- 1Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), Developmental Capable Ethical State, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Free State's Disaster Management Training Education Centre (DIMTEC), Bloemfontein, South Africa

- 3Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, Northwest University's African Centre for Disaster Studies (ACDS), Potchefstroom, South Africa

- 4Faculty of Education, Department of Science, Technology and Design Education, Midlands State University, Gweru, Zimbabwe

- 5Research Impact Centre, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

This article examines the intersection of disaster risk science, critical zones, and education in advancing sustainable development in Africa. It unpacks these interrelated concepts and explores their interconnected roles within the broader social-ecological system. Critical zones, dynamic interfaces where biotic and abiotic components interact, are increasingly recognized as key areas for understanding the processes that trigger and intensify disasters. By analyzing the role of these zones in disaster emergence, the article underscores the need to integrate disaster risk education into the curricula of African educational systems. It further argues that education is pivotal in equipping communities with the knowledge and skills to manage risks, reduce vulnerabilities, and build resilience. The article advocates for incorporating disaster risk science at all levels of education, from primary to tertiary institutions, while embracing a holistic approach that includes both formal and non-formal education sectors. Ultimately, it posits that such integration will cultivate informed and capable citizens, thereby making education for sustainable development in Africa a tangible reality, with disaster risk reduction and mitigation as critical outcomes.

1 Introduction

Africa's vulnerability to disasters is shaped by its socioeconomic context, rapid urbanization, and environmental degradation. Disaster risk science provides an interdisciplinary framework to address these challenges, focusing on understanding the interactions between natural systems and human activity that create disasters (Wisner et al., 2022). Critical zones where these most intense interactions are essential for analyzing disaster causation and promoting sustainable development. This article argues for embedding disaster risk science and critical zone concepts into education systems to equip communities with risk reduction and resilience-building tools. Disasters are not merely natural occurrences but are often the result of complex interactions between societal vulnerabilities and environmental hazards (Wisner et al., 2004; Burton et al., 1993; Wisner et al., 2014; UNESCO, 2023b). In Africa, where rapid urbanization, climate change, and socioeconomic disparities are more pronounced, critical zones or regions where these vulnerabilities converge require urgent attention (Wisner et al., 2022). Thus, education is pivotal in equipping communities with the knowledge and skills to understand and address disaster risks while fostering sustainable development. Over and above, most disaster risk reduction international agreements, such as the 2015-2030 Sendai Framework (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015) and several others, strongly encourage disaster management education, training, and research (Kunguma and Mapingure, 2023). The same scholars further state that there has been a significant growth in authors, policies, and legislation, pointing to the need for DRR education and that the existence of DRR education would evoke disaster risk knowledge, practice, actions, and behaviors of change in communities.

2 Problem statement

Critical Zones, defined as regions where environmental processes and human activities dynamically interact, offer a powerful framework for exploring the entanglement of social and ecological systems. In Africa, however, these Critical Zones remain under-explored, especially regarding their susceptibility to hazards and their potential to nurture resilient livelihoods (Arènes, 2021). Disaster Risk Science (DRS) holds key insights for hazard mitigation. Yet, in Africa, its utility is constrained by limited localized empirical data, fragmented institutional capacities, and poor alignment with community-led resilience approaches (Nemakonde et al., 2021; Nobambela and Yekani, 2025). Meanwhile, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is widely viewed as essential for strengthening adaptive capacity and resilience, but many ESD interventions in Africa fail to reflect local socio-environmental contexts, and often marginalize Indigenous knowledge systems—thus limiting their effectiveness for disaster risk reduction (Mbah and Liberty, 2025).

Recent research by Mbah and Liberty (2025) underscores that conventional climate-change education across the continent often emerges from colonial legacies and Western paradigms, which do not resonate with diverse African contexts. They call for transformative educational models anchored in place-based, decolonised, experiential, and holistic pedagogies to promote climate justice and meaningful adaptation. Similarly, David (2024) peer-reviewed analysis advocates for the integration of African Indigenous Knowledge (AIK) into ESD curricula, arguing that such inclusion contributes to more equitable and sustainable climate responses in vulnerable communities. On the disaster science side, localized evidence from South Africa's municipal governance context shows the integration of DRR into planning processes as central to effective resilience building at local scales (Nemakonde et al., 2021).

Collectively, these insights suggest that strengthening DRS and ESD in Africa requires contextualized frameworks, grounded in localized empirical research, meaningful inclusion of Indigenous and community knowledges, and institutional architectures that enhance cross-scale coordination (Nemakonde et al., 2021; Mbah and Liberty, 2025). Only then can Critical Zones research and education meaningfully contribute to resilient livelihoods and sustainable development across the continent. These intersecting challenges highlight the urgent need for an integrated framework that bridges Critical Zones, DRS, and ESD to tackle root vulnerabilities, strengthen resilience, and advance sustainable development. Addressing this knowledge gap is essential for informing policy, enhancing educational approaches, and empowering communities to withstand the growing risks posed by disasters. Thus, the key research question was how Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Science, and Education for Sustainable Development could be integrated into a unified framework to address disaster vulnerabilities and promote sustainable livelihoods in African contexts.

3 Methodology

While traditional qualitative research often operates within a single, established paradigm, this study adopts an integrative approach combining elements of the critical and constructivist paradigms, as recommended by Creswell and Poth (2018). The critical paradigm is applied to analyse literature on Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Science, and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Africa, to identify gaps shaped by enabling and constraining factors in community efforts to reduce risk and vulnerability. These factors are distilled into narratives and subsequently deconstructed using the constructivist paradigm, which facilitates the redefinition of resilience by interrogating underexplored dimensions within these domains.

The constructivist approach draws its theoretical grounding from Lave and Wenger's theory of Legitimate Peripheral Participation (LPP), which underscores the evolving interplay between mentors and learners as central to social learning. In this model, learning unfolds as individuals transition from peripheral observation to full engagement in community practices, initiating identity shifts that enable learners to internalize Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) values through situated educational experiences. Recent work by Mugari et al. (2025) and Kunguma and Mapingure (2023) situates LPP in South African flood-prone areas, demonstrating how participatory co-design processes in coastal communities facilitated learner's evolution from passive observers into active risk-aware agents. Similarly, Black et al. (2025) document how a visual community-led DRR intervention—through digital storytelling, photovoice, and mapping in marginalized urban neighborhoods in Cape Town fostered shifts in participant's roles and identities. These experiences echo bib67's findings 2023, who show how engagement in hands-on, collaborative educational activities transforms local learner's self-perceptions, embedding proactive attitudes toward DRR. Collectively, these studies affirm that constructivist, participatory pedagogies anchored in social practice and community contexts are powerful catalysts for identity-based transformation, enabling learners to embrace proactive DRR values and behaviors.

3.1 Case selection

The study adopts a purposive sampling strategy, selecting six cases from peer-reviewed literature, policy analyses, and field-based empirical studies undertaken in disaster-prone African contexts. Selection was guided by thematic relevance, with each case aligning to one or more of the three core domains: Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Science (DRS), and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), thereby ensuring conceptual coherence with the study's objectives (Terblanche et al., 2022). Attention was also paid to geographical and hazard diversity, drawing on examples from regions affected by floods, such as the KwaZulu-Natal and Zimbabwe floods, droughts, cyclones such as Cyclone Idai, and compound events involving drought–flood sequences in the East African drylands. This approach prioritizes depth over breadth, allowing for contextually rich insights that illuminate both enabling and constraining conditions influencing disaster risk reduction outcomes (Raphela and Matsididi, 2025). Although the cases are not intended to be statistically representative, they serve as illustrative exemplars that contribute to refining the conceptual model developed in this study.

3.2 Literature review method

The research questions derived from the problem statement, focusing on the integration of Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Science (DRS), and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), as well as on enhancing localization and community relevance in African contexts, directly shape the study's methodological approach and design. Addressing these complex, interdisciplinary challenges requires a flexible analytical lens that can accommodate diverse perspectives and contextual nuances. Consequently, this study adopts an integrative paradigm that combines critical and constructivist approaches, as recommended by Creswell and Poth (2018).

