- Department of Special Education, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Introduction: This study explored the availability, quality, and challenges of transitional services for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in Saudi Arabian middle and high schools, with a particular emphasis on parental perspectives.

Methods: A mixed-methods approach was employed. Researchers first surveyed 301 parents regarding their awareness, involvement, and perceived barriers related to transition services. To deepen understanding, structured interviews were conducted with ten mothers from different regions of Saudi Arabia.

Results: Most parents (65.1%) expressed a desire to participate in transition planning, but only 37.2% reported consistent involvement. Parental recognition of the importance of transition planning was high (79.1%), and 74.4% supported their children’s right to appropriate services. However, only 30.2% strongly agreed they were aware of available services, while 37.2% disagreed, indicating a significant awareness gap. Key barriers identified included poor cooperation among families, schools, and community agencies, lack of standardized planning practices, insufficient policies, and inadequate financial and administrative support. Qualitative interviews revealed additional themes: parental confusion and anxiety about the future, exclusion from planning processes, lack of awareness about educational rights, and significant regional disparities in service provision. Parents described transitional services as fragmented, lacking long-term vision, and often excluding families from meaningful participation.

Discussion: Transitional services for students with ASD in Saudi Arabia are inconsistently implemented and insufficiently designed to promote independence and life skills. The findings highlight an urgent need for policy reforms, greater parental engagement, and coordinated efforts among stakeholders to improve transitional outcomes for students with ASD. The abstract effectively presents quantitative findings from the survey data alongside qualitative themes from the interviews, providing a comprehensive overview of the research outcomes and their implications for policy and practice.

1 Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent challenges in social interaction, communication, and adaptive functioning, which can significantly affect the quality of life for both adolescents and adults (Ayres et al., 2018). Recent data indicate a rising prevalence of ASD globally. For instance, in the United States, approximately 1 in 31 eight-year-olds are diagnosed with ASD (Shaw, 2025). In Saudi Arabia, the most recent data—obtained directly from the Authority for the Care of Persons with Disabilities via official communication—estimate that 34,649 individuals have been identified with ASD, with a substantial proportion classified as severe cases out of a total population of 321,750,224 (Authority of People with Disability, 2024). Given the lifelong impact of ASD, a comprehensive approach encompassing early intervention, Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), and evidence-based transitional services is essential to promote independence and improve long-term outcomes for individuals with ASD (Almalky and Alrasheed, 2023; Findley et al., 2022).

Despite the well-established importance of early and ongoing support, the transition from secondary education to adulthood remains a particularly vulnerable period for students with ASD. Postsecondary transition services are designed to facilitate this process, supporting students with disabilities—including those with ASD—as they move toward higher education, vocational training, employment, or independent living (Findley et al., 2022). However, research demonstrates that students with ASD often encounter unique challenges during this transition, such as disruptions in support services, limited access to individualized transition planning, and insufficient collaboration among stakeholders (Yell et al., 2020; Laxman et al., 2019). These challenges can result in adverse outcomes, including reduced employment opportunities and diminished independence in adulthood (Laxman et al., 2019).

In Saudi Arabia, the effectiveness and consistency of transitional services for students with ASD remain under-examined, particularly from the perspective of parents, who are critical advocates for their children’s educational and developmental needs (Al Awaji et al., 2024). Existing studies have identified systemic barriers, such as inadequate teacher training, limited student-teacher interaction, and poorly structured Individualized Transition Plans (ITPs), which hinder the successful implementation of transition services (Friedman et al., 2013; Alnahdi et al., 2024). Moreover, the lack of comprehensive policies and the influence of cultural and systemic factors further complicate the transition process for students with disabilities (Aldosari and Alzhrani, 2024).

Parental involvement is not only pivotal in the education of children with ASD but also in their lifelong care, underscoring the necessity of their engagement in developing effective support systems. The significance of this research lies in its potential to inform both theory and practice: it advances the conceptual understanding of ASD and transition services, while also providing actionable insights for policymakers, educators, and families. By addressing three central research questions—parents’ perceptions of involvement, barriers to service provision, and parental experiences—this study seeks to inform systemic reforms and enhance the quality and accessibility of transitional support for students with ASD in Saudi Arabia.

This study aims to address these gaps by examining parents’ perspectives on the adequacy of transitional services for students with ASD in Saudi Arabian middle and high schools. Specifically, it seeks to identify key challenges, assess parental involvement, and propose evidence-based recommendations for improvement. Employing a mixed-methods approach and drawing on a diverse sample across various regions, this research contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the current landscape of transitional services.

1.1 The research question

Specifically, the study seeks to:

I. What are parents’ perceptions of their involvement in transitional services for students with ASD in middle and high schools in Saudi Arabia?

II. What are the key barriers to the provision and effective planning of transitional services for these students, as reported by parents?

III. How do parents describe their experiences and perspectives regarding the adequacy, quality, and challenges of current transitional services for students with ASD?

Parents play a crucial and multifaceted role in supporting children with ASD during the transition from school to adulthood, a period marked by significant challenges and stress, particularly for mothers (DaWalt et al., 2018). Parental involvement is consistently identified as a key determinant of successful outcomes, but parents often face barriers such as fragmented service systems, limited access to services, and unclear guidance (Hoffman and Kirby, 2022). These obstacles contribute to parental stress and uncertainty about their children’s futures, especially regarding employment, social integration, and daily living skills (Hoffman and Kirby, 2022).

International literature highlights both barriers and facilitators to effective transition services. In the U. S., parents actively collaborate with teachers and specialists in developing Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) to support smoother transitions (Grünke and Cavendish, 2016), though transition specialists may lack knowledge about post-school outcomes (Snell-Rood et al., 2020). Common barriers globally include limited access to services, employment challenges, social isolation, and insufficient stakeholder involvement (Pillay et al., 2021). A societal approach and collective responsibility are recommended to address these barriers (Hoffman and Kirby, 2022), while specialized training, policy development, and Individualized Transition Plans (ITPs) are effective facilitators (Almalki, 2025).

Studies also note that many students with ASD graduate without essential life skills, affecting their independence and adult preparedness (Lillis and Kutscher, 2021; Gelbar et al., 2014). In China, transportation challenges are a major barrier, and improved collaboration is recommended to foster independent travel skills (Xu et al., 2024). Effective collaboration among parents, educators, and specialists is essential, as shown by Perryman et al. (2020) and Bruck et al. (2022), who emphasize the importance of connecting students with employment, training, and community integration opportunities.

In Saudi Arabia, transition services for students with ASD have existed since 2005 but remain inconsistent, with misaligned objectives and poor communication among stakeholders (Almalki, 2025). The current support system for students with ASD in Saudi Arabia exhibits critical gaps in transition planning, particularly in facilitating meaningful parental involvement and institutional preparedness. Research indicates that parents of children with ASD often face systemic barriers to engagement, including limited awareness of transition processes and insufficient time to participate actively (Almalki et al., 2021). Compounding this issue, schools frequently fail to adopt proactive strategies to involve families or provide comprehensive guidance on post-school pathways, leaving both students and parents inadequately prepared for adulthood (Alfawzan and Almulhim, 2024). This institutional oversight reflects broader deficiencies in Saudi Arabia’s special education policies, which lack standardized transition frameworks comparable to those in western contexts (Alquraini and Rao, 2020; Khasawneh, 2024). Without structured transition programs that incorporate parental training, individualized planning, and inter-agency collaboration, students with ASD risk poor post-school outcomes, including unemployment and social isolation. These findings underscore an urgent need for policy reforms that mandate school-based transition initiatives while empowering families as key stakeholders in the planning process. With that most if research in Saudi Arabia has largely focused on teachers and administrators, with limited empirical attention to parental perspectives or advocacy (Binmahfooz, 2022). Also, Almughyiri (2025) research provides the evidence base necessary for developing targeted interventions. The study identifies specific areas where professional development is needed, allowing educational authorities to allocate resources more effectively and design training programs that address actual rather than perceived deficits. This is significant, as international evidence shows that parental involvement is critical for improving transition outcomes (Taylor et al., 2017). Almalki (2025) and Binmahfooz (2022) both highlight the need for more research on parental advocacy and involvement in shaping effective transition programs in Saudi Arabia.

