- Department of Applied Educational Science, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden

Standardized admission tests such as the Swedish Scholastic Aptitude Test (SweSAT) aim to ensure fairness in higher education selection by assessing verbal and quantitative skills. Previous research on the SweSAT indicates declining scores in the Swedish Reading subtest and improved scores in the English reading subtest. Gender differences are present, with males outperforming females on most SweSAT subtests–males often perform better on the multiple-choice format used in SweSAT, especially in English as a foreign language, while females typically perform better in school. Informal English exposure through Extramural English (EE) activities, such as digital gaming and reading, is associated with higher English proficiency, with males engaging more in gaming. However, EE impact on first-language proficiency alongside gender-related differences in test performance remains unclear. This study investigates how EE activities and item format contribute to gender-related performance differences in the SweSAT verbal subtests. A total of 5,230 SweSAT test-takers completed a questionnaire on their engagement in EE activities, focusing on reading and gaming. The SweSAT verbal items were examined using Mantel-Haenszel (MH) Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analyses to identify gender- and EE-related item biases. Results showed that gamers were more likely to be favored on English reading comprehension items, whereas non-gamers were favored on Swedish subtests. English items displayed DIF favoring frequent readers, whereas low-frequency readers were favored on some Swedish items. Male-favored DIF appeared mainly on English items, and females were favored on Swedish items. No consistent DIF patterns were linked to item format or word class across verbal items.

Introduction

Standardized admission tests are widely employed worldwide to promote equal academic opportunities and ensure fairness in selecting all applicants for higher education. In Sweden, the Swedish Scholastic Aptitude Test (SweSAT) plays a pivotal role in higher education admission, serving as an alternative to upper secondary school grades (Lyrén and Wikström, 2020; Stage and Ögren, 2004). The SweSAT includes quantitative and verbal subtests, with the latter assessing proficiency in English as a foreign language (L2) through an English comprehension test, and Swedish as the first language (L1) through vocabulary, reading comprehension, and sentence completion tests. The present study focuses on gender differences in the verbal subtests, and the engagement in gaming and reading in English during leisure time.

Background

Between 2012 and 2018, SweSAT data showed that Swedish reading comprehension and English reading comprehension followed opposite trends, with a decline in Swedish performance and improved English. Both males and females showed a similar decrease in Swedish reading comprehension and an increase in English reading comprehension, although males scored slightly higher than females (Löwenadler, 2022). These opposing trajectories raise concerns about underlying factors, including whether increased exposure to informal English-language activities, often called Extramural English (EE) activities, might contribute to this pattern. Although extensive research links EE to improved English language proficiency (Sundqvist, 2009; Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015; Warnby, 2022), less is known about its potential impact on first-language proficiency.

Fairness and validity are key roles in this assessment given the SweSAT's relevance in determining access to higher education. Validity refers to the degree to which empirical evidence and theoretical frameworks support the adequacy of a measurement (Messick, 1989). Fairness, closely related to validity, involves ensuring equitable conditions in the development and administration of tests for all test-takers. Fairness may be questioned in a test like SweSAT when certain groups obtain higher scores. To investigate the presence of unfair group differences, Differential Item Functioning (DIF) can be used. DIF occurs when individuals from different groups (e.g., gender, age) with the same underlying ability have different probabilities of answering an item correctly (AERA et al., 2014).

Continuing with validity and fairness, the test format has been suggested as a contributing factor to gender differences in performance. Research across different countries, including Sweden, indicates that males generally perform better on multiple-choice items, while females tend to perform better on constructed-response or open-ended questions (Reardon et al., 2018; Wikström and Wikström, 2017; Riukula, 2023). Given that the SweSAT relies entirely on multiple-choice questions, male test-takers may be favored and have different test-taking strategies than females (Stenlund et al., 2016). Females were more likely to keep track of time and skip questions, whereas males tended to focus on identifying correct answers, potentially reflecting greater risk-taking behavior among males. These differences in behavior, rather than ability, may partly account for observed performance gaps.

In Sweden, moderate DIF has been found in the SweSAT's language assessment between 2011 and 2013. In Swedish verbal subtests, items often favored females, but items in English reading comprehension favored males (Wedman, 2017). While the content of the items seems to be a relevant issue, in which Swedish stereotypical female-related words favored them, males were favored in English reading comprehension, regardless of the content. Although designed to provide equal opportunity, standardized tests might reflect gender-related preferences in using first and foreign languages. Gender differences were also investigated in this college admission test between 2014 and 2023. In the SweSAT, verbal items identified as exhibiting DIF mostly favored females in the Swedish subtests. At the same time, males were more often favored in the English reading comprehension subtest, particularly in sentence completion items (Wedman and Laukaityte, 2025).

Moreover, studies like those by Fischer et al. (2013) and Karlsson and Wikström (2021) report that standardized admission tests, including the SweSAT, tend to underpredict female academic performance and overpredict male performance, even when controlling for achievement levels. While the effect sizes are small, they highlight the importance of considering item content and factors such as test design, motivation, and effort (Graetz and Karimi, 2022). Females often outperform males in upper secondary school grade point average (GPA), but this advantage is not carried over to standardized multiple-choice contexts such as the SweSAT.

Research in a Korean context also analyzed how item-level bias can contribute to test performance. Pae (2012) analyzed gender-related DIF in the English section of the Korean Scholastic Aptitude Test over several years. Specifically, a higher percentage of fill-in-the-blank items, items assessing contextual meaning, and those involving graphs, grammar, and vocabulary favored males over females. Additionally, a strong link exists between gender differences in how examinees perceive the appeal of test items and the extent of gender-games DIF.

To understand the gender-related differences in language performance, consideration of the environment in which language learning occurs is essential. Language learning occurs in both formal and informal settings, and informal learning has gained increased attention from researchers, particularly in the context of foreign language learning (Alonso, 2023; Sundqvist, 2009; De Wilde et al., 2020; Sylvén and Löwenadler, 2023; Warnby, 2022). While formal learning is established by guidelines and graded following a criterion, informal learning is often unintentional per se (Krashen, 1976). It does not follow a given structure, which is an obstacle to explaining the outcomes and how that is transferred to formal learning. Livingstone (2006, p. 206) defined informal learning as “any activity involving the pursuit of understanding, knowledge, or skill that occurs without the presence of externally imposed curricular criteria.” In addition to learning the first language, several authors have investigated the impact of out-of-school exposure to a foreign language, such as English, known as EE. EE is a term consistently used in previous research concerning informal learning (Kusyk et al., 2025). It refers to the engagement in English-language activities in informal contexts, typically without the intention to learn the language. A teacher does not initiate this type of learning, but by the learner themselves, or through friends or relatives (Sundqvist and Sylvén, 2016). EE is often assessed through several dimensions, including gaming, digital creativity, niche activities, internalization of English, viewing, social interaction, music, and reading and listening (Sundqvist and Uztosun, 2024). Nevertheless, previous research found that reading and digital gaming were more strongly associated with English reading comprehension than the other EE activities (Neagu et al., 2025). Therefore, the present study examines how the engagement in EE-related gaming and EE reading activities influences performance on the verbal subtest of the SweSAT. By comparing the performance of male and female participants involved in these EE activities, we aim to identify possible gender-based DIF and investigate how these activities may contribute to the performance in the different groups.

Digital gaming is one of the most popular EE activities among young people as it is widely accessible and facilitates interaction with others (Swedish Media Council, 2023; Sylvén and Sundqvist, 2012). Hanghøj et al. (2022) referred to digital games as any game that takes place on an electronic device and consists of aims, rules, and outcomes (Plass et al., 2015). In Sweden, 9 out of 10 children between 8 and 19 years old play digital games, without differences between males and females (Swedish Internet Foundation, 2023). However, gaming frequency differs, with males playing more than females. This variation has been linked to differences in English vocabulary tests scores (Sundqvist, 2019; Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015). Outside Sweden, findings have been mixed. Muñoz and Cadierno (2021) found that frequent gaming correlated positively with English proficiency among Danish students, while De Wilde et al. (2020) reported similar findings among Dutch students. Additionally, Tran and Miralpeix (2024) reported a negative correlation in the Spanish context. Calafato and Clausen (2024) studied this issue in Norway with students in secondary education, finding that gaming frequency did not correlate with vocabulary knowledge. It is unclear, and causality has not yet been found (Kusyk et al., 2025). However, most research suggests that gaming tends to relate to positive academic performance in English tests, leading researchers to consider whether gamers learn differently than students who do not engage in this EE activity.

Reading, another EE activity, has consistently been associated with positive academic outcomes in English proficiency. Tran and Miralpeix (2024) found that reading positively correlated with English grades in Spanish secondary students. Meyer et al. (2024), using longitudinal data from German students in grades 11 and 13, found that frequent reading during leisure time led to improved English reading comprehension. Additionally, students who spent more time engaging in reading showed more motivation in learning English as well. In Sweden, Warnby (2022) found that while Swedish students are exposed daily to EE activities, reading and gaming were both positively correlated with English academic vocabulary knowledge. Additionally, both reading and gaming were more popular among males than females, especially gaming. This could suggest that males learn more academic English vocabulary and achieve higher scores than females due to being more exposed to digital games.

