- Education Studies, University of Limpopo, Sovenga, South Africa

This study investigated mainstream educators’ understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in South Africa’s Tzaneen Circuit, aiming to assess their knowledge, attitudes, and classroom practices regarding inclusive education for autistic learners. Despite progressive policies like White Paper 6 (2001), implementation gaps persist in rural areas due to limited training and resources. Using a qualitative case study design, data from six educators revealed limited ASD knowledge primarily gained through informal means, positive but strained attitudes toward inclusion, and systemic challenges like overcrowded classrooms and lack of specialist support. While educators demonstrated adaptive strategies, the findings highlight critical needs: enhanced teacher training, accessible resources, and stronger policy implementation to achieve equitable inclusion. The study underscores the urgency of addressing these gaps in under-resourced settings through collaborative, systemic reforms to empower educators and improve outcomes for autistic students.

1 Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent challenges in social communication and interaction, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Globally, ASD prevalence has risen significantly in recent decades, with current estimates suggesting 1 in 100 children are affected (World Health Organization, 2022). This increasing prevalence has led to growing numbers of autistic learners entering mainstream educational settings, presenting both opportunities and challenges for inclusive education systems.

In South Africa, the post-apartheid education reforms culminated in White Paper 6 (2001), which established a framework for inclusive education. This policy mandates that all learners, including those with disabilities like ASD, should have access to quality education in mainstream schools. However, the successful implementation of inclusive education depends heavily on educators’ awareness, understanding, and preparedness to support diverse learners. While special education teachers typically receive targeted training, mainstream educators often lack adequate preparation to meet the needs of autistic students (Walton, 2017a, 2017b).

Despite these progressive frameworks, virtually no empirical studies have captured the voices and classroom realities of mainstream teachers in rural Limpopo circuits. In particular, there is a paucity of educator-centred evidence on how policy intentions play out in under-resourced, circuit-level schools serving autistic learners. Therefore, this study investigates mainstream educators’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices for inclusion of learners with ASD in the Tzaneen Circuit, providing the first in-depth, context-specific account from this rural setting.

2 Research problem and questions

Despite progressive policies like South Africa’s White Paper 6 (2001) and the more recent Screening, Identification, Assessment, and Support (SIAS) policy (2014), significant gaps remain in the implementation of inclusive education for autistic learners. Research indicates that many mainstream educators lack sufficient training and resources to effectively support students with ASD (Gómez-Marí et al., 2021). This disconnect between policy and practice raises concerns about educational equity and the quality of learning experiences for autistic students in mainstream settings.

The problem is particularly acute in rural areas like Tzaneen Circuit, where access to specialized training and support services may be limited. Educators in these contexts often face large class sizes, limited resources, and minimal access to special education expertise, creating additional barriers to effective inclusion (Lindsay et al., 2014). Furthermore, cultural perceptions of disability and limited community awareness about ASD may compound these challenges.

This study addresses four key research questions:

1. Policy Awareness and Implementation: Are mainstream educators aware of educational policies related to ASD inclusion, and to what extent are these policies being implemented in classroom practice?

2. ASD Knowledge: What level of understanding do mainstream educators have about ASD characteristics and the specific needs of autistic learners?

3. Attitudes and Practices: How do educators’ attitudes toward students with ASD influence their instructional approaches and classroom management strategies?

4. Professional Development: Which types of training and support mechanisms are most effective in improving educators’ capacity to support autistic learners?

3 Mini literature review

3.1 Global and national policy frameworks

The right to inclusive education is enshrined in international agreements such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006) and the UNESCO (1994). These frameworks emphasize that students with disabilities should have access to general education systems with appropriate support. In South Africa, White Paper 6 (Department of Education, 2001) marked a radical departure from the segregated education system of the apartheid era, establishing inclusion as a cornerstone of the new democratic education system.

The SIAS policy (Department of Basic Education, 2014) operationalizes these principles by providing a standardized process for identifying and supporting learners who experience barriers to learning. However, research suggests that policy implementation has been uneven, with many schools lacking the necessary resources and trained personnel to effectively implement inclusive practices (Walton, 2017a, 2017b).

3.2 Educator knowledge and attitudes

Existing research reveals significant variation in educators’ knowledge about ASD. While some teachers demonstrate accurate understanding of core ASD characteristics, others hold misconceptions or lack awareness altogether (Gómez-Marí et al., 2021; Sepadi and Themane, 2025). This knowledge gap is particularly pronounced among mainstream educators compared to their special education counterparts.

Educator attitudes toward inclusion are similarly mixed. While many teachers express philosophical support for inclusion, practical concerns about classroom management, resource availability, and perceived impact on other students often temper this support (Roberts and Simpson, 2016). Attitudes tend to be more positive toward students with physical disabilities than those with neurodevelopmental conditions like ASD, particularly when behavioral challenges are present (De Boer et al., 2011).

3.3 Instructional approaches and classroom management strategies

Effective inclusion of autistic learners depends not only on teacher attitudes and knowledge but also on concrete, evidence-based classroom practices. Research highlights instructional and behavioral frameworks that support autistic students in mainstream settings. Structured teaching most notably the TEACCH model uses predictable routines, visual schedules, and clearly defined work systems to reduce anxiety and improve task engagement (Mesibov et al., 2005).

