- Language, Literacy, & Culture Doctoral Program, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD, United States

Adult learners are one of the largest growing populations on college campuses. However, many universities do not consider this population generally and Black male adult learners specifically in policy decisions. To address this oversight there has been a growing body of work exploring the experiences of Black male adult learners in higher education, but most theories used to study this population were developed for traditional aged college students. Given the differences in the experiences of Black male adult learners, I developed the Black Male Adult Learner Success Theory (BMALST) to present an asset-based lens in which to study and make institutional decisions that cultivate the academic success of Black male adult learners. In this article I present the journey to developing the BMALST, describe the theory, and discuss how it could be used by institutions to improve the experience for Black male adult learners in higher education.

Introduction

Rahim: “I might not be a good fit for your study.”

Me: Why?

Rahim: I'm 61 years old!

This interaction with Rahim happened a little over 10 years ago as I was collecting data for my dissertation which explored the experiences of academically successful Black men at a historically Black college and university (HBCU; Goings, 2015). When I first met Rahim, he was a graduating senior construction management major, 62 years old, father of 15 children, and had made millions in the construction industry. Because of his motivation as a youth being centered on making money, he described school having “no value.” Consequently, he dropped out of school in the 8th grade to pursue employment and later would serve in the military as an engineer. As a Black adult he felt it was his duty to come back to his hometown, earn his degree at a HBCU so that all of his accolades would be connected to his alma mater. While he did not need the credential for employment opportunities, he self-described him having the “Bill Gates effect” where he was an expert in his field but due to not having a degree, he would not be allowed to teach the youth what he knew about construction.

When describing Rahim's background during research talks I give at colleges and universities the typical reaction I get is astonishment for him being an older student and still pursuing his degree. I also held a similar reaction when he reached out. When I first interacted with Rahim and several other older students like him in my foundational work, I did what most doctoral students do, I went back to the literature to see what I could understand about older students in college, and while there were studies about this population of students referred to as non-traditional, post-traditional, and/or adult learners (see Gulley, 2021 for a discussion on the implications of terminology), once I added Black and male to my search terms there was very few sources on the population at the time (e.g., Drayton et al., 2016; Rosser-Mims et al., 2014a; Spradley, 2001). For the purposes of this paper I define the term adult learner as a student who is 25 years or older and has one of the following characteristics identified by Horn and Carroll (1996): (1) delayed enrollment in college; (2) attending college part-time; (3) having financial independence; (4) working full-time while taking classes; (5) responsible for dependents (other than spouse); (6) a single parent, and/or; (7) obtaining a high school diploma through an alternative route. However, generally adult learners are one of the largest growing student groups on college campuses with ~38% of students fitting into being an adult learner based on their age alone (Gulley, 2021).

After my experience with Rahim and then understanding the paucity of literature on Black male adult learners I started to reflect on the following three questions:

1. If we truly believe that theory informs practice, what is happening across the university setting to support Black male adult learners if there is no theory or insights about this population being generated?

2. How can we ensure systems within an institution are equitable if certain populations of students are not even on the radars of decision makers?

3. Given the ways that Black men are often valued for their athletic prowess and not their academic ability, how can institutions and institutional actors be equipped to support Black male adult learners when there are very few asset-oriented models to base their decisions from?

When reflecting on my prior research and experiences as a Black male who played basketball in college, I would argue that Black male collegians are uniquely positioned within higher education organizations. For instance, Black male athletes have immense value to institutions when considering the billions of dollars they generate via ticket and merchandise sales, and television deals (Tatos and Singer, 2021). Moreover, due to data from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) that shows < 38% of first-time Black male undergraduates graduate within a 6-year time frame across public, private, and for-profit institutions (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2016) there have been clarion calls from policy makers to support the retention and graduation of Black males. In many ways institutions profit from the current plight of Black men in higher education. However, despite the value Black men hold to institutions their academic pursuits and outcomes are framed and studied from a deficit thinking perspective. When discussing this deficit perspective I borrow from Valencia (1997) who defined deficit thinking as a framing which, “holds that poor schooling performance is rooted in students' alleged cognitive and motivation deficits while institutional structures and inequitable school that exclude students from learning are held exculpatory” (p. 9).

