- Department of Special Education, College of Education, Imam Mohammad ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Background: Inclusive education is a global priority aimed at ensuring equitable learning opportunities for all students, including those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Teachers’ knowledge and attitudes play a pivotal role in the successful implementation of inclusive practices. In Saudi Arabia, limited research has explored these dimensions among special education teachers.

Objective: This study aimed to assess the knowledge and attitudes of special education teachers in Riyadh toward inclusive education for children with autism in mainstream schools and to identify key demographic predictors influencing these variables.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional design was employed. A total of 321 special education teachers were recruited using a convenience sampling technique. Data were collected using a structured, self-administered questionnaire comprising three sections: socio-demographic data, a 15-item knowledge scale, and a 15-item attitude scale. Descriptive statistics, independent samples t-tests, ANOVA, and multiple linear regression analyses were performed using SPSS, with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results: Findings revealed that teachers demonstrated a moderate level of knowledge (M = 3.29) and attitudes (M = 3.48) toward inclusive education. Significant differences were observed based on gender, age, educational qualification, teaching experience, and previous autism-related training. Regression analyses showed that female gender, higher educational qualifications, longer teaching experience, and prior autism training were significant predictors of both higher knowledge and moderate attitudes (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: While teachers exhibited generally supportive views of inclusive education, key knowledge gaps and structural challenges remain. Targeted professional development and institutional support are essential to enhance the capacity of teachers to effectively include children with autism in mainstream settings.

Introduction

Inclusive education has gained global traction as a fundamental principle of equal educational opportunities for all students, including those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Recognizing the rights of children with disabilities to learn alongside their peers in mainstream settings, international frameworks such as the Salamanca Statement have pushed for inclusive practices in educational systems. However, the effective implementation of inclusion, especially for children with ASD, largely hinges on the preparedness, knowledge, and attitudes of teachers (Russell et al., 2023). Teachers are often the primary agents in implementing inclusive strategies and accommodating neurodiverse learners in classroom environments, yet their knowledge and acceptance of autism varies greatly.

Research shows that teachers’ understanding of autism and their beliefs about the capabilities of students with ASD are significant predictors of successful inclusion (Low et al., 2020). Inadequate knowledge can lead to misconceptions and resistance toward integrating these students, thereby limiting their academic and social development. For example, Leonard and Smyth (2022) emphasized that teachers who receive specialized training are more likely to display positive attitudes toward inclusive education. Furthermore, studies from different countries reflect diverse levels of teacher readiness, influenced by factors such as educational policies, cultural attitudes, and the availability of resources (Lu et al., 2020; Muñoz Martínez et al., 2023).

The inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream schools is particularly complex due to the unique behavioral, communication, and social interaction challenges associated with the disorder. Paraskevi (2021) highlighted that both general education and special education teachers often feel unprepared to support autistic learners effectively in typical classrooms. This lack of preparedness contributes to reluctance in embracing inclusive education, which can in turn hinder policy implementation. In Ethiopia, Tsegaye et al. (2025) found that a significant proportion of preschool and primary school teachers held moderately negative or ambivalent attitudes toward inclusion, largely due to insufficient training and institutional support.

Moreover, teachers’ perceptions are not solely shaped by their knowledge but also by their cultural and contextual understanding of disability. Aihie and Uwaoluetan (2022) revealed that while many Nigerian primary school teachers had basic knowledge of autism, their attitudes toward inclusion were still largely negative, signaling a disconnect between awareness and acceptance. Similar findings were observed in China, where Lu et al. (2020) reported that despite high self-efficacy among teachers, many still felt unprepared to meet the needs of autistic learners. These findings suggest the need for both structural and pedagogical changes to support inclusive education more comprehensively.

In Saudi Arabia, although the Ministry of Education has made strides toward inclusive education, several studies indicate persistent gaps in teacher preparedness and positive attitudes. Khalil et al. (2020) found that mainstream teachers in Jeddah held limited knowledge about autism and expressed concerns about integrating such students into regular classrooms. Similarly, Alkeraida (2023) documented that many Saudi primary school teachers lacked the confidence and practical skills required for inclusive teaching. These concerns are compounded by systemic issues such as overcrowded classrooms, lack of teaching assistants, and limited access to training.

The role of professional development cannot be overstated in shifting teacher attitudes and equipping them with inclusive practices. Leonard and Smyth (2022) emphasized the transformative effect of structured training on fostering inclusive mindsets. In their systematic review, Russell et al. (2023) concluded that hands-on experience, mentorship, and continuous education were key factors in improving teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. This reinforces the necessity of investing in professional development programs that are contextualized to the needs and realities of each educational setting.

Despite growing international efforts and local policies, disparities remain in the practical execution of inclusive education, particularly for children with ASD. Educators’ knowledge and attitudes are foundational pillars for creating supportive learning environments, yet these aspects remain underexplored or insufficiently addressed in many regions. Understanding the interplay between teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and inclusive practices is vital for ensuring equitable educational opportunities for children with autism. Consequently, this study aims to explore these variables within the Saudi mainstream school context, identifying gaps and proposing strategies for enhancement.

In Saudi Arabia, while inclusive education is officially endorsed as part of national education reforms, its practical application remains inconsistent—particularly concerning students with autism. Studies such as those by Khalil et al. (2020) and Alamri and Tyler-Wood (2022) have underscored significant limitations in teachers’ knowledge and comfort in integrating autistic learners into mainstream classrooms. Despite growing awareness, many educators continue to lack the training, confidence, and institutional support required for effective inclusion. Alzahrani and Alkadi (2024) highlight that prevailing social stigmas, insufficient in-service training, and unclear policy directives further compound the problem. This gap between policy and practice presents a pressing issue that warrants focused investigation to support children with autism in mainstream Saudi schools through informed and inclusive teacher engagement.

