- 1College of Education and Human Development, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, United States

- 2School of Foreign Languages, Guilin University of Electronic Technology, Guilin, China

The attention of researchers in the field of second language acquisition has been drawn to boredom, which was considered as one of the most prevalent and distressing emotions. However, studies delving into the teacher-related foreign language boredom are few. Recognizing the significant role of teachers in foreign language education, we aimed to identify the sources and factor structure of teacher-related boredom through a literature review. Drawing on a review of existing literature and control-value theory, five teacher-related factors are identified using both inductive and deductive approaches: teacher controlling teaching, teacher emotional support, teacher-student rapport, teacher feedback, and teacher burnout. A deeper understanding of teacher-related boredom in EFL classrooms can help researchers and educators in the field of second language acquisition gain valuable insights into its contributing factors, inform instructional practices, and improve learner engagement and outcomes.

Introduction

Many studies have been conducted on the nature of boredom in majors like psychology, education, and educational psychology (Mora, 2011; Tam et al., 2021; Van Tilburg and Igou, 2017). The number of recent studies dealing with boredom in EFL contexts is still low (Li et al., 2023) and studies on specific teacher-related boredom hardly existed until recent years. About teacher-related factors, researchers have not formed direct research focus but mentioned occasionally about it in their research as it is one of the factors they studied (i.e., Zhang, 2022; Li, 2022). Some explained teacher-related boredom in several main forms (Zhang, 2022). However, there was not any systematic study on teacher-related boredom in EFL classroom. Education professionals, especially teachers, should identify strategies to alleviate students’ boredom in academic settings. Specifically, there is a need for conducting research on boredom in teacher-related factors and how the factors fluctuate with different teaching modes and content. Given this gap, the present study attempts to examine the specific teacher-related factors to EFL student boredom from the existing literature and discuss future research focus.

Boredom

Learning a second or a foreign language can involve both positive and negative feelings. While positive emotions were consistently and strongly correlated with motivation-related variables, correlations involving negative emotions were weaker and less consistently implicated in motivation (MacIntyre and Vincze, 2017). According to MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012), negative emotion produced the opposite tendency, a narrowing of focus and a restriction of the range of potential language input. Negative emotions could demotivate learners due to a sense of frustration and disappointment when learners failed to achieve their goals, losing confidence in their ability to succeed and discouraging them from investing further time and energy in language learning (Richards, 2022).

Boredom, as a negative emotion, has emerged as a significant factor affecting learners’ learning, yet it was underexplored. According to Smith (1981), boredom attracted only sporadic interest as a general concept until the end of the 1970s, and from studies conducted by psychologists, psychotherapists and psychiatrists in mainly work-related settings. Throughout the 1980s, however, things changed. Already described as an elusive and aversive emotional state (the experience of boredom by an individual in any given moment), it is highly situational yet varies across individuals and can arise quickly in low-stimulation contexts. O’Hanlon (1981) noted that boredom occurred as a reaction to task situations where the pattern of sensory stimulation was nearly constant or highly repetitive and monotonous; the degree of boredom reported by different individuals in the same working environment varied greatly; bored individuals may attempt to modify what they have to do or escape their working environment altogether; boredom could occur within minutes after starting something repetitive, particularly if frequently experienced in the past; boredom was highly situation-specific but also immediately reversible.

Perkins and Hill (1985) also considered boredom to arise from repetition monotony, often resulting in high levels of frustration and unpleasantness along with low levels of interest and concentration. It was suggested that boredom may be viewed as having cognitive and affective components; the cognitive component was subjective monotony, and the affective component was a high level of frustration (Hill and Perkins, 1985). Soon afterwards, and perhaps for the first time in higher education, boredom was found negatively linked to academic performance as Maroldo (1986) reported a slight but significant and negative correlation between boredom and grade point average among students attending college in the United States.

Fahlman et al. (2013) defined boredom as a negative emotion composed of disengagement, dissatisfaction, attention deficit, altered time perception and decreased vitality. Disengagement was one of the most fundamental components of boredom, which was defined as a complete lack of engagement, effort, interest, enthusiasm and/or prosocial conduct. Disengagement entailed an individual’s total non-commitment and withdrawal from what others did with involvement and/or enjoyment (Skinner et al., 2009). Higher levels of boredom proneness could negatively impact attentional capacities, emotional well-being, and had been associated with problematic behavioral consequences (Isacescu et al., 2017).

Foreign language boredom

As research on boredom evolves into language classrooms, it is critical to understand its dynamic nature and to design pedagogical strategies that promote meaningful learner involvement. Foreign Language Learning Boredom was defined as “a negative, deactivating achievement emotion arising from ongoing learning activities or tasks” (Li et al., 2023, p. 224). Recent research on boredom in the language classroom traced the fluctuation (Zawodniak and Kruk, 2019), individual trajectories of boredom (Pawlak et al., 2022), and antecedent (Nakamura et al., 2021). Zawodniak and Kruk (2019) provided evidence that boredom reported by individual students changed from lesson to the next and within single classes and that the fluctuations were related to factors such as language activities, organization of the lessons or their phases. Kruk et al. (2021) found that boredom can be attributed to different constellations of factors such as repetitiveness, monotony and predictability of what transpired during a particular class. Pawlak et al. (2022) found out that the individual trajectories in experiencing boredom often deviated from the general patterns, being shaped by unpredictable constellations of individual and contextual factors. Empirical research on boredom antecedents in second language learning revealed that activity mismatch, lack of comprehension, insufficient L2 skills, task difficulties, input overload, and lack of ideas can result in emergence of boredom (Nakamura et al., 2021). Learners’ physical fatigue, unfavorable appraisals of classroom tasks and negative behaviors of classmates were also identified as the antecedents of boredom. Aubrey et al. (2020) shed light on the unfamiliarity with task procedures, motivational burden from previous learning experiences and a lack of social cohesion understood as the sense of belonging and acceptance by a peer group.

