- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Education College, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

This mixed-method experimental study investigates the effectiveness and typology of interactional feedback in supporting digital game-based language learning, focusing on two groups of primary language teachers. The experimental group employed interactional feedback within digital game-based language learning, while the comparison group used interactional feedback in traditional teaching methods. Results showed that the experimental group experienced statistically significant improvements in interactional feedback across three assessment points, whereas the comparison group showed no significant changes. The teachers in the experimental group employed a range of interactional feedback strategies, with notable improvements in clarification requests, recasts, and metalinguistic cues. Conversely, the comparison group primarily relied on repetition and direct correction, showing limited variation in their feedback approaches. Results also revealed that teachers in the experimental group significantly shifted their conceptions of interactional feedback, focusing not only on addressing interaction issues but also on recognizing the importance of uptake, output modification, and fostering student engagement through enriched screen time and enhanced teacher-student interactions. Further research should be encouraged and supported to develop digital games that prioritize teacher-student interaction, specifically by integrating interactional feedback as a standard feature. Collaborations between industry and researchers could play a crucial role in creating designs that effectively enhance interaction.

Introduction

Incorporating opportunities for students to practice newly acquired skills and knowledge is crucial when designing and implementing instructional technology. Although many instructional theories include recommendations for digital game-based learning, these theories should also explore how instructional digital games can benefit the teaching of younger students (Behnamnia et al., 2023).

Some educators have theorized that digital games effectively offer engaging exercises for newly acquired skills and knowledge because they necessitate students’ active involvement in learning (Coleman and Money, 2020; Laakso et al., 2021). Other scholars have posited that digital games decrease students’ active engagement in the learning process because they are confined to winning and encountering defeat, and due to their complexity or overwhelming results, they often fail to attain learning completion (Chen et al., 2020). Some researchers have reported that using digital games helps students engage in interactive events and express themselves effectively during presentations (Wang, 2020). They also highlighted the crucial role of teachers in providing ample opportunities for interaction and support (Foster and Shah, 2020). Others have reported that digital games effectively enhance students’ language learning and proficiency in formulaic expressions (Tang and Taguchi, 2021; Yu and Tsuei, 2023). Yet others have reported that practicing letters, sounds, syllables, and words through digital game-based learning contributes to enhancing the learning abilities of students, particularly those who are slower learners (Salgarayeva et al., 2021).

Despite the potential effectiveness of digital games, proponents of gaming have suggested that inconsistent findings from some research regarding the adverse effects of digital games on students’ learning can be attributed to a lack of clear instructions and undefined types of knowledge and skills (Ağaoğlu and Şad, 2020). Research on the utilization of digital games in language learning has generally yielded findings related to overall language comprehension rather than specific types of knowledge and skills (Eltahir et al., 2021). One effective way to maximize their benefits is through co-use by adults and children. Studies show that young children learn more digital media when guided by an adult (Lee et al., 2022; Paulus et al., 2024).

This study investigated the effectiveness of professional development (PD) program on teachers’ use of interactional feedback when teaching language through digital game-based learning. It also examined teachers’ conceptual understanding and explanations of interactional feedback by comparing those in the experimental group with those in the comparison group. Because the study was designed to integrate digital games into classroom teaching, the researcher attempted to use digital games that involve dialogue and interaction with characters. Additionally, the researcher developed types of interactive language based on what has been published on interactive language (Edmondson et al., 2023; Mushin et al., 2023; Wiltschko, 2021). Interactive language comprises various elements, including model verbs, imperatives, tag questions, ellipsis, backchanneling, fillers, and interjections, based on which the researcher developed types of interactive language (Lyster and Mori, 2006; Mackey et al., 2000; Mackey and Oliver, 2002; Nassaji, 2015, 2020). Furthermore, interactional feedback comprises verbal and non-verbal feedback, paralinguistic cues, visual feedback, feedback through written communication, feedback through actions, and meta-communication (Ellis et al., 2008). Furthermore, this study is motivated by recent research on the effectiveness of digital game-based learning (Abdul Ghani et al., 2022; Eltahir et al., 2021; Liu and Hwang, 2024) and by the lack of empirical studies examining how teachers provide interactional feedback when using digital game-based language learning. Therefore, this study is driven by the following research questions:

(1) How did professional development on interactional feedback strategies using digital game-based learning impact teachers’ practices of interactional feedback in the experimental group?

(2) How did the teachers in the comparison group implement interactional feedback?

(3) What types of interactional feedback strategies were implemented by experimental and comparison groups of teachers?

(4) How did the teachers in the experimental group conceive of using interactional feedback in digital game-based learning before and after?

Literature review

This section begins by examining the theoretical foundations of digital game-based language learning, followed by a thorough literature review that investigates the relationship between digital games and interactional feedback.

Digital game-based learning

Digital game-based learning involves leveraging the engaging nature of digital games for educational purposes. It emerges from a blend of educational and gaming components comprising two crucial aspects: entertainment and an educational element (Behnamnia et al., 2023). The digital game-based learning literature and effectiveness studies have considered both learning and engagement (Ağaoğlu and Şad, 2020; Hense and Mandl, 2014).

The effectiveness of digital game-based learning can be investigated through formative evaluation, which focuses on improvement over time, or through summative evaluation, which assesses the outcomes to determine whether digital game-based learning achieves its goals (All et al., 2016). Although studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of digital game-based learning (Eltahir et al., 2021; Salgarayeva et al., 2021), some authors have highlighted the importance of considering factors that contribute to the reliability and validity of these findings. These factors include ensuring sufficient time spent on tasks between experimental and control groups and incorporating principals for active participation, engagement, and communication during learning activities (Foster and Shah, 2020; Zhao et al., 2022).

Studies on the effectiveness of digital game-based learning have also revealed that its implementation necessitates the presence of an instructor during the intervention with various roles, including supervision, offering procedural assessment during gameplay, or providing contextualization of gameplay and in-game elements within the broader learning context (Huizenga et al., 2017; Tzuo et al., 2012).

The findings of studies on interactive language provide early insight into the developmental trajectory of language within interactions: speakers shift from using a limited range of literal uses of language to adopting a wider range of situated language for interaction. These include illocutionary acts, initiating agreements or disagreements, signaling active interaction or transitions, organizing discourse, and conveying emotion or reaction (Ford and Mori, 1994; Pekarek Doehler and Eskildsen, 2022). Researchers in interactional linguistics share certain assumptions with those in dynamic syntax, including the idea that language requires a syntax conceptualized as a dynamic process. A syntactic of this sort has three necessary properties: incremental, dialogical, and, therefore, reliant on constructions—that is, construction grammar rather than being fully compositional (Goldberg, 2009). However, much less is known about the effects of digital game-based learning on students’ interactive language. Previous research on the use of digital games to enhance students’ skills has predominantly focused on learning language in general rather than on interactive language aspects.

Interactional feedback

Interactional feedback encompasses responses triggered by linguistically incorrect and communicatively inappropriate utterances that learners produce during conversational interaction. This feedback can manifest through various negotiation and conversational strategies, including repetition, clarification requests, and confirmation checks (Nassaji, 2020). This approach assumes that these strategies emphasize linguistic problems, prompting learners to focus on structure during communicative interactions. As interactional feedback occurs during communicative interaction, it assists learners in addressing form while processing meaning (Sheen and Ellis, 2011).

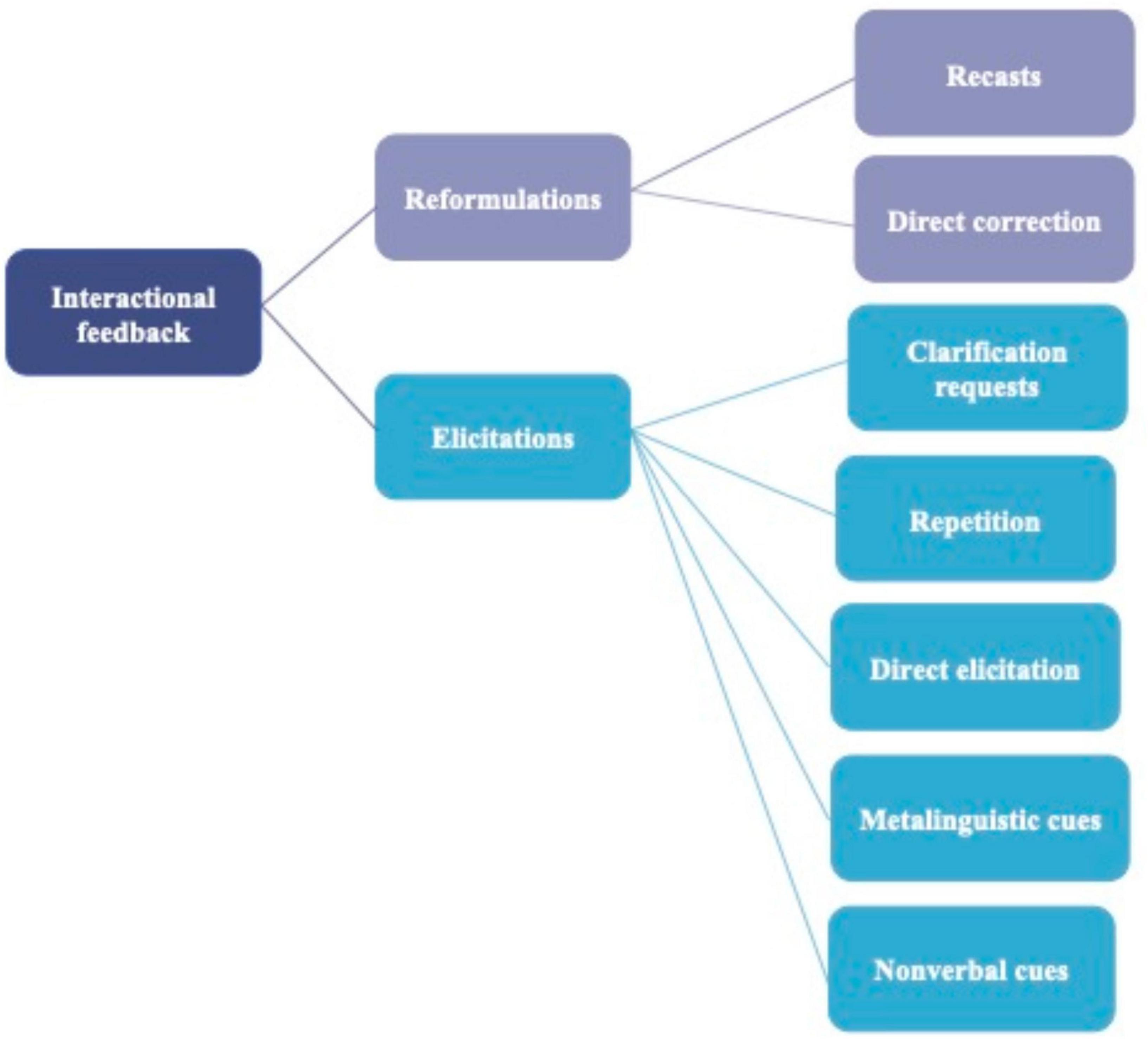

Interactional feedback, predominantly verbal feedback, occurs in both naturalistic and classroom settings. It directs learners’ focus toward linguistic form through implicit methods, such as strategies employed to address communication challenges and more explicit approaches that deliberately highlight specific linguistic structures regardless of any communication breakdown (Yousefi and Nassaji, 2021). Figure 1 summarizes the typology of interactional feedback that will be examined in this study.