In Saudi Arabia, inclusive education has been formally promoted since the early 2000s as part of broader educational reforms aimed at integrating students with disabilities into mainstream classrooms. This commitment was bolstered by the Ministry of Education’s policies advocating for equal educational opportunities, alongside international frameworks such as the Salamanca Statement. Measures taken have included the establishment of specialized support units in schools and periodic training workshops for teachers (Khalil et al., 2020; Alamri and Tyler-Wood, 2022). However, despite these efforts, challenges remain in the consistent application of inclusive practices, with many teachers reporting limited resources and inadequate support to effectively accommodate students with autism in typical classrooms (Alkeraida, 2023; Alzahrani and Alkadi, 2024).

In Saudi Arabia, the initial training that special education teachers receive often lacks sufficient focus on inclusive practices and the specific needs of children with autism. Despite national education reforms that emphasize inclusive education, studies have indicated that many teachers enter the workforce without comprehensive training on evidence-based strategies for supporting autistic learners (Khalil et al., 2020; Alkeraida, 2023). This gap between formal education and practical skills can hinder the implementation of inclusive policies and limit teachers’ confidence in addressing the diverse needs of students with autism (Alzahrani and Alkadi, 2024). Recognizing this shortfall is critical to framing the current study and its implications for professional development in the Saudi educational context.

The present study aims to assess the knowledge and attitudes of special education teachers in mainstream schools in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, toward inclusive education for children with autism. By exploring these dimensions, the study seeks to identify key factors influencing teachers’ readiness for inclusive practices and highlight areas that require targeted professional development and institutional support.

Method

Research design

This study adopted a cross-sectional research design to assess teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism in mainstream schools. A cross-sectional design is appropriate for capturing a snapshot of participants’ characteristics, experiences, or perceptions at a single point in time (Cummings, 2018). Given the nature of the research objectives—examining existing levels of knowledge and attitudes among teachers—this design enables the collection of data from a large sample efficiently without the need for long-term follow-up.

By utilizing this approach, the study aims to explore the association between teacher characteristics (such as training, experience, and educational background) and their knowledge and attitudes toward the inclusion of children with autism. The cross-sectional design is particularly suited for identifying trends and patterns that can inform educational policy and professional development programs without manipulating variables or intervening in the school environment.

Research population

The target population for this study comprises all special education teachers currently employed in mainstream schools across Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. According to the most recent records from the Ministry of Education, the total number of special education teachers in Riyadh is approximately 23,014. This population includes male and female teachers working across different educational levels, including primary, intermediate, and secondary schools. These educators are directly involved in implementing inclusive education practices and play a pivotal role in supporting students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) within mainstream settings.

Focusing on this population allows the study to gather insights from individuals with specialized training and responsibilities related to inclusive education. Their perspectives are crucial in evaluating the current status of inclusion efforts for children with autism and identifying areas for improvement in policy, training, and support systems.

Research sample and sampling strategy

To determine an appropriate sample size for this study, the G*Power 3.1 software was utilized. The statistical parameters entered into the software included a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), an alpha level of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and up to 10 predictors in the multiple regression model. Based on these inputs, the recommended minimum sample size was 321 teachers.

Accordingly, a total of 321 special education teachers working in mainstream schools in Riyadh were selected to participate in this study. These participants were selected using a convenience sampling strategy, which was deemed practical and efficient given the accessibility of participants and the large geographical distribution of schools across Riyadh. Although convenience sampling has limitations in terms of generalizability, it allowed the researcher to gather timely and relevant data from respondents directly involved in inclusive education practices.

This sample size is considered adequate for conducting robust statistical analyses and achieving the study’s objectives of exploring teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward the inclusion of children with autism.

Data collection instrument

To gather the required data, a structured self-administered questionnaire was developed for this study. The instrument consisted of three main sections: demographic characteristics, knowledge about inclusive education for children with autism, and attitudes toward inclusion. The questionnaire was distributed in Arabic, the native language of participants, to ensure clarity and comprehension.

Section 1: demographic information

The first section collected demographic data about the participants. This included variables such as age, gender, educational qualification, teaching experience (general and in special education), school level (primary, intermediate, or secondary), and whether the teacher had received prior training on autism or inclusive education. This information helped to contextualize the findings and explore possible associations between demographic factors and teachers’ knowledge and attitudes.

Section 2: knowledge of inclusive education for children with autism

The second section assessed teachers’ knowledge regarding inclusive education for students with autism spectrum disorder. This section included 15 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree. The total possible scores ranged from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge.

• Scoring interpretation:

o 15–34: Low knowledge

o 35–54: Moderate knowledge

o 55–75: High knowledge

Section 3: attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism

The third section measured participants’ attitudes toward including students with autism in mainstream classrooms. This section also consisted of 15 items, using the same 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). Total scores also ranged from 15 to 75, with higher scores reflecting more positive attitudes.

• Scoring Interpretation:

o 15–34: Negative attitude

o 35–54: Neutral attitude

o 55–75: Positive attitude

Validity and reliability

To ensure the quality of the instrument, both content validity and internal consistency were assessed. The initial version of the questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of five experts in the fields of special education and inclusive teaching. Their feedback was used to refine item clarity, relevance, and appropriateness to the Saudi educational context. Minor modifications were made to improve the cultural and educational alignment of the tool.

A pilot study was conducted with a sample of 30 special education teachers who met the inclusion criteria but were excluded from the final study sample. The pilot results were used to test the reliability of the questionnaire. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were found to be 0.87 for the knowledge section and 0.91 for the attitudes section, indicating high internal consistency and reliability of the measurement tool.