Visual supports help clarify expectations and promote independence (Dettmer et al., 2000). Peer-mediated and collaborative teaching strategies both foster social interaction and distribute instructional delivery, enabling autistic and non-autistic students to support one another (Kamps et al., 1999). Differentiated instruction modifying content, process, and product based on individual profiles allows teachers to align tasks with each learner’s strengths and interests (Tomlinson, 2014).

On the classroom management side, proactive Positive Behavior Support (PBS) frameworks employ functional behavior assessment to identify triggers, then teach alternative skills while adapting the environment to prevent escalation (Horner et al., 2012). Establishing clear, consistent rules and routines combined with immediate, specific reinforcement creates a predictable context in which autistic learners can thrive (Simpson, 2005). Sensory-friendly adaptations further reduce overload and support self-regulation (Ashburner et al., 2008).

Embedding these approaches within mainstream classrooms requires ongoing coaching and collaboration between general and special educators, ensuring that strategies are tailored, monitored, and refined over time (Lindsay et al., 2014).

3.4 Neurodiversity and the social–rights model

In recent years, the neurodiversity paradigm has reframed autism not as a pathology to be cured but as a form of cognitive variation that enriches human diversity. Coined by sociologist Judy Singer and advanced by Damian Milton, Nick Walker, and autistic self-advocates in the #ActuallyAutistic movement, neurodiversity adopts a social–rights model: it locates barriers to participation in inaccessible environments and stigmatizing attitudes, rather than in the individual’s neurology.

Milton’s ‘double empathy problem’ challenges the assumption that social breakdowns in autism stem solely from autistic individuals; instead, it highlights reciprocal misunderstandings between autistic and non-autistic people (Milton, 2012). Walker (2014) emphasizes autism as an identity-first concept (‘autistic person’) that foregrounds difference over deficit and aligns with disability-justice principles. Under this framework, inclusive practice shifts from remediation of “impairments” to the co-creation of learning environments that honor varied communication styles, sensory needs, and forms of sociality.

Embedding a neurodiversity lens in teacher development can empower educators to:

• Recognize autistic strengths (e.g., pattern recognition, focused interests) alongside challenges.

• Co-design accommodations (sensory breaks, visual schedules) with learners and families.

• Advocate for systemic changes that reduce ableist norms in curriculum, assessment, and school culture.”

3.5 Teacher training and support

Effective professional development for inclusive education typically combines several key elements: theoretical knowledge about specific conditions like ASD, practical classroom strategies, and ongoing mentorship or support (Tager-Flusberg et al., 2018). However, many teacher training programs, particularly in mainstream education, provide limited coverage of special educational needs. In-service training opportunities are often sporadic and may not address the specific needs of autistic learners (Kurniawati et al., 2017, Sepadi, 2018).

Research highlights the importance of hands-on, practical training components. Educators report greater confidence when training includes opportunities to practice strategies in realistic settings and access to ongoing support from specialists (Lindsay et al., 2014). Collaborative models that pair mainstream teachers with special education experts have shown particular promise in improving inclusive practices.

4 Research methodology

4.1 Research design

This study employed a qualitative research approach, specifically utilizing a descriptive case study design to explore mainstream educators’ understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Tzaneen Circuit, Mopani West District. The qualitative paradigm was selected because it allows for a comprehensive and contextualized exploration of participants’ experiences, perceptions, and knowledge (Creswell, 2003). The descriptive case study method was particularly appropriate for this research, as it facilitated an in-depth examination of real-life phenomena within their natural settings, capturing the complexities and nuances of educators’ daily practices and the challenges they face in mainstream classrooms (Mouton and Muller, 1998). This approach is well-suited to situations where the boundaries between the phenomenon and its context are not clearly defined, as is often the case with the inclusion of learners with ASD in mainstream education (Cohen et al., 2009).

4.2 Sampling

A purposive sampling strategy (Creswell, 2003) was used to select participants who could provide rich, relevant insights into the research questions. Two mainstream primary schools in the Tzaneen Circuit were chosen based on three criteria: (1) enrollment of at least one learner diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), (2) representation of resource-constrained rural conditions, and (3) administrative support for participation (Creswell, 2003; Guest et al., 2006).

