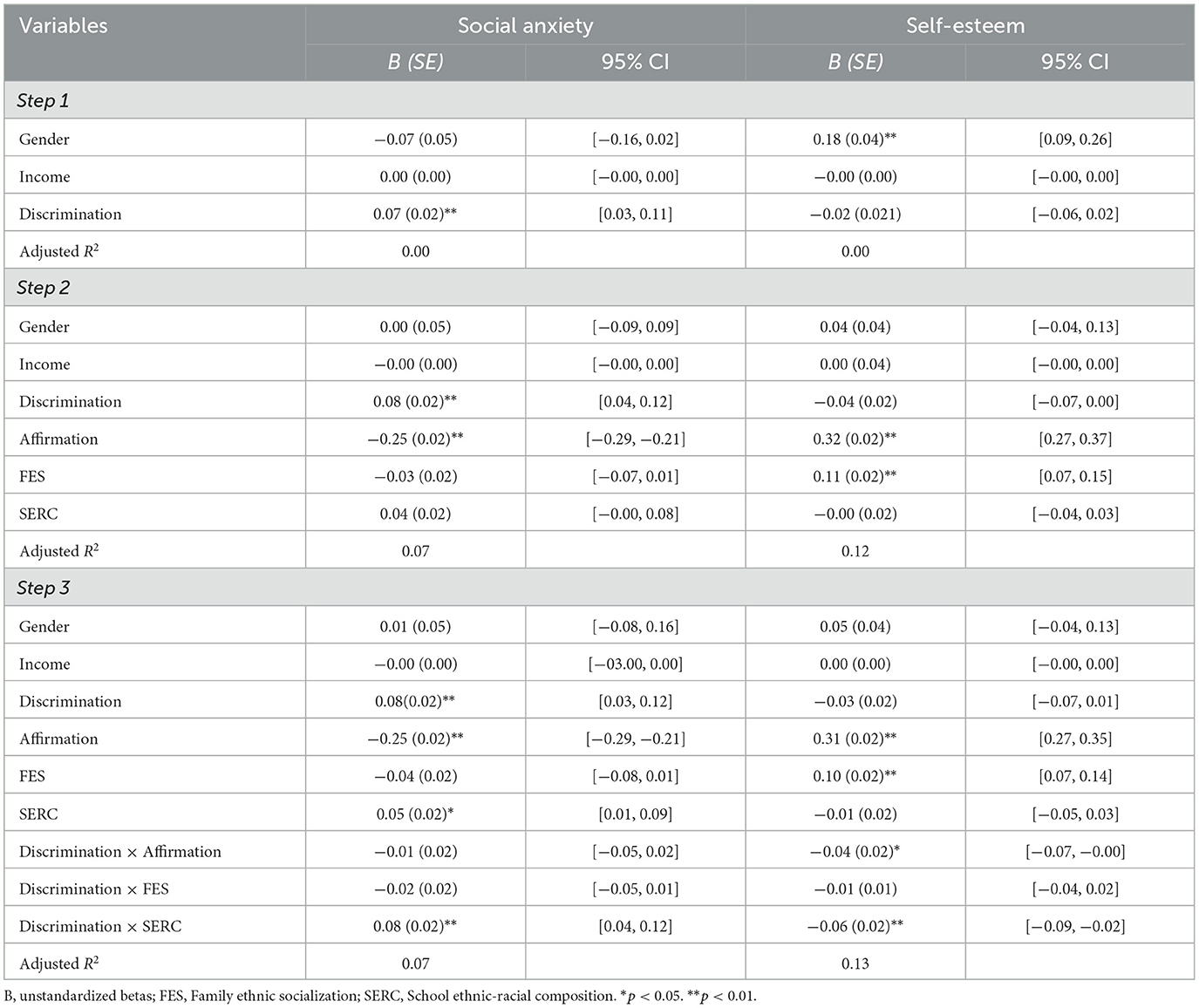

Hierarchical linear regressions were tested for each outcome of interest (i.e., social anxiety and self-esteem). First, we tested the main effect of discrimination on social anxiety and self-esteem. Second, we tested the main effects of discrimination, ethnic-racial identity affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition on social anxiety and self-esteem. Third, we tested the interactive effects of discrimination with ethnic-racial identity affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition on social anxiety and self-esteem. To limit the influence of confounding variables, all tested models controlled for gender and income. Supplemental analyses were conducted for all models with and without university site included as a covariate; results were substantively unchanged. Statistical significance was evaluated using an alpha level of 0.05. We rejected the null hypotheses when p-values were < 0.05. For interaction terms, simple slopes were probed when interactions were significant.

