- 1International Business School, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 2School of Humanities, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China

- 3School of International Education, Guangxi Science and Technology Normal University, Laibin, China

- 4Higher School of Economics and Business, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 5Department of International Business, Kazakh Ablai khan University of International Relations and World Languages, Almaty, Kazakhstan

This study examines how social media communication and brand image influence international students’ enrollment intentions in higher education institutions, particularly in response to China’s declining birth rate and increasing number of college graduates. Official data projects an “overcapacity” of over 2.79 million in mainland China’s universities by 2024, with an excess rate of 23.6%. Strategies such as enhancing institutional standards and expanding international student enrollment are being considered to address these trends. Using data from 156 foreign students at three upgraded colleges in Guangxi, this paper explores the roles of user-generated and school-generated contents in social media communication, as well as brand image development factors. Partial least squares regression was employed to evaluate the measurement model and hypotheses. The analysis reveals that social media communication and brand image positively affect brand preference, with brand image mediating their relationship. Interactivity, transparency, and authenticity on social media platforms, along with academic reputation, internationalization, and cultural diversity, significantly influence enrollment intentions. This research offers practical guidance for universities aiming to enhance their brand image via social media to attract more international students, addressing demographic and institutional challenges.

1 Introduction

With the progress of globalization, more and more students are choosing to study abroad. This trend has made universities focus on drawing in international students by using clear and strong communication strategies. In today’s world, where connections between countries are stronger than ever, higher education is expanding. Because of this, universities are focusing more on marketing (Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka, 2016) and branding (Chapleo, 2015). They understand the significance of self-promotion. In order to stand out in a crowded environment, institutions are trying to attract students from all over the world (Hemsley-Brown and Goonawardana, 2007).

Social media has become a powerful way for colleges to communicate with their audience. It enables richer, more engaging communication. It facilitates more than just sharing knowledge with institutions. They can also establish lasting student connections (Thackeray et al., 2008). Standard roles in education are changing as students move away from one-way communication to more effective exchanges where students can interact with one another and the school. Individuals now have more chances to promote ideas and work up. Schools are also becoming more open to listening and responding. This way of learning makes education feel less formal and more like a team effort. It gives everyone a chance to take part and shape their own experience (Hlavinka and Sullivan, 2011; Lipsman et al., 2012; Mangold and Faulds, 2009).

On social media, universities can create spaces where students work together to find and fix problems. This involvement makes the interaction more valuable. Students create content and affect each other’s choices (Sashi, 2012). So social media really helps shape how international students think and decide about their education. It shows them what schools are like, shares stories from other students, and gives updates on courses and campus life. All this info makes it easier for students to pick the right place to study.

Universities are shifting to digital engagement. This is not only because communication trends are changing. It is also a planned step to create and keep a solid brand image. A university’s brand image, like its reputation, values, and how people see the quality of education and student life, plays a big role in international students’ choices about where to study. As competition intensifies, universities must differentiate themselves to attract students. To offer top-notch companies and increase enrollment, it is essential to have a strong brand image. It attracts more individuals and makes colleges stand out. A good photo shows trust and quality, which kids look for. To grow and succeed, schools must focus on this (Abuhassna et al., 2020; Yahya, 2020; Plungpongpan et al., 2016; Ummah, 2019).

Higher education advertisers and managers must be aware of how social media affects a school’s brand image and influences international students’ enrollment selection. This review examines how social media communication affects a school’s brand image and how these elements influence international students registering decisions. The study examines these components to recommend colleges enhance their marketing strategies. This means they can get more international students and improve their international status.

This paper only selects universities that were upgraded from junior colleges to undergraduate institutions around 2015. The future development trajectory of universities in China mainly involves junior colleges being upgraded to undergraduate institutions, which then further obtain master’s degree programs, and ultimately evolve into full-fledged universities. The three regional universities studied in this paper can serve as exemplars for other junior colleges that are about to be upgraded.

The three freshly built undergraduate universities in Guangxi are suitable for research due to their dual advantages, theoretical fit, and sample feasibility. Recognized to award bachelor’s degrees exclusively about 2015, these institutions are still inside the “ground-zero” phase of internationalization and brand building; their recruitment strategies, brand equity, and social-media operations sit fluid, selling a natural laboratory for scanning the “social media → brand image → preference” model. Establishment-based research universities display weaker marginal effects from social media, while these new universities render the independent variables’ explanatory power stand out due to their organized global reputations. Physically, Guangxi borders ASEAN, and in 2023, nearly 66–68% of all international students in the region were from Belt and Road countries, securing typical regional representativeness. There are fewer than 360 international students at the three universities, so this study adopted census-style sampling to collate 156 valid responses (42%). All three are strongly homogeneous regarding academic level, program offerings, and tuition, essentially adjusting for exacerbating variance provoked by institutional type. All three experiences that local public universities implemented in 2015 catered to applied talent cultivation.

The research’s format is as follows: (1) definitions of the key concepts used in the study, (2) description of the survey method, results, and hypothesis tests, (3) conclusions, implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2 Literature review

2.1 Social media communication in higher education

Social media communication in higher education has become an important tool for universities and institutions around the world. They use it to connect with potential students, current students, faculty, and staff. It helps them share information, build relationships, and create a sense of community. Social media platforms have changed how academic communication works. They give institutions new ways to connect with different groups. People can now share ideas and updates faster. These platforms help reach more people easily. Communication has become simpler and more direct. Dholakia’s (2017) study of a public United States university serves as the conceptual framework for this chapter. She identifies three broad stakeholder groups in HE: internal, external, and transformed external. Internal stakeholders include employees, administrators, faculty, and other staff (Conway and Yorke, 1991; Lovelock and Rothschild, 1980). Prospective students, initially external stakeholders, become internal participants or “co-creators” in the education process once they enroll (Conway and Yorke, 1991). Over time, these students transition to alumni, classified as “transformed external” stakeholders (Dholakia, 2017). This study concentrates on current international student-participants.

In recent years, social media has evolved from a mere networking platform to an essential channel for university marketing, branding, and communication strategies. Social media channels are cost-effective, user-friendly, and scalable, allowing for the sharing of user-generated content (Sigala and Marinidis, 2009). Defined as “content created by its audience” (Comm, 2009) and “online tools for collaboration, sharing insights, and connecting” (Strauss and Frost, 2009), social media enables universities to disseminate information about academic programs, campus life, faculty achievements, and institutional values through platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube.

A key aspect of social media communication in HE is targeted messaging. Universities use data analytics to understand their audiences’ preferences and tailor content to meet specific needs. For example, they may share campus tour videos or international student testimonials to appeal to prospective students from different regions. Social media also highlights universities’ academic excellence, research capabilities, and global partnerships, enhancing their appeal to international students.

Social media plays a significant role in fostering a sense of community and belonging. Brand communities, based on Web 2.0, are groups of individuals with a shared interest in a specific brand, forming a subculture with unique values, myths, hierarchy, rituals, and vocabulary (Muniz and O’Guinn, 2001; Cova and Pace, 2006). These communities facilitate customer engagement, influence brand perceptions, and disseminate information (Brodie et al., 2011; Dholakia et al., 2004; Kane et al., 2009; McAlexander et al., 2002; Algesheimer et al., 2005). Customers gain value through various online and offline practices, such as helping others or sharing experiences (Shau et al., 2009; Nambisan and Baron, 2009). Peer-to-peer interactions on social media can significantly influence prospective students’ decisions by providing an authentic view of studying at a particular institution.

However, social media communication also presents challenges. Universities must ensure their messages are clear, consistent, and aligned with their institutional values to mitigate the risks of misinformation or negative comments spreading rapidly. Active management of online presence and fostering positive engagement are crucial for maintaining a favorable image.

In this study, social media communication consists of two parts: users’ generating contents (Ug) and schools’ generating contents (Sg).

2.2 Brand image in higher education

An image is a synthesis presented to the public of all the various brand messages, such as brand name, visual symbols, attributes, products or services, and the benefits of advertisements, sponsoring, patronage, and promotion articles. It results from decoding a message, extracting meaning, and interpreting signs (Nandan, 2005). From this perspective, brand image can be described as a holistic impression of a brand’s relative position as perceived by its users, compared with that of its competitors (Coop, 2004).

In the context of higher education institutions, the concept of brand image has evolved significantly. It refers to the perceptions and associations that students, faculty, and other stakeholders hold about a university or college. These perceptions are formed through various touchpoints such as media exposure, word-of-mouth, campus visits, and academic reputation, all of which shape an institution’s identity and attractiveness. In higher education, brand image can be seen as the sum of a university’s reputation, values, student experiences, and overall positioning in the educational marketplace.

A strong, positive brand image enhances the likelihood of attracting international students. Brand image has long been recognized as an important concept in marketing (Keller, 2003a, 2003b). Keller defines brand image as the perceptions of a brand as reflected by the brand associations held in consumer memory (Keller, 2003a, 2003b). These associations can be described in terms of attributes, benefits, and attitudes based on experiences with the brand. A positive brand image is created through marketing communication programs that link strong, favorable, and unique associations of the brand to the relevant receivers.

Brand associations can also be created through direct experience, information communicated by the organization or other sources (e.g., consumer reports or media), word-of-mouth, and assumptions or inferences from the brand itself (e.g., its name or logo) or its identification with a company, country, channel of distribution, or a particular person, place, or event (Keller, 2003a, 2003b). International students, who often face unique challenges related to distance, cultural differences, and academic expectations, are particularly influenced by how well universities project their image across digital and traditional channels. Universities that convey an image of academic excellence, cultural inclusivity, innovation, and student-centered learning are more likely to attract students from diverse backgrounds.

