- School of Education, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, United States

Equity-centered improvement is—necessarily—deeply relational, political, and adaptive. Improvers must regularly navigate uncertainty, negotiate conflicting priorities, and make situated decisions amidst organizational, political, and interpersonal constraints. However, too often, research and guidance focus on naming what improvers should do, with less attention to how improvers actually engage in the ongoing, improvisational, judgment-filled work of practicing improvement for equity. This conceptual article introduces design tensions as a conceptual tool for naming and navigating ongoing tradeoffs that arise in equity-centered change efforts. Drawing on existing research, we describe three design tensions: (1) reconciling needs for timeliness, learning, and collaboration, (2) negotiating between clarity for action and systemic complexity, and (3) mediating political dynamics and systemic disruption. We propose that practicing equity-centered improvement involves ongoing satisficing within these tensions and examine the potential power of bringing the lens of these tensions into the practice of, learning about, and study of equity-centered improvement.

Introduction

A growing body of scholarship affirms that equity-centered improvement is a deeply relational, political, and adaptive set of activities (Biag and Sherer, 2021; Gates et al., 2024; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021; Stosich, 2024; Zumpe, 2024). Improvers—an umbrella term we will use to include the wide range of educational leaders that might engage in equity-centered improvement—must regularly navigate uncertainty, negotiate conflicting priorities, and make situated decisions amidst organizational, political, and interpersonal constraints. However, too often, research and guidance for educational leaders in general—and specific to improvement—focus on naming what improvers should do, with less attention to how improvers actually engage in the ongoing, improvisational, judgment-filled work of transforming school systems and practices (Kazemi et al., 2022). Understanding the muddling through (Honig and Hatch, 2004) of educational leadership practice in more complex ways is an urgent necessity for ongoing efforts to improve schools and schooling.

This necessity takes on a particular urgency in the context of increasing efforts to bring together the tools and processes of continuous improvement (CI) with goals of disrupting inequity in school systems and practices. While all efforts to improve school systems and practices are complex, equity-centered efforts entail additional challenges. Here, we define equity-centered efforts as those that aim to confront, disrupt, and reimagine the practices, policies, systems, and relationships that shape student, family, and educator experiences and learning. Such efforts require a consistent, significant disruption of normative ways of knowing, thinking, and interacting for individuals, groups, and organizations (Lumby, 2012; Rodela and Rodriguez-Mojica, 2020; Theoharis, 2007; Welton et al., 2018). In practice, CI approaches are no different than any other educational change approach in that they can result in minor adjustments that are inconsistent with the transformative change required to disrupt entrenched inequities (Safir and Dugan, 2021). Because any effort for educational change operates within systems that inherently reproduce racism, inequity, and injustice, there is real risk that improvement tools and processes could make “racist educational systems more efficient” (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023, p. 106). Thus, we argue that it is imperative to understand the complexity of how processes and tools of improvement are designed and used in complex, political, and racialized educational contexts. We need powerful lenses to see the real-life complexity and muddling through of leaders trying to enact and adapt CI tools and processes within the specific challenges of equity-centered change.

To this end, this paper centers equity-centered improvement practice as its central concern: the dynamic, situated, ongoing, and improvisational work through which improvers engage with—and adapt—CI processes and tools in the pursuit of equity. We argue for closer attention to the lived aspects of improvers' decision making, foregrounding how improvers design, adapt, and use CI tools and processes amidst conflicting goals, constrained authority, and shifting contexts. We consider the potential of the design tensions framework (Tatar, 2007) as a conceptual tool for naming and navigating recurring tradeoffs that arise in equity-centered CI work. Design tensions offer a lens for improvers, those that support learning of improvement practice, and those who study improvement practice to recognize and reflect on the messy, value-laden decisions that define improvement practice in real-time, equity-centered systems change. Foregrounding these tensions can help surface the value-laden decisions that shape the context-specific work of improvement and support more intentional, principled, and adaptive understanding of, practicing of, and learning about equity-centered improvement.

Centering the everyday practice of improvers in equity-centered change

As CI has gained traction in education over the last decade, early literature emphasized identifying the tools, frameworks, and routines that underpin this work, such as logic models, driver diagrams, theories of change, fishbone diagrams, and plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles (Bryk et al., 2015; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020). These approaches, tools, and processes are often held up as useful for achieving equity in education due to their potential to support equity-centered educational transformation through (1) local, systems-level thinking, (2) collaboration between often siloed communities, with uneven power dynamics, and (3) iterative design, experimentation, and learning. However, one critique of this foundational phase is that improvement work can be overly focused on the technical solutions and overlook how power, race, identity, and context shape systems' problems and their solutions (e.g., Bocala and Yurkofsky, 2024; Jabbar and Childs, 2022).

In response, a growing body of equity-focused scholarship has pushed the field to rethink the assumptions and structures of CI strategies. These scholars argue that equity-centered improvement requires grappling with the lived realities of educational systems shaped by histories of oppression. Frameworks from Bocala and Yurkofsky (2024), Hinnant-Crawford et al. (2023), Jabbar and Childs (2022), Sandoval and Neri (2024), Diamond and Gomez (2023), and others emphasize the need for CI tools and routines to surface both structural and relational dimensions of inequity, elevate marginalized voices, and design systems grounded in dignity and agency. These contributions advance a powerful vision, naming the theories, values, goals, and roles that should guide improvement if it is to be “equity-centered.” Recent work also identifies practices or strategies that improvers might use to bring this vision into action, such as engaging community members in co-design or applying asset-based analyses (e.g., Cohen-Vogel et al., 2022; Sandoval and Neri, 2024; Valdez et al., 2020).

Yet presenting a theory or vision or recommending practices is different from understanding the actual practicing of equity-centered improvement. The latter focuses on the moment-to-moment, relational, adaptive, and improvisational decision-making that improvers engage in as they attempt to adapt or enact improvement strategies as they interact with others in their specific contexts. Drawing on Cook and Brown's (1999) definition of practice as “the coordinated activities of individuals and groups doing their ‘real work' as it is informed by particular organizational or group context” (pp. 386–387), we argue that that designing and using improvement tools and processes involves far more than executing predefined steps or producing a polished product. Instead, teams actively reshape and use tools and processes in ways that reflect their specific goals, constraints, values, and evolving conditions. CI approaches emphasize engaging with systems tools for inquiry into “what works, for whom, and under what conditions” (Bryk et al., 2015); the lens of practice deepens our understanding of how teams grapple with this question through ongoing sensemaking, improvisation, and responsive adaptation of improvement tools and processes to particular goals for equity and social, historical, and institutional contexts.

