- 1Program Studi Pendidikan Agama Islam (Magister), Pascasarjana, Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin Makassar, Makassar, Indonesia

- 2Program Studi Pendidikan Agama Islam, Fakultas Tarbiyah, Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin Makassar, Makassar, Indonesia

- 3Program Studi Ilmu Komunikasi, Fakultas Dakwah dan Komunikasi, Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin Makassar, Makassar, Indonesia

- 4Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris, Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan, Universitas Iqra Buru, Namlea, Maluku, Indonesia

As in many education systems worldwide, Indonesian society is increasingly characterized by cultural diversity. In the context of centralized education policies, multicultural issues have become more visible in primary schools. This study aimed to explore the attitudes and classroom practices of elementary school teachers in Indonesia regarding multicultural education. A mixed-methods approach utilizing a concurrent triangulation design was employed. Data were collected through a multicultural education attitude survey and semi-structured interviews. In the quantitative phase, a multiculturalism attitude scale was administered to 30 randomly selected primary school teachers. The survey results indicated moderately positive attitudes toward multicultural values, with minor variations based on age and teaching experience. In the qualitative phase, interviews and classroom observations were conducted with 10 teachers. The findings revealed that while teachers recognized multiculturalism mainly through ethnicity, religion, and language differences, they perceived substantial gaps between policy expectations and classroom realities. Teachers noted a lack of institutional support and limited curriculum flexibility as major barriers to implementing multicultural education. Many expressed that their understanding of multicultural pedagogy was incomplete and showed interest in participating in professional development programs to enhance their competence. The study highlights the critical need for more responsive policies and teacher training initiatives to bridge the gap between centralized standards and multicultural classroom dynamics.

Introduction

Indonesia is recognized as one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse countries in the world, comprising more than 1,300 ethnic groups and over 700 languages. This diversity is reflected daily in Indonesian primary schools, where students from different ethnic, religious, and linguistic backgrounds come together within a centralized education system (Ford, 2010). The education system serves a critical role in transmitting not only academic knowledge but also cultural values, social norms, and the principles of national unity. However, as Indonesian society becomes more interconnected and pluralistic, schools are increasingly challenged to address the complexities of diversity in both curriculum and practice (Aydin, 2013; Slamet et al., 2021).

In this context, multicultural education has emerged as a key concept and reform movement. It seeks to integrate diverse cultural perspectives into teaching, curriculum, and school culture, while promoting equity and respect for all students—regardless of background, gender, ability, or identity (Almendarez, 2013; Čulić-Viskota, 2018; Tyer-Viola and Cesario, 2010). In Indonesia, the tension between promoting national cohesion and embracing local cultural differences creates unique challenges for primary schools, especially as national education policies remain highly centralized (Ikasari, 2020; Raihani, 2018). As a practice, multicultural education involves transforming teaching, curriculum, and school culture to affirm diversity, foster inclusion, and reduce educational inequalities. As a movement, it calls for systemic change to dismantle structures that perpetuate marginalization and to promote social justice in education (Abdul-Jabbar, 2023). Multiculturalism itself is multidimensional, involving not only ethnicity and language but also class, gender, sexual identity, religion, ability, and humanity’s relationship with nature (Arifin and Hermino, 2017).

Scholars argue that multicultural education promotes social harmony and respectful coexistence (Arifin and Hermino, 2017; Ennerberg, 2022) by cultivating empathy and intergroup understanding. When education acknowledges the deep interplay between culture and schooling, it can help address persistent challenges—such as social exclusion, stereotyping, or unequal access to learning (El-Atwani, 2015; Ennerberg, 2022; Kerebungu et al., 2019). Still, even as more countries embrace multicultural education in policy, real-world implementation often lags, and privileged groups continue to benefit disproportionately while others are marginalized (Čulić-Viskota, 2018). Recent migration and global change have further intensified cultural diversity, not just in world cities but also in rural communities (Cathrin and Wikandaru, 2023).

As communities grow more heterogeneous, monocultural approaches are increasingly inadequate. Schools, as agents of cultural transmission, must adapt their practices to acknowledge and embrace multicultural realities (Kirk, 2004). Addressing the complexities of cultural diversity requires a shift toward educational models that affirm and integrate diverse identities. Countries—including Indonesia—are thus called to reform their educational systems to promote equity and respect for all learners. Indonesia’s educational context is especially compelling. With more than 1,300 ethnic groups and hundreds of languages, Indonesian public schools bring together students from diverse backgrounds. However, there are persistent tensions between ideals of unity (as articulated in Pancasila) and the lived realities of diversity.

Recent reforms, including the Kurikulum Merdeka “Independent Curriculum,” were introduced in 2022 to give teachers more freedom in designing learning activities that reflect local cultures and student diversity, moving away from rigid, centralized approaches (Cahaya et al., 2022; Mariyono, 2019). Yet, the translation of these ideals into classroom practice remains uneven, with substantial disparities between urban and rural schools and across provinces (Raihani, 2018). These regional and resource disparities, combined with historical experiences of conflict and coexistence, mean that multicultural education policy in Indonesia is always shaped by both national and local factors.

In recent years, research on multicultural education in Indonesia has predominantly focused on policy analysis, curriculum frameworks, and philosophical debates, with limited attention to the everyday experiences of teachers in diverse classrooms (Ikasari, 2020; Raihani, 2018). Studies by Ikasari (2020) and Mariyono (2019) highlight the persistence of top-down policies and the gap between national ideals and classroom realities. Some scholars have examined how teachers navigate curriculum mandates, but few have explored the attitudes, conceptualizations, and classroom strategies of primary school teachers in detail (Cathrin and Wikandaru, 2023; Walker et al., 2019). Comparative research in Southeast Asia similarly notes a lack of empirical work on teacher agency in implementing multicultural practices, especially in centralized education systems (Choi and Lee, 2020; Zilliacus et al., 2017). More recent studies in Indonesia reveal that while teachers generally support the principles of multicultural education, there are significant challenges related to limited professional development, resource constraints, and ambiguity in policy implementation (Abacioglu et al., 2022; Cahaya et al., 2022). However, few studies have systematically integrated both quantitative and qualitative perspectives to analyze teachers’ beliefs, classroom practices, and the contextual factors shaping multicultural education in Indonesian primary schools. This study seeks to address these gaps by employing a mixed-methods approach to investigate not only teachers’ attitudes and understanding, but also the practical barriers and strategies that influence the enactment of multicultural values in daily classroom life.

Despite increased policy attention, there remains a significant lack of empirical research on how primary school teachers in Indonesia interpret, negotiate, and enact multicultural values in their daily classroom practices. Most existing studies have focused on policy and curriculum analysis or offered limited insights into teachers’ lived experiences (Ikasari, 2020; Raihani, 2018; Walker et al., 2019). Few have systematically explored the barriers, practical strategies, and professional development needs of teachers working in multicultural settings, especially through a mixed-methods lens.

To address these gaps, this study aims to provide a comprehensive account of how multicultural education is perceived and implemented by Indonesian primary school teachers. Specifically, it seeks to: (1) examine teachers’ beliefs and attitudes toward multicultural education; (2) explore their conceptualization of multicultural principles; (3) identify challenges in implementing inclusive classroom practices; and (4) document teachers’ strategies and recommendations for advancing equity and diversity.

Guided by these objectives, the central research question is:

How do Indonesian primary school teachers perceive and implement multicultural education, and what challenges and strategies do they identify in fostering inclusive classroom environments?

Theoretical framework

Multicultural education has emerged as a significant movement aimed at promoting equity and social justice within educational systems. Its foundation rests on the belief that education should provide all students—regardless of their cultural, ethnic, racial, linguistic, gender, or socioeconomic backgrounds—with equal opportunities to learn and succeed (Banks and Banks, 2010). Multicultural education, in this study, is conceptualized both as a principle that values diversity and as a set of transformative practices and policies seeking systemic change in schools (Arsal, 2019). Diversity is not seen as a challenge to be managed, but as a resource that can enrich the learning experience for all students. To comprehensively analyze teachers’ approaches to multiculturalism, this study primarily draws on Banks and Banks (2010) Five Dimensions of Multicultural Education. This framework was chosen because it is internationally recognized and widely used for its comprehensive coverage of multicultural education at both policy and practice levels, encompassing content integration, knowledge construction, prejudice reduction, equity pedagogy, and empowering school culture. These dimensions allow for a nuanced analysis of teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices, and are particularly relevant for examining how educators negotiate diversity in highly heterogeneous and centralized education systems like Indonesia’s (Hastie and Wallhead, 2016; MacPhail et al., 2004). The Banks framework is also adaptable to various cultural contexts, enabling meaningful comparison with prior studies conducted in Southeast Asia and beyond (Li et al., 2020; Llevot-Calvet and Garreta-Bochaca, 2025; Meetoo, 2020).

