- Faculty of English Studies, Phenikaa University, Hanoi, Vietnam

Introduction: This study examines the mediating factors that shape student agency in a Confucian Heritage Culture (CHC) context during ongoing education reform in Vietnam. While reforms emphasize student voice and participation, cultural traditions and academic pressures may limit agency in practice.

Methods: Grounded in a qualitative case study design, the research drew on semi-structured interviews with six school leaders and open-ended survey responses from 59 secondary students across three types of schools. The adapted Agency of University Students (AUS) scale was used as a coding framework to identify enablers and constraints, with a particular focus on relational and participatory resources.

Results: Findings indicate that school-level reforms created opportunities for greater student participation. However, hierarchical norms, surveillance, and high-stakes academic expectations often constrained students' autonomy. Conversely, trust-based relationships, collaboration, and shared school missions emerged as significant enablers of agency.

Discussion: The results highlight the complex interplay between cultural values and institutional practices in shaping student agency. They suggest that meaningful reform in CHC settings requires not only structural changes in schools but also cultural adaptation to foster authentic student voice and autonomy.

1 Introduction

The twenty-first century has ushered in unprecedented social, technological, and economic changes. Today's students must navigate a world where knowledge becomes obsolete rapidly, where careers demand adaptability and creative problem-solving, and where global challenges—from climate change to digital ethics—require informed, engaged citizens (OECD, 2019). These shifts call for learners who are not merely compliant recipients of instruction, but active, self-directed participants in their own learning and in shaping their communities.

Against this backdrop, student agency has emerged as a global buzzword in educational policy and research. Far from being a passing trend, it reflects a fundamental rethinking of the learner's role: the capacity to set goals, make choices, take responsibility, and influence learning environments to achieve meaningful outcomes (Vaughn, 2018; OECD, 2019). Studies link strong agency to improved academic performance, social-emotional wellbeing, and lifelong learning dispositions (Hill, 2019; Rector-Aranda and Raider-Roth, 2015). Fostering and nurturing student agency, thus, is beneficial to both students and the education system (OECD, 2019).

Student agency is considered as a process and a product of students' learning endeavors. The facilitating factors for in the process for student agency are students' individual antecedents (e.g., self-efficacy, interest, goals, personality, competence beliefs), institutional antecedents (e.g., peers and relationships with teachers, teaching practices, instructional design), and societal elements (e.g., social expectations of career advancement, definition of success) (Stenalt and Lassesen, 2022). For instance, in a secondary school context, a student's confidence and self-efficacy may be fostered by supportive teachers, shaped by peer collaboration in class projects, and reinforced by strong societal expectations for academic achievement as a pathway to future career success. This layered interplay between individual, institutional, and societal influences creates a hierarchical context that strongly informs students' sense of agency.

The research gap is striking. Existing models of student agency—such as the Agency of University Students (AUS) framework (Jääskelä et al., 2021)—were designed for university settings and often assume cultural norms of individual autonomy that do not align neatly with CHC schooling. While much of the discourse and empirical evidence on agency has been developed in higher education contexts, secondary schooling plays a formative role in developing the dispositions and skills that underpin agency. Research on secondary schools is not absent; studies in the U.S. and other Western contexts have examined agency in relation to engagement, student voice, and standardized testing (Ferguson et al., 2015; Mitra, 2008; Toshalis and Nakkula, 2012). Yet, even where Asian cases are considered, the emphasis often remains on classroom participation or individual dispositions rather than on how relational and participatory resources (authority negotiation, peer dynamics, institutional rules) shape agency in CHC contexts (e.g., Korea/Finalnd comparisons of control-agency, Yoon, 2021; Korean HS L2-writing agency, Jang, 2022; Chinese/ HK student-voice constraints, Cheng, 2012). Moroeover, work in China highlights peer and motivational mechanisms but not the power-agency nexus inside exam-oriented systems (e.g., peer relationships ↔ engagement/achievement in junior highs), leaving unanswered how school-level relations enable or constrain adolescent agency under CHC hierarchies. Hence, specifying how power and participation operate in CHC secondary schools—through the perspectives of school leaders and students—addresses a substantive and policy-relevant gap. Without understanding how agency is enabled or constrained in this context, reforms risk remaining aspirational slogans, leaving students ill-prepared for the demands of the modern world. Hence, exploring the relationship between power and agency from the perspectives of school leaders and students is valuable, particularly in cultures characterized by pronounced power gaps.

Vietnam's 2018 General Education Program reform offers a timely opportunity to examine these issues. The reform seeks to shift from knowledge transmission to competency-based learning, granting more curricular autonomy to schools and promoting formative alongside summative assessment [Huynh, 2022; Ministry of Education and Training (MOET), 2018/2021]. In theory, these changes should empower student voice and choice. In practice, implementation has been uneven, and cultural and structural constraints persist (Nhật et al., 2023).

This study investigates how school leaders and students conceptualize and experience agency within this reform, using an adapted AUS framework focused on relational and participatory dimensions. Specifically, it addresses:

RQ1. How did school leaders and students in Vietnamese secondary schools conceptualize student agency during the 2018 curriculum reform?

RQ2. Which relational and participatory resources enable or constrain student agency?

RQ3. How do institutional practices (e.g., surveillance, assessment workload, ability grouping) mediate the enactment of student agency?

By situating these questions within a CHC secondary school context undergoing systemic change, this research contributes urgently needed empirical evidence to the global discourse on student agency, offering practical insights for culturally responsive reform design and leadership.

2 Literature review

2.1 Student agency

Student agency, a multi-dimensional concept, is broadly defined as students' active involvement in their learning, decision-making in their learning experiences, and control over their environment to achieve goals despite challenges (Czerniewicz et al., 2009; Klemenčič, 2015; Reeve, 2012; Vaughn, 2018). It covers constructs such as self-efficacy beliefs (Jackson, 2003; Zeiser et al., 2018), perseverance, mastery orientation, metacognitive self-regulation, self-regulated learning, and future orientation (Zeiser et al., 2018). However, it can manifest negatively in forms of maladaptive agency in certain situations, such as exam-driven cultures, where students may engage in undesirable behaviors not aligned with growth mindset principles (Nieminen and Tuohilampi, 2020; Vaughn et al., 2020). For example, a mixed-method study involving 135 senior high and first-year university students in Northern Vietnam found that the exam-oriented system left students with very little time to explore their life purpose, and identified a negative correlation between the intensity of the exam culture and students' ability to pursue meaningful personal or educational goals (Pham, 2021).

Student agency is also temporal and intertwined with identity formation, shaped by contextual factors, including social, cultural, and material elements (Nieminen and Tuohilampi, 2020; Trommsdorff, 2012). In CHC contexts where high-stake exams tend to take over, hierarchical classroom dynamics and rule-focused instruction may suppress agency for students to adapt to rote learning and limited autonomy. In contrast, a qualitative study of Vietnamese EFL teachers who completed British Council professional development reported a shift toward formative, dialogic assessment practices (e.g., informal games, peer feedback, observation-based adjustments), opening space for more student-centered, collaborative learning despite systemic exam pressure (Phuong et al., 2025). Further research highlights the influence of hierarchical relationships, teacher authority, and collective identity in shaping how students perceive and enact agency (Phuong-Mai et al., 2005). Understanding agency as context-dependent emphasizes the need to theorize where and how it can emerge within different learning environments—not to assume its presence by default.