Despite the extensive research on EE and foreign language learning, few studies have addressed whether exposure to EE activities can be associated with L1 proficiency or test performance. A study by Sigurjónsdóttir and Nowenstein (2021) examined whether learning English as a foreign language can reduce the exposure and acquisition of Icelandic as a first language in children between 3 and 12 years old. Results showed that the influence of English on the Icelandic language was minimal in grammar and vocabulary, as reflected in the scores. This was attributed to limited exposure to English, although its use increases with age.

The assumption that prolonged exposure to EE activities could interfere with first-language proficiency is inconclusive. Haman et al. (2017), for example, found that while reduced L1 production at home due to greater L2 (English) use could impact L1 outcomes, L1 comprehension remained unaffected. This suggests that EE activities may not directly impact performance in Swedish verbal subtests on the SweSAT, especially since comprehension and production are distinct cognitive processes (Clifton et al., 2013). However, this study did not account for gender-related differences, leaving open questions about how exposure to EE activities may relate to differences between male and female test-takers in their Swedish L1 and English L2 languages.

Research gap, purpose, and research questions

Over the last 20 years, research in informal language learning has primarily focused on English acquisition as a foreign language due to exposure to EE activities (Kusyk et al., 2025). However, research lacks findings on how such exposure might influence performance in standardized college admission tests assessing L1 besides English. Interestingly, while English reading comprehension scores on the SweSAT have increased over the past decade, Swedish reading comprehension scores have consistently declined (Löwenadler, 2022), leaving the door open to investigate the possible factors of these changes. While existing research has investigated the role of EE in foreign language acquisition, its relationship to L1 and its potential influence on gender differences in standardized assessments such as the SweSAT remains unexplored. These considerations highlight the importance of studying how informal language learning and item format may contribute to observed differences in male and female test outcomes. Therefore, the present study investigates the presence of DIF in the verbal section of the SweSAT, focusing on EE variables (digital gaming and reading) and gender-related differences. The verbal section includes three subtests assessing Swedish language knowledge and one assessing English proficiency. The goal is to examine how these EE activities interact with test performance in both Swedish and English, and whether males and females perform differently in the SweSAT verbal section. The research questions addressed are:

1. How does verbal performance differ by sex and frequency of exposure to EE activities?

2. To what extent do EE activities, gender, and their interaction contribute to DIF in the SweSAT verbal items, including L2 English and L1 Swedish subtests?

3. How might detecting of DIF related to EE activities help to understand gender differences in performance on the SweSAT verbal subtests?

Methods

Participants and procedure

The SweSAT test-takers (n = 32,097) were approached to complete our questionnaire in May of 2023, shortly after the test administration. They received an email describing the study and its purpose, as well as a link to a voluntary questionnaire estimated to take 10 min to complete. Only first-time test-takers were approached to avoid the effects of previous exposure to the SweSAT (Cliffordson, 2004). A total of 6,079 participants responded to the questionnaire. The sample used in this study consisted of 5,230 participants who reported Swedish as their first language, of whom 56% were females. The age groups in the SweSAT database are divided into five categories: ≤ 20, 21–24, 25–29, 30–39, and ≥40. The youngest age category (20 years old or younger) represented 77% of the sample. Information on age groups division was retrieved from the SweSAT database and has not been altered.

We used a non-probability purposive sampling method, deliberately targeting first-time test takers. Self-selected participants later showed higher scores across all verbal subtests, indicating an overrepresentation of this group, which may limit the generalizability of the results to the SweSAT population from the spring 2023 administration (N = 61,148) (Galloway, 2005).

Ethical consideration

The data were stored and handled anonymously in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Participants were invited via email, informed about the purpose of the study, and participated voluntarily with the right to withdraw their data at any time.

EE activities assessment

EE activities was assessed using a questionnaire administered via SurveyandReport (Artologik, 2023) which is a standard method used in previous studies measuring exposure to these activities (Kusyk et al., 2025; Sundqvist, 2024). The questionnaire comprised 21 questions designed to assess exposure to and use of EE; one of the items collects information about reading frequency and two items about gaming exposure explained below.

Previous research has shown that, among the different EE activities, reading and gaming showed the strongest association with English reading comprehension performance in the SweSAT (Neagu et al., 2025), these two variables were selected for further analyses in the current study. First, Reading was defined for the participants as how often they read books, newspapers, etc. in English. The option responses were represented on a 5-point Likert scale: 5 = Daily, 4 = Once or a few times per week, 3 = Once or a few times per month, 2 = Once or a few times per year, and 1 = Less often than once per year or never. In the dataset, low frequent readers were classified as 0 if they chose option 1, 2, or 3, and frequent readers as 1 if they chose option 4 or 5. Previous research has shown a similar classification based on books and magazines in Swedish (Sörman et al., 2018).

Secondly, we examined digital gaming-related variables. Several researchers have studied the impact of gaming, as it is one of the most common leisure activities (Calafato and Clausen, 2024; Sylvén and Sundqvist, 2012; Sundqvist, 2019). However, these studies often do not establish what it means to be a gamer. Shaw (2012) attempted to define gamer as an identity but did not address behavior or frequency. In this study, we distinguish between two variables:

• Gamer: participants were asked whether they regularly play digital games, i.e., computer, console and/or mobile games (online or offline; single-player or multiplayer). Those who answered yes (1) were considered gamers, and those who answered no (0) were considered non-gamers.

• Gamer based on frequency: participants were asked how many hours, approximately, they play digital games in English during a typical week. Reported hours varied from 0 to 120 weekly hours. All participants were then classified into two categories: 0 (low-frequent gamers) if reported hours were ≤ 5, and 1 (frequent gamers) if reported hours were > 5. Previous research classified gaming frequency into low, moderate, and frequent groups (Sundqvist, 2013, 2019). However, Neagu et al. (2025) found no significant difference between moderate and frequent gamers on any outcome variable, and the two categories were deemed sufficient.

• Additionally, the Sex variable was used to investigate differences between males and females, coded as 1 and 2, respectively. The data was retrieved from the national identification number, which reflects the sex assigned at birth. However, we will refer to it as gender throughout the study.

Verbal assessment

The SweSAT aims to measure scholastic proficiency and is used for selection to higher education in Sweden. It consists of one quantitative and one verbal section comprising four subtests with 80 dichotomously scored multiple-choice questions each. The subtests target mathematical problem-solving (XYZ), quantitative comparisons (QC), data sufficiency (DS), diagrams, tables, and maps (DTM), vocabulary (WORD), Swedish reading comprehension (READ), sentence completion (SEC), and English reading comprehension (ERC) (Wedman, 2017).

This study focused on the verbal section, which consists of four subtests (i.e., WORD, SEC, READ, ERC) with 20 items each (Stage and Ögren, 2004, 2010). The internal consistency of the 2023 SweSAT administration showed excellent reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha of α = 0.92.

The WORD subtest (Items 1–10; 41–50) assesses the understanding of concepts with Swedish or foreign origin. The options presented in each item are either a synonym or a hyponym. The READ (Items 11–20; 51–60) subtest assesses test-takers' Swedish reading comprehension using short and long texts that reflect the level they will encounter at the university level (Stage and Ögren, 2004). The SEC (Items 21–30; 61–70) subtest consists of items with one to three words in each response option and aims to evaluate test-takers' ability to fit words into a context (Stage and Ögren, 2010). The ERC (Items 31–40; 71–80) subtest includes five sentence-completion items; the remaining items involve interpreting short texts, long texts, or both. Test-takers are expected to identify the relevant information in the text rather than isolated details (Stage and Ögren, 2004).

Data analysis

The analysis begins with the computation of mean scores for each verbal subtest in the SweSAT, separated by males and females and their corresponding EE activity subgroups, to provide descriptive data and give an overview of the group differences. Effect sizes of the mean differences between the EE activities subgroups among males and females were calculated using Cohen's d, considering 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 as small, medium, and large effects, respectively (Cohen, 1988, 1992).

To further analyze any group differences, we conducted DIF analyses using the Mantel-Haenszel method (MH; Mantel and Haenszel, 1959), as the main analysis of this study. MH is widely used for DIF detection due to its simplicity and effectiveness in detecting uniform DIF. Uniform DIF refers to a constant advantage or disadvantage for a one group over the other across all ability levels, whereas non-uniform DIF refers to a variation in the direction across the ability levels, for instance, one group may be favored at lower ability levels while the other group is favored at higher ability levels (Desjardins and Bulut, 2018). Chi-square statistic (χ2) is computed as well as the effect size, which categorizes the strength of the DIF, using ETS Delta classification. The effect size is classified by Holland and Thayer (1985) as follows

• A: |ΔMH | ≤ 1, negligible DIF

• B: 1 < |ΔMH | ≤ 1.5, moderate DIF

• C: |ΔMH | > 1.5, large DIF.

While MH only detects uniform DIF, Chen et al.'s (2024) systematic review showed that MH is commonly used when conducting DIF in language assessments. Additionally, SweSAT data showed a lack of non-uniform DIF (Wedman, 2017), making MH a suitable approach for this study.

