- Faculty of Education, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy

Introduction: Financial literacy is increasingly recognized as essential for personal and societal well-being, yet its effective integration in primary education remains underexplored. This study examines the application of the European EduFin Framework in evaluating two financial education programs—one based on cooperative learning, the other on game-based learning—in an Italian primary school.

Methods: Employing a case study design, two fifth-grade classes participated in tailored financial education modules. Each session concluded with focus groups, and pupils’ reflections were subjected to qualitative content analysis. Learning outcomes were mapped against the EduFin Framework using convergence and divergence matrices to assess alignment with targeted competences.

Results: Both pedagogical approaches primarily addressed the “Money and Transactions” domain of the EduFin Framework, with limited coverage of “Risk and Reward.” While the framework facilitated systematic evaluation and comparison of program content, findings indicate it emphasizes knowledge transmission over broader competence development, particularly regarding social and collaborative skills.

Discussion: The EduFin Framework offers valuable structure for assessing financial education initiatives but may constrain holistic competence development due to its individualistic focus. However, integrating active, student-centered pedagogies—such as cooperative and game-based learning—can help foster social skills and deeper learning, partially overcoming these limitations.

Conclusion: The study highlights both the utility and constraints of the EduFin Framework in primary education, underscoring the need for pedagogical approaches that balance content mastery with competence and social skill development.

1 Introduction

In recent years, significant attention has been devoted to financial education and the promotion of financial literacy as key strategies for fostering economic growth and equitable access to financial systems (Mancone et al., 2024; Senduk et al., 2024; Sconti et al., 2024). Financial literacy is widely recognized as a critical competence for navigating an increasingly complex social landscape, where financial responsibilities are shifting from governments to individuals (Amagir et al., 2018), and for enhancing personal, social, and economic well-being. Acknowledging the need for systematic involvement on the part of educational institutions, the European Commission introduced the joint EU/OECD Financial Competence Framework for Children and Youth (European Union/OECD, 2023), which aimed to promote the development of financial literacy from primary school onwards.

Despite the framework’s potential, research into its implementation remains limited, particularly its use in schools to foster financial literacy among children and adolescents (Kaiser and Menkhoff, 2020). This lack of research also limits the ability of teachers to adopt effective financial education practices, leaving them without clear guidance on pedagogical strategies or curricular integration, as recently highlighted in this journal by Mancone et al. (2024). Additionally, while evidence indicates that active learning methods are generally more effective than traditional approaches in financial education, few studies have explored how pedagogies can be applied and their impact evaluated. To address these gaps, this paper examines the EduFin Framework and its relevance for evaluation of two primary-level financial education programs. The goal is to offer insights not only into program effectiveness, but also into how such frameworks can support teachers in implementing and evaluating financial education in their classrooms. The programs took as their starting point two student-centered approaches – cooperative learning and game-based learning – which were selected for their potential to foster engagement and promote deep learning.

RQ: To what extent can the EduFin Framework be used to evaluate two financial education programs based on different teaching methods?

The paper begins with a review of the literature on financial education, the EduFin Framework, and relevant pedagogies for financial literacy. It then describes the case study methodology and contextual background, moving on to analyze the delivery of two financial education programs in fifth grade classes, comparing what pupils learned with the EduFin Framework competences. In conclusion, it evaluates the strengths and limitations of the EduFin Framework for assessment of these programs, highlighting both theoretical and practical issues.

2 Literature review

2.1 Financial education

According to the OECD (2019), our societies are currently experiencing what has been termed the Age of Acceleration: a period of profound and rapid change, characterized by the speeding-up of human experience and the need to address increasingly significant social, economic, and environmental challenges. In addition, the transition from defined benefit to defined contribution retirement plans has made individuals – both young and old – responsible for managing their own savings and investments, and for other financial decisions. These choices have become even more complex with the advent of new financial products and recent fluctuations in inflation (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2023).

In this context, citizenship competence, agency, and a sense of responsibility are becoming increasingly important to ensure resilience and adaptability to change (European Union, 2018). Citizenship is no longer perceived as a status that grants rights and duties, but rather as a progression, a path toward the development of active and informed individuals. Education plays an essential role in this by promoting the development of the capabilities necessary to enable all citizens to navigate present and future challenges with a mindful and reflective outlook. As early as 2005, the OECD recognized financial literacy as one of the key competences enabling citizens to make responsible and informed choices in daily life, take sound financial decisions, and achieve individual financial well-being (OECD, 2005). The OECD also contends that financial education should begin in early childhood, as children are immersed in a dynamic social, economic, and financial environment. They should be exposed to money and financial products from a young age, it argues, allowing them to start taking calculated risks and progressively developing responsible decision-making.

Despite the growing interest in promoting financial literacy and broader civic competences, international studies (Lusardi, 2019; OECD, 2023, 2024) suggest that financial literacy – a combination of financial knowledge, behavior, and attitudes – remains low among adults and students worldwide. This is accompanied by shortcomings in daily financial management and a lack of financial resilience, and is also associated with negative financial behaviors, such as debt accumulation, high-cost borrowing, poor mortgage choices, and home foreclosure (Hastings et al., 2013; Klapper et al., 2015; Klapper and Lusardi, 2019). According to the OECD’s international survey on adult financial literacy (2023), on average only 34% of adults in participating countries achieve a decent target score by mastering basic concepts. For students in OECD countries, the average score in the latest PISA survey was 498 points, lower than both the 2018 survey (505 points) and the 2012 survey (500 points). As in previous evaluations, Italy remains below the OECD average, with only 5.1% of students classified as top performers compared to the OECD average of 10.6%, although its 2022 performance represented an improvement on 2012 (OECD, 2024).

Targeting financial education programs at students is beneficial because this group is at a critical stage for understanding fundamental financial concepts and skills, and such programs have the potential to establish a foundation for lifelong financial literacy (Lührmann et al., 2018; Sconti et al., 2024). Evidence-based research suggests that financial education, whether delivered in formal, non-formal, or informal educational settings, is an effective way to increase students’ financial literacy (Kaiser et al., 2020). Financial education programs, however, tend to be more focused on knowledge transmission rather than on the development of broader financial competences, which also include relevant skills and attitudes. Kaiser and Menkhoff (2017, 2020), for example, highlight that many financial education programs prioritize theoretical knowledge over practical application. Another challenge is assessing the development of students’ financial competences, as they have fewer opportunities to make significant financial decisions (Miller et al., 2015).

Regarding the content most frequently covered by financial education programs, Amagir et al. (2018) highlight that the core elements addressed across different educational levels include planning and budgeting, income and careers, saving and investing, spending and credit, and insurance and banking services. At the primary school level, Amagir et al. report a strong focus on the use and function of money, financial planning, saving, spending, and basic credit concepts. Few programs cover investment and banking services. In secondary schools and colleges, the scope of financial education expands to include not only spending, credit, investment, saving, income, and budgeting—all addressed in greater depth—but also banking services, insurance, credit card use, and compulsive spending. This progression appears to be consistent across different countries (Amagir et al., 2018).

2.2 The EduFin framework

Recognizing that financial literacy is an urgent issue for the well-being of citizens across the globe, the OECD released an analytical framework alongside the PISA assessments, identifying key themes in financial education (OECD, 2013). Subsequently, the publication of the Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (EntreComp Framework) in 2016 acknowledged the importance of financial and economic literacy competences for fostering active and engaged citizens in society, for helping individuals to manage their personal and professional lives and transform ideas and opportunities into value for themselves and others (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). The framework breaks down financial literacy, which is defined as the development of financial and economic know-how, into specific learning outcomes and eight proficiency levels, including long-term financial planning and management, decision-making evaluation, and cost estimation. The focus on the development of financial literacy in the context of entrepreneurship, and the creation of a framework based on a progressive and holistic approach, can be considered a precursor to the EduFin Framework.

The introduction of the Council Recommendation on Financial Literacy to support national strategies and the implementation of effective programs (OECD, 2020) led to the publication of the Financial Competence Framework for Children and Youth in the European Union (the EduFin Framework) as part of the OECD-INFE work program (European Union/OECD, 2023). The framework establishes a shared foundation of financial competences for European citizens, spanning different age groups and educational stages. It also facilitates the design, implementation, and evaluation of national financial education strategies in formal, non-formal, and informal contexts, promoting integration into school curricula and the development of teaching materials and tools. Furthermore, the EduFin Framework assists with assessment of financial literacy levels among young Europeans and comparison of educational initiatives across member states.