This integrative paradigm aligns with the purposive selection of African case studies, which facilitates in-depth exploration of real-world complexities and contextualized strategies to mitigate disaster vulnerabilities and promote resilience. Cases were selected based on their relevance to the thematic domains, hazard and geographic diversity, and availability of credible data, ensuring rich, context-specific insights that inform the study's conceptual framework. To synthesize the existing knowledge base effectively, the study employs a critical review as its primary literature method. Unlike systematic reviews that adhere to strict protocols, the critical review privileges researcher expertise and interpretive flexibility, enabling the selection, synthesis, and evaluation of a broad spectrum of theoretical, empirical, and practice-based sources (Snyder, 2019).

This approach offers distinct advantages, such as allowing researchers to selectively include literature that supports the development of theoretical frameworks and conceptual models, enabling a deep understanding of existing research by synthesizing various perspectives and identifying key gaps and trends (Ridley, 2023; Machi and McEvoy, 2023). It also requires less time for analysis and can capture a variety of methodologies (Snyder, 2019; Carver, 2020). However, it comes with notable disadvantages, such as the risk of multiple bias errors in interpretation or analysis, and the lack of systematic synthesis of literature and the possibility of omitting relevant literature due to its unstructured nature (Snyder, 2019; Carver, 2020; Bryman, 2021; Harzing, 2025; Machi and McEvoy, 2023). Despite these challenges, the insights generated through this critical review, combined with contextual case analyses, provide a robust evidence base that directly informs the conceptual model proposed to advance sustainable development and disaster resilience in African Critical Zones.

3.3 Rationale for literature critical review

The critical literature review was undertaken to evaluate the state of research on Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Creation, Disaster Risk Science, and Sustainable Development. This review employed a systematic methodology to examine the complex intersections between these domains, providing a robust foundation for further exploration of their interdependencies. The Web of Science Core Collection and Scopus databases were chosen as primary sources due to their extensive repositories of interdisciplinary research. These platforms are particularly suited for investigating the evolving narratives surrounding disaster risk and sustainability (Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016). Their comprehensive indexing capabilities allow for an inclusive yet targeted search of studies across diverse research fields.

Specific search keywords included “Education”, “Disaster”, “Risk Creation”, “Sustainable Development”, and “Disaster Risk Reduction”. These terms were tailored to align with the search functionalities of each database, ensuring a focused retrieval of relevant studies. This strategy enabled the identification of literature spanning multiple disciplines relevant to the research objectives (Petticrew and Roberts, 2008). To ensure the reliability of the findings, two independent researchers analyzed and synthesized the retrieved studies. Each article was reviewed meticulously to extract key insights, trends, and gaps. This collaborative approach minimized researcher bias and ensured a comprehensive understanding of the literature (Cook and West, 2012). Table 1 in the annexure outlines key peer-reviewed and credible sources that align with the domains of Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Creation, Disaster Risk Science, and Sustainable Development, particularly intersecting with education, risk creation, and disaster risk reduction. All were identified via web of science, scopus, and complementary searches, following systematic review methodologies analogous.

Table 1. Key peer-reviewed sources with domains of critical zones, disaster risk creation, disaster risk science, and sustainable development.

The selected sources were chosen for their methodological rigor, relevance to the interdisciplinary scope of Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Creation, Disaster Risk Science, and Sustainable Development, and their alignment with systematic review protocols (Petticrew and Roberts, 2008; Cook and West, 2012). All are recent peer-reviewed publications (2020–2025) indexed in Web of Science and Scopus, ensuring credibility, verifiability, and scholarly impact (Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016). They collectively span theoretical, empirical, and applied perspectives, incorporating global and local contexts to capture diverse narratives and frameworks, thus reflecting the complex interdependencies between the four domains. These sources also address emerging gaps in integrating education, indigenous knowledge, governance, and technological innovations into disaster risk discourse, thereby offering a robust evidence base for advancing interdisciplinary understanding and informing policy and practice.

Grounding the review in methodologically rigorous, interdisciplinary, and contemporary scholarship, the selected sources establish a credible knowledge base while providing the analytical depth required to interrogate the multifaceted realities of disaster risk in the African context. Such a foundation is particularly critical for examining the conundrum of disasters in Africa, where vulnerabilities are amplified by the compounded effects of ecological degradation, socio-economic inequities, and governance challenges (Pelling and Garschagen, 2019; Biermann, 2014). Insights drawn from diverse geographical and thematic contexts within the reviewed literature illuminate how global processes of disaster risk creation and environmental change converge with Africa's unique socio-political and ecological configurations (Steffen et al., 2018; Mongeon and Paul-Hus, 2016). This integrated perspective ensures that the discussion is situated within a theoretical and empirical frame, enabling a more nuanced understanding of the continent's disaster landscape in the Anthropocene.

4 Literature review

4.1 The conundrum of disasters in Africa

Our rapidly changing world presents significant challenges in meeting current human needs without compromising the ability of future generations to satisfy their own. This challenge is exacerbated in the current yet-to-be-accepted Anthropocene geological epoch, defined by profound human impact on Earth's systems. Evidence reveals heightened vulnerabilities in local and global ecological systems, accompanied by economic instability, social inequities, and fragile political structures (Steffen et al., 2018; Biermann, 2014). These dynamics underscore a state of ecological precarity, where interactions between human populations and the threats of natural and anthropogenic hazards have become increasingly frequent, leading to cascading social, environmental, and economic impacts (Pelling and Garschagen, 2019). In this context, human efforts are critical in transforming vulnerability into resilience. Disasters can be avoided by taking proactive measures before they occur, and their impact can be minimized by taking retroactive measures after their occurrence. This transformation hinges on the societal capacity for preparedness, response, and recovery, collectively determining resilience levels. Societal resilience to hazardous conditions is neither uniform nor static but varies across spatial and temporal scales, influenced by socioeconomic and environmental factors (Sherman, 2022; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2022).

Africa faces a heightened vulnerability to disasters due to a complex interplay of environmental, socioeconomic, and political factors. Critical zones, where human and ecological systems intersect, play a significant role in shaping these vulnerabilities. These zones are dynamic interfaces where human and ecological systems converge, encompassing regions like river basins, coastal zones, and mountainous areas. They are inherently sensitive to changes due to their ecological importance and socioeconomic activities, exacerbating vulnerabilities across Africa. More significantly, Africa's critical zones, such as wetlands and forests, provide essential ecosystem services, including water filtration, carbon storage, and flood mitigation. However, anthropogenic activities like deforestation, mining, and agriculture disturb these zones, leading to loss of biodiversity, reducing the ecological resilience to recover from disturbances (Creese et al., 2019), and increasing soil erosion and sedimentation in river systems, reducing their capacity to manage floodwaters. A good example is the deforestation of the Mau Forest in Kenya, which has significantly reduced water flow into the Mara River, affecting downstream agriculture and ecosystems.

4.2 Understanding critical zones and disaster creation

Critical zones, representing the thin layer of Earth where complex interactions among soil, water, air, and life occur, are hotspots for both ecological processes and disaster creation, particularly in regions where human activities exacerbate natural hazards. For example, deforestation in the Congo Basin disrupts water cycles, increasing flood and drought risks (Creese et al., 2019). Similarly, urban sprawl in cities like Lagos, Durban, and Johannesburg amplifies exposure to hazards such as floods and landslides. River basins, coastal areas, and mountain ecosystems in Africa are experiencing rapid degradation partly due to overexploitation of natural resources, deforestation, and poor land management practices, increasing the likelihood of disasters such as floods, droughts, and landslides. Thus, over-reliance on natural resources within critical zones exacerbates vulnerability.

The Niger Delta, which is rich in oil resources, faces severe environmental pollution from oil spills (both accidental and social conflict-related), thereby affecting both livelihoods and ecosystems. Its richness in natural resources has become a hotbed of social conflict. Overgrazing in the Sahel contributes to desertification, intensifying food insecurity and resource conflicts. Deforestation in the Congo Basin disrupts hydrological cycles, exacerbates droughts, and reduces flood resilience (Creese et al., 2019). Similarly, mining activities in West African critical zones have led to soil erosion, amplifying the risks of landslides and sedimentation in rivers. The following factors demonstrate the nexus between disaster creation and conditions in critical zones.