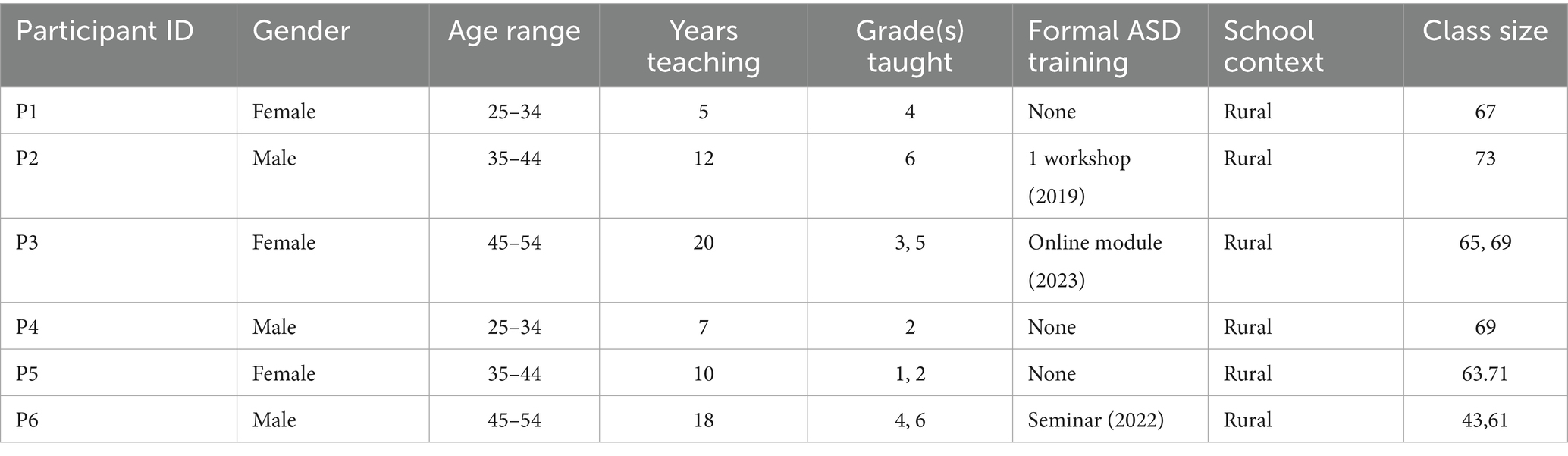

All participants were full-time educators in these schools, aged 25 to 54, with 5 to 20 years of teaching experience. Only three had received formal ASD training, highlighting a key gap in professional development. Class sizes ranged from 38 to 45 learners, reflecting typical resource limitations.

By focusing on educators with direct experience, the study captured authentic insights into both strengths and knowledge gaps regarding autism in mainstream settings. While a six-participant sample may seem small, purposive sampling prioritizes depth over breadth, seeking data saturation rather than generalizability (Creswell, 2003; Guest et al., 2006). In qualitative research, samples of 5–10 participants are often sufficient when examining context-bound phenomena with information-rich participants. In this study, thematic saturation was reached by the fourth interview, with subsequent interviews reinforcing and expanding emerging themes without introducing new categories (Cohen et al., 2009) (see Table 1).

4.3 Data collection

Data collection involved several qualitative methods to ensure depth, credibility, and triangulation of findings. The primary data collection tools included open-ended questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and document reviews. Initially, participants completed open-ended questionnaires designed to elicit their understanding of autism, familiarity with inclusive education policies, and perceptions of the challenges and support needs related to teaching learners with ASD. The responses from the questionnaires informed the development of the semi-structured interview guide, allowing for deeper probing and clarification of emerging themes during the individual interviews. Each interview was conducted in a private setting, recorded with the participants’ consent, and later transcribed verbatim to ensure accuracy and reliability.

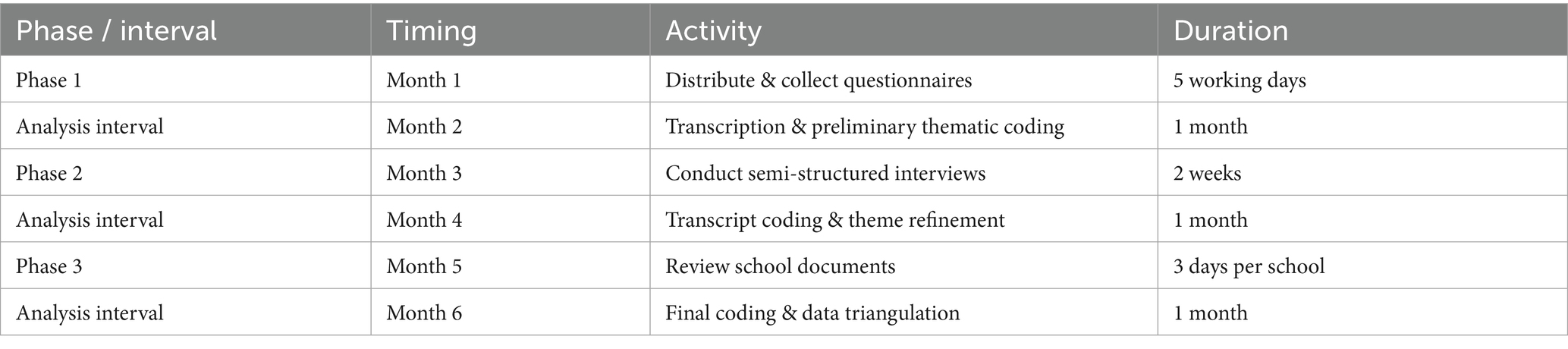

In addition to the questionnaires and interviews, a document review was conducted to provide contextual information and to corroborate or contrast the perspectives shared by the participants. Document analysis involved a three-day document review at each school of inclusive education policy manuals and SIAS circulars, professional-development records (attendance registers, slides, handouts), IEP templates and examples, differentiated lesson plans, ASD-specific aids and staff-meeting minutes; these materials were coded for policy enactment, resource provision, and support strategies. These documents provided valuable background information and helped situate the educators’ responses within the broader institutional and policy context (see Table 2).

Table 2. This staggered design ensured that insights from each phase informed subsequent data collection and that thorough analysis preceded the next phase.