The creation and communication of a brand image in higher education are driven by several factors, including academic rankings, faculty expertise, research outputs, alumni success stories, and student satisfaction. Social media is now vital for colleges and universities to develop and communicate their brand image. It increases their appeal and demonstrates what distinguishes them from other products. They may update their profiles, share their experiences, and establish personal connections with kids. Institutions can speak their principles and abilities using this strategy. By doing so, they create a stronger appearance electronically. Universities can connect with prospective students on an emotional level by showing student experiences, faculty insights, campus life, and cultural events. This helps strengthen their brand image. These platforms let potential applicants engage in real-time. This creates chances for dialogue and feedback. It can strengthen or change brand perceptions.

Besides having a strong online presence, offline elements like the physical campus, the school’s history, and how well the institution’s values match with what potential students are looking for also play a big role in shaping the brand image. Take this case: a university known for turning out successful graduates in a certain field might be seen as a top player in that area. People may think it sets the standard because it has been around for years and has a strong track record. Its name alone can carry weight, making others view it as an authority or go-to place for that subject. Universities that focus on diversity, sustainability, and social responsibility tend to draw in students who share those values. This, in turn, strengthens the school’s reputation.

Past studies see brand image as having many parts, like how well it works, how people feel about it, and its reputation. Functional image refers to quality requirements that create value. The emotional side includes things you cannot touch, like the customer’s feelings or good thoughts about a brand. Reputation is what people around the world think about the brand. It includes all the ways they judge the company (Cobb-Walgren et al., 1995). In this text, brand image in higher education is described as a concept with many sides, including:

Strength (Si): determined by the magnitude and complexity of brand identity signals and their processing (Keller, 2003a, 2003b).

Uniqueness (Ui): identifying unique, meaningful attributes to provide a competitive advantage (Keller, 2003a, 2003b).

Expectations (ES): linked to how users expect the brand to perform, influenced by educational service attributes and benefits (Smith, 2003).

Perceptions and associations (Pa): this means building a sense of top-notch educational services and fresh academic programs (Keller, 2003a, 2003b; Van Gelder, 2003; Nilson and Surrey, 1998).

Experiences (Es): shaped by actual experiences with the brand (Keller, 2003a, 2003b; Nilson and Surrey, 1998).

Evaluations (En): determined by perceptions, expectations, and experiences (Coop, 2004; Keller, 2003a, 2003b).

2.3 Brand preference in higher education

Brand preference is usually found by asking consumers to pick their favorite brands from a group of products or services. Researchers often use this method to see which brands people like most. They give consumers a list and ask them to choose the ones they prefer. This helps companies understand what brands are more popular (Godey et al., 2016; Keller, 2003a, 2003b). This preference is shaped by what consumers think about the brand’s qualities (Ebrahim et al., 2016). It showed how people want to buy a product or service. This is true even when other choices have similar prices and features (Cobb-Walgren et al., 1995).

In higher education, brand preference means students tend to like some universities more than others. This happens because of different factors that affect how they see and expect things. This idea is key for universities that want to boost their appeal and draw in international students in a tough global market.

Brand preference in higher education is shaped by both physical and non-physical factors. Things like campus facilities, location, and resources matter, but so do reputation, values, and the overall student experience. These aspects work together to form how students and parents view a school. These include the school’s reputation, how good people think the education is, the facilities on campus, and social things like what families and friends suggest. Talking about these features through different ways, like social media, really influences what international students prefer.

Studies show that international students use social media more and more to learn about universities. They check if the information is reliable and start to form opinions based on what they see. Posting on social media, sharing student stories, or putting up videos like campus tours and success stories can shape how students see a university’s brand. These things show the university in a certain way and help form opinions about it. This also plays a significant role in shaping consumer choices. As an example, consider this. A college usually articles about its scientific results, world ties, and student success stories. It gains a stronger brand image as a result. It also makes the school more attractive to international students.

Several factors contribute to the formation of brand preference in higher education. One of the most important factors is how good people think the academics are. This includes things like how knowledgeable the teachers are, the variety of programs offered, and chances for research. Universities seen as having good academic programs often draw in students who value tough studies. Universities with high global rankings and accreditation are often favored. These factors are seen as signs of a school’s prestige and quality.

Beyond academic factors, the campus environment plays an integral role in shaping brand preference. International students look for schools that offer a friendly and supportive atmosphere. They want places with different kinds of students, easy access to help and services, and a campus that is safe and lively. How universities show these things in their social media posts can really affect how students see the school’s brand. It also impacts if they like it more than other schools.

2.4 Intention to enroll or to recommend

Throughout our lives, we make many important decisions. One of the earliest is choosing a career, which then affects which university we pick (Daily et al., 2010). When students start their higher education journey, the first step is choosing a college (Padlee et al., 2010). Social and cultural factors also play a big role in college students’ decisions about where to enroll (Callender and Melis, 2022).

For international students, deciding which college to go to is really complicated. It is influenced by lots of things, like how good they think the university’s reputation is, how interesting the programs are, and what the university is generally like. These ideas shape whether students want to enroll or recommend the university. They get these ideas from their own experiences and from things they see and hear, like on social media. In international higher education, social media is a key tool for prospective students to learn about universities, talk to current students, and form their opinions.

It is important for universities to understand the link between the intention to enroll and the intention to recommend. These factors directly affect both recruitment and word-of-mouth, which shape future student groups. The motivation to suggest a school frequently follows a similar pattern. It is closely related to the purpose of enrolling. Individuals who have had a good experience with the program and decision-making process are likelier to give their peers recommendations. This is especially true for international students, who act as casual ministers for their establishments.

A child’s intention to register or propose is also influenced by external factors, such as how important they think a degree from a specific university is and what kind of job opportunities it may take after graduation. Individuals who believe a college degree may give them good career prospects are more likely to register and suggest the organization. For instance, universities with robust global rankings or connections to exclusive institutions frequently get more recommendations because of the perceived lengthy-term benefits of their degrees.

2.5 Literature review

Current research indicates that social media communication is extremely important in higher education institutions brand building and market promotion (Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka, 2016; Chapleo, 2015). Acumen education (2022) shows the budget for international recruitment is transferring from off-line to on-line social media and apps. TikTok and Instagram mainly cover 18–24 prospective international students. Moreover, alumni and influencer alumni can increase the conversion rate of consultation into application by 2.8 times. Pawar (2024) shares the key messages that social media influences the entire enrolment decision-making process and universities can wholly make social media deliver sound information at each stage of decision making, brand co-creation, and lasting relationships in order to ramp up recruitment performance. However, research on how social media communication influences brand image and undergraduate enrollment intentions remains minimal. This study seeks to fill this distance by objectively evaluating how brand image and social media communication interact and how they impact foreign students ‘enrollment intentions.

Brand image is one of the main influences on consumer choice behavior (Keller, 2003a, 2003b). In the higher education sector, brand image encompasses not only academic reputation and educational quality but also the degree of internationalization and cultural diversity (Abuhassna et al., 2020; Yahya, 2020; Plungpongpan et al., 2016; R and Ummah, 2019). Although past studies have explored the impact of brand image on enrollment intentions, some have examined brand image as a mediating variable in the relationship between social media communication and enrollment intentions.

Despite the literature investigating social media communication, brand image, and enrollment intentions, these reports have primarily focused on individual components or unidirectional ties. This research attempts to construct a detailed design that instantly considers the interplay among social media communication, brand image, enrollment intentions, and the mediating role of brand image in this process, thus providing higher education institutions with more integrated guidance for their marketing strategies.

3 Research hypotheses

3.1 Social media communication and brand preference in higher education

Bamberger et al. (2020) highlight that it is becoming more important for marketers to grasp how higher education institutions present themselves online. This is particularly important when social media and other international options target potential kids. They claim that these systems are essential for influencing perceptions and piquing curiosity. In these settings, businesses should pay close attention to how schools connect their beliefs and products. Today’s primary method of communication with potential individuals is social media. It is more critical for recruiting, specifically for international students. Things like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter support schools reaching out to individuals worldwide. Colleges use these websites to share events, campus life, and training information. In addition, it draws students from various nations (Bamberger et al., 2020). This change coincides with the recent boom in social media (Peruta and Shields, 2018).

Social media platforms give institutions an easier way to display campus life, discuss videos and photographs, and connect instantly with prospective students. This shift in communication allows quicker and more effective interactions than standard marketing programs. It saves money on travel and time (Vrontis et al., 2018).

The connection between social media communication and brand preference in higher education is not simple. It includes the shared content and how users communicate, and it has many elements. Content and conversation heavily influence students’ perceptions of a school’s model. Content, comments, and messages influence people’s perceptions and foster relationships. Schools use these resources to achieve individuals and build a positive image. Social media is then a lively software for higher education institutions to form product selections. It promotes brand loyalty and establishes relationships with prospective international students. Organizations use it to promote changes, showcase campus life, and answer questions from individuals. This creates a more personal connection with the audience. Feedback likes, and stocks are simple ways for users to communicate. In these interactions, the brand becomes more relatable and memorable (Bamberger et al., 2020).

Through social media, institutions share information and communicate with others. They provide films of campus life, virtual tours, and student stories. Instructors share their thoughts, and the university promotes occasions like festivals or art shows. This demonstrates the university’s mission. A college may become more attractive if international students share their experiences and tales. It demonstrates how welcoming and welcoming the class is to everyone. People might be more interested in college if they see this. A concise description of campus life and real-world examples can be used to paint a clear image. This method (Bamberger et al., 2020) helps establish connections with potential students.