The five dimensions—content integration, knowledge construction, prejudice reduction, equity pedagogy, and empowering school culture—provide a framework for interpreting how teachers perceive and enact multicultural education in Indonesian primary schools.

1. Content Integration refers to the extent to which teachers incorporate materials, examples, and perspectives from diverse cultures into their lessons. This dimension is especially salient in Indonesia’s highly heterogeneous context, where students’ backgrounds vary widely by region, ethnicity, and religion. Embedding cultural diversity in instructional content can validate students’ identities and foster a sense of belonging.

2. Knowledge Construction involves helping students understand how cultural assumptions and perspectives shape knowledge in all disciplines. In Indonesia, where social studies, history, and language often reflect dominant narratives, this dimension encourages critical thinking and invites students to question how knowledge is produced and whose voices are represented.

3. Prejudice Reduction focuses on fostering positive relationships and reducing bias among students from different backgrounds. Teachers’ beliefs and daily interactions play a crucial role in either reinforcing stereotypes or promoting empathy and cross-cultural respect—especially critical in Indonesia’s multicultural but sometimes polarized environment.

4. Equity Pedagogy highlights the importance of adapting instructional methods to meet the learning needs of students from various backgrounds. Moving beyond mere acknowledgment of diversity, teachers are called to implement pedagogies that address disparities in achievement linked to regional, socioeconomic, or cultural factors.

5. Empowering School Culture and Social Structure requires schools to examine and restructure institutional norms, policies, and practices that may marginalize certain groups. In Indonesia, where educational administration is often highly centralized yet locally implemented, this dimension speaks to both school-wide leadership and the collective responsibility for creating inclusive cultures.

To enrich the analysis, this study also references (Sleeter and Grant, 2007) typology of multicultural education approaches, which range from teaching the “exceptional and culturally different” to promoting “social reconstructionist” and “multicultural and social justice” perspectives. This typology is useful for mapping the range of teacher beliefs and practices encountered in the field. In addition, Gay (2023) concept of “culturally responsive teaching” is included as a complementary framework, emphasizing the need for educators to leverage students’ cultural backgrounds as assets in the learning process.

The operationalization of these frameworks is reflected throughout this study: (1)The survey and interview instruments were designed to probe each of Banks’ five dimensions, as well as elements of culturally responsive teaching (see Appendix for sample items); (2) Interview questions explored how teachers integrate cultural content, address bias, adapt pedagogy, and interpret institutional support or barriers; (3) During data analysis, findings were coded and organized using these theoretical lenses, allowing for systematic interpretation of both quantitative trends and qualitative themes.

Recent Indonesian research (Idris et al., 2022; Walker et al., 2019; Yusriadi and Hamim, 2022) demonstrates the relevance of these frameworks in understanding the interplay between policy, teacher beliefs, and classroom realities. At the same time, uniquely local challenges—such as the negotiation of Pancasila, decentralized curriculum reforms, and local histories of conflict or harmony—shape how multicultural education is interpreted and implemented. By situating teacher attitudes within these intersecting frameworks, this study goes beyond individual perceptions to illuminate broader systemic factors that enable or constrain multicultural practice. Understanding teachers’ engagement with each dimension offers insights into professional development priorities and the institutional changes required to advance equity and inclusion in Indonesian primary schools.

Methods

Research design

A mixed-methods approach was adopted to provide a comprehensive understanding of primary school teachers’ attitudes and practices regarding multicultural education in Indonesia. Mixed methods, as defined by Kelle (2022), integrate quantitative and qualitative techniques to capture both numerical trends and nuanced contextual insights (Tashakkori and Creswell, 2008). This approach was chosen because neither quantitative nor qualitative methods alone could fully reflect the multifaceted nature of teachers’ beliefs and classroom realities in a highly diverse national context. The study utilized a concurrent triangulation strategy, where quantitative and qualitative data were collected in parallel, analyzed independently, and integrated during interpretation (Creswell, 1999; Fetters et al., 2013). This allowed for validation through convergence and for deeper explanation when results diverged.

Sampling and participants

The study population comprised teachers from 18 Indonesian public primary schools, purposefully selected to capture broad regional and demographic variation. Schools were chosen using purposive sampling based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) being a public (state) primary school; (2) representing one of five major regions of Indonesia (Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Kalimantan, Bali–Nusa Tenggara); (3) encompassing both urban and rural locations; and (4) serving students from diverse ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. From a preliminary list of eligible schools—identified via regional education offices and directories—18 were selected to ensure balanced representation. Schools not meeting these criteria (such as private schools or those in homogenous/remote areas) were excluded.