Data collection procedure

Data collection was carried out over a period of 4 weeks following ethical approval. After obtaining official permission from the relevant educational authorities in Riyadh, the researchers coordinated with school administrators to distribute the questionnaire to special education teachers in selected mainstream schools. Participation was voluntary, and each participant was provided with an informed consent form outlining the purpose of the study, the confidentiality of their responses, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. The questionnaires were distributed in person and collected on-site to ensure a high response rate. Completed responses were reviewed for completeness before being included in the final dataset for analysis.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages, were used to summarize participants’ demographic characteristics, knowledge scores, and attitude scores. To examine differences in knowledge and attitudes based on demographic variables, inferential statistics were applied. An independent samples t-test was used to compare the mean scores of two-group variables (e.g., gender, previous training), while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess differences among more than two groups (e.g., educational qualification, years of teaching experience, and school level). All statistical tests were conducted using a significance level of p < 0.05 to determine statistical significance. This analytical approach allowed the study to identify meaningful patterns and associations between demographic factors and teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism.

Results

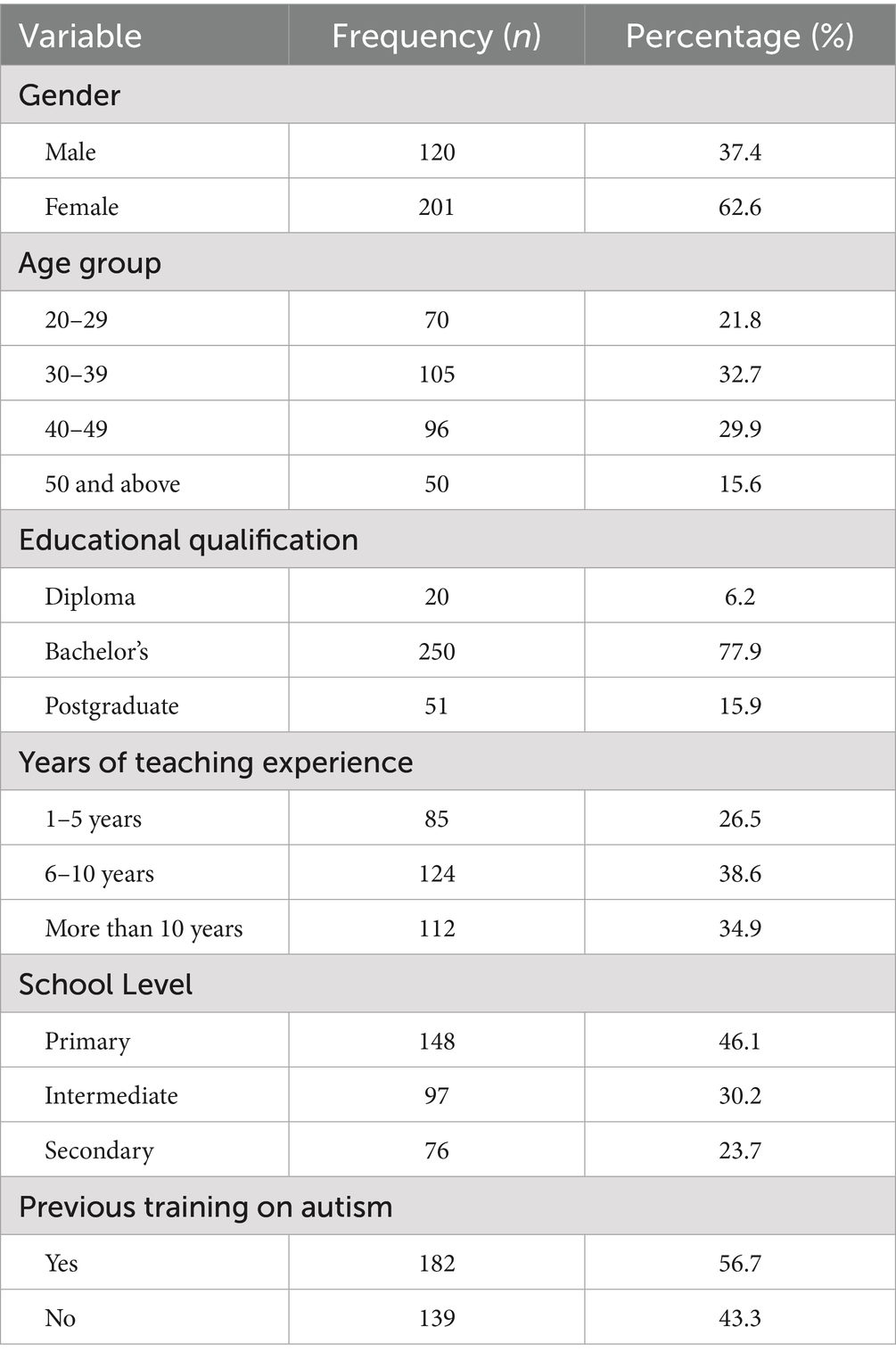

Participants in this study included a diverse group of 321 special education teachers working in mainstream schools across Riyadh. The sample was largely composed of female teachers, with a range of educational backgrounds and teaching experience levels. Most of the participants taught in primary schools, while a smaller proportion worked in intermediate and secondary levels. Over half of the teachers had received previous training on autism, reflecting varying levels of professional preparation for inclusive education. More detailed information about the demographic characteristics of the participants is presented in Table 1.

