- 1College of Humanities and Sciences, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 2Department of English, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan

- 3School of Foreign Languages, Shenzhen Technology University, Shenzhen, China

This research explores the motivational role of teachers in developing and enhancing the English-speaking skills of university students in Punjab Province, Pakistan. Mastery of English is essential since it is used as a global lingua franca in education, science, technology, business, and cultural exchange. However, psychological barriers, traditional teaching methods, and imbalanced assessment systems that place more emphasis on reading and writing rather than speaking hinder Pakistani students from acquiring proficiency in spoken English. The present study explores how teachers, as motivators, facilitators, and feedback providers, can help learners overcome these challenges with the help of a supportive classroom environment by fostering intrinsic motivational orientation of the learners. A quantitative research design in which data was collected from 200 teachers using questionnaires from different university teachers. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using Smart PLS 4.1.0.3 to test associations among motivational constructs, namely, teacher encouragement, classroom environment, and feedback mechanisms, with students’ willingness to communicate in English. The findings of the present study indicate positive and significant associations between teachers’ motivational strategies and students’ speaking proficiency. Self-esteem, anxiety reduction, and willingness to communicate were greatly influenced by teachers’ roles as motivators. However, despite these insights, systemic issues such as the lack of resources, outdated teaching materials, and limited use of technology are some of the setbacks identified in the study. The results point out the need for institutional reforms and teacher training programs focusing on communicative language teaching. The study contributes to an understanding of the pivotal role teachers play in motivating EFL learners and offers practical recommendations to improve speaking skills in English in non-native contexts.

Introduction

Today’s world, which is characterized by interconnectivity, interdependence and technological advancement requires the use of a global language for worldwide interaction. From within several languages, English has emerged as a lingua franca facilitating communication among different nations and people with diverse social, cultural, regional and linguistic backgrounds (Berdimurotovna, 2020; Català-Oltra et al., 2023; Chand et al., 2022; Kramsch, 2014; Pennycook, 2017; Rao, 2019). Kurniawan (2024) has highlighted the importance of the English language as a lingua franca with reference to four fields, i.e., education, science and technology, business and travel, and tourism. Other than these four realms, the role of English with reference to media industry and cultural diversity has also been explored by researchers like Ilyosovna (2020).

In accordance with this multi-faceted and multi-purpose use of the English language, the significance of English has increased in higher education departments because they prepare students for the world of employment where students need to use the English language for communication. This significance was emphasized by Agustin (2015) when he asserted that more and more people rely on the English language to find jobs and excel in them. This predominant role of English in the higher education has been acknowledged worldwide mainly for three reasons. Firstly, English has become the medium of instruction in many countries of the world today. Secondly, all the higher education material and information are available in English in the form of digital and printed books and journals. Finally, students worldwide need to be proficient in English in order to pursue their higher education and enjoy global career prospects. Hence, the use of English has no longer become a luxury. Instead, it has become a necessity in today’s world (Handayani, 2016).

In the wake of this ongoing trend of using English, higher education institutions have placed special focus on the learning and teaching of the English language (Seraj and Hadina, 2021; Younas et al., 2022) because it allows communication among the speakers belonging to different native languages (Canagarajah, 2007; Kadwa and Alshenqeeti, 2020; Jenkins, 2019; Kurniawan, 2024; Zeng and Yang, 2024). With this belief that English is a gateway to avail the chances around the globe for better knowledge and progress, Pakistani institutions are also offering more and more courses with a focus on developing English language skills (Hussain, 2017; Zaidi and Zaki, 2017). Sadeghi and Richards (2021) assert that English language skills are developed in Pakistani institutions to prepare students for the future. Proficiency in the English language will enable the potential students to participate in international conferences, research publications and academic networking which will ultimately help them in their academic endeavors and in availing employment opportunities across the world (Iriance, 2018; Rohayati, 2018).

Mastering the English language requires having a full command of four language skills: listening, speaking, reading and writing. According to Savignon (1991), these skills have been classified into two major categories: namely, receptive and productive skills. The receptive skills, which are listening and reading, rely on students’ ability to comprehend texts and interactions while the productive skills, which are speaking and writing, demand from the learners to produce their messages, thoughts and opinions for others to listen and read respectively. In accordance with this division, the learner of a language must adopt different roles i.e., speaker, writer, listener and reader. According to Brown (2001), these roles are exchanged as there is “a natural link between speaking and listening” (p.275). This exchange of roles helps the learners to understand others’ points of view and convey their opinions as well. It must be noted, however, that the “spoken language and written language differ in many ways” (van Lier, 1995, p.17). These differences are highlighted by Brown (2001) where he differentiated speaking from writing in terms of permanence, processing time, distance, orthography, complexity, vocabulary, and formality.

The globalization and internationalization trends have strongly affected the language learning and educational policies in many non-native English-speaking countries (Getie, 2020; Haufiku et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022; Younas and Dong, 2024). Despite effective language teaching planning and policies, these countries still rank low in global English proficiency (Ahsan et al., 2021; Akram et al., 2021). This is particularly the case when it comes to the speaking skill which can be defined as “the process of building and sharing meaning in a variety of contexts” (Chaney and Burk, 1998, p.13) or “an interactive process of constructing meaning that involves producing and receiving and processing information” [ Flórez, 1999 as cited in Bailey (2005), p.2]. As compared to other skills, the teaching and learning of speaking skills is the most challenging task in non-native English-speaking countries because learners face a variety of challenges when they attempt to speak in English (Akram and Abdelrady, 2023; Mahmood et al., 2025). According to Ur (2012), Ali and Ghazali (2016), ESL learners face psychological, social as well as linguistic challenges while learning to speak English. Learners also feel worried about being criticized for their poor oral production and for making mistakes (Zhang, 2009). Thus, the process of teaching and learning of English-speaking skills has become difficult. As Pakistan too, faces several challenges to improve the learning and teaching of the English language speaking skill in its classrooms (Seyyed Ali and Akram, 2015; Ayesha, 2022; Younas et al., 2025b). The first challenge comes from the learners’ very social environment which promotes their native language. In fact, the already developed L1 patterns in learners’ mind pose a hindrance to learn English (Ali, 2017). Secondly, the Pakistani teaching practices have been traditional since they prioritize the teaching of the reading and writing skills based on a background of the grammar translation method. As a result, Pakistani learners become good at reading and writing English, but they remain shy and reluctant when it comes to English speaking (Ali and Ghazali, 2016). This reluctance is further enhanced by the students’ feeling of anxiety when they speak in English (Ashraf, 2019; Bozkirli, 2019; Horwitz, 2016; Hussain et al., 2021; Sutarsyah, 2017; Zhiping and Paramasivam, 2013). Thirdly, the testing and evaluation system in Pakistani context gives priority to assessing learners’ writing abilities and, hence, ignores the assessment of speaking skills (Alam and Bashiruddin, 2013; Khurshid et al., 2013). This preference given to writing motivates the students to focus on the writing skill and ignore the speaking skill as speaking is given less importance in the grading system.