4.3 Climate change amplifying hazards and impacts on critical zones

Climate change intensifies vulnerabilities by altering the delicate balance of critical zones. Coastal areas in West Africa are experiencing sea-level rise, which inundates agricultural lands and displaces communities. Mountainous regions in Ethiopia and Rwanda face erratic rainfall, triggering landslides and soil degradation (Moges et al., 2020; Byiringiro et al., 2024; Uwihirwe et al., 2020). The compounded effects of climate change and human exploitation make these zones hotspots for cascading disasters. Climate change has intensified Africa's exposure to extreme weather events. Critical zones such as the Sahel region and coastal areas are particularly vulnerable due to their ecological sensitivity (Biasutti, 2019). Rising temperatures, prolonged droughts, and erratic rainfall patterns have exacerbated desertification in the Sahel, while sea level rise threatens coastal settlements in regions like West Africa (Berg and Sheffield, 2018; Kelman, 2020).

4.4 Rapid urbanization and poor land use

Unplanned urban expansion also occurs in critical zones, such as floodplains and steep slopes, increasing the vulnerability of populations. Informal settlements in and around many African cities, such as Lagos, Nairobi, Harare, Johannesburg, etc, often lack proper drainage systems, making them hotspots for disaster risks such as flooding.

4.5 Socioeconomic vulnerabilities

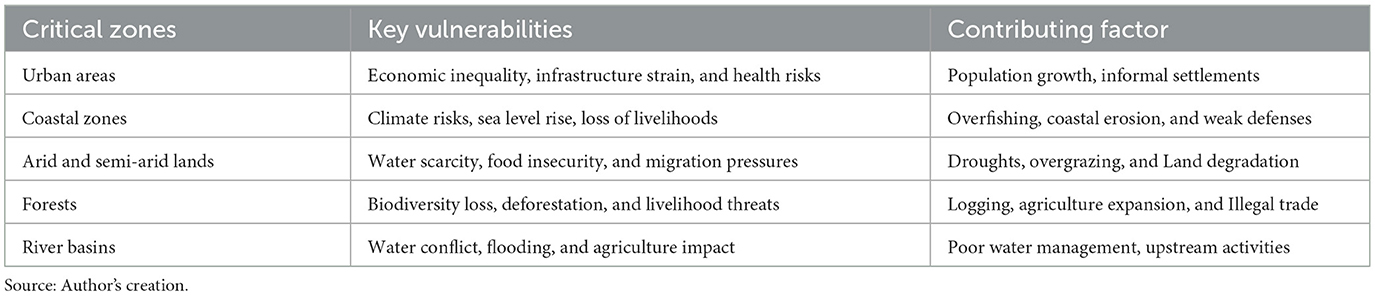

Africa's socioeconomic challenges are characterized by poverty, inequality, and weak governance, exacerbating the vulnerability of populations living in critical zones. Limited access to education and resources prevents communities from adopting sustainable practices, while weak policies fail to regulate activities in ecologically sensitive areas (Wisner et al., 2022). Table 2 illustrates how critical zones shape vulnerabilities in Africa, identifying critical zones such as urban, coastal, arid, and semi-arid forests, and river basins.

Wetlands in East Africa, critical for flood mitigation, have been drained for agriculture, increasing flood risks during heavy rains. Mountainous areas in Ethiopia and Rwanda, prone to landslides, are destabilized by deforestation and agricultural expansion.

4.6 Disaster risk science and critical zones

Disaster risk science is a transdisciplinary field that examines the root causes of disasters by analyzing the dynamic interplay between hazards, vulnerability, exposure, and coping capacities (Wisner et al., 2022; Cutter et al., 2023). Moving beyond hazard-centric models, it emphasizes how structural inequalities, governance failures, and environmental degradation co-produce disaster risk, particularly in critical zones, where socio-ecological pressures converge (Birkmann et al., 2022; Gaillard, 2021). Critical zones such as informal urban settlements, drylands facing desertification, or seismically active rift valleys are disproportionately exposed to hazards due to inadequate infrastructure, insecure tenure, and limited institutional support (Pelling and Garschagen, 2019). In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, spatial planning exclusion exacerbates flood and climate risks in informal settlements (Adelekan, 2020).

Recent advancements in disaster risk science emphasize the importance of place-based, co-produced, and anticipatory strategies. These include integrating indigenous knowledge, citizen science, and real-time data analytics into local governance systems (Sherman, 2022). Methods such as multi-hazard mapping and participatory vulnerability assessments help inform decisions in fragile contexts, while frameworks like the Risk–Resilience–Transformation continuum call for deeper, systemic changes that go beyond short-term adaptation. Critical zones are thus not only at risk, they also serve as “living laboratories” where the consequences of policy choices, environmental stress, and governance can be empirically studied (Green, 2024).

4.7 Sustainable development and disaster resilience in critical African contexts

Sustainable development, as defined by the Brundtland Commission (World Commission on Environment Development, 1987), entails meeting present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs. In the African context, achieving sustainable development necessitates the integrated pursuit of economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental stewardship, particularly in regions where socio-economic marginalization intersects with heightened climate and disaster risks (Aurélien, 2025). Such intersections amplify existing inequalities, disproportionately exposing vulnerable communities to hazards and compounding systemic fragilities.

Recent scholarship Green (2024) underscores the importance of embedding sustainable development within a decolonial and environmental humanities framework. Green (2024) argues that large-scale development and disaster risk strategies often marginalize local knowledge systems, leading to socio-environmental injustices that exacerbate vulnerability. Her work advocates for reconnecting communities with indigenous ecological knowledge and integrating these perspectives into policy and education to promote culturally relevant and socially just sustainability pathways (Green, 2024). This approach aligns closely with the aims of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 and 9, which emphasize quality education and resilient infrastructure as foundational for building adaptive capacity and reducing disaster risk.

SDG 4 recognizes education as a pivotal mechanism for building community resilience by equipping individuals with the knowledge, skills, and adaptive capacities necessary for disaster anticipation, mitigation, and recovery (English and Carlsen, 2019). Lifelong learning programs, especially those contextualized for climate-affected settings, embed disaster risk knowledge within formal and informal educational structures, thus strengthening preparedness and adaptation (UNESCO, 2023a). Inclusion of women, youth, and indigenous knowledge systems in education enhances social cohesion and empowers marginalized groups to co-create solutions, reducing vulnerability and fostering equitable resilience (Mwalwimba et al., 2024). However, persistent disparities in access and quality of education, particularly in rural and informal settlements underscore the need for sustained investment and policy coherence tailored to local realities (Mpiere et al., 2025).

Complementing these educational imperatives, SDG 9 stresses the importance of resilient infrastructure, sustainable industrialization, and innovation in disaster contexts. Climate-resilient, locally appropriate infrastructure is crucial for reducing hazard exposure and facilitating swift recovery (Kawasaki and Rhyner, 2018). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction further emphasizes the importance of proactive infrastructure planning, investment in disaster risk reduction (DRR), and the integration of scientific and local knowledge into design and implementation (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015). Education acts as a catalyst within SDG 9 by developing technical competencies, promoting DRR awareness, and ensuring that disaster science effectively informs infrastructural development and urban planning (Vaughter, 2016; Mulomba Mukendi and Choi, 2024). Participatory approaches that actively involve marginalized populations are critical to fostering infrastructure solutions that are socially just, culturally relevant, and sustainable (Gaegane, 2024).