This contrast between suppression and emergence of agency across different contexts also poses challenges for measurement, as traditional self-reports may overlook these situational differences. Traditional self-report surveys may not capture its full complexity including its situated and relational nature (Rector-Aranda and Raider-Roth, 2015; Matsumoto, 2021; Nieminen et al., 2022). The Agency of University Students (AUS) scale, developed by Jääskelä et al. (2021), offers a structured framework focusing on individual, relational, and participatory resources. It adopts a person-subject-centered approach, focusing on emotional experiences, cognitive processes, and actions within the educational context (Eteläpelto et al., 2013; Jääskelä et al., 2021). The scale serves as an analytics tool for students and teachers, enabling self-reflection, self-regulation, and pedagogical development. Given the relational emphasis in CHC schooling—where trust, respect, and teacher support are pivotal—the AUS's relational and participatory dimensions provide a useful analytical lens for investigating agency in Vietnamese secondary schools.

2.2 Vietnam's education and the 2018 reform

Vietnam's education history spans various reforms, from early Confucian dominance to French colonization and post-independence literacy drives. The twentieth century saw educational divergence between North and South, culminating in a unified 12-year system in 1975, later undergoing reforms under economic pressures in 1986 (Doi Moi). Recent years witnessed improved resources and teacher training, yet curriculum changes and parental involvement remain contentious (Huynh, 2022). The 2018 General Education Program (GEP) represented the most comprehensive shift in recent decades, moving from a knowledge-transmission model toward competency-based, student-centered learning (Ministry of Education and Training (MOET), 2018/2021). The reform emphasized education for competency, focusing on students' lifelong learning, career choices, moral development, and emotional wellbeing. It introduced interdisciplinary curriculum development, allowing more local authority over content and teaching approaches. Pedagogy emphasized “learning by doing,” and there was a shift from solely summative to formative assessment. Textbooks diversified, and teachers had a more active role in designing syllabi. The reform also increased students' responsibilities for applying their learning to real-life situations. Parents were encouraged to support students in practical knowledge application (Huynh, 2022).

In principle, these changes aligned with OECD (2019) conceptions of student agency, aiming to give learners more voice, choice, and responsibility in their education. The reform also encouraged teachers to co-design curricula and integrate “learning by doing” pedagogy. However, implementation challenges remained, including limited teacher training, entrenched exam-oriented practices, large class sizes, and inconsistent resource distribution across regions (Nhật et al., 2023).

In CHC systems such as Vietnam's, cultural and institutional legacies can create tensions in reform enactment. Studies show that while policies grant teachers autonomy, actual classroom practices often remain teacher-directed, with surveillance and ability grouping reinforcing hierarchical norms (Berry, 2011; Huynh, 2022; Nhật et al., 2023). These dynamics affect the degree to which students can exercise agency, even under a reform agenda that promotes it.

The 2018 reform thus presents a critical case for studying agency in CHC secondary schools: it is a moment of policy-level commitment to agency yet situated in a socio-cultural context where structural and cultural factors may mediate, dilute, or redirect its enactment. Understanding this mediation requires perspectives from both school leaders -who interpret and implement reform—and students—who experience and negotiate its outcomes

2.3 Cultural-structural mediation of student agency

While the 2018 GEP reform aligns in principle with international models of student agency, its enactment in Vietnamese secondary schools is mediated by a combination of cultural values and institutional structures characteristic of Confucian Heritage Culture (CHC) systems. In such contexts, agency is often “granted” or “permitted” by authority figures rather than assumed as an inherent right (Phuong-Mai et al., 2005).

Structural factors further shape these cultural tendencies. High-stakes examinations and ability grouping continue to dominate CHC classrooms, reinforcing compliance and performance orientation (Dello-Iacovo, 2009; Tan, 2017). Surveillance and accountability mechanisms—ranging from teacher-centered monitoring to policy-driven inspection regimes—have also been discussed as constraining student expression and emphasizing behavioral conformity (Simons and Masschelein, 2008).

Additionally, comparative research in post-socialist contexts offers insights: Erss's (2023) study of Estonian and Russian-speaking adolescents reveals how cultural and relational resources mediate student agency even under structural constraints.

In East Asian contexts, experiments with student-led pedagogical methods suggest that agency can still be fostered in Confucian-influenced systems. For instance, a study by Briffett-Aktaş et al. (2025) in Hong Kong shows that a Student-Led Pedagogical Method—branded as Student Voice for Social Justice (SVSJ)—can empower students and diversify classroom knowledge, even amid traditionally teacher-centered dynamics.

Understanding this cultural-structural mediation is essential for interpreting how relational and participatory resources operate in practice. It also underscores the importance of examining both leadership perspectives and student experiences, as these interactions reveal how reform policies are translated—or transformed—within the lived realities of CHC secondary schooling.

3 Methods

3.1 Research design and positionality

This study employed a qualitative case study design situated in an interpretivist paradigm to explore the mediating factors influencing student agency in a Confucian Heritage Culture (CHC) context. Case study methodology was selected because it enables in-depth, context-rich analysis of complex social phenomena (Yin, 2018).

As a Vietnamese national who was educated in the public school system from kindergarten through university and later taught in private schools from 2019 to 2021, the researcher occupies a dual position as both insider and partial outsider. This unique positionality provided both experiential knowledge and critical distance when examining Vietnam's 2018 curriculum reform and its implications for student agency. Reflexive memos were maintained throughout data collection and analysis to monitor positionality and potential bias (Tracy, 2010).

3.2 Participants

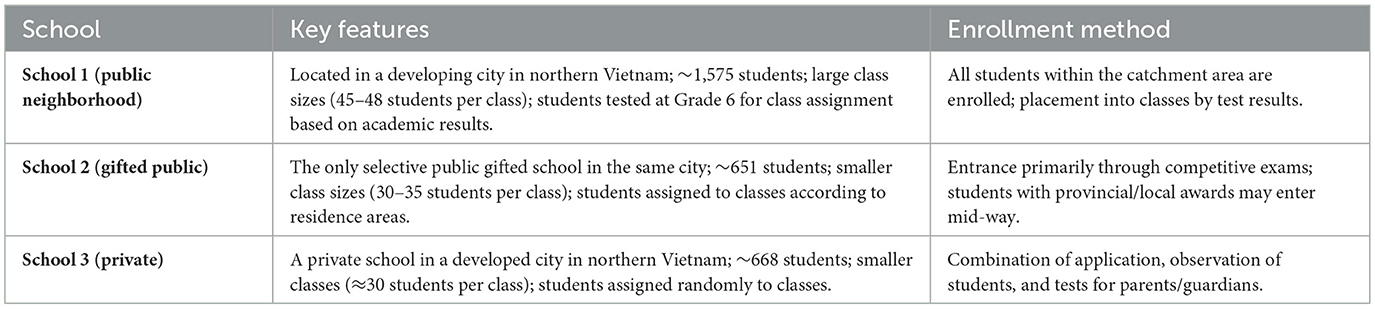

A purposive maximum-variation sampling strategy was used to ensure diversity (gender, academic competence, involvement in extracurricular activities) across institutional type (Patton, 2015). Data were collected in Vietnam from three secondary schools representing different institutional types: School 1—Public neighborhood school (large class sizes, traditional exam orientation), School 2—Gifted public school (selective admission, academic competition focus), School 3—Private school (smaller classes, progressive pedagogy). All schools had implemented the 2018 GEP and used Vietnamese as the primary language of instruction. Key contextual features—including assessment policies, surveillance practices (e.g., CCTV), and student governance structures—varied across sites, providing a basis for cross-case comparison.