In addition to the above factors, improving students’ speaking skills in Pakistani classrooms faces other challenges. For example, Al Nakhalah (2016) and Amoah and Yeboah (2021) have highlighted how lack of vocabulary, poor grammar and delayed comprehension constitute significant barriers to enhance leaners’ speaking skills in Pakistan. Additionally, several scholars have highlighted that Pakistani students suffer from interference of L1, poor grammar, lack of vocabulary, lack of English language specialists, lack of separate English spoken classes, lack of technology, poor teaching material and imbalanced assessment methods (Abrar et al., 2018; Afshar and Asakereh, 2016; Ali et al., 2020; Bilal et al., 2013; Yusuf, 2022; Wahyuningsih and Afandi, 2020; Noor et al., 2022; Afzaal et al., 2024).

In this context, the present study aims to develop an understanding of how ESL teachers can play a role in developing the English-speaking skills of university students in Pakistan by motivating them. The following research questions are set to guide the process of data collection and data analysis:

Research questions

1. How can the teachers play a significant role in developing the speaking skills of Pakistani students at university level?

2. What is the role of teachers’ motivation in developing the speaking skills of Pakistani students at university level?

Significance of the study

The present study is significant because it explores the role of motivation in learning the English language with a specific focus on the development of the English-speaking skill. By highlighting the related issues and by suggesting the strategies to motivate Pakistani ESL learners, the results of the study will contribute positively to help ESL teachers to improve their classroom practices.

Literature review

Motivation plays a significant role in the foreign language teaching and learning process. It has been described as a complex and multifaceted construct as suggested by Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011), Gardner (1985), Williams and Burden (1997). According to Dörnyei (1998), motivation initiates the learning and sustains the “tedious learning process” (p.117). Research into how motivation enhances second language learning was initiated by Gardner (1985), who proposed three elements of motivation i.e., motivational intensity, desire and attitude toward learning. He also distinguished between motivation and orientation where orientation serves as a base for motivation. Hence, orientation is the goal which functions as a “motivational antecedent” (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2011, p. 41). While discussing different types of orientations, Clement and Kruidenier’s (1983) highlighted the “relative status of learner and target groups as well as the availability of the latter in the immediate environment” (p. 288). This shift from the socio-educational aspect of motivation to a psychological model was due to the insights offered by Dörnyei (1994, 2003) who emphasized the social and pragmatic dimensions of second language motivation where he clearly divided it into three levels. The first level, language level, is associated with different aspects of a second language including its culture, norms and values. The second level, learner level, refers to the characteristics possessed by the individual learners when they enter a second language classroom. The third level is also crucial as it refers to the learning situation which comprises teaching learning environment, methods and strategies and the effect of human personalities and relationships. All these three levels of motivation work independently. This division of motivation into three distinct levels gave birth to several studies on second language motivation conducted by Dörnyei (2001), Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011), Williams (1994). In addition to these studies, others have revealed that culture and identity are two important variables in L2 motivation (Cortazzi and Jin, 1999). Hence, Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011) proposed that the learning of a second or foreign language is linked with the learner’s personal identity. This concept was named as “L2 motivational self-esteem” which highlights the role of self-motivation in learning a new language.

In contrast to this, the self-determination theory developed by Ryan and Deci (2000) was based on three orientations to motivation: amotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation. The learners with amotivation have no set goal and are unable to see a link between their actions and outcomes. And consequently, according to Ryan and Deci (2000) they fail in language learning. The second type is extrinsic motivation which comes from an external force i.e., a teacher’s appreciation or a reward which motivates the students to learn any language skill. This motivation works but its chances of failing are increased when learners become habitual and are unable to learn on their own without this type of motivation as claimed by Noels et al. (2001). In comparison to this, intrinsic motivation comes from a learner’s internal factors of self-realization and self-motivation which results in a joyful and successful learning of any language skill. This feeling of success and satisfaction in intrinsically motivated learners comes from their sense of autonomy and competence (Ryan and Deci, 2000).

The lack of classroom activities also results in psychological barriers which according to Asworo (2019) are: stress, anxiety, shyness, lack of self-confidence and low motivation. These psychological issues have been monitored from both the teachers’ and students’ perspectives. For example, in his study Suchona and Urmy (2019) has found that the learners’ background and emotional aspects have a direct relation with their speaking performance. Hence, the fears, worries and pressures faced by students must be removed by providing them with a pleasant environment and motivation to speak. Researchers like Choi (2016), Fallah (2017), Young (1999) have also highlighted the role of teachers’ attitude in reducing learners’ anxiety and nervousness. Moreover, (Brown, 2007; Horwitz et al., 1986) has suggested eight factors for the development of the speaking skill which are: self-esteem, self-efficacy, willingness to communicate, inhibition, risk-taking, anxiety, empathy, and introversion and extraversion. Other than these factors the roles adopted by both teachers and learners are also helpful to develop effective communicative skills. According to Harmer (2001), teachers should play the role of prompters, participants, and feedback providers while the learners’ role is to stay imitative, intensive, responsive, transactional, interpersonal, and extensive (Brown, 2007). According to Wang et al. (2025), good and effective teaching is the one where students feel motivated to learn as the teacher adapts to the diverse need of students and helps them to develop confidence by overcoming anxiety in speaking a foreign language i.e., English.

This discussion on the role of motivation in second language learning with reference to the views of different scholars has highlighted how important it is for the teachers to motivate their students in their ESL classrooms. While discussing the affective factors involved in language learning with a particular reference to speaking skill development, Brown (2007) has focused on self-esteem, willingness to communicate, self-efficacy, anxiety, empathy, inhibition, introversion and extraversion and risk-taking. Keeping in mind these eight factors, both the teachers and students must play several roles to make this learning process successful. According to Brown (2007), learners should be responsive, intensive, imitative, interpersonal and transactional. While Harmer (2001) identified the role of teachers as participants, prompters, and feedback providers. It is expected that while playing these roles, the teachers must motivate the learners so that effective learning may take place. The factors effecting the motivation level of the learners have been identified and discussed by several researchers in their studies where they paid a special focus on second language teaching classrooms (Csizer and Dornyei, 2005; Dörnyei and Clément, 2001; Dörnyei and Otto, 1998; Oxford and Shearin, 1994). While investigating the role of teachers in L2 learner’s motivation, the researchers have maintained that the teachers are the most dominant and effective factor in motivating their learners positively where they play the roles of initiators, motivators, facilitators and administrators as well (Dörnyei, 1994; Sakai and Kikuchi, 2009; Tanaka, 2005). It has been suggested by Ramage (1990), Williams and Burden (1997) that teachers’ motivation helps students to actively participate in the teaching learning process where they learn through positive engagement and achieve their target language.

Dörnyei (1994) claimed that teachers’ style of teaching and their use of different teaching strategies along with their feedback motivates the students who as a result develop an affiliation with their teachers. Hence this motivation results in learners’ motivation where they are ready to do a few experiments including receiving feedback, praise or punishment from their teachers to learn a particular language or language skill (Williams and Burden, 1997). Another study conducted by Oxford and Shearin (1994) has proposed that teachers need to identify the reasons behind learning a language and then they need to set achievable goals for their students. After this, they have to inculcate the benefits of learning in their learners and then they are to provide a suitable and welcoming environment to the learners which will lead to an intrinsic motivation among their students.

