- 1Department of Foreign Language Studies, Tianshui Normal University, Tianshui, Gansu Province, China

- 2Faculty of Educational Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia

Although instructional coaching has been increasingly adopted as a tool for faculty professional development in Chinese higher education, it often encounters resistance due to signals of authority, emotionally detached delivery, lack of sustained follow-up, and non-specific or generic feedback. This qualitative study was carried out to explore how faculty at a public university in Gansu Province perceive the instructional coaching. To achieve that, the data collected through semi-structured interviews with 15 instructors from various disciplines and career stages were analyzed using thematic analysis, under a theoretical standpoint combining institutional theory with social constructivism. The findings revealed that faculty often perceived instructional coaching as a supervisory mechanism rather than developmental support, primarily due to ambiguous protocols, hierarchical feedback dynamics, limited disciplinary alignment, and emotionally distant communication. These conditions—rooted in institutional structure and interactional design—fostered anxiety, guarded engagement, and performative compliance, underscoring that faculty responses are shaped less by the idea of coaching itself and more by how it is enacted in context. Overall, the study suggests that faculty engagement with instructional coaching is shaped less by the model itself and more by how it is enacted—particularly in relation to trust, clarity, and relevance within a hierarchical context.

1 Introduction

The rapid change in higher education is putting more demands on faculty members to enhance their teaching skills, promote student-centric learning, and adjust to digital reforms, especially regarding artificial intelligence (Zhao et al., 2021). As a strategic shift, instructional coaching is an effective model to provide on-the-job, sustained professional development. Coaching is defined as a sustained, collaborative, in-class process of providing target support and guided professional conversation aimed at encouraging reflection on practice and improvement of the practice (Kraft et al., 2018). The perceptions of the faculty, on the other hand, play a crucial role in its implementation. Especially in the context of how instructors see its role, sufficiency, and fit in the ecosystem of their institutions (Huang, 2023; Jiang et al., 2019). Faculty perceptions involve how the instructors, in this case, associate coaching with their professional lives and workplace, including the predominant culture of the organization, which are termed professional frameworks, history, identity, and context (Lofthouse and Wright, 2012).

How faculty perceive the process of coaching impacts the outcomes of the coaching process. When coaching is perceived as supportive as opposed to evaluative, it fosters openness, trust, and innovation in teaching (Kraft et al., 2018; Huang, 2023). For example, in the meta-analyzed research in the United States, specified coaching roles, along with the option of voluntary participation, were positively correlated with improvements in instructional practice and student learning outcomes (Kraft et al., 2018). On the other hand, when coaching is treated an activity that must be done in order to tick boxes, or when it is absent any connection to the associated disciplinary fields, the result is coaching that is followed by disengaged, performative compliance, with little in the way of instructional change (Jiang et al., 2019). These issues may be worse in China, where faculty are typically under significant stress, little control over how they teach, and intense pressure to meet targets; such conditions make it difficult to practice reflective teaching (Zhao et al., 2021).

The problem is especially severe in resource-poor contexts, such as the western provinces of China. The tendency to avoid interpersonal conflict and protect one's professional reputation, as well as deeply rooted cultural norms within organizational structures, often limits the dialogue between faculty members and not as able to self-critique effectively (Zhao et al., 2021). Also, instructional coaching is associated with performance evaluation in contexts where coaching sessions are tied to a promotion decision or formal observation within a performance review (Huang, 2023). Faculty disengagement is attributed to many of the factors, such as role ambiguity, lack of privacy, and simplistic design of the evaluation mechanism, especially in the case of coaches who lack the relevant experience (Jiang et al., 2019). Also, the lack of investment in pedagogical innovations due to the imbalanced teaching and research workloads, and the institutional rewards that emphasize research neglect, further suggests that teaching traditional disciplines, such as in China, is unlikely to bring pedagogical change. These are not only China's issues, as there is sufficient documentation for similar cases in South Africa (Reddy et al., 2019) and the Middle East (Abdallah and Forawi, 2017) where the coaching purposes are excessively polite to the hierarchical contexts and non-observant of the implementation mismatches.

In comparison, the coaching model in the USA, Canada and Australia tends to focus more on the concepts of trust, supported volunteer participation and strong institutional support. These countries also tend to separate coaching from formal processes of evaluation and ensure that the coach's level of expertise aligns closely with the faculty member's area of discipline. These contexts tend to enhance the coaching's credibility and effectiveness. While applying models of coaching like these tends to provide significant improvement in the quality of teaching and the performance of learners, these models tend to be the most challenging to implement in stratified, low resource settings. Comparative research has cautioned that the use of such models, in the absence of cultural or institutional context, can result in shallow adoption, resignation, or lip-service (Huang, 2023). As pointed out by Coburn and Woulfin (2012), “the most favorable conditions for the success of any given strategy are eliminated when the systems that are thought to collaborate become disjointed.” Although coaching is becoming more common in Chinese higher education, most research focuses on the management and implementing sides. Very few studies explored the ways university teachers encounter and interpret coaching, particularly in remote and badly funded institutions (Zhao et al., 2021). In these contexts, the gap between the national discourse on reform and practice is, to a large extent, still hidden. It is particularly important how faculty interpret coaching in such contexts, since they are the most important drivers of instructional change (Huang, 2023). This gap in the literature has been targeted by the current study which investigates faculty attitudes and actions at a western Chinese university, in which reform aspirations and deeply seated institutional practices are at a crossroads.

This study takes an interpretivist stance, regarding instructional coaching as a process of social construction influenced by institutional arrangements and social interactions. Using institutional and social constructivist lenses, the study investigates the extent to which the university organizational arrangements, evaluation systems, institutional boundaries, and the associated control systems shape coaching relations and the ways faculty members teach. It studies how faculty members develop understandings of these relations with coaching practices (Jiang et al., 2019). The study employed a combination of peer debriefing and role-separation protocols to enhance trustworthiness of the account, and is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: How do faculty at a public university in Gansu perceive and make sense of instructional coaching?

RQ2: What contextual mechanisms shape their engagement, resistance, or reinterpretation of coaching?

2 Literature review and theoretical framework

This section reviews recent global and local guidelines for faculty development coaching in higher education, synthesizes empirical findings on barriers and policy, and situates coaching within relevant theoretical models.

2.1 Guidelines for teaching in higher education: global frameworks and local perspectives

Faculty development coaching is increasingly recognized as a means to foster reflective teaching, enhance student outcomes, and promote equity in higher education. Recently developed approaches, including data coaching, have shown value in assisting faculty in studying student achievement data and creating plans to respond to equity challenges, particularly in STEM (Jaafar and Cuellar, 2024). Coaching programs contribute to positive organizational outcomes when they are non-evaluative, built on trust, and centered on feedback, communicating professional growth. Such programs are positive organizational outcomes (Burleigh et al., 2022; Lofthouse, 2018; Bedford, 2022). These programs feature coaching best practices and professional development components, including focus on content, active learning, coherence, sustained duration, and collective participation (Bedford, 2022; Lofthouse, 2018).

Coaching practices, particularly in non-Western, resource-constrained settings, can be influenced by hierarchical structures, resource scarcity, and institutional timelines which are inflexible. Coaching in these scenarios can be understood as constituted, supervised, and passive control as opposed to peer support (Burleigh et al., 2022; Shadle et al., 2017). For coaching to have a sustained positive impact, a peer-centered approach, created around the specific local conditions while retaining critical coaching elements, will be necessary (Burleigh et al., 2022; Jaafar and Cuellar, 2024).