Studies investigating interactional feedback have identified various types of feedback used by teachers or other participants in interactions with learners, typically falling into two main types: reformulations, including recasts and direct correction, and elicitations, which comprise clarification, repetition, direct elicitation, metalinguistic cues, and non-verbal cues (Buchari, 2022; Lyster et al., 2013; Nassaji, 2015).

DGBLL and teacher feedback

Previous research has demonstrated the potential of digital games, particularly those designed for educational purposes, to enhance language learning. For instance, serious digital games have been shown to effectively teach the correct use of modals, gerunds, and infinitives (Abdul Ghani et al., 2022; Castillo-Cuesta, 2020). Furthermore, studies indicate that digital games positively impact students’ learning outcomes, especially for those with lower initial intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy (Liu and Hwang, 2024).

Digital game-based language learning (DGBLL) and feedback have garnered increasing interest in the field of language learning. Several studies have examined various forms of feedback, including written (Reynolds and Kao, 2021; Shintani and Ellis, 2015; Shintani et al., 2014), computer-automated (Zhao and MacWhinney, 2018), oral (Rassaei, 2015), and metalinguistic corrective feedback in computer-mediated communication (Gao and Ma, 2019; Monteiro, 2014). Other studies indicate that effective feedback emphasizes the learning approaches and support necessary for a motivating learning experience, with a particular emphasis on reflective practices (Ravyse et al., 2017). This involves integrating feedback into a task-based instructional approach, informing the player, intervening when misconceptions arise, and providing appropriate hints or feedback, ensuring that interventions are both unobtrusive and timely (Esteban, 2024; Rachayon and Soontornwipast, 2019).

Moreover, previous research on the relationship between DGBLL and feedback has shown that feedback not only facilitates learning but also positively influences students’ attitudes and immersion in the learning process (Erhel and Jamet, 2013; Kickmeier-Rust et al., 2008; Laurillard, 2016). However, studies specifically examining teachers’ interactional feedback in the context of digital game-based language learning are much less common. This gap highlights the need for more focused research on how teachers’ interactional feedback can further enhance the effectiveness of DGBL, potentially leading to more nuanced insights into optimizing educational outcomes through tailored interactional feedback mechanisms.

Methodology

Design

This study examined the effectiveness of training on Arabic language teachers’ ability to implement interactional feedback strategies while teaching Arabic language through digital game-based learning to fifth-grade primary students. Their practices were compared to those who had only received regular training. An embedded mixed methods design triangulated design was employed, integrating quantitative and qualitative data to address research questions effectively. The convergent validation (triangulation) approach enhanced reliability and validity by examining the phenomenon from multiple perspectives, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding. The embedded design is an effective approach for designing interventions, emphasizing the timing of data collection and the rationale for integrating different data types (Creswell, 2021; Tashakkori et al., 2020). In this study, the intervention for the experimental group was guided by collecting data on their practices and conceptions of interactional feedback, both before and after the intervention. This informed the development of relevant instruments that represented participants’ perspectives.

The qualitative data was later used to reassess the experimental group’s practices and conceptions of interactional feedback following the program. Creswell (2021) emphasizes that mixed quantitative and qualitative approaches are effective and comprehensive methods for researchers investigating the meaning of phenomena in natural settings. In this study, the quantitative data facilitated a comparison of interactional feedback practices between the experimental and comparison groups. The purpose of quantitative research is to provide a valid and objective description of phenomena (Cohen et al., 2011). Researchers strive for objectivity and validity by controlling variables and minimizing biases in data analysis and interpretation. Quantitative research complements qualitative findings, particularly when comparing groups or examining relationships between variables. However, challenges exist, as complete control over variables is difficult in classroom case studies, and quantitative methods alone may not fully address complex research questions (Creswell, 2012). Quantitative methods were employed in this study to numerically assess teachers’ interactional feedback in supporting digital game-based language learning. Qualitative data were also collected through interviews to explore teachers’ conceptions of how to use interactional feedback in this context, which were classified and organized into appropriate themes. Quantitative pre- and post-observational interventions were conducted both before and after the professional development sessions, along with qualitative pre- and post-interview interventions.

Participants and sampling

To select the appropriate classrooms for this study, the researcher reached out to volunteer participants by sending letters to a diverse group of primary school teachers in Al-Qunfudah city, southern Saudi Arabia. These letters outlined the study’s purpose and procedures, emphasizing the significance of their participation. Out of 76 primary Arabic language school teachers, 43 responded. Given the focus of the study, 40 male primary Arabic language school teachers from the 43 respondents, representing 12 boys’ schools, were randomly selected and divided into two groups: The experimental group and the comparison group, with 20 teachers in each group. Their teaching experience ranged from 11 to 16 years. This mixed-method experimental study aimed not to generalize findings to a broader population but to conduct an in-depth exploration of a central phenomenon (Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2021). The research questions were examined through quantitative and qualitative investigation into the impact of professional development program on teachers’ enactment and conception of interactional feedback strategies within digital game-based language settings. The practices and conceptions of interactional feedback strategies of 20 experimental group teachers were compared to those of the 20 teachers in the comparison group.

The 20 teachers in the experimental group participated in a 12-week intervention program, which included pre-and post -and post-workshops, classroom observations, interviews, and follow-up meetings. The workshops and subsequent monitoring sessions provided support in learning and practicing interactional feedback strategies while teaching the Arabic language in a digital game-based learning environment. Throughout the intervention, the teachers implemented these strategies, while the researcher analyzed changes in their interactional feedback practices. At the end of the program, the teachers reflected on their conceptions of interactional feedback strategies after having enacted them in the context of teaching language through digital game-based learning. The 20 teachers in the comparison group participated in standard training sessions conducted by regional supervisors from the Department of Education. These sessions focused on providing background knowledge on interactional feedback, and digital game-based language learning. Unlike the experimental group, the comparison group teachers only attended a 1-week advisory session and did not receive any additional training on embedded strategies for interactional feedback or digital game-based language learning.

