- Departamento de Teoría e Historia de la Educación y Pedagogía Social, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain

Introduction: Western schools are characterized by its increasing heterogeneity. However, they often fail to address cultural and religious diversity, specially of minority groups. Muslim migrant students' identities tend to be overlooked, which affects their feelings of belonging and inclusion.

Methods: This study aims to analyze Moroccan Muslim migrant mothers' perceptions of the way their cultural and religious diversity is addressed in schools. A qualitative research with a critical multiculturalism approach is adopted. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to a total of 12 participants, selected with a purposeful sampling.

Results: Some teachers do not address cultural and religious diversity in the classroom, adopting pedagogies of the indifference. Cultural diversity celebrations are unusual and focus on superficial aspects such as customs and food. Accommodations measures are found as a way to address religious diversity. Nevertheless, no religious diversity celebrations were reported. While Muslim religious celebrations were overlooked, there was a privilege for catholic celebrations, that organized the school calendar and activities. Mothers suggested lessons for all the students to learn from their culture and religion to increase understanding.

Discussion: In conclusion, there is a need for more teacher training, better curriculum specifications and inter-cultural and interreligious practices that foster social cohesion and inclusion.

1 Introduction

The recent migratory growth in Western countries has led governments and policies to concentrate their efforts on answering new demands related to multiculturality and diversity, while fostering social cohesion and inclusion (Romijn et al., 2021). In this sense, educational institutions have also had to adjust to the new challenges that stem from diversity, as they are recognized to be optimal spaces for fostering equity, inclusion, and awareness to cultural heterogeneity (Gay, 2018; Pearce and Lewis, 2018; Ramlackhan and Catania, 2022).

Unfortunately, education systems and schools are also embedded within dominant socio-cultural schemas, and thus, they often reproduce structural inequalities and oppression based on racial, ethnical, religious identification, etc. toward non-dominant collectives (Memon and Chown, 2023; Rissanen, 2019). In this sense, Muslim students bear the brunt of discrimination and exclusion both inside and outside schools (Abu Khalaf et al., 2022; Colak et al., 2020; Mourad, 2022). This is caused by the recent rise in anti-Muslim sentiment and Islamophobia in the West, which enhances hate speech, otherness and violence against them (Farooqui and Kaushik, 2020; Shirazi and Jaffe-Walter, 2020).

These racialised discourses and discrimination deeply affect Muslim migrant students' sense of belonging and well-being, which often leads them to disengage from social interactions and their schools (Graham et al., 2022; Jaffe-Walter, 2013; Shirazi, 2018). To fight against this marginalization, schools also become a powerful tool to foster tolerance, social cohesion and understanding, through the enhancement of cultural and religious diversity (Davies, 2023; Pearce and Lewis, 2018; Ramlackhan and Catania, 2022; Vilà Baños et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, several authors state that cultural celebrations with Muslim students in schools tend to be extremely superficial, which can even lead to confusion between religious and cultural identification (Alibhai-Brown et al., 2006; Hillier, 2014; Niemi et al., 2014). Thus, this depiction of Islam as monolithic and static ignores the multi-faceted nature of identity (Revell, 2009). Therefore, there is a need for a re-examination and innovation on pedagogical approaches and the curriculum itself so that they acknowledge how imbalances and privilege act to the detriment of diversity and minorities (Memon and Chown, 2023).

Educational practices and pedagogical debates are usually subjected to discussions around cultural diversity and interculturality (Davies, 2023; Dervin, 2016; Iwai, 2018). However, religious diversity is normally overlooked, since its incorporation may suppose a conundrum regarding the principles of secularity that characterize western societies and schools (Ipgrave, 2010; Memon and Chown, 2023; Parker et al., 2023; Pearce and Lewis, 2018; Rissanen, 2019). There is a risk that schools' secularists views can be paradoxically contentious, since they tend to devalue and ignore religious minorities, which goes against democratic values and religious pluralism (Subasi Singh, 2022). This is especially clear when there is implicit favoritism toward the Christian religion, as justified in curricular activities and celebrations as “neutral” markers of their cultural imaginary (Keddie et al., 2019; Niemi et al., 2014; Subasi Singh, 2022).

This secularity can also be seen in teachers' own discourses, with conflicting perspectives on how to deal with religious diversity, and especially with Islam which they normally decide to keep out of the classroom (Hillier, 2014; Jaffe-Walter, 2013; Keddie et al., 2019; Rissanen, 2019). This pedagogical indifference is not only present when addressing religious heterogeneity, but also cultural diversity, as for some teachers, emphasizing differences can be a discriminatory action (Gay, 2013; Jaffe-Walter, 2013). Nevertheless, by neglecting other forms of cultural, ethnic and religious expression, teachers implicitly reproduce systemic violence against minority groups, justified under false discourses of equality (Rissanen, 2019; Shirazi, 2018). Thus, they ignore the richness that this pluralism brings into the classroom (Vilà Baños et al., 2019).

In the face of this reality, this research aims to analyse how Moroccan Muslim students' cultural and religious diversity is addressed in Spanish schools. This will be further explained and justified in the next section, after a contextualization of the situation in Spain. It is worth clarifying that this study has focused on the concepts of cultural and religious diversity, as the heterogeneity that currently characterizes western classrooms (Franken, 2017; Ramlackhan and Catania, 2022; Romijn et al., 2021). The terms interculturality and inter-religiosity have been put aside for the purposes of this article, since they refer to a wider meaning than just cultural/religious pluralism. They imply the coexistence and interaction of different cultures, achieving social cohesion, tolerance and understanding between them (Davies, 2023; Dervin, 2016; Vilà Baños et al., 2019). However, the scope in this study is to analyse the way this heterogeneity is managed in the classroom, outside a framework of a pedagogical model.

2 Contextualization

The Moroccan community is one of the biggest migratory groups in Spain as well as the largest Muslim collective, according to the latest demographic data (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2022a; Unión de Comunidades Islámicas de España, 2024). However, several studies state that Moroccan culture and Muslim religiosity are still negatively depicted and stigmatized in Spain, which, in turn, makes them extremely vulnerable to the growing discrimination and Islamophobia (Bayrakly and Hafez, 2023; Boland, 2020; Collet-Sabé, 2020; Olmos-Alcaraz, 2020; Rodríguez-Reche and Cerchiaro, 2023). For this reason, this study focuses on this collective when addressing cultural and religious plurality in Spanish schools. It is worth highlighting that Spanish educational policies have implemented a Programme of Arabic Language and Moroccan Culture in several schools for those who are interested in enrolling in those classrooms (Ministry of Foreign Affairs Cooperation, 2013). Moreover, schools provide Islamic religious education for those who apply for it (Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts, 1992). However, as can be seen, these proposals always focus on separating Moroccan Muslim students from the rest of their peers, who are left out of these matters. Therefore, there is not a celebration of this cultural and religious diversity, but rather a detachment from it.

In this line, Spanish educational policies and curriculum are extremely ambiguous when dealing with cultural diversity and interculturality, making it hard to address. Furthermore, the only mention of religious diversity refers to the need to teach respect toward it, with no further instructions on how to celebrate it (Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts, 2020; Ministry of Education and Professional Training, 2022). This is explained in Spain's adhesion to the principles of secularity, which has proven to be problematic at times, since it is often hard to define the limits of what laicism entails in public spaces and schools (Llorent-Bedmar et al., 2023).