Results

Preliminary analyses

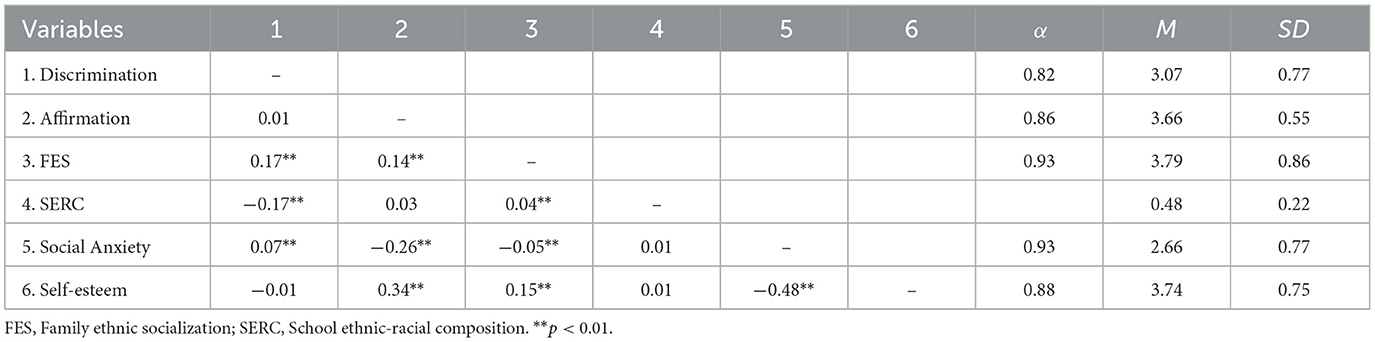

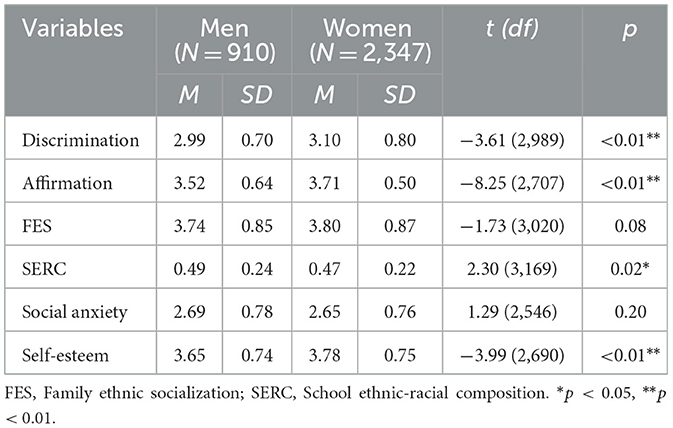

Descriptive analyses were conducted for all variables of interest (Table 2). Bivariate correlations revealed that discrimination was associated with higher levels of social anxiety (r = 0.07, p < 0.01), as well as higher levels of family ethnic socialization (r = 0.17, p < 0.01) and lower levels of school ethnic-racial composition (r = −0.17, p < 0.01). Additionally, independent samples t-tests (Table 3) revealed that, on average, women (M = 3.10, SD = 0.80) reported significantly higher levels of discrimination relative to men (M = 2.99, SD = 0.70); t(2, 989) = 3.61, p < 0.01. Women (M = 3.71, SD = 0.50) also reported significantly higher ethnic-racial identity affirmation compared to men (M = 3.52, SD = 0.64); t(2, 707) = −8.25, p < 0.01. Lastly, women (M = 3.78, SD = 0.75) reported significantly higher self-esteem compared to men (M = 3.64, SD = 0.74); t(2, 690) = −3.99, p < 0.01.

Hierarchical regressions

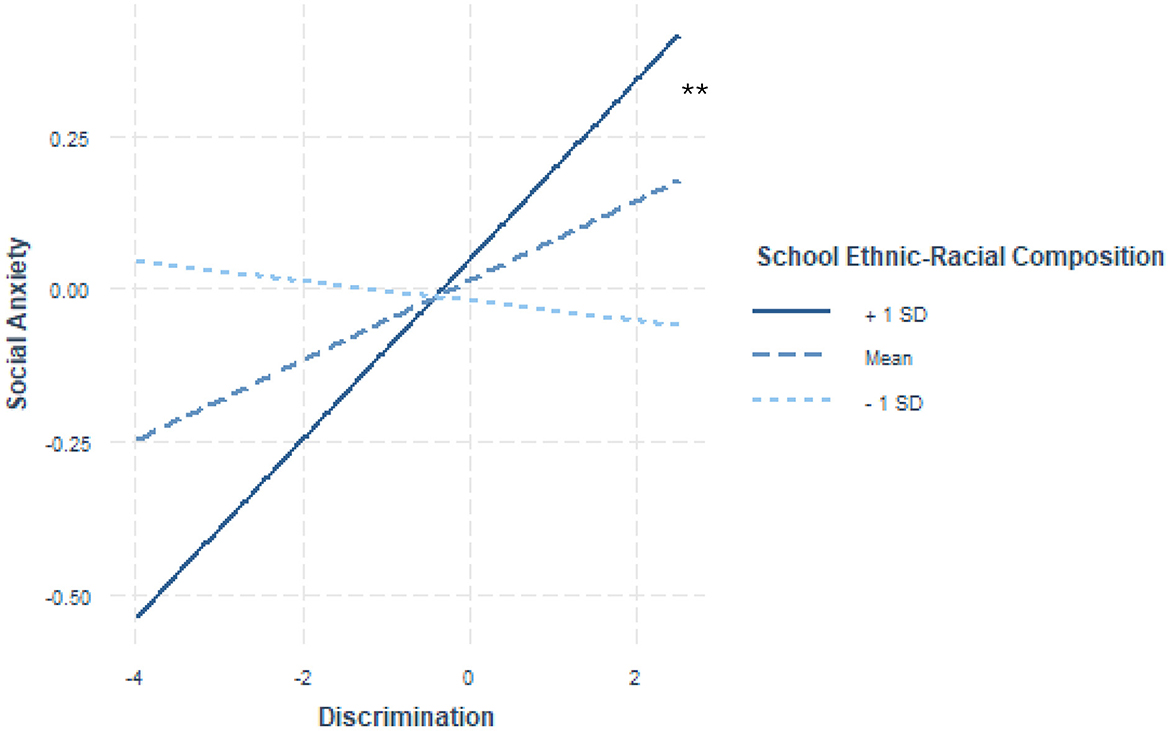

Two hierarchical regressions were conducted for each outcome variable (Table 4). The first model examined social anxiety while controlling for gender and income. Discrimination positively predicted social anxiety (B = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < 0.01), such that higher levels of discrimination were associated with more social anxiety. A main effect of ethnic-racial identity affirmation emerged, such that greater affirmation predicted lower levels of social anxiety (B = −0.25, SE = 0.02, p < 0.01). In addition, there was a significant interaction between discrimination and school ethnic-racial composition which positively predicted social anxiety (B = 0.08, SE = 0.02, p < 0.01). Simple slopes analysis revealed that in universities where there was a higher proportion of minority students, discrimination predicted higher social anxiety (B = 0.15, SE = 0.03, p < 0.01, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interaction plot for social anxiety. School ethnic-racial composition by discrimination. **p < 0.01.

