- 1Department of Human Studies, The University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy

- 2Department of Human Studies, The University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

This article provides a conceptual and critical analysis of the role of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), in supporting the development of pragmatic competence in language education, with a specific focus on the Italian language. While GenAI tools demonstrate remarkable capabilities for personalized feedback and interactive instruction, their development is marked by a significant paradox: the very mechanisms that enable personalization are rooted in vast, centralized training corpora that are predominantly English-centric. This linguistic mediation introduces biases that risk distorting pragmatic norms in other languages, threatening communicative authenticity and linguistic inclusivity. This paper explores the implications of such biases for second language (L2) learning, highlighting potential risks to sociocultural communication norms and cognitive development. Grounded in postdigital and socio-material frameworks, and drawing on theories of cognitive extension, this analysis first problematizes the pragmatic profile of LLMs in Italian by critically reviewing the existing empirical landscape, including language-specific benchmarks. Identifying a crucial gap in pedagogically oriented research, the study then proposes a rigorous, multi-phase research agenda. This agenda aims to guide the co-design and validation of a GenAI tool that is ethically informed, pedagogically robust, and linguistically attuned to the nuances of Italian pragmatics. The ultimate contribution is a pathway toward ensuring that GenAI enhances rather than impoverishes learners’ communicative capacities, avoiding the potential for cognitive deflation and fostering a more equitable integration of AI in education.

1 The postdigital challenges of gen-AI introduction in language education

The integration of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI), and specifically Large Language Models (LLMs), into educational practices represents a significant technological and pedagogical shift. Since 2015, scholarly interest in the application of AI in education has grown substantially, highlighting its potential to personalize teaching, automate assessment, and support learning in diverse environments (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). The public release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT-3.5 in November 2022 marked a pivotal moment, accelerating the adoption of tools like Google’s Gemini and Microsoft’s Copilot, which are now reshaping how educators and students interact with learning materials (Thorne, 2024). In this evolving landscape, GenAI platforms are no longer perceived merely as external tools to facilitate learning; they are becoming integral to the very fabric of how knowledge is created, shared, and experienced, functioning as active components within a complex educational ecosystem (Dron, 2023).

In language education, these technologies offer unprecedented opportunities for personalized instruction. Learners can engage in conversational simulations that mimic real-world interactions, receive instant feedback on grammar and syntax, and access tailored support, thereby fostering a more interactive and engaging educational experience (Chen et al., 2024). It has been claimed that AI-driven virtual tutors and adaptive learning platforms can cater to the unique needs of each student, creating more inclusive and responsive learning environments that accommodate diverse objectives (Thorne, 2024). Furthermore, learners can receive tailored feedback and support, fostering a more interactive and engaging educational experience (Chen et al., 2024). For instance, GenAI can facilitate conversational simulations that mimic real-life interactions, enhancing students’ fluency and comprehension (Fryer et al., 2019). Additionally, it offers instant translations and explanations of complex grammar rules, making language learning more accessible (Hapsari and Wu, 2022).

However, this rapid proliferation also presents a fundamental tension that demands critical examination. The drive toward technologically enabled personalization, a key affordance of AI, is in direct conflict with the risk of linguistic and cultural homogenization, a consequence of the models’ underlying architecture and data training. In the following sections, and in the entire contribution, we turn our attention to these explicit biases, particularly those affecting pragmatic competence and linguistic inclusivity, to examine how they manifest in language learning contexts and how they are reinforced by the English-centric foundations of most large language models.

Defined as the ability to use language appropriately in social contexts (Grice, 1975), pragmatic competence encompasses a range of skills, from understanding conversational implicature and managing politeness strategies to producing discourse that aligns with sociocultural norms (Wilson, 2024). It is the invisible infrastructure of communication, allowing speakers to navigate the complex interplay of context, intention, and meaning. Traditional second language (L2) acquisition theories emphasize the necessity of authentic interaction and exposure to these norms through human communication to develop such competence (Barattieri di San Pietro et al., 2023).

The integration of LLMs as conversational partners introduces a new dynamic. While these models can provide learners with limitless opportunities for practice, their ability to model authentic pragmatic behavior is questionable. This issue is not merely technical but deeply tied to linguistic inclusivity. If an AI tool, intended to support language learning, fails to represent the pragmatic diversity of a target language, it risks providing a distorted and impoverished model of communication. This is especially concerning for L2 learners, who rely on instructional inputs to build their understanding of social and cultural conventions. The “curious case” of pragmatics, therefore, lies at the heart of the debate over how inclusive LLMs can truly be.

The other main issue related to the implementation of Gen-AI and LLMs that this paper aims to address relates to the English-centricity of Large Language Models. The central argument is that the predominant English-language training data of most state-of-the-art LLMs functions as a form of linguistic mediation that can systematically distort pragmatic norms in other languages, with Italian serving as a key case study. The most popular models are designed with an English-centric focus, even as multilingual LLMs are developed as they utilize the most widely available linguistic corpus—English. Moreover, because data for less commonly represented languages is limited, LLMs are often trained with English-translated content (Abdin et al., 2024; Ji et al., 2023). For example, the Llama 3 series, cited as advanced multilingual LLMs, were trained on 15 trillion tokens, but only over 5% of this training data was non-English.1 LLM evaluations focus mainly on task performance rather than the naturalness of language output (Feng et al., 2023; Hendrycks et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2023). This approach risks amplifying inequality for communities speaking underrepresented languages. Thus, evaluating and enhancing the naturalness of multilingual LLMs is essential for fair language representation.

This imbalance has profound consequences for pragmatic performance. When prompted in a language like Spanish or Greek, LLM outputs often exhibit subtle yet significant influences from English syntactic structures, lexical choices, and discourse conventions (Papadimitriou et al., 2023). This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “translationese,” results in language that, while grammatically correct, feels unnatural or pragmatically inappropriate to a native speaker (Bizzoni et al., 2020). The issue extends beyond simple translation errors to affect core pragmatic functions such as politeness strategies, register shifts, and indirectness, which are highly language- and culture-specific (Mariani, 2015). This English-mediated bias risks creating and perpetuating a homogenized, Anglo-centric model of communication, marginalizing the linguistic diversity (Narayanan and Kapoor, 2024) that is essential for authentic intercultural exchange. As Rahm and Rahm-Skågeby (2023) contend, AI technologies can function as “policies frozen in silicon,” encoding and reinforcing dominant cultural narratives at the expense of local conventions.