Foreign language learners including English major students experienced boredom in language classrooms. Pawlak et al. (2020a) shed valuable light on the factors underlying boredom in practical English classes at university level, in particular with respect to English majors, and resulted in the development of an instrument that can be used in future empirical investigations [i.e., the Boredom in Practical English Language Classes -Revised (BPELC-R)]. Factors studied include (1) disengagement, monotony and repetitiveness, (2) lack of satisfaction and challenge. Zawodniak et al. (2023) analyzed the five categories of factors which are likely to generate boredom among advanced learners of English, including (1) the language activities used in class; (2) teacher-related issues; (3) the mode of classroom arrangement; (4) a specific component of the English course, and (5) an amalgam of cause. Zawodniak et al. (2023) continued to explain the amalgam of cause may be described as somewhat idiosyncratic in nature as referred to “such subjective phenomena as feelings of compulsion, perceptions of peers, tiredness or concrete situations” (p. 31). In this research, teacher-related issues were evident including the “subcategories of lack of involvement, insufficient explanations, excessive teacher talk and teacher characteristics” (p. 32).

Research of foreign language boredom also expanded from the in-person foreign language classes to online English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classes. As Derakhshan et al. (2022a) and Derakhshan et al. (2022b) identified 10 activity types that were boredom inducing in online classes. “The most frequently mentioned activity type was non-engaging, teacher-led activities” (p. 62). These activities included teachers taking the initiative, and students turning to passive listeners; teachers teaching from the PowerPoint file or the book without further explaining the points or teacher talking at length on a topic without soliciting students’ opinions and engaging them in a meaningful discussion. According to Derakhshan et al. (2022a) and Derakhshan et al. (2022b), the activities that boredom was induced in online classes are similar to those found boring in pre-pandemic in-person English classes.

Recent studies have synthesized Foreign Language Learning Boredom (FLLB) as a highly dynamic, individualized, and context-sensitive phenomenon. While boredom often stems from predictable sources such as task monotony or unclear instruction, its expression varies widely across learners and situations. Research underscores that boredom fluctuates even within a single class session and is driven by complex interactions between task-related features, teacher behavior, classroom environment, and personal emotional states. Individual factors such as fatigue or previous learning experiences intersect with broader contextual elements like classroom organization and social cohesion, creating highly idiosyncratic boredom profiles. As boredom manifests in both in-person and online settings, common triggers such as passive, teacher-led instruction and lack of student engagement persist across modalities. This growing body of literature offers a nuanced understanding of FLLB and highlights the need for pedagogical approaches that are flexible, interactive, and responsive to learners’ emotional and cognitive needs.

Foreign language boredom in China EFL context

Foreign Language Boredom is an emerging topic in research on foreign language classroom. Recently, a few articles showed interest in the field of boredom in the China EFL context.

In China, there are a huge population of English language learners in higher education. It has been reported that English learners in China feel high language learning boredom either in class or after class and the negative effect has been highlighted (Li et al., 2023; Li and Han, 2024). Li (2022) qualitative research with Chinese university students showed that Foreign Language Boredom is a negative academic emotion which deactivates them from ongoing Foreign Language (FL) learning activities which are typically viewed as overchallenging, under-challenging, uninteresting, irrelevant, unimportant, dull or tedious. Li and Han (2024) conducted a qualitative study, and the participants perceived wide-ranging learner-internal and learner-external factors as sources of their foreign language learning boredom. These factors are task characteristics, teaching and learning activities, student factors, course content, classroom factors, teacher factors, and feeling unoccupied in the class.

Research has identified the boredom experiences and extrapolating the typical occurrence in class (Li et al., 2023). Boredom is common in the EFL classroom among Chinese university students as most participants reported boredom and the types of boredom include momentary state boredom as well as trait boredom. The qualitative research project led by Li et al. (2023) revealed that more than 90% of students reported boredom in FL settings. They reported that in the open questionnaire, 610 out of the 659 (92.6%) student participants recalled boredom-inducing situations either in foreign language class or after class in relation to English learning; Also, this research found that a large majority of students (92.8%) reported experiencing occasional boredom episodes in EFL settings. The 22 students interviewed reported 49 instances of boredom experiences in English class. The following is an example of an interview excerpt from a female student.

Honestly speaking, I think English is of no relevance to our major. I feel so bored and sleepy in English class, especially bored of English words and grammar…I think the main reason is I do not have any interest in English, and I do not care about English at all (student interview extract # 4) (Li et al., 2023, p. 12).

While the words describing boredom include sleepiness, disengagement, annoyance, and no interest. “Lack of interest” was the most frequently mentioned in the data (Li et al., 2023).

Based on the results of questionnaire and interview, Li et al. (2023) conducted phase 2 research which contributed to conceptualization and measurement. In this study, researchers adopted the three-dimension taxonomy of the control-value theory (Pekrun and Perry, 2014) to conceptualize Foreign Language Learning Boredom’ (FLLB) along three dimensions with two antecedents. The three dimensions are valence (positive or negative), arousal (degree of activation), and object focus (activity-related or outcome -related). The two appraisal antecedents are control (degree of controllability) and value (relevance/meaning/interest).

In addition, this study used the new conceptualization to develop and validate a 7-factor, 32-item scale for Foreign Language Boredom. The seven factors are: “Foreign Language Learning Classroom Boredom, Underchallenging Task Boredom, PowerPoint Presentation Boredom, Homework Boredom, Teacher Dislike Boredom, General Learning Trait Boredom, and Overchallenging or Meaningless Task Boredom” (p. 4). Later, this scale was refined and shortened into eight-item Foreign Language Classroom Boredom Scale, which was applied in more diverse learner groups, in both in-person and online contexts in countries like China, Thailand, UK, and Italy (Li et al., 2024).

Some research studied foreign language boredom in different language domains such as reading comprehension (Jiang, 2023; Mariusz, 2021; Yang et al., 2024), and listening comprehension (Waleed et al., 2021). Jiang (2023) reported that reading self-efficacy, intrinsic cognitive load, and reading boredom are important factors explaining the difference in English reading performance. Waleed et al. (2021) investigated the relationship between listening boredom and EFL listening comprehension performance of Saudi EFL learners. There exists a significant yet negative association between listening boredom and listening comprehension performance.