Consequently, due to Black male adult learners also being discussed from a deficit perspective, I sought to develop a theoretical model that colleges and universities could use that was grounded in an asset-based view. If institutions recognize that they want to be more inclusive to adult learners generally and Black male adult learners specifically, then there must be a shift from solely teaching the students the rules to navigating higher education to taking a systemic look at policies and practices that could be changed and/or implemented to ensure the institution is more responsive to the student needs. Thus, the Black Male Adult Learner Success Theory (BMALST; Goings, 2021) was created as a theoretical framing for institutions to use to center Black male adult learners from an asset-based perspective.

In this article I present the Black Male Adult Learner Success Theory as a model for institutions to consider and explore how it can be applied to address certain policies and practices on campus that if addressed systemically would ensure the retention of Black male adult learners. To contextualize the BMALST framework, I first provide a brief overview of literature on Black male adult learners specifically.

Academic success of Black male adult learners in higher education

When exploring the growing body of literature on Black male adult learners, scholars have explored individual, social-familial, and institutional level factors that have influenced their academic and social experiences on campus. At the individual level, several researchers have attributed the academic success Black male adult learners to their intrinsic motivation (Goings, 2016c, 2018; Goings et al., 2018; Jackson, 2021; Rosser-Mims et al., 2014b), being spiritually grounded (Goings and Hunt, 2023), and willingness to standout as Black men on campus (Goings, 2017a). One interesting aspect around the Black male adult learner experience in college has been how these men stand out and the consequences (both positive and negative of doing so). For example, Goings (2017b) conducted a comparison study of the experiences traditional aged college students (18–22) and adult learners (25 and over) and with interacting with faculty on campus. Findings from this study suggested that for older students they had to implement a strategy referred to as “Not Outshining the Master” to carefully navigate how they engaged in classroom conversations with faculty when they had more practical experience in the area they were studying than the faculty member.

At the socio-familial level, researchers have found that Black male adult learners were successful due to their family support network (Goings, 2016a) and peers on campus (Goings, 2015). While research on traditional aged Black male collegians too mirror similar findings (e.g., Davis et al., 2018), one caveat for adult learners is the role of their children on their academics. In Goings (2015) several of the participants noted the importance their children played in pushing them to go back to school. For some participants, they explained how their children would pose some form of the question: “well if you are telling me education is important and I need a college degree, why don't you have one?” This type of questioning from their children pushed men in this study to re-enroll and succeed academically to set the expectation for their family.

Along with family, other Black male peers on campus have been found to be impactful for the success of adult learners (Goings, 2018; Jackson, 2021). While adult learning scholars explain that adult learners have very different needs and expectations than traditional college students (Kenner and Weinerman, 2011), the literature on Black male adult learners shows how these men benefit from interactions with their fellow adult learners and younger collegians. Findings from Goings (2016a) described a “two-way” support system where Black male adult learners who glean insights from their classmates and they found opportunities to serve as mentors in particular to the younger students in their classes.

Lastly, while limited in scope there have been some studies to explore institutional level factors that influence the trajectory of Black male adult learners in higher education. First, scholars have found that there tends to be differences generally for this group based on whether they attend a PWI or HBCU. For Black men at HBCUs they have been found to encounter a warm institutional environment that fosters their academic success (Goings, 2015, 2016a,b). However, at PWIs Black male adult learners can face a racially hostile and/or unwelcoming environment (Jackson, 2021). Additionally, several studies have suggested Black male adult learners have inconsistent experiences accessing and using campus resources. Jackson (2021) found in his qualitative study that Black male adult learners found that many university services and events were not designed with them in mind, thus they often felt a sense of being bothered on campus.

