- Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, Madrid, Spain

Background: In vulnerable urban contexts, neighborhood and associative movements often emerge as key responses to structural inequalities and social fragmentation. Recent global crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have intensified the need to strengthen community-based responses and promote more inclusive and sustainable forms of development. Within this scenario, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has the potential to become a powerful driver of social transformation, particularly when applied from a grassroots, community-based perspective. This study examines the role of grassroots neighborhood initiatives in promoting the core principles of ESD, such as equity, inclusion, and democratic participation.

Method: Adopting a socio-educational and participatory approach, this research employed a qualitative methodology based on semi-structured interviews with 40 key actors involved in neighborhood and associative networks. The data were analyzed using the qualitative software Atlas.ti, combining thematic coding with visual tools such as word clouds and semantic network analysis to identify dominant patterns and relationships. The study focused on understanding how fundamental principles of ESD—including equity, inclusion, co-responsibility, and respect for diversity—are integrated into the practices and discourses of these community initiatives.

Results: The analysis reveals strong patterns of cooperation, mutual support, and democratic participation within neighborhood and associative movements. These networks serve not only as mechanisms to meet urgent material needs but also as spaces of informal education and civic empowerment. The incorporation of ESD principles into community dynamics has contributed to the strengthening of the social fabric and to the emergence of new forms of collective agency. In particular, the findings highlight how community-led practices of inclusion and co-responsibility foster critical reflection and shared decision-making, reinforcing social cohesion and contributing to the construction of more just and sustainable neighborhoods.

Conclusion: The study provides evidence that Education for Sustainable Development, when applied from a bottom-up and participatory perspective, plays a strategic role in promoting social transformation in vulnerable settings. By supporting neighborhood and associative movements, ESD contributes not only to addressing immediate social needs, but also to fostering long-term processes of inclusion, empowerment, and sustainability. These findings suggest that ESD should be more widely recognized as a key lever for strengthening community resilience and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) at the local level.

1 Introduction

Neighborhood and associative movements in vulnerable communities have experienced a notable resurgence in the wake of the social crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. As observed in previous crises, such movements have rekindled civic engagement, becoming essential agents of contemporary social life (Crozier and Friedberg, 1977; Lois-González and Piñeira-Mantiñán, 2015). Empirical evidence indicates that the pandemic disproportionately impacted socioeconomically disadvantaged populations (Rodicio-García et al., 2020; Ramos Muñoz, 2022; Julia-Igual et al., 2022), as reflected in the rise of severe material deprivation rates from 4.7 to 7% within a single year (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2020). Against this backdrop, solidarity and mutual aid emerged as critical mechanisms within the most affected districts, reigniting a collective community spirit.

Higher education institutions have increasingly recognized their responsibility to engage with these territories, particularly through service-learning initiatives and participatory research frameworks that bridge academic knowledge and community-based action (Leal Filho et al., 2022). However, there is a lack of empirical research that systematically explores how these interactions generate processes of social transformation, and how they relate to the core dimensions of ESD: participation, equity, critical thinking, and agency.

This study employs longitudinal qualitative interviews conducted before, during, and after the pandemic to examine residents’ perceptions and participation within neighborhood networks and associative movements. It also evaluates the role that the effective operation of these networks plays in fostering community resilience during social crises. The central hypothesis posits that neighborhood movements function as potent tools for mutual aid, fostering inclusive community participation regardless of socio-demographic distinctions. To validate this hypothesis, a series of interviews were analyzed through qualitative methodologies focusing on lived experiences and interpersonal encounters.

Guided by this framework, the research addresses two key questions: How do neighborhood and community movements contribute to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) within vulnerable contexts? What features of these movements facilitate the identification of community learning processes linked to social transformation? These questions underpin the analytical framework and justify the application of a mixed-methods approach. This perspective aligns with recent international scholarship that emphasizes ESD’s capacity to foster critical thinking, democratic participation, and local agency in the face of global challenges (UNESCO, 2020; Bamber, 2022; Barth and Rieckmann, 2023).

1.1 The social and neighborhood movement in Spain

The empirical setting for this research is located in Puente and Villa de Vallecas, districts of Madrid characterized by pronounced social vulnerability. Sordo Medina (2014) documents the neighborhood’s historical development, highlighting the emergence of precarious housing near railway infrastructures and the proliferation of informal settlements and irregular constructions (Burbano Trimiño, 2020). According to Mingorance Jiménez (2002), Vallecas’ population predominantly belongs to lower social strata, evidenced by low educational attainment, high unemployment, and prevalence of low-skilled labor. The district is also home to one of Spain’s largest Roma communities (Abajo and Carrasco, 2004). The neighborhood’s cultural and artistic evolution has significantly contributed to its collective identity. Fernández Montes (2007) argues that post-transition Vallecas consolidated a collective identity grounded in cultural, religious, and ethnic diversity, and underpinned by values of inclusion and solidarity, which are manifested in its neighborhood and associative movements.

This socioeconomic and cultural diversity stems from migratory processes spanning recent decades, initially involving domestic migrants and subsequently international arrivals, thereby reshaping the neighborhood’s social fabric and participation dynamics (Poveda, 2003; Porras-Sánchez and Donati, 2021).

To contextualize neighborhood movements, it is pertinent to consider the broader concept of social movements. These movements have shaped European societies and their arrival in Spain produced varied regional impacts. A hallmark of these movements is their emphasis on collaboration and citizen participation in addressing local issues. As Grau (2001) asserts, social movements seek active involvement in political, economic, and social decision-making.

Such movements are not unique to Spain. Latin American examples include Brazil’s base communities and Argentina’s popular economy networks, which illustrate neighborhood-based organizations as catalysts for social transformation and civic education (Svampa, 2008; Dávalos, 2021; Fox and Rivera-Salgado, 2019). Similarly, in Eastern Europe, urban movements in Poland and Hungary have responded collectively to precarity and authoritarian governance (Jacobsson, 2015), while Italy’s self-managed social centers represent spaces of community learning and political innovation (Mudu, 2004). These examples reinforce the idea that neighborhood movements serve across diverse contexts as platforms for citizen empowerment, ethical development, and the defense of social rights, particularly in settings marked by inequality.

From a theoretical standpoint, Castells (1978) defines social movements as collective actions that, irrespective of success, transform societal values and institutions. Touraine (2006) describes them as organized efforts by actors contesting the historical narrative of their communities. Della Porta and Diani (2011) emphasizes their contentious nature, informal network connectivity, and shared collective identity, while Pérez Ledesma (1994) highlights their appeal to solidarity for social change promotion or prevention.

Focusing on neighborhood movements, Quirosa-Cheyrouze (2011) identifies them as a major urban social current in Europe post-1945, characterized by strategies of political engagement and influence on broader political change (Leontidou, 2006). Jacobsson (2015) underscores their internal heterogeneity, and Mayer (2000, 2007) analyzes their interaction with public policy and European social adjustments. Collectively, these studies underscore neighborhood movements as dynamic social actors that evolve in response to historical and contextual challenges (Della Porta and Diani, 2020; Laraña, 1999; Santamarina Campos, 2010).

In Spain, neighborhood movements played a pivotal role during the democratic Transition, arising organically within neighborhoods and solidifying as structured entities advocating for fundamental rights unmet by state institutions (Recio and Naya, 2004; Martínez Muntada, 2011; Contreras Becerra, 2018). Regional variations exist, with Galicia’s movements linked to economic development and housing (Martínez Pazos, 2021), Castilla y León’s influence on political culture (Gonzalo Morell, 2011; Redondo Cardeñoso, 2021), Andalusia’s autonomy process and urbanization (Contreras Becerra, 2018; Gutiérrez, 2023), and the Valencian Community’s environmental mobilizations (Portalés Mañanós et al., 2020). Across regions, women’s leadership was crucial, especially during formative stages (Ranz, 2011; Bordetas Jiménez, 2016; Bordetas Jiménez, 2017; Fernández Amador, 2018).

