- Arabic Language Institute to Non-native Speakers, Teachers Preparing and Training Department, Islamic University of Madinah, Medina, Saudi Arabia

Second language acquisition (SLA) has gradually shifted toward an emphasis on learner autonomy. If learners take responsibility for their own learning processes, they can achieve success. Thus, this article discusses how learner autonomy plays a role in SLA of Arabic to non-native speakers in the light of Foucault’s Discourse and Institutional Power, Bernstein’s Classification and Framing Theory, and Self-Determination Theory (SDT). The focus is on how activities during structured educational systems affect the nature of student engagement and motivation in connection with control over learning. The presentation of the discussion is based on empirical and theoretical studies that demonstrate that autonomy can shift teachers’ and students’ dynamics and also contribute to boosting learner motivation and language proficiency. Arabic language education as an area of focus is dedicated to sociocultural and religious dimensions as they connect with institutional structures. Based on the findings, the argument for adaptive teaching models, which allow for learner agency, sociocultural considerations, and interdisciplinary curriculum design, is presented.

1 Introduction

In today’s interconnected world, the command of several languages has become highly valuable, with Arabic standing out as a language in high demand (Alsaawi, 2022). Therefore, second language acquisition has given significant importance to the idea of learner autonomy (Yildiz and Yucedal, 2020). At present, learner autonomy has gained importance in second language acquisition (SLA). Autonomy is defined as a learner’s ability to take ownership of their educational process, choose how to achieve their educational goals, monitor their progress, and check their results (Bajrami, 2015). This view echoes contemporary educational communities’ emphasis on active, student-led learning rather than traditional, instructor-driven models (Little, 2007). Studies have found that key attributes for success in language mastery, such as motivation, critical thinking, and self-regulation, are nurtured by learner autonomy (Al-Khasawneh et al., 2024). By giving autonomy, you can greatly increase proficiency for people learning another language, since you give them the opportunity to discover tasks and persevere in their own way of speaking.

To coincide with these findings, it supports learners to reach a broad range of resources from digital platforms to multimedia materials to interactive tools that research has proved are more dynamic than traditional means (Chapelle, 2001). For adults, this flexibility is especially advantageous as they generally bear other commitments and need to be able to schedule their learning, a finding borne out by the studies on lifelong learning (Knowles et al., 2015). The teacher’s role also shifts from that of a dominating authority to a supporting guide, rather than a directional one in the learning process. This transformation, furthermore, not only promotes sustained learning habits but also develops the most crucial of such vital skills that enable people to become flexible and problem solvers (Benson, 2011). While autonomy requires self-discipline, resilience, and effective study habits to yield its benefits, Zimmerman (2002) shows that self-directed learning must be cultivated, offering valuable insights for improving second language learning success.

There is a noticeable gap in research regarding the implementation of autonomy in Arabic language education, particularly in higher education settings. Although autonomy has been explored broadly in language learning, few studies have investigated how educational institutions and pedagogical models influence its development in the context of Arabic language instruction. This study aims to fill these gaps by applying Foucauldian, Bernsteinian, and SDT frameworks to examine how power dynamics, curriculum structures, and motivational theories intersect in promoting autonomy.

This research is important because it integrates education theories from sociology with practical approaches to language teaching. It provides comprehensive insights into the mechanisms of control and knowledge sharing that affect learner autonomy. By applying Foucauldian and Bernsteinian models alongside SDT, this study has addressed significant gaps in understanding the impact of curriculum and authority systems on student autonomy in Arabic language education. Moreover, the research has offered valuable recommendations for educational organizations to update their curriculum design methods and teaching practices to align with current views on learner autonomy and engagement.

2 Literature review

2.1 Foucault’s theory of power

2.1.1 Foucault: concepts of power and control in education

This section discusses Foucault’s theory of power, specifically its pervasiveness in educational institutions and how it is exercised within them. The field of educational management has widely acknowledged Foucault’s ideas, and, unlike other more contentious theories, they have mainly remained the same over time (Pitsoe and Letseka, 2013). Although some debate exists regarding their accuracy or relevance (Butin, 2006; Pitsoe and Letseka, 2013; Wang, 2011), his theories help clarify power and discourse, which significantly influence social and cultural interactions. Foucault’s theory emphasizes the relationship between power and discourse, its effects, and its role in domination within social contexts. Rather than focusing on sovereignty, Foucault argues that power is inherently related to basic institutional structures.

Dreyfus and Rabinow (1983) elaborate further on this, extending it to show how the power dynamics shaped within institutions or discourse become facilitated by forms of knowledge and meaning. ‘Discourse’ has several conceptual dimensions. Generally, it is used in linguistic studies to mean the patterns of speech, language usage, and communication theorizing among certain groups (Pitsoe and Letseka, 2013). Discourse is not limited to written and verbal communication; it includes anything humans say or write. According to Foucault (1978), power and knowledge are never separated from discourse, which is made up of various elements that do not always have a logical structure.

2.1.2 Foucault’s concept of discourse and education

Foucault’s concepts of discourse, knowledge, and power are socially constructed and interdependent. Such implications are important for education, especially for teachers and students. Besley (2005) states that his philosophical framework has an ethical model for understanding classroom management and institutional structures. Therefore, power is not fixed but shifts in hierarchical settings, allowing educational practice to redistribute authority through autonomy, raising traditional teaching methods.

In terms of current Arabic language learning and instruction, teachers have primary control, and as such, a portion of this authority is expected to be transferred to students with advancements in autonomy. Research has indicated that autonomous learning redefines traditional teacher roles, making students responsible for more of their learning (Cullen and Oppenheimer, 2024; Daflizar et al., 2022). Motivation studies also show that autonomous learning helps achieve deeper engagement (Reinders and Benson, 2017). Autonomy approaches offer more interactive learning, as opposed to traditional models where students receive knowledge passively from teachers.

2.1.3 The role of power in educational discourse

In discourse, as a social construct, the power to control communication and discourse topics resides in those in power. In his own words, Foucault (1977) stresses that discourse also dictates who can say what and when, with what kind of authority. For example, in educational institutions, teachers may not be allowed to be flexible with curricula when rigid curricula are imposed on them by senior administrators. According to Graves (2008), practices of curriculum implementation take place in the classroom milieu, influenced by relationships between teachers, students, and subject matter. Foucault (1972) claimed that discourse not only describes objects but also constructs and defines them. Additionally, he points out that power should be studied as an effect of institutions, examined in terms of how power circulates and operates through networks (Foucault, 1977, 1972, 1987).

2.1.4 Pedagogy and power in education

In education, pedagogy is connected to assumptions about the nature of knowledge, what constitutes the legitimacy of knowledge, and how this can be achieved (Foucault, 1987; Deacon, 2006). For Foucault, schools are not just places of control and surveillance but rather sites for reciprocal power: teachers are subject to the examination of students and school administrators. Woolner et al. (2018) agree with this view that discourse is inherent in everyday social practices and has even been visible in the physical structure of schools. Leaders in power determine what should or should not be discussed and define what acceptable discourse is. These boundaries limit the extent to which power can be challenged. What constitutes acceptable discourse expands and contracts over time, and its scope is subject to change. According to Foucault’s principle of discontinuity, knowledge does not develop in a strict, linear fashion but may evolve through interruptions and shifts.