Like teaching or school leadership practice, the practice of improvement is a relational practice in that it involves moment-to-moment decision-making and participation in response to other, unpredictable humans in unique social and institutional contexts (Grossman et al., 2009). Relational practice involves improvisation and adaptation to particular people, moments, and contexts. A teacher's action, whether it be a question they ask or a lesson activity they design, is only effective in how they enact it in relation to particular students, at a particular moment. The same question or activity could be very ineffective—and in some cases, even harmful—if used in a slightly different way, by a different teacher, with a different group of students, or at a different moment in time. As Lampert (1985) observed of teaching, “as the teacher considers alternative solutions to any particular problem, she cannot hope to arrive at the ‘right' alternative… This is because she brings many contradictory aims to each instance of her work” (p. 181). Similarly in equity-centered CI practice, improvers navigate irreconcilable tensions between urgency and relationship-building, between clarity and complexity, between political constraints and transformational aspirations (Stosich, 2024; Gates et al., 2024; Iriti et al, 2024). The same plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle or logic model may yield learning in one setting and resistance in another, depending not only on technical fidelity, but also on how it is designed and enacted, by whom, with whom, and in what context (Bush-Mecenas, 2022).

We build on the work of others to argue that practicing improvement for equity-centered change is an ongoing process of negotiation, sensemaking, and adaptation through tensions (Kezar, 2013; Lüscher and Lewis, 2008). For instance, Sandoval and Van Es (2021) show how an aim statement was not merely completed, but collaboratively constructed through dialogue across stakeholders with diverging goals, identities, and interpretations. Similarly, Sandoval et al. (2024) highlight how designing a data display involved complex decisions about representation, inclusion, and storytelling, negotiations that enacted, and at times challenged, existing power dynamics. To center the practicing of improvement is to make visible the situated decisions that improvers must make as they use improvement tools and processes in particular contexts. To support this complex and often contested work—shaped by competing demands, shifting power dynamics, and the need for judgment and care—conceptual tools must legitimize these challenges and equip practitioners to navigate them with clarity and intentionality.

Tensions in practicing equity-centered improvement

Centering the practicing of improvement can take multiple forms. Here, we focus on a conceptual lens that highlights how practice is situated within inherent tensions. These tensions are not obstacles or “barriers” to be overcome; rather, engaging with these tensions is the work of practicing improvement in equity-centered change. Reports of continuous improvement design and activity increasingly recognize the significance of such tensions, highlighting the need to navigate them (Ahn et al., 2019; Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Cannata and Nguyen, 2020; Sandoval and Neri, 2024; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021; Zumpe et al., 2024), grapple with persistent dilemmas (Neumerski and Yurkofsky, 2024; Valdez et al., 2020), or determine steps forward amidst a range of possible interpretations and paths (Park et al., 2023).

To support understanding of practice within tensions, we bring forward the design tensions framework, originally introduced by Tatar (2007). The design tensions framework conceptualizes design practice as inherently situated within competing goals that are inevitable, consequential, and irreconcilable. Drawing on participatory and value-sensitive design traditions, Tatar frames design tensions as situations in which decisions must be made in relation to goals that pull in divergent directions, whether as dichotomies, continuums, or the interaction of incommensurate forces (p. 446). While initially applied to the design of learning technologies, the framework has since been used to analyze decisions made in diverse forms of collaborative design, including design of student assessments (Penuel et al., 2014), teacher professional development (Johnson et al., 2016), leadership learning tools (Resnick and Kazemi, 2019), and learning analytics dashboards (Ahn et al., 2019).

The lens of design tensions offers a valuable way to see, understand, and engage in equity-centered improvement by situating practice within the inherent uncertainties and political and interpersonal complexities of the work. Equity-centered systems change work represents a type of “wicked problem,” one that is complex, consequential, and with multiple, and potentially conflicting, goals (Buchanan, 1992; Rittel and Webber, 1973). Engaging with such problems requires leaders to weigh diverse perspectives and proposals (Asen, 2015), navigating values, logistical constraints, policies, and other factors that influence decision making (Huguet et al., 2021). Grappling with wicked problems involves ongoing experimentation, making sense of “failure,” in the face of the reality that the problem will never be completely “solved” (Conklin, 2006). Rather than seeking a single “right way” to develop and use improvement tools, improvers must “satisfice,” to develop designs for improvement that are “good enough” given the constraints and realities at hand (Simon, 1956). A design tension lens foregrounds how improvers navigate these recurring challenges and supports engagement, learning, and inquiry that embraces and amplifies the uncertainty and complexity of the work (Ishimaru and Bang, 2022).

Two important conceptual features of design tensions are crucial to note. First, within any equity-centered change effort, design tensions do not arise from individual preferences, but instead stem from broader institutional, social, political, and historical contexts (Seeber et al., 2024). Second, tensions are not resolved through a single act of “satisficing” and then set aside. In the work of equity-centered improvement, tensions are always present and decisions about how to “satisfice” will evolve over time. In this way, tensions are not discrete problems to be solved, but rather define the problem space in which improvers are constantly muddling through as they craft their improvement practice in relation to contexts over time (similar to how Honig and Hatch, 2004 and Park et al., 2023 conceptualize the practice of crafting coherence in education systems).

Recent research underscores why navigating these tensions matters. In their study of 35 school improvement networks, Duff et al. (2025) documented wide variation in how leaders designed and used CI tools to advance equity. Some leaders focused on coherence and alignment with existing district priorities, choosing tools that enabled clarity and immediate action. Others, however, prioritized reflection and disruption, designing tools that made space to interrogate identity, power, and systemic inequities, moves that were often slower and politically complex, but with potentially greater transformative potential. This variation was, in part, a result of how leaders navigated tensions in real time, charting unique paths between feasibility and disruption, urgency and relationship-building, alignment and resistance. Thus, how tensions are perceived, named, and engaged with in practice directly influences the trajectory of improvement work and the kinds of equity outcomes improvers are able—or unable—to produce.

There are a wide range of design tensions improvers may encounter as they engage in equity-centered improvement. As a starting point, we offer three initial design tensions, chosen for their illustrative power and for their likely pervasiveness across equity-centered improvement contexts.

