- 1aSSIST University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 2Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University, School of Journalism and Cultural Communication, Xi'an, China

- 3Shanxi University of Finance and Economics, Law School Taiyuan, Taiyuan, China

Introduction: Legal films across nations exhibit significant differences in their modes of expression, which stem not only from the structural distinctions between the Civil Law System and Common Law System, but more deeply from the differing emphases in each country’s socio-legal ideology.

Methods: To explore the role and mechanisms of legal films in contemporary civic legal education, this study selects representative films from China, the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and South Korea. The research integrates Critical Legal Culture Theory with a comparative analytical approach, first constructing a multi-dimensional analytical framework based on theories of legal consciousness and narrative communication, and then applying this framework to compare the films’ narrative strategies, visual representations, and implied legal-cultural values.

Results: Findings reveal that legal films from the Common Law System tend to emphasize procedural justice and the struggle for litigation rights, highlighting institutional tensions. In contrast, films from the Civil Law System prioritize ethical concerns and the humanization of legal institutions, often presenting a more tempered critique and promoting systemic reconciliation. The educational efficacy of legal films lies in the complementarity between legal knowledge transmission and emotional engagement. This dual function enhances public understanding of legal principles while fostering a sense of institutional trust.

Discussion: Establishing intercultural interpretive frameworks and integrating legal films into structured civic education programs are essential steps toward advancing public legal consciousness and the development of civic legal education.

1 Introduction

Against the backdrop of the continuous advancement of global rule of law construction, enhancing citizens’ legal consciousness has become one of the core goals of building a rule-of-law society in various countries. Particularly in the current context of fragmented information and social diversification, traditional legal education models (such as classroom lectures and pamphlets) struggle to meet the public’s, especially young people’s, demand for and interest in acquiring legal knowledge. Exploring diverse and contextualized methods of legal communication has become an important direction for current legal education.

Film, as a mass medium integrating narrativity, emotionality, and esthetics, has been widely regarded in recent years as an important tool for promoting legal cognition and stimulating legal thinking. Research indicates that audiovisual works possess significant potential in shaping images of legal professions, disseminating knowledge of legal systems, and stimulating civic legal participation (Garmaev and Chumakova, 2016; Stefaniuk, 2024). Courtroom dramas and social realism films through the dramatization of specific cases, allow audiences to “immersively” understand abstract legal concepts and the functioning of systems, thereby indirectly enhancing their legal literacy.

Although the integration of law and film art has a certain theoretical foundation, empirical research on whether and how films effectively promote the enhancement of civic legal consciousness remains relatively scarce, especially systematic analysis from a cross-cultural comparative perspective. Significant differences exist among countries in legal systems, film industries, and social cultures, leading to diverse expressions in the form, narrative strategies, and educational functions of their legal-themed films. These differences warrant further exploration (Zeidler, 2021; Silbey and Slack, 2013).

To address this research gap, this study adopts the Comparative Case Analysis method, selecting five representative legal-themed films for in-depth analysis:

1) Chinese Film: Article 20 (2024).

2) American Film: A Civil Action (1998).

3) British Film: In the Name of the Father (1993).

4) Japanese Film: Justice (2006).

5) South Korean Film: My First Client (2019).

These five films all revolve around real or realistic legal themes, covering socially high-profile legal issues such as criminal defense, environmental law, child rights protection, and justifiable defense, possessing representativeness and comparative value. The selection of these specific films is justified by their significant social impact, critical acclaim, and their status as paradigmatic examples of legal narratives within their respective national contexts. For instance, A Civil Action and In the Name of the Father are frequently cited in law-and-film scholarship for their poignant critiques of the common law system. Article 20 sparked widespread public discussion in China regarding self-defense laws, while Justice and My First Client are representative works reflecting deep-seated anxieties about the judicial systems in Japan and South Korea. While their production dates span three decades, this chronological diversity is a deliberate choice, allowing the study to compare enduring legal-cultural traits against a backdrop of differing socio-political contexts. The strong political undertones, such as the Northern Ireland conflict in the British-Irish co-production In the Name of the Father, are not a limitation but a key object of analysis, revealing how national crises shape the narrative construction of justice and institutional legitimacy.

2 Literature review

2.1 Theoretical basis and practical dilemmas of legal education

Legal consciousness and legal literacy are fundamental components of civic education in rule-of-law states. Their core lies not only in the transmission of knowledge but also in cultivating trust in and a sense of participation in the law (Baeihaqi, 2020). Currently, most countries incorporate legal education into their civic curriculum systems, emphasizing its social integration function. However, traditional forms of legal education often remain stuck in the indoctrination of abstract legal provisions, lacking a sense of reality and emotional resonance, particularly lacking appeal and effectiveness for young people (Garmaev and Chumakova, 2016).

In Asian countries such as China, Japan, and Indonesia, legal education still faces the “instrumentalism” fallacy, where the acquisition of legal knowledge is the goal, neglecting the cultivation of legal faith and the space for institutional critique. Some studies point out that the lack of social reality dimensions and humanistic care in legal education leads citizens, especially youth, to remain alienated from the legal system (Pinto and Machado, 2024).

2.2 Integration of media and legal education: the potential efficacy of film

With the rise of media culture, film is no longer solely an entertainment form but increasingly demonstrates its dual function of narrative communication and cognitive construction. Denoncourt (2013) points out that film possesses the unique advantage of “visual case analysis” in legal teaching, aiding students in constructing systematic legal understanding and situational application skills.

More importantly, the narrative structure of film can stimulate audience empathy, prompting a “meaningful connection” to the law at the value level. Garmaev and Chumakova (2016), through empirical research at an international legal film festival, indicate that film can effectively promote public cognitive engagement with core issues such as criminal justice and procedural fairness, making it an ideal vehicle for “non-institutional, informal legal communication.”

However, critics also point out that the educational function of film lacks stability. On the one hand, mainstream legal-themed films, under commercial pressure, may tend toward dramatization and sensationalism, weakening the presentation of legal rational logic. On the other hand, the legal knowledge disseminated by films often simplifies or even misinterprets legal procedures and the essence of institutions, easily leading to the misleading perception of “superficial justice” (Greenfield et al., 2001).