In total, 9 school leaders, including school principals, vice-principals, and department heads (three for each school) were invited for the interviews and 6 of them agreed to be interviewed. The group of leaders thus included 3 principals and 3 head teachers, who would be numbered, respectively, as Principal 1, 2, 3 and Head teacher 1, 2, 3 for the three school types. This group was not exhaustive of all leaders in the schools but was chosen because of their direct involvement in implementing the 2018 reform and managing student learning policies. Over 2 months, 5 semi-structured interviews and 1 email response were collected for analysis. Leaders included principals and vice-principals responsible for school-wide policies and extra-curricular activities while head teachers overseeing three major academic subjects (Mathematics, Literature, English).

Fifty-nine students in grades 8 and 9 were recruited using stratified sampling to reflect variation in gender and achievement levels. The final sample achieved near balance between male and female participants, with several students opting not to disclose gender. Distribution across schools ensured diversity: in the public school, students came from classes representing different placement levels; in the gifted school, selection reflected both achievement and residential assignment; and in the private school, two classes were chosen where enrollment had been balanced for gender and academic variation. Parental consent and student assent were obtained prior to participation.

Table 1 summarizes participating schools by school type, role, demographic characteristics, and enrollment methods.

3.3 Instruments and data sources

Data were collected from two primary sources: semi-structured interviews with school leaders and open-ended surveys with students.

3.3.1 Semi-structured interviews

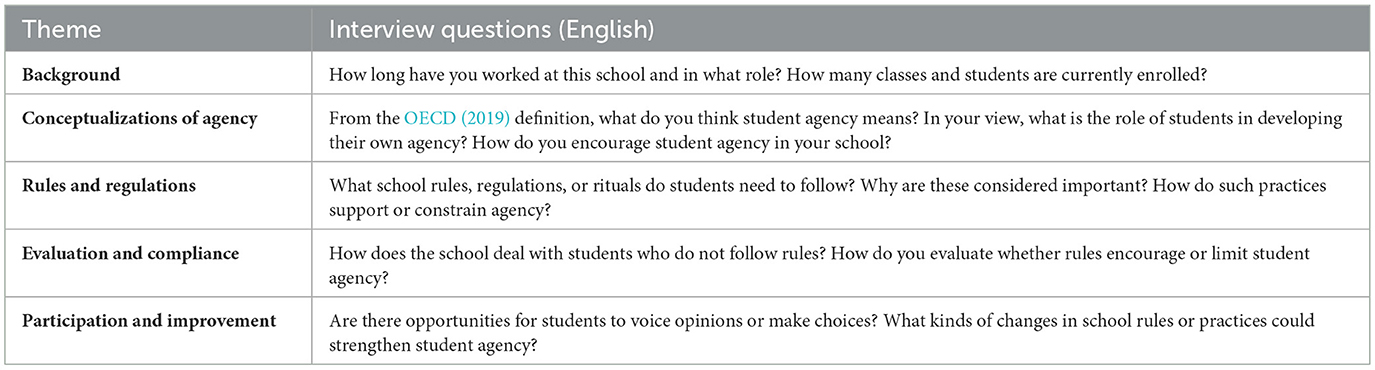

The interviews, conducted with five school leaders across three different secondary schools, lasted between 60 and 75 min. They were carried out in Vietnamese, audio-recorded with consent, transcribed verbatim, and later translated into English for analysis. The interview protocol was developed based on theoretical frameworks of student agency (OECD, 2019; Jääskelä et al., 2021) and included guiding questions about how leaders conceptualized agency, how rules and practices shaped students' autonomy, and what opportunities or constraints existed in their schools. The full interview protocol is provided in Table 2. One principal had to respond to the interview questions through email.

3.3.2 Open-ended student survey

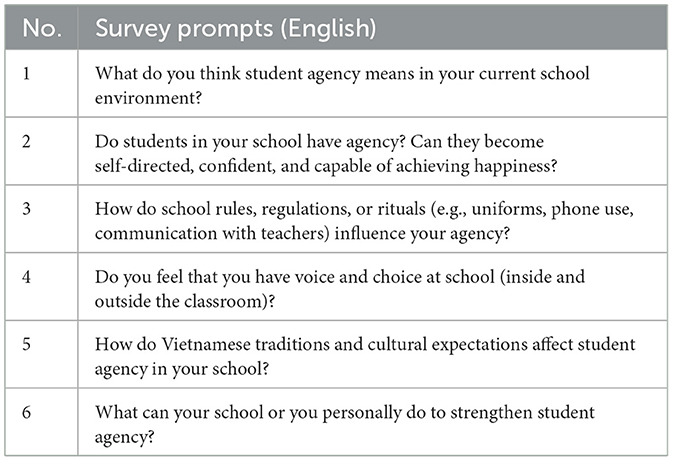

Fifty-nine students in grades 8 and 9 completed a qualitative survey. The main prompt asked students to reflect on student agency in their current school environment, using OECD's (2019) definition as a reference. Six guiding questions invited elaboration on whether students felt they had voice and choice, how school rules and cultural expectations supported or limited them, and what improvements could be made. Items were adapted from the dimensions of OECD's (2019) definition and the Agency of University Students (AUS) scale (Jääskelä et al., 2021) but reformulated into narrative prompts rather than Likert-type items to capture students' accounts in their own words. The survey was piloted with four students to ensure clarity and contextual appropriateness. Content and face validity were addressed through alignment with theoretical constructs and consultation with two secondary teachers for feedback. The full survey instrument can be found in Table 3.

Together, these two data sources provided complementary perspectives: interviews captured institutional views on student agency and its promotion, while student surveys revealed lived experiences and perceptions at the classroom level.