Framework

This study framework in Figure 1 aimed to find out the problems and hurdles beyond English learning deficiencies among students at university level in Pakistan. It also explores how motivations can be meaningful and effective to develop the interest of the teachers in English classes at university level in Pakistan. English is studied from the very first class and it is a compulsory subject at primary as well as at graduation level in Pakistan. No one can deny the importance of the English language all over the world especially in developing countries like Pakistan. This research throws light on different issues, which become hurdles in learning the English language in Pakistan.

Research method

This section introduces the study methodology. It details the research design, data collection and data analysis that apply to the present study. This study focuses on the role of motivation in enhancing the speaking skill at university level in Punjab Province, Pakistan. In addition, it throws light on the methodology and different tools like survey, questionnaire, population and sampling which have been used to collect data for this study. In fact, this study throws light on the speaking and learning problems faced by students at postgraduate level in rural and urban universities of Punjab Province, Pakistan. In addition, it throws light on how motivational expressions prove meaningful to improve and enhance speaking skill.

Research design

The researchers used the quantitative research design to figure out the role of motivation in enhancing the speaking skill at postgraduate level in Punjab Province, Pakistan. This study deals with speaking problems faced at postgraduate level in Punjab Province, Pakistan. In addition, how motivational expressions prove meaningful to improve their learning as well as speaking skill of students have been discussed. So in order to know the ground realities, the researchers visited differently universities personally and took the views of teachers about problems, interest, motivation and interaction with the students. Therefore, for this study, the researchers selected survey as a method of data collection.

Data collection

The researchers collected the data from teachers in different universities of Punjab Province, Pakistan. In fact, data could be collected through many ways but the researchers selected questionnaire as a tool of data collection and the questionnaire developed for teachers containing twenty (20) different responses about students’ responses, students’ interest, learning problems and teaching methodology as a pilot testing. After some modifications, the final questionnaire consisting of two parts was finalized and data collected from 200 teachers. First part identified the fundamental information about teachers’ likes, their academic qualification, teaching experience, language teaching courses and professional qualifications, while the other portion of the questionnaire presented information on teachers’ responses and views. This questionnaire highlighted all the problems and hurdles in the English language classes which were faced by all the teachers approximately at postgraduate level in universities of Punjab Province, Pakistan.

Data analysis

Smart PLS 4.1.0.3 software has been used for structural equation modeling (SEM) to investigate the correlations between different variables. The PLS-SEM research design is a stable, versatile, and advanced tool for creating a significant statistical model, and the PLS-SEM role helps achieve the intended goal (Yavuzalp and Bahcivan, 2021). Ringle et al. (2015) suggest that PLS-SEM may enable SEM findings with practically any level of structural complexity, including higher-order structures, which reduce multicollinearity problems. Using factor loadings, SEM calculates the model’s discrimination, convergent, and average variance for each construct (Al-Gahtani, 2016). Multivariate analytic approaches may investigate various relationships between variables in the conceptual model.

Results

Descriptive statistics

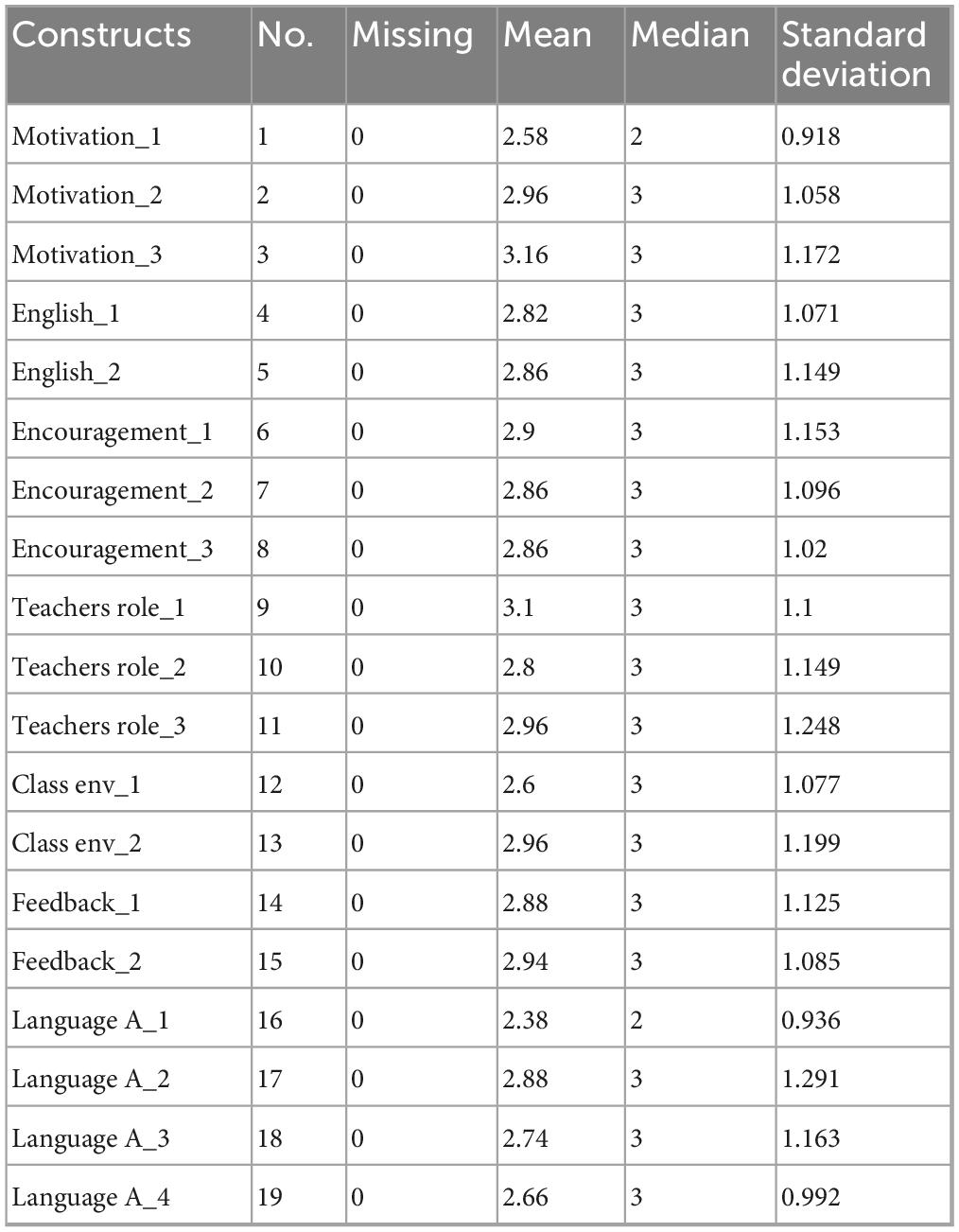

Table 1 depicts the study constructs’ mean scores, standard deviation, excess kurtosis, and skewness values. It has been proven that all of the scales employed in this inquiry to determine the mean scores, standard deviation, excess kurtosis, and skewness values were consistently “reliable” and produced satisfactory results.

