- 1Faculty of Education and Liberal Arts, INTI International University, Nilai, Malaysia

- 2Department of English Language and Literature, College of Social Science and Humanities, Wolkite University, Welkite, Ethiopia

The teaching of English to young learners requires careful consideration, as early childhood is a crucial period for acquiring a second or foreign language. In Ethiopia, however, research on this topic has been limited, with most studies focusing on secondary and tertiary education. This study, therefore, sought to examine the instructional practices of EFL teachers in relation to five widely recommended principles for teaching English to young learners, namely focusing on language use, incorporating enjoyable and varied classroom activities, integrating songs, stories, rhymes, games, and drama, utilizing objects, pictures, and actions, and establishing classroom routines. A descriptive case study design was employed, involving English teachers and school principals from primary schools. Data were collected through classroom observations and interviews, followed by a four-stage qualitative data analysis method involving coding, categorization, theme development, and interpretation. The findings revealed a significant gap between teachers’ instructional practices and the principles of effective English language teaching for young learners. While teachers demonstrated some awareness of students’ needs, their methods were largely shaped by contextual challenges and a lack of specialized training in young learner pedagogies. Addressing these gaps will require a comprehensive approach, including teacher training, improved resources, and policy reforms to foster an environment conducive to effective English instruction for young learners.

Introduction

Despite the pivotal role of English in Ethiopia as a language of education, commerce, and international communication, research on the teaching of English to young learners (EYL) remains scarce. Most existing studies have focused on secondary or tertiary levels, leaving primary schools, where learners are at their most receptive stage for second language acquisition, largely overlooked. This neglect is paradoxical, as the early primary years are widely recognized as the most crucial period for building the foundations of communicative competence in a foreign language. Addressing this gap is vital because without strengthening English teaching practices at the primary level, efforts at higher levels of education are unlikely to succeed.

The teaching of a foreign language to young learners requires particular attention. Research suggests that children between the ages of 7 and 11, Ethiopia’s first-cycle primary school age group, have the greatest potential to acquire second languages rapidly and efficiently (Hu, 2016). At this stage, they also possess short attention spans and high levels of physical energy, which require specialized pedagogical strategies (Berns and Matsuda, 2020; Lopez-Caudana et al., 2022). Accordingly, scholars have recommended five guiding principles for effective EYL instruction: (a) focusing on meaningful language use; (b) incorporating enjoyable, varied, and achievable classroom activities; (c) integrating songs, rhymes, stories, games, and drama; (d) utilizing objects, pictures, and actions; and (e) establishing predictable classroom routines (Slatterly and Willis, 2001; Kassa and Abebe, 2023; Copland and Garton, 2024; Vijayaratnam et al., 2025).

These considerations do not only meet the needs of the young learner but also make language teaching effective. Focusing on the use of language in meaningful contexts, for example, is believed to promote functional and real-life language use, providing learners with opportunities for meaningful communication which lays the foundation for developing communicative competence (Salmanova, 2025). Incorporating enjoyable, engaging, achievable, and varied classroom activities can foster learner engagement and participation. To achieve this, the integration of individual, pair, and group interactions, alongside diverse classroom activities such as role-plays and simulations, can be highly effective (Mundelsee and Jurkowski, 2021). For young learners, the use of songs, stories, rhymes, games, and drama can bridge language learning with their lived experiences, encourage active participation, and improve phonological awareness (Copland and Garton, 2024). Additionally, incorporating objects, pictures, and actions during lessons can enhance comprehension and maintain learners’ attention (Salmanova, 2025; Adil, 2020; Akdoğan, 2017; Delibegović and Pejić, 2016; Denzin, 1978). Establishing predictable classroom routines, such as greetings, review sessions, and structured lesson transitions, helps learners follow lessons smoothly, build confidence, and develop a sense of familiarity with classroom procedures (Muthukrishnan et al., 2024; Mundelsee and Jurkowski, 2021).

In the Ethiopian education system, primary schooling covers Grades 1–8, with the first cycle comprising Grades 1–4. Children typically begin Grade 1 at the age of seven and complete the first cycle by the age of 11, which corresponds to the period when they are categorized as “young learners” (Slatterly and Willis, 2001). At this level, English is taught as a compulsory subject, while it becomes the medium of instruction in secondary and tertiary education (Ministry of Education, 2009; Kassa and Abebe, 2023). However, learners’ English proficiency remains poor, and teachers often lack the specialized training required for young learners (Alamiraw, 2005; Mebratu, 2015). These challenges underscore the importance of investigating how English is taught at the first-cycle level and what difficulties teachers face in aligning their practices with EYL principles.

Statement of the problem

In the Ethiopian educational context, challenges in English language proficiency persist among both learners and teachers across various levels of schooling. Alamiraw (2005) reported that learners’ knowledge of English was poor, and teachers could not help them since they themselves were not proficient in the language. Similarly, Mebratu (2015) rated the status of English in Ethiopian schools as very poor. A study by Mekonnen and Roba (2017) in Adama Town high schools also found that students attributed their performance in learning English to factors such as lack of qualified teachers and insufficient exposure to the language, indicating ongoing challenges in English language education. Furthermore, a study by Tadesse (2022) revealed that instructors faced challenges in effectively implementing communicative approaches, often due to limited proficiency and traditional teaching practices. These findings underscore the persistent difficulties in English language proficiency among both students and teachers in Ethiopia.

Although English proficiency appears to be a challenge for both students and teachers, primary schools, distinct from secondary schools and higher education in various ways, have not received adequate attention. It is obvious that understanding the contexts in secondary schools and higher education may not significantly contribute to solving the problems in primary schools. This is because primary schools are different from the other levels of schooling in aspects like: the age of the learners which in turn shapes the teaching approaches, the qualification of the teachers, the instructional materials, and the culture of the schools, etc. (Aweke, 2016; Kang, 2017; Littlewood, 2007a; McCloskey et al., 2006; Nguyen, 2024). More importantly, the age of the learners at the primary schools, especially the first cycle, is very vital as it is the time the children learn a second/foreign language best. Hu (2016, p. 2164) stated that: “Young learners probably have great potential to acquire second languages rapidly, efficiently and proficiently, whereas adults or adolescents are at an inferior position in second language acquisition because of the age factor proposed by many linguists.”

It is therefore a paradox that researchers trying to address the problem of teaching English ignore the grade level at which learners learn the language best. Hence, it is vital to address this gap as any attempt to solve the problem at the grassroots level makes huge contributions. The motive of this research arises from the concern that the important level of instruction where the learners can easily learn English and develop the fundamental skills essential to understanding the lessons in the forthcoming grades is disregarded. Thus, this study explored the English language teachers’ practices and the challenges of teaching English to young learners.

Objectives of the study

Gaining insights into how English teachers teach young learners in the first cycle of primary schools is essential for identifying key issues and developing effective solutions. Therefore, this study aimed to achieve the following objectives:

a. To examine how EFL teachers’ instructional practices align with the five widely recommended principles for teaching English to young learners.

b. To investigate the challenges that impact the implementation of these principles and their influence on overall instructional practices.

Research questions

Accordingly, this study sought to answer the following research questions:

a. How do EFL teachers’ instructional practices align with the five widely recommended principles for teaching English to young learners?

b. What challenges do teachers face in implementing these principles, and how do these challenges affect their instructional practices?

Literature review

International perspectives on teaching English to young learners

The teaching of English to young learners (EYL) has received increasing scholarly attention worldwide. Research highlights that young learners, typically between the ages of 7 and 11, have unique cognitive, emotional, and social characteristics that require specialized pedagogical approaches (Hu, 2016; Lopez-Caudana et al., 2022). Scholars have proposed several principles for effective EYL instruction, including the use of meaningful language in context, varied and engaging classroom activities, integration of songs, rhymes, games, and stories, use of visual and physical supports, and establishment of predictable routines (Slatterly and Willis, 2001; Copland and Garton, 2024; Vijayaratnam et al., 2025). These principles have been widely applied across different countries, although their implementation has often been constrained by challenges such as large class sizes, limited resources, and insufficient teacher preparation (Mundelsee and Jurkowski, 2021; Muthukrishnan et al., 2024).

Ethiopian research on EYL

In the Ethiopian context, previous studies have highlighted both the opportunities and challenges of teaching English at the primary level. For example, Mijena (2014) reported that insufficient teacher preparation hindered effective classroom practices, while Bedilu and Degefu (2025) found that limited resources and lack of training in young learner pedagogy constrained teachers’ ability to apply communicative methods. Broader ministerial reports also confirm these findings: the Ministry of Education (2018, 2022) noted persistent challenges in English instruction across the first cycle of primary schools, including shortage of trained teachers, inadequate materials, and low student achievement. Together, these studies suggest that while the importance of English in Ethiopia is widely acknowledged, the conditions for effective EYL instruction remain underdeveloped.

Research gap and rationale for the present study

Despite these contributions, there remains a lack of systematic research on how Ethiopian teachers’ classroom practices actually align with internationally recommended principles for teaching English to young learners. Few studies have examined both classroom practices and the contextual challenges teachers face, leaving an important gap in understanding how global EYL principles are adapted (or constrained) within the Ethiopian primary school system. The present study addresses this gap by investigating the instructional practices of Ethiopian EFL teachers in relation to the five recommended principles and by exploring the major challenges that affect their implementation.

Methodology

Research design

The major objectives of this study were to explore how EFL teachers teach English to young learners against the recommended principles and investigate the challenges. Due to the dearth of research in the area, the researchers aspired to understand the teachers’ practices and the challenges in-depth to make the findings serve as springboards for further studies. To achieve these, a qualitative case study design was employed. This agrees with the reasons Yin (2003) suggested for the use of a case study as a research design as case study design can be considered when the researchers are interested in answering ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions and disclose the contextual conditions. Yin (2003) categorizes case studies as explanatory, exploratory, or descriptive. The descriptive case study design which is used to describe an intervention or phenomenon and the real-life context in which it occurred fits the purpose of this study. Hence, we employed a descriptive case study design.