As explicitly stated in the framework, the overarching goal of financial education is competence development. Competence-based education emphasizes the use of real, complex, and problem-oriented learning situations that promote the integrated development of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Mulder, 2019). Moreover, besides using teaching and learning activities based on problem solving and student-centered didactics, competence-based education requires authentic and engaging assessment tasks (including peer and self-assessment tasks) that stimulate reflection on own learning processes (Baartman et al., 2007). Lastly, competence-based education starts course design from the learning outcomes the students should achieve at the end of the course module. In this regard, competence-based education aligns with course design models that promote a coherence between the intended learning outcomes, the teaching and learning activities, and assessment, such as Bigg’s theory of constructive alignment (Biggs et al., 2022). By integrating these elements, the instructors can foster deep learning in students. This is a mindset where students learn to relate ideas, apply knowledge to new contexts and think critically.

Developing competences is a dynamic and lifelong process, and is influenced by an individual’s personal circumstances, including their values and experiences, and the societal and environmental factors they encounter (Crick, 2008). This is why competence is defined as a combination of knowledge, skills, and attitudes appropriate to the context (European Union, 2018), also known as the K-S-A model. When applied in the context of financial education, the K-S-A model encompasses not only cognitive aspects (such as understanding financial concepts), but also behavioral aspects (applying such concepts in everyday life), and volitional aspects (a willingness to make informed financial decisions). This comprehensive approach ensures that financial literacy is about more than just factual knowledge; it involves the application of that knowledge, the development of practical skills, and the cultivation of positive attitudes toward financial decision-making. By addressing all these dimensions, the K-S-A model provides a well-rounded framework for understanding and fostering financial literacy in a real-world context. Like the key competences for lifelong learning (OECD, 2018), the European Union/OECD (2023) adopts this model to define financial competences, employing specific verbs to categorize them into knowledge/awareness/understanding (e.g., “is aware of,” “knows”), skills/behaviors (e.g., “analyses,” “compares,” “invests”), and attitudes (e.g., “is confident,” “is motivated”). Activities are also tailored by age group, following a spiral approach that progresses from simple to complex concepts. The age groups correspond to educational stages: 6–10 (primary school), 11–15 (secondary school), and 16–18 (upper school).

The general objectives of the EduFin Framework are: to enable learners to effectively manage their financial resources both in the short and long term; to help them make informed and conscious decisions; to assist learners in understanding the economic and financial landscape in which they live; and to prepare them for managing the economic and financial aspects of adult life. The framework identifies four areas: Money and Transactions, Financial Planning and Management, Risk and Reward, and Financial Landscape. Each of these areas is further divided into sub-areas, with specific competences tailored to different age groups. For example, the Money and Transactions area focuses on competences related to money and currency; income; prices, purchases, and payments; and financial documents and contracts. Unlike previous OECD frameworks on financial education, the recent EduFin Framework integrates cross-cutting dimensions to address broader socio-economic contexts. These dimensions are not grouped into separate sections but are horizontally embedded across all areas. For example, digital financial competences address the increasing relevance of technology in financial contexts; sustainable finance competences reflect the importance of environmental and social considerations; citizenship competences foster responsible financial behavior that is aligned with civic values; entrepreneurial competences support innovation and resourcefulness in financial decision-making; and youth transition competences help to prepare young people for adulthood.

Ultimately, the EduFin Framework presents itself as comprehensive and holistic. Recent critics, however, raised concerns about its underlying ideological orientations. Scholars argued that the OECD’s vision of financial education reflects a neoliberal perspective (Capobianco et al., 2018), one that prioritizes market efficiency, personal responsibility, and individual self-regulation (Mazzi et al., 2024). The risk is to turn financial education into a technical exercise focused on individual optimization, overlooking broader societal dimensions such as social justice, environmental sustainability, or the redistributive role of institutions (Das, 2024; Hira, 2016; Mazzi et al., 2024). Despite including transversal competences like sustainability and citizenship, the framework does not sufficiently address how financial decisions are embedded in complex social and economic systems. As a result, the authors suggest rethinking financial education in a way that also fosters critical thinking, civic engagement, and collective responsibility.

2.3 Financial education pedagogies

This section leans on three literature reviews on financial education. Kaiser and Menkhoff (2017) reviewed 126 studies at all educational levels (compulsory plus higher education), and found that financial education impacts behaviors, and, to an even more significant extent, financial literacy. While the field is not as well established as other educational domains, the authors conclude that the effect size of financial literacy is comparable to interventions in other domains. The subsequent review of the same authors (Kaiser and Menkhoff, 2020) focused on compulsory education and analyzed 37 quasi experimental studies. Findings suggest that financial education programs of around 20 to 40 h have an effect comparable to other education programs; such effect size is greater on knowledge (+0.33 Standard Deviations) than on behavior (+ 0.07 SD). The authors also suggest that financial education programs are more effective in primary education than at later stages. Eventually, while the reviews of Kaiser and Menkhoff examine financial education in terms of its mere effectiveness, they pay little attention to the teaching methods adopted in classroom practice. Moreover, these studies seem to contrast behavior and knowledge, while the literature on competence development sees knowledge as a component of competence. The last and most recent contribution of Mancone et al. (2024) is a narrative review of 80 studies in compulsory educational settings. Findings suggest the need for more experiential learning approaches and life-focused contents to improve the effectiveness of financial education, for example through simulations and gaming. Most importantly, this review is more in line with competence-based education and the need to offer student-centered pedagogies (Paniagua and Istance, 2018) to develop not only knowledge, but also skills and attitudes to nurture the students’ competence in a holistic way (Mulder, 2019; Sturing et al., 2011).

Considering this, student-centered pedagogies that actively involve students and aim to develop competence deserve further attention in financial education. Among these, cooperative learning and game-based learning stand out as teaching methods that fall within the six clusters of student-centered and innovative pedagogies (Paniagua and Istance, 2018). These clusters—ranging from experiential learning and blended learning to playful and inquiry-based learning—highlight pedagogical approaches where the teacher acts as a designer of learning environments, fostering motivation, engagement, and deep learning, with a focus on how students are learning. Although the effectiveness of both methods has been extensively studied, as has their impact on the learning of various age groups, research on their use in financial education remains scarce and is predominantly focused on secondary and higher education (Kalmi and Rahko, 2022; Niroo, 2022; Shawver, 2020).

Cooperative learning is a teaching method that focuses on students working together to achieve shared learning objectives. It aims to prepare students for a rapidly changing society by fostering critical thinking, creativity, problem-solving, self-regulation, and social capabilities (De Corte, 2019; Paniagua and Istance, 2018). Johnson and Johnson’s (1989) model, known as Learning Together, outlines five key components for cooperative learning:

• Positive interdependence – each member is connected to others, recognizing that personal success benefits the whole group.

• Individual and group responsibility – each student takes responsibility for their own learning and supports the learning of their peers.

• Constructive interaction – students engage in interactive discussions, questioning reasoning, and giving feedback.

• Social competences – students develop communication and collaborative capabilities through group work.

• Group evaluation – each group reflects on its members’ contributions, highlighting positive actions and areas for improvement (Johnson and Johnson, 1989).

Through these components, cooperative learning fosters active, interconnected, and reflective learning. Inuwa et al. (2017) suggest that existing research is limited but indicate that cooperative learning not only enhances learners’ understanding of complex financial concepts, it also develops their social and decision-making capabilities through group work that involves sharing personal experiences and addressing real-world problems. These methods encourage collaboration and peer learning, offering students the opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge to practical situations, and ultimately improving their financial literacy and decision-making abilities.