1.2 Associationism in Puente and Villa de Vallecas

The associations examined in this study emerged predominantly in the 1980s, closely connected to grassroots churches and parishes and driven by volunteers dedicated to addressing youth and child welfare (PV4, personal communication, June 20, 2017). In parallel, neighborhoods such as Orcasitas experienced robust social mobilizations encompassing the Catholic Church, labor unions, youth movements, and public awareness campaigns (Montañés Serrano and Gómez Sánchez, 2020). As depicted in the documentary Flores de Luna (Vicente Córdoba, 2008), these communities have a legacy of socio-political struggle amid adverse socioeconomic conditions (Martínez Reguera, 2007; Castro, 2007). These new social movements fostered civic participation, closely linked to the Christian Workers Youth in Vallecas (Rodríguez Leal, 2007), positioning Vallecas as a key site of citizen mobilization supported by a dense and diverse associative network. Within this milieu, the neighborhood movement emerged as a driving force behind social transformation (Lorenzi, 2007).

Periods of social isolation fostered heightened collective awareness among residents, who confronted marginalization through autonomous organization. As Molina (1984) notes in Los otros madrileños, Vallecas inhabitants faced legal invisibility, compelling self-reliance and strengthening community bonds.

These associative networks profoundly shaped the social fabric, emerging from grassroots demands for basic infrastructure and services, such as adequate housing, paved roads, and public lighting. A landmark was the founding of the first legally recognized neighborhood association in Spain, the Palomeras Bajas association in Vallecas, a pivotal milestone for the district’s development (Schierstaedt, 2016).

Vallecas’ neighborhood movement has attracted extensive scholarly attention due to its historical and sociopolitical significance (Gonzalo Morell, 2011; Gómez Bahillo, 2008). However, the institutionalization of basic services led to decreased associative vitality, as residents perceived diminished agency in local improvements (Porras-Sánchez and Donati, 2021). Currently, there is a trend toward forming broader networks and platforms—such as the INJUCAM Federation and the Third Sector Platform—aimed at enhancing collective impact.

Neighborhood associations played a central role in transforming informal settlements, which have profoundly influenced Vallecas’ identity (López de Lucio, 1985, 1988). The community’s strong culture of solidarity exemplifies how grassroots action can generate meaningful social change and foster equitable treatment relative to other districts (Figueroa-Saavedra, 1999).

Beyond urban development, these associations assumed important political roles (Castells, 1977). The documentary Somos Tribu Vallekas provides a comprehensive exploration of these groups’ origins and evolution (Somos Tribu Vallekas, 2020).

Vallecas’ resilience and growth are attributable to active resident collaboration, a spirit persisting in today’s associative networks and daily community practices. Contrary to assumptions of decline, community activism thrives—as evidenced by Somos Tribu Vk, a mutual aid platform awarded the 2020 European Citizen’s Prize. Created in response to the COVID-19 crisis, it established a neighborhood safety net, including solidarity pantries, telephone assistance, employment support, and child aid, drawing on Vallecas’ tradition of neighborhood movements and social centers (FS3, 2021).

Neighborhood movements in historically excluded urban settings, community-led initiatives represent vital responses to social inequality, with their role in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) crucial for understanding their transformative potential. ESD advocates for inclusive, equitable, and just societies, principles embodied by neighborhood movements that mobilize communities to address immediate needs and structural challenges (Guardeño Juan and Monsalve Lorente, 2024; Palomino et al., 2022; Alonso-Sainz, 2021).

In contexts marked by deprivation and exclusion, neighborhood movements offer short-term relief (e.g., access to basic resources) while fostering participatory decision-making processes. Thus, they function as spaces of social learning, equipping communities with tools to confront social problems, reinforce solidarity, and promote sustainable development grounded in cooperation and shared commitment.

Within this framework, ESD transcends material concerns to foster critical citizenship capable of driving enduring change. Neighborhood movements foster civic education aligned with ESD principles by encouraging collective reflection on structural inequalities, promoting cooperative organizational models, and valuing diversity through inclusive participation. These experiences also reinforce lifelong learning, as residents develop personal, social, and organizational competencies extending beyond immediate mobilizations into sustained, conscious civic engagement. Consequently, neighborhood movements constitute authentic schools of social transformation from an ESD perspective (UNESCO, 2017).

2 Methodology: a mixed-methods approach

This research follows a convergent mixed-methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011), integrating qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis. While both strands are used to triangulate findings, the qualitative component holds greater analytical weight, as it captures the complexity and depth of community dynamics and lived experiences in structurally marginalized urban areas.

The qualitative approach was developed ad hoc, tailored to the specific context of neighborhood and associative movements. In line with interpretive and constructivist paradigms (Denzin and Lincoln, 2018), the study employed semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and case study techniques to explore the symbolic, pedagogical, and transformative dimensions of community practices related to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

The semi-structured interview guide underwent a content validation process with a panel of five experts in ESD, participatory research, and community studies. Their input, based on relevance, clarity, and alignment with conceptual categories such as participation, equity, diversity, and agency, led to a refinement of the question structure (Escobar-Pérez and Cuervo-Martínez, 2008; Ávila Baray and Martínez Rizo, 2012; Fontana Abad and Ávila Jiménez, 2015).

Complementing the qualitative strand, the quantitative component consisted of a structured questionnaire entitled Perceptions of Community Participation and Social Transformation. The instrument was informed by prior theoretical frameworks in ESD (Wals, 2009; Lehtonen, 2004) and was pilot-tested with a subsample of participants. Expert review confirmed its content validity and internal consistency. The questionnaire explored dimensions such as civic agency, collective action, and sustainability awareness (Tong et al., 2007 & Quemba-Mesa et al., 2023).

Data were analyzed using Grounded Theory, particularly its constructivist variant (Charmaz, 2014), which emphasizes participants’ meaning-making processes. Through iterative coding and constant comparison (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), categories were developed inductively, reflecting the lived experiences of participants. Atlas.ti were used to support the coding process and to generate semantic networks and word clouds, which helped visualize dominant themes and relationships between concepts.

Finally, triangulation of methods—including interviews, observation, and surveys—enhanced the study’s internal validity, while the diversity of participant profiles increased the transferability of findings to other comparable urban contexts.

This investigation is part of a longitudinal qualitative project complemented by quantitative methods (De la Rosa-Ruiz, 2023), aimed at generating a comprehensive, in-depth understanding of neighborhood and associative movements. Over a six-year period, intensive fieldwork enabled the capture of evolving perceptions, experiences, and practices at multiple stages.

2.1 Methodological design and data collection

The qualitative methodology was ad hoc in nature, specifically developed for this study to respond to the unique contextual characteristics of the research setting, in accordance with Ávila Baray and Martínez Rizo (2012), the construction of ad hoc instruments in educational research is justified when the study context is highly specific and not addressed by existing validated tools. This approach ensures relevance, contextualization, and methodological coherence.