While efforts to support students with disabilities in their transition from school to adulthood are growing in Saudi Arabia, the services offered still vary widely in quality and consistency across educational and vocational settings. Behind the policies and programs, there are families, educators, and students navigating a system that often lacks the coordination and continuity they need. In one of the early efforts to understand these gaps, Almalky (2018) examined closely how community-based vocational instruction (CBVI) was being utilized to prepare students with intellectual disabilities for real-life opportunities. The study highlighted the great promise of CBVI in helping students build practical skills and find a place in their communities. Yet, it also revealed several roadblocks—like weak links between schools and community partners, a shortage of trained professionals, and minimal parental involvement. These challenges show how structural limitations can prevent well-intentioned programs from reaching their full potential, especially for students with more complex needs, such as those with ASD. Building on this work, (Almalky et al., 2020) turned their attention to families themselves, listening to what they had to say about school-business partnerships meant to ease the postsecondary transition. Families appreciated the idea in principle, but many shared feelings of frustration. The services available did not always match what they had hoped for, and issues such as limited access, a lack of clear communication, and a poor cultural fit made it difficult for parents to engage fully. These stories highlight a pressing need for more inclusive and family-cantered approaches that genuinely meet parents where they are. Taken together, these studies offer an important window into the current landscape of transitional services in Saudi Arabia. They demonstrate that while promising initiatives exist, they are often fragmented and lack the necessary structure to achieve long-term impact. What’s usually missing is a consistent, connected effort that brings together schools, families, communities, and employers in a meaningful way. This current study builds on that foundation by focusing on parental involvement—a factor that can make or break a successful transition. By listening to parents of children with ASD and learning about their experiences, needs, and the obstacles they face, this research adds a much-needed perspective to the national conversation. It helps fill a critical gap in understanding how transitions are experienced on the ground and what must change to support students and families more effectively.

In summary, while international research demonstrates the positive impact of parental advocacy and involvement in transition planning, there is a significant research gap in Saudi Arabia regarding how parents can actively shape and improve transition services. Future studies should prioritize understanding and supporting parental roles within the Saudi context to ensure that transition services are both effective and responsive to the needs of families and individuals with ASD.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design

The study used a sequential explanatory mixed-methods approach to assess the feasibility of transitional services for students with ASD in Saudi middle and high schools. Quantitative data were first collected through a survey of 301 parents, followed by qualitative interviews with ten purposively selected parents to provide deeper insights (Watkins and Gioia, 2015). This design, based on Creswell (2013) framework, allowed the researchers to identify broad statistical patterns and then elaborate on them through participants’ personal experiences. The quantitative phase was grounded in post-positivism, emphasizing objectivity and statistical analysis, while the qualitative phase adopted a constructivist perspective to capture the subjective experiences of parents within their social contexts. The use of follow-up explanations and participant-selection variants further enriched the analysis. By integrating these methodologies, the study delivered a robust and contextually meaningful evaluation of transitional services, capturing both statistical trends and the nuanced challenges faced by parents and students.

2.2 Participants

Participants were randomly selected with help from the Ministry of Education, prominent service providers, and a parent support group in Saudi Arabia. The researcher distributed the survey link through the Ministry of Education, which then shared it with schools enrolling students with ASD to reach parents. Additionally, the survey link was disseminated to parent support groups via platforms such as Facebook and X. The survey, created using Google Forms, included a cover page explaining the study’s purpose and took approximately 15 min to complete. Parents interested in the study received paper consent forms and questionnaires, all in Arabic. Although the researchers aimed to use validated Arabic measures, this was not always possible. Eligibility was limited to parents of children with ASD enrolled in or graduated from middle or high school. Ultimately, 301 parents from various regions completed the online survey, offering a broad perspective on their experiences. The study’s participants were primarily mothers (76.7%), underscoring their central role in managing and evaluating their children’s transition experiences. Fathers and other caregivers each made up 11.6% of the sample. Educationally, respondents were relatively well-educated: 51.2% held a bachelor’s degree, 25.6% had a high school diploma, and 23.3% possessed a graduate degree, which may enhance their awareness and involvement in transitional services. In terms of the age distribution of students with ASD, 48.8% were 15 years or older, 32.6% were ten years or younger, and 18.6% were between 11 and less than 15 years. The predominance of older students aligns with the study’s focus on transition services, as these are most relevant for families preparing for the shift from school to adulthood. This demographic profile supports the study’s objective to capture parental perspectives during the critical period of transition planning.

Quantitative data came from these self-administered questionnaires, while qualitative insights were gathered through interviews with ten parents who had completed the survey and agreed to further participation. A total of ten parents participated in the in-depth interviews. These participants were identified during the first phase of the study, in which all survey respondents were invited to indicate their interest in a follow-up interview. Of the parents who expressed willingness, 23 provided their contact information. From this group, ten parents confirmed their availability and consented to participate in the interview phase. Approximately 40 to 60 min were spent on the interview. This mixed-methods approach enabled a comprehensive assessment of the accessibility and effectiveness of transitional services for students with ASD in Saudi Arabia.

2.3 Data collection instruments

The study employed multiple instruments to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. An online survey (Google platforms) was the primary quantitative tool, developed based on an extensive literature review, including studies by Alnahdi et al. (2024), Alasiri et al. (2024), Aldosari and Alzhrani (2024), and Almalki et al. (2023). To ensure validity, the survey was reviewed by ten faculty members who have expertise in ASD and familiar with the topic addressed in the online survey; and refined based on their feedback. A pilot study with 45 who randomly selected of parents of children with ASD yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90, indicating high internal consistency. The survey consisted of three sections:

I. Demographic Information – Questions on the child’s age, parents’ education level, and their relationship to the child.

II. Perceptions of Transitional Services – Six statements assessing parents’ views on service involvement and awareness

III. Barriers to Transition Planning – Nine questions addressing challenges such as accessibility, awareness, and communication.