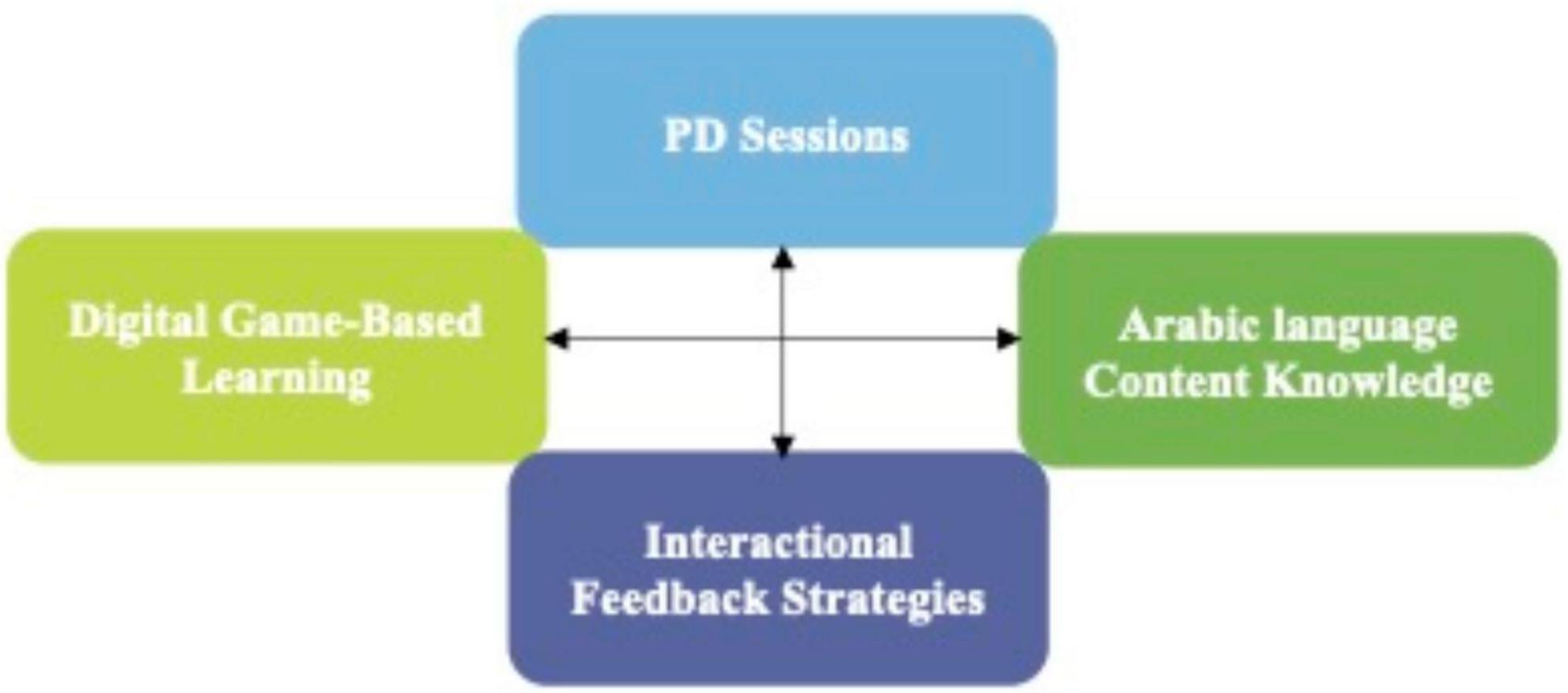

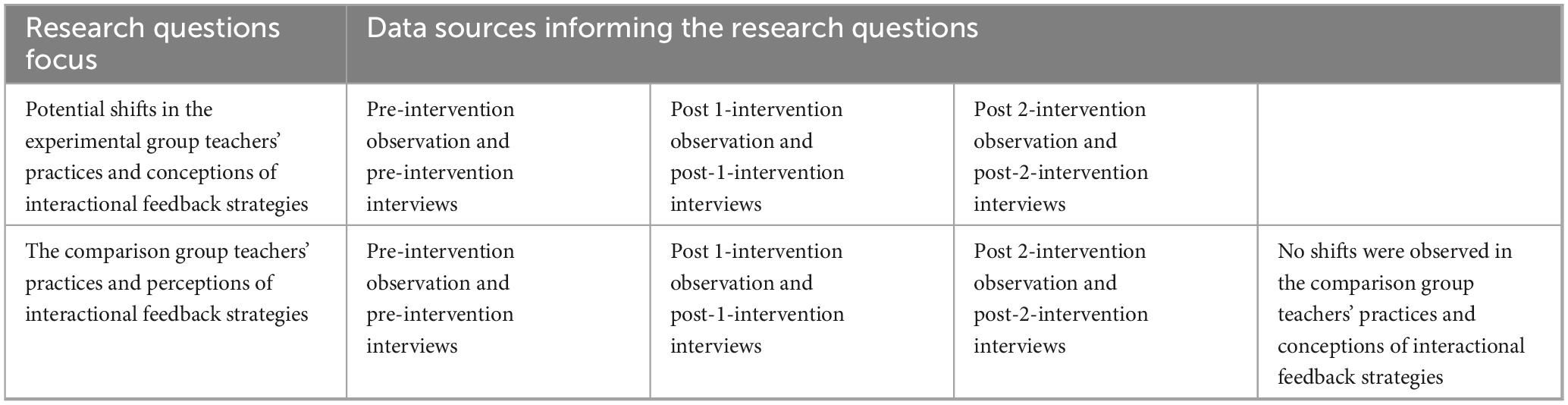

The data collection strategies included pre- and post-professional development observations and interviews with experimental group teachers. Similarly, pre-and post -observations and interviews were conducted with the comparison group teachers following their regular teaching. Figure 2 illustrates the interactions between the different components of the program.

Materials and instruments

The professional development workshops for the experimental teachers

The initial workshop sessions were informed by previous research on the types and subtypes of interactional feedback (Lyster and Mori, 2006; Mackey and Oliver, 2002; Nassaji, 2015, 2020). During the intervention, the teachers in the experimental group engaged in collaborative discussions to explore the characteristics and practical applications of each feedback type. They were encouraged to articulate their understanding and share their insights into implementing these strategies in classroom settings. When necessary, the researcher posed probing questions to deepen the discussion and ensure a focused examination of key concepts and pedagogical practices.

The professional development workshops focused on the distinct roles of teachers and students in interactional feedback. In the initial phase, teachers were introduced to two primary types of interactional feedback: reformulations and elicitations. The sessions on reformulation-based feedback emphasized its significance and practical application, engaging teachers in activities where they rephrased students’ erroneous utterances into correct forms. This approach included techniques such as recasts and direct correction. The workshops also explored elicitation-based strategies, which aimed to encourage students to self-correct rather than receiving the correct form directly from the teacher. These strategies included clarification requests, repetition, direct elicitation, metalinguistic cues, and non-verbal cues. Through guided discussion and hands-on activities, teachers developed a deeper understanding of these interactional feedback strategies and their effective implementation in digital game-based learning environments.

The following workshops focused on integrating interactional feedback strategies into the teaching of Arabic language within a digital game-based learning environment. A key emphasis was placed on ensuring that all feedback strategies were meaningfully connected to the content. Developing an effective environment for interactional feedback requires a strong understanding of the subject matter, as a teacher’s depth of knowledge directly influences the quality of feedback provided. This, in turn, encourages students to engage with the material on a deeper level.

The digital game supporting teacher-student interactions

Diverse interpretations exist for the term “digital games,” and grasping its construct entails identifying several characteristics. Typically, digital games comprise a simulated reality or a virtual setting, a defined set of rules governing progression, an intended outcome, and a group of online players who may act individually or collaboratively as a team (Clark et al., 2016; Gros, 2007). Players are actively engaged in digital games, which often involve interaction and competition (Chanel et al., 2012; Erickson and Sammons-Lohse, 2021). Digital games used for educational purposes should align with precise learning goals and offer prompt feedback to participants (Anastasiadis et al., 2018; Yang and Lu, 2021). Digital game design holds significant potential to support parents and teachers in fostering language-enhancing interactions during media use with students. This is especially important, as adult-child interactions are among the most influential factors in language development. Recent research indicate that digital games are most effective when adults actively engage with students using language-supportive strategies, as opposed to students using digital media independently without guidance (Mathers et al., 2025).

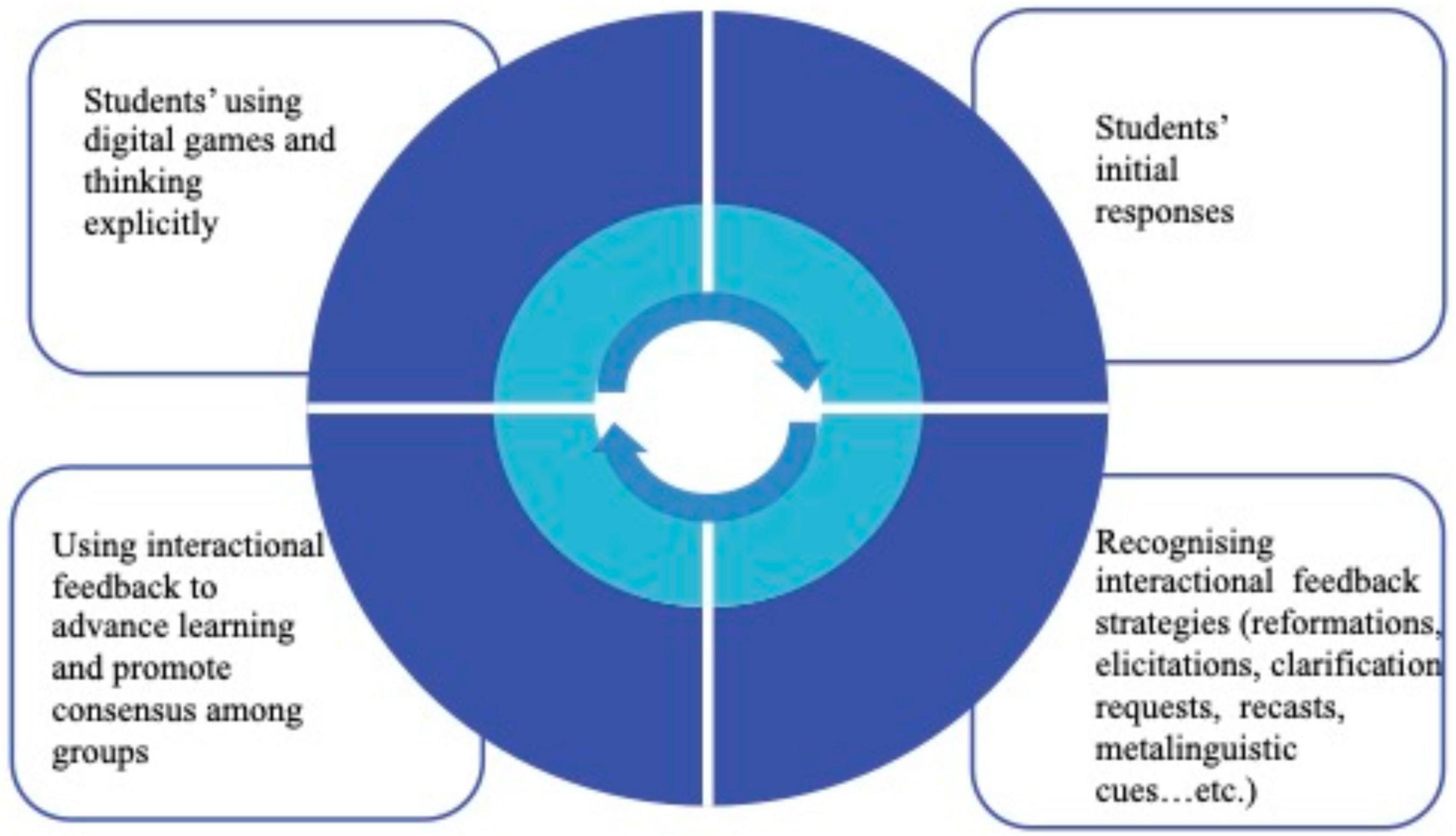

The digital game used in this study incorporated the aforementioned elements. The researcher provided teachers in the experimental group with available digital games that support Arabic language learning1,2 The game rules were designed to promote both interactive competition and cooperation, following the stages of interactional feedback cycles as illustrated in Figure 3. Firstly, student team members were required to engage with Arabic language digital games, explicitly thinking and discussing each question together before offering an answer, all while being aware that they were competing against another team. This phase encouraged students in the second step to articulate their thoughts and responses. Thirdly, as they interacted, the teachers were instructed to consider appropriate interactional feedback that aligned with students’ initial responses to guide them during their discussion, recognizing various strategies such as reformations, elicitations, clarification requests, recasts, and metalinguistic cues. Lastly, the teachers utilized the selected interactional feedback to advance student learning and promote consensus among groups.

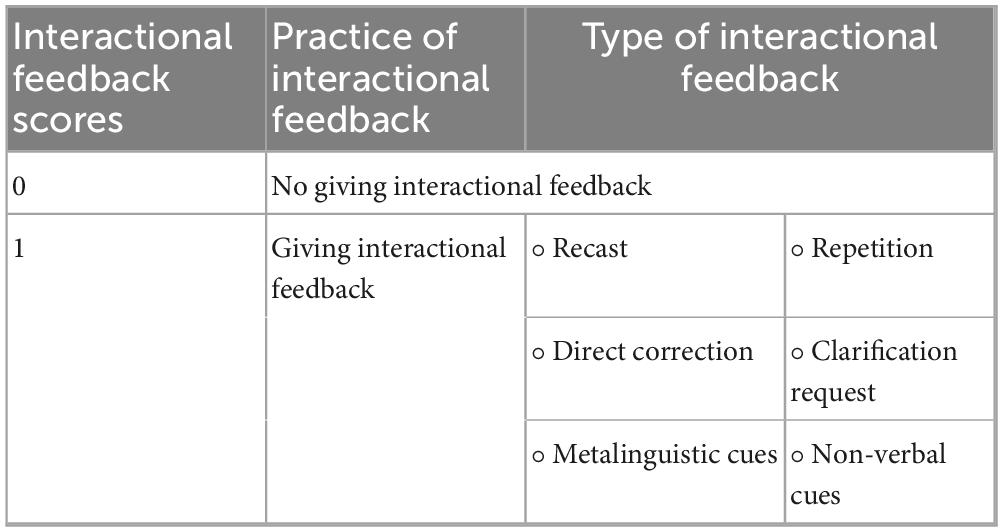

The data on teachers’ interactional feedback come from recorded videos across the three-time points: Before, during, and at the end of the use of digital games in the experimental group and during the use of the traditional teaching method in the comparison group. Subsequently, the researcher analyzed each recorded video, coding the teachers’ interactional feedback and related scores (Table 1).