Multivariate analysis

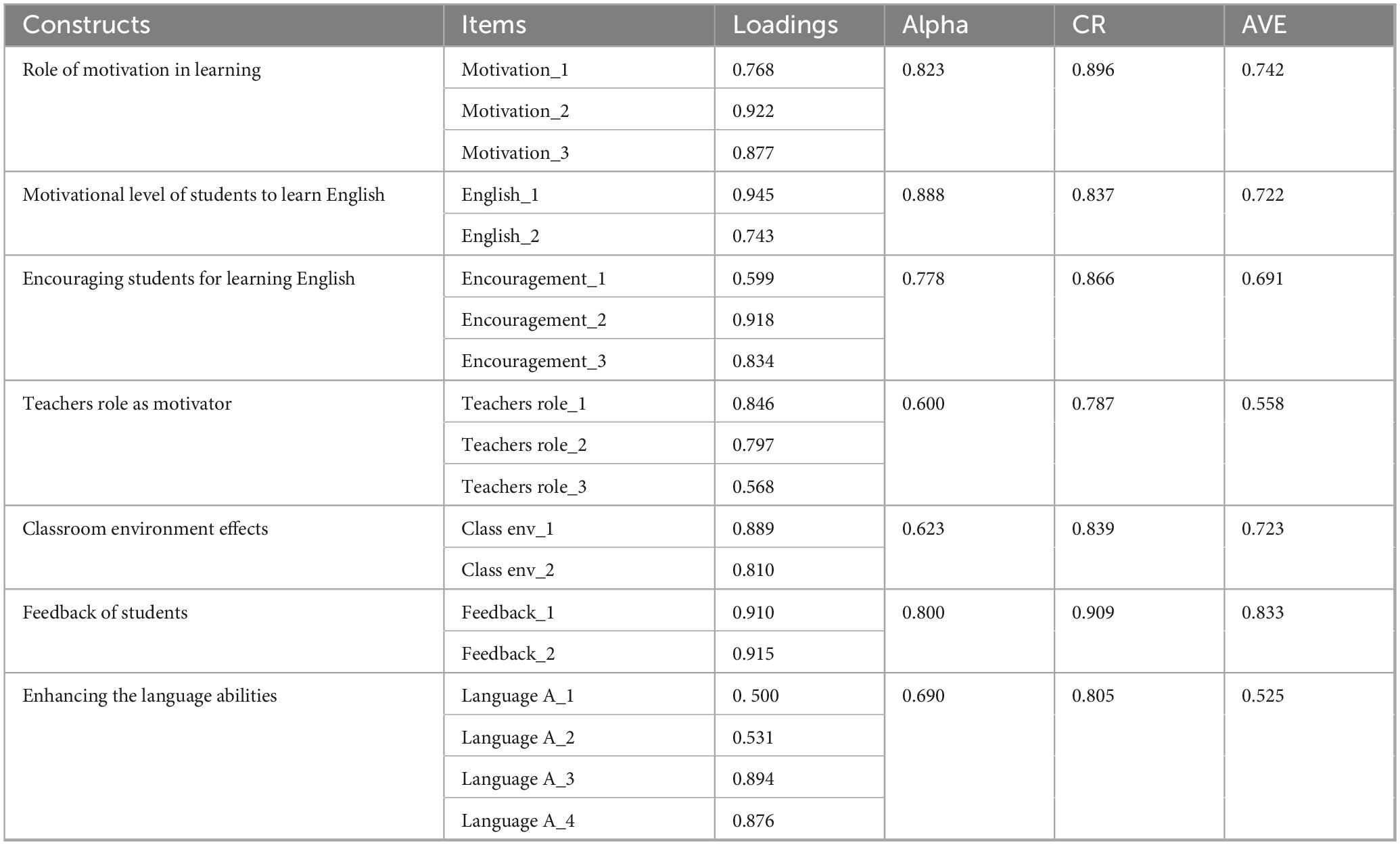

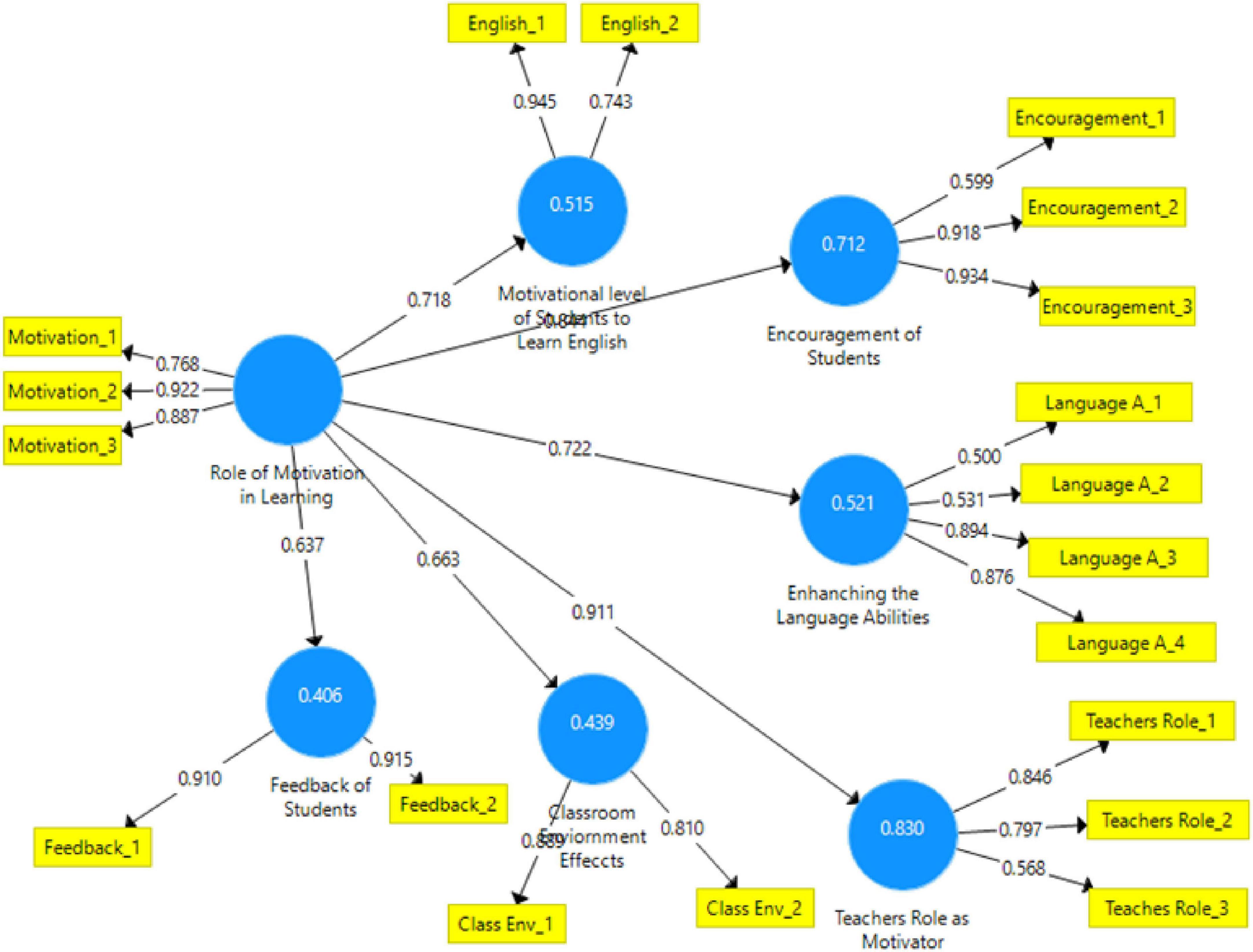

The statistical findings of this investigation are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. The survey’s reliability was assessed using alpha values. According to She et al. (2021), the established alpha value for assessing dependability is more than 0.6, and each component is deemed reliable based on the standard and Cronbach alpha values (ranging from 0.600 to 0.888). Composite reliability (CR) values were obtained (ranging from 0.805 to 0.909). Loading levels consistently surpassed 0.500 in this investigation. The extracted average variance (AVE) is above 0.500. The square root of each construct’s AVE should be more significant than its link with other constructs for discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The AVE values in this investigation were more effective than the average range (from 0.525 to 0.833).

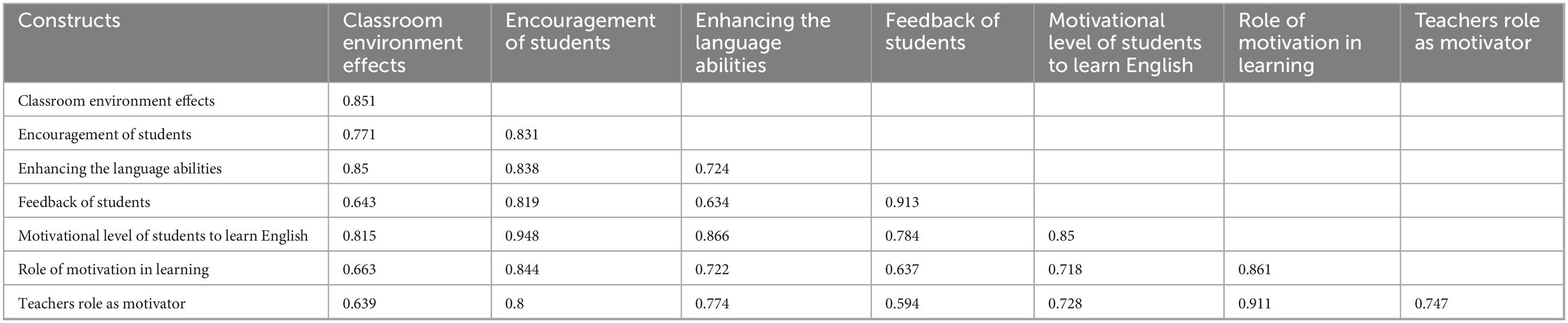

Unrelated constructs were analyzed and described using discriminant validity (DV). Furthermore, DV confirms all component dissimilarity assessments. Analyzing non-statistically linked components is part of DV when figuring out measure correspondence. A factor’s AVE may be used to calculate its DV. According to Table 3, the DV showed that each concept’s square root and AVE was greater than its link to other constructions.

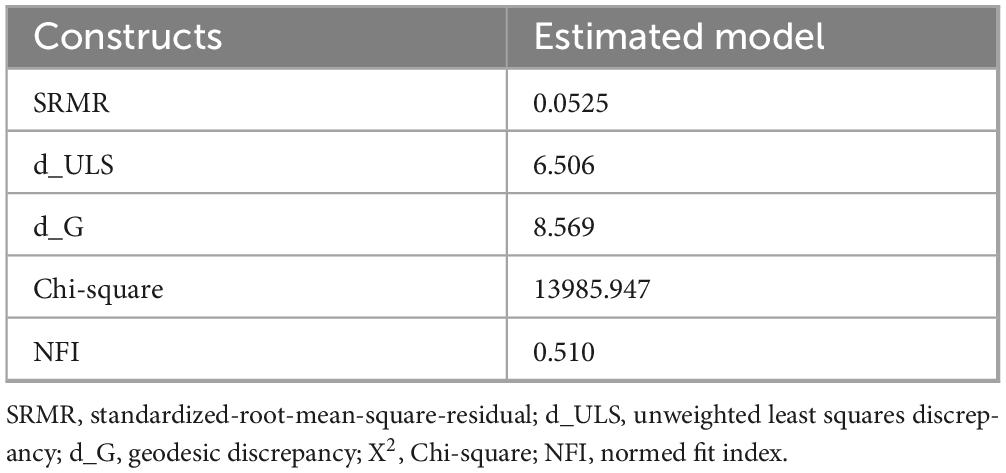

Structural model fitness

All assumptions were verified using Smart PLS 4’s structural equation modeling component (Chin, 2010). The chi-square and normed fit indices (NFI) were computed, as well as the standardized root-mean-square-residual (SRMR), a standardized-residuals index that assesses model fitness. Chen (2007) and Brown (2006) have corroborating data. We examine the dependency on the covariance of the anticipated matrices to obtain the SRMR value. Results are allowed to be used if their SRMR is 0.08 or below. A reasonable degree of model fit is predicted with an SRMR of 0.0525. Table 4 shows that the chi (2) value is 13985.234 and the NFI is 0.510.

PLS bootstrapping