2.2 Structural and relational barriers to implementation

Structural barriers such as overly burdensome teaching loads, strict timetable allocations, inadequate infrastructure, and insufficient administrative support are cited in empirical studies as the main hindrances to faculty participation in coaching (Shadle et al., 2017; Sunal et al., 2001; Burleigh et al., 2022). These obstacles fragment the coherence and duration of coaching programs, which diminishes the overall impact of the program. In underfunded universities, lack of specific goals and poor alignment to the institution's goals further inhibits faculty engagement in the coaching process (Shadle et al., 2017; Sunal et al., 2001).

Relational barriers are just as important. Faculty participation hinges on the levels of trust, and the belief that coaching is meant for support, and not supervision. Faculty will, however, disengage from the coaching process if the narrative is that coaching is oversight of their professional activities, seeing the coach as an assessor, not a collaborator (Burleigh et al., 2022; Lofthouse, 2018). Defensiveness and disengagement are exacerbated in the presence of rigid cultures and lack of clear guidelines, which then makes trust within relationships a governing condition for coaching to work (Burleigh et al., 2022; Lofthouse, 2018).

2.3 Cultural barriers: norms of communication and feedback

Cultural norms, particularly those affected by Confucianism, as well as those in highly stratified societies, bring in indirect coaching and face-saving techniques, which diminish the feedback's developmental utility (Shadle et al., 2017; Burleigh et al., 2022). Cross-national research illustrates how dominance, status in the chain of command, the feedback approach in coaching, and the style of feedback influences the extent to which coaching is embraced as supportive or resisted as evaluative (Burleigh et al., 2022; Jaafar and Cuellar, 2024). Evidence suggests that in some contexts, culturally responsive coaching strategies that focus on relationship-first, respectful of hierarchy, and constructive but indirect feedback improve receptiveness to coaching as well as its effectiveness (Burleigh et al., 2022; Lofthouse, 2018).

2.4 Policy context

Policy frameworks at both global and national levels highlight the need for evidence-based and developmental faculty learning. For instance, sustained professional development is crucial for augmenting access and inclusion for contingent faculty (Culver et al., 2023). However, local implementations often associate supervision with evaluation, which potentially turns coaching into a matter of compliance rather than development (Burleigh et al., 2022). Policy offers both developmental assistance and constraint because of the lack of clarity about role delineation, confidentiality, and reporting structures (Burleigh et al., 2022; Jaafar and Cuellar, 2024).

2.5 Theoretical standpoint: institutional and constructivist

While Neo-institutionalism theories describe the influence of regulative, normative, and the cultural-cognitive pillars on the practices of higher education, especially how formative attempts are sometimes reinterpreted as surveillance within a hierarchical setup (Shadle et al., 2017; Sunal et al., 2001). Mechanically Social constructivism also describes how meanings are created in interactions, through the use of particular conversational routines, as well as language itself, such as how coaching in her context is interpreted as developmental as opposed to evaluative (Lofthouse, 2018; Burleigh et al., 2022). Coaching is then effective only when it combines both structural measures and relational practices that intend developmental coaching.

2.6 Research gap

Despite growing evidence on the benefits of instructional coaching, three key gaps remain. The first is a content gap. Most empirical research is still focused Western and K−12 contexts, which offers little insight into the structural, relational, and cultural barriers which define coaching in non-Western higher education. The second is a methodological gap. Much of the current research relies on surveys, conceptual analyses, or policy reports, and there is a lack of qualitative research on how faculty members understand and experience coaching within the hierarchies. The third is a contextual gap. The disparity in international and national policies, which center on formative, developmental support (UNESCO, 2021; Advance HE, 2023; Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and State Council of the People's Republic of China, 2020), and local implementations that recast coaching, especially in Chinese universities, as compliance is notable. This study aims to address the gaps by exploring faculty perceptions and the limitations they experience in hierarchical academic contexts in relation to instructional coaching.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

We used a qualitative case study approach to analyze faculty perceptions and experiences of instructional coaching. This allowed a rich understanding of the social, cultural, and institutional context of a public university in Gansu Province, China (Yin, 2018). With strong hierarchical and Confucian influences in Chinese higher education, this method helped us see how coaching interacts with local norms.

We used a social constructivist frame, viewing knowledge as a social outcome (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Gallucci et al., 2010). This focus helped us explore how faculty and coaches understand experiences together, especially amid institutional power dynamics. It also aligned with our goal to understand coaching from within the domain, rather than by outside standards.

3.2 Participants

To ensure varied perspectives, we used purposive sampling of faculty who had participated in instructional coaching. Approximately 110 candidates were invited; 15 participated, with a notable variation in terms of gender, age, discipline, degree, and rank. This strategy captured voices from both social and natural sciences, including junior and senior faculty.

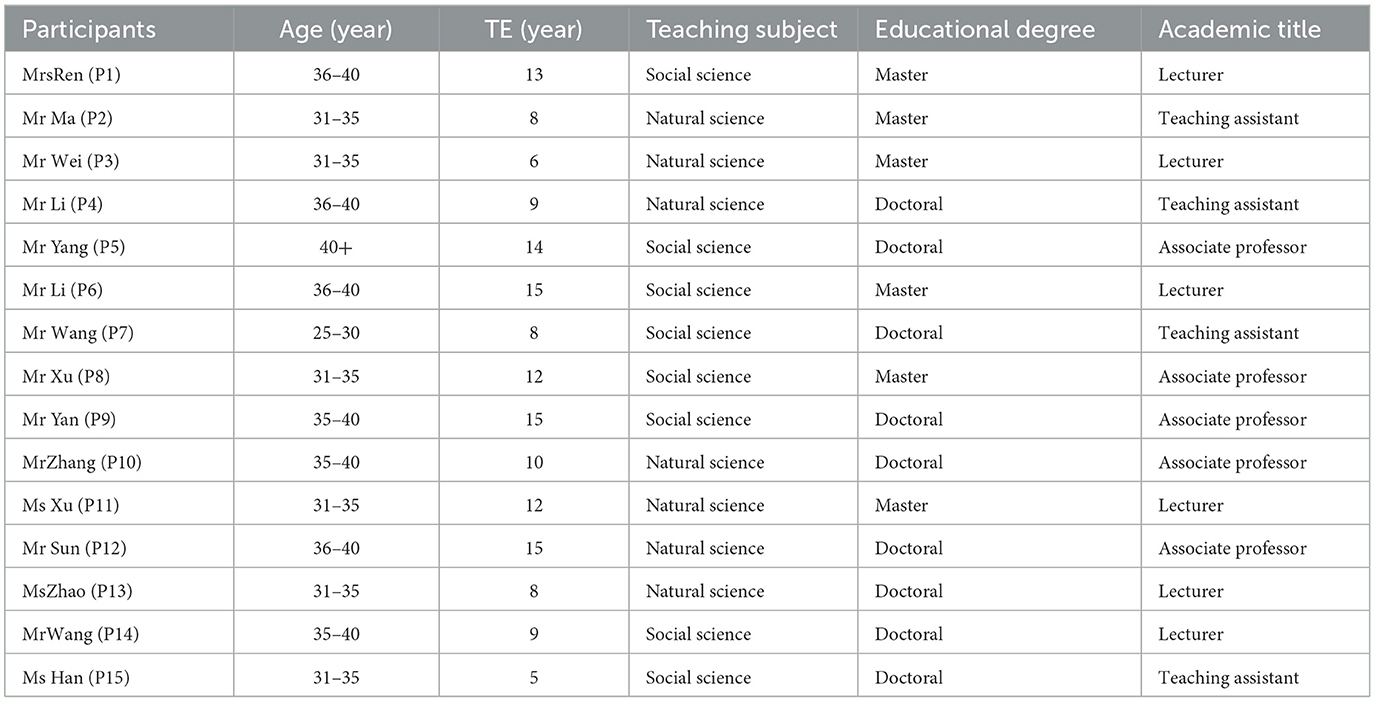

Participants ranged from 25 to over 40 years old and had 5–15 years of teaching experience. They included lecturers, teaching assistants, and associate professors with master's or doctoral degrees, providing a wide range of academic and professional diversity (Table 1).