Overview of the Black Male Adult Learner Success Theory

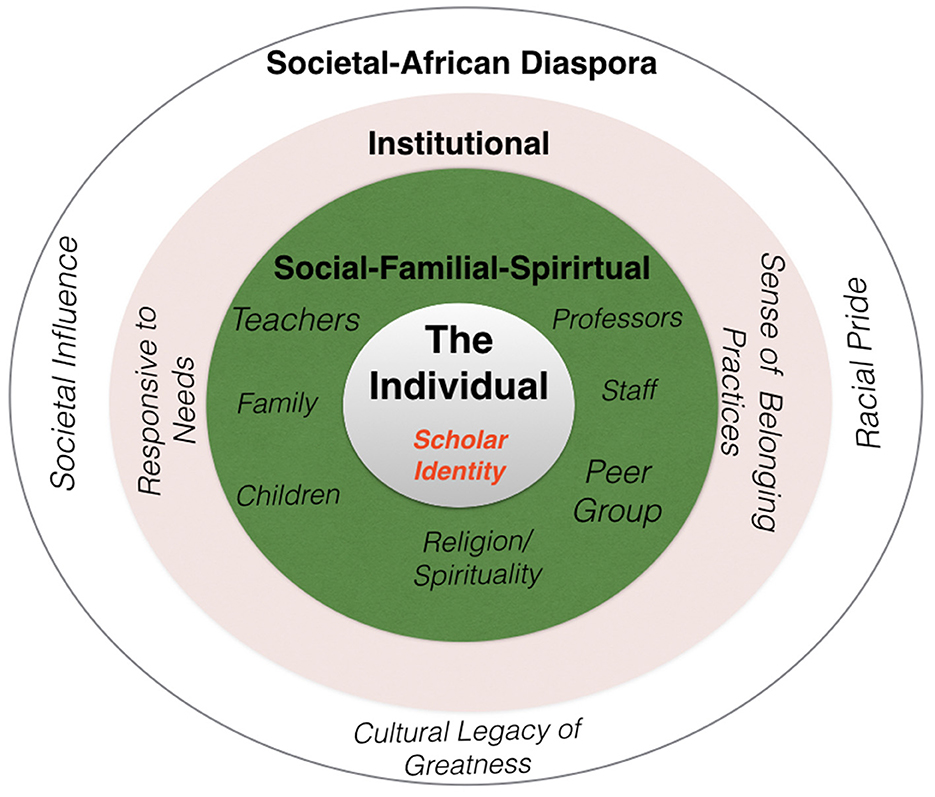

BMALST was initially developed after several years of having to pull from several asset-based theories that explained the success of Black men in society (Bush and Bush, 2013), community college settings (Wood and Harris, 2014) and 4-year college/university settings (e.g., Harper, 2010, 2012; Palmer et al., 2016). While this work was germane to my understanding, I started to find some nuances to the adult learner experience that were not at the foundation of these theories, which led to the construction of BMALST. As a model to examine the unique experiences of Black male adult learners in higher education and the impact of their various environments on their academic success, BMALST (see Figure 1 diagram) is guided by the following two assumptions:

1. Black male adult learners develop a scholar identity that ultimately positively influences their academic success.

2. Black male adult learners' social-familial-spiritual, institutional, and African diaspora environments influence the development of their scholar identity and ultimately, their academic success.

Figure 1. Black Male Adult Learner Success Theory model. Reprinted with permission from Adult Education Quarterly, 2021, Vol. 71(2), p. 136. © Ramon Goings 2020.

