- UCSI University, Cheras, Malaysia

In the field of teacher education identity conflict and role conflict frequently emerge. Conflict arises not only within the identity system or the role system but also between identity and role, manifesting as a misalignment between cognitive commitments and behavioral expectations. This phenomenon is termed cross conflict between identity and role. Through a systematic review of 117 high-quality Chinese and English studies the theoretical meanings of profession role and identity are clearly delineated and the concept of Identity-Role Consistency is advanced as a novel construct for assessing the significance and feasibility of internal professional conflict among teachers. Identity-Role Consistency denotes the degree of congruence between a teacher’s sense of professional identity and the expectations of their role and holds promise as a quantifiable indicator of teacher psychological well-being. The study further introduces self authenticity to emphasize individual traits and integrates it critically with Identity-Role Consistency.

1 Introduction

Amid the wave of contemporary educational transformation, teachers, as the core carriers of knowledge transmission, are facing an increasingly complex identity and role. From a longitudinal perspective, the traditional role of teachers requires a solid theoretical foundation, positioning them as the central conduit for knowledge transfer (Jan, 2017). This role emphasizes a technology driven approach and standardized teaching processes while limiting teachers’ decision making power in the classroom (Tezgiden Cakcak, 2016). With the accelerated progress of the digital era and the rapid development of AI tools, societal expectations for teachers have become more intricate. Teachers are now expected to serve as creators and guardians of morality and values (Yu, 2024) and to engage emotionally with students, becoming their “Friend plus” (Gao and Cui, 2024). The increasing complexity of role expectations has inevitably shaped the evolution of teacher identity (Sachs, 2001). The interplay of policy changes, technological advancements, and societal expectations forces teachers to constantly navigate between multiple identities, including “educator,” “learner,” and “academic paper producer” (Zhang, 2022; Levin and Liu, 2018). Macfarlane (2016) argues that this fragmented identity narrative may not fundamentally challenge the philosophical question of “Am I a teacher?” However, external support and feedback remain essential for the coherent development of teachers’ professional identity (Kaasila et al., 2021).

From a cross sectional perspective, the increasing complexity of roles and the fragmentation of identity lead to corresponding conflicts between roles and identities. For Chinese preschool teachers with postgraduate degrees, these conflicts are particularly pronounced, as they often struggle with multiple identity tensions, such as being both a “caregiver” and a “janitor,” a “like minded companion” and a “lonely wanderer,” as well as an “eager achiever” and a “frustrated learner” (Fan et al., 2023). These conflicts arise not only within their professional roles but also extend to their personal lives (Moore, 1992). Similarly, for preschool teachers, excessive work pressure encroaches on their personal time, making it difficult for them to maintain a work-life balance (Le, 2024). While conflicts between identity and role are often inevitable, they can sometimes serve as opportunities for professional growth (Tsui, 2007). However, the nature of these conflicts varies depending on their source (Burke and Tully, 1977). Despite many researchers claiming to study either identity or role, the long-standing academic tendency to conflate these concepts, along with their inherent conceptual ambiguity, has made it difficult to clearly identify the sources of such conflicts (Weng et al., 2024; Do and Hoang, 2024). Furthermore, although identity and role are closely interconnected (Stryker, 2001), few studies have conducted a comprehensive analysis of their relationship, limiting the overall value of existing research.

Building on the discussion of the research landscape and existing issues, this study will explore identity conflict and role conflict as key entry points to examine the following questions:

1. The precise definitions of identity conflict and role conflict, as well as the distinctions between them.

2. The practical foundations of Identity-Role Consistency in the teaching profession, and the theoretical interplay between Self authenticity and Identity-Role Consistency.

2 Research method

2.1 Literature search

Following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Tugwell and Tovey, 2021), this study conducted a literature search using both Chinese and English core academic databases. The search covered the period from 2015 to July 2025 and was sorted by relevance. The search terms included teacher identity conflict, teacher role conflict, and self authenticity. Each keyword was searched independently to avoid cross-interference among terms. When search results exceeded 100 entries, only the top 100 most relevant articles were retained. For English language sources, the Scopus database was used, with the search limited to articles in which the specified terms appeared as keywords. For Chinese language sources, the CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) database was used. To ensure the quality of Chinese literature, the search was further restricted to journals listed in the CSSCI (Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index) core journal directory and the Peking University core journal directory.

2.2 Literature screening

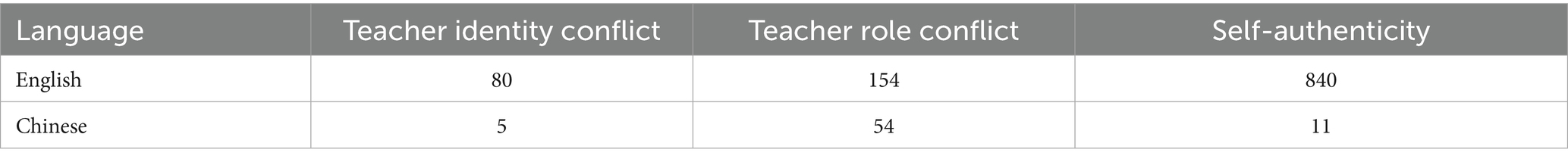

Based on the search procedure described above, the initial retrieval yielded a total of 1,144 articles in both Chinese and English. After preliminary filtering, 350 articles were retained as valid literature (see Table 1 for detailed search results).

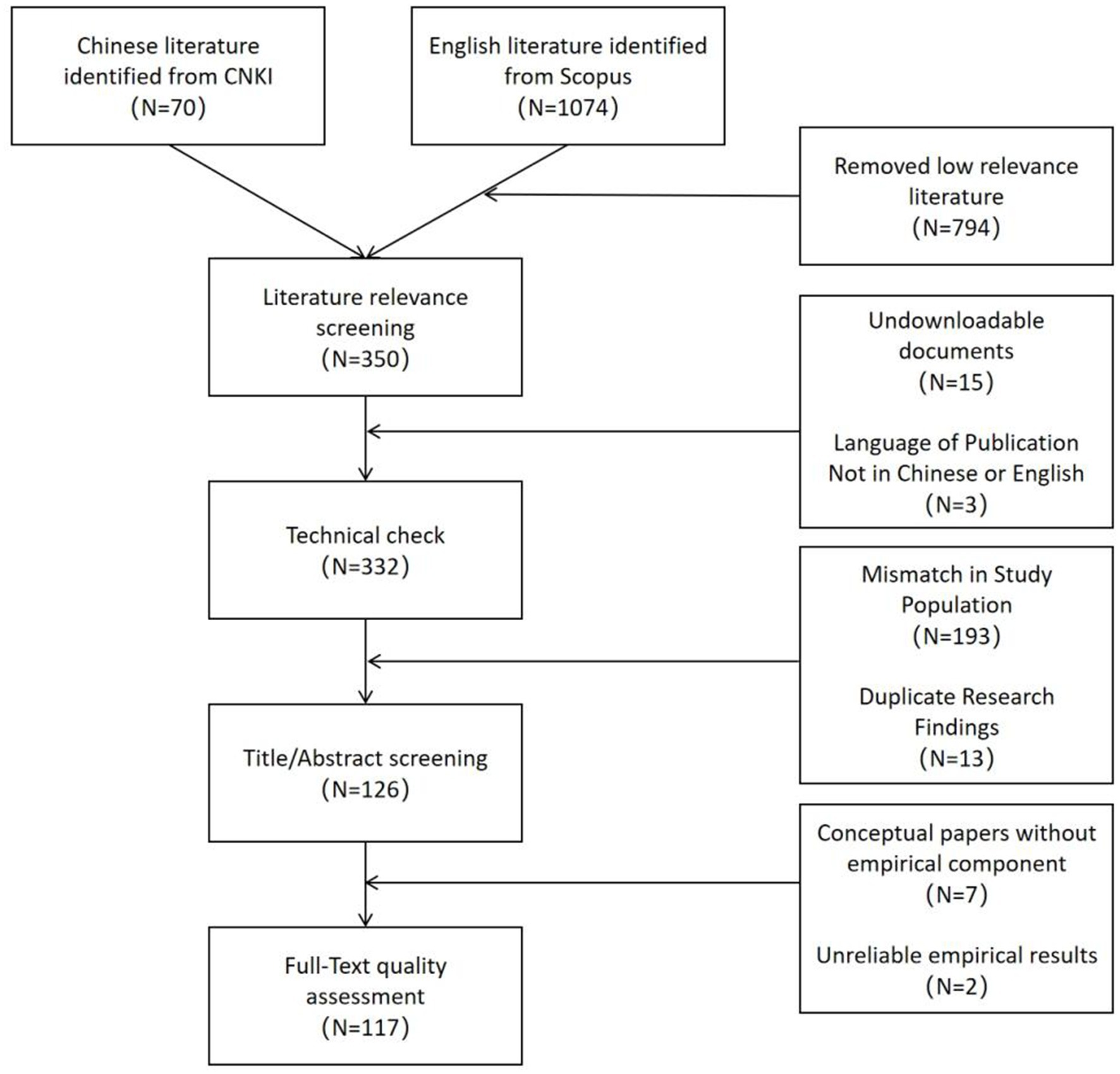

The retained articles then underwent three rounds of screening. The first round involved a technical screening to eliminate articles that were inaccessible in full text or not written in either English or Chinese. After this stage, 332 articles remained, representing a 5% reduction from the initial pool. The second round focused on screening titles and abstracts. In this phase, researchers independently evaluated the abstracts to exclude duplicate studies, studies that did not focus on teacher populations, and those that addressed general professional groups outside the educational field. After this round, 126 articles were retained. The third round involved full-text assessment. Researchers applied pre-established inclusion criteria to identify articles that were directly relevant to the study’s core themes. Studies were excluded if they lacked a clear connection to the research objectives, displayed weak research design, or were non-empirical or non-systematic reviews (The screening process is shown in Figure 1).