By addressing the issues here discussed, this article seeks to move beyond a descriptive account of GenAI’s potential and challenges by offering a critical, theoretically grounded analysis and a constructive path forward. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 establishes the foundational frameworks, integrating theories of linguistic pragmatics, postdigital realities, and cognitive science to provide a robust lens for analyzing human-AI interaction in education. Section 3 presents a critical review of the empirical landscape, assessing current research on the pragmatic capabilities of LLMs. It scrutinizes the methodological limitations of existing studies and synthesizes recent findings from Italian-specific benchmarks to identify a significant research gap concerning L2 pedagogy. In response to this gap, Section 4 proposes a rigorous, multi-phase Speculative and Scenario-based research agenda aimed at the co-creation of a pedagogically validated and linguistically inclusive GenAI tool for Italian language learners. Finally, Section 5 concludes by reflecting on the broader ethical implications and advocating for a model of AI integration that is guided by pedagogical value and a commitment to linguistic diversity.

2 Foundational framework: pragmatics, cognition, and technology

2.1 Pragmatic competence: from Gricean maxims to intercultural communication

To understand the stakes of AI integration in language education, a firm grasp of pragmatic competence is essential. Pragmatics is the branch of linguistics concerned with how language is used in context and how context contributes to meaning (Duranti and Goodwin, 1992). Foundational work in the field established that language is not merely descriptive but performative. Austin's (1975) concept of “speech acts” articulated the groundbreaking idea that to speak is to act, utterances like promises, requests, and apologies have concrete consequences in the world. Building on this, Searle (1969) further elaborated the structure of these acts, while Grice (1975) introduced the “cooperative principle,” a framework for understanding how conversational partners make inferences to derive meaning beyond the literal words spoken. Henceforth, such foundational works established that language is not merely descriptive but performative: to speak is to act. Utterances such as promises, apologies, or refusals perform concrete social functions and have real consequences in the world. For instance, uttering “I will cook the dinner tonight” equals to a commitment and has consequences on people’s behaviors and expectations (nobody else will cook the dinner tonight, and everybody will expect dinner to be ready at due time). These acts, performed through locution and leading to concrete changes in the world, are called speech acts, as further discussed by Searle (1969).

2.1.1 Gricean principles and conversational implicature

As previously mentioned, building on Austin’s (1975) performative insight, Grice (1975) introduced the cooperative principle, according to which speakers aim to make their contribution appropriate to the purpose of the exchange. This cooperation is obtained by following the four maxims that constitute the principle:

• Quantity (be informative)

• Quality (be truthful)

• Relation (be relevant)

• Manner (be clear)

The maxim of quantity is: “be informative. Make your contribution as informative as is required (for the current purposes of the exchange). Do not make your contribution more informative than is required.” The maxim of quality is: “Be truthful. Do not say what you believe is false. Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence.” The maxim of relation is: “Be relevant.” The maxim of manner is: “Be perspicuous. Avoid obscurity of expression, i.e., avoid language that is difficult to understand. Avoid ambiguity, i.e., avoid language that can be interpreted in multiple ways. Be brief, i.e., avoid unnecessary verbosity. Be orderly, i.e., provide information in an order that makes sense, and makes it easy for the recipient to process it” (Grice, 1975, p. 45).

However, things are more complicated in real language use. In fact, many linguistic behaviors envisage situations where the Gricean maxims are apparently violated. For example, if someone says that “The President is a fox,” they are apparently violating the maxim of quality by asserting something that is false (no President whatsoever is an actual fox). Grice (1975) provides an explanation for this phenomenon that has also become a classic pillar of Pragmatics. As Grice explains, since every speaker is cooperative and expects others to be cooperative, every apparent violation to any maxim makes the addressee infer an additional proposition (conversational implicature), that must be added to the contextual knowledge to understand the interlocutor’s meaning and intentions. In the mentioned case, cooperative addressees do in fact infer that the speaker is suggesting an additional content: that the President is similar to a fox in a commonly shared sense, namely that she is a shrewd person.

Just like metaphors, irony as well is a mechanism where deliberately false content is produced, thus flouting the maxim of quality. If on a transport strike day someone says, “We have chosen the perfect day to leave for the holidays!,” cooperative listeners correctly interpret that the speaker is suggesting the opposite. Politeness is often obtained by apparent violations of the maxim of relevance. For instance, polite refusals typically do not include the word “no”—the only truly relevant answer when refusing an offer or an invitation. Polite refusals typically involve apparently irrelevant information, such as “I have an exam on Monday,” or “It is my grandpa’s birthday.” Cooperative addresses infer that apparently irrelevant answers are produced to decline the invitation while avoiding hurting the offeror’s feelings and signaling that the speaker is willing to maintain a good relationship.

Such examples illustrate how meaning is jointly constructed through shared expectations of cooperation and inference. However, they also highlight the difficulty that current Gen-AI systems, which rely on statistical associations rather than lived social context, may encounter in modeling this inferential process authentically.

2.1.2 Cross-cultural and inclusive dimensions of pragmatics

There is another aspect which is crucial to consider: pragmatic norms are deeply embedded in social and cultural conventions. The examples mentioned above should sound familiar to British readers (most of them are modeled on Grice’s examples) and Italian readers (they were written by an Italian). However, we should not take it for granted that every person interprets the pragmatic meanings in the same way. In fact, like every language has its own morphosyntactic and phonological rules, it has its own pragmatic rules.