4.4 Data analysis

Thematic content analysis was used to analyze the data collected from questionnaires, interviews, and document reviews (Creswell, 2021). Data were analyzed manually using Creswell’s five-step thematic content analysis framework (Creswell, 2003; Creswell and Poth, 2021). This systematic, iterative approach ensured that our themes were grounded in the data and reflected participants’ authentic perspectives.

1. Data organization and preparation. All interview transcripts, questionnaire responses, and document-review notes were collated, anonymized, and stored in a secure project folder. The lead researcher read through every text twice, adding margin notes to capture initial impressions and potential patterns.

2. Immersion and initial reading. Transcripts and notes were read holistically to develop a “sense of the whole.” During this phase, reflective memos were written to record emerging ideas about how educators described knowledge gaps, attitudes, and practices.

3. Coding and category development. A first-cycle, line-by-line coding process was conducted. Segments of text were assigned provisional codes (e.g., “training gaps,” “visual supports,” “policy disconnect”). As coding progressed, similar codes were grouped into broader categories, with code definitions refined through repeated comparison across data sources.

4. Theme identification and refinement. Categories were clustered into overarching themes that addressed the research questions. Each theme was defined, its boundaries clarified, and representative quotations selected. This phase included constant comparison, revisiting raw data to ensure themes authentically captured participants’ voices.

5. Interpretation and reporting. Themes were situated within the social-justice and Transformative Activist Stance frameworks. Interpretive memos linked each theme to existing literature and policy debates. The final write-up presents themes as directly as possible, supported by verbatim excerpts and cross-referenced with document-review findings.

To bolster trustworthiness, the researcher maintained an audit trail of coding decisions and reflective memos. Member checking was conducted by sharing theme summaries with two participants for confirmation and clarification. Triangulation across questionnaires, interviews, and documents further enhanced credibility and depth of analysis (Hytten and Bettez, 2011; Stetsenko, 2017a, 2017b). This rigorous approach to data analysis ensured that the findings were grounded in the data and reflective of the participants’ authentic experiences.

4.5 Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were rigorously addressed throughout the research process. Ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Limpopo’s Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC), and permission to conduct the study was secured from the circuit manager and the principals of the participating schools. Participants were fully informed about the purpose, benefits, and potential risks of the study, and written consent was obtained prior to their involvement. Anonymity and confidentiality were strictly maintained by using pseudonyms for both schools and participants, and no personal identifiers were collected or reported. Participation was entirely voluntary, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without consequence. All data, including recordings and transcripts, were securely stored and were accessible only to the researcher and supervisor. Upon completion of the study, these materials were scheduled to be destroyed to further protect participant confidentiality.

4.6 Trustworthiness of the study

To ensure the trustworthiness of the study, several strategies were implemented. Credibility was enhanced through the triangulation of data sources and methods, as well as through member checking, where participants were allowed to review and confirm the accuracy of their interview transcripts (Cohen et al., 2009). Transferability was supported by providing detailed descriptions of the research context and participants, allowing readers to assess the applicability of the findings to other settings. Dependability was ensured by maintaining a clear audit trail of research decisions and processes, while confirmability was addressed through reflexivity, with the researcher actively reflecting on and minimizing personal biases throughout the study (Creswell, 2003). These measures collectively contributed to the rigor and reliability of the research findings.

4.7 Limitations of the study

• Small, purposive sample. The study’s six participants were selected for in-depth insight rather than statistical representativeness. While thematic saturation was reached, findings may not generalize to all mainstream teachers or circuits.

• Single stakeholder perspective. Only teachers’ voices were included. The absence of parent, learner, and community perspectives limits understanding of how broader school-home dynamics affect inclusion.

• Context specificity. Conducted in two rural schools within the Tzaneen Circuit, the results reflect that particular resource-constrained setting. Urban or peri-urban contexts may exhibit different challenges and practices.

• Manual coding by one researcher. All data were coded iteratively by the lead researcher. Although member checking and an audit trail bolstered credibility, no formal intercoder reliability statistic was calculated.

• Reliance on self-reported data. Educators’ questionnaires and interviews may be subject to social desirability or recall bias. Observational or quantitative measures could complement these findings in future studies.

These limitations highlight opportunities for broader, multi-stakeholder research—incorporating parents, learners, and specialist practitioners—to deepen and extend understanding of inclusive practices for autistic students.

5 Findings

This section presents the findings of the study on mainstream educators’ understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Tzaneen Circuit, Mopani West District. The results are organized around the main themes that emerged from the thematic content analysis of the open-ended questionnaires and semi-structured interviews. Verbatim quotes from participants are used to illustrate their perspectives and provide authentic insights into their experiences and attitudes.

5.1 Theme 1: educators’ knowledge and awareness of autism

The findings reveal that mainstream educators possess varying levels of knowledge about autism, with most participants expressing only a basic understanding of the condition. Several educators admitted that their knowledge was limited to general characteristics, such as difficulties in communication and social interaction. One participant stated, “I have heard about autism, but I am not sure what causes it or how exactly it affects children in the classroom. I just know that some children struggle to talk or play with others” (Participant 2, School A). Another educator echoed this uncertainty, saying, “We were never really taught about autism in our training. Most of what I know comes from what I see on television or read online” (Participant 1, School B).