While these studies have generated pioneering insights into foreign language boredom in China context, their limitations suggest the need for research with more empirical research on teacher factors. For instance, Li et al. (2024) recommended that future investigators explore potential influence of situational factors as potential mediators between teacher factor (teacher clarity and immediacy) and students’ boredom.

In conclusion, research on Foreign Language Learning Boredom (FLLB) in the Chinese EFL context has revealed it to be a prevalent and complex emotional experience, with both situational and individual antecedents. Students commonly report boredom stemming from irrelevant or unengaging tasks, lack of interest, and teacher-related factors. Qualitative and quantitative studies have contributed to conceptualizing FLLB through control-value theory and developing valid measurement tools. Despite these advances, current research is still limited, especially regarding the mediating role of teacher-related factors. Future studies should adopt a more empirical and multidimensional approach to better understand and address FLLB in diverse learning contexts.

Teacher-related boredom

Emerging terms of teacher-related boredom

The surge of interest in boredom in foreign language education will help capture the teacher-related boredom and identify its sources. Also, the research will offer operational tools for future study and will offer teachers insight into ways to counter it.

Among the limited research, teacher-related boredom was implicitly mentioned by similar terms, such as “teacher dislike” (Daschmann et al., 2011), “teacher behavior” (Zawodniak et al., 2017), “teacher-related issue” (Zawodniak et al., 2023), and more specifically, “teacher-induced boredom” (Kruk et al., 2022).

Instructors are perceived by learners as having the prime responsibility for learner interest or boredom (Small and Jiang, 1996). One of the seven situational precursors to classroom boredom proposed by Daschmann et al. (2011) was ‘teacher dislike,’ alongside monotony, lack of meaning, opportunity costs, being over-challenged, being under-challenged, and lack of involvement. Rosas et al. (2016) collected significant data on how teachers’ behaviors in the classroom influence students’ emotions (boredom and enjoyment). The finding indicates that among the 6 factors (exemplifying-interaction, organization, support, enthusiasm, clarity, pace), the exemplifying interaction, teacher support and clarity had high predictive value on student boredom.

Chapman (2013) found a meaningful predictor of boredom was not related to a language activity or its feature, but to the students’ attitude toward their teachers. This attitude was a meaningful predictor of student boredom than any other classroom activities and features. Other researchers began to connect the causes of boredom with teachers since many of the precursors are related to teachers’ behaviors. Zawodniak et al. (2017) stated that “Teachers constitute yet another source of boredom” (p. 434). Learners were more prone to boredom with uninteresting, unlikeable, and unmotivated teachers (Derakhshan et al., 2022a; Derakhshan et al., 2022b).

Teachers’ perceptions of boredom and teacher-related boredom

Although teachers are blamed for causing student boredom, they tend to overlook the existing negative emotions experienced by students. For quite a long time, boredom has received little attention from researchers and teachers, even as the teacher-related boredom becomes increasingly apparent. According to Daschmann et al. (2014), the most remarkable fact is that teachers did not mention themselves as the origins of boredom unless they were explicitly asked about it in the quantitative questionnaire. Boredom has been also neglected by instructors who normally attribute it to learners’ laziness, anxiety, frustration, or passive personality factors (Macklem, 2015). Similarly, Derakhshan et al. (2021) stated that grassroots teachers might ignore this negative emotion arising from their students’ struggles.

Teachers’ neglect of teacher-related boredom can lead to negative teaching outcomes. As Pawlak et al. (2020b) found, L2 educators sometimes make wrong assumptions and misjudge this aversive emotion by treating it as an unworthy and trivial issue in the classroom. However, understanding its dynamics is of paramount significance in the language teaching process.

Studies on teacher-related boredom

Recently, there has been a positive trend that EFL teachers are beginning to recognize and self-report the student boredom. According to Li et al. (2023), 11 English teachers were asked about their perceptions of their students’ emotional experiences of boredom. Each teacher recalled at least one episode when students got bored, and they reported 34 instances in total.

With the recognition of teacher-related foreign language boredom, researchers explored more deeply on the causes of it. Psychologists examined the causes of boredom and found that students become bored and thus withdraw from classes, with under-stimulation resulting from unchallenging and repetitive activities (Larson and Richards, 1991), excessive teacher control (Hill and Perkins, 1985), or inattention (LePera, 2011). These factors are all directly related to teachers, including teaching approaches, content, and the teacher-student relationship. According to Nakamura et al. (2021), the antecedents of boredom are largely related to the negative aspects of lessons and teachers. This explicitly identified the teachers as a cause of boredom in the foreign language learning process.

Research with college non-English major students in China found similar patterns of teacher-related boredom. Dewaele and Li (2021) adopted a mixed-method approach to examine the complex relationships between perceived teacher enthusiasm, emotions (enjoyment and boredom), and social-behavioral learning engagement among 2,002 EFL learners from 11 universities in China. The research found that student enjoyment and boredom were found to co-mediate the relationship between perceptions of teacher enthusiasm and student social-behavioral engagement in English classes. Li (2022) studied the teacher variables (friendliness, enthusiasm, and predictability) in foreign language boredom and found that teacher friendliness was shown to be the strongest teacher-related predictor of Foreign Language Enjoyment and Foreign Language Boredom. Li and Han (2024) found out that teacher factors accounted for 3.7% of the cases of foreign language learning boredom, while course content (5.1%), classroom factors (4.4%), being unoccupied (1.1%). Xu et al. (2024) supports Zhang (2022) by identifying that teachers’ clarity and immediacy were robust predictors of English language learners’ boredom, with 48% of variance in boredom accounted for by teachers’ immediacy and 53% attributed to teachers’ clarity.

Researchers also explored the types of teacher factors. Li and Han (2024) believe that in the foreign language classroom, English learners feel bored due to two types of teacher factors: teaching skills and teacher personality and emotion. Perceived inadequate teaching skills, such as poor time management, teacher-dominant instruction, or irrelevant digression from the course content. In addition, teacher personality, such as being rigorous, strict, lenient and laissez-faire, also interacted with task characteristics in shaping students’ experience of boredom (Li and Han, 2024).

