- 1Rabdan Academy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 2American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Introduction: This study investigates faculty perceptions of discourses associated with assessment moderation at a higher education institution in the UAE.

Methodology: This study employed a survey incorporating closed- and open-ended components. Adie and her associates' (2013) framework of assessment moderation discourses was used as an analytical framework for qualitative data with the purpose of identifying the discourses faculty associate with the purposes of assessment moderation practice at the target institution.

Results: The findings revealed community building as the most dominant discourse among faculty responses. Significantly, the study identified a fifth discourse category extending beyond the existing four-category framework: faculty resistance characterized by minimal or negligible valuation of assessment moderation practices. Approximately 25% of respondents questioned the fundamental pedagogical or institutional value of assessment moderation, suggesting theoretical gaps in current frameworks that assume universal acceptance of moderation principles.

Discussion: These findings advance assessment moderation theory by identifying a distinct faculty discourse characterized by the perception of minimal or negligible value in the moderation process. The study demonstrates that theoretical frameworks developed in Western educational contexts require substantial adaptation for diverse cultural and institutional settings. The research has significant implications for policy development and implementation of assessment moderation practices in higher education environments, highlighting the need for culturally responsive approaches to quality assurance in global academic settings.

Introduction

Assessment moderation is a quality assurance measure designed to promote the trustworthiness and credibility of high-stake assessments (Beutel et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2023). A quick review of the relevant literature indexed in Scopus and Web of Science databases reveals that a vast majority of the literature on assessment moderation originates from three jurisdictions: Australia, New Zealand, and the UK, suggesting that assessment moderation is not prevalent in other parts of the world. This observation demonstrates congruence with the comprehensive literature synthesis conducted by Prichard et al. (2024), which examined assessment moderation protocols within tertiary educational institutions and revealed a significant geographical concentration of empirical investigations predominantly emanating from Australian and British academic contexts. While being limited, the literature on assessment moderation offers contentious positions on its impact, motives, and sustainability (e.g., Adie, 2022; Beutel et al., 2017; Bloxham, 2009; Prichard et al., 2024; Williams et al., 2023). Within this scholarly discourse, one conceptual framework has gained prominence in investigating faculty perceptions of the values and purposes associated with assessment moderation. Adie et al. (2013) propose a typology of four broad discourses associated with the purposes of assessment moderation covering equity, community building, accountability, and justification. This paper examines the applicability of this framework in a context where assessment moderation is a relatively new practice. As such, the question this research is attempting to answer is, “what discourses do faculty members have in relation to the purposes of assessment moderation?”

To achieve its objective, this paper investigates the values associated with assessment moderation as seen by a diverse group of faculty members in the context of the UAE, where assessment moderation became a requirement for all academic institutions only in 2019 with the release of the then-new standards for program accreditation and institutional licensure. There are no studies focusing on how the introduction of this requirement has affected faculty experiences or the quality of education in a country where 90% of its faculty population is of diverse non-UAE background (MoE, 2023). As such, this paper has the potential of providing insights (i) to policy makers in the UAE on how to better position assessment moderation in ways that serve its announced goals and (ii) to countries and institutions where assessment moderation is not a common practice on how the introduction of assessment moderation is likely to affect faculty experience and the quality of assessment, especially when faculty members are of diverse cultural background as in the UAE.

This paper starts with providing a discussion of the literature around assessment moderation, its purpose, and associated values. This is followed by outlining the context and the research method for this study. Analysis of faculty responses to a survey and a discussion of faculty perceptions are provided in the next section. Before concluding, this paper outlines its contributions to the evolving theory and practice associated with assessment moderation.

It is hoped that the findings from this paper will expand our knowledge of assessment moderation practices, thereby helping inform future policy developments locally and beyond.

Literature review

In their comprehensive review of recent scholarly contributions to assessment and feedback in higher education, Jackel et al. (2017) establish the “defensibility of professional judgements” as a fundamental principle underpinning quality assessment and student learning (p. 21). One approach to achieving this defensibility lies in requiring a form of moderation for judgements made by assessors (Bloxham et al., 2016). Assessment moderation, a problematic development in higher education (Bloxham et al., 2016), emerged in response to the rapid rise of quality assurance practices driven by increasing demands for accountability and transparency in academia (Ajjawi et al., 2021; Beutel et al., 2017; O'Leary and Cui, 2020; Watty et al., 2014). Conceptually, the literature points to several complementary definitions of assessment moderation. Beutel et al. (2017) contend that assessment moderation is a dialogical process between markers to discuss achievement and application of standards in relation to a grading decision on a student's performance. Similarly, Adie et al.'s (2013) define assessment moderation as “a practice of engagement in which teaching team members develop a shared understanding of assessment requirements, standards and the evidence that demonstrates differing qualities of performance.” Bloxham (2009, p. 212) further emphasizes that moderation serves as “a process for assuring that an assessment outcome is valid, fair and reliable and that marking criteria have been applied consistently.” Assessment moderation has evolved beyond its traditional emphasis on post-assessment processes designed to achieve inter-rater reliability in grade determination. Contemporary conceptualizations of moderation encompass a comprehensive framework that extends across the entire assessment lifecycle, incorporating pre-assessment design validation, calibration protocols for establishing shared understanding of task requirements and performance standards, external verification mechanisms, and systematic evaluation of overall assessment validity and reliability (Bloxham et al., 2016). The inclusion of moderation as a peer scrutiny activity in the assessment design phase represents a recent development in higher education (Bloxham et al., 2016). Contemporary assessment moderation practices take different forms, including double marking, external marking, peer scrutiny at the assessment design stage, and blind marking.

Despite its widespread practice in certain jurisdictions, Bloxham (2009) argues that assessment moderation requires rigorous research and empirical verification. A recent integrative review by Prichard et al. (2024) identified only 19 peer-reviewed articles addressing assessment moderation practices in higher education institutions between 2008 and 2023. Therefore, another contribution of this empirical paper is to add to the relatively limited body of recent literature on assessment moderation and its utility for faculty, students, and institutions.

