- Music Department, School of Arts and Creative Technologies, University of York, York, United Kingdom

This paper presents findings from a subunit study of doctoral research carried out by the first author at the University of York, UK, investigating the language challenges faced by Chinese student-teachers on their English-taught MA music education programme. While previous research has addressed language challenges for international students and teacher trainees, these remain underexplored in music-related studies. Using a qualitative case study approach, data were collected through a questionnaire survey of student participants and semi-structured interviews with teaching staff on the focused MA music education programme. Findings indicate that these non-native music teacher trainees struggle with academic writing, music terminology, and verbal communication skills in instrumental/vocal teaching contexts, which affect their engagement with both theoretical and practical modules on their English-taught programme. Limited language proficiency influences their confidence in academic and teaching practices, which potentially hinders their pedagogical development as future instrumental/vocal teachers. The study highlights the need for discipline-specific language support tailored to the demands of the degree programme, contributing to the growing literature on international student experiences and the linguistic needs of music education teacher trainees who speak English as an additional language.

1 Introduction

1.1 Research background

International students constitute a significant proportion of the student population in Anglophone Higher Education Institutions (HEI), with the majority speaking English as an additional language (EAL) (e.g., Chinese students at UK universities) (HESA, 2024). Alongside the steady increase in international students’ enrolment are their significant contributions to economic revenue, cross-cultural exchange, and the internationalisation of the host institution (Universities UK, 2023). Consequently, EAL international students (hereafter EALs) have attracted extensive research interest in understanding their experience, paving the way for an internationalised and more inclusive learning and teaching environment in HE. Studies on Chinese EALs’ English language challenges, for example, illustrated the primary barriers in these students’ academic sojourn, and shed light on the betterment of available language support provided by the host institution (Fox, 2020; Holliman et al., 2024; Preston and Wang, 2017). Additionally, exploration of EAL student-teachers’ lived experiences could offer valuable cultural and pedagogical perspectives that contribute to the development of the host teacher education programmes or related schemes (Eros, 2016); this is reflected in Zheng and Li (2025) study on the Chinese ethnic instrumentalists taking a Western music teacher education taught postgraduate degree in the UK. However, there are few empirical studies exploring the linguistic components of EAL music students’ learning experience, particularly on EAL music preservice teachers. This gap in the literature motivated the first author’s doctoral research, which forms the basis for this article.

1.2 Research questions and objectives

The research questions (RQs) of the overarching case study are as follows:

RQ1: What language challenges do Chinese MA IVT students experience within their programme?

RQ2: What language support is provided for Chinese MA IVT students and how is it delivered?

RQ3: How do Chinese MA IVT students and the programme staff perceive the value of the language support sessions and their relationships to the students’ programme?

The first author’s thesis research responds to the limited empirical research concerning the language-related experience and support needs of music EALs studying English-medium HE music programmes, through an in-depth case study of Chinese MA IVT students at the University of York. Specifically, the research seeks to examine how Chinese students and the course tutors navigate students’ language challenges on the host programme, and how these challenges are addressed through institutional and programme-level support mechanisms. This paper focuses exclusively on one subunit of the thesis research and presents findings related to RQ1, guided by the following objectives:

• To identify English and subject-specific language challenges for Chinese MA IVT students within their theoretical and practical course modules;

• To understand how these language challenges affect Chinese MA IVT students’ engagement, learning, and teaching practices.

1.3 Literature review

EALs’ English language proficiency is of paramount importance in their academic sojourn and overall experience in the host institution. Quantitative research found a positive correlation between EALs’ English language proficiency and their academic success (Ghenghesh, 2015); their English vocabulary knowledge, for example, is reported to predict 20–53% of their academic achievement (Masrai and Milton, 2017). The correlation concerns the degree of cognitive demands experienced by EALs for their comprehension and processing of academic materials (Zhang and Zhang, 2022). From a qualitative perspective, studies highlighted the crucial role that EAL’s language proficiency, or linguistic skills and related adaptability of communication in the host environment, plays in their intercultural competence (Aspland and O’Donoghue, 2017), accumulation of social capital (Glass et al., 2015), acculturation process (Su, 2022) in the host environment. An individual with higher proficiency in the host language can navigate the available resources and adapt to the host environment with less difficulty (Glass et al., 2015), findings which are supported by a recent study on Chinese EALs in the UK (Jiang and Xiao, 2024). EALs with higher English proficiency are more likely to achieve better academic performance on the host programme and adapt more effectively to the host culture (Martirosyan et al., 2015; Singh and Jack, 2022).

English language concerns are highlighted in studies on Chinese EALs at Anglophone universities. In the UK context, English language is reported as an urgent concern among Chinese students, which presents challenges for their engagement with the curriculum and acclimation to the host academic society, particularly concerning their participation in lectures (Zhu and O’Sullivan, 2022) and accessing social networks with home students (Holliman et al., 2024). Being concerned about their ability to express themselves in English, Chinese students often remain quiet in communication with their teachers and peers during live sessions (Peng, 2023; Zhu and O’Sullivan, 2022). Participants in another study (Zhong and Cheng, 2021) also identified inadequate English language skills as the primary barrier to students’ application of critical thinking skills, despite their understanding of ‘critical thinking’ as a conceptual tool. While the inherent demands of using an additional language present challenges (Nation, 2001), Chinese students’ pre-departure English language training (O’Dea, 2022; Zhou et al., 2017), inherited cultural and pedagogical values (Holliman et al., 2024), and the demand of language proficiency in English-based academic language contexts (Cummins, 2000) can be considered as the main influencing factors concerning their language issues on the host programme.

Previous research sheds light on further investigation in discipline-specific contexts, concerning students’ subject-specific language proficiency, i.e., students’ terminological competence ‘which makes it possible for researchers, students, undergraduates to participate in professional intercultural communication on the basis of mastering general professional, professional and narrow professional terms’ (Botiraliyevna, 2021, p. 63). Currently, this topic is underexplored within music-related subject fields, particularly given the linguistic distance between original and translated music terminology (see examples in Table 1) and terminology-related instructions in the Chinese-speaking context. Ward (2014) delineated the three methods adopted in translating Western musical terms – transliteration (phonetical presentation), free translation (semantic presentation), and footnoted translation (addition of a semantic category to aid the term’s meaning to Chinese speakers) – and raised concerns that Chinese students might be placed ‘at a distinct disadvantage’ (p. 11) when participating in English-based music education and performance.