2.1.5 Discourse and the limits of power

Although some scholars agree with Foucault that ‘knowledge is power,’ others argue that discourse could also be used as a weapon of resistance (Pitsoe and Letseka, 2013). Knowledge and power are not preconditions; rather, discourse is a form of control through which they are linked and regulated. For post-structuralists, power is a way of hegemony, in which the oppressed are unaware of cooperating in their submission. Public awareness plays an important role in recognizing true freedom (Pitsoe and Letseka, 2013) because this happens through ingrained social practices where neither the oppressors nor the oppressed fully recognize it. Restricted access to knowledge is not enough to oppress education; societal pressure to conform to dominant norms also breaks the streak of education. Knowledge is considered important, but educators decide what is relevant. Education can either maintain the status quo or be used as a means of social change (Foucault, 1972). Since discourse is a mechanism of domination, it shapes the components of social reality (Pitsoe and Letseka, 2013).

2.1.6 Foucault’s notion of power

In their reading of Foucault’s notion of power, Moss (2002) sees it as a bilateral network in which institutional structures influence each individual’s choices. On the one hand, education is hierarchical, which may be good or bad; structured learning may help a student, while rote memorization may hinder language acquisition. However, some scholars argue that Foucault’s ideas about power and discourse are too narrow and superficial and do not properly apply to education. Butin (2006) compares their interpretations to extremes: either liberating individuals from oppression or trapping them within rigid systems. Foucault’s ideas have also been aligned with types of education (Ball, 2006; Olssen, 2006), but this sometimes fails to capture his views on the dynamism of power and knowledge (Wang, 2011). The application of Foucault’s theories in education changes the power dynamics in classrooms and may affect learning outcomes. Nevertheless, scholars have adapted his ideas to suit their interpretations of power in educational management, sometimes alienating his original point concerning power in educational management. For this study, classroom management is viewed as a complex framework combining theoretical concepts, teaching strategies, and institutional structures for legitimization or institutional equilibrium (Pitsoe and Letseka, 2013).

2.2 Bernstein’s theory: classification and framing

2.2.1 Theoretical foundations of Bernstein’s classification and framing

Bernstein’s theory of knowledge structuring—specifically the power of classification and framing—is fundamental to understanding its impact on learning autonomy. Bernstein, identified by Singh (2002) as a leading theorist in the sociology of knowledge, has made a significant contribution to educational discourse. However, many of his theories have been controversial, as some embraced them while others found his ideas complex and difficult to apply practically within education. Nevertheless, Bernstein placed considerable importance on the environmental forces that shape students’ ability to learn. One of his key contributions to pedagogy is the assertion that less rigid categorization of knowledge and a less structured pedagogical framework enhance learning. Classification refers to how knowledge is organized into curriculum subjects, while framing addresses how knowledge is conveyed to students through pedagogical methods.

2.2.2 Framing and classification in pedagogy

The term “framing,” as defined by Bernstein (2003), refers to the degree of control over the selection, arrangement, pacing, and timing of knowledge for sharing and learning between the teacher and student. This insight suggests that weakened framing, which offers students more control over their learning, contrasts with strong framing in traditional teaching, where students have less control. This shift toward greater student agency is a core element of autonomy in the learning process.

In the same vein, Bernstein refers to classification as the maintenance of boundaries between content. This concept is further expanded by Cause (2010), who argues that classification includes not only subject boundaries but also the environments of education and pedagogy. According to Bernstein (1971), learning is more efficient when it occurs without restrictive subject classes or rigid pedagogical structures. Bernstein (2003) also argues that strong framing diminishes students’ control over their learning while increasing the teacher’s authority. Consequently, a successful learning environment should aim to reduce teacher dominance, allowing students greater agency in the educational process. Research by McLean and Abbas (2009) found that strong framing was particularly common in high-ranking UK universities, while weaker framing was more prevalent in universities with lower rankings, leading to closer teacher-student relationships in the latter context.

2.2.3 Curriculum design and power structures

Bernstein, as cited by Sadovnik (1991), distinguishes between two curriculum codes: collection and integration. Integrated codes are more fluid with respect to subject boundaries compared to collection codes. For example, Yalcinkay et al. (2009) assert that the development of writing skills is interconnected with auditory comprehension, meaning that skills are better learned when they are cross-disciplinarily integrated, aligning with Bernstein’s (1971) preference for less circumscribed knowledge classification. The importance of active curriculum design is central to this perspective, highlighting the role of internal curriculum design in shaping students’ learning experiences. Bernstein (1971) also linked knowledge construction in curricula to prevailing power structures in educational settings. He advocated for integrating curricula and emphasized the interconnection of subjects rather than their separation. He also distinguished between horizontal knowledge, transmitted informally in everyday affairs, and vertical knowledge, organized into academic disciplines. According to Bernstein (Cullen et al., 2012), students must have some autonomy in choosing, ordering, and engaging with knowledge. Bernstein (2000) references Young (2008) and envisions an ideal curriculum as one that extends beyond the school and workplace into “future engagement” with past knowledge applied in future contexts.

2.2.4 Symbolism of classification and framing

For Bernstein, classification and framing are symbolic tools that define how students, teachers, and the overall environment of the classroom interact. Knowledge is structured and transmitted within the school based on power relations, meaning that certain groups dominate. Singh (1997) highlights Bernstein’s advocacy for considering parents and employers as stakeholders in curriculum and policy development to improve educational outcomes. Bishr and Alzahrani (2004) discuss the role of curriculum integration in preparing education for real-life applications in Saudi Arabia. Their recommendations are:

• To include curriculum components that align with practical life.

• To establish a continuum between grade levels.

• To ensure compatibility between theoretical knowledge and technical or applied skills.

Thus, when all relevant parties are involved, this results in the development of a pedagogy with weak boundaries between curriculum subjects, a shift in power from teachers to students, and an organic move toward collaborative learning (Drake and Reid, 2018).

2.2.5 Bernstein’s relevance to modern pedagogy

Bernstein’s theories are especially relevant for assessing current pedagogical methods and the transition toward autonomous learning. The student-centered approach naturally grants students greater independence, allowing for more autonomy in the learning process with less interference from the teacher (Kerimbayev et al., 2023). There is, therefore, a need for a theoretical framework that accommodates this shift—Bernstein’s framework fits this need. According to Bernstein’s classification framework, the curriculum’s content and instruction are so structured that subject boundaries are strongly reinforced. Foucault (1977) argues that it is within the educator’s control where power is predominantly felt. However, to implement this within a given timeframe, coordination among departments may be necessary to create an integrated curriculum that improves advanced language proficiency. By matching teaching methods with students’ cognitive development and assessment strategies, this approach may help students learn more.