1. Reconciling Needs for Timeliness, Learning, and Collaboration

2. Negotiating between Clarity for Action and Systemic Complexity

3. Mediating Political Dynamics and Systemic Disruption

Building on Tatar's (2007) conceptualization, each tension reflects a set of competing goals that teams must negotiate, goals that are often equally important but inherently in tension. These tensions are not isolated or sequential; they are crosscutting and deeply intertwined, shaping and reshaping one another as teams work through the complexity of equity-driven systems change. By naming and examining these tensions, we aim to provide a conceptual tool that can support efforts to engage in and study equity-centered improvement practice in ways that recognize the complex, context-specific sensemaking required to meaningfully transform educational systems toward equity. We note that all three tensions are likely useful lenses for understanding any CI effort in education. However, we argue that they are a particularly powerful and necessary lens for equity-centered CI, given the “wicked,” systemic complexities to any effort aimed at disrupting inequity and injustice.

Tension 1: reconciling needs for timeliness, learning, and collaboration

One central design tension in equity-centered improvement practice lies in reconciling two competing goals: (a) using improvement tools to drive urgent change to inequitable educational systems that are currently harming students, educators, and communities and/or (b) engaging with these tools in ways that support deep learning, shared understanding, and meaningful collaboration across groups.

The first goal involves using an improvement tool or process to support timely, actionable insights about systems and change efforts they can inform upcoming practice and policy decisions. Many school systems face acute challenges: racial disparities in discipline, inequitable access to resources, or disproportionate learning losses, to name a few. In these contexts, district and school leaders may turn to tools like logic models, driver diagrams, or PDSA cycles to rapidly generate insights and guide time-sensitive decisions. Improvers do not have endless time to unpack and redesign their systems: children are in classrooms now, a decision about teacher professional learning needs to be made tomorrow, the plan for principal evaluation needs to be developed by September. Improvers are also under pressure to demonstrate visible progress quickly, whether to meet compliance deadlines, respond to community demands, or secure funding and political support (Trujillo, 2013). Improvement tools and processes have the potential to generate swift insights, and support immediate decision-making. These tools can play a critical role in helping teams act in the face of uncertainty and complexity, especially when organizational memory is short and leadership transitions are frequent (Caduff et al., 2023).

However, the goal of using improvement tools and processes for urgent action is inherently in competition with a second goal of learning, developing new insights, and broadening the voices actively participating in improvement processes. Research on how educational leaders engage in design and implementation of change efforts indicates the tendency to resort to existing understandings of how systems work and familiar strategies for change (e.g., Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019). Disrupting this tendency and using improvement tools and processes to see—and design for change in—systems in fundamentally new ways requires significant learning, which takes time, trust, and meaningful collaboration with voices that are often excluded from improvement processes—including students, families, community members, and frontline educators. Research on other collaborative efforts in educational change, including Research-Practice Partnerships and Community Based Participatory Research emphasize the immense challenge of bringing together different voices in ways that authentically disrupts traditional hierarchies (e.g., Tanksley and Estrada, 2022). As Eddy-Spicer and Gomez (2022) write, “the mere performance of collaboration as an aspect of a routine does not guarantee that collaboration will necessarily be generative for equitable ends or, for that matter, equity in process” (p. 95). Similarly, Tuck (2009) warned of “damage-centered” approaches that involve participation of marginalized voices only to perpetuate deficit views by centering the damage inflicted on those participants. Authentically involving new and historically marginalized voices requires trust-building, collaborative inquiry, and a genuine shift in whose knowledge and stories shape improvement work—all of which can take time.

Herein lies the competing goals of Tension 1. When improvement teams lean too heavily toward urgency, tools may be reduced to compliance exercises or quick fixes that will fail to disrupt the underlying systems producing inequity. Conversely, focusing solely on robust learning and inclusive collaboration can slow momentum or delay needed interventions. This tension is a reality in which any CI effort unfolds (e.g., Zumpe, 2024). However, the specific kinds of learning and disruption of typical power dynamics inherent to equity-centered efforts, make this tension particularly salient. The learning involved in relation to understanding how systems of racism and oppression interact with leaders' own identities and animate school systems and practices is uniquely complex and contested (e.g., Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021; Zumpe et al., 2024). Likewise, the forms of collaboration necessary to legitimately involve historically marginalized voices is uniquely challenging, requiring collaboration across historical traumas, racialized practices, and hierarchical structures. For equity-centered efforts to avoid merely tweaking, or even reproducing inequitable systems and practices these complex forms of learning and collaboration are essential. However, if improvers wait to take action until such learning or collaborative relationships are developed, action toward the urgency of injustice is unlikely to unfold.

Tension 2: negotiating between clarity for action and systemic complexity

A second design tension arises from the competing goals in improvement practice: (a) generating concrete, actionable insights through the use of CI tools, and (b) using those same tools to surface the full complexity and uncertainty of the systems producing inequity.

On one hand, improvement tools and processes are often valued for their ability to simplify complexity just enough to make change possible. Teams use tools like logic models, driver diagrams, or process maps to analyze how existing system dynamics lead to current outcomes and to identify points of intervention. These representations need to be accessible, interpretable, and useful for supporting action within a limited time frame. To be actionable, tools typically must reach a point of being “complete enough,” even if that means relying on assumptions, simplified causal pathways, or bounded scopes of control. For example, logic models are designed to illustrate a program's theory of action under ideal conditions, allowing practitioners to map inputs to outcomes in clear, linear ways (W. K. Kellogg Foundation., 2004). Identifying actionable next steps often hinges on this clarity.

At the same time, equity-centered improvement also aims for another important goal: to use tools to reveal the deep, interlocking systems of power and oppression that underlie and reproduce injustice. Bocala and Yurkofsky (2024) argue that “seeing the system” must include both visible structures (i.e., policies, routines, resource flows) and invisible forces such as identity, relationships, and racialized assumptions. A genuinely equity-focused improvement effort needs to interrogate not just organizational processes but the historical, political, and cultural systems that shape them, including exploring how race, class, gender, language, and ability intersect to produce exclusion and marginalization within schools and broader institutional and community contexts. Such dynamics are deeply complex, subtle, and evasive given their ongoing normalization within policy and practice (Kohli et al., 2017).