Students can communicate with colleges using social media straight ahead. This promotes solid references and fosters trust. These interactions may make people think much of the brand and help students feel more connected. They are also more likely to enroll because of this (Vrontis et al., 2018).

Colleges can use social media resources to target certain groups of international students. They can develop campaigns and advertisements that target these parties immediately. This allows for a more personalized interaction with kids. Institutions can make their text clearer and more successful by focusing on the right audience. Based on feedback and interactions, models can even modify their strategy. Social media allows for constant changes and modifications to better match student needs. Schools can tell the stories, activities, and information that matter to various audiences. This fosters stronger connections and keeps kids serious. This focused communication influences product choices by addressing the particular needs and interests of possible students.

Influencers and alumni could enhance brand preference by sharing their good experiences. This adds credibility and authenticity to the brand impression. People trust real stories from others who have used the brand. When influencers or alumni show their positive interactions, it makes the brand feel more vivid. Their words show that the brand is reliable and trustworthy. International students who share their stories can motivate other students to choose the same university. This helps to make the university more popular (Bamberger et al., 2020).

Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

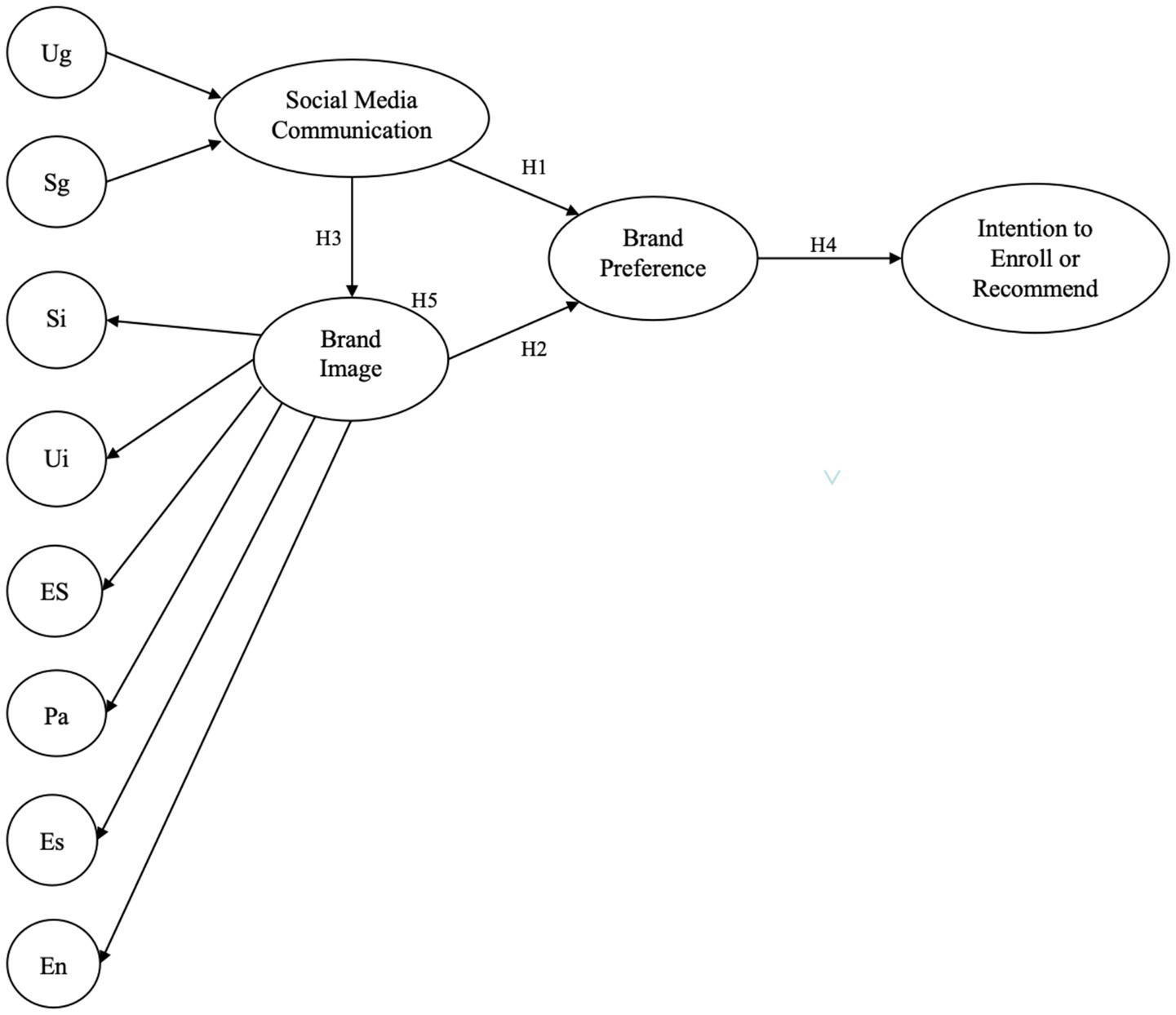

H1: Social media communication (SMC) is positively related to brand preference in higher education (BF).

3.2 Brand image and brand preference in higher education

An institution’s image is key in shaping what students prefer, especially for those looking to study abroad. It can make a big difference when international students choose where to study. They often look at how a school presents itself and what others say about it. This helps them decide if the school is right for them. Schools that seem friendly, strong, or well-known can pull in more students. For someone far from home, these impressions matter a lot. A strong brand image pulls in students who are more likely to enroll. The link between brand image and brand preference is not simple. It has many layers and can work in different ways.

Matching expectations with brand message: a big part of this connection is making sure students’ hopes line up with what the school stands for. When a university’s image matches what potential students want for their personal and academic goals, they are more likely to prefer that brand. For example, a school that shows it cares about diversity, innovation, and programs focused on students might draw in international students looking for an open and modern learning environment.

Academic quality and social media presence: besides how good a university is at teaching; its social media presence now plays a big role in building its brand image. Talking to potential students online in a clear and engaging way can help build a feeling of belonging and inclusion. This also boosts how the institution is seen around the world. Since international students often rely on social media for information gathering and connection building, positive online engagement can significantly strengthen brand preference.

Brand image as a crucial marketing factor: brand image is a critical component in marketing, serving as an informational cue that helps consumers predict product quality, develop purchase behavior, and retain memories (Erdem and Swait, 1998). In education, a school’s established brand image is a significant factor in students’ selection process. A positive brand image emphasizes unique brand associations (Jara and Cliquet, 2012; Keller, 1993) and plays a relevant role in consumers’ decision-making processes (Braun et al., 2014). It is developed through biased evaluations that impact consumers’ brand preference responses and their intention to buy or visit (Jara and Cliquet, 2012).

Based on the literature and theoretical background, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Brand image in higher education (BI) influences brand preference (BF) in higher education.

3.3 Social media communication and brand image in higher education

Digital literacy and the digital mindset are instrumental in connecting society to the modern world. As consumers evolve into “internet users” and society transforms into a “network society,” every sector must adapt to digitalization (Kazaishvili, 2022). In the context of universities, brand loyalty can be gauged through word-of-mouth promotion among prospective or existing students, with their social media presence significantly impacting brand image. Consumer loyalty can be driven by performance-related or imagery-related factors (Erdogmus and Ergun, 2016).

Effective communication extends beyond spoken and written language (Blohm et al., 2020). Brand attitude, more influential than brand equity, plays a pivotal role in shaping institutional perception (Schivinski and Dąbrowski, 2013). Any branding activity can contribute to brand communication, reinforcing a strong institutional image (Wijaya, 2013).

Social media empowers institutions to reach a global audience, enabling the creation and distribution of content that showcases academic strengths, campus life, and alumni success stories. For instance, universities can leverage Instagram or Facebook to share student testimonials, virtual campus tours, and live Q&A sessions with faculty, fostering a positive and relatable brand image. Such content not only highlights educational offerings but also conveys inclusivity, diversity, and global engagement—crucial factors for international students. Notably, Facebook, with roughly 2.91 billion monthly active users as of Q4 2021, remains the largest social network worldwide.

Moreover, social media platforms facilitate two-way communication, allowing potential students to engage directly with institutions. This interaction can enhance brand perception by making the institution appear more accessible and responsive. For example, timely and informative responses to inquiries about specific programs or cultural activities can bolster a positive brand image.

Beyond direct communication, the management of online presence and feedback response significantly impacts brand image. Consistent and transparent communication builds trust and credibility, essential for a strong brand. Addressing negative feedback or misinformation swiftly and effectively demonstrates an institution’s commitment to high service standards and student satisfaction.

Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Social media communication (SMC) positively affects brand image in higher education (BI).

3.4 Brand preference and decision to enroll or recommend in higher education

Both public and private higher educational institutions (HEIs) strive to increase enrollment, reduce dropout rates, build a strong reputation, raise funds, and outperform competitors through effective performance measurements (Williams and Omar, 2014). In marketing, brand equity studies show that how customers think and feel about a brand comes before how they act toward it (Aaker, 1991; Keller and Brexendorf, 2019; Mourad et al., 2020). Customers first form opinions and attitudes, and these shape their actions. For example, if someone likes a brand, they are more likely to buy it. This idea is key in understanding customer behavior. For higher education institutions, figuring out and handling these factors can bring in more students and boost the financial worth of their brands.