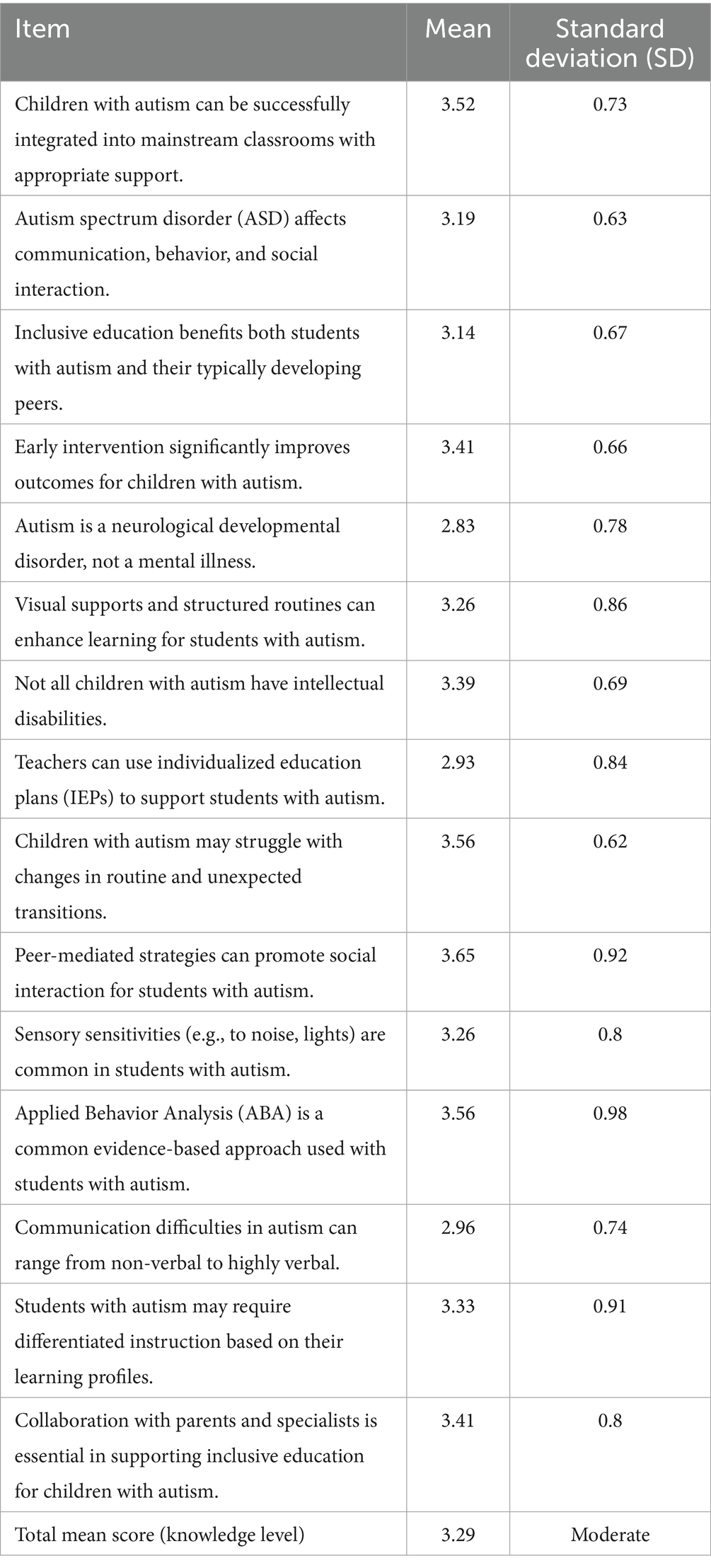

As shown in Table 2, the mean scores for special education teachers on the knowledge scale indicated a moderate level of knowledge about inclusive education for children with autism, with a total mean score of 3.29 on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation scores of the special education teachers on the knowledge scale.

Among the individual items, the highest mean score was for the statement “Peer-mediated strategies can promote social interaction for students with autism” (M = 3.65, SD = 0.92), followed by “Children with autism may struggle with changes in routine and unexpected transitions” (M = 3.56, SD = 0.62) and “Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is a common evidence-based approach used with students with autism” (M = 3.56, SD = 0.98). These results suggest that teachers are relatively aware of behavioral and instructional strategies relevant to autism inclusion.

Conversely, lower mean scores were observed for items such as “Autism is a neurological developmental disorder, not a mental illness” (M = 2.83, SD = 0.78) and “Teachers can use individualized education plans (IEPs) to support students with autism” (M = 2.93, SD = 0.84), indicating potential gaps in foundational and procedural knowledge that could affect the quality of inclusive practices. These findings underscore the need for targeted training programs to enhance teachers’ conceptual understanding and application of inclusive strategies for students with autism.