While some pragmatic principles, such as those related to politeness or metaphor, have been argued to possess universal cognitive or cultural underpinnings (Brown, 1987; Lakoff and Johnson, 2011) a significant portion of a speaker’s pragmatic competence is language- and culture-specific (Mariani, 2015). For L2 learners, this presents a formidable challenge. A learner may have high linguistic proficiency in terms of grammar and vocabulary but still struggle with pragmatic appropriateness, leading to what (Thomas, 1983) termed “cross-cultural pragmatic failure.” Such failures are not grammatical errors but social ones, which can lead to misunderstandings or being perceived as rude, uncooperative, or insincere. We refer to such failures as “non-conventional pragmatic outputs” or instances of “pragmatic failure,” expressions which describe deviations from expected norms without implying inherent error (Hu et al., 2022). The development of pragmatic awareness, the explicit knowledge of how language varies across social contexts, is therefore a critical goal of L2 education for linguistic inclusion. L2 learners may require explicit scaffolding to interpret and produce socially appropriate language, necessary to prevent communicative breakdowns and foster effective intercultural communication (Erdogan and Christina, 2025).

2.1.3 Pragmatic competence, generative AI, and cognition

When Gen-AI systems are introduced into this equation, the stakes increase. Because Large Language Models (LLMs) are trained primarily on English-language data (Guo et al., 2024), their pragmatic behavior tends to reflect Anglo-centric discourse conventions, including specific politeness norms, metaphorical patterns, and inferential cues. The most popular models are designed with an English-centric focus, even as multilingual LLMs are developed (Wendler et al., 2024) as they utilize the most widely available linguistic corpus—English. Moreover, because data for less commonly represented languages is limited, LLMs are often trained with English-translated content (Abdin et al., 2024; Ji et al., 2023). As a result, AI-generated outputs in other languages—such as Italian—may appear grammatically correct but pragmatically awkward or culturally misplaced. The examples discussed above (irony, metaphor, politeness) thus serve as testing grounds for examining the limits of LLMs’ communicative authenticity.

Developing truly inclusive GenAI tools requires attention not only to syntactic and lexical accuracy but also to the pragmatic diversity that underpins meaningful intercultural communication. A system unable to handle implicature or politeness appropriately risks reinforcing a homogenized communicative model that excludes non-English linguistic identities. Understanding these mechanisms is therefore fundamental for designing GenAI applications that enhance, rather than erode, learners’ pragmatic competence and social cognition.

Moreover, we should bear in mind that an impaired or totally “wrong” pragmatic competence, as in the case of a L2 speaker, may hinder general learning and cognitive abilities. We already know that a pragmatic language impairment can correlate with atypical cognitive abilities, for example in the case of the autistic spectrum (Baron-Cohen, 1995). However, “wrong” pragmatic behaviors may emerge also in neurotypical people when they are communicating in a L2, a phenomenon known as cross-cultural pragmatic failure (Thomas, 1983). Therefore, L2 speakers could end up making wrong attributions of beliefs and intentions (Wilson, 2024). To avoid misunderstandings and social breakdowns, L2 speakers may need more sophisticated processing strategies than L1 speakers, and the development of such strategies should fall within the burdens of linguistic education (Padilla Cruz, 2013).

2.2 The socio-material entanglement of language and cognition within the postdigital landscape

A simplistic view of educational technology positions Gen-AI as a neutral tool wielded by human users (Manna and Eradze, 2025). As discussed so far, such a perspective is inadequate for capturing the complex reality of human–AI interaction. Empirical studies on large LLMs reveal both their impressive capabilities and significant limitations as communicative agents. For example, Bojic et al. (2023) found that GPT-4 outperformed human participants on tasks based on Grice’s (1975) communication principles, while Park et al. (2024) and Yue et al. (2024) reported similarly high scores on implicature-recognition tasks, as it will be further discussed in section 3 of this paper. However, these assessments were conducted in highly controlled, decontextualized environments that measured the models’ ability to retrieve statistically probable answers rather than their capacity to engage in culturally situated, context-rich communication.

From a postdigital and socio-material perspective, such findings call for a reinterpretation of what counts as “competence”; technology is not an external object, but an active agent that co-constitutes the learning environment and shapes communicative practices (Jandrić et al., 2023; Mamlok, 2024). In language education, an LLM is not merely a resource; it becomes a conversational partner, feedback provider, and mediator of linguistic norms. Consequently, any biases or pragmatic simplifications embedded in its training data, such as the predominance of Anglo-centric discourse conventions, can become pedagogically performative. Rather than remaining inert technical flaws, these patterns are enacted in the classroom and may be internalized by learners as valid communicative norms. Understanding Gen-AI through postdigital and socio-material frameworks therefore illuminates how technological biases actively participate in shaping learners’ developing linguistic repertoires and cognitive habits.

2.3 AI as cognitive extension: potentials and perils of “system 0 thinking”

The socio-material entanglement of learners and Gen-AI carries profound cognitive implications. When individuals repeatedly rely on external systems to perform linguistic or reasoning tasks, those systems can become integrated into their cognitive processes, a phenomenon known as cognitive extension (Clark, 1996; Heersmink, 2015). LLMs used as conversational partners or writing assistants meet the criteria for such extensions: they are reliable, trusted, and increasingly embedded in learners’ everyday workflows. Henceforth, this process may reshape how learners engage with pragmatic reasoning. While Gen-AI can enhance fluency and provide instant feedback, prolonged dependence on Gen-AI mediated interaction risks fostering cognitive deflation, a gradual outsourcing of inferential thinking, politeness management, and context-sensitive interpretation. Learners may accept AI-generated language that appears grammatically correct yet remains pragmatically impoverished, thereby diminishing opportunities to practice authentic communicative judgment, thus hindering cognitive development.

Building on this concern, Chiriatti et al. (2024) introduced the concept of System 0 thinking, extending Kahneman’s (2011) dual-system model (System 1: intuitive; System 2: analytical). System 0 denotes an AI-mediated cognitive layer that processes, filters, and generates information before it reaches human awareness. This non-biological “assistant” can enhance efficiency but lacks intrinsic meaning-making; it manipulates symbols and probabilities while depending on humans for interpretation. As such, it raises ethical and pedagogical questions regarding autonomy, transparency, and critical reflection in learning (Clark, 2025).