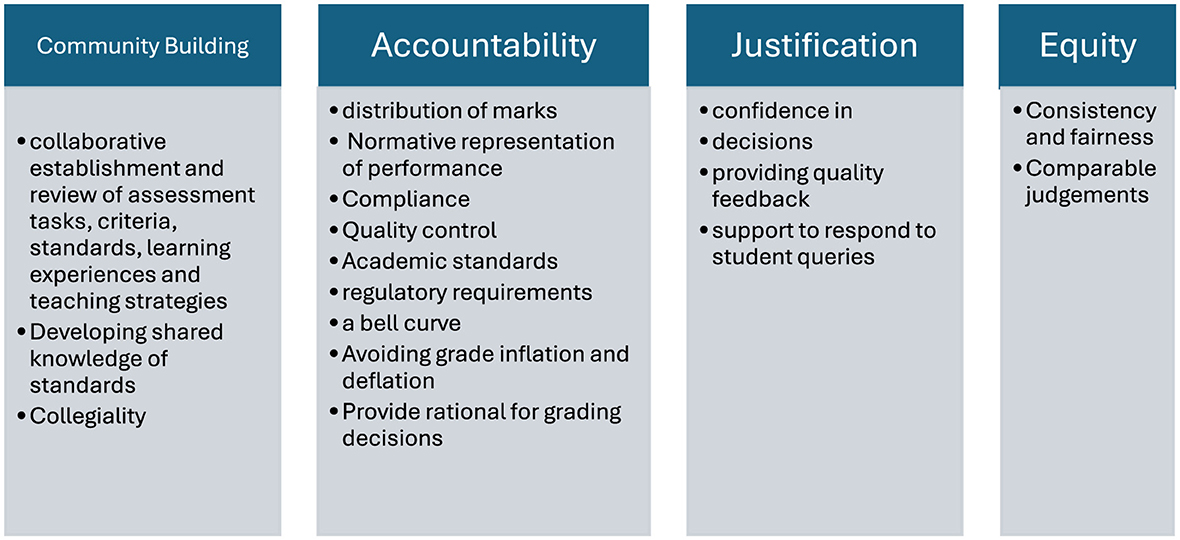

Within this relatively under-researched domain, Crimmins et al. (2016) outlines several significant potential benefits of assessment moderation, including the achievement of enhanced objectivity and fairness in marking, the improvement of teaching and marking practices, and the cultivation of collegiality and confidence among faculty. This multidimensional utility of assessment moderation is further elaborated in Tuovinen et al.'s (2015) research in four Australian academic institutions in which four main purposes associated with assessment moderation were identified: fairness and equity, quality assurance, comparability of assessments across boundaries, and learning. In their milestone study, Adie et al. (2013) propose a typology of four broad discourses associated with the purposes of assessment moderation as shown in Figure 1. They argue that the adoption of the term “discourse” is an acceptance of moderation as a social practice encompassing associated histories and cultural contexts. The proposed hermeneutic includes the discourses of equity, justification, community building, and accountability. Bloxham et al. (2016) argue that these discourses are not discreet in nature but are overlapping and interconnected. According to this framework, the equity discourse centers on ensuring fairness and consistency in both assessment design and evaluation process. Peer scrutiny, for example, has the potential of promoting equity during the assessment design phase by “ensuring that assessment tasks provide all students with equal opportunities to demonstrate their true standard of learning” (Bloxham et al., 2016, p. 642). The justification discourse addresses faculty's capacity to make confident assessment decisions and provide quality feedback to students. As Grainger et al. (2016, p. 554) observe, equity discourses are motivated by “a marker's desire to be able to publicly defend a grade to students … and to be comfortable with or convinced by the validity of their decision-making.” The community building discourse emphasizes the development of shared understanding among faculty regarding assessment standards through dialogue and collaboration. This discourse prioritizes collaboration in reviewing and establishing standards and building “the capacity to improve assessment design and inform teaching through discussion of issues and sharing of practice” (Bloxham et al., 2016, p. 641). From this perspective, assessment moderation functions as a peer learning activity that facilitates the development of shared understanding among faculty (Watty et al., 2014). Lastly, the accountability discourse focuses on the defensibility of assessment decisions in response to quality assurance measures. Under accountability, emphasis is placed on meeting regulatory and institutional requirements and outcomes (e.g., grade distributions). Importantly, Adie et al. (2013) argue that faculty perceptions of the purposes of assessment moderation may be a mix of one or more of these discourses.

Figure 1. Framework, discourses of assessment moderation (Adie et al., 2013).

This paper employs Adie et al. (2013) as a framework to analyze the discourses of faculty members at a UAE institution in relation to the purposes of assessment moderation. This framework is utilized in this study for one main reason: it offers an opportunity for institutions to reconcile accountability with faculty agency. While there is a plethora of literature on how the introduction of accountability measures have negatively impacted faculty experiences in higher education, this framework suggests that an institution may achieve a balance between discourses of accountability, a reality of today's academe, and faculty agency. Using this framework, institutional policy may be geared toward instituting assessment moderation practices as a means of providing opportunities for faculty members to engage with each other and learn (i.e., community building), achieve fairness for students (i.e., equity), while at the same time improving the defensibility of their decisions (i.e., justification) and satisfy regulatory requirements (i.e., accountability). In this sense, an institution answers Priestley et al. (2015) call for institutions to design policies that recognize educators' professionalism and enable them to achieve agency.

Assessment moderation, however, has not always received positive evaluation from faculty and researchers. Bloxham (2009) argues that the generated workload resulting from assessment moderation is not commensurate with the values attained from the activity. She believes that assessment moderation delays feedback given to students, constraints assessment choices, does not necessarily remove the inherent subjectivity of marking, may be problematized by power relations between senior and junior faculty, and may not add much to the reliability and accuracy of assessments. She recommends transferring the approach used by high school examination boards into higher education practices in order to improve the reliability and validity of assessment. After highlighting potential challenges with adopting high school standardized testing approaches, she recommends accepting the inherent subjectivity of professional judgement and shifting the focus from individual assessments to the overall profile of the individual student based on the series of marks obtained by that student. Along the same lines, Bloxham and Price (2015) question the underlying assumptions supporting external moderation as a safeguard for quality assessment. For example, they challenge the assumption that consensus on academic standards leads to a durable stability across programs. They argue that the expansion of higher education has led to a lack of understanding of the meaning of standards, hindering the ability to achieve comparability (p. 199). They add that standards comprise tacit and explicit knowledge which makes them elusive and “continuously co-constructed by academics” (p. 200). Similarly, Mason et al. (2022) found in a small scale study that assessment moderation promotes managerialism, power asymmetry dynamics, tension, and increased workload in higher education institutions. Similar findings are echoed in Mason et al. (2023). In a survey covering 380 academics, Goos and Hughes (2010) found that the accountability measures, such as assessment moderation, resulted in decreased confidence level among course coordinators, increased workload, and reduced sense of recognition.

Context and background

The study was undertaken at Muhra University, a pseudonym for a government-owned academic institution in the UAE, where English is the language of instruction. The institution introduced assessment moderation as a requirement for the first time in 2016 primarily to help improve the quality of its assessment practices and reduce the large volume of student appeals submitted on grounds of marking and assessment design errors. The first draft of the procedure was proposed in 2014; however, implementation was not actualized due to multiple institutional constraints, including administrative concerns regarding the potential augmentation of faculty workload allocation parameters. A modified version of the procedure was reproposed in 2015 limiting the moderated assessments to those whose weight exceeds 20% of the final grade. After implementing the procedure (starting Fall 2016), it was found that most assessments were re-weighted to be at 20% or less and therefore did not undergo assessment moderation. In December 2019, the CAA, the regulatory body of academic education in the UAE, introduced a new standard regulating providing guidance to academic institutions in the UAE to address “challenges for quality assurance and maintenance of high standards across the higher education sector” (CAA, 2019, p. 2). The standard document required moderation for all assessments for the first time. It requires all academic institutions to “implement methods for the moderation and assessment of student work in which more than one individual independently marks or moderates an assessment or evaluates student performance (p. 38). As a result of the new standard, the assessment moderation procedure was updated to require that all assessments be moderated, pre- and post-delivery.

The process followed by the institution at the time this survey was administered requires all assessments to undergo both pre- and post-delivery moderation. The process uses paper forms that faculty members transmit to each other through email. Both pre- and post-delivery assessment moderation require moderators to review assessment paperwork and provide written feedback. Once completed, the forms are shared with the program chair to provide any additional feedback or corrective actions. Where grades fall below or above certain boundaries, a third layer of assessment moderation is implemented, typically administered by the Assessment Section within the institution.

Research design and methodology

This case study was conducted at Muhra University in the UAE with the purpose of informing policy change and improving faculty experience in response to anecdotal feedback received from different individuals within faculty. Survey instrument development leveraged the authors' expertise in higher education assessment moderation. Following initial design, the survey was reviewed and improved by members of a faculty taskforce responsible for enhancing assessment moderation practices at the target institution. Subsequently, comprehensive pre-testing was conducted to establish validity and reliability (Ruel et al., 2015; Saunders et al., 2016). Face validity ensures items measure their intended constructs, while content validity confirms adequate coverage of research questions (Saunders et al., 2016). Reliability testing verifies instrument consistency and question clarity (Ruel et al., 2015). Expert-driven pre-testing also establishes construct validity by identifying measurement adequacy and linguistic issues (Ruel et al., 2015). The survey underwent expert review by three academic staff with publication records and survey design experience (Dillman et al., 2014). Individual debriefings followed pre-testing to enhance instrument validity and reliability (Ruel et al., 2015). Pre-testing confirmed: (1) face validity through participant verification of question and scale appropriateness; (2) content validity via confirmation of adequate research question coverage, with minor modifications incorporated based on participant suggestions (Saunders et al., 2016); and (3) linguistic accuracy through incorporation of participant feedback on wording and grammar.