3.4 Data analysis

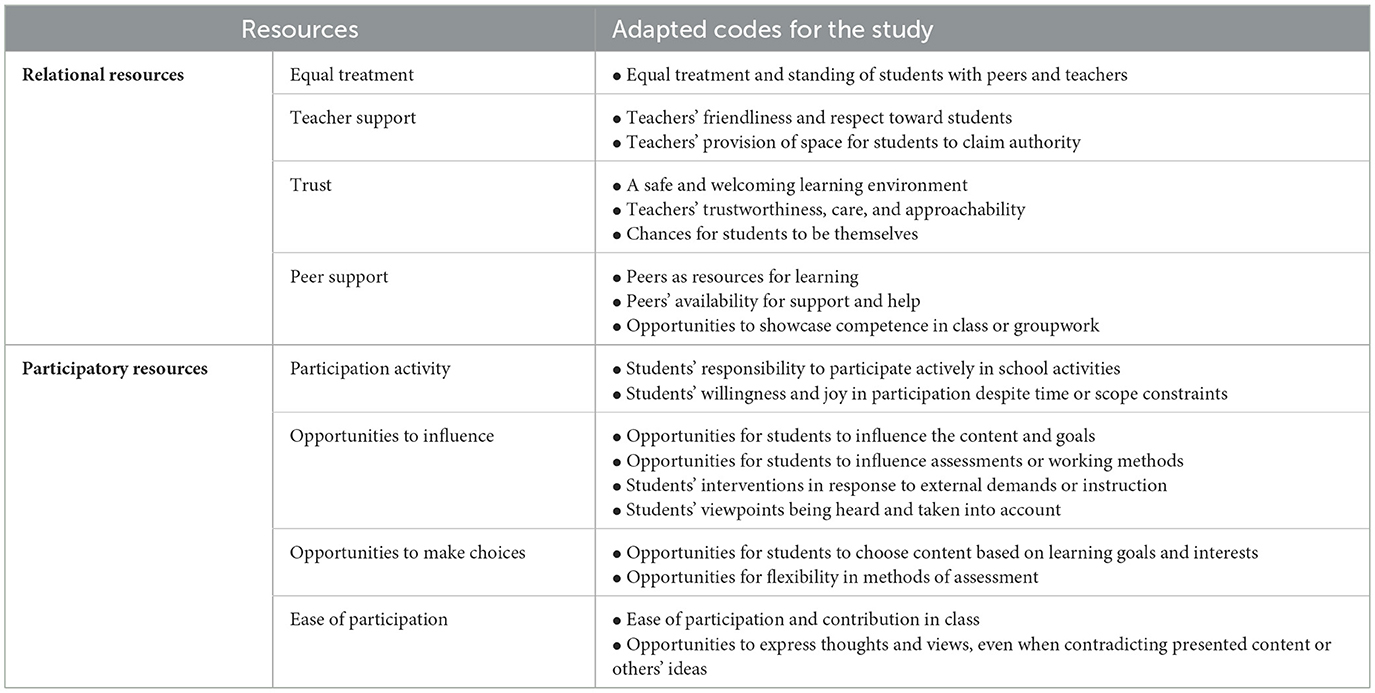

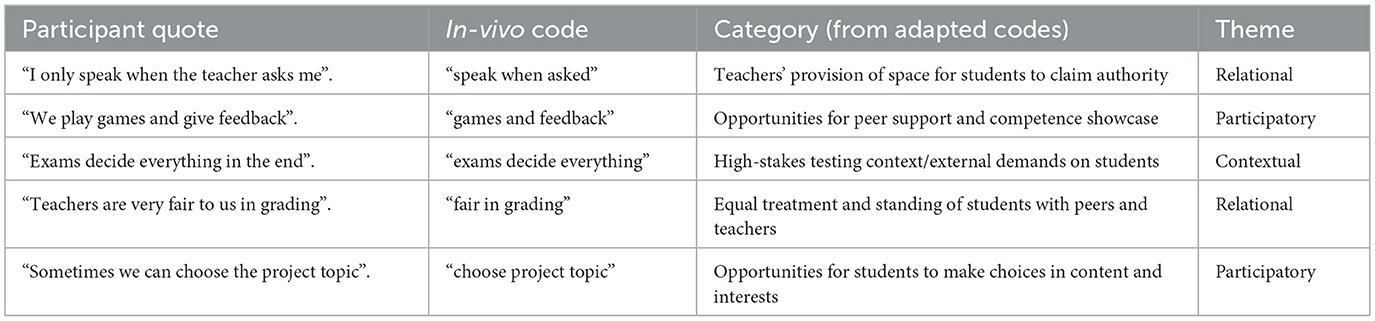

The original target of the Agency of University Students (AUS) scale (Jääskelä et al., 2021) was university students at the course level, so it was adapted for use in this study of Vietnamese secondary schools. The original questionnaire items were transformed into codes that then served as an analytic frame for qualitative data. The adaptation followed several steps. First, items representing individual resources (competence beliefs, self-efficacy beliefs, interest, and utility beliefs) were omitted, since the focus of Research Question 2 was on relational and participatory dimensions of agency. Second, all reverse-coded items were recast in a positive direction. Third, items that referred narrowly to course-level practices were reworded to capture the expansiveness of schooling experiences (e.g., the phrase “the course” was replaced with “school experiences” or “learning experiences”). Finally, in some cases multiple items were combined into a single code to avoid redundancy - for instance, items 1, 2, and 3 were merged into the adapted code “Students take responsibility to participate actively in school activities”. The resulting coding frame emphasized relational and participatory resources and is presented in Table 4.

This adapted frame then guided a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) conducted in three iterative cycles using MAXQDA software. All interview transcripts and student survey responses were anonymized before analysis. In the first cycle, in-vivo coding was applied line by line to capture participants' own words; for example, phrases such as “being confident to speak up” or “just following rules” were tagged as initial codes (RQ1). In the second cycle, these descriptive codes were reorganized through axial coding and aligned with the adapted categories in Table 4, such as “teachers' provision of space for students to claim authority,” “peer collaboration,” or “exam pressure” (RQ2 and RQ3). In the third cycle, matrix coding queries were conducted to compare how categories appeared across school types (public, private, gifted) and participant roles (students, school leaders). For instance, all codes relating to “voice” were cross-tabulated by school type to reveal convergences and divergences. To avoid over-reliance on software outputs, coded segments were manually cross-checked against the original transcripts and survey responses to ensure that the analysis reflected the substance of participants' accounts rather than researcher assumptions. Table 5 illustrates this analytic trajectory, showing how raw excerpts were developed into in-vivo codes, adapted categories, and overarching themes. Trustworthiness was established through multiple strategies: member checking with two school leaders and six students across different schools, negative case analysis to test emerging interpretations, and maintenance of an audit trail of coding decisions and analytic memos to ensure transparency and dependability.

3.5 Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional research committee. Informed consent was collected from all participants. For students under 16, both student assent and parental consent were required. A video explanation of the study was provided in classrooms. Data were anonymized, encrypted, and securely stored. All interviews were conducted ethically and respectfully, honoring participant autonomy, and relational ethics were prioritized to foster mutual trust.

4 Results

The findings are organized around the three research questions. Section 4.1 examines how school leaders and students conceptualized student agency across institutional contexts (RQ1). Section 4.2 investigates the relational and participatory resources that shaped how agency was enacted in practice (RQ2). Section 4.3 analyzes the institutional and contextual conditions that mediated students' opportunities to exercise agency (RQ3). Taken as a whole, the results provide a multi-layered account of how agency was understood, negotiated, and experienced in Vietnamese secondary schools under the 2018 reform.

4.1 Conceptualizations of student agency

Student agency was conceptualized in divergent ways across the three schools, reflecting not only institutional types but also the positionalities of teachers, principals, and students. While all participants acknowledged its significance, their interpretations varied from voice and confidence, to resilience and goal-setting, to disciplined compliance.