Researchers also found teacher-related foreign language boredom exist among English major students in China. As Zhang (2022) pointed out that rigid teaching methods, teacher-controlled classroom, and tedious speeches are the teacher-related boredom in a translation course for foreign language major students in China. Zhang (2022) also mentioned that the cause of teacher-related boredom includes their poor teaching skills, untimed feedback, boring speech/presentation, and weak rapport with students and proposed the emotion-based pedagogy for EFL teachers.

Researchers also try to investigate whether the online teaching mode will affect the student boredom (Li and Dewaele, 2020). Liu and Xie (2024) reports that factors that are responsible for English major student boredom in online live EFL teaching mode. They are teacher-centered classes, less engagement and interaction, high task challenges, monotonous and long learning activities, textbook-based activities, students’ lack of self-discipline, peer influences, the absence of emotional support, unreliable internet connection, physical fatigue, a locked-down campus, and a dormitory learning environment. Students’ greater boredom in online live settings than in-person settings arose from student-related factors, technological factors, and environment-related factors.

Research also studied the impact of teacher emotions on student boredom, especially whether teacher boredom affects the student boredom. Teacher boredom was postulated as a “precursor to student boredom” (Tam et al., 2021, p. 126), and its effects on students’ boredom levels and learning motivation were examined. The study found that students felt more bored and reported lower motivation to learn when they perceived their teacher to be bored (Tam et al., 2021).

Recent research highlights a growing recognition among EFL teachers of student boredom, prompting deeper investigations into teacher-related causes. Teachers themselves have reported instances of student disengagement, which aligns with psychological findings that under-stimulation, excessive teacher control, and weak teacher-student rapport can trigger boredom. Studies in the Chinese EFL context confirm that teacher factors—such as enthusiasm, clarity, immediacy, friendliness, and instructional style—significantly influence student boredom and engagement. These factors encompass both teaching skills (e.g., time management, content delivery) and personality traits (e.g., warmth, rigidity). Teacher-centered approaches, inadequate feedback, and monotonous teaching were found to increase boredom in both general and major-specific courses, such as translation. The issue is amplified in online teaching contexts, where lack of interaction, emotional support, and external distractions exacerbate student boredom. Notably, teacher boredom itself has been identified as a contributing factor to student boredom, further emphasizing the reciprocal emotional dynamic within the language classroom.

Key variables influencing student boredom

Gender, major program and language proficiency have been studied as key variables influencing student boredom.

Studies argue that gender differences mediate EFL student boredom. Wang et al. (2022) studied gender differences in state boredom and reported the different level of boredom in foreign language learning with statistically gender differences. The study found that males had higher state boredom than females. According to this finding, different practical implications are suggested to reduce student boredom in the language acquisition. The strategies are gender-specific, such as, to encourage male students to focus on the utility value of what they are learning to enhance their motivation and minimize boredom during learning; female students may be encouraged to use more behavioral avoidance strategies, such as chatting with peers, during the learning task to avoid exhausting situations. Another study utilizing qualitative method on student English reading boredom revealed that students’ experience of boredom varied; male students read for pleasure, while female students read with specific goals in mind (Wisyarah, 2024). Studies showed contradictory result, as Coşkun and Yüksel (2022) found that there was no difference observed in the level of boredom depending on gender variable among 680 high school EFL Turkish students. In addition, this study revealed that the students who chose the science track experienced the highest level of boredom (Coşkun and Yüksel, 2022). Hence, the major program could be considered as one factor influencing the foreign language boredom. According to Pekrun (2024), Control-value Theory research has shown that academic emotions vary across subject domains and time. However, this topic was not adequately discussed.

There are studies on language proficiency as variables on boredom. Pawlak et al. (2020a) studied English major students and showed that low-achievers regarded both Factor 1 (i.e., Disengagement, monotony and repetitiveness) and Factor 2 (i.e., Lack of satisfaction and challenge) as more boredom-evoking in English language classes than high-achievers. Pawlak et al. (2020a) also suggest research specifically probe into the relationship between boredom and other ID variables. Similarly, some studies on Chinese EFL students revealed that Chinese EFL students with higher self-perceived achievement reported higher levels of Foreign Language Enjoyment and lower levels of Foreign Language Boredom (Liu and Wang, 2024). On the contrary, Wisyarah (2024) in study of reading boredom found that high achievers deal with boredom more often in English reading. According to the previous research, Chinese EFL students feel more bored in online class settings (Liu and Xie, 2024) and there is no research prone into the teacher-related factors on it.

Factor structure of main teacher-related EFL student boredom

According to Control-value Theory, social factors that impact control-value appraisals also influence the emotions resulting from these appraisals. Important factors considered in Control-value Theory include (1) the cognitive quality of achievement environment; (2) the emotional and motivational quality of environment; (3) autonomy support; (4) social expectations, goal structures and social interaction; (5) feedback about achievement; (6) the composition of groups (Pekrun, 2024).