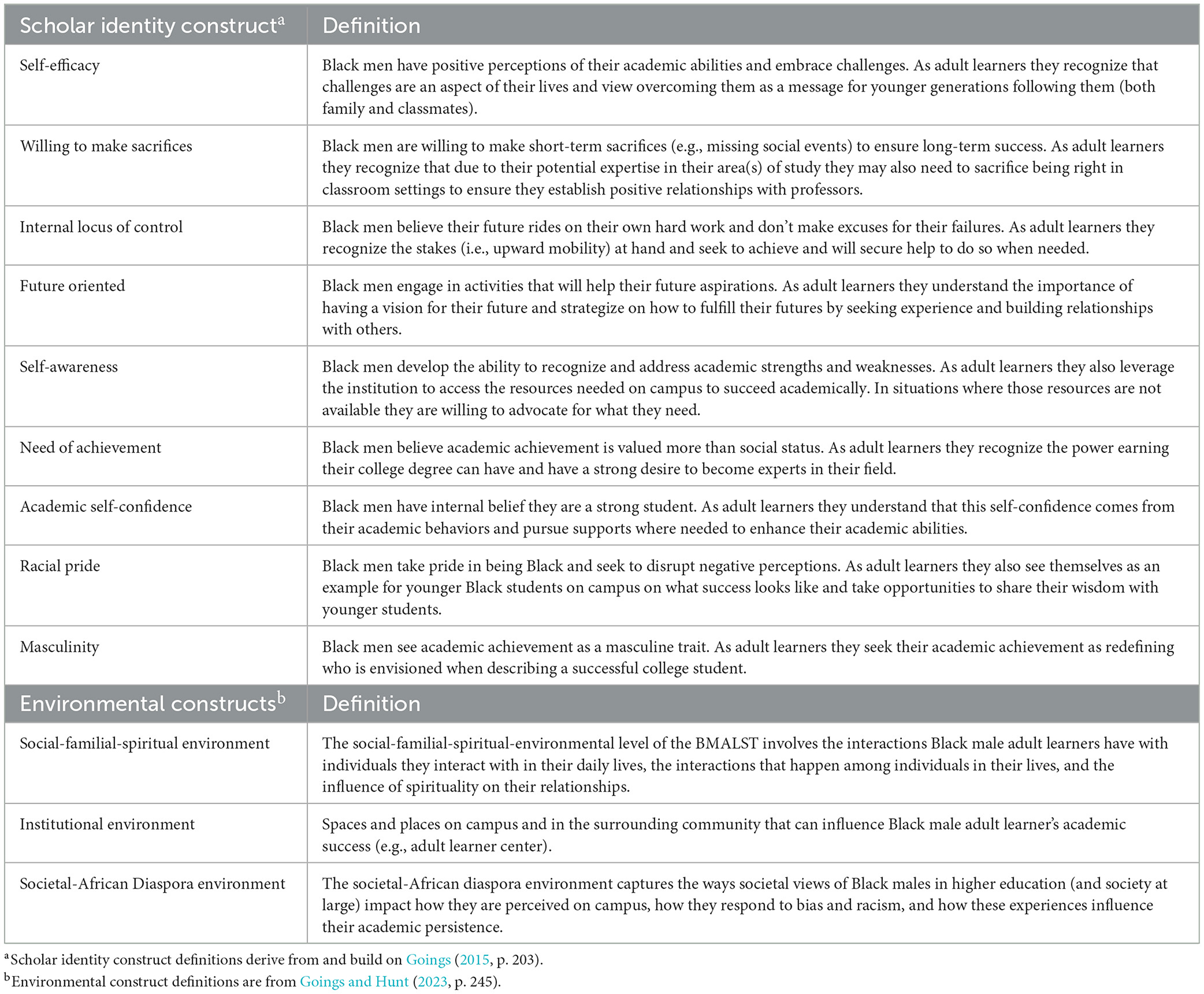

BMALST builds on Whiting's (2009a,b) scholar identity model (SIM) and Bronfenbrenner's (1979) bioecological systems theory (BST). While I will describe the constructs of the theory in a linear fashion it must be noted that various environmental factors influence how Black men develop a scholar identity (see Table 1 for definitions) and how they succeed academically.

Scholar identity model (SIM)

The SIM was developed by Gilman Whiting as an asset-based model to support the development of academic giftedness in Black boys in K-12 settings. However, as discussed in my past work (Goings, 2015, 2016a,b), scholar identity does not leave Black boys as they get older but stays with them through adulthood. Scholar identity is defined as Black boys (and men for BMALST) as someone who is “perceiving themselves as academicians, as studious, and as intelligent or talented in school settings” (Whiting, 2006b, p. 227). Furthermore, scholar identity is comprised of the following nine constructs: (1) self-efficacy; (2) willing to make sacrifices; (3) internal locus of control; (4) future oriented; (5) self-awareness; (6) need for achievement; (7) academic self-confidence; (8) racial pride; and (9) masculinity. For the purposes of space Table 1 provides a definition of each scholar identity construct (see Whiting, 2006a,b, 2009a,b, 2014 for a detailed description of each construct).