For this reason, several questions arise regarding cultural and religious plurality in Spanish public schools. As critical researchers (May and Sleeter, 2010; Qadir and Islam, 2023), we focused our interest on the perceptions of Moroccan Muslim migrant mothers who live in the area of Seville (Andalusia), since their contributions can be insightful and are often overlooked. Therefore, we wondered how Moroccan Muslim students' cultural and religious diversity is addressed in schools. To answer this, more specific questions where posed: What are the teachers' attitudes toward cultural and religious diversity? How do schools address cultural and religious diversity? What are the mothers proposals for improvements to foster cultural and religious diversity in schools?

It is hoped that, with a critical approach to these questions, it will be possible to raise awareness about this reality. Therefore, offering guidance for the development of policies and curriculum specifications that accurately respond to this diversity. Furthermore, this can foster the development of pedagogies that align with current educational trends, that focus on the need of deeper discussions of what culture entails, stressing aspects closely related to cultural construction such as colonialism, discrimination, racism, etc. (Davies, 2023; Hillier, 2014; Memon and Chown, 2023; Niemi et al., 2014; Wood and Homolja, 2021). The aim is to enhance Moroccan Muslim migrant students' positive sense of identity, belonging and inclusion, while tackling prejudice and stereotyping (Pearce and Lewis, 2018).

3 Materials and methods

The data presented in this paper was generated from a larger study that sought to examine Moroccan Muslim migrant mother's perceptions of their children's inclusion during their formal education. The main objective of this research is to analyse Moroccan Muslim migrant mothers' perceptions of the way their cultural and religious diversity is addressed in schools. In order to do this, the following specific aims are stated (A) Analyze the mothers' perceptions on teachers' attitudes toward cultural and religious diversity; (B) Identify the way schools address cultural and religious diversity from the mother's perspective; and (C) Detect mothers' proposals for improvement to foster cultural and religious diversity in schools.

To give answer to the objectives of the study, a qualitative research with a critical multiculturalism approach is conducted, since it aims to analyse power imbalances in education that stem from race, ethnic, cultural, religious and language identification (May and Sleeter, 2010; Qadir and Islam, 2023). Furthermore, this research makes it possible to point out structural injustice and disadvantage for non-dominant groups as compared to the dominant ones in education systems (Gorski and Parekh, 2020; Narain, 2012). In this sense, it advocates for awareness about White hegemony, that shapes educational practices and enhances specific cultural/ethnical privilege in the classroom (Quijada-Cerecer and Alvarez-Gutiérrez, 2010). Thus, this approach allows for a critical study of privilege and systemic inequity for cultural and religious celebrations within Spanish schools regarding minority groups, specifically Moroccan Muslim migrant students.

Furthermore, as this study ascribes to the principles of critical multiculturalism, it also fosters recognizing cultural diversity and the need to promote and support those marginalized identities in educational institutions (Gorski and Parekh, 2020). This approach fosters the co-existence and understanding of different cultures, religions, ethnicities, etc. that should be celebrated and acknowledged in educational contexts (Gorski and Parekh, 2020; Qadir and Islam, 2023). Moreover, it seeks for criticality about our own positionality as researchers and educators, not only in reproducing and contributing to this inequality, but also in promoting social justice (May and Sleeter, 2010; Quijada-Cerecer and Alvarez-Gutiérrez, 2010).

Following the principles of critical multiculturalism, the study tried to raise awareness of the voices and experiences (often silenced), of those who struggle with social exclusion and inequality, since they are essential to understanding these phenomena (May and Sleeter, 2010). In fact, it advocates for challenging dominant and hegemonic narratives, by obtaining wider perspectives through other agents involved in the school life (Qadir and Islam, 2023; Quijada-Cerecer and Alvarez-Gutiérrez, 2010). Therefore, this study tried to give voice to Moroccan Muslim migrant mothers.

Data was gathered through semi-structured interviews that permitted the researcher to benefit from a certain amount of openness, focusing on specific information that arose from the sessions and that could enhance understanding about the area of concern (Adams, 2015). In these exchanges, an interview team was created which was aware of its positionality (Darwin Holmes, 2020; May and Sleeter, 2010; Quijada-Cerecer and Alvarez-Gutiérrez, 2010). The research team was made up of a translator, who is a young member of the Moroccan community, and a young female researcher. Thus ethnicity, religiosity, gender, age, and migration status were taken into consideration, achieving and insider/in-betweener positionality (Darwin Holmes, 2020). This was done with the aim of creating safe spaces to share and have conversations that can sometimes be uneasy.

Mothers reported very positive feedback from these interviews, as they claimed they felt heard, understood and were appreciative of having a space to express their opinions. Furthermore, having a Muslim Moroccan translator eased the first approach to the mothers as well as the whole interview process. The majority of mothers were willing to speak in Spanish during the interviews (let alone those whose Spanish knowledge was too low) and the translator was just a supportive asset they turned to when they could not find the right words. Although his function as a translator was more limited, his intervention and familiarity with the socio-cultural norms helped the team to respectfully navigate these interactions.

3.1 Sampling

Moroccan mothers are chosen as the study population as they constitute the biggest Muslim migrant collective in Spain (Unión de Comunidades Islámicas de España, 2024). According to the latest demographic data, Moroccans constitute the 13% of the total foreign population in the province of Seville, with nearly half of them living in the city of Seville, specifically (Encuesta de Población Activa, 2022; Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2022b). As stated above, this study aimed to give voice to those minoritised groups, following the tenets of critical multiculturalism, hence Moroccan mothers were interviewed. The vulnerability of Moroccans in Spain is stated in several studies, as they struggle with the increasing discrimination and Islamophobia, as well as Moroccan culture and ethnicity being negatively depicted (Bayrakly and Hafez, 2023; Boland, 2020; Collet-Sabé, 2020; Rodríguez-Reche and Cerchiaro, 2023).

Moreover, several studies state the danger of the social desirability bias in teachers' responses, who often try to respond in ways that are socially acceptable, rather than their real expectations or beliefs (Ayala et al., 2024; Tempel, 2022). This is also seen when approached about inclusive education, as they try to refer themselves as overly inclusive and supportive, responding to demanding performative expectations (Tempel, 2022). The existence of this bias, as well as numerous studies that focus on teachers' perceptions about cultural and religious diversity in the classroom (Davies, 2023; Pearce and Lewis, 2018; Rissanen, 2019; Subasi Singh, 2022; Vilà Baños et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022), led us to wonder what the mothers views could be in this sense, bringing a new approach to these issues. Specially since Rissanen (2019) noticed that Muslim parents' opinions about cultural and religious identification tended to be ruled out of the school life in Finish and Swedish schools, and their educational expectations and decisions were often questioned, due to essentialist pre-conceptions about Muslims.

After contacting several local and regional migration and jurisdictional entities, we were informed that there is no statistical data regarding schools with high percentage of Moroccan students. They explained that, as to comply to safeguarding reasons, the nationality of origin or religiosity of students was not collected or distributed. Hence, as this information was not available, we decided that the sampling would follow a different trajectory. Thus, we approached those neighborhoods and/or areas characterized by having a more diverse migrant background in the city of Seville (i.e. Cerro del Águila, Carretera Amarilla, etc.).