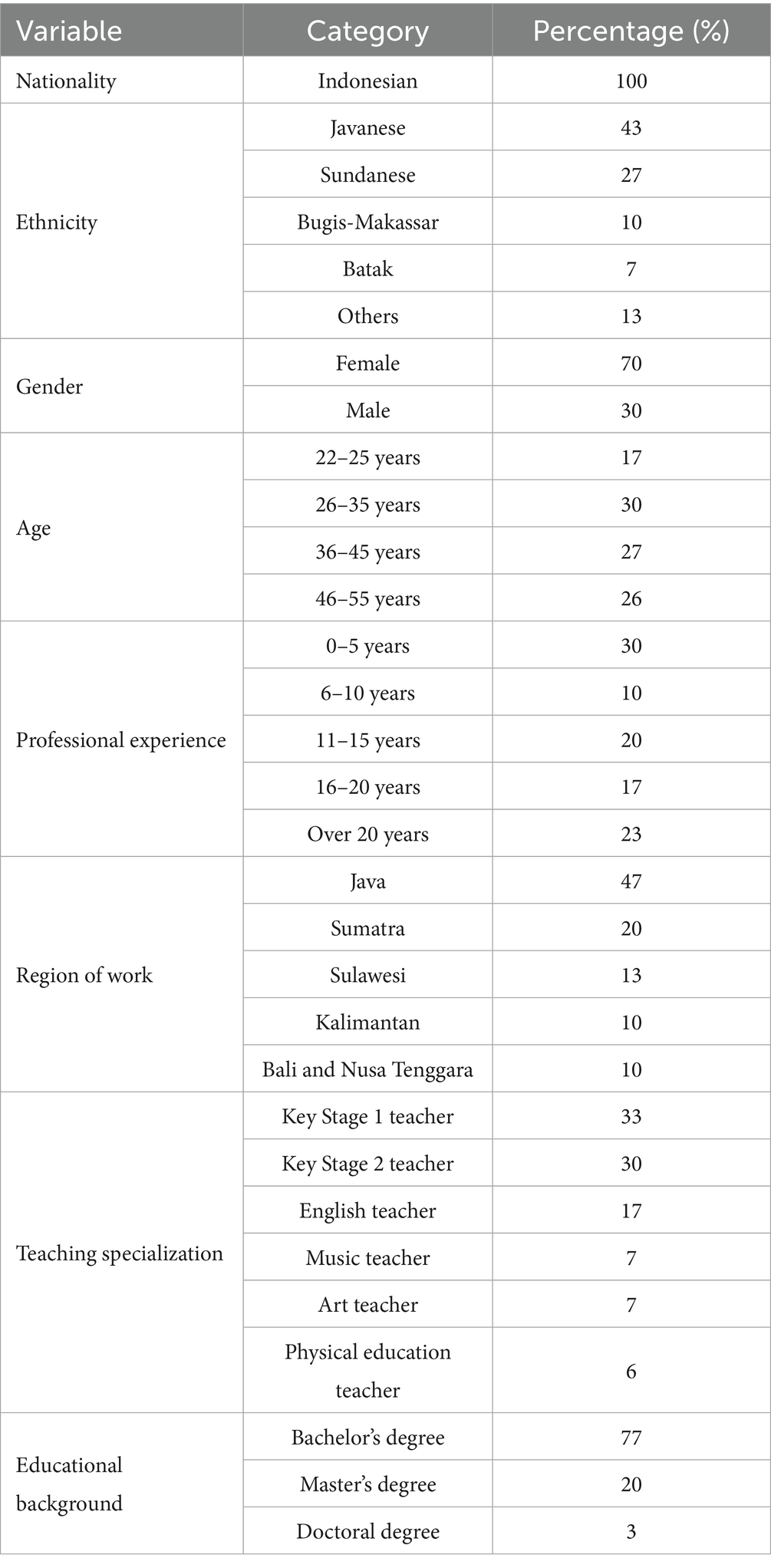

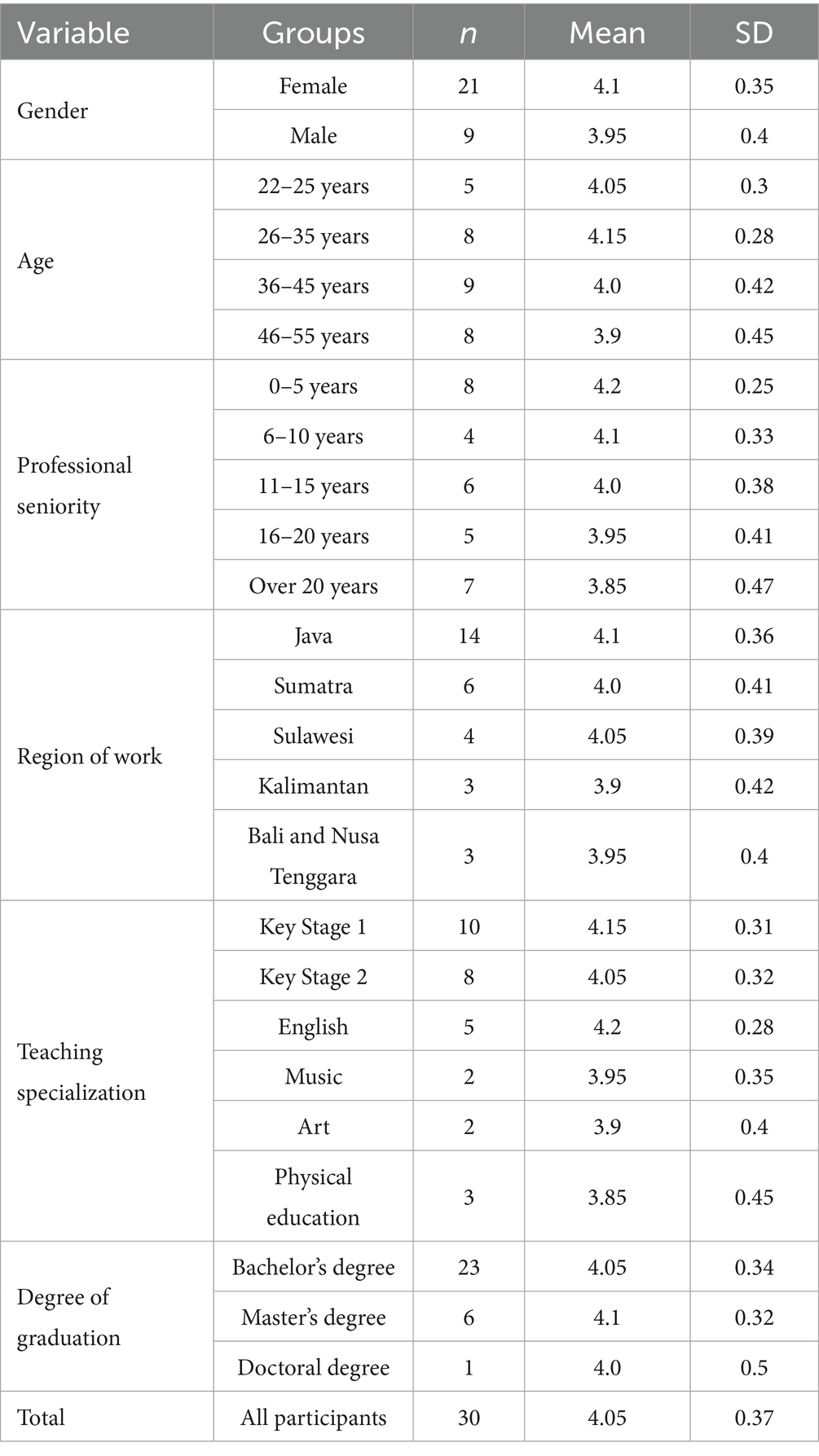

Within each selected school, teacher participants were recruited using random sampling when possible (i.e., when a complete roster and administrative approval were available). Where this was not feasible, volunteer-based recruitment was applied. This mixed approach maximized participation and diversity of perspectives, accounting for practical constraints in different regions. One or two teachers were selected from each school, resulting in a final sample of 30 teachers. The overall response rate was approximately 70% from those initially invited. Of the 30 respondents, 70% were female and 30% male. Age ranged from 22 to 55, professional experience from 0 to over 20 years, and educational attainment spanned from Bachelor’s to Doctoral degrees. Teachers represented a wide array of ethnic groups (Javanese, Sundanese, Bugis-Makassar, Batak, and others) and teaching specializations (see Table 1 for full demographic breakdown).

Quantitative data collection

Quantitative data were gathered using the Teacher Multicultural Education Survey (TMES), translated and linguistically validated for the Indonesian context. Reliability analysis in this study yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75. The TMES consists of 18 items on a 5-point Likert scale, measuring teachers’ attitudes toward multicultural education, plus a demographic information form. Surveys were distributed in digital format (email/WhatsApp) and, in several rural schools, as paper questionnaires. All responses were anonymized, and participation was voluntary. Data were entered into SPSS for analysis.

Qualitative data collection

The qualitative phase employed a case study approach (Creswell, 1999). From the original quantitative sample, 10 teachers were purposively selected to maximize variation in region, gender, age, and teaching experience. Data were collected primarily through semi-structured interviews, which were conducted either online or face-to-face as permitted, with each session lasting approximately 30 min. The interview protocol was carefully developed based on the research questions and an extensive review of relevant literature (Cherng and Davis, 2017; Nieto, 2017), and subsequently reviewed by two academic experts before being revised for clarity. Participants were invited to respond to open-ended questions such as, “How do you define multicultural education in your own words?,” “Can you describe experiences or challenges you have faced when teaching students from diverse backgrounds?,” and “What strategies do you use to promote inclusion and respect for diversity in your classroom?” (see Supplementary File for the complete protocol). All interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ consent, then transcribed and anonymized to ensure confidentiality. Where possible, the research team also documented non-verbal cues and contextual details to enrich the qualitative data.

Data analysis

For the quantitative data, descriptive statistics were used to summarize teachers’ attitudes toward multicultural education across various demographic variables. The normality of the data was assessed through skewness and kurtosis values. Since the data did not meet the assumptions of normal distribution, nonparametric tests—specifically, the Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis H test—were employed to examine group differences.

The qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis, as outlined by Aspers and Corte (2019). Interview transcripts were coded thematically, with the analytical framework guided by Banks’ five dimensions of multicultural education and supplemented by open coding to capture emergent themes. To ensure the trustworthiness of the findings, a member checking process was conducted in which all 10 interview participants were asked to review and confirm the accuracy of the results (Reeves et al., 2008). Additionally, peer debriefing sessions were held among members of the research team to further enhance the credibility of the analysis.

To minimize social desirability bias, all participants were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and were informed that their responses would not affect their professional standing. During data collection, researchers emphasized the importance of honest answers and clarified that there were no right or wrong responses. Open-ended questions were also employed to encourage candid and reflective statements.

Mixed-methods integration

In this study, the results from both the quantitative and qualitative phases were systematically integrated to generate a holistic and nuanced understanding of teachers’ attitudes and practices related to multicultural education. Integration occurred primarily during the discussion phase, where quantitative findings—such as patterns and differences in attitudes across demographic variables—were compared with qualitative insights drawn from teachers’ narratives and classroom experiences. This process allowed the researchers to identify areas where data from both methods converged, confirming the robustness of certain findings, as well as areas where they diverged, thus highlighting complexity or unexpected dynamics in the field (Fetters et al., 2013). By employing a concurrent triangulation design, each method not only complemented but also informed the interpretation of the other. For example, quantitative results that indicated generally positive attitudes toward multicultural education were further explained by qualitative evidence revealing persistent misconceptions and practical challenges faced by teachers. Similarly, regional differences observed in the survey data were contextualized and deepened by teachers’ qualitative accounts of local realities and institutional barriers. Through this integrative approach, the study was able to provide richer, more credible, and contextually grounded conclusions. The use of mixed-methods triangulation ultimately strengthened the validity of the findings, reduced the risk of single-method bias, and enabled a more comprehensive exploration of multicultural education in the Indonesian primary school context.

Limitations and ethical considerations

Despite efforts to represent Indonesia’s diversity by sampling from multiple regions and school contexts, the relatively small sample size and the selection of participating schools mean that the findings may not be fully generalizable to all regions, particularly those that are remote or underrepresented. Additionally, the voluntary nature of participation and reliance on self-report measures introduce the possibility of response bias, as teachers who are more open to discussing multicultural education may have been more likely to participate, and social desirability could have influenced responses. In addressing ethical considerations, all data were anonymized to protect participant confidentiality. Participation was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to data collection. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin to ensure compliance with established research standards.