The significance of the structural model for each straight effect was assessed by examining the path coefficients, T-statistics, and P-value. The bootstrapping method was used to calculate the data. The results of the bootstrapping calculation are given in Table 5, which includes information on the path, T-value, P-value, hypotheses, and connection, it also illustrates the T-value and loading value of the path lines during the bootstrapping method.

Discussion

The findings of the present study show that teachers’ motivation plays a significant role in improving the English-speaking proficiency of Pakistani university students. Quantitative results, via the Smart PLS 4.1.0.3 analysis, yielded an array of relationships between motivational constructs, such as teacher encouragement, classroom environment, and feedback mechanisms, with a students’ English-speaking willingness. These findings support earlier studies, such as Dörnyei and Ushioda (2011), Gardner (1985), that signaled the complexity of motivational issues related to second language learning. As motivators, facilitators, and providers of feedback, teachers bear great significance for students’ self-esteem, anxiety level, and overall communicative competence-the issues pointed out by Brown (2007), Harmer (2001).

This study highlights the importance of creating a supportive class environment. This result aligns with the following statement of Suchona and Urmy (2019), in which some psychological barriers, including anxiety, shyness, and low self-confidence, can be reduced if the teacher encourages them and gives feedback in class. In the Pakistani context, where traditional teaching methods often prioritize reading and writing over speaking (Ali and Ghazali, 2016; Younas et al., 2024a,b), teachers must adopt innovative strategies to foster oral communication. For instance, incorporating interactive activities, group discussions, and role-playing exercises could enhance students’ fluency and confidence. The positive correlation between classroom environment effects (Class Env_1 and Class Env_2) and students’ motivation to learn English (English_1 and English_2) supports this recommendation.