The purpose of recording and subsequent analysis of videos was to meticulously compare interactional feedback employed by teachers from both experimental and comparison groups. Through scrutiny of the recorded interactional feedback, the researcher aimed to discern any discernible differences in the approaches employed by teachers from each group.

Data collection procedures

Data on participant teachers was collected from multiple sources, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative data. The integration of these diverse data facilitated triangulation, strengthening the evidence supporting each research question. Table 2 presents the research questions and the data sources that were used to address them.

Teachers in the experimental group participated in interviews and observations both before and after their engagement in the professional development program. In the initial stage, data was collected before they participated in the workshops. This involved researcher-led observations of their interactional feedback practices, followed by interviews to gain deeper insights into their conceptions of interactional feedback. At conclusion of this stage, pre-tests were administered to the students of the experimental group teachers. In the second stage, the professional development workshops were designed and refined based on the findings from the teachers’ pre-interviews and prior lesson observations. The primary objective of these sessions was to enhance their interactional feedback strategies and integrate them effectively into their teaching, particularly while teaching Arabic language in a digital game-based learning environment. In the third stage, the experimental group’s implementation of interactional feedback strategies was observed to document their interactional feedback practices while teaching Arabic language in a digital game-based learning environment. Following these observations, the teachers participated in follow-up interviews, where they reflected on their conceptions of interactional feedback and their understanding of the strategies used in its application. The teachers in the comparison group were observed and interviewed before and after participating in advisory sessions, which focused on Arabic language sessions outlined in the national curriculum but did not include additional professional development on enhancing interactional feedback strategies. Following the advisory sessions, these teachers were observed and interviewed again to document their interactional feedback practices and conceptions of interactional feedback.

Ethical considerations

The research design of this study necessitated ethical considerations for accessing study sites and participants. After obtaining ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee, approvals were secured from the Ministry of Education’s gatekeeper and the principals of the selected schools. To guarantee voluntary participation and informed consent, teachers and student’s parents signed a consent form at the study’s outset. Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, the types of data collected, and their roles. Coding systems were used to protect participant anonymity; real names were removed before data analysis, and all names were replaced with pseudonyms. Confidentiality was also maintained during the transcription of audiotapes, data analysis, draft documents, and publication of research findings.

Data analysis

The statistical package SPSS (Ver. 29) was utilized for the quantitative results. A repeated measure ANOVA was conducted as prescribed by Pallant (2020). This analysis was carried out to assess the impact of intervention on the experimental group compared to the comparison group, focusing on the teachers’ practices of interactional feedback in supporting digital game-based language learning across three-time points: pre- and post-professional development activities.

The teachers’ conceptions of how to use interactional feedback to support digital game-based language learning were qualitatively analyzed using a five-step process outlined to analyze verbatim transcriptions of interviews (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Terry et al., 2017). Maintaining a reflective approach, the researcher refrained from imposing personal interpretations on that data. Initially, the researcher read and listened to all recorded interviews to gain a comprehensive understanding before sorting or coding. In the second step, descriptive phrases related to participants’ conceptions of how to use interactional feedback to support digital game-based language learning were extracted. The third step involved creating preliminary codes by segmenting and labeling these phrases to identify commonalities. In the fourth step, categories were formed by aggregating similar codes, if necessary. Finally, themes were identified by comparing and examining the codes and categories for similarities and differences. Furthermore, it was essential to validate the researcher’s interpretations through triangulation, which included peer debriefing and ensuring inter-coder reliability (Creswell and Poth, 2016). To achieve this, an associate professor who had no involvement in the classroom observations, interviews, or document analysis was recruited and trained to conduct an independent analysis. The trained rater and the researcher engaged in discussions about the codes and themes that emerged from the data, comparing them with original statements from the transcriptions of classroom observations, interviews, and documents. This comparison aimed to clarify, elaborate on, or challenge the identified codes and themes during the data analysis process.

Results

In this section, the researcher first presents the quantitative results, followed by the qualitative results.

Quantitative results

This section presents the results and analysis of the quantitative data in two subsections, addressing the first question regarding pre-and post-intervention practices of interactional feedback among experimental and comparison group teachers (R1) and the second question regarding the types of interactional feedback among both groups.

The pre-and post-intervention practices of interactional feedback among experimental and comparison group teachers

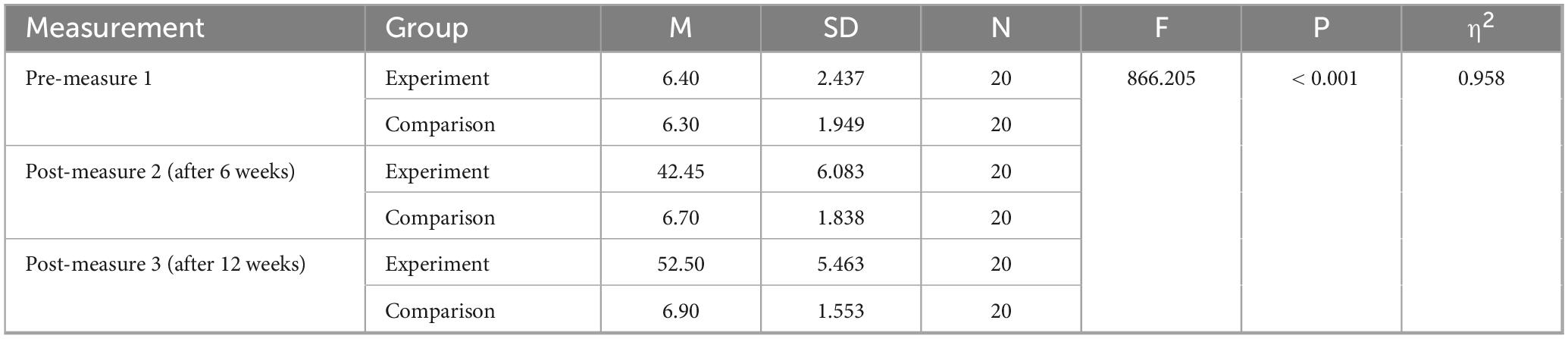

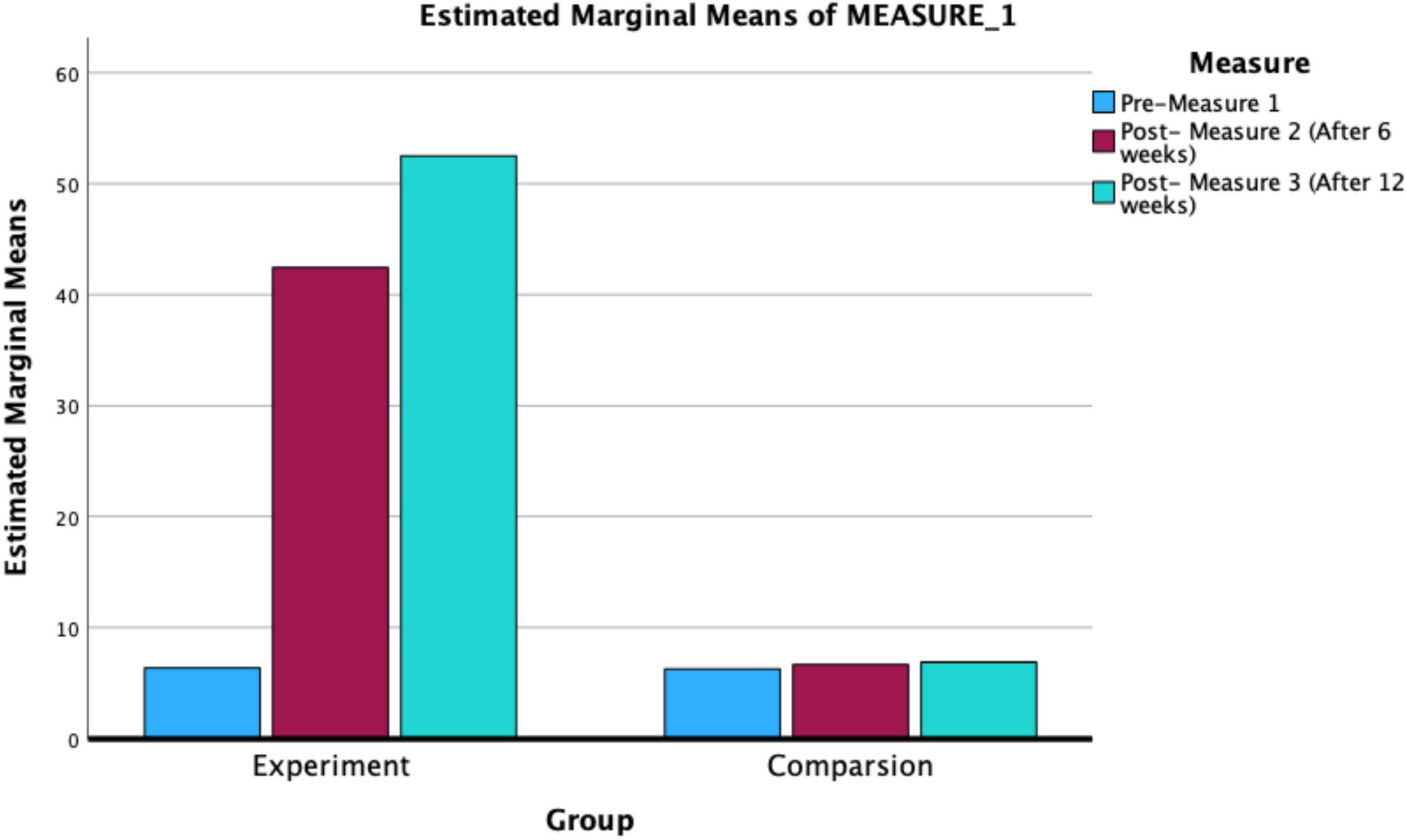

The results indicated a significant difference in the pre-and post-intervention practices of interactional feedback among experimental and comparison group teachers over time. A repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that the mean scores differed significantly across the three-time points (F = 866.205, P < 0.001). Effect-size estimates for teachers’ interactional feedback variable was η2 = 0. 958 (Table 3).

The result of repeated-measures ANOVA, which indicated significant differences across the three-time points between the experimental and comparison groups, is likely to align with the scatter plot presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Differences across the three time points between teachers’ experimental and comparison groups.

Figure 4 showcasing mean scores for each measure across three-time points, indicates a difference between the mean scores of teachers in the two groups.