In the private school (School 3), leaders and teachers often described agency as openness and the courage to question authority. Head Teacher 3 explained, “Students today are confident and outspoken… they say whatever they think, but they lack the awareness of how to speak, to whom, and in what context. They need guidance to use this right properly”. This statement highlighted a double meaning: agency was seen as assertive voice, but also something that required careful regulation by teachers. Principal 3 similarly emphasized that students actively engaged with teachers, noting that “Students asked teachers so many things… commented on how a lesson should be taught… or shared how they wanted to learn”. For these leaders, student agency was both evidence of a cultural shift toward confidence and a phenomenon that needed to be managed to ensure appropriateness. Students in this context were not passive recipients of knowledge, but active interlocutors whose voices were invited and negotiated within relationships of trust.

In the gifted school (School 2), agency was conceptualized primarily through the lens of competition and academic perseverance. Teachers and leaders often defined agency as resilience under exam pressure and the ability to set personal goals within a highly competitive environment. Head Teacher 2 described this approach, stating, “Teachers in my school guide students in setting goals and reorienting after competitions”. Here, agency was tied directly to the capacity to withstand stress, to persist, and to maintain direction despite challenges. Principal 2 also articulated a strong disciplinary framing, emphasizing that students were granted “freedom within boundaries” and that rules were “reasonable and necessary for their moral training”. In her account, agency was not unbounded autonomy but a form of structured self-control that aligned with the school's emphasis on academic excellence and order. Student perspectives echoed this tension. While acknowledging that they had voices, many admitted to feeling silenced by peer conformity. One student explained, “Students all have voices, but they don't dare to speak against the majority”. These accounts suggest that even in a context where students were high-achieving and motivated, agency was circumscribed by competition, conformity, and the weight of expectations.

By contrast, in the public neighborhood school (School 1), agency was most often equated with compliance and discipline. Principal 1 explained that school regulations were part of students' everyday routines and “very reasonable for students to follow”. For her, agency was expressed not through voice or innovation but through fulfilling responsibilities and adhering to expectations. Students likewise described a climate of hesitation and fear. One confessed, “I rarely look teachers in the eyes. I feel afraid when doing so,” underscoring how hierarchical relationships diminished confidence. Other students explained that when they tried to express alternative viewpoints, their ideas were dismissed as “absurd” or “irrational”. These experiences suggested that many public school students did not see themselves as active agents but as subjects expected to comply and remain silent in order to avoid reprimand.

Across all three schools, participants emphasized that agency was not evenly distributed among students. Teachers frequently distinguished between high- and low-achieving groups, especially in the gifted school. Head Teacher 2 contrasted top groups, who were self-regulated and proactive, with weaker groups who struggled to complete even basic tasks. In the public school, only a few standout students were perceived as demonstrating initiative, while the majority remained passive. Students themselves echoed these perceptions, with one remarking that “only a few students have agency, the rest just follow the majority”. Such accounts highlight how access to agency was stratified, often reinforcing existing academic hierarchies.

Despite their differences, participants consistently regarded agency as important. For leaders in the private school, it was linked to confidence and leadership, essential for students' future growth. In the gifted school, it was tied to perseverance and resilience, necessary for navigating competition and achieving excellence. In the public school, it was framed as moral responsibility and order, ensuring that students adhered to rules and maintained discipline. Taken together, these findings reveal that while student agency was valued across contexts, its meaning was far from uniform. In the private school it was expressed as confident voice, in the gifted school as academic resilience, and in the public school as disciplined compliance. These contrasting conceptualizations underscore that agency was not a stable construct but one shaped by institutional ideologies and the social positioning of students within their schools.

4.2 Relational and participatory resources for student agency

To address RQ2, this section examines how relational and participatory resources shaped the enactment of student agency across schools. Relational resources—including families, trust, teacher support, and peer dynamics—defined the quality of everyday interactions, while participatory resources determined the opportunities students had to influence their learning and school life.

Families played a significant role in a student's schooling and upbringing. Head Teacher 3 stressed the importance of parents instilling basic values like respect and politeness in children from a young age. She also emphasized the crucial role of family in shielding children from negative influences, prioritizing early education over teachers' influence. This contrasts with Head Teacher 1's belief that the school plays a primary role in safeguarding students. Head Teacher 1's perspective may stem from experiences with parents who restrict student agency rather than fostering it. Student 5 (School 2) echoed this sentiment, noting the pressure from “Asian parents” solely focused on academic success.

Both Principals 1 and 3 had the belief that families needed to have a mutual understanding of the learning environment in which their children partook to collaborate and help them develop their agency holistically. During the school year, the school, parents and child would operate on a mutual agreement printed in a parent booklet signed prior to the start of the school. Without parents who could advocate for such causes, Principal 3 believed this school model would not succeed. Principal 1 emphasized the need for participation from parents through the possibility of school visits and channels for parents to give feedback to School 1, “The involvement of parents needs to start early, at kindergarten and primary school, middle school … Families have an influence on students' core values, which could enable or constrain students' personal resources such as their self-efficacy beliefs”.

While families set the initial foundation, students' sense of agency was also strongly shaped by the degree of trust embedded in school relationships. An environment of trust significantly impacted student agency, particularly highlighted in School 3 where trust between the principal, head teacher, and students was evident. This trust was attributed to the school's eight transparent core values, fostering an atmosphere where students felt comfortable expressing themselves without fear. Such trust led to a norm where student voices were heard and valued, enhancing their sense of control and agency in their learning. Students “asked teachers so many things… commented on how a lesson should be taught… or shared how they wanted to learn” (Principal 3). However, not all rules were unquestioned, with some students resisting practices they perceived as irrational.

In the gifted school (School 2), while students acknowledged trust with teachers, they faced trust issues with peers and the environment, often succumbing to peer pressure. Fear of social disparagement influenced students to prioritize maintaining their academic standing, leading to either perfectionism or conformity. A student claimed, “Students all have voices, but they don't dare to speak against the majority”.

In contrast, School 1's leaders exhibited lower trust in students, fearing potential chaos if students were given more control. Despite recognizing the need for greater trust and empathy, there remained reservations about students' ability to handle autonomy. Some students in school 1 also felt unheard and misunderstood, facing difficulties in expressing themselves freely, claiming that “I rarely look teachers in the eyes. I feel afraid when doing so”.

Some students found it hard to be heard for “being different” and for “having absurd ideas” that teachers disregarded. Some of them questioned schools' trust with them due to the 24/7 camera surveillance which they claim “violate their rights”. Head Teacher 1 also recognized this issue when she constantly found the need to reassure students of the trust teachers had for them; otherwise, students felt hesitant to chip in.

Nonetheless, even though she emphasized that the fear of teachers was “non-existent in my school”, she discussed incidents with her colleagues that she found lacking in trust and imposing. That being said, even though teachers in School 1 wanted to create a more democratic environment, tensions existed between teachers and students.

It is noteworthy, however, that teachers' trust was considered not just a resource but also an outcome of students' increased individual resources. According to Head Teacher 3, some students needed to earn the trust of teachers by performing academically and showing commitment to their learning more. In short, it appeared that trust was a commodity negotiated by both parties rather than a given from teachers. This suggests that trust operated simultaneously as both an enabling condition and a negotiated outcome, shaping how student agency could be enacted across different contexts.

