- Primary School Teacher Education, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Santu Paulus Ruteng, Ruteng, Indonesia

Social Science learning in elementary school plays a strategic role in developing social-emotional skills in students, but the orientation remains more normative in nature rather than contextual. This study attempts to examine how the employment of local culture in social studies learning can assist in developing social emotional learning (SEL). This qualitative case study design involved six teachers from six elementary schools who were chosen according to criteria of more than 10 years of experience, driving teacher status, and schools with a minimum B accreditation. Data collection techniques were carried out through observation, in-depth interviews, and document study (lesson plans and syllabus), and then analyzed using a thematic analysis approach based on the four principles of SEL, with validation through data source triangulation. The findings indicate that local culture has fostered the development of social awareness, self-management, social relations, and responsible decision-making in a constructive manner, but the component of self-awareness is not yet optimally supported in the learning process. This research adds value to the formulation of a social studies learning model founded upon local culture, not merely being cultural in nature, but also in supporting the development of students' character in a comprehensive manner through the development of social-emotional dimensions.

Introduction

Social-emotional learning (SEL) has emerged as a crucial component of education in the twenty first-century, particularly at the elementary school level where children begin to establish the foundations of their personal and social development. SEL encompasses the ability to recognize and manage emotions (Neth et al., 2020), demonstrate empathy, build positive relationships, make responsible decisions, and cope with challenges—skills that are essential not only for academic success but also for lifelong wellbeing (Lawson et al., 2019). In the context of elementary education, embedding SEL into daily learning experiences is vital, as it shapes how young learners interact with peers, respond to their environment, and develop resilience in facing future challenges. Social-emotional learning (SEL) is commonly defined as the process through which individuals acquire and apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible decisions (Şeker, 2024; Weissberg and Cascarino, 2013).

SEL is often described in five core aspects: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (Carroll et al., 2020; Neth et al., 2020; Williamson, 2017; Shapira and Amzalag, 2025). These aspects work together to nurture holistic growth, enabling students not only to perform well academically but also to thrive socially and emotionally. The benefits of SEL are wide-ranging, including improved classroom behavior, reduced emotional distress, stronger interpersonal skills, and enhanced academic achievement (Williamson, 2017). For elementary school students, SEL lays the groundwork for optimal development by fostering resilience, empathy, and character formation during their formative years. The five skills are essential for all students worldwide as they directly contribute to mental health, academic success, and life readiness in modern society (Gimbert et al., 2023; Jones et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2024; Weissberg, 2019). The integration of SEL into the curriculum not only supports cognitive development but also builds character, emotional resilience, and social competence, which are indispensable for students' holistic development.

Given its central role in shaping students' character and overall wellbeing, social-emotional learning (SEL) increasingly occupies an important position in national education curricula worldwide. Many education systems have recognized that academic achievement alone is not sufficient; students also need strong social and emotional competencies to navigate the complexities of modern life (Pahor and Nicholls, 2025). For this reason, SEL has been embedded into curriculum frameworks as a cross-cutting competency, often linked to character education, citizenship, and twenty first-century skills. In the Indonesian context, the national curriculum highlights the importance of cultivating values such as cooperation, empathy, and responsibility, which are in line with the goals of SEL. This integration demonstrates that SEL is not merely an additional program but a fundamental dimension of holistic education that supports both cognitive and non-cognitive development of students.

The integration of social-emotional learning (SEL) into social studies is particularly strategic because social studies provides a natural context for students to explore values, relationships, and community life. Through discussions of history, culture, society, and citizenship, students are encouraged to reflect on perspectives beyond their own, thereby strengthening empathy and social awareness. Classroom activities such as group projects, role-playing, and dialogue around social issues also offer opportunities to practice self-management, responsible decision-making, and collaborative problem-solving. In this way, social studies not only develop students' cognitive understanding of society but also becomes a fertile ground for cultivating social and emotional competencies. However, Social Studies instruction often remains traditional, focused on theoretical, textbook-based content that lacks relevance to students' local environments (Bliuc et al., 2011). This approach prioritizes national knowledge but fails to incorporate local social realities, making it difficult for students to connect abstract concepts to their immediate surroundings (Haulle and Kabelege, 2021). As a result, students' connection to local identity is weakened, and the learning process becomes less effective. Integrating SEL into social studies therefore ensures that learning is not only about gaining knowledge but also about building character and preparing students to become responsible, empathetic members of their communities.

Integrating local cultural materials into social studies provides students with meaningful connections to their own traditions and identities, while at the same time fostering empathy, respect, and social-emotional growth. Teachers play a pivotal role in this process, as they not only deliver knowledge but also model and facilitate the social-emotional skills that enable students to thrive holistically (Darong et al., 2023; Roberts, 2014; Wade, 1993). Local cultures, which include folklore, customs, regional languages, value systems, and daily practices, are often underutilized as educational resources (Suharyanto and Wiflihani, 2024). These cultural elements embody core values such as cooperation, empathy, tolerance, and communal wisdom, which are vital for twenty first-century social-emotional learning (SEL). Integrating local culture into Social Studies not only enriches instructional content but also serves as a strategic means of developing students' emotional intelligence and character (Miqawati et al., 2024). SEL grounded in students' lived experiences fosters deeper cognitive engagement, emotional awareness, and interpersonal sensitivity.