Types of interactional feedback among experimental and comparison group teachers

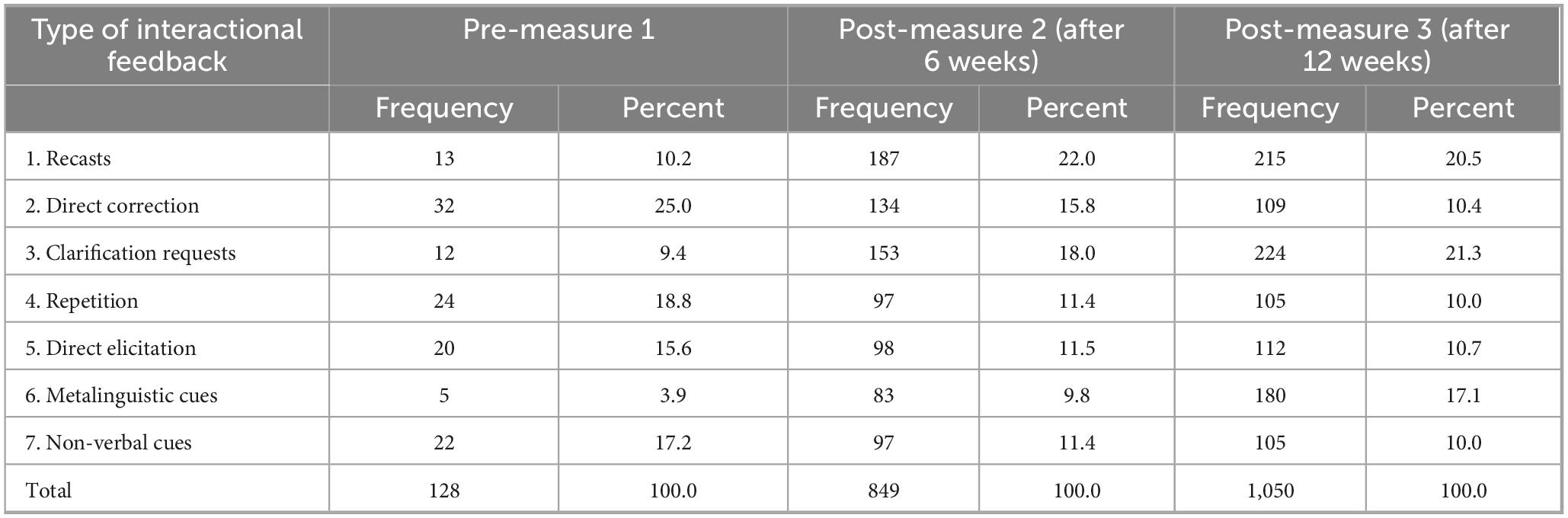

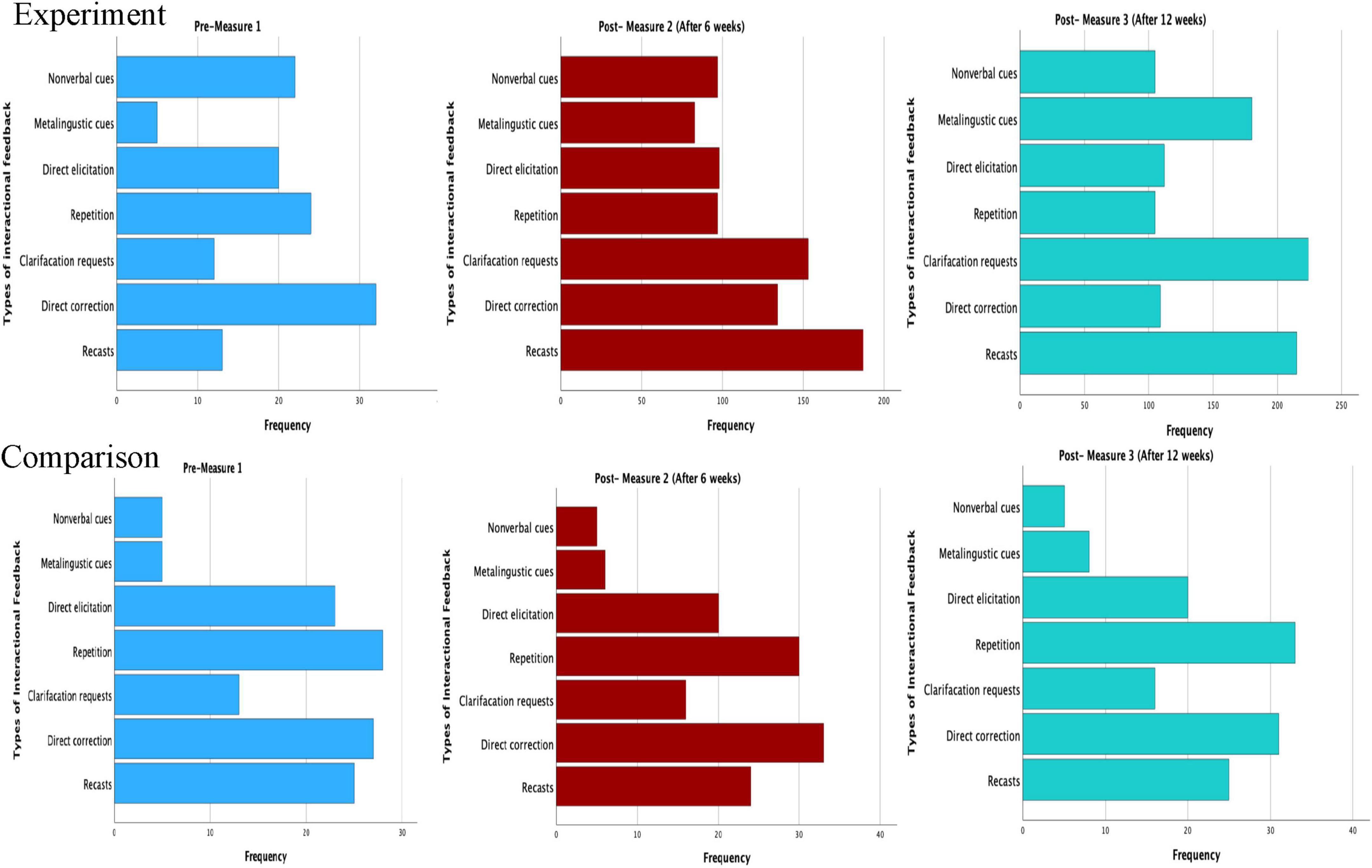

As shown in Table 4, the types of interactional feedback implemented by experimental and comparison group teachers during digital game-based language learning – which improved over three time points-include: recasts (20.5%), clarification requests (21.3), metalinguistic cues (17.1%), Direct elicitation (10.7%), Repetition (10.0%), and Non-verbal cues (10.0%).

Additionally, the results indicate that experimental group teachers provided a total of 1,050 instances of interactional feedback during digital game-based language learning. This represents a significant increase from the total of 128 instances at the pre-measurement stage to 849 at post-measurement stage 2 (after 6 weeks), culminating in 1,050 overall.

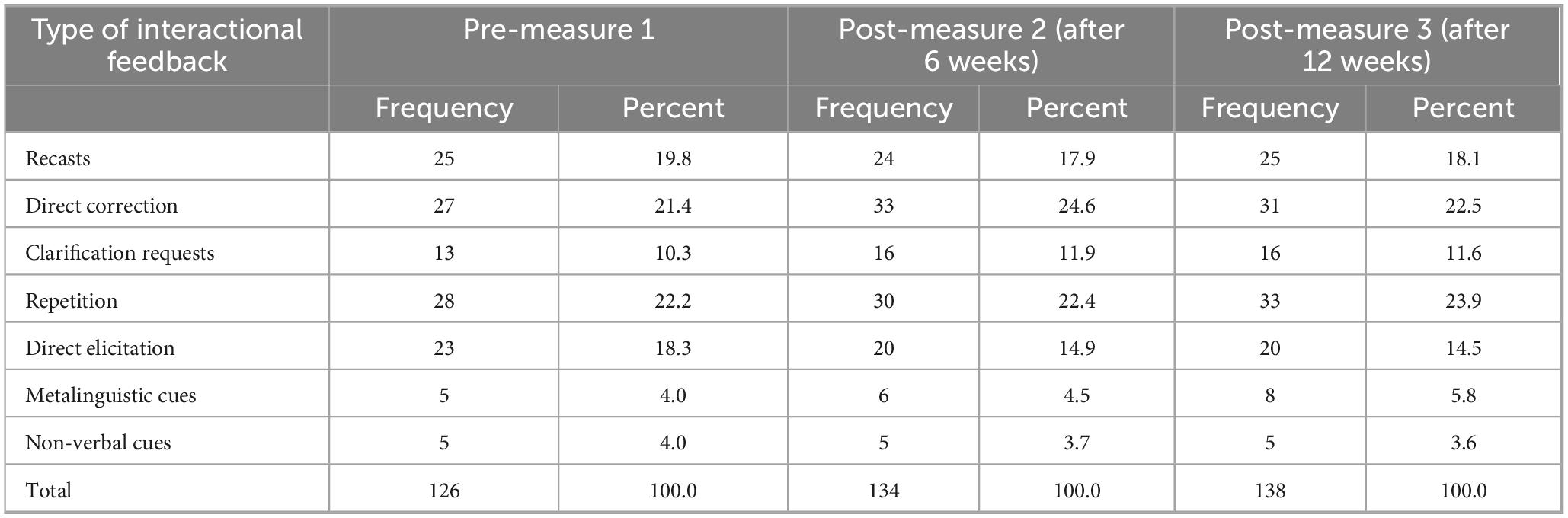

In contrast, as shown in Table 5 the types of interactional feedback implemented by comparison group teachers during regular language learning – were monitored over the same three-time points: repetition (23.9%), direct correction (22.5%), recasts (18.1), direct elicitation (14.5%), clarification requests (11.6%), metalinguistic cues (10.0%), and non-verbal cues (3.6%).

Furthermore, the results show no notable improvement in the comparison group teachers’ use of interactional feedback during regular language learning. This number of instances increased only slightly, from a total of 126 at the pre-measurement stage to 134 at post-measurement 2 (after 6 weeks), with a total of just 138 instances overall.

An examination of the bar charts in Figure 5, which illustrate the types of interactional feedback used by experimental group teachers, indicates that interactional feedback effectively supports digital game-based language learning. In contrast, the limited use of interactional feedback by comparison group indicates that traditional language instruction does not integrate or benefit from such strategies as effectively.

Figure 5. Type of interactional feedback across the three time points between teachers’ experimental and comparison groups.