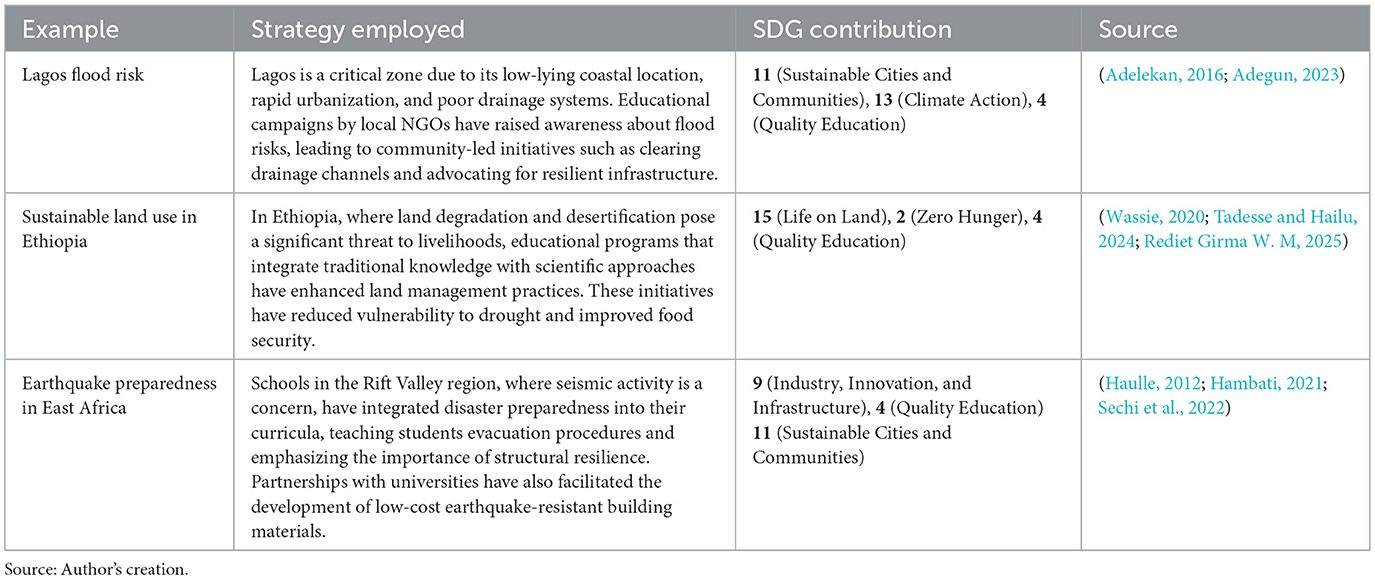

Table 3 synthesizes three African case studies from Nigeria, Ethiopia, and the East African Rift Valley, illustrating how SDGs 4 and 9 are operationalised locally to enhance resilience and community adaptive capacities. These cases reveal both progress and persistent challenges in integrating DRR with education and infrastructure development. As demonstrated in Table 3, fragmented institutional frameworks in many African countries hinder coordinated disaster risk education and resilience-building efforts, necessitating stronger policy alignment and cross-sector collaboration (Zembe et al., 2022).

In Lagos, Nigeria, urban flood resilience initiatives provide a compelling example of how disaster risk reduction can be localized to advance multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 4 (Quality Education). Community-led early warning systems and public education campaigns have effectively bridged scientific data with grassroots knowledge, enhancing preparedness in ecologically vulnerable urban environments (Adelekan, 2020). Similarly, in Ethiopia, integrated dryland restoration programmes are simultaneously addressing environmental degradation and socio-economic vulnerability by aligning with SDG 15 (Life on Land), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 4. These initiatives blend indigenous ecological knowledge with agroecological training to restore degraded landscapes, improve food security, and strengthen adaptive learning capacities (Tadesse and Hailu, 2024).

A third case in the seismically active Rift Valley illustrates how education, science, and innovation can jointly advance disaster resilience and inclusive development. Here, the integration of disaster risk reduction (DRR) into school curricula and the local production of cost-effective, earthquake-resistant construction materials have supported the goals of SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 4, and SDG 11. This approach exemplifies how context-responsive education and local innovation can mitigate disaster risks while fostering sustainable development (Mwangi and Njoroge, 2023; United Nations, 2015).

Taken together, these case studies affirm the imperative for a holistic, place-based, and context-sensitive approach to sustainable development, one that addresses structural poverty, strengthens educational systems, promotes technological innovation, and embeds disaster resilience within both policy frameworks and everyday community practices.

4.8 The role of education in understanding the creation of disasters

Disasters are not merely natural events, but are a result of vulnerabilities created by socioeconomic conditions, such as poverty, inequality, and inadequate governance. Critical zones are areas where these vulnerabilities often converge with hazards, resulting in disproportionate impacts on marginalized communities (Torani et al., 2019; Cerulli et al., 2020). Disasters are usually anthropogenic in origin, stemming from socio-political decisions that increase vulnerability, such as deforestation, poor urban planning, and inadequate infrastructure, which can amplify the impact of floods and landslides (McGlade et al., 2019). Thus, education is critical for reducing disaster risks by fostering awareness and building capacity for proactive mitigation. Hence, integrating disaster risk science into school curricula and community education programs enhances resilience at all levels (Mutasa and Coetzee, 2019). Countries like South Africa have legislated education-based capacity development programmes, such as the one initiated in 2010, where the National Disaster Management Center conducted a National Education, Training, and Research Needs and Resources Analysis (NETaRNRA) (National Disaster Management Centre, 2010). The NETaRNRA is a foundation for developing appropriate disaster management training and education programmes responsive to changing risk conditions (Republic of South Africa, 2005). Furthermore, in 2022, the NDMC commenced a new programme termed “National Research Agenda”. It brings together all the higher education institutions and other stakeholders offering DRR education to ensure that DRR education and research are conducted uniformly (Department of Cooperative Governance, South Africa, 2022).

Disparities in access to education, resources, and opportunities also increase vulnerability in critical zones. For instance, rural communities in Africa often lack the necessary infrastructure and knowledge to prepare for and respond to hazards, leaving them disproportionately vulnerable. As climate change intensifies the frequency and severity of hazards, while urbanization concentrates populations in critical zones, education systems must adapt to address these interconnected challenges through curricula that emphasize sustainability and resilience.

4.9 Intersecting vulnerabilities

Intersecting vulnerabilities refers to how multiple factors combine and interact to create hardships that are far greater than the sum of each factor (Vázquez et al., 2020). Each factor amplifies the effects of the others, therefore leading to more severe experiences of vulnerability. Critical zones, which interplay natural processes and anthropogenic actions, significantly influence environmental and social resilience (Pescaroli and Alexander, 2018; Cutter, 2009). Their complex dynamics are exposed to climate variability, environmental degradation, and socioeconomic pressures. River basins, such as the Nile and Zambezi, exemplify the intricate relationships between land use, water quality, and disaster risks. Runoff from Agricultural activities, laden with fertilizers and pesticides, leads to eutrophication, reducing water quality and disrupting aquatic ecosystems (Chawanda et al., 2024; Cutter, 2012). Additionally, sedimentation caused by deforestation and poor agricultural practices increases the likelihood of flooding, disproportionately affecting marginalized communities with limited adaptive capacities (Afele et al., 2022). These dynamic processes are induced by climate change, which intensifies rainfall variability and heightens the risks of both droughts and floods in these critical zones.

Coastal regions, which host high activity such as tourism, fisheries, and port operations, are highly vulnerable to storm surges, coastal erosion, and sea-level rise. For example, in East and West Africa, the erosion of sandy beaches poses a threat to biodiversity and the livelihoods of coastal communities that rely on tourism and fishing industries (Ideki and Ajoku, 2024). The impact of storm surges is compounded by unplanned urbanization and inadequate coastal management strategies, leaving infrastructure and communities increasingly exposed to extreme weather events (Cissé et al., 2024).

Mountain regions are characterized by fragile ecosystems that are highly susceptible to landslides, often triggered by deforestation, mining activities, and heavy rainfall. These landslides pose a severe risk to nearby communities and infrastructure, disrupting transportation networks and isolating rural populations from critical services (Depicker et al., 2021). Moreover, the degradation of mountain forests reduces their capacity to regulate water cycles, which can trigger downstream flooding in adjacent lowlands. Critical zones illustrate the interdependence between environmental health and human activities. Addressing vulnerabilities in these areas requires an integrated approach that combines sustainable land-use practices, disaster risk reduction strategies, and robust policy frameworks. Such interventions are vital for safeguarding ecosystems, enhancing community resilience, and promoting sustainable development in regions disproportionately affected by the cascading effects of environmental and socioeconomic challenges.

4.10 Disaster risk education and sustainable development

Over the decades, Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) has moved from a narrowly perceived technical discipline to a broad-based global movement focused on sustainable development. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that killed 2,30,000 people served as a catalyst that convinced many skeptics of the importance of DRR. In 2015, policymakers and practitioners from 168 countries congregated at Hyogo, Japan, and adopted the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) 2005-2015: Building the resilience for Nations and Communities to Disasters. However, HFA had many shortcomings compared to its successor, the Sendai Framework for DRR (2015-2030). The Sendai Framework for DRR (2015-2030) (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015) is more far-reaching, holistic, and inclusive. It emphasizes the need to address disaster risk management, reduce existing vulnerability, and prevent the creation of new risks. It emphasizes the importance of education as a pivotal tool in addressing the root causes of disasters by fostering awareness, skills, and community action.