Besides, this study points out the importance of intrinsic motivation in language learning. According to Ryan and Deci (2000), learners with intrinsic motivation tend to show more self-determination and competence. This intrinsic drive can be fostered by the teacher through the use of achievable goals, relevant feedback, and celebrating small successes. This approach serves not only to build students’ self-efficacy but also to reduce their fear of making mistakes, a critical barrier identified in ESL classrooms (Ur, 2012; Ali and Ghazali, 2016; Younas et al., 2025a). Importantly, the high loadings for “Motivation_2” and “Motivation_3” in the structural equation model further underscore the importance of fostering intrinsic motivation among learners.

Nevertheless, it also unfolds challenges peculiar to the Pakistani educational milieu. Lack of technology, inadequate teaching materials, and inappropriate imbalance in the assessment methods impede speaking skill development. Abrar et al. (2018); Afshar and Asakereh (2016) point out that such systemic issues may indicate that, while teachers may indeed act as a source of motivation for students, institutional support is also indispensable for long-term improvement. Relatively lower mean scores of “Language A_1” and “Language A_4,” assessing the language ability of students, indicate the development of resources and training programs which could be availed by teachers and students.

Conclusion

The present study examined the motivating role of teachers in enhancing Pakistani university students’ English-speaking skills. The findings of this study assert that teachers should not be just passive conveyors of knowledge; rather, active agents in constructing students’ attitude, confidence, and proficiency in spoken English through a supportive classroom environment, reasonably set goals, and multiple approaches to teaching can stimulate students in overcoming psychological impediments and accept the process of language learning positively.

The findings of this study extend beyond the confines of the classroom. With English continuing to remain a lingua franca in higher education, professional fields, and international communication (Kurniawan, 2024; Handayani, 2016; Alotaibi et al., 2025; Thavabalan et al., 2020), helping Pakistani students improve their speaking prowess is a foregone conclusion to their academic and professional pursuits. Policymakers and educational institutions must be prepared to understand that systemic reforms including updated curricula, better resources, and communicative language teaching-oriented teacher training programs are very much required.

But even as teachers hold the potential for transforming ESL classrooms into dynamic language practice spaces, their efforts have to be supplemented by changes in institutions and society at large. It is through addressing these challenges collectively that Pakistan can narrow the gap in proficiency in English speaking and equip its youth with the proficiency to become globally competitive.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the motivational function of the teacher in developing the speaking skills of students, there are a number of limitations that must be conceded. First, the research scope was limited to university level students in Punjab Province, Pakistan, which might reduce the generalizability of the findings to other regions or educational contexts. Further studies may investigate similar dynamics in secondary schools or vocational training centers for better comprehension.

The current study relied more on quantitative data from surveys and questionnaires, which may create subjectivity in the analysis. Incorporating qualitative measures could provide a much richer and nuanced assessment in terms of student gain with speaking skills.

Third, some other external factors that might have influenced students’ language learning processes were not considered, such as social class, parental involvement, or regional differences in Pakistan. Further studies should take these variables into consideration to provide a broader understanding of the problems faced by ESL learners.

Last but not least, the investigation dwelled basically on the teacher’s role and left little room for peer interaction, digital tools, or self-directed learning. This could, of course, be extended to these dimensions, too, in order to get even richer insights into this complex process of language acquisition.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ethical review board of University of Gujrat, Pakistan. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MY: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. DE-D: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. BA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YJ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported APC part by Prince Sultan University under the Language and Communication Research Laboratory under Grant RL-CH-2019/9/1 and the Youth Fund Project for Humanities and Social Sciences Research, Ministry of Education, China, under Project 21YJC740022.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abrar, M., Mukminin, A., Habibi, A., Asyrafi, F., and Marzulina, L. (2018). If our English isn’t a language, what is it? Indonesian EFL student teachers’ challenges speaking English. Qual. Rep. 23, 129–145. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2018.3013

Afshar, H. S., and Asakereh, A. (2016). Speaking skills problems encountered by Iranian EFL freshmen and seniors from their own and their English instructors’ perspectives. Electron. J. For. Lang. Teach. 13, 112–130.

Afzaal, M., Shanshan, X., Yan, D., and Younas, M. (2024). Mapping artificial intelligence integration in education: A decade of innovation and impact (2013–2023)—a bibliometric analysis. IEEE Access 12, 113275–113299. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3443313

Agustin, Y. (2015). Kedudukan bahasa Inggris sebagai bahasa pengantar dalam dunia pendidikan. [The position of English as the language of instruction in the world of education]. Deiksis 3, 354–364. Indonesian,

Ahsan, M., Asif, M., and Hussain, Z. (2021). L1 use in english courses ‘a facilitating tool or a language barrier’in L2 teaching/learning at graduation level. Global Lang. Rev. VI, 70–83. doi: 10.31703/glr.2021(VI-I).08

Akram, H., and Abdelrady, A. H. (2023). Application of ClassPoint tool in reducing EFL learners’ test anxiety: An empirical evidence from Saudi Arabia. J. Comp. Educ. 10, 529–547. doi: 10.1007/s40692-023-00265-z

Akram, M., Ahmad, S., Ishaq, G., and Javed, M. (2021). The impact of ESL teachers’ use of demotivational language on students’ learning: A study of ESL learners at secondary level in Pakistan. Commun. Linguist. Stud. 7:44. doi: 10.11648/j.cls.20210703.11

Al Nakhalah, A. M. M. (2016). Problems and difficulties of speaking that encounter English language students at Al Quds Open University. Int. J. Human. Soc. Sci. Invent. 5, 96–101.

Alam, Q., and Bashiruddin, A. (2013). Improving English oral communication skills of Pakistani public school’s students. Int. J. English Lang. Teach. 1, 17–36.

Al-Gahtani, S. S. (2016). Empirical investigation of e-learning acceptance and assimilation: A structural equation model. Appl. Comput. Inform. 12, 27–50. doi: 10.1016/j.aci.2014.09.001

Ali, M. M., Khizar, N. U., Yaqub, H., Afzaal, J., and Shahid, A. (2020). Investigating speaking skills problems of Pakistani learners in ESL context. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. English Literat. 9:62. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.9n.4p.62

Ali, S. (2017). The students’ interest on the use of vocabulary self-collection strategy in learning English vocabulary. Ethic. Ling. J. Lang. Teach. Literat. 4:165. doi: 10.30605/ethicallingua.v4i2.630

Ali, Z., and Ghazali, M. A. I. M. (2016). Learning technical vocabulary through a mobile app: English language teachers’ perspectives. Int. J. Lang. Educ. Appl. Linguist. 4, 27–50. doi: 10.15282/ijleal.v4.487

Alotaibi, T., Almusharraf, N., and Imran, M. (2025). Why some jobs just ‘sound’ male: The Arabic language effect. Cogent Educ. 12:2530160. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2025.2530160

Amoah, S., and Yeboah, J. (2021). The speaking difficulties of Chinese EFL learners and their motivation towards speaking the English language. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 17, 56–69. doi: 10.52462/jlls.4

Ashraf, T. A. (2019). Strategies to overcome speaking anxiety among Saudi EFL learners. Lang. India 19, 202–217.