Using Foucault and Bernstein as theoretical frameworks can help us understand how teachers and students might approach education differently in different teaching situations, and what this means for curriculum design and the power dynamics in education.

2.3 Self-determination theory in language acquisition

2.3.1 Overview of self-determination theory (SDT)

Edward Deci and Richard Ryan came up with the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which is now one of the most important ways to understand how people learn a language (Ryan, 2017). SDT basically says that human motivation exists on a spectrum from amotivation to intrinsic motivation. The quality of motivation is greatly affected by the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: autonomy (the need to feel like you have control over your actions), competence (the need to feel like you are effective in your environment), and relatedness (the need to feel connected to others).

Deci and Ryan (2000) claim that the main difference between autonomous and controlled types of motivation is important for understanding learning outcomes. Intrinsic motivation (doing something because it makes you feel good) and identified regulation (doing something because you value it) are both types of autonomous motivation. On the other hand, external regulation (doing something to get rewards or avoid punishment) and introjected regulation (doing something because you feel guilty or pressured) are both types of controlled motivation. In language learning, students typically start with restricted motives like meeting parental expectations or passing tests. However, in an ideal learning environment, they can work toward more self-endorsed motivations.

2.3.2 SDT and language learning

These needs for language learning have different parts and dimensions that often overlap and happen at the same time, which has a big effect on how well people learn. Studies show that language learners who have teachers who give them autonomy support, positive feedback that helps them build their skills, and a social environment where they can connect with others tend to stick with it longer, think more deeply, and have much better emotional outcomes (Herrera et al., 2025; Tuan, 2021; Deci, 2012). The strength of this theory is that it focuses on social and environmental factors that may enhance or hinder natural growth processes. Reeve (2009) lists a number of teaching behaviors that encourage independence, such as listening to students’ points of view, giving relevant reasons for assignments, and giving students options without making them feel pressured. Language teachers who do these things on a regular basis assist in meeting students’ psychological requirements. This leads to more involvement in the classroom, lower dropout rates, and increased motivation to learn a language. Furthermore, when students’ environments are conducive to meeting these requirements, they are more inclined to investigate the target language outside of the formal classroom setting. It is possible to ensure that learners feel both capable and connected by providing them with satisfaction of competence through appropriate scaffolding and of relatedness through pleasant classroom dynamics. This has the effect of improving the overall learning experience for learners.

2.3.3 Motivational strategies in language teaching

SDT’s use in language learning settings has led to many important discoveries about the best places to learn. The teaching method that gives students choices, does not use controlling language, and values each student’s point of view fosters greater intrinsic motivation and better self-directed learning (Yuksel, 2010). Competence support, which entails the integration of informational feedback with optimally challenging tasks, is a method by which learners sustain their motivation during the challenging phases of language learning (Srinivasa, 2022). Lamb (2017) posits that language learning is facilitated by positive interactions between learners, instructors, and fellow students, which in turn helps students feel more at ease taking risks with the language. Teachers are very important in helping students move from external to more internalized states of motivation. In classrooms that foster autonomy, students can communicate with one another in a democratic way, and they feel confident speaking the target language without worrying about being corrected or made fun of. Competence is developed not only via praise but also through constructive criticism, activities that are well-structured, and encouragement to create personal goals. Additionally, Reeve (2009) highlights the fact that learners can acquire confidence through frequent monitoring that does not include any pressure. Boosting students’ self-efficacy and encouraging them to reflect on their own progress can be accomplished through activities such as self-assessment exercises and open-ended diary reflections, for instance.

2.3.4 Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation in language learning

Self-Determination Theory posits that intrinsic motivational factors are more influential than extrinsic motivators, such as grades and rewards, as they promote deeper cognitive processing and enhance retention. Self-Determination Theory provides a robust framework for analyzing motivation patterns in various educational settings and cultural contexts within language instruction (Noels et al., 2003). With their fundamental study, Noels et al. (2003) proved that students who learnt a second language out of personal interest or affiliation with the language community reported higher levels of intrinsic motivation and lower levels of anxiety. This was a significant finding. Students whose learning was motivated by fear of failure or other outside forces reported lower levels of satisfaction and often stopped studying sooner. This fits with the assumption that intrinsic drive makes people more likely to remember a language, be creative, and want to communicate honestly. Moreover, students with integrated motivation who completely understand the value of learning a language are more likely to be successful in the long run and often want to be multilingual for the rest of their lives.

2.3.5 SDT in Arabic language learning

SDT reveals motivational processes in the acquisition of the Arabic language, particularly in the context of Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), due to its distinctive features. Arabic is a triglossic language, which poses obstacles to the development of learner autonomy. Based on their objectives, learners are required to select from a variety of Arabic dialects: Quranic Arabic for religious education, business Arabic for professional purposes, or regional dialects for cultural heritage (Albirini, 2014). The structured variety choice model is supported by research, as it results in increased learner motivation and program retention, which is consistent with the principles of SDT regarding autonomy satisfaction (Wahba et al., 2022). Muslim learners are motivated by the religious significance of Arabic, which is achieved through self-determined regulation (Bakar, 2010). The importance of autonomy in goal setting is reflected in the fact that the student has the freedom to select the type of Arabic vocabulary that they prefer to concentrate on, such as Modern Standard Arabic, Classical Arabic, or Egyptian Arabic. Students are more motivated when they can choose dialects that match their personal, spiritual, or professional interests. This also helps learners build their skills since they can better understand the context in which they are using language. Using dialectal comparisons, real audio samples, or culturally relevant themes in the classroom makes students feel more connected, especially heritage learners or those learning Arabic to strengthen their religious identity.

2.3.6 Cultural and religious contexts in Arabic learning

It is very hard to learn Arabic because of its complicated writing system and morphological structure. Grammar-translation methods that emphasize correctness over communicative skills reduce student competency (Bakar, 2010). SDT-based techniques that use structured exercises and embrace a variety of performance requirements, such as faith-based comprehension and conversational skills, result in greater motivated outcomes (Roark, 2009). The concept of competence is perceived differently by academic students and heritage students. Heritage students prioritize family communication over Modern Standard Arabic proficiency. Consequently, it is imperative to provide adaptive competence support in order to inspire these pupils (Wahidah, 2025). Reeve’s (2009) ideas about competency are very useful in this situation. Competence should not just mean being able to speak and write correctly or pronounce words correctly. It should also entail being able to communicate meaningfully in your social and religious settings. For instance, a heritage student who can talk to their grandparents in a particular dialect should be seen as competent in that area. Students are more motivated and achieve better results when their teachers validate a variety of expressions of proficiency, which fosters a sense of competence and respect. Moreover, making classroom activities that include Islamic literature or cultural storytelling helps students learn the material and the beliefs behind it, which builds both competence and independence.