DIF analysis was performed in R, version 4.4.1 (R Core Team, 2024), using difR (Magis et al., 2010) packages with a set default significance level α = 0.05. To compute descriptive statistics, we used cat (R Core Team, 2024), stats (R Core Team, 2024) for mean differences using t-test, and psych (Revelle, 2025) package to calculate Cohen's d values. Plots were created with ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

Omitted questionnaire responses were present in this sample. Specifically, two responses were missing for the item on reading frequency in English, and 26 responses were missing for the item on gaming frequency in English among participants who indicated that they play digital games. The omitted responses, coded as NA, were discarded when computing the MH DIF analysis.

Results

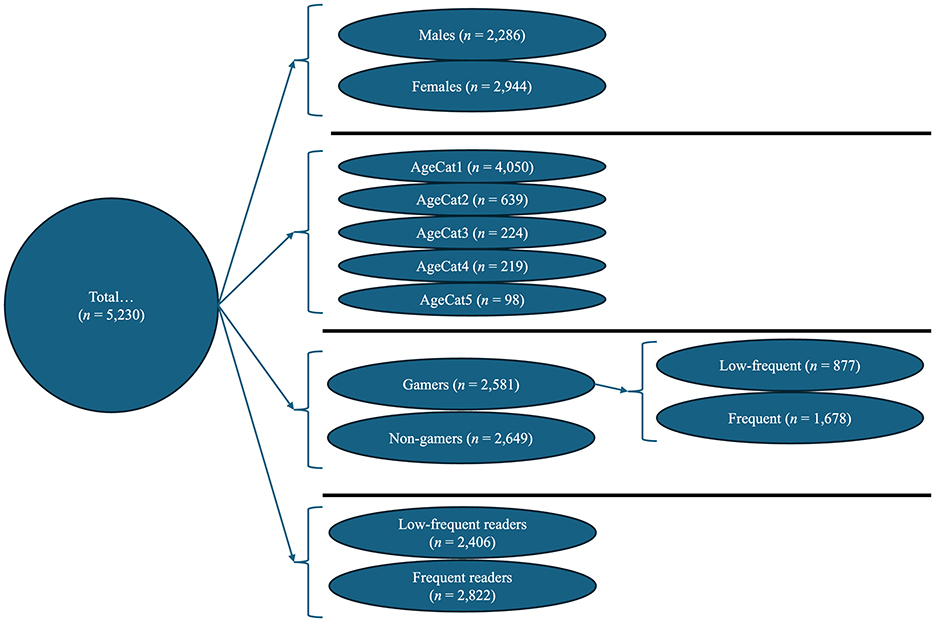

Among the total of 5,230 participants, 87% of non-gamers were females, whereas 69% of males were classified as gamers. Among the gamers, 53% of females were low-frequent gamers, while 80% of males were frequent gamers. Concerning reading habits, 28% of females were low-frequent readers, and 29% were frequent readers (see Figure 1). Moreover, the male and female SweSAT test-takers population in the spring of 2023 scored lower on average than the study participants across all subtests (see Table 1).

Figure 1. Sample distribution divided from the total participants into subgroups based on EE activities questionnaire responses. AgeCat 1–5 represent the age division in the SweSAT: ≤ 20, 21–24, 25–29, 30–39, and ≥40. Participants are also classified as non-gamers if they answered “No” and gamers if they answered “Yes” to play digital games. Those who reported playing digital games 5 or less hours per week were assigned to low-frequent gamers and to frequent gamers if they reported gaming more than 6 h per week. Reading frequency was divided in low-frequent readers if participants engaged in Extramural English (EE) Reading from never to once or a few times per month, and frequent readers if they engaged in EE Reading once or a few times per week, or daily. Lines indicate four different ways of dividing the total sample into subgroups.

Table 1. Average scores and standard deviations for each verbal subtest on the SweSAT separated by males and females and their corresponding EE activities subgroups.

The following results include average scores and standard deviations for different groups, which are represented in Table 2.

Table 2. t-test results comparing groups and subgroups among males and females and EE activities on SweSAT verbal subtests.

Performance of the verbal subtests among total participants (n = 5,320)

As shown in Table 1, the average scores and standard deviations for the verbal subtests (WORD, SEC, READ, ERC) are represented by gender, gaming, and reading frequency. Among all participants, males performed better on average than females in READ [d = 0.23, 95% CI (0.18, 0.29)], SEC [d = 0.17, 95% CI (0.11, 0.22)], and ERC [d = 0.61, 95% CI (0.56, 0.67)], but there were no significant gender differences in WORD.

Performance of the verbal subtests among male participants (n = 2,286)

In the male group, non-gamers scored higher on average in WORD [d = 0.34, 95% CI (0.24, 0.44)] and SEC [d = 0.36, 95% CI (0.26, 0.46)] compared to gamers, while gamers outperformed non-gamers in ERC [d = −0.26, 95% CI (−0.36, −0.16)]. A similar pattern was observed when comparing low-frequent gamers to frequent gamers among all participants: low-frequent gamers performed better in WORD [d = 0.21, 95% CI (0.10, 0.32)] and SEC [d = 0.22, 95% CI (0.11, 0.33)], whereas frequent gamers scored higher in ERC [d = −0.17, 95% CI (−0.29, −0.06)]. No significant group differences were found in the READ subtest. Frequent readers scored higher on average than low-frequent readers across all subtests [d = −0.19, 95% CI (−0.27, −0.11) in WORD; d = −0.28, 95% CI (−0.36, −0.19) in READ; d = −0.17 in SEC, 95% CI (−0.25, −0.09); d = −0.44 in ERC, 95% CI (−0.52, −0.36)].

Performance of the verbal subtests among female participants (n = 2,944)

In the female group, gamers scored higher in ERC [d = −0.32, 95% CI (−0.41, −0.24)] than non-gamers, and no significant difference found in the remaining subtests–WORD, READ, and SEC–between gamers and non-gamers. Frequent gamers also scored higher in ERC [d = −0.20, 95% CI (−0.34, −0.06)] than low-frequent gamers. No significant group differences were found in READ and SEC subtests, nor were there significant mean differences in WORD subtest between low-frequent and frequent gamers. Similarly to males, frequent readers females scored higher on average than low-frequent readers in all subtests [d = 0.16, 95% CI (−0.23, −0.09) in WORD; [d = 0.24, 95% CI (−0.32, −0.17) in READ; d = −0.12, 95% CI (−0.19, −0.04) in SEC; d = −0.53, 95% CI (−0.60, −0.46) in ERC].

DIF and performance analyses across gender and EE subgroups

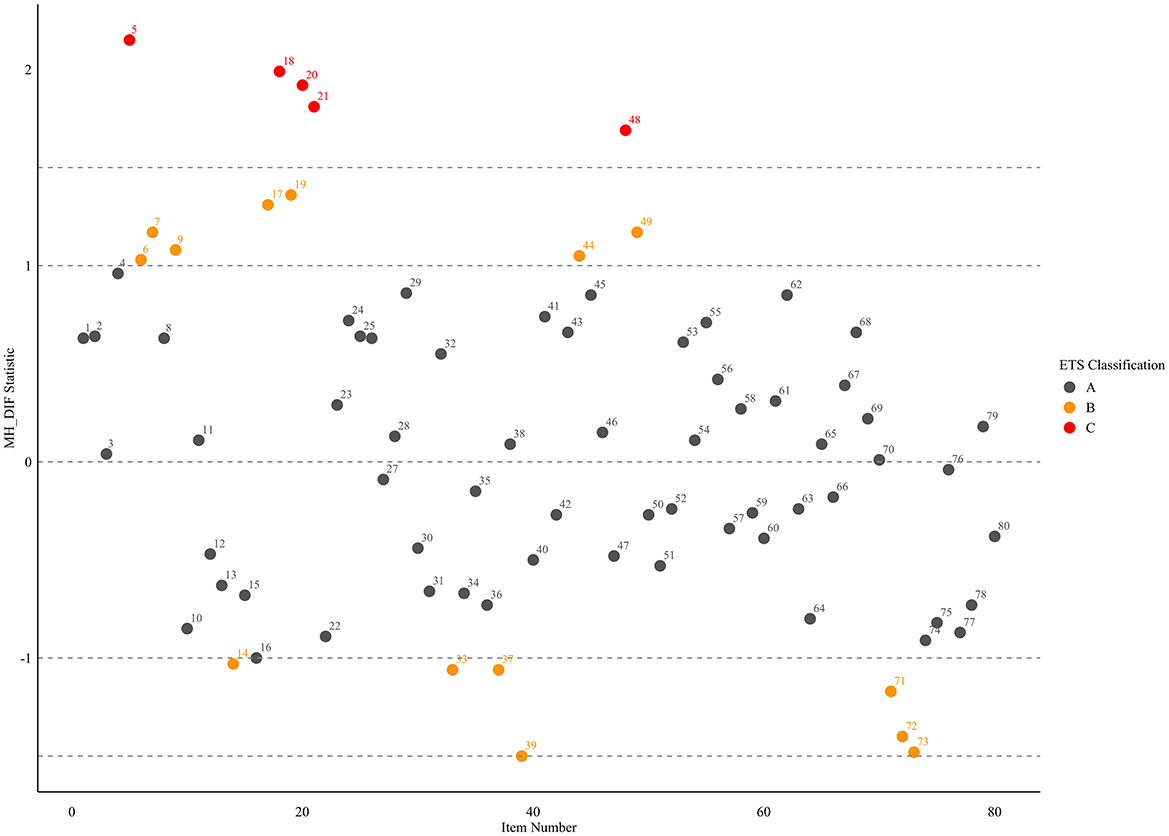

A MH analysis was conducted to examine whether the items functioned differently based on EE activities and gender. The ETS delta classification was used to interpret the magnitude of DIF, and only DIF items with moderate or large effect size are discussed below. DIF plots for each group comparison are also provided. The results are reported separately for different subgroups and for the total sample.