In these specific areas, we contacted several organizations that worked with Moroccan families, and Mosques, thus mothers were recruited through those channels. This study used purposeful sampling, as it allows for rich and detailed information about a specific phenomenon (Creswell, 2012). Therefore, Moroccan Muslim mothers were invited to participate in the study. They were recruited according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) Moroccan Muslim migrant mothers; (2) with children enrolled in formal education in public institutions; (3) living in the metropolitan area of Seville; (4) participating voluntarily in the study.

One of the limitations of the study, was the reluctancy of many mothers to participate, which is common in critical studies. In this sense, critical studies recognize the richness of the interpretative information, and enhances those narratives regardless of the inaccessibility that often leads to small samples (May and Sleeter, 2010). These obstacles were soothed by always reaching the mothers through someone they already knew (i.e. social workers, imams, other mothers, etc.). Moreover, we also developed a snowballing sample, asking the interviewed mothers to refer us to more mothers they thought they could be in the same situation.

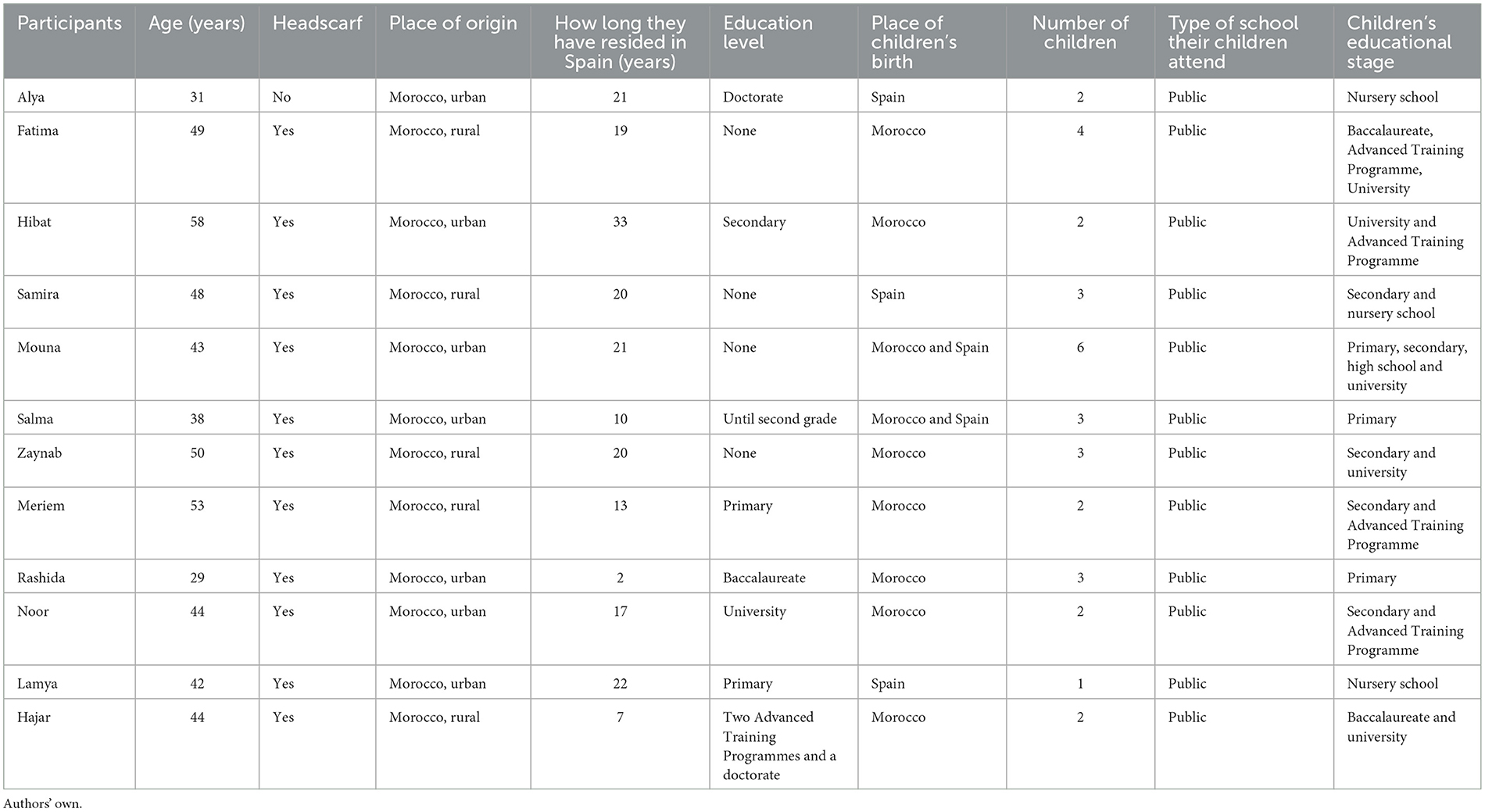

In this sense, all the mothers interviewed had children enrolled in schools with a high migrant population, as they were set in these migrant majority neighbors/areas. Moreover, mothers were consulted on this issue. They were asked if there were other migrant, Moroccan and Muslim students in their children's school. All of them confirmed there was a high percentage of migrant students in their children's school. In particular, seven of them also had their children enrolled in Muslim majority schools, which often implied the presence of more Moroccan students too. As this study focuses on cultural diversity, we decided to introduce the interviews with all the mothers and not just these seven, as they could provide insightful information about this reality. We have not provided the information about the specific schools, as a way to protect these families and the students, as many of them are still enrolled in them. In the end, a total of 12 participants were obtained. The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample can be seen in Table 1.

3.2 Data analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The data analysis was carried out with the program Aquad 7 (v. 7.6.1.1.). Following a qualitative thematic content analysis with an inductive and deductive lens, in which codes are both data and concept driven (Schreier, 2012). Firstly, a deductive content analysis was carried out. A category system, with its subsequent subcategories, was deduced from the previous analysis of the literature (Torres-Zaragoza and Llorent-Bedmar, 2024). Secondly, a thorough analysis of the transcript and data allowed the creation of new themes and sub-themes. The originally driven main units were revisited after this inductive content analysis, developing and refining the final dimension, categories and codes. These final dimension and codes were discussed as a team, in order to reach mutual agreement. This allowed the interpretation of the data and the ensuing collection of the results.

3.3 Ethical considerations

Participation in the study was voluntary and all potential participants signed an informed consent that ensured confidentiality and anonymity, and included the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any time. Pseudonyms were used and names of places mentioned by participants were altered to protect their identities. Ethical clearance was granted by anonymised.

4 Results and discussion

The results are displayed from a micro to a macro level. Firstly, results are set at a classroom level, focusing on the teachers' attitudes. Secondly, they widen the scope by studying cultural and religious diversity celebrations in the schools. Finally, mothers' proposals for improvement are taken into consideration.