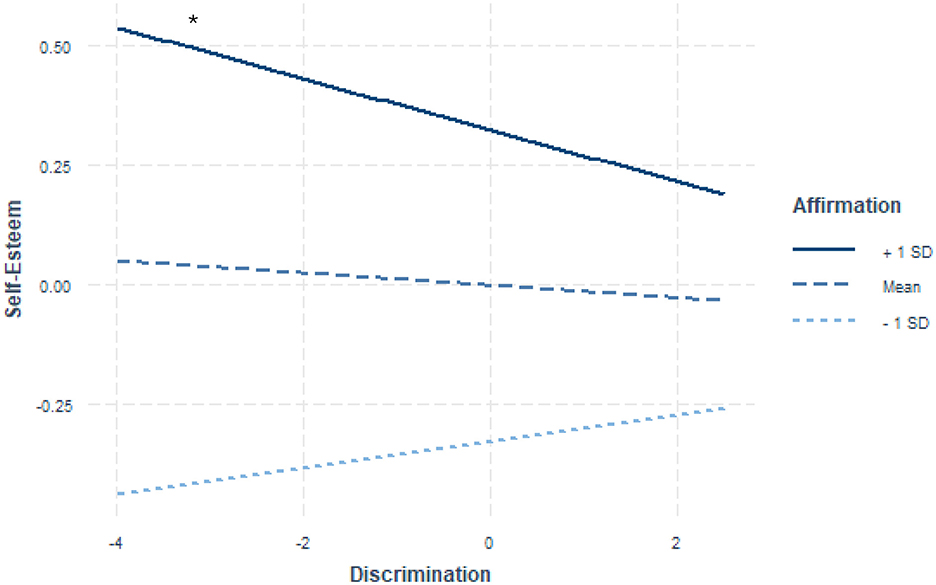

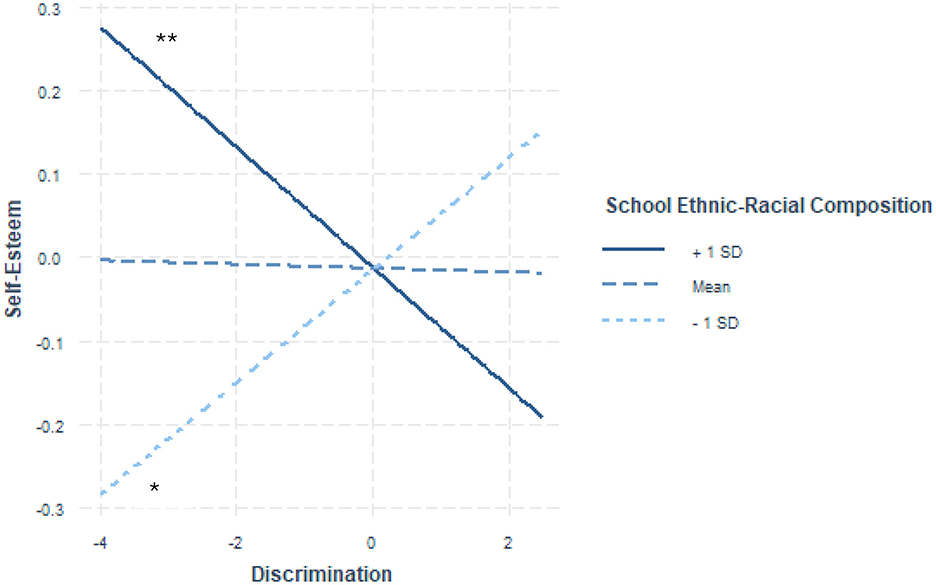

The second hierarchical regression model examined self-esteem controlling for both gender and income. In contrast to models with social anxiety, discrimination was not associated with self-esteem in Step 1 (Table 4). However, ethnic-racial identity affirmation (B = 0.32, SE = 0.02, p < 0.01) and family ethnic socialization (B = 0.11, SE = 0.02, p < 0.01) both positively predicted self-esteem. Notably, discrimination and ethnic-racial identity affirmation interactively predicted self-esteem (B = −0.05, SE = 0.02, p < 0.05), such that discrimination negatively predicted self-esteem only at high levels of ethnic-racial identity affirmation (Figure 2). There was also a significant interaction between discrimination and school ethnic-racial composition (B = −0.06, SE = 0.02, p < 0.01), such that discrimination predicted lower levels of self-esteem when the proportion of minority students was high (B = −0.07, SE = 0.03, p = 0.01) and higher levels of self-esteem when the proportion of minority students was low (B = 0.07, SE = 0.03, p = 0.02; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Interaction plot for self-esteem. School ethnic-racial composition by discrimination. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

The current study examined the associations between discrimination, social anxiety, and self-esteem and explored whether ethnic-racial identity affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition influenced these relationships. The results from this study contribute to a more thorough understanding of how discrimination may impact ethnically and racially minoritized college students' mental health and psychological wellbeing across universities with diverse student body ethnic-racial composition. Furthermore, this study adds to the literature exploring the role of cultural assets in promoting health and wellbeing among ethnically and racially diverse young adults in the United States.