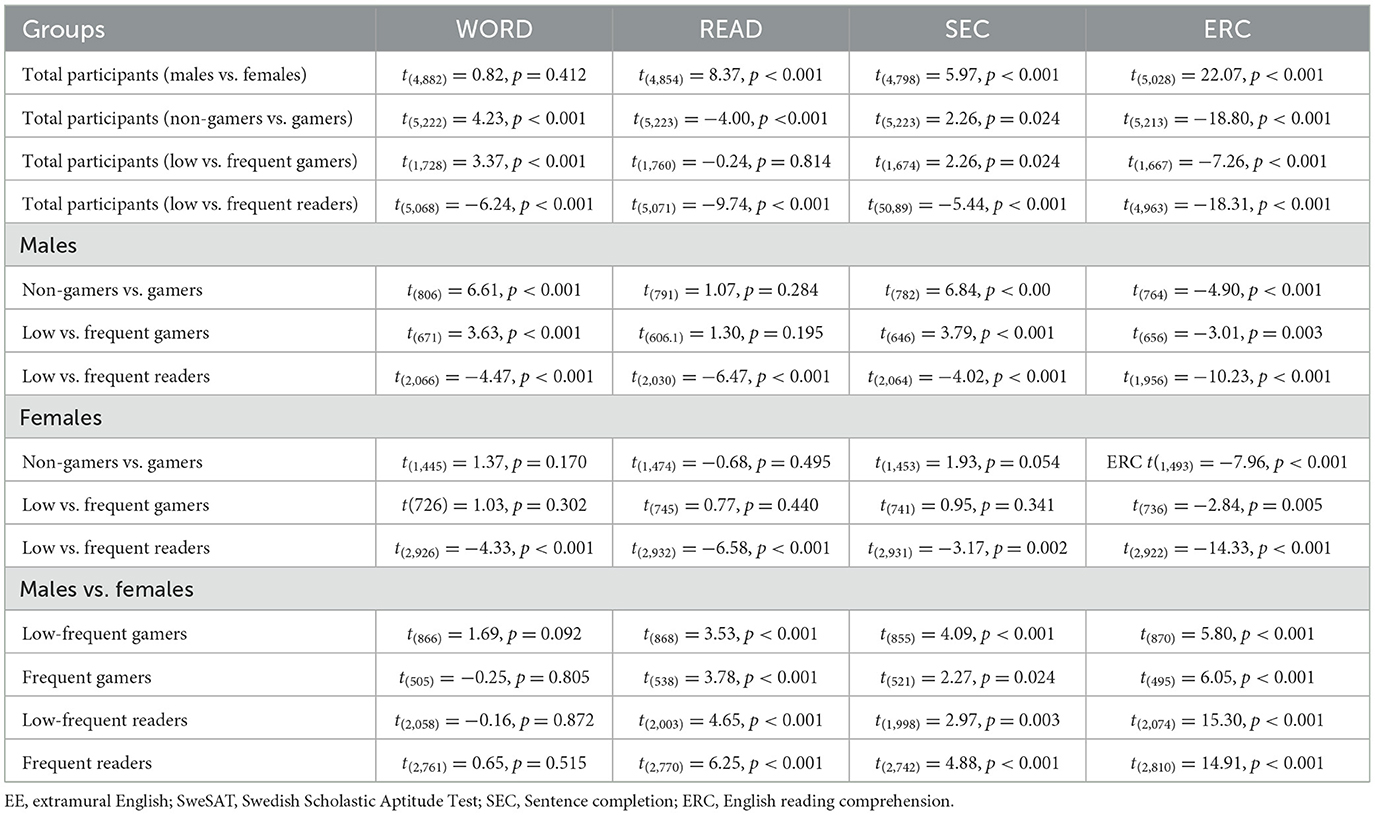

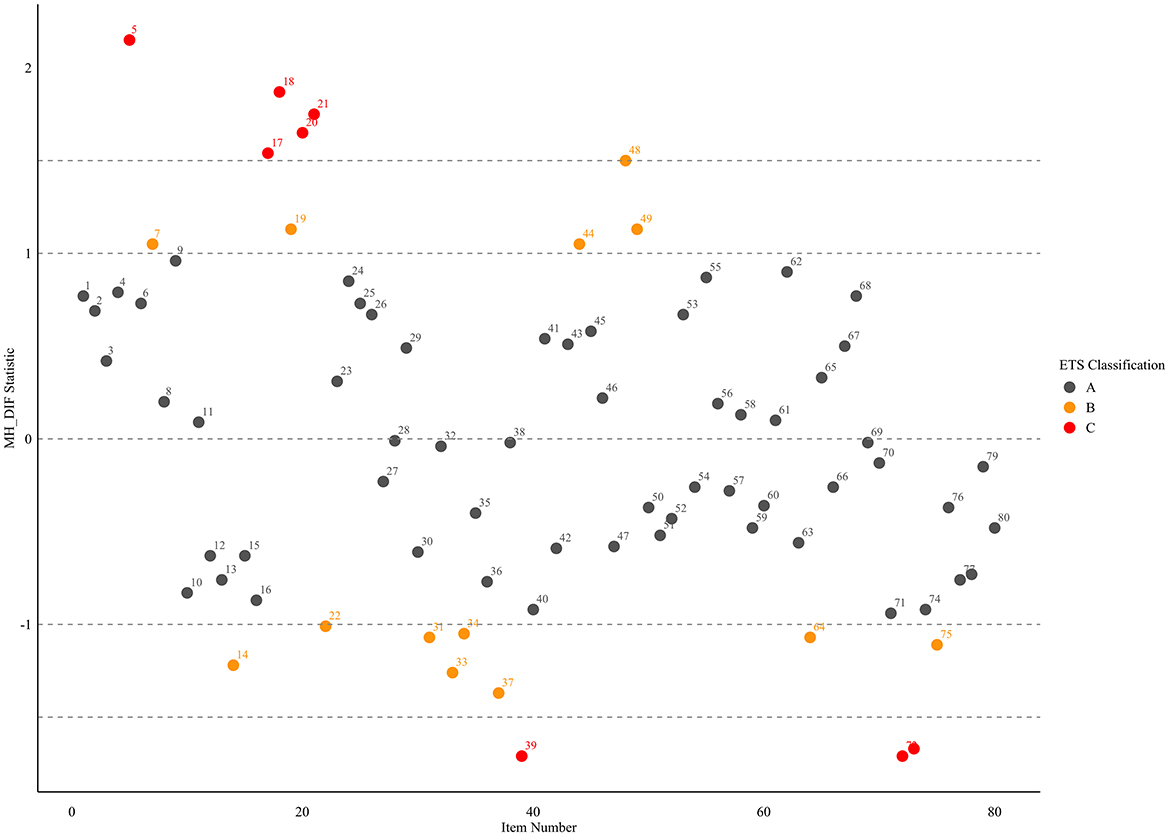

Comparison between gamers (n = 2,581) vs. non-gamers (n = 2,649)

When comparing gamers and non-gamers, with non-gamers as the focal group, several items in the WORD (1, 5, 7, 9, 41, 44, 46, 49), READ (55), and SEC (20, 21, 62, 67) subtests exhibited moderate to large DIF in favor of non-gamers, see Figure 2. In contrast, items favoring gamers appeared exclusively in the ERC subtest (37, 39, 40, 72, 73).

Figure 2. Mantel-Haenszel DIF plot comparing gamers and non-gamers across SweSAT verbal items with ETS delta classification. WORD items represented in 1–10; 41–50. READ items 11–20; 51–60; SEC items 61–70; 61–70. ERC items 31–40; 71–80. A = negligible DIF, B = moderate DIF, and C = large DIF.

The comparisons of effect sizes across the subtests indicated that non-gamers performed better than gamers in WORD [d = 0.12, 95% CI (0.06, 0.17)] and SEC [d = 0.06, 95% CI (0.01, 0.12)], while gamers outperformed non-gamers in READ [d = −0.11, 95% CI (−0.16, −0.06)] and ERC [d = −0.52, 95% CI (−0.57, −0.46)]. Gamers were more likely to answer correctly on items in the L2 English subtest, whereas non-gamers performed better on the L1 Swedish subtests.

Comparison between low-frequent gamers (n = 877) vs. frequent gamers (n = 1,678)

Few items exhibited DIF when comparing low-frequent gamers and frequent gamers in the total sample, and the effect sizes were negligible. Both groups were equally likely to answer the items correctly. Cohen's d values showed that low-frequent gamers scored higher on average than frequent gamers in WORD [d = 0.14, 95% CI (0.06, 0.22)] and slightly in SEC [d = 0.10, 95% CI (0.01, 0.18)] subtests, while frequent gamers scored higher than low-frequent gamers in the ERC [d = −0.31, 95% CI (−0.39, −0.23)] subtest. No significant group differences were found in the READ subtest.