4.1 Pedagogical practice: recognizing cultural and religious diversity at a classroom level

Pedagogical practice and teachers attitudes toward heterogeneity have a significant impact on fostering cultural and religious diversity in the classroom (Gay, 2018; Koukounaras-Liagkis, 2015; Romijn et al., 2021). However, there are still situations in which this diversity is completely overlooked, as it is the case of Mouna.

My children's cultural identity, as far as I'm concerned, hasn't caused any kind of problem. There has been neither prejudice against it, nor any kind of interest in it. In other words, they're very indifferent to it, because it hasn't given them any problems or difficulties, but it hasn't given them any kind of benefit either. As the teachers don't do anything to highlight it, it didn't stand out in a negative way either, so it was very neutral on their part. They see their culture with complete indifference. (Mouna)

Many teachers perpetuate, under discourses of equality, this pedagogy of indifference and color-blindness, by considering that focusing on the differences is actually a racist and contentious action itself (Gay, 2013). However, these resistant attitudes toward diversity are just another way of perpetuating the hegemony of the dominant culture, in which cultural, ethnic and religious minority groups are completely overlooked and marginalized (Rissanen, 2019). Alya is an example of this. She claims that teachers do not have any interest in their culture or religion since they also do not pressure them with those things.

I feel that, since we don't emphasize our culture or religion, the teachers don't even feel the need to do it either, it doesn't even cross their. (Alya)

It can be seen that attitudes toward diversity differ from one teacher to another, making it impossible to generalize about them being responsive or not to cultural and religious heterogeneity. While some teachers showed disengagement and reluctancy to highlight it, others were interested, as Salma, Meriem and Rashida's excerpts demonstrate. This is shown in Wang et al. (2022) which state that teachers have a behavioral disposition to work on diversity stemming from their personal opinion of it and their professional experience, thus being more responsive when having greater experiences with multiculturality.

The teacher asks a lot of things, praying…, they ask a lot of Islamic stuff. (Salma)

My daughter has a teacher who always asks her about Morocco or Islam. They talk about it. But my son is never asked about anything like that. (Meriem)

More or less, sometimes no. There are teachers that ask and who don't have a problem, but other teachers, some teachers, are not interested. (Rashida)

While teachers' attitudes cannot be generalized, it can be seen that there is still a lack of celebration of this diversity, which is a source of concern. At a classroom level, diversity should be celebrated daily, since it can have a positive impact on students' engagement and sense of belonging (Graham et al., 2022). However, from Mouna's excerpt, it can be seen that cultural diversity in the classroom scarcely happens and, when it does, there is no pedagogical interest.

Yes, it obviously depends a lot on the teacher. It normally didn't happen, but from time to time it was like ‘well let's do this activity' and they would tell my children: ‘well, since you have that perspective and if you want to show it then go ahead'. And that's it. I do have examples of this, but it happened rarely, very rarely. It's not like they don't allow them to do it, but they haven't invited them to do it much either. And that would only happen once or twice a year… (Mouna)

Agreeing with numerous authors, there is a need for constant discussion around diversity in the classroom, not only about superficial aspects of culture and religion, such as celebrations, but also about marginalization, which enhances understanding and social justice (Davies, 2023; Hillier, 2014; Memon and Chown, 2023; Wood and Homolja, 2021). The results shed light on the importance of teacher training, since it can be seen that celebrating diversity relies on their ability and willingness to celebrate it. In this line, current trends focus on training in culturally responsive teaching as a way to enhance teachers' awareness and provide them with useful skills and tools to foster interculturally in their teaching (Iwai, 2018; Gay, 2018; Romijn et al., 2021), which is key in decreasing pedagogies of indifference.

4.2 Cultural diversity in schools

Shifting to a wider perspective than just the classroom, it can be observed that when it comes to celebrating cultural diversity in the school, the schools undertake activities that are focused on the preparation of traditional food and/or showing some typical customs/traditions from each country without going into greater depth. This can be seen in Fatima, Rashida and Noor's interviews.

Yes, when my kids were in high school, there was a workshop that was... well, it lasted for a week and they called it the ‘cultural week' and so everyone could bring, for example, typical dishes from their country. For example, my son and his friend, they made a typical Moroccan pastry and they took it there. And they won the gastronomy contest, in fact, their food was gone in two minutes! [...] Actually, the times they have organized things like that, about cultures in general and so on, they have always invited us, not only us, but Chinese, Arabs, anyone who was there, at the school. (Fatima)

Ten days ago, there was a festival of different countries' cultures, the ‘Festival of Cultures'. But I think it's the first time they celebrated it. There were the parents and the children. The parents were the ones presenting and the children were walking around to see the booths with the different food and explanations about the culture. We made Moroccan food. We made sweet and savory food too. We participated because I would like my children to be better off at school. (Rashida)

They asked us to bring typical Moroccan things, you know? And I made a plate of Moroccan pastries, brought the Moroccan teapot… and they liked that a lot. Plus, the small teacups had Arabic letters on them. But that's the only thing I remember that we did and shared there. (Noor)

It is noted that these activities are quite unusual, since they tend to take place once a year at most. Although they are occasional, they have a positive impact on these pupils and their families, who report these experiences with satisfaction and show great pleasure and pride in sharing their culture with other families, students and even their own children. This aligns with other studies in cultural diversity celebrations in western schools that tend to occur on specific theme days and focus on superficial aspects of the culture, such as traditions and food. Unfortunately, they ignore the intricate nature of identity and provides a rather stereotyped and trivial representation of different cultural groups (Alibhai-Brown et al., 2006; Hillier, 2014; Niemi et al., 2014).

Therefore, this raises some questions about the effective implementation of interculturality in these types of activities, which seem to ignore how cultures and identities should be collectively constructed and reimagined, by learning ‘within' instead of learning ‘from others' (Davies, 2023; Dervin, 2016). In fact, as Hillier (2014) states, these kinds of celebrations that focus on food and festivals can lead to confusion on beliefs, cultures and religious identification among teachers and students (Hillier, 2014). This is not a claim intended to eliminate these activities, which seem to have a positive impact on these students and families, but rather encourage a certain amount of re-examination, since they should aim to challenge discourses around identity and belonging, deepening the understanding through counter-narratives and debates around discrimination (Memon and Chown, 2023; Wood and Homolja, 2021).

Unfortunately, it is also noted that these initiatives usually arise as individual proposals from the schools. As a consequence, many of the mothers interviewed do not even have the opportunity to participate and benefit from these activities, as is the case of Samira, who jokes about how school is for other things.

No, here they have the school to study and that's it. (Samira)

This lack of celebration of diversity can also be explained by the national and regional curriculum's ambivalence, which can deter teachers from fully engaging with this issue. Cultural diversity and interculturality are described as skills to be worked on in specific subjects such as history, arts, human rights and values, etc. Nevertheless, there are no specific guidelines on how to do this, simply a rather vague and ambiguous description of what diversity entails (Organic Law 3/2020, 2020; Royal Decree 157/2022, 2022). Therefore, in order to enhance diversity, the curriculum should be revisited, offering better guidance for teachers and schools. These activities are needed, as stated above, since schools are safe spaces to celebrate and discuss issues related to identity, cultural diversity, while tackling exclusion and prejudice (Pearce and Lewis, 2018).