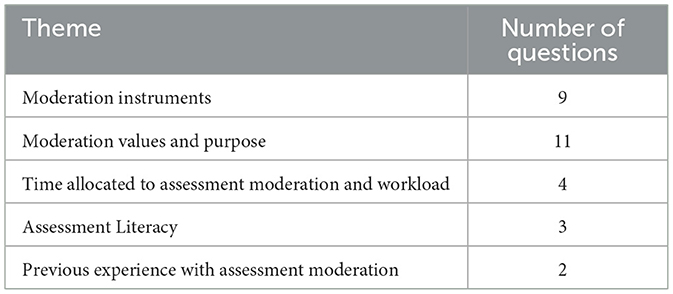

The final version of the survey, including closed- and open-ended components, was distributed to the entire teaching staff population of the target institution, about 100 individuals who come from 33 different nationalities. The number of those who responded to the survey was 74, which stands at about 73% of the target audience. Of the 74 respondents, 63 responded to the closed- and open-ended, while 9 responded only to the closed-ended component of the survey. The questions of the survey were designed to enable a critical evaluation of assessment moderation practices at the target institution and explore perceptions of the challenges associated with assessment moderation. Table 1 shows a summary of survey themes and the number of questions for each theme. The number of closed-ended questions was 14 (e.g., “On a scale of 1–5, how do you rate the impact assessment moderation practice has on your teaching quality/excellence?”), while the number of open-ended ones was 15 (e.g., “What value does the assessment moderation process have for you?”). The same theme could have open-ended questions as well as closed-ended ones in order to better understand the nature of responses provided by faculty members.

In order to obtain an answer for the question of this research, emphasis was placed on the eleven questions grouped under the theme “Moderation values and purpose”. Answers to other questions were used to corroborate conclusions reached from these eleven questions.

This paper utilizes quantitative and qualitative analysis of responses to the survey to measure faculty perception of and attitudes toward assessment moderation at the target institution. Following Braun and Clarke (2006) and Braun et al. (2016), thematic analysis was used to gain an understanding of the qualitative responses provided by faculty members. This method allows participants to become collaborators in the research effort (Braun and Clarke, 2006) and is robust in producing policy-focused research (Braun et al., 2016). On the other hand, quantitative data obtained from the survey was analyzed using R Studio. Adie et al.'s (2013) discourses of equity, accountability, community building, and justification were used as an analytical framework for qualitative data with the purpose of identifying the discourses faculty associate with the purposes of the current and desired assessment moderation practice at the target institution. The selection of this framework was driven by the data. After repeated reading of and reflection on qualitative responses to the survey to determine themes relating to the values faculty associate with assessment moderation, data was initially coded inductively without reliance on a predetermined theoretical framework. However, emerging patterns from initial coding aligned very closely with those identified by Adie et al. (2013). This alignment ultimately informed the development of the research questions and guided the analysis and subsequent discussion.

Prior to data collection, ethical approval was obtained from Lancaster University, the institution one of the authors is affiliated with as a postgraduate researcher.

Results

The data analysis presented in this section was derived from responses to six open-ended questions categorized under “Moderation Values and Purposes”. Supplementary data obtained from responses to additional questions was incorporated to substantiate arguments advanced in this section. Adie et al.'s (2013) discourses of equity, accountability, community building, and justification were employed as an analytical framework to guide the systematic analysis and discussion of the values faculty members associate with assessment moderation. Analysis of the data revealed that the four different discourses were prevalent in responses provided by faculty members and other professional academic staff. The discourse of community building demonstrated predominance manifesting in 123 responses, compared with 69 for equity, 53 for accountability, and 37 for justification.

Community building

The most common discourse that emerged from the data was that of moderation as a community building activity. This orientation appeared as a major theme in responses to questions asking faculty about both current and desired assessment moderation practice. In responding to the question, “What value does the assessment moderation process have for you?” thirty faculty members (or about 50% of those who provided responses to this question) expressed supportive views of moderation as a tool for community building, helping them promote collaboration, improve their assessment design and marking skills, exchange views, develop shared understanding, and facilitate their transition into the institution. As examples, faculty members provided responses 1–3 to the questions, “What value does the assessment moderation process have for you?” and “What should be the strategic objective of the moderation of assessments process?”

(1) [Assessment Moderation helps build] a better understanding of the needs and capabilities of the students. When I was new, I [got] to understand what to write and what not to write because of pre-moderation. I [got] to “see” where I need to improve courtesy of the suggestions of the moderator.

(2) [Assessment Moderation] promotes best practice through a collaborative process; for example, small team workshops where people are invited to give feedback on each other's assessment design in a group setting where everybody who participates presents their own material and provides feedback to others.

(3) [Assessment Moderation] helps me understand how well an assessment tool has worked through analysis of the grade distribution.

Faculty respondents demonstrated a pronounced emphasis on their professional development as competent members of the academic community through the formative feedback received from colleagues regarding their assessment practices. Emphasis was placed on the value of moderation as a tool promoting reflection, learning, accuracy, creativity, and innovation through dialogical interactions. Excerpts (1), for example, articulates how assessment moderation functions as a mechanism for professional socialization and pedagogical development, particularly for faculty members new to the institution. The respondent identifies moderation as instrument for developing nuanced understanding of student capabilities and needs—a form of tacit knowledge acquisition essential for effective assessment practice. The narrative emphasizes how pre-moderation processes facilitated the respondent's acculturation into institutional discourse practices (“what to write and what not to write”), suggesting moderation's role in transmitting implicit disciplinary and institutional norms. Furthermore, the respondent acknowledges the formative function of moderator feedback in identifying areas for professional growth, positioning moderation as a reflective practice that supports continuous improvement through collegial guidance. This perspective aligns with conceptualizations of assessment moderation as a vehicle for developing shared understanding of standards and expectations within academic communities. Excerpt (2), taken from responses to the question “What should be the strategic objective of the moderation of assessments process?”, underscores the critical role of assessment moderation as a dialogic and collaborative practice fostering collective refinement of assessment standards through structured mechanisms such as small-team workshops, where reciprocal feedback on assessment design democratizes the development of criteria. These processes not only enhance pedagogical alignment and equity but also serve as conduits for knowledge transfer and professional development, reinforcing institutional consistency in evaluation practices. In excerpt (3), a faculty member contends that assessment moderation as a current practice provides insights into the effectiveness of an assessment instrument through a reflection on grade distribution.

As part of highlighting the learning values associated with assessment moderation, faculty members repeatedly expressed their support of assessment moderation as a tool helping them through discussions improve the linguistic accuracy of assessment instruments. Therefore, assessment moderation could serve as a learning tool for both native and non-native speakers of English (O'Hagan and Wigglesworth, 2015). Faculty members also thought that improving the linguistic accuracy of questions leads to a reduced number of student appeals, which has the potential of improving student satisfaction.