The qualitative design adopted in this research was ad hoc, specifically constructed to respond to the contextual specificities of the empirical setting—namely, the dynamics of neighborhood and associative movements in vulnerable urban areas. Rather than relying on a pre-established protocol, the design was developed iteratively and reflexively, in alignment with interpretivist and constructivist epistemologies (Denzin and Lincoln, 2018). This allowed the research tools and processes to evolve in response to the fieldwork and emerging categories from the participants’ narratives. Qualitative data were primarily gathered through semi-structured interviews, chosen for their flexibility and capacity to explore significant facets of participants’ social experiences (Puga and García, 2022). The interview guide was developed based on the study’s objectives and the theoretical framework surrounding ESD and community participation. Themes were grouped into broad blocks to guide the conversations, while allowing participants to introduce new topics spontaneously, thus respecting the natural logic and depth of their narratives. Interviews were scheduled by mutual agreement to accommodate participants’ availability and comfort, fostering a respectful atmosphere conducive to open and collaborative dialog—critical factors for successful qualitative inquiry.

This ad hoc design allowed for deep contextual sensitivity and ensured that the interview protocol reflected the key dimensions of Education for Sustainable Development in historically excluded urban settings.

2.2 Sample selection and characterization

Interviews were conducted face-to-face between 2018 and 2023 within participants’ natural environments—neighborhood associations, community cultural centers—to minimize biases potentially introduced by artificial or institutional settings. This contextualized setting enhanced trust and spontaneity, enriching the data’s authenticity.

The study’s sampling strategy was purposive and intentional, prioritizing heterogeneity (Mucha-Hospinal et al., 2021). Forty participants representing a diversity of community roles—active members of neighborhood associations, immigrant representatives, youth leaders, NGO heads, social educators, and residents engaged in local transformation initiatives—were selected to ensure a multifaceted representation of social realities.

The research also considered socio-emotional and community dimensions, following Núñez del Río and Fontana Abad (2009), focusing on verbal and affective content, analyzed via semantic network tools to elucidate interrelations and emergent meanings.

Complementing interviews, naturalistic observation was employed to document non-verbal cues, group interactions, emotions, and the physical-social context. These ethnographic field notes enriched data interpretation by capturing subtleties beyond verbal exchanges (Flick, 2004).

2.3 Quantitative data collection and analysis

The quantitative instrument, titled ‘Perceptions of Community Participation and Social Transformation,’ was developed ad hoc for this study, based on the conceptual framework of Education for Sustainable Development. The instrument consisted of a structured questionnaire, designed ad hoc in alignment with prior research on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and community engagement (De la Rosa-Ruiz, 2023). The questionnaire was informed by validated theoretical and empirical frameworks in ESD, particularly focusing on dimensions such as social awareness, collective agency, and participatory practices. The scale items were derived and adapted from the works of Wals (2009) and Lehtonen (2004), which offer robust indicators for evaluating sustainability competencies and civic participation. The instrument underwent expert review and pilot testing with a small subsample to verify content validity, clarity, and internal consistency, ensuring its methodological soundness.

This quantitative tool was employed in complementarity with qualitative techniques, specifically semi-structured interviews, which enabled a deeper exploration of participants’ lived experiences, motivations, and narratives. This mixed-methods strategy ensured the triangulation of data and enhanced the interpretive robustness of the findings, in line with recent scholarly contributions emphasizing the transformative role of the university in advancing the 2030 Agenda and locally embedded sustainability (Leal Filho et al., 2022).

Data analysis focused on descriptive statistics (means, modes, standard deviations) and pattern identification to corroborate or challenge qualitative findings. This triangulation revealed significant convergences between respondents’ self-perceptions and interview narratives.

2.4 Data analysis procedures

All interviews were manually transcribed by researchers to ensure fidelity between original discourse and textual data, producing a comprehensive corpus for qualitative analysis. The qualitative data analysis was guided by the principles of Grounded Theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), which allow for theory generation grounded in the participants’ narratives through iterative coding, constant comparison, and category emergence. Specifically, the analysis followed the constructivist variant of Grounded Theory (Charmaz, 2014), emphasizing participants’ meaning-making processes and the co-construction of theoretical categories grounded in their narratives. Through open, axial, and selective coding, themes were iteratively developed and refined, following constant comparison techniques.

Following Taylor and Bogdan (2000), analysis was an inductive, iterative process involving fragmenting, coding, comparing, and reconstructing data to derive theoretically grounded interpretations. Initial thorough readings led to open coding and the emergence of thematic categories.

The analysis followed the principles of Grounded Theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), allowing themes and categories to emerge inductively from the data. Through a constant comparative method, codes were generated from raw data, refined iteratively, and organized into conceptual categories that reflect participants’ lived experiences and the underlying social processes.

Qualitative data were processed using Atlas.ti 25 software, which facilitated systematic coding, category construction, and generation of semantic networks—visual tools depicting conceptual relationships (San Martín Cantero, 2014).

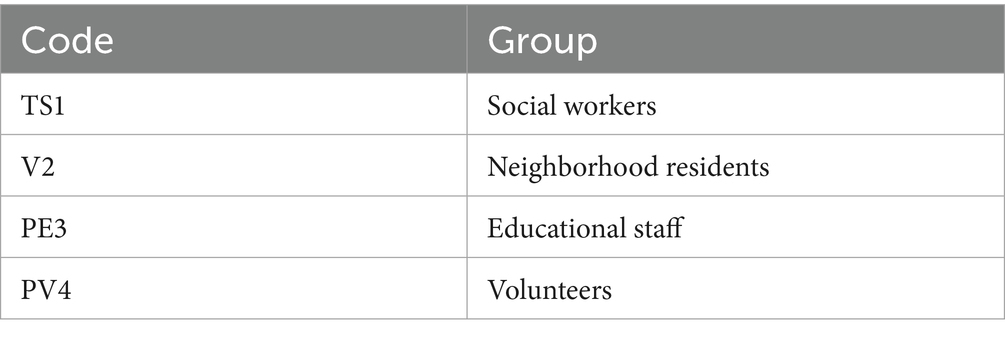

Nineteen codes were meticulously developed to capture key themes (see Table 1), reflecting critical aspects of the phenomena under study (Acevedo, 2011).

The selection of codes was carried out based on two main criteria: the frequency with which they appeared in participants’ narratives and their analytical relevance. Certain concepts emerged repeatedly in the interviews, suggesting that participants—regardless of their role as social workers, residents, educators, or volunteers—shared key perspectives on the phenomenon, such as solidarity, community cooperation, social inclusion, and the impact of neighborhood movements on community development. Thus, the most frequent codes group together ideas and perceptions mentioned on multiple occasions, reflecting their centrality in the collected narratives.

However, less frequent but equally significant concepts were also considered in relation to the research objectives. These codes, though cited less often, offered valuable insights into less visible aspects of the process, such as self-management practices within neighborhood networks or youth participation. Including these categories helped capture the complexity of the phenomenon, enriching the understanding of neighborhood movements as dynamic spaces of learning and transformation within the framework of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

The coding process was not limited to the mechanical grouping of words or phrases into categories; rather, it served as a key tool for interpreting the data (Osses Bustingorry et al., 2006). Through qualitative analysis, patterns of behavior, attitudes, and perspectives emerged, enabling a deeper understanding of the internal dynamics of neighborhood movements and establishing strong links with the principles of ESD.

To ensure rigor, the coding process was structured in several phases, following the recommendations of Borda et al. (2017). First, an exploratory reading of all transcripts was conducted to become familiar with the discourses and identify relevant concepts. During this initial stage, textual excerpts associated with specific themes were identified. These excerpts were then grouped under provisional codes, which were adjusted and refined as new concepts emerged. In total, 19 main codes were defined, each representing a key analytical category. Among the most common were: community solidarity, neighborhood self-management, critical education, and intergenerational cooperation—all fundamental for understanding how neighborhood movements function as non-formal spaces of education and social transformation.