Teachers in the experimental group generally utilized all types of interactional feedback, indicating that digital game-based language learning can effectively incorporate a wide range of interactional feedback strategies. A closer examination of the frequency and percentage scores revealed that the most notable improvements were found in clarification requests (21.3%), recasts (20.5%), and metalinguistic cues (17.1%). In contrast, analysis of the comparison group’s data revealed that teachers predominantly relied on repetition (23.9%) and direct correction (22.5%), with limited variation in the feedback strategies employed.

Qualitative results

This section addresses the third research question regarding the pre-and post-intervention conceptions of interactional feedback among experimental group teachers (R4). This examination is based on data gathered from qualitative interview analysis.

The pre-and post-intervention conceptions of interactional feedback among experimental group teachers

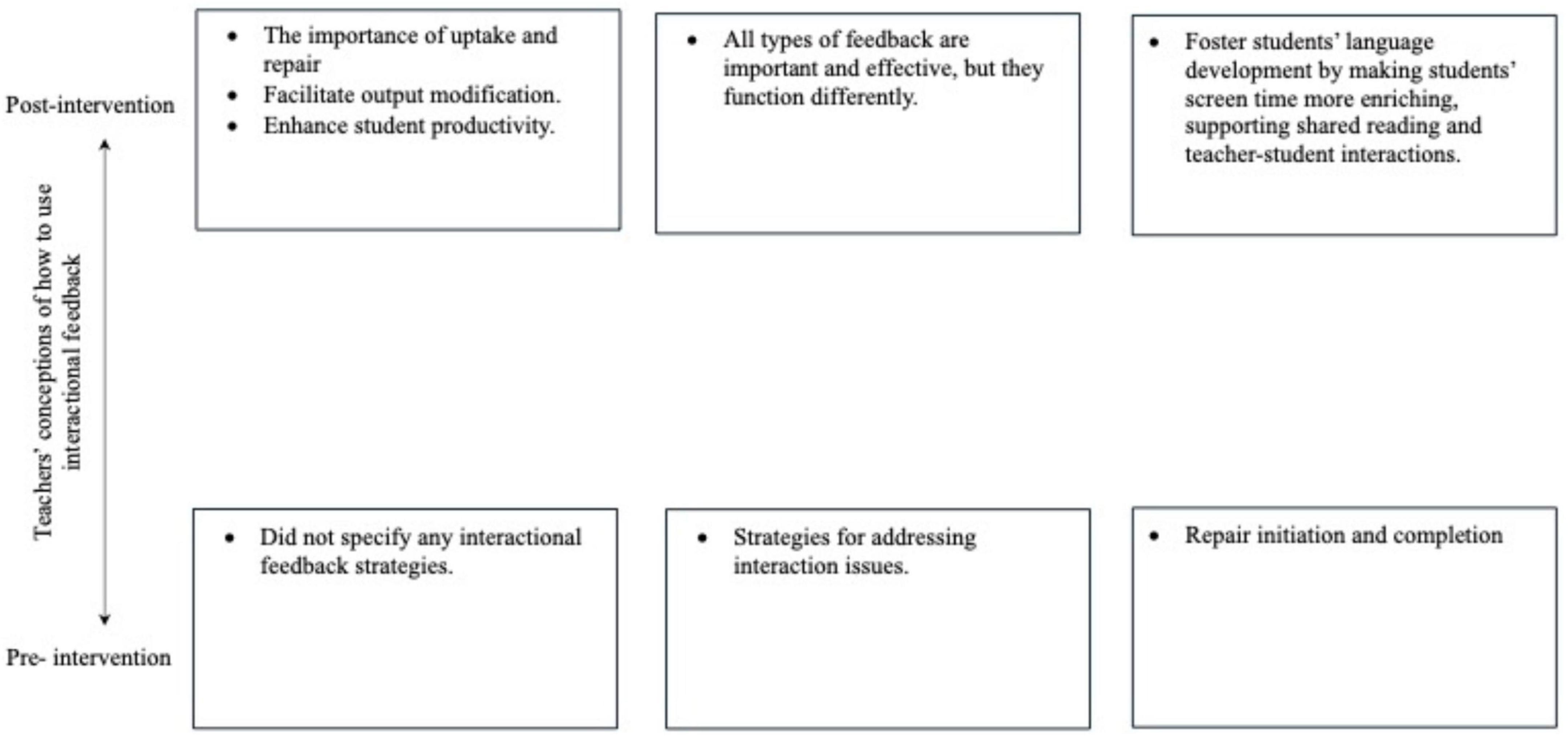

The qualitative results of conceptions of interactional feedback among experimental teachers group generally aligned with their practices as indicated by the quantitative results. The teachers’ conceptions of interactional feedback within the experimental group are summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Teachers’ conceptions of how to use interactional feedback to support digital game-based language learning.

In the pre-intervention interview, teachers in the experimental group did not specify any interactional feedback strategies they had for digital game-based language learning. They recognized that these strategies should be used to address issues arising during interaction. However, Faisal claimed that identifying who initiates the repairs and who completes them would enhance the effective use of interactional feedback strategies. He stated:

“Before using interactional feedback to support digital game-based language learning, I would first think that it is important to know whether the teacher or the students themselves initiate the repair and who completes it. I mean, who should do that?” (pre-intervention interview, L.21–29).

In the post-intervention interview, teachers indicated that learner uptake shows that students have noticed the feedback, which is essential in digital game-based language learning. They also observed that uptake provides evidence of modified output and demonstrated that learners benefited from interactional feedback. For example, Mansour stated that “the insights learners gained from a lesson serve as valuable indicators of the effectiveness of interactional feedback in enhancing digital game-based language learning.” Similarly, Khaled discussed advancing to the next level in digital games, where learners were scaffolded by utilizing the various forms of interactional feedback provided by teachers. Tarek discovered that learners exhibited varying degrees of language acquisition, which depended on the nature of the lesson and the types of activities they engaged in during digital game-based language learning.

Naser and Fahed emphasized the importance and value of using a variety of interactional feedback to support digital game-based language learning, suggesting that multiple types facilitate output modification and enhance student productivity. Naser used the term “output modification” and stated that “a learner’s response is successfully modified when the correction of the learner’s erroneous output is followed and facilitated by a variety of teachers’ interactional feedback.” Fahed used the term “student productivity” to describe when a learner’s response results in successful output.

In total, the importance and benefits of using interactional feedback to support digital game-based language learning are significant. All types of feedback are important and effective, but they function differently. For example, Bander, Marwan, and Salem indicated that they found that recasts were most effective for vocabulary and pronunciation, while Hussain, Tarek, and Youssef identified them as most effective for writing. Additionally, Assaf, Foad, Grant, Hamed, and Tony found that direct elicitations were most effective for learning grammar. Andres, Yasser, and Talal indicated that they found clarification requests and metalinguistic cues were most effective for reading.

Furthermore, In the post-intervention interview, teachers claimed that interactional feedback helped learners use digital games in a way that fostered their language development by making students’ screen time more enriching, supporting shared reading and teacher-student interactions. Monther said, “I know not all digital games are necessarily bad, but I used to wonder how my students are using digital games together. After this intervention, I see my students learning more from media when we join in, which highlights the importance of interactional feedback in supporting the use of digital games in learning.”

Discussion

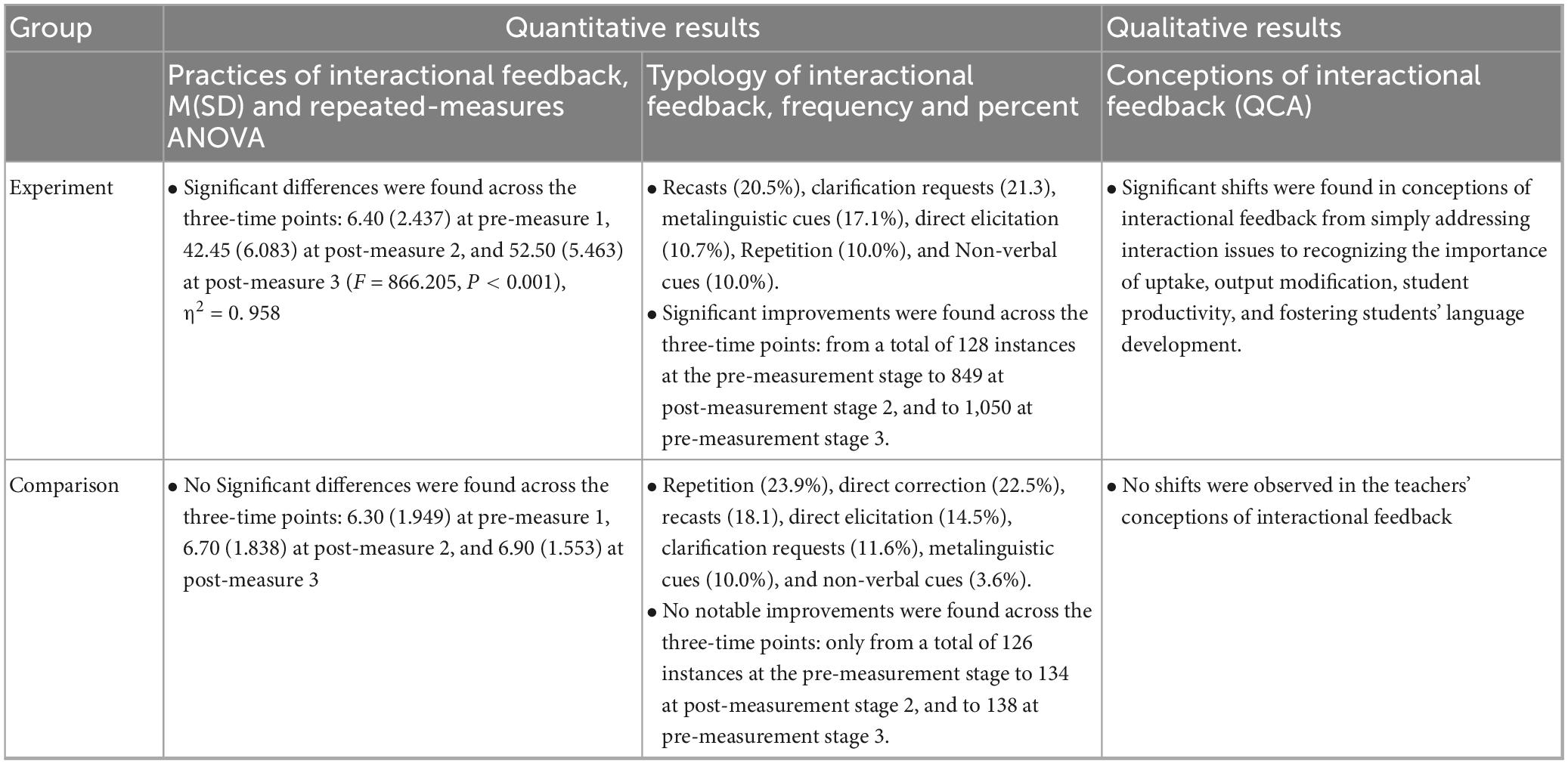

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of teachers’ interactional feedback in supporting digital game-based language learning. This was addressed through Research Question 1 (RQ1) and Question 2 (RQ2). Additionally, the study examined the types of interactional feedback strategies implemented by experimental and comparison groups of teachers, as explored in Research Question 3 (RQ3). Lastly, it investigated the experimental group teachers’ conceptions of how to use interactional feedback to support digital game-based learning, as addressed in Research Question 4 (RQ4). Below, Table 6 summarizes the quantitative and qualitative results for each component: effectiveness, typology, and conceptions.