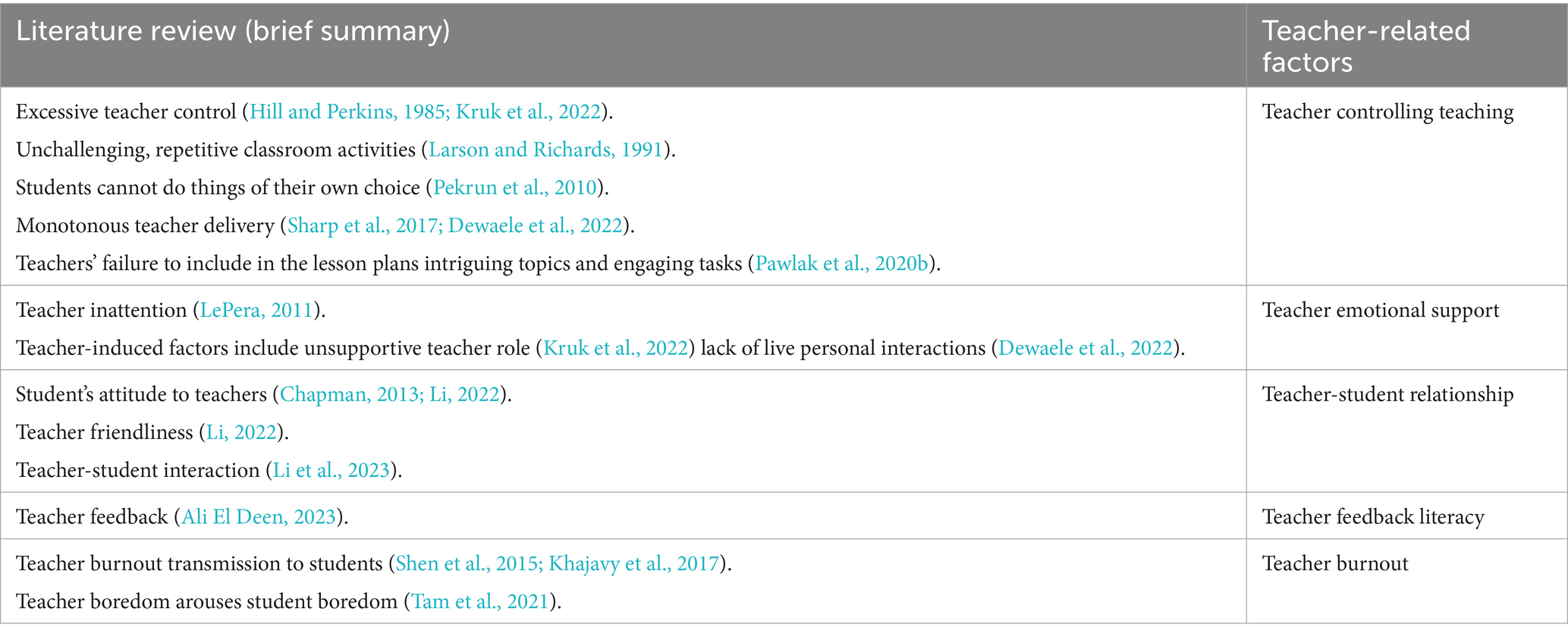

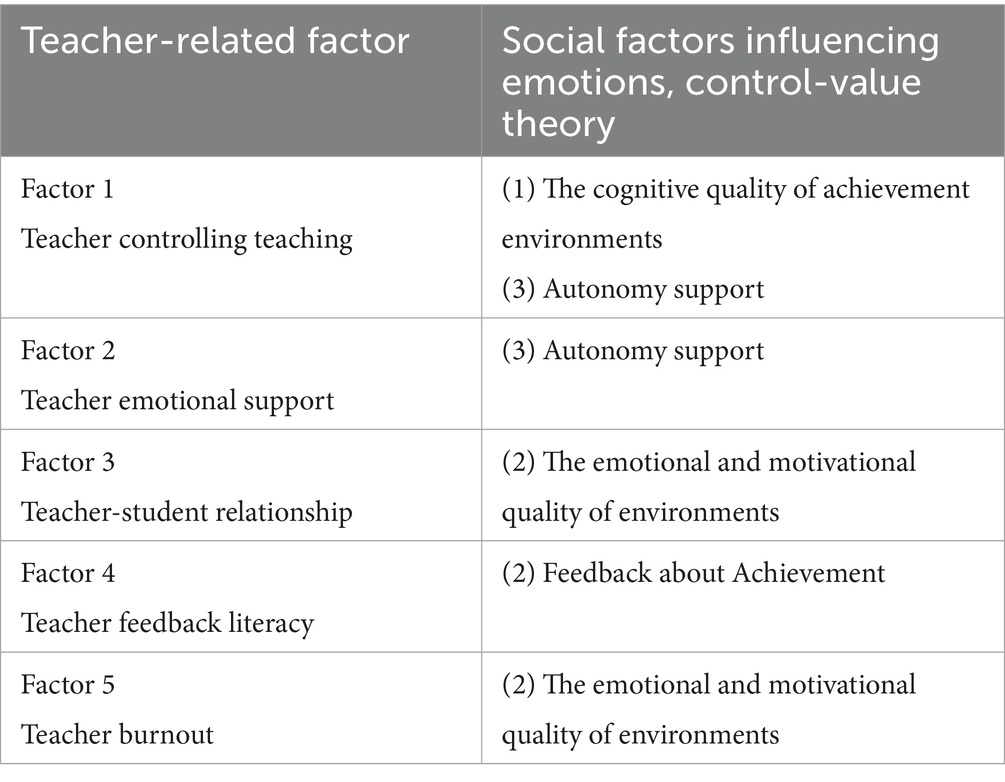

The social factors can be applied in factor structure of main teacher-related EFL student boredom of this study (Table 1).

Table 1. Factor structure of 5 teacher-related EFL student boredom from perspective of control-value theory.

Control-value theory explains how students’ emotions affect motivation and learning. When teachers support students’ sense of control and highlight the value of tasks, they can reduce negative emotions and boost engagement and success.

The following analysis examines how each of the five factors aligns with key components of the theory.

Factor 1 teacher controlling teaching—(1) the cognitive quality of achievement environments and (3) autonomy support

The cognitive quality of achievement environment, such as the learning environment in the classroom, influences the acquisition of competencies, the competent performance of achievement activities and resulting control perceptions (Pekrun et al., 2023). High quality environment can boost value, by fulfilling needs for competence. It is believed that negative emotions can result if tasks are too demanding, lack of control. Considering teacher-related factors on the cognitive quality of achievement environment, teacher excessive class control may be one teacher-related factor to EFL student boredom, as Kruk et al. (2022) explained in the research that teacher-induced factors include excessive class control, teaching practices and unsupportive role. Hence, teacher controlling teaching will be considered.

Autonomy support can influence both control and value. Providing choice between tasks and strategies to perform tasks is thought to promote competence and fulfill needs for autonomy, thus boosting control, positive value, and the resulting positive emotions (Cui et al., 2017). Excessive class control, or teacher controlling teaching, providing inadequate choice for students, will result in negative emotions, like boredom.