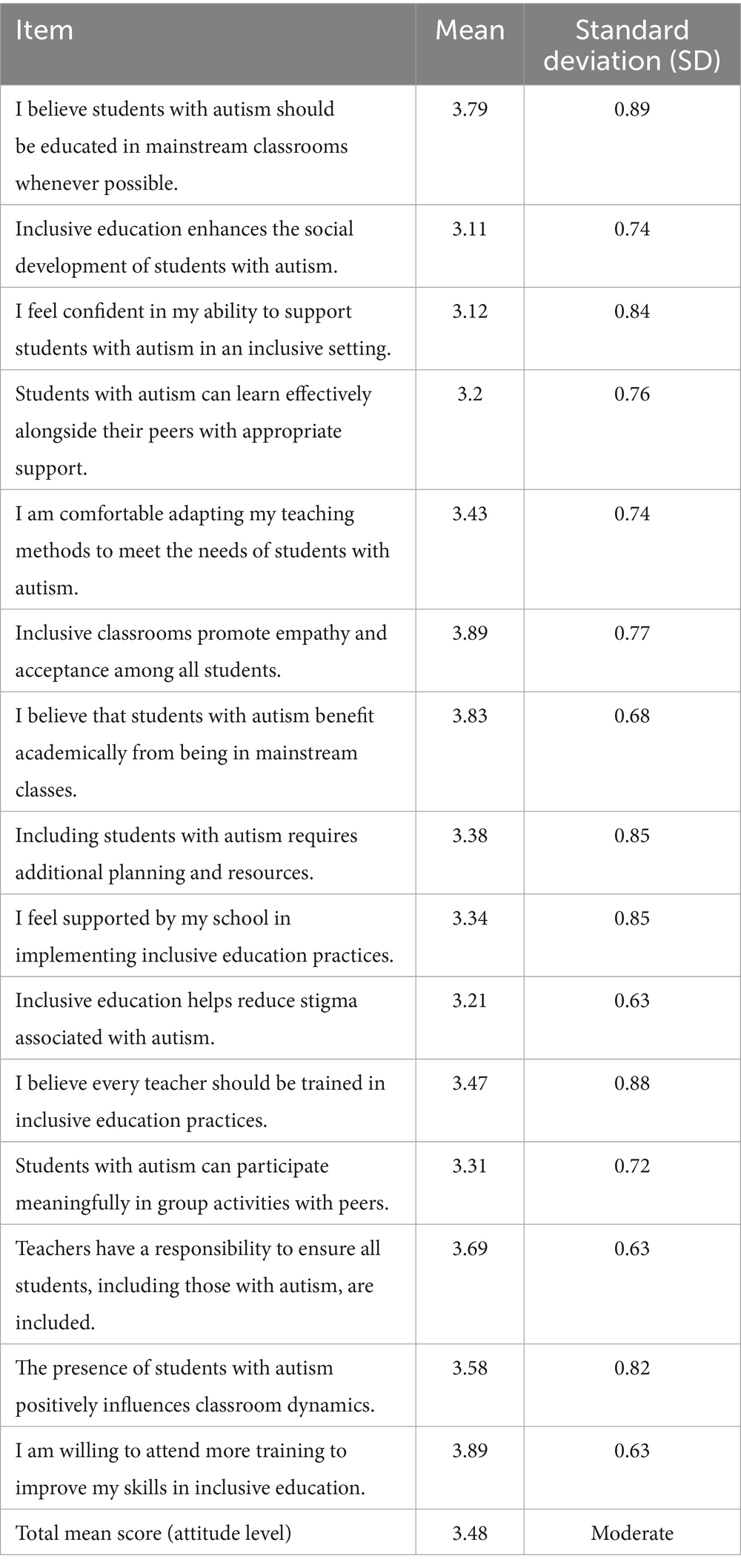

As shown in Table 3, special education teachers demonstrated a moderate overall attitude toward the inclusion of children with autism in mainstream classrooms, with a total mean attitude score of 3.48 on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 3. Mean and standard deviation scores of the special education teachers on the attitudes scale.

The highest levels of agreement were observed for the items “Inclusive classrooms promote empathy and acceptance among all students” (M = 3.89, SD = 0.77) and “I am willing to attend more training to improve my skills in inclusive education” (M = 3.89, SD = 0.63), indicating a strong recognition of the broader social benefits of inclusion and a willingness to enhance professional competencies. Similarly, positive attitudes were reflected in the statements “I believe that students with autism benefit academically from being in mainstream classes” (M = 3.83, SD = 0.68) and “Teachers have a responsibility to ensure all students, including those with autism, are included” (M = 3.69, SD = 0.63).

However, relatively lower mean scores were reported for items such as “Inclusive education enhances the social development of students with autism” (M = 3.11, SD = 0.74) and “I feel confident in my ability to support students with autism in an inclusive setting” (M = 3.12, SD = 0.84). These responses suggest that while teachers generally support inclusive education, some remain uncertain about its direct impact on student development or their own capacity to implement it effectively. This highlights the need for sustained institutional support and practical training to strengthen teachers’ confidence and positive perceptions toward inclusive practices.