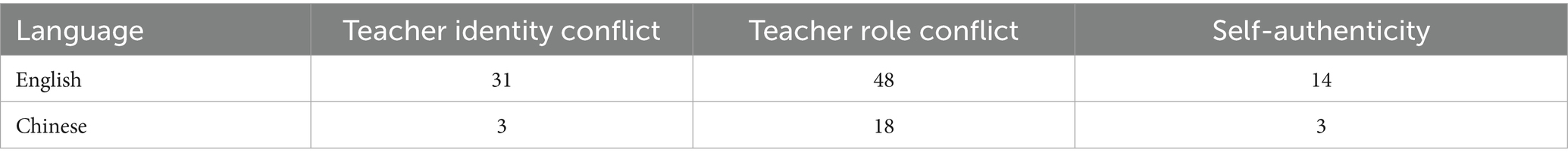

Following this three-step screening process, a total of 117 core articles were selected for subsequent conceptual analysis and model development (see Table 2 for detailed screening results). For detailed literature information, please refer to the Supplementary Material.

2.3 Data extraction

Following the screening of core literature, a systematic data extraction process was conducted in accordance with the principles of systematic review methodology, to ensure both comprehensiveness and consistency of information. A standardized semi-structured coding sheet was used for data extraction. The extraction was independently carried out by the researchers and covered three primary dimensions. First, basic bibliographic information was recorded, including the author(s), year of publication, and journal name. Second, the type of study was identified (such as qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, or systematic review), along with the specific methodological approach employed (such as survey, interview, case study, among others). The complexity and rigor of each study’s research design were also evaluated. Third, the core findings and arguments of each article were extracted, with particular attention given to studies addressing the intersection of identity conflict and role conflict. This included studies that may have unintentionally conflated the two concepts. To ensure consistency in terminology and clarity in the extraction process, a detailed coding manual was developed by the researcher. Data were organized and analyzed using Excel.

3 The specific conceptual dimensions of the term “teacher”

Teachers are the intersection of institutional, personal, and societal forces. Therefore, when we talk about the term “teacher,” its meaning generally points to three aspects: profession, identity, and role. These correspond to the institutional framework, self-identity, and societal expectations, respectively, providing a more comprehensive explanation of the real significance of being a teacher and helping to answer the question: “Who is a teacher?”

3.1 Profession

The occupational dimension represents the most direct semantic interpretation of the term “teacher” and serves as an instrumental carrier for the social positioning of teachers, namely identifying an individual as someone who makes a living through teaching. This dimension encompasses three key characteristics: professionalism, institutionalization, and economic attributes.

Professionalism signifies that teachers must possess a specific knowledge and skill system, which includes content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge (Kulgemeyer and Riese, 2018), and practical knowledge (Elbaz, 1981)—the personalized wisdom developed through concrete teaching situations. This knowledge structure is typically acquired through formal institutional training, whereas higher-order practical wisdom emerges gradually through continuous teaching reflection (Schön, 1983). Contemporary research further differentiates two aspects of teacher professionalism: one oriented toward the teaching process, addressing the “what to teach/how to teach” professional competence, and another concerning professional ethics, which governs the “why to teach” aspect of the profession (Campbell, 2003).

The institutional dimension is realized through a dual mechanism of state governance and social contract. From an access perspective, teacher certification systems establish a minimum threshold for professionalism (Hedrick-Shaw, 2024), while long term employment policies provide a continuous quality assurance mechanism. Legally, various U. S. states have enacted legislation such as the Teacher Professional Responsibility Law to define the rights and obligations of teachers (Umpstead et al., 2013). Mead (2012) argues that such institutional frameworks serve both empowering functions (e.g., safeguarding academic freedom) and regulatory purposes (e.g., enforcing professional conduct). This institutionalization renders teaching not merely an individual career choice but also a legally defined position within the broader social division of labor.

The economic dimension exhibits a dual structure comprising both explicit and implicit components. Explicitly, it manifests in the salary system governed by labor contracts (Sun et al., 2024), while implicitly, it involves psychological capital gains, such as professional identity, and teaching efficacy which constitute non-material benefits (Mudhar et al., 2024). This dual compensation mechanism explains a seemingly paradoxical phenomenon: even in unpaid teaching engagements, participants can still attain potential economic returns by accumulating teaching experience and reinforcing professional commitment. From the perspective of social exchange theory, the economic dimension of the teaching profession essentially involves the transformation of knowledge capital and social capital into value (Bourdieu, 2018). This underscores that the professional framework of teaching not only provides the material foundation for individual career development but also establishes the institutional boundaries that define teachers’ social identity, offering structural support for their professional self conception.

3.2 Role

In Goffman’s seminal work, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Goffman, 2023), dramaturgical theory employs a theatrical metaphor to deconstruct social interaction, defining role as a strategic practice through which individuals actively construct social reality via symbolic performance. Goffman argues that the essence of a role lies not in a static identity label but in a dynamic performance—a carefully orchestrated enactment in which individuals utilize linguistic, gestural, and sartorial symbols to shape how others perceive their social identity. This performance is not a unidirectional act but an ongoing adjustment based on audience reactions. A crucial aspect of this process is the establishment of working consensus, where both parties in an interaction maintain an implicit agreement to preserve surface level harmony, even if they tacitly recognize the performative nature of the exchange. For example, students may cooperate with a teacher’s enactment of knowledge authority to uphold classroom order, while teachers may, in turn, tolerate students concealing certain thoughts to prevent overt role conflicts (Goffman, 2023). However, such consensus fundamentally operates as a moral contract. Individuals must at least outwardly adhere to the roles they claim to embody, or they risk discrediting their performance. This also explains why social norms become internalized as an implicit framework for role performance. Mead (2015), in Mind, Self, and Society, emphasizes the concept of the generalized other, which operates through this interactive feedback mechanism, compelling individuals to internalize societal expectations. Thus, role performance is simultaneously an act of self expression and a response to the gaze of others.

From Merton’s (1957) perspective, a single social status is associated with multiple roles, forming a role set, which serves as the primary source of complexity in the teacher’s role. Divergent social expectations both within a single role and across multiple roles can generate a complex network of influences, leading to a conceptual distinction within the role set between intra-role systems and inter-role systems (Herman and Gyllstrom, 1977). The teaching role, as a prototypical intra-role system, delineates societal expectations regarding what a teacher ought to be, thereby establishing normative behavioral frameworks for educators. In most cases, however, these normative expectations are dynamic and evolve in response to changing contextual and temporal conditions (Clarke, 1997). In contemporary settings, teachers must navigate multiple roles, such as knowledge creators (Holt-Reynolds, 2000), users of digital tools (Wake et al., 2007), managers, and facilitators (Archana and Rani, 2017). Adapting role presentation strategies based on situational demands exemplifies the dynamic accommodation of what Parsons (2013) describes as pattern variables, illustrating how teachers align individual behaviors with social norms. However, the roles teachers are expected to fulfill often lack clear boundaries, leading to the cognitive dilemma of “What exactly is my job?” A phenomenon known as role ambiguity (Homayed et al., 2025). The frequent iterations of educational reform continuously impose new roles on teachers without providing adequate time and emotional support for adaptation (Day, 2002). This, in turn, results in an excessive fragmentation of role perception and contributes to occupational burnout.

3.3 Identity

Identity refers to an individual’s cognition and recognition of “who I am” as shaped through social interactions. The theoretical construction of identity involves the dynamic interplay among individual cognition, social interaction, and professional practice. From the perspective of social constructivism, teacher identity is not a fixed attribute but rather a dynamic process shaped through ongoing professional practice and social negotiation (Coldron and Smith, 1999). This process entails the integration of personal experiences, values, and institutional norms to construct a professional self-concept (Beijaard et al., 2004). Wenger’s (1999) theory of communities of practice further highlights that teachers establish their identity within specific cultural contexts through three modes: participation, imagination, and alignment. This identity formation is influenced by the organizational structures of schools while simultaneously contributing to innovations in educational practice.