Choosing to enroll in or recommend a college is affected by many things. Brand preference plays a big role in this decision. In higher education, brand preference shows how students like a certain school because of its qualities, reputation, and image. This preference greatly influences students’ decision-making. They match their educational choices with personal values, goals, and expectations. Knowing how brand preference affects enrollment or recommendation choices can offer useful insights for schools looking to draw in international students.

A student’s choice of school depends on many things. The quality of teaching matters a lot. So do the campus buildings and tools. The teachers’ knowledge plays a big part too. The people and vibe around the school also make a difference. And of course, what others think about the school counts as well. International students also think about things like cultural diversity, global recognition, language help, and job chances after graduation. These factors add to their overall choice. These factors, when positively perceived, enhance the likelihood of enrollment. International students usually like universities that have good global rankings, a mix of different students, and friendly, welcoming atmospheres.

Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Brand preference in higher education (HE) influences the intention to enroll or recommend (ER).

3.5 The relationships between social media communication and brand preference in higher education via brand image in higher education

Corporate social media activities can be categorized into five main areas: communication, information provision, support for daily life, promotion and selling, and social response and activity (Lee, 2017). Social media serves as a platform for people to interact and exchange ideas, offering insights and information about users who engage with a brand and express their opinions about brands or products through social media interactions (Richter and Koch, 2007). Customization in social media is achieved by engaging individual users, a strategy distinct from conventional media.

Social media provides the most up-to-date news and information, making it a tool to search for the most practical products (Naaman et al., 2011). Consumers tend to trust information acquired through social media more than that from advertisements in marketing activities or promotions. Therefore, trust tends to exist for the various types of social media that provide the newest information (Mangold and Faulds, 2009; Vollmer and Precourt, 2008). This method lets us share personalized and optimized info from different sources. It tries to build a good image and make consumers happier. Companies can use this to show what makes their brands special and build preference and differentiation.

In higher education, social media communication and brand preference are closely linked through brand image. This connection greatly influences international students when they decide on where to enroll. This part looks at how communication strategies on social media can shape how people see a higher education institution’s brand and how they prefer it. This happens because of the way the institution’s brand image is presented and perceived. The role of brand image as a mediator in this relationship is also significant. A strong brand image, created by steady and engaging social media communication, boosts brand preference. It also makes international students more likely to enroll or recommend the institution. When a university is seen as having a strong reputation, being socially responsible, and offering excellent academics, students tend to consider it a top choice.

Consequently, we propose the final hypothesis:

H5: The relationship between social media communication (SMC) and brand preference in higher education (HE) is mediated by brand image.

The following International Student Enrollment model illustrates the elements that precede and determine the intention to enroll or recommend, as well as the factors that influence these elements (Figure 1).

4 Data and results

4.1 Data collection and sample

In this study, we employed a non-probability sampling method, especially convenience sampling, to find 156 foreign students from three universities in Guangxi who have been upgraded to offer academic programs as our research subjects. Since 2015, these institutions have offered bachelor programs, but the COVID-19 crisis saw a substantial decline in global learners. The reason for selecting these schools is that they represent the emerging power of Chinese higher education institutions in the internationalization approach and face the challenge of attracting foreign students.

The sample size was persevered based on the following considerations: First, considering the feasibility and price performance of the research, we chose a reasonable sample size to ensure the efficiency of data collection and the sustainability of the research. Next, based on the sample size of similar reports (Vrontis et al., 2018; Mulyawan and Kusdibyo, 2021), we believe that 156 members are enough to give stable and reliable results. Finally, we ensured variety in the pattern’s gender, age, and educational level to ensure the pattern’s representativeness.

The present study adopts the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) for two main reasons. First, it is suitable for exploratory research or scenarios where data collection is challenging. This study focuses on international students in China, a group from which sampling is inherently difficult. Second, even with small sample sizes, PLS-SEM can still achieve a high level of statistical power (Reinartz et al., 2009; Barclay et al., 1995).

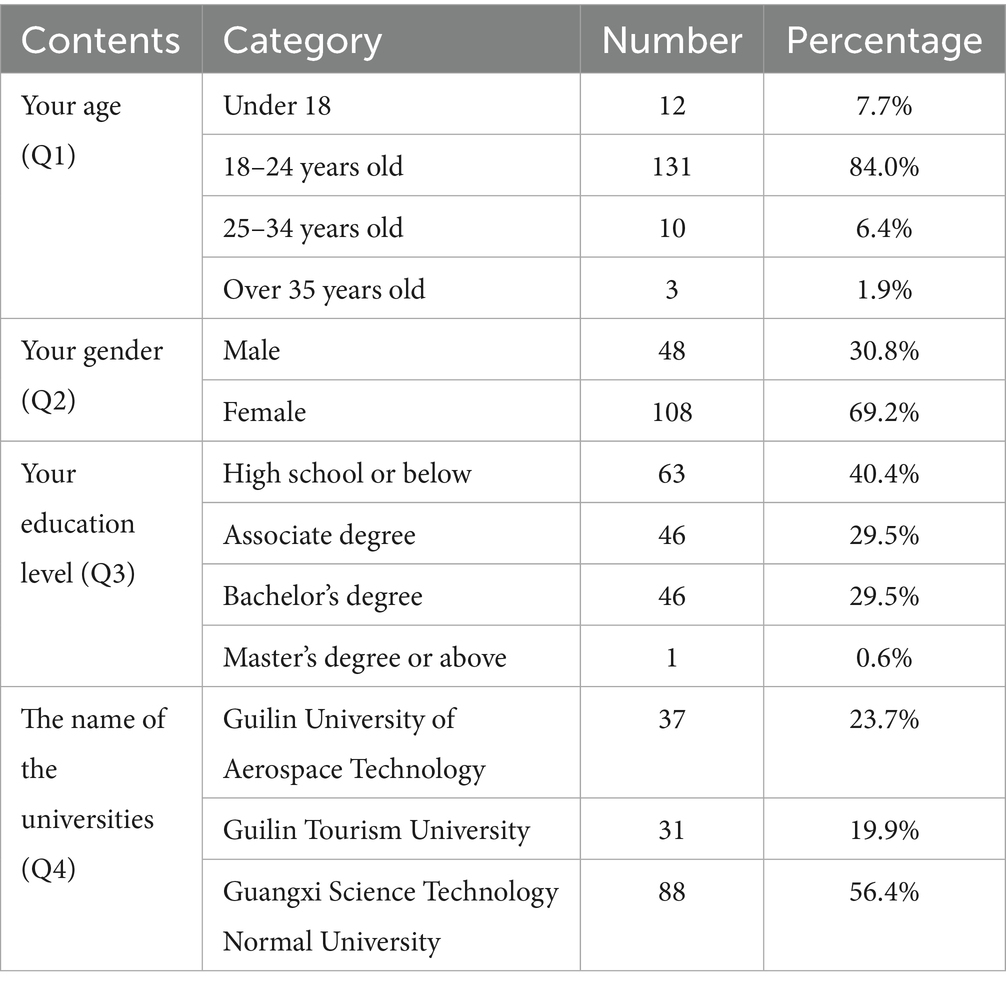

By the period from 2023 to 2024, the total number of international students across the three universities did not exceed 360. For this study, the sample size was 156 students, representing over 40% of the total international student population. Among the participants, 69.2% were female and 30.8% were male (Table 1):