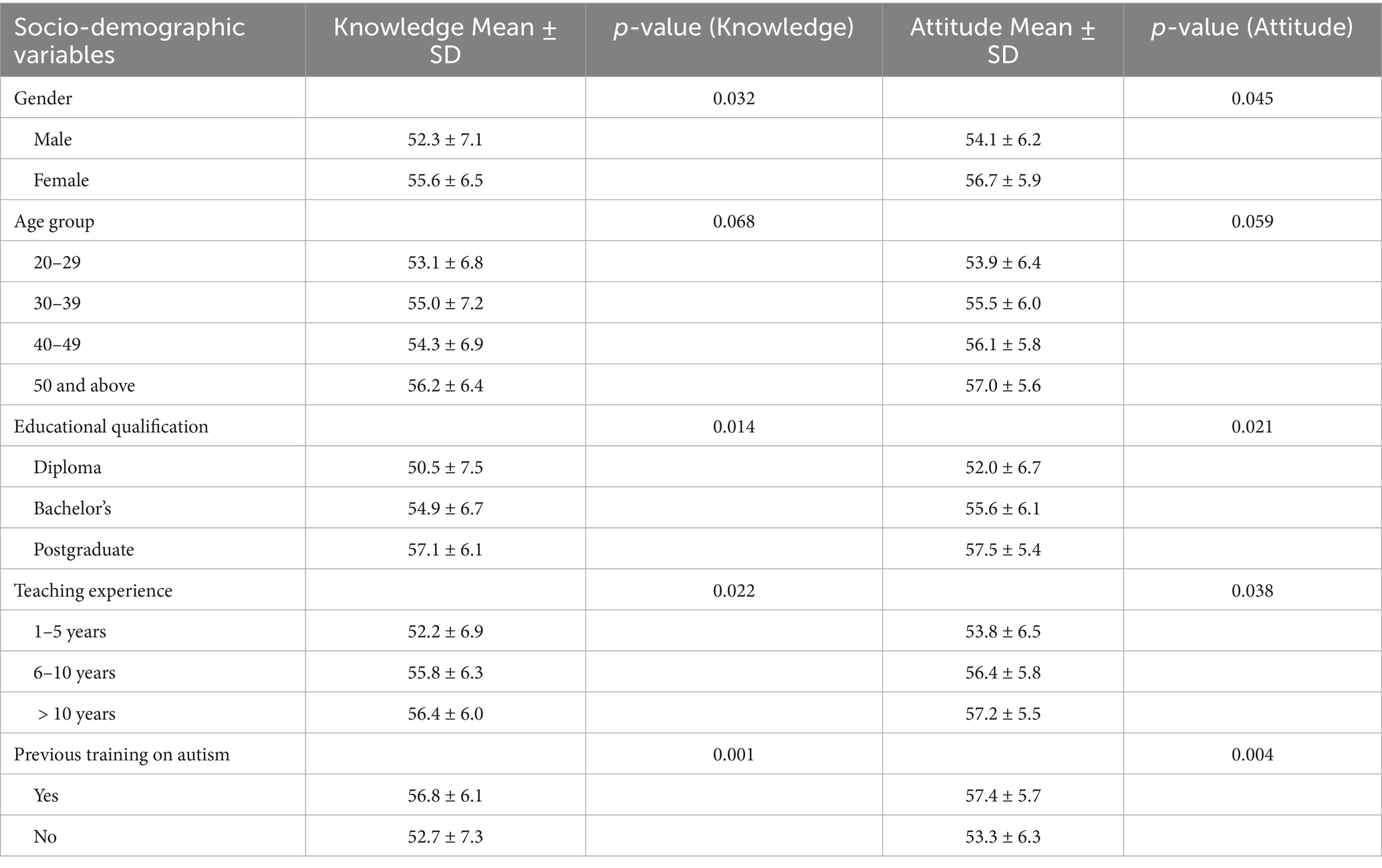

As shown in Table 4, statistically significant differences were found in both knowledge and attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism based on several socio-demographic variables.

Table 4. Differences in knowledge and attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism in mainstream schools based on participants’ characteristics.

In terms of gender, female teachers scored significantly higher than males on both the knowledge scale (p = 0.032) and the attitude scale (p = 0.045). Although age group differences were not statistically significant, there was a trend indicating increasing knowledge and more positive attitudes with older age, with the highest mean scores observed among those aged 50 and above (Knowledge M = 56.2, SD = 6.4; Attitude M = 57.0, SD = 5.6).

A significant association was also found between educational qualification and both knowledge (p = 0.014) and attitudes (p = 0.021). Participants with postgraduate degrees reported the highest scores on both measures (Knowledge M = 57.1, SD = 6.1; Attitude M = 57.5, SD = 5.4), followed by those with bachelor’s degrees.

Differences in teaching experience were statistically significant for both knowledge (p = 0.022) and attitudes (p = 0.038). Teachers with more than 10 years of experience had the highest scores (Knowledge M = 56.4, SD = 6.0; Attitude M = 57.2, SD = 5.5), suggesting a positive association between years of service and inclusive teaching perspectives.

Lastly, teachers who had previous training on autism scored significantly higher in both knowledge and attitudes compared to those who had not received such training, with p-values of 0.001 and 0.004, respectively. These findings emphasize the critical role of professional development and targeted training in enhancing inclusive education competencies.

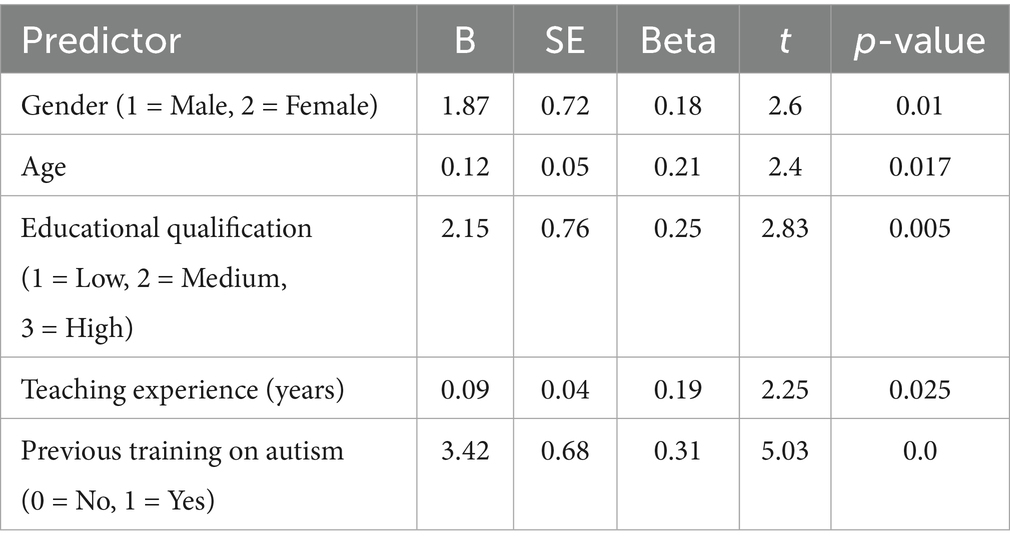

As shown in Table 5, multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the predictors of special education teachers’ knowledge about inclusive education for children with autism. The model revealed that several socio-demographic variables were statistically significant predictors of knowledge.

Table 5. Predictors of knowledge about inclusive education for children with autism in mainstream schools.

Gender emerged as a significant predictor, with female teachers scoring higher than male teachers (p = 0.01). Age also positively predicted knowledge (p = 0.017), indicating that older teachers tended to report greater knowledge about inclusive practices.

Educational qualification was another significant predictor, where teachers with higher academic degrees demonstrated greater knowledge (p = 0.005). Similarly, teaching experience was positively associated with knowledge levels (p = 0.025), suggesting that more experienced teachers had better understanding of inclusive education principles.

The strongest predictor in the model was previous training on autism, which showed a substantial and statistically significant effect on knowledge scores (p < 0.001). This finding highlights the critical role of targeted professional development in equipping teachers with the knowledge needed to support students with autism in inclusive settings.