Empirical studies support the positive impact of culture-based learning on student engagement and identity formation. Research by Darong and Menggo (2021), Anggraini et al. (2022), Fatmawaty et al. (2022), and Mutiara Ayu (2020) shows that incorporating local folklore, stories, and images into lessons improves students' empathy, social reflection, and appreciation for diversity. Promoting values such as cooperation within culturally embedded instruction increases tolerance and collaborative behavior in students' daily lives. In addition, further evidence from Aisyah and Novita (2025) and Barak and Yuan (2021) indicates that culture-based project learning enhances not only academic understanding but also social competencies, such as respect for others' perspectives. In this respect, Darong (2022) demonstrated that project-based learning, which involves observing traditional communal practices like mutual aid during rituals, strengthens students' pride in their cultural heritage and their understanding of their roles in preserving social harmony. These findings highlight the substantial implications of integrating local culture for both cognitive development and the cultivation of socio-emotional skills (Yeh et al., 2022).

Curricular integration of local culture has been identified as a key area for development (Asmayawati et al., 2024; Koro and Hagger-Vaughan, 2025). Curriculum models based on local cultural contexts better align with students' needs and experiences. This alignment improves instructional design and increases student engagement (Mutiara Ayu, 2020), as learners feel a stronger emotional and socio-cultural connection to the subject matter. Furthermore, teacher involvement in developing culturally responsive curricula enhances collaboration among educators, families, and community members (Pahor and Nicholls, 2025; Wood, 2018). This not only enriches academic content but also promotes inclusive, participatory learning environments that support holistic student development (Humphreys and Wyatt, 2014).

Despite the existing research, many studies focus primarily on cognitive outcomes or the preservation of culture, with little attention to social-emotional competencies. Key SEL skills, such as self-awareness, emotional regulation, empathy, and interpersonal communication, are fundamental to character education but remain underexplored in the context of Social Studies. This gap in educational theory and practice reveals that SEL is often relegated to counseling programs rather than being integrated into core subjects. To address this gap, a new pedagogical approach is needed—one that systematically incorporates local cultural values into Social Studies to promote character and emotional growth. Culturally grounded SEL enables students to learn not just from textbooks but also from the values embedded in their everyday social contexts. In this way, local culture becomes a tool for fostering emotional intelligence and social responsibility from an early age (White et al., 2022). Such integration transforms learning from passive knowledge acquisition into active engagement with the moral and emotional dimensions of life.

This research offers novelty by examining how local cultural materials can be integrated into social studies learning to strengthen social-emotional learning (SEL) in primary schools. While previous studies have highlighted the importance of SEL in education, limited attention has been given to the contextual role of local culture in shaping students' social-emotional competencies, particularly within the Indonesian setting. A qualitative design is employed because it allows for a deeper exploration of teachers' strategies, students' experiences, and the cultural nuances that shape the integration of SEL into classroom practice. By focusing on lived experiences and contextual realities, qualitative inquiry provides rich insights that cannot be captured through quantitative measurement alone. Therrfore, The objectives of this study are two: (1) to explore how local cultural materials are utilized in social studies learning at the primary level, and (2) to analyze how such practices contribute to strengthening social-emotional learning among students. Despite the recognition of SEL and cultural values in the national curriculum, there remains a gap in understanding how both elements intersect in everyday classroom practice. Therefore, the central problem addressed in this study is: how can local cultural materials in social studies learning be effectively integrated to strengthen social-emotional learning in primary schools?

This approach also empowers teachers to become creative and reflective practitioners who design contextually relevant and emotionally engaging learning experiences. Teachers play a central role as agents of change, shaping both affective and cognitive domains in tandem. By incorporating local culture, educators can design instruction that is pedagogically rich and socially meaningful, allowing students to connect more deeply with the content. Therefore, this study contributes both practically and theoretically to the field. Practically, it provides models and strategies for implementing culture-based Social Studies education in diverse cultural settings. Theoretically, it bridges the gap between Social Studies and SEL by demonstrating how these domains can be integrated through culturally responsive teaching. The goal is to move beyond academic achievement alone, fostering students who are intellectually competent, emotionally aware, socially responsible, and firmly rooted in their local cultural values.

Method

This study adopted a qualitative case study design to examine how local cultural integration in elementary social studies supports students' social-emotional learning (SEL). The case study method was chosen to explore real-world teaching practices within their natural context, allowing for in-depth analysis of culturally grounded pedagogy and its SEL relevance. In this study, it is particularly useful for exploring complex and context-bound phenomena, making them suitable for understanding how teachers integrate cultural elements into classroom practices. SEL involves values such as empathy, cooperation, and respect, which are closely tied to cultural norms; therefore, examining these practices through case studies allows for deeper insight into how cultural knowledge informs social and emotional competencies. To strengthen this methodological choice, it is also necessary to specify the cultural materials integrated into learning, such as folktales that highlight moral development, role-play based on local customs, or practices of gotong royong (mutual cooperation) when working collaboratively. Clarifying these elements ensures methodological rigor, demonstrates the correlation between case study and research objectives, and highlights the potential of local wisdom to enrich SEL. Subsequently, the unit of analysis in this study is the individual teacher, and by employing a multi-case study design across several elementary schools, Six elementary teachers were purposively selected based on teaching experience (minimum 10 years), formal qualifications, and employment at schools with at least “B” accreditation to ensure high pedagogical quality.