In addition to the inherited linguistic demands, studies (e.g., Fautley, 2010; Moore, 2021) suggest that tertiary music students’ prior learning experience, such as exposure to Western classical music training, theory, and type of instruction, play a crucial role in their level of effective engagement with subject-specific language and underlying conceptual knowledge – the constituent elements which form the cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1977) that students bring into their music degree study (Moore, 2021). In programmes grounded in the Western classical tradition, students who have received private instrumental tuition and theory education within conservatoire or formal school settings are positioned with greater cultural capital, particularly in academic contexts where this tradition is highly valued (Moore, 2012). By contrast, students with limited or different musical backgrounds may find it taxing to engage with the course content (Russell and Evans, 2015), including the technical vocabulary used by lecturers (Burland and Pitts, 2007). A lack of familiarity with the Western classical tradition is also associated with students’ lower academic confidence, higher level of anxiety, and increased self-doubt about achieving success in such programmes (Massy and Sembiante, 2023). Furthermore, study by Pitts (2003) on the hidden curriculum in HE music departments reveals how the informal learning environment, departmental culture and value, and staff-student dynamics significantly influence students’ experiences beyond the formal curriculum. This includes developing independence, managing performance-related expectations, and navigating implicit values about musical identity. The aforementioned factors, plus challenges created through the hidden curriculum (Pitts, 2003), in which aspects of cultural privilege and priorities can be transmitted, may amplify the demands on EAL students.

The present paper contributes empirical information to the EAL music students’ subject-specific language concerns from the perspective of Chinese MA students, making an important contribution to scholarship on EAL music teacher education students. Research (Han and Li, 2024; Sawyer and Singh, 2012) highlights the general English language challenges faced by EALs across diverse academic discipline backgrounds – for example, common issues with in-service EAL teachers’ pronunciation (Rowland and Murray, 2020). Low English speaking proficiency is reported to constrain these teachers’ practices in the classroom, restricting their ability to facilitate teacher-pupil discussion (Chen et al., 2020) and often leading to reliance on pre-rehearsed (Margić and Vodopija-Krstanović, 2018) or (over)simplified (Doiz and Lasagabaster, 2018) instructions. These issues point to a critical need for specialist language skills for the teaching profession in English for EALs, which extend beyond daily interpersonal English communicative skills (Elder and Kim, 2014). Specifically, these specialist language skills encompass message-oriented interactions (e.g., presenting information), activity-oriented interactions (e.g., giving instructions), framework interactions (e.g., explaining the objectives of the lesson), and extra-classroom language use (e.g., participating in seminars for professional development) (Elder, 1994; also see Sawyer and Singh, 2012), for non-language subject teachers. Studies also reveal that these specialist linguistic demands present particular challenges for EAL student-teachers’ practicum, despite their disciplines, coupled with their difficulties in navigating the pedagogical and cultural expectations in the host school communities (Han and Li, 2024; Sawyer and Singh, 2012). These issues align with those presented in music-specific studies (Lesiak-Bielawska, 2014; Ward, 2014) yet remain underexplored in regard to music teacher training. Situated in a music education context, this paper explores the discipline-specific language challenges experienced by Chinese EAL pre-service instrumental/vocal teachers and the impact of these challenges on their learning and teaching practices on the host programme, which provides an important contribution to the literature in this field.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Contextual information

The MA IVT at the University of York was established by Dr. Elizabeth Haddon in the academic year 2015/16, aiming to support teachers’ knowledge of music education and enhancement of their one-to-one instrumental/vocal teaching skills. Consisting of academic and practical modules, this course features a balanced emphasis on candidates’ pedagogical development in their theoretical understanding and practical skills in music education. Within their academic modules, students engage with research-informed music pedagogy, assessed by academic essays in the form of critical appraisal and literature review; and through practical modules, students are required to teach instrumental/vocal pupils from beginner to advanced level, assessed by recorded 15-20-min one-to-one lessons and corresponding 1,000-word reflective commentaries. Since its establishment, the MA IVT has attracted a diverse student body, with Chinese students forming a significant portion of its cohort. The above characteristics of the MA IVT provide a highly relevant context for the first author’s doctoral inquiry, enabling a comprehensive investigation into the language challenges faced by Chinese EAL student-teachers.

2.2 Methods and participants

A qualitative research design was adopted due to the nature of the RQs of this PhD research, and the case study strategy was selected to enable an in-depth investigation, drawing on data and method triangulation alongside rich descriptions that align with the inquiry (Creswell, 2014). Given the consideration of the research context and logistical feasibility for this small-scale study, Chinese students enrolled on the MA Music Education: Instrumental and Vocal Teaching (MA IVT) (from academic years 2020/21 to 2022/23) are defined as the ‘case’. This paper concerns Subunit 3 of the thesis research – Chinese MA IVT students from one academic year within the academic years 2020/21 to 2022/23 (S1, S2, S3…). Data from both students and MA IVT course tutors provides information on student participants’ language challenges in their MA IVT academic learning and teaching activities. Specifically, it uncovers the delivery and reception of module sessions in relation to students’ language proficiency, students’ academic language concerns in written assignments, and students’ language skills for teaching in their practical assessment (i.e., assessed lesson), from students’ and teachers’ perspectives.

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews with MA IVT course tutors and a qualitative questionnaire for Chinese MA IVT students; the data collection methods were selected as they enable in-depth exploration of participants’ perspectives and allow for the collection of rich, context-specific insights relevant to the research questions (Robson, 2024). As a widely used method in qualitative research, the semi-structured interview offers flexibility in the development of interview questions while maintaining a clear focus on topic of interest (Robson, 2024); this was appropriate for gathering data from MA IVT course tutors who undertake various roles on the programme. A qualitative questionnaire was used to collect information from students due to its practicality in reaching as many respondents as possible within the time-scale for data collection, and its word-based nature which features the suitability to a small-size participant pool (Cohen et al., 2007); this also enabled respondent anonymity. The data collection design was reviewed and approved by the University of York Arts and Humanities Ethics Committee; all participants gave informed consent before engaging with the interview or questionnaire.

Nine MA IVT course tutors (T1, T2, T3…) agreed to take part in a one-to-one semi-structured interview, scheduled on Zoom meeting or face-to-face to accommodate individual interviewees’ preferences. All interviewees were regularly engaged with MA IVT students’ submission marking, including academic essays and assessed lessons. Additionally, they undertook varied commitments in delivering/leading MA IVT programme sessions such as tutor group sessions, ‘Talking about Music’ sessions, ‘Peer Teaching and Learning Group’, and one-to-one academic writing tutorials.1,2 Regarding RQ1, interviewees were asked about Chinese MA IVT students’ language challenges noted in their experiences of teaching/tutoring and marking on the course. Interviewees were also invited to share their insights into the leading factors concerning these students’ challenges and their negative impacts on their MA IVT activities.

A qualitative questionnaire created on Qualtrics was distributed in March 2023, with a month for completion, to all 83 Chinese MA IVT students through group emails and WeChat group posts. The questionnaire consists of three sections, with questions relating to student participants’ self-report on their English language and music subject-specific language proficiency (section 1), their perceptions of the impact of English on their MA learning and teaching experience (section 2), and their uses of and views on the support provided by the University of York and Music Department (section 3). The questionnaire included questions developed from the interviews with the MA IVT tutors, which relate to students’ perceptions of language proficiency in their own instrumental/vocal teaching, the usage of musical terms, and the value of support provided by the university and the course. 50 responses were recorded, including Western instrumentalists (n =36), traditional Chinese instrumentalists (n = 7), and vocalists (n = 7).