4.3 Religious diversity in schools

Current diversity and multiculturalism trends establish religion as one of the central aspects of the multifaceted individual's identity and heterogeneity, however, educational systems and frameworks pay little attention to it, since its incorporation into secular societies may raise difficult questions related to religious liberties and neutrality (Ipgrave, 2010; Parker et al., 2023; Rissanen, 2019). This aligns with Fatima, who expresses that the school is inclusive in terms of cultural diversity, but religious diversity often remains invisible.

Yes, I think so. Maybe it was not inclusive in terms of specific Muslim festivals. But it was inclusive in the sense that they tried to make other cultures visible. (Fatima)

Results also show that, while cultural diversity activities tend to occur, activities specifically related to religious diversity and/or Islam did not happen, as Hajar states. This can be explained in the way the curriculum is shaped, since religious diversity is only mentioned as something to show tolerance to in order to avoid discrimination (Organic Law 3/2020, 2020; Royal Decree 157/2022, 2022). Therefore, the curriculum overlooks religious diversity as a pedagogical tool.

No, never. Things about Islam or Arabs never happen at school. (Hajar)

In this line, Meriem even minimizes the issue of not valuing their religion in the classroom, expecting nothing from the schools. This echoes Samira's previous excerpt, in which she claimed the same idea regarding cultural diversity. These feelings of inadequacy exemplify the lack of legitimization of spaces and resources that Muslim students and families tend to manifest, normally caused by discriminatory practices against them, which refrain them from demanding minimum educational needs (Edgeworth, 2014; Jaffe-Walter, 2013; Bergen et al., 2021).

No, they never called me, but I understand that there are many things to do, just to work about this too. (Meriem)

Moreover, Meriem justifies this lack of attention to their religious needs due to the heavy teaching workload. This aligns with several studies that identify that teachers' inability to respond to diversity stems from the demanding academic requirements from the educational authorities (Davies, 2023; Pearce and Lewis, 2018). However, our critical multiculturalism approach calls us to question and not accept discriminatory attitudes toward minority religions and, specifically Muslims, to be tolerated in a system, thus allowing violence and exclusion (Mourad, 2022; Bergen et al., 2021). This completely overlooks the benefits that religious diversity can bring into the classroom, which it would be interesting to teach in a non-confessional scope. This would make it possible to eradicate prejudices or stereotypes (Franken, 2017; Ghosh, 2018; Pearce and Lewis, 2018).

4.3.1 Religious accommodation and Islamic festivities

Accommodation measures are another way to recognize and address religious diversity. In this sense, respondents state that the school is usually flexible when it comes to Islamic festivities. Mouna and Fatima evidence this with examples like the compliance in physical education classes during Ramadan and permission to miss school on Eid. While they are necessary, they should not be the only actions regarding religious diversity, since these procedures just underline monolithic and superficial notions of what Islam entails (Keddie et al., 2019; Memon and Chown, 2023).

Regarding those aspects, the truth is that they were quite flexible. It wasn't like: ‘well, you're in Ramadan, we're in physical education, so you don't have to do physical education', but they did take it a bit more calmly. And then with Eid, which is a day when you are allowed to miss classes and so on, they have normally been more flexible, like, ‘look, today we're not going take into account your children's absence' and so on. Because, in the end, it's a bit more justified. [They] don't give you an absence and so on, because in the end it's a bit more justified. (Mouna)

For example, on Eid, my children were absent and obviously it counted as an absence, but not really. (Fatima)

Although schools are flexible with these festivities, they are not involved in their celebration. Contrary to what may happen when there is a Christian festivity, which will be discussed in depth in the next section. In this sense, Alya says that everything related to her religion is kept at home, as the school is not involved in it. This aligns with several studies in which Islamic religious practice is considered a private matter to be discussed in secular schools, justifying that the exclusion of religion fosters inclusion, which proves to be a inconsistent argument (Gay, 2013; Rissanen, 2019; Jaffe-Walter, 2013; Keddie et al., 2019; Subasi Singh, 2022).

Nothing, nothing at all. Nothing at all because they don't even ask me anything at all. They experience everything related to Muslim religion at home, with their grandparents. But the school doesn't take part in any of these, which they should. (Alya)

Agreeing with Alya, this separation between Islam and the classroom should not happen. Religion is also a part of Muslim students identity representation. However, it is normally seen from a negative perspective, denying these students recognition (Rissanen, 2018). Thus, there is reason to be critical about it, since they are trying to navigate in spaces that are unwelcoming of and obnoxious about their religious identities. This is detrimental to their feelings of belonging and inclusion (Mourad, 2022; Shirazi, 2018).

4.3.2 School calendar: celebrations and festivities

As seen before, while schools ignore Muslim religious celebrations, the school calendar is organized around Catholic celebrations. This is clearly evidenced by undertaking activities such as Christmas caroling, seeing nativity scenes during Christmas, and the processions during Holy Week1, among others. This is another example of how Christian privilege is implicitly embedded in western education systems, with Christian celebrations organizing the school calendar. They are justified for their cultural symbolism and ‘secular' nature, whilst rejecting any other kind of non-Christian celebrations and days of worship (Keddie et al., 2019; Niemi et al., 2014; Subasi Singh, 2022).

These mothers usually advocate for their children's participation and coexistence with other cultures and religions, by letting them participate in these Christian festivities. This dismantles othering assumptions that are often made about Muslim parents and students, as narrow and detached from school activities and the community (Jaffe-Walter, 2013; Subasi Singh, 2022). This othering is extremely dangerous since it justifies Islamophobic and discriminatory practices against Muslims, on the basis of their inability to coexist (Haynes, 2019). However, this idea is proven wrong in most of the participants' excerpts, since they emphasize that their children participate like everyone else, making their desire to enhance their children's inclusion evident.

My children participated just like the others, and we don't see it as something like, I don't know, like them being taught religion or anything like that. That's why we don't mind them taking part […] During Holy Week they didn't have to take a procession or do anything, but they would go see a procession outside of the school. They would also, the typical thing, they set up the nativity scene in the school and they went to see the nativity scene, but that's all. (Fatima)

They have brought drawings home, for example, Christmas trees… […] For example, in their first school, they always had a Christmas party, they bring food for a breakfast. I always cook things at home for them to bring, I don't have any problem. (Samira)

Well, to be honest, we have always told them to participate in these things. We don't celebrate Christmas at home, but we have always told them to do and participate in all the activities that are done at school, so they have celebrated all of them. (Mouna)

That's OK, we live here and you have to know the culture here and there (Morocco). We are Muslims, but we have to see Christian celebrations. You have to see things, that's how you learn. (Hibat)

The school called me to talk about Catholic religion. They called me because they were going to take out a procession during Holy Week and they had to ask for my permission so that my daughter could see it. And I said no problem. If I forbid her not to see it while she's young, when she grows up, she'll see it. It's ok if she sees it. The teacher told me that she is not going to be in a religion class or anything like that, she's just going to sit with her friends and classmates, so there is no problem. They also asked for my permission to see the nativity scene and I said yes, that's fine too. I don't have a problem with her going to see the nativity scene. (Lamya)

Furthermore, these mothers encourage this participation by explaining and discussing diversity with their children, aiming for them to have the enough knowledge to discern and voluntarily participate. This is worth highlighting, since cultural and religious diversity should also be encouraged in schools through deeper discussions around discrimination, violence, and further elements that impact the process of identity construction and which are needed to demystify stereotypes and prejudice (Davies, 2023; Hillier, 2014; Memon and Chown, 2023; Niemi et al., 2014; Pearce and Lewis, 2018; Wood and Homolja, 2021).