Asworo, C. W. (2019). The analysis of students’ difficulties in speaking English at the tenth grade of SMK N 2 Purworejo. J. English Educ. Teach. 3, 533–538. doi: 10.33369/jeet.3.4.533-538

Ayesha, A. (2022). “EFL teaching and CALL in higher education in Pakistan,” in English language teaching in Pakistan, eds N. A. Raza and C. Coombe (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 311–327.

Bailey, R. (2005). Evaluating the relationship between physical education, sport and social inclusion. Educ. Rev. 57, 71–90. doi: 10.1080/0013191042000274196

Berdimurotovna, N. D. (2020). The role and place of English in international communication. EPRA Int. J. Res. Dev. 5, 141–144.

Bilal, H. A., Rehman, A., Rashid, A., Adnan, R., and Abbas, M. (2013). Problems in speaking English with L2 learners of rural area schools of Pakistan. Lang. India 13, 1220–1235.

Bozkirli, K. Ç (2019). An analysis of the speaking anxiety of Turkish teacher candidates. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 7, 79–85. doi: 10.11114/jets.v7i4.4060

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles; An interactive approach to language pedagogy, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.

Brown, H. D. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching, 5th Edn. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Canagarajah, S. (2007). Lingua franca English, multilingual communities, and language acquisition. Modern Lang. J. 91, 923–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00678.x

Català-Oltra, L., Martínez-Gras, R., and Penalva-Verdú, C. (2023). The use of languages in digital communication at European Universities in multilingual settings. Int. J. Soc. Culture Lang. 11, 1–15. doi: 10.22034/ijscl.2022.563470.2794

Chand, P., Nand, M., and Lal, N. N. (2022). The importance of speaking skills of youths in English classrooms: A comparative analysis of literature reviews. Education 1, 15–26.

Chaney, A. L., and Burk, T. L. (1998). Teaching oral communication in Grades K-8. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 14, 464–504. doi: 10.1080/10705510701301834

Chin, W. W. (2010). “How to write up and report PLS analyses,” in Handbook of partial least squares, eds V. Esposito Vinzi, W. Chin, J. Henseler, and H. Wang (Berlin: Springer), 655–690.

Choi, J. (2016). English speaking classroom apprehension: A study of the perception held by Hong Kong university language learners. J. Teach. English Specif. Acad. Purpose 4, 293–308.

Clement, R., and Kruidenier, B. G. (1983). Orientations in second language acquisition: The effects of ethnicity, milieu and target language on their emergence. Lang. Learn. 33, 273–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1983.tb00542.x

Cortazzi, M., and Jin, L. (1999). “Cultural mirrors: Materials and methods in the EFL classroom,” in Culture in second language teaching and learning, ed. E. Hinkel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 196–219.

Csizer, K., and Dornyei, Z. (2005). Language learners’ motivational profiles and their motivated learning behavior. Lang. Learn. 55, 613–659. doi: 10.1111/j.0023-8333.2005.00319.x

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language Classroom. Modern Lang. J. 78, 273–284. doi: 10.2307/330107

Dörnyei, Z. (1998). “Demotivation in foreign language learning,” in Paper presented at the TESOL 98 Congress, (Seattle, WA).

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New themes and approaches in second language motivation research. Ann. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 21, 43–59. doi: 10.1017/s0267190501000034

Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. Lang. Learn. 53, 3–32. doi: 10.1111/1467-9922.53222

Dörnyei, Z., and Clément, R. (2001). “Motivational characteristics of learning different target languages: Results of a nationwide survey,” in Motivation and second language acquisition, eds Z. Dörnyei and R. Schmidt (Honolulu, HI: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii), 399–432.

Dörnyei, Z., and Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation, 2nd Edn. England: Pearson Longman.

Dörnyei, Z., and Otto, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working Pap. Appl. Linguist. 4, 43–69.

Fallah, N. (2017). Mindfulness, coping self-efficacy and foreign language anxiety: A mediation analysis. Educ. Psychol. 37, 745–756. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2016.1149549

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitude and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Getie, A. S. (2020). Factors affecting the attitudes of students towards learning English as a foreign language. Cogent Educ. 7:1738184. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2020.1738184

Handayani, S. (2016). Pentingnya kemampuan berbahasa Inggris sebagai dalam menyongsong ASEAN Community 2015. [The importance of English language skills in welcoming the ASEAN Community 2015]. J. Prof. Pendidik 3, 102–106. Indonesian.

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language teaching, 3rd Edn. London: Pearson Education Limited.

Haufiku, I., Mashebe, P., and Abah, J. (2022). Teaching challenges of English second language teachers in senior secondary schools in the ohangwena region, Namibia. Creat. Educ. 13, 1941–1964. doi: 10.4236/ce.2022.136121

Horwitz, E. K. (2016). Factor structure of the foreign language classroom anxiety scale: Comment on Park (2014). Psychol. Rep. 119, 71–76. doi: 10.1177/0033294116653368

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., and Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Lang. J. 70, 125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

Hussain, S. Q., Akhtar, N., Shabbir, N., Aslam, N., and Arshad, S. (2021). Causes and strategies to cope English language speaking anxiety in Pakistani university students. Human. Soc. Sci. Rev. 9, 579–597. doi: 10.18510/hssr.2021.9358

Hussain, I. (2017). Distinction between language acquisition and language learning: A comparative study. J. Literat. Lang. Linguist. 39, 1–5.

Iriance, I. (2018). Bahasa Inggris sebagai bahasa lingua franca dan posisi kemampuan Bahasa Inggris masyarakat Indonesia diantara anggota MEA. [English as a lingua franca and the position of the English language skills of Indonesian people among the members of the MEA]. Prosiding Indust. Res. Workshop Natl. Sem. 9, 776–783. Indonesian.

Jenkins, J. (2019). “English medium in higher education: The role of English as a Lingua Franca,” in Second handbook of english language teaching. (Springer international handbooks of education), 1st Edn, ed. X. Gao (Cham: Springer).

Kadwa, M. S., and Alshenqeeti, H. (2020). The impact of students’ proficiency in English on science courses in a foundation year program. Int. J. Linguist. Literat. Transl. 3, 55–67.

Khurshid, K., Gillani, G., Jabbar, A., and Noureen, S. (2013). A study of the perception of teachers regarding suitable method of teaching English at secondary level. J. Elemen. Educ. 23, 23–40.

Kramsch, C. (2014). Teaching foreign languages in an era of globalization: Introduction. Modern Lang. J. 98, 296–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12057.x

Kurniawan, I. W. A. (2024). English language and its importance as global communication. Int. J. Soc. Stud. 2, 51–57. doi: 10.25078/ijoss.v2i1.3920

Mahmood, M. A., Sattar, A., Imran, M., and Almusharraf, N. (2025). Bridging cultures through explicitation: A corpus-based analysis of bilingual literary translations. Cogent Arts Human. 12:2508210. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2025.2508210

Noels, K. A., Clement, R., and Pelletier, L. G. (2001). Intrinsic, extrinsic, and integrative orientations of French Canadian learners of English. Can. Modern Lang. Rev. 57, 424–442. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.57.3.424

Noor, U., Younas, M., Saleh Aldayel, H., Menhas, R., and Qingyu, X. (2022). Learning behavior, digital platforms for learning and its impact on university student’s motivations and knowledge development. Front. Psychol. 13:933974. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.933974

Oxford, R., and Shearin, J. (1994). Language learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Lang. J. 1, 12–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.1994.tb02011.x

Pennycook, A. (2017). The cultural politics of English as an international language. England: Routledge.