4.2 Measures

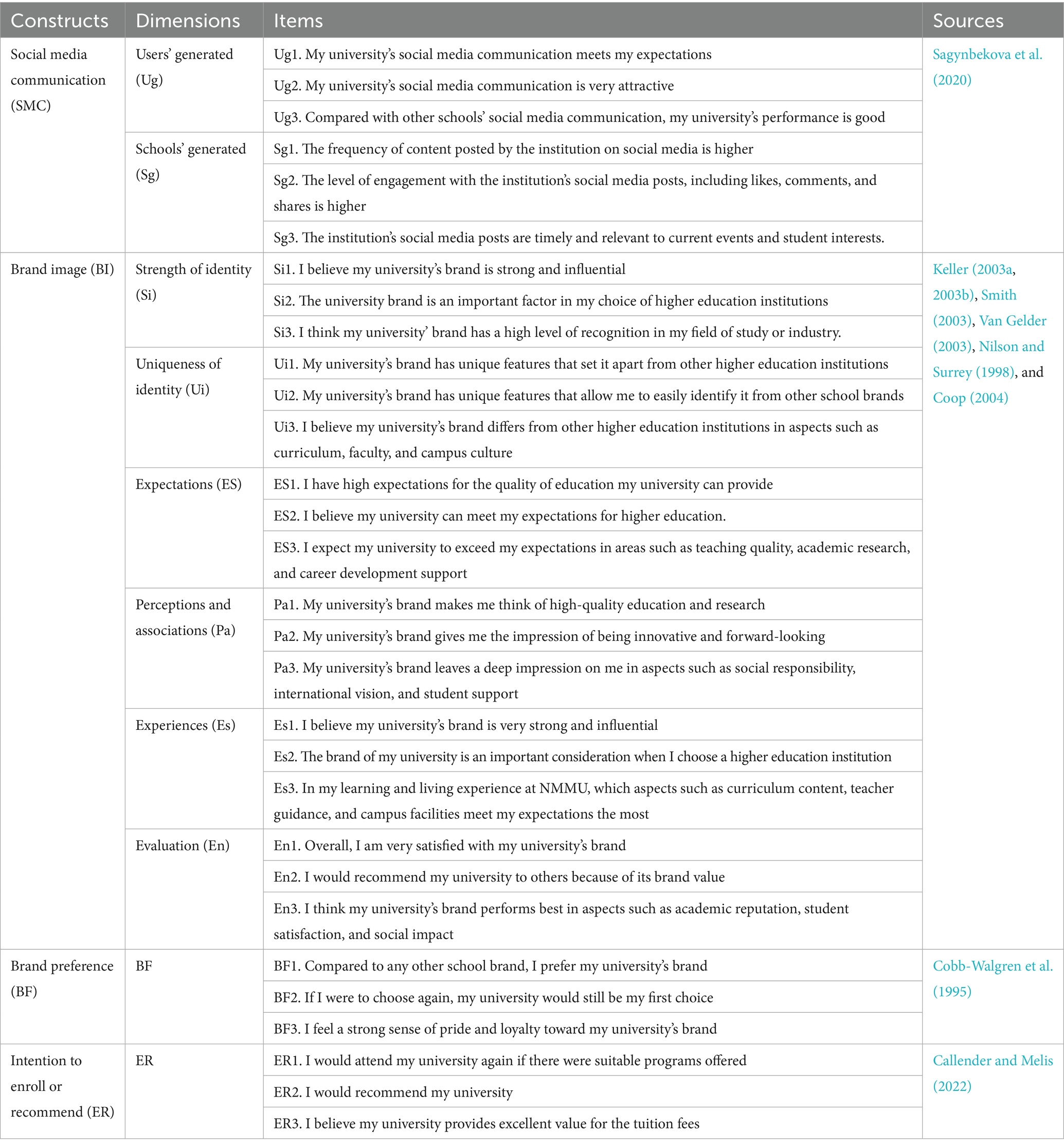

The survey instrument included two main categories: (1) Demographic Information: This section gathered basic demographic data about the participants. (2) Rating Scales: This section focused on social media communication, brand image, brand preference, and enrollment intentions. The rating scales were developed based on the current literature (Table 2):

Social media communication was measured using a 6-item scale. It included two dimensions: user-generated content and institution-generated content, each with 3 items. Brand image was assessed using 18 items across six dimensions, based on a specific theory.

Brand Preference and Enrollment Intentions was measured using 3 items, respectively. We used a 5-point Likert scale for all items. Finally, there two construct types as follows:

Formative Constructs: Social media communication was treated as a formative construct. In formative constructs, the indicators form the construct, meaning they are components of the construct rather than outcomes. Improving the construct does not necessarily require improving all indicator values simultaneously (Bollen and Lennox, 1991).

Reflective Constructs: These are reflected by their indicators, meaning the indicators are outcomes of the construct rather than components.

4.3 Data analysis

We employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to validate the accuracy of the model and its scope (Chin, 2010; Henseler et al., 2016). In this study, we used a two-step approach (Becker et al., 2012). The first part involved analyzing the validity and reliability of the constructs. For formative constructs, we focused on analyzing indicator weights and collinearity tests; for reflective constructs, we examined factor loadings, Cronbach’s α, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Finally, we assessed discriminant validity using Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) test and the HTMT criterion. The second stage involved validating the paths and hypotheses.