I explain to my children what popular festivities, such as Christmas and Easter, consist of, so they are free to participate or not. But I respect all the celebrations that the school organizes and I always try to explain to my children what the celebration is about and if they want to participate, they are free to do so or not. (Rashida)

However, while these mothers are fostering this diversity and inclusion, findings show that they navigate a system that completely overlooks their religion, and that is only superficially interested in their culture. Hence, that leaves us to wonder how schools and education systems are failing to guarantee and embrace cultural and religious recognition.

While all of these mothers are in favor of their children's participation, they sometimes prefer that they not be actively involved in more specific Catholic festivities or in celebrations of a pagan nature. Thus, Salma does not want them to engage in the act of taking out Holy Week's processions, whereas Lamya does not want her daughter to wear a costume on Halloween. This concern varies from family to family, as can be seen.

Well, yes, I don't want them to participate in the processions in Holy Week, other than that, it's fine. (Salma)

Of course, so far, they respect me and that's the way it is. And for Halloween for example, I don't like Halloween. For Halloween my daughter went to school normally, because I don't like Halloween. It's a party that I don't like, but for Carnival I did dress her up as a pirate, because it's a Carnival, I love it. But for Halloween, I don't... it's something I don't like. (Lamya)

This concern highlights a bigger imbalance, since schools, although modeled around “secularized” discourses, favor Christian celebrations, that can trigger some conflicts for student of minority religions (Keddie et al., 2019; Niemi et al., 2014; Subasi Singh, 2022). Therefore, it is then necessary to revisit how these celebrations are organized and whether these activities could be celebrated in a more neutral/non-confessional way, that would foster all the students' inclusion (Franken, 2017; Ghosh, 2018).

4.4 Proposals for improvement

Results show that none of the mothers had been asked/consulted when designing or organizing cultural or religious activities. Even though they can give a broader perspective or enrich such projects, they are often overlooked, silenced or forgotten. Zaynab is just an example of these mothers' lack of engagement in the design of these actions. However, it is necessary for these proposals to be developed by listening to the subjects who are directly concerned, since it can help in building meaningful identities while fostering cohesion within the whole community (May and Sleeter, 2010; Quijada-Cerecer and Alvarez-Gutiérrez, 2010; Rissanen, 2018).

They only call me when, for example, my son gets a bad mark or something like that. Just about something small that can happen in class and that's it, but not for religion or anything. (Zaynab)

The reason why mothers were interviewed is that they can offer a different perspective regarding this reality and can actually help develop proposals for improvement adapted to their needs. We believe that their proposals and opinions should be listened to, since they can be extremely enriching. In this sense, it is worth highlighting Noor's recommendation. She notices that one of the biggest problems is the lack of knowledge about Moroccan culture and Islam, and how Spanish people often confuse the two. For this reason, she proposes lessons that allow non-Arabic and/or non-Muslim students to gain some general insights about their culture and religion.

I would highlight one thing that I think is more important than what the others have said. Because at the end of the day, we learn from our father, our mother, from our family. But people who are Spanish, so to speak, do not know what our culture is. They often confuse religion with culture. I highly recommend, even if it is only once a year, just a talk, explaining the principles of our religion and the differences with our culture, so that they have an overall picture. I have been asked if I take off my headscarf or leave it on at home, and these questions are a bit absurd. I don't know, I know they don't know, but... they should know just a little, the bare minimum. Or another question I've been asked and that made me laugh, even one of my friends laughed, that is: ‘if I wore the scarf, could I show more cleavage?' I told her that obviously not, that if I cover my head, I'm not going to show more cleavage. (Noor)

Noor laughs about the redundant questions she is sometimes asked. However, this is concerning, because her experience highlights the lack of knowledge about Muslims in Spanish society. Unfortunately, ignorance can be one of the main causes for discrimination and Islamophobia in western societies (Abu Khalaf et al., 2022; Colak et al., 2020; Farooqui and Kaushik, 2020; Mourad, 2022; Shirazi and Jaffe-Walter, 2020). Therefore, the need to listen to her proposal, which aligns with an overarching idea that stems from the findings and discussion of this study. That is, schools should foster deeper dialogues on cultural and religious diversity on a daily basis with all the students, and not just minority students, since this can help fostering understanding, tolerance and growth (Davies, 2023; Memon and Chown, 2023; Pearce and Lewis, 2018; Wood and Homolja, 2021; Franken, 2017; Ghosh, 2018; Koukounaras-Liagkis, 2015).

5 Conclusions

In light of these results, it can be seen that Moroccan Muslim migrant students' cultural and religious diversity is still not fully addressed in their classrooms and schools. This research's critical multiculturalist approach allowed us to identify and question this discrimination and the imbalances facing minority cultures and religions in Spanish schools, which positioned us to ask for/claim several changes and points for action to guarantee better inclusion practices.

It can be seen that teachers are key in fostering this heterogeneity. Nevertheless, pedagogies of “indifference” are still present in the classroom, which avoid recognizing and celebrating this pluralism. Therefore, there is a need for more teacher training in culturally responsive teaching, fostering better reflective practices that embrace this diversity in order to promote the creation of positive identities for Moroccan Muslim students and enhance understanding and tolerance among all the students.

Cultural diversity should be addressed on a daily basis in the classroom and in school life in general. However, it is clear that this rarely happens. In this sense, we believe that there is a need for better curriculum specifications, since this ambiguity can also be a factor for disengagement on the part of the educators. As a result, it can be difficult to work on, however, we hope that this research can guide teachers and school leaders to address diversity more regularly. In this same vein, cultural diversity activities need some re-examination, since the very nature of these activities remains superficial, focusing solely on traditions and foods. Therefore, wider discussions about identity construction, discrimination and hegemony are also needed in these celebrations. This should also be aimed toward the whole school community, which can raise awareness and sensitize students, schools staff, parents, etc.

Furthermore, secularism principles should be critically analyzed, since they give privilege to Catholicism, whilst undermining Islam. There is a need for teachers and school leaders to be aware of this privilege, which would guide them to more equitable practices regarding minority religious groups. Instead of focusing on eradicating religion from the classroom, it would be interesting to teach it and embrace it from a non-confessional point of view, since that would help all the students learn about religious pluralism and develop positive/tolerant attitudes toward it.

In agreement with the mothers' proposals for improvement, different cultures and religions should be taught to every student. We advocate getting rid of positions of dominance and hegemony that subtlety benefit the dominant Spanish culture and religion. Hence, seeking more intercultural and interreligious practices, in which there is a real coexistence between different groups. These measures not only apply to Moroccan Muslim migrant students but to all minority students that conform the classroom.

In conclusion, it is hoped that these suggestions serve as guidance for future curriculum choices and pedagogical practices that are culturally responsive. Western societies are characterized by their growing diversity, therefore there is a need to educate future citizens to be sensitive to this pluralism. In this sense, schools are ideal spaces for fostering this social cohesion, equity and inclusion, as well as for developing positive plural identities and promoting minority students' sense of belonging and recognition.