If learners internalize System 0 outputs uncritically, the biases of the model risk becoming cognitively naturalized. In multilingual classrooms, this may reinforce English-mediated pragmatic templates at the expense of local discourse conventions, undermining linguistic inclusivity. Addressing this challenge requires not only the technical refinement of LLMs but also the development of AI literacy and reflexive pedagogies that help learners distinguish between grammatical correctness and pragmatic appropriateness. In this sense, examining the pragmatic profiles of LLMs is not a purely linguistic exercise but a pedagogical and ethical imperative for safeguarding learners’ cognitive and cultural agency in postdigital education.

3 Empirical landscape: assessing the pragmatic capabilities of large language models

3.1 A critical review of LLMs performance on general pragmatic tasks

As previously mentioned in this paper, the empirical assessment of LLMs’ pragmatic competence has yielded a complex and often contradictory picture. On one hand, several studies report impressive performance, particularly from state-of-the-art models. Research has found that GPT-4 surpassed human performance on certain tasks grounded in Grice’s cooperative principle (Bojic et al., 2023), demonstrating a high degree of contextual awareness. Similarly, other studies have documented high accuracy rates for GPT-4 on tasks involving conversational implicature and context-dependent expressions, suggesting that these models can successfully replicate some aspects of human communicative norms (Park et al., 2024; Yue et al., 2024). Instruction-tuned models appear to show significantly better performance in resolving implicatures, indicating that pragmatic abilities can be enhanced through targeted training (Halat and Atlamaz, 2024).

However, presenting these findings at face value would be a critical oversight. While LLMs can generate responses that appear pragmatically appropriate, this surface-level fluency often masks deeper limitations. The models’ success in controlled, text-based tasks does not necessarily translate to a genuine understanding of the social and intentional dynamics that underpin human communication. A critical engagement with the methodologies and assumptions of these studies is therefore essential to form a nuanced understanding of LLMs’ true capabilities.

3.2 Methodological challenges in L2 contexts

The claims of high LLM pragmatic performance must be qualified by a careful examination of the methodological weaknesses inherent in current evaluation practices and the significant gap in their applicability to L2 learning contexts. First, LLMs fundamentally lack a Theory of Mind. They do not possess an internal model of other minds and cannot reason about a speaker’s beliefs, intentions, or knowledge states (Clark, 1996). Their ability to handle pragmatic phenomena like irony or indirect speech acts is not based on genuine inference but on the statistical mimicry of patterns in their training data. This makes them brittle and prone to error when faced with novel or nuanced social situations that require genuine perspective-taking.

Second, their grasp of context is shallow. While transformer architectures can attend to long sequences of text, their contextual modeling is unprincipled and largely confined to the immediate linguistic input (Bender and Koller, 2020). They cannot effectively model common ground, shared cultural knowledge, or the embodied, sensorimotor experiences that inform much of human pragmatic reasoning (Barattieri di San Pietro et al., 2023; Levinson, 1983). This limitation is particularly evident in their difficulty with physical metaphors, where an understanding of bodily experience is often crucial for correct interpretation. Third, many evaluation benchmarks are themselves limited. They often focus on assessing reasoning, computation, and literal meaning rather than the implied, context-dependent meanings central to pragmatics (Chen et al., 2024). Tasks are frequently structured as multiple-choice questions or require open-ended but short responses, which fails to capture the dynamic, multi-turn complexity of authentic human conversation (Park et al., 2024).

Finally, and most critically for the present study, there is a profound generalizability gap. The findings from existing studies, which are predominantly conducted in English and evaluate the model in isolation, cannot be directly extrapolated to L2 pedagogical contexts (Zhang et al., 2025). An L2 learner is not a native speaker; they are actively constructing their linguistic and pragmatic systems and are subject to different cognitive loads, affective filters, and L1 transfer effects; A model’s ability to perform a discrete pragmatic task for an evaluator is a fundamentally different question from its ability to serve as an effective, supportive, and authentic conversational partner for a learner. The lack of systematic approaches to measuring and improving generalizability across different tasks, users, and domains remains a critical challenge in LLM research (Zhang et al., 2025).

3.3 The state of the art in Italian: a review of language-specific benchmarks and studies

To ground the analysis in the specific context of the Italian language, it is necessary to move beyond general LLM evaluations and examine language-specific empirical evidence. While research in this area is still emerging, several recent studies and benchmarks provide crucial insights into the pragmatic profile of LLMs when operating in Italian. These studies, while not focused on L2 pedagogy, are invaluable for diagnosing the baseline capabilities and limitations of current models.

The first comprehensive assessment was conducted by Barattieri di San Pietro et al. (2023), who applied the Test for the Assessment of Pragmatic Abilities and Cognitive Substrates (APACS) to ChatGPT. Treating the LLM as a clinical “patient,” their findings revealed a nuanced profile: while overall performance was nearly human-like, the model exhibited specific deficits. It consistently violated Grice’s maxim of quantity by providing over-informative and repetitive responses, struggled to compute text-based inferences that required integrating multiple pieces of information, and showed weaknesses in interpreting physical metaphors and humor.