For example, the solidarity and cooperation reflected in participants’ accounts suggest that educational processes in vulnerable contexts go beyond traditional school settings and also unfold within the community sphere. This perspective allows ESD to be approached from a broader and more inclusive standpoint, recognizing alternative forms of knowledge and educational action.

To complement the analysis, word clouds were generated to graphically represent the frequency of key terms in participants’ narratives (De Lucia Castillo and Saibel Santos, 2016). These visualizations served as a preliminary tool to identify thematic areas with high semantic density, guiding the subsequent development of interpretive analysis (Peña-Pascual, 2012). Semantic networks were also constructed from the codes, allowing us to identify complex relationships between concepts and reveal how different dimensions of community participation and ESD intertwine within the narratives of social actors (Noriega et al., 2005). These networks facilitated the visualization of the emerging conceptual structure and provided an effective tool for exploring the meaningful connections between themes addressed in the interviews (Vargas-Garduño et al., 2014a, 2014b).

It is worth noting that, in addition to the standard connectors provided by the analysis software, a specific connector was developed for this study. This resource allowed for a more accurate representation of causal and influential relationships between codes, offering a more refined level of interpretation of the social processes under investigation.

Finally, methodological triangulation—combining interviews, surveys, and direct observation—strengthened the internal validity of the study, while the diversity of participant profiles enhanced the potential transferability of findings to similar contexts. Systematic coding, the progressive construction of categories, and constant comparison of data ensured the reliability of the analysis. The conceptual networks and graphical representations derived from the qualitative process not only facilitated the understanding of emerging patterns but also served as tools for internal validation, enabling the researchers to rigorously and coherently contrast their interpretations with empirical evidence.

It is also relevant to highlight some of the contributions made by the interviewee groups, as presented in Table 2.

“Through neighborhood movements, we have seen how mutual support networks not only meet basic needs but also contribute to the social inclusion of those who are most marginalized.” (TS1)

This statement from a social worker in the neighborhood highlights one of the key findings of the research: neighborhood movements development (ESD) precisely involves this kind of integration and social cohesion, where cooperation and solidarity among diverse social groups are essential to facing collective challenges.

One of the key insights of the study is reflected in the testimony of a social worker from the neighborhood, who emphasizes that neighborhood movements not only address urgent material needs—such as access to food or basic services—but also play a fundamental role in the social inclusion of the most vulnerable sectors of the community. The research highlights how these community networks promote solidarity and a sense of belonging, essential elements for advancing toward sustainable forms of development. Thus, it is not only about providing immediate responses to emergency situations but also about consolidating a more equitable and cohesive social structure, where traditionally excluded groups can participate actively.

“The best thing is that the people here are very diverse, and despite that, we have managed to work together. It shows that when there is solidarity, the community becomes stronger.” (V2)

This quote from a resident underscores the ethnic, cultural, and social diversity of the environment and how, despite these differences, cooperation and solidarity contribute to strengthening community bonds. Within the framework of the study, this statement is directly linked to the positive impact of inclusion and the active participation of all sectors in neighborhood movements. From this perspective, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is manifested in processes of social integration where collaboration among diverse actors is key to addressing collective challenges equitably.

Below are selected excerpts from interviews with professionals in the educational field—both formal and non-formal—that reinforce this educational dimension of neighborhood movements.

“The participation of neighbors in community activities has a great impact on the education of young people. They are learning that collective action is the key to facing social challenges.” (PE3)

This testimony highlights how neighborhood movements function as non-formal learning spaces where young people acquire fundamental notions about cooperation, active citizenship, and collective commitment. The education generated in these environments goes beyond the classroom, promoting values and practices that enable new generations to engage in improving their social surroundings.

“What we have seen with neighborhood movements is that it is not just about receiving help, but also about actively participating in decision-making. This promotes critical education among students.” (PE3)

Here, the participatory nature of neighborhood movements is emphasized as a way to foster critical thinking among young people. It is not only about benefiting from assistance but also about being part of the collective decision-making process. This learning aligns with the principles of ESD, as it encourages reflection on existing social structures and promotes transformation from within the community.

“Young people have become much more involved in community projects. We have observed a change in their way of thinking; now they have a deeper awareness of the importance of cooperation and solidarity.” (PE3)

This statement points to a significant transformation in the attitudes of participating youth. Their involvement in neighborhood projects has fostered an evolution in their understanding of social reality, strengthening their sense of agency and commitment to the community. In contexts marked by crises—such as the pandemic—these experiences can act as catalysts for change, generating lasting learning about social justice, shared responsibility, and sustainability.

“We encountered many families who never thought they would need help, but when the neighborhood networks were activated, people understood the importance of being united and helping each other.” (PV4)

This account evidences how the activation of community networks not only provides material support but also fosters a collective learning process around the value of mutual aid. Such experiences reinforce the idea that ESD can develop from everyday social practices that promote critical awareness, reciprocity, and justice.

In sum, these voices from the territory’s own actors illustrate how neighborhood and associative movements not only respond to immediate needs in vulnerable contexts but also act as genuine educational agents. Through active participation, intergenerational solidarity, and collective work, transformative learning spaces are built. The research confirms that these networks can and should be understood as platforms for Education for Sustainable Development, where fundamental values are cultivated for the construction of a more just, inclusive, and resilient society.

2.5 Critical reflection on possible biases

In order to enhance the methodological transparency of the study, it is necessary to engage in a critical reflection on potential biases, the challenges encountered during data collection, and the implications in terms of the transferability of the results. One of the most significant aspects concerns the position of the researchers within the social fabric being analyzed. Their prior connection with some of the participating neighborhood groups may have influenced both the selection of informants and the interpretation of their narratives. Although mechanisms such as source triangulation, critical data review, and reflective writing were applied, it cannot be ignored that this proximity—while facilitating access and the building of trust—may also have shaped the framing of the findings. Situated research, which characterizes many qualitative studies in community contexts, inevitably involves a tension between engagement and distance that must be acknowledged as part of the research process.

Several practical challenges arose during the data collection phase. The organization of interviews, workshops, and focus groups was limited by the participants’ availability, many of whom balance multiple jobs or caregiving responsibilities. Moreover, some organizations lacked adequate physical infrastructure or stable access to technology for conducting virtual meetings. These limitations affected the continuity of the fieldwork and, in some cases, prevented achieving the desired depth in certain interactions. Additionally, external factors such as political uncertainty, tensions with local authorities, or the proximity of social mobilizations introduced an emotionally charged context that may have influenced the narratives—amplifying or diminishing certain accounts depending on the prevailing climate.

In this regard, it is important to emphasize that the results of the study should be understood as contextualized constructions, shaped by a specific conjuncture and by dense social relationships, not always easily replicable. Although relevant patterns and dynamics were identified in the neighborhood movements of the districts studied, these findings cannot be directly extrapolated to other territories without careful adaptation to the local context. The transferability of the results will depend on the existence of structural and cultural similarities rather than on the possibility of statistical generalization. This limitation does not diminish the value of the study; on the contrary, it reinforces its exploratory nature and its usefulness as a basis for comparative research or action-reflection processes in other neighborhoods or cities.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that ethical considerations were a constant throughout the research process, beyond the fulfillment of formal protocols such as informed consent or the safeguarding of anonymity. In environments where personal relationships, collective memory, and shared history play a central role, the act of researching entails an expanded responsibility. The presence of the researcher may generate unspoken expectations or lead to varying interpretations of their role, requiring an attitude of active listening, respect, and constant adaptation. Ultimately, acknowledging these limitations is not a weakness of the study, but rather an expression of its commitment to a critical, honest, and situated research practice—one that is capable of engaging with its own conditions of production and with the complexities inherent in working in living, transforming territories.