Integrating disaster risk science into curricula helps individuals and communities understand the dynamics of critical zones and take proactive measures. Incorporating disaster risk science into African education systems enhances understanding of disaster causation, critical zones, and sustainable practices. This includes teaching concepts such as land-use planning, ecosystem services, and climate adaptation. In Mozambique, schools in flood-prone areas have adopted disaster preparedness programs that teach students evacuation procedures and risk mapping, and thus, this significantly reduced casualties during Cyclone Idai (Buechner, 2023). Integrating Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) in Rwanda into secondary school curricula has empowered students to participate in reforestation and soil conservation projects, mitigating landslide risks in the Northern Province. Rapid urbanization in Africa has increased vulnerability in critical zones, with informal settlements often located in high-risk areas. Education plays a role in empowering urban populations in advocating for safer housing and infrastructure. Climate change amplifies risks in critical zones, such as desertification in the Sahel and rising sea levels in coastal zones. Thus, education systems must prioritize climate literacy to enable communities to adapt to these changes. However, Inequalities in education also exacerbate disaster vulnerability. This explains why marginalized groups often lack access to the information and resources needed to mitigate risks and are more vulnerable. Thus, bridging this gap requires targeted interventions, such as inclusive disaster education programs.

4.11 Disaster risk science: key principles and relevance

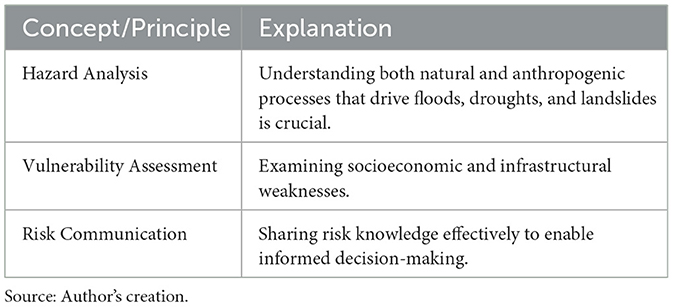

Disaster risk science encompasses the study of hazards in terms of vulnerability, exposure, management, and coping mechanisms. It integrates interdisciplinary approaches in its efforts to reduce disaster impacts. Disaster Risk Science focuses on Hazard Analysis, Vulnerability Assessment, and Risk Communication. The demarcation of hazard analysis, vulnerability assessment, and risk communication as foundational domains of disaster risk science is empirically grounded in the canonical risk equation (R = H × V × E) and codified in contemporary international frameworks. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction defines risk as a function of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability, with communication prioritized in the Sendai Framework as essential for risk reduction. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Sixth Assessment Report similarly reinforces this integrated approach by attributing climate-related risks to the interplay of altered hazard patterns, shifting exposure, and socio-economic vulnerability. This reflects a long scholarly evolution from hazard-centered perspectives toward a socio-ecological framing, premised on the understanding that hazards only translate into disasters when intersecting with vulnerable populations (Estoque et al., 2023; Stalhandske et al., 2024).

Within this schema, vulnerability assessment has been firmly established as a distinct analytical pillar through comprehensive frameworks such as MOVE (Methods for the Improvement of Vulnerability Assessment in Europe), which formalizes multidimensional vulnerability across exposure, susceptibility, and lack of resilience, linking these directly to hazard processes and societal response (Birkmann et al., 2013).

Risk communication is included as a critical translational bridge that converts scientific assessment into protective policy and behavior. Evidence shows that technical information alone is insufficient without accounting for perception, cultural context, and trust. Recent scholarship demonstrates that communication failures exacerbate disaster impacts, while effective, audience-centered strategies enhance resilience and the functioning of early warning systems (Fathollahzadeh et al., 2023; Stewart, 2024).

Accordingly, the focus on hazard analysis, vulnerability assessment, and risk communication reflects a convergence in disaster risk science literature rather than authorial preference, ensuring a framework that is both conceptually robust and practically applicable, particularly in contexts such as informal settlements. The purposive selection of diverse disaster-prone African cases offers context-specific insights into these three core concepts of disaster risk science. When examining floods, droughts, cyclones, and compound events, the cases demonstrate how natural processes intersect with social and infrastructural vulnerabilities, while also exposing strengths and weaknesses in risk communication for disaster risk reduction. A summary of these disaster risk science concepts is provided in Table 4.

The implications of these concepts in the table extend to broader domains, including critical zones, education, and sustainable development. Critical zones where human and ecological systems interact require integrated hazard analysis and vulnerability assessments to safeguard ecosystems and livelihoods under climate stress (Gallina et al., 2016; Wisner et al., 2014). Education plays a central role in risk communication by building awareness, empowering communities with adaptive knowledge, and fostering a culture of preparedness (Stewart, 2024). Ultimately, embedding these approaches within sustainable development ensures that risk reduction is not an isolated practice but a driver of resilience, equity, and long-term environmental stewardship (Birkmann et al., 2013; Renn, 2020).

4.12 Education: a tool for risk reduction and sustainable development

Education fundamentally addresses the root causes of vulnerability by fostering awareness, enabling proactive action, and bridging theory with practical application. This dynamic synergy positions education and resilience-building as mutually reinforcing: education informs practice, while practice continuously refines educational approaches. To realize this symbiosis, DRR education must be systematically embedded across all levels of formal and non-formal learning systems. Mainstreaming DRR within national curricula from primary through tertiary education ensures resilience-building is cultivated as an intuitive, lifelong process (Perello-Marín et al., 2018). In formal education, DRR concepts can be progressively integrated, often without explicitly naming “disaster risk reduction” in early stages, thereby embedding resilience learning seamlessly into foundational knowledge (Koen et al., 2024; Ndabezitha et al., 2024).

In parallel, community-based education in informal and non-formal settings is essential for catalyzing behavioral change in climate adaptation and resilience. Grassroots programmes enhance understanding of critical zone vulnerabilities and equip educators, local leaders, and stakeholders with essential knowledge in risk science and environmental management (Cabello et al., 2021). Empirical evidence substantiates the effectiveness of such integrated educational strategies. In Botswana, experiential learning has successfully incorporated DRR themes into primary education, linking classroom instruction to lived community experiences and thereby deepening risk awareness and adaptive capacities (Mutasa and Coetzee, 2019). Similarly, Ghanaian teacher education programmes have begun integrating DRR content, with educators and curriculum developers acknowledging its critical importance despite resource constraints and limited formal guidelines (Apronti et al., 2015). The African Union Biennial reports since 2018, and Continental assessments reveal that although DRR and climate education receive regional endorsement, implementation across African countries remains fragmented and underfunded, underscoring a critical gap in scaling resilience education (Cabello et al., 2021).

Further illustrating this intersection, Tanzania's community programmes teaching sustainable farming and soil conservation practices have demonstrably reduced soil erosion in ecologically sensitive critical zones, linking environmental education with practical livelihood benefits (Kalonga et al., 2024). While peer-reviewed research remains limited in some areas, corroborating policy reports confirm these positive impacts, validating the transformative potential of integrating DRR with environmental science education [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2022].

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015) explicitly recognizes education as a critical enabler for reducing disaster risk and building resilient societies. It advocates for the integration of disaster risk knowledge across all education levels and emphasizes community participation in risk governance. The Framework's four priorities, understanding disaster risk, strengthening disaster risk governance, investing in DRR for resilience, and enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and recovery, are inherently linked to education and knowledge sharing (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2015; Kelman and Harris, 2021). When promoting inclusive education that incorporates indigenous knowledge systems and local experiences, the Sendai Framework aligns with calls for context-specific, culturally relevant learning that empowers vulnerable populations (Kelman, 2024).

Complementing the Sendai Framework, the UNESCO Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) Framework [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2022] foregrounds transformative learning that integrates environmental, social, and economic dimensions. This framework encourages the inclusion of critical zone concepts and disaster risk science within curricula to build adaptive capacity and foster sustainable behaviors at community levels. It stresses the importance of lifelong learning, community engagement, and the valorisation of indigenous and local knowledge to address socio-environmental vulnerabilities holistically [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2022; Green, 2024]. Additionally, the Critical Zone Observatories (CZO) network offers a scientific framework that highlights the importance of interdisciplinary research on the Earth's surface layer, where human and natural systems interact dynamically. Incorporating insights from CZOs into education systems promotes systems thinking and enhances understanding of local vulnerabilities and resilience opportunities within critical zones (Bales et al., 2017). This integrative approach aligns with the growing emphasis on bridging science, policy, and practice to foster sustainability in vulnerable landscapes (Paton, 2019).