4.3.1 Evaluation of the first stage

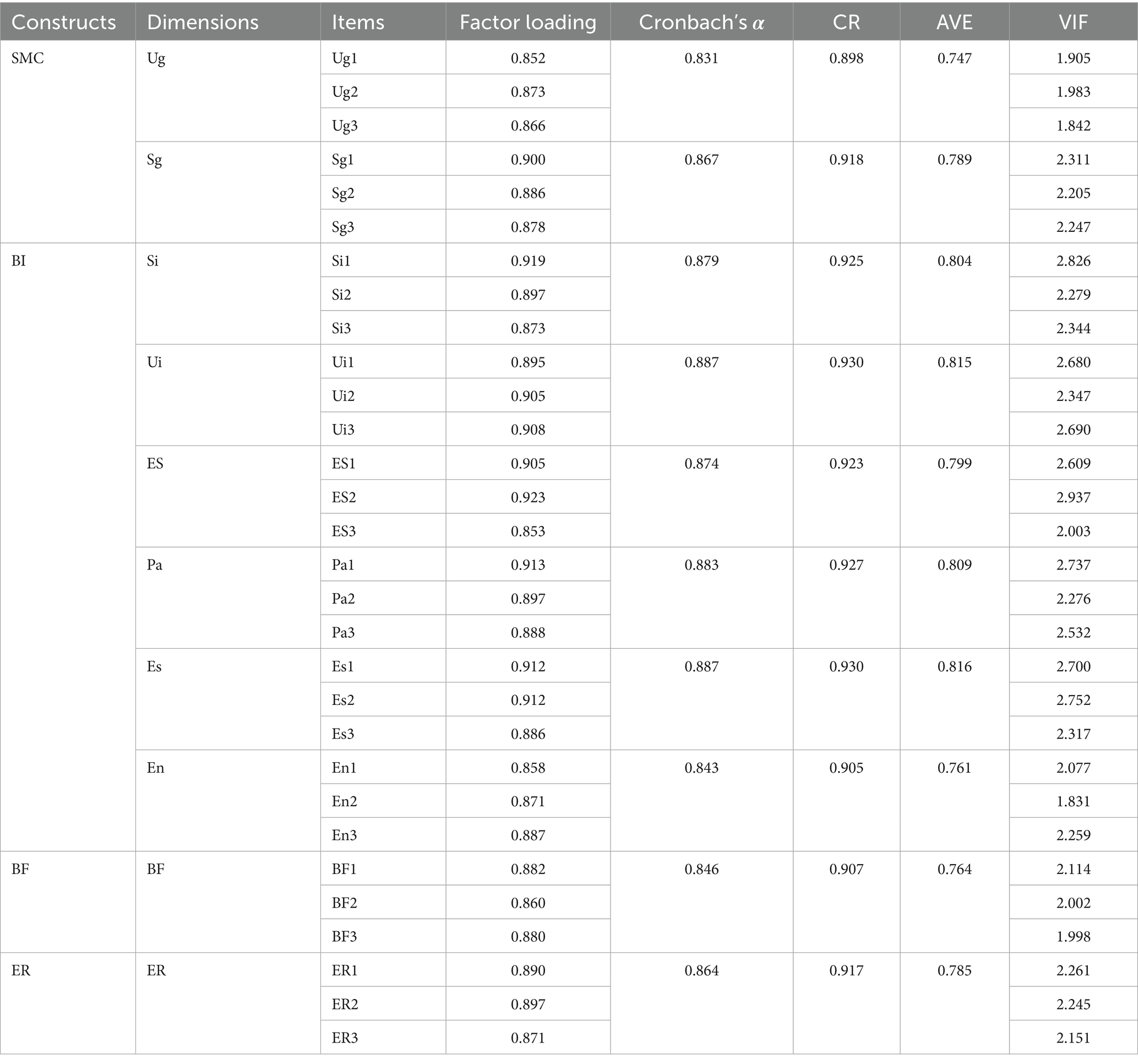

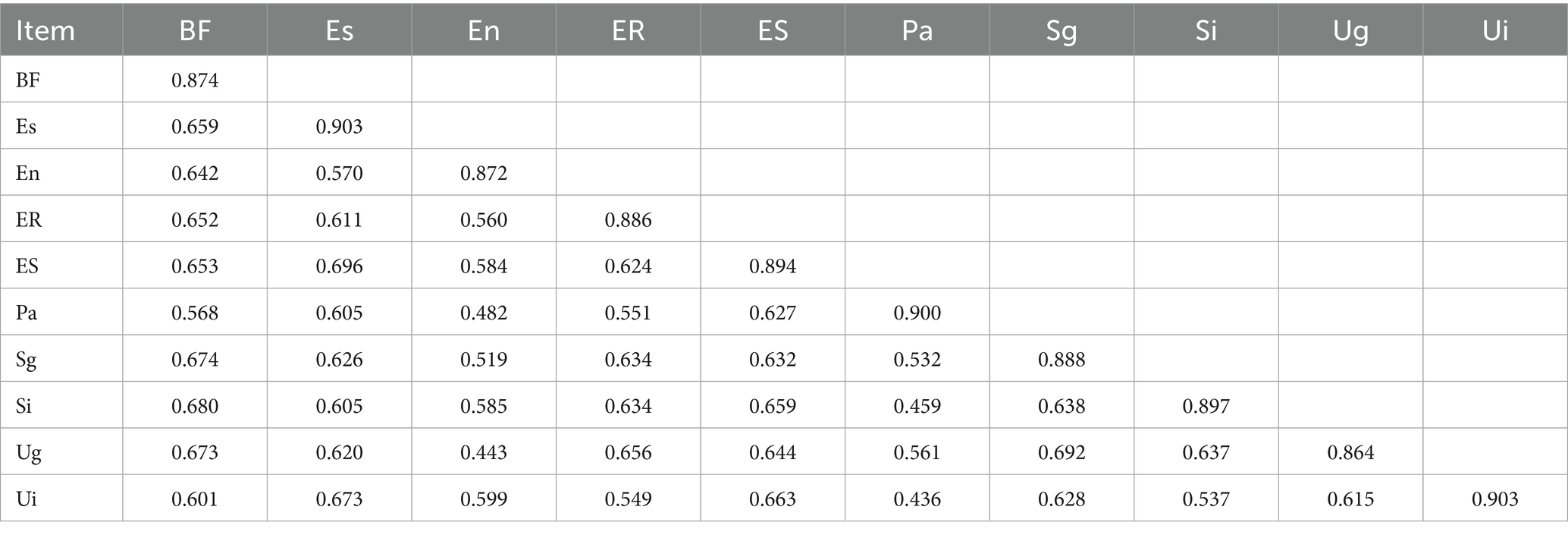

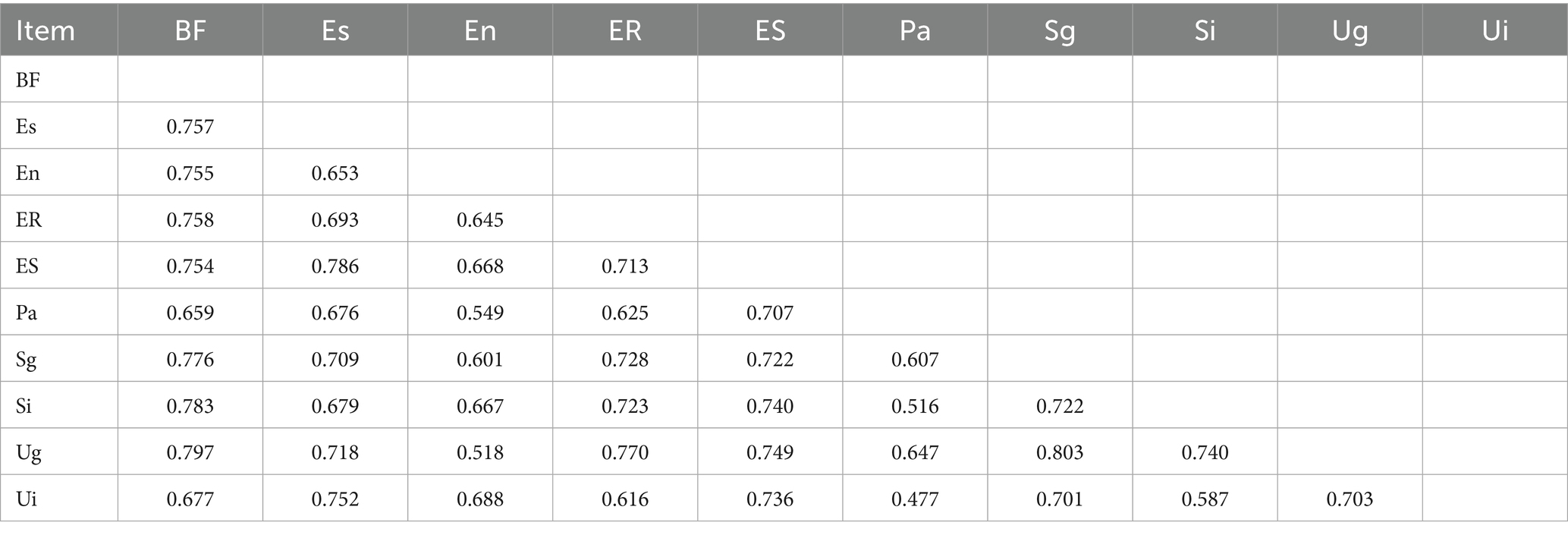

The Table 3 for the first part is as follows:

The first stage focused on ensuring that the values for both formative and reflective constructs were reasonable.

For formative constructs, the indicator weights were as follows:

Customer-generated: β = 0.542, t = 37.895, p < 0.001.

Institution-generated: β = 0.545, t = 30.527, p < 0.001.

The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were all <3, indicating no multicollinearity issues.

For reflective constructs, the following criteria were met:

Factor loadings were >0.7.

Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) were >0.7.

Average variance extracted (AVE) was >0.5.

Finally, Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) test and the HTMT criterion were used to verify discriminant validity (Tables 4, 5). All measures demonstrated sufficient convergent validity and reliability.

4.3.2 Evaluation of the second stage

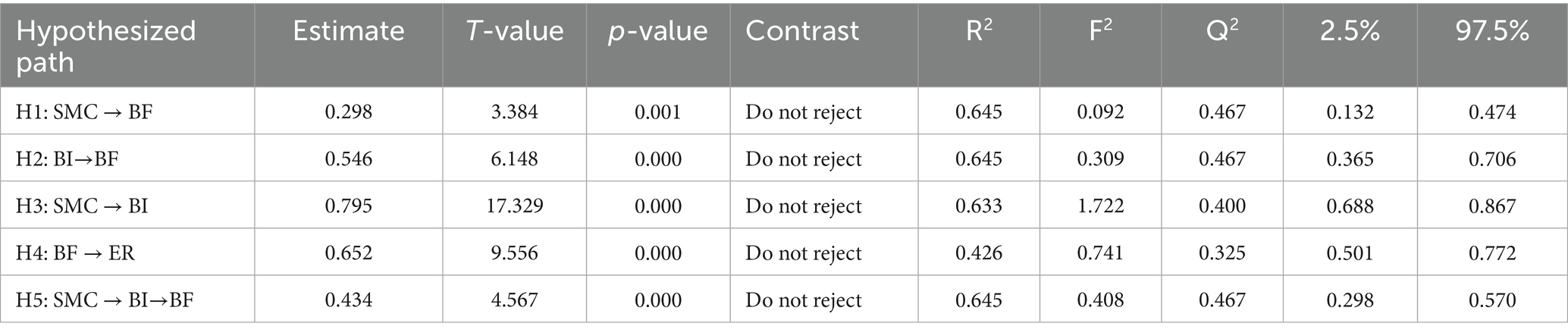

Based on the descriptions in Table 6, the following results were obtained:

SMC → BF: β = 0.298, T = 3.384, p = 0.001, Confidence Interval (α = 0.05) = (0.132, 0.474), R2 = 0.645, f2 = 0.092, Q2 = 0.467.

BI → BF: β = 0.546, T = 6.148, p = 0.000, Confidence Interval (α = 0.05) = (0.365, 0.706), R2 = 0.645, f2 = 0.309, Q2 = 0.467.

SMC → BI: β = 0.795, T = 17.329, p = 0.000, Confidence Interval (α = 0.05) = (0.688, 0.867), R2 = 0.633, f2 = 1.722, Q2 = 0.400.

BF → ER: β = 0.652, T = 9.556, p = 0.000, Confidence Interval (α = 0.05) = (0.501, 0.772), R2 = 0.426, f2 = 0.741, Q2 = 0.325.

SMC → BI → BF: β = 0.434, T = 4.567, p = 0.000, Confidence Interval (97.5% CI) = 0.298–0.570, R2 = 0.645, f2 = 0.408, Q2 = 0.467.

Based on the above data, all five hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5) were supported. The specific results are as follows:

H1: Social media communication (SMC) has a significant positive impact on brand preference (BF) with a small effect size (R2 = 0.645, f2 = 0.092, Q2 = 0.467).

H2: Brand image (BI) has a significant positive impact on brand preference (BF) with a medium to large effect size (R2 = 0.645, f2 = 0.309, Q2 = 0.467).

H3: Social media communication (SMC) has a significant positive impact on brand image (BI) with a large effect size (R2 = 0.633, f2 = 1.722, Q2 = 0.400).

H4: Brand preference (BF) has a significant positive impact on enrollment or recommendation intention (ER) with a large effect size (R2 = 0.426, f2 = 0.741, Q2 = 0.325).

H5: Social media communication (SMC) has a significant indirect positive impact on Brand preference (BF) through Brand image (BI) with a large effect size (R2 = 0.645, f2 = 0.408, Q2 = 0.467).

The Q2 values also confirm that the model has strong predictive power, outperforming simple mean predictions (>0) (Table 6).

To comprehensively evaluate the model fit, the Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) index was calculated following the PLS-SEM framework proposed by Tenenhaus et al. (2005). The specific measurement method is as follows:

Since communality is equivalent to AVE in the PLS path modeling method (Wetzels, 2009), the formula can be converted as follows:

According to the GoF formula, the calculated GoF value is 0.646. Based on Wetzels et al. (2009) research findings, when GoF reaches 0.1, the model is considered to have a low fit; when GoF reaches 0.25, the model is moderately fitted; and when GoF reaches 0.36, the model is highly fitted. Since the model’s GoF value = 0.646 > 0.36, we conclude that the model passes the goodness-of-fit test.

The calculated GoF value was 0.646, significantly higher than the 0.36 threshold set for the large-effect model. This validates that the overall model has a high degree of fit.

Hypotheses H1 and H3 predict that social media communication will positively impact brand image and desire. Through PLS-SEM analysis, we found that the impact of social media communication on brand image is significant (β = 0.795, T = 17.329, p = 0.000), and its impact on brand preference is also significant (β = 0.298, T = 3.384, p = 0.001). This demonstrates how crucial social media communication is to creating consumer preferences and brand image. Hypotheses H2 and H4 predict that brand image may favorably affect brand preference and admission purpose. The analysis results show that the impact of brand image on brand preference is significant (β = 0.546, T = 6.148, p = 0.000), and its impact on enrollment intention is also significant (β = 0.652, T = 9.556, p = 0.000). A good brand image may entice individuals and encourage membership choices. Hypothesis H5 predicts that brand image plays a mediating role between social media communication and product choice. The mediating effect analysis shows that the mediating effect of brand image between social media communication and brand preference is significant (β = 0.434, T = 4.567, p = 0.000). This highlights the importance of creating a good brand image through social media communication in the marketing strategies of higher education institutions. Through these evaluations, we have verified the study hypotheses and provided factual support for how higher education institutions may use social media communication and brand image to attract foreign individuals. These studies have significant practical significance for higher education institutions in developing successful marketing strategies.