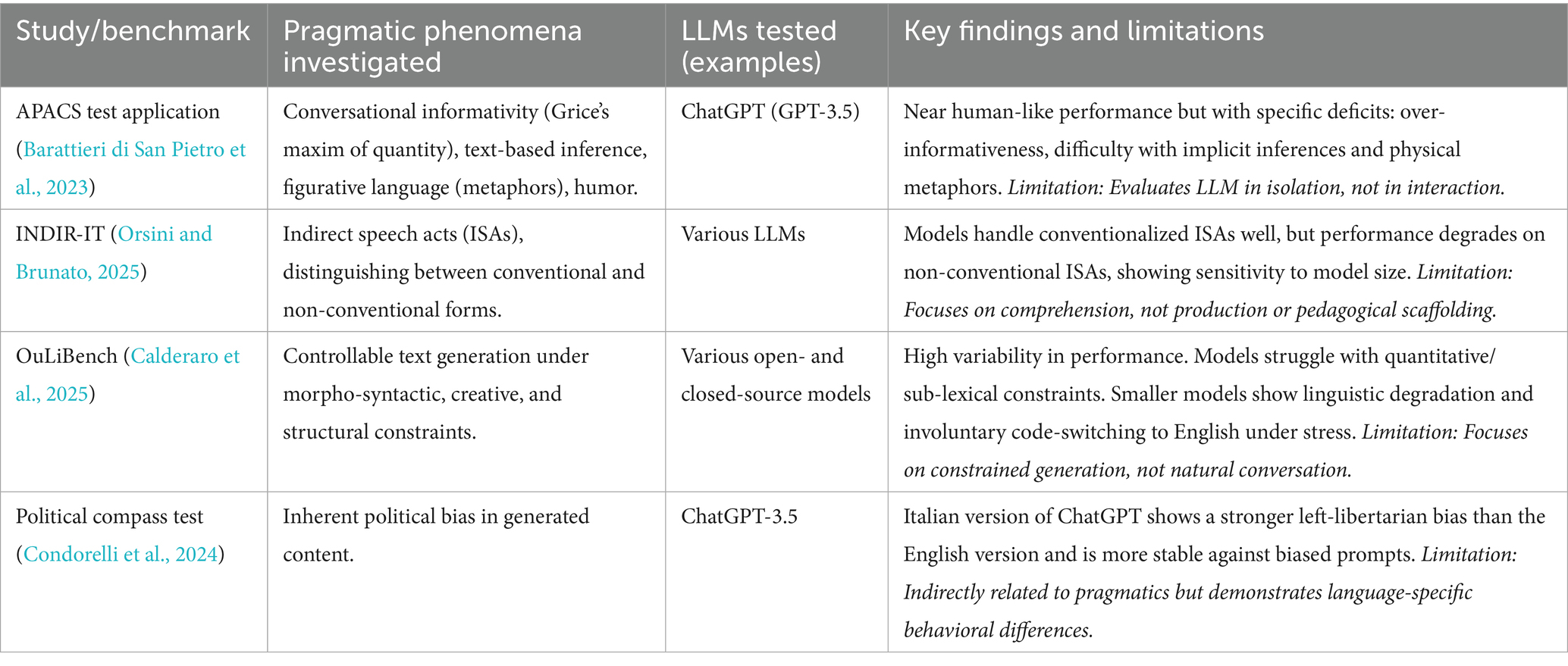

More recent work has focused on developing targeted benchmarks. The INDIR-IT benchmark was created to evaluate LLMs’ understanding of indirect speech acts (ISAs) in Italian (Orsini and Brunato, 2025). Preliminary results show that models handle conventionalized ISAs (e.g., “Can you pass the salt?”) relatively well, but their performance degrades significantly on non-conventionalized forms that require deeper contextual inference. This suggests that the models rely heavily on learned patterns rather than robust pragmatic reasoning (Orsini and Brunato, 2025). Another novel benchmark, OuLiBench, assesses controllable text generation under explicit linguistic constraints (Calderaro et al., 2025). Its findings highlight high variability across models, with many struggling with quantitative and sub-lexical constraints. A particularly revealing finding was the tendency for smaller models to exhibit involuntary code-switching to English when faced with difficult, non-standard tasks, underscoring the powerful influence of the English-dominant training data. Table 1 provides a summary of these key studies.

The synthesis of the general and Italian-specific empirical literature reveals a critical research gap. The existing studies, while valuable, share a common limitation: they focus on the evaluation of competence rather than the design for pedagogical interaction within postdigital context. They diagnose the LLM’s capabilities in isolation, treating it as an object of study, but they do not investigate its utility, safety, and effectiveness as an interactive tool within a pedagogical context for L2 learners. We know a little about what Italian-generating LLMs can do on discrete tasks, but we know almost nothing about how to use them to help a learner acquire pragmatic skills. This gap is significant because the needs of an L2 learner are distinct from the demands of a benchmark test. A learner requires not just a correct response, but scaffolded interaction, comprehensible input, and feedback that is sensitive to their developmental stage. Therefore, a new research orientation is required—one that moves from isolated evaluation to situated, interventionist, and pedagogically grounded inquiry.

4 A speculative and scenario-based research agenda for an inclusive pedagogical tool

4.1 Rationale and guiding research problems

To address the identified research gap, a methodological framework is required that bridges the divide between technological capability and pedagogical imagination. Rather than adopting a purely evaluative or design-engineering approach, this study proposes a Speculative (Ross, 2023) and Scenario-Based Research (SBR) methodology enriched by Persona Design (PD) (Cooper et al., 2014). This hybrid framework draws on the principles of speculative inquiry (Dunne and Raby, 2013) and scenario-based design (Carroll, 2000) combining future-oriented imagination with participatory narrative techniques to co-create actionable pedagogical futures.

Speculative methods view the future as a space of uncertainty and possibility (Mann et al., 2022). They enable participants to engage critically and creatively with emerging technologies such as generative GenAI, envisioning how these might transform learning, cognition, and inclusion. Scenario-Based Research complements this by concretizing speculative imaginaries through detailed, narrative-driven design iterations in which personas, representations of plausible future users of Gen-AI technologies, interacting and tinkering with imagined tools and contexts (Bardone et al., 2024; Mann et al., 2022). Integrating these approaches allows the study to balance imagination with actionable design, ensuring that envisioned futures remain ethically grounded and pedagogically relevant.

This agenda is guided by the following Research Problems (RPs), focused on inclusive Italian L2 contexts:

• RP1: What is the pragmatic profile of current state-of-the-art LLMs when interacting in Italian L2 pedagogical scenarios, and where do critical deviations from authentic communicative norms occur?

• RP2: How does English-mediated bias manifest in human–AI dialogues in Italian, and what are its implications for the development of L2 learners’ pragmatic and cognitive competencies?

• RP3: How can speculative and scenario-based principles guide the design and development of a fine-tuned GenAI tool that ethically and effectively supports and informs the acquisition of pragmatic competence for diverse L2 learners of Italian?