Factor 2 teacher emotional support—(3) autonomy support

The second teacher-related factor to EFL student boredom is teacher emotional support, which can be considered as Autonomy support too, one of the social factors that induced boredom. Study by Derakhshan et al. (2022a) and Derakhshan et al. (2022b) revealed that classroom social climate negatively predicted boredom. More specifically, teachers’ academic and emotional support and mutual respect help create a positive classroom environment, which in turn reduces learners’ disengagement and dissatisfaction, thus alleviating their sense of boredom. According to Amiri et al. (2022), teachers were also seen as important elements who directly contribute to students’ fight against boredom through creating an emotionally safe and supportive environment.

Factor 3 teacher-student relationship—(2) the emotional and motivational quality of environments

According to Pekrun (2024), the emotional and motivational quality of environments impacts value appraisals, thus influencing achievement emotions. Value induction can take both direct and indirect forms. Direct induction includes verbal messages about the importance of achievement; indirect induction consists of nonverbal messages.

Teacher-student interaction is direct induction while teacher-student relationships are nonverbal induction. Both forms of induction affect the student boredom. Dewaele et al. (2022) found that the lack of live personal interactions and the monotonous teacher delivery could induce students’ disengagement and cause boredom. Research also found that the combined variables of teacher immediacy and professor- student rapport are better predictors of motivation, which the professor- student rapport appears to be the greatest contributor to these relationships (Estepp and Roberts, 2015).

Factor 4 teacher feedback literacy—(2) feedback about achievement

According to Control-value theory, feedback about achievement shaped perceptions of control, and the consequences of achievement (financial gratifications, career opportunities etc.) influenced perceptions of (extrinsic) value (Pekrun, 2024).

Teacher feedback literacy is a crucial factor of foreign language boredom. The negative relationship between boredom and perceived learning was weaker when teachers provided higher levels of feedback (Chan and Ko, 2021). Teacher feedback factor was among the 7 factors that caused the boredom of EFL students in Saudi Arabia context (Ali El Deen, 2023). Students who perceived more teacher feedback gained more enjoyment in reading activities (Ma et al., 2024).

Factor 5 teacher burnout—(2) the emotional and motivational quality of environments

Teacher burnout can also be explained by the emotional and motivational quality of environment. Aloe et al. (2014) stated that educator burnout syndrome could result in absenteeism, which straightforwardly affects learner’s scholastic presentation, and results in more indifference of children. Keller et al. (2014) investigated boredom among educators and proved that educators encounter considerable boredom from instruction in the class in around one-fourth of all sessions. A prime example given by Frenzel et al. (2024) proved that transmission of the emotions displayed by others was indirect induction. Teacher burnout indirectly resulted in student boredom (Table 2).

Scholarly significance

Identifying teacher-related factors that are related to foreign language boredom can result in theoretical, empirical, and practical implications. Theoretically, the findings will lead to support to related theories, suggest potential to extend emotion research in second language education. Empirically, the study context and measurements used can extend the existing literature, enhance understanding of different teacher-related factors and the potential influence on student language boredom. Practically, the significance of teacher’s role and teacher-related factors can be emphasized due to the relational nature of foreign language learning. Contributing to student positive affective experiences.

Future study focus and limitation

Further study should focus on answering the following questions such as:

What is the relationship among the five teacher-related factors (teacher controlling teaching, teacher emotional support, teacher feedback literacy, teacher-student rapport, and teacher burnout)? Which teacher-related factors are more strongly linked to the foreign language boredom of English-learning college students in China?

How do teacher-related factors impact foreign language boredom across different teaching modes? How do gender, major program, and language proficiency mediate the relationship between teacher-related factors and student boredom?

As the studies conducted in China were primarily reviewed as examples, the findings may reflect geographical and cultural limitation, thus this would highlight the need for future comparative research across different contexts to enhance generalizability.

Conclusion

In summary, the existing research has laid some basic and fundamental knowledge, clearly outlined how complex, pervasive, and unpredictable the experience of boredom can be, as well as the potential to impact foreign language learning. However, a systematic and comprehensive study on teacher-related boredom in EFL classrooms remained unexplored. In this study, the selection of the five key factors was based on inductive and deductive approaches. An inductive review of recent empirical studies in the field of student boredom to identify recurring themes and factors. A deductive approach was used to identify teacher-related factors, drawing on the framework of Control-Value Theory (Pekrun, 2024). Then how each of the five factors aligns with key components of the theory was examined. Examples are used to further support this alignment. The examples were from previous studies conducted with EFL students, situating this analysis within the field of SLA.

Understanding teacher-related boredom in EFL classrooms can provide researchers and educators in the field of second language acquisition with valuable insights into the mechanisms of this negative academic emotion, helping to inform instructional practices and enhance learner engagement and outcomes, particularly for English language learners in Chinese universities.

Author contributions

FL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. HC: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali El Deen, A. A. M. M. (2023). Students' boredom in English language classes: voices from Saudi Arabia. Front. Psychol. 14:1108372. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1108372

Aloe, A. M., Shisler, S. M., Norris, B. D., Nickerson, A. B., and Rinker, T. W. (2014). A multivariate meta-analysis of student misbehavior and teacher burnout. Educ. Res. Rev. 12, 30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.05.003

Amiri, E., Elkarfa, A., Sbaihi, M., Iannàccaro, G., and Tamburini, E. (2022). Students’ experiences and perceptions of boredom in EFL academic context. Int. J. Lang. Lit. Stud. 4, 273–288. doi: 10.36892/ijlls.v4i4.1140

Aubrey, S., King, J., and Almkiled, H. A. A. (2020). Language learner engagement during speaking tasks: a longitudinal study. RELC J. 53, 519–533. doi: 10.1177/0033688220945418

Chan, S. C., and Ko, S. (2021). The dark side of personal response systems (PRSs): boredom, feedback, perceived learning, learning satisfaction. J. Educ. Bus. 96, 435–444. doi: 10.1080/08832323.2020.1848769