All data was analysed on the specialised qualitative data analysis software MAXQDA, following the six-phase thematic analysis framework (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The dataset was read through repeatedly alongside the data collection to enable the first author to gain familiarity (Phase 1); preliminary notes were generated as memos on MAXQDA. Initial codes were generated (Phase 2) with open coding: without a pre-set coding framework, each data item was given equal attention to allow for the emergence of potentially meaningful patterns relevant to the RQs. The development of themes took place over the phases of searching for themes (Phase 3), reviewing themes (Phase 4), and defining and naming themes (Phase 5), under the second author’s supervision. All themes are clearly labelled for the report write-up (Phase 6). Findings presented in the following section are categorised by two umbrella activities – MA IVT learning and teaching practices – that student participants engaged with on the programme, highlighting particular concerns in thematised sections.

3 Results

Results presented in this section synthesise course tutors’ and students’ perspectives on Chinese MA IVT students’ language challenges on the course, concerning their roles as master’s music education students (3.1 Learning Music Education in English) and as instrumental/vocal student-teachers (3.2 Teaching Music in English). Each section is thematically organised, focusing on Chinese MA IVT students’ challenges in their English spoken communication (section 3.1.1), Western musical terminology (section 3.1.2), academic textual practice (section 3.1.3), as well as their low perceived teaching effectiveness (section 3.2.1) and undermined instrumental/vocal teaching practice (section 3.2.2) due to their language concerns.

3.1 Learning music education in English

3.1.1 English spoken communication as students’ primary concern

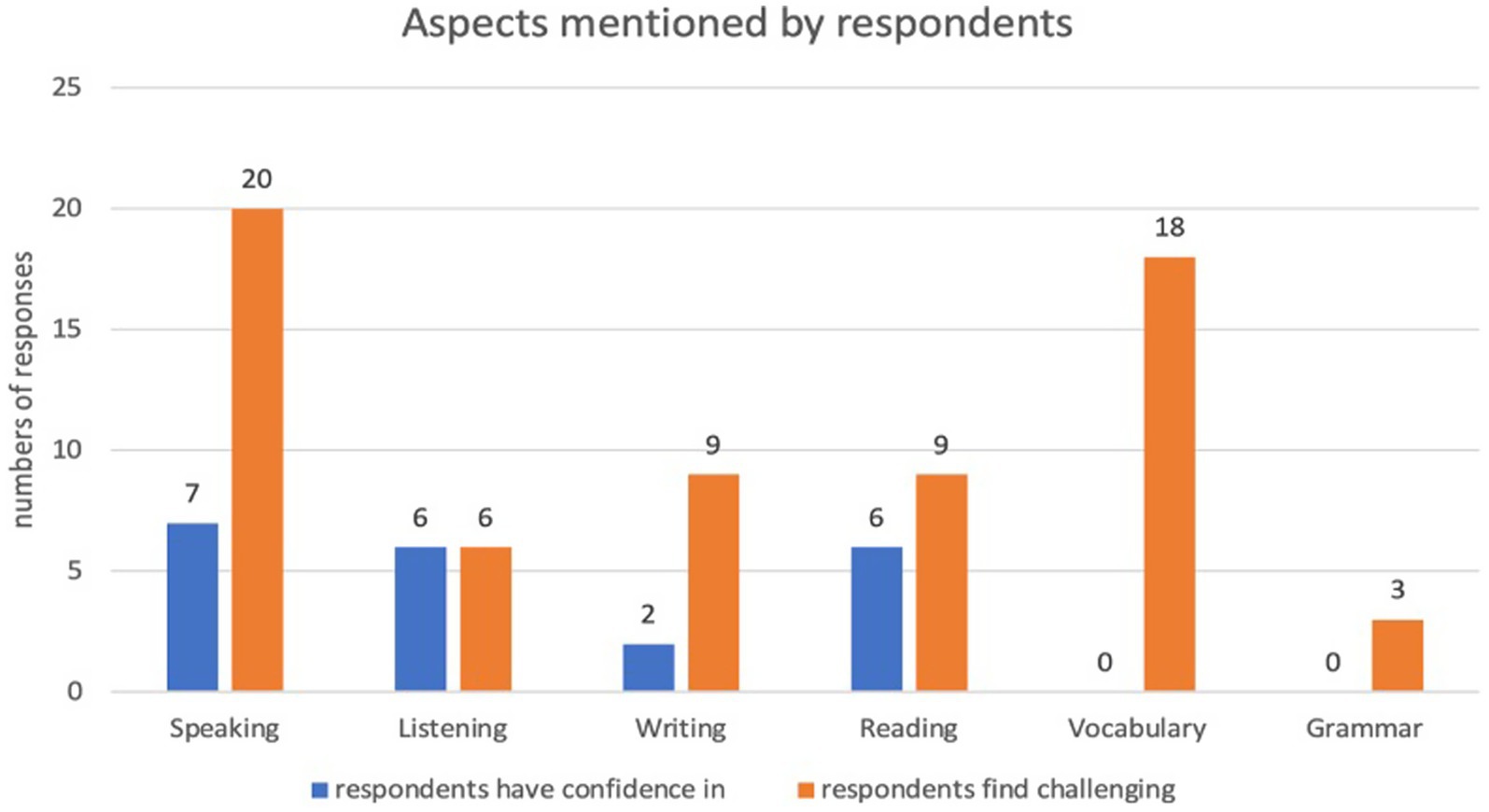

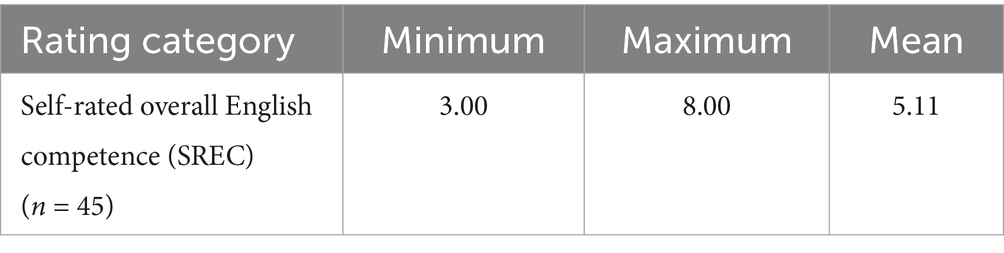

Questionnaire respondents were invited to evaluate their English language competence on a Likert scale (range 0 to 10, 0 = not good at all, 10 = very good) and state their reasons. Forty-five participants responded (see Table 2), among whom 43 provided reasons. Overall, respondents rated their English language competence as in the medium level (Mean = 5.11); the minimum rate is 3 (n = 8) and the maximum is 8 (n = 3), and the responses are clustered in the rates 5 (n = 12) and 6 (n = 11). Text-entry responses centred around the four components of English language skills – Speaking, Listening, Reading, and Writing, and aspects such as vocabulary and grammar. The information is displayed in Figure 1. Most respondents considered that ‘completing written assignments’ was impacted to the greatest extent due to their English language and subject-specific challenges.

Table 2. Students rating of their English language proficiency (0 = not good at all, 10 = very good).