2.3.7 Cultural sensitivity and SDT in Arabic education

In the Arabic context, SDT constructs are expressed differently, emphasizing the manner in which these fundamental concepts adapt to native cultural and linguistic contexts to establish unique motivational characteristics for language learners. Learning Arabic is quite hard because of strict educational standards that do not take into account the cultural and religious needs of students. Al-Batal (2007) says that not including religious value in Arabic lessons makes students less motivated to learn. Adding religious and cultural themes to school materials makes students more interested and helps them remember what they learned for a longer time. Khatib et al. (2011) claim that teaching that includes literature and is culturally relevant can help students become more motivated and improve their language skills. When students read Arabic poetry, religious writings, or proverbs that relate to their lives, they become more emotionally connected to the language. This shows the SDT principle of relatedness: language is no longer merely a subject, but an important element of the learner’s life. Moreover, teachers who accept different religious views and let students talk about their values and beliefs make classrooms where students are naturally motivated. This kind of culturally sensitive teaching is extremely important in Arabic education because language, faith, and tradition are all interrelated.

Learner autonomy is widely recognized as a key factor in language learning. However, the research specifically focusing on its implementation in Arabic language education remains limited (Hussein and Haron, 2012). The prior studies have not adequately addressed how institutional structures and pedagogical frameworks intersect to influence the development of autonomy in the context of Arabic language instruction. Furthermore, Arabic language teaching presents unique challenges due to its triglossic nature (Chaleila and Garra-Alloush, 2019), which is not always adequately addressed in current autonomy research. This gap highlights the need for a more tailored approach that integrates Foucauldian, Bernsteinian, and SDT frameworks to explore how power, knowledge, and motivation interact in this specific educational setting. As noted by Benson (2011), research on autonomy has largely focused on Western language contexts, with limited attention to non-Western educational settings.

The primary objective of this study is to explore how Foucauldian power relations, Bernstein’s concepts of classification and framing, and SDT can inform and enhance the development of learner autonomy in Arabic language education. The study will aim to offer a deeper understanding of how power dynamics, curriculum design, and motivational theories impact the learning experience of Arabic students. This study has addressed the following research questions:

1. How do Bernstein’s concepts of classification and framing affect the delivery of the curriculum and student agency in Arabic language education?

2. In what ways is Foucault’s theory of power relevant to the development of learner autonomy in language education?

3. How does Self-Determination Theory (SDT) explain the relationship between learner autonomy and motivation in language acquisition?

4. How can the integration of Foucault, Bernstein, and SDT inform pedagogical practices that support learner autonomy in Arabic language education?

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

This study uses a qualitative research approach to investigate how learner autonomy is used in Arabic language classes. A literature synthesis method is utilized to narrate the viewpoint of the studies on the experiences and points of view of Arabic language teachers and students. Particularly, the focus of the research was to sort the literature on theories of Foucault, Bernstein, and SDT.

3.2 Data collection procedures

The data were gathered from the prior studies focusing on the related theories considered for the research. First, the search strings were developed, and then the data were searched for Google, WOS, Scopus, and other databases. Second, a list of articles based on the theories was developed. Third, the screening was done to consider only the related articles that focused on Foucault, Bernstein, and SDT theories in the context of our research. The process of selection and screening took 15 days without any assistance.

3.3 Analytical techniques

The data gathered for this literature synthesis were manually added to an MS Excel file. In the second step, each article was read thoroughly, and the important points were highlighted. In the third step, the highlighted information on Foucault’s theory of power, Bernstein’s ideas about classification and framing, and SDT was compiled.

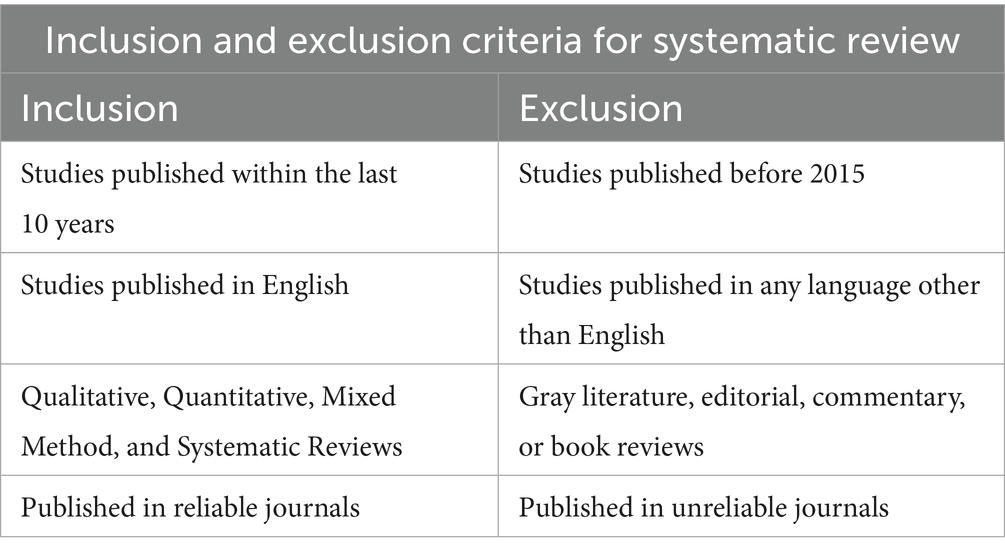

The process of reviewing articles started with setting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The articles published within the last 10 years were considered for review. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed by two academic experts, with the assistance of one expert librarian. The committee of experts also provided ethical approval. Table 1 shows the criteria.