Data shows that some faculty do not seem to view assessment moderation at the target institution as a tool that is primarily concerned with promoting collegiality among faculty. A supporting argument for this claim can be obtained from faculty responses to the question, “What should be the strategic objective of the moderation of assessments process?” where a few faculty members recommend restructuring the current process to make it more focused on building shared understanding among faculty. Additionally, nine faculty members who responded to a question asking about the challenges associated with assessment moderation contended that assessment moderation is highly subjective and as a result it leads to generating sensitivities among faculty. In excerpt (4), for example, a faculty member argues that some faculty tend to “weaponized” assessment moderation by using it to attack those who had given them negative feedback. This discourse is confirmed in faculty response to a quantitative question where 68% of faculty believed that assessment moderation may cause conflict with other faculty. Despite this belief, 77% of faculty believed that they freely provide feedback to other faculty.

(4) Dealing with the subjective comments of moderators especially those who lack expertise or have personal bias. Unfortunately, some moderators use it as a weapon to take revenge. You wrote a negative comment, I'll write an even more negative comment. Some other colleagues sadly use it to show off. They write irrelevant comments. They force their colleagues to change the whole assessment or rubric. Additionally, it all depends on who the moderator is. If the moderator does not like the grades or the assessment, he has the right not to sign the form!! This makes the assessment very subjective. I've seen this happen to my colleagues.

Equity

The second most common discourse that emerged from the data was that of moderation as an activity promoting equity. About 37% of faculty who provided a response to the question, “What criteria should an ‘ideal' moderation process seek to moderate/measure?” and 29% of the ones who responded to the question, “What should be the strategic objective of the moderation of assessments process?” believed that assessment moderation should help promote equity. This compares with 22% who believed that assessment moderation practice as is helps promote equity. This does not necessarily mean that the remainder of faculty felt that assessment did not promote equity. It only means that when faculty were asked about the values of moderation as is or as envisioned, they articulated that it helps promote equity. Nonetheless, it is clear from the data that the faculty who expressed that assessment moderation should promote equity are more than those who thought that current practice promotes equity (compare 22% with 37% and 29%). As an example, faculty members provided responses 4–6 to the questions, “What value does the assessment moderation process have for you?” and “In the current system, what value does the pre-moderation process confer to teaching quality/excellence?”

(5) The assessment moderation process is invaluable as it ensures … fairness of evaluations and assessments. By having multiple assessors review and compare assessments, potential biases or errors can be identified and corrected.

(6) Ensure that students' rights to their results are preserved.

(7) Fairness: The extent to which assessments are free from bias, discrimination, and unfair advantage, ensuring equal opportunities for all students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

Faculty members used the word fairness or its stem words (e.g., fair, fairly) in 38 instances to talk about the values associated with moderation. This word occurred the most in faculty responses to the questions, “What should be the strategic objective of the moderation of assessments process?” and “What criteria should an ‘ideal' moderation process seek to moderate/measure?” Synonyms of fairness also appeared (e.g., impartiality, justice, and equity) in a few responses. The second most occurring component of equity that appeared in the data was that of consistency. Faculty used the word consistency and reliability in about 20 instances. Excerpt (5) underscores moderation as a mechanism for equitable practice. The involvement of multiple assessors introduces diverse perspectives that interrogate hidden biases in assessment design or grading criteria. For instance, peer scrutiny can reveal whether tasks inadvertently privilege certain cultural or linguistic backgrounds, thereby disadvantaging marginalized students. Equity demands not only error correction but also proactive inclusivity—ensuring assessments are accessible to diverse learners. By collaboratively refining tasks, faculty mitigate structural inequities, aligning with equity's goal of leveling the playing field. Excerpts (6) and (7) operationalize equity as active inclusivity. Equity-driven moderation scrutinizes assessments for cultural relevance, language accessibility, and alignment with varied learning modalities (e.g., visual, kinesthetic). Peer dialogue during moderation can challenge assumptions about “standard” knowledge demonstrations, advocating for tasks that accommodate neurodiverse or multilingual students. Equity here is not passive fairness but intentional design—ensuring assessments do not systematically exclude or disadvantage groups (cf. Grainger et al., 2016; Hand and Clewes, 2000).

Faculty also spoke about equity as a tool for improving accessibility of assessment content to students. Following Cumming and Miller's (2023) work, equity—in the context of assessment—is not viewed as a tool that is achieved at the end of the assessment, instead it “permeates throughout the entire process” (p. 40). In talking about this component of equity, faculty believed that moderation helps ensure that students are not confused during the exam, ensure the clarity of instructions given to students, and individual differences of students are considered at the time of assessment design. In doing so, faculty members “ensure that tasks enable students to demonstrate outcomes” during the assessment design phase (Bloxham et al., 2016, p. 641).

Accountability

Another common theme that emerged from that data was that of moderation as a tool for accountability, which appeared in 52 responses to open-ended questions. Many faculty members thought that moderation assists them in complying with institutional and regulatory requirements. The most dominant subthemes under accountability were assessment validity and alignment with course learning outcomes (23 instances), compliance with institutional and regulatory requirements (13 instances), and grade distribution (4 instances). As an example, faculty members provided responses 7–9 to the questions, “What value does the assessment moderation process have for you?”; “In the current system, what value does the pre-moderation process confer to teaching quality/excellence?” and “In the current system, what value does the post-moderation process confer to teaching quality/excellence?”

(8) It appears that the current process is designed to create a tool to meet a regulatory requirement to support a quantitate measurement of an inherently qualitative action. The CLO Attainment sheet is designed to provide support for evaluating teaching quality and excellence. The way grades are produced is with assessments that provide some measure of student achievement and hence teaching quality. The moderation process is designed to produce a mixed means of evaluating and documenting the quality of the underlying assessment. The moderation process produces the necessary paperwork. Mission accomplished.

(9) Value is in adherence to technical institutional guidelines like course files, etc.

(10) The post-moderation process compels faculty members to adhere to a bell curve and manipulate grades or be subjected to intense scrutiny and criticism that, frankly, isn't worth the effort. The system punishes people for grading properly and enforces the normalization of marks around an arbitrary magic number range regardless of student performance in any given section of a course.

In excerpts (8), (9), and (10), faculty members speak negatively about assessment moderation owing to it being used as an accountability measure to comply with institutional and regulatory requirements such as grade distribution. However, a majority of faculty members spoke about accountability in a positive sense as supported by the appearance of accountability as a major theme in responses to questions, “What should be the strategic objective of the moderation of assessments process?” and “What criteria should an ‘ideal' moderation process seek to moderate/measure?” In responding to the first question 18% of responses thought that accountability should be a strategic objective for moderation while 20% of responses indicated that moderation should ideally measure accountability.

Some faculty members argued that moderation assists them in evaluating the distribution of grades across different sections of the same course or across the department. In excerpt (10), for example, the faculty member argued that the institution is requiring that faculty adhere to a bell curve. This interpretation of the policy can be seen as a discourse of accountability for grade distribution. In excerpt (3), however, the faculty member thought that grade distribution was a community building helping him/her understand how the assessment has worked considering grade distribution. In excerpt (14) [next section], the faculty member is arguing that moderation helps him/her justify grading by comparing a group with other groups from the same department.

Justification

The least recurring theme that emerged from the data was that of moderation as a means to justify faculty decisions. This was typified by responses indicating that moderation builds faculty confidence in making judgements in relation to student work, providing accurate feedback to students, and justifying results. As an example, faculty members provided responses 11–15 to the questions, “What value does the assessment moderation process have for you?” and “In the current system, what value does the pre-moderation process confer to teaching quality/excellence?” “What should be the strategic objective of the moderation of assessments process?” and “In the current system, what value does the post-moderation process confer to teaching quality/excellence?”

(11) It should help mitigate any grade inflation tendencies.

(12) Contribute to reviewing and verifying the correct entry of grades and reducing the burden of grievances.

(13) It's good to see where instruments across the faculty are resulting in very high/low grades have occurred and a discussion can then be had about why. This acts as an interrater reliability check across faculty.

(14) … benchmarking the class performance with others in same department.