5 Discussion and conclusions

5.1 Theoretical implications

After the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, universities in Guangxi, China, are attracting an increasing number of students from ASEAN countries, thanks to both policy support and regional advantages. This trend is primarily driven by the rapid economic development in ASEAN nations. For instance, Vietnam, a neighboring country of Guangxi, has experienced significant economic growth, which has fueled job creation. China has long been Vietnam’s largest trading partner, and the increasing investment by Chinese companies has sustained a high level of interest in learning Mandarin. A survey conducted by a Vietnamese institution revealed that Vietnamese students proficient in Chinese have nearly a 100% chance of securing employment after graduation. This presents a unique opportunity for newly established undergraduate institutions to capitalize on this wave of international students, and university administrators should carefully consider how to do so effectively.

This article primarily analyzes the factors influencing international students’ school brand preferences and enrollment intentions, focusing on social media and university brand image. The research fills a gap in understanding how newly established undergraduate institutions can attract international students. Unlike previous qualitative studies that examined the impact of brand image on customer satisfaction and purchasing decisions (David G. Abin et al., 2022), this study provides a comprehensive analysis of school brand preferences and enrollment choices. Additionally, Mulyawan and Kusdibyo (2021) demonstrated that social media content significantly influences students’ desire to attend a college or university, highlighting the importance of effective social media strategies in higher education marketing.

Firstly, this study takes a holistic approach from Mar (2023) to understanding the intention to visit wineries, thereby strengthening the theoretical foundation in higher education, particularly in newly upgraded universities.

Secondly, this study examines the impact of social media on universities from both the customer and institutional perspectives, providing an in-depth analysis of the importance of social media in university communication. Previous research, such as a study conducted in Athens, Greece (2013), only explored the influence of social media from the student’s perspective.

Thirdly, this article tests a proposed brand image construct, which is reflective in nature, unlike the formative construct presented in Mar (2023). The brand image construct in Mar’s article consists of three dimensions: functional image, affective image, and reputation. This study further demonstrates that the nature of constructs (formative or reflective) can change depending on the context and indicators used.

Fourthly, this article extends the validity of Mar’s (2023) theoretical model in the wine service industry to other service sectors, such as higher education. By modifying some constructs and indicators, a similar model can be effectively applied to higher education services. Mar’s (2023) article discusses the roles of brand communication and brand image, and this study further refines the impact of brand communication on brand image by focusing on the social media indicator.

Fifthly, this study proposes an indirect variable as a hypothesis, making Mar’s (2023) model more illustrative. The updated model’s use in PLS-SEM and data analysis is more intuitive, providing a valuable reference for future researchers.

From an information-processing perspective, prospective students first engage in cognitive–affective elaboration of social-media content (UGC + SGC), making an overall brand image (BI). Thereafter, taking BI as a heuristic cue, brand preference (BF) occurs actively, fostered, and information-search costs can be reduced. This two-stage route almost merely encapsulates. Petty and Cacioppo (1986) ELM in high-involvement educational decisions (1986) but additionally notes why social media’s direct effect on BF (β = 0.298, f2 = 0.092) is sharply smaller than its indirect effect via BI (β = 0.434, f2 = 0.408). Simultaneously, the relationship-marketing lens highlights BI’s role as a psychological bond in the student–university relationship: BI’s standardized path coefficient on BF reaches β = 0.546, fast outweighing social media’s direct coefficient. This indicates that social media’s ability to create an impactful brand image can be badly weakened. In other words, brand image plays a precursor to support, while brand preference acts as a precursor to trust, increasing the scope of the commitment–trust mechanism in the social media context.

Finally, this article demonstrates the direct influence of brand preference on enrollment intentions or recommendations. University administrators, particularly those in newly established undergraduate institutions, should recognize the interplay between brand preference and enrollment decisions. Students who develop a strong attachment to a brand are more likely to choose it over others and advocate for it within their networks. This finding aligns with consumer behavior theory, which suggests that emotional and psychological connections to a brand can drive decision-making processes. For higher education institutions, cultivating a loyal student base through consistent and authentic brand messaging can lead to increased enrollment and positive word-of-mouth. Moreover, the results highlight the mediating role of brand image in the relationship between social media communication and brand preference, suggesting that effective social media strategies can indirectly enhance brand preference and improve an institution’s market standing. This aligns with integrated marketing communications theory, which emphasizes the synergy between different communication channels in building a cohesive brand image.

5.2 Practical implications

This article provides university administrators with more nuanced strategies for attracting international students. The effect size (f2) of the path from Social Media Communication (SMC) to Brand Preference (BF) is 0.092, indicating a small to medium effect. Administrators can further strategize by considering both the user and institutional perspectives in social media communication. Given the increasing activity of students on social media platforms, the study found that three newly established undergraduate institutions primarily use their official websites and WeChat accounts for communication. However, many international students prefer local social media platforms. Therefore, universities should diversify and internationalize their social media tools.

Additionally, universities should analyze the social media content relevant to their target international student population and develop tailored promotional strategies. Campus life and university experiences should be vividly and engagingly presented across multiple social media platforms, rather than relying solely on Chinese domestic platforms. Furthermore, if conditions permit, universities should establish internationalized media centers, allowing both local and international students to manage related accounts, thereby facilitating more global media outreach.

The study also underscores the importance of a positive brand image in shaping students’ preferences. Institutions with a well-defined brand identity that resonates with their target audience are more likely to attract and retain international students. Brand image is not just about visual identity but encompasses the overall experience and reputation of the institution. Schools that emphasize their global reach, diverse student body, and high academic standards often enjoy a competitive advantage in the international student market.

Finally, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how social media and brand image influence international students’ enrollment decisions. It highlights the need for higher education institutions to adopt a holistic approach to brand management, integrating digital communication with a strong brand identity. Future research could explore the longitudinal effects of social media strategies on brand loyalty and investigate the specific content types that most effectively enhance brand image.

5.3 Limitations and future research

This study aims to increase the attention of university administrators and decision-makers toward the enrollment intentions of international students. However, there are several limitations to consider:

Firstly, the research is limited to universities in Guangxi that offer bridging programs for direct admission to undergraduate studies. Future studies could expand to include private undergraduate institutions or compare public and private universities, as well as conduct in-depth research on more established universities.

Secondly, the scope of the concepts studied can be broadened. For example, future research could explore the brand equity of universities and incorporate additional metrics. Additionally, combining qualitative research with quantitative methods can help mitigate the risk of biased data resulting from the subjective views of survey respondents.

Thirdly, future research could investigate the impact of specific social media platforms on brand image and enrollment intentions, as different platforms may have varying levels of influence. Furthermore, examining the role of cultural differences in how international students perceive brand image and communication efforts could provide deeper insights into tailoring strategies for diverse student populations. Additionally, further studies could explore the long-term effects of social media communication on brand loyalty and advocacy among alumni, offering a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between social media, brand image, and student enrollment decisions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. YQ: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology. LX: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HR: Visualization, Software, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. AA: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Visualization, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aaker, D. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Abin, D. G., Mandagi, D. W., and Pasuhuk, L. S. (2022). Influence of brand image on customer attitude, intention to purchase and satisfaction: the case of start-up brand Pomie bakery. J. Manage. 12, 3907–3917.

Abuhassna, H., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Yahya, N., Zakaria, M. A. Z. M., Kosnin, A. B. M., and Darwish, M. (2020). Development of a new model on utilizing online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 17, 1–23. doi: 10.1186/s41239-020-00216-z

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., and Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: evidence from European car clubs. J. Mark. 69, 19–34. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363

Bamberger, A., Bronshtein, Y., and Yemini, M. (2020). Marketing universities and targeting international students: a comparative analysis of social media data trails. Teach. High. Educ. 25, 476–492. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1712353

Barclay, D. W., Higgins, C. A., and Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: personal computer use as an illustration. Techno. Stu. 2, 285–309.

Becker, J. M., Klein, K., and Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan. 45, 359–394.

Blohm, J., Cassens, J., and Wegener, R. (2020). Observation of Communicative Behaviour when Learning a Movement Sequence: Prequel to a Case Study. Kraków: External Credit Assessment Institutions (ECAI).

Bollen, K., and Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: a structural equation perspective. Psychol. Bull. 110, 305–314. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.305

Braun, E., Eshuis, J., and Klijn, E. H. (2014). The effectiveness of place brand communication. Cities 41, 64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2014.05.007

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Biljana, J., and Hollebeek, L. (2011). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: an exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 61, 105–114.

Callender, C., and Melis, G. (2022). The privilege of choice: how prospective college students’ financial concerns influence their choice of higher education institution and subject of study in England. J. High. Educ. 93, 477–501. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2021.1996169

Chapleo, C. (2015). Brands in higher education. Int. Stu. Manage. Org. 45, 150–163. doi: 10.1080/00208825.2015.1006014

Chin, W. W. (2010). “How to write up and report PLS analyses” in Handbook of partial least squares. eds. V. E. Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang (Berlin: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg), 655–690.

Cobb-Walgren, C. J., Ruble, C. A., and Donthu, N. (1995). Brand equity, brand preference, and purchase intent. J. Advert. 24, 25–40. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1995.10673481

Comm, J. (2009). Twitter power: How to dominate your market one tweet at a time. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Conway, A., and Yorke, D. A. (1991). Can the marketing concept be applied to the polytechnic and college sector of higher education? Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 4, 23–35. doi: 10.1108/09513559110137811

Coop, W. F. (2004). Brand Identity as a Driver of Brand Commitment. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Cape Town: Cape Technikon.