Furthermore, emerging models such as the Integrated Disaster Risk Management and Sustainable Development Framework (IDRMSD) provide a holistic strategy to synchronize disaster risk science, environmental sustainability, and education. This framework advocates for multi-level governance, cross-sector collaboration, and participatory educational programmes tailored to local socio-ecological contexts, thereby enhancing resilience and adaptive capacity in critical zones (Gaegane, 2024; Zembe et al., 2022). Collectively, these frameworks and empirical insights affirm that advancing sustainable development, especially within Africa's ecologically and socially vulnerable critical zones, requires leveraging education both as a process and outcome of resilience-building. Embedding DRR, critical zone science, and sustainability education within formal curricula and community initiatives is foundational rather than optional. Education emerges not merely as an instrumental tool but as a transformative force reshaping vulnerability into adaptive capacity.

The conceptual model presented in Figure 1 illustrates the intersections between Disaster Risk Science (DRS), Critical Zones (CZ), and Education (E), and is strongly supported by the collective contributions of the studies listed in the table. Each study provides empirical and theoretical grounding for different aspects of the Venn diagram's overlapping domains, while also highlighting the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to disaster risk reduction (DRR). Latour (2020) systematic review on disaster risk creation establishes the critical connection between DRS and CZ by examining how socio-environmental processes in ecologically sensitive areas (Critical Zones) generate risk rather than merely respond to it (Latour, 2020). This aligns with broader disaster scholarship that emphasizes the need to integrate geophysical systems with human vulnerability frameworks (Cutter et al., 2008). Meanwhile, Lownsbery's (2025) meta-review of DRR education literature reinforces the DRS and E intersection by synthesizing how educational interventions translate disaster science into resilience-building practices (Lownsbery, 2025). Cabello et al. (2021) further expand this nexus by analyzing the tensions and synergies between DRR education and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), demonstrating how pedagogy bridges scientific knowledge and sustainability policy (Cabello et al., 2021).

Figure 1. Presents a comprehensive analysis of this intersection, illustrating the synergistic relationships between Disaster Risk Science, Critical Zones, and Education, and highlighting pathways through which integrated educational frameworks can strengthen resilience and sustainable development. The Intersection of Disaster Risk Science, Critical Zones, and Education. Source: Author's creation.

The CZ and E overlap, though less explicitly addressed in the table, is implicitly supported by Aghaei et al. (2018), who examine global strategies for DRR education, including place-based learning in high-risk environments (Aghaei et al., 2018). Vasileiou et al. (2022) further strengthen this linkage by advocating for the integration of Indigenous and local knowledge with scientific DRR frameworks, particularly in education and early-warning systems (Vasileiou et al., 2022). This echoes Gruenewald's (2003) theory of place-conscious education, which argues for curricula that embed ecological and cultural context into disaster preparedness (Gruenewald, 2003). The central convergence of DRS, CZ, and E is validated by Rezvani et al. (2023), whose systematic review on urban resilience demonstrates how GIS-based decision tools (DRS) must incorporate ecological thresholds (CZ) and community education (E) to enhance adaptive capacity (Rezvani et al., 2023). Additionally, Albris and Clark (2020) highlight the necessity of bridging scientific knowledge and policy, emphasizing that effective DRR requires transdisciplinary collaboration across risk science, environmental systems, and participatory education (Albris and Clark, 2020). Bonfanti et al. (2023) further underscore this by examining how trust between communities and institutions mediates the uptake of DRR science, reinforcing the need for educational frameworks that foster dialogue between experts and local stakeholders (Bonfanti et al., 2023).

Collectively, these studies substantiate the Venn diagram's model, illustrating that disaster resilience necessitates the integration of technical hazard science (DRS), ecological and socio-spatial contexts (CZ), and knowledge dissemination (E). The table's sources not only validate each overlapping domain but also highlight gaps, such as the need for stronger policy-science interfaces (Albris and Clark, 2020) and trust-based community engagement (Bonfanti et al., 2023), which future interdisciplinary research must address. Researchers from the Kenya Meteorological Department and universities collaborated to link climate science, urban modeling, and public health outcomes (Oluchiri, 2025). This was in a region prone to flooding and waterborne diseases. Furthermore, Disaster risk science identifies hazards and vulnerabilities specific to critical zones, providing insights for interventions such as early-warning systems and ecosystem restoration.

This type of interdisciplinary approach contributes effectively to education for sustainable development. The CZ + E shows knowledge sharing and community resilience by educating communities about critical environments and promoting resilience and adaptive capacities. In their study on fostering food security and climate resilience through landscape restoration practices. Woldearegay et al. (2017) found that top-down approaches of implementing soil and water conservation practices contribute to limited adoption. Therefore, community-based participatory approaches were employed to educate and engage farmers in the Tigray region, resulting in improved agricultural productivity and resilience to drought and flood events. The intersection between DRS + E is systematic risk reduction, emphasizing the role of education in understanding and reducing systematic disaster risks. Additionally, education ensures that knowledge from disaster risk science is disseminated to communities, thereby fostering informed action and policy development.

The diagram also shows a central intersection, bringing together DRS+CZ+E, which represents knowledge sharing and community resilience, and suggests that true resilience and sustainable risk reduction can emanate from combining science, understanding the environment, and education. Moreover, the intersection enables systemic risk reduction by combining scientific analysis, ecological understanding, and community education to build resilience at multiple scales. The intersection of disaster risk science, critical zones, and education is a crucial nexus for fostering sustainable development, particularly in vulnerable regions such as Africa. It emphasizes knowledge sharing and community resilience, thereby empowering communities to act and adapt effectively.

5 Conclusion

The integration of Critical Zones, Disaster Risk Science, and Education for Sustainable Development forms a vital, unified framework essential for addressing disaster vulnerabilities and fostering sustainable livelihoods in African contexts. The interdisciplinary nexus not only advances knowledge sharing but also nurtures adaptive capacities at individual, community, and institutional levels. Empirical evidence from across Africa suggests that integrating disaster risk reduction and environmental stewardship enhances community resilience and promotes sustainable development. When combining scientific insights, ecological understanding, and participatory education, Africa can effectively reduce systemic risks and support vulnerable populations in adapting to environmental challenges. Ultimately, education emerges not merely as a tool but as a transformative process integral to sustainable risk governance and ecological preservation.

Recommendations

To strengthen resilience and sustainability, disaster risk reduction (DRR) should be systematically mainstreamed into education systems by embedding it in curricula at all levels from early childhood to tertiary education through the use of context-specific teaching materials that integrate ecological stewardship, resilience, and sustainable development. Teacher training requires targeted investment, with DRR, Critical Zones, and sustainability concepts incorporated into pre-service education and reinforced through continuous professional development to enable educators to facilitate participatory and practice-based learning. Equally important is the promotion of community-based education, which relies on participatory platforms that engage local leaders, youth, and vulnerable groups in identifying risks and co-developing solutions, using culturally relevant approaches that reflect local realities. Institutional collaboration must also be enhanced by building strong partnerships between schools, universities, disaster management agencies, and policymakers, underpinned by joint frameworks for research, training, and policy support to advance multi-level governance of disaster risk. At the same time, digital and technological innovations such as GIS, mobile applications, and artificial intelligence should be leveraged to improve early warning systems, knowledge sharing, and risk communication, supported by open-access platforms that provide resources for communities, educators, and policymakers. Finally, embedding DRR and sustainability education within national development strategies and mobilizing civil society organizations as partners in outreach and community-driven initiatives is essential to ensure long-term impact and policy coherence.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

WL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. CM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. OK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. ST: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adegun, O. B. (2023). Flood-related challenges and impacts within coastal informal settlements: a case from Lagos, Nigeria. Int. J. Urban Sust. Dev. 15, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2022.2159415

Adelekan, I. O. (2016). Flood risk management in the coastal city of Lagos, Nigeria. J. Flood Risk Manag. 9, 255–264. doi: 10.1111/jfr3.12179

Adelekan, I. O. (2020). Urban dynamics, everyday hazards and disaster risks in Ibadan, Nigeria. Environ. Urban. 32, 213–232. doi: 10.1177/0956247819844738