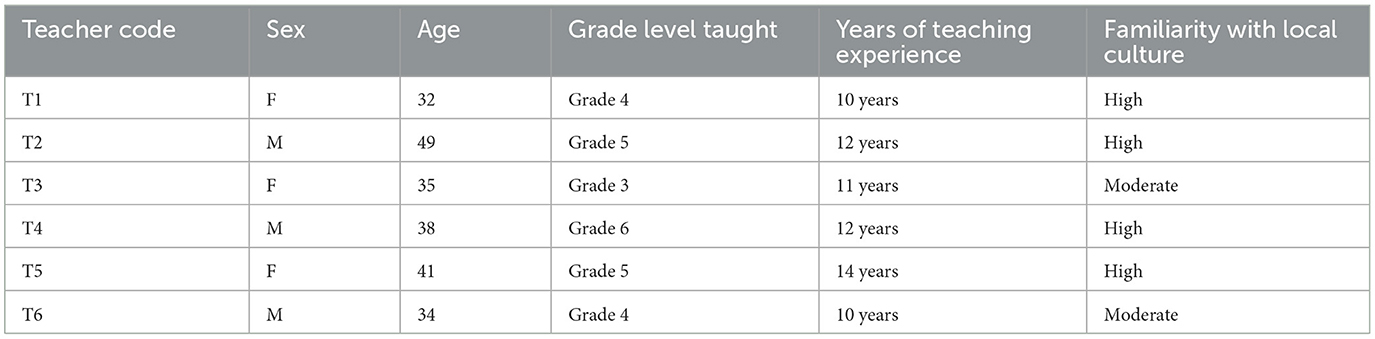

The six teachers were selected because this number is sufficient to provide rich, in-depth data across multiple cases while remaining manageable for detailed qualitative analysis. Qualitative research emphasizes depth over breadth, and a small number of participants allows the researcher to capture nuanced experiences without being overwhelmed by excessive data (Olugbenga and Ridwan, 2025) Thus, selecting six teachers ensures a balance between diversity of perspectives and feasibility of analysis, strengthening the credibility and transferability of the findings (Table 1).

Data collection involved classroom observations, semi-structured teacher interviews, and analysis of instructional documents (syllabi and lesson plans). The interview instrument takes the form of a semi-structured interview guide designed to explore teachers' perspectives on integrating local culture into Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). The guide consists of open-ended questions that allow teachers to share their experiences, strategies, and challenges in applying cultural values in classroom practice. By using this instrument, the researcher ensures that the interviews remain focused on the research objectives while providing flexibility for teachers to elaborate on their unique contexts. In addition, an observation instrument in the form of a structured checklist is employed to systematically capture classroom practices, such as how teachers integrate cultural materials, foster cooperation, and model emotional regulation during learning activities. Furthermore, a document analysis instrument is used to review lesson plans, teaching materials, and students' written work in order to identify how cultural values are formally embedded into instructional design and learning outcomes. Together, these instruments complement each other by providing self-reported insights, direct behavioral evidence, and documentary proof of how local culture is integrated into SEL instruction. Thematic analysis was employed to analyze the data, with the coding process guided by the four domains of Social and Emotional Learning (SEL): self-awareness, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. These domains served as analytical categories that allowed the researcher to systematically identify, organize, and interpret patterns across the data obtained from interviews, observations, and document analysis. The interpretation of the data involved going beyond simply categorizing responses to examining how the themes illustrated the ways teachers integrated local culture into SEL practices. This meant connecting teachers' narratives, observed behaviors, and documented materials with broader cultural contexts and educational goals. For example, when teachers incorporated local traditions of gotong royong into group tasks, the researcher interpreted this not only as a classroom strategy but also as an embodiment of cultural values that strengthen SEL competencies. Likewise, references to folktales or cultural rituals were interpreted as pedagogical tools that transmit social norms while nurturing emotional understanding. Through this interpretive process, the analysis highlighted both the explicit strategies teachers used and the implicit cultural meanings that shaped their approaches to fostering SEL. Finally, triangulation and member checking enhanced the study's validity and credibility. To ensure trustworthiness, the study employed multiple strategies: triangulation of data sources (observations, interviews, and documents) to corroborate findings; member checking, where participants reviewed summaries of their interview responses to validate accuracy; and peer debriefing with colleagues to minimize researcher bias. Detailed field notes and reflective journaling were also maintained to support transparency and rigor in the analytic process.

Results

Thematic analysis revealed that self-awareness is the least integrated SEL domain in local culture-based social studies instruction. While self-awareness—entailing emotional recognition, self-reflection, and identifying personal strengths—was absent as a clear pedagogical goal, classroom practices predominantly emphasized social values like empathy, cooperation, and responsibility. Observations showed limited activities encouraging introspection, such as emotional reflection or personal expression. Interviews confirmed that teachers often lacked conceptual clarity on embedding self-awareness within culturally responsive pedagogy, viewing social studies primarily as a platform for communal rather than intrapersonal development. Curriculum documents further reflected this gap, focusing on collective values without clear objectives targeting emotional insight or critical self-evaluation.

Case 1 (Teacher A)

Findings from Teacher A's interview show that students still rely heavily on teacher guidance in managing tasks, indicating limited development of self-management skills. In the interview, Teacher A explained, “In class, I usually give detailed instructions. Students rarely plan their own learning steps or manage their own tasks—everything is guided by me.” Observation supported this, as the teacher controlled most of the lesson flow with minimal student autonomy.

In terms of self-awareness, Teacher A acknowledged that reflection activities were lacking: “I usually focus on the value of mutual cooperation and culture, but I have never specifically invited students to reflect on their feelings or thoughts.” Teacher A frequently used local cultural practices to strengthen empathy: “We often discuss the custom of helping each other in the village, so that students learn to understand the importance of caring for each other.”

Observation showed students collaborating in group activities, such as making a map of local culture, which fostered communication and teamwork. For responsible decision-making, Teacher A encouraged contextual discussions. One activity asked students to decide appropriate actions when guests visited based on cultural traditions. Observation noted that students debated several alternatives before reaching a culturally respectful solution, showing that decision-making was guided by local values. This is supported by document analysis confirming the emphasis was placed on culture, but not explicitly on personal emotional awareness. However, social awareness and relationship skills were more prominent.