2.3.1 Internal consistency and reliability

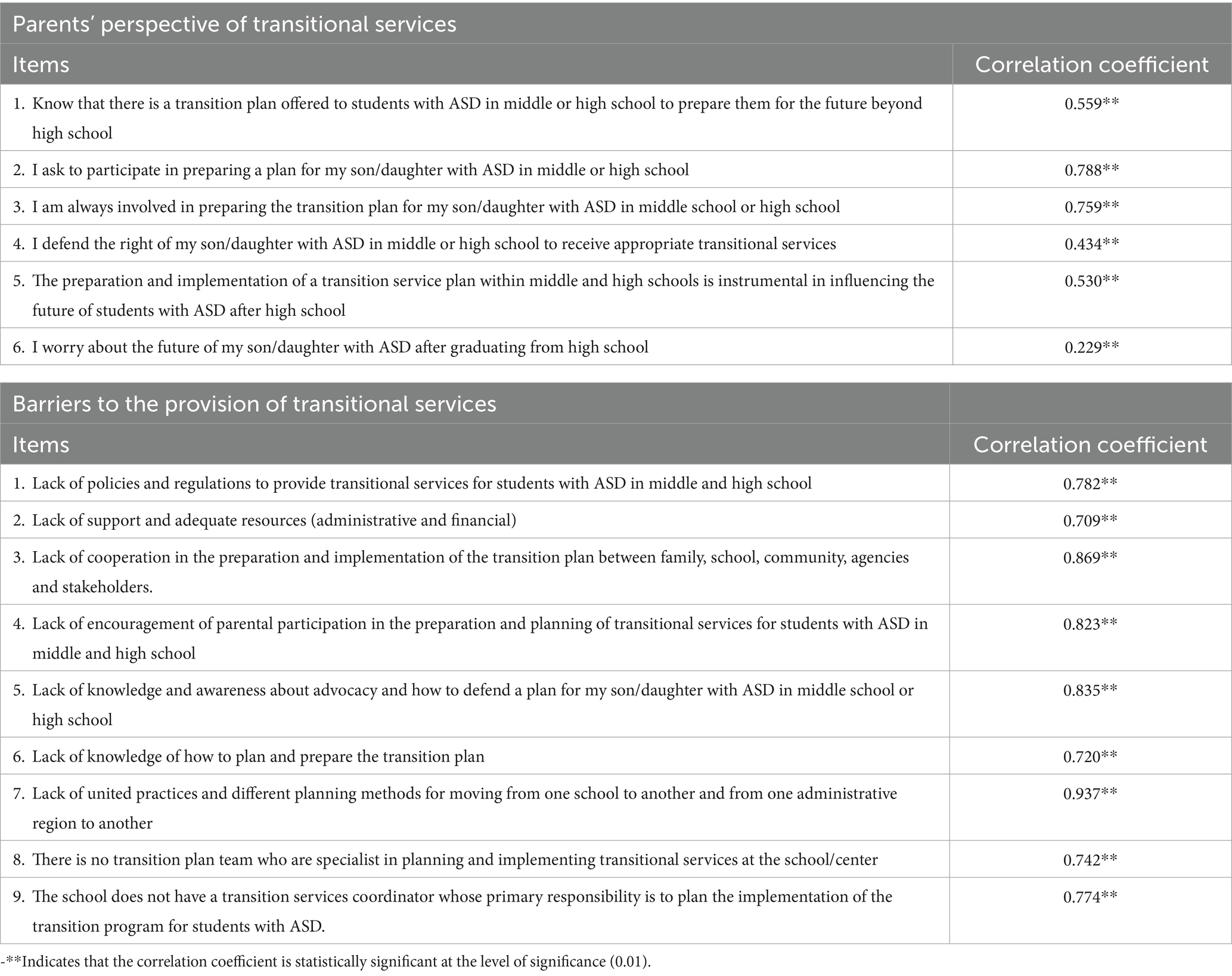

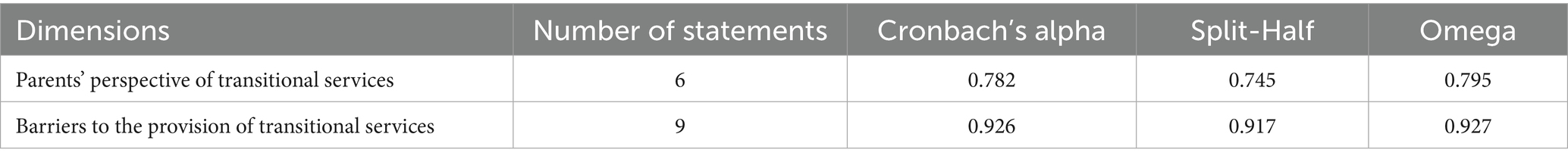

For To evaluate the internal consistency and reliability of the survey instrument, multiple statistical analyses were conducted on both dimensions of the tool: parents’ perspectives on transitional services and perceived barriers to provision, as Table 1. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated for each pair of items within these dimensions to assess the linear relationship between survey responses.

For the dimension assessing parents’ perspectives regarding transitional services, the inter-item correlation coefficients were all statistically significant and positive, indicating coherence among the items. The strongest relationship was found between Item 1 (“Know that there is a transition plan offered to students with ASD in middle or high school to prepare them for the future beyond high school”) and Item 2 (“I ask to participate in preparing a plan for my son/daughter with ASD in middle or high school”), with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.788 (p < 0.01). This suggests that parental awareness of existing transition plans is closely linked to active parental participation in transition planning. In contrast, the weakest (yet statistically significant) correlation emerged between Item 1 and Item 6 (“I worry about the future of my son/daughter with ASD after graduating from high school”), with a coefficient of 0.229 (p < 0.01). This weaker association indicates that simply knowing about transition plans does not markedly reduce parental concerns about long-term outcomes for their children.

Within the barriers dimension, item-to-item correlations were generally higher, reflecting the strong internal interrelatedness of these perceived obstacles. The highest inter-item correlation was observed for Item 7 (“Lack of united practices and different planning methods for moving from one school to another and from one administrative region to another”), which had a coefficient of 0.937 (p < 0.01) with other barrier items, highlighting the central role of systemic inconsistency and fragmentation as a perceived barrier. Additionally, substantial correlations were found between Items 4 (“Lack of encouragement of parental participation in the preparation and planning of transitional services for students with ASD in middle and high school”) and 5 (“Lack of knowledge and awareness about advocacy and how to defend a plan for my son/daughter with ASD in middle school or high school”), with coefficients of 0.823 and 0.835, respectively. These strong relationships underscore the interconnectedness between limited parental involvement and knowledge deficits regarding advocacy.

Table 2 evaluates the reliability and stability of the instrument used to assess parents’ perspectives on transitional services for students with ASD. For the “Parents’ perspective of transitional services” dimension (six items), the reliability coefficients indicate good internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha is 0.782, Split-Half reliability is 0.745, and Omega is 0.795. These values demonstrate that the items consistently measure the same underlying construct, and the tool is stable across different data subsets.

Table 2. The stability factor for the measure of perspective of parents about current transition services for students with ASD.

For the “Barriers to the provision of transitional services” dimension (nine items), the reliability is even stronger. Cronbach’s alpha is 0.926, indicating excellent internal consistency. The Split-Half reliability is 0.917, and the Omega coefficient is 0.927, both reflecting exceptionally high stability and consistency. These results confirm that the instrument provides a coherent and reliable assessment of perceived barriers to transitional services for students with ASD.

2.3.2 Demographic characteristics

In addition to quantitative measures, qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews designed to explore parents’ lived experiences with transitional services in Saudi schools. The interview protocol was validated by five faculty experts specializing in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and consisted of a core question—“What are your lived experiences in supporting your children with ASD during transitional stages?”—supplemented with open-ended follow-up questions for deeper insights. Interviews were audio-recorded to ensure data accuracy and facilitate comprehensive qualitative analysis.