2.3 Construction mechanisms of legal-themed films and civic legal consciousness

When film is systematically incorporated into educational practice as a “civic education tool,” its role should not be limited to “transmitting legal knowledge,” but should rather promote the audience’s deep thinking about social justice, institutional bias, and individual rights. Ces (2020), based on the film “School Bullying,” explores issues of juvenile criminal responsibility, indicating that legal films help reveal obscured legal issues and structural social imbalances.

In the analysis of the Japanese film Justice, Anderson (2012), from the perspective of judicial reform and wrongful convictions, critically points out that film is not only a teaching tool but also a text for social critique, prompting students to recognize the imperfection of law and institutional failure under social prejudice.

This critical viewing mode, known as “law-and-film scholarship,” has gradually replaced previous teaching practices focused primarily on “plot and story,” promoting a shift in legal education toward a multidimensional, multi-angled, interdisciplinary model that emphasizes the social interaction and psychological response between individuals and the law (Greenfield et al., 2001).

Although existing research fully demonstrates the unique value of film in enhancing legal consciousness, most studies are confined to a single film genre or a single national context. There is a lack of systematic cross-cultural comparative research, particularly on how legal films present concepts of justice, law, and social morality in civil law versus common law countries. Furthermore, existing research often focuses on the “import of legal knowledge” in teaching contexts, neglecting the potential mechanisms by which film constructs civic critical thinking, institutional trust, and behavioral intentions. This study will fill the research gap regarding the mechanisms and cultural differences in the “film-rule of law-civic consciousness” nexus through a comparative study of five legal-themed films from different legal systems and cultural backgrounds. Specifically, to address the lack of cross-cultural comparison, this study introduces Comparative Legal Culture Theory. To move beyond a simplistic focus on knowledge transmission and explore the construction of critical thinking, it integrates Ewick and Silbey’s theory of legal consciousness patterns and Green’s Narrative Persuasion Model. Finally, to analyze the often-overlooked visual dimension of legal narratives, the study incorporates insights from Visual Jurisprudence Theory, thereby constructing a comprehensive framework to systematically investigate how films shape civic legal consciousness.

3 Theoretical framework

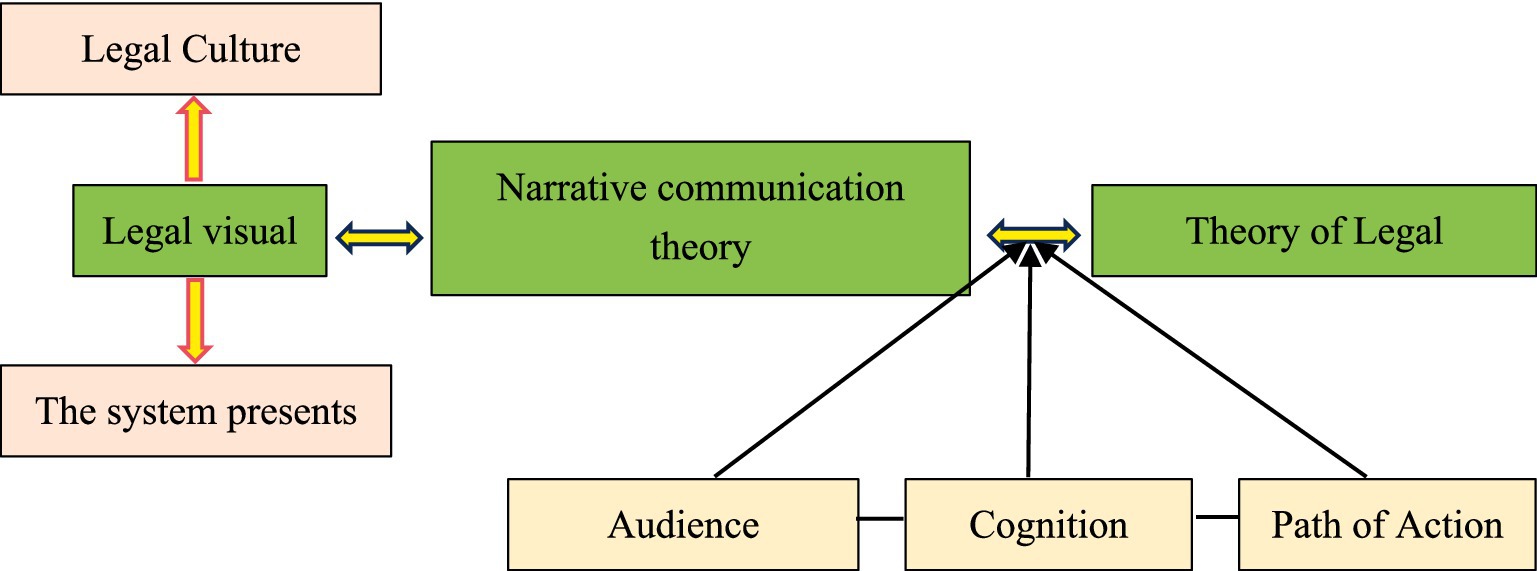

This study centers on the core question of “how film, as a medium of legal communication, influences civic legal consciousness,” constructing an interdisciplinary composite theoretical framework. We integrate the following theoretical systems from four dimensions: individual cognition, communication mechanisms, cultural meaning production, and institutional structural differences:

3.1 Pathways of legal consciousness generation: psychological mechanisms from cognition to action

Film influences legal consciousness not merely by imparting legal knowledge but by triggering a chain reaction of cognition-emotion-behavior. To explain this process, this study introduces Ewick and Silbey's (1998) “Three Patterns of Legal Consciousness” theory: “Before the Law”: Law is perceived as a sacred authority; individuals maintain distance and awe; “Against the Law”: Law is perceived as a tool of oppression; individuals adopt avoidance or resistance attitudes; “With the Law”: Law is treated as an operational resource for protecting one’s rights. This model reveals three potential psychological frameworks audiences adopt when facing legal narratives. Different films, by telling stories of “wronged individuals,” “victims,” or “rights defenders,” activate one or several of these patterns, thereby influencing the audience’s emotional positioning toward the legal system and behavioral intentions.