Game-based learning uses play as a core element to enhance student engagement and motivation, using experiences of play as powerful learning opportunities to promote intellectual, emotional, and social well-being (Paniagua and Istance, 2018). Rooted in social constructivism, it positions students as active participants, who build their competences through exploration and social interaction and by integrating real-life issues into game-based challenges. This teaching method, although highly dependent on the context and the individuals involved for its effectiveness (Hamari et al., 2014), supports student achievement (Hattie, 2023) and emphasizes inclusion, experimentation, and interconnectedness. In this approach, learning feels like play and occurs through doing; feedback is continuous, failure is viewed as an opportunity for iteration, and challenges remain ever-present (Flatt, 2016). While game-based approaches have been explored in a variety of educational contexts, there is a need to experiment with student-centered pedagogies in financial education to develop both knowledge and skills (Mancone et al., 2024). In this regard, Kalmi and Rahko (2022) demonstrated that play-based financial education is an effective way of developing students’ knowledge. Conversely, Cannistrà et al. (2024) and Sconti et al. (2024) found that there are no significant differences in the effectiveness of game-based and traditional teaching methods.

3 Methodology

The present study deploys case study methodology, which is defined as an in-depth exploration of individual units from multiple perspectives within a real-life context (Schwandt and Gates, 2018). This approach is particularly effective for educational research (Hamilton and Corbett-Whittier, 2012), since it is holistic and evidence-based, and aims to capture the complexity and uniqueness of the phenomena studied, avoiding simplification in order to gain a deeper understanding of the case (Tight, 2022).

The study was conducted in northern Italy in 2024 and involved two fifth-grade classes from a primary school. Two classes (“Class A” and “Class B”) were selected through purposive sampling, based on organizational feasibility and the willingness of the school leadership, teachers, and families to participate. A key selection criterion was the absence of prior exposure to structured financial education programs, to ensure the originality of the intervention. The limited number of participating classes (two classes and 32 pupils in total) reflects the exploratory and context-specific nature of the research design. As such, the goal of this study is an in-depth, situated understanding of how financial education can be approached and experienced in a real classroom setting. In the initial phase, the authors defined the research question and the data collection tool and designed the classroom interventions. Game-based learning was utilized within the financial education program of Class B, testing the educational kit Jun€co – Ethical and Sustainable Economics for Active Citizenship, developed by the Amiotti Foundation1. This kit includes six games to enhance pupils’ financial literacy as well as their active citizenship and ethical economics competences (Amiotti Foundation, 2017). Each session focuses on a specific theme: the underlying factors that determine the costs of goods and services; the value of specialization and exchange; estimating and reflecting on prices and use value; the history of money; loans and interest; and ethical, sustainable, and circular economics. The educational kit incorporates role-playing activities, game boards, flashcards, and puzzles as core learning tools. Each session began with short stories or rhymes to contextualize the subsequent activity, followed by a game-based learning phase and a final stage dedicated to reflecting on and consolidating the experience.

The financial education program for Class A, on the other hand, involved cooperative learning, addressing the same topics as Class B using the Learning Together model. Pupils were divided into heterogeneous groups that remained the same throughout the program. Each session was divided into three phases, with groups receiving an envelope containing all necessary materials for the planned activities. The first phase involved internal organization within the group, role assignment (secretary, timekeeper, professor, scribe), and a review of feedback from the previous meeting. The second phase focused on financial education activities tailored to the specific topic, such as storytelling, mathematical exercises, brainstorming, written reflections, debates, and real-life problem solving. To foster positive interdependence within the groups, each activity was designed to be divided into parts, with each member responsible for completing one section independently—an essential step for the successful completion of the overall task. For example, in one activity, a story was split into four parts, corresponding to the number of group members. Each pupil read the section assigned to them individually, and in the following phase, the group reconvened to summarize the story collaboratively, discuss its content, and respond to specific questions. The third phase was aimed at individual and group assessment, identifying improvements and areas for enhancement.

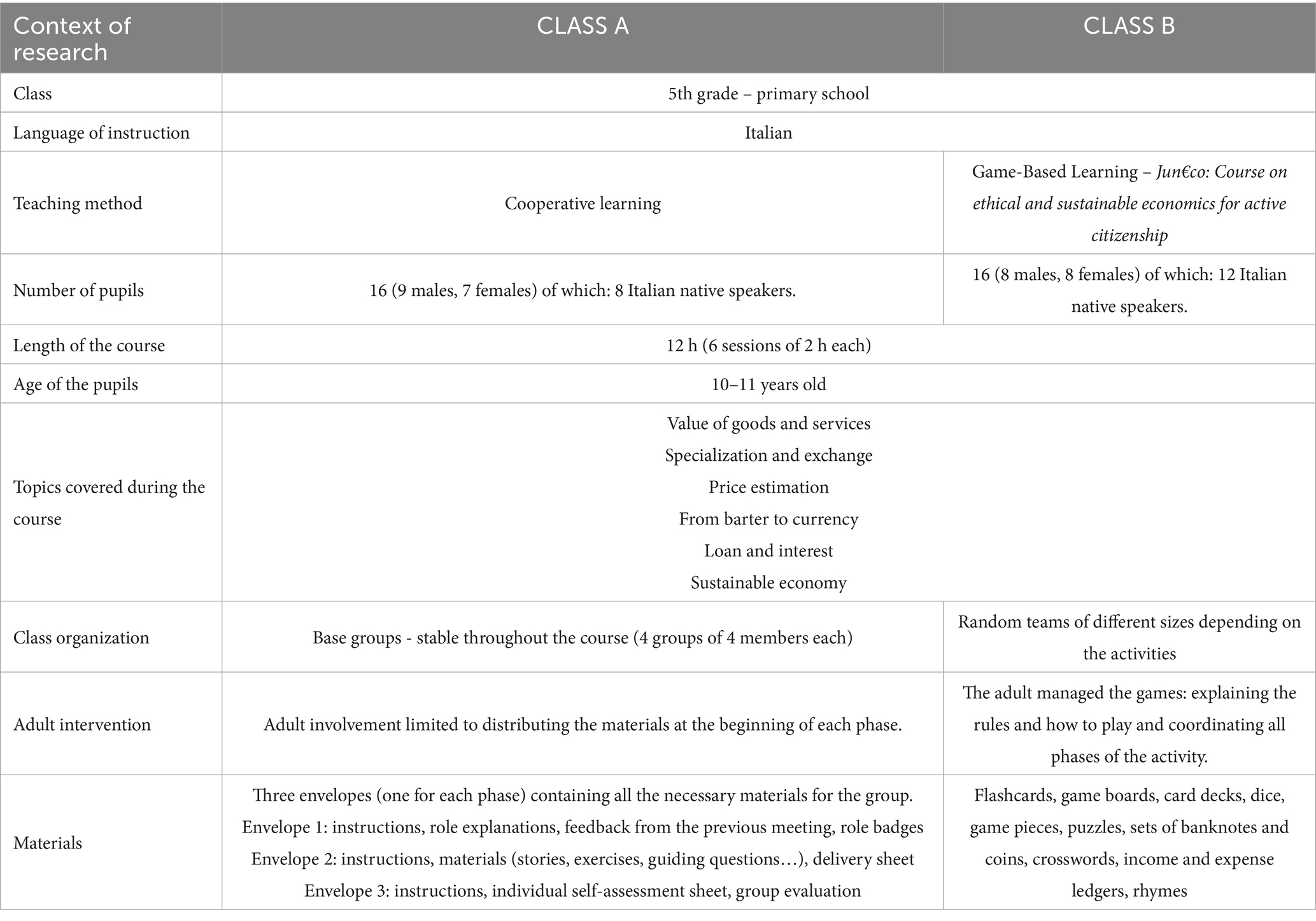

Table 1 summarizes the similarities and differences between the two contexts in which the financial education programs were delivered.

At the end of the sessions in both classes, we conducted focus groups. These provided an opportunity for pupils to reflect on their experiences together and fostered constructive dialogue (Cohen et al., 2018). The prompt questions for the discussions encouraged pupils to think about what they had learned during each session. Since the focus groups were semi-structured, pupils also had the opportunity to guide the discussion toward the topics, opinions, and concerns they considered most significant, while maintaining a focus on their learning. Each focus group was recorded, and all the interventions accurately transcribed.