Sample size and sampling technique

The participants of the study were English language teachers and school principals of the first level of primary schools in Gurage Zone, Ethiopia. Although teachers were the main participants, principals were included to provide supplementary contextual information. Their perspectives were not analyzed as central data but were used to triangulate teachers’ responses and to offer insights into administrative support, resource allocation, and evaluation practices. Including principals thus ensured a more comprehensive understanding of the conditions shaping teachers’ instructional practices. Ten of the 12 observed teachers were females. The most experienced teacher had 28 years of teaching experience, while the least experienced had served for 8 years, with an average teaching experience of 18 years. All 12 teachers held a diploma in English language teaching, and four were pursuing their BA degree in English Language and Literature.

In a qualitative case study design, it is advisable to select samples that can provide in-depth information about the issue under investigation (Dörnyei, 2007). This is because the focus in case study design is not on how representative the samples are but how much detail they can provide or can be gathered. Therefore, it was important to choose the schools where experienced English language teachers were working. This arises from the belief that valuable and in-depth data can be gathered from the teachers with many years of teaching experience than the novice ones. In the Ethiopian context, the more experienced teachers are often found in towns than the schools in remote areas. Therefore, the study was conducted in six purposively selected primary schools. A school was chosen from each of the following districts: Wolkite, Butajira, Emdiber, Agena, Arekit, and Wosherbe. In each of the selected schools, there were two English teachers teaching grades one to four. Hence, we had a total of 12 English teachers and six principals. In a nutshell, the purposive sampling technique was used to select the six schools; comprehensive sampling was used to select the 12 English teachers and the six principals.

Data collection instruments

Data were gathered through two instruments: classroom observations and semi-structured interviews. The classroom observation tool was a checklist designed to capture five domains: teachers’ use of language, the range and quality of classroom activities, the integration of songs, stories, rhymes, games, and drama, the use of objects, pictures, and actions, and the establishment of classroom routines. The checklist served as a structured guide for recording evidence on how closely teachers’ practices reflected recommended principles for teaching English to young learners.

The interview protocols were developed to complement the observations by exploring teachers’ and principals’ perspectives. For teachers, guiding questions explored their understanding of teaching English to young learners, the methods and activities they used, and their reflections on contextual challenges. Example questions included: “How appropriate do you think your current teaching methods are for young learners?,” “What kinds of classroom activities do you usually use?,” and “How do you expose your students to English during lessons?” For principals, questions focused on their evaluation of English teaching in their schools, the adequacy of resources, and support for teachers. Examples included: “What are the main challenges you see in teaching English at the primary level?” and “How adequate are the resources available for English teaching in your school?”

Both teacher and principal interview guides were reviewed by experts in English language education to ensure validity. The protocols were then pilot tested with one teacher and one principal outside of the study schools, and minor adjustments were made for clarity. This process ensured that the instruments were appropriate for the context and capable of eliciting rich, relevant data.

Data collection procedures

As qualitative case study design requires a closer approach, the researchers went through the following procedures in their collection of data. The directors and the English language teachers were made to understand the objectives of the research. Once their consent was obtained, the data collection procedure started with classroom observation. It was a non-participant classroom observation that was conducted for 2 months. Each teacher was observed an average of four times; thus, the researchers observed 48 English classes. The observed classes had a maximum of 72 students and a minimum of 49, with an average of 63 students per class. The seating arrangement followed a traditional setup, where students sat in rows facing the blackboard. Each desk accommodated three students, and the desks were fixed in place. Most school compounds were spacious; however, they lacked playground equipment for young students. The researchers took field notes during the classroom observation but also used audio-recording material with the consent of the teachers for the completeness of the information. Next to the classroom observation, the researchers interviewed the teachers and the principals. The interview was conducted in Amharic, the national and working language, and later transcribed into English.

Methods of data analysis

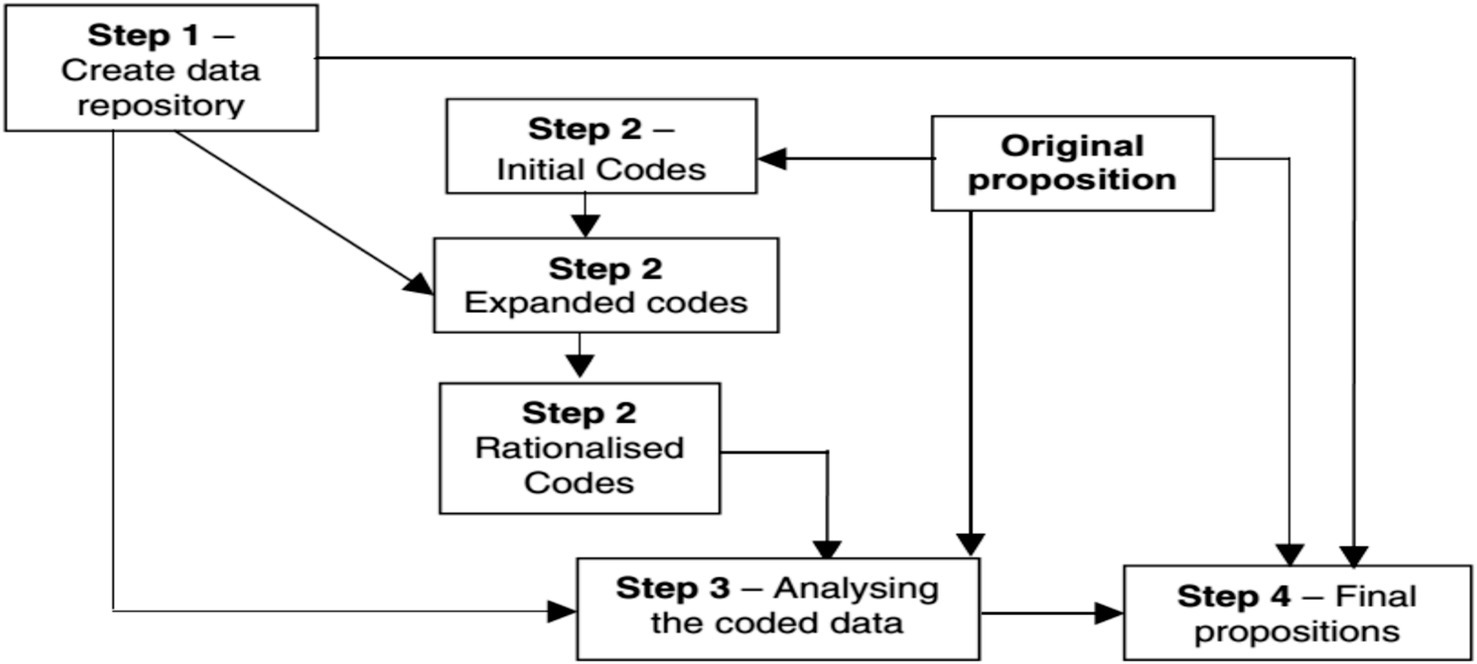

The data were analyzed using a qualitative thematic analysis approach. Classroom observation notes and audio transcripts, as well as interview transcripts, were first read repeatedly to achieve familiarity with the content. The analysis followed a four-step process which is suggested by Atkinson (2002), was employed. These include coding, categorization, theme development, and interpretation. Initial codes were assigned to segments of the data that captured recurrent ideas, practices, and challenges related to English teaching at the lower primary level. These codes were then grouped into broader categories that reflected the central principles of English instruction for young learners. The qualitative data analysis was assisted by the Open Code software program, which was used to systematically organize codes, merge them into categories, and track relationships across data sources.

Through this process, themes were identified that structured the analysis and presentation of findings. These included: focusing on the use of language, using enjoyable, achievable, and varied classroom activities, use of songs, stories, rhymes, games, and drama, using objects, pictures, and actions, and establishing classroom routines. Data from the interviews with teachers and principals were analyzed alongside the observation data to provide deeper insights into these themes and to highlight systemic and contextual challenges influencing classroom practice. The triangulation of observation and interview data ensured that the findings were grounded in both actual classroom practices and the perceptions of key stakeholders. Figure 1 presents the steps by Atkinson (2002).

Figure 1. Four steps to analyze data from a case study method (Atkinson, 2002, p. 2).

Trustworthiness

Qualitative studies consider credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability to ensure trustworthiness (Anney, 2014). To ensure the trustworthiness of the inquiry, the following were done: selecting participants purposively, lengthy engagement in the research site, member checks, provision of a thick description of the study, and keeping all the necessary data. Besides, a case study design is known as a method of triangulation. In this regard, there are four different forms of triangulation: data triangulation, investigator triangulation, theory triangulation, and methodological triangulation (Fusch et al., 2018). Of these four types of triangulations, data triangulation and investigator triangulation were employed in this study. Data triangulation was achieved by comparing evidence from classroom observations, teacher interviews, and principal interviews. Investigator triangulation was addressed through expert consultation during the development of interview protocols and in the review of coding and categorization, which helped minimize researcher bias and enhance the credibility of the analysis.

Findings

This section presents the findings of the study, organized around the two research questions. The first part reports results from classroom observations, focusing on how teachers’ practices align with the five recommended principles for teaching English to young learners. The second part presents findings from teacher and principal interviews, highlighting the challenges teachers face in applying these principles in their classrooms. Only empirical findings are reported here; details regarding participants and procedures have been moved to the Methods section for clarity.

Results from the classroom observations

Contextual information

Classroom observations revealed several patterns in teachers’ instructional practices. Overall, teachers demonstrated varying degrees of alignment with the five recommended principles for teaching English to young learners. Some teachers incorporated songs, group activities, and visual aids to engage students, while others relied heavily on rote repetition and teacher-centered methods. Despite these differences, most lessons showed limited use of interactive and playful strategies that are widely recommended for young learners.

Focusing on the use of language

In the observed classrooms, particularly in grades one and two, teachers typically began their lessons with routine greetings. In four of the schools, first-level primary students attended morning sessions, and they would stand up as a sign of respect whenever the teacher entered the classroom. The greeting exchange followed a structured pattern:

Teacher: Good morning, students.