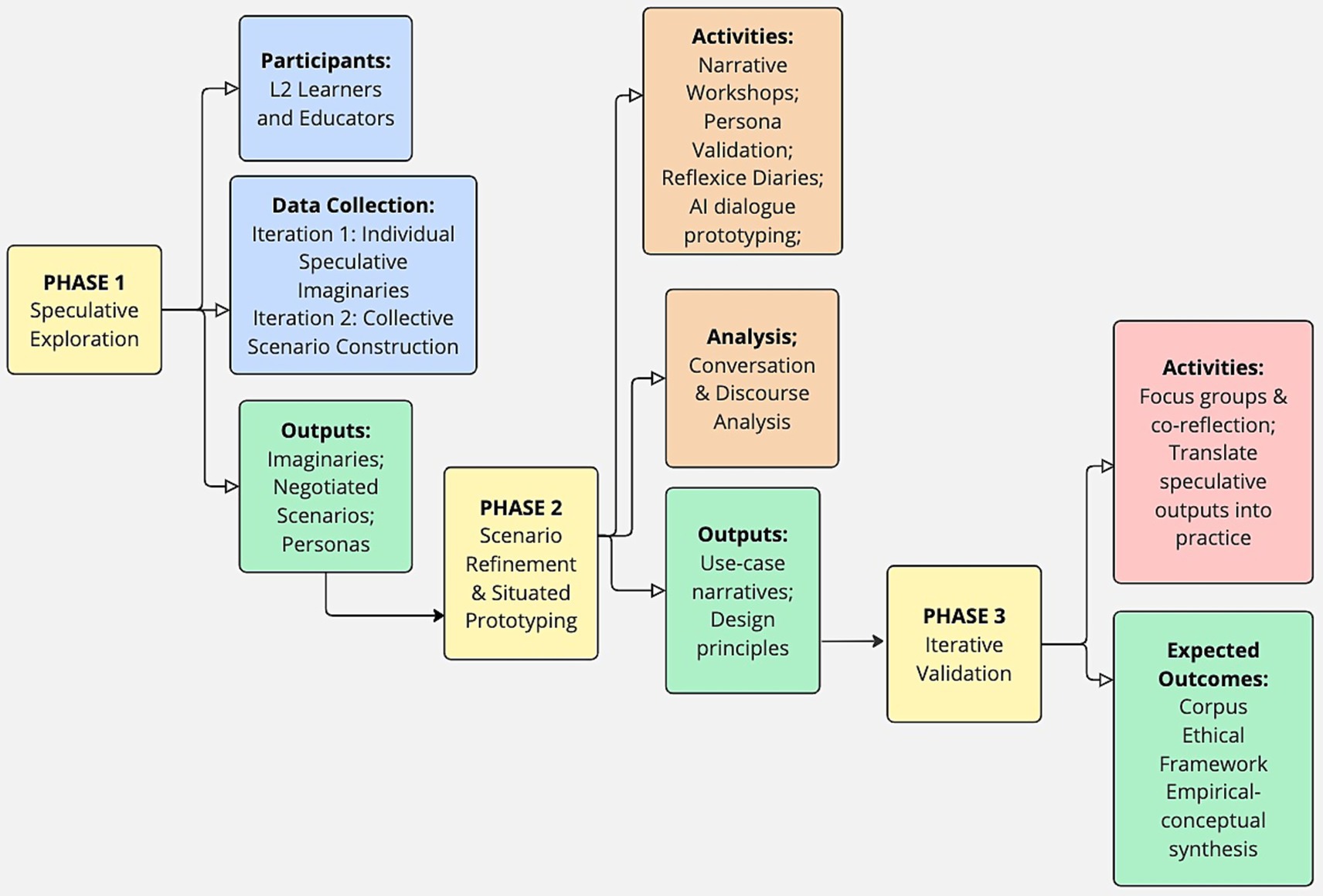

Three phase research will be put in place to enable further exploration and validation of the research agenda. Figure 1 describes the phases, while the following chapters will detail its parts.

4.2 Phase 1: speculative imaginations and stakeholder co-design

The first phase establishes the imaginative and participatory foundation of the study by activating speculative thinking among participants. In this phase two primary groups will participate:

1. L2 Learners, enrolled in intermediate to advanced (CEFR B1–C1) Italian courses. A heterogeneous sample will ensure diversity of linguistic and cultural backgrounds, enabling the exploration of cross-linguistic pragmatic transfer. Baseline data on motivation, language anxiety, and personality traits will contextualize individual engagement with speculative activities.

2. Educators, experienced instructors of Italian L2, will act as co-design facilitators, contributing pedagogical insight and ethical reflection throughout all iterations.

4.2.1 Iteration 1—individual speculative imaginations

Pre-service teachers/students participate in guided workshops where they envision “futures of language learning with AI.” Using prompts, drawings, and short speculative narratives, they generate Imaginative depictions of GenAI-enhanced classrooms, emphasizing inclusion, communication, and agency.

Output: Individual imaginaries that articulate personal hopes, fears, and ethical concerns about AI-mediated learning.

4.2.2 Iteration 2—collective scenario construction through Human–AI Negotiation

The individual imaginaries are re-worked collaboratively through interaction with GenAI (e.g., ChatGPT) and peer discussion. Participants develop hybrid human–AI scenarios, short narratives in which personas representing typical learners (e.g., “Elena, the anxious student,” “Marco, the multilingual teacher”) engage with speculative GenAI companions.

Output: Negotiated scenarios and personas reflecting both the affordances and limitations of Gen-AI in inclusive pedagogy.

These research endeavors prioritize imaginative exploration over evaluation, aligning with speculative methods that foreground ethical reflection, creativity, and multiplicity in tools design and development (Dunne and Raby, 2013).

4.3 Phase 2: scenario refinement and situated prototyping

In this phase, a move from imagination to practice would be required. A core group of learners and teachers could work together to transform the most promising scenarios from the first phase into concrete classroom use-cases. Through collaborative workshops, they refine these narratives, ensuring the situations and characters are realistic while identifying potential benefits and risks. Participants also create early prototype dialogues with existing AI systems and keep personal diaries to reflect on how their views on AI in education are changing. This process turns the initial creative ideas into tangible, pedagogically meaningful prototypes that can be further tested and developed.