Results

RQ1: demographic variation in teachers’ attitudes toward multicultural education (quantitative findings)

To address Research Question 1, this section presents the demographic variation in primary school teachers’ attitudes toward multicultural education, drawing from survey data across gender, age, professional seniority, region of employment, teaching specialization, and educational attainment. As shown in Table 2, the sample of 30 teachers achieved an average multicultural education attitude score of 61.47 out of 90 (M = 4.05, SD = 0.37), indicating a generally positive orientation toward multicultural education. The attitude scores were above the scale midpoint, suggesting that most teachers held favorable views on cultural diversity in educational settings (Wezel and Soldat, 2009). Descriptive statistics for each demographic variable are summarized below.

Table 2. Mean, standard deviation, and number of participants based on demographic variables in multicultural education attitude scores.

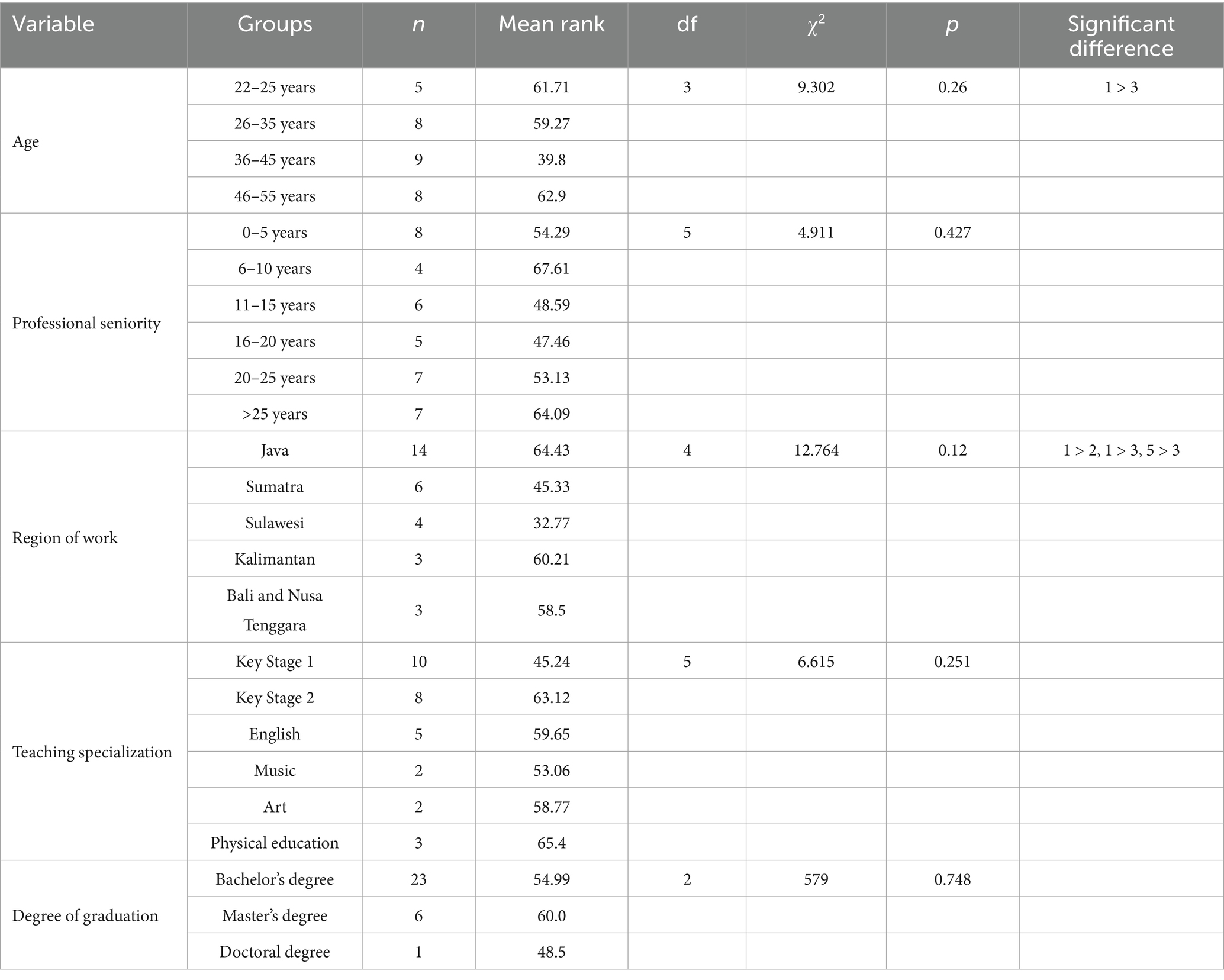

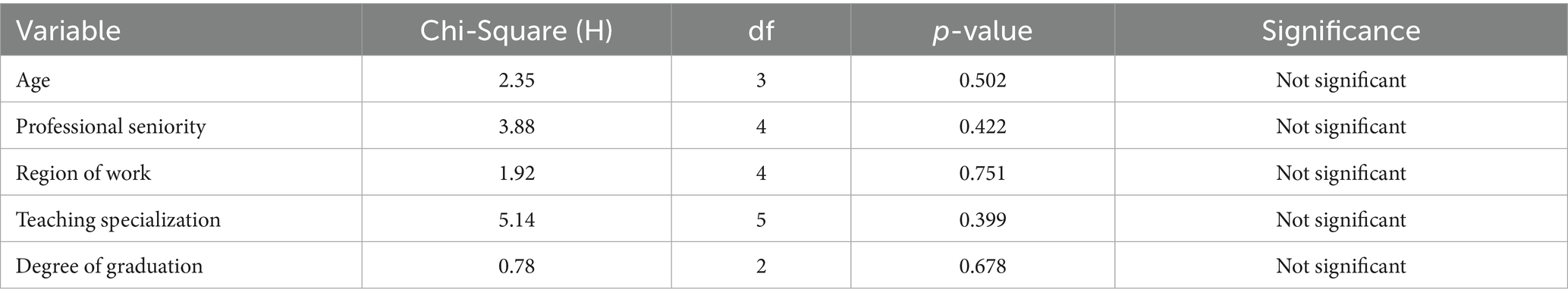

Tests for normality (Skewness/Kurtosis) indicated the data were not normally distributed (Wezel and Soldat, 2009), so nonparametric tests were used. The Mann–Whitney U test showed no significant difference by gender (U = 85.5, p = 0.42, r = 0.10), and the Kruskal–Wallis test found no significant differences by professional seniority, teaching specialization, or educational attainment (all p > 0.40). These results suggest that positive attitudes are widespread across most demographic backgrounds, reflecting a basic level of multicultural acceptance among teachers. However, statistically significant and practically meaningful differences were observed in relation to age and region (see Table 3). Teachers in Java reported significantly higher attitude scores than those in Sumatra (p = 0.02, η2 = 0.18), reflecting a moderate effect size, while teachers in Bali–Nusa Tenggara also scored higher than those in Sulawesi (p = 0.04, η2 = 0.15). Similarly, younger teachers (22–25 and 26–35 years) exhibited more positive attitudes compared to the 36–45 age group (p = 0.03, η2 = 0.14) (Table 4).

Table 4. Kruskal–Wallis test results of multicultural education attitude scores based on demographic variables.

The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed to examine whether teachers’ attitudes toward multicultural education differed significantly across various demographic variables. When significant differences were identified through the Kruskal–Wallis test, follow-up pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test to determine the specific groups contributing to the observed differences. The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 3.

Follow-up pairwise comparisons using the Mann–Whitney U test confirmed that teachers in Java had significantly higher attitudes than those in Sumatra and Sulawesi, and that teachers in Bali and Nusa Tenggara outperformed those in Sulawesi. Teachers aged 22–25, 26–35, and 46–55 years showed significantly higher attitudes compared to the 36–45 group. These findings highlight that regional educational environments and generational perspectives play a role in shaping attitudes, possibly reflecting variations in exposure to diversity and institutional support. The observed regional disparities suggest uneven development of an Empowering School Culture (Banks and Banks, 2010, Dimension 5), while the overall positive attitudes across demographics indicate foundational acceptance of Content Integration (Dimension 1), although depth and consistency likely vary across regions and age groups.