Students: Good morning, teacher.

Teacher: How are you?

Students: I am fine thank you, and you?

Teacher: I am fine. Sit down, please.

Students: Thank you, teacher.

Almost all students appeared very familiar with this greeting routine. They responded confidently, often in loud voices.

Following the greeting, teachers typically asked students to recall the previous lesson. It was at this early stage of the lesson that code-switching occurred. Teachers predominantly used Amharic or Guragegna, most often Amharic, when asking students to recall what they had learned in the previous session. Some teachers attempted to use English, but their phrases were often brief and unclear. Examples included:

“The previous lesson, the previous lesson” (T3)

“Yesterday lesson” (T4)

“Yesterday we learn” (T9)

Despite the language variations, students seemed to understand what was expected after the greeting. Once given permission to sit, they instinctively flipped back through their exercise books to review past lessons. During this review, students predominantly spoke in Amharic. Teachers acknowledged and praised their efforts, with some encouraging them to use English.

However, when teachers explicitly asked students to speak in English, one of the following two things typically happened: students either stopped responding or managed only a single word or short phrase. For instance, in one case, a grade four teacher (T10) asked a student to explain a previous lesson in English. The student, who had been describing the structure and function of the simple present tense, simply said, “habitual action and truth” and suddenly sat down. Similarly, a grade two student who had been revising the difference between this and that fell silent and sat down when asked to use English.

When urging students to switch to English, the teachers did not provide scaffolding or support to help students transition from Amharic to English effectively. They used simple directives such as “Speak English” (T3) and “In English” (T9).

After recalling the previous lesson, teachers typically introduced the day’s lesson. They did this by writing the lesson title and page number on the blackboard and instructing students to turn to the corresponding page in their textbooks. However, this was not the case in all schools, as some students did not have textbooks. In two particular schools, students shared textbooks in groups. As a result, teachers often copied notes from the textbook onto the blackboard. This process was one of the most time-consuming parts of the lesson, as students took a considerable amount of time to copy the notes. Additionally, they frequently asked teachers to read the notes aloud.

Translation was the primary teaching technique used by almost all teachers when introducing new lessons. For example, T1, a grade one teacher, was teaching greetings to her students. She first wrote Good morning, Good afternoon, and Good evening on the board. She then turned to the students and asked them how they would greet someone in the morning, afternoon, and evening in Amharic. Both the teacher’s questions and the students’ responses were in Amharic. After this discussion, she provided the English equivalents of the greetings.

Next, she asked how they would respond if someone greeted them in Amharic during these three times of the day. The students gave the same response regardless of the time. The teacher acknowledged their answers but explained that in English, the response must match the greeting. The teacher explained to the learners the difference between these greetings, especially the responses, in English and Amharic. She clarified that if someone says Good morning, the correct reply is also Good morning, and the same applies to Good afternoon and Good evening. She then conducted a whole-class activity where she greeted the students, and they responded accordingly:

Teacher: Good morning.

Students: Good morning.

Teacher: Good afternoon.

Students: Good afternoon.

Teacher: Good evening.

Students: Good evening.

Similarly, T12, a grade four teacher, was teaching how to form questions using Wh-words and used translation as a key technique. She began by writing five Wh-words on the blackboard—what, where, when, who, and why—and asked students for their meanings in Amharic. She then asked, still in Amharic, why these words were called Wh-words. To explain, she directed students’ attention to the first two letters of each word, pointing out that they all began with “WH,” which is why they are categorized as Wh-words. Following this, she wrote example questions using each Wh-word on the board and instructed the students to create at least one question for each of the Wh-words.

The teachers prioritized teaching about the language rather than helping students practice using it. For instance, one of the writing lessons in the Grade 3 English textbook (page 81) required students to practice writing correct sentences. The lesson included three activities that were linked to the reading and listening lessons of the unit. In the first activity, students were given five words from the listening and reading texts, (profit, sell, coffee, vital, and ceremony) and asked to write their own sentences using each word. The second activity provided three pairs of singular and plural nouns and instructed students to create sentences using them. The third activity required students to write five sentences about a cash crop, a topic related to the unit’s reading passage. Although all three activities were designed to help students practice writing correct sentences, the teacher (T7) spent nearly 30 min of the 40-min lesson explaining the concept of a sentence in Amharic. She discussed sentence structure, focusing on subjects, verbs, and objects. Eventually, she assigned only the first activity for in-class work, but none of the students completed it. As a result, she gave the first task as homework instead. Similarly, T10, who was teaching Grade 4 students, spent almost the entire 40-min lesson explicitly explaining the forms and uses of the simple present tense through her own examples. However, the lesson in the Grade 4 English textbook (pages 45–47) was designed to encourage students to practice the structure implicitly. For example, the first activity asked students to write about their daily routines at home.

The Grade 3 and Grade 4 teachers appeared highly focused on teaching grammar lessons. However, the explicit grammar sections in the English textbooks for these grades are limited and are presented in a communicative manner. Despite this, the teachers spent excessive time explaining these few grammar lessons using the translation method.

For example, on pages 67–78 of the Grade 4 English textbook, there is a grammar lesson on comparative adjectives. T11 took three full periods to complete this lesson and even went beyond the textbook content by introducing superlative adjectives.