Case 2 (Teacher B)

Based on the interview, Teacher B reported rarely asking students to reflect on emotions: “Most of the time, I ask them to focus on tasks, not on how they feel about them.” Teacher B encouraged students to work together through cultural case studies, often using proverbs that highlighted caring and cooperation. During observations, students actively discussed roles in group presentations, demonstrating collaboration. In responsible decision-making, Teacher B's classroom showed similar challenges with self-management, as students depended on teacher instructions and had little room for independent planning. Observation revealed that even in group tasks, the teacher gave step-by-step instructions, limiting opportunities for autonomy. Self-awareness was also underdeveloped; Document study revealed the absence of reflection prompts in lesson plans. Nevertheless, social awareness and relational skills were clearly visible. In the lesson plan, Teacher B provided local cultural scenarios for discussion, such as customary practices in welcoming guests. Students showed engagement in debating appropriate responses, with Teacher B guiding them toward consensus.

Case 3 (Teacher C)

Interview data have shown that Teacher C demonstrated stronger integration of SEL principles compared to previous cases. While students still lacked autonomy in self-management, Teacher C occasionally encouraged them to outline their group tasks independently, although final control remained with the teacher. Self-awareness activities were still limited, as Teacher C admitted: “I haven't made it a habit to ask students to think about their strengths or emotions.”

In the meantime, observation confirmed this absence of reflection time. However, Teacher C excelled in cultivating social awareness. By connecting lessons to local customs of cooperation, students were observed showing empathy and respect for others' perspectives.

Documents study have shown that teacher C included cultural narratives that encouraged discussions of shared responsibility. Relational skills were enhanced through project-based group work, such as designing posters about local ceremonies. Students engaged in dialogue, divided tasks, and presented collaboratively. Decision-making skills were also practiced, as students discussed how to resolve disputes in cultural contexts, reflecting thoughtful application of SEL within lessons.

Case 4 (Teacher D)

Based on interview, Teacher D's classroom was highly teacher-centered in terms of self-management, with strict instructions and limited student autonomy. In this respect, students looked to the teacher for guidance at every step. Meanwhile, Self-awareness development was minimal, as Teacher D acknowledged focusing more on moral and cultural lessons rather than personal emotions.

However, observation revealed active participation and respectful dialogue among students. In responsible decision-making, Teacher D encouraged simulations based on local traditions. For instance, students role-played customary practices during community gatherings and made group decisions on appropriate behavior, applying cultural values to social scenarios.

Document analysis (lesson plans) highlighted cultural topics but omitted individual reflection activities. Nonetheless, Teacher D actively promoted social awareness and relational skills through storytelling as shown in the teaching scenarios.

Case 5 (Teacher E)

The interview results indicated that Teacher E echoed the general pattern of reliance on teacher direction, with students having limited opportunities to self-regulate learning. The teacher commented, “I prefer to give them detailed steps because if not, they get confused.” This approach restricted self-management development. Self-awareness was not a focus, as no structured activities encouraged students to recognize emotions.

Observation confirmed that tasks centered on cultural knowledge rather than reflection. On the other hand, Teacher E integrated social awareness effectively by linking cultural discussions to empathy. For example, students were asked to compare their own experiences with traditional village practices of mutual aid. Observation also showed that students related personally to these stories, deepening their understanding of empathy.

Document study revealed that relational skills were strengthened through joint presentations and discussions, while decision-making was addressed through contextual scenarios, such as discussing customary responses to visitors or disputes. Students actively debated, demonstrating critical thinking within cultural frames in teaching scenarios.

Case 6 (Teacher F)

Based on interview, Teacher F showed consistent challenges with self-management, as students followed detailed teacher instructions without independent planning. Teacher F admitted rarely focusing on emotions: “I haven't asked students to reflect on how they feel during learning; I focus more on content.” Still, social awareness and relational skills were relatively strong.

Observation confirmed the structured and teacher-led nature of activities. Self-awareness was also underdeveloped. Students were observed collaborating during group assignments on cultural mapping projects, where they shared ideas respectfully and worked cooperatively. In addition, observation revealed active debate, with the teacher guiding them to consider fairness and cultural appropriateness in their decisions.