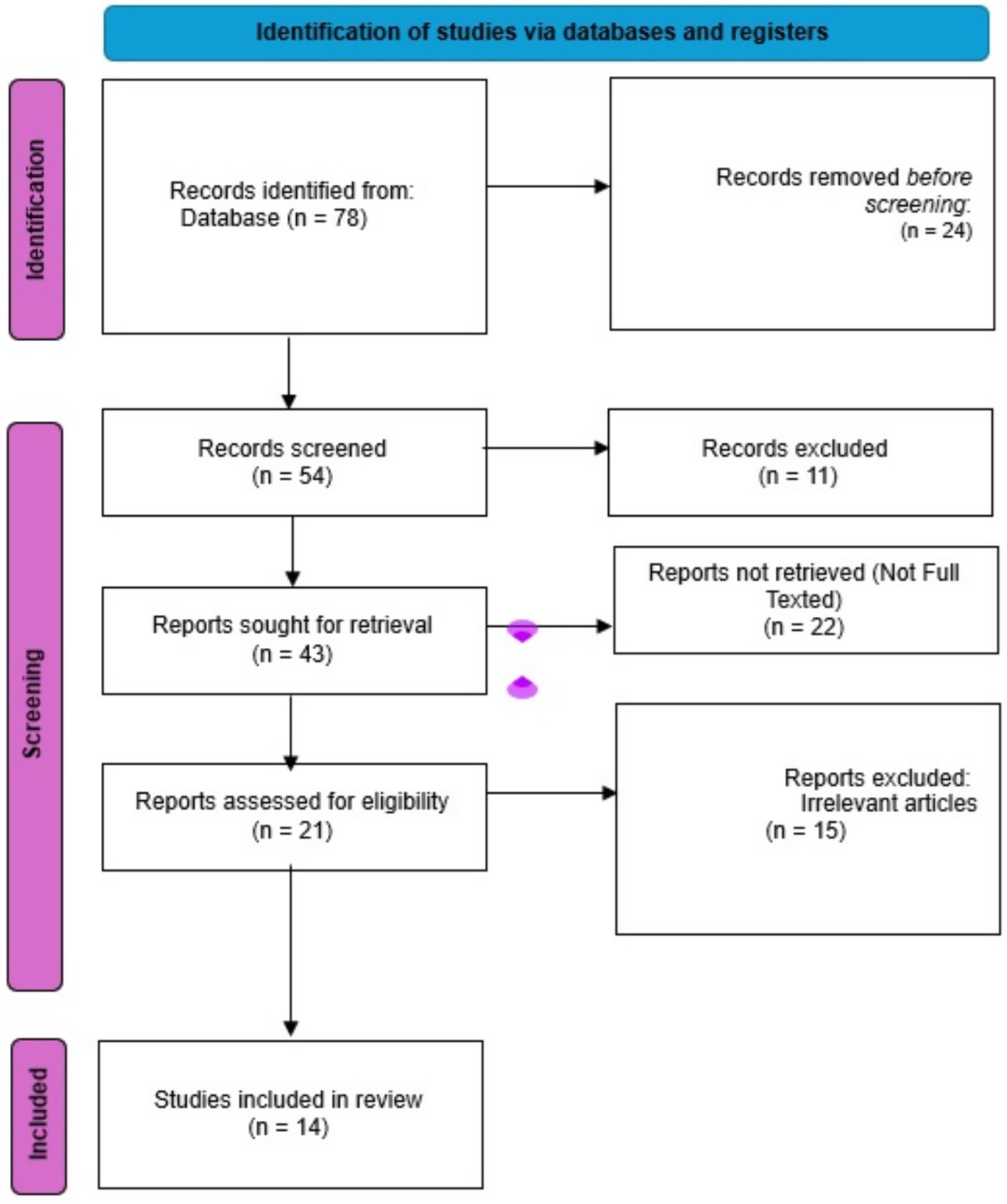

A search strategy was developed based on the criteria. According to that strategy, a list of reputed publishers was developed, and each database was searched for the relevant studies. The whole process took 10 days from 2 June 2025 to 12 June 2025. The initial investigation presented 78 studies, and among them, 24 were removed before screening. Among the remaining 54 records, 11 were excluded, and the remaining 43 were further screened. Twenty-two records were excluded again as their text was not available. From the remaining 21, 7 articles were removed as their themes were different, and the final 14 studies were considered for the review as presented in Figure 1.

4 Findings

Language learning is especially constrained by the presence of power and control over the linguistic situation. The theoretical framework for these processes is provided by the concepts of pedagogic discourse, classification, and framing as articulated by Bernstein (1990). Decisions about which forms and competencies will be emphasized, and who will have access to language resources, trigger the manifestation of power in terms of which knowledge is distributed among learners. Bernstein describes strong classification, where language components are clearly separated (e.g., grammar, vocabulary, speaking, and writing), and boundaries are established along conventional ways of segmenting language teaching (grammar, vocabulary, speaking, writing, etc.). Research supports this, suggesting that such rigid separation enhances mastery of discrete skills but inhibits the holistic use of language (Richards and Rodgers, 2014). More specifically, the opposite occurs with weak classification, which blurs these distinctions and promotes the integrated approach seen in communicative language teaching. This approach has been shown to facilitate the development of contextual understanding and fluency (Ellis, 2003).

In Bernstein’s terms, framing controls the dynamics of teacher-student interactions (Bernstein, 1990). Centralizing authority with the instructor becomes strong framing, which emphasizes grammar over other learning content, teaching strategies, and space for evaluation. This approach guarantees consistency and depth in rule-based learning (Larsen-Freeman, 2011). However, weak framing allows more control to be passed to the learners, as seen in student-centered models such as task-based learning and immersion courses. Here, students ‘drive’ and define challenges for themselves, suggesting topics, participating in authentic exchanges, and choosing topics in line with their interests (Dörnyei, 2001).

Given these dynamics, educators can create language learning environments that offer both structure and flexibility in response to different learner needs. These environments depend on more flexible classification and framing, which Bernstein associates with autonomy. Interdisciplinary connections are facilitated through weak classification, allowing learners to connect knowledge across domains. At the same time, weak framing gives learners the agency to control the pacing and engagement in learning, enabling them to view the world through their learning experiences (Bernstein, 1971). Practically, this aligns with student-centered approaches (e.g., communicative and task-based learning), where learners use language in real-life situations, make choices, and cultivate their skills through self-directed learning. Studies have shown that such autonomy fosters independence and long-term mastery (Benson, 2011).

Power and control are interlocking elements that define dynamic educational interaction within close teaching environments. Bernstein (2003) defines classification as how educational subjects should be kept distinct from one another, while framing refers to how organized communication takes place in the learning environment. Through Foucault’s theory of power, people and their actions are scrutinized, and subtle methods of enforcing discipline and standardization are employed (Foucault, 1984). Together, these two theories provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms governing educational environments.

The process of classification within the pedagogical moment determines what counts as legitimate knowledge. Imagine a teacher giving a lesson as it was prescribed, with no deviation or tangential discussion. This represents a strong classification. In this interaction, the teacher holds the power to define what is or is not acceptable discourse, fixing the boundaries of learning within the lesson’s parameters (Bernstein, 2003). This control is tangible, exercised during the act of knowledge transmission. Similarly, the term framing implies control over the transmission of knowledge, exercised through the teaching process. In this scenario, the lecturer dictates the pace, order, and way knowledge is delivered, without consulting how students will engage or participate. The teacher essentially defines how students interact with the learning content and governs their involvement. The power remains with the teacher to structure the flow of information (Wang and Ryan, 2020; Malen, 1994). Thus, Bernstein’s analysis illustrates how the structure of pedagogical exchanges, through classification and framing, not only supports but also creates power dynamics that directly affect the teaching context (Walton, 2025). Foucault encourages us to study how power operates by analyzing specific practices within instructional environments (Ball, 2019). His framework shows that power is not concentrated in one central place but operates as a continuous force through small controlling methods. These disciplinary mechanisms shape behaviors and control relationships while maintaining institutional norms, even without explicit force. Practices like surveillance, normalization mechanisms, and hierarchical observation naturally direct individuals’ thinking and behavior patterns. Through his research, Foucault dismantles traditional perspectives on authority, demonstrating how power circulates through social systems within education (Foucault, 1984).