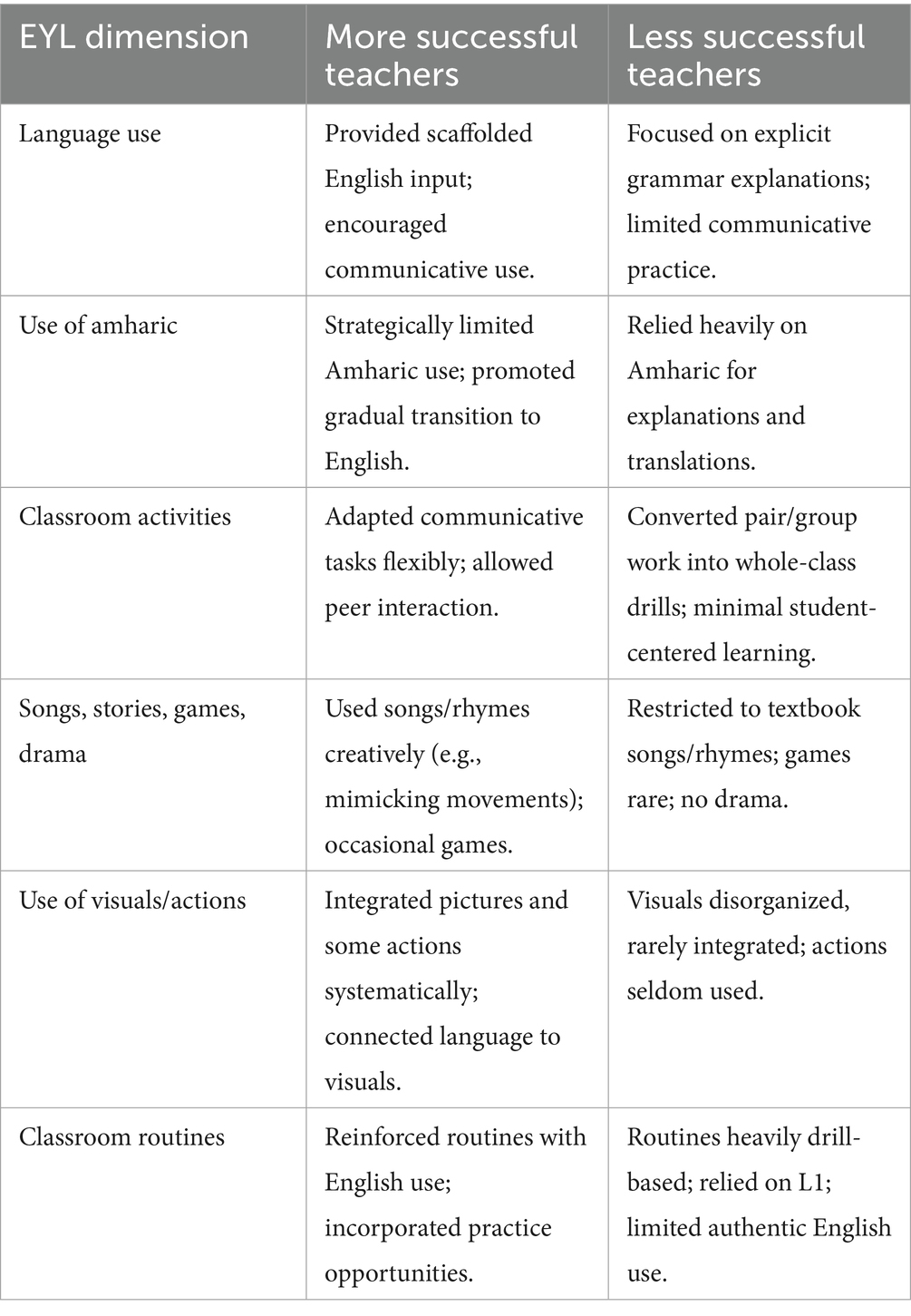

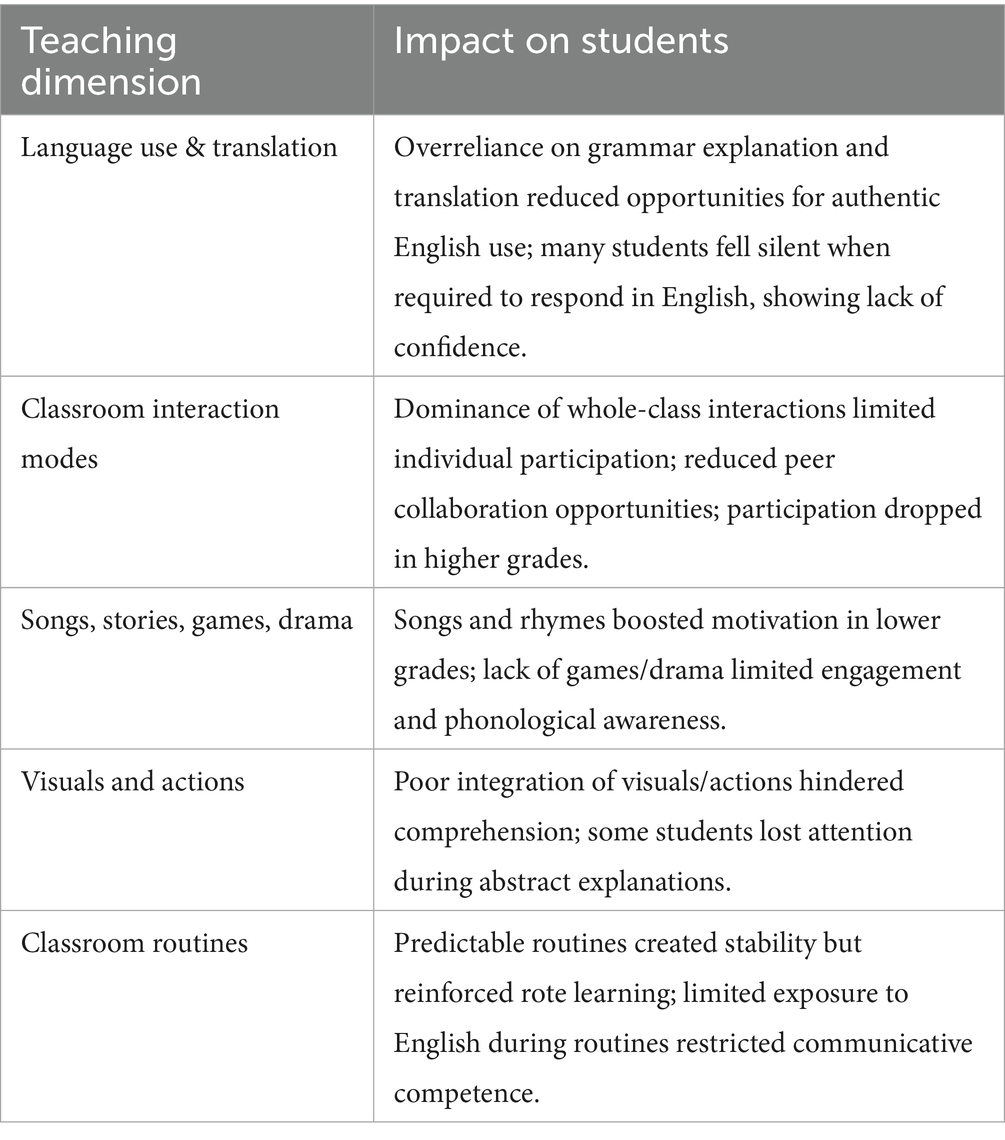

Clearly, the excessive use of Amharic by both teachers and students, the teachers’ prioritization of grammar lessons over activities that present the language in context, and their reliance on traditional language teaching approaches hindered students’ ability to use English meaningfully and communicate effectively which lays the foundation for developing communicative competence. See Table 1 for further detail.

Using of enjoyable, achievable and variety of classroom activities

The classroom activities used by the teachers were evaluated based on their enjoyability, achievability, and variety.

Enjoyability of the classroom activities

Enjoyable classroom activities are those that engage learners, stimulate their motivation and participation, and create a positive and supportive atmosphere. In terms of engagement, we observed two key patterns. When teachers asked students to participate in classroom activities, most students in grades one and two eagerly raised their hands. However, participation declined as grade levels increased, with fewer students volunteering in grade four compared to grade three. Interestingly, even when activities were not directly connected to students’ experiences, their participation levels remained unchanged. This suggests that students’ engagement, motivation, and participation may not be strongly influenced by the activities themselves but rather by their age.

Another significant factor affecting the enjoyability of classroom activities was the medium of instruction. When teachers used English exclusively, few or no students were willing to participate. For instance, in one case, a teacher (T10) instructed grade four students in English to look at pictures on page 109 of their English textbook and describe them individually to the class. She also emphasized that their responses should be in English. After giving students 3 min to observe the pictures, none were willing to participate. Frustrated, the teacher switched to Amharic to explain the task. After doing so, two students volunteered. This indicates that language barriers significantly influenced student participation.

Student engagement was also affected by the presence of willing “icebreakers.” In grades three and four, it was often difficult to find the first volunteer. However, once one student answered, many others followed. This pattern suggests that having an initial participant can encourage broader classroom engagement.

Achievability of the classroom activities

The achievability of classroom activities in young learners’ classrooms can be determined by factors such as the use of appropriate and clear instructions, learners’ familiarity with the task, time appropriateness, and the availability of support.

Regarding instruction, it is closely related to the language the teachers use. Teachers should use expressions that align with the learners’ proficiency level. It may sometimes be important to support instructions with gestures and visual aids. Although the English vocabulary used by the teachers appeared to be suitable for the students’ level, the students seemed happier when instructions were given in Amharic. Clearly, limited use of the students’ mother tongue can facilitate the achievability of tasks. However, the observed use of Amharic by the teachers was excessive.

The learners, even those in grade one, were familiar with the form of the tasks, as teachers often used common activities. Although this limited the variety of activities, it supported achievability. Teachers were generally supportive while students were engaging in classroom activities. One common misconception was regarding time allocation. Teachers frequently assigned time and communicated it to students. However, almost all teachers used more than twice the allotted time, while some did not specify the time in advance.

Given young learners’ short attention spans, they tend to enjoy shorter and more engaging activities rather than longer ones. In general, while the classroom activities were somewhat achievable, teachers seemed to achieve this unintentionally, often relying excessively on the students’ mother tongue, which is discouraged in English classrooms.

Variety of the classroom activities

The teachers tried to achieve variety by varying both the modes of interaction and the activities. Regarding classroom interaction, the teachers attempted to use the three common modes of interaction: whole-class, group, and pair work. However, whole-class interaction was overwhelmingly dominant, leaving little room for student-centered learning. This was particularly evident in lower grades (Grades 1 and 2), where teachers frequently asked questions and encouraged responses from the entire class.

Pair work, which is typically expected to foster student collaboration, was not conducted between students but rather between the teacher and individual students. In this approach, the teacher initiated an exchange with one student, and once that student completed their response, another student was invited to participate. This limited the opportunities for peer interaction and active student engagement. As a result, whole-class discussions remained the primary mode of interaction, while group and pair activities were rarely implemented.

Five common and frequently used classroom activities were identified: discussions, fill-in-the-blank exercises, teacher-led performance with student descriptions, role-playing, and storytelling. Among these, discussions were predominantly conducted as whole-class discussions, particularly in Grades 3 and 4.

For instance, in Grade 3, on page 86 of the English textbook, there is a reading passage titled “Cutting Trees.” The preceding page presents four brainstorming questions and instructs students to discuss them in groups. However, Teacher T6 modified the activity into a whole-class discussion. Instead of allowing students to engage in small group discussions, she asked the questions one by one, encouraging students to respond either collectively as a class or individually by raising their hands. This practice was not unique to T6; shifting group work into whole-class discussion was a widespread pattern among all observed teachers.

Similarly, pair work was also frequently converted into whole-class activities. A clear example was observed in Grade 4, where page 98 of the English textbook includes a speaking lesson designed for pair work, requiring students to practice asking and answering questions with a partner. However, instead of facilitating pair interactions, Teacher T11 conducted the activity by asking the questions herself, while individual students responded one at a time.

This pattern suggests a strong teacher-centered approach, where whole-class discussions dominated over interactive student-to-student engagement. Both group and pair activities were frequently adapted into teacher-led discussions, limiting opportunities for collaborative learning and student autonomy.

The teachers’ attempts to achieve enjoyment, achievability, and variety in classroom activities were sometimes successful and sometimes not. The crucial point here is that these attempts were not made systematically. For instance, the teachers were promoting the achievability of activities through excessive use of Amharic and by giving students too much time, which often led to disruptions from those who finished early. While the teachers varied classroom activities, they also strayed from the textbook’s guidelines. All of these indicate that the teachers lacked a thorough understanding of classroom activities and how to effectively implement them in young learner classrooms. Table 2 summaries the findings.

Use of songs, stories, rhymes, games and drama

For young learners, the use of songs, stories, rhymes, games, and drama can bridge language learning with their lived experiences, encourage active participation, and improve phonological awareness. The use of songs, stories, rhymes, games and drama therefore were evaluated based on their fostering of the learners’ lived experiences, encouragement of active participation and phonological awareness. Songs and rhymes were relatively used in grades one and two while stories were used in grades three and four. Only one of the grade four English teachers was using games. We have not however come across a teacher who used drama.

The songs and rhymes were directly taken from the students’ textbooks. They were simple, easy to understand, and used clear language. The students appeared happy and motivated whenever they sang songs or repeated rhymes after the teacher. Some teachers, like T5 and T3, were creative in encouraging their learners to sing. For example, T5 once asked grade two students to sing about animals. While the students were calling out the names of animals from the song, the teacher mimicked the animals’ movements. This not only made the song memorable but also helped the students understand the meaning as they sang.

As for the rhymes, teachers used them for two main purposes: vocabulary building and pronunciation practice. To do this, teachers would say the words one at a time and invite the students to repeat after them. However, despite frequent practice, some teachers’ pronunciation of certain words was incorrect, which sometimes led to confusion for the students.

The use of games in young classrooms maximizes playfulness, reinforces vocabulary, and promotes communication. However, despite their significance, only one out of the 12 teachers (T11) incorporated games into her lessons. She sometimes reserved the last 5 min of class for games. She used two games: a question-and-answer game and a “calling a word” game. In the question-and-answer game, she invited an active student to come up, had them think of something, and then the other students asked yes-no questions to guess what it was. In the second game, she gathered five to eight students, and the first student would call out an English word. The next student would then call a word starting with the last letter of the previous word. This continued until only one student remained. Students were not allowed to make mistakes or take too long. Although these games were unrelated to the day’s lesson, T11 used them as a reward for active participation when there were extra minutes available.