Thus, there is a tension between clarity for action and systemic complexity. If improvers prioritize developing and using improvement tools in ways that are concise, clear, and actionable, they may oversimplify the system and obscure the very dynamics that equity work aims to expose. Conversely, striving to fully represent the system's complexity and uncertainty risks becoming overwhelming or paralyzing—too diffuse to guide actionable decision-making, particularly for teams constrained by time, resources, or political pressure. Again, this tension is likely present in any CI effort. However, given the deeply historical and systemic nature of inequity in education, the tension is especially critical in equity-centered efforts. In some cases of CI, “seeing the system” can largely be contained within the school or district walls. However, equity-centered change necessitates understanding of an educational system within many, intersecting layers of social, political, and historical context. For equity-centered improvement efforts to avoid merely reproducing inequitable systems and practice, they cannot be neutral to the systems of oppression that schools exist within, including (but not limited to) racism, patriarchy, colonialism, capitalism, and heteronormativity (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Jabbar and Childs, 2022). Any equity-centered improvement team must intentionally grapple with the challenge of defining clear action steps without oversimplifying or neutralizing this immense complexity.

Tension 3: mediating political dynamics with systemic disruption

A third design tension in equity-centered improvement work lies between the competing goals of (a) using improvement tools in ways that are politically feasible or acceptable within current systems and (b) leveraging these tools to disrupt current political systems and practices that create and perpetuate inequity.

On one hand, improvement tools must be able to be legitimate enough within complex systems as political arenas—accessible, legible, and acceptable to those in power, including district leaders, school boards, funders, and other institutional actors. If tools are too provocative, complex, or unfamiliar, they risk being dismissed, ignored, or misunderstood, and the improvement effort can stall before it begins.

At the same time, the very purpose of equity-centered improvement is to disrupt the status quo—to challenge the deeply entrenched systems, norms, and power structures that sustain racial, economic, and other forms of educational injustice. Scholars of anti-racist leadership and systemic change argue that meaningful progress often requires discomfort, conflict, and disruption (Virella and Liera, 2024). Yet, educational institutions frequently operate under a culture of civility, consensus, and “niceness” that resists the confrontation of inequity in order to preserve professional and political comfort.

Thus, equity-centered improvement practice unfolds within a tension between political dynamics and systemic disruption. Jeannie Oakes's concept of the zone of mediation is useful here. In her study of tracking and inequality, Oakes (1985) argued that educational systems operate within a bounded space of what kinds of change are seen as legitimate, acceptable, or politically possible. This zone of mediation, shaped by local beliefs, power dynamics, and institutional politics, constrains which reforms, tools, or policies are taken seriously and which are rejected or watered down. Applied to improvement practice, improvers must often navigate the limits of what is acceptable within a given context. If design decisions push too far outside this zone, it may never be used or may provoke backlash, but if improvement work remains too far inside the zone, it risks reinforcing the status quo. A theory of change, for instance, might center safe, incremental goals that avoid naming systemic racism or power dynamics—thus bypassing the deeper work of transformation (Gates et al., 2024). On the other hand, tools and processes that are designed to surface systemic injustice head-on may provoke resistance or disengagement from key actors, limiting their use in the very systems they aim to change. Navigating this tension requires strategic design choices: finding ways to invite constituencies into engaging with continuous improvement tools and into difficult conversations while preserving their willingness to stay at the table.

Again, this tension is likely present in any CI effort. However, while all educational change involves navigating political power structures within educational and community systems and hierarchies (Hopkins et al., 2022), equity-centered change efforts confront politics in particularly “charged” ways. In some contexts, equity-centered change efforts are largely performative and compliance-driven. And, in this moment in U.S. history, the very use of the word “equity” comes with significant risks to improvers' efforts (e.g., LoBue and Douglass, 2023), including cuts to crucial funding. Furthermore, leaders of equity initiatives are, themselves, situated within complex, racialized and gendered political environments, with varied access to the power or authority necessary for significant change (Ahn et al., 2024; Irby et al., 2022). Ignoring the reality of this tension oversimplifies the complexity of the practice of equity-centered improvement and renders any effort unlikely to create meaningful change.

The promise of design tensions as a lens for practicing equity-centered improvement

The design tensions explored above are just three of many that are likely present in all equity-centered improvement efforts. Below, we explore how these and other design tensions might be unpacked within multiple equity-centered contexts: as a conceptual tool for improvement practice, learning about improvement practice, and enriching research of improvement practice.

Engaging design tensions in improvement practice

First, the design tensions offer a practical and conceptual tool for supporting equity-centered improvement work, helping teams navigate the inherent complexity of using CI tools and processes in real-world educational settings. The lens of design tensions emphasizes that improvement tools and processes are not neutral or prescriptive instruments, but dynamic, context-sensitive design activities that require ongoing reflection, negotiation, and adaptation in response to the specific demands of improvement contexts.

Explicitly naming tensions has the potential to support improvers to surface and examine the often-competing goals embedded in their decision-making. The lens of design tensions invites teams to ask: What are we prioritizing? What are we compromising? What are we weighing when we are making these choices? What about our particular context or this particular moment in our work is influencing our choice right now? This reframing moves satisficing from an implicit coping mechanism to a conscious and principled design decision grounded in the particular values, constraints, and relational dynamics of the local context. For example, Takahashi et al. (2025) emphasize the complexity of turning measurement into a tool for equity, not just accountability. Explicitly naming the tensions of standardized simplicity vs. context-sensitive complexity might be a useful way in which to engage in intentional design and adaptation of practical measurement routines to reflect key values.

Design tensions might also be useful for structuring routines to support complex, adaptive decision making about how to meaningfully use improvement tools and processes within particular equity-centered change contexts (Ahn et al., 2019; Diamond and Gomez, 2023). Routines are repeated, patterned practices that organize how teams interact, make decisions, and use tools in their everyday work (Feldman and Pentland, 2003). For example, a team might open each weekly meeting by revisiting a guiding question tied to a specific design tension—such as: “Where are we trading off equity for efficiency this week?” or “Are we privileging institutional norms over community knowledge?” These kinds of routines may support improvers to notice the decisions they are making, rather than defaulting to a compliance-oriented use of CI tools.