Although self-selection bias is a limitation in any qualitative study, in this study, we sought to achieve broad demographic and professional diversity, and we critically considered how our sensibilities may have influenced the findings. We achieved data saturation by the fifteenth interview, at which no new major themes were identified. This sample size is methodologically sound for a qualitative study, allowing for credible and transferable findings (Guest et al., 2006).

3.3 Data collection

In this study, we selected semi-structured interviews as the principal mode of data collection. This design afforded a manageable degree of uniformity while simultaneously permitting an in-depth investigation of participants' subjective realities (Kallio et al., 2016). Interviews were conducted in private academic offices or via secure videoconferencing, at the participant's discretion, to maximize comfort and encourage candor.

Each session extended between 30 and 60 min, allowing sufficient duration for both considered replies and layered elaboration. A tested interview protocol directed the conversations, systematically addressing both systemic and relational facets of instructional coaching. The interviews started with questions about how clear, specific, and directive the coaches' guidance was. Follow-up questions asked participants to reflect on how they felt during coaching, what kind of support they received from the institution, whether the coaching aligned with their academic field, and how cultural norms influenced communication. Upon securing participant consent, we audio-recorded, fully transcribed, anonymized, and imported the interviews into NVivo 12 to facilitate transparent and retraceable analysis. Throughout the research, we adhered to ethical guidelines by securing informed consent and obtaining approval from the university's research ethics board.

3.4 Data analysis

For the in-depth analysis of the qualitative data, we employed Braun and Clarke's (2006) six-phase thematic analysis to examine our data systematically. Beginning with open coding (Strauss, 1987), we engaged with transcripts on a line-by-line basis, creating descriptive codes that captured the participants' affective responses and conceptual orientations, such as “hierarchical tension,” “lack of empathy,” “ambiguous feedback,” and “emotional resistance,” among others. Next, we conducted axial coding, organizing these initial codes into interrelated, broader categories that encompass both structural and relational dimensions. Through careful, selective coding, the categories evolved into a unified core theme: Instructional Coaching as a Structurally Misaligned Support System. This theme highlights the disjunction between the developmental aspirations of coaching and the bureaucratic modalities through which they are enacted.

In order to fortify the analytical integrity of our work, we engaged in sustained memo-writing to document evolving interpretations, conducted peer debriefing sessions with a qualitative study expert to corroborate our thematic delineations and to guard against interpretive bias, and employed reflexive journaling to maintain constant awareness of our positionality and to ensure that our interpretations remained anchored in participants' articulations. Collectively, these strategies bolstered the credibility and trustworthiness of our findings. NVivo 12 facilitated the systematic organization of our data and the visual mapping of thematic interrelations, always within the bounds of a rigorous methodological framework.

3.5 Ethical and trustworthiness considerations

This study received ethical approval from targeted research university located in Gansu province, China. All participants were provided information about the study aims and procedures including risks/benefits, confidentiality, and withdrawal, and they signed the written informed consent. To alleviate any hierarchical pressure, the recruitment strategy involved neutral means (department listservs/research account emails) and the supervisors were not informed about their participation. Interviews (lasting 45–70 min) were arranged in a private office or a secure videoconference room (waiting room enabled, no observers) and outside of the supervisor appraisal cycles. The interviews were recorded, transcribed in full text, and anonymized (assigned pseudonyms, indirect identifiers such as department and rank were masked). The transcribed and coded data, memos, and audio files were stored in digital format on the university server protected with AES-256 encryption, additional encryption for the files, and paper notes were kept in a locked cabinet. The data will remain on file for 2 years in compliance with the IRB policy, after which it will be securely destroyed. Given the hierarchical nature of the setting, respect- and confidentiality norms, and interview coaching expectation, participants were provided with the choice of interview mode and location.

Member checking occurred in two stages: the 10-day transcript confirmatory, and the mid-analysis theme validation. For the latter, six faculty were asked to review summaries along with some of the emerging themes, and three of them provided enough contextual clarifications that called for some of the more definitive refinements, such as changing “surveillance” to “evaluation-linked oversight” and splitting “role ambiguity” into “coach identity” and “process clarity.” Peer debriefing with an unaffiliated qualitative methodologist occurred in bi-weekly intervals during which the planning-concept and the code definitions were tested, rival explanations were interrogated (evaluation and workload linkage were pitted against each other), and negative cases were provided. A versioned audit trail (protocol updates, recruitment logs, NVivo node trees, codebook iterations, decision memos) supported dependability, while a reflexive journal (positionality, assumptions, and analytic rationales), along with a confirmability analysis and data-to-claim chains (excerpt → within-case memo → cross-case theme) validated claim confirmability. For transferability, a thick description of the coaching procedures and the hierarchical institutional context (workload, evaluation linkages), as well as participant attributes (discipline bands, career stage) provides the reader with necessary contextual details.

4 Findings

This section addresses the two research questions: (1) how university faculty experience and interpret instructional coaching in a hierarchical academic setting, and (2) the challenges they face throughout the coaching process. Thematic analysis revealed participants' lived experiences and nuanced insights, supported by direct quotations that illuminate both structural and relational dynamics within a resource-limited, top-down institutional context.

4.1 Findings pertaining to RQ1: faculty perceptions and experiences

Four interrelated sub-themes emerged from faculty accounts of instructional coaching in a hierarchical university setting. First, a prevailing sense of emotional detachment characterized the coaching relationship. Faculty described interactions as formally correct yet devoid of warmth, which led them to interpret the intervention as more regulatory than developmental. Consequently, emotional resistance overshadowed any potential for collaborative support. Second, the absence of a coherent interactive framework was evident; faculty encountered irregular, vague, and sometimes contradictory forms of feedback that failed to articulate precise developmental trajectories. Taken together, these dimensions construct a picture of a coaching system perceived as emotionally distant, methodologically inconsistent, and lacking in substantive contributions to long-term faculty growth.

4.1.1 Lack of empathy

A common issue raised in interviews was the lack of empathy in instructional coaching. This was cited as an obstacle to building trust, openness, and constructive conversations. Faculty underscored the point that coaching successfully is not simply a matter of having pedagogical knowledge, but also having emotional intelligence, especially the disposition to hear, appreciate, and validate the realities of the faculty.