The BMALST environment to cultivate scholar identity

While developing a scholar identity is at the core of BMALST, I learned from researching Black male adult learners that the various environments in which they navigate were critical to their scholar identity development. Thus, BMALST borrows from and builds on Bronfenbrenner's (1979) bioecological system theory (BST). As Bronfenbrenner explains, “Seldom is attention paid to the person's behavior in more than one setting or to the way in which relations between settings can affect what happens to them” (p. 18). Given the influence of an individual's environment at various levels, the depiction of the BMALST (see Figure 1) uses concentric circles to represent the interconnectedness of an individual's various environments that influence their behavior. For the purposes of the BMALST, I have adapted new names for each of his nested environments. These names are derived from the environmental factors of success found in previous literature on Black male adult learners. Table 1 provides the names and definitions for each environmental construct (see Goings, 2021 for a more detailed explanation).

Discussion

One of the unique challenges facing adult learners generally and a Black male adult learner specifically is that they are sometimes an afterthought in policy decisions. One of the reasons for this is that institutions typically do not collect and/or report data about their adult learner populations in meaningful ways to inform institutional level decisions. Thus, through using BMALST as a lens there is an opportunity to improve the institutional environment for Black male adult learners by truly understanding their experiences on campus and gaining insights from the institutional members (e.g., admissions counselors, academic advisers, etc.) on how they approach working with this population. One example of this is the Adult Learner Initiative which was funded by the Lumina Foundation as a capacity building project for five HBCUs in North Carolina to “implement politics, programs, and initiative for Black adult learners” (Copridge et al., 2024, p. 5).

When considering developing initiatives, institutions must understand some of the nuances of their adult learning population. First, adult learners more than ever are looking for more flexible education options (Gardner et al., 2022). Consequently, we are seeing growth in enrollment at online universities (i.e., Walden University, Capella University, etc.) and the rapid birth of online and/or hybrid programs at traditionally brick-and-mortar universities. However, how do these universities and programs truly consider the learning styles (outside of course delivery modality) and lived experiences of their adult learners when designing curricular offerings? Moreover, how do we create online environments where Black male adult learners are welcomed and feel that they have adequate access to resources to be academically successful?

Adult learners come to campus with various backgrounds that may impact their retention and graduation. When describing adult learners Horn and Carroll (1996) noted that when describing this student group, they could also be characterized by how many non-traditional student characteristics they had. The authors developed three classifications as students who are: minimally non-traditional (one characteristic), moderately non-traditional (2 or 3 characteristics), or highly non-traditional (4 or more characteristics). This distinction is important to note because universities should collect data on all 7 of Horn and Carrol's adult learner student characteristics so that they can begin to analyze enrollment and retention data to address questions like: Are there differences in the first-year retention of Black male adult learners who are minimally, moderately, or highly nontraditional? What is the relationship between non-traditional classification and likelihood to participate in campus sponsored activities?

Lastly, BMALST provides a lens in which to look at advising practices on college campuses. This is important as myself (Goings, 2018) and Jackson (2021) found the need for advising to be more culturally responsive to the needs of Black male adult learners. I argued previously (i.e., Goings, 2018) that Black male adult learners need advisers whose entire unit encompasses a presence as a cultural navigator which Strayhorn (2015) described as “individuals who strive to help students move successfully through education and life” (p. 59). Furthermore, through a BMALST lens I would contend that cultural navigators also support the development and refinement of Black men's scholar identity.