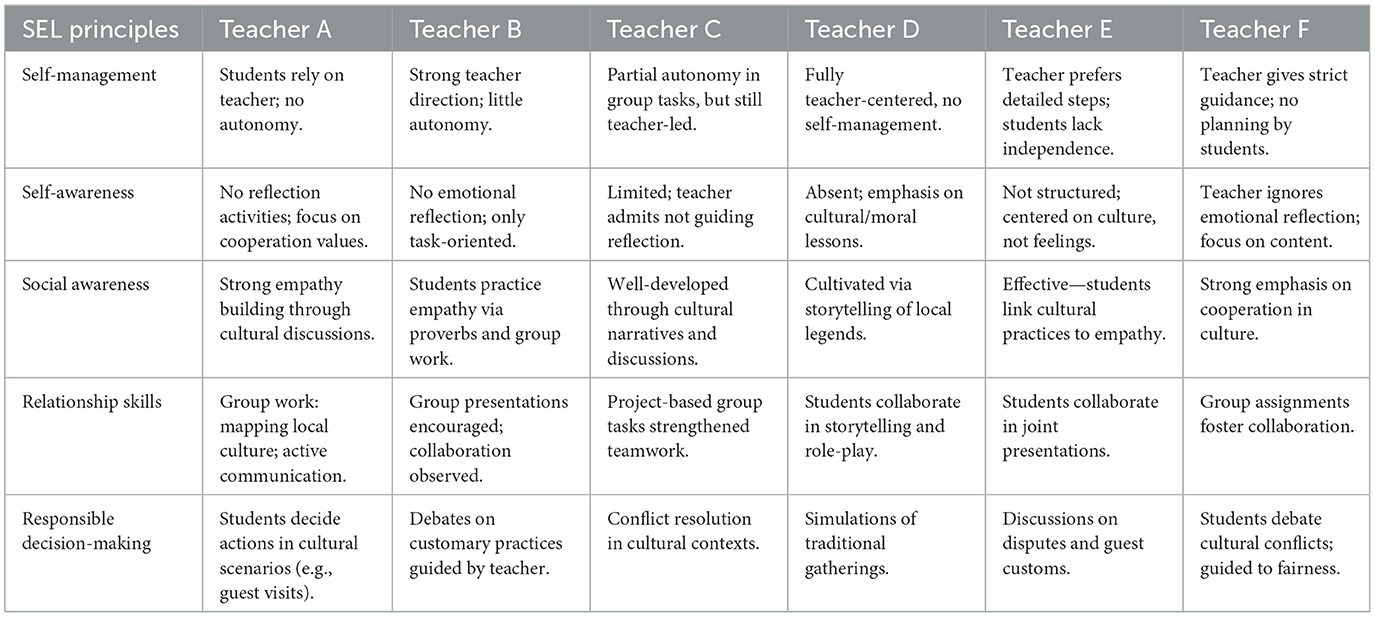

In the context of document analysis, Teacher F frequently emphasized cultural values of cooperation to build empathy. As such, responsible decision-making was fostered through cultural case discussions. In one session of the teaching scenario, students were asked how to resolve a conflict during a traditional ceremony (Table 2).

Discussion

This study explored how local culture integration within primary school social studies supports the development of students' social-emotional learning (SEL). The findings suggest that culturally contextualized learning can foster greater student empathy, social awareness, and identity formation. By embedding local values and practices into learning activities, teachers enhance both the relevance of instruction and the emotional growth of learners. This aligns with previous studies (Darong, 2022; Darong et al., 2021; Niman et al., 2020), which emphasized the positive effects of cultural context in increasing students' engagement and promoting values such as empathy and cooperation. However, the study revealed uneven implementation across the five SEL competencies. While social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making were moderately addressed, self-management and self-awareness were significantly underrepresented in classroom practice.

Self-management, which includes regulating emotions, managing stress, setting goals, and demonstrating perseverance, was notably absent from instructional strategies. This gap illustrates a disconnection between the objectives of character education and current classroom practices. Teachers often lack sufficient understanding of how to support students in this domain, which may stem from limited professional training or inadequate curriculum design that does not embed SEL strategies explicitly. To address this, pedagogical models such as project-based learning (PBL) and cooperative learning can be effectively employed (Darong, 2022). These methods require students to plan, manage their time, collaborate, and reflect on their progress—essential self-management skills. For instance, a social studies project on environmental awareness could engage students in campaign planning, fostering both collaboration and self-regulation. Regular reflections on progress and obstacles also help students develop emotional control and accountability.

The research also identified self-awareness as the least developed SEL domain. Teachers rarely facilitated activities that encouraged students to reflect on their emotions, thoughts, and personal growth. This finding aligns with Chu (2017), who argued that primary education often prioritizes collective behavior over individual introspection, especially in cultural contexts that value social harmony over personal expression. To enhance self-awareness, educators should incorporate reflective strategies, such as journaling, emotion-based storytelling, and discussion of personal experiences. These approaches allow students to connect cultural narratives with their own lives and cultivate a better understanding of their feelings and values (McCormick et al., 2015). For example, after learning about a local custom, students could be prompted to write about how they relate to it, what emotions it evokes, and whether it resonates with their own experiences. These exercises foster mindful learning (Grant et al., 2021) and provide space for developing emotional literacy. Additionally, lesson plans should include explicit learning indicators for self-awareness. Rather than stating general outcomes like “students understand the importance of cooperation,” objectives should be framed to emphasize personal reflection, such as “students can identify their role in group work and recognize how their actions affect others.” Teachers' understanding and planning must reflect a balance between cultural content and personal development to achieve comprehensive SEL integration.

Interviews indicated that while teachers acknowledged the importance of cultural values in education, they had limited recognition of self-awareness as a cultural component. Yet, fostering self-awareness is foundational to moral development and emotional growth (Darong et al., 2021; White et al., 2022). Without practices like guided reflection or personal storytelling, students lose valuable opportunities for self-exploration. Social studies, therefore, should be reconceptualized not just as instruction on social structures and norms, but also as a platform for personal development within cultural contexts. Conversely, social awareness was effectively integrated. Teachers encouraged students to participate in group activities, discuss moral values, and engage in role plays that promoted empathy and respect. These findings support White et al. (2022) and Weissberg and Cascarino (2013), who argued that contextualizing instruction through culture fosters openness and social sensitivity. Activities simulating traditional practices like mutual cooperation allowed students to experience social values firsthand, promoting deeper understanding and internalization.

The study also observed meaningful development of relationship skills, such as communication, teamwork, and conflict resolution. These skills emerged naturally during group-based tasks like cultural presentations and collaborative discussions. This aligns with Wattanawongwan et al. (2021), who found that cultural content enhances students' social competencies in context. However, while such practices are present, they are often informal and lack measurable outcomes. Teachers do not consistently include these skills as part of the planned learning objectives, leading to inconsistent implementation (De Fruyt and Scheirlinckx, 2025; Hart et al., 2020). Structured integration, including the formulation of specific learning goals related to interpersonal competence, would improve consistency and sustainability.

Responsible decision-making was moderately integrated through case studies and cultural simulations. These methods help students analyze situations and make judgments based on shared values (Miqawati et al., 2024; Nguyen and Phan, 2020). For example, cultural scenarios—such as welcoming guests or communal rituals—encourage ethical reflection and discussion. While such practices are promising, they often lean toward reinforcing normative behavior rather than encouraging critical thinking or value exploration. As Aisyah and Novita (2025) and Kim et al. (2024) suggest, true decision-making education should allow room for ethical reasoning, diverse perspectives, and consequence analysis. Teachers play a pivotal role in deepening this process by guiding reflection and ensuring that students explore not only “what” is the right choice, but “why” it is so (Ge, 2025).