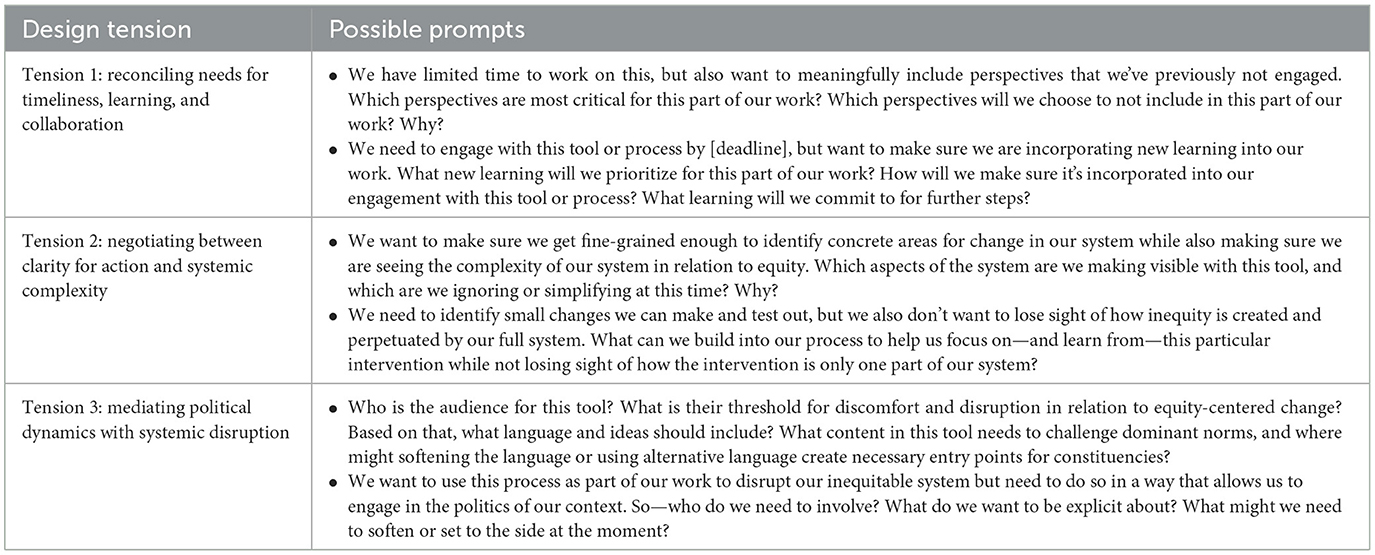

By explicitly naming and working within design tensions, teams can examine a wider range of possibilities and make conscious choices about how to reconcile competing demands. Table 1 offers practical questions related to the three initial design tensions described above that teams might build into recurring routines—such as reflection protocols, planning templates, or check-ins—that help them attend to key tensions in their work. Over time, these routines can help shift satisficing from doing “just enough” under pressure into a purposeful act of design, where teams learn to make trade-offs with intention, grounded in context, guided by values, and open to iteration.

Through intentional routines, the lens of design tensions can help teams build a shared language to engage in the difficult but necessary dialogue about trade-offs inherent in systems change. This framing validates the iterative, non-linear, and often messy nature of equity-centered improvement work, where decisions rarely follow a straightforward path (Asen, 2015). For example, Penuel et al. (2025) describe a state agency that created a driver diagram to guide efforts toward equity in science education. In doing so, they surfaced a challenging tension between maintaining local relevance to ensure the work was responsive to community contexts while also developing system-level infrastructure that could support coherence at scale. A design tensions lens could help such a team more explicitly name and explore these trade-offs, asking questions like: “What aspects of our work must remain flexible for local adaptation, and what needs to be standardized to ensure system-wide learning?” Embedding these kinds of reflective questions into regular routines—such as structured check-ins or collaborative planning protocols—has the potential to help teams shift away from compliance-driven practices and toward more responsive and intentional decision-making. Ultimately, this approach supports a mindset of “good enough for now,” enabling teams to move forward thoughtfully and pragmatically while still holding space for complexity and deeper learning.

Learning about design tensions in improvement practice

Learning continuous improvement can be oversimplified if opportunities for learning focus only on abstract theory but little application or center on lists of isolated knowledge or skills that fail to reflect the messiness of real-world improvement practice. Scholars of practice-based learning argue that meaningful professional learning—particularly for educators engaged in equity-centered improvement—must be grounded in the goals of practice (Gibbons et al., 2021; Janssen et al., 2015; Resnick and Kazemi, 2019). This perspective emphasizes supporting learners in navigating the multiple, often competing, demands they face as they work to enact those goals within specific contexts

Drawing on Resnick and Kazemi's (2019) work with a research-practice partnership (RPP) focused on school leader learning, we see a compelling model for how to think about supporting learning of improvement practice. In this project, principals were not trained to “deliver” a standardized set of leadership moves. Instead, they were introduced to a set of goals for their leadership practice (e.g., fostering risk-taking among teachers) and were supported to consider a range of ways their practice might contribute to those goals depending on their personality, identity, relationships, and school context.

We propose that design tensions offer a generative structure for helping leaders and educators learn how to think, how to choose, and how to adapt as they use CI tools within dynamic contexts. For example, one foundational tension that the framework might illuminate is how problems of practice are defined and scoped, especially in equity-focused CI work. As Zumpe et al. (2024) argue, identifying an equity-centered problem of practice involves wrestling with the tension between scope and specificity: the need to think broadly about systemic, structural inequities while also narrowing in on a concrete, actionable problem at the “right grain size” for disciplined inquiry. We agree with Zumpe and colleagues that educational opportunities can and should be designed to develop the learning required to navigate these kinds of tensions.

Leaders can be supported in identifying the tensions they face and in exploring multiple ways of satisficing those tensions, balancing competing goals in relation to particular contexts rather than attempting to resolve them completely. For instance, in relation to particular tools or processes, learners might engage in learning framed by questions such as:

• What are the tensions that can arise when we use [CI-related tool or process] for equity-centered improvement? How might they show up?

• What are different approaches to satisficing this tension when using [CI-related tool or process]? What are the affordances and constraints of different approaches to satisficing? Which approaches to satisficing will result in perpetuation of inequities in our system? What considerations might be important for deciding what approach to move forward with?

• How might approaches to satisficing this tension evolve over time as work toward equity progresses in a context? How would we know when to make a shift in our approach?

Additionally, design tensions might serve as reflective tools for guided analysis of cases, collaborative inquiry into examples from their own settings, and/or reflection with coaches or colleagues (e.g., Anderson and Davis, 2024). Learners might explore questions:

• What equity-related tensions arose when you used [CI-related tool or process]?

• How did you decide what to do within that tension? What were you prioritizing? What trade-offs did you make?

• How did your context—political, relational, institutional, broader environment—shape your decisions?