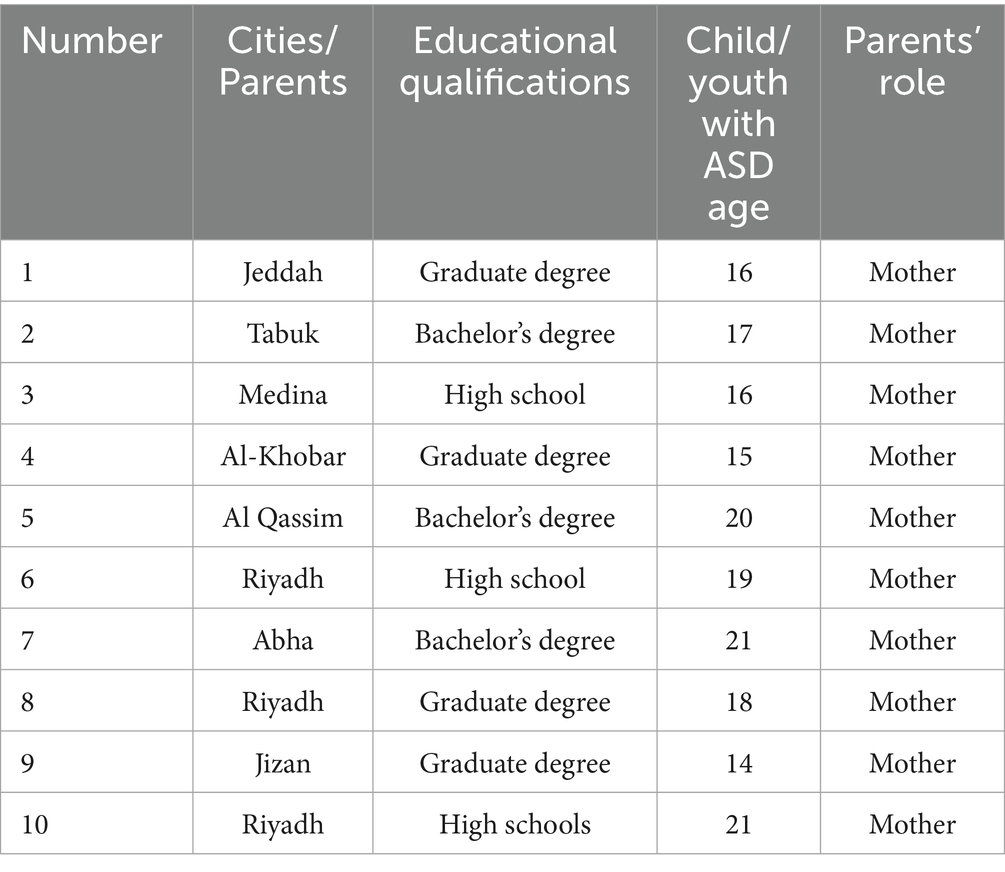

Participant recruitment for the interviews was conducted in coordination with school and centre directors. Eligibility criteria required participants to be the primary caregiver of a child with ASD aged 14 or older, currently enrolled in school or a rehabilitation centre, or a graduate. Participation was voluntary. The sample comprised exclusively mothers (n = 10) from various geographic regions in Saudi Arabia, including Riyadh, Jeddah, Tabuk, Medina, Al-Khobar, Al Qassim, Abha, and Jizan. Educational backgrounds varied, with most mothers holding bachelor’s or graduate degrees (n = 7, combined), and the remainder having completed high school (n = 3). Children’s ages ranged from 14 to 21 years, with several cases representing the transitional age group targeted in this study. Table 3 presents detailed demographic information for the interview participants.

The combined use of validated survey and interview meth ods provided a robust, comprehensive assessment of parents’ perspectives and the barriers encountered in transitional services for students with ASD in the Saudi context.

Researchers conducted face-to-face interviews with mothers in Riyadh and online interviews via Zoom for participants in other cities, addressing geographical constraints. Interview recordings were transcribed from audio to text using an AI-based speech recognition system from Veed.io, which also generated Arabic subtitles (Akasheh et al., 2024). To ensure anonymity, all identifying information was removed, and research assistants proofread the transcripts, with final versions agreed upon through team discussions. Researchers then reviewed the finalized transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data.

2.4 Data collection procedure

The study employed a mixed methods data collection procedure, integrating both quantitative and qualitative approaches to thoroughly examine transitional services for students with ASD in Saudi Arabia. Quantitative data from surveys offered a broad overview of parents’ perceptions and highlighted common barriers, revealing patterns and trends across different regions. In contrast, qualitative data from semi-structured interviews provided deeper, more nuanced insights by allowing parents to share their personal experiences in detail. This triangulation of data sources enriched the findings by contextualizing statistical results with lived experiences. By combining these methods, the researchers delivered a comprehensive and holistic understanding of the challenges in transitional services, ultimately informing recommendations for improvement based on parents’ perspectives.

2.5 Ethical considerations

This research was conducted with ethical approval from King Saud University with number KSU-HE-25-480. Participants were assured of both the privacy and confidentiality of the information they provided. The participants received detailed explanations about the study’s risks and benefits. The participants’ confidentiality was maintained during data collection and analysis, especially for interviews.

2.6 Statistical analysis

In the quantitative phase of this study, a variety of statistical methods were used to ensure rigorous analysis and reliable findings. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies and percentages, summarized the demographic characteristics of the sample (Field, 2018). To compare differences between groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, which is suitable for comparing the means of three or more independent groups and determining if these differences are statistically significant (Field, 2018; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2019). Before conducting ANOVA, Levene’s test was used to assess homogeneity of variances, as violations can affect ANOVA’s validity (Levene, 1960). If unequal variances were found, the Games-Howell post-hoc test was applied, as it is designed for situations with unequal group variances (Games and Howell, 1976). Overall, these statistical methods were chosen to ensure valid group comparisons, robust inferential analyses, and reliable survey data, thereby strengthening the credibility of the study’s findings and supporting evidence-based recommendations.