Across the six cases, the findings consistently reveal that teachers have not fully supported the development of students' self-management and self-awareness. In all classrooms, students were heavily reliant on teacher direction, and structured opportunities for emotional reflection were largely absent. However, similarities also appear in the positive integration of social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making, which were strengthened through the use of local cultural practices. Teachers commonly employed group work, storytelling, and cultural scenarios to encourage empathy, cooperation, and contextual problem-solving, demonstrating that cultural values served as an effective entry point for promoting aspects of SEL.

Despite these commonalities, differences were observed in the depth and variation of SEL integration across respondents. For example, Teacher C encouraged partial autonomy in group tasks, while other teachers remained fully directive, reflecting a variation in self-management practices. Likewise, the richness of cultural narratives and decision-making scenarios differed, with some teachers (e.g., Teachers C and D) providing more complex and contextually grounded tasks than others. These differences appear to be influenced by factors such as teaching experience, the quality of the school environment, and access to resources. Teachers with longer service and those working in better-resourced schools demonstrated greater creativity in integrating cultural elements into SEL, whereas less experienced teachers tended to rely on more traditional, teacher-centered approaches.

Overall, the integration of local culture enhances SEL in social studies but is not yet optimized. Cultural content is frequently used to foster social cohesion and shared values but underutilized for cultivating personal insight and emotional understanding (Rezaei and Latifi, 2020; Wang, 2023; Ratminingsih and Budasi, 2018). The potential of local culture as a medium for holistic development is evident but requires more deliberate planning, teacher training, and curricular support (Collie, 2020). Curriculum design should move beyond general cultural appreciation to include explicit SEL indicators, particularly for self-awareness and self-management. Teacher training programs must incorporate modules on SEL strategies that align with cultural practices and develop both interpersonal and intrapersonal competencies. A holistic SEL model, grounded in local context, can support the full development of students as socially and emotionally competent individuals (Weissberg, 2019; Collie, 2020).

This study contributes to the understanding of how culturally responsive teaching can strengthen SEL in primary education. It emphasizes that local culture is not only a source of heritage but also a powerful tool for developing emotionally intelligent, socially responsible, and reflective learners. As such, theoretically, the results support the view that contextual learning using local culture is an effective tool for advancing SEL and character education, as posited by Weissberg and Cascarino (2013). Practically, this study advocates for integrating SEL objectives—especially those related to self-reflection and ethical reasoning—into the framework of culturally responsive pedagogy.

More specifically, this study contributes to the local context by highlighting the unique intersection of Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) and cultural responsiveness within the educational environment (McCallops et al., 2019). In many educational systems, SEL frameworks are often applied without considering the local cultural dynamics that influence students' emotional and social development. By focusing on the integration of culturally relevant SEL practices, this study provides valuable insights into how local cultural values, traditions, and community norms can shape SEL outcomes. Specifically, it demonstrates how educators in this local context can tailor SEL practices to better resonate with students' lived experiences, fostering stronger emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills that are grounded in their own cultural heritage. This is especially crucial in regions where cultural identity plays a central role in students' lives, as it enhances their sense of belonging and engagement in the classroom (Darong, 2022).

The findings suggest that embedding local culture into SEL practices does not just improve students' emotional and social competencies but also strengthens their connection to the learning process. In this respect, teachers can incorporate community-based storytelling, traditional conflict resolution methods, or culturally specific emotional expressions into the SEL curriculum, making it more relatable and meaningful for students. This approach can create a more inclusive and responsive educational environment that respects and affirms students' cultural identities while promoting personal growth and empathy (Heng and Yeh, 2022). Moreover, by using culturally familiar strategies, students are more likely to see the relevance of SEL to their daily lives, encouraging them to apply SEL principles both inside and outside of the classroom.

To improve SEL by embedding local culture, educators should prioritize continuous collaboration with local communities, families, and cultural leaders to identify key cultural elements that can be integrated into the curriculum. Professional development for teachers should focus on raising awareness of cultural nuances in emotional and social behaviors, helping them recognize how local customs influence students' SEL needs. Furthermore, schools could create spaces for students to engage in cultural practices that promote emotional wellbeing, such as group rituals, music, or art that reflect local traditions. By fostering an environment where students see their cultural identity reflected in their emotional development, schools can significantly enhance the effectiveness of SEL programs and contribute to the holistic development of the students, preparing them for both academic and social success in their unique cultural context.

Conclusion

The findings reveal that the integration of Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) in primary social studies through local cultural materials shows both strengths and limitations. Across all six cases, teachers demonstrated success in fostering social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making, mainly by drawing on cultural values such as cooperation, empathy, and customary rules. However, self-awareness and self-management were consistently underdeveloped, as students remained dependent on teacher direction and lacked opportunities for reflection or autonomous goal-setting.

The study is limited by its narrow sample—six teachers from specific schools—which may restrict broader applicability. Its qualitative design also limits the ability to assess the strength of links between cultural content and SEL outcomes. Additionally, the lack of student perspectives constrains understanding of SEL development. Future research should adopt broader, mixed-method approaches to evaluate the impact of cultural integration across diverse contexts. Further inquiry could explore strategies for promoting self-awareness using cultural narratives, practices, and reflection. Including student and parent voices would also provide a more complete view of how local culture supports children's holistic growth.