The focus group discussions were subjected to qualitative content analysis, which provided a flexible and systematic way to examine emerging patterns. This approach involves developing a coding framework and systematically reducing the data by coding units that align, adjusting the framework as needed throughout the analysis process in response to the data (Schreier, 2012). Starting with the focus group transcripts, all spoken interventions were categorized to identify specific content-related themes. The analysis was structured by first defining broader macro-categories to establish key conceptual domains. These macro-categories were then broken down into specific thematic categories, allowing for more detailed and nuanced interpretation of the data.

Based on this analysis, convergence and divergence matrices were created for each class to highlight the connections and overlaps with the areas and subareas of the Edufin Framework, and to identify discrepancies and gaps in the financial education programs offered to the classes. A content analysis of the framework was conducted, in line with the approach outlined by Deregözü (2022) and Ergünay and Parsons (2023), to systematically categorize its contents. Initially, the first author conducted a detailed analysis of all the EduFin Framework competences for the 6–10 age group (primary level), identifying a set of keywords for each area and subcategory. The EduFin Framework was thus turned into a coding framework, to allow for comparison with the data from the focus groups. Then, the first author reviewed the categories emerging from the focus groups and compared them against the coding framework and the associated keyword sets. After completing this process for all categories and for each class, the researchers collaboratively reviewed the results, discussed discrepancies, and finalized the convergence and divergence matrices to establish intersubjective consensus (Denzin et al., 2023; Ravitch and Carl, 2020).

This section deals with the quality and rigor of the data analysis. We ensured transferability—the extent to which readers can determine whether the results apply to other contexts (Johnson et al., 2020)—with Table 1, which provides detailed contextual information about the research setting. Dependability, referring to the stability and coherence of the research process over time (Ravitch and Carl, 2020), was ensured by clearly describing the procedures used for data collection and the analytic steps followed. Regarding confirmability, we strived to ensure that the findings were grounded in the participants’ contributions rather than shaped by researcher bias (Johnson et al., 2020). While acknowledging the subjective nature of qualitative inquiry, we engaged in collaborative reflection and ongoing comparison among researchers to promote transparency and minimize interpretive bias. Descriptive validity, defined as the clarity and accuracy of descriptions and interpretations (Ravitch and Carl, 2020), was achieved through collaboration and systematic verification among researchers, with close reference to the original transcripts. Each thematic category was supported by direct quotations from the focus groups, grounding our interpretations in concrete data. Finally, we addressed interpretative validity, concerning the credibility and coherence of data interpretations (ibid.), through a bottom-up coding process that involved multiple readings of the transcripts for developing the coding frame, followed by collaborative review and discussion. Similarly, we built the convergence/divergence matrices ensuring consistency through independent analyses followed by joint discussions.

4 Results

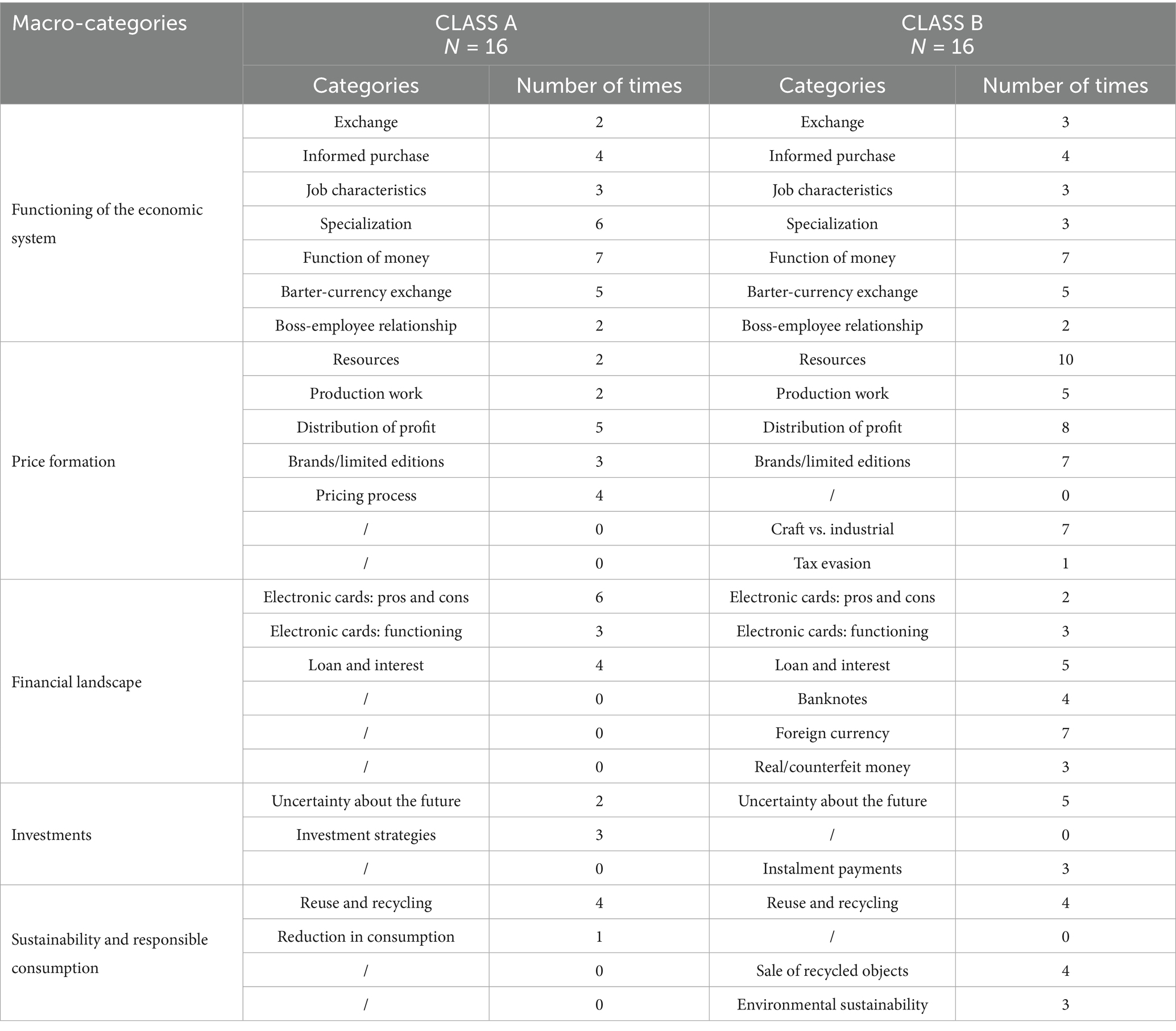

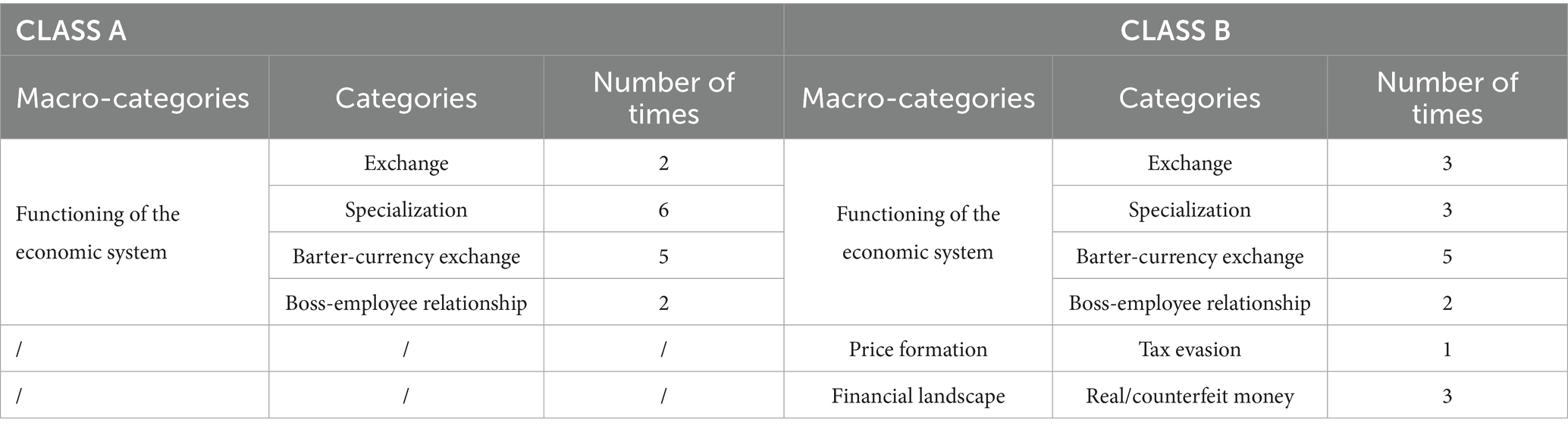

Table 2 shows the macro-categories and categories that emerged from the qualitative content analysis of the focus groups conducted in the two classes. The number of times there was discussion of each category is shown in absolute numbers.