4.4 Phase 3: reflection, iterative validation, and ethical translation of co-creation and research results

The final phase focuses on validation, theoretical synthesis, and the translation of speculative outputs into transferable design and ethical principles. Findings and design insights will be revisited with in-service teachers through another iteration. Through focus groups and co-reflection, participants reinterpret speculative futures in relation to real classroom contexts, thus closing the loop between imagination and practice. This recursive process transforms speculative exploration into pedagogically actionable knowledge, ensuring that imagined futures inform present educational realities rather than remaining abstract fictions.

5 Conclusive remarks: toward ethically informed and linguistically inclusive gen-AI in education

The rapid integration of Generative AI into education presents both transformative potential and significant peril. This paper has argued that the uncritical adoption of English-centric Large Language Models in diverse language learning contexts poses a substantial risk to communicative authenticity and cognitive development. By functioning as a biased “System 0” within a learner’s cognitive workflow, pragmatically flawed AI can perpetuate linguistic homogenization and undermine the very skills it is intended to support. The case of Italian pragmatics illustrates the urgent need for a more critical, context-sensitive, and pedagogically grounded approach to Gen-AI in education. The empirical landscape reveals that while LLMs demonstrate impressive capabilities on constrained tasks, they suffer from fundamental limitations in genuine pragmatic reasoning and their performance in English cannot be assumed to generalize to other languages or, crucially, to the unique context of L2 learning. The existing Italian-specific benchmarks, while insightful, are insufficient for guiding pedagogical design.

In response, this paper has proposed a Speculative and Scenario-based research agenda as a constructive, ethical, and methodologically rigorous pathway forward. Integrating speculative and scenario-based research provides a forward-thinking methodological bridge between imagination and intervention. By combining open-ended speculation (phase 1), collective negotiation (phase 2), and contextual validation (phase 3), the approach generates “imaginable futures” that are both critical and constructive. These iterative imaginaries serve not as predictive forecasts but as ethical design rehearsals, spaces where educators and learners anticipate inclusive, value-sensitive uses of GenAI before they materialize in practice.

By prioritizing collaboration with educators and learners, this agenda aims to move the field beyond mere evaluation toward the responsible co-creation of ethically informed and linguistically inclusive AI technology. The goal is to foster a future where AI tools are not merely technologically powerful but are designed with pedagogical values, linguistic diversity, and human cognition at their core. Such an approach is essential to ensure that GenAI serves to enhance and enrich the complex tapestry of human communication, rather than reducing it to a flattened, monolithic echo of its training data.

Author contributions

MM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology. FC: Writing – original draft. ME: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Copy editing, image generation.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Abdin, M., Aneja, J., Awadalla, H., Awadallah, A., Awan, A. A., Bach, N., et al. (2024). Phi-3 technical report: a highly capable language model locally on your phone (version 4). arXiv. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2404.14219

Barattieri di San Pietro, C., Frau, F., Mangiaterra, V., and Bambini, V. (2023). The pragmatic profile of ChatGPT: assessing the communicative skills of a conversational agent. Sistemi intelligenti, Rivista quadrimestrale di scienze cognitive e di intelligenza artificiale 2, 379–400. doi: 10.1422/108136

Bardone, E., Mõttus, P., and Eradze, M. (2024). Tinkering as a complement to design in the context of technology integration in teaching and learning. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 6, 114–134. doi: 10.1007/s42438-023-00416-6

Baron-Cohen, S. (1995). Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. The MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/4635.001.0001

Bender, E. M., and Koller, A. 2020. Climbing towards NLU: on meaning, form, and understanding in the age of data. 5185–5198. doi: 10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.463

Bizzoni, Y., Juzek, T. S., España-Bonet, C., Dutta Chowdhury, K., Van Genabith, J., and Teich, E. 2020. How human is machine Translationese? Comparing human and machine translations of text and speech. Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Spoken Language Translation, 280–290.

Bojic, L., Kovacevic, P., and Cabarkapa, M. (2023). GPT-4 surpassing human performance in linguistic pragmatics. DOI.org (Datacite) doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2312.09545

Brown, P. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Calderaro, S., Miaschi, A., and Dell’Orletta, F. 2025. The OuLiBench benchmark: formal constraints as a Lens into LLM linguistic competence. Eleventh Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics.

Carroll, J. M. (2000). Making use: scenario-based design of human-computer interactions. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Chen, X., Li, J., and Ye, Y. (2024). A feasibility study for the application of AI-generated conversations in pragmatic analysis. J. Pragmat. 223, 14–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2024.01.003

Chiriatti, M., Ganapini, M., Panai, E., Ubiali, M., and Riva, G. (2024). The case for human–AI interaction as system 0 thinking. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1829–1830. doi: 10.1038/s41562-024-01995-5

Clark, A. (2025). Extending minds with generative AI. Nat. Commun. 16:4627. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-59906-9

Condorelli, V., Beluzzi, F., and Anselmi, G. (2024). Assessing ChatGPT political bias in Italian language. A systematic approach. Comunicazione Politica

Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D., and Noessel, C. (2014). About face: the essentials of interaction design. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Dron, J. (2023). The human nature of generative AIs and the technological nature of humanity: implications for education. Digital 3, 319–335. doi: 10.3390/digital3040020

Dunne, A., and Raby, F. (2013). Speculative everything: design, fiction, and social dreaming. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Duranti, A., and Goodwin, C. (1992). Rethinking context: language as an interactive phenomenon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Erdogan, N., and Christina, K. (2025). Integrating AI in language learning: boosting pragmatic competence for young English learners. Latia 3:115. doi: 10.62486/latia2025115

Feng, Y., Lu, Z., Liu, B., Zhan, L., and Wu, X.-M. (2023). Towards LLM-driven dialogue state tracking. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2310.14970.