In line with our first hypothesis, greater discrimination exposure was associated with higher levels of social anxiety. This finding is consistent with previous literature, which suggests that discriminatory experiences among ethnically and racially diverse college students predict worse psychological outcomes and highlights that adverse social experiences may specifically elevate social anxiety among historically underrepresented college students, who attend schools from multiple regions in the United States (Martinez et al., 2022). We also found a direct relationship between ethnic-racial identity affirmation and social anxiety suggesting that students who are more affirmed in their identity are less socially anxious. This is not surprising given that affirmation represents one's ability to take pride in themselves as it relates to their ethnic and racial background (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2008). Pride in one's ethnic-racial group may make those students more confident in social settings, such as within school contexts.

Notably, an interactive effect of discrimination and school ethnic-racial composition on social anxiety emerged, such that discrimination was associated with elevated social anxiety for students in universities with more racial and ethnic minorities compared to universities with fewer racial and ethnic minorities. Findings from the current study suggest that discrimination among and can persist even in racially diverse spaces (Bellmore et al., 2012). Prior research in the field also indicates that students who attend schools with higher levels of ethnic and racial diversity may report more discriminatory experiences in their earlier years as they are adjusting to a new environment (Bellmore et al., 2012). Contrary to expectations, we did not find a direct or moderating relationship between family ethnic socialization and social anxiety. One explanation for this lack of association is the previously documented decrease in family ethnic socialization exposure and increase in other socialization sources (i.e., peers and media) that often accompany the transition to adulthood (Jones et al., 2020). Thus, future research should explore the role of peer, school, and media socialization as these sources may be more closely linked to emerging adults' mental health outcomes and school adjustment.

Our second hypothesis was not supported, in that discrimination did not directly predict students' self-esteem. This is surprising since many studies show that discrimination negatively influences self-esteem among ethnically and racially minoritized students (Becerra et al., 2021; Utsey et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2013). One potential explanation for this unexpected finding could be that prior experiences with discrimination during adolescence may have triggered coping efforts that alleviate the detrimental impacts of discrimination on self-esteem in the transition to young adulthood (Jones et al., 2020). It is also possible that our discrimination measure did not capture specific individual-level experiences such as overt personal attacks or covert exclusion that may more directly affect self-worth and thus self-esteem. In contrast, ethnic-racial identity affirmation and family ethnic socialization each positively predicted higher self-esteem. These findings are supported by prior studies that examined the same constructs among biracial college students (Brittian et al., 2013a). Discrimination predicted worse self-esteem when ethnic-racial identity affirmation was high. This is interesting, given that our findings of higher levels of ethnic-racial identity affirmation were associated with higher levels of self-esteem where previous literature that suggests that ethnic-racial identity affirmation is linked to better psychological outcomes (Umaña-Taylor and Shin, 2007). However, rejection sensitivity theory suggests that chronic racial discrimination can contribute to an individual's heightened expectation of rejection, specifically in contexts where their ERI is salient (Downey and Feldman, 1996; Downey et al., 1997).

Specific to ERI affirmation, individual's feelings may intensify the emotional impact of discriminatory experiences, leading to an increase in stress and social anxiety in environments where rejection is likely. There is emerging literature indicates that ethnic-racial identity offers both protection and unique vulnerabilities in the context of discrimination (Yip, 2018). These findings hold several implications for student development including the creation of programs that teach students healthy coping skills around rejection and discrimination. Additionally, universities can work to recruit a more racially diverse faculty population where students can see themselves reflected in their faculty. Since these findings are derived from cross-sectional data, future research should explore the relationships between discrimination, ethnic-racial identity affirmation, and self-esteem over time.

Finally, the interaction between discrimination and school-ethnic-racial composition was significant when school diversity was low. This aligns with previous research that documents that students who may carry the numerical ethnic minority status have an increase in their self-esteem because their ethnic identities become more salient due to the reported increase in discriminatory experiences (Umaña-Taylor and Shin, 2007). Interestingly, when school ethnic-racial composition was high, there were lower levels of self-esteem reported. This could be because more diversity within a school context could heighten differences between students which in turn, affects their self-esteem. It is also possible that self-esteem serves a different function for racially and ethnically minoritized students based on the school ethnic-racial composition. Altogether, these findings suggest that a school's ethnic-racial composition may affect students' psychological wellbeing. Additional research is needed to explore whether findings related to school ethnic-racial composition replicate in varying school contexts with diverse groups of students.

Constraints on generality

Results of the current research may depend on specific characteristics of the study sample and context. First, our study included historically underrepresented racial/ethnic emerging adults (e.g., Black, Latinx, and Asian) who are prone to experiencing ethnic and racial discrimination across a range of colleges and universities in the United States. While we expect our observed associations would likely extend to members of other ethnic-racial minority groups who experience similar cultural stressors and possess similar cultural assets, we do believe our findings may be specific to college students in the United States. The college experience affords emerging adults unique opportunities to interact with a broad range of people and ideas away from their families of origin (Weisskirch et al., 2013). With this exposure, may come an increased likelihood for cultural stressors, like discrimination, as well as opportunities for continued identity development prior to entering the workforce. Additional research is needed to determine whether these associations extend to emerging adults who have assumed working roles, as these individuals may occupy more or less diverse environments and may be more likely to have consolidated their identities. Second, data collection for the current study spanned the years 2008 through 2009. The United States has since witnessed a stark increase in tensions within and between ethnic-racial groups as well as conversations centered around ethnic-racial identity. College campuses, in particular, have adopted new missions related to increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion among their students. Thus, it is plausible the effects observed in the current study may persist or even increase in intensity today, when issues related to race and ethnicity are arguably more salient than ever before, but continued research is warranted.