Using of objects, pictures and actions

To enhance comprehension and maintain learners’ attention, the teaching of young learners is often accompanied by objects, pictures, and actions. Pictures, in particular, help learners connect abstract words to visual representations. Classrooms are often filled with objects and pictures, and schools have workshops where these materials are prepared or drawn. The walls of the classrooms were covered with pictures, many of which were handmade by teachers or students. Common images, especially in grades one and two, included the English alphabet, words, punctuation marks, body parts, and trees. However, most of these pictures were not arranged properly. Regarding the use of objects, the observed teachers did not adequately incorporate them into their lessons, except for a few instances where teachers encouraged students to bring real objects from home. Incorporating actions, which connect language with physical activity, is also vital in teaching English to young learners. Despite the importance of integrating physical movement into lessons, teachers rarely used this technique. One exception was T6, who once used actions to teach vocabulary. She acted out certain words and asked students to respond accordingly as follow:

Teacher: What am I doing?

Students: Jumping

Teacher: What am I doing?

Students: Walking

Establishing of classroom routines

Teachers were observed establishing predictable classroom routines. The routines they employed were largely similar. The first thing teachers did upon entering the classroom was greet the students. In all classrooms, the greeting followed a three-stage pattern. First, the teacher said, “Good morning” or “Good afternoon,” and the students responded in kind. Second, the teacher asked, “How are you?” to which the students replied, “We are fine, thank you. And you?” Third, the teacher responded, “I’m fine, thank you. Sit down,” and the students replied, “Thank you, teacher,” before taking their seats. This structured three-stage greeting was common across classrooms, regardless of grade level, and students were very familiar with it.

Following the greeting, teachers proceeded with a review of the previous lesson. In grades two, three, and four, teachers used similar expressions and techniques for this revision. They began by informing students that they would be reviewing the previous lesson and then asked them to recall what they had learned the day before. After students provided a summary, the teacher highlighted the key points and introduced the day’s lesson. In grade one, however, teachers did not explicitly announce the revision but instead spent a few minutes reteaching the previous lesson.

The introduction of the new lesson was also consistent across classrooms. Teachers first introduced the topic orally, then wrote it on the board, read it aloud, and asked students to repeat after them. This was typically followed by the teacher writing short notes on the board, based on textbook content, which students then copied into their exercise books. The teacher then proceeded with the main lesson content.

The approach to practicing the lesson varied among teachers. Some teachers, particularly in grades three and four, occasionally ended the session after explaining the lesson without providing further practice. In contrast, teachers in grades one and two were more likely to give students opportunities to practice, though the activities were often drill-based and heavily reliant on the mother tongue.

The language teachers used for praising students, asking questions, and initiating classroom activities was generally consistent across all classrooms. Table 3 presents summary of the classroom observations.

Results from the interviews

This part presents the findings from the interviews with the teachers and the principals. As stated in the Methods section, 12 teachers from six schools were interviewed. Besides, the directors of the schools were also interviewed to have an adequate understanding of the issue under investigation and to cross-check the results. Unfortunately, the researchers did not find the directors of the two schools; hence, interviews were conducted with the vice-directors. The directors had 15–27 years of working experiences in schools; five were degree holders while one had a diploma. All of the directors were males.

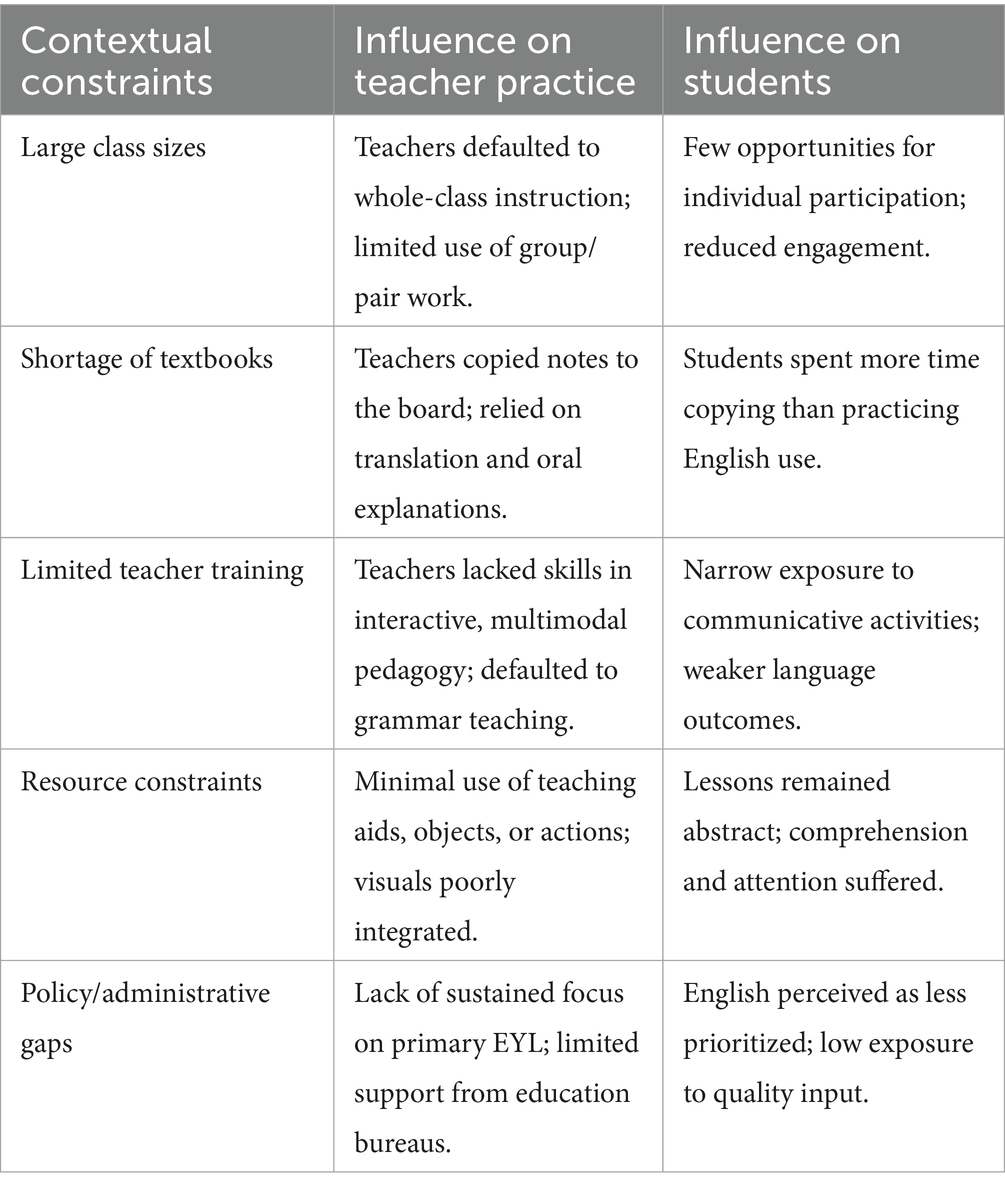

As findings from the interviews revealed, the respondent teachers described teaching English to young learners as an interesting and also tiresome work. As to the teachers, working with young learners makes them feel young. The teachers thought they are working on the future of the generation which they considered as “building the basement” (T5). On the other hand, teaching in first cycle is challenging due to the different contextual factors. Above all, they complained about the attentions given to teaching, particularly to the first cycle of primary school. T8, for example, said: “We feel the Ministry of Education focuses on Universities and somehow on secondary schools. Primary schools are forgotten- no textbooks, no training- look at the classrooms.”

Teachers’ evaluation of how appropriate the teaching methods they employ to the young learners were characterized by mentioning the influencing factors. They thought that it is impossible to talk about methodological appropriateness without textbooks. They reported that there is a severe shortage of textbooks. The teachers also complained about the number of students in the classroom. T11 for example said: “If you go to the classroom, you will be surprised. We have more than 70 students.”

The respondent teachers believed that it is appropriate to consider the characteristics of the learners in planning and teaching. T1 for example said: “I know there is a difference between grades 8 and 3 students. So, the planning and also the implementation should take their levels into consideration.”

As to the words of most of the respondents, they do not only consider the learners’ characteristics but also the existing realities, which is technically called contextual factors. In this regard, T7 said: “I consider the number of students, the lack of the textbook, the learners’ proficiency.” T3 also said: “In planning, I take into account if it is possible to me to finish the textbook in the academic year.”

In replaying to the question that inquires the classroom activities the teachers use, the respondents referred to the two modes of classroom activities than the actual classroom activities. The teachers repeatedly referred to group and pair works than classroom activities. The interviewers therefore gave the interviewees clues regarding classroom activities. As to the explanations, the teachers were told that classroom activities are: repetitions of drills, songs, role-plays, simulations, storytelling etc. They have also been told that group, pair and individual words are modes through which these classroom activities are employed. After the explanation, the teachers listed out the classroom activities they use. As to their responses, it is possible to deduce that the teachers almost used songs and repetition of drills dominantly.

The teachers were also asked if they exposed the learners to the target language. The teachers discussed the significances of exposing the learners to the language in second or foreign language teaching. They indicated that the classroom is the very important place where the students learn and practice English. Most of the participants however were half-hearted to confirm their expose of the learners to English. T9 said: “Often, I use Guragigna (the local language spoken widely in the study area) in the classroom because the students do not understand English.” The other teachers also reported that the students did not have the basic necessary skills to understand the simple instructional languages. They therefore indicated they often use the students’ mother tongue in the classroom.