3.2 Film as an educational medium: narrative communication path model

The educational effect of film is not automatic but depends on the contextualization and structuring of its message. Green and Brock’s (2000) “Narrative Persuasion Model” provides a key insight, pointing out that media influence relies on “transportation”—the audience’s psychological immersion into the story world. Such immersive narratives can achieve “cognitive compliance” by reducing the audience’s motivation to counter-argue, thereby enhancing empathy and the acceptance of the values embedded in the story. Within this narrative frame, complex legal issues are “naturalized,” which can either reinforce or challenge the perception of institutional justice. For example, when films focus on sympathetic victims like children or the wrongfully convicted, audiences are more likely to unconsciously accept the film’s moral and legal stance. While this pathway has a strong educational function, it also carries the risk of emotional manipulation and factual distortion.

3.3 The visual culture of law: visual jurisprudence theory

As argued by Cover (1983) and later critical legal culture scholars, law is not merely a set of normative texts but is also a narrative structure and cultural symbol. Film excels at creating a “sense of institutional presence” and a “sense of justice” through images, symbols, and composition. Building on this, Greenfield et al. (2001) proposed the theory of “visual justice,” which argues that symbols in films—such as courtrooms, lawyers, and institutional buildings—possess constructive power in shaping how audiences “see” justice and the legitimacy of power. While most legal films visually reinforce institutional majesty and may overlook procedural flaws, a critical minority of films adopt a “de-sacralization” strategy, exposing legal failures and political interference to offer a powerful critique.

3.4 Cultural context embedding of legal systems: comparative legal culture theory

The formation of legal consciousness is not universal but is deeply constrained by its surrounding institutional culture. Friedman’s (1975) “Three-Layer Model of Legal Culture” posits that each country’s legal culture comprises the legal structure (formal rules), legal behavior (how people use the law), and legal mentality (public expectations of the law). This explains why different legal systems foster different conceptions of the relationship between the individual and the state. For example, common law systems (UK/US) tend to emphasize litigation rights, lawyer-centrism, and procedural justice. In contrast, civil law systems (China/Japan/South Korea) often prioritize legal stability, ethical coordination, and the balance of power and responsibility. Consequently, legal-themed films from different countries will inevitably exhibit different “images of justice” and “imaginaries of institutional pathways.”

3.5 Framework integration diagram (conceptual map)

The theoretical framework of this study aims to illustrate that legal-themed films, as visual narrative texts, not only convey legal knowledge but also, through immersive communication paths and the construction of legal cultural symbols, embed themselves into civic cognitive and behavioral structures, thereby shaping legal consciousness. The integrated theoretical framework diagram is shown in Figure 1.

3.6 Methodology

This study uses Qualitative Comparative Analysis to explore the selected films in depth. The analytical process was divided into two main steps that systematically combined the literature and theoretical frameworks described above:

3.6.1 Case selection and contextualization

This study combines five representative legal films, examining their effectiveness in terms of legal and cultural dissemination, visibility in the cinematic world, and exemplary representation of legal issues across various common law and civil law jurisdictions. Before the analysis, the socio-political and legal context of each film was examined to serve as a basis for interpretation.

3.6.2 Thematic and narrative analysis

The analyses were conducted by applying aspects of the camera portrayal and the pathways of construction of legal consciousness in the frames. This included: (a) mapping the narrative arc onto Ewick and Silbey’s “Three Modes of Legal Consciousness” to identify the protagonist’s and audience’s depictions of their relationship with the law. (2) Examining the film’s narrative strategies (e.g., point of view, emotional focus) through the lens of the Narrative Persuasion Model to understand its potential educational impact.

By systematically applying the two-step process to each case and then comparing the findings across cultures and legal systems, this study aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how legal films can be utilized as a civic legal education tool.

4 Case analysis

In contemporary society where the law is increasingly embedded in civic life, how to effectively enhance the legal consciousness and literacy of the public has become a core task for countries advancing rule-of-law construction. Compared to traditional formal legal education methods such as classrooms, lectures, and textbooks, film, as a mass medium combining narrativity, emotionality, and esthetics, possesses stronger perceptibility and acceptability. Its potential in civic legal education is increasingly recognized (Denoncourt, 2013; Greenfield et al., 2001).