Despite this limited knowledge, some educators demonstrated a willingness to learn more about ASD. For example, one participant shared, “I try to read up on autism when I have a learner who is diagnosed, but there is not enough information or support from the department” (Participant 3, School A). This indicates a gap in formal training and professional development opportunities related to autism, which several participants identified as a significant barrier to effective inclusion.

5.2 Theme 2: attitudes toward inclusion of learners with ASD

The attitudes of mainstream educators toward the inclusion of learners with ASD were generally positive, but often tempered by feelings of inadequacy and concern about their own preparedness. One participant remarked, “I believe every child deserves a chance to learn in a normal school, but sometimes I feel lost because I do not know how to help them properly” (Participant 2, School B). Another educator expressed both hope and frustration: “Inclusion is a good idea, but we are not equipped. Sometimes I feel like I am failing these children because I do not have the skills” (Participant 1, School A).

Some educators also highlighted the challenges of balancing the needs of autistic learners with those of the rest of the class. As one participant put it, “It’s very difficult to give enough attention to a learner with autism when you have forty other children who also need help. Sometimes the other learners complain that I am spending too much time with one child” (Participant 3, School B). This sentiment was echoed by another educator, who noted, “I want to help, but I am stretched thin. It’s not fair to the autistic child or the others if I cannot give everyone what they need” (Participant 2, School A).

5.3 Theme 3: challenges in supporting learners with autism

A recurring theme in the findings was the lack of resources, training, and institutional support for mainstream educators. Many participants described feeling overwhelmed by the demands of inclusive education. One educator candidly admitted, “I feel helpless sometimes. There are no special materials or assistants in our school. We just do the best we can with what we have” (Participant 1, School B). Another participant elaborated, “We need workshops or training specifically on autism. Right now, we are just guessing and hoping for the best” (Participant 3, School A).

The lack of collaboration with specialists was also identified as a challenge. One participant explained, “If there was someone who could come and show us practical ways to support these learners, it would make a big difference. We do not have therapists or special educators to guide us” (Participant 3, School B). This highlights the need for ongoing professional development and access to expert support within mainstream schools.

5.4 Theme 4: strategies and coping mechanisms

Despite the challenges, some educators reported developing their own strategies to support learners with ASD. These included using visual aids, breaking tasks into smaller steps, and providing additional time for certain activities. One educator shared, “I use pictures and simple instructions to help the learner understand what to do. It takes more time, but it helps” (Participant 1, School A). Another described the importance of patience and flexibility: “You have to be patient and not get frustrated. Sometimes you have to change your approach if something does not work” (Participant 3, School B).

However, these strategies were often developed through trial and error rather than formal training. As one participant noted, “Most of what I do is just from experience. I try different things until I find something that works for the child” (Participant 2, School A). This underscores the need for structured guidance and evidence-based practices to support both educators and learners.

5.5 Theme 5: impact on teaching and learning

The presence of learners with ASD in mainstream classrooms was reported to have a significant impact on teaching and learning. Educators described both positive and negative effects. On the positive side, one participant observed, “Having an autistic learner in my class has made me more aware of different learning needs. It has taught me to be more creative and understanding” (Participant 1, School B). On the other hand, the added demands sometimes led to stress and burnout. As one educator confessed, “It can be very stressful. Sometimes I go home feeling like I did not do enough for any of my learners” (Participant 3, School A).

In summary, the findings indicate that while mainstream educators in the Tzaneen Circuit are generally supportive of inclusive education, their understanding of autism is limited and largely self-taught. The lack of formal training, resources, and specialist support poses significant challenges to effective inclusion. Nevertheless, educators demonstrate resilience and a willingness to adapt, developing their own strategies to support learners with ASD. The voices of participants highlight both the potential and the limitations of current inclusive practices, underscoring the urgent need for targeted professional development and systemic support.

6 Discussion

This section interprets and contextualizes the findings of the study on mainstream educators’ understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Tzaneen Circuit, Mopani West District. The discussion draws on the verbatim insights of participants, existing literature, and the theoretical framework of social justice and the Transformative Activist Stance (TAS) to illuminate the implications for inclusive education practice and policy in South Africa.

6.1 Introduction

This chapter interprets and contextualizes the findings of the study on mainstream educators’ understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Tzaneen Circuit, Mopani West District. The discussion draws on the verbatim insights of participants, existing literature, and the theoretical framework of social justice and the Transformative Activist Stance (TAS) to illuminate the implications for inclusive education practice and policy in South Africa.

6.2 Educators’ knowledge and awareness of autism

The study revealed that mainstream educators possess only basic and often fragmented knowledge about autism, with most relying on informal sources such as media or self-directed research rather than formal training. This aligns with prior research indicating that mainstream teachers in South Africa and globally often lack comprehensive training on ASD, particularly compared to their counterparts in special education settings (Gomez-Mari et al., 2021). The participants’ own words “I have heard about autism, but I am not sure what causes it or how exactly it affects children in the classroom” and “We were never really taught about autism in our training,” highlight a systemic gap in teacher education and ongoing professional development.

This limited knowledge has direct implications for the identification and support of autistic learners. As noted in the literature, a solid understanding of ASD is essential for educators to create supportive learning environments and adapt teaching strategies effectively (Gomez-Mari et al., 2021). The willingness of some educators to “try to read up on autism” reflects a positive attitude and openness to learning, but also underscores the lack of structured, accessible resources and support from the education department (Sepadi, 2023).