In summary, while the average attitude toward multicultural education among Indonesian primary school teachers is positive and broadly distributed across most demographic categories, this positivity is not uniform. Regional disparities are particularly notable: teachers in Java and Bali–Nusa Tenggara demonstrate significantly more progressive attitudes than those in Sumatra and Sulawesi, with moderate effect sizes indicating practical significance beyond mere statistical significance. This finding suggests that regional policy implementation, resource allocation, or exposure to cultural diversity may be influencing teachers’ perspectives. Age differences were also evident, with younger and some older teachers (22–25, 26–35, and 46–55 years) expressing more favorable attitudes than those in the 36–45 age group. This generational variation could be related to differences in teacher training curricula, professional development opportunities, or openness to pedagogical innovation. It may also reflect broader socio-cultural shifts occurring in Indonesia as younger teachers enter the workforce with more recent exposure to multicultural discourses, while mid-career teachers may be more deeply embedded in established teaching routines.

Notably, the lack of significant variation by gender, professional seniority, teaching specialization, or educational attainment indicates that acceptance of multicultural education is not confined to any one subgroup, but rather is diffused throughout the teaching population—albeit with substantial variability in intensity and practical engagement. When mapped onto Banks’ Five Dimensions of Multicultural Education, these findings suggest that, at least in terms of attitudes, foundational elements of Content Integration (Dimension 1) are present among most teachers. However, the regional disparities point to challenges in achieving an Empowering School Culture (Dimension 5) that is consistent nationwide. These quantitative results set the stage for deeper qualitative exploration into how teachers actually understand and implement multicultural education—issues further addressed in RQ2 and RQ3.

While the overall quantitative profile reflects a generally positive orientation toward multicultural education, the qualitative findings below reveal persistent conceptual and practical gaps, as well as regional and generational differences in how multiculturalism is understood and enacted in Indonesian primary schools. These demographic trends highlight not only the structural and contextual influences shaping teachers’ attitudes, but also underscore the necessity for targeted policy interventions and professional development—especially in regions and generational cohorts where acceptance of multicultural education is less robust.

RQ2: teachers’ understanding of multicultural education (qualitative findings)

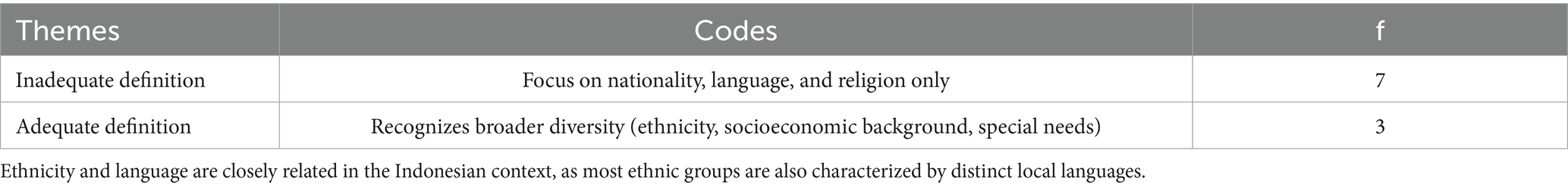

This section presents findings related to Research Question 2: “What are the views of primary school teachers regarding their understanding of multicultural education?” The analysis draws on semi-structured interviews with 10 primary school teachers representing diverse regions and backgrounds. As summarized in Table 5, most teachers’ conceptualizations of multicultural education remain narrow, focusing primarily on nationality, language, and religion, with only a minority articulating broader, more inclusive understandings.

The predominance of limited definitions is evident in teacher reflections. For example:

“For me, multicultural education is mainly about teaching students to appreciate the differences in religion and language that exist among us. In my class, I try to introduce students to various local languages and customs, but sometimes I still feel that my understanding is limited to what I have experienced personally. I realize that multiculturalism is a broader concept, but in practice, I often focus on what is most visible—like religious holidays and language diversity.” (Teacher 1, female, 28 years old)

Such responses reveal a conceptual focus on visible markers of difference, consistent with Banks’ Content Integration dimension—the tendency to incorporate easily identified cultural elements, such as language or religious practice, into teaching. However, the underlying complexity of multicultural education is often overlooked. Only three teachers explicitly articulated broader and more inclusive perspectives:

“Multicultural education is not only about religion or language, but also about accepting students with special needs and different economic backgrounds. I try to see each child as an individual with their own uniqueness, even though the challenges are not easy.” (Teacher 6, male, 45 years old)

This more comprehensive definition resonates with both Content Integration and Knowledge Construction dimensions of Banks’ model, as it recognizes that diversity extends beyond surface features to include socioeconomic background, special needs, and individual uniqueness. Yet, these inclusive views are not common among the sample, suggesting that most teachers are not yet engaging with the deeper, critical aspects of multicultural education. Teachers also acknowledged the absence of a systematic multicultural framework in Indonesian primary education. Most noted that even their limited interpretations are rarely embedded in classroom practice, often due to a lack of guidance or support from school leadership and policy:

“To be honest, I have never received any formal training specifically about multicultural education. All I know is from my own experience and observations, or sometimes from discussions with other teachers. I feel that the school expects us to handle diverse classrooms, but we are not really equipped with the right strategies. If there was a workshop or training about how to manage cultural differences or address potential conflicts, I would join for sure.” (Teacher 4, female, 35 years old)

These gaps point to the need for capacity building not only in teachers’ attitudes, but also in their conceptual frameworks and practical strategies—again echoing the Knowledge Construction and Equity Pedagogy dimensions of multicultural education theory.

Challenges reported by teachers centered on linguistic and cultural barriers, with communication difficulties being the most frequently cited problem. These obstacles complicate efforts to foster inclusive classroom environments and highlight the limited institutional support for implementing multicultural principles:

“One of the biggest challenges I face is when students come from families that speak a different language at home. For example, I had a student who had just moved from another island and struggled to communicate with both peers and teachers. He often looked confused during lessons and would sometimes withdraw from group activities. I wanted to help, but with so many students in one class and no specific resources or support, it was difficult.” (Teacher 2, male, 34 years old)

While Bahasa Indonesia serves as the national language and medium of instruction in all public schools, teachers noted that some students—especially those who recently moved from different regions or who speak a local language at home—struggle initially to communicate fluently with peers and teachers. This language barrier is particularly evident in early primary grades and among children whose exposure to Indonesian has been limited outside school settings. Such transitional challenges can lead to difficulties in participation and social integration, despite the use of a common national language.

Further, teachers described a range of issues including student difficulties in adapting to school culture, the formation of exclusive peer groups among newcomers, misunderstandings, and marginalization—problems exacerbated by inadequate training and institutional resources. The findings thus reveal that the majority of teachers’ conceptualizations of multicultural education are shaped by their direct experiences and limited professional development opportunities, rather than a broader engagement with the literature or critical reflection on systemic inequities. As a result, teachers tend to address only the most visible forms of diversity, while underlying issues—such as power dynamics, social class, or learning differences—are frequently overlooked.

These patterns indicate that while teachers are engaged at the level of Content Integration, their understanding rarely advances toward Knowledge Construction or the more transformative dimensions of multicultural education, as conceptualized by Banks and Banks (2010). The absence of formal training and a reliance on personal experience highlight the urgent need for structured professional development and policy support if Indonesian primary education is to move beyond superficial multicultural practices toward deeper, equity-focused transformation. Without targeted policy interventions and ongoing training, most teachers remain locked at the level of surface diversity, rarely advancing to a critical or transformative engagement with multicultural education as envisioned in international models (Banks and Banks, 2010; Nieto, 2017).