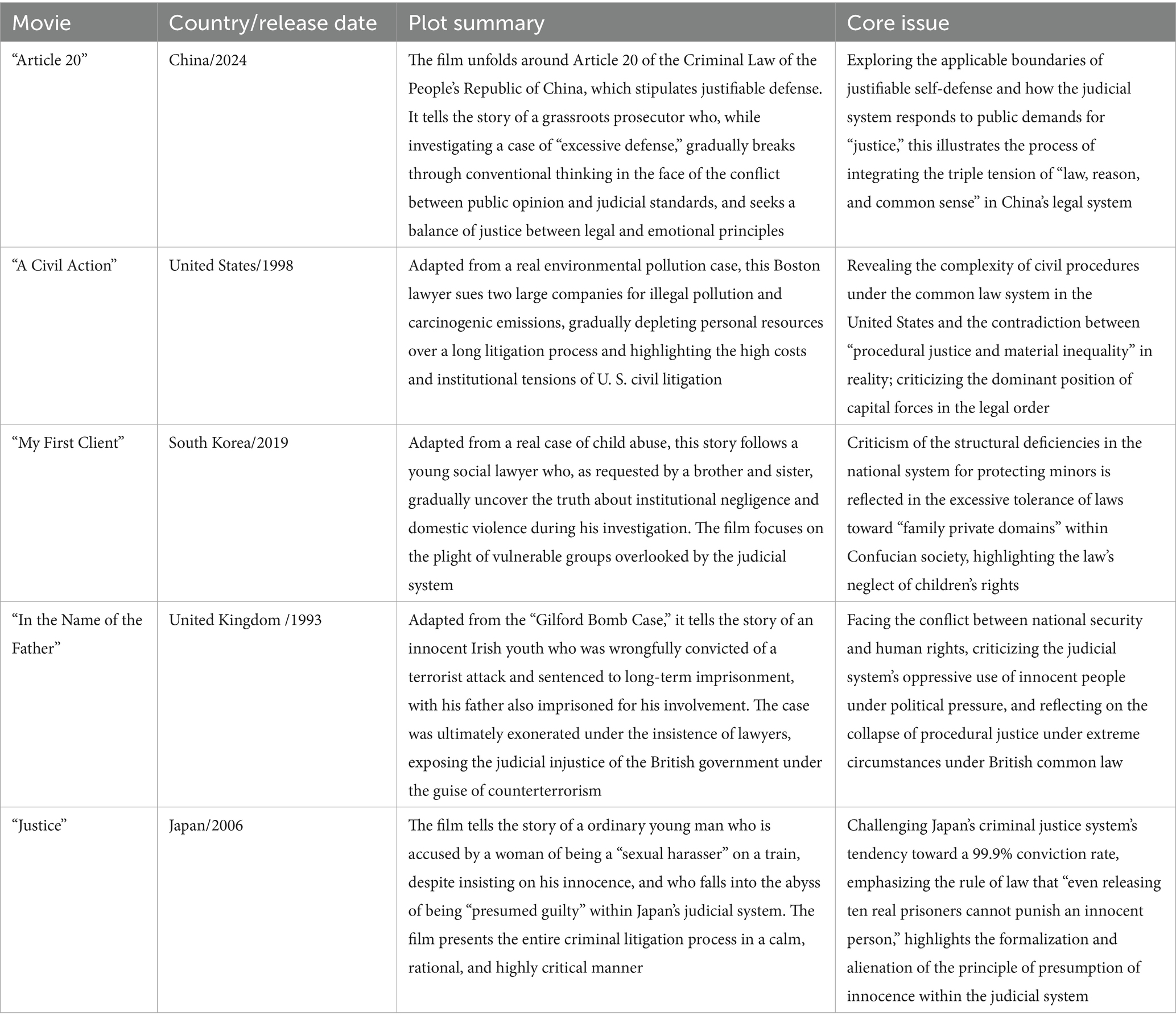

4.1 Overview of the five films

The five legal-themed films selected for this study originate from China, the US, South Korea, the UK, and Japan. Each is grounded in its own country’s judicial system and social reality, depicting the complex and tension-filled interactions among citizens, institutions, and the law. These works not only reproduce legal practice narratively but also construct the audience’s cognition of the rule of law at emotional and rational levels, possessing strong comparative analytical value. The plot summaries and core legal issues of the five films are outlined in Table 1.

These five films cover diverse legal themes including the right to justifiable defense, environmental law, child protection, political miscarriages of justice, and false sexual harassment imprisonment. They represent different legal systems (common law and civil law) and reflect cultural differences and institutional tensions in legal education and civic rights consciousness among the countries. These films are not only cultural reflections of national systems but also symbolic mechanisms for disseminating legal consciousness; their structure and expression embody “how institutions are narrated, how justice is perceived.”