“In training instructional coaches, they both need to focus on listening and understanding… There is no emotional bond if the coach is too professional, too far removed.” (P3)

That absence of an emotional connection was not perceived as simply a small interpersonal issue; it was a source of defensive reactions that sabotaged coaching's developmental purpose. Several participants reported feelings of being judged and misunderstood and even dismissed when coaches did not consider the reality of their teaching situations.

“Sometimes coaches do not care about our teaching reality… They speak like outsiders… It makes me feel they are judging, not helping.” (P6)

“Instructional coaching is supposed to be supportive, but many faculty are defensive right out of the gate… If you are too cold in communication, faculty think they are being watched… It impacts the faculty's ability to open up.” (P7)

The lack of emotional connection from coaches feels most detrimental when feedback is given in large groups or in other indifferent fashions, adding to the sense of exposure and humiliation.

“The coach only gave feedback in public meetings, which was embarrassing… There was no effort to understand my situation before commenting.” (P13)

Even under pressure to perform and teach, new faculty, and especially those new to the school, might perceive critique and feedback as punitive when no empathy is given.

“For new faculty, the teaching stress is high… It is a thin line between critique and nurturing growth. The secret to good coaching is to manage these two sides of a player's character skilfully.” (P15)

4.1.1.1 Interpretation

These examples clearly illustrate that, in coaching, empathy is far from a “soft skill.” Without empathy, relational coaching becomes stale, or worse, adversarial. Monitored, rather than supported, under hierarchical surveillance, faculty reported distant coaching relationships.

4.1.1.2 Researcher reflexivity

As a practitioner-researcher in this context, I previously regarded these problems as being due to a clash of personalities or communication styles. Peer debriefing and further analysis on early career faculty responses led me to see a structural pattern: lack of empathic engagement limited relational trust to the point where it hardened status differentials and elicited performative compliance rather than authentic engagement and reflection.

4.1.2 Instructional coaching as supervision rather than development facilitator

Some individuals described coaching as more hierarchical, formal, and evaluative, resembling supervision rather than peer-supported development. Such distancing, “official” language and one-way critique were perceived as signs of monitoring that closed off any possibility of interaction.

“Coaching must include a good deal of listening and understanding… If the coach remains too aloof, there would be a kind of emotional distance”. (P6)

“When I was a young faculty… the coach would only criticize, emotionless. And it turned into emotional pressure, you know?” (P8)

“Coaching is a mentorship thing; they are there to help. However, many faculty members are feeling sensitive… Coaches need to be snuggled up with the faculty. If a coach takes away these kids and their attitude is not gentle, and they communicate using official language, many faculty members feel that this is an oversight… That is an emotional unappeal, if anything”. (P9)

“If the coach is too formal or too separated, then it does not feel like support, it feels like judgment. It shuts down any conversation before it even begins”. (P11).

These narratives show that the imposition of formality and status distance resulted in the displacement of collegial problem-solving. Instead, a sense of surveillance was fostered.

Citing P9 and P11, participants expressed a perception of being controlled instead of being helped, and P6 emphasized the need for affective presence and proximity within sensitive pedagogical dialogues. The cost was most pronounced among junior faculty, for whom highly critical, emotionally uncoupled feedback was experienced as demoralizing and high-risk (P8).

4.1.2.1 Interpretation

The coaching style and relationship dynamics were as significant as the content. When the delivery was evaluative—one-sided feedback, scripted discourse, and conspicuous power disparities—faculty disengaged, and the coaching intention of fostering growth was thwarted. In contrast, design aspects that mitigate power differentials (such as a private setting, dialogic discourse, and responsive listening) fostered psychological safety and collective learning, encouraging participants to share openly and take risks.

4.1.2.2 Researcher reflexivity

Initially, I interpreted these responses as mismatches in communication style. However, other instances, where gentle discourse, private talks, and dialogic engagement coexisted, led to free reflection, prompting me to reevaluate the issue as a case of relational design. That is, the presence of formal and distant frameworks functions as supervisor cues that shut down learning, irrespective of the coaches' mastery of content. This pertains to RQ1 regarding perceptions and RQ2 concerning factors that facilitate or hinder the enactment of developmental coaching.

4.1.3 Emotion-based resistance to instructional coaching

Participants articulated emotional barriers not to the concept of coaching itself, but to the way it is framed and experienced, particularly to the formal, hierarchical, and emotionally detached delivery. Instead of collegial assistance, coaching face-to-face often felt like critique, control, and pressure, constricting the willingness to open up.

“When the words ‘instructional coaching' are spoken, many teachers get a bit resistant. They suppose that it has a hierarchical association. When someone from the top descends to check, it feels like they are there to pick holes rather than to collaborate and grow.” (P1)

“In instructional coaching, there is a lot of listening and understanding that goes along with it… But, if the coach looks elsewhere… I will have this feeling of emotional detachment.” (P6)

“…As a young faculty member, if the coach emotionally detached and only criticized, it would give you emotional stress.” (P8)

“By nature, instructional coaching is framed to be supportive. But many faculty are emotionally sensitive. Coaches must be emotionally close to the faculty. If the attitude is formal, many will experience this as supervision… and they will feel powerless.” (P9)

These views indicate that resistance pertains not to the content of feedback, but to the overall relationship climate: defensiveness, feelings of scrutiny, and exposure to public criticism were triggered when colleagues were made to feel distant, treated formally, or communicated with in “official” language (P1, P9). Faculty pointed out that relational presence—visible, warm, and evaluatively neutral emotional interaction—was crucial to accepting coaching. Early-career and senior faculty alike mentioned that without the emotional nuance, criticism became punitive, especially during moments of high stakes (P6, P8). In essence, participants were not rejecting feedback; rather, it was the mode of delivery that seemed impersonal, hierarchical, and detached.

4.1.3.1 Interpretation

Emotional resistance emerged as a consequence of a faculty member feeling the relational, contextual, or evaluative risk a coaching moment presented. Faculty participants disengaged where coaching assumed a hierarchical structure (formal tone, public criticism) and they engaged where coaching displayed a collegial structure (attentive listening, a gentle tone, private context).

4.1.3.2 Researcher reflexivity

As a practitioner, I used to think of resistance as individual sensitivity, but after peer debriefing, I came across negative cases where empathy, privacy, and dialogic exchange resulted in openness. This made me rethink resistance. It is more context dependent and can be considered an adaptive reaction to how coaching is delivered, not an opposition to coaching itself.

4.1.4 Lack of scheduled interaction

Faculty commonly described coaching as intermittent, episodic, and having little follow-up, which limited its potential for development. Instead of a coherent cycle, supervision felt like drop-in visits—brief and with no structure and continuity.

“Some faculty rarely come and meet the rest of us… There is no exchange… let alone… periodical, structured feedback.” (P1)

“Most of the supervisors just come, they sit there, and then they go away—never have time for feedback… and even if there is feedback, it is not systematic.” (P12)

“Supervision is administrative-centered… brief and shallow… They visit your class and then leave… There was no extended follow-up.” (P15)

The lack of predictable structure was evident across narratives—brief goal-setting, observation, followed by a timely debrief with one or two actionable next steps, and a short follow-up. In the absence of this rhythm, the coaching faculty experienced was a series of disjointed events, not a cohesive partnership. As described by P12, one-off observations left instructors without any concrete next steps, and, as P1 described, without a social connection to peers or supervisors. For P15, the absence of a structured process communicated that the focus was administrative, and not on supporting pedagogical development.