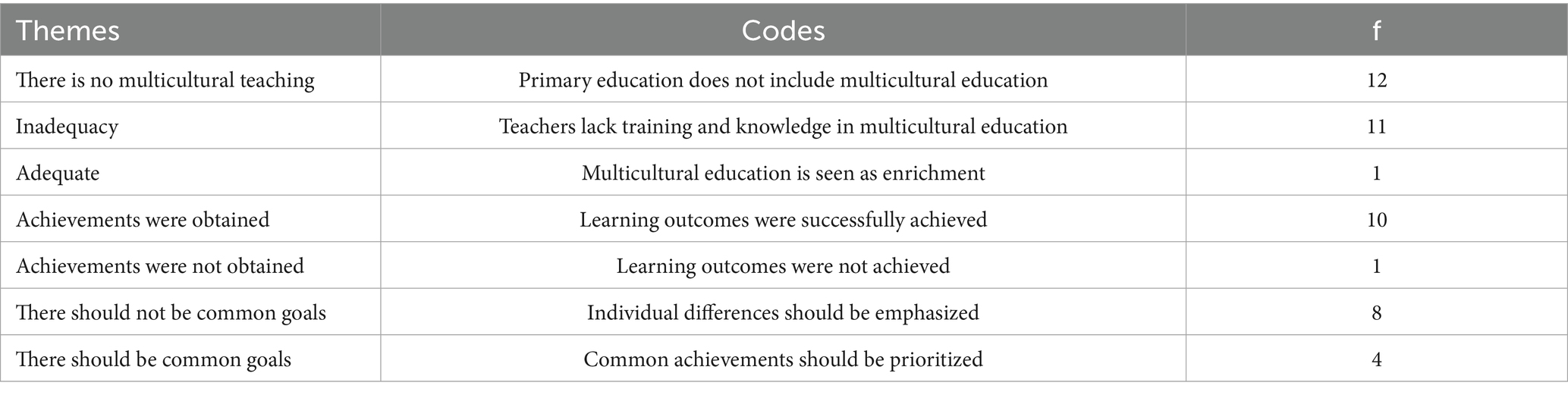

RQ3: current practices and challenges in multicultural education (qualitative findings)

This section addresses Research Question 3: “What are the views of primary school teachers regarding the extent to which primary education in Indonesia addresses multicultural structures?” The qualitative data, obtained from in-depth interviews with 10 primary school teachers, reveal critical gaps between theory and practice as well as persistent barriers to the effective implementation of multicultural education.

Classroom practices and multicultural dimensions

As summarized in Table 6, none of the teachers reported fully integrating multicultural education into their everyday classroom practices. About half (n = 5) described introducing cultural features—such as local languages, food, or religious holidays—as a form of multicultural education, while only three teachers discussed incorporating values like tolerance, empathy, or respect for diversity in a more systematic way. A few (n = 2) offered examples of translating lessons to help immigrant students understand the material, indicating limited but present attempts at differentiation and support.

“In my opinion, schools should provide Indonesian language classes specifically for students who come from other regions or who speak different languages at home. Right now, these children are expected to adapt on their own, which can be very stressful and discouraging. If there were special programs or even a support group for these students, I believe they would feel more welcome and could integrate better with their classmates.” (Teacher 8, female, 27 years old)

Such remarks highlight teachers’ aspirations for more systematic and institutionalized approaches to multicultural inclusion—aligning partly with Banks’ dimension of Equity Pedagogy (adapting instruction to diverse needs) and Empowering School Culture (Dimension 5, advocating for school-level changes to promote equity).

Perceived preparedness and institutional support

Nearly all teachers (n = 9) perceived themselves as inadequately prepared to implement multicultural education, attributing their struggles to a lack of training, practical guidance, and institutional support:

“We are often expected to deal with students from different backgrounds, but there is little guidance on how to actually do this. Most of what we try in the classroom is based on our own intuition or informal discussions with colleagues.” (Teacher 3, male, 41 years old)

This widespread sense of unpreparedness illustrates a shortfall in Empowering School Culture and Social Structure (Banks’ Dimension 5), where school systems and policies are not yet providing the necessary resources or professional development for teachers to succeed in diverse classrooms. Most participants (n = 8) indicated strong willingness to join in-service multicultural education training, underlining the demand for ongoing capacity-building.

Learning outcomes, individual differences, and contradictions

Another key theme concerns the contradiction between teachers’ stated beliefs in the value of differentiation and their adherence to uniform outcome expectations. While more than half of the teachers (n = 8) argued for recognizing individual differences—reflecting an emergent awareness of multicultural education’s core principles—a minority (n = 4) still supported the idea of common learning outcomes for all, consistent with traditional monocultural approaches:

“I believe every child is unique, and we should consider their backgrounds and abilities. But sometimes, we still have to follow the same targets for all students because that’s how the system is designed.” (Teacher 7, female, 36 years old)

This tension reveals the complex pressures faced by teachers, caught between curriculum centralization and their own emerging commitment to diversity. It suggests that systemic factors, such as centralized curriculum mandates and a lack of differentiated assessment, may inhibit the practical realization of multicultural education (see also Sleeter and Grant, 2007; Banks and Banks, 2010). Collectively, these qualitative findings show that while some foundational aspects of multicultural education—such as content integration and emerging awareness of equity—are present, substantive implementation remains limited by institutional and policy constraints. This gap between policy aspirations and classroom realities is further explored in the discussion that follows, using Banks’ framework as an interpretive lens.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore primary school teachers’ attitudes, understandings, and practices regarding multicultural education in Indonesia through a mixed-methods approach. By integrating quantitative and qualitative findings, this research provides a comprehensive perspective on the realities and challenges of multicultural education within Indonesian primary schools. As multicultural education gains global attention due to migration, globalization, and social change (Arsal, 2019), understanding how teachers perceive and implement multicultural principles is crucial for developing inclusive and equitable learning environments. The results of this study suggest that although Indonesian primary school teachers generally hold positive attitudes toward multicultural education, significant misconceptions persist and the practical integration of multicultural principles remains limited.

Findings and interpretations related to RQ1: demographic variation in attitudes (Banks’ Dimension 1 and 5)

Quantitative analysis revealed that Indonesian primary school teachers displayed moderately positive attitudes toward multicultural education—attitudes that were generally distributed across demographic groups such as gender, professional seniority, subject specialization, and educational attainment. This pattern indicates a foundational acceptance of diversity, aligning with Banks’ Content Integration (Dimension 1), where basic recognition of multicultural content is present (Benediktsson, 2022; Liu, 2022; Poulter et al., 2016; Zilliacus et al., 2017). However, the data also revealed significant differences related to age and region: teachers in Java and Bali–Nusa Tenggara—which are widely regarded as Indonesia’s most socio-culturally diverse and urbanized regions—demonstrated significantly more positive attitudes than their counterparts in Sumatra, Sulawesi, and the mid-career age bracket. These findings suggest that institutional support and exposure to diversity are more robust in Java and Bali–Nusa Tenggara, likely due to higher levels of interethnic interaction, better access to professional development, and stronger traditions of religious and cultural pluralism (Banks and Banks, 2010; Cahaya et al., 2022; Fruja Amthor and Roxas, 2016). The observed generational effect is particularly notable: both younger and some late-career teachers exhibited greater openness to multicultural education compared to mid-career teachers. This generational variation may reflect Indonesia’s unique post-1998 reforms, which emphasized decentralization and local cultural identity in education, thereby fostering a new discourse of diversity for younger cohorts, while some older teachers have adapted through long experience and professional exposure. In contrast, studies in other centralized systems, such as South Korea, found no significant age differences among teachers’ attitudes Choi and Lee (2020), highlighting how Indonesia’s historical, policy, and demographic shifts have shaped attitudes toward multiculturalism in distinctive ways. These patterns underscore the importance of considering both regional and generational dynamics in designing effective teacher professional development and policy interventions.

Findings and interpretations related to RQ2: teachers’ understanding of multicultural education (Banks’ Dimension 1, 2, 4)

Qualitative data revealed persistent misconceptions and a narrow conceptualization of multicultural education among most teachers. The predominance of language and religion as markers of diversity reflects a strong but limited focus on Content Integration (Dimension 1), with teachers primarily recognizing surface-level diversity (Tualaulelei and Halse, 2024). Only a minority of teachers articulated broader definitions encompassing ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and special needs, which align with Knowledge Construction (Dimension 2) and the beginnings of Equity Pedagogy (Dimension 4). For example, a few teachers mentioned the presence of students from low-income families who lacked proper uniforms or could not afford textbooks, resulting in limited participation in certain activities—a situation often observed in Indonesian public schools (Abacioglu et al., 2022). Others described cases where children of seasonal migrant workers had irregular attendance or struggled to keep up academically due to frequent moves. However, these broader acknowledgments were relatively rare, as most teachers still focused on more visible aspects of diversity, such as language and religion. Teachers’ lack of systematic understanding and the absence of formal training further limit progress toward deeper engagement with multicultural education. This reveals a gap not only in conceptual depth but also in the institutional scaffolding required to advance knowledge construction and equity-oriented pedagogy.

Findings and interpretations related to RQ3: current practices and challenges (Banks’ Dimension 4 and 5)

Despite generally positive attitudes, actual classroom practices remain limited and ad hoc. Most teachers’ multicultural initiatives involve the celebration of visible cultural differences (e.g., holidays, language), but rarely include systematic curricular reform or sustained strategies for inclusive instruction. This pattern signifies a gap in Equity Pedagogy (Dimension 4)—with most instruction adhering to uniform outcomes and limited differentiation, even when teachers recognize individual differences. Isolated efforts to help immigrant students or address language barriers are not yet supported by whole-school or system-level change, highlighting deficiencies in Empowering School Culture (Dimension 5) (Banks and Banks, 2010; Young, 2020). A key contradiction emerged between teachers’ espoused support for individual differences and their adherence to uniform learning outcomes. This tension reflects the systemic realities of Indonesia’s educational policy, particularly the “Kurikulum Merdeka” and ongoing “impactful learning” initiatives, which seek to balance diversity with standardized assessment benchmarks (Mills and Gay, 2019). As a result, teachers often find themselves in a “double bind”—aspiring to multicultural ideals while constrained by the demands of centralized curricula and high-stakes testing.