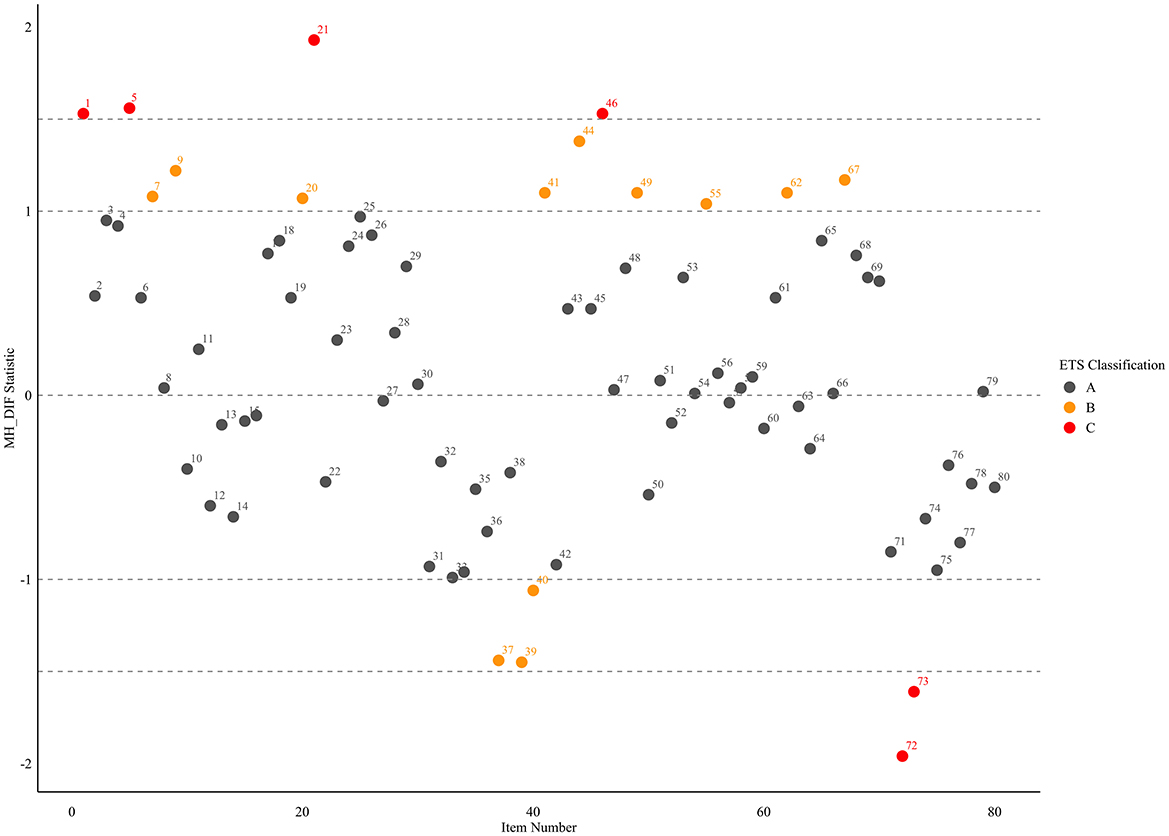

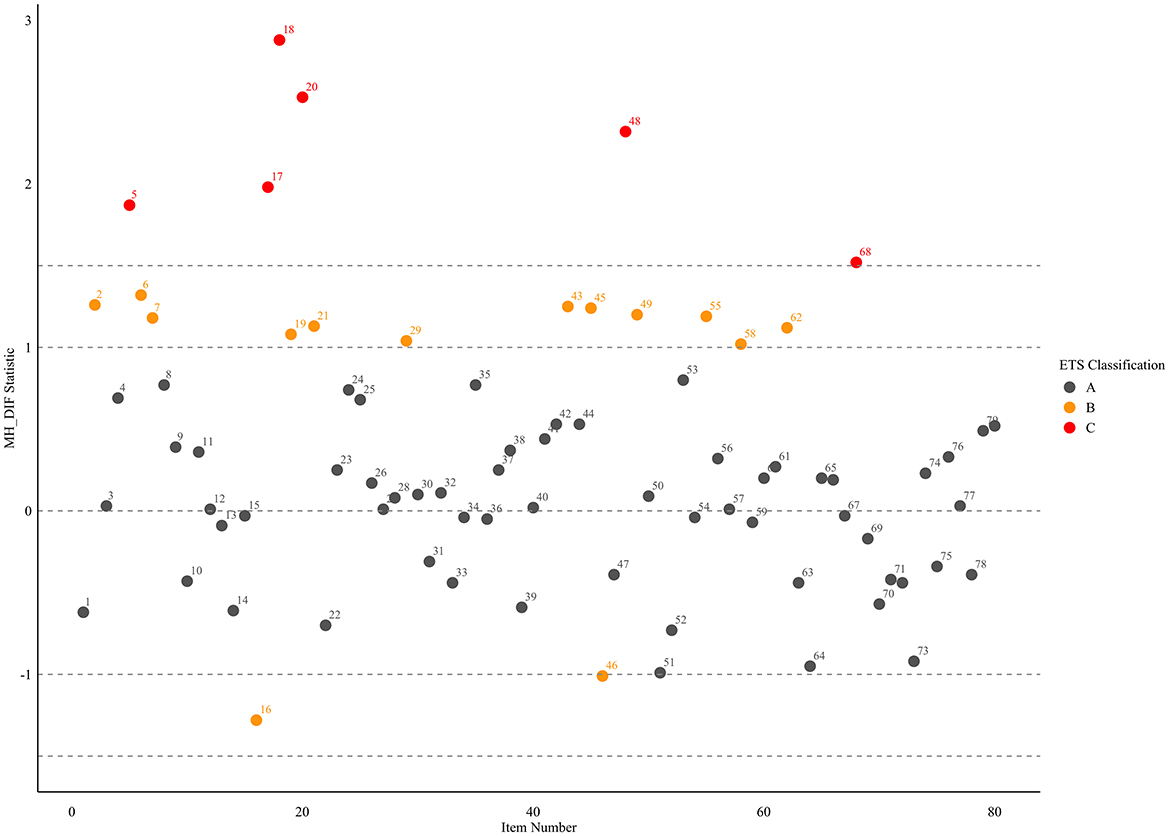

Comparison between low-frequent readers (n = 2,406) vs. frequent readers (n = 2,822)

When comparing low-frequent and frequent readers, with low-frequent readers as the focal group, a few items displayed DIF, including some with moderate effect sizes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Mantel-Haenszel DIF plot comparing low-frequent readers and frequent readers across SweSAT verbal items with ETS delta classification. WORD items represented in 1–10; 41–50. READ items 11–20; 51–60; SEC items 61–70; 61–70. ERC items 31–40; 71–80. A = negligible DIF, and B = moderate DIF.

Low-frequent readers showed an advantage on specific items from the WORD (9, 46) and SEC (21, 26) subtests, whereas frequent readers performed better on specific items from the WORD (42) and ERC (37, 40) subtests. Although the patterns are inconsistent, test-takers who read in English a few times per month or less were favored in items that assess L1 Swedish. In contrast, DIF observed in ERC items favored test-takers who read in English a few times per week or more. Results indicated that frequent readers outperformed low-frequent readers in WORD [d = −0.17, 95% CI (−0.23, −0.12)], READ [d = −0.27, 95% CI (−0.33, −0.22)], SEC (d = −0.15, 95% CI (−0.21, −0.10)], and ERC [d = −0.51, 95% CI (−0.57, 0.46)] subtests.