(15) … the feedback is translatable to other assessments and personal to each student.

There were four main arguments emerging from the data in relation to the “justification” value of assessment moderation. First, faculty members thought that assessment moderation provides faculty with confidence in marking assessments by means of reducing marking and grading errors and validating their grades. In excerpt (12), for example, the faculty members are arguing that assessment moderation supports them in reviewing marks for accuracy. When errors are minimized, faculty confidence in their decisions increases, reducing the likelihood of grievances. This aligns with the need for equitable outcomes—students are less likely to contest grades perceived as fair and procedurally consistent. Second, faculty members utilize moderation as a tool to discuss grade inflation or deflation as shown in excerpt (11) and excerpt (13), supporting them in justifying their grading to the institution. Discussing extreme grade patterns (high/low) fosters consistency across markers, a cornerstone of justification. By aligning grading practices, faculty ensure assessments are reliable and comparable, enabling them to defend grades as products of shared standards. Third, faculty argued that assessment moderation helps improve the defensibility of their grading to students. For example, in excerpt (12) the faculty member is contending that assessment moderation helps him/her reduce the burden of student appeals. Finally, some faculty members believed that assessment moderation helps them in providing appropriate feedback to students. This is evident in excerpt (15), where the faculty is contending that moderation supports him/her in providing individualized feedback directly addressing student strengths/weaknesses, thereby validating the assessment's role in learning.

Little to no purpose discourse

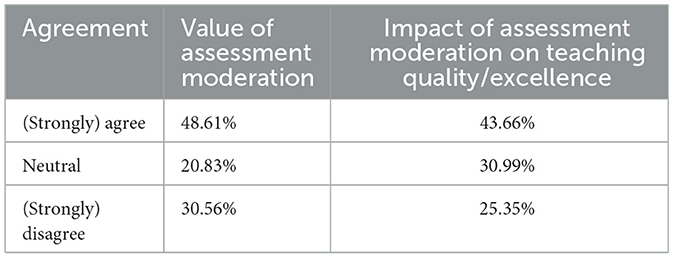

The findings revealed a fifth discourse category that extends beyond the four-category framework proposed by Adie et al. (2013). This additional category encompasses faculty perceptions characterized by minimal or negligible valuation of assessment moderation practices. As demonstrated in Table 2, this perspective is substantiated by the notable proportion of faculty respondents who expressed disagreement with key evaluative statements: 30% disagreed with “I see value in [the current] assessment moderation process,” while 25% disagreed with “assessment moderation has a positive impact on my teaching quality/excellence.” These results indicate a notable segment of the faculty population maintains skeptical attitudes toward the perceived utility and pedagogical benefits of institutional assessment moderation procedures.

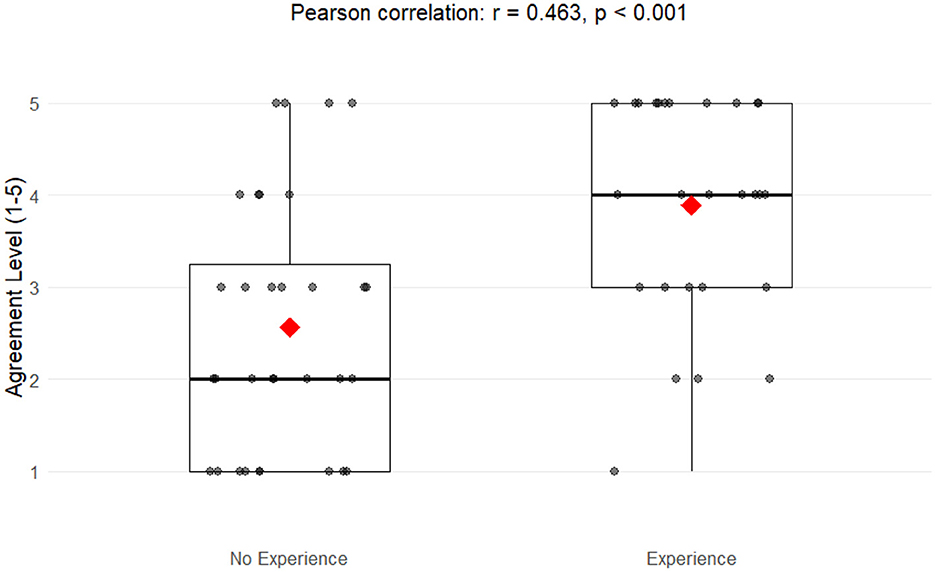

The data further shows that 34 faculty members (46% of respondents) indicated that they did not have assessment moderation as a practice before joining Muhra University. Cross-tabulation analysis of these respondents' evaluations regarding moderation utility revealed that 50% maintained negative perceptions toward assessment moderation protocols, 25% expressed neutral evaluative positions, while the remaining 25% demonstrated positive attitudinal orientations toward the institutional moderation framework. Deeper statistical analysis examined the relationship between faculty members' prior experience with assessment moderation and their perceptions of its value within the institutional context. Results revealed a statistically significant positive association between previous exposure to assessment moderation practices and endorsement of its pedagogical value. Independent samples t-test revealed significant differences between groups. As visualized in Figure 2, faculty with prior experience (n = 27) reported substantially higher agreement scores (M = 3.89, SD = 1.19) compared to their inexperienced counterparts (n = 32; M = 2.56, SD = 1.37), t(57) = −3.99, p < 0.001. The magnitude of this difference, as indicated by Cohen's d = 1.03, represents a large effect size, underscoring both the statistical and practical significance of these findings. Linear regression analysis further substantiated these results, indicating that prior experience with assessment moderation predicted a 1.33-point increase in agreement ratings on the 5-point Likert scale (β = 1.33, 95% CI [0.66, 1.99], p < 0.001). The model accounted for 21.4% of the variance in perceived value ratings [R2 = 0.214, F(1, 57) = 15.52, p < 0.001]. Of the 59 participants providing complete data, 54% (n = 32) reported no prior experience with assessment moderation, while 46% (n = 27) indicated previous exposure. Response distributions differed markedly between groups: inexperienced faculty demonstrated greater variability in their ratings across the full range of the scale, whereas experienced faculty responses concentrated predominantly at higher agreement levels.

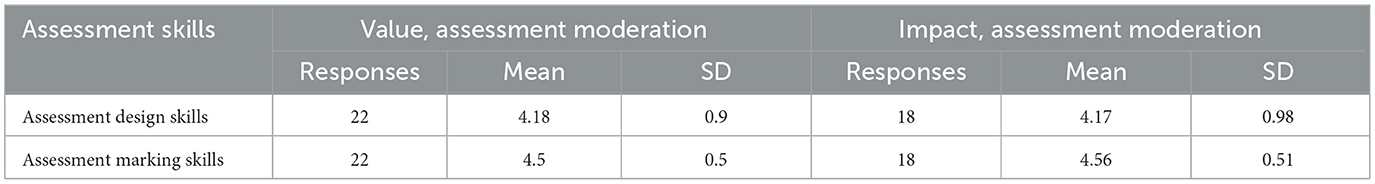

The data further suggests that faculty members' negative perceptions regarding the value and impact of assessment moderation practices were not significantly associated with their perceived levels of assessment literacy. Table 3 presents the assessment literacy profile of faculty with negative perceptions about assessment moderation (n = 22 for value and n = 18 for impact). These faculty expressed strong positive perceptions of their technical competencies in marking and design skills. This finding suggests that skeptical attitudes toward moderation processes cannot be primarily attributed to deficiencies in assessment knowledge or competencies, indicating that resistance to these practices may stem from alternative factors beyond pedagogical understanding.