Speaking (n = 20) and vocabulary (n = 18), associated with students’ English oral communicative competence, are considered weaknesses by most respondents. While some respondents perceived their speaking as their strength (n = 7), no respondent considered that they were competent in English vocabulary. Only two respondents considered that they were good at writing, and nine considered writing difficult. Three respondents highlighted grammar as the weaker aspect of their English proficiency, and no respondent noted this as their strength. Generally, concerns with English Speaking and vocabulary can be found throughout the self-ratings of 3 to 7 for these components. S31, who rated 3 in their self-rating of overall English competence (hereafter, SREC) noted: ‘[I am] able to read and understand academic literature and understand others for most of the time, but [I am] not good at spoken communication and [I] lack vocabulary’. Similar comments were given by other respondents: ‘[I] lack English vocabulary’ (S22, SREC = 4; S15, SREC = 5); ‘[I am] not good at spoken communication in English’ (S16, SREC = 6; S33, SREC = 7). Even for a respondent whose SREC was 8, they considered their vocabulary level as ‘average’ (S47). Some respondents felt that they have challenges in English Speaking due to their limited English vocabulary – ‘[I] often do not know how to express myself [because] I do not have much [English] vocabulary’ (S34, SREC = 4); ‘[I] lack [the] vocabulary for spoken English’ (S10, SREC = 4). English communication skills for course-related circumstances were also considered by some students. S32 (SREC = 5) considered their English communication to be of a ‘shopping mall’ level; S8 (SREC = 6) included their lack of ‘expression of subject-specific vocabulary’ in their evaluation.

3.1.2 Students’ perceptions of challenges in Western musical terminology

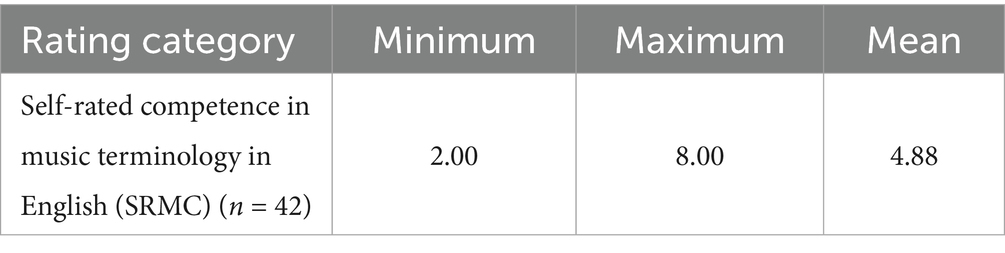

Forty-two respondents rated their competence in using musical terminology in English on a scale of 0 to 10 (0 = not good at all, 10 = very good). Generally, respondents considered themselves below average in this regard (see Table 3).

Table 3. Students’ self-ratings on their Western musical terminology (in English) proficiency (0 = not good at all, 10 = very good).

Thirty-two respondents reported that they had learned some Western musical terminology while studying in China; their engagement mainly included learning from their instrumental/vocal teachers (n = 10), from music theoretical modules in their undergraduate degree studies (e.g., ‘Music Theory’) (n = 8), and self-development activities (e.g., ABRSM exam preparation) (n = 2). The Chinese language is the main instructional language in which participants have learned about Western terminology (n = 23). While they reported that they had encountered some terms in their root languages, some respondents stated that they ‘did not learn how to pronounce the terms [in their root languages]’ (S42). The reported monolingual Chinese-based instructions mirrored Ward (2014) concerns regarding the potential alienation from subject-specific language used in the host teaching and learning environment experienced by Chinese students in their English-based overseas professional music education.

23 respondents noted other contributing factors to the challenges in their MA IVT learning, including a different form and style of teaching on the MA IVT as compared to respondents’ previous learning experiences (n = 12), cultural differences (n = 7), academic requirements (n = 4), personality traits (n = 2), and impacts of Covid-19 (n = 1). S32 reported their perceptions of the meta-linguistic influencing factors:

The cultural differences led to my fear of making mistakes, consequently I might lack critical thinking and [critical engagement] with teachers’ feedback. Also due to the cultural differences, I would misunderstand teachers’ requirements. Personally, I’m in favour of the teaching style that encourages students’ independent ideas – without a standardised answer – in that it has positive influences. However, without regulated reading tasks for each week, plus [my] procrastination, I could face tremendous pressure before the deadline of my assignments.

3.1.3 Students’ problematic academic textual practices

According to MA IVT tutors, in live taught sessions, students’ English language challenges were mainly demonstrated by their difficulties in understanding topics and task questions and their heavy reliance on translation technology for language support. Interviewees noted that there were frequent instances where students could not understand the subject-specific vocabulary of topics (e.g., musical terms). Understanding questions from the tutors and expressing ideas in English seemed to be particularly challenging for some students: ‘they might not understand that and sometimes even misinterpret what we said, and they give irrelevant answers’ (T9). In some cases, students were reticent when invited by tutors to have discussions or answer questions. In one-to-one communication with tutors, some students appeared anxious and apologetic about their English, feeling that ‘they cannot express themselves as they want to’, even though they were constantly reassured and encouraged to ask questions (T2).

MA IVT tutors also highlighted students’ problematic academic textual practices, including their limited comprehension of the academic writing parameters, problematic paraphrasing skills, and frequent lexico-grammatical errors. These challenges were primarily attributed to students’ English language proficiency levels, which interlinked with their understanding of Western academic skills. Considering the sophisticated nature of academic writing, some interviewees voiced the exacerbation of difficulty for students, particularly those with lower English proficiency:

… paraphrasing – it’s a difficult technique anyway … but with a limited vocabulary that makes it even harder … what we regularly see … is a student is paraphrasing but a lot of the main words are still there, so it’s too close to the original and they’d have been much better off quoting. Sometimes, by the way they’ve changed a word … it’s changed the meaning (T1).

Additionally, the concept of ‘critical thinking’ or ‘critical engagement’ seemed to be difficult to grasp for many Chinese MA IVT students (T2, T5, T9), which is reflected in students’ confusion on the concept (T5, T9) and the way they approached written assignments. For example, in the reflective lesson commentary (T2), students tend to interpret critical engagement as being ‘harsh’ (T2) on themselves in their role as the teacher in the lesson.

3.2 Teaching music in English

3.2.1 Students’ low perceived effectiveness in English-based teaching practices

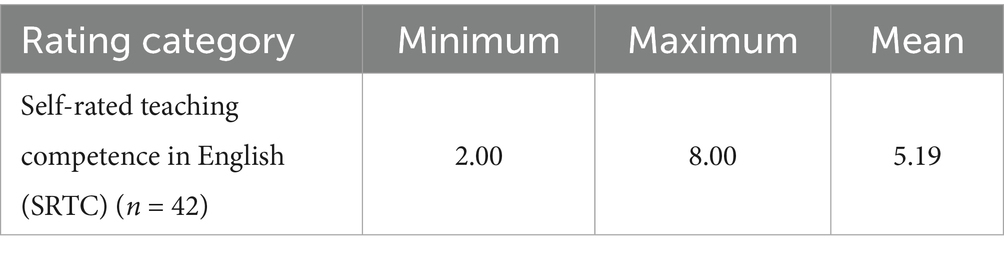

Respondents were asked to rate their overall teaching effectiveness when teaching in English. Forty-two responses were recorded, and 35 provided their reasons. Table 4 displays information about their self-rating of competence in teaching one-to-one instrumental/vocal lessons in English.