Limitations and future directions

The current study is not without limitations. First, as much as having a sample recruited from 30 universities is seen as a methodological strength, it is also a limitation. The participants in the study were recruited from universities that may hold different social practices and values; therefore, some students' discriminatory experiences may be over- or under-reported. Although our measure of school ethnic-racial composition captured the proportion of racially and ethnically minoritized students at each institution, it did not distinguish between specific racial or ethnic groups. This aggregation limits our ability to account for the unique intergroup dynamics and social positioning of different student populations within institutions. Future research should examine how specific racial/ethnic group compositions, and the interactions among them, may shape campus climate and the impact of discrimination on mental health outcomes. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limited our ability to interpret the causality of our results. A longitudinal study would be beneficial in allowing us to make causal claims about the direction of our constructs of interest over time. Despite these limitations, our study provides a descriptive depiction of the relationships between discrimination, social anxiety, and self-esteem for ethnically and racially minoritized college students. This study also examined how ethnic-identity affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition play a role in these relationships.

Regarding future directions, scholars might consider examining these constructs with first-generation college students as they may be more socially anxious in college settings compared to students who are not first-generation (Hood et al., 2020). In the current study, participants could only identify as male or female (man or woman). Future work should have more inclusive options for all genders as it will produce a sample more representative of the young adult population. Future work may also explore the nuances that may exist for different groups, as well as discriminatory experiences that contribute to mental health outcomes. Although school ethnic-racial composition and family ethnic socialization were measured in this study, it would also be beneficial to consider a measure of students' high school ethnic-racial composition from their adolescent years. High school ethnic-racial composition can shape how students of color interpret experiences of difference and feelings of otherness on their college campuses, and it is conceivable that these processes may also influence outcomes like social anxiety and self-esteem (Offidani-Bertrand et al., 2022). While this study focused on students in the U.S., additional research should be conducted in other countries to broaden our understanding of these psychological processes and students' educational context. For example, (Adeyemo et al. 2024) studied the relationship between suicidal ideation and anxiety and self-esteem among emerging adults in Nigeria. Lastly, while the current study considered ethnic group discriminatory experiences, future research would benefit from also including a discrimination scale that assesses individual perceptions of discrimination. For example, using a discrimination scale for peers and school personnel may help us better determine which social sources directly impact social anxiety and self-esteem.

Conclusion

The results from this study contribute to a better understanding of how discrimination may impact ethnically and racially minoritized college students' mental health and psychological wellbeing in various university contexts. Previous research has investigated discrimination's impact on social anxiety (Kline et al., 2021) and self-esteem (Becerra et al., 2021). Research has also suggested that institutions such as the education system are known to affect health outcomes for ethnically and racially minoritized populations (Tadros and Tadros, 2024). We advance the existing literature by examining if ethnic-racial identity affirmation, family ethnic socialization, and school ethnic-racial composition influenced these associations. The present study revealed that discrimination served as a risk factor for social anxiety but not directly for self-esteem among college students. We also discovered that ethnic-racial identity affirmation positively affected both social anxiety and self-esteem. Lastly, the relationship between discrimination, social anxiety, and self-esteem varied as a function of school ethnic and racial demographics. As the United States continues to change its laws in higher education around diversity, equity, and inclusion, these constructs should continue to be examined to better learn how to support ethnically and racially minoritized college students.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involving human participants was approved by the University of Miami, which served as the primary institution for ethical oversight. This study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Participants provided their consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LW: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. JM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. BI: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DB: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. ABL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adeyemo, D. A., Olunloyo, B., and Agokei, S. P. (2024). Socio-psychological predictors of suicidal ideation among young adults in Oyo State, Nigeria. Nusantara J. Behav. Soc. Sci. 3, 101–110. doi: 10.47679/njbss.202457

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oakds, CA: Sage Publications.

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Becerra, M. B., Arias, D., Cha, L., and Becerra, B. J. (2021). Self-esteem among college students: the intersectionality of psychological distress, discrimination and gender. J. Public Ment. Health 20, 15–23. doi: 10.1108/JPMH-05-2020-0033

Bellmore, A., Nishina, A., You, J. I., and Ma, T. L. (2012). School context protective factors against peer ethnic discrimination across the high school years. Am. J. Community Psychol. 49, 98–111. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9443-0

Bellmore, A. D., Witkow, M. R., Graham, S., and Juvonen, J. (2004). Beyond the individual: the impact of ethnic context and classroom behavioral norms on victims' adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 40, 1159–1172. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1159

Bethea, T. N., Zhou, E. S., Schernhammer, E. S., Castro-Webb, N., Cozier, Y. C., and Rosenberg, L. (2019). Perceived racial discrimination and risk of insomnia among middle-aged and elderly Black women. Sleep 43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsz208

Bhui, K. (2016). Discrimination, poor mental health, and mental illness. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 28, 411–414. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2016.1210578

Blume, A. W., Lovato, L. V., Thyken, B. N., and Denny, N. (2012). The relationship of microaggressions with alcohol use and anxiety among ethnic minority college students in a historically white institution. Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 18, 45–54. doi: 10.1037/a0025457

Bögels, S. M., Alden, L., Beidel, D. C., Clark, L. A., Pine, D. S., Stein, M. B., et al. (2010). Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress. Anxiety 27, 168–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20670

Bravo, A. J., Wedell, E., Villarosa-Hurlocker, M. C., Looby, A., Dickter, C. L., and Schepis, T. S. (2021). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination among young adult college students: Prevalence rates and associations with mental health. J. Am. Coll. Health. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1954012. [Epub ahead of print].