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative stage

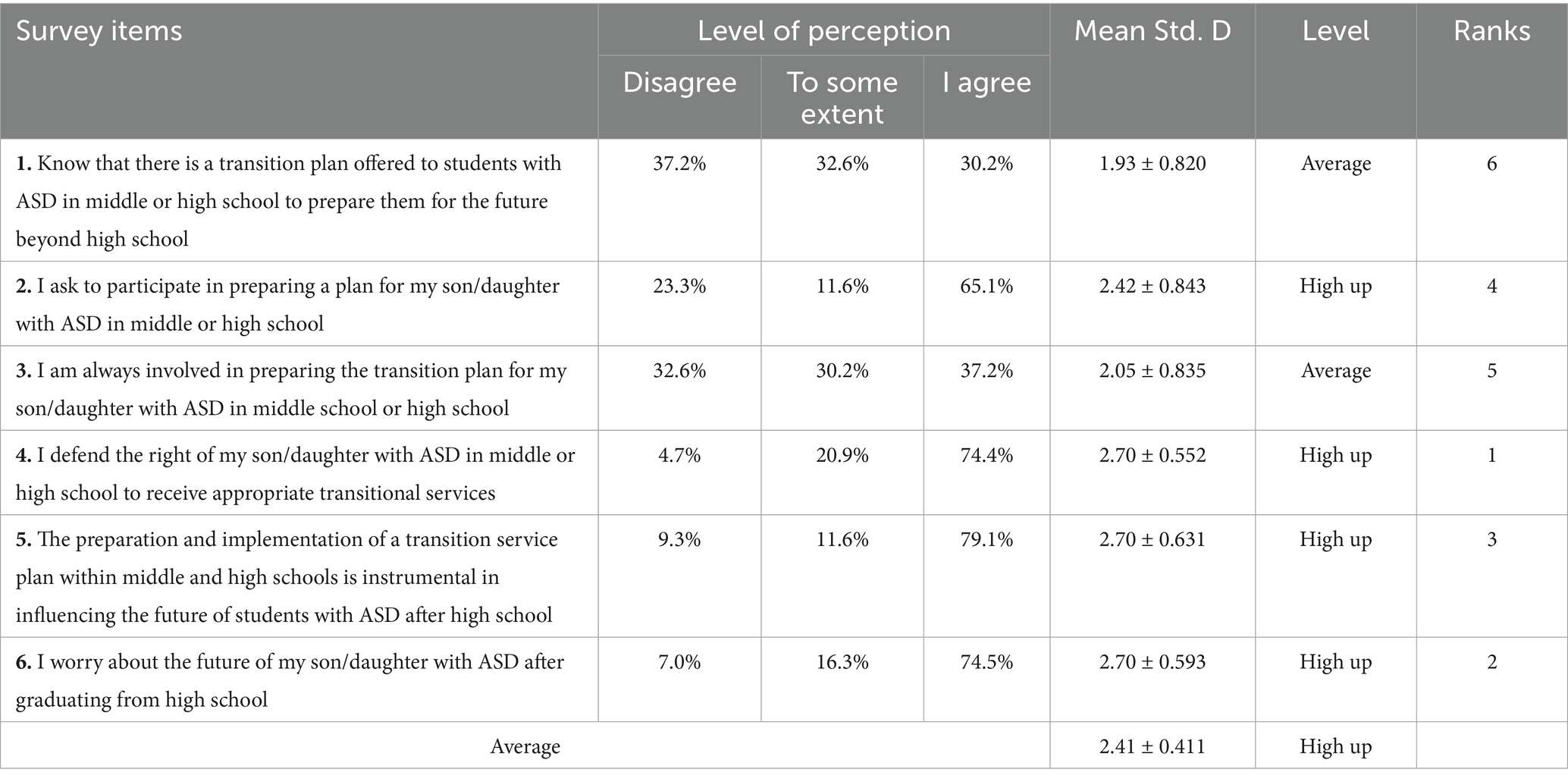

3.1.1 Parental involvement and awareness of transitional Services for Youth with ASD

The key findings from Table 4 reveal that while parents generally hold positive views about transition planning for students with ASD (mean score = 2.41, SD = 0.411), there are significant gaps in awareness and involvement. Most parents (79.1%) strongly believe that transition planning has a major impact on their child’s future, and 74.4% strongly support their child’s right to appropriate transition services. However, although 65.1% of parents expressed a desire to participate in transition planning, only 37.2% reported being consistently involved, indicating a substantial gap between willingness and actual engagement. Additionally, just 30.2% of parents strongly agreed they were aware of existing transition plans, while 37.2% disagreed, pointing to a significant communication shortfall between schools and families. These results highlight the urgent need for better collaboration and clearer communication to ensure parents are both informed about and actively included in the transition planning process for their children with ASD.

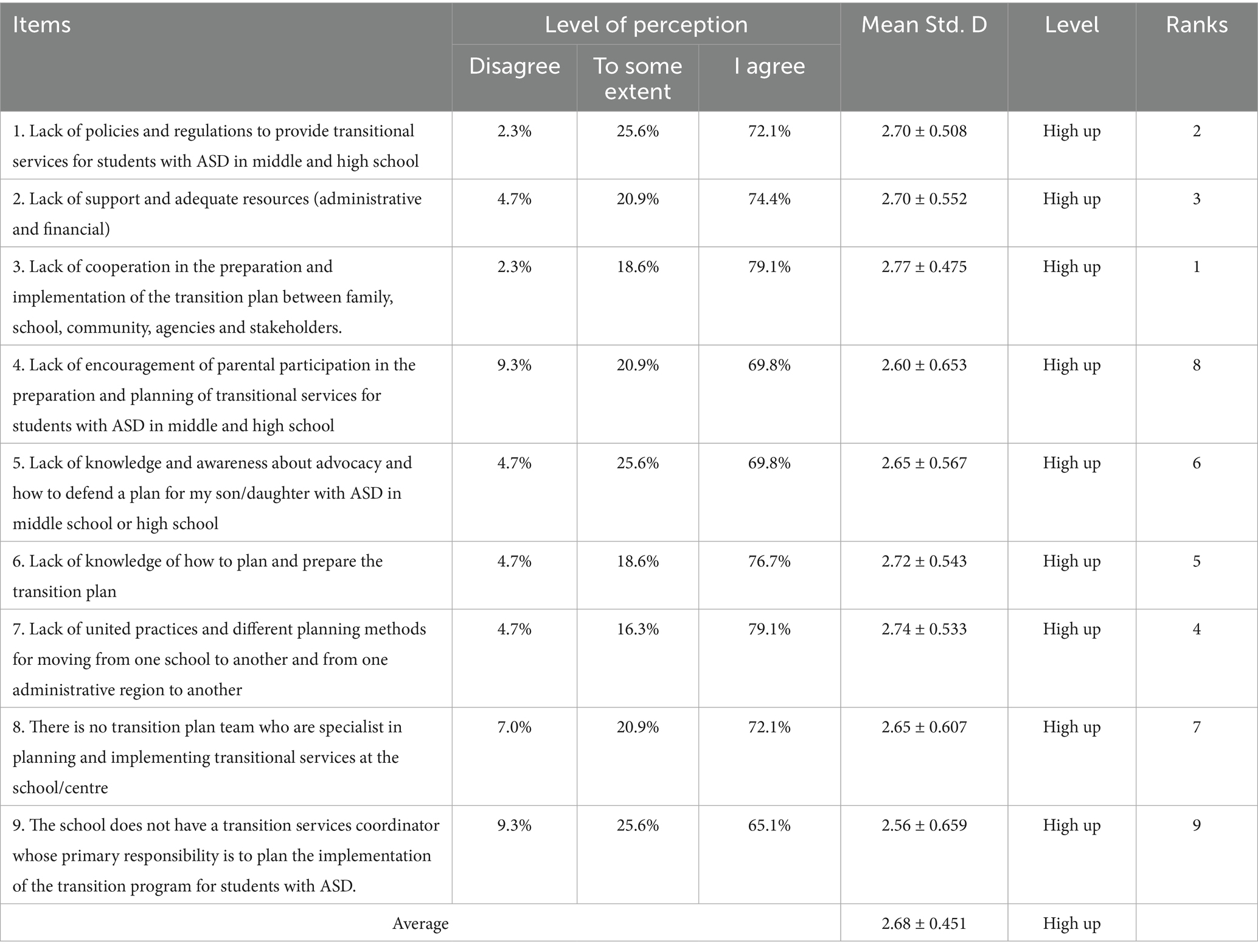

3.1.2 Parents’ perceptions of barriers to transitional services for youth with autism spectrum disorder

Table 5 highlights several significant barriers faced by parents in the planning and delivery of transitional services for students with ASD, with an overall high level of concern (mean = 2.68, SD = 0.451). The most critical barrier identified was the lack of cooperation among families, schools, community agencies, and stakeholders, strongly agreed upon by 79.1% of respondents. Other major obstacles included inconsistent practices across schools and regions (mean = 2.74, SD = 0.533), insufficient policies and regulations (mean = 2.70, SD = 0.508), and inadequate financial and administrative support (mean = 2.70, SD = 0.552).

Additionally, 69.8% of parents reported a lack of encouragement for their participation in transition planning. Many also indicated limited knowledge of advocacy strategies and transition planning processes. Institutional shortcomings, such as the absence of specialized transition teams and coordinators, further impeded effective service delivery. These findings underscore the need for comprehensive systemic reforms to foster collaboration, standardize practices, and strengthen both parental involvement and institutional capacity in transitional services for students with ASD.

3.2 Qualitative phase

3.2.1 Experiences of parents of students with autism spectrum disorder with transitional services in Saudi schools

A pilot interview was conducted with one participant from the quantitative survey phase to refine the interview protocol, leading to adjustments in question order and the addition of probing questions. The themes were derived using Braun and Clarke's (2006) thematic analysis approach, which involved familiarizing with the data, developing preliminary codes, and organizing these codes into meaningful themes. From these interviews, four major themes emerged, each with supporting subthemes and participant quotes. Common themes identified in both interviews and surveys included confusion, concern or anxiety, and lack of parental involvement. Unique themes from the interviews were awareness of educational rights, availability of services, and issues within the school system. Parents also offered recommendations for improving educational provisions, aiming to enhance support and services for youth with ASD in Saudi Arabia.

3.2.2 Confusion and feel or experience concern or anxiety

Most parents voiced deep concerns about the adequacy of current educational services for their children with ASD, especially in relation to preparing them for the future. They emphasized the inherent challenges of ASD, which make it difficult to anticipate their children’s prospects for independent living and employment. One parent noted that existing transition services were insufficient, stating, “The current transition services are not enough at all for my daughter because this program does not prepare her for life, and all the educational goals in her plan do not support independence.” Another parent highlighted the repetitive and basic nature of educational goals, explaining, “Every year the school makes me sign off on the same goals that were previously taught to my daughter. These goals include basic skills such as letters and numbers, without considering what the future holds for a student with ASD or the essential skills they need to acquire before graduation. I believe that the school, the teachers, and the educational system do not understand parents’ concerns or needs.” These insights underscore parents’ frustration with the lack of individualized, future-oriented planning in current transition services.