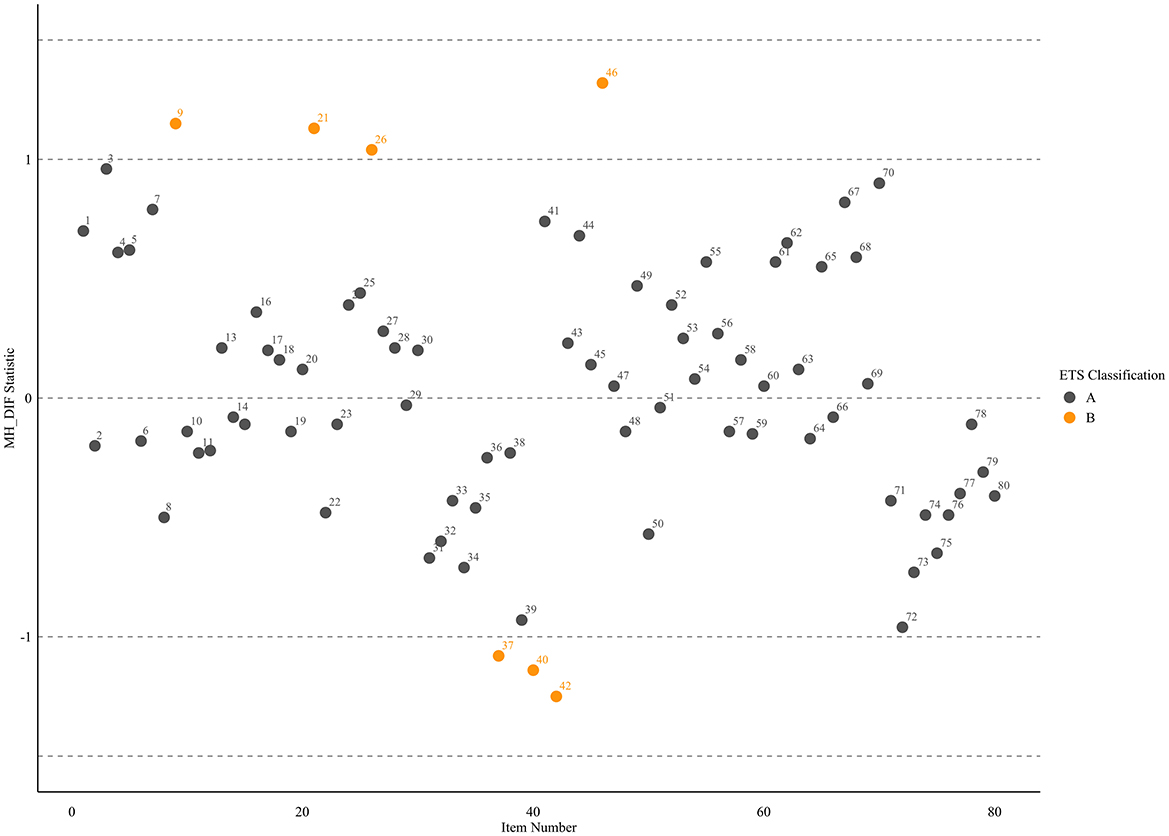

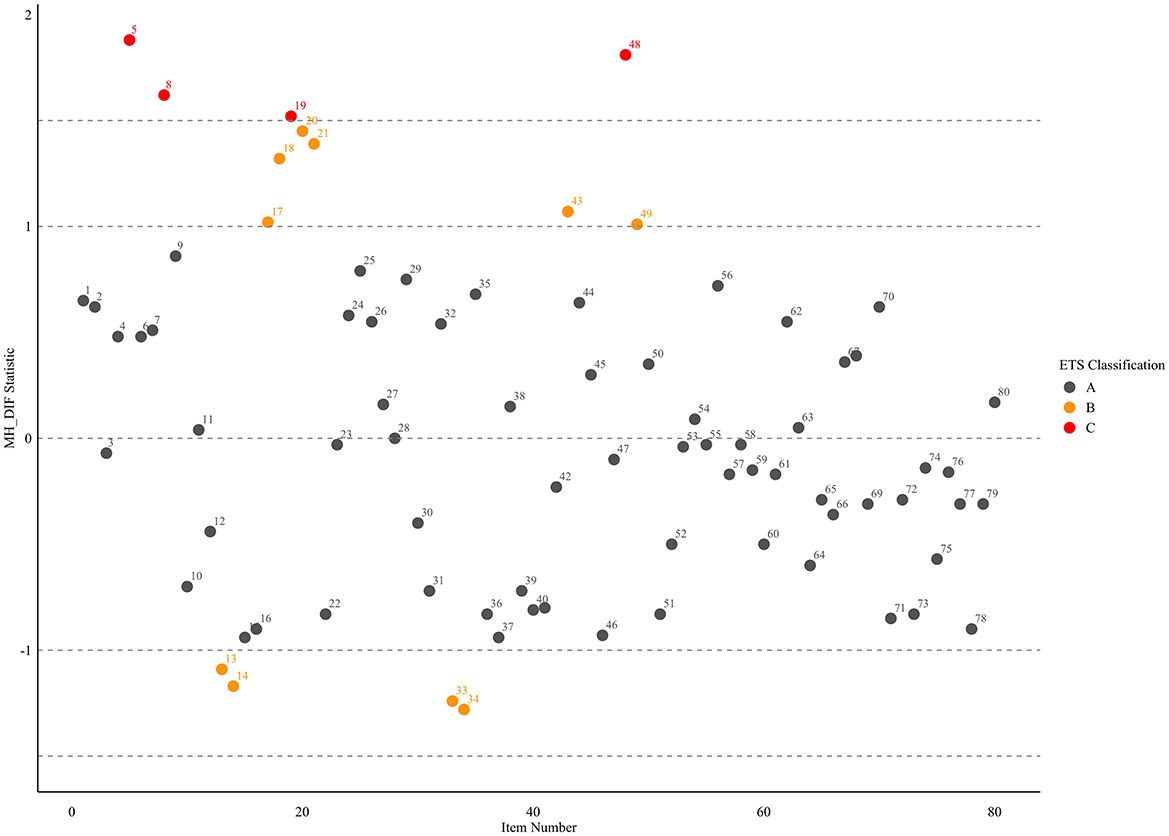

Comparison between males (n = 2,286) vs. females (n = 2,944)

Gender-based comparisons were also conducted, with females as the focal group. Several items were flagged showing moderate to large DIF, as illustrated in Figure 4. Males were favored on items from the READ (14), SEC (22, 64), and especially the ERC subtest (31, 33, 34, 37, 39, 72, 73, 75). In contrast, females have a performance advantage on items from the WORD (5, 7, 44, 48, 49), READ (17–20), and SEC (21) subtests. When examining the SweSAT population of test takers from spring 2023, the items that displayed DIF were generally consistent with those found in our sample. Males were favored in READ (14), SEC (22) and ERC (31, 33, 37, 39, 72, 73, 75), while females were favored on WORD (5, 8, 48, 49), READ (17–20), and SEC (21). However, items 7 and 44 (WORD) and 34 (ERC) only displayed DIF in the current sample.

Figure 4. Mantel-Haenszel DIF plot comparing males and females across SweSAT verbal items with ETS delta classification. WORD items represented in 1–10; 41–50. READ items 11–20; 51–60; SEC items 61–70; 61–70. ERC items 31–40; 71–80. A = negligible DIF, B = moderate DIF, and C = large DIF.

Gender comparison among low-frequent gamers (n = 877)

Within the gamer subsample, gender-related DIF, with females (n = 463) as the focal group, was analyzed. Among low-frequent gamers (see Figure 5), a greater number of items displayed DIF favoring females, particularly within the WORD (2, 5–7, 43, 45, 48, 49), READ (17–20, 55, 58), and SEC (21, 29, 62, 68) subtests. Only a few items favored males in this group (46 in WORD, 16 in READ). Despite the majority of items exhibiting DIF favoring females, effect sizes indicated that males scored higher on average than females across all subtests [d = 0.24, 95% CI (0.11, 0.37) in READ; d = 0.28, 95% CI (0.14, 0.41) in SEC; d = 0.39, 95% CI (0.26, 0.53) in ERC] except for WORD, where no significant group differences were observed.

Figure 5. Mantel-Haenszel DIF plot comparing low-frequent gamers males and females across SweSAT verbal items with ETS delta classification. WORD items represented in 1–10; 41–50. READ items 11–20; 51–60; SEC items 61–70; 61–70. ERC items 31–40; 71–80. A = negligible DIF, B = moderate DIF, and C = large DIF.

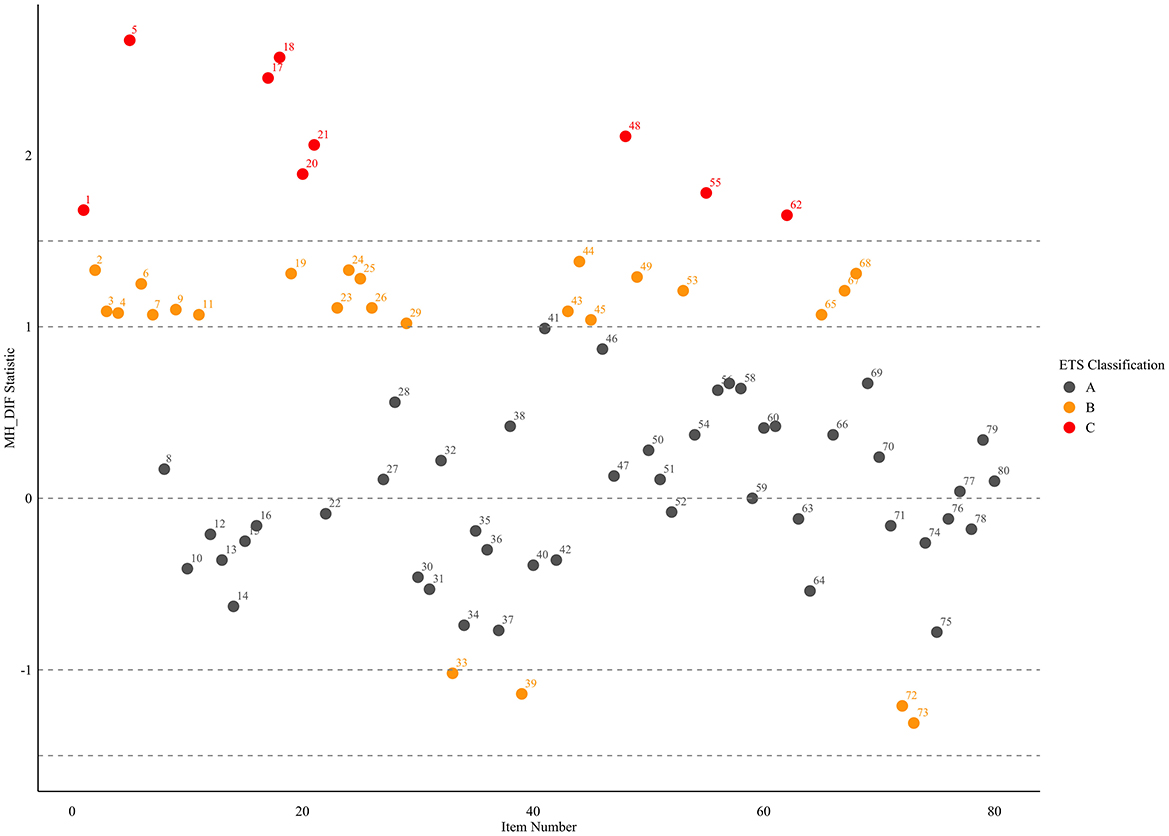

Gender comparison among frequent gamers (n = 1,678)