Table 4. Students’ self-ratings on their overall teaching competence in English (0 = not good at all, 10 = very good).

Overall, respondents perceived their teaching competence in English at an approximately medium level (mean = 5.19), as shown in their self-rating of competence in teaching in English (hereafter, SRTC). Their reasons mainly pertained to their general English spoken skills (n = 26) and command of musical terminology (n = 5); non-language aspects concerned their teaching experiences (n = 4) and reflection on their teaching approaches (n = 2). Respondents considered that the fluency, flexibility, and depth of their verbal instructions and interactions with their pupil were considerably undermined by their English language concerns: ‘Most of the time, there’s only vocabulary [for me to use] in Chinese in my head when teaching, and pauses happen as [I’m] not able to express [the vocabulary] in English’ (S9, SRTC = 3); ‘[I’m] able to have general communication if prepared, but if there’s an unexpected situation, [I’m] not able to cope with it well’ (S31, SRTC = 5). Being able to give comprehensible instructions in English is reported by S47 as the reason for their SRTC of 7. To what extent respondents perceived they could use musical terminology in their lessons seemed to be correlated with their SRTCs: ‘[I’m] able to use some musical terms’ (S11, SRTC = 7). The extent of teaching experience was considered pertinent to respondents’ pedagogical effectiveness: S40 (SRTC = 3) noted a ‘lack of teaching experience’, whereas S4 (SRTC = 7) reported that the quality of their lesson is ‘guaranteed’ as they ‘have teaching experience back in China’. S41 (SRTC = 5) highlighted their ‘need’ to improve their approaches to more pupil-centred teaching, and S17 (SRTC = 5) aimed for ‘rich’ teaching strategies.

Overall, ‘Establishing teacher-pupil dialogue’ and ‘Explaining musical concepts to the pupil’ were rated as being impacted by English to a larger extent than other aspects such as ‘Lesson planning (e.g., material selection)’, suggesting that the aspects that require spontaneity in English usage are perceived by student respondents as being impacted to a larger degree than those that do not. For lesson planning, more time for the organisation of the materials or teaching language is possible, as students prepare this in their own time and potentially with language-assisting software such as translating applications. However, while giving instrumental/vocal lessons (e.g., having teacher-pupil dialogue), particularly when the specific use of language depends on unpredictable factors (such as giving feedback to the pupil’s playing in the lesson), the impacts of English proficiency place uncertainty and/or stress on some students.

Respondents reported a range of challenges with musical terminology concerning their teaching practices, including pronunciation concerns (n = 15), limited vocabulary capacity and familiarity (n = 16), being unable to explain the terms (n = 3), and dysfluency in using the terms (n = 3). Even for respondents who rated themselves more highly on the self-rating of competence in musical terminology in English (SRMC), two of them (SRMC = 7) highlighted their ‘lack’ in this regard (S16), one reporting that they only have the ‘bases [sic]’ vocabulary for studying and teaching (S48). Without the vocabulary, some respondents would attempt to ‘describe’ the musical term instead (S15). Respondents who have the vocabulary found they are not able to explain it – ‘[I] can say some terms but [I’m] not good at explaining them [in English]’ (S36, SRMC = 5); ‘[I’m not able to give explanations related to musical terms]’ (S47, SRMC = 3).

Cultural differences, requirements of the pupil-centred approach, and external constraints were mentioned among the 16 respondents who considered factors in addition to their English language ability. S10 considered the potential gaps between their expressions and their pupil’s understanding due to cultural differences; S36 and S42 found the requirement for the application of pupil-centred approach difficult; the context of recording lessons was a stressor for S43, and some technical issues with the online lesson format seemed inevitable and could interfere with their lesson delivery (S47). Similar to the concerns with these students’ experience of learning activities on the programme, their experience of teaching practices faces integrative influences in addition to language barriers.

3.2.2 Students’ undermined teaching practices due to language challenges

MA IVT tutors highlighted their perceptions of common issues with Chinese MA IVT students’ English vocabulary size and oral production in the assessed lessons, which are considered to hinder effective teacher-pupil communication. With limited levels of English expressions and phonological control, students’ genuine intentions of instructions were distorted in their interaction with their pupils, which led to less effective communication (T1) and the pupil’s confusion (T2). Time management of the lesson was undermined as some students might need longer time to formulate the expressions for their instructions for the pupil (T1). Tutors also disclosed some students’ behaviours of using a script (of their oral output) in the assessed lesson: some students turned their lesson plan into a script (T7) or had questions for their pupils written in advance (T9) so that they ‘have something to say’ (T3). Some interviewees were also concerned that some students would provide the script for their pupils (T4, T7, T8, T9), ‘sharing a tablet and reading’ (T1) from the written dialogue:

In the worst-case scenarios, we do see a fully scripted lesson where the teacher asks the question and the pupil has already written down what they’re going to say because it’s all been prepared in advance, and then the pupil reads their answer, and then the teacher reads their answer. Even when someone’s played, the teacher then reads what they’re going to say about what the pupil’s played.

Using a script in assessed lessons results in a teacher-centred approach as students prioritised what is on the script rather than spontaneously responding to the pupil (T1, T4, T5, T8), which lessens the credibility of students’ attempts at pupil-centred teaching.

MA IVT tutors’ observations of students’ assessed lesson and formative teaching practices assignments revealed frequent mispronunciation (T2, T7, T8) and misuse of musical terms (T6, T8) in assessed lessons. T4 noted that ‘some students are clearly not aware of how to express a specific terminology like quaver or crotchet’. These instances raised tutors’ concerns with students’ vocabulary size of musical terminology in relation to the facilitation of their pupils’ understanding: without the specialist vocabulary, students tend to be less specific with their instructions (T1); with limited capabilities of articulating and explaining musical terminology, the student-teachers might present themselves as less professional (T6).

Commencing their course at the university, Chinese MA IVT students face ‘a new approach’ (T1) of instrumental/vocal teaching that might be ‘distant’ (T7) from their previous educational experience; this a pupil-centred teaching approach is perceived by interviewees (T1, T7, T8, T9) to be concomitant with these students’ language challenges in their English-based teaching practices. Consequently, establishing an effective teacher-pupil dialogue seemed challenging for these student-teachers. As T1 interpreted, students’ limited English vocabulary restrained their attempts at pupil-centred practices, which widened the gaps in their conceptual and procedural knowledge of the teaching approach; such gaps, in turn, presented extra pressure on students’ linguistic load:

If a student does not have the vocabulary or the range of vocabulary to enter into discussions … or to follow up [on] the pupil’s answer, it’s difficult to teach in a pupil-centred way … On this course … they are suddenly thrust into having to use much more subtlety of language and variety of vocabulary rather than just learning a few words like ‘good’ or ‘fantastic’ … they are being asked to give specific praise, so that opens up a whole new vocabulary.