Disciplinary power is active when a teacher’s subtle techniques—such as observation, correction, and assessment—are employed in the teaching context. This exercise of control is due to the teacher’s strategic gaze, or the way they use their voice or specific questions to guide student responses (Shor, 1996). For example, imagine a teacher monitoring student engagement and subtly correcting behaviors during assessments to rank and categorize student performance (Ross, 1987). This is an example of disciplinary power in action, shaping student behavior in accordance with the teacher’s expectations. This power dynamic also manifests in micro-level practices, such as how a teacher positions themselves in the classroom or uses specific language to assert authority (Heizmann, 2015). A teacher might strategically arrange students’ seating or use language to assert authority—these micro-practices impact student experiences in subtle but powerful ways.

5 Discussion

Foucault’s theory shows that during each teaching interaction, pedagogical control is exerted continuously, defining student behavior and shaping their subjectivity during learning moments (Foucault, 1977). The teacher becomes the instrument through which students’ behaviors and learning experiences are shaped at that precise moment. The organizational power dynamics of teaching knowledge align with Bernstein’s theory, while Foucault’s analysis explains how micro-level disciplinary activities affect students’ behaviors in the learning environment. When these theories are studied in relation to pedagogical acts, it becomes evident how power and control dynamics define teacher-student relationships during learning.

A strategy that empowers students is collaborative learning, where less rigid structures are placed in the classroom, and students share the responsibility for their learning goals through social interaction. Collaborative learning encourages students to engage more actively and reduces barriers like shyness. As Le and Nguyen (2024) and Santos and Castro (2020) point out, autonomy in learning is crucial in constructivist approaches, promoting meaningful collaboration. Group work, for instance, allows students to exercise greater freedom in constructing knowledge. Many students favor learning Arabic in groups because of mutual support and the reduction of challenges such as shyness.

Bernstein (1971) highlights that loosening the strict scheduling of subject boundaries in the curriculum reduces framing. Consequently, when students collaborate, they reach desired educational goals and create knowledge through activities and social engagement (Tobias and Duffy, 2009). The teacher’s evolving role as a facilitator, supporting student interactions rather than lecturing, coincides with student-centered approaches that give students more autonomy. This approach contrasts with teacher-centered models, where the teacher is the main source of knowledge. Autonomy is fostered when authority is delegated to students, providing a less rigid learning environment (Bernstein, 1971). The autonomy granted to students is evident when they independently explore topics beyond the formal curriculum, as framing and classification weaken.

Fairclough (1989) asserts that participation in a learning environment on a voluntary basis internalizes educational ideologies and power structures, granting students agency. As a result, classroom power structures shift toward autonomy and alternative teaching models, demonstrating how traditional teacher domination is replaced by a more flexible role. According to Wang and Ryan (2020), this shift is characterized by diminished teacher authority, with students having more control over what and how they learn. Students are granted more freedom due to this weakened instructional framing, and the teacher’s role transforms from being instructional to structuring and facilitating learning opportunities (Plomp et al., 2007). The student-centered approach ultimately fosters an environment where students actively construct their learning, reinforcing the transformative potential of constructivist education (Kerimbayev et al., 2023).

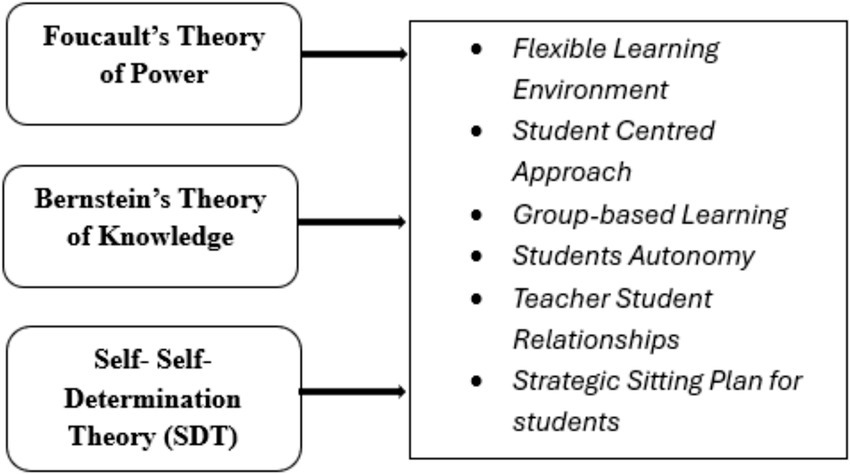

SDT contends that individuals’ high motivation and self-regulated behaviors are based on three psychological needs, namely, autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Therefore, the support of these three needs leads to intrinsic motivation and enhances learning (Ryan and Deci, 2000). In SLA, learners’ autonomy means the willingness and capacity of learners toward learning a second language by evaluating their own goals (Hu and Zhang, 2017). Therefore, besides encouraging planning, it helps learners to monitor themselves and develop appropriate strategies. In the context of Arabic learning, autonomy can enable learners to practice root-and-pattern morphology of the Arabic language and keenly listen to dialect and modern standard Arabic (Calafato, 2020). Thus, Self-Determination Theory is most adequate in theoretically highlighting the importance and significance of learners’ autonomy in the context of learning Arabic as a second language. Furthermore, it postulates that ASL learners’ autonomy leads to motivation and self-regulation that are important for practicing Arabic words. In addition, the growing research on Arabic learning highlighted that learners’ language proficiency is associated with their autonomy and self-regulation. Therefore, program designers of the Arabic language or Arabic language teachers must focus on the autonomy of learners (see Figure 2).

6 Conclusion

In this study, the theories of Foucault, Bernstein, and SDT were used to investigate language education through the lens of learner autonomy. By examining these three frameworks, researchers gain an in-depth understanding of how power works alongside control factors and motivations to influence educational practices. Foucault’s notion of discourse illustrates how communication and behavior are controlled in confined but powerful ways by institutional norms. SDT emphasizes the psychological foundations of learner motivation, while Bernstein’s theories on classification and framing offer a structural explanation of how knowledge is transmitted in educational settings. These theories work together to provide us with a more complete view of how people learn languages. Foucault’s theory helps us understand how institutional discourse might make it harder or easier for students to act in the classroom. On the other hand, SDT stresses the need for psychological freedom and intrinsic drive for long-lasting, profound learning. Bernstein’s emphasis on the structures of information transmission, which include classification (the degree of distinction of subjects or abilities) and framing (the degree of control over learning methods), exposes how traditional systems that are centered on the teacher limit the autonomy of students. These ideas work together to advocate for a change in the way language is taught. The new way should be flexible, focused on the student, and culturally relevant in the way the curriculum is designed and taught. The findings point toward pedagogical approaches that reduce rigid classification and cut down on framing based on teacher-centered methods, moving toward learner autonomy. The adoption of integrated curricula and autonomy-supporting strategies is particularly beneficial for teaching Arabic language instruction, especially when traditional methods dominate. Educational professionals need to act as supportive figures, developing teaching methods that allow students to take control of their educational development. This includes providing choices, scaffolding learning to build competence, and fostering relationships in the classroom.