On the other hand, a subset of faculty participants articulated a more circumscribed conceptualization of assessment moderation's relevance, positing that its utility is predominantly confined to educators transitioning into the institutional context. This attitude is clear in the relatively large percentage of faculty who expressed neutral positioning to the value and impact of assessment moderation, 21% and 31%, respectively. These respondents contended that moderation processes serve primarily as socialization mechanisms for faculty who are new to the country, institution, or teaching profession, facilitating their acculturation to localized assessment norms and expectations. This perspective positions moderation not as a universally valuable practice but rather as a contextually specific scaffold that diminishes in significance as faculty develop familiarity with institutional assessment cultures.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that community building surfaced as the most dominant discourse in faculty responses to questions on the values they associate with assessment moderation in its current or desired form. This finding agrees with those of Grainger et al. (2016) who concluded that casual staff in Australia prioritized community building over other discourses in Adie et al.'s (2013) framework and expressed a strong desire for professional dialogue opportunities regarding standards. Notably, however, the data also shows that the learning dimension of community building prevailed over collegiality and collaboration. Although faculty—many of whom are non-native English speakers—acknowledged the collaboration opportunities afforded by assessment moderation, they placed greater emphasis on its role in facilitating navigation of the institutional context. Specifically, they highlighted its value in strengthening assessment literacy and accuracy, clarifying institutional expectations, and improving linguistic precision and appropriacy. In doing so, faculty develop shared understandings not only of standards but also of broader expectations pertaining to student competence, linguistic proficiency, and institutional policy. Emphasis on linguistic accuracy is not surprising considering that a majority of faculty members are non-native speakers of English, and students are speakers of English as a second or even a foreign language. In this vein, O'Hagan and Wigglesworth (2015) argue that language “may obfuscate assessor judgements of content” (p. 1743). Therefore, assessment moderation could serve as a learning tool for both native and non-native speakers of English. The link between assessment moderation and faculty learning is corroborated by the findings of Smaill (2020) who demonstrated that teachers' involvement in moderation practice has the potential to bolster their assessment skills. The prevalence of “learning” as a major subtheme in the data under the theme “community building” gives some credibility to the framework proposed in Tuovinen et al. (2015) which places “learning” as a standalone purpose of assessment moderation. Therefore, this paper argues that the community building component of Adie et al.'s (2013) framework effectively accounts for relevant “positive” faculty responses to the purposes of assessment moderation. At the same time, this paper recommends renaming the community building discourse to “capacity and community building” to clearly account for the values of learning associated with assessment moderation and increase the framework's usability.

On the other hand, the results further suggest that assessment practice in its current form at the target institution could benefit from increased provision of safe spaces for professional dialogue regarding standards. This was supported by a response to a quantitative question where about 70% of faculty believed that assessment moderation in its current form may cause conflict among faculty, largely because communication among faculty in relation to moderation is normally carried out through email. This finding is consistent with Mason et al. (2023) who concluded that sessional faculty members in Australia are challenged by the power dynamics and subjectivity of assessment moderation. The literature consistently argues that opportunities for informal discussions at various points in the semester accelerate faculty learning, enhance assessment literacy, and mitigate tensions (e.g., Grainger et al., 2016; O'Connell et al., 2016; Smaill, 2020).

The findings further show that community building and learning prevailed over accountability, which came third in faculty responses. Interestingly, despite the negative connotations often associated with accountability in the literature, faculty members in this study conceptualized accountability in predominantly positive terms. This finding is particularly noteworthy because the limited literature on education in the UAE typically foregrounds accountability and managerialism as dominant themes. For example, Ajayan and Balasubramanian (2020) found that monitoring is one of the most dominant new managerial factors faculty members experience in the UAE. Similarly, Hudson (2013) found that faculty evaluation practices UAE institutions are excessively managerialist and punitive. Vanvelzer (2021) also concluded that assessment practice in higher education institutions in the UAE is excessively focused on accountability.

The results emerging from this study also suggest that “justification” and “community building” intersects with some aspects of “accountability”. While grade distribution is used by Adie et al. (2013) as a typical example of assessment moderation being an accountability instrument, faculty at Muhra University argued that it could also promote community building and justification. This finding agrees with Bloxham et al. (2016) who contend that discourses of grade distribution could include community building when focus is on discussions about grade distribution and whether it should be amended and justification when academics are concerned with explaining their grade distribution and the soundness of applied standards. When assessment moderation places faculty members in a position where they are expected to justify their decisions, they are giving an account of the grounds for their decisions, which can be argued to constitute a level of accountability. This is corroborated by Leithwood and Earl (2000) who argue that the levels of accountability include–from lowest to highest–description, explanation, and justification. This is also supported by Bovens (2007) who defines accountability as a “relationship between an actor and a forum, in which the actor has an obligation to explain and to justify his or her conduct, the forum can pose questions and pass judgement, and the actor may face consequences” (p. 12). As such, whether justification is upward (i.e., to an accrediting agency or to a line manager), downward (to a student), or horizontal (i.e., to a colleague), justification as a concept encapsulates a form of accountability. Therefore, this paper argues that the framework proposed in Adie et al. (2013) could benefit from combining justification with accountability under one discourse. Associated discourses of giving feedback to students and promoting confidence in marking, currently under justification, can be grouped under the capacity and community building discourse, thereby accounting for all the different concepts falling under Adie et al.'s (2013) concept of justification.

Additionally, the results show that Adie et al.'s (2013) framework does not sufficiently account for scenarios in which faculty members fundamentally contest the underlying premises of moderation or perceive it as having negligible to minimal pedagogical or institutional value. This paper argues that there are two reasons for this position. First, the faculty composition at the target institution is predominantly comprised of social scientists who, as Knight (2006) argues, demonstrate a propensity toward more subjective assessment practices compared to their natural science counterparts. This tendency is theoretically grounded in their interpretivist epistemological orientations, which acknowledge the absence of singular, objective truths in knowledge construction (Bloxham, 2009; Boud et al., 2018). Consequently, this disciplinary positioning may influence faculty attitudes toward standardized assessment moderation processes that emphasize consistency and objectivity. In this vein, Bloxham and Price (2015) question the underlying assumptions supporting moderation as a safeguard for quality assessment. This position could also be viewed as a form of epistemic resistance where faculty are challenging the underlying assumption of assessment moderation as a quality improvement tool. As an example, one faculty noted that “[t]he premise of this thing is invalid and wrong and deleterious to the faculty.” Another remarked that “every element of the current practice is deeply insulting to faculty members. It assumes that we have neither the knowledge, skills, experience, or basic intelligence to carry out the task.” This finding comports with the findings drawn by Deneen and Boud (2014) who concluded that epistemic resistance is one of the key challenges associated with change to assessment paradigms in higher education. Second, assessment moderation is not commonly practiced in the UAE or in many other parts of the world, especially in North American institutions. This was supported by the answer to a question asking faculty to indicate whether they had assessment moderation in their previous institution. In responding to this question, 34 faculty members (46% of respondents) indicated that they did not have this practice before joining Muhra University. Prior experience with assessment moderation significantly influences faculty attitudes, with experienced practitioners reporting substantially higher endorsement scores (Cohen's d = 1.03). This experiential divide, affecting 54% of participants who lacked prior exposure, represents a critical gap in professional development that may impede institutional implementation of collaborative assessment practices. Notably, faculty skepticism toward moderation practices cannot be attributed to assessment literacy deficiencies, as those expressing negative views demonstrated strong self-perceptions of technical competencies. This dissociation suggests that resistance stems from factors beyond pedagogical understanding, potentially including institutional culture or philosophical differences regarding assessment autonomy (Brown et al., 2011; Looney et al., 2018). The substantial predictive power of prior experience (R2 = 0.214) indicates that institutional strategies should prioritize hands-on moderation activities rather than theoretical knowledge transfer to cultivate faculty buy-in and optimize quality assurance implementation in higher education assessment practices. Nonetheless, the literature establishes that faculty self-perceptions of assessment competence (or assessment self-efficacy) may not accurately correspond to their demonstrated assessment literacy levels (cf. Gotch et al., 2021). Therefore, this discrepancy between perceived and actual competency suggests that self-reported measures of assessment knowledge should be interpreted with caution, as they may not provide reliable indicators of genuine pedagogical expertise in assessment practices.