Table 2 shows that all the content discussed by the focus groups fell into five macro-categories, each of which has been further divided into more specific categories. For the ‘Functioning of the Economic System’ macro-area, the categories that emerged were the same for both classes. For example, in the category ‘Specialization’, one pupil grasped the concept by stating, “the economic system is like a chain: you cannot do everything by yourself, but you need someone else,” highlighting the interdependent nature of economic activities. Pupils also recognized the challenges of barter systems. One noted, “bartering causes a lot of arguments! Even at school when we trade Pokémon cards, we always end up arguing!” Building on this, another pupil explained the evolution towards more advanced forms of payment: “that’s why money was invented. Then came debit cards, and then bitcoins…” Regarding the ‘Boss-employee relationship’, a student asked an insightful question: “If I spend €100 in a store and there are five workers, how does that work? Does the bank transfer €20 to each worker’s account? Because €100 divided by five is €20 each.” Another pupil responded by clarifying the economic reality: “It does not work like that! The boss takes everything. And it’s not even €100 profit, because there’s material costs, taxes, transportation… After subtracting these expenses, there’s some money left, and the boss pays the workers’ salaries. But those are lower than what the boss earns… He tries to earn as much as possible!.”

For the ‘Price Formation’ macro-area, discussions varied between classes. In Class A, pupils reflected on the ‘Pricing Process’, noting, “it’s a bit difficult to choose the price… because the shopkeeper sells something, but usually does not produce it, unless they are a craftsman. So, they have to buy it from the producer and then resell it at a higher price!” Meanwhile, in Class B, students focused on topics like ‘Craft vs. Industrial’ and ‘Tax Evasion’. One pupil shared an experience, “Sometimes in a shop they do not give you a receipt but give you a discount… So, you pay less for your backpack than its actual price because there are no taxes.” Within the ‘Financial Landscape’ macro-area, the categories ‘Banknotes’, ‘Real vs. Counterfeit Money’, and ‘Foreign Currency’ emerged only in Class B. For example, one student emphasized, “the texture of real banknotes is different from regular paper. They also have a strip in the middle that you can see if you hold it up to the window.” In the ‘Investments’ macro-area, Class B pupils talked about ‘Instalment Payments’, while Class A students discussed ‘Investment Strategies’. One student remarked, “In the end, saving is very important. If you spend everything you earn, you will not have money for your future, for your projects… But if you put something aside every time you earn, overtime you can invest. Or you can handle unexpected expenses.” Finally, in the ‘Sustainability and Responsible Consumption’ macro-area, pupils in Class A talked about ‘Reduction in Consumption’, with one sharing, “it’s true that we buy too much… If I think about clothes… We could buy much less and just keep a t-shirt a bit longer even if it’s a bit worn out.” Meanwhile, Class B addressed topics like ‘Sale of Recycled Objects’ and ‘Environmental Sustainability.’

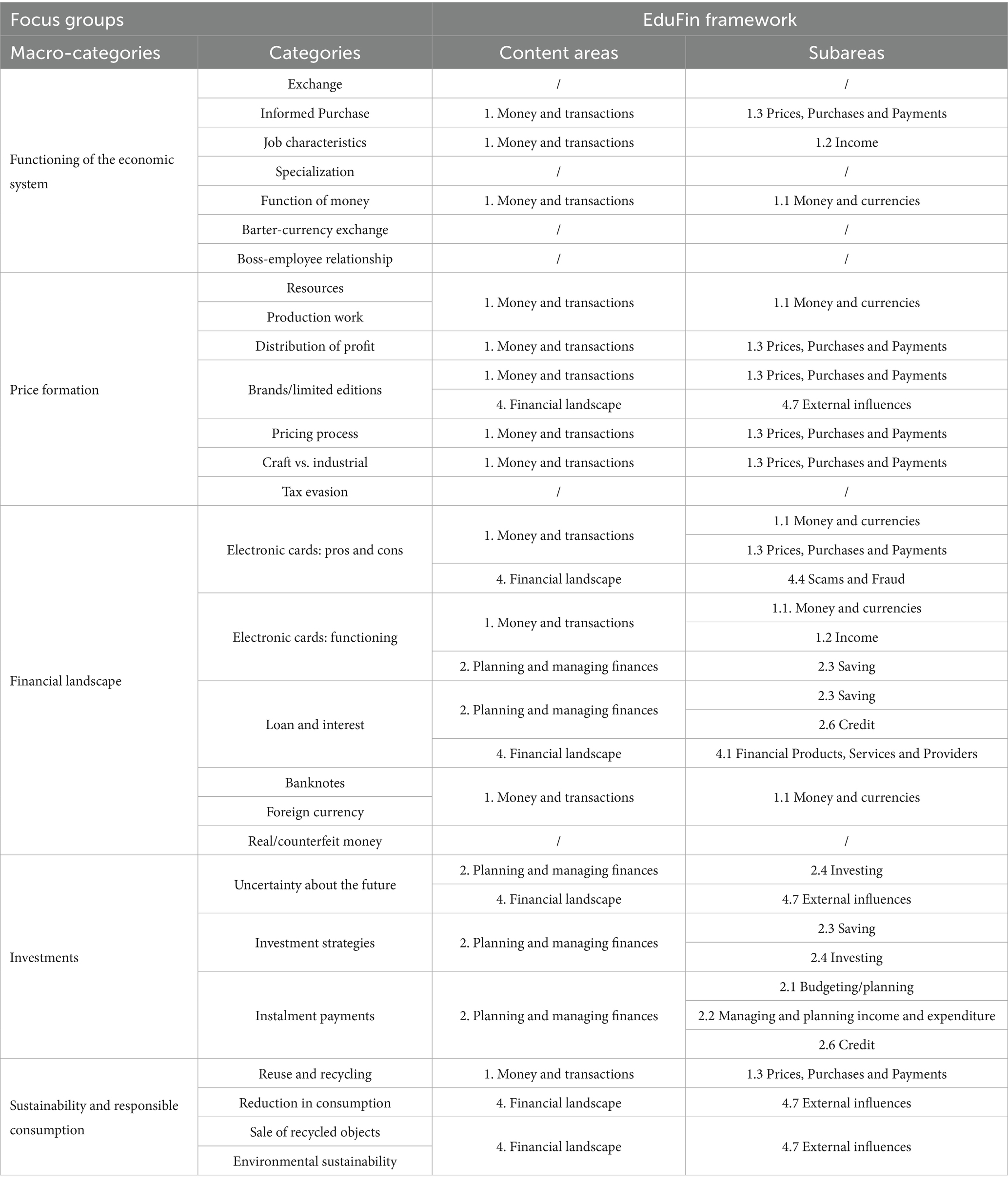

Table 3 shows the convergence matrix. It represents the comparison between the macro-categories and categories that emerged from the focus groups conducted in both classes, and the content areas and subareas of the Edufin Framework.

Table 3 shows that almost all the categories that emerged from the focus groups can be matched with the Edufin Framework, and that most convergences relate to the first area of the framework, i.e., Money and Transactions. However, there is also a convergence with the third area (Risk and Reward), as well as some convergences with area 4 (Financial Landscape).