Comparison with international and local literature

These findings echo trends observed in both international and local studies, which consistently show a gap between teachers’ generally positive attitudes toward multicultural education and the limited practical realization of such principles in the classroom (Maama, 2021; Young, 2020; Zilliacus et al., 2017). For instance, in Finland and Australia, researchers have found that teachers frequently express support for diversity, yet struggle to translate these attitudes into differentiated instruction or meaningful curricular reform, often due to limited training or institutional support.

However, the Indonesian case presents several distinctive features. Most notably, the generational differences found in this study contrast with research in South Korea (Choi and Lee, 2020), where teachers’ attitudes toward multiculturalism were relatively uniform across age groups. In Indonesia, younger teachers (aged 22–35, entering the profession after 2010) and late-career teachers (aged 46–55, typically with teaching careers starting before 2000) demonstrated more positive orientations than those in the mid-career bracket (aged 36–45, generally beginning their careers between 2000 and 2010). This divergence may be attributed to Indonesia’s unique historical trajectory—specifically, the decentralization reforms initiated after 1998, the introduction of the 2006 School-Based Curriculum (KTSP), and the subsequent emergence of local content requirements and heightened discourse on regional diversity within teacher education. These policy shifts exposed newer cohorts of teachers, and those nearing retirement who have experienced both centralized and decentralized systems, to different conceptions of diversity, compared to mid-career teachers who were primarily socialized under the highly centralized, standardized regimes of the late New Order and early reform era. Another important contrast with the international literature is the role of ideology and policy in shaping multicultural education. In Indonesia, the foundational philosophy of Pancasila—“unity in diversity”—serves as both an inspiration and a constraint. On one hand, it provides a strong rationale for pluralistic approaches in education. On the other, it underpins persistent pressures toward national cohesion and standardized assessment, which can temper the practical realization of multicultural ideals. This duality is indeed a common situation when nationalism and multiculturalism (or localism) intersect, especially in countries with centralized curricular control and strong nation-building imperatives.

Furthermore, in the Indonesian context, the push for “impactful learning” and the introduction of the Kurikulum Merdeka highlight an ongoing struggle to balance local autonomy with national standards. While these reforms are intended to empower teachers and foster more context-responsive pedagogy, implementation has often lagged behind rhetoric—mirroring patterns observed in other countries but with distinct Indonesian nuances. For example, the challenge of integrating local wisdom into multicultural curricula is especially salient in Indonesia’s archipelagic setting, where cultural and linguistic diversity are far more pronounced than in many other national education systems. In summary, while Indonesian findings reflect a global pattern of attitudinal acceptance but limited classroom transformation, the drivers and constraints are contextually unique. Factors such as decentralization, the enduring legacy of Pancasila, and the evolving national curriculum interact to produce a distinct set of opportunities and challenges for multicultural education in Indonesia—requiring policy and practice solutions that are sensitive to both international lessons and local realities.

Pancasila and Indonesia’s ideological context

These systemic contradictions directly reflect Indonesia’s foundational philosophy, Pancasila, which upholds the principle of “unity in diversity” (Bhinneka Tunggal Ika) as a national ideal. In practice, however, this ideal is continually tested within the education sector, where teachers and policymakers must navigate the tension between embracing pluralism and preserving national cohesion. The results of this study reveal how these dynamics play out in daily school life: while teachers express goodwill toward diversity and aspire to inclusive classrooms, the simultaneous pressure to deliver standardized, uniform outcomes—grounded in national policy—often leads to compromises or superficial approaches. This “double bind” is further compounded by the ambiguous operationalization of multicultural education in policy. The Kurikulum Merdeka and recent “impactful learning” initiatives explicitly encourage recognition of local cultures and student differences, yet also maintain a strong emphasis on unity, common benchmarks, and centralized assessment. For many teachers, this creates uncertainty about how far they can adapt content, pedagogy, and assessment to local realities without running afoul of policy mandates.

Consequently, there is a pressing need to develop context-driven and locally relevant interpretations of multicultural education that align with both Indonesian realities and the philosophical commitments of Pancasila. Such an approach would not only address existing conceptual and practical gaps but also empower schools and teachers to move beyond tokenistic or fragmented inclusion efforts. Ultimately, grounding multicultural education in the values and lived experiences of Indonesian communities will be essential to realizing the transformative potential of Pancasila’s vision—honoring diversity without sacrificing unity.

Policy recommendations

Based on these findings, actionable recommendations include: (a) teacher training programs should go beyond attitudinal change and focus on advancing Knowledge Construction (Dimension 2) and Equity Pedagogy (Dimension 4), for example by using case studies and lesson plans from more diverse regions (Java, Bali) as models; (b) curricular reforms should allow for greater assessment flexibility and promote project-based learning to support differentiated instruction; (c) school leaders and policymakers should prioritize the provision of language support for internal migrant or immigrant students—who may struggle with communication and adaptation due to differences in home language and prior schooling—as well as structured parental engagement and the integration of local wisdom, all of which foster an Empowering School Culture (Dimension 5); (d) policy dialogue should explicitly address the tensions between pluralism and unity, encouraging regional adaptations of multicultural education that are grounded in community context.

Limitations and generalizability

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study’s reliance on self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias, with teachers potentially overstating positive attitudes or practices. Second, the sample was drawn primarily from Java and other urbanized areas, which may not fully represent the diversity of challenges faced in rural or eastern regions such as Papua or Maluku. Third, the relatively small sample (30 teachers from 18 schools) limits generalizability. Future research should include larger, more geographically diverse samples and incorporate classroom observations, student perspectives, and policy analysis to capture a more nuanced picture of multicultural education in Indonesia.

Closing the loop: bridging attitudes, understanding, and practice

In summary, bridging the gap between positive teacher attitudes, deeper conceptual understanding, and practical classroom enactment will require both systemic and structural support—especially through professional development, curriculum flexibility, and supportive school leadership. Only with these conditions in place can Indonesia realize the transformative potential of multicultural education, fostering both pluralism and unity as envisioned in Pancasila.

Conclusion

This study shows that Indonesian primary school teachers generally hold positive attitudes toward multicultural education, but their understanding and classroom practices remain limited—especially to superficial aspects like language and religion. When mapped to Banks’ Five Dimensions, most teachers achieve only partial Content Integration, rarely advancing to Knowledge Construction, Equity Pedagogy, or the creation of an Empowering School Culture. These gaps are especially pronounced in less urban regions and among mid-career teachers. Policy reform is urgently needed. Teacher training and curriculum development should move beyond attitude-building to specifically target deeper dimensions—such as critical knowledge construction and equity pedagogy—using practical, locally relevant models. Schools must foster whole-community engagement, involving students and parents not only as research participants but as partners in designing and sustaining inclusive practices.

This study’s limitations include a sample skewed toward Java, self-report bias, and underrepresentation of rural or eastern provinces. Broader, multi-stakeholder research is needed. Ultimately, bridging the gap between positive attitudes and effective, equity-driven practice requires coordinated action from teachers, policymakers, school leaders, students, and families. Realizing the transformative potential of multicultural education in Indonesia means enacting Banks’ framework holistically—grounded in the context and values of Pancasila, and driven by a collective vision for impactful learning for all.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Committee of Research Alauddin University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abacioglu, C. S., Fischer, A. H., and Volman, M. (2022). Professional development in multicultural education: what can we learn from the Australian context? Teach. Teach. Educ. 114:103701. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103701

Abdul-Jabbar, W. K. (2023). Sustaining Qatari heritage as intercultural competencies: towards a global citizenship education. Globalis. Soc. Educ., 1–13. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2023.2248460

Almendarez, L. (2013). Human capital theory: implications for educational development in Belize and the Caribbean. Caribbean Q. 59, 21–33. doi: 10.1080/00086495.2013.11672495

Arifin, I., and Hermino, A. (2017). The importance of multicultural education in schools in the era of ASEAN economic community. Asian Soc. Sci. 13:78. doi: 10.5539/ass.v13n4p78

Arsal, Z. (2019). Critical multicultural education and preservice teachers’ multicultural attitudes. J. Multicult. Educ. 13, 106–118. doi: 10.1108/JME-10-2017-0059