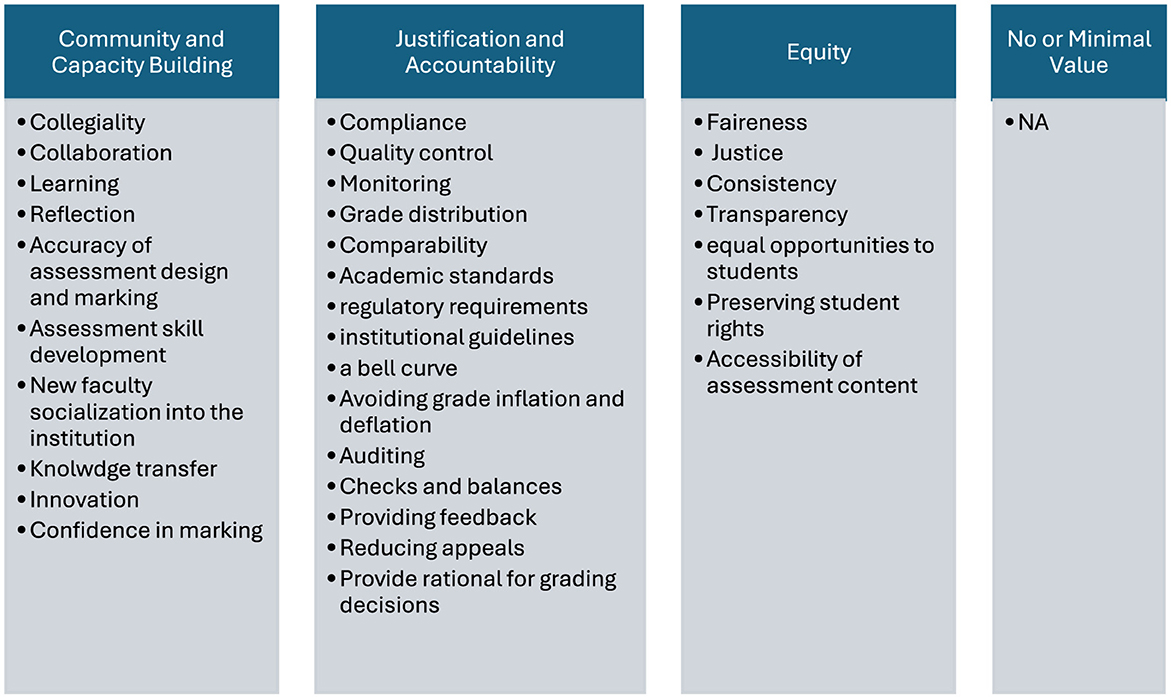

This paper argues that the gap in Adie et al.'s (2013) framework can be reconciled in one of two ways. First, the framework could be expanded to include an additional category that explicitly conceptualizes faculty contestation of assessment moderation's fundamental value. Alternatively, the framework's scope could be recalibrated to explicitly acknowledge its applicability only in contexts where participants attribute some degree of value to moderation processes. Either modification would enhance the framework's analytical robustness when examining assessment moderation as a contested practice within diverse institutional environments. Drawing upon preceding discussion, a proposed revision of the framework is presented in Figure 3. This revised conceptualization incorporates lexical indicators and discursive markers that researchers may employ as analytical heuristics when identifying and categorizing the assessment moderation discourses articulated by study participants. These linguistic signifiers serve as methodological entry points for discourse analysis, facilitating more systematic identification of the underlying conceptual orientations that faculty members express when discussing assessment moderation practices. The inclusion of these discursive indicators enhances the framework's operational utility for qualitative researchers, providing a more robust analytical apparatus for examining the nuanced ways in which faculty conceptualize and position themselves in relation to assessment moderation processes within diverse institutional contexts.

Figure 3. Revision of Adie et al. (2013) framework.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study has provided valuable insights into faculty perceptions and discourses regarding assessment moderation within the non-Western context of Muhra University in the UAE. Through a mixed-methods case study approach, this paper has examined how assessment moderation is experienced by faculty members, revealing several significant findings that contribute to the broader literature on assessment practices in higher education. This study demonstrates that while Adie et al.'s (2013) framework effectively captures significant dimensions of faculty perceptions regarding assessment moderation, it exhibits notable limitations in conceptualizing faculty contestation of moderation's fundamental premises. The framework inadequately addresses instances where faculty articulate perceptions of minimal or negligible value in moderation practices. Furthermore, our analysis suggests two substantive refinements to enhance the framework's analytical precision: first, consolidating the justification and accountability discourses into a unified category, recognizing their conceptual overlap in faculty narratives; and second, reconceptualizing the community building discourse as ‘capacity and community building' to more accurately reflect the professional learning dimensions that emerged prominently in our data. Additionally, we propose an enhanced version of the framework that incorporates specific lexical indicators as methodological heuristics for researchers, thereby increasing its operational utility in qualitative analysis of assessment moderation discourses across diverse institutional contexts.

The paper further demonstrates that faculty at Muhra University predominantly perceive assessment moderation through a community-building discourse. This finding extends Adie et al.'s (2013) four-discourse framework by highlighting the contextual nuances that shape faculty perceptions in internationalized, non-Western settings. The prominence of community building as a discourse reflects the value faculty members place on collegial dialogue, shared understanding of standards, and collaborative professional development—elements that are particularly salient in a diverse academic environment where faculty come from varied linguistic and cultural backgrounds. While community building emerged as the dominant discourse, our findings also reveal the multifaceted nature of assessment moderation, with faculty simultaneously recognizing its role in ensuring equity, maintaining accountability, and providing justification for assessment decisions. This multidimensionality suggests that assessment moderation serves multiple purposes simultaneously, though not without tensions and contradictions. Faculty expressed concerns about subjectivity, workload implications, and potential interpersonal conflicts that can arise during moderation processes, indicating that the implementation of moderation policies requires careful consideration of both procedural and relational aspects.

Despite its contributions, this study has limitations that should be acknowledged. The focus on a single institution and the predominance of social science faculty in the sample limit the generalizability of findings. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data and the evolving nature of assessment moderation practices at the institution may influence the stability of perceptions over time. One methodological limitation concerns the lack of demographic data collection, which prevented the investigation of relationships between faculty background characteristics and their expressed perceptions.