3.2.3 Lack of parent’s involvements

Most participants, both in interviews and surveys, reported that they are excluded from the processes of planning, writing, implementing, and executing their children’s educational plans or transitional services. Many parents expressed dissatisfaction with their inability to select goals that hold social significance for their children. Typically, educational plans are prepared solely by the special education teacher, with little to no opportunity for parental review or feedback. As one parent stated, “Neither the school nor the teachers provide instructions that enhance my ability to implement the goals as a mother, particularly regarding any objectives that might prepare my son with ASD for the future.”

3.2.4 Lack of awareness of education rights

The interviews showed that most mothers lack sufficient knowledge about the educational rights of their children with ASD, with many reporting an absence of clear explanations regarding these rights (interviews). Enrolling their children in school often requires repeated personal effort, and even after enrolment, parents remain uninformed about their children’s right to transitional plans or their own roles in the educational process (interviews). Some families advocate for their children’s education based on emotion rather than legal understanding, emphasizing the need for better parental knowledge (interviews). As one mother noted, there is a strong need for parent counselling sessions to help families understand their rights and participate in educational planning, since schools often exclude parents from important decisions (interviews).

3.2.5 Variability of the services

Interviews conducted across four cities revealed that no program offered a comprehensive transitional plan with specific goals and services for students with ASD. In many areas, especially outside Riyadh, schools lacked inclusive classes for these students, and some did not have qualified teachers to instruct or train them, largely due to the absence of structured inclusion programs and transitional services. There were also no established services to support transitions between educational stages, such as from kindergarten to primary school. Parents described facing significant challenges, including moving their children between multiple kindergartens to find a place and encountering complex procedures for elementary school registration, where acceptance was often based solely on IQ scores rather than a holistic assessment of needs. These findings highlight systemic gaps in transitional planning, teacher preparation, and inclusive infrastructure for students with ASD in Saudi Arabia.

3.2.6 School system

Many parents of students with ASD expressed serious concerns about the school system, noting that challenges stem not only from their children’s disorder but also from a lack of supportive policies to facilitate transitions and integration (parent interviews). Parents highlighted the insufficient development of non-academic skills such as self-determination and self-advocacy, despite their recognized importance (parent interviews).

Negative attitudes from school staff toward students with ASD were also reported, which diminished the effectiveness of transition services. For example, one parent recounted being discouraged from seeking vocational training for her son, as the school principal stated that teachers were not expected to teach everything to a student with ASD, causing the parent significant frustration and distress (parent interviews).

Furthermore, parents described the school environment as inadequately prepared to support students with ASD, with schools often failing to provide the necessary conditions for integration and skill development, both of which are crucial for enabling these students to become active members of society (parent interviews).

3.2.7 Integrated results

This section presents results from both phases of the study, integrated into the discussion section per the sequential explanatory design. The study identified several themes from the data: availability of transition plans, preparation of transition plans, rights of youth, implementation of transition plans, and the success of youth with ASD.

3.2.8 Parental perspective on transitional services for youths with ASD

Most parents disagreed that transitional plans are provided to students with ASD in middle or high school to prepare them for life after graduation, with some expressing uncertainty about the effectiveness of existing plans (parent interviews). Parents voiced significant concerns about the quality of educational services, particularly as their children transition into adulthood, and viewed current programs as inadequate for fostering independent living skills (parent interviews). Key issues include unilateral decision-making and a lack of stakeholder consultation, as teachers, officials, and administrators often work independently, excluding parents from meaningful collaboration (parent interviews).

Although 65% of parents reported participating in the preparation of transition plans, their involvement is limited; most are not allowed to contribute to planning, writing, or implementing these services, as plans are typically developed solely by special education teachers without parental input (parent interviews). This absence of a formal framework often forces parents to create individualized plans on their own, restricting their ability to set goals for their children and reducing their participation to advocacy—an effort further hindered by limited access to information about their rights and roles (parent interviews). Communication from schools is minimal, and advocacy is often based on emotion rather than a solid understanding of legal rights, reducing its effectiveness (parent interviews).

Parents agreed that preparing and implementing transition service plans in middle and high schools is essential for shaping the future of students with ASD, but current plans are mostly short-term and annual, lacking guidance for subsequent years or after graduation (parent interviews). There were widespread concerns about deficiencies in life skills training and the failure of current educational goals to prepare students for independent living and employment, which negatively affects their ability to lead fulfilling lives post-school (parent interviews). As one parent stated, “the current transition services are not enough at all for my daughter because this program does not prepare her for life, and all the educational goals in her plan do not support the independent” (parent interviews).

3.2.9 Parental perspective on barriers to the planning and delivery of transitional services

The majority of parents report that schools lack policies and regulations to provide transitional services for students with ASD in middle and high schools, resulting in the absence of systems to support these students’ transitions and integration (parent interviews). Existing programs primarily focus on academic achievement and neglect the development of non-academic skills like self-advocacy, which many children with ASD therefore lack (parent interviews). Additional barriers include insufficient administrative support and inadequate financial resources, which limit schools’ ability to integrate students with ASD and provide necessary facilities, qualified staff, and resources—problems that are especially acute outside Riyadh, where coordination among the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, schools, and parents is notably poor (parent interviews).

There is also a lack of cooperation among families, schools, communities, and other stakeholders in preparing and implementing transition plans, with each group working independently rather than collaboratively (parent interviews). Parents are excluded from setting goals and from the planning, writing, and implementation of educational plans, as teachers typically develop these plans without stakeholder input or parental feedback, and there are few measures to foster parental engagement (parent interviews). Furthermore, parents—especially mothers—lack the information and awareness needed to advocate effectively for their children’s educational rights, as no government-led awareness campaigns have addressed this issue (parent interviews). Teachers, including those in special education, also lack the skills and knowledge required to develop effective transitional plans (parent interviews). Overall, these findings underscore the urgent need for a systemic approach to address both universal and region-specific barriers, as strong parental interest and advocacy are currently undermined by significant structural and resource-based obstacles (parent interviews).

4 Discussion

This study underscores the crucial role of parental involvement in the successful transition of students with ASD in Saudi Arabia, echoing Hoffman and Kirby (2022), who found that parental engagement is essential for positive transition outcomes. Despite parents’ willingness to participate, structural barriers within Saudi schools limit their actual involvement, a challenge also documented in the U. S. and Australia, where institutional constraints hinder parental participation in educational planning (Pillay et al., 2021).

The research reveals that most parents perceive a lack of effective transition plans for middle and high school students with ASD, especially in preparing them for life after graduation. There is minimal collaboration among government bodies, schools, teachers, and parents, resulting in ineffective implementation of transition programs—a finding consistent with Almalki (2025), who noted that while transitional services for students with intellectual disabilities exist, they are inadequately executed. This lack of coordination leads parents to view these services as virtually non-existent.

Parents also voiced concerns about the quality of educational services, particularly regarding transitions to adolescence and adulthood, citing that current programs do not adequately prepare students with ASD for independent living. Almalki (2025) similarly observed that transition service goals often fail to align with students’ actual needs, compounded by poor communication among stakeholders and limited involvement of decision-makers in planning processes.

Participants stressed the need for effective transition service plans to shape the futures of students with ASD after high school. Supporting this, research from the U. S. (Grünke and Cavendish, 2016) demonstrates that collaboration between parents and educators in developing joint plans facilitates smoother transitions and ongoing support after graduation. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) also mandates parental involvement in creating IEPs. In contrast, transition plans in Saudi Arabia are typically short-term and annual, lacking the long-term solutions necessary to support students with ASD beyond middle or high school.