• Did your approaches to satisficing this tension shift over time? Why? How?

• If you could redesign your work with that tool or process, what might you do differently and why?

In this way, the design tensions framework could support deeper professional learning by legitimizing the uncertainty and judgment inherent in leading for equity and fostering a mindset oriented toward reflective, principled experimentation, what Bryk et al. (2015) call “learning to improve.” Design tensions might also serve as a tool for “critical praxis,” creating structure for both the reflection and action necessary for improvement to contribute to efforts for equity (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023). Such a shift moves learning toward discernment to make context-sensitive, values-driven decisions in their equity-centered improvement practice. As we argued above, these questions are likely useful in any effort for educational improvement, however we contend they are crucial for teams to grapple with in equity-centered efforts.

Studying design tensions in improvement practice

To better understand how educational systems change, research must take the practice of improvement seriously as a rich site of sensemaking, judgment, and negotiation. Yet, much of the existing literature on improvement tends to flatten this complexity or focus on technical execution and results. The concept of design tensions offers a lens for studying this complexity. By focusing on how educators, researchers, and system leaders recognize and respond to these tensions, researchers can access a deeper layer of understanding about the real work of equity-centered improvement (Sandoval et al., 2024; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021).

This lens opens new possibilities to support theory development about the conditions, judgments, and adaptations that animate equity work in continuous improvement (Eisenhardt, 1989). For example, Iriti et al (2024) describe how a Networked Improvement Community (NIC) adapted its tools and routines to critically address how white dominant culture can become embedded in improvement science. Their account provides insight into the specific form that equity-centered adaptation took in one context. Viewing this example through the lens of design tensions reveals additional opportunities for theory-building: how did the team balance the tension between urgency and time for learning as they engaged in critical reflection? How did they sequence and sustain this process given political and relational constraints? Similarly, through the lens of political dynamics and systemic disruption, we might ask what organizational cues signaled that the team—within their broader context—was ready to confront entrenched systems of racism and white supremacy? Studying design tensions in this way helps illuminate how equity-centered improvement is enacted—not only what is done, but how and why decisions emerge over time.

Scholars developing case studies—such as those by Bush-Mecenas (2022), Gates et al. (2024), and Stosich (2024)—have surfaced how improvement teams “muddle through” the complex work of equity in highly variable environments. A design tensions lens complements this work by offering an analytic lens that could be operationalized to examine how trade-offs are made, what is prioritized, how teams learn and adapt over time, and these processes link to improvement goals.

Similarly, such an analytic focus has particular value in multi-case research, such as studies within improvement networks or comparative analyses across different teams (e.g., Duff et al., 2025; Eubanks et al., 2024). For instance, Ahn et al. (2019) describe how designing tools across multiple improvement sites required constant negotiation of generalizability and specificity. Rather than seeking a perfect fit for one context, the network embraced adaptive design as a dynamic process: “Rather than hyper-optimizing for a single situation, we are continually analyzing and balancing our design process across comparative cases… to develop solutions that hopefully can work for a wider range of scenarios” (p. 74). In this instance, design tensions could provide a lens through which to view and understand the variation in improvement practice in multiple contexts.

Conclusion

CI tools and processes have the potential to disrupt typical, piece-meal approaches to educational improvement—a necessity for equity-centered change. These tools and processes can support equity-centered improvers to see, design (and re-design) for transformation of the complex systems that create and perpetuate inequities. However, such potentials are not guaranteed.

To fulfill their potential in equity-centered work, CI tools and processes must be adaptable, flexible, and sensitive to the different contexts in which they are engaged. Improvement teams must adapt and customize these tools in ways that align with their goals of equity, local needs, and particular social, historical, and institutional contexts (Bush-Mecenas, 2022; Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Jabbar and Childs, 2022). Yet, there remains a lack of clear theorization of—or support for—these critical, messy processes of design and adaptation. While CI approaches emphasize engaging with systems tools for inquiry into “what works, for whom, and under what conditions” (Bryk et al., 2015), there is limited understanding of how improvers muddle through the use of equity-centered improvement tools in ways that that will work for them, in their conditions, especially as they do so within complex, political relationships and contexts that can constrain or support such efforts (Gates et al., 2024; Stosich, 2024). There is a need for powerful conceptual tools that can illuminate meaningful insights into—and support effective enactment of—localized, equity-centered improvement practice. Without critical attention to the actual practicing of improvement in equity-centered change, CI approaches are not different than any other approach to educational change—they are very likely to generate only incremental change or, in fact, reproduce the very inequities they purport to address (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Jabbar and Childs, 2022; Safir and Dugan, 2021).

In this article, we propose that design tensions provide a lens for seeing, valuing, and supporting the complexity of any improvement practice, but in particular, of equity-centered improvement practice. The tensions we identify in this article—(1) reconciling needs for timeliness, learning, and collaboration, (2) negotiating between clarity for action and systemic complexity, and (3) mediating political dynamics and systemic disruption—are likely always present for educational leaders, but are intensified in efforts that aim to disrupt inequity in educational systems and practices. Within equity-centered efforts, goals for speed, learning, inclusion, usability, disruption, and transformation are more urgent, more challenging, more embedded in systems outside of any improvers' control, and more politically perilous.

Within well-intentioned efforts to provide tools and processes for equity-centered improvement, there is a significant risk of simplifying the immense, messy challenge of actually using such tools and processes in complex educational contexts. We argue that the lens of design tensions has the potential to legitimize and honor the impossible complexity that equity-centered improvers must grapple with on a day-to-day basis. As with any relational practice—where individuals are making decisions and improvising within unpredictable and complicated social contexts—improvers engage in ongoing negotiation, interpretation, sensemaking, and satisficing (Grossman et al., 2009). There are no “right ways,” only “next best steps given our current situation.” Rather than simplify the practice of equity-centered improvement, design tensions hold a magnifying glass to the irreconcilable goals that improvers must craft a pathway between. And it is the small decisions that shape this pathway that need to be seen, understood, valued, and supported for CI tools and processes to have any potential to be useful in the ongoing, challenging quest toward equity in our schools.