Identity theory also acknowledges the existence of multiple identity systems, similar to the concept of “role sets.” This system is divided into two parts, the first emphasizes the parallel influence of multiple identities, such as gender, race, and class, referred to as intersectional identity (Crenshaw, 2022; Kanno and Kangas, 2024). The second refers to identity groups formed on the basis of shared characteristics, known as collective identity (Tajfel et al., 1979). The teacher identity collective examined in this study mainly aligns with the latter paradigm. Akkerman and Meijer’s (2011) research suggests that teacher professional identity is not a singular, static label but rather a complex system composed of multiple sub-identities, including those of a teaching practitioner, subject expert, and organizational member. The transition from novice to expert teacher is essentially a professional socialization process in which multiple identities are continuously integrated and reconstructed (Day et al., 2006). The process of identity integration and transformation requires teachers to actively navigate various conflicts, striking a delicate balance between agency and social reform, ultimately forming a mature identity system (Wang K. et al., 2024). In actual teaching practices, identity is not always overtly expressed. Teachers may emphasize different identities based on cultural and social contexts as well as personal inclinations. When an identity becomes more salient, its influence on behavior becomes more pronounced (Garner and Kaplan, 2019; Stryker and Serpe, 1994). This selection process is often constrained by external conditions, representing the situational self (Brenner et al., 2014), indicating that unconscious identity choices may be less autonomous than they appear. However, identity shifts occur more rapidly than role transitions. For example, language teachers may switch between multiple salient identities within a single lesson to achieve desired instructional outcomes (Raman and Yiğitoğlu, 2018). While such a fragmented identity structure allows teachers to adapt to complex teaching demands, it simultaneously undermines solidarity among educators, particularly under the influence of social media (González-Calvo, 2025).

3.4 Distinction and interrelation of concepts

From a holistic perspective, profession, role, and identity form a concentric circle structure (see Figure 2). The outermost layer is the professional layer, which defines the broadest extension when we refer to the term “teacher.” The role layer, positioned in the middle, represents the specific behaviors exhibited by teachers within the professional system and serves as the key point where institutional norms are transformed into individual actions. The core layer is the identity layer, reflecting the individualized understanding of the profession by teachers and the process of shaping their teaching values.

In the process of teachers’ professional development, the professional framework often becomes a key source of role expectations. Professionalism demands that teachers engage in lifelong learning and continuously develop their teaching competencies (Batista et al., 2024). Institutional expectations require teachers to carry out their teaching responsibilities in accordance with laws and regulations, fulfilling obligations defined by both policy and culture (Ball, 2003). From an economic perspective, with the exception of a small number of “star teachers” in shadow education, most frontline educators do not enjoy particularly high income levels (Guo, 2022). As a result, teachers are often required to adjust their psychological expectations and behaviors within the paradox of the “sanctified teacher,” balancing economic rewards with intrinsic and symbolic gains. From a cross-sectional perspective, roles and identities take on a modular structure at any given moment. Prominent sub-roles and sub-identities reflect a teacher’s behaviors and cognitions at specific points in time, together forming a complete teaching persona. Therefore, it can be argued that a teacher must align role (behavior) and identity (cognition) in order to ensure effective teaching practices. From a longitudinal perspective, however, the development of roles and identities may become misaligned at certain stages. For instance, in the early stages of a novice teacher’s career, there is often an imbalance between identity and role development. After entering the profession, beginning teachers begin to reconstruct their professional identity and may believe they are capable of fulfilling teaching duties. Yet, their role development tends to progress more slowly, and their actual teaching practices often fall short of their expectations (Seyri and Nazari, 2023). This misalignment can lead to internal conflict, ultimately affecting their teaching performance.

4 Conflict between identity and role

The fragmentation of roles and identities leads to conflicts among substructures. Traditional research paradigms have thoroughly examined these conflicts within individual structures (Ghiasvand et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2022). However, based on the construction results of the aforementioned model, we can integrate the discussion of both types of conflicts, allowing for a more detailed analysis of their patterns and impacts.

4.1 Characteristics of the literature

From an overall perspective, there is a noticeable methodological divergence between studies on identity and those on role. Among empirical studies excluding reviews, there are 29 identity-related studies, of which 26 adopt qualitative methods, accounting for 89.7%. In contrast, there are 46 empirical studies related to roles, of which 34 adopt quantitative methods, accounting for 73.9%. This phenomenon is primarily due to the limited availability of reliable and valid scales for investigating teacher identity (Steinberger and Magen-Nagar, 2017), and the complex interactions among multiple dimensions and sub-identities, which make standardized measurement challenging (Ren and Pan, 2025; Tajeddin and Nazari, 2025). On the other hand, role theory and role conflict are supported by objective and observable behaviors and expectations, and their theoretical frameworks have given rise to several well-established scales (Iannucci et al., 2019; Shukla and Srivastava, 2016). These are suitable for large-scale application, which has facilitated the widespread use of quantitative research. However, the limited number of mixed-methods studies, quantitative studies on identity, and qualitative studies on roles may suggest the methodological necessity of employing mixed methods in research that appears to bridge the seemingly opposing theoretical foundations of identity and role.

In addition, the studies included in the review cover 27 countries and regions worldwide, demonstrating that this research issue arises in educational work across diverse cultural contexts. However, despite the sufficient number of research projects, a considerable portion of researchers have not strictly distinguished between the concepts of identity and role for various reasons (Seifert and Cucchiara, 2024). The most common situation is the lack of clear categorization when analyzing sub-identities and sub-roles, often grouping them simply under either role or identity for convenience (Li et al., 2020). Fortunately, some studies have thus touched upon the conflicts between identity and role, allowing us to glimpse the outlines of emerging concepts.

4.2 Identity conflict and role conflict

Identity conflict refers to the state in which an individual’s multiple identities come into contradiction or clash (Liu et al., 2025). When teachers hold personal beliefs and values while simultaneously embodying the professional role expectations of an educator, the demands of these identities may be inconsistent. Scholars have likened identity conflict to subordinate identities congregating like a choir, in which certain identities remain more central than others (Ghiasvand et al., 2023). In other words, identity conflict arises when the various self-conceptions formed at the professional, familial, and personal levels are at odds with one another. For example, if a teacher is compelled to teach in a manner that contravenes their personal principles (albeit in compliance with institutional requirements), they will experience a dissonance in their professional identity (Yang et al., 2022). Thus, teachers’ professional identity conflict typically denotes the range of tensions that emerge when their beliefs, values, experiences, and occupational expectations are misaligned, with the core of the conflict situated in the teacher’s cognitive appraisal of their profession.

Role conflict, by contrast, denotes the clash that occurs when an individual simultaneously occupies multiple roles whose associated behavioral expectations are incompatible (Khanal and Ghimire, 2024). Theoretically grounded in the framework of role theory, research on role conflict emphasizes how societal expectations for divergent behaviors exert pressure on the individual, often manifesting as stress over role transitions and boundary maintenance. Coverman (1989) defines role conflict as arising when the pressures encountered in one role are mutually incompatible with those emerging in another role. Role conflict can be subdivided into inter-role conflict (stemming from inconsistent demands across different roles), and intra-role conflict (the tension generated by divergent expectations within the same role; Lipsky et al., 2017). When an individual’s multiple roles cannot be effectively reconciled, role conflict ensues, the crux of which lies in the complexity and inconsistency of societal expectations regarding the teacher’s conduct.