3 Results

The analysis conducted in this research encompassed a total of 12,799 words, highlighting the wealth of information obtained from the interviews. This word count represents the body of data collected from interviews with the various participant groups (see Table 1). Based on this large volume of content, a qualitative coding process was carried out, involving the identification, classification, and grouping of meaningful information into categories. The aim of this process was to extract patterns, themes, and key concepts that would allow for a deeper understanding of participant dynamics and responses in relation to neighborhood movements, solidarity, and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

The coding and categorization of the interview content using codes not only allowed for the structuring of the data, as previously mentioned, but also facilitated a deep interpretation of the informal educational processes taking place within neighborhood movements. This approach reveals not only how these community networks are essential to the local environment but also how they align with the principles of ESD, promoting key values such as cooperation, solidarity, and social justice within the community.

Organizing the data into codes allowed the research to yield key conclusions, which go beyond the immediate outcomes of neighborhood movements to also show how these movements can influence education for sustainable development. For instance, the presence of codes related to participation and critical education suggests that neighborhood movements are not merely reactive responses to crises—they also foster long-term social transformation by engaging the community in decision-making and collective learning.

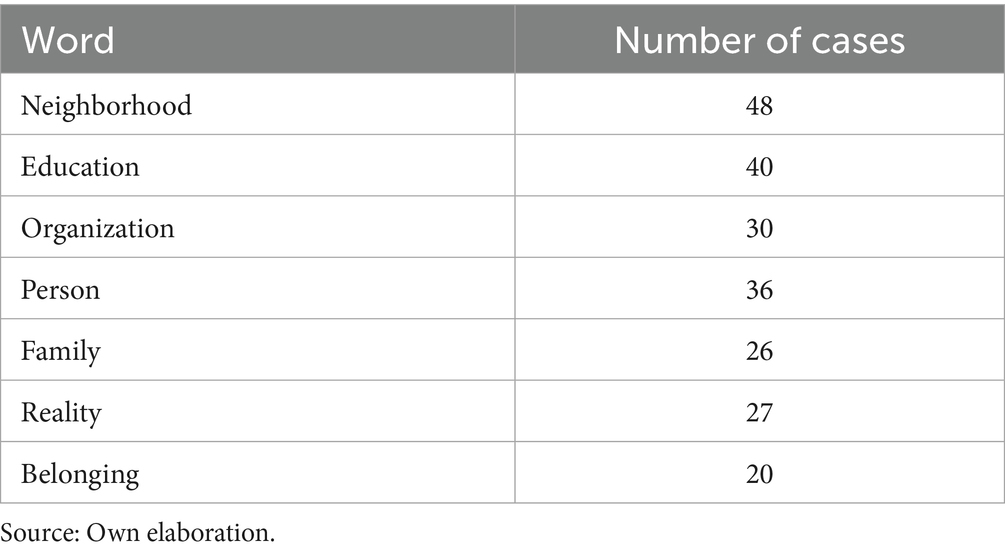

3.1 Word frequency

Table 3 presents the most frequently repeated words, and their frequency provides key insights into the concepts and topics that emerged with the most relevance during the interviews. The analysis of this table enables interpretations regarding the aspects most emphasized by participants in relation to neighborhood movements, education, and community dynamics.

The most repeated terms in Table 1 reflect the central dimensions of the research. The community (neighborhood, family, belonging) emerges as the fundamental space for social action, while education (informal, in values, in cooperation) is the driving force for transformation in these spaces. Entities and individuals indicate the organizational process and the participation of community members, with the aim of improving the reality of vulnerable neighborhoods. This information underlines how neighborhood movements not only provide material support, but also serve as educational spaces that contribute to sustainable development through solidarity, civic engagement and social transformation.

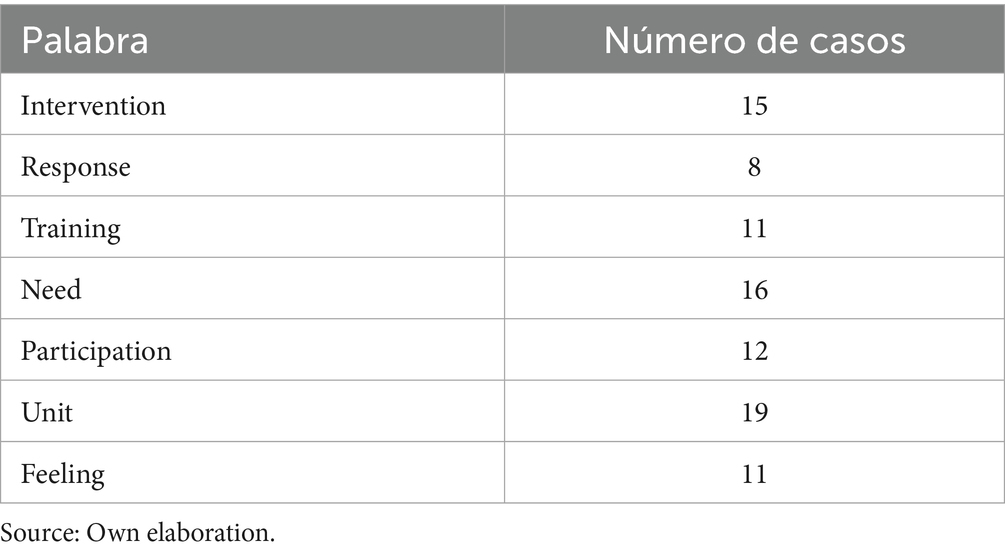

Table 4 presents the least repeated words in the interviews and their frequency of occurrence. Despite being less frequent terms compared to those in Table 1, these words provide complementary and relevant information on the issues addressed in the research.

This table adds complexity to the understanding of neighborhood movements. Intervention and response show how movements address community needs. Formation highlights the importance of education in these processes. Need reflects the social deprivation that motivates community actions. Participation highlights the active role of neighbors in social transformation. Finally, unity and feeling point to the importance of emotional ties and cohesion within the community, essential elements for movements to be sustainable and effective.

3.2 Semantic analysis

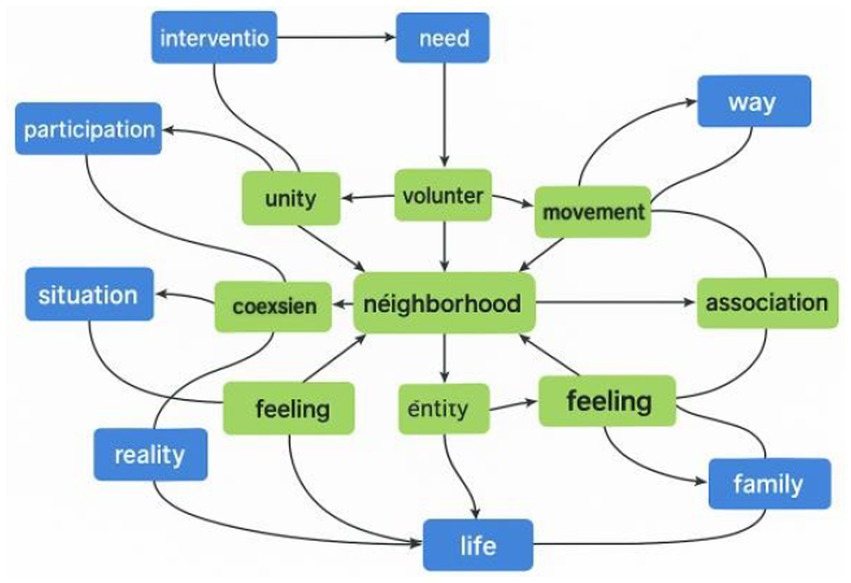

The semantic analysis of the interviews makes it possible to identify the most frequently mentioned concepts in the narratives of neighborhood and community association actors. This visual representation suggests that Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is not conceived by participants as an abstract theoretical framework, but rather as an embodied practice that arises from collective experience, mutual recognition, and the reconstruction of social ties in historically marginalized territories.