4.2 Four-dimensional comparison of films and legal education

4.2.1 Construction pathways of legal consciousness: from trust to doubt

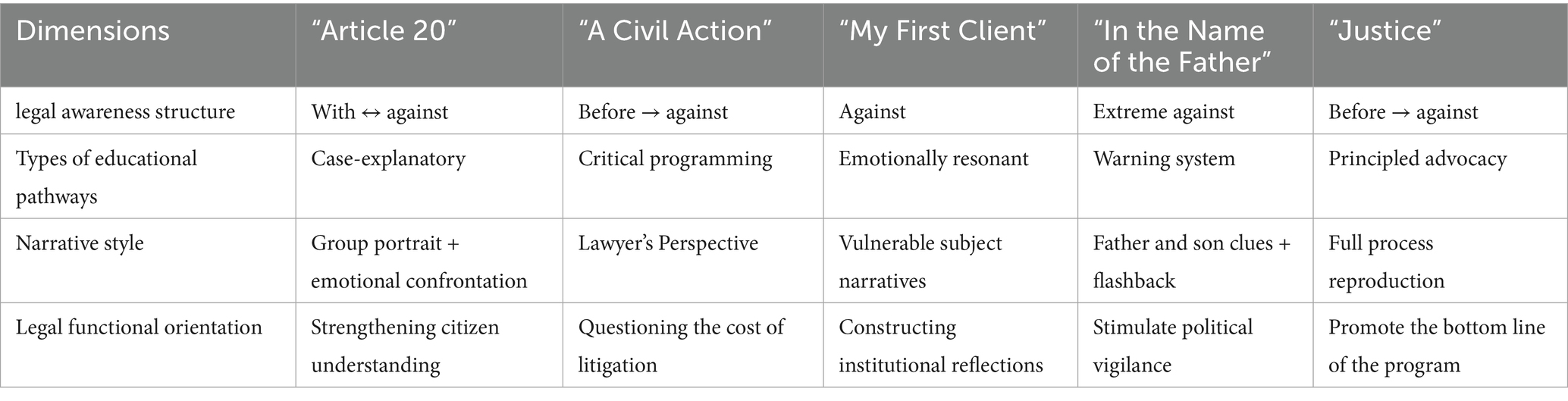

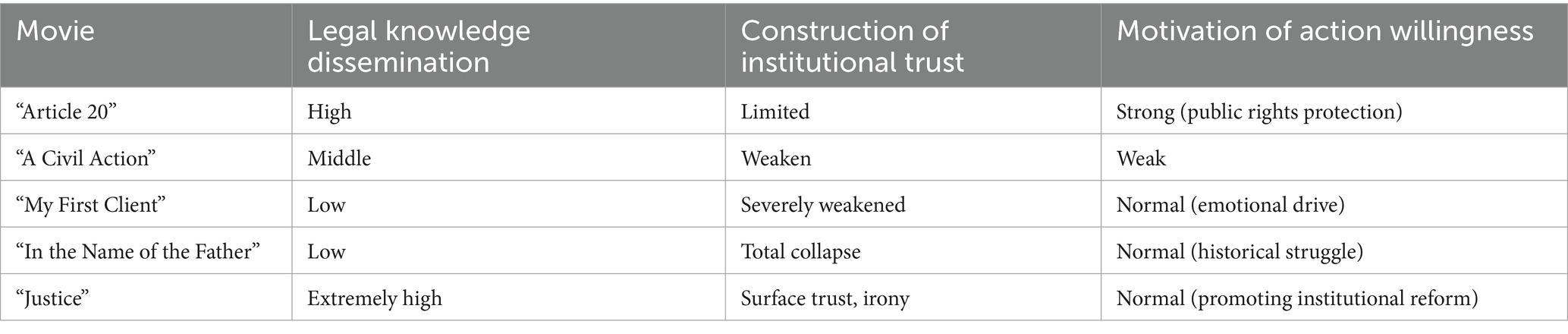

According to Ewick and Silbey’s (1998) legal consciousness theory, citizens’ understanding of the law often oscillates between three modes: “before the law,” “with the law,” and “against the law.” The presentation and transformation of legal consciousness in films provide a mirror for understanding the cognitive structures audiences might form. The comparison of legal communication and law popularization functions of the five films is shown in Table 2.

“Article 20” exhibits a flow of consciousness from “cooperating with the law” to “questioning legal boundaries,” encouraging audiences to contemplate the possibility of institutional repair. “A Civil Action” embodies a transition from trust to disillusionment; the lawyer follows procedure correctly but fails to achieve justice, reinforcing the audience’s perception of the disconnection between “procedure and substantive justice.” “My First Client” and “In the Name of the Father” completely detach from institutional trust, presenting the typical “against the law” state of legal disillusionment. “Justice” guides the audience, in an extremely calm manner, to recognize the “formal justice trap” beneath the institutional facade. This consciousness construction not only transmits emotion but also implies a “psychological path for legal education”—from blind faith, to doubt, to questioning and engagement.

4.2.2 Legal communication mechanisms: narrative strategies and educational typology spectrum

As a medium, the educational function of film depends not only on content but also closely on its narrative structure, perspective setting, and plot pacing (Green and Brock, 2000). Legal-themed films from different countries have formed distinct educational paths in strategy, as shown in Table 3.

“Article 20” simplifies complex legal terminology into everyday contexts, while “Justice” rigorously reproduces the Japanese judicial process. This communication mechanism enhances the “implicit education” effect, allowing audiences to unconsciously construct an understanding of the system. Films like “My First Client” use “emotional education” to evoke social responsibility, representing a complementary rather than knowledge-based path.

4.2.3 Visual presentation and institutional cognition: construction of space, color, and symbols

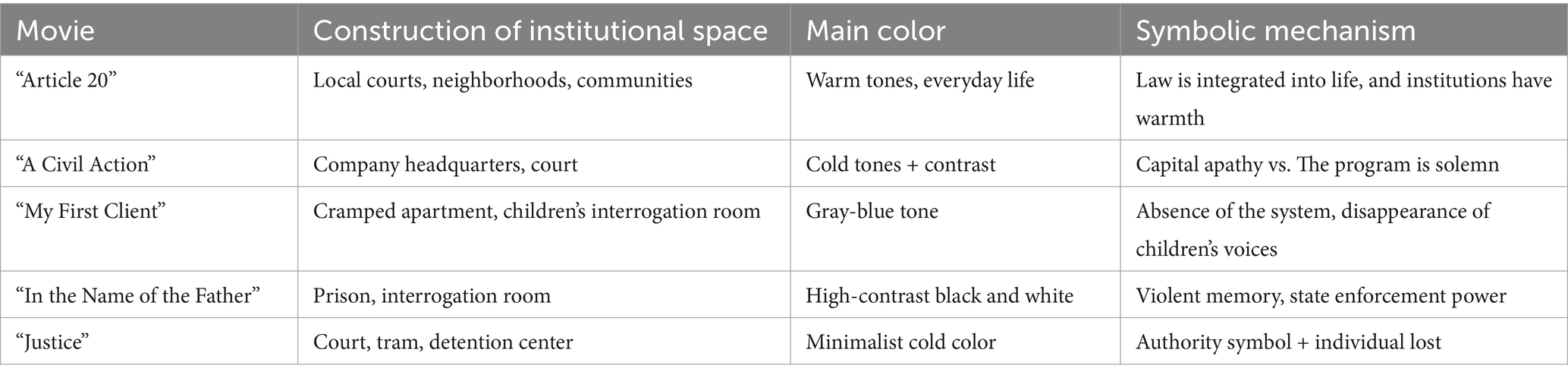

Law exists not only in text but is also perceived visually through images. Camera angles, composition, and color in legal-themed films constitute a “perceivable institutional experience” (Greenfield et al., 2001). The visual characteristics of the films are shown in Table 4.

These visual strategies intensify the audience’s subjective feelings toward the institution, thereby influencing their psychological construction of the law’s warmth, credibility, and accessibility, further promoting or undermining their institutional identification.