Author's note

Erna M. Niman is a senior lecturer at Saint Paul's Catholic University of Indonesia. She teaches in the Elementary School Teacher Education Study Program and holds a doctoral degree in Social Science. Her research interests include education, social development, and teacher training. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2218-3069. Email: ZXJuYW5pbWFuNzlAZ21haWwuY29t.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Maksimilianus Jemali/Universitas Katolik Indoensia Santu Paulus Ruteng. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aisyah, S., and Novita, D. (2025). Teachers' perception of the implementation of project-based learning in early childhood education in Indonesia: project-based learning: a perspective from Indonesian early childhood educators. Cogent Educ. 12, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2025.2458663

Anggraini, R., Derin, T., Warman, J. S., Putri, N. S., and Nursafira, M. S. (2022). Local cultures folklore grounded from english textbooks for Secondary high school Indonesia. Elsya. J. Eng. Lang. Stud. 4, 267–279. doi: 10.31849/elsya.v4i3.10582

Asmayawati Yufiarti, and Yetti, E.. (2024). Pedagogical innovation and curricular adaptation in enhancing digital literacy: a local wisdom approach for sustainable development in Indonesia context. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 10, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.joitmc.2024.100233

Barak, M., and Yuan, S. (2021). A cultural perspective to project-based learning and the cultivation of innovative thinking. Think. Skills. Creat. 39, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100766

Bliuc, A. M., Ellis, R. A., Goodyear, P., and Hendres, D. M. (2011). Understanding student learning in context: relationships between university students' social identity, approaches to learning, and academic performance. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 26, 417–433. doi: 10.1007/s10212-011-0065-6

Carroll, A., Houghton, S., Forrest, K., McCarthy, M., and Sanders-O'Connor, E. (2020). Who benefits most? Predicting the effectiveness of a social and emotional learning intervention according to children's emotional and behavioural difficulties. School Psychol. Int. 41, 197–217. doi: 10.1177/0143034319898741

Chu, Y. (2017). Twenty years of social studies textbook content analysis: still “decidedly disappointing”? Soc. Stud. 108, 229–241. doi: 10.1080/00377996.2017.1360240

Collie, R. J. (2020). The development of social and emotional competence at school: an integrated model. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 44, 76–87. doi: 10.1177/0165025419851864

Darong, H. C. (2022). Local-culture-based materials in online cooperative learning: improving reading achievement in indonesian context. J. Innov. Educ. Cult. Res. 3, 361–372. doi: 10.46843/jiecr.v3i3.113

Darong, H. C., Jem, Y. H., and Niman, E. M. (2021). Character building: the insertion of local culture values in teaching and learning. JHSS 5, 252–260. doi: 10.33751/jhss.v5i3.4001

Darong, H. C., and Menggo, S. (2021). Repositioning culture in teaching target language: local culture or target culture? Premise. J. Eng. Educ. 10:250. doi: 10.24127/pj.v10i2.4106

Darong, H. C., Niman, E. M., and Guna, S. (2023). Where am i now : symbols used in manggarai funeral rite. Indonesia 7, 150–172. doi: 10.15826/csp.2023.7.2.235

De Fruyt, F., and Scheirlinckx, J. (2025). Challenges and opportunities for the assessment of social-emotional skills. ECNU Rev. Educ. 0, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/20965311251319355

Fatmawaty, R., Faridah, F., Aquariza, N. R., and Nurahmada, A. (2022). Folklore as local culture-based material for improving students' reading comprehension of narrative text. J. ELT 9, 205–216. doi: 10.33394/jo-elt.v9i2.6338

Ge, D. (2025). Resilience and online learning emotional engagement among college students in the digital age: a perspective based on self-regulated learning theory. BMC Psychol. 13, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40359-025-02631-1

Gimbert, B. G., Miller, D., Herman, E., Breedlove, M., and Molina, C. E. (2023). Social emotional learning in schools: the importance of educator competence. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 18:194277512110149. doi: 10.1177/19427751211014920

Grant, K., Fedoruk, L., and Nowell, L. (2021). Conversations and reflections on authentic assessment. Imag. SoTL 1, 146–162. doi: 10.29173/isotl532

Hart, S. C., DiPerna, J. C., Lei, P. W., and Cheng, W. (2020). Nothing lost, something gained? Impact of a universal social-emotional learning program on future state test performance. Educ. Res. 49, 5–19. doi: 10.3102/0013189X19898721

Haulle, E., and Kabelege, E. (2021). Relevance and quality of textbooks used in primary education in tanzania: a case of social studies textbooks. Contemp. Educ. Dialogue 18, 12–28. doi: 10.1177/0973184920962702

Heng, L., and Yeh, H. C. (2022). Interweaving local cultural knowledge with global competencies in one higher education course: an internationalisation perspective. Lang. Cult. Curric. 35, 151–166. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2021.1958832

Humphreys, G., and Wyatt, M. (2014). Helping Vietnamese university learners to become more autonomous. ELT J. 68, 52–63. doi: 10.1093/elt/cct056

Jones, S. M., McGarrah, M. W., and Kahn, J. (2019). Social and emotional learning: a principled science of human development in context. Educ. Psychol. 54, 129–143. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1625776

Kim, E. K., Allen, J. P., and Jimerson, S. R. (2024). Supporting student social emotional learning and development. School Psych. Rev. 53, 201–207. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2024.2346443

Koro, R., and Hagger-Vaughan, L. (2025). Collaborative curriculum making at a local level: the Culture and Language integrated Classrooms (CLiC) project–integrating linguistic and cultural learning in the day-to-day practices of language teachers. Lang. Learn. J. 53, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2025.2475107

Lawson, G. M., McKenzie, M. E., Becker, K. D., Selby, L., and Hoover, S. A. (2019). The core components of evidence-based social emotional learning programs. Physiol. Behav. 20, 457–467. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0953-y