From this analysis, five thematic cores emerge that structure the community experience in vulnerable contexts.

The first revolves around spaces of transformation: terms such as neighborhood, movement, organization, and association highlight that the local scale is recognized as the main arena for action and social commitment. Secondly, concepts like person, family, child, young person, and people reflect a focus on human dignity. In this sense, ESD is expressed as a tool that reinforces the sense of belonging and promotes active participation.

A third thematic axis is formed by words like education, training, work, and project, which emphasize the centrality of educational processes, understood not only in their formal dimension but also as practices of collective construction of knowledge and shared commitments. The fourth group includes terms such as coexistence, belonging, value, unity, and reality, which express the ethical and relational dimension of community life. These values, consistent with ESD principles, contribute to strengthening the social fabric from a bottom-up sustainability logic. Finally, words such as administration, program, need, or remain silent reveal ongoing tensions in the relationship between the community and institutions, pointing to structural barriers that limit the continuity and long-term impact of local initiatives.

The semantic network (Figure 1) confirms and deepens these findings by showing how community discourse related to ESD is articulated from the territory—the neighborhood—and extends as a complex web that interweaves educational, emotional, political, and structural dimensions. Social intervention is not perceived as a mere technique, but as a deeply participatory process, rooted in daily life and sustained by the emotional commitment of those involved. In this context, ESD gains meaning as a transformative practice nourished by lived experience and shared action.

At the center of the semantic network, the term neighborhood stands out, directly connected to words such as movement, association, organization, coexistence, unity, volunteer, and feeling. This configuration suggests that the neighborhood is not perceived merely as a physical space, but rather as a relational network where bonds, collective identities, and shared forms of action are built. The significance of this term refers back to what Freire (1970) defined as a “pedagogy of place”: an educational approach grounded in people’s concrete realities, where knowledge emerges from dialog and transformative praxis. In this context, education integrates organically into everyday life, reinforcing the situated, critical, and emancipatory dimension of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). This perspective aligns with the approach proposed by UNESCO (2020), which emphasizes the need for a transformative education capable of linking the global and the local—in a “glocal” logic—and of strengthening the social fabric as a foundation for addressing contemporary challenges.

The analysis of the word cloud and the semantic network reveals a deeply contextualized and interdependent understanding of sustainable development. As Boevé-de Pauw and Van Petegem (2018) point out, education for sustainability, when connected to real community and school experiences, directly influences the development of pro-environmental and social attitudes among young people. Along the same lines, Tilbury (2011) argues that ESD should be conceived as a holistic process that transforms both environments and social relationships, moving beyond a narrow vision focused on school content or isolated actions.

In the network, the terms intervention and need—represented in blue—appear linked to person, participation, and situation, reflecting a shared concern about the structural conditions that motivate social action. Far from understanding intervention as a technical or neutral act, participants conceive it as a form of active presence in the world, lived in coexistence with others. This perspective is consistent with authors such as Subirats (2015) and Novo (2009), who frame sustainability as an ethic of care, connection, and community co-responsibility.

Similarly, in the lower right quadrant of the semantic network, the linkage between education, reality, and life highlights the transformative potential of learning in marginalized contexts. Here, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) transcends the mere transmission of content; it becomes a process of constructing meaning, where knowledge is rooted in daily life and shaped through lived experience.

In the same way, the clustering of terms such as participation, volunteer, and feeling points to a form of civic engagement that is not purely functional, but deeply affective—anchored in mutual recognition, emotional ties, and a shared commitment to the common good.

Concepts like family and local also emerge as structural anchors of community life. Far from being peripheral, these notions represent core dimensions that sustain social transformation from within the everyday. Such findings reinforce the idea that ESD processes unfold in relational, emotionally charged environments, where learning gains significance through collective experience and intersubjective connection.

Taken together, the results indicate that neighborhood movements function not only as platforms for solidarity, but as authentic spaces of collective learning. The prominence of the neighborhood as a semantic category reflects its political and pedagogical centrality—it is within these local territories that active citizenship, critical reflection, and inclusive transformation materialize.

Moreover, the semantic network reveals strong associations between community participation and the development of socio-emotional competences, including empathy, care, and shared responsibility. These findings reaffirm that ESD does not take place exclusively within formal institutions. Rather, it is cultivated through everyday social practice, especially in contexts where communities mobilize to respond to their own needs and shape more sustainable futures from the ground up.

4 Discussion

The findings of this study reinforce the notion that neighborhood and associative movements in structurally disadvantaged urban areas can serve as key enablers of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). These movements provide informal learning environments that promote civic agency, solidarity, and critical reflection, particularly during periods of social and economic crisis (Ruiz Simón, 2024; del Olmo García de Mateos, 2024).

In line with previous research on community learning and sustainability (Tilbury, 2011; Wals, 2009), our results show that grassroots initiatives offer concrete experiences where ESD principles are not only taught but enacted. Participants reported that engagement in neighborhood networks fostered a sense of belonging and social responsibility, echoing the transformative potential of bottom-up approaches described in the literature (Leal Filho et al., 2022; Barth and Rieckmann, 2023).

One of the main contributions of this study lies in documenting how non-formal, territory-based educational practices can build resilience and inclusion from within the community. Rather than framing education as something delivered to communities, the findings highlight a reciprocal model in which communities themselves act as producers of knowledge and agents of change. This supports calls for the recognition of local actors as key stakeholders in sustainability education (UNESCO, 2020).

However, the data also reveal persistent structural tensions. Participants noted a lack of institutional support and insufficient coordination between neighborhood initiatives and formal education or public services. These challenges align with prior critiques of fragmented educational ecosystems and underline the need for integrative policy frameworks that bridge the gap between formal and informal education (Della Porta and Diani, 2020; Novo, 2009).

An important aspect of this study is the emphasis on the emotional and relational dimensions of community learning. Participants described their involvement as rooted not only in strategic goals but also in shared feelings of care, commitment, and collective identity. This reinforces the idea that ESD in marginalized contexts must attend not only to cognitive learning, but also to affective and ethical dimensions of social transformation (Boevé-de Pauw and Van Petegem, 2018).

Finally, this research contributes to the growing body of literature that situates ESD beyond formal educational settings. It highlights the value of everyday practices—mutual aid, neighborhood self-management, collective decision-making—as vehicles for sustainability education, especially in contexts where institutional presence is limited.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that neighborhood and associative movements in structurally marginalized urban areas are not only agents of material support but also dynamic platforms for non-formal education, civic participation, and local sustainability. These community-led initiatives embody the principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)—particularly equity, co-responsibility, inclusion, and critical thinking—through grassroots practices anchored in lived experience.

By applying a mixed-methods approach, the research captures the complex interplay between participation, resilience, and learning in neighborhood contexts. The qualitative strand reveals how collective action fosters informal educational processes and strengthens the social fabric. Quantitative data support these findings by illustrating patterns of civic agency and shared values across different community roles.