In the frequent gamers group (see Figure 6), fewer items displayed DIF overall. Items favoring males were primarily located in the READ (13, 14) and ERC (33, 34) subtests, while items favoring females (n = 333) appeared in WORD (5, 8, 43, 48, 49), READ (17–20), and SEC (21) subtests. Analysis of effect sizes showed that males scored higher on average than females in READ [d = 0.22, 95% CI (0.10, 0.34)], in SEC [d = 0.14, 95% CI (0.02, 0.26)], and in ERC [d = 0.38, 95% CI (0.26, 0.50)] subtests. No significant gender differences were observed in the WORD subtest.

Figure 6. Mantel-Haenszel DIF plot comparing frequent gamers males and females across SweSAT verbal items with ETS delta classification. WORD items represented in 1–10; 41–50. READ items 11–20; 51–60; SEC items 61–70; 61–70. ERC items 31–40; 71–80. A = negligible DIF, B = moderate DIF, and C = large DIF.

Females who reported playing 5 h or less per week were more likely to answer items assessing L1 Swedish correctly than those who reported playing more than 5 h per week. Male-favoring DIF items appear to be fewer, particularly among low-frequent gamers.

Gender comparison among low-frequent readers (n = 2,406)

In the low-frequent readers group, effect sizes across the subtests, when comparing males and (n = 1,445) females, showed d = 0.20, 95% CI (0.11, 0.28) in READ, d = 0.12, 95% CI (0.04, 0.21) in SEC, and d = 0.64, 95% CI (0.55, 0.72) in ERC, indicating that males performed better on average than females in these subtests. No significant gender differences were observed in the WORD subtest. A substantial number of items across the WORD (1–7, 9, 43–45, 48, 49), READ (11, 17–20, 53, 55), and SEC (21, 23–26, 29, 62, 65, 67, 68) subtests exhibited DIF favoring females (see Figure 7). In contrast, only a small set of items, primarily within the ERC (33, 39, 72, 73) subtest, favored males.

Figure 7. Mantel-Haenszel DIF plot comparing low-frequent readers males and females across SweSAT verbal items with ETS delta classification. WORD items represented in 1–10; 41–50. READ items 11–20; 51–60; SEC items 61–70; 61–70. ERC items 31–40; 71–80. A = negligible DIF, B = moderate DIF, and C = large DIF.

Gender comparison among frequent readers (n = 2,822)

In the frequent readers group, Figure 8 shows a decrease in DIF. Although females (n = 1,497) continued to be favored on several items in WORD (5, 6, 7, 9, 44, 48, 49), READ (17–20), and SEC (21), DIF favoring males was more evident in the ERC subtest (33, 37, 39, 71–73) and only a few items were flagged for DIF in the READ subtest (14, 16).

Figure 8. Mantel-Haenszel DIF plot comparing frequent readers males and females across SweSAT verbal items with ETS delta classification. WORD items represented in 1–10; 41–50. READ items 11–20; 51–60; SEC items 61–70; 61–70. ERC items 31–40; 71–80. A = negligible DIF, B = moderate DIF, and C = large DIF.

Cohen's d values comparing males and females showed that males obtained higher scores than females on average in READ [d = 0.24, 95% CI (0.16, 0.31)], SEC [d = 0.18, 95% CI (0.11, 0.26)], and in ERC [d = 0.56, 95% CI (0.48, 0.64)] subtests. Again, no significant gender differences in the WORD subtest.

When comparing both reading frequency groups, frequent reader males were more consistently favored on ERC items than low-frequent readers, while low-frequent reader females were more favored compared to frequent readers counterparts. However, the difference in the number of DIF items between the genders was smaller in the frequent readers group.

Item and content-related differences

In our sample from this SweSAT administration, no consistent patterns were found among the items that displayed DIF regarding the item-format, word class (i.e., noun, verb, adjective) or gender-related content domains. However, males and females tended to perform better on different subtests. Females were favored in Swedish subtests, particularly in two WORD items that included content related to fashion (item 44) and mental health (item 7). In contrast, males were more likely to answer correctly in the ERC subtest, as well as in one item in READ and two SEC items, one of which referenced “fake news” (item 22).

Additionally, several items in the ERC subtest, especially sentence completion items, consistently favored male participants across different EE-related subgroups (items 72 and 73). When we examined the gender-related DIF by gaming frequency, no DIF was observed in sentence completion items in the ERC subtest.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the presence of DIF in the verbal section of the SweSAT in relation to gender and engagement in EE activities, specifically gaming and reading. To address this, SweSAT first-time test-takers' data were used to examine whether items within WORD, READ, SEC, and ERC functioned similarly across gender and EE activities groups. The findings indicate the presence of DIF across all verbal subtests and gender-related differences in relation to EE activities.

Females were generally favored in L1 Swedish items (i.e., READ, SEC), while males were favored in ERC, although males performed better on average across all subtests. These results relate to earlier findings on gender-related DIF and may also imply risk-taking strategies in the test (Graetz and Karimi, 2022; Pae, 2012; Stenlund et al., 2016; Wedman and Laukaityte, 2025). However, while females were favored in WORD, no gender differences emerged in this subtest' performance. Although it is unclear the reason for this result, Wedman (2017) particularly showed that certain WORD items are stereotypically female-related, and other English-related (Wedman and Laukaityte, 2025).

Regarding the presence of DIF and differences in performance in relation to EE activities, the results showed that non-gamers were favored in L1 Swedish items, whereas gamers were favored in ERC items. Moreover, frequent gamers outperformed their counterparts in ERC subtest. This aligns with previous studies linking gaming in English to higher English test scores (Neagu et al., 2025; Sundqvist, 2019; Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015). Although no prior research has reported DIF results in this context, absence of DIF in relation to gaming frequency while still scoring higher in ERC could indicate that items were fair, but frequent gamers were more skilled that low-frequent gamers, differing from Calafato and Clausen (2024) while confirming Muñoz and Cadierno (2021) and De Wilde et al.'s (2020) findings. Similarly, frequent readers were favored in ERC items, while low-frequent readers were favored in L1 Swedish subtests items, yet frequent readers still outperformed across all verbal subtests aligning with previous findings of a positive relationship between reading in English and test performance (Meyer et al., 2024; Tran and Miralpeix, 2024) that may explain the DIF results obtained. However, why frequent readers still performed better across subtests remains unclear as previous literature did not address this issue. Moreover, when examining gender within EE activity groups, females were favored in L1 Swedish items among low and frequent gamers, while some SEC and ERC items favored frequent gamer males, confirming earlier research of gender-based DIF in the SweSAT (Wedman, 2017; Wedman and Laukaityte, 2025). Gaming is positively linked to English proficiency (Muñoz and Cadierno, 2021; Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015), especially among males who tend to engage more frequently. In a similar manner, females were favored in L1 Swedish items among low-frequent readers, whereas males were favored in ERC items; similar gender differences among frequent readers, in line with prior research (Löwenadler, 2022), showing that males were generally favored in ERC items but still performing better across all subtests. These results may suggest that the benefits of EE reading for English performance (Meyer et al., 2024; Warnby, 2022) could be evident. However, the gender differences were also visible in the results suggesting possible item-level content preferences (Wedman and Laukaityte, 2025) or underestimation of female performance (Fischer et al., 2013; Graetz and Karimi, 2022; Karlsson and Wikström, 2021), besides the benefits of exposure to EE activities (Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015; Warnby, 2022). However, the assumption that increased EE exposure interferes with L1 proficiency remains inconclusive (Haman et al., 2017).

To further understand why males and females perform differently on the SweSAT verbal subtests, we considered exposure to EE activities to explore item format. Nevertheless, item format and content patterns were not consistent across items that displayed DIF, possibly due to the use of a single SweSAT administration. Previous SweSAT DIF research found more consistent patterns (Wedman, 2017; Wedman and Laukaityte, 2025), though those studies did not account for EE activities. We found that the sentence completion item-format within ERC subtest often favored males, in line with previous research (Pae, 2012). Regarding item content, among items that showed DIF, some were stereotypically gender-related or English-related (i.e., items related to fashion and mental health favored females, while males favored in SEC items that contained “fake news”). Since neither item-format nor content were consistently linked to the presence of DIF across all items, the gender differences in performance may be related to unmeasured factors in this study, such as test-taking strategies (Stenlund et al., 2016). Moreover, the findings in this study raise important considerations regarding the fairness of the SweSAT as a selection instrument for higher education. While its intended purpose is to provide equal opportunities among test-takers (Lyrén and Wikström, 2020; Stage and Ögren, 2004), the presence of DIF across gender, gaming, and reading frequency groups may indicate that test-takers may not encounter equal conditions. Fairness is a relevant aspect of test validity as test-takers with the same underlying ability should not be disadvantaged (Messick, 1989) by how often they engage in EE activities, and a fair test should reflect the same construct and that scores have the same meaning for all test-takers (AERA et al., 2014, p. 50). Females performed relatively worse in ERC subtest compared to males, who are more exposed to digital games according to our data and previous research (Löwenadler, 2022; Pae, 2012; Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015). This issue should be considered in future studies and SweSAT administrations.