Trust, however, was inseparable from how teachers encouraged or withheld support in students' daily learning. In congruence with trust, teacher support, including their friendliness toward students and encouragement, was coveted by students, especially in School 1 where students varied in academic competence and thus required different levels of support. This was seen as an issue by both students and school leaders of School 1 alike. Tensions existed among teachers creating a dilemma of whether to give students space or intervene among lower level classes. This was attributed to the remnants of teacher-centered teaching approaches.

A teacher from the private school (School 1) asserted that, “traditional ways of teaching work fine and some teachers don't want to take risks by giving students more voices and choices”. This suggests that trust operated simultaneously as both an enabling condition and a negotiated outcome, shaping how student agency could be enacted across different contexts.

Beyond teachers, peers also played a critical role in shaping whether students felt safe or reluctant to exercise voice.

Even though less discussed compared to other factors, peer support was mentioned as a necessity by a student in the gifted school (School 2) as she experienced a negative experience of dissidence among friends. This factor, interestingly, did not appeal to Head Teacher 3 as a resource. She considered peer support as “to have students teach each other”, which she believed “is very hard because the percentage of alpha leaders is small compared to the rest”.

Similar to trust, equal treatment was expected by all participants; however, school leaders and students also acknowledged the complexity of equality matters amidst a strong influence of hierarchy and academic competition.

Apart from social status, the treatment of students based off different academic statuses seemed to be a problem for discussion. A student in the private school (School 3) attributed the segregation of students into 3 competence levels to furthering parents' academic competition, which might tarnish students' interest, self-efficacy, and competence beliefs, and thus their agency. Another student further stressed that this rather acted as a benchmark for comparison and unequal treatment.

Taken together, relational resources such as family, trust, teacher support, peer dynamics, and perceptions of fairness emerged as decisive in enabling or constraining student agency. Their impact varied significantly by school, depending on whether trust was extended unconditionally, earned through performance, or undermined by surveillance and hierarchy.

If relational resources defined the conditions of interaction, participatory resources determined the concrete opportunities available for students to enact agency.

Enhanced participatory resources were called out by students as the most expected improvement in their educational institutes for the development of student agency.

Teachers needed to lift some barriers of hierarchy and academic stress to pave the way for participatory resources, especially opportunities for influence and choices. Giving students space to regulate their study and reflect seemed to be an uncommon practice in the public school (School 1), validated by 7 surveyed students. School Principal 1, nonetheless, accentuated her attempt to integrate more extracurricular activities for students without overplaying academic activities due to her school status as a “public school”. She planned to organize more clubs for students to join and host events themselves. Nonetheless, students in this school still expressed a strong desire for greater voice, either in the forms of “anonymous feedback” (Student 2), academic contests (Student 20), student-focused activities (Student 6), or simply “space for students to self-regulate and make decisions” (Student 3).

Heavy curriculum and assessment seemed to constrain students' opportunities to make decisions on what and how to learn. Knowledge-based education also snows students under “unnecessary stress” (Student 8, School 2). The high school exam, which was considered “more important than the university exam” (Head Teacher 1) further reinforced its status as a high-stake test, impeding students and teachers alike to participate and organize more events that catered to “individual needs”. One student got emotional by stating her unhappiness “due to overwhelming stress from studying and extra classes without any time for relaxation” and that “I hate the educational system. It's unlikely Vietnamese students can develop student agency because the system values grades the most” (Student 17, School 1).

These accounts illustrate that while students longed for opportunities to influence learning and school life, structural pressures of exams and curricula left little room for such participation, particularly in the public school.

In line with other factors, ease of participation and level of participation activity needed further focus as a way to degrade hierarchy and peer pressure to enable student agency.

Students in school 2 were also reported with a high level of competitiveness and goal-setting skills (Head Teacher 2). According to head teacher 2, teachers in her school would guide students in setting goals and reorienting after multi-level academic competitions. Students also had chances to learn about their interests in the school's extracurricular activities, which teachers tried to diversify and organize frequently. Head Teacher 2 also thought that students would like such collaborative, extracurricular events to be held more regularly, which aligns with the majority of students' expectations. However, students still noted barriers, reporting that they often felt “scared to participate” or “overloaded with homework and extra classes,” which made genuine participation inviable in both Schools 1 and 2.

By contrast, in the private school (School 3), students had abundant opportunities to participate in clubs and student-led events, and leaders emphasized that students frequently questioned teachers and shared ideas about how learning should take place. These opportunities reinforced students' sense of belonging and confidence, positioning participation as a core enabler of agency.

These accounts show that opportunities to participate were consistently valued, but their feasibility depended on how relational conditions such as trust, teacher support, and peer dynamics intersected with structural constraints like exams and workload.

Taken together, relational and participatory resources worked in tandem: families, trust, teachers, and peers set the stage for agency, while participatory opportunities provided the stage on which agency could be performed. Their interplay explained why students in the private school described confidence and belonging, those in the gifted school emphasized resilience under pressure, and those in the public school often felt constrained by hierarchy and surveillance.

4.3 Institutional mediation of student agency

This theme addresses RQ3 by exploring how institutional practices, material conditions, and broader contextual factors mediate the enactment of student agency.

The visions and missions of each school were seen to have a major impact on students' individual resources, either positively or negatively. A positive impact would be generated if the school's visions and students' visions aligned to a large extent (Students 5, School 2). If the school's vision was to promote academic excellence, students who fell short of it might have low self-efficacy beliefs. In this way, institutional missions did not only set formal goals but also implicitly defined what kinds of agency were recognized and rewarded.

School capacity, including infrastructure and the class size, was a contextual issue discussed by Principals 1 and 3, and Head Teacher 1. When asked what they would like to change about the current practices to promote student agency, Principals 1 and 3 mentioned the expectation to do more for students yet the financial conditions, related to class sizes, school infrastructure, and teacher salary, had not yet afforded it. They both concurred that changes would take place, but it would take time. Students likewise reported that large class sizes and heavy teacher workloads limited the individualized attention they received, constraining opportunities for agency. Yet some also reframed constraints as challenges, describing difficult conditions as motivating them to prove themselves.

Assessment and surveillance also mediated agency across schools. In the gifted school, exams were often described as pushing students to set goals and persist, while in the public school, high-stakes testing was seen as overwhelming and limiting students' ability to engage beyond academics. Surveillance practices such as 24/7 cameras were defended by leaders as ensuring order but were viewed by students as violating trust and restricting their willingness to speak.

In summary, learning environments, influenced by family, trust, teacher support, participatory resources, and contextual factors, played a significant role in shaping student agency. These factors could either constrain or enable students' development of agency. At the institutional level, mission alignment, assessment, surveillance, and school capacity proved decisive: they framed not only the opportunities students had but also the meanings students attached to their own autonomy.