6.3 Attitudes toward inclusion and preparedness

While participants generally expressed positive attitudes toward the inclusion of learners with ASD “I believe every child deserves a chance to learn in a normal school” these attitudes were tempered by feelings of inadequacy and concern about their preparedness: “Sometimes I feel lost because I do not know how to help them properly.” This finding is consistent with the literature, which shows that teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion are influenced by their confidence and perceived competence (Russell et al., 2022). When educators lack training and support, even positive intentions can give way to frustration and self-doubt.

The challenge of balancing the needs of autistic learners with those of the rest of the class “It’s very difficult to give enough attention to a learner with autism when you have forty other children who also need help” speaks to the reality of large class sizes and limited resources in South African mainstream schools. This echoes findings by De Boer et al. (2011) and Rae et al. (2010), who noted that educators often feel less equipped to include students with complex or less visible disabilities.

6.4 Barriers: training, resources, and institutional support

A recurring theme was the lack of training, resources, and institutional support. Participants described feeling “helpless” and “overwhelmed,” with one stating, “There are no special materials or assistants in our school. We just do the best we can with what we have.” This is corroborated by Lindsay et al. (2014), who found that access to in-service training, teaching materials, and specialist support is critical to successful inclusion.

The absence of collaboration with specialists, “We do not have therapists or special educators to guide us,” further compounds the challenge. The literature emphasizes the importance of multi-disciplinary support and ongoing teacher development (Newton et al., 2014; Hart and Malian, 2013). Without these, mainstream educators are left to rely on “trial and error,” as one participant described, which can lead to inconsistent and sometimes ineffective support for autistic learners.

6.5 Coping strategies and teacher agency

The inclusion of learners with ASD in mainstream classrooms impacts both teaching and learning. Some educators reported positive effects, such as increased awareness of diverse learning needs and greater creativity in lesson planning: “Having an autistic learner in my class has made me more aware of different learning needs. It has taught me to be more creative and understanding.” This aligns with the social justice framework, which advocates for the recognition and accommodation of all learners’ rights and needs (Hytten and Bettez, 2011).

Conversely, the added demands of inclusion sometimes led to stress and feelings of inadequacy: “It can be very stressful. Sometimes I go home feeling like I did not do enough for any of my learners.” This underscores the need for systemic support to prevent teacher burnout and ensure that inclusion benefits all students, not just those with ASD.

The findings affirm the relevance of social justice and the Transformative Activist Stance as theoretical frameworks for understanding and advancing inclusive education. The educators’ struggles and adaptive efforts reflect the broader systemic inequities in South African education, particularly regarding access to training and resources. By foregrounding the lived experiences and voices of teachers, this study highlights the need for policies and practices that empower educators as agents of change, rather than passive recipients of top-down mandates (Stetsenko, 2017a, 2017b; Vianna and Stetsenko, 2019).

The discussion reveals that while mainstream educators in the Tzaneen Circuit are committed to the principles of inclusion, their effectiveness is hampered by limited knowledge, inadequate training, and insufficient institutional support. Their willingness to adapt and learn is commendable but unsustainable without systemic change. Addressing these gaps through targeted professional development, resource allocation, and multi-disciplinary collaboration is essential for realizing the goals of inclusive education and social justice for learners with ASD in South Africa.

6.6 Implications of the study

The insights generated by this study carry important implications for teacher education, policy implementation, and collaborative practice in resource-constrained settings. First, teacher preparation programs must incorporate robust, applied ASD modules integrating biomedical and neurodiversity perspectives to equip mainstream educators with both conceptual understanding and practical strategies. Second, education authorities should strengthen accountability mechanisms to ensure that inclusive-education policies such as White Paper 6 and SIAS are translated into concrete supports at the circuit and school levels, including dedicated funding for itinerant specialists and ASD-specific learning materials. Third, fostering professional learning communities and peer-mentoring networks can alleviate teachers’ sense of isolation, promote shared problem-solving, and accelerate the adoption of evidence-based instructional and behavioral approaches. Finally, ongoing research and evaluation ideally incorporating multiple stakeholders (parents, learners, and specialists) and mixed-methods designs are needed to validate self-reported practices, measure impacts on learner outcomes, and refine interventions in diverse rural contexts.

7 Recommendations

Based on the findings and discussion of this study, several recommendations are proposed to address the gaps identified in mainstream educators’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Tzaneen Circuit, Mopani West District. These recommendations are aligned with the principles of social justice and the transformative activist stance, aiming to promote inclusive, equitable, and effective education for learners with autism.

7.1 Enhance pre-service and in-service teacher training on autism

The study found that most mainstream educators have limited and often informal knowledge of autism, primarily due to insufficient exposure to ASD in their initial teacher training and a lack of ongoing professional development opportunities. It is therefore recommended that both pre-service and in-service teacher education programs integrate comprehensive modules on ASD and inclusive education. These modules should cover the characteristics of autism, evidence-based teaching strategies, classroom management techniques, and ways to foster social and academic development for autistic learners. Furthermore, regular workshops, seminars, and refresher courses should be organized at the circuit and district levels, ensuring that all educators remain up-to-date with current research and best practices.