Cova, B., and Pace, S. (2006). Brand community of convenience products: new forms of customers empowerment – the case of my Nutella community. Eur. J. Mark. 40, 1087–1105.

Daily, C. M., Farewell, S., and Kumar, G. (2010). Factors influencing the university selection of international students. Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 14, 59–76.

Dholakia, R. R. (2017). Internal stakeholders’ claims on branding a state university. Serv. Mark. Q. 38, 226–238. doi: 10.1080/15332969.2017.1363580

Dholakia, U. M., Bagozzi, R. P., and Pearo, L. K. (2004). A social influence model of consumer participation in network-and small-group-based virtual communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 21, 241–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2003.12.004

Ebrahim, R., Ghoneim, A., Irani, Z., and Fan, Y. (2016). A brand preference and repurchase intention model: the role of consumer experience. J. Mark. Manag. 32, 1230–1259. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2016.1150322

Erdem, T., and Swait, J. (1998). Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. J. Consum. Psychol. 7, 131–157. doi: 10.1207/s15327663jcp0702_02

Erdogmus, I., and Ergun, S. (2016). Understanding university brand loyalty: the mediating role of attitudes towards the department and university. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 229, 141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.123

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Godey, B., Manthiou, A., Pederzoli, D., Rokka, J., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., et al. (2016). Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 69, 5833–5841. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.181

Hemsley-Brown, J., and Goonawardana, S. (2007). Brand harmonization in the international higher education market. J. Bus. Res. 60, 942–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.019

Hemsley-Brown, J., and Oplatka, I. (2016). Higher education consumer choice. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., and Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116, 2–20. doi: 10.1108/imds-09-2015-0382

Hlavinka, K., and Sullivan, J. (2011). Urban legends: Word-of-mouth myths, madvocates and champions. Available online at: www.colloquy.com/files/2011-COLLOQUY-Talk-Talk-White-Paper.pdf/ (accessed December 15, 2012).

Jara, M., and Cliquet, G. (2012). Retail brand equity: conceptualization and measurement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 19, 140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2011.11.003

Kane, G. C., Fichman, R. G., Gallaugher, J., and Glaser, J. (2009). Community relations 2.0. Harv. Bus. Rev. 87, 45–132

Kazaishvili, A. (2022). The impact of the communicative behaviour in social media on the university brand image. Int. J. Manag. Knowl. Learn. 11, 135–143. doi: 10.53615/2232-5697.11.135-143

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 57, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/002224299305700101

Keller, K. L. (2003a). Brand synthesis: the multidimensionality of brand knowledge. J. Consum. Res. 29, 595–600. doi: 10.1086/346254

Keller, K. L. (2003b). Strategic Brand Management: Building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Keller, K. L., and Brexendorf, T. O. (2019). “Measuring brand equity” in Handbuch Markenführung. ed. F. R. Esch (Wiesbaden: Springer Reference Wirtschaft, Springer Gabler), 1409–1439.

Lee, K. (2017). City brand competitiveness: Exploring structural relationships among city brand equity elements in China. (eds.). Int. J. Bus. Econ. Res, 6, 32–39.

Lipsman, A., Mudd, G., Rich, M., and Bruich, S. (2012). The power of ‘like’. How brands reach (and influence) fans through social-media marketing. J. Advert. Res. 52, 40–52. doi: 10.2501/JAR-52-1-040-052

Lovelock, C. H., and Rothschild, M. L. (1980). Uses, abuses, and misuses of marketing in higher education. Marketing in College Admissions: A broadening of perspectives. New York, NY: The College Board.

Mangold, W. G., and Faulds, D. J. (2009). Social media: the new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 52, 357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.03.002

McAlexander, J. H., Schouten, J. W., and Koenig, H. F. (2002). Building brand community. J. Mark. 66, 38–54. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.66.1.38.18451

Mourad, M., Meshreki, H., and Sarofim, S. (2020). Brand equity in higher education: comparative analysis. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 209–231. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1582012

Mulyawan, I., and Kusdibyo, L. (2021). The importance of social media content in influencing the intention to enroll in higher education. In International Joint Conference on Science and Engineering 2021 (IJCSE 2021) (pp. 750–755). Atlantis Press.

Naaman, M., Becker, H., and Gravano, L. (2011). Hip and trendy: Characterizing emerging trends on Twitter. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62, 902–918. doi: 10.1002/asi.21489

Nambisan, S., and Baron, R. A. (2009). Virtual customer environments: testing a model of voluntary participation in value co-creation activities. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 26, 388–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2009.00667.x

Nandan, S. (2005). An exploration of the brand identity brand image linkage: a communications perspective. Brand Manag. 12, 264–278. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540222

Nilson, T. H., and Surrey, N. C. L. (1998). Competitive branding: Winning in the market place with value-added brand. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Padlee, S., Kamaruddin, A., and Baharun, R. (2010). International students’ choice behavior for higher education at Malaysian private universities. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2, 202–211. doi: 10.5539/ijms.v2n2p202

Pawar, S. K. (2024). Social media in higher education marketing: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Cogent Bus Manag 11:20. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2024.2423059

Peruta, A., and Shields, A. B. (2018). Marketing your university on social media: a content analysis of Facebook post types and formats. J. Mark. High. Educ. 28, 175–191. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2018.1442896

Petty, R. E., and Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Plungpongpan, J., Tiangsoongnern, L., and Speece, M. (2016). University social responsibility and brand image of private universities in Bangkok. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 30, 571–591. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-10-2014-0136

Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., and Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 26, 332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2009.08.001

Richter, A., Koch, M., and Krisch, J. (2007). Social commerce: Eine Analyse des Wandels im E-commerce. Fak. für Informatik, Univ. der Bundeswehr München.

Sagynbekova, S., Ince, E., Ogunmokun, O. A., Olaoke, R. O., and Ukeje, U. E. (2020). Social media communication and higher education brand equity: the mediating role of eWOM. J. Public Aff. 22, 1–9. doi: 10.1002/pa.2112

Sashi, C. M. (2012). Customer engagement, buyer-seller relationships, and social media. Manag. Decis. 50, 253–272. doi: 10.1108/00251741211203551

Schivinski, B., and Dąbrowski, D. (2013). The effect of social-media communication on consumer perceptions of brands. Gdańsk: GUT FME Working Paper Series.

Shau, H. J., Muniz, A. M. J., and Arnould, A. J. (2009). How brand community practices create value. J. Mark. 73, 30–51. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.5.30

Sigala, M., and Marinidis, D. (2009). Exploring the transformation of tourism firms’ operations and business models through the use of web map services. Paper presented at the European and Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems 2009 (EMCIS 2009), July 13–14, Izmir. Available online at: www.iseing.org/emcis/cdromproceedingsrefereedpapers/proceedings/presenting/20papers/c72/c72.pdf/ (accessed January 22, 2013).

Smith, S. (2003, 2003) in Brands and branding. eds. R. Clifton and J. Simmons (London: The Economist Newspaper Ltd).

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., and Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 48, 159–205. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005

Thackeray, R., Neiger, B. I., Hanson, C. L., and McKenzie, J. F. (2008). Enhancing promotional strategies within social marketing programs: use of web 2.0 social media. Health Promot. Pract. 9, 338–343. doi: 10.1177/1524839908325335

Ummah, B. (2019). Strategi Image Branding Universitas Nurul Jadid di Era Revolusi Industri 4.0. Tarbiyatuna 12, 59–81. doi: 10.36835/tarbiyatuna.v12i1.352

Van Gelder, S. (2003). Global brand strategy: Unlocking brand potential across countries, cultures and markets. London: Kogan Page Limited.

Vollmer, T., and Precourt, O. (2008). Always on: advertising has a new canvas—and a new attitude. J. Advert. Res. 48, 24–30.

Vrontis, D., El Nemar, S., Ouwaida, A., and Shams, S. M. R. (2018). The impact of social media on international student recruitment: the case of Lebanon. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 11, 79–103. doi: 10.1108/JIEB-05-2017-0020

Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., and Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q., 177–195. doi: 10.2307/20650284

Wijaya, B. S. (2013). Dimensions of brand image: a conceptual review from the perspective of brand communication. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 5, 55–65. doi: 10.13140/ejbm.2013.55.65

Williams, R. L., and Omar, M. (2014). How branding process activities impact brand equity within higher education institutions. J. Mark. High. Educ. 24, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2014.920567

Keywords: social media communication, brand image, international students, enrollment intention, higher education, academic reputation, internationalization, cultural diversity

Citation: Li S, Quan Y, Xiao L, Ren H and Abinova AY (2025) Exploring the influence of social media communication and brand image on international student enrollment intentions in higher education. Front. Educ. 10:1618524. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1618524

Edited by:

Jiayi Wang, De Montfort University, United KingdomReviewed by:

R. K. Dwivedi, GLA University, IndiaCharitha Perera, Northumbria University, United Kingdom

Pratiwi Ramlan, Universitas Muhammadiyah Sidenreng Rappang, Indonesia

Rohit Vishal Kumar, International Management Institute Bhubaneswar, India

Copyright © 2025 Li, Quan, Xiao, Ren and Abinova. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haixia Ren, cmVuaHgwNjE4QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Alfiya Yuriyevna Abinova, d2lsc29uX3Y5OUAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Shuwu Li

Shuwu Li Yuzhen Quan

Yuzhen Quan Liqing Xiao

Liqing Xiao Haixia Ren

Haixia Ren Alfiya Yuriyevna Abinova5*

Alfiya Yuriyevna Abinova5*