While the exploration of Black male adult learners in higher education is at its infancy there is much opportunity for institutions to better support this population. However, there needs to be a shift in focusing on institutional structures being improved rather than solely trying to provide Black men with the knowledge of the hidden curricula (i.e., unspoken policies and practices) to navigate colleges and universities. In essence, I would like for my participant Rahim to not feel like an outsider on campus being older in age because colleges and universities embrace and provide the support for students like him to flourish.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. The participants mentioned in this study provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bush, L., and Bush, E. C. (2013). Introducing African American male theory (AAMT). J. Afr. Am. Males Educ. 4, 6–17.

Copridge, K. W., Njoku, N. R., Norris, Y., Slaughter, K. F., Emery-Kuaho, J., and Laster, A. (2024). HBCU adult learner initiative external report. Available online at: https://www.luminafoundation.org/resource/hbcu-adult-learner-initiative/ (Accessed May 14, 2025).

Davis, J., Long, L., Green, S., Crawford, Y., and Blackwood, J. (2018). An in-depth case study of a prospective Black male teacher candidate with an undisclosed disability at a historically Black college and university. J. Res. Init. 3, 1–18.

Drayton, B., Rosser-Mims, D., Schwartz, J., and Guy, T. C., (eds.). (2016). “Swimming upstream 2: agency and urgency in the education of Black men [Special issue],” in New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education.

Gardner, A. C., Maietta, H. N., Garner, P. D., and Perkins, N. (2022). Online postsecondary adult learners: an analysis of adult learner characteristics and online course taking preferences. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 36, 176–192. doi: 10.1080/08923647.2021.1928434

Goings, R. B. (2015). High-achieving African American males at one historically Black university: a phenomenological study. (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest (10076271).

Goings, R. B. (2016a). (Re)Defining the narrative: high-achieving nontraditional Black male undergraduates at a historically Black college and university. Adult Educ. Quart. 66, 237–253. doi: 10.1177/0741713616644776

Goings, R. B. (2016b). Supporting high-achieving nontraditional Black male undergraduates: implications for theory, policy, and practice. Urban Educ. Res. Policy Ann. 4, 9–16. doi: 10.55370/uerpa.v4i1.420

Goings, R. B. (2016c). Investigating the experiences of two high-achieving Black male HBCU graduates: an exploratory study. Negro Educ. Rev. 4, 54–75.

Goings, R. B. (2017a). Traditional and nontraditional high-achieving Black males' strategies for interacting with faculty at a historically Black college and university. J. Men's Stud. 25, 316–335. doi: 10.1177/1060826517693388

Goings, R. B. (2017b). Nontraditional Black male undergraduates: a call to action. Adult Learn. 28, 121–124. doi: 10.1177/1045159515595045

Goings, R. B. (2018). “Making up for lost time”: the transition experiences of nontraditional Black male undergraduates. Adult Learn. 29, 158–169. doi: 10.1177/1045159518783200

Goings, R. B. (2021). Introducing the Black male adult learner success theory. Adult Educ. Quart. 71, 128–147. doi: 10.1177/0741713620959603

Goings, R. B., Bristol, T. J., and Walker, L. J. (2018). Exploring the transition experiences of one Black male refugee pre-service teacher at a HBCU. J. Multicult. Educ. 12, 126–143. doi: 10.1108/JME-01-2017-0004

Goings, R. B., and Hunt, M. (2023). Black male adult learners in higher education: examining their connection to spirituality and its role in their academic success. J. Negro Educ. 92, 241–256.

Gulley, N. Y. (2021). Challenging assumptions: ‘Contemporary students,' ‘nontraditional students,' ‘adult learners,' ‘post-traditional,' ‘new traditional'. Schole J. Leis. Stud. Recreat. Educ. 36, 4–10. doi: 10.1080/1937156X.2020.1760747

Harper, S. R. (2010). An anti-deficit achievement framework for research on students of color in STEM. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2010, 63–74. doi: 10.1002/ir.362

Harper, S. R. (2012). Black Male Student Success in Higher Education: A Report From the National Black Male College Achievement Study. University of Pennsylvania; Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education.