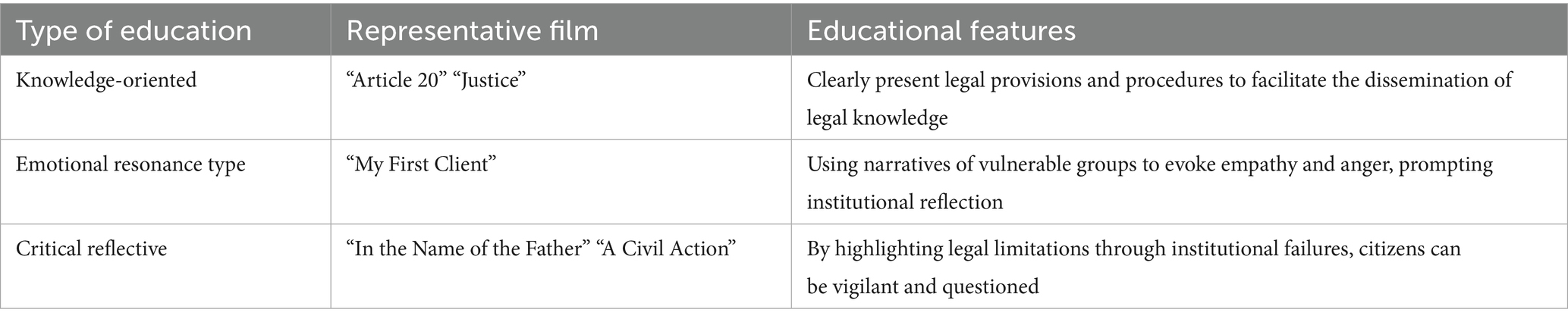

4.2.4 Educational efficacy: legal knowledge, institutional cognition, and behavioral intention

Judging the effectiveness of legal-themed films in law popularization requires returning to the core educational goals: Do citizens understand the law? Do they trust the law? Are they willing to exercise their rights according to the law? To objectively assess the educational efficacy of each film, this study evaluates them across three dimensions based on the following criteria. “Legal knowledge dissemination” is rated “High” if the film clearly explains specific legal articles or detailed judicial procedures (e.g., “Justice”), “Middle” if it focuses on legal principles without procedural detail (e.g., “A Civil Action”), and “Low” if legal knowledge is secondary to emotional drama (e.g., “My First Client”). “Construction of institutional trust” is assessed based on the film’s narrative outcome: it is considered “Weakened” or “Severely weakened” if the film portrays the legal system as failing the protagonists, leading to injustice, while “Limited” trust suggests the system is flawed but capable of reform. Finally, “Motivation of action willingness” is rated “Strong” or “Normal” if the film’s narrative encourages citizens to actively defend their rights, seek institutional reform, or engage in public discussion, and “Weak” if it fosters a sense of helplessness or cynicism. The educational dimensions are shown in Table 5.

Film education is not always effective; its efficacy in law popularization depends on narrative intent, audience structure, cultural cognitive presuppositions, and the foundation of institutional legitimacy.

4.3 Summary

Through in-depth analysis of five legal-themed films, this study finds that film is a cultural translator for legal education, not a one-way propaganda tool. As a “cultural law popularization medium,” film is not solely used to disseminate legal knowledge but rather to shape the public’s emotional cognitive structure toward the legal system. In form, it achieves the transformation from “legal text” to “institutional experience.” In function, it combines knowledge transmission, emotional arousal, and critical construction, demonstrating a deep educational power beyond traditional law popularization campaigns.

However, the educational effectiveness is significantly influenced by differences in national institutional foundations, legal cultural mentalities, and social sentiments. Legal-themed films may serve as a confirmation of legitimacy in some cultures while becoming a deconstruction of legitimacy in others. Film should not be simplistically viewed as a “substitute textbook” but should be incorporated into the cultural strategic framework of legal education, working together with institutional design, school education, and public communication to construct a multidimensional civic legal education system.

5 Discussion

5.1 The institutional structural influence of legal culture on legal expression in film

The educational efficacy of legal films is closely related to the cultural tradition of their institutional context. Common law systems (e.g., UK/US) emphasize procedural justice, litigation strategy, and the role of lawyers. Therefore, their films often depict “struggles within institutional procedures.” This is powerfully illustrated in “A Civil Action,” where the narrative foregrounds the lawyer’s exhausting battle with procedural rules, discovery motions, and the strategic maneuvering against powerful corporate opponents, ultimately showing how procedural victory does not guarantee substantive justice. Similarly, In the Name of the Father critiques the catastrophic failure of procedural safeguards under political pressure, where the fight for exoneration is a decades-long struggle against a flawed verdict. In contrast, civil law systems (e.g., China/Japan/Korea) place greater emphasis on substantive justice, judge dominance, and ethical negotiation, exhibiting stronger moral and humanistic tones. For example, the Chinese film “Article 20” not on courtroom tactics but on a prosecutor’s internal and external struggle to align a legal ruling with public morality and common sense, reflecting a search for substantive fairness within the state apparatus. Likewise, the Japanese film justice critiques the system not through procedural battles, but by calmly exposing how the principle of “presumption of innocence” can become a hollow formality within a system geared toward conviction. This difference is reflected not only in plot structure but also in the way audiences’ legal consciousness is constructed. For instance, the British film “In the Name of the Father” centers on critiquing state violence, undermining institutional trust. Conversely, the Chinese film “Article 20″ attempts to seek reconciliation and institutional repair space within the interplay of reason, feeling, and law, reflecting a “culturally embedded mild critique.” Skorobogatov (2024) points out that legal culture not only determines the operational mode of legal systems but also profoundly shapes the “narrative permissibility structure of legal expression.”

5.2 Comparative effectiveness of narrative modes in enhancing legal consciousness

Different narrative strategies impact audience legal cognition to varying degrees. Rational narratives (e.g., “Justice”) help clearly convey legal knowledge and procedural structures, possessing significant “knowledge-based education” advantages. Emotional narratives (e.g., “My First Client,” “In the Name of the Father”) are more likely to trigger institutional critique awareness and action mobilization, belonging to “emotion-arousal education.”

According to Cowan and Harding (2022), emotion-driven narratives are more likely to stimulate “resistant legal consciousness” and intuitive feelings about structural injustice. Simultaneously, O’Malley (2011) emphasizes that rational narratives are more suitable for systematic curriculum teaching, promoting students’ formation of structural legal thinking. The two are not opposites but constitute complementary mechanisms: Knowledge + Emotion = Understanding + Action, forming an ideal three-stage legal education model (Know-Believe-Act).

5.3 Educational value vs. commerciality: the structural tension of film art

Although film possesses advantages for legal education communication, its nature as a commercial cultural product also limits the depth and universality of its educational function. Meyer and Davis (2019) notes that legal expression in film is often dominated by plot propulsion and audience acceptance; legal knowledge is compressed into “narrative symbols” or “emotional induction tools.” Black (1999), in an esthetic analysis of courtroom films, argues that justice in film is often an “entertaining symbolic justice,” its narrative logic serving plot climaxes rather than legal rigor.