Chapman, K. E. (2013). Boredom in the German foreign language classroom (doctoral dissertation). Madison, US: The University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Coşkun, A., and Yüksel, Y. (2022). Examining English as a foreign language students' boredom in terms of different variables. Acuity J. Eng. Lang. Pedagogy Lit. Cult. 7, 19–36. doi: 10.35974/acuity.v7i2.2539

Cui, G., Yao, M., and Zhang, X. (2017). The dampening effects of perceived teacher enthusiasm on class-related boredom: the mediating role of perceived autonomy support and task value. Front. Psychol. 8:400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00400

Daschmann, E. C., Goetz, T., and Stupnisky, R. H. (2011). Testing the predictors of boredom at school: development and validation of the precursors to boredom scales. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 81, 421–440. doi: 10.1348/000709910X526038

Daschmann, E. C., Goetz, T., and Stupnisky, R. H. (2014). Exploring the antecedents of boredom: do teachers know why students are bored? Teach. Teach. Educ. 39, 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.009

Derakhshan, A., Dewaele, J. M., and Noughabi, M. A. (2022a). Modeling the contribution of resilience, well-being, and L2 grit to foreign language teaching enjoyment among Iranian English language teachers. System 109:102890. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102890

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, M., Mehdizadeh, M., and Pawlak, M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: sources and solutions. System 101:102556. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102556

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, M., Mehdizadeh, M., and Pawlak, M. (2022b). Activity-induced boredom in online EFL classes. ELT J. 76, 58–68. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccab072

Dewaele, J., Albakistani, A., and Kamal Ahmed, I. (2022). Levels of foreign language enjoyment, anxiety and boredom in emergency remote teaching and in in-person classes. Lang. Learn. J. 50, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2022.2110607

Dewaele, J. M., and Li, C. (2021). Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: the mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Lang. Teach. Res. 25, 922–945. doi: 10.1177/13621688211014538

Estepp, C. M., and Roberts, T. G. (2015). Teacher immediacy and professor/student rapport as predictors of motivation and engagement. NACTA J. 59, 155–163.

Fahlman, S. A., Mercer-Lynn, K. B., Flora, D. B., and Eastwood, J. D. (2013). Development and validation of the multidimensional state boredom scale. Assessment 20, 68–85. doi: 10.1177/1073191111421303

Frenzel, A. C., Dindar, M., Pekrun, R., Reck, C., and Marx, A. K. G. (2024). Joy is reciprocally transmitted between teachers and students: evidence on facial mimicry in the classroom. Learn. Instr. 91:101896. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101896

Isacescu, J., Struk, A. A., and Danckert, J. (2017). Cognitive and affective predictors of boredom proneness. Cognit. Emot. 31, 1741–1748. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1259995

Jiang, C. (2023). Chinese undergraduates’ English reading self-efficacy, intrinsic cognitive load, boredom, and performance: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 14:1093044. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1093044

Keller, M. M., Chang, M. L., Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., and Frenzel, A. C. (2014). Teachers’ emotional experiences and exhaustion as predictors of emotional labor in the classroom: an experience sampling study. Front. Psychol. 5:1442. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01442

Khajavy, G. H., Ghonsooly, B., and Fatemi, A. H. (2017). Testing a burnout model based on affective-motivational factors among EFL teachers. Curr. Psychol. 36, 339–349. doi: 10.1007/s12144-016-9423-5

Kruk, M., Pawlak, M., Shirvan, M. E., Taherian, T., and Yazdanmehr, E. (2022). Potential sources of foreign language learning boredom: a Q methodology study. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 12, 37–58. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2022.12.1.3

Kruk, M., Pawlak, M., and Zawodniak, J. (2021). Another look at boredom in language instruction: the role of the predictable and the unexpected. Stud. Second Language Learn. Teach. 11, 15–40. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.1.2

Larson, R., and Richards, M. (1991). Boredom in the middle school years: blaming schools versus blaming students. Am. J. Educ. 99, 418–443. doi: 10.1086/443992

LePera, N. (2011). Relationships between boredom proneness, mindfulness, anxiety, depression, and substance use. New Sch. Psychol. Bull. 8, 15–25. doi: 10.1037/e741452011-003

Li, C. (2022). Foreign language learning boredom and enjoyment: the effects of learner variables and teacher variables. Lang. Teach. Res. 29:324. doi: 10.1177/13621688221090324

Li, C., and Dewaele, J. M. (2020). The predictive effects of trait emotional intelligence and online learning achievement perceptions on foreign language class boredom among Chinese university students. Foreign Lang. Foreign Lang. Teach. 5, 33–44. doi: 10.13458/j.cnki.flatt.0047112020.

Li, C., Dewaele, J. M., and Hu, Y. (2023). Foreign language learning boredom: conceptualization and measurement. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 14, 223–249. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2020-0124

Li, C., Feng, E., Zhao, X., and Dewaele, J. M. (2024). Foreign language learning boredom: refining its measurement and determining its role in language learning. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 46, 893–920. doi: 10.1017/S0272263124000366

Li, C., and Han, Y. (2024). Learner-internal and learner-external factors for boredom amongst Chinese university EFL students. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 15, 901–926. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2021-0159

Liu, E., and Wang, J. (2024). The effects of student and teacher variables on anxiety, enjoyment, and boredom among Chinese high school EFL learners. Int. J. Multiling. 21, 1454–1475. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2023.2177653

Liu, W., and Xie, Z. F. (2024). Investigating factors responsible for more boredom in online live EFL classes. SAGE Open 14:21582440241292901. doi: 10.1177/21582440241292901

Ma, L., Xiao, L., and Jiao, Y. (2024). Mediation of reading enjoyment between teacher feedback and reading achievement: cross-cultural generalizability across 75 countries/economies. J. Exp. Educ. 92, 431–451. doi: 10.1080/00220973.2023.2208063

MacIntyre, P., and Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: the positive-broadening power of the imagination. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2:193. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

MacIntyre, P. D., and Vincze, L. (2017). Positive and negative emotions underlie motivation for L2 learning. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 7, 61–88. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.4

Macklem, G. L. (2015). Boredom in the classroom: Addressing student motivation, self-regulation, and engagement in learning. (Vol. 1) Berlin: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-13120-7

Mariusz, K. (2021). Investigating the experience of boredom during reading sessions in the foreign language classroom. J. Lang. Educ. 7, 89–103. doi: 10.17323/jle.2021.12339

Maroldo, G. (1986). Shyness, boredom, and grade point average among college students. Psychol. Rep. 59, 395–398. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1986.59.2.395

Mora, R. (2011). "School is so boring": high-stakes testing and boredom at an urban middle school. Penn GSE Perspect. Urban Educ. 9:n1.