Author contributions

AR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. CF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. JB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This publication is based on research commissioned and funded by The Wallace Foundation as part of its mission to support and share effective ideas and practices.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahn, J., Campos, F., Hays, M., and DiGiacomo, D. (2019). Designing in context: reaching beyond usability in learning analytics dashboard design. J. Learn. Analytics 6, 70–85. doi: 10.18608/jla.2019.62.5

Ahn, J., Gomez, K., Lee, U. S., and Wegemer, C. M. (2024). Embedding racialized selves into the creation of research-practice partnerships. Peabody J. Educ. 99, 295–313. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2024.2357031

Anderson, E., and Davis, S. (2024). Coaching for equity-oriented continuous improvement: facilitating change. J. Educ. Change 25, 341–368. doi: 10.1007/s10833-023-09494-6

Asen, R. (2015). Democracy, Deliberation, and Education. University Park, PA: Penn State Press. doi: 10.1515/9780271073163

Biag, M., and Sherer, D. (2021). Getting better at getting better: improvement dispositions in education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 123, 1–42. doi: 10.1177/016146812112300402

Bocala, C., and Yurkofsky, M. (2024). Continuous improvement and the ‘wicked'problems of racial inequity. J. Educ. Change 26, 1–28. doi: 10.1007/s10833-024-09520-1

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., and LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to Improve: How America's Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bush-Mecenas, S. (2022). “The business of teaching and learning”: institutionalizing equity in educational organizations through continuous improvement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 59, 461–499. doi: 10.3102/00028312221074404

Caduff, A., Daly, A. J., Finnigan, K. S., and Leal, C. C. (2023). The churning of organizational learning: a case study of district and school leaders using social network analysis. J. Sch. Leadersh. 33, 355–381. doi: 10.1177/10526846221134006

Cannata, M., and Nguyen, T. D. (2020). Collaboration versus concreteness: tensions in designing for scale. Teach. Coll. Rec. 122, 1–34. doi: 10.1177/016146812012201207

Cohen-Vogel, L., Century, J., and Sherer, D. (2022). A Framework for Scaling for Equity. Stanford, CA: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Cook, S. D., and Brown, J. S. (1999). Bridging epistemologies: the generative dance between organizational knowledge and organizational knowing. Organ. Sci. 10, 381–400. doi: 10.1287/orsc.10.4.381

Diamond, J. B., and Gomez, L. M. (2023). Disrupting white supremacy and anti-black racism in educational organizations. Educ. Res. doi: 10.3102/0013189X231161054

Duff, M., Sherer, J. Z., Premo, A., and Perlman, H. (2025). Hub leaders' perspectives on equity in networked improvement. Peabody J. Educ. 100, 100–116. doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2025.2444845

Eddy-Spicer, D., and Gomez, L. M. (2022). “Accomplishing meaningful equity,” in The Foundational Handbook on Improvement Research in Education (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, Inc.), 89–110.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 14, 532–550. doi: 10.2307/258557

Eubanks, S., Neumerski, C. M., Callahan, P. C., Anthony, D., Snell, J., Blondonville, D., et al. (2024). Fostering improvement: a reflection on equity-centered improvement across three initiatives. Front. Educ. 9:1434362. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1434362

Feldman, M. S., and Pentland, B. T. (2003). Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Adm. Sci. Q. 48, 94–118. doi: 10.2307/3556620

Gates, E., Rohn, K. C., and Murugaiah, K. (2024). Equity-related ‘knots' in theory of change development: conceptualization and case illustrations. Eval. Program Plann. 103:102385. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2023.102385

Gibbons, L. K., Lewis, R. M., Nieman, H., and Resnick, A. F. (2021). Conceptualizing the work of facilitating practice-embedded teacher learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 101:103304. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103304

Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., and Williamson, P. W. (2009). Teaching practice: a cross-professional perspective. Teach. Coll. Rec. 111, 2055–2100. doi: 10.1177/016146810911100905

Hinnant-Crawford, B., Lett, E. L., and Cromartie, S. (2023). “Using critical race theory to guide continuous improvement,” in Continuous Improvement: A Leadership Process for School Improvement (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 105.

Hinnant-Crawford, B. N. (2020). Improvement Science in Education: A Primer. Gorham, ME: Myers Education Press.

Honig, M. I., and Hatch, T. C. (2004). Crafting coherence: how schools strategically manage multiple, external demands. Educ. Res. 33, 16–30. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033008016

Hopkins, M., Weddle, H., Riedy, R., Caduff, A., Matsukata, L., and Sweet, T. M. (2022). “Critical social network analysis as a method for examining how power mediates improvement efforts,” in The Foundational Handbook on Improvement Research in Education, 403–422.

Huguet, A., Coburn, C. E., Farrell, C. C., Kim, D. H., and Allen, A. R. (2021). Constraints, values, and information: how leaders in one district justify their positions during instructional decision making. Am. Educ. Res. J. 58, 710–747. doi: 10.3102/0002831221993824

Irby, D. J., Green, T., and Ishimaru, A. M. (2022). PK−12 district leadership for equity: an exploration of director role configurations and vulnerabilities. Am. J. Educ. 128, 417–453. doi: 10.1086/719120

Iriti, J., Delale-O'Connor, L., Sherer, J. Z., Stol, T., Davis, D., and Matthis, C. (2024), Adapting improvement science tools and routines to build racial equity in out-of-school time STEM spaces. Front. Educ. 9:1434813. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1434813.

Ishimaru, A. M., and Bang, M. (2022). “Solidarity-driven codesign,” in The Foundational Handbook on Improvement Research in Education, 383–402.

Ishimaru, A. M., and Galloway, M. K. (2021). Hearts and minds first: institutional logics in pursuit of educational equity. Educ. Adm. Q. 57, 470–502. doi: 10.1177/0013161X20947459

Jabbar, H., and Childs, J. (2022). “Critical perspectives on the contexts of improvement research in education,” in The Foundational Handbook on Improvement Research in Education (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing, Inc.), 241–261.