Afele, J.T., Nimo, E., Lawal, B., and Afele, I. K. (2022). Deforestation in Ghana: evidence from selected Forest Reserves across six ecological zones. Int. J. For. Anim. Fish. Res. 6, 7–17. doi: 10.22161/ijfaf.6.1.2

Aghaei, N., Seyedin, H., and Sanaeinasab, H. (2018). Strategies for disaster risk reduction education: a systematic review. J. Educ. Health Prom. 7:98. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_31_18

Albris, K., and Clark, N. (2020). In the interest(s) of many: governing data in crises. Polit. Gov. 8, 456–468. doi: 10.17645/pag.v8i4.3110

Apronti, P. T., Osamu, S., Otsuki, K., and Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. (2015). Education for disaster risk reduction (DRR): linking theory with practice in Ghana's Basic Schools. Sustainability 7, 9160–9186. doi: 10.3390/su7079160

Arènes, A. (2021). Inside the critical zone. GeoHumanities 7, 131–147. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2020.1803758

Aurélien, A. B. (2025). Vulnerability to climate change in sub-Saharan Africa countries. Does international trade matter? Heliyon. 11:e42517. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42517

Bales, R. C., White, T., Brantley, S., Banwart, S., Chorover, J., Dietrich, W. E., et al. (2017). “The role of critical zone observatories in critical zone science,” in Developments in Earth Surface Processes [Online] (Elsevier), 15–78. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63369-9.00002-1

Berg, A., and Sheffield, J. (2018). Climate change and drought: the soil moisture perspective. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 180–191. doi: 10.1007/s40641-018-0095-0

Biasutti, M. (2019). Rainfall trends in the African Sahel: characteristics, processes, and causes. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 10:e591. doi: 10.1002/wcc.591

Biermann, F. (2014). Earth System Governance: World Politics in the Anthropocene. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Birkmann, J., Cardona, O. D., Carreño, M. L., Barbat, A. H., Pelling, M., Schneiderbauer, S., et al. (2013). Framing vulnerability, risk, and societal responses: the MOVE framework. Nat. Hazards 67, 193–211. doi: 10.1007/s11069-013-0558-5

Birkmann, J., Jamshed, A., McMillan, J. M., Feldmeyer, D., Totin, E., Solecki, W., et al. (2022). Understanding human vulnerability to climate change: a global perspective on index validation for adaptation planning. Sci. Tot. Environ. 803:150065. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150065

Black, G. F., Petersen, L., Mpofu-Mketwa, T. J., Dick, L., Wilson, A., Ncube, S., et al. (2025). Participatory visual methods and the mobilization of community knowledge: working towards community-derived disaster risk management in the context of advancing climate change. J. Particip. Res. Methods 6, 121–152. doi: 10.35844/001c.129834

Bonfanti, R. C., Oberti, B., Ravazzoli, E., Rinaldi, A., Ruggieri, S., and Schimmenti, A. (2023). The role of trust in disaster risk reduction: a critical review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 21:29. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21010029

Buechner, M. (2023). Climate-Proof Schools in Mozambique: Climate Adaptation That Works. UNICEF USA. Available online at: https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/climate-proof-schools-mozambique-climate-adaptation-works (Accessed June 1, 2025).

Burton, I., Kates, R. W., and White, G. F. (1993). The Environment as Hazard, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Byiringiro, F. V., Jolivet, M., Dauteuil, O., Arvor, D., and Hitimana Niyotwambaza, C. (2024). Exceptional cluster of simultaneous shallow landslides in Rwanda: context, triggering factors, and potential warnings. GeoHazards 5, 1018–1039. doi: 10.3390/geohazards5040049

Cabello, V. M., Véliz, K. D., Moncada-Arce, A. M., Irarrázaval García-Huidobro, M., and Juillerat, F. (2021). Disaster risk reduction education: tensions and connections with sustainable development goals. Sustainability 13:10933. doi: 10.3390/su13191093

Carver, T. (2020). “Interpretative methods,” in Interpretative Methods, Vol. 3, eds. D. Berg-Schlosser, B. Badie, and L. Morlino (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 406–422. doi: 10.4135/9781529714333.n27

Cerulli, D., Scott, M., Aunap, R., Kull, A., Pärn, J., Holbrook, J., and Mander, Ü. (2020). The role of education in increasing awareness and reducing the impact of natural hazards. Sustainability 12:7623. doi: 10.3390/su12187623

Chawanda, C. J., Nkwasa, A., Thiery, W., and van Griensven, A. (2024). Combined impacts of climate and land-use change on future water resources in Africa. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 117–138. doi: 10.5194/hess-28-117-2024

Cissé, C. O. T., N'Diaye, E. H., Diop, S., Dieng, A., and Samb, M. L. (2024). Derivation of coastal erosion susceptibility and socio-environmental implications on Senegal's sandy coast using GIS and remote sensing. Sustainability 16:7422. doi: 10.3390/su16177422

Cook, D. A., and West, C. P. (2012). Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Med. Educ. 46, 943–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04328.x

Creese, A., Washington, R., and Jones, R. (2019). Climate change in the Congo Basin: processes related to wetting in the December–February dry season. Clim. Dyn. 53, 3583–3602. doi: 10.1007/s00382-019-04728-x

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018) Qualitative Inquiry Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Cutter, C. M., Szczygiel, L. A., Jones, R. D., Perry, L., Mangurian, C., and Jagsi, R. (2023). Strategies to support faculty caregivers at U.S. medical schools. Acad. Med. 98, 1173–1184. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005283

Cutter, S. L. (2009). “Social science perspectives on hazards and vulnerability science,” in Geophysical Hazards: Minimizing Risk, Maximizing Awareness (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 17–30. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-3236-2_2

Cutter, S. L. (2012). “Vulnerability to environmental hazards,” in Hazards Vulnerability and Environmental Justice, ed. S. L. Cutter (London: Routledge), 71–82. doi: 10.4324/9781849771542

Cutter, S. L., Barnes, L., Berry, M., Burton, C., Evans, E., Tate, E., and Webb, J. (2008). A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob. Environ. Change 18, 598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013

David, J. O. (2024). Decolonizing climate change response: African indigenous knowledge in education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 9:1456871. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2024.1456871

Department of Cooperative Governance South Africa. (2022). National Disaster Risk Management Research Agenda 2023–2030. Available online at: https://onlinebursary.ndmc.gov.za/docs/ResearchAgenda.pdf

Depicker, A., Govers, G., Jacobs, L., Campforts, B., Uwihirwe, J., and Dewitte, O. (2021). Interactions between deforestation, landscape rejuvenation and shallow landslides in the North Tanganyika–Kivu Rift region, Africa. Earth Surf. Dyn. 9, 445–464. doi: 10.5194/esurf-9-445-2021

English, L. M., and Carlsen, A. (2019). Lifelong learning and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Probing the implications and the effects. Int. Rev. Educ. 65, 205–211. doi: 10.1007/s11159-019-09773-6

Estoque, R.C., Ishtiaque, A., Parajuli, J., Athukorala, D., Rabby, Y. W., and Ooba, M. (2023). Has the IPCC's revised vulnerability concept been well adopted?. Ambio 52, 376–389. doi: 10.1007/s13280-022-01806-z

Fathollahzadeh, A., Salmani, I., Morowatisharifabad Mohammad, A., Khajehaminian Mohammad-Reza, B., and Javad Fallahzadeh, H. (2023). Models and components in disaster risk communication: a systematic review. J. Loss Prevent. Process Indus. 86:105057. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_277_22

Gaegane, L. (2024). Incorporating sustainability into development plans in selected African cities. Sustainability 16:10493. doi: 10.3390/su162310493

Gallina, V., Torresan, S., Critto, A., Sperotto, A., Glade, T., and Marcomini, A. (2016). A review of multi-risk methodologies for natural hazards: consequences and challenges for a climate change impact assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 168, 123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.11.011

Green, L. (2024). Rock | Water | Life: Ecology and Humanities for a Decolonising South Africa. UCT Press.

Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). Foundations of place: a multidisciplinary framework for place-conscious education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 40, 619–654. doi: 10.3102/00028312040003619

Hambati, H. (2021). Invisible resilience: indigenous knowledge systems of earthquake disaster management in Kagera region, Tanzania. Utafiti 16, 247–270. doi: 10.1163/26836408-15020050

Harzing, A. W. (2025). “Everything you always wanted to know about research impact,” in How to Get Published in the Best Management Journals, eds. A. W. Harzing and S. Alakangas (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 117–131.