These findings indicate interconnected challenges that Chinese MA IVT students face in English and pupil-centred pedagogical practices. Their limited specialist language for teaching not only hinders their teacher-pupil dialogue but also affects their ability to engage fully with the expected teaching approach. These linguistic barriers may, therefore, have broader implications for their professional identity and confidence as music educators.

4 Discussion

The study contributes to the understanding of existing theories by applying the concepts of terminological competence (Botiraliyevna, 2021) and teachers’ specialist language skills (Elder, 1994; Sawyer and Singh, 2012) to the underexplored context of Chinese music education students in an English-based HE course. By situating the frameworks within a practice-based discipline, the findings demonstrate how subject-specific language demands intersect with broader issues of English language proficiency, teaching self-efficacy, and pedagogical development. The above findings highlight English Speaking skills and vocabulary capacity as the primary concerns that impacted Chinese MA IVT students’ learning and teaching practice, echoing previous research reporting Chinese students’ taxing participation in their host course activities due to their lack of English vocabulary (Holliman et al., 2024; Medved et al., 2024). Data suggests that most of the Chinese MA IVT student respondents have lower confidence in English productive skills – Speaking and Writing, as compared to Listening and Reading, supporting previous research focusing on Chinese international students in English-based universities (Ke and Zhang, 2024). Further, the present study makes a unique contribution by demonstrating these challenges in relation to music studies, highlighting the specific linguistic and participatory difficulties faced by Chinese international students in a discipline-specific context –these findings provide empirical support to the concerns raised by Eros and Eros (2019) and Ward (2014). In the HE music context, the findings resonate with Lesiak-Bielawska (2014) report on Polish EAL music students’ challenges with musical terminology and reinforce the expectations placed on EAL music students’ academic language competence, particularly for engaging with their discipline textual practices that involve English-based literature (Kovačević, 2017). These insights emphasise the need for targeted language support for EAL music students for their enhanced engagement with the academic and practical demands of their degree study.

Related research suggests that Chinese students’ low confidence and engagement in oral interactions on their English-based host programmes could be partly attributed to their previous English learning experiences featuring exam-prioritisation and teacher-centredness, with minimal exposure to authentic English communicative activities in their home environment (O’Dea, 2022; Wang, 2015). As a result, students who primarily experienced large-class, reading-and writing-intensive English instruction may feel alienated from oral communicative activities on the host programme such as Q & A in seminars and peer discussions (O’Dea, 2022). The inherently demanding nature of acquiring proficiency in speaking in English can present significant challenges for their spoken interactions, compared to receptive (e.g., reading) or less spontaneous language activities (e.g., writing) (Celce-Murcia et al., 1995). Furthermore, phonological differences between the learners’ mother tongue and the host language could exacerbate the demand for their acquisition of the pronunciation features of the host language within the one-year MA tuition, particularly between the Chinese and English languages that are ‘historically and typologically unrelated’ (Yang et al., 2017, p. 3).

Inadequate engagement with instructions for Western musical terminology in root languages could contribute to their lower confidence and proficiency in the area of capacity in an English-based context (Ward, 2014). As questionnaire responses revealed, most student participants engaged with musical terminology in Chinese instructions only, without adequate knowledge of the pronunciation or the form of the international language of Western music. Also, to what extent musical terminology per se is (under) addressed in these students’ pre-MA education could cause alienation at a more profound level – students’ perceived importance of musical terminology in music learning and teaching could be related to their demonstration of language capacity in this regard. This study includes some traditional Chinese instrumentalists who may have followed ‘a different educational path’ (Eros and Eros, 2019, p. 565) than their Western instrumental/vocal peers, and the potential incompatibility between Chinese and Western music theory and musical terminology systems could contribute to this group’s struggles when encountering Western music terms on the MA IVT.

The above findings concern Chinese MA IVT students’ role as pre-service instrumental/vocal teachers who teach in an additional language, reinforcing and further illustrating students’ language concerns in this particular context. The description from student and teacher participants resonates with the constrained teaching practices outlined in the Literature Review, primarily concerning their message-oriented interactions and activity-oriented interactions (Elder, 1994). Furthermore, findings suggest that some Chinese MA IVT students’ limited effectiveness in language use as pre-service teachers was linked to gaps in their pedagogical knowledge, which they are expected to develop throughout their MA programme. This reinforces Freeman et al.’s (2015) assertion that pedagogical knowledge is a constituent element of effective instructional language use. Moreover, student-teachers’ musical experience and educational experience as learners, alongside the inherited cultural understanding of the role relationship between teacher and student (Elder, 1993), could influence how they perceive and approach teaching activities, and the resultant (dis)usage of particular linguistic skills. For example, a student-teacher taught by teacher-centred instructions as a learner might not be aware of responding to their own pupil, and thus could be less likely to adopt linguistic resources to form feedback and ask follow-up questions. Similarly, if a student-teacher considers the teacher-pupil relationship as hierarchical, they might not attempt egalitarian communication and rapport with their pupil, regardless of the language environment of the teaching context. However, Chinese MA IVT students’ identity as pre-service instrumental/vocal teachers warrants a longitudinal perspective to consider their language proficiency for teaching: these students simultaneously acquire pedagogical and English language development on the MA IVT; a paralleled progress in their increased pedagogical understanding and more proactive and effective language behaviours in teaching can be envisaged alongside their progress through the programme.

Furthermore, the present findings suggest that students’ (perceived) lower English proficiency affected their teaching self-efficacy – their belief in their ability to achieve the defined teaching goals or topics. This is particularly reflected in questionnaire responses regarding the impacts of English on their teaching: these students perceived that their actualisations of more pupil-centred instructions were primarily inhibited by their (perceived) English language and terminological issues. As the pre-service stage is an essential phase of the formation of teaching self-efficacy for music teachers (Regier, 2019), it is therefore essential to recognise locally-trained EAL student-teachers’ language concerns and their needs of targeted language support alongside pedagogical development. Situated in one-on-one instrumental/vocal teaching, the present findings provide empirical support to the importance of teacher language proficiency in shaping non-native teachers/teacher trainees’ confidence and instructional effectiveness.