4.3 Practical implications of cross domain conflict

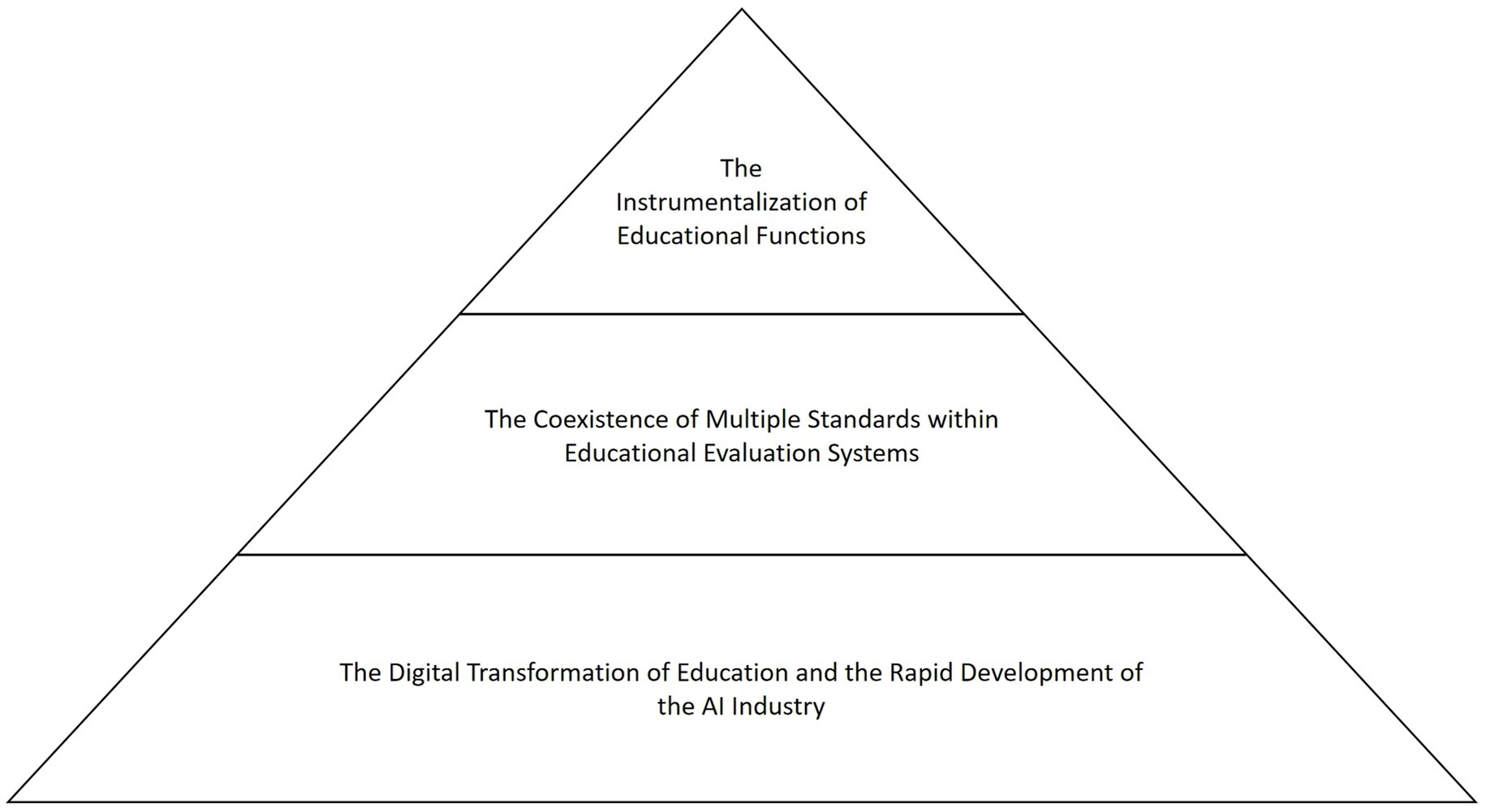

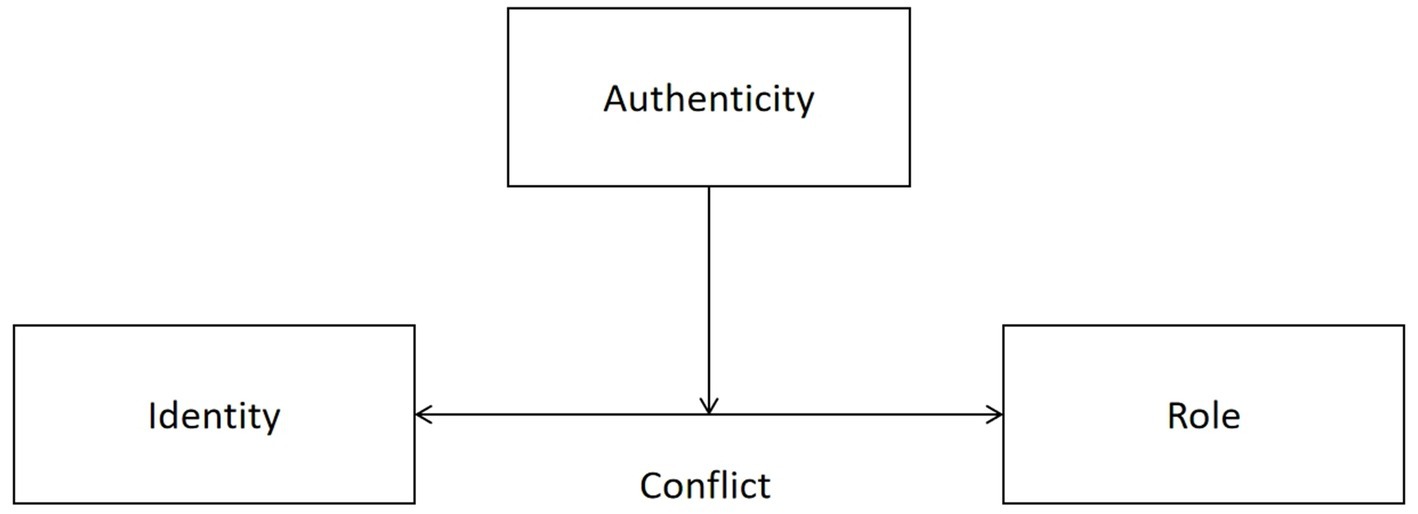

Based on the previously defined concepts of identity and role, we have observed instances of intersectional conflict between these two constructs in both teaching and research practices. From an external perspective, the core of such intersectional conflict can be understood as a misalignment between teachers’ internal psychological self perception and the normative expectations imposed by society. Existing research suggests that the mechanisms underlying these conflicts operate on three primary levels (see Figure 3).

First, the instrumental positioning of education within the broader social system leads to the alienation of the teacher’s role script. Specifically, the emphasis on quantifiable educational outcomes has undermined the value-oriented dimensions of education itself (Biesta, 2015; Ball, 2003), resulting in a shift away from teachers’ original, idealistic beliefs about the moral and transformative power of education. In recent decades, education has increasingly been subordinated to economic and administrative objectives. This phenomenon widely recognized in academia as neoliberal instrumentalism. This external framing of education as a tool for serving societal functions erodes teachers’ own educational values and identity by constraining pedagogical methods and instructional goals (Naz and Beighton, 2024). As Clarke (2023) notes, four decades of neoliberal policy have driven the commodification and instrumentalization of education, allowing neoliberal values (such as individualism, commodification, and competitive evaluation) to permeate the teaching profession (González-Calvo, 2025). According to cognitive dissonance theory (Miller et al., 2015), inconsistencies between beliefs and behaviors can produce psychological discomfort. Teachers caught in such conflicts may either acquiesce to the demand for measurable results or experience diminished morale and professional burnout. In either case, the original meaning and purpose teachers ascribe to their work becomes eroded by external instrumental demands (Zhang, 2025).

Second, the coexistence of multiple standards within educational evaluation systems, coupled with policy ambitions to cultivate all round or omnipotent teachers, reflects a strong utilitarian tendency (Yang, 2025), which often clashes with teachers’ personal understanding of their profession. These systems frequently adopt multidimensional criteria to assess teacher quality (Jiang, 2025). While theoretically designed to comprehensively evaluate performance, in practice such evaluations often reduce teaching to measurable outputs. Conflicts emerge when teachers’ professional self-identities do not align with the prescribed indicators. Contemporary evaluation frameworks tend to emphasize student performance in relation to predetermined benchmarks (Jiang, 2025), yet experienced teachers may prioritize igniting students’ passion for learning or meeting their socio-emotional needs, dimensions that are not easily captured by narrow, exam-driven metrics. From the perspective of self-determination theory, individuals are motivated when their needs for autonomy and competence are met (Deci and Ryan, 1985). Utilitarian evaluation practices frequently undermine teachers’ autonomy and neglect intangible competencies, thereby eroding intrinsic motivation. The resulting gap between the “teacher as I see myself” and the “teacher as evaluated” can lead to stress, alienation, and even identity reconstruction.

Third, digital transformation has redefined the teacher’s role from a traditional knowledge authority to a facilitator of learning, requiring educators to proactively adapt to the decentralization of knowledge (Selwyn, 2021a). In the pre-digital era, teachers typically served as the primary source of disciplinary knowledge in the classroom. Today, students have immediate access to vast amounts of information, and classrooms are increasingly populated with online modules and AI-powered tutors. This decentralization challenges the traditional identity of teachers as sages on the stage. While digital tools can empower instruction, they also expose teaching to the logic of commercial platforms and performance metrics (Selwyn, 2021b). More directly, AI-driven search and learning platforms enable students to independently access information with increasing frequency. Hu and Shi (2018) argue that in the era of AI, the teacher’s role as a knowledge authority is being directly challenged, as artificial intelligence can rapidly deliver vast information, thereby diminishing the teacher’s position as the sole content provider. Similarly, Gao (2025) finds that intelligent technologies are reshaping both the internal and external forms of teacher authority. If educators rely uncritically on AI, this could foster technological fetishism and further weaken the teacher’s agency and professional autonomy.

4.4 Theoretical foundations of cross domain conflict

According to Шихирев (1985), the classical concept of role comprises three layers: (a) a role is a system of expectations regarding individual behavior that exists within society; (b) a role also refers to the set of expectations held by individuals occupying a given social position toward themselves; and (c) a role is manifested through the observable behaviors of individuals in that position. Teachers face a range of external expectations derived from education policies, school cultures, parents, and the broader public (Kelchtermans, 2009). Through processes of occupational socialization and daily interactions, teachers continuously receive and internalize these expectations, gradually forming an identity-based understanding of “how a teacher should act” (Tajeddin et al., 2023).

However, even when society transmits extensive behavioral norms and performance demands, these expectations are not automatically internalized into teachers’ identities (Karaolis and Philippou, 2019). A teacher’s core professional identity is gradually constructed through personal experience, emotional engagement, and internal values, and is often characterized by a high degree of stability and resistance to external influence (Clarke, 2009). This identity serves as a selective filter through which external expectations are interpreted and potentially accepted or rejected. In cases where teachers either do not receive certain role expectations, or choose not to identify with or internalize them, conflicts between identity and role may emerge (see Figure 4). Conceptually, this suggests that the content of social role expectations and that of teacher identity are not necessarily equivalent.