Legal-themed film education possesses a dual tension: on the one hand, it has high perceptibility and dissemination power; on the other hand, it carries risks of “simplification and misguidance,” “emotional overload,” and “institutional trivialization.” This reminds us that in legal education, film should be viewed as a “complementary” medium, not a “dominant” teaching material, especially concerning complex legal procedures and public law theories.

5.4 Empirical effects and potential impacts of civic legal education

From a legal sociology perspective, the empirical impact of film-based law popularization is mainly manifested at three levels: enhancing cognitive levels; influencing institutional trust structures; and stimulating willingness for action participation (Young and Billings, 2020).

Empirical research shows that audiences with high cultural capital are more likely to extract legal behavioral strategies and institutional cognition from films, forming stronger “institutional participation-oriented legal consciousness” (Young and Billings, 2020). However, for audiences lacking basic legal education, films may instead exacerbate the “sense of legal distance” and institutional disillusionment.

This finding suggests that film-based law popularization should adopt differentiated guidance based on the social resource structures and cultural capabilities of different groups. Garmaev and Chumakova (2016) propose that film festivals, public screenings, and interactive viewing courses help “bridge the perceptual gap between vulnerable groups and legal texts.”

In summary, film should not be seen as an ancillary tool for legal education but should establish its position as a “cultural translator” within institutional communication strategies. Future legal communication needs to transcend the “indoctrination model” and move toward the construction of a multidimensional interactive “cultural legal education ecosystem.”

6 Suggestions

6.1 Systematically incorporate legal-themed films into legal education structures

As a medium, film’s efficacy in law popularization far surpasses traditional propaganda methods, with advantages in contextual construction, role immersion, and institutional imagination. However, within existing education systems, legal-themed films generally occupy a non-systematic position of “passive introduction,” lacking stable pedagogical integration pathways. Films like “Article 20” and “Justice” possess clear educational potential in presenting institutional structures, but without corresponding teaching mechanisms, their knowledge content struggles to form sustainable cognition.

Legal education curricula need to establish the position of legal-themed films within teaching scenarios. Modules like “Legal Issues in Film and Television” could be set up in secondary school general education courses. In higher education, specialized courses such as “Law and Image” or “Legal Narrative Analysis” should be constructed to systematically guide students in identifying legal concepts, analyzing procedural justice, and reflecting on institutional logic through films. Furthermore, courses should be equipped with teaching guides, viewing structure sheets, and legal provision comparison materials, ensuring film viewing transcends emotional resonance and becomes an organic part of legal knowledge dissemination and thinking training.

6.2 Clarify educational applicability paths for different film types

Film works exhibit high heterogeneity in legal expression methods, ranging from rational-realistic works focusing on procedural reenactment to ethical-narrative works using emotional impact to guide institutional critique. “Justice” provides a complete presentation of the criminal litigation process, suitable as “knowledge-based law popularization material.” “My First Client” focuses on emotional construction and critique of institutional indifference, suitable for value reflection and ethical analysis.

Based on this typological difference, the “functional adaptation principle” should be established in legal education: applying different types of legal-themed films to different educational goals. In professional legal teaching, films with complete procedural structures and clear correspondence to legal provisions, such as “Justice” and “A Civil Action,” are more suitable for training procedural recognition and case analysis skills. For public legal enlightenment education, emotion-driven works like “My First Client” and “In the Name of the Father” can be introduced to guide audiences to focus on rights violation scenarios and institutional justice logic, thereby enhancing willingness for institutional participation.

6.3 Establish communication interpretation mechanisms across cultural institutional backgrounds

When disseminating legal-themed films across multiple legal systems and cultural backgrounds, institutional misinterpretation and cognitive tension are inevitable. The presentation of the “99.9% conviction rate” in Justice, without understanding the context of Japan’s lay judge system reform, might be misunderstood by audiences as indicative of “universal injustice in all criminal justice systems.” This problem exists not only in international communication but also among audiences with different educational levels and cultural backgrounds within the same country.

To avoid institutional dislocation understanding, an “institutional literacy mechanism” should be constructed in the dissemination of legal-themed films. Film education or screening activities should be accompanied by explanatory materials on the institutional background, concisely outlining the judicial structure, legal logic, and reform controversies of the country reflected in the film, enabling audiences to gain basic institutional orientation before entering the narrative plot. In multinational comparative law teaching, comparative viewings based on themes should be organized, such as comparative analysis of China’s “Article 20” and American courtroom drama works centered on “justifiable defense,” strengthening students’ understanding of different institutional paths through structural juxtaposition.

6.4 Regulate the tension between institutional distrust in film narratives and belief in the rule of law

Legal expression in films often creates dramatic tension through plot elements like individual injustice, institutional failure, and power abuse. While this expression helps stimulate the audience’s moral outrage and institutional critique awareness, it may also, under conditions lacking guidance, lead to cognitive imbalance regarding the legal system as a whole. “In the Name of the Father” profoundly reveals state judicial violence mechanisms through its wrongful conviction narrative but can also easily trigger comprehensive distrust of the judicial system among audiences.

In educational practice, attention should be paid to guiding audiences to transition from emotional institutional critique to structural institutional reflection. Post-viewing discussions or teaching analyses should set guiding questions, such as: “Which links caused the legal failure depicted in the film?” “Does the system offer repair paths?” “Does the protagonist’s rights defense logic conform to the institutional framework?” Through such analysis, students can learn to distinguish case deviations from the institution itself, and emotional responses from action strategies, thereby achieving the transformation of critical legal consciousness into constructive belief in the rule of law.

6.5 Promote institutional integration and graded use of legal film and television resources

Currently, resources for legal-themed film and television works are scattered, and evaluation systems are lacking. This results in excellent works failing to effectively enter educational channels, while ordinary works frequently enter public legal communication without proper screening. Emotion-driven works may increase audience attention but do not necessarily possess high-quality legal knowledge expression.