The quantitative findings indicate that interactional feedback significantly support digital game-based language learning. Teachers in the experimental group employed a variety of interactional feedback, indicating the effective integration of interactional feedback strategies in this context. Notably, the analysis of the frequency and percentage scores revealed significant improvements in clarification requests, recasts, and metalinguistic cues. While previous studies consistently highlight the effectiveness of feedback in digital game-based learning (Benton et al., 2018; Erhel and Jamet, 2013; Yang and Lu, 2021); however, much of the existing research focus on feedback designed primarily to achieve correct answers (Mao et al., 2024). This study addresses this gap emphasizing the importance of interactional feedback, which manifests through various negotiation and conversational strategies such as reformations, elicitations, clarification requests, recasts, and metalinguistic cues. In contrast, the results show no notable improvement in the comparison group teachers’ use of interactional feedback during regular language learning and teachers predominantly relied on repetition and direct correction, with limited variation in feedback strategies. There are also several potential explanations for the findings uncovered in this study. Aligned with established notions regarding the characteristics of a digital game, the researcher employed a digital game that allowed students to interact, communicate, and play as a team, engaging them as active participants. Additionally, the game provided teachers with the opportunity to offer feedback in the form of recasting and negotiation, where it felt organic and fitting. Collazos et al. (2014) stated that active participation, engagement, and interaction are crucial strategies for enhancing learning when using digital tools. Moreover, using the digital game could have influenced the findings regarding teachers’ interactional feedback, potentially attributable to a novelty effect. Some researchers have documented that student learning fluctuates and diminishes as the novelty effect of digital games diminishes (Tsay et al., 2020), whereas others have reported that implementation of digital game-based learning tends to enhance learning and learner engagement while reducing learning anxiety over time (Chen et al., 2021).

The qualitative results regarding teachers’ conceptions of interactional feedback among experimental group in supporting digital game-based language learning showed significant improvement from the pre-intervention phase to the post-intervention phase. Initially, teachers did not specify any interactional feedback strategies and focused on strategies for addressing interaction issues, as well as repair initiation and completion. In contrast, post-intervention conceptions included the importance of uptake and repair, facilitating output modification, enhancing student productivity, recognizing that all types of interactional feedback are important and effective but function differently, and fostering students’ language development by making their screen time more enriching while supporting shared reading and teacher-student interactions. These findings align with the theories advocated by various proponents. Pereira de Aguiar et al. (2018) indicated that when a digital game incorporates player interaction, it provides a positive experience throughout the game. Similarly, Whitton (2014) noted that digital games are effective for inspiring students who are driven by a strong desire for achievement, as these games are often used in social and interactional contexts where players engage in competitive or collaborative problem-solving or take turns playing. The findings also align with those of scholars who have suggested that feedback and interaction within the digital game prompt reflection, guide player attention, and enhance learning (Hense and Mandl, 2014). Additionally, digital games can inspire active participation among teachers in guiding digital game-based learning (Beavis et al., 2014).

In broader perspective, there has been limited research focused on the effectiveness of interactional feedback in enhancing digital game-based language learning. Moreover, there is a noticeable gap in research regarding the exploration of different types of interactional feedback within this specific context. While recent studies have primarily concentrated on either written or oral direct corrections (Rassaei, 2015; Reynolds and Kao, 2021; Shintani and Ellis, 2015), the current study adopts a more comprehensive approach by examining various forms of interactional feedback, such as reformations, elicitations, clarification requests, recasts, and metalinguistic cues. The goal of this investigation is to uncover both the effectiveness and the typology of interactional feedback in facilitating digital game-based language learning. Additionally, the study presents an innovative predictive framework that outlines the stages of interactional feedback cycles in this context.

The findings also have potential implications for the design of practice. While numerous instructional design theorists advocate for allowing students to practice acquired skills and knowledge, the majority neglect to address the design of interactive practice (Zhao et al., 2022). The findings of this study suggest that instructional digital game designers can provide students with interactive practice alternatives that are more effective than traditional methods of using digital games in instruction. The current study also suggests that instructional digital game designers should incorporate teachers’ interactional feedback into their instructional strategies. Such feedback will not only bolster the teacher’s role in guiding digital game-based learning but also enhance student learning. Therefore, future studies should explore the typology of feedback that could be used in digital game-based learning to support learning and teaching in other language disciplines.

Conclusion

This mixed-method experimental study was conducted at the primary school level, where Arabic language teachers used interactional feedback to support digital game-based language learning. The findings indicated that digital game-based language learning was significantly supported by teachers’ interactional feedback. Digital game-based learning seems to be an effective teaching method applicable across various subjects and educational levels. Although further research is warranted to explore the use of different types of digital games across various subjects, the suggested benefits to teachers’ interactional feedback underscore the importance of educators being aware of this instructional method. In this digital age of advanced gaming, education must capitalize on the available digital games as they increase student motivation and foster improved learning outcomes.

Any research study design inherently encompasses both limitations and implications. This study’s limitations are justified by the nature of experimental research. One limitation is the sample of primary schools, which may affect generalizability to other educational stages. However, this is balanced by the random assignment of teachers to participate in the study. Another constraint is connected to the limited sample size. Findings derived from data collected from 20 teachers in the experimental group and 20 teachers in the comparison group may not be generalizable to the teachers in other contexts. This was acknowledged at the beginning of the study; however, the aim was to explore the effectiveness and typology of teachers’ interactional feedback in supporting digital game-based language learning rather than to generalize findings.

Despite certain limitations, the findings offer valuable implications for promoting interactional feedback through digital game-based learning (DGBL) among teachers. Professional development programs should prioritize equipping educators and learners with the pedagogical strategies associated with digital game-based learning. To convincingly integrate DGBL into classroom teaching, it is crucial to comprehend teachers’ interactional feedback and how it aligns with language learning. Implications are also proposed for policymakers responsible for shaping the formal framework for digital game-based learning to establish clear and feasible policies to ensure its successful implementation. These policies should specify the types of interactional feedback teachers should provide and outline how educators can develop the necessary knowledge and skills to integrate DGBL into their teaching practices effectively. The findings of this study indicate that PD programs should facilitate the enhancement of teachers’ ability in utilizing interactional feedback to support DGBLL. Furthermore, these programs should offer opportunities for teachers to explore diverse methods of incorporating interactional feedback into DGBLL classroom instruction. Continued research in this domain is essential to adequately prepare teachers for effective integration of interactional feedback in their pedagogical practices.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research work was funded by the Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia under grant number: 25UQU4282302GSSR01.

Acknowledgments

We extends his appreciation to Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through grant number: 25UQU4282302GSSR01.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Abdul Ghani, M. T., Hamzah, M., Wan Daud, W. A. A., and Muhamad Romli, T. R. (2022). The impact of mobile digital game in learning arabic language at tertiary level. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 14:e44. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/11480

Ağaoğlu, A., and Şad, S. N. (2020). Investigation of the relationship between digital game addiction and English listening skills among university students. Int. J. Acad. Res. Educ. 6, 1–15. doi: 10.17985/ijare.795676

All, A., Castellar, E. P. N., and Van Looy, J. (2016). Assessing the effectiveness of digital game-based learning: Best practices. Comp. Educ. 92, 90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.007

Anastasiadis, T., Lampropoulos, G., and Siakas, K. (2018). Digital game-based learning and serious games in education. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Res. Eng. 4, 139–144. doi: 10.31695/IJASRE.2018.33016

Beavis, C., Rowan, L., Dezuanni, M., McGillivray, C., O’Mara, J., Prestridge, S., et al. (2014). Teachers’ beliefs about the possibilities and limitations of digital games in classrooms. E-learn. Dig. Med. 11, 569–581. doi: 10.2304/elea.2014.11.6.569

Behnamnia, N., Kamsin, A., Ismail, M. A. B., and Hayati, S. A. (2023). A review of using digital game-based learning for preschoolers. J. Comp. Educ. 10, 603–636. doi: 10.1007/s40692-022-00240-0

Benton, L., Vasalou, A., Berkling, K., Barendregt, W., and Mavrikis, M. (2018). “A critical examination of feedback in early reading games,” in Proceedings of the 2018 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, (New York, NY: ACM).

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Buchari, K. (2022). Teacher’s recast and corrective feedback in classroom interaction. J. English Teach. Ling. 3, 87–97. doi: 10.55616/jetli.v3i2.339

Castillo-Cuesta, L. (2020). Using digital games for enhancing EFL grammar and vocabulary in higher education. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. (IJET) 15, 116–129. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i20.16159

Chanel, G., Kivikangas, J. M., and Ravaja, N. (2012). Physiological compliance for social gaming analysis: Cooperative versus competitive play? Interact. Comp. 24, 306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.intcom.2012.04.012

Chen, C.-H., Shih, C.-C., and Law, V. (2020). The effects of competition in digital game-based learning (DGBL): A meta-analysis. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 1855–1873. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09794-1

Chen, P.-Y., Hwang, G.-J., Yeh, S.-Y., Chen, Y.-T., Chen, T.-W., and Chien, C.-H. (2021). Three decades of game-based learning in science and mathematics education: An integrated bibliometric analysis and systematic review. J. Comp. Educ. 9, 455–476. doi: 10.1007/s40692-021-00210-y

Clark, D. B., Tanner-Smith, E. E., and Killingsworth, S. S. (2016). Digital games, design, and learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 79–122. doi: 10.3102/0034654315582065

Coleman, T. E., and Money, A. G. (2020). Student-centred digital game–based learning: A conceptual framework and survey of the state of the art. Higher Educ. 79, 415–457. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00417-0

Collazos, C. A., Padilla-Zea, N., Pozzi, F., Guerrero, L. A., and Gutierrez, F. L. (2014). Design guidelines to foster cooperation in digital environments. Technol. Pedagogy Educ. 23, 375–396. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2014.943277