As to the teachers, it is not time to talk about the quality of the textbook since we are short of it. As to them all students should be provided with a textbook. Not only textbooks, but also there have to be teaching aids and supplementary materials. The teachers reported they have been requesting for materials to prepare teaching aids. As to them, the school administrators did not provide them the materials they requested for. They further indicated that they have attempted to prepare teaching aids from the materials they could find in the schools. They however did consider the teaching materials they prepared from the materials they collected as effective and helpful. T2 for example said: “Learners need to be supported with appropriate teaching aids, yet we are neither provided with ready-made materials nor given the necessary resources to create our own.” T5 further indicated that the teachers need to be trained in preparation and usage of teaching aids. As to T5, the lack of teaching aids is not the only problem but also its preparation and usage. The teachers also needed the students to read supplementary materials at home. However, they reported most of the learners did not even have the textbook let alone supplementary materials.

The respondent teachers agreed that students were not taught rightly to their level, and even indicated that they were not convinced that they were doing their level best. As to them, the teachers were not the only responsible ones because as T3 stated, “The blames are always on teachers.” The teachers defended themselves and kept on mentioning different factors which could be related to the classroom atmosphere, resources, administration, and etc.

In addition to the teachers, the directors have also been interviewed. As administrators of the schools, the teachers have been asked to evaluate the status of English in their school. English was considered as the weakest part of the instructional practices by all respondent directors. D1 for example said: “We identify the teaching of English as a problematic area. We had discussions with the Wereda supervisors and our teachers. Though we came to agreement to tackle some of the challenges, the problem is still with us.” Briefly, all the respondent directors reported the teaching of English is one of weakest sides of the instructional practices.

As to the directors, observing and evaluating the teachers’ teaching practices is part of the educational policy. The English teachers, like all other subject teachers, have been observed and evaluated. As the directors indicated, the supervision is by a team that comprises the director, vice-director and head of the respective departments. In the primary schools, English is part of the ‘Language Department’ to which Amharic and English teachers are members. Hence, English teachers are observed and evaluated at least twice in a semester by a supervising team which comprises the director, vice director and head of the language department. As to the directors, there is an evaluation guideline they use to evaluate the teachers. D3 for example said: “The evaluation guideline may not tell us how appropriate the teaching method is to the level of the learners. We do not even know the appropriate teaching methods.”

The directors indicated that they want the teachers to use teaching methods that are appropriate to the level of the learners. Two of the directors for example reported that they requested the Wordea Education Bureaus to facilitate trainings to English and mathematics teachers to improve their teaching methods. The responses, as the directors, indicated were not positive as the Bureaus did not have budgets for the training the directors demanded.

One of the issues the directors were very concerned about was the textbook. As to D6: “In teaching, the teachers, the schools and textbooks are basics. But we do not have sufficient textbooks. We are giving the textbooks in groups.” Despite the dearth of English textbooks, the directors believed the contents of the English textbooks are sufficient to the level they are prepared for. Besides, they indicated that there are some useful reference books in the library that the students read. The directors further indicated that they encourage the teachers to prepare teaching aids. Look at Table 4 for summary of findings.

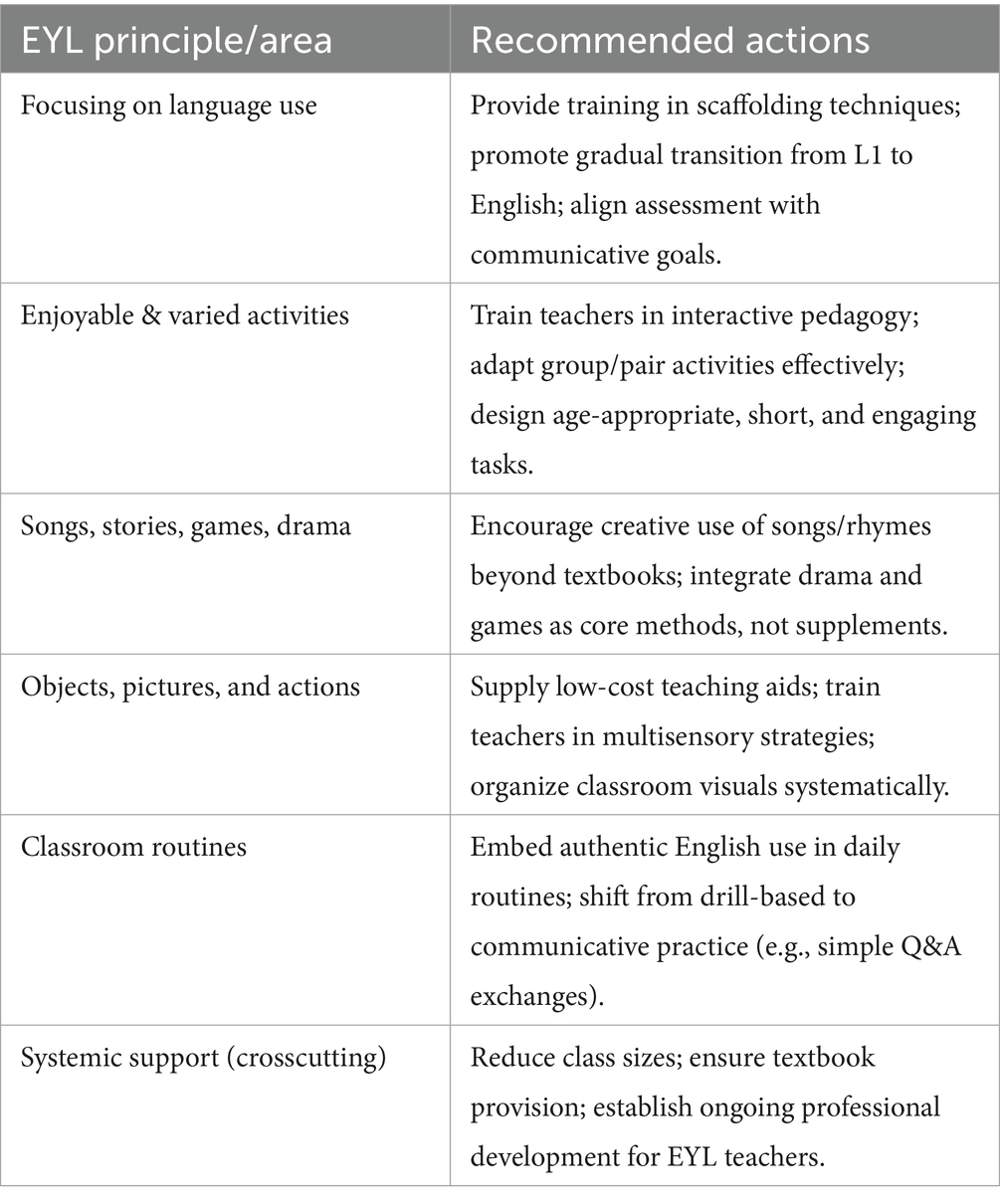

The challenges summarized above illustrate how systemic and contextual constraints such as overcrowded classrooms, shortage of textbooks, and insufficient professional development directly shape teachers’ reliance on traditional methods and limit students’ opportunities for meaningful English use. These findings point to the need for actionable strategies that not only address classroom-level practices but also tackle structural barriers. To this end, the following recommendations synthesize practical steps aligned with the five EYL principles and broader systemic support. Table 5 provides recommendations for strengthening EYL instruction.

Overall, the instructional practices observed had direct and significant implications for students’ learning experiences. The heavy emphasis on grammar explanation and translation limited students’ exposure to authentic English, which in turn constrained their ability to develop communicative competence. Many students became hesitant to participate when English was required, often falling silent or resorting to single-word responses, indicating a lack of confidence and insufficient scaffolding. While younger learners (Grades 1 and 2) showed initial enthusiasm during songs or routine greetings, their motivation and participation declined in higher grades, particularly when classroom tasks demanded independent use of English. The overreliance on whole-class interactions also meant that few students had meaningful opportunities to practice language individually or in pairs, reducing the likelihood of active engagement. These patterns suggest that teacher-centered practices not only shaped classroom dynamics but also directly influenced students’ willingness to participate, their motivation to learn, and ultimately, their potential to internalize English as a communicative tool.