7.2 Provide access to specialist support and resources

A recurring challenge highlighted by participants was the absence of specialist support, such as therapists, special educators, or inclusion facilitators, within mainstream schools. To address this, the Department of Education should allocate resources for the appointment of itinerant specialists who can provide direct support to both educators and learners. Schools should also be equipped with appropriate teaching and learning materials tailored for autistic students, including visual aids, communication tools, and sensory resources. Establishing partnerships with local NGOs, universities, and autism advocacy groups can further expand the pool of expertise and support available to schools.

7.3 Foster collaborative professional communities

Given the sense of isolation and trial-and-error approach reported by educators, it is recommended that schools and districts create professional learning communities (PLCs) focused on inclusive education and autism. These communities should provide a safe space for educators to share experiences, discuss challenges, and collaboratively develop solutions. Peer mentoring, lesson study, and collaborative planning sessions can help mainstream educators learn from one another and from colleagues with more experience or specialized training in ASD. Such collaborative efforts will promote a culture of shared responsibility and continuous improvement.

7.4 Strengthen policy implementation and monitoring

While South Africa’s inclusive education policies are progressive, the study found gaps in their practical implementation at the school level. School leadership, circuit managers, and district officials should receive targeted training on the practical aspects of policy implementation, monitoring, and support for inclusion. Clear guidelines and accountability mechanisms should be established to ensure that schools adhere to inclusive practices, provide reasonable accommodations, and regularly assess the effectiveness of interventions for autistic learners. Ongoing monitoring and evaluation will help identify areas for improvement and ensure that policy intentions translate into meaningful classroom change.

Implementing these recommendations will require coordinated efforts from policymakers, education authorities, school leaders, teachers, families, and the community. By addressing the gaps identified in this study, the education system can move closer to realizing the vision of inclusive, equitable, and high-quality education for all learners, including those with autism.

8 Conclusion

This study set out to explore mainstream educators’ understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the Tzaneen Circuit, Mopani West District, Limpopo Province. The research was motivated by the increasing enrolment of autistic learners in mainstream schools and the critical role that educators’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices play in ensuring effective and equitable inclusion. Using a qualitative, descriptive case study approach, the study provided in-depth insights into how educators perceive, experience, and respond to the challenges of teaching autistic learners in mainstream classrooms.

The findings reveal that while mainstream educators generally hold positive attitudes toward the inclusion of learners with ASD, their knowledge of autism is often limited and largely self-taught. Many educators reported that their initial teacher training did not adequately prepare them to support autistic learners, and ongoing professional development opportunities in this area remain scarce. As a result, educators frequently rely on informal sources of information and their own trial-and-error strategies to address the needs of autistic students. This lack of structured knowledge and guidance not only undermines their confidence but also impacts the quality of support provided to learners with ASD.

Despite these challenges, the study also found that educators are resilient and resourceful, demonstrating a willingness to adapt their teaching methods and seek out new strategies to support autistic learners. However, their efforts are often hampered by systemic barriers, including large class sizes, insufficient resources, and a lack of access to specialist support. These barriers contribute to feelings of frustration, stress, and, at times, inadequacy among educators, who are committed to inclusive education but feel constrained by the realities of their working environment.

The discussion of the findings, grounded in the frameworks of social justice and the Transformative Activist Stance, highlights the importance of empowering educators through comprehensive training, collaborative professional communities, and robust institutional support. The study underscores that inclusion is not merely a policy directive but a dynamic, ongoing process that requires investment in teacher development, resource allocation, and multi-disciplinary collaboration.

In light of these insights, the study recommends a multi-faceted approach to strengthening inclusive education for autistic learners. This includes enhancing both pre-service and in-service teacher training on ASD, providing access to specialist support and resources, fostering collaborative professional communities, and ensuring effective policy implementation and monitoring.

In conclusion, this research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on inclusive education in South Africa by foregrounding the lived experiences and voices of mainstream educators. It calls for urgent action from policymakers, education authorities, and school leaders to address the gaps identified and to create enabling environments where all learners, regardless of ability, can thrive. By investing in the capacity and wellbeing of educators, the education system can move closer to realizing its vision of equitable, high-quality education for every child including those with autism.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Limpopo’s Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MS: Project administration, Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Data curation, Software, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Gen AI was used to format references and editing of language for readability.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th Edn. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Ashburner, J., Ziviani, J., and Rodger, S. (2008). Sensory processing and classroom emotional, behavioral, and educational outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 62, 564–573. doi: 10.5014/ajot.62.5.564

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2009). Research methods in education. 6th Edn. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2021). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2021). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson.

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., and Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary school teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 15, 331–353. doi: 10.1080/13603110903030089

Department of Basic Education. (2014). Policy on screening, identification, assessment and support. Government Printer.

Department of Education. (2001). Education White Paper 6: Special needs education – Building an inclusive education and training system. Government Printer.