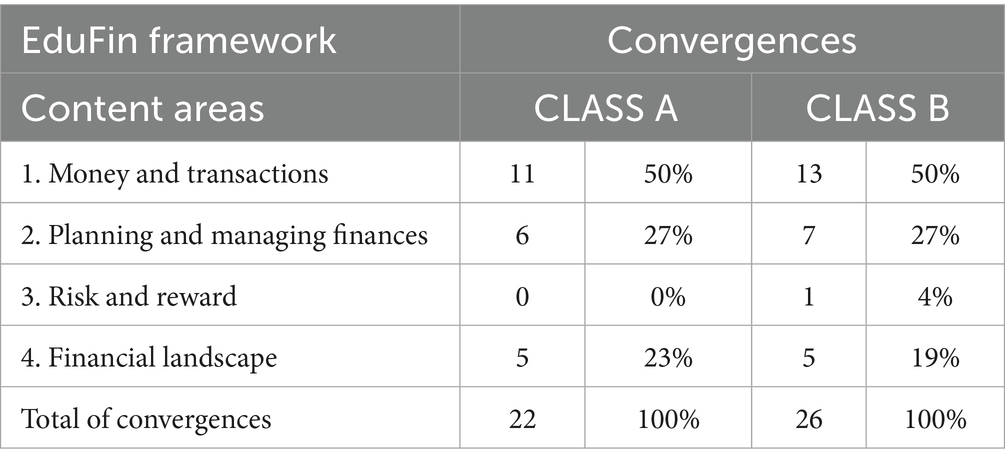

Table 4 illustrates the distribution of convergences between the two programs (Class A and Class B) and the four content areas of the EduFin Framework. Convergences are given in both absolute numbers and percentages, revealing how they are spread across the four content areas. This allows for evaluation of whether key areas of the framework were missing from the programs.

Table 4 shows that both financial education programs placed a stronger emphasis on the ‘Money and Transactions’ content area, which represents 50% of total convergences across the two classes. The second content area, ‘Planning and Managing Finances’, follows with approximately 27% in each class. The third area, ‘Risk and Reward’, was scarcely addressed—emerging only once in Class B—and the fourth area, ‘Financial Landscape’, appeared in just over 20% of cases. These findings confirm that the programs focused primarily on foundational financial concepts, while more complex or systemic dimensions were addressed less frequently. Although the framework includes competences across all four areas at the primary level, this distribution is consistent with existing literature, which indicates that financial education programs in primary schools tend to focus predominantly on the themes covered in the first area. This reflects the foundational nature of these concepts and their perceived relevance for younger students. However, the presence of convergences in the other areas, albeit limited, suggests that pupils are capable of engaging with more advanced or systemic financial topics when appropriately guided.

Table 5 highlights some topics emerging from the focus groups that are not referred to explicitly in the EduFin Framework. The number of times each category was discussed in the focus groups is given in absolute numbers.

Both classes reflected on exchange and the specialization of economic sectors, which are essential for the functioning of the economic system. The transition from bartering to paper money and electronic currency, and the relationship between employers and employees, were also discussed. In Class B, the freedom allowed in the focus groups led pupils to reflect on tax evasion and the recognition of real versus counterfeit banknotes. Although these categories emerged several times, none of them converged with the content areas and sub-areas of the EduFin Framework for the primary school level.

5 Discussion

Analysis of the focus groups’ discussion of financial content, combined with the construction of convergence and divergence matrices, suggest that both programs placed a strong emphasis on the first area of the EduFin Framework (Money and Transactions), while the other areas (Planning and Managing Finances; Risk and Reward; Financial Landscape) were given comparatively little attention. As shown in Table 4, 50% of the identified convergences were concentrated in the first content area of the framework, with a predominant focus on fundamental financial concepts, including money, payment methods, pricing, transactions, and income. This distribution invites reflection on the relevance of each area to the objectives of financial education at the primary school level.

Although Kaiser and Menkhoff (2020) highlight a lack of systematic information in the literature on curriculum content, this strong emphasis on the first area of the EduFin Framework in both programs reflects the work of Amagir et al. (2018). Their study found that, in a range of countries, financial education programs for primary schools primarily cover topics such as different forms of money, its role and functions, payment methods, pricing of goods and services, saving and budgeting, and tracking income and expenses. These topics are considered prerequisites for understanding more complex financial concepts and fall predominantly within the first area of the EduFin Framework, with some extending into the second. In contrast, this study found, the third and fourth areas were given minimal attention. It is our view that as students progress to higher levels of education, they should gradually develop competences relating to savings management, long-term financial planning, risk diversification, and investment, and also gain a deeper understanding of the diverse financial instruments available. These competences fall within the third and fourth areas of the EduFin Framework. Research indicates that such competences are essential yet remain largely underdeveloped (Klapper et al., 2015; Lusardi, 2019). Although the EduFin Framework explicitly structures each content area as a vertical progression by age group, demonstrating that each financial topic can be introduced at primary school level, our findings suggest that the framework’s content areas should be viewed as progressive, as they clearly increase in depth and complexity over time. Consequently, the first content area serves as a crucial prerequisite for more complex topics from the other areas of the framework. It will not be possible to introduce financial education programs in primary schools that focus on financial products and insurance if pupils have not first acquired foundational competences regarding the use, value, and forms of money, as well as payment methods. We believe that the most effective way to introduce financial education at primary school level is to start with fundamental concepts from the first area of the EduFin Framework and progressively build through the other content areas.

The analysis shown in Table 5 of the divergences between the two financial education programs and the EduFin Framework suggest that certain categories addressed in the focus groups are not reflected in the framework. Both programs enabled pupils to develop a broad understanding of how the economic system functions, demonstrating comprehension of concepts such as exchange, specialization, the transition from barter to currency, and the dynamics between employers and employees. For example, the pupils emphasized that “each economic sector needs the others,” and that “every worker is specialized in something and depends on others.” As one student pointed out, “if something goes wrong in one area, it can affect other jobs. For example, if a hotel starts having fewer customers, it also affects the cleaning staff, the cooks, the waiters, the lifeguards….” Additionally, in one of the classes, pupils explored topics such as tax evasion and the analysis of genuine versus counterfeit banknotes. One pupil, for example, noted that “real banknotes have glittery silver numbers,” showing an awareness of security features and the importance of identifying authentic currency. In our view, these areas that are missing from the framework are essential, as they represent key dimensions for understanding the wider financial system.

The absence of a broader vision of society and the economic system—where specialized sectors interact and intersect—is, in our view, a noteworthy omission from the EduFin Framework, albeit consistent with the literature on the subject (Mazzi et al., 2024). While the primary objective of financial education is to enable individuals to develop the competences necessary for financial literacy and the capability to manage their personal finances (OECD, 2005, 2013), this focus tends to reduce financial education to a matter of individual responsibility, thus overlooking a broader vision of financial education as a tool for reducing inequalities in society, while simultaneously promoting equity and greater inclusion. Such a reductionist approach may reflect deeper ideological underpinnings, as it aligns with a wider neoliberal agenda in the OECD educational policies (Capobianco et al., 2018), where financial literacy is promoted as a means of self-regulation and individual empowerment, often detached from a critical understanding of systemic injustice and economic power relations (Das, 2024; Hira, 2016). In such frameworks, financial failure—such as debt or financial insecurity—is often implicitly attributed to poor individual choices, rather than being situated within broader socio-economic contexts such as precariousness, inequality, or lack of access to resources. Consequently, key educational aims such as environmental sustainability, social justice, and collective well-being remain marginal. Under this approach, financial education risks becoming a tool for reinforcing a market-centric approach —focused on efficiency, growth, and competition—rather than fostering critical financial citizenship oriented toward democratic participation and equitable resource distribution. A growing body of scholars (Das, 2024; Mazzi et al., 2024) argue for redefinition of financial education to embrace complexity and promote inclusiveness and social justice.