Discussion

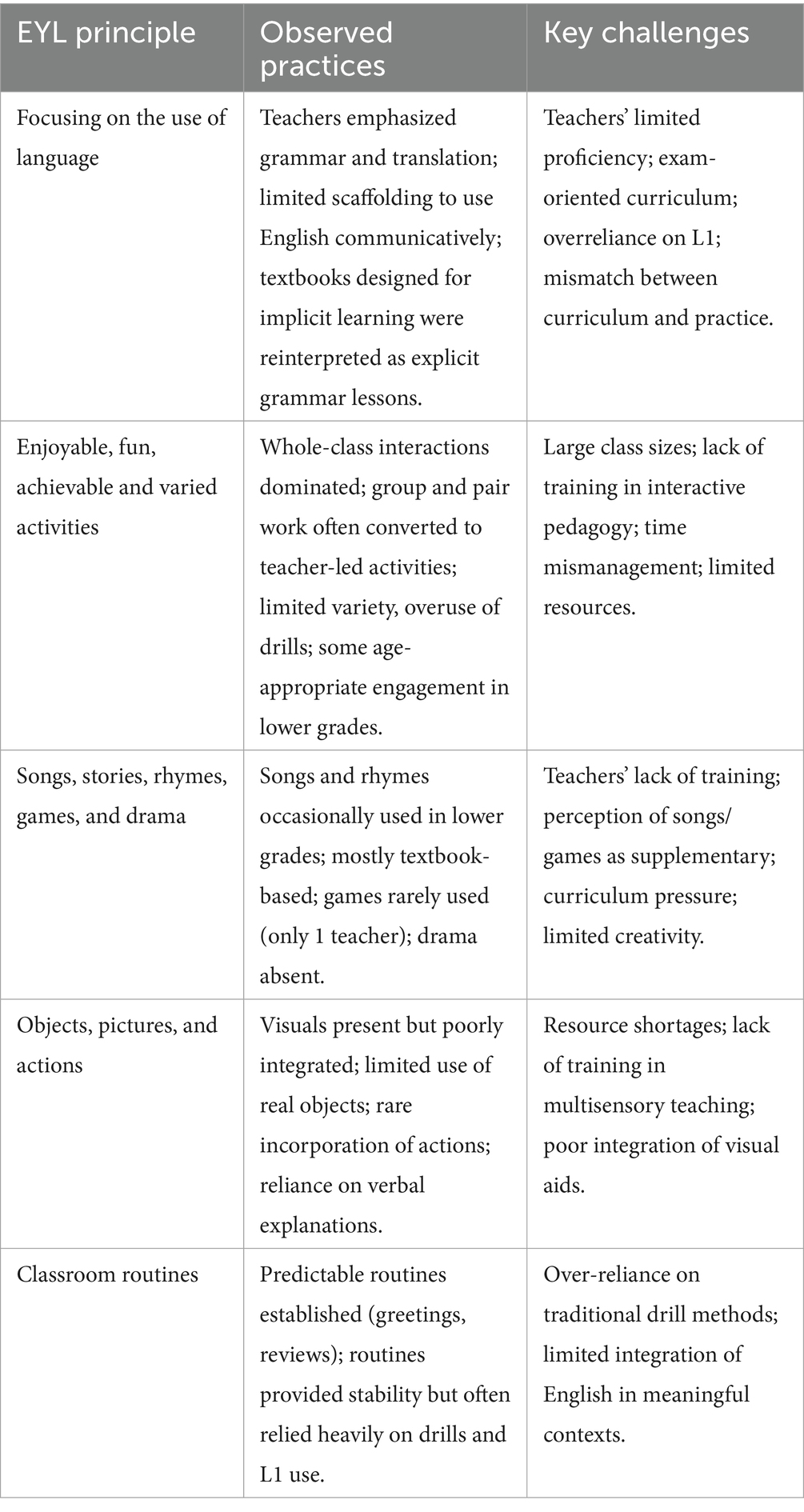

The findings of this study reveal several critical insights into the instructional practices of Ethiopian EFL teachers when teaching English to young learners (EYL) and the challenges they face in implementing widely recommended principles for EYL instruction. The discussion is framed around the five principles identified in the literature: (a) focusing on the use of language, (b) incorporating enjoyable, fun, achievable, and varied classroom activities, (c) utilizing songs, stories, rhymes, games, and drama, (d) using objects, pictures, and actions, and (e) establishing classroom routines. The findings are contextualized within the broader literature on EYL teaching, highlighting both consistencies and divergences.

Focusing on the use of language

The classroom observations indicate that teachers predominantly emphasized teaching about the language, particularly grammar rules rather than enabling students to use English for meaningful communication. This tendency aligns with findings in other EFL contexts where grammar-focused instruction often overshadows communicative practice (Ellis, 2012; Richards and Rodgers, 2014). However, a more critical analysis suggests that this reliance on explicit grammar instruction is not simply a matter of teacher preference but reflects deeper systemic and contextual factors. For example, teachers’ limited proficiency, exam-oriented curricula, and resource constraints may collectively push them toward traditional, form-focused methods, even when curricular materials are designed to promote implicit and communicative learning.

The excessive use of Amharic for instruction further illustrates this tension. While translation can serve as a scaffold for meaning making, its overuse appeared to restrict students’ opportunities to engage authentically with English. These finding echoes research in multilingual contexts where reliance on the mother tongue, though pragmatic, can impede the gradual transition to English as the medium of communication (Paudel, 2020; Safeer et al., 2024). Yet, the degree to which teachers used Amharic varied, suggesting a spectrum of practices: some teachers attempted to strategically limit translation and create space for English interaction, while others defaulted to L1 almost exclusively. This variability highlights the importance of examining not only what teachers do, but how differently positioned teachers navigate the tension between communicative goals and classroom realities.

When considering the reliance on translation and grammar-driven pedagogy together, the observed practices reveal a deeper pedagogical contradiction. While the textbooks encouraged implicit learning through communicative activities, teachers often reinterpreted these tasks through a traditional lens, prioritizing explicit explanation and rule memorization. Such a mismatch underscores the persistence of teacher-centered approaches and a limited uptake of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) principles (Littlewood, 2007a). This misalignment reflects what Ashoori Tootkaboni (2019) also documented in comparable EFL settings: teachers espouse communicative goals in theory but revert to grammar-based practices in implementation.

A cross-case thematic comparison offers further insight. Teachers who were relatively more successful in implementing EYL principles demonstrated two distinct strategies: first, they reduced reliance on Amharic by providing scaffolded English input, and second, they leveraged communicative tasks flexibly rather than rigidly adhering to textbook prescriptions. Conversely, less successful teachers tended to treat communicative activities as supplementary to grammar explanations rather than as central to learning. This contrast suggests that teacher agency, classroom management skills, and attitudes toward CLT significantly mediate the extent to which EYL principles are enacted.

Overall, the findings are not only descriptive of a grammar-focused and translation-heavy pedagogy but analytically reveal the interplay of teacher beliefs, systemic pressures, and contextual realities. The divergence between more and less successful teachers illustrates that while structural challenges constrain practice, individual pedagogical choices and interpretations of CLT principles can make a meaningful difference in students’ opportunities to use English communicatively.

Incorporating enjoyable, fun, achievable and varied classroom activities

The teachers’ attempts to incorporate enjoyable and varied activities were inconsistent and often undermined by contextual challenges such as large class sizes, limited resources, and students’ low proficiency levels. While younger learners (Grades 1 and 2) showed higher levels of engagement, participation declined in higher grades, particularly when English was used as the medium of instruction. This finding aligns with research suggesting that young learners’ motivation and engagement are closely tied to the use of familiar language and age-appropriate activities (Ye, 2024; Cameron, 2010; Pinter, 2006).

The dominance of whole-class interactions over group and pair works further limited opportunities for student-centered learning. This teacher-centered approach is common in contexts where teachers lack training in interactive teaching methods or face logistical constraints such as large class sizes (Busa and Chung, 2024). The conversion of group and pair activities into whole-class discussions reflects a lack of understanding of how to implement collaborative learning effectively, a challenge noted in other studies of EFL teaching in resource-constrained settings (Sun et al., 2022).

Utilizing songs, stories, rhymes, games, and drama

The limited use of songs, rhymes, and games, and the complete absence of drama, highlight a missed opportunity to engage young learners through multimodal and experiential learning. Songs and rhymes, when used, were effective in fostering phonological awareness and motivation, particularly in Grades 1 and 2. However, their use was often restricted to textbook materials, and teachers rarely extended these activities to reinforce language learning. This finding contrasts with studies that emphasize the importance of integrating music, games, and drama into EYL instruction to create a dynamic and engaging learning environment (Brovchak et al., 2024; Shin, 2006).

The underutilization of games and drama may reflect teachers’ lack of training in these methods or their perception of these activities as supplementary rather than integral to language learning. This is consistent with findings from other contexts where teachers prioritize formal instruction over play-based learning due to curriculum pressures or limited professional development opportunities (Garton et al., 2011; Johnstone, 2022).

Using objects, pictures, and actions

The use of visual aids such as pictures and objects was limited, despite their potential to enhance comprehension and maintain young learners’ attention. While classroom walls were adorned with handmade visuals, these were often disorganized and underutilized during lessons. The lack of systematic integration of visual aids into instruction reflects a gap in teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and resource constraints, as noted in other studies of EFL teaching in low-resource settings (Narkabilova and Davidova, 2022).

The rare use of actions to connect language with physical movement further underscores the need for teacher training in multisensory teaching techniques. Research suggests that incorporating physical movement into language lessons can enhance young learners’ retention and engagement (Husanović, 2022; Jusslin et al., 2022; Ansari et al., 2021; Xie, 2021), yet this approach was largely absent in the observed classrooms.

Establishing classroom routines

The teachers’ establishment of predictable classroom routines, such as structured greetings and lesson reviews, provided a sense of stability and familiarity for students. This aligns with research emphasizing the importance of routines in creating a supportive learning environment for young learners (Cameron, 2010). However, the over-reliance on drill-based activities and the limited use of English during these routines suggest a missed opportunity to reinforce language use in meaningful contexts.

Challenges and contextual factors

The challenges reported by teachers, including large class sizes, insufficient textbooks, and limited professional development, are consistent with findings from other studies of EFL teaching in sub-Saharan Africa (Brock-Utne, 2010). These challenges significantly impacted teachers’ ability to implement recommended EYL principles, leading to a reliance on traditional, teacher-centered methods. The lack of training in EYL-specific pedagogies further exacerbated these challenges, as teachers struggled to adapt their practices to the needs of young learners.

The findings also highlight the need for systemic support, including the provision of teaching materials, professional development, and policy reforms to address the unique challenges of teaching English in resource-constrained contexts. As noted by the school directors, the lack of attention to primary education, particularly in the area of English language teaching, undermines efforts to improve instructional practices.

Overall, the discussion highlights a persistent gap between the principles of effective English teaching for young learners and the actual practices observed in Ethiopian classrooms. Teachers’ emphasis on grammar instruction and heavy reliance on translation reflect not only entrenched teacher-centered traditions but also systemic factors such as limited proficiency, exam-oriented curricula, and inadequate resources (Ellis, 2012; Richards and Rodgers, 2014; Paudel, 2020; Safeer et al., 2024). Although some teachers demonstrated partial success by scaffolding input and experimenting with communicative tasks, the overall picture remains one of misalignment with the principles of Communicative Language Teaching, which emphasize meaningful interaction and authentic language use (Littlewood, 2007b; Ashoori Tootkaboni, 2019). The limited use of songs, stories, games, and drama, as well as the superficial application of visual aids and actions, further constrained learners’ opportunities to engage with English in creative and multimodal ways (Brovchak et al., 2024; Narkabilova and Davidova, 2022). Contextual challenges, including large class sizes, shortage of textbooks, and lack of training, reinforced these limitations and shaped classroom practices in ways that reduced students’ motivation and communicative competence (Brock-Utne, 2010). Taken together, these findings suggest that improving EYL instruction in Ethiopia will require both pedagogical change at the classroom level and systemic reforms to ensure teachers are adequately supported in adopting practices that promote authentic language use.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study reveals a significant gap between the instructional practices of Ethiopian EFL teachers and the principles of effective EYL teaching. While teachers demonstrated some awareness of young learners’ needs, their practices were heavily influenced by contextual challenges and a lack of training in EYL-specific pedagogies. Addressing these gaps will require a multifaceted approach that includes teacher training, resource provision, and policy reforms to create an enabling environment for effective EYL instruction.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Wolkite University Research Ethics Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ET: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization. MD: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis. AL: Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adil, M. (2020). Exploring the role of translation in communicative language teaching or the communicative approach. SAGE Open 10, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/2158244020924403

Akdoğan, E. (2017). Developing vocabulary in game activities and game materials. J. Teach. Educ. 7, 31–66.