4.1.4.1 Interpretation

When there are no unscheduled touchpoints, coaching shifts to a transactional model rather than one focused on development. The learning cycle becomes incomplete, accountability for implementing changes weakens, and the message the faculty receives is that improvement is not an active and shared ongoing concern.

4.1.4.2 Researcher reflexivity

Initially, I thought these gaps were mere differences in schedule. Following peer debriefing and analysis of cases where simple routines (calendared debriefs, written goals, brief check-ins) sparked significant shifts, I now perceive irregularity as a design oversight. In the absence of a deliberate rhythm, even well-intentioned oversight is felt as mere compliance and not as developmental aid (addresses RQ2 in reference to enabling conditions and complements RQ1 on coaching design perceptions).

4.1.5 Summary of results to RQ 1

Instructional coaching was viewed as supervision instead of support, particularly when it was remote, public, unsynchronized with their discipline, and occurred infrequently. Coaching, in those situations, resembled check-ins and fostered a lack of candor and sharing—even when the recommendations were sound. What sparked effort was not the quality of feedback, but how it was given: coaching conversations in private, attentive listening and empathy, contextually relevant advice, and a predictable rhythm (set goals → observe → debrief with 1–2 concrete next steps → brief follow-up). Many faculty became defensive, and the system improvement cycle stalled in the absence of this routine and humane approach. Faculty didn't reject coaching. They simply rejected how it was executed. When coaching was private, empathetic, context-aware, and systematically scheduled, they agreed to open exchanges and the adoption of new strategies.

4.2 Findings related to RQ2: What challenges do faculty perceive in the instructional coaching process?

Analysis of findings about Research Question 2 reveals a set of challenges experienced by faculty, which mainly includes: power imbalances in coach–faculty relationships, inadequate pedagogical support, a lack of empathy and emotional engagement, limited scheduled and sustained interaction, and unclear coaching protocols and role confusion. Together, these issues contributed to the coaching model that faculty experienced as fragmented, directive, and misaligned with their commitments to professional growth.

4.2.1 Power imbalance in coach–faculty relationships

Participants reported that when coaches assumed senior academic or administrative positions, faculty described guarded interactions, uncertainty about the use of comments, and superficial compliance rather than thoughtful disengagement. Coaching shifted from developmental support to formative evaluation.

“It is difficult to see the shift from coaching to an evaluative role, especially when the person with the power to influence your academic career is also your coach.” (P7)

“Within our system, if the one coaching you holds a ranked decision-making position, it becomes challenging to view it as support—it feels like a performance appraisal.” (P11)

“Coaches have too much influence. Even if they mean to help, their rank makes people afraid of messing up in their presence.” (P14)

Role ambiguity in the accounts described coaching and appraisal, with the same person fulfilling both functions.

The “double-hat” arrangement restricted openness, made responses risk-averse and superficial (P3), and created a psychological toll on speaking freely (P14). Even when coaches were perceived to be benevolent, imbalances related to status indicated the likely results and narrowed the room for bold moves (P7, P11).

4.2.1.1 Interpretation

Power imbalances were perceived as evaluative signals. When coaches also controlled resources or assessments, faculty saw the prep sessions as high stakes and shifted their focus from learning to self-preservation. The decisive separation of coaching from evaluation and transparency regarding the feedback's use seem essential for trust and genuine participation.

4.2.1.2 Researcher reflexivity

As a practitioner-researcher, a solo-recorded piece of a session was intended to promote reflexivity and stimulate the process, with a “yes” trigger, while acting as a decoupling mechanism, and a spur of “guardian” feelings. I (and the leader) envisioned the flow as a “squeeze trigger” to “eked out” the process and promote holistic reflexivity. After peer debriefing, it was a lack of decoupled (and thus socially structured) roles (coach ≠ evaluator) on a previous “squeeze trigger session” I intended to promote holistic reflexivity. I now refer to my “squeeze trigger session” as a socially decoupled session to promote holistic reflexivity structured as decoupled roles in a unsustaining system. Evaluative sanction, when placed as a high order to coaching, loses the focus of learning (Address RQ2 on enabling conditions and RQ1).

4.2.2 Inadequate pedagogical support in instructional coaching

Participants from several disciplines described coaching conversations as lacking pedagogical depth. Feedback was described as generic, detached from the classroom, and weakly aligned to disciplinary contexts, providing few actionable suggestions for change. Quotes are kept verbatim. Minor bracketing edits indicate grammar clarification. Translations were checked for fidelity.

“Sometimes I feel [coaches] do not understand the subject, so they focus on superficial things like time control or slide format.” (P2)

“The feedback is nice, but it does not meaningfully help you improve—it feels like a box to check.” (P4)

“They say ‘engage students more,' but give no strategies or examples. It's very vague.” (P6)

“I received general comments—nothing specific to how I was teaching, except one note on a single classroom issue.” (P13)

In the absence of concrete classroom moves, feedback was characterized as formulaic and devoid of method. Faculty described its lack of connection to discipline-specific challenges (e.g., modeling in physics, source analysis in literature) as ‘wishy-washy' feedback that would not change practice (P6, P13). This was perceived as performative compliance (P4). This deficit in content was taken as a lack of coaching discipline knowledge (P2).

The pattern noted was consistent across seniority levels and across departments.

4.2.2.1 Interpretation

When coaching is not discipline-attuned and strategy-focused it fails to close the gap between the principle (“engage students more”) and the practice (“how to do this with this content, tomorrow”). The consequence is low instructional leverage—limited uptake, minimal experimentation, and stalled improvement—even when the intentions are positive.

4.2.2.2 Researcher reflexivity

I initially blamed the dissatisfaction on a desire for what might be perceived as the “quick fixes.” After peer debriefing and analyzing negative cases where discipline-specific modeling, exemplars, and brief rehearsals were in place and produced concrete changes, I reframed the issue to be a lack of pedagogical substance: without content-anchored, action-guided coaching, it is easy to see why the coaching may come across as procedural rather than developmental (this addresses RQ1 on perceptions and informs RQ2 on enabling conditions—discipline attunement and strategy specificity).

4.2.3 Lack of empathy and emotional engagement in coaching

Participants pointed out that besides the content and structure, the emotional tone of the coaching sessions seemed cold, formal, and impersonal which affected trust and honest reflection. What seemed to be lacking was not the technical skill, but the human skill of listening, and the warmth and affirmation that could help build psychological safety.

“Their mode of speech is overly formal. It is not a conversation—it is a notice.” (P1)

“Instructional coaching is about listening and understanding. When the coach is too far, it is a cold story.” (P6)

“Coaches would just criticize. There was no emotion in it. It stressed me out instead of making me feel supported.” (P8)

“Some coaches come, give their comments, and go. It's as though they do not care about the teacher.” (P9)

Coaching was described as coach-led and stiff, with limited relational openness or expressions of care (P1, P6, P9). Faculty reported withholding candor and avoiding risk-taking in coaching situations. Particularly early-career faculty experienced emotionally flat or judgmental feedback as anxiety-inducing rather than supportive (P8). These patterns suggest that it was the coaching delivery rather than the feedback content that affected faculty and how they felt.