Bravo, D. Y., Rincon, B., Arnold, E., and Meza, A. (2023). “Transformative views of culture and mental health: From equity and inclusion to cultural empowerment,” in Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 3rd Edn. (Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology), 556–564. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-91497-0.00259-9

Brittian, A. S., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., and Derlan, C. L. (2013a). An examination of biracial college youths' family ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, and adjustment: do self-identification labels and university context matter? Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 19, 177–189. doi: 10.1037/a0029438

Brittian, A. S., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Lee, R. M., Zamboanga, B. L., Kim, S. Y., Weisskirch, R. S., et al. (2013b). The moderating role of centrality on associations between ethnic identity affirmation and ethnic minority college students' mental health. J. Am. Coll. Health 61, 133–140. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.773904

Carter, R. T., and Forsyth, J. (2010). Reactions to racial discrimination: emotional stress and help-seeking behaviors. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Prac. Policy 2:183. doi: 10.1037/a0020102

Castillo, L. G., and Schwartz, S. J. (2013). Introduction to the special issue on college student mental health. J. Clin. Psychol. 69, 291–297. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21972

Castro, S. A., Sasser, J., Sills, J., and Doane, L. D. (2024). Reciprocal associations of perceived discrimination, internalizing symptoms, and academic achievement in Latino students across the college transition. Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 30, 72–82. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000528

Cavalhieri, K. E., Greer, T. M., Hawkins, D., Choi, H., Hardy, C., and Heavner, E. (2024). The effects of online and institutional racism on the mental health of African Americans. Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 30, 476–486. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000585

Chao, R. C.-L., Mallinckrodt, B., and Wei, M. (2012). Co-occurring presenting problems in African American college clients reporting racial discrimination distress. Professional Psychol. Res. Prac. 43, 199–207. doi: 10.1037/a0027861

Chen, A. C., Szalacha, L. A., and Menon, U. (2014). Perceived discrimination and its associations with mental health and substance use among Asian American and Pacific Islander undergraduate and graduate students. J. Am. College Health 62, 390–398. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.917648

Cheng, H. L., Zhang, J., Su, J., and Kim, H. Y. (2020). Race-based marginalization and private racial regard in Asian Americans: self-esteem and nativity as moderators. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 11, 187–197. doi: 10.1037/aap0000202

Coll, C. G., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., Garcia, H. V., et al. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Dev. 67:1891. doi: 10.2307/1131600

Corning, A. F. (2002). Self-esteem as a moderator between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among women. J. Couns. Psychol. 49, 117–126. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.49.1.117

Downey, G., and Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 1327–1343. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1327

Downey, G., Khouri, H., and Feldman, S. I. (1997). “Early interpersonal trauma and later adjustment: the mediational role of rejection sensitivity,” in Developmental Perspectives on Trauma: Theory, Research, and Intervention, eds. D. Cicchetti and S. L. Toth (Rochester. NY: University of Rochester Press), 85–114.

Dryman, M. T., Gardner, S., Weeks, J. W., and Heimberg, R. G. (2016). Social anxiety disorder and quality of life: how fears of negative and positive evaluation relate to specific domains of life satisfaction. J. Anxiety Disord. 38, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2015.12.003

DuPont-Reyes, M. J., and Villatoro, A. P. (2019). The role of school race/ethnic composition in mental health outcomes: a systematic literature review. J. Adolesc. 74, 71–82. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.05.006

Farber, R., Wedell, E., Herchenroeder, L., Dickter, C. L., Pearson, M. R., and Bravo, A. J. (2020). Microaggressions and psychological health among college students: a moderated mediation model of rumination and social structure beliefs. J. Racial Ethnic Health Disparities 8, 245–255. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00778-8

Flores, G. M., Bañuelos, M., and Harris, P. R. (2024). “What are you doing here?”: examining minoritized undergraduate student experiences in STEM at a minority serving institution. J. STEM Educ. Res. 7, 181–204. doi: 10.1007/s41979-023-00103-y

Gaylord-Harden, N. K., and Cunningham, J. A. (2009). The impact of racial discrimination and coping strategies on internalizing symptoms in African American youth. J. Adolesc. 38, 532–543. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9377-5

Grant-Vallone, E., Reid, K., Umali, C., and Pohlert, E. (2003). An analysis of the effects of self-esteem, social support, and participation in student support services on students' adjustment and commitment to college. J. Coll. Stud. Retention Res. Theory Prac. 5, 255–274. doi: 10.2190/C0T7-YX50-F71V-00CW

Gray-Little, B., Williams, V. S. L., and Hancock, T. D. (1997). An item response theory analysis of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 23, 443–451. doi: 10.1177/0146167297235001

Hoggard, L. S., and Hill, L. K. (2016). Examining how racial discrimination impacts sleep quality in African Americans: is perseveration the answer? Behav. Sleep Med. 16, 471–481. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2016.1228648

Hollingsworth, D. W., Cole, A. B., O'Keefe, V. M., Tucker, R. P., Story, C. R., and Wingate, L. R. (2017). Experiencing racial microaggressions influences suicide ideation through perceived burdensomeness in African Americans. J. Couns. Psychol. 64, 104–111. doi: 10.1037/cou0000177

Hong, J. H., Talavera, D. C., Odafe, M. O., Barr, C. D., and Walker, R. L. (2018). Does purpose in life or ethnic identity moderate the association for racial discrimination and suicide ideation in racial/ethnic minority emerging adults? Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 30, 1–10. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000245

Hood, S., Barrickman, N., Djerdjian, N., Farr, M., Gerrits, R. J., Lawford, H., et al. (2020). Some believe, not all achieve: the role of active learning practices in anxiety and academic self-efficacy in first-generation college students. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 21, 10–1128. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v21i1.2075

Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., and Spicer, P. (2006). Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: a review of research and directions for future study. Dev. Psychol. 42, 747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747

Hwang, W. C., and Goto, S. (2008). The impact of perceived racial discrimination on the mental health of Asian American and Latino college students. Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 14, 326–335. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.326

Iwamoto, D. K., and Liu, W. M. (2010). The impact of racial identity, ethnic identity, Asian values, and race-related stress on Asian Americans and Asian international college students' psychological well-being. J. Couns. Psychol. 57, 79–91. doi: 10.1037/a0017393

Jochman, J. C., Cheadle, J. E., Goosby, B. J., Tomaso, C., Kozikowski, C., and Nelson, T. (2019). Mental health outcomes of discrimination among college students on a predominantly White campus: a prospective study. Socius 5, 1–16. doi: 10.1177/2378023119842728

Jones, S. C., Anderson, R. E., Gaskin-Wasson, A. L., Sawyer, B. A., Applewhite, K., and Metzger, I. W. (2020). From “crib to coffin”: navigating coping from racism-related stress throughout the lifespan of Black Americans. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 90:267. doi: 10.1037/ort0000430

Kline, E. A., Warner, C. M., Grapin, S. L., Reyes-Portillo, J. A., Bixter, M. T., Cunningham, D. J., et al. (2021). The relationship between social anxiety and internalized racism in Black young adults. J. Cogn. Psychother. 35, 53–63. doi: 10.1891/JCPSY-D-20-00030

Koo, K. K. (2021). Am I welcome here? Campus climate and psychological well-being among students of color. J. Stud. Affairs Res. Prac. 58, 196–213. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2020.1853557

Landrine, H., and Klonoff, E. A. (2000). Racial segregation and cigarette smoking among Blacks: findings at the individual level. J. Health Psychol. 5, 211–219. doi: 10.1177/135910530000500211

Lee, D. B., Anderson, R. E., Hope, M. O., and Zimmerman, M. A. (2020). Racial discrimination trajectories predicting psychological well-being: From emerging adulthood to adulthood. Dev. Psychol. 56, 1413–1423. doi: 10.1037/dev0000938

Lesure-Lester, G. E., and King, N. (2004). Racial-ethnic differences in social anxiety among college students. J. Coll. Stud. Retention Res. Theory Prac. 6, 359–367. doi: 10.2190/P5FR-CGAH-YHA4-1DYC

Lochner, C., Mogotsi, M., du Toit, P. L., Kaminer, D., Niehaus, D. J., and Stein, D. J. (2003). Quality of life in anxiety disorders: a comparison of obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder. Psychopathology 36, 255–262. doi: 10.1159/000073451

Loyd, A. B., Humphries, M. L., Wilkinson, D., and Maya, A. (2023). “Racial and ethnic socialization from early childhood through adolescence,” in Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Health: Volume 2 Psychological and Behavioral Factors, ed. B. Halpern-Felsher (Elsevier), 681–692. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818872-9.00061-3

Lu, Y., and Wang, C. (2022). Asian Americans' racial discrimination experiences during COVID-19: social support and locus of control as moderators. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 13, 283–294. doi: 10.1037/aap0000247

Lui, F., and Anglin, D. M. (2022). Institutional ethnoracial discrimination and microaggressions among a diverse sample of undergraduates at a minority-serving university: a gendered racism approach. Equality Diversity Inclusion 41, 648–672. doi: 10.1108/EDI-06-2021-0149

Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., and Beyers, W. (2006). Unpacking commitment and exploration: preliminary validation of an integrative model of late adolescent identity formation. J. Adolesc. 29, 361–378. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.03.008

MacIntyre, M. M., Zare, M., and Williams, M. T. (2023). Anxiety-related disorders in the context of racism. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 25, 31–43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-022-01408-2

Malcarne, V. L., Chavira, D. A., Fernandez, S., and Liu, P. J. (2006). The scale of ethnic experience: development and psychometric properties. J. Pers. Assess. 86, 150–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_04

Martinez, J. H., Eustis, E. H., Arbid, N., Graham-LoPresti, J. R., and Roemer, L. (2022). The role of experiential avoidance in the relation between racial discrimination and negative mental health outcomes. J. Am. College Health 70, 461–468. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1754221

Mattick, R. P., and Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 36, 455–470. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6

Metzger, I. W., Salami, T., Carter, S., Halliday-Boykins, C., Anderson, R. E., Jernigan, M. M., et al. (2018). African American emerging adults' experiences with racial discrimination and drinking habits: the moderating roles of perceived stress. Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 24, 489–497. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000204

Mills, K. J. (2020). “It's systemic”: environmental racial microaggressions experienced by Black undergraduates at a predominantly White institution. J. Divers. High. Educ. 13, 44–55. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000121

Neblett, E. W., Rivas-Drake, D., and Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Dev. Perspect. 6, 295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x

Norberg, M. M., Norton, A. R., Olivier, J., and Zvolensky, M. J. (2010). Social anxiety, reasons for drinking, and college students. Behav. Ther. 41, 555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.002

Norton, G. R., McLeod, L., Guertin, J., Hewitt, P. L., Walker, J. R., and Stein, M. B. (1996). Panic disorder or social phobia: which is worse? Behav. Res. Ther. 34, 273–276. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00066-6

Offidani-Bertrand, C., Velez, G., Benz, C., and Keels, M. (2022). “I wasn't expecting it”: high school experiences and navigating belonging in the transition to college. Emerg. Adulthood 10, 212–224. doi: 10.1177/2167696819882117

Pachter, L. M., Caldwell, C. H., Jackson, J. S., and Bernstein, B. A. (2018). Discrimination and mental health in a representative sample of African American and Afro-Caribbean youth. J. Racial Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 831–837. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0428-z