Aspers, P., and Corte, U. (2019). What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual. Sociol. 42, 139–160. doi: 10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7

Aydin, H. (2013). A literature-based approaches on multicultural education. Anthropologist 16, 31–44. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2013.11891333

Banks, J. A., and Banks, C. A. M. (2010). Multicultural education: issues and perspectives. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

Benediktsson, A. I. (2022). The place of multicultural education in legal acts concerning teacher education in Norway. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 14, 228–242. doi: 10.1080/2005615X.2023.2164972

Cahaya, A., Yusriadi, Y., and Gheisari, A. (2022). Transformation of the education sector during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Educ. Res. Int. 2022:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2022/8561759

Cathrin, S., and Wikandaru, R. (2023). Establishing multicultural society: problems and issues of multicultural education in Indonesia. J. Civics 20, 145–155. doi: 10.21831/jc.v20i1.59744

Cherng, H.-Y. S., and Davis, L. A. (2017). Multicultural matters: an investigation of key assumptions of multicultural education reform in teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 70, 219–236. doi: 10.1177/0022487117742884

Choi, S., and Lee, S. W. (2020). Enhancing teacher self-efficacy in multicultural classrooms and school climate: the role of professional development in multicultural education in the United States and South Korea. AERA Open 6:2332858420973574. doi: 10.1177/2332858420973574

Creswell, J. W. (1999). Chapter 18 - mixed-method research: introduction and application. In G. J. Cizek (G. J. Cizek Ed.), Handbook of educational policy (455–472). Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Academic Press.

Čulić-Viskota, A. (2018). Investigation into multicultural readiness of maritime students: a maritime English lecturer’s view. Trans. Marit. Sci. 7, 84–94. doi: 10.7225/toms.v07.n01.009

El-Atwani, K. (2015). Jewish, Catholic, and Islamic schooling in Canada. Multicult. Perspect. 17, 53–58. doi: 10.1080/15210960.2015.996389

Ennerberg, E. (2022). Being a Swedish teacher in practice: analysing migrant teachers’ interactions and negotiation of national values. Soc. Identities 28, 296–314. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2021.2003772

Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., and Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 48, 2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117

Ford, D. Y. (2010). Multicultural issues: culturally responsive classrooms: affirming culturally different gifted students. Gift. Child Today 33, 50–53. doi: 10.1177/107621751003300112

Fruja Amthor, R., & and Roxas, K. (2016). Multicultural education and newcomer youth: re-imagining a more inclusive vision for immigrant and refugee students. Educ. Stud., 52, 155–176. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2016.1142992

Gay, G. (2023). Educating for equity and excellence: Enacting culturally responsive teaching. New York, NY, USA: Teachers College Press.

Hastie, P. A., and Wallhead, T. (2016). Models-based practice in physical education: the case for sport education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 35, 390–399. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2016-0092

Idris, M., Tahir, B. S. Z., Wilya, E., Yusriadi, Y., and Sarabani, L. (2022). Availability and accessibility of Islamic religious education elementary school students in non-Muslim base areas, north Minahasa, Indonesia. Educ. Res. Int. 1–11 doi: 10.1155/2022/6014952

Ikasari, W. S. D. (2020). Education, pedagogy, and identity: the notion of historical, political, and sociopolitical experiences of Indonesia in educational research. Ling. Pedago. J. Engl. Teach. Stud. 1, 106–118. doi: 10.21831/lingped.v1i1.27087

Kelle, U. (2022). “Mixed methods” in Handbuch Methoden der empirischen Sozialforschung. eds. N. Baur and J. Blasius (Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 163–177.

Kerebungu, F., Pangalila, T., and Umar, M. (2019). The importance of multicultural education as an effort towards Indonesian national awareness. Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Science 2019 (ICSS 2019). Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Kirk, D. (2004). Framing quality physical education: the elite sport model or sport education? Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 9, 185–195. doi: 10.1080/1740898042000294985

Li, J., Ai, B., and Zhang, J. (2020). Negotiating language ideologies in learning Putonghua: Myanmar ethnic minority students’ perspectives on multilingual practices in a borderland school. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 41, 633–646. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1678628

Liu, X. (2022). Comparing multicultural education in China and Finland: from policy to practice. Asian Ethn. 23, 165–185. doi: 10.1080/14631369.2020.1760078

Llevot-Calvet, N., and Garreta-Bochaca, J. (2025). Intercultural mediation in school. The Spanish education system and growing cultural diversity. Educ. Stud. 51, 679–699. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2024.2329894

Maama, H. (2021). Institutional environment and environmental, social and governance accounting among banks in West Africa. Meditari Account. Res. 29, 1314–1336. doi: 10.1108/MEDAR-02-2020-0770

MacPhail, A., Kirk, D., and Kinchin, G. (2004). Sport education: promoting team affiliation through physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 23, 106–122. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.23.2.106

Mariyono, J. (2019). Stepping up from subsistence to commercial intensive farming to enhance welfare of farmer households in Indonesia. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 6, 246–265. doi: 10.1002/app5.276

Meetoo, V. (2020). Negotiating the diversity of ‘everyday’ multiculturalism: teachers’ enactments in an inner city secondary school. Race Ethn. Educ. 23, 261–279. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2018.1497962

Mills, G. E., and Gay, L. R. (2019). Educational research: competencies for analysis and applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: ERIC.

Nieto, S. (2017). Re-imagining multicultural education: new visions, new possibilities. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 9, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/2005615X.2016.1276671

Poulter, S., Anna-Leena, R., and Kuusisto, A. (2016). Thinking multicultural education ‘otherwise’ – from a secularist construction towards a plurality of epistemologies and worldviews. Globalis. Soc. Educ. 14, 68–86. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2014.989964

Raihani, R. (2018). Education for multicultural citizens in Indonesia: policies and practices. Compare 48, 992–1009. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2017.1399250

Reeves, S., Albert, M., Kuper, A., and Hodges, B. D. (2008). Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ 337:a949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a949

Slamet, S., Agustiningrum, M., Soelistijanto, R., Handayani, D. A. K., Widiastuti, E. H., and Hakasi, B. S. (2021). The urgency of multicultural education for children. Universal J. Educ. Res. 9, 60–66. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2021.090107

Sleeter, C. E., and Grant, C. A. (2007). Making choices for multicultural education: five approaches to race, class and gender. 6th Edn.

Tashakkori, A., and Creswell, J. W. (2008). Editorial: mixed methodology across disciplines. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2, 3–6. doi: 10.1177/1558689807309913

Tualaulelei, E., & and Halse, C. (2024). A scoping study of in-service teacher professional development for inter/multicultural education and teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students. Prof. Dev. Educ., 50, 847–861. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2021.1973074

Tyer-Viola, L. A., and Cesario, S. K. (2010). Addressing poverty, education, and gender equality to improve the health of women worldwide. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 39, 580–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01165.x

Walker, T., Liyanage, I., Madya, S., and Hidayati, S. (2019). “Media of instruction in Indonesia: implications for bi/multilingual education” in Multilingual education yearbook 2019: media of instruction & multilingual settings, 209–229.

Wezel, A., and Soldat, V. (2009). A quantitative and qualitative historical analysis of the scientific discipline of agroecology. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 7, 3–18. doi: 10.3763/ijas.2009.0400

Young, J. L. (2020). Evaluating multicultural education courses: promise and possibilities for portfolio assessment. Multicult. Perspect. 22, 20–27. doi: 10.1080/15210960.2020.1728274

Yusriadi, Y., and Hamim, S. (2022). Development of pluralism education in Indonesia: a qualitative study. J. Ethnic Cult. Stud. 9, 106–120. doi: 10.29333/ejecs/1207

Keywords: multicultural education, teacher agency, centralized education system, primary schools, Indonesia

Citation: Afifuddin A, Amri M, Latif A, Rosmini R and Bin Tahir SZ (2025) Negotiating multicultural values within centralized education systems: a case study of Indonesia. Front. Educ. 10:1620685. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1620685

Edited by:

Marta Moskal, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Dwi Mariyono, Universitas Islam Malang, IndonesiaTria Ina Utari, Institut Agama Islam Negeri Ambon, Indonesia

Muhamad Taufik Hidayat, Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Afifuddin, Amri, Latif, Rosmini and Bin Tahir. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Afifuddin Afifuddin, YWZpZnVkZGluYTE5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Afifuddin Afifuddin

Afifuddin Afifuddin Muhammad Amri

Muhammad Amri Abdul Latif1

Abdul Latif1 Saidna Zulfiqar Bin Tahir

Saidna Zulfiqar Bin Tahir