To optimize the management of educational resources for legal-themed films, a specialized “Legal Film and Television Education Resource Library” should be established. Legal education experts, film researchers, and legal practitioners should jointly participate in selecting works suitable for different legal education goals, annotating their educational applicability scope, core issues, legal professionalism level, and institutional authenticity level. Furthermore, it is recommended to develop a “Legal Film Education Adaptation Guide” based on this, providing usage suggestions and teaching templates for teachers and law popularization workers, promoting the transition of legal-themed films from random use to standardized integration.

The role of film lies not in replicating legal provisions but in creating a “perceivable institutional space.” It transforms abstract legal articles into lived experience, turns rights awareness into embodied emotion, and brings institutional logic into everyday imagination. Precisely because its educational role is not explicit, it requires dual support from institutional norms and cultural guidance. The effective use of legal-themed films in education should not be limited to the selection of dissemination content. It requires embedding within curriculum structures, identification of genre functions, supplementation of institutional contexts, and ethical regulation of narrative tensions to achieve deep interaction among “institution - media - citizen.” Only then can film truly become a powerful cultural mechanism for advancing civic legal education, rather than merely an affecting legal performance.

7 Conclusion

This study, using representative legal-themed films from China, the US, the UK, Japan, and South Korea as case studies, systematically explored the function, mechanisms, and limitations of film in contemporary civic legal education through comparative analysis and critical legal culture theory. The results show that legal-themed films, through character identification, plot engagement, and institutional visualization, effectively promote audience cognition and emotional experience of legal issues, expanding the dissemination methods of traditional law popularization. Different legal system backgrounds profoundly influence film narratives and educational orientations: Common law systems emphasize procedural justice and individual litigation rights, often presenting institutional tensions and compromised outcomes; Civil law systems focus more on ethics and institutional humanization, tending toward idealized representations. These structural differences lead to varied performances of films in knowledge transmission, trust building, and behavioral motivation.

Legal-themed films face challenges such as ambiguous genre functions, insufficient pedagogical integration, cultural context dislocation, and tensions in institutional trust, indicating that their educational role is not spontaneous but requires institutional guidance and teaching integration. Based on this, the paper recommends incorporating legal-themed films into curriculum systems, clarifying their genre functions, establishing legal cultural interpretation mechanisms, and developing structured resources to promote the deep integration of film and legal education. Overall, legal-themed films are not only visual representations of legal systems but also narrative fields for civic legal consciousness, capable of stimulating emotional resonance and prompting structural reflection. In the future, against the backdrop of coexisting global media environments and crises of the rule of law, legal-themed films will continue to serve as a vital interface for civic legal education, enriching the public’s cognitive pathways toward justice, institutions, and responsibility.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, K. (2012). Reflections on justice, the lay judge system, and legal education in and out of Japan. Asian J. Comp. Law 7, 1–21. doi: 10.1017/S2194607800000648

Baeihaqi, (2020). civic education learning based on law-related education approach in developing student’s law awareness, advances in social science, education and humanities research. doi: 10.2991/assehr.k.200320.009

Ces, A. V. (2020). “Estudio del acoso escolar y la responsabilidad penal de los menores al hilo de la película «Bullying»: un aprendizaje del derecho penal de menores a través del cine” in Revista Jurídica de Investigación e Innovación Educativa (REJIE Nueva Época), 79–98.

Cover, R. (1983). The supreme court, 1982 term--foreword: Nomos and narrative 97, 1. doi: 10.2307/1340787

Cowan, D., and Harding, R. (2022). Legal consciousness and administrative justice. In M. Hertogh, R. Kirkham, R. Thomas, and J. Tomlinson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Administrative Justice. Oxford University Press. 437–456. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190903084.013.21

Denoncourt, J. A. (2013). Using film to enhance intellectual property law education: getting the message across. Eur. J. Law Technol. 4. Available online at: https://www.ejlt.org/index.php/ejlt/article/view/188/283

Ewick, P., and Silbey, S. S. (1998). The common place of law: Stories from everyday life : University of Chicago Press.

Garmaev, Y. P., and Chumakova, L. P. (2016). International festival of student films as the innovative means of legal education and multimedia training of future lawyers. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 11, 8606–8616. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1118307.pdf

Green, M. C., and Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 701–721. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701

Meyer, P. N., and Davis, C. (2019). Law students go to the movies II: using clips from classic Hollywood movies to teach criminal law and legal storytelling to first-year law students. J. Leg. Educ. 68:37. Available online at: https://jle.aals.org/home/vol68/iss1/7/

O’Malley, M. K. (2011). Through a different lens: using film to teach family law. Fam. Court. Rev. 49, 715–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1617.2011.01408.x

Pinto, J. C., and Machado, S. S. (2024). Cinema as a pedagogical practice in higher education: A case study applied to labour law. Int. J. Teach. Learn. Educ. 3, 1–3. doi: 10.22161/ijtle

Silbey, J., and Slack, M. H. (2013). “The semiotics of film in US supreme court cases” in Law, culture and visual studies (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 179–203.

Skorobogatov, A. V. (2024). A literacy narrative in legal discourse of Russia. Russian Law Online, 5–13. doi: 10.17803/2542-2472.2024.31.3.005-013

Stefaniuk, M. (2024). Image of the Community of Legal Professionals in the television coverage–a case study. Studia Iuridica Lublinensia 33, 301–322. doi: 10.17951/sil.2024.33.1.301-322

Young, K. M., and Billings, K. R. (2020). Legal consciousness and cultural capital. Law Soc. Rev. 54, 33–65. doi: 10.1111/lasr.12455

Keywords: legal-themed films, legal culture, civic legal education, cross-country legal, legal discourse

Citation: Song M, Jin J, Hou D and Zheng S (2025) Legal narratives in Chinese, American, British, Japanese, and South Korean films and comparative research on civic legal education. Front. Educ. 10:1644060. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1644060

Edited by:

Changsong Wang, Xiamen University Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Xiaotian Gao, University of Malaya, MalaysiaCheng Fei Yong, Xiamen University Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Song, Jin, Hou and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shaoxin Zheng, MTg4MTQxNDc0NjlAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Shaoxin Zheng, orcid.org/0009-0003-1898-4191

Mujie Song

Mujie Song Jiemei Jin2

Jiemei Jin2 Shaoxin Zheng

Shaoxin Zheng