Future research should expand the empirical scope to include multiple institutions and disciplines within the UAE and other non-Western contexts. Longitudinal studies would be valuable in tracking how perceptions and practices evolve with policy changes and professional development initiatives. Further investigation into effective strategies for fostering collegial dialogue and reducing conflict in moderation processes would also be beneficial, as would research examining the impact of assessment moderation on student learning outcomes and institutional quality assurance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article can be made available by the authors upon obtaining ethical approval from Muhra University.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Dr. Jan McArthur, Lancaster University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

RA: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Methodology. NA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. MA-D: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Lenore Adie, the co-developer of the discourses of moderation framework, for the valuable feedback and insights she provided during the development of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The author declares that Gen AI was used minimally in the creation of this manuscript. Claude 4 Sonnet (August 2025 version) was utilized to provide a review of minor parts of the language used in the manuscript. All linguistic revisions were rigorously verified by the researcher. This was carried out after the feedback was received from reviewers and after the declaration of AI use.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adie, L. (2022). “Assessment moderation: is it fit for purpose?,” in Research Conference 2022: Reimagining assessment: Proceedings and program, ed. K. Burns. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research. doi: 10.37517/978-1-74286-685-7-2

Adie, L., Lloyd, M., and Beutel, D. (2013). Identifying discourses of moderation in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 968–977. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.769200

Ajayan, S., and Balasubramanian, S. (2020). “New managerialism” in higher education: the case of United Arab Emirates. Int. J. Compar. Educ. Dev. 22, 147–168. doi: 10.1108/IJCED-11-2019-0054

Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., and Boud, D. (2021). Performing standards: a critical perspective on the contemporary use of standards in assessment. Teach. High. Educ. 26, 728–741. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2019.1678579

Beutel, D., Adie, L., and Lloyd, M. (2017). Assessment moderation in an Australian context: processes, practices, and challenges. Teach. High. Educ. 22, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2016.1213232

Bloxham, S. (2009). Marking and moderation in the UK: false assumptions and wasted resources. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 34, 209–220. doi: 10.1080/02602930801955978

Bloxham, S., Hughes, C., and Adie, L. (2016). What's the point of moderation? A discussion of the purposes achieved through contemporary moderation practices. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 638–653. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1039932

Bloxham, S., and Price, M. (2015). External examining: fit for purpose? Stud. High. Educ. 40, 195–211. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.823931

Boud, D., Dawson, P., Bearman, M., Bennett, S., Joughin, G., Molloy, E., et al. (2018). Reframing assessment research: through a practice perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 1107–1118. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1202913

Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: a conceptual framework. Eur. Law J. 13, 447–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., Clarke, V., and Weate, P. (2016). “Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research,” in Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise (Abingdon: Routledge), 213–227.

Brown, G. T. L., Lake, R., and Matters, G. (2011). Queensland teachers' conceptions of assessment: the impact of policy priorities on teacher attitudes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.003

CAA (2019). Policies and Procedures Manual. Sharjah University. Available online at: https://www.sharjah.ac.ae/-/media/project/uos/sites/uos/departments/compliance-and-internal-audit-office/our-policies/policies_and_procedures_manual.pdf (Accessed September 22, 2025).

Crimmins, G., Nash, G., Oprescu, F., Alla, K., Brock, G., Hickson-Jamieson, B., et al. (2016). Can a systematic assessment moderation process assure the quality and integrity of assessment practice while supporting the professional development of casual academics? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 427–441. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1017754

Cumming, T., and Miller, M. D. (2023). Enhancing Assessment in Higher Education: Putting Psychometrics to Work. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis.

Deneen, C., and Boud, D. (2014). Patterns of resistance in managing assessment change. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 577–591. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.859654

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., and Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. Indianapolis Indiana 17. doi: 10.1002/9781394260645

Goos, M., and Hughes, C. (2010). An investigation of the confidence levels of course/subject coordinators in undertaking aspects of their assessment responsibilities. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 315–324. doi: 10.1080/02602930903221477

Gotch, C. M., Poppen, M. I., Razo, J. E., and Modderman, S. (2021). Examination of teacher formative assessment self-efficacy development across a professional learning experience. Teach. Dev. 25, 534–548. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2021.1943503

Grainger, P., Adie, L., and Weir, K. (2016). Quality assurance of assessment and moderation discourses involving sessional staff. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 548–559. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1030333

Hand, L., and Clewes, D. (2000). Marking the difference: an investigation of the criteria used for assessing undergraduate dissertations in a business school. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 25, 5–21. doi: 10.1080/713611416

Hudson, P. (2013). Tiptoeing through the minefield: teaching English in Higher Educational Institutes in the United Arab Emirates. Canterbury: Canterbury Christ Church University.

Jackel, B., Pearce, J., Radloff, A., and Edwards, D. (2017). Assessment and feedback in higher education: a review of literature for the Higher Education Academy. Available online at: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/hub/download/acer_assessment_1568037358.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2025).

Knight, P. (2006). The local practices of assessment. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 31, 435–452. doi: 10.1080/02602930600679126

Leithwood, K., and Earl, L. (2000). Educational accountability effects: an international perspective. Peabody J. Educ. 75, 1–18. doi: 10.1207/S15327930PJE7504_1

Looney, A., Cumming, J., van Der Kleij, F., and Harris, K. (2018). Reconceptualising the role of teachers as assessors: teacher assessment identity. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 25, 442–467. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090

Mason, J., Roberts, L., and Flavell, H. (2022). A Foucauldian discourse analysis of unit coordinators' experiences of consensus moderation in an Australian university. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 47, 1289–1300. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2022.2064970

Mason, J., Roberts, L. D., and Flavell, H. (2023). Consensus moderation and the sessional academic: valued or powerless and compliant? Int. J. Acad. Dev. 28, 468–480. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2022.2036156

O'Connell, B., De Lange, P., Freeman, M., Hancock, P., Abraham, A., Howieson, B., et al. (2016). Does calibration reduce variability in the assessment of accounting learning outcomes? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 331–349. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1008398

O'Hagan, S. R., and Wigglesworth, G. (2015). Who's marking my essay? The assessment of non-native-speaker and native-speaker undergraduate essays in an Australian higher education context. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 1729–1747. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2014.896890

O'Leary, M., and Cui, V. (2020). Reconceptualising Teaching and learning in higher education: challenging neoliberal narratives of teaching excellence through collaborative observation. Teach. High. Educ. 25, 141–156. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1543262

Prichard, R., Peet, J., El Haddad, M., Chen, Y., and Lin, F. (2024). Assessment moderation in higher education: guiding practice with evidence-an integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 136:106512. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106512

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach (1 Edn.). New York: Bloomsbury.

Ruel, E., Wagner-Huang, W. E., and Gillespie, B. J. (2015). The Practice of Survey Research: Theory and Applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., and Thornhill, A. (2016). Research Methods for Business Students (7th Edn.). New York: Pearson education.

Smaill, E. (2020). Using involvement in moderation to strengthen teachers' assessment for learning capability. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 27, 522–543. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2020.1777087

Tuovinen, J., Dachs, T., Fernandez, J., Morgan, D., and Sesar, J. (2015). Developing and Testing Models for Benchmarking and Moderation of Assessment for Private Higher Education Providers. Available online at: https://ltr.edu.au/resources/ID12_2280_Tuovinen_Report_2015.pdf (Accessed September 15, 2025).

Vanvelzer, D. (2021). Assessment in higher education as a policy implementation issue: A case study of how actors and multi-level contextual factors influence assessment implementation at an institution in the UAE. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Bath]. University of Bath Research Data Archive.

Watty, K., Freeman, M., Howieson, B., Hancock, P., O'Connell, B., Lange, d. e., et al. (2014). Social moderation, assessment and assuring standards for accounting graduates. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 39, 461–478. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2013.848336

Keywords: assessment moderation, UAE, higher education, assessment, discourses of assessment moderation

Citation: Alsharefeen R, Al Sayari N and Al-Deaibes M (2025) Navigating new territory: discourses of assessment moderation in UAE higher education. Front. Educ. 10:1635619. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1635619

Received: 26 May 2025; Accepted: 15 September 2025;

Published: 07 October 2025.

Edited by:

Mary Frances Hill, The University of Auckland, New ZealandReviewed by:

Peter Ralph Grainger, University of the Sunshine Coast, AustraliaAna Remesal, University of Barcelona, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Alsharefeen, Al Sayari and Al-Deaibes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rami Alsharefeen, cmFtaS5hbHNoYXJlZmVlbkB5YWhvby5jb20=

Rami Alsharefeen

Rami Alsharefeen Naji Al Sayari1

Naji Al Sayari1