Dettmer, S., Simpson, R. L., Myles, B. S., and Ganz, J. B. (2000). The use of visual supports to facilitate transitions of students with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 15, 163–169. doi: 10.1177/108835760001500302

Gomez-Mari, I., Sanz-Cervera, P., and Tarraga-Minguez, R. (2021). Knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes of mainstream teachers toward students with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1–15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031196

Gómez-Marí, I., Sanz-Cervera, P., and Tárraga-Mínguez, R. (2021). Teachers' knowledge regarding autism spectrum disorder (ASD): a systematic review. Sustainability 13:5097. doi: 10.3390/su13095097

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Hart, J. E., and Malian, I. (2013). A statewide survey of general education teachers’ perceptions of their preparation for inclusive education. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 36, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/0888406412473311

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., and Lewis, T. J. (2012). Response to intervention and positive behavior support: how far have we traveled and where are we going? Sch. Psychol. Rev. 41, 1–18. doi: 10.17161/foec.v42i8.6906

Hytten, K., and Bettez, S. C. (2011). Understanding education for social justice. Educ. Found. 25, 7–24. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ931383

Kamps, D., Barbetta, P. M., Leonard, B. R., and Delquadri, J. (1999). Classwide peer tutoring: an integration strategy to improve reading skills and promote peer interactions among students with autism. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 32, 173–184. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-173

Kurniawati, F., De Boer, A. A., Minnaert, A. E. M. G., and Mangunsong, F. (2017). Evaluating the effect of a teacher training programme on the primary teachers’ attitudes, knowledge, and teaching strategies regarding special educational needs. Educ. Psychol. 37, 287–297. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2016.1176125

Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Scott, H., and Thomson, N. (2014). Exploring teachers’ strategies for including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 18, 101–122. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.758320

Lindsay, S., Proulx, M., Thomson, N., and Scott, H. (2014). Educators’ challenges of including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 61, 107–124. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2014.905057

Mesibov, G. B., Shea, V., and Schopler, E. (2005). The TEACCH approach to autism spectrum disorders. New York: Springer.

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the “double empathy problem.”. Disabil. Soc. 27, 883–887. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Mouton, J., and Muller, J. (1998). “Theory, metatheory and methodology in educational research” in Changing curriculum: Studies on outcomes-based education in South Africa. ed. J. Jansen (Cape Town, South Africa: Juta), 9–36.

Newton, N., Hunter-Johnson, Y., Gardiner-Farquharson, K., and Cambridge, J. (2014). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: a review of the literature. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 18, 1–17.

Rae, T., McCarthy, J., and Powell, S. (2010). Perspectives on inclusion: students with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 37, 204–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8578.2010.00482.x

Roberts, J., and Simpson, K. (2016). A review of research into stakeholder perspectives on inclusion of students with autism in mainstream schools. Int. J. Inclusive Educ. 20, 1084–1096. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1145267

Russell, M., Scrinery, J., and Smyth, F. (2022). Teacher attitudes and knowledge about inclusive education: a systematic review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 523–540. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1691263

Sepadi, M. D. (2018) “Student teachers' preparation for inclusive education: The case of the University of Limpopo” (Doctoral dissertation).

Sepadi, M. D. (2023). Investigating the content knowledge in teachers’ continuous professional development programmes for the implementation of inclusive education in Limpopo Province (Doctoral dissertation, University of Limpopo, Mankweng, South Africa)

Sepadi, M. D., and Themane, M. J. (2025). Creating capacity for change through short learning programmes for professional learning for inclusive education of teachers in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Educ. 45, 1–8. doi: 10.15700/saje.v45n1a2399

Simpson, R. L. (2005). Evidence-based practices and students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 20, 140–149. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200030201

Stetsenko, A. (2017a). Putting the radical notion of equality in the service of disrupting inequality in education. Rev. Res. Educ. 41, 112–135. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16687524

Stetsenko, A. (2017b). The transformative mind: Expanding Vygotsky’s approach to development and education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Tager-Flusberg, H., Rogers, S., Cooper, J., Landa, R., Lord, C., Paul, R., et al. (2018). Best practices in teaching students with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Autism Res. 11, 818–833. doi: 10.1002/aur.1936

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. 2nd Edn. Alexandria, Virginia: ASCD.

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. World Conference on Special Needs Education, Salamanca, Spain. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Treaty Series, 2515, 3. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

Vianna, E., and Stetsenko, A. (2019). Connecting learning and development with transformative activist stance: expanding Vygotsky’s project. Cultural-Historical Psychology 15, 326–335. doi: 10.17759/chp.2019150311

Walton, E. (2017a). “Inclusive education and teacher education: a foundation for a just, equitable and quality education for all” in Teacher education for inclusive teaching and learning. eds. E. Walton and S. Moonsamy (Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik), 13–28.

Walton, E. (2017b). Inclusive education in initial teacher education in South Africa: practical or professional knowledge? J. Educ. 67, 101–128.

Walker, N. (2014). Neurodiversity: Some basic terms & definitions. Neurocosmopolitanism. Available at: https://neurocosmopolitanism.com/neurodiversity-some-basic-terms-definitions/

World Health Organization (2022). Autism. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), inclusive education, mainstream educators, teacher training, South Africa, policy implementation

Citation: Sepadi M (2025) Inclusive education in resource-constrained settings: exploring mainstream teachers’ curriculum knowledge and practices for autistic learners in South Africa. Front. Educ. 10:1641336. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1641336

Edited by:

Weifeng Han, Flinders University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Doris Adams Hill, Auburn University College of Education, United StatesM. Isabel Vidal-Esteve, University of Valencia, Spain

Pamela Buhere, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, Kenya

Copyright © 2025 Sepadi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Medwin Sepadi, bWVkd2luLnNlcGFkaUB1bC5hYy56YQ==

Medwin Sepadi

Medwin Sepadi