Janssen, F., Grossman, P., and Westbroek, H. (2015). Facilitating decomposition and recomposition in practice-based teacher education: the power of modularity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 51, 137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.06.009

Johnson, R., Severance, S., Penuel, W. R., and Leary, H. (2016). Teachers, tasks, and tensions: lessons from a research–practice partnership. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 19, 169–185. doi: 10.1007/s10857-015-9338-3

Kazemi, E., Resnick, A. F., and Gibbons, L. (2022). Principal leadership for school-wide transformation of elementary mathematics teaching: why the principal's conception of teacher learning matters. Am. Educ. Res. J. 59, 1051–1089. doi: 10.3102/00028312221130706

Kezar, A. (2013). Understanding sensemaking/sensegiving in transformational change processes from the bottom up. Higher Education 65, 761–780. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9575-7

Kohli, R., Pizarro, M., and Nevárez, A. (2017). The “new racism” of K−12 schools: centering critical research on racism. Rev. Res. Educ. 41, 182–202. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16686949

Lampert, M. (1985). How do teachers manage to teach? Perspectives on problems in practice. Harv. Educ. Rev. 55, 178–195. doi: 10.17763/haer.55.2.56142234616x4352

LoBue, A., and Douglass, S. (2023). When white parents aren't so nice: the politics of anti-CRT and anti-equity policy in post-pandemic America. Peabody J. Educ. 98, 548–561 doi: 10.1080/0161956X.2023.2261324

Lumby, J. (2012). Leading organizational culture: Issues of power and equity. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 40, 576–591. doi: 10.1177/1741143212451173

Lüscher, L. S., and Lewis, M. W. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: working through paradox. Acad. Manag. J. 51, 221–240. doi: 10.5465/amj.2008.31767217

Mintrop, R., and Zumpe, E. (2019). Solving real-life problems of practice and education leaders' school improvement mind-set. Am. J. Educ. 125, 295–344 doi: 10.1086/702733

Neumerski, C. M., and Yurkofsky, M. M. (2024). Dilemmas in district–university partnerships: examining network improvement communities as levers for systems change. J. Educ. Adm. 62, 702–715. doi: 10.1108/JEA-10-2023-0261

Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Park, V., Kennedy, K. E., Gallagher, H. A., Cottingham, B. W., and Gong, A. (2023). Weaving and stacking: how school districts craft coherence towards continuous improvement. J. Educ. Change 24, 919–942. doi: 10.1007/s10833-022-09471-5

Penuel, W. R., Confrey, J., Maloney, A., and Rupp, A. A. (2014). Design decisions in developing learning trajectories–based assessments in mathematics: a case study. J. Learn. Sci. 23, 47–95. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2013.866118

Penuel, W. R., Neill, T. R., and Campbell, T. (2025). Supporting a state in developing a working theory of improvement for promoting equity in science education. Front. Educ. 10:1431793. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1431793

Resnick, A. F., and Kazemi, E. (2019). Decomposition of practice as an activity for research-practice partnerships. AERA Open 5:2332858419862273. doi: 10.1177/2332858419862273

Rittel, H. W., and Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 4, 155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730

Rodela, K. C., and Rodriguez-Mojica, C. (2020). Equity leadership informed by community cultural wealth: counterstories of Latinx school administrators. Educ. Adm. Q. 56, 289–320. doi: 10.1177/0013161X19847513

Safir, S., and Dugan, J. (2021). Street Data: A Next-Generation Model for Equity, Pedagogy, and School Transformation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Sandoval, C., Bohannon, A. X., and Michael, J. (2024). Examining power through practice in continuous improvement in education. Educ. Res. 53, 420–425. doi: 10.3102/0013189X241271359

Sandoval, C., and Neri, R. C. (2024). Toward a continuous improvement for justice. Front. Educ. 9:1442011. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1442011

Sandoval, C., and Van Es, E. A. (2021). Examining the practices of generating an aim statement in a teacher preparation networked improvement community. Teach. Coll. Rec. 123, 1–3. doi: 10.1177/016146812112300606

Seeber, E. R., Spillane, J. P., Yin, X., Haverly, C., and Quan, W. (2024). Leading systemwide improvement in elementary science education: managing dilemmas of education system building. Am. Educ. Res. J. 61, 1074–1112. doi: 10.3102/00028312241269165

Simon, H. A. (1956). Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychol. Rev. 63:129. doi: 10.1037/h0042769

Stosich, E. L. (2024). Working toward transformation: educational leaders' use of continuous improvement to advance equity. Front. Educ. 9:1430976. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1430976

Takahashi, S., Sandoval, C., Jackson, B., Cunningham, J., and Taylor, C. (2025). Practical measurement for equity and justice. Front. Educ. 9:1442505. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1442505

Tanksley, T., and Estrada, C. (2022). Toward a critical race RPP: how race, power and positionality inform research practice partnerships. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 45, 397–409. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2022.2097218

Tatar, D. (2007). The design tensions framework. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 22, 413–451. doi: 10.1080/07370020701638814

Theoharis, G. (2007). Social justice educational leaders and resistance: toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 43, 221–258. doi: 10.1177/0013161X06293717

Trujillo, T. M. (2013). The politics of district instructional policy formation: compromising equity and rigor. Educ. Policy 27, 531–559. doi: 10.1177/0895904812454000

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: a letter to communities. Harv. Educ. Rev. 79, 409–428. doi: 10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15

Valdez, A., Takahashi, S., Krausen, K., Bowman, A., and Gurrola, E. (2020). Getting Better at Getting More Equitable: Opportunities and Barriers for Using Continuous Improvement to Advance Educational Equity. San Francisco, CA: WestEd.

Virella, P., and Liera, R. (2024). Nice for what? The contradictions and tensions of an urban district's racial equity transformation. Educ. Sci. 14:420. doi: 10.3390/educsci14040420

Welton, A. D., Owens, D. R., and Zamani-Gallaher, E. M. (2018). Anti-racist change: a conceptual framework for educational institutions to take systemic action. Teach. Coll. Rec. 120, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/016146811812001402

W. K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004). Using Logic Models to Bring Together Planning, Evaluation, and Action: Logic Model Development Guide. Battle Creek, MI: WK Kellogg Foundation.

Zumpe, E. (2024). School improvement at the next level of work: the struggle for collective agency in a school facing adversity. J. Educ. Change 25, 485–529. doi: 10.1007/s10833-023-09500-x

Keywords: continuous improvement (CI), design tensions, improvement practice, educational equity, equity-centered improvement

Citation: Resnick AF, Farrell CC and Bristol J (2025) Practicing equity-centered improvement: a design tensions perspective. Front. Educ. 10:1638548. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1638548

Received: 30 May 2025; Accepted: 04 September 2025;

Published: 25 September 2025.

Edited by:

Angel Yee-lam Li, Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Resnick, Farrell and Bristol. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alison Fox Resnick, YWxpc29uLnJlc25pY2tAY29sb3JhZG8uZWR1

Alison Fox Resnick

Alison Fox Resnick Caitlin C. Farrell

Caitlin C. Farrell Jackquelin Bristol

Jackquelin Bristol