McCallops, K., Barnes, T. N., Jones, I., Nelson, M., Fenniman, J., and Berte, I. (2019). Incorporating culturally responsive pedagogy within social-emotional learning interventions in urban schools: an international systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 94, 11–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2019.02.007

McCormick, M. P., Cappella, E., O'Connor, E. E., and McClowry, S. G. (2015). Social-emotional learning and academic achievement: using causal methods to explore classroom-level mechanisms. AERA Open 1, 1–26. doi: 10.1177/2332858415603959

Miqawati, A. H., Wijayanti, F., and Purnamasari, A. I. (2024). Integrating local culture in english language teaching : enhancing authentic materials and cultural awareness. J. Eng. Acad. Prof. Commun. 10, 100–106. doi: 10.25047/jeapco.v10i2.5096

Mutiara Ayu (2020). Evaluation cultural content on english textbook used by efl students in Indonesia. JET 6, 183–192. doi: 10.33541/jet.v6i3.1925

Neth, E. L., Caldarella, P., Richardson, M. J., and Heath, M. A. (2020). Social-emotional learning in the middle grades: a mixed-methods evaluation of the strong kids program. RMLE Online 43, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/19404476.2019.1701868

Nguyen, T. T. K., and Phan, H. M. (2020). Authentic assessment: a real life approach to writing skill development. Int. J. Appl. Res. Soc. Sci. 2, 20–30. doi: 10.51594/ijarss.v2i1.97

Niman, E. M., Budijanto, A., stina, I. K., Susilo, S., and Darong, H. C. (2020). Local culture in social studies textbooks: is it contextualised? Int. J. Innov. Creativ. Chang. 11, 293–310. Available online at: https://www.ijicc.net/index.php.ijicc-editions/2020/159

Olugbenga, B., and Ridwan, M. (2025). The case study method : a paradoxical research specificity and multiplicity. BIoHS. J. 7, 168–174. doi: 10.33258/biohs.v7i2.1323

Pahor, T., and Nicholls, C. D. (2025). Classroom teacher's perspectives on social emotional wellbeing in the middle years. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 45, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2025.2467940

Ratminingsih, N. M., and Budasi, I. G. (2018). Local culture-based picture storybooks for teaching English for young learners. SHS Web Conf. 42, 1–6. doi: 10.1051/shsconf/20184200016

Rezaei, S., and Latifi, A. (2020). Iranian EFL learners' identity construction in a critical reflective course: a case of an online course. Open Learn. 35, 63–81. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2019.1632700

Roberts, S. L. (2014). A review of social studies textbook content analyses since 2002. Soc. Stud. Res. Pract. 9, 51–65. doi: 10.1108/SSRP-03-2014-B0004

Şeker, M. (2024). A study on how environmental issues are discussed in social studies textbooks. Environ. Dev. Sustain.26, 21325–21352. doi: 10.1007/s10668-023-03532-2

Shapira, N., and Amzalag, M. (2025). Do teachers promote social-emotional skills? The gap between statements and actual behavior. Cogent Educ. 12, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2025.2465919

Suharyanto, A., and Wiflihani, W. (2024). Preserving local culture in the era of globalization: balancing modernity and cultural identity. Path Sci. 10, 5001–5005. doi: 10.22178/pos.102-16

Wade, R. C. (1993). Content analysis of social studies textbooks: a review of ten years of research. Theory. Res. Soc. Educ. 21, 232–256. doi: 10.1080/00933104.1993.105033

Wang, H. C. (2023). Facilitating english L2 learners' intercultural competence and learning of english in a Taiwanese university. Lang. Teach. Res. 27, 1–17. doi: 10.1177/1362168820969359

Wattanawongwan, S., Smith, S. D., and Vannest, K. J. (2021). Cooperative learning strategies for building relationship skills in students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Beyond Behav. 30, 32–40. doi: 10.1177/1074295621997599

Weissberg, R. P. (2019). Promoting the social and emotional learning of millions of school children. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 65–69. doi: 10.1177/1745691618817756

Weissberg, R. P., and Cascarino, J. (2013). Academic learning + social-emotional learning = national priority. Phi Delta Kappan 95, 8–13. doi: 10.1177/003172171309500203

White, A. M., Akiva, T., Colvin, S., and Li, J. (2022). Integrating social and emotional learning: creating space for afterschool educator expertise. AERA Open 8, 1–18. doi: 10.1177/23328584221101546

Williamson, B. (2017). Decoding classdojo: psycho-policy, social-emotional learning and persuasive educational technologies. Learn. Media Technol. 42, 440–453. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2017.1278020

Wood, P. (2018). ‘We are trying to make them good citizens': the utilisation of SEAL to develop ‘appropriate' social, emotional and behavioural skills amongst pupils attending disadvantaged primary schools. Education 46, 3–13. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2017.1339724

Keywords: character, integration, local culture, social emotional learning, teaching

Citation: Niman EM (2025) Embedding local culture in social studies: pathways to strengthen social-emotional learning in primary education. Front. Educ. 10:1655528. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1655528

Received: 28 June 2025; Accepted: 01 September 2025;

Published: 01 October 2025.

Edited by:

Zalik Nuryana, Ahmad Dahlan University, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Huyen-Trang Luu-Thi, Ho Chi Minh City Pedagogical University, VietnamNurul Hidayah, Universitas Ahmad Dahlan Fakultas Psikologi, Indonesia

Apriyanda Kusuma Wijaya, Univesitas Islam Negeri Siber Syekh Nurjati Cirebon, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Niman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erna Mena Niman, ZXJuYW5pbWFuNzlAZ21haWwuY29t

Erna Mena Niman

Erna Mena Niman