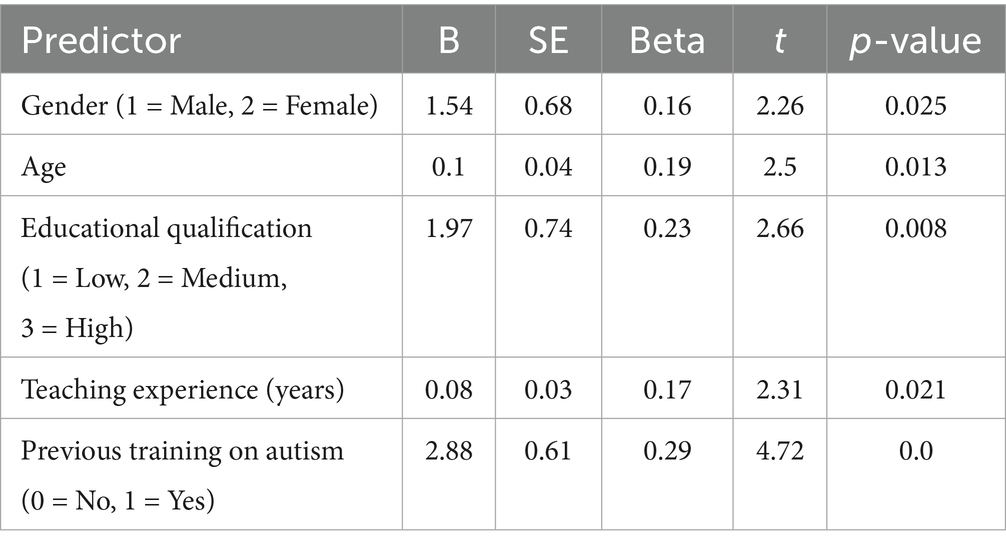

As shown in Table 6, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify the predictors of special education teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism. The results indicated that all included predictors had a statistically significant influence on teachers’ attitudes.

Table 6. Predictors of attitudes about inclusive education for children with autism in mainstream schools.

Gender was a significant predictor, with female teachers exhibiting more positive attitudes than their male counterparts (p = 0.025). Age was also positively associated with attitudes (p = 0.013), suggesting that older teachers were generally more favorable toward inclusion.

Educational qualification significantly predicted attitudes, with teachers holding higher academic degrees expressing more supportive views of inclusion (p = 0.008). Similarly, teaching experience showed a significant effect (p = 0.021), indicating that more experienced teachers tended to have more positive attitudes.

The most influential predictor was previous training on autism, which had the highest standardized beta coefficient (β = 0.29) and a highly significant p-value (p < 0.001). This underscores the critical importance of autism-specific training in shaping teachers’ perceptions and readiness to implement inclusive practices effectively.

Discussion

This study explored the knowledge and attitudes of special education teachers in Riyadh toward inclusive education for children with autism in mainstream schools. The findings revealed that overall, participants demonstrated a moderate level of both knowledge and attitudes. These findings are consistent with international and regional literature, suggesting that while teachers often express a general understanding and support for inclusion, there are significant gaps in more nuanced or applied knowledge. Previous studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, such as those by Alyami et al. (2022) and Low et al. (2020), also revealed similar moderate trends, highlighting the need for targeted efforts to deepen teachers’ understanding and strengthen their practical capacity to support students with autism.

The data from this study revealed certain weaknesses in foundational knowledge areas, particularly in understanding the neurological nature of autism and the structured use of tools such as Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). For instance, participants scored lower on items related to autism being a neurological condition rather than a mental illness, as well as on their familiarity with the implementation of IEPs. These findings mirror those of Alyami et al. (2022), who noted that although many Saudi teachers recognize surface-level characteristics of autism, they often lack comprehensive clinical and pedagogical knowledge. This gap in core understanding poses a risk to the quality of inclusive practices and suggests that current training and teacher education programs may not sufficiently cover essential autism-related content.

Interestingly, while the participants’ knowledge was moderate, their attitudes toward inclusion reflected encouraging signs of commitment and openness. Many teachers expressed agreement with the value of inclusive classrooms, particularly in fostering empathy and social acceptance among students. High scores were reported on statements supporting inclusion and the willingness to undergo further training. This willingness suggests a constructive disposition and readiness to engage in professional development, even among those who might feel underprepared. These findings are supported by Alshehri (2023), who reported that many educators in Saudi Arabia are ideologically supportive of inclusion but face practical limitations, such as insufficient training, large class sizes, and limited institutional backing, which affect implementation.

Among all examined variables, prior autism-specific training emerged as the most significant predictor of both knowledge and attitude scores. Teachers who had received such training consistently reported higher levels of awareness and more favorable perspectives on inclusion. This highlights the transformative effect of targeted professional development in preparing educators for inclusive environments. Alzahrani and Alkadi (2024) emphasized the importance of such training in their literature review, noting that access to high-quality, sustained professional learning opportunities is essential for fostering competence and confidence in inclusive teaching. Thus, incorporating autism-specific content into both preservice teacher preparation and in-service training appears to be a critical step toward improving inclusive education outcomes in Saudi Arabia.

The analysis also revealed that female teachers and those with more years of experience scored significantly higher on both the knowledge and attitude scales. These findings are in line with studies such as those by Almalky and Alwahbi (2023), which found that female educators in Saudi Arabia often demonstrate greater empathy and emotional investment in inclusive practices. It is possible that gender-related differences in communication styles, caregiving roles, and cultural expectations influence these outcomes. Likewise, teachers with more teaching experience may have had more exposure to diverse student needs over time, contributing to increased confidence and skill in accommodating children with autism. This suggests that years of practical experience may serve as an informal form of learning and professional growth.

Teachers with higher educational qualifications—particularly postgraduate degrees—also demonstrated significantly better knowledge and more positive attitudes toward inclusion. These results are in agreement with the work of Alsedrani (2018), who found that advanced education correlates positively with the application of evidence-based inclusive practices. Teachers with more academic exposure may have had access to current research, innovative methodologies, and reflective learning environments that enable them to think critically about inclusive education. Enhancing academic and research opportunities for special education teachers could therefore play an important role in improving both their theoretical understanding and their applied classroom practices.

Despite the overall positive findings, the results also point to ongoing systemic challenges that hinder inclusive implementation. Teachers expressed lower confidence in their ability to support students with autism and to adapt teaching strategies effectively, which likely stems from inadequate institutional resources and support. This aligns with previous reports, including those by Alshehri (2018) and Almalky and Alwahbi (2023), which emphasized that overcrowded classrooms, absence of teacher aides, and lack of specialized materials are key barriers to inclusive success. This suggests that training alone may not be sufficient unless accompanied by structural changes in school environments, including policy reform, funding allocation, and administrative support mechanisms.