Moreover, behavioral competence serves as a condition for role enactment rather than the psychological origin of role conflict. A lack of competence may hinder effective role performance, manifesting as a constraint imposed by behavioral capacity on identity cognition. As Kelchtermans (2009) points out, teachers face a complex system of social expectations; however, the emergence of role conflict does not depend solely on whether teachers are capable of meeting these expectations, but rather on whether they perceive them as integral to their professional role (Van Lankveld et al., 2017). Conflict arises when teachers think, “Others expect me to do this, but I believe I should not,” rather than, “Others expect me to do this, but I cannot.”

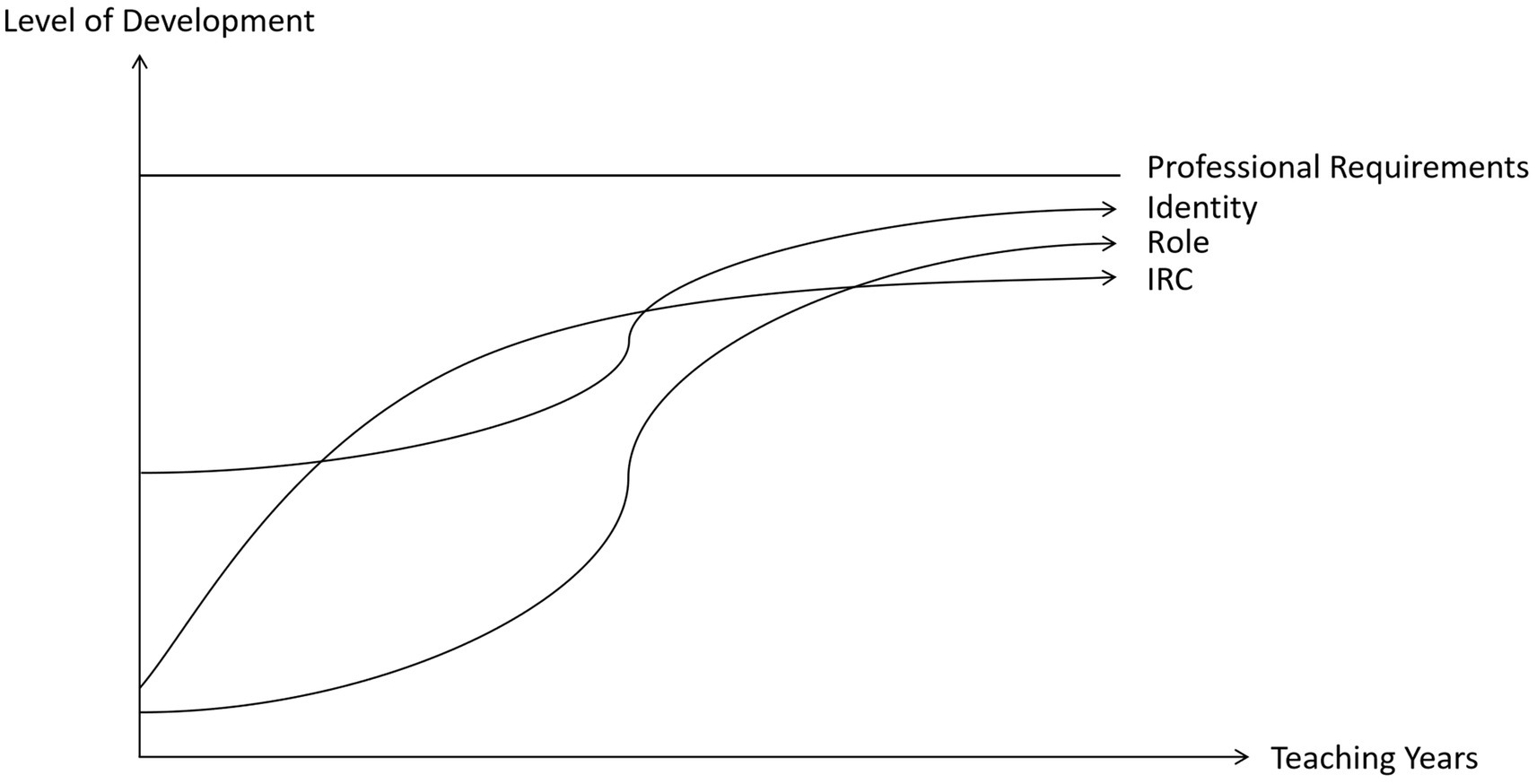

4.5 The identity-role consistency

Both theoretical and practical perspectives suggest that a high level of consistency between a teacher’s identity and professional role, referred to as Identity-Role Consistency (IRC), plays a beneficial role in fostering the development and growth of professional competence. The process of a teacher’s professional development can similarly be viewed as a gradual increase in IRC, aligning more closely with the demands of the profession. A model of this developmental process is illustrated in Figure 5. In this model, objective role expectations refer to relatively stable professional demands, while teacher identity functions as a filter that shapes the development and content of subjective role expectations. The term “role” here specifically emphasizes the teacher’s ability to perform instructional behaviors. Accordingly, the consistency between identity and role in this context refers to the alignment among societal expectations, subjective cognition, and behavioral capacity. According to the Value-Action Gap perspective, the discrepancy between societal expectations and subjective cognition is often smaller than the gap between subjective cognition and behavioral capacity within this structure (Chaplin and Wyton, 2014).

As shown in the figure, for teachers who have just completed their pre-service training, the development of professional identity typically progresses more rapidly than the development of professional role performance. This discrepancy is largely due to novice teachers’ lack of full time teaching experience. Their understanding of what it means to be a teacher often remains at the level formed during pre-service education, while their ability to enact the teacher role is insufficient to support this identity due to limited practical experience (Chen, 2003). As a result, they often find a significant gap between the realities of classroom teaching and their prior expectations. Subsequently, teachers’ practical competencies tend to develop at a faster pace than identity formation, especially during the early stages of professional development (Kagan, 1992; Fuller and Bown, 1975). This leads to a gradual narrowing of the cognitive gap between identity and role, thereby promoting an increase in IRC and aligning more closely with their personal ideal of what a teacher should be. Teachers with high levels of IRC are thus better equipped to manage the dissonance between their beliefs and behaviors. Moreover, a teacher’s ability to perform their professional role is generally not greater than their capacity for identity cognition. If a teacher has not yet developed a clear professional identity, their behavioral patterns tend to be unstable or yield limited effectiveness (Beijaard et al., 2004). In summary, the developmental trajectories of vocation, identity, and role together form a structurally layered model for the development of IRC.

5 Self authenticity

In traditional psychology, there is a concept known as self-authenticity, which is highly related in its underlying meaning to the IRC proposed in this study. A joint analysis of self authenticity and IRC can enhance the practical relevance of IRC and help establish it as a distinct and independent conceptual construct.

5.1 The connotation of self authenticity

Self authenticity is an important concept that emphasizes the alignment of an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors with their true self. It is generally understood as comprising cognitive clarity about the self, emotional acceptance of genuine feelings, and behavioral expression that remains faithful to one’s internal values and beliefs (Li et al., 2025). The philosophical roots of self authenticity can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophy, particularly Socrates’ proposition to “know thyself.” In modern intellectual history, existentialist philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre further developed the idea of authentic existence and examined how individuals often flee from their true selves. However, the concept of self authenticity as a systematic psychological term emerged in the 20th century with the rise of humanistic psychology. In his 1961 work On Becoming a Person, Carl Rogers was the first to articulate the psychological importance of the real self in a comprehensive manner. He argued that a fully functioning person must be grounded in honest awareness of, and free expression of, inner emotions (Rogers, 1995).