Finally, this analysis suggests that, although the goal of the EduFin Framework is to develop students’ financial literacy from primary to upper school (European Union/OECD, 2023), it tends to prioritize a knowledge-oriented approach. In theory the framework adopts the K-S-A model, which integrates knowledge, skills, and attitudes into a holistic view of competences, employing a taxonomy of verbs intended to promote deep learning and support the progressive development of competences across the four content areas. In practice, however, most of the areas cited for the 6–10 age group targeted knowledge. At the primary school level, the most frequently used verbs in the framework are ‘understands’, ‘is aware’, ‘knows’, and ‘differentiates’. We would contend that these verbs are a clear indicator of a shift from a competence-based approach to a predominantly knowledge-based approach. This reflects the conclusions of Kaiser and Menkhoff (2017, 2020), who argue that financial education often emphasizes the transmission of knowledge rather than the development of practical skills and approaches. In this sense, the use of verbs that stress understanding and awareness rather than application and internalization of competences reflects a more theoretical approach (Biggs et al., 2022). This limitation may make financial education less effective by reducing opportunities for students to develop practical skills and responsible financial behaviors. From this perspective, the framework fails to foster deep learning (Biggs et al., 2022), which emphasizes students’ active engagement, critical and relational thinking, and the ability to transfer competences to real-world contexts. Deep learning contrasts with surface learning by promoting meaning-making, long-term retention, and the application of knowledge to novel and complex situations. This is why student-centered pedagogies where learners engage in activities such as the ones tested in this article (rather than lectures that focus on knowledge transmission), are key to developing competences (Paniagua and Istance, 2018). Such pedagogies are more likely to support both deep learning and the development of transferable financial competences, thus better preparing students for complex financial decision-making in everyday life.

6 Conclusion

Our study contributes to a better understanding of the use of the European EduFin Framework. The framework serves a dual purpose, as a tool for designing financial education programs that aim to develop financial literacy from primary to secondary school, and as an instrument for assessing the effectiveness of such programs. The present study focuses specifically on the latter aspect, exploring the extent to which the EduFin Framework can be used as a tool for evaluating financial education programs delivered in schools, and highlighting both challenges and opportunities for financial education practitioners. The research question guiding this study was: “To what extent can the EduFin Framework be used to evaluate two financial education programs based on different teaching methods?”

Our findings demonstrate that the EduFin Framework (European Union/OECD, 2023) is a valuable tool for assessing the content of primary school programs. Qualitative analysis, supported by the construction of convergence and divergence matrices, allowed us to identify key points of alignment between the two programs and the framework. This process confirmed that both programs focused primarily on the first content area of the framework. This aligns with existing literature (Amagir et al., 2018), which emphasizes the need to build foundational competences—such as understanding the use, value and forms of money, income, spending, and payment methods—before introducing more complex concepts like risk, investment, or diversification. Although the EduFin Framework is structured vertically across all school levels, our findings suggest that primary education must focus on the first area as a pedagogical priority. A progressive approach is therefore essential to ensure that students develop a solid foundation before gradually expanding their knowledge to encompass the more advanced areas of the framework.

Our study also finds that at primary level, the EduFin Framework tends to adopt an individualistic approach, focusing on individual financial well-being, without taking account of macroeconomic themes. This narrow focus risks reducing financial education to a technical exercise, rather than a means to promote social justice, equity, and citizenship. Integrating civic dimensions into financial education can help students understand how individual financial choices impact collective well-being and the broader economic system. To address these gaps, our findings suggest that student-centered pedagogies—such as cooperative and game-based learning— can help bridge this gap by shaping not only what students learn but also how they engage with financial concepts. These pedagogies create a collaborative and participatory learning environment that fosters social competences, negotiation abilities, and collective responsibility (Hattie, 2023; Paniagua and Istance, 2018). By working together in heterogeneous groups and making joint financial decisions, pupils can explore how the choices of an individual can influence the choices of others and how economic dynamics are inherently linked to the broader financial and social system. Similarly, game-based learning requires pupils to manage collective resources, face challenges, and make economic decisions, experiencing the consequences of those decisions at first hand. These approaches do more than just enrich the learning experience—they shift the focus from an individualistic view of financial education to a more collective and system-based perspective. In doing so, they help pupils develop a more nuanced understanding of economic and social interdependencies, reinforcing the idea that financial education is not only about personal financial management but also about participating in and understanding the broader economic landscape.

Finally, the results show that, although the EduFin Framework formally adopts a competence-based approach, providing a holistic view of competences (Crick, 2008; OECD, 2018), in practice it favors a transmissive model where knowledge prevails over the other components. The focus of the four content areas is on students’ acquisition of facts and information, rather than their engagement with hands-on activities which would foster competence development. Consequently, while students may gain theoretical knowledge, they may not have sufficient opportunities to integrate it into real-life contexts alongside critical thinking, problem solving, and responsible financial decision-making. In this sense, the framework would benefit from a greater alignment with pedagogical principles that foster deep learning (Biggs et al., 2022), where students connect ideas, reflect on their experiences, and transfer knowledge to novel and meaningful contexts. By fostering competences, educators can offer students a comprehensive and truly effective financial education, one that prepares them not only to understand economic concepts but also to use this understanding to navigate the economic and social challenges of both the present and the future.

By demonstrating that the EduFin Framework can serve as a guiding reference for assessing financial education programs, this paper contributes to the literature on financial education and student-centered pedagogies. Findings are relevant for both researchers and financial educators, because they offer insights into the practical delivery of financial education programs in primary schools, and the use of the EduFin Framework to evaluate them. At the same time, this analysis highlights areas where the framework may be enhanced to reflect the educational and societal challenges of today.

The EduFin Framework would benefit from the explicit inclusion of civic, ethical, and systemic dimensions of financial education. First, the framework could integrate topics such as tax evasion, counterfeiting, and the social value of taxation for collective well-being as age-appropriate learning outcomes. Second, the framework could reduce its strong emphasis on individual responsibility—both for financial success and debt—in favor of a more realistic understanding of the economic system as shaped by structural forces and interdependencies. Third, the framework could provide clearer guidance on how to embed real-life socio-economic issues into educational practices—for example, by connecting financial decision-making to topics such as environmental sustainability, redistributive justice, and social cohesion.

Regarding the limitations and future perspectives related to this study, our research was initially conducted with primary school pupils, specifically 5th graders, thus excluding lower and upper secondary students. Future studies could encompass a wider range of settings, including participants of different ages and from various school types, exploring other parts of the framework and not only that of primary school pupils. Secondly, our experiment, as an exploratory case study, involved a small number of pupils. Additionally, the selection of the participating classes was determined by the availability and willingness of school leadership, teachers, and families, rather than random assignment. This further limits the transferability of the findings to broader educational contexts. Thirdly, the data we gathered was purely qualitative and obtained from focus groups at the end of each learning session; our findings are based only on pupils’ reflections and self-evaluations. Future studies could involve other data collection tools, both qualitative and quantitative, such as performance rubrics and classroom observations to offer triangulation. Finally, future studies could place greater emphasis on the cognitive processes activated by students during the learning process, valuing not only the financial aspects but also the transversal competences developed during active learning experiences, such as social abilities, creativity, and problem-solving.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Participants' legal guardians provided written informed consent to participate in this study, following the school’s standard procedure for parental consent. The research strictly adhered to the ethical guidelines established by Italian and European regulations for educational research, ensuring respect for participants' rights, privacy, and well-being throughout the study.

Author contributions

GA: Visualization, Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. DM: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. MP: Project administration, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sarah Rimmington and Richard Hough for their valuable assistance with proofreading.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1628635/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Amagir, A., Groot, W., Maassen van den Brink, H., and Wilschut, A. (2018). A review of financial-literacy education programs for children and adolescents. Citizenship Soc. Econ, Educ. 17, 56–80. doi: 10.1177/2047173417719555

Amiotti Foundation (2017). Jun€co. Corso di economia etica e sostenibile per la cittadinanza attiva. Per gli alunni delle classi 4° e 5° della scuola primaria. Milan: Fabbrica dei Segni.

Baartman, L. K., Bastiaens, T. J., Kirschner, P. A., and Van der Vleuten, C. P. (2007). Evaluating assessment quality in competence-based education: a qualitative comparison of two frameworks. Educ. Res. Rev. 2, 114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2007.06.001

Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., and Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The entrepreneurship competence framework, vol. 10. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

Biggs, J., Tang, C., and Kennedy, G. (2022). Teaching for quality learning at university 5e. London: McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Cannistrà, M., De Beckker, K., Agasisti, T., Amagir, A., Põder, K., Vartiak, L., et al. (2024). The impact of an online game-based financial education course: multi-country experimental evidence. J. Comp. Econ. 52, 825–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2024.08.001

Capobianco, R., Mayo, P., and Vittoria, P. (2018). Educare alla cittadinanza globale in tempi di neoliberalismo. Riflessioni critiche sulle politiche educative in campo europeo. Lifelong Lifewide Learning 14, 34–50. doi: 10.19241/lll.v15i32.124

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. 8th Edn. London: Routledge.