Haulle, E. (2012). Evaluating earthquake disaster risk management in schools in Rungwe volcanic province in Tanzania. Jàmbá J. Dis. Risk Stud. 4:44. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v4i1.44

Ideki, O., and Ajoku, O. (2024). Scenario analysis of shorelines, coastal erosion, and land use/land cover changes and their implication for climate migration in East and West Africa. J. Marine Sci. Eng. 12:1081. doi: 10.3390/jmse12071081

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Available online at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Kalonga, J. S., Massawe, B., Kimaro, A., and Mtei, K. (2024). Community perception of land degradation across Maasai landscape, Arusha Tanzania: implication for developing a sustainable restoration strategy. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 102, 208–223. doi: 10.21608/EJAR.2024.263444.1500

Kawasaki, A., and Rhyner, J. (2018). Resilient infrastructure for disaster risk reduction. Nat. Hazards, 91, 211–227.

Kelman, I. (2020). Disaster by Choice: How Our Actions Turn Natural Hazards Into Catastrophes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kelman, I. (2024). “Visualizing disaster risk reduction to inspire positive action,” in Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, Vol. 66, 37–44. Available online at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00139157.2024.2395798

Kelman, I., and Harris, M. (2021). Linking disaster risk reduction and healthcare in locations with limited accessibility: challenges and opportunities of participatory research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:248.

Koen, T., Coetzee, C., Kruger, L., and Puren, K. (2024). Assessing the integration between disaster risk reduction and urban and regional planning curricula at tertiary institutions in South Africa. J. Transdiscipl. Res. Southern Africa 20:a1451. doi: 10.4102/td.v20i1.1451

Kunguma, O., and Mapingure, T. (2023). Review of disaster management training: a case study of a South African university. Jamba 15:1342. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v15i1.1342

Latour, B. (2020). “Seven objections against landing on Earth,” in Critical Zones: The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth, eds. B. Latour and P. Weibel (Cambridge: MIT Press), 10–17.

Lownsbery, D. S. (2025). A synthesis review of four literature reviews of disaster risk reduction education for children. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2025.105555

Machi, L. A., and McEvoy, B. T. (2023). The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Mbah, M. F., and Liberty, C. (2025). “Why education matters for a climate-resilient Africa,” in Practices, Perceptions and Prospects for Climate Change Education in Africa, eds. M. F. Mbah, P. Molthan-Hill, and E. L. Molua (Cham: Springer Nature), 19–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-84081-4_2

McGlade, J., Bankoff, G., Abrahams, J., Cooper-Knock, S. J., Cotecchia, F., Desanker, P., et al. (2019). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction 2019. Geneva: UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

Moges, D. M., Kmoch, A., Bhat, H. G., and Uuemaa, E. (2020). Future soil loss in highland Ethiopia under changing climate and land use. Reg. Environ. Change 20:32. doi: 10.1007/s10113-020-01617-6

Mongeon, P., and Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of web of science and scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106, 213–228. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Mpiere, D., Tehami, K., Coulibaly, I., and Mbaiogaou, C. (2025). Assessing the integration of the Sendai framework, sustainable development goals, and the Paris agreement in advancing disaster risk reduction and sustainable development: insights from an African perspective. J. Geosci. Environ. Protect. 13, 350–368. doi: 10.4236/gep.2025.137021

Mugari, E., Nethengwe, N. S., and Gumbo, A. D. (2025). A co-design approach for stakeholder engagement and knowledge integration in flood risk management in Vhembe district, South Africa. Front. Clim. 7:1517837. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2025.1517837

Muir, G., and Opdyke, A. (2024). Deconstructing disaster risk creation discourses. Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 111:104682. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2024.104682

Mulomba Mukendi, C., and Choi, H. (2024). Temporal analysis of world disaster risk: a machine learning approach to cluster dynamics. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2401.05007

Mutasa, S., and Coetzee, C. (2019). Exploring the use of experiential learning in promoting the integration of disaster risk reduction into primary school curriculum: A case of Botswana. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 11:a416. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v11i1.416

Mwalwimba, I. K., Manda, M., and Ngongondo, C. (2024). The role of indigenous knowledge in disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation in Chikwawa, Malawi. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 16:a1810. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v16i2.1810

Mwangi, T., and Njoroge, J. (2023). Innovations in earthquake-resistant construction in East Africa. Int. J. Dis. Sci. 22, 99–113.

National Disaster Management Centre (2010). National Education, Training, and Research Needs and Resources Analysis (NETaRNRA) - Consolidated Report. Available online at: http://www.ndmc.gov.za/Frameworks/05%20Consolidated%20Report.pdf (Accessed July 23, 2025).

Ndabezitha, K. E., Mubangizi, B. C., and John, S. F. (2024). Adaptive capacity to reduce disaster risks in informal settlements. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 16:a1488. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v16i1.1488

Nemakonde, L. D., Van Niekerk, D., Becker, P., and Khoza, S. (2021). Perceived adverse effects of separating government institutions for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation within SADC member states. Int. J. Dis. Risk Sci 12, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13753-020-00303-9

Nobambela, A., and Yekani, B. (2025). Complexity and effectiveness in disaster risk management within local municipalities. J. Local Govern. Res. Innov. 6:a269. doi: 10.4102/jolgri.v6i0.269

Oluchiri, S. O. (2025). Urban flooding in the cities of Kisumu, Mombasa, and Nairobi, Kenya: Causes, vulnerability factors, and management. Afr. J. Emp. Res. 6, 342–351. doi: 10.51867/ajernet.6.1.29

Paton, D. (2019). Disaster risk reduction: Psychological perspectives on preparedness. Aust. J. Psychol. 71, 327–341. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12237

Pelling, M., and Garschagen, M. (2019). Put equity first in climate adaptation. Nature 569, 327–329. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-01497-9

Perello-Marín, M. R., Ribes-Giner, G., and Pantoja Díaz, O. (2018). Enhancing education for sustainable development in environmental university programmes: a co-creation approach. Sustainability 10:158. doi: 10.3390/su10010158

Pescaroli, G., and Alexander, D. (2018). Understanding compound, interconnected, interacting, and cascading risks: a holistic framework. Risk Anal. 38, 2245–2257. doi: 10.1111/risa.13128

Petticrew, M., and Roberts, H. (2008). Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Raphela, T. D., and Matsididi, M. (2025). The causes and impacts of flood risks in South Africa. Front. Water 6:1524533. doi: 10.3389/frwa.2024.1524533

Rediet Girma, W. M. (2025). Assessment of land degradation neutrality to guide sustainable land management practices in Ethiopia. Environ. Challeng. 19:101137. doi: 10.1016/j.envc.2025.101137

Renn, O. (2020). “Risk communication: Insights and requirements for designing successful communication programs on health and environmental hazards,” in Handbook of risk and Crisis Communication (New York, NY: Routledge), 80–98. doi: 10.4324/9781003070726-5

Rezvani, S. M., Falcão, M. J., Komljenovic, D., and de Almeida, N. M. (2023). A systematic literature review on urban resilience enabled with asset and disaster risk management approaches and GIS-based decision support tools. Appl. Sci. 13:2223. doi: 10.3390/app13042223

Ridley, D. (2023). The Literature Review: a Step-By-Step Guide for Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Sechi, G. J., Lopane, F. D., and Hendriks, E. (2022). Mapping seismic risk awareness among construction stakeholders: the case of Iringa (Tanzania). Int. J. Dis. Risk Reduct. 82:103299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103299

Sherman, G. (2022). Socio-economic resilience of natural resource dependent communities. The University of Maine. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3657

Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 104, 333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

Stalhandske, Zélie, Steinmann, C. B., Meiler, S., Sauer, I. J., Vogt, T., Bresch, D. N., and Kropf, C. M. (2024) Global multi-hazard risk assessment in a changing climate, Sci. Rep. 14:5875. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-55775-2

Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O., and Ludwig, C. (2018). The trajectory of the Anthropocene: the Great Acceleration. Anthrop. Rev. 2, 81–98. doi: 10.1177/2053019614564785

Stewart, I. S. (2024) Advancing disaster risk communications. Earth Sci. Rev. 249:104677. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2024.104677.