Without empathy, affirmation, and authentic engagement, the value that coaching could have brought to development was lost. Some faculty members indicated that the coaching experience was causing them to engage in cautious, surface compliance instead of the hoped-for reflective learning.

4.2.3.1 Interpretation

Emotional disengagement served as a barrier to learning. Faculty cease to engage in risk-taking behaviors, disclosure, and experimentation in sessions that, although theoretically sound, were devoid of emotional and relational elements of attentive listening, warmth, and care. They read and experienced the session as one that was low trust and high risk.

4.2.3.2 Researcher reflexivity

At the start, I understood these responses to be an inherent individual preference for “softer” communication. However, following peer debriefing where I was presented with negative examples and contrasting cases in which brief affirmations were provided, active listening was displayed, and exchanges were empathically framed, I had to shift my understanding of the issue to relational design. Empathetic presence is a developmental coaching essential rather than an optional add-on.

4.2.4 Lack of scheduled and sustained interaction

Participants expressed a lack of regularity, continuity, and integration in coaching, noting that it consisted of isolated and event-based episodes. It was not an ongoing support cycle—coaching involved single observations followed by generic feedback, and there was no follow-through after these observations, making the interactions feel more procedural than developmental.

“Right now, the coach has no system. [They] typically listen to one class and offer some vague advice. There is no follow-up, no ongoing support, and no record that can be added to.” (P5)

“Improving teaching is a dynamic process… I would need the coach to follow up in the next class to see gradual change. But it's one-time feedback, and then they go away.” (P7)

“So, we need a sustained coaching model… It lacks depth, and there's no archive or mechanism to build on.” (P8)

“After the observation, nobody comes to see whether the advice was used or useful. There is no follow-up. It's a one-off thing, not a supportive process.” (P12)

The aggregate reveals the absence of a visible rhythm that followed a simple structure—sets brief goals → observes → debriefs in a timely manner with 1–2 actionable next steps → a pulse check—and integrates a light record of documents to support mastery over time.

In addition to these routines, faculty found next steps, accountability for trying changes, and revisiting and refining practices all ill-defined. Several participants noted the lack of an archive or running record (P5, P8), which limited institutional memory and made sustaining improvements difficult across semesters.

4.2.4.1 Interpretation

The absence of scheduled touchpoints and an unrecorded stream of ongoing documentation tends to shift coaching—as practices are generally understood—to the realm of transactional work and not developmental work: the learning loop closes, experimentation is halted, and the work presents as compliance rather than a supporting activity for growth.

4.2.4.2 Researcher reflexivity

I first rationalized the irregularity as being due to workload constraints. After a peer debrief and within-case analysis, where calendarized debriefs, written micro-goals, and brief check-ins fostered steady gains, I shifted this thinking to the issue of design: formation of a structured cadence and record-keeping. Even well-intentioned oversight is perceived as episodic and non-developmental (connects to RQ1 on perceptions and informs RQ2 on enabling conditions- cadence and continuity- for effective coaching).

4.2.5 Unclear coaching protocols and role confusion

Participants referred to inconsistencies in coaching protocols and described siloed coaching roles. This ambiguity created uncertainty regarding expectations, goals, and boundaries. Communication and feedback fell outside coaching practices giving rise to incongruities and uncertainty around the activity being evaluative, developmental, or both. This lack of transparency impeded trust.

“Sometimes I don't even know what the coach is supposed to do. Are they evaluating me? Helping me? Reporting to someone else? No one explained it clearly.” (P3)

“There is too much overlap between supervision and coaching. I cannot tell where one ends and the other begins. It just feels like another layer of control.” (P10)

“The problem is that every coach does it differently. Some give very detailed suggestions, others just say ‘good job' and leave. There is no standard, no protocol.” (P11)

Across accounts, the ambiguity around roles (coach vs. evaluator), and the interdependence of processes (observations, debriefing, and follow-up) created a moving target. In the absence of clearly defined coaching practices, it was construed as administrative oversight. The result was compliance of a superficial kind rather than reflective and engaged collaboration.

Participants voiced the importance of purposeful statements, protocols that can be standardized yet flexible, and defined boundaries that separate coaching from appraisal.

4.2.5.1 Interpretation

An unclear purpose and role confusion serve as evaluative cues: if faculty members are unsure whether feedback is developmental or evaluative, they will likely prioritize risk management over learning. Trust, predictability, and uptake necess shared minimal protocols and role clarity.

4.2.5.2 Researcher Reflexivity

I first interpreted the lack of action as a desire to not change. After a round of peer debriefing and considering situations with stated purpose, documented protocols, and role decoupling (coach ≠ evaluator) where I observed the most engagement, I recognized that clarity around the why, how, and who of a task dramatically shifted perception from control to support (links to RQ1 on perceptions; informs RQ2 on enabling conditions—role clarity and transparent protocols).

4.2.6 Summary of findings to RQ2

Across cases, whether coaching functioned as developmental support or was read as evaluation hinged on several design conditions. Importantly, the distinction between coaching as support and appraisal reporting was enough to evoke a sense of safety. There also had to be some content, discipline-appropriate, strategy-specific guidance to help teachers translate the principle to practice in the classroom. Furthermore, emotionally attuned delivery (listening, warmth, affirmation) promoted psychological safety, while emotional detachment encouraged retrieval to a protective stance. Moreover, the learning loop was sustained by scheduled predictability in the cadence (brief goal-setting → observation → on-time debrief with 1–2 actionable steps → brief follow-up) and light documentation. In the end, explicit protocols and role clarity fostered agency by removing barriers. In the absence of these conditions, the faculty defaulted to guarding their risks (silence, minimal compliance, and procedural inactivity). In the presence of those conditions, the faculty articulated trust, openness, and risk-taking, feeling coaching was a true driver of growth in their instruction.

5 Discussion

Guided by Institutional Theory and Social Constructivism, this research explored the sense-making processes of faculty at a status-dense, under-resourced Chinese university about instructional coaching (RQ1) and the potential enablers and inhibitors of developmentally engaged coaching (RQ2). The unfolding of coaching, rather than its policy intent, seems to determine faculty positioning. Supervisory signals (e.g., public critique, role overlap with evaluation, formal tone, episodic contact) triggered guarded compliance, while developmental signals (e.g., privacy, empathy, discipline-specific feedback, and scheduled continuity) initiated trust and active participation. In this case, expansion of the coaching cycle to include episodic coaching seems to correspond with a developmental engagement mindset, thereby, a willingness to abscond with normative expectations. The developmental coaching literature, particularly the coaching cycle, anticipates this kind of engagement, and this integration of episodic coaching is a reasonable expansion of the coaching norm. The integration of insights from this study extends the policy discourse on coaching, as the elaboration indicates that coaching operates at multiple levels, thereby broadening its implications.

5.1 Interpreting coaching in hierarchical settings (RQ1)

Faculty consistently perceived instructional coaching as a form of bureaucratic surveillance without the potential for peer support, a finding resonating with both domestic and international contexts (Xu and Wang, 2023; Warnock et al., 2022). Prior research shows that psychological safety is a fundamental precondition for the reflective practice of teaching; when public evaluators provide feedback, fear of negative appraisal and symbolic compliance are triggered (Knight, 2019; Jiang and Liu, 2022). In contexts of strong hierarchical and evaluative performance cultures, the study illustrates the study amplifying this dynamic. This sequence of institutional orders, hierarchies, and culture, is explained by idle institutionalism (Meyer and Rowan, 1991; DiMaggio and Powell, 1991). Coaching embedded in formal appraisal systems significantly diminishes its developmental aspect, therefore, becoming a mere ceremonial practice.