5 Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate that student agency in Vietnamese secondary schools is conceptualized and enacted in markedly different ways depending on institutional context. Across the three cases, agency was described variously as confidence and voice in the private school, as resilience and goal-setting in the gifted school, and as disciplined compliance in the public school. Relational and participatory resources such as family influence, trust, teacher support, peer dynamics, and opportunities for participation emerged as decisive in enabling or constraining students' ability to act. At the institutional level, mission alignment, assessment practices, surveillance, and material conditions further mediated agency, sometimes empowering students and at other times limiting their autonomy.

Taken together, these findings underscore that student agency is neither a stable nor universal construct, but a situated phenomenon negotiated within specific relationships and structures. What appears as empowerment in one context may be framed as resistance or disorder in another, while constraints such as exams or resource shortages can paradoxically be reframed as sources of motivation. By illuminating these contrasts, the study highlights both the opportunities and tensions inherent in promoting agency under the 2018 reform, where aspirations for student-centeredness intersect with entrenched hierarchies and exam culture. The following discussion situates these findings within existing literature and considers their implications for policy, practice, and future research on agency in Confucian Heritage Culture contexts.

5.1 Alignment with previous research

Many of the enabling factors identified—such as mutual trust, opportunities for voice, and support from teachers—are consistent with literature on agency in Western and non-Western contexts (e.g., Zeiser et al., 2018; OECD, 2019). The relational aspect of agency, particularly trust and communication, emerged as crucial in CHC settings where hierarchical values persist. The study supports the idea that agency is context-dependent, often negotiated rather than assumed, and shaped by institutional and cultural affordances (Nieminen and Tuohilampi, 2020).

The findings also support research showing that surveillance practices and ability grouping can undermine perceptions of fairness and autonomy, thus reducing students' willingness to speak up (Citron, 2024). In line with Reeve and Shin (2020), teacher encouragement emerged as a particularly important enabler, especially when coupled with equitable treatment. Taken together, these parallels suggest that agency in Vietnam shares common mechanisms with global patterns, while also carrying distinctive cultural inflections.

5.2 Emergent contributions

Beyond confirming known patterns, this study foregrounds three under-examined dimensions: family expectations and school mission alignment as mediating forces, the under-examined factor of contextual/ material capacity.

First, although the AUS framework emphasizes school-based resources, findings show that parental expectations and philosophies—sometimes institutionalized through agreements with schools—can significantly shape students' agency trajectories.

Second, students whose personal goals aligned with the school's stated mission reported higher self-efficacy and participation, whereas misalignment fostered disengagement.

Third, resource limitations (e.g., class size, infrastructure) were perceived my leaders as major obstacles to enacting participatory practices, suggesting that material capacity is an under-examined factor in agency research.

5.3 Implications for practice

For reforms to meaningfully foster student agency in CHC systems, implementation must go beyond curricular redesign, requiring trust-by-design with visible policies and practices that signal confidence in students' capacity to act responsibly.

Institutional practices must embrace transparency, shared responsibility, and a redefinition of trust and discipline. This includes revising surveillance protocols to balance safety with autonomy, involving students in setting monitoring policies. Schools can also create structured choice points in each subject (e.g., selecting project topics or assessment methods). Finally, they need to act upon student suggestions and communicate outcomes transparently.

Professional development for teachers that addresses cultural resistance to shared authority could facilitate this transition, to shift the relationship from unintended enemies to intentional alliances. Teachers could model participatory methods suited to CHC norms, such as guided co-decision-making rather than full autonomy from the outset (O'Brien et al., 2024).

Parents should also be engaged through triadic conferences (student-teacher-parent) to align expectations, particularly regarding assessment pressures and opportunities for student-led learning.

These steps together could help reposition students from passive recipients to active partners in their education. I hope to invite educators and leaders to rethink the messages students are receiving on their ends and the affordances for student agency in all educational processes.

5.4 Theoretical significance

This study extends the AUS framework in two key ways. First, it demonstrates how a university-oriented framework can be meaningfully applied to secondary education, with age-appropriate adaptations to items and constructs. Second, it enriches the framework by adding family influence and material resources as additional dimensions relevant to CHC settings, suggesting that future operationalization's of agency should account for these external layers. Crucially, the study also revealed the underexplored role of family expectations and school mission alignment, along with material constraints, as significant mediators in CHC settings. These adaptations and exploration suggest that future operationalization's of agency should account for both level-specific adjustments and cultural-contextual factors.

5.5 Limitations and future research

This study's limitations include a relatively small sample size and its restriction to northern Vietnamese schools. Further research could involve longitudinal analysis or mixed-methods studies to evaluate the evolution of agency in other CHC or transitional educational contexts. There is also room to expand the framework to incorporate emotional and cognitive dimensions omitted in the adapted AUS scale. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to understanding how student agency is shaped by the intersection of relational, institutional, and cultural factors in a reforming CHC system.

6 Conclusion

This study examined how student agency is enabled or constrained in Vietnamese secondary schools during the 2018 General Education Program reform. By analyzing perspectives from both students and school leaders, the study highlighted the complexity of fostering student voice and participation during systemic reform. Key enablers included trust, openness, and shared values, while major constraints stemmed from excessive surveillance, rigid ability grouping, institutional hierarchy, academic pressure, and cultural expectations of conformity. Crucially, the study also reveals the underexplored role of family expectations and school mission alignment, along with material constraints, as significant mediators in CHC settings. This work contributes to the evolving discourse on agency in non-Western settings and calls for stronger school–student alliances as a foundation for meaningful reform.

The research underscores the need for culturally responsive reform strategies—ones that consider power dynamics and local values when promoting student-centered learning. By adapting international frameworks like the AUS scale to local contexts, educators and researchers can better assess and nurture agency in ways that resonate with students' lived realities. Practically, it offers actionable strategies for school leaders and teachers to foster agency through trust-by-design, structured choice points, transparent feedback loops, and culturally responsive pedagogy.

To make student-centered reform meaningful, schools must move beyond curriculum redesign and address the everyday structures and relationships that shape how agency is experienced. Policymakers, leaders, teachers, and parents share responsibility for creating learning environments where students are not merely recipients of change but active partners in shaping it.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Mika Risku and Leena Haltunen from University of Jyvaskyla. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

MD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the teachers at the schools that enabled me to carry out the research. They lent me the access to the students through their kind words of introduction, actively setting me up for a seamless data collection process. Their support must not go without notice.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Berry, R. (2011). “Assessment reforms around the world,” in Assessment Reform in Education: Policy and Practice (Berlin: Springer), 89–102.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Briffett-Aktaş, C., Wong, K. L., Kong, W. F. O., and Ho, C. P. (2025). The student voice for social justice pedagogical method. Teach High Educ. 30, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2023.2183770

Cheng, A. Y. N. (2012). Student voice in a Chinese context: Investigating the key elements of leadership that enhance student voice. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 15, 351–366. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2011.605467

Citron, D. K. (2024). The Surveilled Student. Stanford Law Review, 76 (Symposium), 1439–1509. Available online at: https://review.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2024/10/Citron-76-Stan.-L.-Rev.-1439.pdf (Accessed September 16, 2025).