Nakamura, S., Darasawang, P., and Reinders, H. (2021). The antecedents of boredom in L2 classroom learning. System 98:102469. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102469

O’Hanlon, J. F. (1981). Boredom: practical consequences and a theory. Acta Psychol. 49, 53–82. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(81)90033-0

Pawlak, M., Kruk, M., and Zawodniak, J. (2022). Investigating individual trajectories in experiencing boredom in the language classroom: the case of 11 polish students of English. Lang. Teach. Res. 26, 598–616. doi: 10.1177/1362168820914004

Pawlak, M., Kruk, M., Zawodniak, J., and Pasikowski, S. (2020a). Investigating factors responsible for boredom in English classes: the case of advanced learners. System 91:102259. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102259

Pawlak, M., Zawodniak, J., and Kruk, M. (2020b). The neglected emotion of boredom in teaching English to advanced learners. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 30, 497–509. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12302

Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: from achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 36:83. doi: 10.1007/s10648-024-09909-7

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H., and Perry, R. P. (2010). Boredom in achievement settings: exploring control–value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 531–549. doi: 10.1037/a0019243

Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Elliot, A. J., Stockinger, K., Perry, R. P., Vogl, E., et al. (2023). A three-dimensional taxonomy of achievement emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 124:145. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000448

Pekrun, R., and Perry, R. P. (2014). “Control-value theory of achievement emotions” in International handbook of emotions in education (Oxfordshire, England, UK: Routledge), 120–141.

Perkins, R. E., and Hill, A. B. (1985). Cognitive and affective aspects of boredom. Br. J. Psychol. 76, 221–234. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1985.tb01946.x

Richards, J. C. (2022). Exploring emotions in language teaching. RELC J. 53, 225–239. doi: 10.1177/0033688220927531

Rosas, J. S., Esquivel, S., and Cara, M. (2016). The teacher behaviors inventory: internal structure, reliability, and criterion relations with boredom, enjoyment, task value, self-efficacy and attention. Psycho Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 37–51.

Sharp, J. G., Hemmings, B., Kay, R., Murphy, B., and Elliott, S. (2017). Academic boredom among students in higher education: a mixed-methods exploration of characteristics, contributors and consequences. J. Furth. High. Educ. 41, 657–677. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2016.1159292

Shen, B., McCaughtry, N., Martin, J., Garn, A., Kulik, N., and Fahlman, M. (2015). The relationship between teacher burnout and student motivation. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 85, 519–532. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12089

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., and Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children's behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 69, 493–525. doi: 10.1177/0013164408323233

Small, R. V., and Jiang, X. (1996). Dimensions of interest and boredom in instructional situations. Proceedings of Selected Research and Development Presentations at the 1996 National Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (18th, Indianapolis, US) 712.

Tam, K. Y., van Tilburg, W. A., Chan, C. S., Igou, E. R., and Lau, H. (2021). Attention drifting in and out: the boredom feedback model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 25, 251–272. doi: 10.1177/10888683211010297

Van Tilburg, W. A. P., and Igou, E. R. (2017). Boredom begs to differ: differentiation from other negative emotions. Emotion 17, 309–322. doi: 10.1037/emo0000233

Waleed, S. M., Besher, A. K., Summaira, S., and Shazma, R. (2021). Listening boredom, listening boredom coping strategies, and listening performance: exploring the possible relationships in Saudi EFL context. J. Lang. Educ. 7, 136–150. doi: 10.17323/jle.2021.12875

Wang, H., Xu, Y., Song, H., Mao, T., Huang, Y., Xu, S., et al. (2022). State boredom partially accounts for gender differences in novel lexicon learning. Front. Psychol. 13:807558. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.807558

Wisyarah, N. (2024). Students’ reading boredom coping strategies and reading performance: from gender perspective, University of Islam Malang, Malang, Indonesia.

Xu, J., Pan, Y., and Derakhshan, A. (2024). The interrelationship between Chinese English as a foreign language teachers’ immediacy and clarity with learners’ boredom. Percept. Mot. Skills 131:00315125241272524. doi: 10.1177/00315125241272524

Yang, K., Gan, Z., and Sun, M. (2024). EFL students’ profiles of English reading self-efficacy: relations with reading enjoyment, engagement, and performance. Lang. Teach. Res. 1–24. doi: 10.1177/13621688241268891

Zawodniak, J., and Kruk, M. (2019). Boredom in the English language classroom: an investigation of three language learners. Konin Lang. Stud. 7, 197–214. doi: 10.30438/ksj.2019.7.2.5

Zawodniak, J., Kruk, M., and Chumas, J. (2017). Towards conceptualizing boredom as an emotion in the EFL academic context. Konin Lang. Stud. 5, 425–441. doi: 10.30438/ksj.2017.5.4.3

Zawodniak, J., Kruk, M., and Pawlak, M. (2023). Boredom as an aversive emotion experienced by English majors. RELC J. 54, 22–36. doi: 10.1177/0033688220973732

Keywords: teacher-related boredom, factor structure, literature review, EFL, emotion

Citation: Liu F and Cho H (2025) Factor structure of teacher-related boredom in EFL classroom: a mini literature review. Front. Educ. 10:1641256. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1641256

Edited by:

Enrique H. Riquelme, Temuco Catholic University, ChileReviewed by:

Ogi Danika Pranata, Institut Agama Islam Negeri Kerinci, IndonesiaRingphami Shimray, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand

Copyright © 2025 Liu and Cho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fang Liu, ZmFuZy5saXUuMUBuZHVzLmVkdQ==

Fang Liu

Fang Liu Hyonsuk Cho

Hyonsuk Cho