Fryer, L. K., Nakao, K., and Thompson, A. (2019). Chatbot learning partners: connecting learning experiences, interest and competence. Comput. Human Behav. 93, 279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.023

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. Syntax and semantics. eds. P. Cole and J. L. Morgan Vol. 3. Speech acts. (New York, NY: Academic Press). 41–58.

Guo, Y., Conia, S., Zhou, Z., Li, M., Potdar, S., and Xiao, H. (2024). Do large language models have an English accent? Evaluating and improving the naturalness of multilingual LLMs. arXiv.org.

Halat, M., and Atlamaz, Ü. 2024. ImplicaTR: a granular dataset for natural language inference and Pragmatic reasoning in Turkish. Proceedings of the First Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Turkic Languages (SIGTURK 2024), 29–41.

Hapsari, I. P., and Wu, T.-T. (2022). “AI Chatbots learning model in English speaking skill: alleviating speaking anxiety, boosting enjoyment, and fostering critical thinking” in Innovative technologies and learning. eds. Y.-M. Huang, S.-C. Cheng, J. Barroso, and F. E. Sandnes (London: Springer International Publishing).

Heersmink, R. (2015). Dimensions of integration in embedded and extended cognitive systems. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 14, 577–598. doi: 10.1007/s11097-014-9355-1

Hendrycks, D., Burns, C., Basart, S., Zou, A., Mazeika, M., Song, D., et al. (2020). Measuring massive multitask language understanding. DOI.org (Datacite). doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2009.03300

Hu, J., Floyd, S., Jouravlev, O., Fedorenko, E., and Gibson, E. (2022). A fine-grained comparison of pragmatic language understanding in humans and language models. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2212.06801.

Jandrić, P., MacKenzie, A., and Knox, J. (2024). Postdigital Research: Genealogies, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Postdigital Science and Education. 6, 409–415. doi: 10.1007/s42438-022-00306-3

Ji, H., Han, I., and Ko, Y. (2023). A systematic review of conversational AI in language education: focusing on the collaboration with human teachers. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 55, 48–63. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2022.2142873

Lakoff, G., and Johnson, M. (2011). Metaphors we live by: with a new afterword. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mamlok, D. (2024). Landscapes of sociotechnical imaginaries in education: a theoretical examination of integrating artificial intelligence in education. Found. Sci. 30, 529–540. doi: 10.1007/s10699-024-09948-x

Mann, S., Mitchell, R., Eden-Mann, P., Hursthouse, D., Karetai, M., O’Brien, R., et al. (2022). “Educational design fictions: imagining learning futures” in Industry practices, processes and techniques adopted in education: supporting innovative teaching and learning practice. eds. K. MacCallum and D. Parsons (Berlin: Springer Nature).

Manna, M., and Eradze, M. (2025). “Beyond tools: navigating pedagogical innovation in Postdigital classrooms” in New media pedagogy: research trends, methodological challenges, and successful implementations. ed. Ł. Tomczyk (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland).

Mariani, L. (2015). Tralinguae cultura: La competenza pragmatica interculturale. Italiano LinguaDue 7, 111–130. doi: 10.13130/2037-3597/5014

Narayanan, A., and Kapoor, S. (2024). AI snake oil: what artificial intelligence can do, what it can’t, and how to tell the difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Orsini, M., and Brunato, D. (2025). Direct and indirect interpretations of speech acts: evidence from human judgments and large language models. Eleventh Italian Conference on Computational Linguistics. Cagliari, Italy.

Padilla Cruz, M. (2013). Metapsychological Awareness of Comprehension and Epistemic Vigilance of L2 Communication in Interlanguage Pragmatic Development. Journal of Pragmatics 59, 117–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2013.09.005

Papadimitriou, I., Lopez, K., and Jurafsky, D. (2023). Multilingual BERT has an accent: evaluating English influences on fluency in multilingual models. Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Research in Computational Linguistic Typology and Multilingual NLP, 143–146.

Park, D., Lee, J., Jeong, H., Park, S., and Lee, S. (2024). Pragmatic competence evaluation of large language models for the Korea n language. arXiv.org.

Rahm, L., and Rahm-Skågeby, J. (2023). Imaginaries and problematisations: a heuristic lens in the age of artificial intelligence in education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 54, 1147–1159. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13319

Ross, J. (2023). Digital futures for learning: speculative methods and pedagogies. New York: Routledge.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: an essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Thomas, J. (1983). Cross-cultural pragmatic failure in applied linguistics. Appl. Linguist. 4, 91–112.

Thorne, S. L. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence, co-evolution, and language education. Mod. Lang. J. 108, 567–572. doi: 10.1111/modl.12932

Wendler, C., Veselovsky, V., Monea, G., and West, R. (2024). Do llamas work in English? On the latent language of multilingual transformers. 15, 15366–15394. doi: 10.18653/v1/2024.acl-long.820

Wilson, J. (2024). Pragmatics, utterance meaning, and representational gesture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yue, S., Song, S., Cheng, X., and Hu, H. (2024). Do large language models understand conversational implicature—a case study with a Chinese sitcom. DOI.org (Datacite).

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., and Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education – where are the educators? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 16:39. doi: 10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

Zhang, M., Yang, Y., Xie, R., Dhingra, B., Zhou, S., and Pei, J. (2025). Generalizability of large language model-based agents: a comprehensive survey (No. arXiv:2509.16330). arXiv. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2509.16330

Keywords: pragmatics, artificial intelligence, postdigital, educational technology, inclusion

Citation: Manna M, Eradze M and Cominetti F (2025) How inclusive large language models can be? The curious case of pragmatics. Front. Educ. 10:1619662. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1619662

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Milan Cabarkapa, University of Kragujevac, SerbiaKunihiko Takamatsu, Institute of Science Tokyo, Japan

Zeus Plasencia-Carballo, University of La Laguna, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Manna, Eradze and Cominetti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martina Manna, bWFydGluYS5tYW5uYUB1bml2YXEuaXQ=

Martina Manna

Martina Manna Maka Eradze

Maka Eradze Federica Cominetti

Federica Cominetti