Czerniewicz, L., Williams, K., and Brown, C. (2009). Students make a plan: understanding student agency in constraining conditions. ALT-J 17, 75–88. doi: 10.1080/09687760903033058

Dello-Iacovo, B. (2009). Curriculum reform and “quality education” in China: an overview. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 29, 241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.02.008

Erss, M. (2023). Comparing student agency in an ethnically and culturally segregated society: how Estonian and Russian-speaking adolescents achieve agency in school. Pedag. Cult. Soc. 33, 439–461 doi: 10.1080/14681366.2023.2225529

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., and Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 45–65. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Ferguson, R., Phillips, S., Rowley, J., and Friedlander, J. (2015). Beyond Standardized Test Scores: Engagement, Mindsets, and Agency. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Hill, S. (2019). Softening the hierarchy: the role of student agency in building learning organizations. J. Prof. Capital Commun. 4, 147–162. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-07-2018-0019

Huynh, M. Q. (2022). “Change and continuity of education reforms in Vietnam: history, drivers, and niches,” in The Political Economy of Education Reforms in Vietnam (Abingdon: Routledge), 21–39.

Jääskelä, P., Heilala, V., Kärkkäinen, T., and Häkkinen, P. (2021). Student agency analytics: learning analytics as a tool for analysing student agency in higher education. Behav. Inform. Technol. 40, 790–808. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2020.1725130

Jackson, D. B. (2003). Education reform as if student agency mattered: academic microcultures and student identity. Phi Delta Kappan 84, 579–585. doi: 10.1177/003172170308400807

Jang, J. (2022). Learner agency in Korean high-school L2 writing: a qualitative study. Asian-Pacific J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 7:15. doi: 10.1186/s40862-022-00158-1

Klemenčič, M. (2015). “What is student agency? An ontological exploration in the context of research on student engagement,” in Student Engagement in Europe: Society, Higher Education and Student Governance (Strasbourg: Council of Europe), 11–29.

Matsumoto, Y. (2021). Student self-initiated use of smartphones in multilingual writing classrooms: making learner agency and multiple involvements visible. Modern Lang. J. 105, 142–174. doi: 10.1111/modl.12688

Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) (2018/2021). General Education Program (Consolidated version) [Văn bản họ'p nhất Chu'o'ng trình giáo dục phổ thông tổng thể]. Hanoi: MOET. Vietnamese. Available online at: https://moet.gov.vn/content/vanban/Lists/VBPQ/Attachments/1483/vbhn-chuong-trinh-tong-the.pdf (Accessed September 16, 2025).

Mitra, D. (2008). Student Voice in School Reform: Building Youth–Adult Partnerships that Strengthen Schools and Empower Youth. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Nhật, N. T. H., Dung, Ð. T. T., Hu'o'ng, L. T., Phu'o'ng, N. T. M., Phu'o'ng, T. T. M., Vân Anh, M. T., et al. (2023). Thụ'c tiễn triển khai Chu'o'ng trình giáo dục phổ thông 2018 môn Tiếng Anh: Góc nhìn tú' giáo viên thụ'c hiện chu'o'ng trình. Tạp chí Giáo dục 23, 58–63. Available online at: https://tcgd.tapchigiaoduc.edu.vn/index.php/tapchi/article/view/667

Nieminen, J. H., Tai, J., Boud, D., and Henderson, M. (2022). Student agency in feedback: beyond the individual. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 47, 95–108. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1887080

Nieminen, J. H., and Tuohilampi, L. (2020). ‘Finally studying for myself'–Examining student agency in summative and formative self-assessment models. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 45, 1031–1045. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1720595

O'Brien, N., Acton, F., Hadjisoteriou, C., Stefanek, E., Echsel, A., Hipp, K., et al. (2024). Student voices, migration, and bullying: a narrative review across six countries. Int. Perspect. Migrat. Bully. School 25, 15–35. doi: 10.4324/9781003439202-2

OECD (2019). Student Agency for 2030 Concept Note. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/projects/edu/education-2040/concept-notes/Student_Agency_for_2030_concept_note.pdf (Accessed September 16, 2025).

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (4th Edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Pham, H. (2021). “Challenges defining a life purpose in an exam-driven culture: a case of Vietnam,” in Proceedings of the 17th International Conference of the Asia Association of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (AsiaCALL 2021), 228–233. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.210226.028

Phuong, H. Y., Tran, N. B. C., Nguyen, T. T. L., Lam, T. D., Bui, N. Q., and Le, T. T. (2025). From tests to tasks: how Vietnamese EFL teachers navigate washback through formative assessment practices. Lang. Test. Asia 15:45. doi: 10.1186/s40468-025-00392-7

Phuong-Mai, N., Terlouw, C., and Pilot, A. (2005). Cooperative learning vs Confucian heritage culture's collectivism: confrontation to reveal some cultural conflicts and mismatch. Asia Europe J. 3, 403–419. doi: 10.1007/s10308-005-0008-4

Rector-Aranda, A., and Raider-Roth, M. (2015). ‘I finally felt like I had power': student agency and voice in an online and classroom-based role-play simulation. Res. Learn. Technol. 23:25569. doi: 10.3402/rlt.v23.25569

Reeve, J. (2012). “A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (Berlin: Springer), 149–172.

Reeve, J., and Shin, S. H. (2020). How teachers can support students' agentic engagement. Theory Into Pract. 59, 150–161. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2019.1702451

Simons, M., and Masschelein, J. (2008). The governmentalization of learning and the assemblage of a learning apparatus. Educ. Theor. 58, 391–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5446.2008.00296.x

Stenalt, M. H., and Lassesen, B. (2022). Does student agency benefit student learning? A systematic review of higher education research. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 47, 653–669. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1967874

Tan, C. (2017). “Confucianism and education,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Toshalis, E., and Nakkula, M. J. (2012). Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice. Boston, MA: Jobs for the Future.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 16, 837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121

Trommsdorff, G. (2012). Development of ‘agentic' regulation in cultural context: the role of self and world views. Child Dev. Perspect. 6, 19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00224.x

Vaughn, M. (2018). Making sense of student agency in the early grades. Phi Delta Kappan 99, 62–66. doi: 10.1177/0031721718767864

Vaughn, M., Premo, J., Sotirovska, V. V., and Erickson, D. (2020). Evaluating agency in literacy using the student agency profile. Read. Teach. 73, 427–441. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1853

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th Edn.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Yoon, J. (2021). Control and agency in student–teacher relations: A cross-cultural study of Finnish and Korean schools. Education Inquiry. 12, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/20004508.2020.1744350

Keywords: student agency, Confucian Heritage Culture, education reform, school leadership, power dynamics, student voice

Citation: Dang MT (2025) Mediating factors for student agency: perspectives of school leaders and students. Front. Educ. 10:1643768. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1643768

Received: 09 June 2025; Accepted: 15 September 2025;

Published: 02 October 2025.

Edited by:

Linda Kay Mayger, The College of New Jersey, United StatesReviewed by:

Rajesh Elangovan, Bishop Heber College, IndiaMuhammad Mohsan Ishaque, University of Gujrat, Pakistan

Copyright © 2025 Dang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Minh Tam Dang, dGFtLmRhbmdtaW5oQHBoZW5pa2FhLXVuaS5lZHUudm4=

Minh Tam Dang

Minh Tam Dang