This study compares systemic barriers to transition planning in Saudi Arabia with those in other countries, revealing key challenges for parents and schools. In the United States, structured policies like IDEA require parental involvement in transition planning, fostering collaboration among families, schools, and community services (Grünke and Cavendish, 2016). In contrast, Saudi Arabia lacks similar policies, resulting in inconsistent transition planning and delivery across schools, and leaving parental participation largely symbolic despite strong interest. Snell-Rood et al. (2020) note that without such policies, schools struggle to create individualized, effective transition plans, highlighting systemic barriers in the Saudi context.

The study also finds regional disparities in the accessibility and quality of transition services in Saudi Arabia, echoing challenges reported in other Middle Eastern contexts. Almalki (2025) observed that services for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities are often limited by geographic and institutional factors, leading to inconsistent resources and program quality. Similarly, Xu et al. (2024) found regional discrepancies in China that hinder students’ integration, emphasizing the need for equitable resource distribution and standardized programs.

A lack of systemic support in Saudi Arabia further limits parents’ ability to advocate for their children, especially regarding non-academic skill development. Gelbar et al. (2014) reported that insufficient information on transitional services impedes effective support systems, and this study similarly found that many parents lacked information about their children’s rights and their own roles in transition planning, restricting meaningful parental contribution.

Another major barrier is the lack of administrative support and inadequate financial resources for students with ASD. Administrative backing from government ministries is crucial for collaboration among parents, teachers, and schools, while financial resources are needed to equip schools with appropriate facilities (Pillay et al., 2021). The study also highlights the absence of specialized roles, such as Transition Specialists, which are common in the U. S. and Australia to coordinate transition efforts and develop life skills for students with ASD (Bruck et al., 2022). In Saudi Arabia, this responsibility falls on teachers, who often lack the necessary training or support, as reflected in parent interviews. These findings underscore the importance of establishing specialized positions like transition coordinators to work with parents and staff in developing effective, individualized transition plans.

In addition to structural challenges, such as limited policies and weak coordination across sectors, this study highlights deep human barriers that impact the transition experience. Many teachers lack sufficient training in transition planning, and some administrators are not fully aware of the long-term needs of students with ASD. At the same time, families—often deeply motivated to support their children—find themselves without the necessary information or opportunities to contribute meaningfully to the process. While these challenges resonate with earlier findings, this study offers a more focused perspective on the specific realities faced by families of students with ASD. By elevating parents’ voices, the study highlights the importance of family insight and involvement in designing transition services that are not only functional but also responsive to students’ broader developmental and life goals. Ultimately, the findings underscore the need for early, inclusive, and culturally sensitive planning that aligns with the lived experiences and aspirations of Saudi families as they strive to support their children’s independence and future success.

While previous research in Saudi Arabia has begun to shed light on the challenges facing students with disabilities during the transition to adulthood, much of this work has focused on postsecondary contexts. For example, in their 2020 study, (Almalky et al., 2020) explored how families perceive school-business partnerships designed to support students after graduation. Although parents valued these partnerships in theory, many expressed frustrations with restricted access, lack of cultural alignment, and poor communication. These findings underscore the need for more coordinated and responsive support systems that take into account the lived realities of families. Building on this foundation, the current study turns attention to a less-explored but equally important aspect of the transition process: the early planning that occurs within middle and high schools for students with ASD. Unlike previous studies that concentrated on the broader disability population or focused on employer and school perspectives, this research brings parental voices—particularly those of mothers—to the forefront. Through in-depth interviews and survey data, this study reveals that many families experience transition services as fragmented and inadequate. While some parents reported limited participation in developing transition plans, most described feeling excluded from meaningful decision-making. Instead of working alongside schools, families often find themselves navigating the transition process alone, with little guidance or institutional support. These insights provide a more personal and grounded understanding of the everyday struggles that parents face when trying to secure a better future for their children with ASD.

While this study offers valuable insights into how parents in Saudi Arabia experience transition services for their children with, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. To begin with, most participants in this study were mothers. This reflects common caregiving patterns, particularly in families of children with disabilities, but it also means that the perspectives of fathers and other family members may not be fully represented. In addition, because many participants were recruited through schools and support networks, they may reflect families who are already more connected or engaged, which could introduce a degree of self-selection bias. Another limitation is the exclusive focus on parents’ voices. While understanding the experiences and views of families is critical, the absence of input from teachers, school leaders, and service providers leaves a gap in capturing the complete picture of how transition services are designed and delivered. Future research would benefit from incorporating these perspectives to gain a deeper understanding of how all stakeholders can work together to support students. It’s also important to note that the findings may not reflect the experiences of all families across the Kingdom. Cultural, geographic, and resource-related differences between regions—especially between urban and rural areas—may influence how services are accessed and how families are involved.

Looking ahead, future studies should aim to include a broader and more diverse group of families, especially from underserved communities. Engaging educators, policymakers, and even students themselves can also deepen our understanding of what effective transition planning looks like in practice. Long-term research could help reveal how early planning and parental involvement shape students’ journeys after they leave school. By continuing to explore these issues, future research can help build more inclusive, informed, and culturally responsive practices—ones that truly reflect the needs and hopes of Saudi families supporting children with ASD.

4.1 Based on the findings, the study concludes the following

• While transitional services are acknowledged by parents, they are largely perceived as insufficient. The services provided lack a comprehensive focus on developing the independence and practical life skills necessary for students with ASD to succeed post-school. This misalignment between the services offered and the real-world needs of students highlights a critical gap.

• Without a structured, life-skills-oriented approach, the primary goal of transition services—preparing students for independent adulthood—is not being met, leaving students unprepared for life beyond the school environment.

• Key systemic barriers that impede the effectiveness of transitional services include the absence of clear policy frameworks, insufficient interagency collaboration, and inadequate resource allocation. These structural challenges contribute to a fragmented service landscape, characterized by inconsistencies in the quality and availability of support. Consequently, these factors negatively affect student outcomes. Addressing these issues requires comprehensive policy reforms, targeted investments in resources, and enhanced interagency cooperation.

• Effective transitional services demand cohesive efforts among relevant agencies, adequate funding, and the establishment of policies that enforce the delivery of comprehensive, evidence-based programs tailored to the specific needs of students with ASD.

• Parental involvement is identified as a critical, yet underutilized, element in effective transition planning. Although parents show a strong willingness to engage, they are often excluded from key decision-making processes and lack sufficient information about their rights and roles in their children’s transition plans. This exclusion reduces the effectiveness of transition services and weakens the broader support network for students with ASD.

• The study stresses that for transitional services to achieve their intended outcomes, parents must be fully integrated into both the planning and execution phases. Establishing clear guidelines and structured opportunities for collaboration is essential. By adopting a collaborative approach that positions parents as central partners in the process, the educational system can significantly enhance the effectiveness and impact of transitional services for students with ASD.

What this paper adds

1. This study is one of the first to examine parental involvement in the transition planning for individual with ASD within Saudi schools using a mixed-methods approach.

2. This study provides culturally grounded insights into the unique challenges Saudi families face during school transitions.

3. The study identifies key barriers, including limited awareness, weak school communication, and poor inter-agency coordination.

4. The findings offer practical guidance for policymakers, educators, and service providers to improve inclusive transition practices.

5. Through qualitative interviews, the study magnifies the voices and lived experiences of Saudi parents, often overlooked in research.