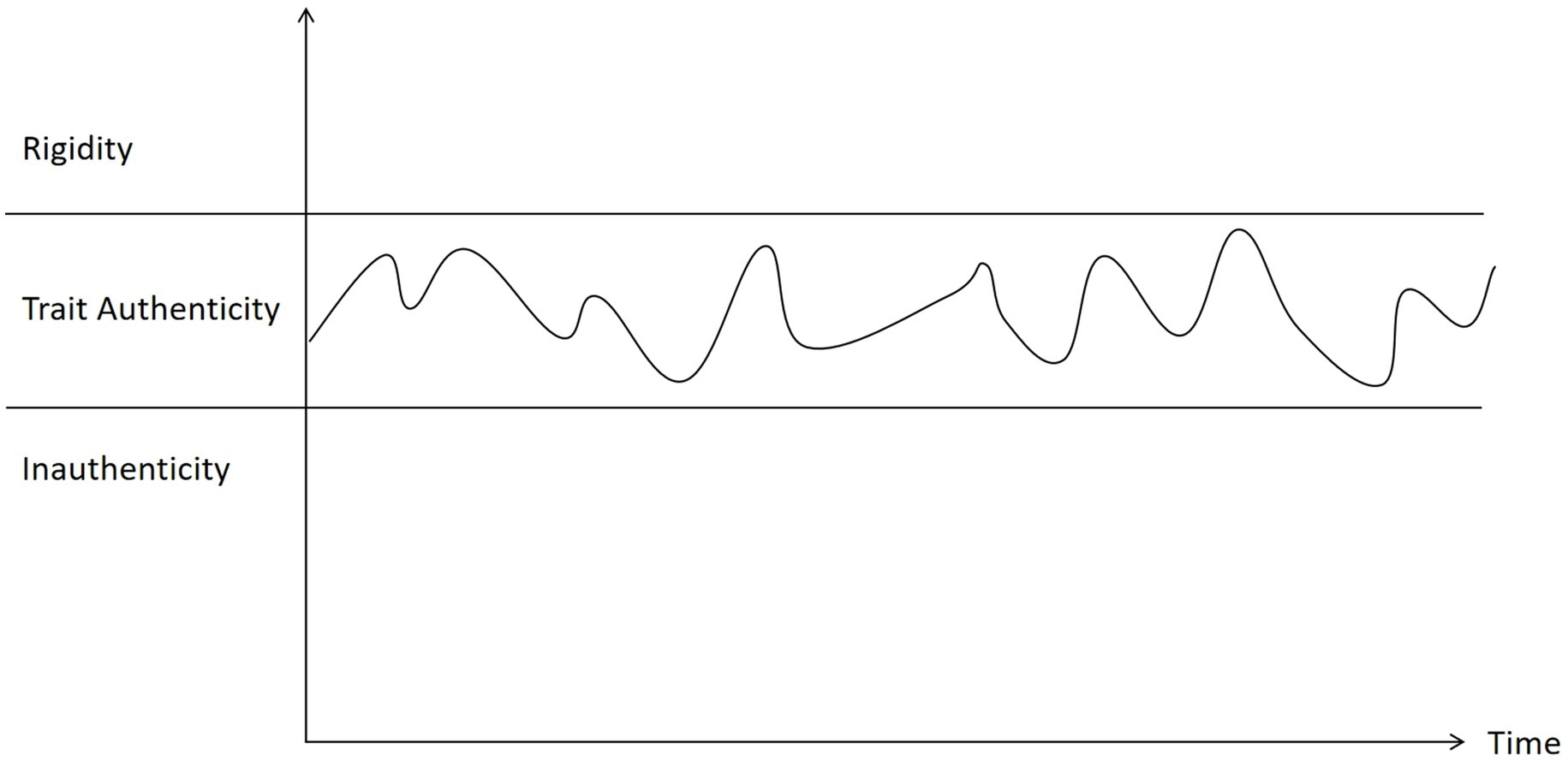

In more contemporary psychological research, Kernis and Goldman (2006) provided a structured definition of the concept of authenticity by distinguishing between two levels: a relatively enduring, personality-level trait authenticity, and a more transient, unstable state authenticity. They proposed that authenticity comprises four interrelated dimensions: (a) self-understanding, referring to a clear awareness of one’s values, emotions, and motivations; (b) openness, the ability to objectively recognize one’s strengths and weaknesses; (c) behavior congruence, which describes the alignment between one’s actions and inner beliefs; (d) relational orientation, the tendency to remain genuine in social interactions without pretension or excessive people-pleasing. Within this model, state authenticity is conceptualized as the immediate psychological experience of being oneself, serving as the core of the subjective sense of internal consistency (Sedikides et al., 2017; Lenton et al., 2013), this experience has been found to exhibit marked cultural variations (Slabu et al., 2014).

5.2 IRC and self-authenticity

From the perspective of Identity-Role Consistency (IRC), the extent to which individuals can express their authentic selves depends on the intensity of conflict between their professional identity and personal roles. In other words, the greater the perceived tension between social expectations tied to a particular professional role and an individual’s self-identification, the more constrained the space becomes for authentic self-expression. Within this framework, individuals must often negotiate, compromise, or conceal aspects of the self across multiple roles to accommodate external structural demands. Authenticity, therefore, is no longer merely an internal psychological experience but becomes a product of social regulation (Roberts et al., 2009). Despite the apparent similarities between IRC and authenticity in their attention to tensions between the self and identity, the two concepts are grounded in fundamentally different theoretical and disciplinary foundations. Authenticity, as a psychological construct, centers on the individual’s perception, acceptance, and expression of the self, emphasizing inner coherence and value integration (Guenther et al., 2024; Hart et al., 2024). In this sense, authenticity is a subjective experiential state, an individual’s ability to maintain self-directedness and inner truth in the face of external pressures (Kernis and Goldman, 2006). By contrast, IRC is more firmly rooted in sociological traditions, with its theoretical foundation emphasizing the structural and normative dimensions of role behavior. Individual behavior is understood within the framework of social interactions and institutional constraints. Role identity conflict is interpreted as a manifestation of structural tension, reflecting how individuals adapt to and struggle with societal expectations. As such, research on IRC tends to focus on how external social structures shape behavioral boundaries, regulate modes of expression, and influence identity performance.

This divergence between psychological and sociological perspectives also leads to different developmental trajectories for the two constructs. The development of authenticity typically follows a non-linear but relatively stable oscillating curve (see Figure 6), in which individuals engage in processes of self-reflection, reconstruction, and affirmation across different life stages and contexts, ultimately approaching a state of trait authenticity, a stable balance between rigidity and inauthenticity (Wang Y. et al., 2024). This process highlights the dynamic alignment between self and lived experience, driven internally by the pursuit of personal truth. In contrast, the development of IRC may exhibit more pronounced stage-based characteristics, following a smoother upward trajectory. This development is often shaped by institutional and cultural factors, and progresses toward an idealized professional identity as defined by external standards.

Figure 6. Dynamic authenticity model, cited in Wang Y. et al. (2024).

5.3 Authenticity in conflict

Extensive research has demonstrated the close relationship between identity–role conflict and personal authenticity in professional settings (Caza et al., 2017; Van den Bosch and Taris, 2018). In the teaching profession, which is characterized by high levels of emotional labor, variations in teachers’ levels of authenticity likewise influence the ways in which they navigate and respond to conflicts in instructional practice. Experienced teachers who are able to express their authentic selves are more likely to build deeper and more meaningful connections with their students (Duignan and McGrath, 2022). However, a considerable number of teachers find their ability to display authenticity significantly constrained by factors such as limited professional experience and administrative pressures. Consequently, within the tensions between teacher identity and institutional role expectations, authenticity may serve as a critical dynamic regulatory mechanism (see Figure 7).

When confronted with conflict, teacher authenticity often manifests in two polarized forms. The first is a rigid adherence to one’s identity, insisting on a fixed notion of the ideal teacher and resisting adaptation. The second is a performative compliance with externally imposed role expectations, overreliance on pedagogical norms, standardized procedures, and managerial performativity to construct a socially acceptable professional image (Kernis and Goldman, 2006). The former leans toward the identity pole of authenticity, while the latter aligns with the role pole. It is important to acknowledge that, as socially embedded professionals, teachers are inevitably subject to normative constraints and institutional expectations; absolute authenticity is therefore practically unattainable. As Sedikides and Schlegel (2024) argue, authenticity does not imply the unrestrained expression of one’s internal thoughts and feelings, but rather entails a sustainable balance between external demands and internal coherence. In this light, an idealized form of authenticity should be understood as a form of critical authenticity, a reflexive and adaptive process of identity construction that upholds professional ethics and legal norms while preserving the individual’s sense of uniqueness and integrity (Jongman-Sereno and Leary, 2019).

6 Conclusion

This paper provides a systematic analysis of the concept of “teacher” through the dimensions of profession, role, and identity, and theoretically highlights the importance of Identity-Role Consistency (IRC) as a key internal coordination mechanism in professional development. We argue that the misalignment and conflict between a teacher’s identity (“who I am”) and role (“what I am expected to do”) not only compromise the effectiveness of instructional practices but also directly affect job satisfaction, psychological well being, and long-term developmental potential. Based on this structural analysis, the study proposes an integrated approach to examining identity and role while introducing the perspective of cross-pressure, which helps uncover the complex psychological dynamics and behavioral adaptations involved in the process of teacher development. Focusing on IRC and incorporating the psychological concept of self authenticity, this study constructs an interpretive framework that connects social structures with individual internal experiences. It emphasizes that, in the context of role conflict, the pursuit of critical authenticity provides a more sustainable path for professional growth than rigid conformity or passive compliance. Consequently, enhancing teachers’ professional development requires active support for achieving higher levels of IRC.

Although this study identifies the presence and significance of IRC from both theoretical and practical perspectives, it has not yet conducted a detailed empirical investigation. Existing measurement instruments for teacher identity and role are relatively well developed (Schwab et al., 1983; Beijaard et al., 2000), and future research may build upon and refine these tools to quantify standard levels of IRC as indicators of teachers’ psychological health and related outcomes. Furthermore, the dimensional structure of IRC remains underdeveloped and does not fully account for all types of identity-role conflicts experienced by teachers. Qualitative studies exploring these dimensions would therefore offer valuable contributions to this line of inquiry. We believe that teacher learning and development driven solely by external rewards or institutional mandates, without considering how individual teachers perceive the role expectations of the profession, may yield noticeable short-term results, but these results will be built upon the pain and struggle of the teachers.

Author contributions

HL: Resources, Supervision, Software, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Validation, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1650873/full#supplementary-material

References

Akkerman, S. F., and Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 308–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.013

Archana, S., and Rani, K. U. (2017). Role of a teacher in English language teaching (ELT). Int. J. Educ. Sci. Res. 7, 1–4.