Crick, R. D. (2008). Key competencies for education in a European context: narratives of accountability or care. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 7, 311–318. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2008.7.3.311

Das, S. (2024). Financial literacy and education in enhancing financial inclusion and poverty alleviation. N. Mansour et al. (eds), E-financial strategies for advancing sustainable development: Fostering financial inclusion and alleviating poverty (127–144).Sustainable Finance. Springer, Cham

De Corte, E. (2019). Learning design: creating powerful learning environments for self- regulation skills. Вопросы образования 4, 30–46. doi: 10.17323/1814-9545-2019-4-30-46

Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S., Giardina, M. D., and Cannella, G. S. (2023). The sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications.

Deregözü, A. (2022). Foreign language teacher competences: a systematic review of competency frameworks. Ankara Univ. J. Facult. Educ. Sci. 55, 219–237. doi: 10.30964/auebfd.762175

Ergünay, O., and Parsons, S. A. (2023). A comparison of teacher competence frameworks in the USA and Türkiye. J. Int. Soc. Teacher Educ. 27, 45–67. doi: 10.26522/jiste.v27i1.4165

European Union (2018) Council recommendation of 22 may 2018 on key competences for lifelong learning. Official journal of the European Union. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018H0604(01)#:~:text=The%20Reference%20Framework%20sets%20out,social%20and%20learning%20to%20learn (Accessed April 28, 2025).

European Union/OECD (2023). Financial competence framework for children and youth in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Flatt, R. (2016). Revolutionising schools with design thinking and game-like learning. New York City: Debates in Education, Institute of Play.

Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., and Sarsa, H. (2014). “Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification,” in 2014 47th Hawaii international conference on system sciences. Piscataway, NJ, United States: IEEE - Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 3025–3034.

Hamilton, L., and Corbett-Whittier, C. (2012). Using case study in education research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hastings, J. S., Madrian, B. C., and Skimmyhorn, W. L. (2013). Financial literacy, financial education, and economic outcomes. Annu. Rev. Econ. 5, 347–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-082312-125807

Hattie, J. (2023). Visible learning: The sequel: A synthesis of over 2,100 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Abingdon: Routledge.

Hira, T. K. (2016). “Financial sustainability and personal finance education,” in Handbook of consumer finance research (2nd ed.). ed. J. J. Xiao (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG), p. 356–366.

Inuwa, U., Abdullah, Z., and Hassan, H. (2017). Assessing the effect of cooperative learning on financial accounting achievement among secondary school students. Int. J. Instr. 10, 31–46. doi: 10.12973/iji.2017.1033a

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., and Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 84:7120. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7120

Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooperation and competition: Theory and research. Minneapolis: Interaction Book Company.

Kaiser, T., Lusardi, A., Menkhoff, L., and Urban, C. (2020). Financial education affects financial knowledge and downstream behaviors. J. Financ. Econ. 145, 255–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.09.022

Kaiser, T., and Menkhoff, L. (2017). Does financial education impact financial literacy and financial behavior, and if so, when? World Bank Econ. Rev. 31, 611–630. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhx018

Kaiser, T., and Menkhoff, L. (2020). Financial education in schools: a meta-analysis of experimental studies. Econ. Educ. Rev. 78:101930. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.101930

Kalmi, P., and Rahko, J. (2022). The effects of game-based financial education: new survey evidence from lower-secondary school students in Finland. J. Econ. Educ. 53, 109–125. doi: 10.1080/00220485.2022.2038320

Klapper, L., and Lusardi, A. (2019). Financial literacy and financial resilience: evidence from around the world. Financ. Manage. 49, 589–614. doi: 10.1111/fima.12283

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., and Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). “World Bank” in Financial literacy around the world, vol. 2 (Washington DC), 218–237.

Lührmann, M., Serra-Garcia, M., and Winter, J. (2018). The impact of financial education on adolescents’ intertemporal choices. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 10, 309–332. doi: 10.1257/pol.20170012

Lusardi, A. (2019). Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 155, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Lusardi, A., and Mitchell, O. S. (2023). The importance of financial literacy: opening a new field. J. Econ. Perspect. 37, 137–154. doi: 10.1257/jep.37.4.137

Mancone, S., Tosti, B., Corrado, S., Spica, G., Zanon, A., and Diotaiuti, P. (2024). Youth, money, and behavior: the impact of financial literacy programs. Front. Educ. 9:1397060. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1397060

Mazzi, L. C., Hartmann, A. L. B., and Pessoa, C. A. D. S. (2024). Financial education and social justice: reflections within the scope of mathematics education. Bolema 38:e240044. doi: 10.1590/1980-4415v38a2400441

Miller, M., Reichelstein, J., Salas, C., and Zia, B. (2015). Can you help someone become financially capable? A meta-analysis of the literature. World Bank Res. Obs. 30, 220–246. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkv009

Mulder, M. (2019). “Foundations of competence-based vocational education and training,” in Handbook of vocational education and training. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 1–26.

Niroo, M. (2022). Exploring the relationship between cooperative learning and financial literacy of students. Open Access J. Resistive Econ. 10, 77–87. doi: 10.22034/oajre.2024.469630.1091

OECD (2005). Recommendation on principles and good practices for financial education and awareness. Paris: OECD Council.

OECD (2013). PISA 2012 assessment and analytical framework: Mathematics, reading, science, problem solving and financial literacy. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019). An OECD learning framework 2030. The Future of Education and Labor. Paris: OECD Publishing, 23–35.

OECD. (2020). Council recommendation on financial literacy. OECD/LEGAL/0461. Available online at: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0461 (Accessed April 28, 2025).

OECD (2023). OECD/INFE 2023 international survey of adult financial literacy. OECD business and finance policy papers, no. 39. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2024). PISA 2022 results (volume IV): How financially smart are students? Paris: OECD Publishing.

Paniagua, A., and Istance, D. (2018). Teachers as designers of learning environments: The importance of innovative pedagogies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Ravitch, S. M., and Carl, N. M. (2020). Qualitative research: Bridging the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological. 2ª Edn. London: Sage.

Schwandt, T. A., and Gates, E. F. (2018). “Case study methodology” in The sage handbook of qualitative research. Fifth ed (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC, Melbourne: Sage), 341–358.

Sconti, A., Caserta, M., and Ferrante, L. (2024). Gen Z and financial education: evidence from a randomized control trial in the south of Italy. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 112:102256. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2024.102256

Senduk, F. F. W., Djatmika, E. T., Wahyono, H., Churiyah, M., Mahasneh, O., and Arjanto, P. (2024). Fostering financially savvy generations: the intersection of financial education, digital financial misconception and parental wellbeing. Front. Educ. 9:1460374. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1460374

Shawver, T. J. (2020). An experimental study of cooperative learning in advanced financial accounting courses. Account. Educ. 29, 247–262. doi: 10.1080/09639284.2020.1736589

Sturing, L., Biemans, H. J., Mulder, M., and De Bruijn, E. (2011). The nature of study programmes in vocational education: evaluation of the model for comprehensive competence-based vocational education in the Netherlands. Vocat. Learn. 4, 191–210. doi: 10.1007/s12186-011-9059-4

Keywords: financial education, competence frameworks, primary education, cooperative learning, game-based learning, program evaluation

Citation: Andreatti G, Morselli D and Parricchi M (2025) Financial education through the lens of the EduFin framework: comparing two pedagogies in primary education. Front. Educ. 10:1628635. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1628635

Edited by:

Rashmi Ranjan Behera, Atal Bihari Vajpayee Indian Institute of Information Technology and Management, IndiaReviewed by:

Andrei Luís Berres Hartmann, Universidade Estadual Paulista Julio de Mesquita Filho, BrazilHumberto Andrés Álvarez Sepúlveda, Catholic University of the Holy Conception, Chile

Copyright © 2025 Andreatti, Morselli and Parricchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniele Morselli, RG1vcnNlbGxpQHVuaWJ6Lml0

Giovanna Andreatti

Giovanna Andreatti Daniele Morselli

Daniele Morselli Monica Parricchi

Monica Parricchi