This phenomenon is explained by Institutional Theory (Meyer and Rowan, 1991; DiMaggio and Powell, 1991): once coaching is integrated with formal appraisal systems, it becomes a mere ritual, losing its developmental purpose, and passes as a ceremonial practice.

Our study's faculty narratives illustrate this symbolic decoupling, where coaching is externally accepted, but, internally, it is seen more as over-scrutinizing something that is risky. At the same time, national policies, such as the Ministry of Education's (2020) reform directives, do underline ‘scientific' and formative evaluation but give local institutions a lot of interpretive latitude, which more often than not leads to surface-level implementation (Huang and Zhao, 2022).

From a constructivist perspective, meaning is the result of interaction and co-construction. Our data show that coaching that is warm, private, and dialogic—as opposed to the formal, public, and hierarchical structures—fosters deeper authentic reflection (Desimone, 2009; Liu and Zhang, 2021). Even while the feedback was critical, the relational style of delivery influenced the perception of feedback as punitive or supportive. This emphasizes the point that the interactional climate is central, not peripheral, to coaching outcomes.

5.2 Conditions that convert intent into impact (RQ2)

Five enabling conditions emerged as critical in transforming coaching from symbolic compliance to meaningful developmental practice.

First, role decoupling became indispensable. When coaches had evaluative power, coaching sessions became high-stakes, provoking defensive discourse and hindering risk-taking. Faculty preferred coaches who were not enforcers of administrative control, which aligns with research suggesting that power neutrality fosters workplace psychological safety (Brookhart, 2022; Zhang et al., 2023).

Second, the presence of pedagogical substance—especially discipline-specific strategies—was critical. Generic feedback (e.g., “engage students more”) remained instructionally ineffective unless it was accompanied by actionable suggestions that aligned with the discipline. This finding resonates with Mangin and Dunsmore's (2015) assertion that coaching should be contextually anchored to facilitate instructional change. Recent studies from China similarly point out that discipline misalignment weakens trust and the willingness to implement suggestions (Wang and Li, 2023).

Third, emotional presence played a role. Empathy, listening, and affirming acts lessened the emotional challenges coaching placed, especially for younger faculty. This perspective reinforces Knight's (2019) assertion that relational trust is the foundation of coaching, as it is bolstered by research from East Asia, where the hierarchical social architecture disincentivizes emotional vulnerability (Lee, 2021).

Fourth, coaching needed to follow a systematic, scheduled rhythm: brief goal-setting, observation, targeted debrief, and follow-up.

To cultivate habits and iterative growth, participants emphasize the importance of continuity. This emphasis further develops Desimone's (2009) professional learning model to include cadence as an essential component of delivery.

Clarity of roles and protocols provided more structure and less ambiguity. When coaching was unscripted and the evaluators' boundaries were unclear, faculty behaviors became defensive and reflexive. This is consistent with the literature concerning role ambiguity and subsequent resistance (Huang and Zhao, 2022) as well as the reform documented in more transparent and non-punitive coaching systems (Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China, 2020) designed to address the documented resistance.

These five conditions cumulatively and qualitatively enhance Desimone's (2009) core principles of faculty development in the more hierarchical and less developed settings. In doing so, they expand on the principles of content focus, active learning, coherence, and duration, to include the more relational and structural elements of role neutrality, cadence, discipline attunement, empathy, and flexible pacing.

5.3 Theoretical and institutional implications

This study, informed by Institutional Theory, describes how, in the case of formal coaching programs, legitimacy performances occur as a result of the overshadowing of development intent by symbolic structures, such as top-down roles, and public observations. In such instances, coaching may be more about preserving the organization's equilibrium than fostering a radical shift in teaching (Meyer and Rowan, 1991; DiMaggio and Powell, 1991). Conversely, Social Constructivism offers a possible counterbalance; even within hierarchical structures, faculty may come to view coaching as supportive when they experience coaching as a relational, context-sensitive, and dialogic process (Desimone, 2009; Knight, 2019).

For faculty development in institutions with limited resources, such as those in Gansu Province, these insights suggest possible improvements. First, coaching must be structurally segregated from formal appraisal systems to allow engagement with low risk. Second, the training of coaches, particularly where hierarchy tends to stifle communication, should prioritize the presence of empathy and emotional engagement. Third, having coaches and faculty in the same discipline can enhance the credibility and relevance of the feedback and instructions. Fourth, institutions should introduce light, routine coaching cycles (e.g., observe → debrief → follow-up) to help sustain momentum. Lastly, unambiguous and definitive protocols as well as role descriptions help eliminate uncertainty and bolster coaching as support rather than scrutiny.

These are not just technical solutions; they comprise core elements to transform coaching from a compliance activity to a powerful developmental resource, especially where hierarchy, scarcity, and performance pressure strongly influence and diminish the educational purpose.

5.4 Limitations and directions

This study's design focused on single-site qualitative research. While in-depth studies provide rich data, future research will require research sampling beyond this study. An important next step will be examining the coaching practices of university coaches situated in different resource environments to include varying coaching hierarchical intensities. Multiple longitudinal studies could be designed to assess the extent to which faculty outcomes change over time as certain coaching practices are implemented or adjusted (i.e., role separation, coaching frequency). With the increase of digital technologies in coaching, the use of digital technologies in coaching should be studied to ascertain efficiency in providing actionable feedback while avoiding feedback loops that create the kind of surveillance that Brookhart (2022) and Liu and Zhang (2021) argue harms psychological safety.

6 Conclusion

Regarding Research Question 1, faculty in a hierarchical, resource-constrained university mostly viewed coaching in a supervisory role as opposed to a developmental one. Public or scripted interactions, unclear functions, and overt status differentials eroded psychological safety, promoting surface compliance instead of meaningful learning.

In relation to Research Question 2, engagement was hindered by three intersecting barriers: structural (e.g., heavy workloads, inflexible schedules, and scant assistance), relational (i.e., low trust and coaches being evaluators), and cultural (i.e., face-saving norms and indirect criticism). Together, these elements repositioned feedback as a form of appraisal and collaboration as control.

To ensure coaching has a developmental purpose, institutions can separate real-time supervision and evaluation through clear, indirect reporting lines, and performance scores should not appear on coaching documents. Role expectations and confidentiality should be clarified through a charter that outlines goals, boundaries, data ownership, and conditions around opt out. Administrative coverage should ensure there is dedicated time for the observe-debrief-plan cycles. Brief pre-meetings should be held to establish the content focus and success criteria. Debriefs should be private and dialogic and should align with inquiry protocols, active listening, and strong culturally relevant feedback. In high power distance contexts, the risk of engagement can be lowered through peer or mentorship models.

Focus on formative progress indicators like participation, quality of goals, iterations of changes in teaching, and psychological safety instead of summative indicators.