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. J. Educ. Policy 18, 215–228. doi: 10.1080/0268093022000043065

Batista, P., Mouraz, A., Viana, I., and Graça, A. (2024). Intergenerational learning among teachers’ professional development and lifelong learning: an integrative review of primary research. Europ. J. Educ. Res. 2024, 1275–1290. doi: 10.12973/eu-jer.13.3.1275

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., and Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 107–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

Beijaard, D., Verloop, N., and Vermunt, J. D. (2000). Teachers’ perceptions of professional identity: an exploratory study from a personal knowledge perspective. Teach. Teach. Educ. 16, 749–764. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00023-8

Biesta, G. J. (2015). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. New York: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (2018). “The forms of capital” in The sociology of economic life. (ed.) M. Granovetter (New York: Routledge), 78–92.

Brenner, P. S., Serpe, R. T., and Stryker, S. (2014). The causal ordering of prominence and salience in identity theory: an empirical examination. Soc. Psychol. Q. 77, 231–252. doi: 10.1177/0190272513518337

Burke, P. J., and Tully, J. C. (1977). The measurement of role identity. Soc. Forces 55, 881–897. doi: 10.2307/2577560

Caza, B. B., Moss, S., and Vough, H. (2017). From synchronizing to harmonizing: the process of authenticating multiple work identities. Admin. Sci. Q. 63, 703–745. doi: 10.1177/0001839217733972

Chaplin, G., and Wyton, P. (2014). Student engagement with sustainability: understanding the value–action gap. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 15, 404–417. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-04-2012-0029

Clarke, D. M. (1997). The changing role of the mathematics teacher. J. Res. Math. Educ. 28, 278–308. doi: 10.2307/749782

Clarke, M. (2009). The ethico-politics of teacher identity. Educ. Philos. Theory 41, 185–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00420.x

Clarke, M. (2023). The subordination of teacher identity: ethical risks and potential lines of flight. Teach. Teach. 29, 241–258. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2022.2144823

Coldron, J., and Smith, R. (1999). Active location in teachers’ construction of their professional identities. J. Curric. Stud. 31, 711–726. doi: 10.1080/002202799182954

Coverman, S. (1989). Role overload, role conflict, and stress: addressing consequences of multiple role demands. Soc. Forces 67, 965–982. doi: 10.2307/2579710

Crenshaw, K. (2022). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics [1989]. Contemp. Sociol. Theory 1:354.

Day, C., Stobart, G., Sammons, P., and Kington, A. (2006). Variations in the work and lives of teachers: relative and relational effectiveness. Teach. Teach. 12, 169–192. doi: 10.1080/13450600500467381

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 19, 109–134. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Do, Q., and Hoang, H. T. (2024). The construction of language teacher identity among graduates from non-English language teaching majors in Vietnam. Engl. Teach. Learn. 48, 485–502. doi: 10.1007/s42321-023-00142-z

Duignan, C., and McGrath, D. (2022). Authenticity in teaching and learning: how far do we need to go? All Ireland J. High. Educ. 14:661. doi: 10.62707/aishej.v14i1.661

Elbaz, F. (1981). The teacher’s “practical knowledge”: report of a case study. Curr. Inq. 11, 43–71. doi: 10.1080/03626784.1981.11075237

Fan, S., Wang, T., and Zhou, J. (2023). Identity conflicts and coping strategies of newly appointed kindergarten teachers with postgraduate degrees. Early Childhood Educ. Res. 1, 72–82. doi: 10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2023.01.005

Fuller, F. F., and Bown, O. H. (1975). Becoming a teacher. Teachers Coll. Rec. 76, 25–52. doi: 10.1177/016146817507600603

Gao, R. (2025). The Erosion and reconstruction of teachers’ authority in the context of artificial intelligence. J. Theory Pract. Educ. Innov. 2, 26–33.

Gao, Y., and Cui, Y. (2024). English as a foreign language teachers’ pedagogical beliefs about teacher roles and their agentic actions amid and after COVID-19: a case study. Relc J. 55, 111–127. doi: 10.1177/00336882221074110

Garner, J. K., and Kaplan, A. (2019). A complex dynamic systems perspective on teacher learning and identity formation: an instrumental case. Teach. Teach. 25, 7–33. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1533811

Ghiasvand, F., Kogani, M., and Nemati, F. (2023). “Teachers as conflict managers”: mapping novice and experienced Iranian EFL teachers’ professional identity conflicts and confrontation strategies. Asian Pac. J. Sec. Foreign Lang. Educ. 8:45. doi: 10.1186/s40862-023-00219-z

Goffman, E. (2023). “The presentation of self in everyday life” in Social theory re-wired. eds. W. Longhofer and D. Winchester (New York: Routledge), 450–459.

González-Calvo, G. (2025). Teacher identity and neoliberalism: an auto-Netnographic exploration of the public education crisis. Eur. J. Educ. 60:910. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12910

Guenther, C. L., Zhang, Y., and Sedikides, C. (2024). The authentic self is the self-enhancing self: A self-enhancement framework of authenticity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 50, 1182–1196. doi: 10.1177/01461672231160653

Guo, L. (2022). Internal coordination and external balance: optimization path for the income distribution of university teachers. Chongqing High. Educ. Res. 10, 51–61. doi: 10.15998/j.cnki.issn1673-8012.2022.03.005

Hart, W., Garrison, K., Lambert, J. T., and Hall, B. T. (2024). Don’t worry about being you: relations between perceived authenticity and mental health are due to self-esteem and executive functioning. Psychol. Rep. :00332941241267712. doi: 10.1177/00332941241267712

Hedrick-Shaw, D. (2024). Looking back to move forward: re-examining “alternative” certification as a site for teacher learning. Teach. Teach. 31, 678–690. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2024.2397584

Herman, J. B., and Gyllstrom, K. K. (1977). Working men and women: inter-and intra-role conflict∗. Psychol. Women Q. 1, 319–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1977.tb00558.x

Holt-Reynolds, D. (2000). What does the teacher do?: constructivist pedagogies and prospective teachers’ beliefs about the role of a teacher. Teach. Teach. Educ. 16, 21–32. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00032-3

Homayed, A., Karkoulian, S., and Srour, F. J. (2025). Wait! What’s my job? Role ambiguity and role conflict as predictors of commitment among faculty. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 17, 706–718. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-11-2023-0549

Hu, W., and Shi, Y. B. (2018). Research on the role predicament of teachers in the era of artificial intelligence. US China Educ. Rev. 8, 273–278. doi: 10.17265/2161-6248/2018.06.004

Iannucci, C., MacPhail, A., and Richards, R. (2019). Development and initial validation of the teaching multiple school subjects role conflict scale (TMSS-RCS). Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 25, 1017–1035. doi: 10.1177/1356336X18791194

Jan, H. (2017). Teacher of 21st century: characteristics and development. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 7, 50–54.

Jiang, S. (2025). An analysis of the construction of professional standards for the evaluative literacy of U.S. pre-service teachers: from the perspective of external quality assurance. J. Teach. Educ. 12, 95–108. doi: 10.13718/j.cnki.jsjy.2025.03.011

Jongman-Sereno, K. P., and Leary, M. R. (2019). The enigma of being yourself: a critical examination of the concept of authenticity. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 23, 133–142. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000157

Kaasila, R., Lutovac, S., Komulainen, J., and Maikkola, M. (2021). From fragmented toward relational academic teacher identity: the role of research-teaching nexus. High. Educ. 82, 583–598. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00670-8

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 129–169. doi: 10.3102/00346543062002129

Kanno, Y., and Kangas, S. E. (2024). English learner as an intersectional identity. J. Lang. Identity Educ. 23, 320–326. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2023.2275280

Karaolis, A., and Philippou, G. N. (2019). “Teachers’ professional identity” in Affect and mathematics education: Fresh perspectives on motivation, engagement, and identity eds. M. S. Hannula, G. Leder, F. Morselli, M. Vollstedt, and Q. Zhang. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. 397–417.

Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who i am in how i teach is the message: self-understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teach. Teach. 15, 257–272. doi: 10.1080/13540600902875332

Kernis, M. H., and Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: theory and research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 38, 283–357.

Khanal, J., and Ghimire, S. (2024). Understanding role conflict and role ambiguity of school principals in Nepal. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 52, 359–377. doi: 10.1177/17411432211073410

Kulgemeyer, C., and Riese, J. (2018). From professional knowledge to professional performance: the impact of CK and PCK on teaching quality in explaining situations. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 55, 1393–1418. doi: 10.1002/tea.21457

Le, X. (2024). The impact of after-hours connectivity behavior on kindergarten teachers’ work stress: the mediating role of work-life conflict and the moderating role of employment status. J. Shaanxi Xueqian Normal Univ. 40, 61–68.

Lenton, A. P., Bruder, M., Slabu, L., and Sedikides, C. (2013). How does “being real” feel? The experience of state authenticity. J. Pers. 81, 276–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00805.x

Levin, J. S., and Liu, J. (2018). Conflicts and adaptations of tenured faculty’s academic identity in American higher education under neoliberalism: an interview with professor John S. Levin. J. Soochow Univ. 6, 101–109. doi: 10.19563/j.cnki.sdjk.2018.03.011

Li, Y., Li, Y., and Castaño, G. (2020). The impact of teaching-research conflict on job burnout among university teachers: an integrated model. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 31, 76–90.