Creswell, J. W. (2021). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Edmondson, W. J., House, J., and Kadar, D. Z. (2023). Expressions, speech acts and discourse: A pedagogic interactional grammar of English. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R., Sheen, Y., Murakami, M., and Takashima, H. (2008). The effects of focused and unfocused written corrective feedback in an English as a foreign language context. System 36, 353–371. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2008.02.001

Eltahir, M. E., Alsalhi, N. R., Al-Qatawneh, S., AlQudah, H. A., and Jaradat, M. (2021). The impact of game-based learning (GBL) on students’ motivation, engagement and academic performance on an Arabic language grammar course in higher education. Educ. Inform. Technol. 26, 3251–3278. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10396-w

Erhel, S., and Jamet, E. (2013). Digital game-based learning: Impact of instructions and feedback on motivation and learning effectiveness. Comp. Educ. 67, 156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.02.019

Erickson, L. V., and Sammons-Lohse, D. (2021). Learning through video games: The impacts of competition and cooperation. E-Learn. Dig. Med. 18, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/2042753020949983

Esteban, A. J. (2024). Theories, principles, and game elements that support digital game-based language learning (DGBLL): A systematic review. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 23, 1–22. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.23.3.1

Ford, C. E., and Mori, J. (1994). Causal markers in Japanese and English conversations: A cross-linguistic study of interactional grammar. Pragmatics. Quar. Publication Int. Pragmat. Assoc. (IPRA) 4, 31–61. doi: 10.1075/prag.4.1.03

Foster, A., and Shah, M. (2020). Principles for advancing game-based learning in teacher education. J. Dig. Learn. Teach. Educ. 36, 84–95. doi: 10.1080/21532974.2019.1695553

Gao, J., and Ma, S. (2019). The effect of two forms of computer-automated metalinguistic corrective feedback. Lang. Learn. Technol. 23, 65–83. doi: 10.64152/10125/44683

Goldberg, A. E. (2009). The nature of generalization in language. Cogn. Ling. 20, 93–127. doi: 10.1515/COGL.2009.005

Gros, B. (2007). Digital games in education: The design of games-based learning environments. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 40, 23–38. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2007.10782494

Hense, J., and Mandl, H. (2014). Learning in or with games? Quality criteria for digital learning games from the perspectives of learning, emotion, and motivation theory. Berlin: Springer.

Huizenga, J., Ten Dam, G. T., Voogt, J., and Admiraal, W. (2017). Teacher perceptions of the value of game-based learning in secondary education. Comp. Educ. 110, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.03.008

Kickmeier-Rust, M. D., Marte, B., Linek, S., Lalonde, T., and Albert, D. (2008). “The effects of individualized feedback in digital educational games,” in Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on Games Based Learning, (Barcelona: Academic Publishing Limited).

Laakso, N. L., Korhonen, T. S., and Hakkarainen, K. P. (2021). Developing students’ digital competences through collaborative game design. Comp. Educ. 174:104308. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104308

Laurillard, D. (2016). Learning number sense through digital games with intrinsic feedback. Aus. J. Educ. Technol. 32, 1–14. doi: 10.14742/ajet.3116

Lee, H. E., Kim, J. Y., and Kim, C. (2022). The influence of parent media use, parent attitude on media, and parenting style on children’s media use. Children 9:37. doi: 10.3390/children9010037

Liu, L. A., and Hwang, G. J. (2024). Effects of metalinguistic corrective feedback on novice EFL students’ digital game-based grammar learning performances, perceptions and behavioural patterns. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 55, 687–711. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13400

Lyster, R., and Mori, H. (2006). Interactional feedback and instructional counterbalance. Stud. Sec. Lang. Acquis. 28, 269–300. doi: 10.1017/S0272263106060128

Lyster, R., Saito, K., and Sato, M. (2013). Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Lang. Teach. 46, 1–40. doi: 10.1017/S0261444812000365

Mackey, A., and Oliver, R. (2002). Interactional feedback and children’s L2 development. System 30, 459–477. doi: 10.1016/S0346-251X(02)00049-0

Mackey, A., Gass, S., and McDonough, K. (2000). How do learners perceive interactional feedback? Stud. Sec. Lang. Acquis. 22, 471–497. doi: 10.1017/S0272263100004022

Mao, P., Cai, Z., Wang, Z., Hao, X., Fan, X., and Sun, X. (2024). The effects of dynamic and static feedback under tasks with different difficulty levels in digital game-based learning. Int. High. Educ. 60:100923. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2023.100923

Mathers, S. J., Kolancali, P., Jelley, F., Singh, D., Hodgkiss, A., Booton, S. A., et al. (2025). Features of digital media which influence social interactions between adults and children aged 2 to 7 years during joint media engagement: A multi-level meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 46:100665. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2025.100665

Monteiro, K. (2014). An experimental study of corrective feedback during video-conferencing. Lang. Learn. Technol. 18, 56–79. doi: 10.64152/10125/44384

Mushin, I., Blythe, J., Dahmen, J., De Dear, C., Gardner, R., Possemato, F., et al. (2023). Towards an interactional grammar of interjections: Expressing compassion in four Australian languages. Aus. J. Ling. 43, 158–189. doi: 10.1080/07268602.2023.2244442

Nassaji, H. (2015). The interactional feedback dimension in instructed second language learning: Linking theory, research, and practice. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Assessing the effectiveness of interactional feedback for L2 acquisition: Issues and challenges. Lang. Teach. 53, 3–28. doi: 10.1017/S0261444819000375

Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. England: Routledge.

Paulus, F. W., Joas, J., Friedmann, A., Fuschlberger, T., Möhler, E., and Mall, V. (2024). Familial context influences media usage in 0-to 4-year old children. Front. Public Health 11:1256287. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1256287

Pekarek Doehler, S., and Eskildsen, S. W. (2022). Emergent L2 grammars in and for social interaction: Introduction to the special issue. Modern Lang. J. 106, 3–22. doi: 10.1111/modl.12759

Pereira de Aguiar, M., Winn, B., Cezarotto, M., Battaiola, A. L., and Varella Gomes, P. (2018). “Educational digital games: A theoretical framework about design models, learning theories and user experience. design, user experience, and usability: Theory and practice,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference, DUXU 2018, Held as Part of HCI International 2018, (Las Vegas, NV).

Rachayon, S., and Soontornwipast, K. (2019). The effects of task-based instruction using a digital game in a flipped learning environment on English oral communication ability of Thai undergraduate nursing students. English Lang. Teach. 12, 12–32. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n7p12

Rassaei, E. (2015). Oral corrective feedback, foreign language anxiety and L2 development. System 49, 98–109. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2015.01.002

Ravyse, W. S., Seugnet Blignaut, A., Leendertz, V., and Woolner, A. (2017). Success factors for serious games to enhance learning: A systematic review. Vir. Real. 21, 31–58. doi: 10.1007/s10055-016-0298-4

Reynolds, B. L., and Kao, C.-W. (2021). The effects of digital game-based instruction, teacher instruction, and direct focused written corrective feedback on the grammatical accuracy of English articles. Comp. Assis. Lang. Learn. 34, 462–482. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2019.1617747

Salgarayeva, G. I., Iliyasova, G. G., Makhanova, A. S., and Abdrayimov, R. T. (2021). The effects of using digital game based learning in primary classes with inclusive education. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 10, 450–461. doi: 10.17116/kurort20219806139

Sheen, Y., and Ellis, R. (2011). “Corrective feedback in language teaching,” in Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, ed. E. Hinkel (England: Routledge), 593–610.

Shintani, N., and Ellis, R. (2015). Does language analytical ability mediate the effect of written feedback on grammatical accuracy in second language writing? System 49, 110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2015.01.006

Shintani, N., Ellis, R., and Suzuki, W. (2014). Effects of written feedback and revision on learners’ accuracy in using two English grammatical structures. Lang. Learn. 64, 103–131. doi: 10.1111/lang.12029

Tang, X., and Taguchi, N. (2021). Digital game-based learning of formulaic expressions in second language Chinese. Modern Lang. J. 105, 740–759. doi: 10.1111/modl.12725

Tashakkori, A., Johnson, R. B., and Teddlie, C. (2020). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Teddlie, C., and Tashakkori, A. (2021). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). “Thematic analysis,” in The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology, eds C. Willig and W. S. Rogers (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd), 17–36.

Tsay, C. H. H., Kofinas, A. K., Trivedi, S. K., and Yang, Y. (2020). Overcoming the novelty effect in online gamified learning systems: An empirical evaluation of student engagement and performance. J. Comp. Assis. Learn. 36, 128–146. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12385

Tzuo, P.-W., Ling, J., Yang, C.-H., and Chen, V. H.-H. (2012). Reconceptualizing pedagogical usability of and teachers’ roles in computer game-based learning in school. Educ. Res. Rev. 7, 419–429. doi: 10.5897/ERR11.072

Wang, Q. (2020). The role of classroom-situated game-based language learning in promoting students’. Commun. Competence Int. J. Computer-Assisted Lang. Learn. Teach. (IJCALLT) 10, 59–82. doi: 10.4018/IJCALLT.2020040104

Wiltschko, M. (2021). The grammar of interactional language. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Yang, K.-H., and Lu, B.-C. (2021). Towards the successful game-based learning: Detection and feedback to misconceptions is the key. Comp. Educ. 160:104033. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104033

Yousefi, M., and Nassaji, H. (2021). Corrective feedback in second language pragmatics: A review of research. Tesl-Ej 25, 1–14.

Yu, Y.-T., and Tsuei, M. (2023). The effects of digital game-based learning on children’s Chinese language learning, attention and self-efficacy. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31, 6113–6132. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2022.2028855

Zhao, H., and MacWhinney, B. (2018). The instructed learning of form–function mappings in the English article system. Modern Lang. J. 102, 99–119. doi: 10.1111/modl.12449

Keywords: teachers, digital games, early years education, language learning, interactional feedback

Citation: Alghamdi A (2025) Investigating the effectiveness and typology of teachers’ interactional feedback in supporting digital game-based language learning. Front. Educ. 10:1645840. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1645840

Received: 21 June 2025; Accepted: 29 October 2025;

Published: 12 November 2025.

Edited by:

Aslina Baharum, Sunway University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Nashwa Ismail, Imperial College London, United KingdomPanicha Nitisakunwut, Mahidol University, Thailand

Copyright © 2025 Alghamdi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdulmajeed Alghamdi, YW1iYWhlc0B1cXUuZWR1LnNh

†ORCID: Abdulmajeed Alghamdi, orcid.org/0000-0002-9271-8823

Abdulmajeed Alghamdi

Abdulmajeed Alghamdi