Palmer, R. T., and Maramba, D. C. (2015). Racial microaggressions among Asian American and Latino/a students at a historically Black university. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 56, 705–722. doi: 10.1353/csd.2015.0076

Pascoe, E. A., and Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 135, 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059

Peck, S. C., Brodish, A. B., Malanchuk, O., Banerjee, M., and Eccles, J. S. (2014). Racial/ethnic socialization and identity development in Black families: the role of parent and youth reports. Dev. Psychol. 50, 1897–1909. doi: 10.1037/a0036800

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and enviroment for statisitcal computing. Compuer software. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/

Rivas-Drake, D., Seaton, E. K., Markstrom, C., Quintana, S., Syed, M., Lee, R. M., et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Dev. 85, 40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., and Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 151–161. doi: 10.1177/0146167201272002

Rodebaugh, T. L., Woods, C. M., and Heimberg, R. G. (2006). The factor structure and dimensional scoring of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. J. Anxiety Disord. 18, 231–237. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.231

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the Adolescent Self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400876136

Sanchez, D., Smith, L. V., and Adams, W. (2018). The relationships among perceived discrimination, marianismo gender role attitudes, racial-ethnic socialization, coping styles, and mental health outcomes in Latina college students. J. Latina/o Psychol. 6, 1–15. doi: 10.1037/lat0000077

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., and Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 140, 921–948. doi: 10.1037/a0035754

Steffen, P. R., McNeilly, M., Anderson, N., and Sherwood, A. (2003). Effects of perceived racism and anger inhibition on ambulatory blood pressure in African Americans. Psychosom. Med. 65, 746–750. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000079380.95903.78

Stein, G. L., Castro-Schilo, L., Cavanaugh, A. M., Mejia, Y., Christophe, N. K., and Robins, R. (2019). When discrimination hurts: the longitudinal impact of increases in peer discrimination on anxiety and depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin youth. J. Adolesc. 48, 864–875. doi: 10.1007/s10964-019-01012-3

Tadros, E., and Tadros, G. (2024). The modern regularity of institutionalized racism towards Black Americans. J. Psychol. Persp. 5, 57–62. doi: 10.47679/jopp.525502023

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Alfaro, E. C., Bámaca, M. Y., and Guimond, A. B. (2009). The central role of familial ethnic socialization in Latino adolescents' cultural orientation. J. Marriage Fam. 71, 46–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00579.x

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., and Fine, M. A. (2004). Examining ethnic identity among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the United States. Hispanic J. Behav. Sci. 26, 36–59. doi: 10.1177/0739986303262143

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., and Shin, N. (2007). An examination of ethnic identity and self-esteem with diverse populations: exploring variation by ethnicity and geography. Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 13, 178–186. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.178

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Vargas-Chanes, D., Garcia, C. D., and Gonzales-Backen, M. (2008). A longitudinal examination of Latino adolescents' ethnic identity, coping with discrimination, and self-esteem. J. Early Adolesc. 28, 16–50. doi: 10.1177/0272431607308666

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Yazedjian, A., and Bámaca-Gómez, M. (2004). Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity Int. J. Theory Res. 4, 9–38. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2

Utsey, S. O., Ponterotto, J. G., Reynolds, A. L., and Cancelli, A. A. (2000). Racial discrimination, coping, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among African Americans. J. Counsel. Dev. 78, 72–80. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb02562.x

Wei, M., Yeh, C. J., Chao, R. C. L., Carrera, S., and Su, C. L. (2013). Family support, self-esteem, and perceived racial discrimination among Asian American male college students. J. Couns. Psychol. 60, 453–461. doi: 10.1037/a0032344

Weisskirch, R. S., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Whitbourne, S. K., Park, I. J., Lee, R. M., et al. (2013). An introduction to the composition of the multi-site university study of identity and culture (MUSIC): a collaborative approach to research and mentorship. Cult. Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychol. 19, 123–130. doi: 10.1037/a0030099

Williams, C. D., Byrd, C. M., Quintana, S. M., Anicama, C., Kiang, L., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., et al. (2020). A lifespan model of ethnic-racial identity. Res. Hum. Dev. 17, 99–129. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2020.1831882

Yip, T. (2018). Ethnic/racial identity - a double-edged sword? Associations with discrimination and psychological outcomes. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 27, 170–175. doi: 10.1177/0963721417739348

Yip, T., Wang, Y., Mootoo, C., and Mirpuri, S. (2019). Moderating the association between discrimination and adjustment: a meta-analysis of ethnic/racial identity. Dev. Psychol. 55, 1274–1298. doi: 10.1037/dev0000708

Keywords: discrimination, social anxiety, self-esteem, ethnic-racial identity, school ethnic-racial composition

Citation: Williams L, Mullins JL, Israel B, Bravo DY and Loyd AB (2025) Culture, campus, and confidence: unpacking discrimination's impact on mental health among diverse college students. Front. Educ. 10:1614475. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1614475

Received: 18 April 2025; Accepted: 15 July 2025;

Published: 08 August 2025.

Edited by:

Hamid Mukhlis, STKIP AL Islam Tunas Bangsa, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Nurfitriany Fakhri, State University of Makassar, IndonesiaTria Widyastuti, Yogyakarta State University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Williams, Mullins, Israel, Bravo and Loyd. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: LeNisha Williams, bHdpbGwwODhAdWNyLmVkdQ==

†ORCID: Diamond Y. Bravo orcid.org/0000-0001-7530-2511

LeNisha Williams

LeNisha Williams Jordan L. Mullins

Jordan L. Mullins Bethel Israel2

Bethel Israel2 Aerika Brittian Loyd

Aerika Brittian Loyd