Alamiraw, G. (2005). A study of perception of writing for academic instruction and writing performance (Unpublished PhD dissertation): Addis Ababa University.

Anney, V. N. (2014). Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: looking at trustworthiness criteria. J. Emerg. Trends Educ. Res. Policy Stud. 5, 272–281. Available at: https://www.scholarlinkinstitute.org/jeteraps/articles/Ensuring%20The%20Quality%20Of%20The%20Findings%20new.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Ansari, M., Ilyas, R., and Shah, S. W. A. (2021). Exploring challenges in implementation of learner-centered approach in Pakistani EFL classrooms. J. Lit. Lang. Linguist. 79, 18–27. doi: 10.7176/JLLL/81-07

Ashoori Tootkaboni, A. (2019). Teachers' beliefs and practices towards communicative language teaching in the expanding circle. Rev. Signos 52, 265–289. doi: 10.4067/S0718-09342019000200265

Atkinson, J. S. (2002). Four steps to analyze data from a case study method. ACIS 2002 proceedings. Available online at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2002/38

Aweke, S. (2016). Teacher as a key role player to induce quality education: challenges and prospects of primary schools in Addis Ababa. Paper presented at the 4th Annual Educational Research Symposium of Addis Ababa City Government Education Bureau. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581560.pdf

Berns, M., and Matsuda, A. (2020). “Lingua franca and language of wider communication” in The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. ed. C. A. Chapelle. 2nd ed (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley).

Bedilu, A., and Degefu, M. (2025). Challenges in implementing communicative English teaching in Ethiopian primary schools. Ethiop. j. educ. sci., 12, 45–63.

Brock-Utne, B. (2010). Language and education in Africa: a comparative and transdisciplinary analysis. Dar es Salaam: Symposium Books.

Brovchak, L., Starovoit, L., Likhitska, L., Todosiienko, N., and Shvets, I. (2024). Integrating music, drama and visual arts in extracurricular programs: enhancing psychological development in early school-aged children. Sapienza Int. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 5:Article e24052. doi: 10.51798/sijis.v5i3.791

Busa, J., and Chung, S. J. (2024). The effects of teacher-centered and student-centered approaches in TOEIC reading instruction. Educ. Sci. 14:181. doi: 10.3390/educsci14020181

Cameron, L. (2010). Teaching languages to young learners. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Copland, F., and Garton, S. (2024). Young learners and language learning: bridging experiences and language development. Early Childhood Language Education 29, 33–50.

Copland, F., Garton, S., and Burns, A. (2014). Challenges in teaching English to young learners: global perspectives and local realities. TESOL Q. 48, 738–762. doi: 10.1002/tesq.148

Delibegović, N., and Pejić, A. (2016). The effect of using songs on young learners and their motivation for learning English. NETSOL New Trends Soc. Liberal Sci. 1, 40–54. doi: 10.24819/netsol2016.8

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2012). Language teaching research and language pedagogy. Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell.

Fusch, P., Fusch, G. E., and Ness, L. R. (2018). Denzin’s paradigm shift: revisiting triangulation in qualitative research. J. Soc. Change 10, 19–32. doi: 10.5590/JOSC.2018.10.1.02

Garton, S., Copland, F., and Burns, A. (2011). Investigating global practices in teaching English to young learners. London, United Kingdom: British Council.

Hu, R. (2016). The age factor in second language learning. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 6, 2164–2168. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0611.13

Husanović, D. (2022). The effectiveness of total physical response method in the process of learning and teaching English vocabulary to pre-adolescent learners in an online teaching setting. Netsol New Trends Soc. Liberal Sci. 7, 1–48. doi: 10.24819/netsol2022.08

Johnstone, A. (2022). An inquiry into teachers’ implementation of play-based learning aligned approaches within senior primary classes. Kairaranga 23, 17–34. doi: 10.54322/kairaranga.v23i1.331

Jusslin, S., Korpinen, K., Lilja, N., Martin, R., Lehtinen-Schnabel, J., and Anttila, E. (2022). Embodied learning and teaching approaches in language education: a mixed studies review. Educ. Res. Rev. 37:100480. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100480

Kang, J. (2017). Get up and sing! Get up and move! Using songs and movement with young learners of English. Engl. Teach. Forum 55, 14–25.

Kassa, S., and Abebe, D. (2023). The use of English as medium of instruction and students’ readiness to learn in English. Bahir Dar J. Educ. 22, 1–19. doi: 10.4314/bdje.v22i1

Littlewood, W. (2007a). Communicative and task-based language teaching in east Asian classrooms. Lang. Teach. 40, 243–259. doi: 10.1017/S0261444807004363

Littlewood, W. (2007b). Communicative language teaching: an introduction. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Lopez-Caudana, E., Ponce, P., Mazon, N., and Baltazar, G. (2022). Improving the attention span of elementary school children for physical education through a NAO robotics platform in developed countries. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. (IJIDeM) 16, 657–675. doi: 10.1007/s12008-022-00851-y

McCloskey, M. L., Orr, J., and Dolitsky, M. (2006). Teaching English as a foreign language in primary school (Case Studies in TESOL Practice Series). Alexandria, Virginia, USA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc.

Mebratu, M. (2015). The status, roles, and challenges of teaching English in Ethiopia: the case of selected primary and secondary schools in Hawassa University Technology Village area. Int. J. Sociol. Educ. 4, 182–196. doi: 10.17583/rise.2015.1515

Mekonnen, S., and Roba, A. (2017). Students’ perceptions of challenges in learning English in Adama town high schools. J. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 26–40.

Mijena, D. (2014). Teachers’ preparedness and classroom practices in Ethiopian primary schools. Addis Ababa University. (Unpublished Master’s Thesis).

Ministry of Education (2009). Curriculum framework for Ethiopian education (KG – Grade 12). Addis Ababa.

Ministry of Education. (2018). Education Statistics Annual Abstract 2017/18. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2022). Education Sector Development Programme VI (ESDP VI): 2020/21–2024/25. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Education.

Mundelsee, L., and Jurkowski, S. (2021). Think and pair before share: effects of collaboration on students' in-class participation. Learn. Individ. Differ. 88:102015. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102015

Muthukrishnan, P., Fung Lan, L., Anandhan, H., and Swamy, D. P. (2024). The role of growth mindset on the relationships between students’ perceptions of English language teachers’ feedback and their ESL learning performance. Educ. Sci. 14:1073. doi: 10.3390/educsci14101073

Narkabilova, G., and Davidova, P. (2022). The role of visual teaching aids in the formation of educational activities of younger students. Eur. Int. J. Multidis. Res. Manag. Stud. 2, 116–121. doi: 10.55640/eijmrms-02-11-28

Nguyen, T. (2024). Translation in language teaching: the need for redefinition of translation. AsiaCALL Online J. 15, 19–33. doi: 10.54855/acoj.241512

Paudel, P. (2020). Teaching English in multilingual contexts: teachers’ perspectives. Prithvi Acad. J. 3, 33–46. doi: 10.3126/paj.v3i0.29557

Pinter, A. (2006). Teaching young language learners. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Richards, J. C., and Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Safeer, N., Hussain, I., Azhar, B., Shaikh, M., and Jakhrani, M. (2024). Challenges and strategies in teaching English in multilingual classrooms. J. Policy Res. 10, 312–317. doi: 10.61506/02.00348

Salmanova, S. (2025). Communicative approach in foreign language teaching: advantages and limitations. EuroGlobal J. Linguist. Lang. Educ. 2, 79–88. doi: 10.69760/egjlle.250009

Shin, J. K. (2006). Teaching English to young learners. Alexandria, Virginia, USA: TESOL International Association.

Slatterly, M., and Willis, J. (2001). English for primary teachers. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Sun, J., Anderson, R. C., Lin, T.-J., Morris, J. A., Miller, B. W., Ma, S., et al. (2022). Children’s engagement during collaborative learning and direct instruction through the lens of participant structure. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 69:102061. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102061

Tadesse, E. (2022). Teachers’ challenges in implementing communicative approaches in Ethiopian schools. Ethiop. j. educ. sci., 18, 77–95.

Vijayaratnam, P., Khanum Akhi, M., Mohiuddin, M. G., Ali, Z. B., Manoochehrzadeh, M., and Rajanthran, S. K. (2025). The impact of watching English cartoons on preschoolers’ language acquisition and behavioral development in Dhaka. Forum Linguist. Stud. 7, 626–639. doi: 10.30564/fls.v7i1.6819

Xie, R. (2021). The effectiveness of total physical response (TPR) on teaching English to young learners. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 12:293. doi: 10.17507/jltr.1202.11

Ye, X. (2024). A review of classroom environment on student engagement in English as a foreign language learning. Front. Educ. 9:1415829. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1415829

Keywords: classroom practice, education, education quality, language teaching, young learners

Citation: Taddese ET, Yassin HA, Dinsa MT and Lakew AK (2025) The practices and challenges of teaching English to young learners: a case of selected primary schools in Ethiopia. Front. Educ. 10:1656387. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1656387

Edited by:

Rita Inderawati, Universitas Sriwijaya Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Morshed Al-Jaro, Seiyun University, YemenYahya Ameen Tayeb, Hodeidah University, Yemen