7 Implications

Teachers need to give up control and change their roles to those of facilitators, helping pupils learn on their own. This means that teachers need to know more about the social and cultural backgrounds of their students. For example, teaching Arabic, including local dialects, religious texts, and cultural backgrounds in the curriculum, gives students a sense of relevance and connection to what they are studying, which makes them more motivated and involved. When you use culturally sensitive teaching methods along with practices that support student independence, you give students the power to establish meaningful connections to their education, which leads to both intrinsic motivation and academic achievement. Furthermore, policymakers and curriculum designers should recognize the importance of institutional reforms that promote pedagogical flexibility and incorporate culturally relevant content, which will support a flexible pedagogical structure.

Policymakers need to look at more than just test scores and rote learning to see how well students are doing. They need to take a more holistic approach that values critical thinking, problem-solving, and creative expression. This can be done by promoting the creation of curriculum frameworks that include student choice, personalized learning paths, and the use of technology to facilitate different ways of learning. Teachers also need to keep learning new things so they can adapt to this student-centered strategy. As schools become more multicultural and multilingual, the requirement for culturally appropriate content grows even stronger. This means that every student should be able to see their own experiences and identity represented in the curriculum.

8 Limitations and recommendations

Future research should explore how these theoretical insights can be applied in practice across various educational contexts, including multilingual and multicultural classrooms. This effort will allow scholars and practitioners to continue developing models of language education that prioritize academic rigor while centering learners’ needs, ultimately helping to create more equitable and empowering learning experiences. Future research should look at how Foucault, Bernstein, and SDT can be used in other educational settings, but it should also look at the real-world problems and benefits of using these frameworks in a variety of cultural and language contexts. Researchers could investigate how different types of schools, such as bilingual classrooms, community-based language programs, and online language learning, can use tactics that foster autonomy. Moreover, cross-cultural research that looks at how these ideas fit with local educational philosophies and practices could help us make language teaching models that work in all situations but are still based on real-life situations. Future research can help push for bigger changes in education by focusing on empirical studies that look at how these frameworks perform in the real world.

Author contributions

SA: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Batal, M. (2007). Arabic and national language educational policy. Mod. Lang. J. 91, 268–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00543_10.x

Albirini, A. (2014). Toward understanding the variability in the language proficiencies of Arabic heritage speakers. Int. J. Bil. 18, 730–765. doi: 10.1177/1367006912472404

Al-Khasawneh, F., Huwari, I., Alqaryouti, M., Alruzzi, K., and Rababah, L. (2024). Factors affecting learner autonomy in the context of English language learning. J. Cakrawala Pendidik. 43, 140–153. doi: 10.21831/cp.v43i1.61587

Alsaawi, A. (2022). The use of language and religion from a sociolinguistic perspective. J. Asian Pac. Commun. 32, 236–253. doi: 10.1075/japc.00039.als

Bajrami, L. (2015). Teacher’s new role in language learning and promoting learner autonomy. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 199, 423–427. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.528

Bakar, K. A. (2010). Self-determination theory and motivational orientations of Arabic learners: a principal component analysis. GEMA Online J. Lang. Stud., 10, 71–86. Available online at: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2010_BakarSulaimanRafaai_SDTandMotivational.pdf

Ball, S. J. (2006). The necessity and violence of theory. Discourse 27, 3–10. doi: 10.1080/01596300500510211

Ball, S. J. (2019). A horizon of freedom: using Foucault to think differently about education and learning. Power Educ. 11, 132–144. doi: 10.1177/1757743819838289

Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. 2nd Edn. Pearson is Harlow in England: Pearson.

Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity: theory, research, critique. Rowman and Littlefield. Lanham. New York. Oxford.

Bernstein, B. (2003). Class, codes and control: The structuring of pedagogic discourse. 2nd Edn. London: Psychology Press.

Besley, T. Foucault, truth telling, and technologies of the self in schools J. Educ. Enq. (2005) 6: 76–98. Available online at: https://ojs.unisa.edu.au/index.php/EDEQ/article/view/503

Bishr, M., and Alzahrani, S. (2004). Johod Almamlakah Alarabiah Alsudiah fee tatweer almnahej [Saudi Arabia’s efforts in the area of curriculum development. Paper presented at the regional workshop on curriculum development]. Held during the period 11-12 December in Muscat, Oman. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1170590.pdf

Butin, D. W. (2006). Putting Foucault to work in educational research. J. Philos. Educ. 40, 371–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9752.2006.00514.x

Calafato, R. (2020). Learning Arabic in Scandinavia: motivation, metacognition, and autonomy. Lingua 246:102943. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102943

Cause, L. (2010). Bernstein’s code theory and the educational researcher. Asian Soc. Sci. 6, 3–9. doi: 10.5539/ass.v6n5p3

Chaleila, W., and Garra-Alloush, I. (2019). The most frequent errors in academic writing: a case of EFL undergraduate Arab students in Israel. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12, 120–125. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n7p120

Chapelle, C. A. (2001). Computer applications in second language acquisition : Cambridge University Press.

Cullen, R., Harris, M., and Hill, R. (2012). The learner-centered curriculum: design and implementation. 1st Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cullen, S., and Oppenheimer, D. (2024). Choosing to learn: the importance of student autonomy in higher education. Sci. Adv. 10, eado6759–eado6710. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ado6759

Daflizar, S., Sulistiyo, U., and Kamil, D. (2022) Language learning strategies and learner autonomy: the case of Indonesian tertiary EFL students Learn. J. Lang. Educ. Acquis. Res. Netw. 15: 257–281. Available online at: https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/LEARN/article/view/256724

Deacon, R. Michel Foucault on education: a preliminary theoretical overview S. Afr. J. Educ. (2006) 26:177–187. Available online at: https://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/74

Deci, E. L. (2012). “Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory” in The Oxford handbook of human motivation. ed. R. M. Ryan (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 85–107.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Drake, S., and Reid, J. (2018). Integrated curriculum: increasing relevance while maintaining accountability. Asia Pac. J. Educ. Res. 1, 31–50. doi: 10.30777/APJER.2018.1.1.03

Dreyfus, H., and Rabinow, P. (1983). Michel Foucault, beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. 2nd Edn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Foucault, M. (1977). “Intellectuals and power” in Language, counter-memory, practice: Selected essays and interviews. ed. D. F. Bouchard. (NY: Cornell University Press), 209–229.

Foucault, M. (1978). The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. (1st ed). New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1984). “The means of correct training” in Crime: Critical concepts in sociology. ed. M. Foucault (London: Routledge), 188–205.