Ramage, K. (1990). Motivational factors and persistence in foreign language study. Lang. Learn. 40, 189–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1990.tb01333.x

Rao, P. S. (2019). The importance of speaking skills in English classrooms. Alford Council Int. English Literat. J. 2, 6–18.

Ringle, C., Da Silva, D., and Bido, D. (2015). Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Braz. J. Market. 13, 56–73.

Rohayati, D. (2018). Analisis strategi pembelajaran bahasa dalam pembelajaran bahasa inggris sebagai bahasa asing. [Analysis of language learning strategies in learning English as a foreign language]. Mimbar Agribisnis J. Pemikiran Masyarakat Ilmiah Berwawasan Agribisnis 1:269. Indonesian, doi: 10.25157/ma.v1i3.47

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Sadeghi, K., and Richards, J. C. (2021). Professional development among English language teachers: Challenges and recommendations for practice. Heliyon 7:e08053. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08053

Sakai, H., and Kikuchi, K. (2009). An analysis of demotivators in the EFL classroom. System 37, 57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2008.09.005

Savignon, S. J. (1991). Communicative language teaching: State of the art. TESOL Quar. 25, 261–275. doi: 10.2307/3587463

Seraj, P. M. I., and Hadina, H. (2021). A systematic overview of issues for developing EFL learners’ oral English communication skills. J. Lang. Educ. 7, 192–204. doi: 10.17323/jle.2021.10737

Seyyed Ali, O. N., and Akram, M. (2015). Vocabulary learning strategies from the bottom-up: A grounded theory. Read. Matrix Int. Online J. 15, 235–251.

She, L., Rasiah, R., Waheed, H., and Pahlevan Sharif, S. (2021). Excessive use of social networking sites and financial well-being among young adults: The mediating role of online compulsive buying. Young Consum. 22, 272–289. doi: 10.1108/YC-11-2020-1252

Suchona, I. J., and Urmy, K. K. (2019). Exploring reading strategies and difficulties among Bangladeshi undergraduates. Shanlax Int. J. English 8, 42–53. doi: 10.34293/english.v8i1.1308

Sutarsyah, C. (2017). An analysis of student’s speaking anxiety and its effect on speaking performance. Indonesian J. English Lang. Teach. Appl. Linguist. 1, 143–152. doi: 10.21093/ijeltal.v1i2.14

Thavabalan, P., Mohan, S., Hariharasudan, A., and Krzywda, J. (2020). English as Business Lingua Franca (BELF) to the managers of indian printing industries. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 22, 549–560. doi: 10.17512/pjms.2020.22.2.36

van Lier, L. (1995). “Vygotskian approaches to second language research,” in Studies in second language acquisition, eds J. P. Lantolf and G. Appel (Norwood, NJ: Ablex). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2021.0351

Wahyuningsih, S., and Afandi, M. (2020). Investigating English speaking problems: Implications for speaking curriculum development in Indonesia. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 9, 967–977. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.9.3.967

Wang, X., Younas, M., Jiang, Y., Imran, M., and Almusharraf, N. (2025). Transforming education through blockchain: A systematic review of applications, projects, and challenges. IEEE Access. 13, 13264–13284.

Williams, M., and Burden, R. (1997). Psychology for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, M. (1994). Motivation in foreign and second language learning: An interactive perspective. Educ. Child Psychol. 11, 77–84.

Yavuzalp, N., and Bahcivan, E. (2021). A structural equation modeling analysis of relationships among university students’ readiness for e-learning, self-regulation skills, satisfaction, and academic achievement. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanced Learn. 16:15. doi: 10.1186/s41039-021-00162-y

Younas, M., Abdel Salam, El-Dakhs, D., and Jiang, Y. (2025a). A comprehensive systematic review of ai-driven approaches to self-directed learning. IEEE Access 13, 38387–38403.

Younas, M., Abdel Salam, El-Dakhs, D., and Jiang, Y. (2025b). Knowledge construction in blended learning and its impact on students’ academic motivation and learning outcomes. Front. Educ. 10:1626609. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1626609

Younas, M., and Dong, Y. (2024). The impact of using animated movies in learning English language vocabulary: An empirical study of lahore. Pakistan. Sage Open 14, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/21582440241258398

Younas, M., Dong, Y., Menhas, R., Li, X., Wang, Y., and Noor, U. (2024a). Alleviating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the physical, psychological health, and wellbeing of students: Coping behavior as a mediator. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 5255–5270. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S441395

Younas, M., Dong, Y., Zhao, G., Menhas, R., Luan, L., and Noor, U. (2024b). Unveiling digital transformation and teaching prowess in english education during COVID-19 with structural equation modelling. Eur. J. Educ. 60:e12818. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12818

Younas, M., Noor, U., Zhou, X., Menhas, R., and Qingyu, X. (2022). COVID-19, students satisfaction about e-learning and academic achievement: Mediating analysis of online influencing factors. Front. Psychol. 13:948061. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.948061

Young, J. E. (1999). Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange.

Yusuf, M. (2022). An analysis of speaking problems in online English presentation during Covid-19 Pandemic. Lingua 18, 1–16. doi: 10.34005/lingua.v18i01.1798

Zaidi, S. B., and Zaki, S. (2017). English language in Pakistan: Expansion and resulting implications. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 5, 52–67. doi: 10.20547/jess0421705104

Zeng, J., and Yang, J. (2024). English language hegemony: Retrospect and prospect. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11:317. doi: 10.1057/s41599-024-02821-z

Zhang, Y. (2009). Reading to speak: Integrating oral communication skills. in english teaching forum. Washington, DC: US Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, Office of English Language Programs.

Zhiping, D., and Paramasivam, S. (2013). Anxiety of speaking English in class among international students in a Malaysian university. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1, 1–16.

Keywords: motivation, English speaking skills, Pakistani university students, teacher roles, structural equation modeling (SEM)

Citation: Younas M, El-Dakhs D, Anwar B and Jinag Y (2025) Motivational role of teachers in developing English speaking skills of Pakistani university students. Front. Educ. 10:1626602. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1626602

Received: 13 May 2025; Accepted: 04 August 2025;

Published: 01 September 2025.

Edited by:

Sereyrath Em, The University of Cambodia, CambodiaReviewed by:

Lourdes Quenta-Condori, Universidad Peruana Unión, PeruRym Asserraji, Moulay Ismail University, Morocco

Copyright © 2025 Younas, El-Dakhs, Anwar and Jinag. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yicun Jinag, amlhbmd5aWN1bkBzenR1LmVkdS5jbg==

Muhammad Younas

Muhammad Younas Dina El-Dakhs

Dina El-Dakhs Behzad Anwar

Behzad Anwar Yicun Jinag3*

Yicun Jinag3*