International students in HE tend to prioritise the achievement of short-term academic objectives, which might govern their level of engagement with the medium of instruction (Wu and Hammond, 2011). For example, EAL pre-service teachers’ engagement with language proficiency for teaching might orientate to the completion and higher grades of practical modules on the English-based programme. However, this does not mean that the critical attention to EAL pre-service teachers’ concerns with teacher language proficiency should be narrowed within their academic sojourn. Rather, this aspect concerns the initiation of regulation and related pre-departure internship support mechanisms in a broader context. In the UK, for example, the current Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) regulation only requires the candidate’s SELT language test results (equivalent B2 and above, i.e., IELTS Band 6.5), which is equivalent to the minimum language entry requirement for postgraduate programmes across disciplines.3 This might not sufficiently address the language needs of EAL teacher candidates teaching in the English environment. The refinement of the regulation could be adapted from the specialised teacher language proficiency test assessment criteria such as the English Medium Instruction (EMI) certificating mechanisms. These resources can inform a more tailored regulation and support framework in the field, inviting pre-and in-service EAL teachers’ awareness and continuous development of their classroom language competencies (Macaro et al., 2020). The present qualitative findings can be complemented by quantitative and longitudinal insights in future research: for example, statistical analysis and progression of students’ linguistic accuracy can provide valuable information to the research topic. Further inquiries into the influencing components in EAL teacher students’ experiences in the overseas environment, such as the cultural and pedagogical forces, can contribute to a deeper understanding of how their professional identity, teaching self-efficacy, and adaptability are shaped or influenced in multicultural classrooms. Ultimately, these insights can provide valuable support for the development of research-informed frameworks for the host teacher education programme with a culturally diverse student body.

5 Conclusion

This paper presents part of the findings from a subunit study within the first author’s PhD project, focusing on the language challenges faced by a group of Chinese music education student-teachers on a UK MA programme. It examines their learning and teaching practices in an English as an Additional Language (EAL) environment. The findings, drawn from data collected from students and course tutors, highlight key aspects of students’ experiences, lending support to previous research while contributing new insights to the field of music-related studies. A key implication of this study is the need for greater attention to the teaching language proficiency of non-native teacher trainees who are required to teach in an additional language. While this issue has been explored in relation to language teachers, it remains underexamined in the context of teachers of non-language subjects, particularly in music education. Given the role of effective communication in instrumental and vocal teaching, addressing language-related challenges is essential for fostering an inclusive and supportive learning environment. Future research could further explore discipline-specific language support strategies to better equip international music teacher trainees for professional practice. The implications can also contribute to music teachers’ approaches to fostering inclusive learning environments in multicultural music classrooms (Li and Zheng, 2025, forthcoming).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Arts and Humanities Ethics Committee University of York. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. EH: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This project was undertaken without external funding. I would like to express my gratitude to my participants for generously sharing their time and insights, which made this research possible. I am also deeply thankful to my supervisor, Dr. Elizabeth Haddon, for her invaluable guidance and unwavering support throughout this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^‘Talking about music’ sessions are provided for MA IVT students as optional supporting sessions for their Western musical terminology.

2. ^‘Peer teaching and learning group’ is the formative practical activity on the MA IVT: students are assigned with another peer to deliver an instrumental/vocal lesson; they are required to submit a four-to five-minute excerpt of their recorded lesson and a 500-word reflective commentary and discuss these with peers and tutors in small-group sessions.

3. ^Information is available at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/qualified-teacher-status-qts-english-language-test and https://ielts.org/organisations/ielts-for-organisations/compare-ielts/ielts-and-the-cefr

References

Aspland, T., and O’Donoghue, T. (2017). “Quality in supervising overseas students” in Quality in postgraduate education. eds. Y. Ryan and O. Zuber-Skerritt (London: Routledge), 59–76.

Botiraliyevna, B. H. Formation of terminological competence in ESP education. JournalNX 6, 63–68. (2021). Available online at: https://repo.journalnx.com/index.php/nx/article/view/114 (Accessed May 12, 2025).

Bourdieu, P. (1977). “Cultural reproduction and social reproduction” in Power and ideology in education. eds. J. Karabel and A. H. Halsey (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 487–511.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burland, K., and Pitts, S. (2007). Becoming a music student investigating the skills and attitudes of students beginning a music degree. Arts. Hum. High. Educ. 6, 289–308. doi: 10.1177/1474022207080847

Celce-Murcia, M., Dörnyei, Z., and Thurrell, S. (1995). Communicative competence: a pedagogically motivated model with content specifications. Issues Appl. Ling. 6, 5–35. doi: 10.5070/L462005216

Chen, H., Han, J., and Wright, D. (2020). An investigation of lecturers’ teaching through English medium of instruction—a case of higher education in China. Sustainability 12:4046. doi: 10.3390/su12104046

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. 6th Edn. London, UK: Oxford Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cummins, J. (2000). “BICS and CALP” in Encyclopaedia of language teaching and learning. ed. M. Byram (Abingdon: Routledge), 76–79.

Doiz, A., and Lasagabaster, D. (2018). Teachers’ and students’ second language motivational self system in English-medium instruction: a qualitative approach. TESOL Q. 52, 657–679. doi: 10.1002/tesq.452

Elder, C. (1993). Language proficiency as a predictor of performance in teacher education. Melbourne Pap. Lang. Test. 2, 68–89. doi: 10.3316/aeipt.75515

Elder, C. (1994). Performance testing as a benchmark for LOTE teacher education. Melbourne Pap. Lang. Test. 3, 1–25. doi: 10.3316/aeipt.75509

Elder, C., and Kim, S. H. O. (2014). “Assessing teachers’ language proficiency” in The companion to language assessment. ed. A. Kunnan (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 454–470.

Eros, J. (2016). “Give me a break – English is not my first language!”: experiences of linguistically diverse student teachers. J. Music. Teach. Educ. 26, 69–81. doi: 10.1177/1057083715612198

Eros, J., and Eros, R. (2019). “English language learners” in The Oxford handbook of preservice music teacher education in the United States. eds. C. Conway, K. Pellegrino, A. M. Stanley, and C. West (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 559–574.

Fox, J. (2020). Chinese students’ experiences transitioning from an intensive English programme to a US university. J. Int. Stud. 10, 1064–1086. doi: 10.32674/jis.v10i4.1191

Freeman, D., Katz, A., Garcia Gomez, P., and Burns, A. (2015). English-for-teaching: rethinking teacher proficiency in the classroom. ELT J. 69, 129–139. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccu074

Ghenghesh, P. (2015). The relationship between English language proficiency and academic performance of university students – should academic institutions really be concerned? Int. J. Appl. Ling. Engl. Lit. 4, 91–97. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.4n.2p.91

Glass, C., Wongtrirat, R., and Buss, S. (2015). International student engagement: Strategies for creating inclusive, connected, and purposeful campus environments. Sterling: Stylus.

Han, J., and Li, B. (2024). Inclusion, equity and intellectual equality: a case of overseas educated multilingual students in an Australian teacher education programme. Lang. Cult. Curric. 37, 513–528. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2024.2361375

HESA (2024). Where do HE students come from? Available online at: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/where-from (Accessed March 20, 2025).