Li, Q., Liu, M., Zhou, Z., and Hong, W. (2025). Longitudinal associations of self-control with subjective well-being and psychological well-being: the mediating roles of basic psychological need satisfaction and self-authenticity. Int. J. Behav. Dev. :01650254241306123. doi: 10.1177/01650254241306123

Lipsky, E., Friedman, I. D., and Harkema, R. (2017). Am i wearing the right hat? Navigating professional relationships between parent-teachers and their colleagues. Sch. Community J. 27, 257–282.

Liu, H., Sammons, P., and Menter, I. (2025). Exploring teacher identity tensions and coping strategies in a comparative case study of primary school teachers’ narratives. Teach. Teach. 31, 419–452. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2023.2288627

Macfarlane, B. (2016). From identity to identities: A story of fragmentation. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 35, 1083–1085. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1222648

Mead, S. (2012). Recent State Action on Teacher Effectiveness: What’s in State Laws and Regulations? Washington, DC: Bellwether Education Partners.

Merton, R. K. (1957). The role-set: problems in sociological theory. Br. J. Sociol. 8, 106–120. doi: 10.2307/587363

Miller, M. K., Clark, J. D., and Jehle, A. (2015). Cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger). Blackwell Encycl. Sociol. 1, 543–549. doi: 10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosc058.pub2

Moore, R. L. (1992). Stories of teacher identity: An analysis of conflict between social and personal identity in life stories of women teachers in Maryland, 1927–1967. College Park: University of Maryland.

Mudhar, G., Ertesvåg, S. K., and Pakarinen, E. (2024). Patterns of teachers’ self-efficacy and attitudes toward inclusive education associated with teacher emotional support, collective teacher efficacy, and collegial collaboration. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 39, 446–462. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2233297

Naz, Z., and Beighton, C. (2024). Dis/placing teacher identity: performing the ‘brutal forms of formalities’ in English further education. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 43, 553–567. doi: 10.1080/02601370.2024.2368720

Raman, Y., and Yiğitoğlu, N. (2018). Justifying code switching through the lens of teacher identities: novice EFL teachers’ perceptions. Qual. Quant. 52, 2079–2092. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0617-1

Ren, B., and Pan, X. (2025). Understanding EFL teacher identity and identity tensions in a Chinese university context. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 35, 363–379. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12622

Roberts, L. M., Cha, S. E., Hewlin, P. F., and Settles, I. H. (2009). “Bringing the inside out: enhancing authenticity and positive identity in organizations” in Exploring positive identities and organizations eds. L. M. Roberts and J. E. Dutton (New York: Psychology Press), 149–169.

Rogers, C. R. (1995). On becoming a person: a therapist’s view of psychotherapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Sachs, J. (2001). Teacher professional identity: competing discourses, competing outcomes. J. Educ. Policy 16, 149–161. doi: 10.1080/02680930116819

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schwab, R. L., Iwanicki, E. F., and Pierson, D. A. (1983). Assessing role conflict and role ambiguity: a cross validation study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 43, 587–593. doi: 10.1177/001316448304300231

Sedikides, C., and Schlegel, R. J. (2024). Distilling the concept of authenticity. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 3, 509–523. doi: 10.1038/s44159-024-00323-y

Sedikides, C., Slabu, L., Lenton, A., and Thomaes, S. (2017). State authenticity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 521–525. doi: 10.1177/0963721417713296

Seifert, S., and Cucchiara, M. B. (2024). “I feel like a hypocrite”: school choice and teacher role identity. Urban Rev. 56, 259–284. doi: 10.1007/s11256-023-00668-3

Selwyn, N. (2021a). Education and technology: Key issues and debates. London, New York, Dublin: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Selwyn, N. (2021b). The human labour of school data: exploring the production of digital data in schools. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 47, 353–368. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2020.1835628

Seyri, H., and Nazari, M. (2023). From practicum to the second year of teaching: examining novice teacher identity reconstruction. Camb. J. Educ. 53, 43–62. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2022.2069227

Shukla, A., and Srivastava, R. (2016). Development of short questionnaire to measure an extended set of role expectation conflict, coworker support and work-life balance: the new job stress scale. Cogent Bus Manag 3:1. doi: 10.1080/23311975.2015.1134034

Slabu, L., Lenton, A. P., Sedikides, C., and Bruder, M. (2014). Trait and state authenticity across cultures. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 45, 1347–1373. doi: 10.1177/0022022114543520

Steinberger, P., and Magen-Nagar, N. (2017). What concerns school teachers today? Identity conflict centrality scale for measuring teacher identity: a validation study. Teach. Educ. Q. 44, 35–57.

Stryker, S. (2001). “Traditional symbolic interactionism, role theory, and structural symbolic interactionism: the road to identity theory” in Handbook of sociological theory (Boston, MA: Springer US), 211–231.

Stryker, S., and Serpe, R. T. (1994). Identity salience and psychological centrality: equivalent, overlapping, or complementary concepts? Soc. Psychol. Q. 57, 16–35. doi: 10.2307/2786972

Sun, M., Candelaria, C. A., Knight, D., LeClair, Z., Kabourek, S. E., and Chang, K. (2024). The effects and local implementation of school finance reforms on teacher salary, hiring, and turnover. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 47:01623737231213880. doi: 10.3102/01623737231213880

Tajeddin, Z., Alemi, M., and Maleknia, Z. (2023). Torn between socio-political mandates and professional identity: teachers’ collaborative reflection on their identity tensions. Lang. Teach. Res. :13621688231213602. doi: 10.1177/13621688231213602

Tajeddin, Z., and Nazari, M. (2025). “Language teacher identity: A systematic review” in Handbook of Language Teacher Educations. (eds.) Z. Tajeddin and T. S. C. Farrell. Cham: Critical Review and Research Synthesi. 1–18.

Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., and Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ. Ident. 56, 9780203505984–9780203505916.

Tezgiden Cakcak, S. Y. (2016). A critical review of teacher education models. Int. J. Educ. Policies 2016, 121–140.

Tsui, A. B. (2007). Complexities of identity formation: A narrative inquiry of an EFL teacher. TESOL Q. 41, 657–680. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00098.x

Tugwell, P., and Tovey, D. (2021). PRISMA 2020. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 134, A5–A6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.04.008

Umpstead, R., Brady, K., Lugg, E., and Klinker, J. (2013). Educator ethics: A comparison of teacher professional responsibility laws in four states. JL Educ. 42:183.

Van den Bosch, R., and Taris, T. (2018). Authenticity at work: its relations with worker motivation and well-being. Front. Commun. 3:21. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00021

Van Lankveld, T., Schoonenboom, J., Kusurkar, R. A., Volman, M., Beishuizen, J., and Croiset, G. (2017). Integrating the teaching role into one’s identity: a qualitative study of beginning undergraduate medical teachers. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 22, 601–622. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9694-5

Wake, J. D., Dysthe, O., and Mjelstad, S. (2007). New and changing teacher roles in higher education in a digital age. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 10, 40–51.

Wang, Y., Li, Y., Zheng, O., and Ge, S. (2024). Unity of person and environment: a proposal for the dynamic authenticity model. Psychol. Technol. Applic. 6, 374–384. doi: 10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2024.06.006

Wang, K., Yuan, R., and Lee, I. (2024). Exploring contradiction-driven language teacher identity transformation during curriculum reforms: a Chinese tale. TESOL Q. 58, 1548–1579. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3294

Weng, Z., Troyan, F. J., Fernández, L., and McGuire, M. (2024). Examining language teacher identity and intersectionality across instructional contexts through the experience of perezhivanie. TESOL Q. 58, 567–599. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3237

Wenger, E. (1999). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Yang, L. (2025). Reflection and optimization: a study on the evaluation dimensions of professional title assessment criteria for vocational college teachers—an analysis based on the policy of professional title assessment criteria in vocational colleges in province G. Modern Voc. Educ., 117–120.

Yang, S., Shu, D., and Yin, H. (2022). “Teaching, my passion; publishing, my pain”: unpacking academics’ professional identity tensions through the lens of emotional resilience. High. Educ. 84, 235–254. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00765-w

Yu, H. (2024). The application and challenges of ChatGPT in educational transformation: new demands for teachers’ roles. Heliyon 10:e24289. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24289

Zhang, Y. (2022). Analysis of contradictions and conflicts in the transformation of teachers’ identity in the context of online education. Contin. Educ. Res. 6, 29–33.

Zhang, X. (2025). Leave or stay? A narrative inquiry of tensions in novice English teachers’ professional identity construction at China’s private universities. Front. Psychol. 16:1485747. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1485747

Zhao, W., Liao, X., Li, Q., Jiang, W., and Ding, W. (2022). The relationship between teacher job stress and burnout: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 12:784243. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.784243

Keywords: identity conflicts, role conflicts, authenticity, teacher, behavior

Citation: Li H (2025) What kind of teacher should we become: identity–role consistency and authenticity. Front. Educ. 10:1650873. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1650873

Edited by:

Manpreet Kaur Bagga, Partap College of Education, IndiaReviewed by:

Irena Kuzborska, Centre for Immunology and Infection at the University of York, United KingdomCarla Meneses, Ramon Llull University, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanqiang Li, ZWR1bGlocUAxNjMuY29t

Hanqiang Li

Hanqiang Li