6. This study lays a foundation for targeted programs, awareness movements, and stronger school-family partnerships to improve transition outcomes for students with ASD.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by King Saud University with number KSU-HE-25-480. Participants were assured of both the privacy and confidentiality of the information they provided. The participants receive detailed explanations about the study’s risks and benefits. The participants’ confidentiality was maintained during data collection and analysis, especially for interviews. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

GA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the parents who participate in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akasheh, W. M. , Haider, A. S. , Al-Saideen, B. , and Sahari, Y. (2024). Artificial intelligence-generated Arabic subtitles: insights from Veed. Io’s automatic speech recognition system of Jordanian Arabic. Texto Livre 17:e46952. doi: 10.1590/1983-3652.2024.46952

Al Awaji, N. N. , Al-Taleb, S. M. , Albagawi, T. O. , Alshammari, M. T. , Sharar, F. A. , and Mortada, E. M. (2024). Evaluating parents’ concerns, needs, and levels of satisfaction with the services provided for ASD children in Saudi Arabia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 17, 123–146. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S447151

Alasiri, R. M. , Albarrak, D. A. , Alghaith, D. M. , Alsayari, O. S. , Alqahtani, Y. S. , Bafarat, A. Y., et al. (2024). Quality of life of autistic children and supported programs in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Cureus 16. doi: 10.7759/cureus.51645

Aldosari, M. S. , and Alzhrani, A. J. (2024). Evaluating Saudi parental interagency on collaborative initiatives for successful post-secondary transition of students with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. :17446295241262565. doi: 10.1177/17446295241262565

Alfawzan, S. , and Almulhim, N. (2024). Barriers and facilitators to implementing transition services for students with intellectual disabilities in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a systematic review. J. Intellect. Disabil. 17446295241301853, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/17446295241301853

Almalki, S. (2025). Transition services for high school students with intellectual disability in Saudi Arabia: issues and recommendations. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 68, 880–888. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2021.1911564

Almalki, S. , Alqabbani, A. , and Alnahdi, G. (2021). Challenges to parental involvement in transition planning for children with intellectual disabilities: the perspective of special education teachers in Saudi Arabia. Res. Dev. Disabil. 111:103872. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103872

Almalki, N. S. , Arrushaid, O. M. , Farah Bakhiet, S. , and Alkathiri, S. (2023). Examining the current practices of the individualized family services plan with young children with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 69, 163–178. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2021.1936849

Almalky, H. A. (2018). Investigating components, benefits, and barriers of implementing community-based vocational instruction for students with intellectual disability in Saudi Arabia. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 53, 415–427. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-48.5.313

Almalky, H. A. , Alqahtani, S. S. , and Trainor, A. A. (2020). School-business partnerships that facilitate postsecondary transition: evaluating the perspectives and expectations for families of students with disabilities. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 119:105514. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105514

Almalky, H. A. , and Alrasheed, R. S. (2023). Saudi teachers' perspectives on implementing evidence-based transition practices for students with intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 137:104512. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2023.104512

Almughyiri, S. (2025). Saudi teachers ‘knowledge and implementation of evidence-based practices to improve students with autism’social skills. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 71, 526–533.

Alnahdi, G. H. , Alwadei, A. , and Schwab, S. (2024). Listening to the voices of adolescents with intellectual disabilities: exploring perception of post-school transition. Res. Dev. Disabil. 151:104770. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2024.104770

Alquraini, T. A. , and Rao, S. M. (2020). Developing and sustaining readers with intellectual and multiple disabilities: A systematic review of literature. Intern. J. Develop. Disab. 66, 91–103.

Authority of People with Disability (2024). Statistics. Available online at: https://apd.gov.sa/stat

Ayres, M. , Parr, J. R. , Rodgers, J. , Mason, D. , Avery, L. , and Flynn, D. (2018). A systematic review of quality of life of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism 22, 774–783. doi: 10.1177/1362361317714988

Binmahfooz, S. (2022). Transition services in Saudi Arabia: revisiting the research trends and objectives. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 99, 112–134. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2022.99.007

Braun, V. , and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bruck, S. , Webster, A. A. , and Clark, T. (2022). Transition support for students on the autism spectrum: a multiple stakeholder perspective. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 22, 3–17. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12509

DaWalt, L. S. , Greenberg, J. S. , and Mailick, M. R. (2018). Transitioning together: a multi-family group psychoeducation program for adolescents with ASD and their parents. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 251–263. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3307-x

Findley, J. A. , Ruble, L. A. , and McGrew, J. H. (2022). Individualized education program quality for transition age students with autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 91:101900. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101900

Friedman, N. D. , Warfield, M. E. , and Parish, S. L. (2013). Transition to adulthood for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: current issues and future perspectives. Neuropsychiatry 3, 181–192. doi: 10.2217/npy.13.13

Games, P. A. , and Howell, J. F. (1976). Pairwise multiple comparison procedures with unequal n's and/or variances: a Monte Carlo study. J. Educ. Stat. 1, 113–125. doi: 10.3102/10769986001002113

Gelbar, N. W. , Smith, I. , and Reichow, B. (2014). Systematic review of articles describing experience and supports of individuals with autism enrolled in college and university programs. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 44, 2593–2601. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2135-5

Grünke, M. , and Cavendish, W. M. (2016). Learning disabilities around the globe: making sense of the heterogeneity of the different viewpoints. Learn. Disabil. Contemp. J. 14, 1–8.

Hoffman, J. M. , and Kirby, A. V. (2022). Parent perspectives on supports and barriers for autistic youth transitioning to adulthood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 52, 4044–4055. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05273-5

Khasawneh, M. A. (2024). Assessing predictors of successful transition services for students with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. J. Infrastructure Policy Development 8:5650. doi: 10.24294/jipd.v8i11.5650

Laxman, D. J. , Taylor, J. L. , DaWalt, L. S. , Greenberg, J. S. , and Mailick, M. R. (2019). Loss in services precedes high school exit for teens with autism spectrum disorder: a longitudinal study. Autism Res. 12, 911–921. doi: 10.1002/aur.2113

Levene, H. (1960). “Robust tests for equality of variances” in Contributions to probability and statistics: Essays in honor of Harold Hotelling. ed. I. Olkin . (California, United States of America: Stanford University Press), 278–292.

Lillis, J. L. , and Kutscher, E. L. (2021). Defining themselves: transition coordinators’ conceptions of their roles in schools. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 45, 17–30. doi: 10.1177/21651434211010687

Perryman, T. , Ricks, L. , and Cash-Baskett, L. (2020). Meaningful transitions: enhancing clinician roles in transition planning for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 51, 899–913. doi: 10.1044/2020_LSHSS-19-00048

Pillay, Y. , Brownlow, C. , and March, S. (2021). Transition services for young adults on the autism spectrum in Australia. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 56, 101–111.

Shaw, K. A. (2025). Prevalence and early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 and 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 16 sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 74, 1–22. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7402a1

Snell-Rood, C. , Ruble, L. , Kleinert, H. , McGrew, J. H. , Adams, M. , Rodgers, A., et al. (2020). Stakeholder perspectives on transition planning, implementation, and outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 24, 1164–1176. doi: 10.1177/1362361319894827i

Tabachnick, B. G. , and Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics, vol. 5. United states: Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River. Available online at: https://lccn.loc.gov/2017040173

Taylor, J. L. , Hodapp, R. M. , Burke, M. M. , Waitz-Kudla, S. N. , and Rabideau, C. (2017). Training parents of youth with autism spectrum disorder to advocate for adult disability services: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 846–857. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2994-z

Watkins, D. C. , and Gioia, D. (2015). Mixed methods research. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199747450.001.0001

Xu, T. , Zou, C. , Li, X. , and Dong, P. (2024). Parents’ and teachers’ perceptions of the transportation experiences of youth with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Career Dev. Transit. Except. Individ. 47:21651434241265638. doi: 10.1177/21651434241265638

Keywords: transitional services, parental involvement, special education, Saudi Arabia, mixed-methods research

Citation: Ain G (2025) Parental involvement and barriers in transitional services for students with autism spectrum disorder in Saudi schools: a mixed-methods study. Front. Educ. 10:1647206. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1647206

Edited by:

Wing Chee So, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Hussain A. Almalky, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi ArabiaHira Chaudhry, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), Malaysia

Sunny Kim, University of California, Santa Barbara, United States

Copyright © 2025 Ain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ghaniah Ain, R2FpbkBrc3UuZWR1LnNh

Ghaniah Ain

Ghaniah Ain