While the findings provide important insights, this study has several limitations. First, the use of a cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw conclusions about causality between variables. Second, data were collected using self-report questionnaires, which may be subject to social desirability bias, with participants potentially overstating their knowledge or attitudes. Third, the study focused only on special education teachers in Riyadh, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions in Saudi Arabia or to general education teachers who also play a vital role in inclusion. Additionally, while the sample size was statistically adequate, a broader and more diverse sample could have provided more nuanced insights into regional or institutional differences. Future research should consider mixed-method designs and longitudinal studies to deepen the understanding of factors influencing inclusive education practices over time.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights that while special education teachers in Riyadh demonstrate a moderate level of knowledge and generally moderate attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism, significant gaps remain—particularly in foundational understanding and applied practices. Factors such as gender, experience, educational level, and prior training significantly influence both knowledge and attitudes. The findings underscore the need for structured, autism-specific professional development programs and stronger institutional support to enhance inclusive education practices. Addressing these areas will be essential to achieving meaningful inclusion and improving educational outcomes for students with autism in Saudi Arabia.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board at Imam Mohammad ibn Saud Islamic University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MA: Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Software, Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported and funded by the deanship of scientific research at Imam Mohammad ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Acknowledgments

The researcher would like to extend sincere thanks and deep appreciation to Al-Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University for their unlimited support, guidance, and encouragement throughout the course of this study. The university’s commitment to advancing academic research and fostering inclusive education has been instrumental in the successful completion of this work.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author(s) verify and take full responsibility for the use of generative AI in the preparation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to improve the readability, clarity, and linguistic flow of the text, assist in paraphrasing complex content, and support formatting of tables and structured sections. All content was critically reviewed and verified by the author(s) to ensure accuracy, originality, and alignment with the research objectives. No generative AI was used to create, analyze, or interpret the study’s data.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aihie, O. N., and Uwaoluetan, O. (2022). Primary school teachers' knowledge of autism spectrum disorders and their attitudes towards inclusive education. J. Teach. Teach. Educ. 10:11. doi: 10.12785/jtte/100104

Alamri, A., and Tyler-Wood, T. (2022). Teachers’ attitudes towards children with autism: a comparative study of the United States and Saudi Arabia. Educ. Sci. 12:138. doi: 10.3390/educsci12020138

Alkeraida, A. (2023). Understanding teaching practices for inclusive participation of students with autism in Saudi Arabian primary schools. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 27, 1559–1575. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1904015

Almalky, H. A., and Alwahbi, A. A. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions of their experience with inclusive education practices in Saudi Arabia. Res. Dev. Disabil. 140:104584. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2023.104584

Alsedrani, R. (2018). General education teachers' attitudes toward the inclusion of students with autism in general education classrooms in Saudi Arabia (Doctoral dissertation, Saint Louis University).

Alshehri, A. M. (2018). Teachers' attitudes about including students with autism in general education classrooms in Saudi Arabia (Doctoral dissertation, Saint Louis University).

Alshehri, D. Y. D. (2023). Teachers' attitudes about including students with autism in general education classrooms: inclusion policy for students with autism in Saudi Arabia—the challenge and prospects of teachers’ attitudes. J. Res. Curric. Instr. Educ. Technol. 9, 55–102. doi: 10.21608/jrciet.2023.285871

Alyami, H. S., Naser, A. Y., Alyami, M. H., Alharethi, S. H., and Alyami, A. M. (2022). Knowledge and attitudes toward autism spectrum disorder in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:3648. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063648

Alzahrani, S., and Alkadi, E. (2024). Educators’ attitudes toward inclusive education in Saudi Arabia: a literature review. J. Spec. Educ. Rehabil. 17, 41–63.

Cummings, C. L. (2018). “Cross-sectional design” in The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. ed. M. Allen (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc).

Khalil, A. I., Salman, A., Helabi, R., and Khalid, M. (2020). Teachers’ knowledge and opinions toward integrating children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream primary school in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 5, 282–293. doi: 10.36348/sjhss.2020.v05i06.004

Leonard, N. M., and Smyth, S. (2022). Does training matter? Exploring teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream education in Ireland. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 737–751. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1718221

Low, H. M., Lee, L. W., and Che Ahmad, A. (2020). Knowledge and attitudes of special education teachers towards the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 67, 497–514. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2019.1626005

Lu, M., Zou, Y., Chen, X., Chen, J., He, W., and Pang, F. (2020). Knowledge, attitude and professional self-efficacy of Chinese mainstream primary school teachers regarding children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 72:101513. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101513

Muñoz Martínez, Y., Simón Rueda, C., and de Dios Pérez, M. J. (2023). Teachers of learners with ASD in mainstream schools and classrooms in Spain: attitudes towards inclusive education. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 50, 104–126. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12448

Paraskevi, G. (2021). The inclusion of children with autism in the mainstream school classroom. Knowledge and perceptions of teachers and special education teachers. Open Access Libr. J. 8, 1–33. doi: 10.4236/oalib.1107855

Russell, A., Scriney, A., and Smyth, S. (2023). Educator attitudes towards the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorders in mainstream education: a systematic review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 10, 477–491. doi: 10.1007/s40489-022-00303-z

Keywords: inclusive education, autism spectrum disorder, special education teachers, teacher attitudes, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Alassaf MA (2025) Teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward inclusive education for children with autism in mainstream schools. Front. Educ. 10:1630710. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1630710

Edited by:

Weifeng Han, Flinders University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Marta Aparicio Puerta, University of Granada, SpainLorna M. Dreyer, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Alassaf. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed Abdulrhman Alassaf, bW9oYW1tZWRhbGFzc2FmODZAZ21haWwuY29t

Mohammed Abdulrhman Alassaf

Mohammed Abdulrhman Alassaf