This research offers a contextually grounded understanding of how institutional logics and everyday interactions shape faculty perceptions of coaching within non-Western higher education. Although the findings are limited to one institution and only one role group, they provide actionable design levers for reform. Future multi-site, cross-role, and longitudinal research can assess the decoupling and trust-building mechanisms' durability and further develop a scalable, contextually sensitive coaching model.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee/IRB: Scientific Research Committee, Tianshui Normal University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ZL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. NC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdallah, L. N., and Forawi, S. A. (2017). Investigating leadership styles and their impact on the success of educational institutions. Int. J. Educ. Org. Leadersh. 24, 19–30. doi: 10.18848/2329-1656/CGP/v24i02/19-30

Advance HE. (2023). Professional Standards Framework for Teaching and Supporting Learning in Higher Education (PSF 2023). Advance HE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/teaching-learning/professional-standards-framework

Bedford, L. A. (2022). Coaching for Professional Development for Online Higher Education Faculty: An Explanatory Case Study (Doctoral dissertation). Northcentral University, Prescott, AZ, USA.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brookhart, S. M. (2022). How to Give Effective Feedback to Your Students (2nd Edn.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Burleigh, C. L., Kroposki, M., Steele, P. B., Smith, S. D., and Murray, D. (2022). Coaching and teaching performance in higher education: a literature review. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 11, 285–299. doi: 10.1108/IJMCE-06-2022-0041

Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and State Council of the People's Republic of China. (2020). 深化新时代教育评价改革总体方案 [Overall Plan for Deepening the Reform of Education Evaluation in the New Era]. The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China. Available online at: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-10/13/content_5551032.htm

Coburn, C. E., and Woulfin, S. L. (2012). Reading coaches and the relationship between policy and practice. Read. Res. Q. 47, 5–30. doi: 10.1002/RRQ.008

Culver, K., Kezar, A. J., and Koren, E. R. (2023). Improving access and inclusion for VITAL faculty in the scholarship of teaching and learning through sustained professional development programs. Innov. High. Educ. 48, 567–584. doi: 10.1007/s10755-023-09672-7

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers' professional development: toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educ. Res. 38, 181–199. doi: 10.3102/0013189X08331140

DiMaggio, P. J., and Powell, W. W. (1991). “The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields,” in The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, eds. W. W. Powell and P. J. DiMaggio (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 63–82. (Original work published 1983).

Gallucci, C., Van Lare, M. D., Yoon, I. H., and Boatright, B. (2010). Instructional coaching: building theory about the role and organizational support for professional learning. Am. Educ. Res. J. 47, 919–963. doi: 10.3102/0002831210371497

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Huang, C-. K. (2023). Coaching for change: Preparing mathematics teachers for technology integration in differentiated classrooms. Educ. Inform. Technol. 28, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-11684-x

Huang, Y., and Zhao, Y. (2022). Evaluating teaching quality in Chinese higher education: tensions between developmental aims and institutional constraints. J. Educ. Adminis. Policy Stud. 14, 45–60. doi: 10.5897/JEDAPS2022.0423

Jaafar, R., and Cuellar, M. (2024). Bridging equity gaps: Faculty development through data coaching. Commun. College J. Res. Pract. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2024.2430382

Jiang, H., and Liu, X. (2022). Instructional coaching in Chinese universities: Faculty perceptions and institutional dynamics. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 23, 113–127. doi: 10.1007/s12564-021-09743-7

Jiang, L., Zhang, L., and May, S. (2019). Implementing English-medium instruction (EMI) in China: Teachers' practices and perceptions, and students' learning motivation and needs. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 22, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2016.1231166

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., and Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031

Knight, J. (2019). The Impact Cycle: What Instructional Coaches Should Do to Foster Powerful Improvements in Teaching. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., and Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: a meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 88, 547–588. doi: 10.3102/0034654318759268

Lee, J. (2021). Trust and hierarchy in East Asian faculty development: lessons from South Korea. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 26, 248–260. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2021.1888490

Liu, Y., and Zhang, W. (2021). Coaching with care: creating psychologically safe feedback environments in Chinese higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 26, 655–670. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1828201

Lofthouse, R. (2018). Coaching in education: a professional development process in formation. Prof. Dev. Educ. 44, 276–289. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2017.1310547

Lofthouse, R., and Wright, D. G. (2012). Teacher education lesson observation as boundary crossing. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 1, 89–103. doi: 10.1108/20466851211262842

Mangin, M. M., and Dunsmore, K. (2015). How the framing of instructional coaching as a professional development strategy matters. Educ. Adminis. Q. 51, 179–213. doi: 10.1177/0013161X14522814

Meyer, J. W., and Rowan, B. (1991). “Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony,” in The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, eds. W. W. Powell and P. J. DiMaggio (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 41–62. (Original work published 1977).

Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (2020). Overall Plan for Deepening the Reform of Education Evaluation in the New Era [in Chinese]. Available online at: http://www.moe.gov.cn

Reddy, L. A., Glover, T., Kurz, A., and Elliott, S. N. (2019). Assessing the effectiveness and interactions of instructional coaches: initial psychometric evidence for the Instructional Coaching Assessments-Teacher Forms. Assess. Effect. Interv. 44, 104–119. doi: 10.1177/1534508418771739

Shadle, S., Marker, A., and Earl, B. (2017). Faculty drivers and barriers: laying the groundwork for undergraduate STEM education reform in academic departments. Int. J. STEM Educ. 4:8. doi: 10.1186/s40594-017-0062-7

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative Analysis for Social Scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sunal, D. W., Hodges, J., Sunal, C. S., Whitaker, K. W., Freeman, L. M., Edwards, L., et al. (2001). Teaching science in higher education: faculty professional development and barriers to change. Sch. Sci. Math. 101, 246–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1949-8594.2001.tb18027.x

UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. UNESCO. doi: 10.54675/ASRB4722

Wang, J., and Li, M. (2023). Discipline-specific instructional coaching in Chinese universities: faculty needs and perceptions. Front. Educ. China 18, 1–19.

Warnock, T., Van Nuland, S., and Morrison, M. (2022). Coaching with compassion: building trust and improving instruction in higher education. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 11, 375–390. doi: 10.1108/IJMCE-01-2021-0030

Xu, L., and Wang, H. (2023). Instructional reform through coaching: a qualitative study of faculty development in Chinese universities. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 42, 501–517.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th Edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Zhang, Y., Chen, L., and Hu, J. (2023). Faculty resistance to instructional coaching in Chinese higher education: a power-relations perspective. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 45, 173–189.

Keywords: instructional coaching, faculty perceptions, surveillance culture, power distance, resource-constrained university in China

Citation: Liu Z, Sulaiman T and Che Nawi NR (2025) Between development and surveillance: faculty perceptions and challenges of instructional coaching in an underdeveloped university context. Front. Educ. 10:1637546. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1637546

Received: 06 June 2025; Accepted: 30 September 2025;

Published: 17 November 2025.

Edited by:

Niroj Dahal, Kathmandu University School of Education, NepalReviewed by:

Supot Rattanapun, Rajamangala University of Technology Krungthep, ThailandLaxmi Sharma, Kathmandu University School of Education, Nepal

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Sulaiman and Che Nawi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tajularipin Sulaiman, dGFqdWxhc0B1cG0uZWR1Lm15

Zhiming Liu

Zhiming Liu Tajularipin Sulaiman2*

Tajularipin Sulaiman2* Nur Raihan Che Nawi

Nur Raihan Che Nawi