6 Limitations and future research

As with the majority of studies, the design of the current study is subject to limitations, since its qualitative nature hinder the generalizability of the data. Despite limitations, results are of great relevance when highlighting power inequalities between majority and minority groups, thus its relevance to the field of study. Mothers provided insightful information on this topic as well as a broader perspective about situations that their children may not be able to recognize or identify, especially in earlier stages of education. However, future research could also focus on students and teachers perceptions on this topic, although social desirability bias, that would provide an even broader frame on the subject under examination.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethical clearance was granted by the Group in Socio-Educational Action Research (GIAS, HUM929). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LT-Z: Visualization, Project administration, Investigation, Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities from the Government of Spain under grant for University Teacher Training (Ayudas para la Formación del Profesorado Universitario, FPU) (Ref. FPU20/01888, 2020).

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my thanks to Vicente Llorent-Bedmar for his guidance during the research process. His expertise and knowledge have been helpful in the development of this work. I would also like to acknowledge the valuable work developed by our translator Ahmed Baba Mounir and extend my appreciation to him. He has helped us with his valuable advice, translations and the opportunity to fully engage with the Moroccan Community in Seville.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^During Holy Week, religious icons/statues representing the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Christ are taken through the streets in procession. This celebration, although religious, is currently rooted in the Spanish culture. Moreover, this festivity has a bigger strength/presence in Andalusia, especially in the area of Seville.

References

Abu Khalaf, N., Woolweaver, A. B., Reynoso Marmolejos, R., Little, G. A., Burnett, K., and Espelage, D. L. (2022). The impact of Islamophobia on Muslim students: a systematic review of the literature. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 52, 206–223. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2022.2075710

Adams, W. C. (2015). “Conducting semi-structured interviews,” in Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, eds. K. E. Newcomer, H. P. Hatry, and J. S. Wholey, (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 492–505.

Alibhai-Brown, Y., Allen, C., Cantle, T., and Mitchell, D. S. (2006). Multiculturalism: a failed experiment? Index Censorship 35, 91–99. doi: 10.1080/03064220600744750

Ayala, M. C., Webb, A., Maldonado, L., Canales, A., and Cascallar, E. (2024). Teacher's social desirability bias and migrant students: a study on explicit and implicit prejudices with a list experiment. Soc. Sci. Res. 119:102990. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2024.102990

Bayrakly, E., and Hafez, F. (2023). European Islamophobia Report 2023. Austria: Leopold Weiss Institute.

Bergen, D. D., Feddes, A. R., and de Ruyter, D. J. (2021). Perceived discrimination against Dutch Muslim youths in the school context and its relation with externalising behaviour. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 47, 475–494. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2020.1862779

Boland, C. (2020). Hybrid identity and practices to negotiate belonging: Madrid's Muslim youth of migrant origin. CMS 8:26. doi: 10.1186/s40878-020-00185-2

Colak, F. Z., Van Praag, L., and Nicaise, I. (2020). ‘Oh, this is really great work—especially for a Turk': a critical race theory analysis of Turkish Belgian students' discrimination experiences. Race Ethn. Educ. 26, 623–641. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2020.1842351

Collet-Sabé, J. (2020). Religious discrimination in young Muslim assimilation in Spain: contributions to Portes and Rumbaut's segmented assimilation theory. Social Compass 67, 599–616. doi: 10.1177/0037768620948476

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th Ed. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Darwin Holmes, A. G. (2020). Researcher positionality: a consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research - a new researcher guide. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 8, 1–10. doi: 10.34293/education.v8i4.3232

Davies, T. (2023). ‘But we're not a multicultural school!': locating intercultural relations and reimagining intercultural education as an act of ‘coming-to-terms-with our routes'. Aust. Educ. Res. 50, 991–1005. doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00537-0

Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in Education: A Theoretical and Methodological Toolbox. Helsinki: Palgrave Pivot London.

Edgeworth, K. (2014). Black bodies, white rural spaces: disturbing practices of unbelonging for ‘refugee' students. Crit. Stud. Educ. 56, 351–365. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2014.956133

Encuesta de Población Activa (2022). Marroquíes en la Provincia de Sevilla. Padrón municipal 2022, cifras de población. EPA. Available online at: https://epa.com.es/espa%C3%B1a/ (Accessed May 23, 2025).

Farooqui, J. F., and Kaushik, A. (2020). Growing up as a Muslim youth in an age of Islamophobia: a systematic review of literature. Contemp. Islam 16, 65–88. doi: 10.1007/s11562-022-00482-w

Franken, L. (2017). Coping with diversity in religious education: an overview. J. Beliefs Values 38, 105–120. doi: 10.1080/13617672.2016.1270504

Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through cultural diversity. Curric. Inq. 43, 48–70. doi: 10.1111/curi.12002

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd Ed. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Ghosh, R. (2018). The potential of the ERC program for combating violent extremism among youth. Relig. Educ. 45, 370–386. doi: 10.1080/15507394.2018.1546509

Gorski, P. C., and Parekh, G. (2020). Supporting critical multicultural teacher educators: transformative teaching, social justice education, and perceptions of institutional support. Intercult. Educ. 31, 265–285. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2020.1728497

Graham, S., Kogachi, K., and Morales-Chicas, J. (2022). Do I fit in: race/ethnicity and feelings of belonging in school. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 2015–2042. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09709-x

Haynes, J. (2019). Introduction: the “clash of civilizations” and relations between the West and the Muslim world. Rev. Faith Int. Aff. 17, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/15570274.2019.1570756

Hillier, C. (2014). ‘But we're already doing it': Ontario teachers' responses to policies on religious inclusion and accommodation in public schools. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 60, 43–61. doi: 10.55016/ojs/ajer.v60i1.55760

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2022a). Cifras de Población (CP) a 1 de julio de 2022 Estadística de Migraciones (EM). Primer semestre de 2022 Datos provisionales. INE. Available online at: https://www.ine.es/prensa/cp_j2022_p.pdf (Accessed June 11, 2025).

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2022b). Principales series de población desde 1998: Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, provincias, Sexo y Año. INE. Available online at: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t20/e245/p08/l0/&file=03005.px#_tabs-tabla (Accessed June 11, 2025).