These results contribute to the growing body of literature that positions ESD not only within formal institutions but also in community-driven settings. The findings suggest that neighborhood movements should be formally recognized as legitimate educational spaces and strategic actors in the local implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

5.1 Policy and practice implications

• Integrate local knowledge and practices from neighborhood associations into formal ESD programs and curricula.

• Foster collaboration between schools, community organizations, and local governments to strengthen civic engagement and sustainability education.

• Design funding mechanisms and legal frameworks that ensure the long-term viability of community-led educational initiatives.

While the study offers valuable insights into community dynamics in the districts analyzed, its findings are context-dependent and may not be directly generalizable. Future research could apply comparative designs in different cities or countries, as well as explore the longitudinal impacts of neighborhood-based ESD interventions on youth empowerment, social capital, and collective well-being.

Grassroots initiatives in vulnerable urban areas hold transformative potential when viewed through the lens of ESD. They represent powerful, often under-recognized, forces of social learning and democratic agency. Recognizing, supporting, and integrating these movements into broader educational and policy frameworks is essential for building more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable communities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DD: Software, Methodology, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Project administration. PG: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources, Formal analysis, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abajo, J. E., and Carrasco, S. (2004). Experiencias y trayectorias de éxito escolar de gitanas y gitanos en España. Madrid: CIDE: Instituto de la Mujer.

Acevedo, M. H. (2011). El proceso de codificación en investigación cualitativa. Contribuciones a las Ciencias Sociales. Available online at: https://www.eumed.net/rev/cccss/12/mha2.htm

Alonso-Sainz, T. (2021). Educación para el desarrollo sostenible: una visión crítica desde la Pedagogía. Rev. Complut. Eeduc. 32, 249–259. doi: 10.5209/rced.68338

Ávila Baray, J. A., and Martínez Rizo, F. (2012). Diseño y validación de instrumentos para la investigación educativa : Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Evaluación educativa. México D.F.: Trillas.

Bamber, P. (2022). Educating for hope in troubled times: climate and change and the role of education. London: Routledge.

Barth, M., and Rieckmann, M. (2023). Transformative learning and sustainable development: pedagogical perspectives. Sustainability 15:341. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-91055-6

Boevé-de Pauw, J., and Van Petegem, P. (2018). Eco-school evaluation beyond labels: the impact of environmental policy, pedagogical practice and nature at school on student outcomes. Environ. Educ. Res. 24, 1250–1267. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2017.1307327

Borda, P., Dabenigno, V., Freidin, B., and Güelman, M. (2017). Estrategias para el análisis de datos cualitativos : Universidad de Buenos Aires. Metodologías de investigación educativa. Madrid: Síntesis.

Bordetas Jiménez, I. (2016). Aportaciones del activismo femenino a la construcción del movimiento vecinal durante el tardofranquismo. Hist. Contemp. 54, 15–45. doi: 10.1387/hc.17575

Bordetas Jiménez, I. (2017). Aportaciones del activismo femenino a la construcción del movimiento vecinal durante el tardofranquismo. Hist. Contemp. 1, 15–45. doi: 10.1387/hc.17575

Burbano Trimiño, F. A. (2020). La urbanización marginal durante el franquismo: el chabolismo madrileño (1950-1960). Hisp. Nova 18, 301–343. doi: 10.20318/hn.2020.5107

Castells, M. (1978). “La era de la información” in Economía, sociedad y cultura. El poder de la identidad (Alianza Editorial). London: Macmillan.

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Crozier, M., and Friedberg, E. (1977). L’acteur et le système: les contraintes de l’action collective. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

De la Rosa-Ruiz, D. (2023). Measurement and analysis of education for sustainable development in vulnerable environments within the framework of the 2030 agenda. Int. J. Sociol. Educ. 12, 293–316. doi: 10.17583/rise.12351

De Lucia Castillo, F., and Saibel Santos, C. A. (2016). Nubes de palabras animadas para la visualización de información textual de publicaciones académicas. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila.

del Olmo García de Mateos, N. (2024). El futuro está en las aulas: Educación para el desarrollo sostenible y ciudadanía global. Padres Maestros 400, 40–47. doi: 10.14422/pym.i400.y2024.007

Della Porta, D., and Diani, M. (2020). Social movements: an introduction. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. 5th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Escobar-Pérez, J., and Cuervo-Martínez, Á. (2008). Validez de contenido y juicio de expertos: una aproximación a su utilización. Avances en Medición, 6, 27–36.

Fernández Amador, M. (2018). Mujeres en los movimientos vecinales: protagonismo y participación en la España democrática. Madrid: Catarata.

Fernández Montes, M. (2007). Vallecas y su identidad cultural: entre la tradición y la modernidad. Madrid: Editorial Popular.

Fontana Abad, M., and Ávila Jiménez, Z. (2015). Eficacia de un programa conjunto de desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional para padres e hijos con TDAH. Perspect. Educ. 54, 20–40. doi: 10.4151/07189729-vol.54-iss.2-art.3

Fox, J., and Rivera-Salgado, G. (2019). “Mexican migrant civil society” in Accountability across borders. Migrant rights in North America. eds. X. Bada and S. Gleeson (New York: Routledge), 25–52.

FS3. (2021). Somos Tribu Vk: Premio Ciudadano Europeo 2020. Federación de Servicios Sociales Solidarios. Available online at: https://www.fs3.org/somos-tribu-vk

Glaser, B. G., and Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Gómez Bahillo, C. (2008). Movimiento vecinal y políticas sociales en Zaragoza : Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza.

Gonzalo Morell, C. (2011). Movimiento vecinal y cultura política democrática en Castilla y León: El caso de Valladolid (1964–1986). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid.

Guardeño Juan, V., and Monsalve Lorente, M. (2024). Educación para la sostenibilidad y movimientos sociales. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch.

Gutiérrez, V. S. (2023). Nuevos enfoques del urbanismo en Andalucía durante la transición: Un itinerario para su estudio. Hist. Actual Online 61, 173–188. doi: 10.36132/hao.v2i61.2328

Julia-Igual, J., Bernal, E., and Carrasco, I. (2022). Economía social y recuperación económica tras la crisis del COVID-19. CIRIEC-Esp. Rev. Econ. Publica Soc. Coop. 104, 7–33. doi: 10.7203/CIRIEC-E.104.21734

Leal Filho, W., Salvia, A. L., and Pretorius, R. (2022). Handbook of sustainability and higher education. Cham: Springer.

Lehtonen, M. (2004). The environmental–social interface of sustainable development: capabilities, social capital, institutions. Ecol. Econ. 49, 199–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.03.019

Leontidou, L. (2006). Urban social movements: from the ‘right to the city’ to transnational spatialities and flaneur activists. City 10, 259–268. doi: 10.1080/13604810600980507

Lois-González, R. C., and Piñeira-Mantiñán, M. J. (2015). Movimientos sociales urbanos en la crisis actual: El caso de las mareas gallegas. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 73. doi: 10.3989/ris.2015.73.3.e027

López de Lucio, R. (1985). Urbanismo y vivienda en Madrid: La periferia en la dictadura : Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Urbanismo. Madrid: COAM.

Martínez Muntada, R. M. (2011). Movimiento vecinal, antifranquismo y anticapitalismo. Historia, trabajo y sociedad 2, 63–90.