Holliman, A., Bastaman, A., Wu, H., Xu, S., and Waldeck, D. (2024). Exploring the experiences of international Chinese students at a UK university: a qualitative inquiry. Multicult. Learn. Teach. 19, 7–22. doi: 10.1515/mlt-2022-0020

Jiang, X., and Xiao, Z. (2024). “Struggling like fish out of water”: a qualitative case study of Chinese international students’ acculturative stress in the UK. Front. Educ. 9:1398937. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1398937

Ke, R., and Zhang, Y. (2024). A study on investigating the correlations between Chinese college students' English speaking anxiety, oral performance and oral achievement. Acad. J. Humanit. Social Sci. 7, 20–33. doi: 10.25236/AJHSS.2024.070403

Kovačević, D. (2017). Contrastive linguistic analysis of texts on classical music in English and Serbian and its possible applications in professional environment and ESP. J. Teach. Engl. Specif. Acad. Purp. 5, 35–48. doi: 10.22190/JTESAP1701035K

Lesiak-Bielawska, E. English for instrumentalists: designing and evaluating an ESP course. Engl. Specif. Purp. World (2014), 15, 1–32. Available online at: http://utr.spb.ru/ESP-World/Articles_43/Lesiak-Bielawska.pdf (Accessed: 12 May 2025).

Li, H., and Zheng, X. (2025). “Understanding subject-specific language challenges for music learners with English as an additional language (EAL): what are the impacts and how can teachers provide support?” in Instrumental music education. ed. E. Haddon (London, UK: Bloomsbury). in press

Macaro, E., Akincioglu, M., and Han, S. (2020). English medium instruction in higher education: teacher perspectives on professional development and certification. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 30, 144–157. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12272

Margić, B. D., and Vodopija-Krstanović, I. (2018). Language development for English-medium instruction: teachers’ perceptions, reflections and learning. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 35, 31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.06.005

Martirosyan, N. M., Hwang, E., and Wanjohi, R. (2015). Impact of English proficiency on academic performance of international students. J. Int. Stud. 5, 60–71. doi: 10.32674/jis.v5i1.443

Masrai, A., and Milton, J. Recognition vocabulary knowledge and intelligence as predictors of academic achievement in EFL context. TESOL Int. J.. 12: 128–142 (2017). Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1247860 (Accessed March 17, 2025).

Massy, P. J., and Sembiante, S. F. (2023). Pedagogical practices, curriculum development, and student experiences within postsecondary music education: a systematic literature review. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 45, 600–615. doi: 10.1177/1321103X221128172

Medved, D., Franco, A., Gao, X., and Yang, F. (2024). Challenges in teaching international students: Group separation, language barriers and culture differences. Lund: Genombrottet: Lund University Publications.

Moore, G. (2012). “Tristan chords and random scores”: exploring undergraduate students' experiences of music in higher education through the lens of Bourdieu. Music. Educ. Res. 14, 63–78. doi: 10.1080/14613808.2012.657164

Moore, C. (2021). “Fish out of water? Musical backgrounds, cultural capital, and social class in higher music education” in Higher education in music in the twenty-first century. eds. P. Harrison and S. Lebler (Abingdon: Routledge), 183–200.

O’Dea, X. C. (2022). Perceptions of Chinese top-up students transitioning through a regional UK university: a longitudinal study using the U curve model. J. Educ. Pedagogical Sci. 16, 163–170. Available online at: https://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/5545/. (Accessed March 17, 2025).

Peng, L. (2023). Explaining the silence in seminars among Chinese undergraduate students in UK universities. Lect. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2, 902–909. doi: 10.54254/2753-7048/2/2022571

Pitts, S. E. (2003). What do students learn when we teach music? An investigation of the “hidden curriculum” in a university music department. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2, 281–292. doi: 10.1177/14740222030023005

Preston, J. P., and Wang, A. (2017). The academic and personal experiences of mainland Chinese students enrolled in a Canadian master of education programme. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 19, 177–192. doi: 10.1108/IJCED-05-2017-0006

Regier, B. J. (2019). “Examining the sources of self-efficacy among instrumental music teachers” in Doctoral dissertation (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri-Columbia).

Rowland, L., and Murray, N. (2020). Finding their feet: lecturers’ and students’ perceptions of English as a medium of instruction in a recently-implemented master's programme at an Italian university. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 41, 232–245. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1614186

Russell, D., and Evans, P. (2015). Guitar pedagogy and preparation for tertiary training in NSW: an exploratory mixed methods study. Aust. J. Music Educ. 1, 52–63. doi: 10.3316/aeipt.208932

Sawyer, W., and Singh, M. (2012). Learning to play the “classroom tennis” well: IELTS and international students in teacher education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 37, 73–125. doi: 10.3316/INFORMIT.159701640879629

Singh, J. K. N., and Jack, G. (2022). The role of language and culture in postgraduate international students’ academic adjustment and academic success: qualitative insights from Malaysia. J. Int. Stud. 12, 444–466. doi: 10.32674/jis.v12i2.2351

Su, C. (2022). “Cultural, Linguistic, and Academic Adaptation: An Ethnographic Study of Teenage Chinese EAL Students in a UK Independent School” in Doctoral dissertation (London: University of London).

Universities UK. (2023). International facts and figures 2023. Available online at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/universities-uk-international/insights-and-publications/uuki-publications/international-facts-and-figures-2023 (Accessed March 20, 2025).

Wang, L. (2015). Chinese students, learning cultures and overseas study. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ward, L-J. An approach to Chinese-English bilingual music education. Victor. J. Music Educ. (2014), 1, 11–16. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1115423.pdf (Accessed March 15, 2025).

Wu, W., and Hammond, M. (2011). Challenges of university adjustment in the UK: a study of east Asian master’s degree students. J. Furth. High. Educ. 35, 423–438. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2011.569016

Yang, M., Cooc, N., and Sheng, L. (2017). An investigation of cross-linguistic transfer between Chinese and English: a meta-analysis. Asia-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 2, 1–21. doi: 10.1186/s40862-017-0036-9

Zhang, S., and Zhang, X. (2022). The relationship between vocabulary knowledge and L2 reading/listening comprehension: a meta-analysis. Lang. Teach. Res. 26, 696–725. doi: 10.1177/1362168820913998

Zheng, X., and Li, H. (2025). “Developing instrumental teaching cross-culturally: international preservice teachers’ pedagogical understanding with consideration of cultural intelligence” in Instrumental music education. ed. E. Haddon (London, UK: Bloomsbury). in press

Zhong, W., and Cheng, M. (2021). Developing critical thinking: experiences of Chinese international students in a post-1992 University in England. Chin. Educ. Soc. 54, 95–106. doi: 10.1080/10611932.2021.1958294

Zhou, G., Liu, T., and Rideout, G. (2017). A study of Chinese international students enrolled in the master of education programme at a Canadian university: experiences, challenges, and expectations. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 6, 210–235. doi: 10.1163/22125868-12340081

Keywords: Chinese students, English as an additional language (EAL), higher education, music teacher education, subject-specific terminology

Citation: Li H and Haddon E (2025) Discipline-specific language challenges faced by Chinese music student-teachers on a UK master’s programme. Front. Educ. 10:1631328. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1631328

Edited by:

Rifat Kamasak, University of Reading, United KingdomReviewed by:

Gwen Moore, Mary Immaculate College, IrelandNashruddin Nashruddin, Universitas Muslim Maros, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Li and Haddon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hang Li, aGFuZy5saUB5b3JrLmFjLnVr; MjczNzkzODk5QHFxLmNvbQ==

Hang Li

Hang Li Elizabeth Haddon

Elizabeth Haddon