Horn, L. J., and Carroll, C. D. (1996). Nontraditional undergraduates: trends in enrollment from 1986 to 1992 and persistence and attainment among 1989-90 beginning postsecondary students (Postsecondary Education Descriptive Analysis Reports; Statistical Analysis Report; No. NCES-97-578). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Jackson, C. III. (2021). Studying folks like us: the educational experiences of Black male nontraditional students within a predominantly White institution [Doctoral Dissertation]. Michigan State University ProQuest Dissertations, East Lansing, MI, United States.

Kenner, C., and Weinerman, J. (2011). Adult learning theory: applications to non-traditional college students. J. Coll. Read. Learn. 41, 87–96. doi: 10.1080/10790195.2011.10850344

National Center for Educational Statistics (2016). Digest of Education Statistics. Available online at: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_326.10.asp (Accessed May 15, 2025).

Palmer, R. T., Wood, J. L., and Arroyo, A. (2016). Toward a model of retention and persistence for Black men at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). Spectrum J. Black Men 4, 5–20. doi: 10.2979/spectrum.4.1.02

Rosser-Mims, D., Palmer, G. A., and Harroff, P. (2014a). “The reentry adult college student: an exploration of the Black male experience,” in Swimming Upstream: Black Males in Adult Education (New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, eds. D. Rosser-Mims, J. Schwartz, B. Drayton, and T. C. Guy, Vol. 144 (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 59–68). doi: 10.1002/ace.20114

Rosser-Mims, D., Schwartz, J., Drayton, B., and Guy, T. C., (eds.). (2014b). “Swimming upstream: black males in adult education [Special issue],” in New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education.

Spradley, P. (2001). Strategies for educating the adult Black male in college. Available from ERIC database. (EDO-HE-2001-02)

Strayhorn, T. L. (2015). Reframing academic advising for student success: from advisor to cultural navigator. NACADA J. 35, 56–63.doi: 10.12930/NACADA-14-199

Tatos, T., and Singer, H. (2021). Antitrust anachronism: the interracial wealth transfer in collegiate athletics under the consumer welfare standard. Antitrust Bull. 66, 396–430. doi: 10.1177/0003603X211029

Valencia, R. R. (1997). “Conceptualizing the notion of deficit thinking,” in The Evolution of Deficit Thinking: Educational Thought and Practice, ed. R. Valencia (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–12.

Whiting, G. W. (2006a). Enhancing culturally diverse males' scholar identity: suggestions for educators of gifted students. Gift. Child Today 29, 46–50. doi: 10.4219/gct-2006-2

Whiting, G. W. (2006b). From at risk to at promise: developing scholar identities among Black males. J. Second. Gift. Educ. 4, 222–229. doi: 10.4219/jsge-2006-407

Whiting, G. W. (2009a). The scholar identity institute: guiding Darnel and other Black males. Gift. Child Today, 32, 53–56, 63. doi: 10.1177/107621750903200413

Whiting, G. W. (2009b). Gifted Black males: understanding and decreasing barriers to achievement and identity. Roeper Rev. 31, 224–233. doi: 10.1080/02783190903177598

Whiting, G. W. (2014). “The scholar identity model: Black male success in the K-12 context,” in Building on Resilience: Models and Frameworks of Black male Success across the P-20 Pipeline, ed. F. A. Bonner (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing), 88–108).

Keywords: Black male achievement, Black Male Adult Learner Success Theory, adult learning, higher education, Black student success

Citation: Goings RB (2025) The Black Male Adult Learner Success Theory: unpacking institutional structures that support academic success. Front. Educ. 10:1637708. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1637708

Received: 29 May 2025; Accepted: 23 June 2025;

Published: 16 July 2025.

Edited by:

Patricia Marisol Virella, Montclair State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Christopher Sewell, Talladega College, United StatesLarry Walker, University of Central Florida, United States

Copyright © 2025 Goings. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ramon Bailey Goings, cmdvaW5nc0B1bWJjLmVkdQ==

Ramon Bailey Goings

Ramon Bailey Goings