Martínez Pazos, J. (2021). Movimientos vecinales en Galicia. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

Mayer, M. (2000). “Social movements in European cities: transitions from the 1970s to the 1990s” in Cities in contemporary Europe. eds. A. Bagnasco and P. Le Galès (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 131–152.

Mayer, M. (2007). “Contesting the neoliberalization of urban governance” in Contesting neoliberalism: urban frontiers. eds. H. Leitner, J. Peck, and E. Sheppard (New York: Guilford Press), 90–115.

Montañés Serrano, M., and Gómez Sánchez, M. C. (2020). El asociacionismo y la participación vecinal luchando por la vivienda, haciendo ciudad. Háb. Soc. 13, 287–298. doi: 10.12795/HabitatySociedad.2020.i13.18

Mucha-Hospinal, L. F., Chamorro-Mejía, R., Oseda-Lazo, M. E., and Alania-Contreras, R. D. (2021). Evaluación de procedimientos empleados para determinar la población y muestra en trabajos de investigación de posgrado. Desafíos 12, 50–57. doi: 10.37711/desafios.2021.12.1.253

Mudu, P. (2004). Resisting and challenging neoliberalism: the development of Italian social centers. Antipode 36, 917–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2004.00461.x

Noriega, J. Á. V., Pimentel, C. E., and de Albuquerque, F. J. B. (2005). Redes semánticas: Aspectos teóricos, técnicos, metodológicos y analíticos. Ra Ximhai 1, 439–452. doi: 10.35197/rx.01.03.2005.01.JV

Novo, M. (2009). La educación ambiental, una genuina educación para el desarrollo sostenible. Madrid: Pearson.

Núñez del Río, M. C., and Fontana Abad, M. (2009). Competencia socioemocional en el aula: Características del profesor que favorecen la motivación por el aprendizaje en alumnos de ESO. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 20, 257–269. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.20.num.3.2009.11501

Osses Bustingorry, S., Sánchez Tapia, I., and Ibáñez Mansilla, F. M. (2006). Investigación cualitativa en educación: Hacia la generación de teoría a través del proceso analítico. Estud. Pedagog. 32, 119–133. doi: 10.4067/S0718-07052006000100007

Palomino, M. D. C. P., García, A. B., and Valdivida, E. M. (2022). Educación para el desarrollo sostenible y responsabilidad social: Claves en la formación inicial del docente. Rev. Investig. Educ. 40, 421–437. doi: 10.6018/rie.458301

Peña-Pascual, A. (2012). Posibilidades de las “nubes de palabras” para la elaboración de actividades de contenido cultural en el aula de AICLE : Servicio de Publicaciones, Universidad de Navarra. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch.

Pérez Ledesma, M. (1994). “Cuando lleguen los días de cólera. Movimientos sociales: Teoría e historia” in En VV.AA., Problemas actuales de la historia (Madrid: Alianza), 136–159.

Porras-Sánchez, S., and Donati, F. (2021). Territorio, lugar e identidad en los barrios vulnerables: El barrionalismo como práctica política. Ciudad Territ. Estud. Territ. 53, 139–158. doi: 10.37230/CyTET.2021.M21.08

Portalés Mañanós, A. M., Sosa Espinosa, A., and Palomares Figueres, M. T. (2020). Movimientos ambientales en la Comunidad Valenciana. Valencia: Universitat de València.

Poveda, D. (2003). La segregación étnica en contexto: El caso de la educación en Vallecas. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 11, 1–41.

Puga, J. V., and García, M. C. (2022). La aplicación de entrevistas semiestructuradas en distintas modalidades durante el contexto de la pandemia. Rev. Cient. Hallazgos 7, 52–60. doi: 10.69890/hallazgos21.v7i1.556

Quemba-Mesa, M. P., Bernal-García, M. I., Silva-Ortiz, S. R., and Bravo-Sánchez, A. L. (2023). Spanish translation and cross-cultural adaptation of consolidated criteria for reporting about qualitative research. Revista de Psicología 22, 145–164.

Ramos Muñoz, C. (2022). Construcción de la paz desde la cooperación y la solidaridad: COVID-19. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social 35, 349–360. doi: 10.20983/cuadfront.2020.1e.12

Ranz, F. A. (2011). El movimiento democrático de mujeres: Del antifranquismo a la movilización vecinal y feminista. Historia, trabajo y sociedad 2, 33–62.

Recio, A., and Naya, A. (2004). Movimiento vecinal: Claroscuros de una lucha necesaria. Mientras Tanto 91/92, 63–81.

Rodicio-García, M. L., Ríos-de-Deus, M. P., Mosquera-González, M. J., and Penado Abilleira, M. (2020). La brecha digital en estudiantes españoles ante la crisis de la Covid-19. Rev. Int. Educ. Para Justicia Soc. 9, 103–125. doi: 10.15366/riejs2020.9.3.006

Rodríguez Leal, A. (2007). Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 79, 63–79. doi: 10.3989/rdtp.2007.v62.i1.32

Ruiz Simón, E. (2024). Educación para el desarrollo sostenible y responsabilidad social educativa: Una mirada histórica desde la persona. Cuest. Pedag. 1, 69–82. doi: 10.12795/CP.2024.i33.v1.04

Santamarina Campos, B. (2010). Movimientos sociales: Una revisión teórica y nuevas aproximaciones. Bol. Antropología 22, 112–131. doi: 10.17533/udea.boan.6702

Schierstaedt, G. (2016). La primera asociación vecinal en España: Palomeras Bajas. Madrid: La Catarata.

Somos Tribu Vallekas. (2020). Somos Tribu Vallekas. Plataforma Ciudadana. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/somostribuvallekas

Subirats, J. (2015). Otra sociedad, ¿otra política? De “no nos representan” a la democracia de lo común. Barcelona: Icaria.

Svampa, M. (2008). Cambio de época: Movimientos sociales y poder político. Los que ganaron: la vida en los countries y barrios privados. Buenos Aires: Biblos.

Taylor, S. J., and Bogdan, R. (2000). Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación. 3rd Edn. Barcelona: Paidós.

Tilbury, D. (2011). Education for sustainable development: an expert review of processes and learning. Paris: UNESCO.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Vargas-Garduño, M. D. L., Méndez Puga, A. M., and Vargas Silva, A. D. (2014a). La técnica de las redes semánticas naturales modificadas y su utilidad : National University of La Plata. Ciudad de México: UNAM.

Vargas-Garduño, M. D. L., Méndez Puga, A. M., and Vargas Silva, A. D. (2014b). La técnica de las redes semánticas naturales modificadas y su utilidad en la investigación cualitativa. IV Encuentro Latinoamericano de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales : National University of La Plata. Ciudad de México: UAM.

Vicente Córdoba, P. (2008). Flores de Luna : Producciones Clandestino. Madrid: Producciones Doble Banda.

Keywords: education, sustainable, neighborhood movements, social cohesion, community participation, inclusivity

Citation: De la Rosa Ruiz D and Gimenez Armentia P (2025) Education for sustainable development in vulnerable contexts: the role of neighborhood and associative movements. Front. Educ. 10:1623416. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1623416

Edited by:

Diego Gavilán Martín, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Edgar R. Eslit, St. Michael’s College (Iligan), PhilippinesSibongamandla Silindokuhle Dlomo, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Vasiliki Ioannidi, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Copyright © 2025 De la Rosa Ruiz and Gimenez Armentia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel De La Rosa Ruiz, ZC5kZWxhcm9zYUB1ZnYuZXM=

Daniel De La Rosa Ruiz

Daniel De La Rosa Ruiz Pilar Gimenez Armentia

Pilar Gimenez Armentia