Foucault, M. (1987). The Ethic of Care for the Self as a Practice of Freedom: An Interview with Michel Foucault on January 20, 1984 in The Final Foucault: Studies on Michel Foucault’s Last Works. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 12, 112–131

Graves, K. (2008). The language curriculum: a social contextual perspective. Lang. Teach. 41, 147–181. doi: 10.1017/S0261444807004867

Heizmann, H. (2015). Power matters: the importance of Foucault’s power/knowledge as a conceptual lens in KM research and practice. J. Knowl. Manag. 19, 756–769. doi: 10.1108/JKM-12-2014-0511

Herrera, D., Lira-Delcore, A., and Lira Luttges, B. (2025). Beyond words: the relevance of autonomy-supportive language in university syllabi. Front. Psychol. 16:1536821. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1536821

Hu, P., and Zhang, J. (2017). A pathway to learner autonomy: a self-determination theory perspective. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 18, 147–157. doi: 10.1007/s12564-016-9468-z

Hussein, A. K., and Haron, S. C. Autonomy in language learning. J. Educ. Pract. (2012), 3: 103–111. Available online at: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/view/2018.

Kerimbayev, N., Umirzakova, Z., Shadiev, R., and Jotsov, V. (2023). A student-centered approach using modern technologies in distance learning: a systematic review of the literature. Smart Learning Environment 10, 1–28. doi: 10.1186/s40561-023-00280-8

Khatib, M., Rezaei, S., and Derakhshan, A. (2011). Why & why not literature: a task-based approach to teaching literature. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 1, 213–221. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v1n1p213

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., and Swanson, R. A. (2015). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. 8th Edn. London: Routledge.

Lamb, M. (2017). The motivational dimension of language teaching. Lang. Teach. 50, 301–346. doi: 10.1017/S0261444817000088

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2011). Techniques and principles in language teaching. 3rd Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Le, H. V., and Nguyen, L. Q. (2024). Promoting L2 learners’ critical thinking skills: the role of social constructivism in reading class. Front. Educ. 9:1241973. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1241973

Malen, B. (1994). The micropolitics of education: mapping the multiple dimensions of power relations in school polities. J. Educ. Policy 9, 147–167. doi: 10.1080/0268093940090513

McLean, M., and Abbas, A. (2009). The ‘biographical turn’ in university sociology teaching: a Bernsteinian analysis. Teach. High. Educ. 14, 529–539. doi: 10.1080/13562510903186725

Moss, J. (2002). Power and the digital divide. Ethics Inf. Technol. 4, 159–165. doi: 10.1023/A:1019983909305

Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., and Vallerand, R. J. (2003). Why are you learning a second language? Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. Lang. Learn. 53, 33–64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9922.53223

Olssen, M. (2006). Michel Foucault: Materialism and education. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Paradigm Publishers.

Pitsoe, V., and Letseka, M. (2013). Foucault’s discourse and power: implications for instructionist classroom management. Open J. Philos. 3, 23–28. doi: 10.4236/ojpp.2013.31005

Plomp, T., Pelgrum, W. J., and Law, N. (2007). SITES2006–international comparative survey of pedagogical practices and ICT in education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 12, 83–92. doi: 10.1007/s10639-007-9029-5

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they can become more autonomy supportive. Educ. Psychol. 44, 159–175. doi: 10.1080/00461520903028990

Reinders, H., and Benson, P. (2017). Research agenda: language learning beyond the classroom. Lang. Teach. 50, 561–578. doi: 10.1017/S0261444817000192

Richards, J. C., and Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching. 3rd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roark, M. F. (2009). Effect of self-determination theory-based strategies for staging recreation encounters on intrinsic motivation of youth residential campers. J. Park. Recreat. Adm. 27, 49–62. doi: 10.1300/J007v23n01_02

Ross, M. (1987). Foucault, power/knowledge, and the recent literature on school improvement (Doctoral dissertation). University of British Columbia. doi: 10.14288/1.0055737

Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Santos, J. M., and Castro, M. J. (2020) The use of constructivism and its impact on students’ language satisfaction in language learning. Available at: SSRN. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3549621

Shor, I. (1996). When students have power: Negotiating authority in a critical pedagogy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Singh, P. (1997). Review essay: basil Bernstein (1996). Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 18, 119–124. doi: 10.1080/0142569970180107

Singh, P. (2002). Pedagogising knowledge: Bernstein’s theory of the pedagogic device. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 23, 571–582. doi: 10.1080/0142569022000038422

Srinivasa, K. G. (2022). “Adaptive teaching/learning” in Learning, teaching, and assessment methods for contemporary learners: Pedagogy for the digital generation, Singapore: Springer, 201–240.

Tobias, S., and Duffy, T. M. (2009). Constructivist instruction: Success or failure? New York: Routledge.

Tuan, D. M. (2021). Learner autonomy in English language learning: Vietnamese EFL students’ perceptions and practices. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 11, 307–317. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v11i2.29605

Wahba, K. M., Taha, Z. A., and Giolfo, M. E. B. (Eds.) (2022). Teaching and learning Arabic grammar: Theory, practice, and research. New York: Routledge.

Wahidah, N. S. (2025). Language learning strategies in English fricative consonants through Arabic. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 24, 24–35. doi: 10.61132/ijed.v2i2.286

Walton, E. (2025). The knowledge of inclusive education: An ecological perspective. J. Inclusive Educ. 4, 12–29. doi: 10.4324/9781003319900

Wang, C. (2011). Power/knowledge for educational theory: Stephen Ball and the reception of Foucault. J. Philos. Educ. 45, 141–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9752.2011.00789.x

Wang, Y., and Ryan, J. (2020). The complexity of control shift for learner autonomy: a mixed-method case study of Chinese EFL teachers’ practice and cognition. Lang. Teach. Res. 27, 518–543. doi: 10.1177/1362168820957922

Woolner, P., Thomas, U., Ulrike, T., and Tiplady, L. (2018). Structural change from physical foundations: the role of the environment in enacting school change. J. Educ. Change 19, 223–242. doi: 10.1007/s10833-018-9317-4

Yalcinkay, F., Muluk, N. B., and Sahin, S. (2009). Effects of listening ability on speaking, writing, and reading skills of children who were suspected of auditory processing difficulty. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 73, 1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.04.022

Yildiz, Y., and Yucedal, H. (2020). Learner autonomy: a central theme in language learning. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Stud. 7, 208–212. doi: 10.23918/ijsses.v7i3p208

Young, M. (2008). From constructivism to realism in the sociology of the curriculum. Rev. Res. Educ. 32, 1–28. doi: 10.3102/0091732X07308969

Yuksel, U. (2010). Integrating curriculum: developing student autonomy in learning in higher education. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 7, 35–42. doi: 10.19030/tlc.v7i8.138

Keywords: Foucault, learner autonomy, self-determination theory, language education, Bernstein, Arabic language learning

Citation: Almelhes S (2025) Reframing learner autonomy in Arabic language education for non-native speakers: a theoretical framework of power, control, and motivation. Front. Educ. 10:1622527. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1622527

Edited by:

Reza Kafipour, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Sara Kashefian-Naeeini, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, IranZahra Shahsavar, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2025 Almelhes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sultan Almelhes, cy5hbG1lbGhlc0BpdS5lZHUuc2E=

Sultan Almelhes

Sultan Almelhes