Ipgrave, J. (2010). Including the religious viewpoints and experiences of Muslim students in an environment that is both plural and secular. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 11, 5–22. doi: 10.1007/s12134-009-0128-6

Iwai, Y. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching in a global era: using the genres of multicultural literature. Educ. Forum 83, 13–27. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2018.1508529

Jaffe-Walter, R. (2013). ‘Who would they talk about if we weren't here?': Muslim youth, liberal schooling, and the politics of concern. Harv. Educ. Rev. 83, 613–635. doi: 10.17763/haer.83.4.b41012p57h816154

Keddie, A., Wilkinson, J., Howie, L., and Walsh, L. (2019). ‘…we don't bring religion into school': issues of religious inclusion and social cohesion. Aust. Educ. Res. 46, 1–15. doi: 10.1007/s13384-018-0289-4

Koukounaras-Liagkis, M. (2015). Religion and religious diversity within education in a social pedagogical context in times of crisis: can religious education contribute to community cohesion? Int. J. Soc. Pedagogy 4:7. doi: 10.14324/111.444.ijsp.2015.v4.1.007

Llorent-Bedmar, V., Torres-Zaragoza, L., and Sánchez-Lissen, E. (2023). The use of religious signs in schools in Germany, France, England and Spain: The Islamic Veil. Religions 14:101. doi: 10.3390/rel14010101

May, S., and Sleeter, C. E. (2010). Critical Multiculturalism: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Memon, N. A., and Chown, D. (2023). Being responsive to Muslim learners: Australian educator perspectives. Teach. Teach. Educ. 133:104279. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104279

Ministry of Education and Professional Training (2022). Royal Decree 157/2022, which establishes the organization and basic teachings of Primary Education. BOE No. 52. Available online at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2022/03/01/157/con (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (2013). Provisional application of the Strategic Partnership Agreement on Development and Cultural, Educational and Sports Cooperation between the Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of Morocco, done ‘ad referendum' in Rabat on the 3rd of October 2012. BOE No. 182. Available online at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/ai/2012/10/03/(2) (Accessed May 23, 2025).

Ministry of the Presidency Justice and Relations with the Courts. (1992). Law 26/1992 approving the State Cooperation Agreement with the Islamic Commission of Spain. BOE No. 272. Available online at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1992/11/10/26/con (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Ministry of the Presidency Justice and Relations with the Courts. (2020). Organic Law 3/2020 which amends Organic Law 2/2006, of 3rd May on Education. BOE No. 340. Available online at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Mourad, Z. (2022). ‘Her scarf is a garbage bag wrapped around her head': Muslim youth experiences of Islamophobia in Sydney primary schools. Ethnicities 23, 46–63. doi: 10.1177/14687968211069192

Narain, V. (2012). “Critical multiculturalism,” in Feminist Constitutionalism: Global Perspectives, eds. B. Baines, D. Barak-Erez, and T. Kahana (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 377–392.

Niemi, P.-M., Kuusisto, A., and Kallioniemi, A. (2014). Discussing school celebrations from an intercultural perspective: a study in the Finnish context. Intercult. Educ. 25, 255–268. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2014.926143

Olmos-Alcaraz, A. (2020). Racismo, racialización e inmigración: aportaciones desde el enfoque de(s)colonial para el análisis del caso español. Rev. Antropol. 63:1–23. doi: 10.11606/2179-0892.ra.2020.170980

Parker, J. S., Murray, K., Boegel, R., Slough, M., Purvis, L., and Geiling, C. (2023). An exploratory study of school psychology students' perceptions of religious and spiritual diversity training in their graduate programs. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 27, 370–385. doi: 10.1007/s40688-021-00396-z

Pearce, S., and Lewis, K. (2018). Changing attitudes to cultural difference: perceptions of Muslim families in English schools. Camb. J. Educ. 49, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2018.1427217

Qadir, H., and Islam, N. U. (2023). “An integrated approach of multiculturalism and religious diversity,” in The Role of Faith and Religious Diversity in Educational Practices, ed. J. DeHart (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 188–204.

Quijada-Cerecer, P. D., and Alvarez-Gutiérrez, L. (2010). “Critical multiculturalism: transformative educational principles and practices,” in Social Justice Pedagogy Across the Curriculum, 1st Edn. eds. T. K. Chapman and N. Hobbel (New York, NY: Routledge), 144–163.

Ramlackhan, K., and Catania, N. (2022). Fostering creativity, equity, and inclusion through social justice praxis. Power Educ. 14, 282–295. doi: 10.1177/17577438221114717

Revell, L. (2009). Religious education, conflict and diversity: an exploration of young children's perceptions of Islam. Educ. Stud. 36, 207–215. doi: 10.1080/03055690903162390

Rissanen, I. (2018). Negotiations on inclusive citizenship in a post-secular school: perspectives of “cultural broker” Muslim parents and teachers in Finland and Sweden. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 64, 135–150. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2018.1514323

Rissanen, I. (2019). School principals' diversity ideologies in fostering the inclusion of Muslims in Finnish and Swedish schools. Race Ethn. Educ. 24, 431–450. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2019.1599340

Rodríguez-Reche, C., and Cerchiaro, F. (2023). The everyday dimensions of stigma: Morofobia in everyday life of daughters of Maghrebi-Spanish couples in Granada and Barcelona (Spain). Ethnicities 23, 886–904. doi: 10.1177/14687968231169269

Romijn, B. R., Slot, P. L., and Leseman, P. P. M. (2021). Increasing teachers' intercultural competences in teacher preparation programs and through professional development: a review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 98:103236. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103236

Shirazi, R. (2018). ‘I'm supposed to feel like this is my home': testing terms of sociopolitical inclusion in an inner-ring suburban high school. J. Educ. Adm. 56, 519–532. doi: 10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0009

Shirazi, R., and Jaffe-Walter, R. (2020). Conditional hospitality and coercive concern: countertopographies of Islamophobia in American and Danish schools. Comp. Educ. 57, 206–226. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2020.1812234

Subasi Singh, S. (2022). Enriching or challenging? The attitudes of Viennese teachers towards religious diversity in urban schools. Intercult. Educ. 33, 526–539. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2022.2144116

Tempel, T. (2022). Asking about inclusion: question order and social desirability influence measures of attitudes towards inclusive education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 38, 909–915. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2162666

Torres-Zaragoza, L., and Llorent-Bedmar, V. (2024). Barriers to inclusion of Muslim migrant students in western schools. A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2024.102363

Unión de Comunidades Islámicas de España (2024). Estudio demográfico de la población musulmana. Available online at: https://ucide.org/islam/observatorio/informes/ (Accessed May 23, 2025).

Vilà Baños, R., Freixa-Niella, M., Sánchez-Martí, A., and Rubio-Hurtado, M. J. (2019). Head teachers' attitudes towards religious diversity and interreligious dialogue and their implications for secondary schools in Catalonia. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 42, 180–192. doi: 10.1080/01416200.2019.1584742

Wang, J. S., Lan, J. Y. S., Khairutdinova, R. R., and Gromova, C. R. (2022). Teachers' attitudes to cultural diversity: results from a qualitative study in Russia and Taiwan. Front. Psychol. 13:976659. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.976659

Keywords: inclusive education, cultural diversity, religious diversity, Muslim students, religious-blindness, intercultural competence

Citation: Torres-Zaragoza L (2025) Moroccan Muslim students' cultural and religious diversity recognition in Spanish schools. A critical multiculturalism analysis from their mothers' perspectives. Front. Educ. 10:1649446. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1649446

Received: 18 June 2025; Accepted: 31 July 2025;

Published: 25 August 2025.

Edited by:

Jiayi Wang, De Montfort University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Macarena Machin Alvarez, University of Cadiz, SpainSisca Rahmadonna, Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Rizal Darwis, IAIN Sultan Amai Gorontalo, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Torres-Zaragoza. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lucia Torres-Zaragoza, bHRvcnJlczNAdXMuZXM=

Lucia Torres-Zaragoza

Lucia Torres-Zaragoza