In evaluating the validity of the SweSAT and interpreting the DIF results in this study, it is important to distinguish between construct-relevant impact and construct-irrelevant bias (AERA et al., 2014). Gender-related comparisons in this study revealed that males were consistently favored in ERC items, even within EE activities groups. Specifically, some of these items were sentence completion, which rely on English vocabulary knowledge. Previous research confirmed a strong positive relationship between English vocabulary learning and engagement in EE activities (Warnby, 2022; Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015), suggesting benefits of informal learning that involves no formal structure and self-initiated engagement with EE activities (Livingstone, 2006, p. 206; Kusyk et al., 2025; Sundqvist and Sylvén, 2016). Although both genders engage similarly in EE Reading, males tend to game more, which may explain their advantage in ERC. These results may reflect impact rather than bias, as the gender-related differences in performance could be related to differences in informal L2 language learning (Wedman and Laukaityte, 2025). Nevertheless, males are still favored in ERC even when EE activities are considered, indicating possible bias. Previous research suggests that multiple-choice and sentence completion items often favor males, possibly because of gender differences in test-taking strategies (Pae, 2012; Riukula, 2023; Stenlund et al., 2016). It remains unclear whether the observed DIF in WORD, READ, and SEC items represent bias, as the analysis was limited to a single SweSAT administration. Future research may further investigate patterns of DIF within larger sets of verbal items across multiple administrations and consider incorporating measures of engagement in EE activities among males and females, to clarify the distinction between impact and bias, to ensure that SweSAT assesses the intended constructs for every group.

Conclusion

This study provides relevant insights, with limitations, into the presence of DIF and performance differences between males and females and between EE Reading and EE Gaming in a standardized college admission test. Key findings reveal that females are favored on items assessing L1 Swedish items, while males tend to outperform females in ERC items. Moreover, the engagement in gaming and reading in English may relate to better performance in the SweSAT, with frequent gamers and readers scoring higher in ERC items, while this is not the case for L1 Swedish items. The presence of DIF in gender and EE activities raises questions about the fairness and validity of the SweSAT. These findings highlight the need to distinguish between differences due to impact and potential bias.

Future research on EE and test performance should address several limitations of the present study. To date, no DIF study on college admission tests has incorporated EE activities, which marks an important contribution of this work but also underscores the need for replication. Although the sample size is substantial, the participants in this study achieved higher average scores on the SweSAT verbal subtest than the general test-takers population, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the categorization of gamers and readers employed here, while necessary to simplify the analyses, may have influenced the results due to the absence of standardized frequency classifications for EE activities. Adopting alternative classification frameworks—for example, the model proposed by Cormio et al. (2024) for gaming—could enhance the precision of future analyses. Further, while this study relied on the classical DIF detecting method, future analyses could employ recursive partitioning methods within the IRT framework, such as Rasch trees. These methods provide a robust data-driven approach to detecting sources of variability in item functioning by systematically partitioning respondents into subgroups based on DIF-relevant variables.

Another limitation concerns the restricted number of SweSAT items, which constrained the investigation of item-format patterns and DIF presence. Future studies should therefore include multiple SweSAT administrations to better identify item-level patterns that may be linked to exposure to EE activities. A longitudinal design would be particularly valuable, as it would allow researchers to trace how repeated test-takers benefit from sustained EE engagement over time. Finally, more fine-grained analyses of the types of reading materials in which test-takers engage are needed. Such work could help explain the superior performance observed in L1 Swedish subtests and provide a deeper understanding of how specific forms of EE shape verbal proficiency in high-stakes testing contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TN: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. IL: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AERA APA and NCME. (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association.

Alonso, R. (2023). Out-of-school contact with L2 English across four educational levels. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica de las Lenguas Extranjeras 40, 93–112. doi: 10.30827/portalin.vi40.25311

Artologik (2023). SurveyandReport [computer software]. Available online at: https://www.artologik.com/en/survey-report?pageId=223 (Accessed May 28, 2023).

Calafato, R., and Clausen, T. (2024). Vocabulary learning strategies in extramural English gaming and their relationship with vocabulary knowledge. Comput. Assisted Lang. Learn. 1–19. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2024.2328023

Chen, X., Aryadoust, V., and Zhang, W. (2024). A systematic review of differential item functioning in second language assessment. Lang. Test. 42, 193–222. doi: 10.1177/02655322241290188

Cliffordson, C. (2004). Effects of practice and intellectual growth on performance on the Swedish Scholastic Aptitude Test (SweSAT). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 20, 192–204. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.20.3.192

Clifton, C. J., Meyer, A. S., Wurm, L. H., and Treiman, R. (2013). “Language comprehension and production,” in Handbook of Psychology, Volume 4, Experimental Psychology, eds. A. F. Healy, and R. W. Proctor (Wiley), 523–547. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/11858/00-001M-0000-0011-30C2-3 (Accessed May 20, 2025).

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cormio, L., Agostinelli, T., and Mengoni, M. (2024). A unified framework to catalogue and classify digital games based on interaction design and validation through clustering techniques. Multimed. Tools Appl. 84, 15479–15499. doi: 10.1007/s11042-024-19614-w

De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., and Eyckmans, J. (2020). Learning English through out-of-school exposure. Which levels of language proficiency are attained and which types of input are important? Bilingualism: Lang. Cogn. 23, 171–185. doi: 10.1017/S1366728918001062

Desjardins, C. D., and Bulut, O. (2018). Handbook of Educational Measurement and Psychometrics Using R. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall/CRC. 258–259. doi: 10.1201/b20498

Fischer, F. T., Schult, J., and Hell, B. (2013). Sex-specific differential prediction of college admission tests: a meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol., 105, 478–488. doi: 10.1037/a0031956

Galloway, A. (2005). “Non-Probability sampling,” in Encyclopedia of Social Measurement, 1st Edn., Vol. 2, ed. K. Kempf-Leonard (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 859–864. doi: 10.1016/B0-12-369398-5/00382-0

Graetz, G., and Karimi, A. (2022). Gender gap variation across assessment types: explanations and implications. Econ. Educ. Rev. 91:102313. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2022.102313

Haman, E., Wodniecka, Z., Marecka, M., Szewczyk, J., Bialecka-Pikul, M., Otwinowska, A., et al. (2017). How does L1 and L2 exposure impact L1 performance in bilingual children? Evidence from Polish-English migrants to the United Kingdom. Front. Psychol. 8:1444. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01444

Hanghøj, T., Kabel, K., and Jensen, S. H. (2022). Digital games, literacy and language learning in L1 and L2: a comparative review. L1-Educ. Stud. Lang. Literat. 22, 1–44. doi: 10.21248/l1esll.2022.22.2.363

Holland, P. W., and Thayer, D. T. (1985). An alternate definition of the ETS delta scale of item difficulty. ETS Research Rep. Ser. 1985, 1–10. doi: 10.1002/j.2330-8516.1985.tb00128.x

Karlsson, L., and Wikström, M. (2021). Gender Differences in Admission Scores and First-Year University Achievement. Umeå University. Available online at: http://www.usbe.umu.se/ues/ues1001.pdf (Accessed May 10, 2025).

Krashen, S. D. (1976). Formal and informal linguistic environments in language acquisition and language learning. Tesol Quart. 10, 157–168. doi: 10.2307/3585637

Kusyk, M., Arndt, H. L., Schwarz, M., Yibokou, K. S., Dressman, M., Sockett, G., et al. (2025). A scoping review of studies in informal second language learning: trends in research published between 2000 and 2020. System 130:103541. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2024.103541

Livingstone, D. W. (2006). “Informal learning: conceptual distinctions and preliminary findings,” in Learning in Places. The Informal Education Reader, eds. Z. Beckermann, N. C. Burbules, and D. Silverman-Keller (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 203–227.

Löwenadler, J. (2022). Trends in Swedish and English reading comprehension ability among Swedish adolescents: a study of SweSAT data 2012–2018. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 67, 591–606. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2022.2042841

Lyrén, P.-E., and Wikström, C. (2020). “Admissions practices in Sweden,” in Higher Education Admissions Practices: An International Perspective, eds. M. E. Oliveri and C. Wendler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 203–216. doi: 10.1017/9781108559607.012

Magis, D., Béland, S., Tuerlinckx, F., and De Boeck, P. (2010). A general framework and an R package for the detection of dichotomous differential item functioning. Behav. Res. Methods 42, 847–862. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.3.847

Mantel, N., and Haenszel, W. (1959). Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 22, 719–748.

Messick, S. (1989). “Validity,” in Educational Measurement, 3rd Edn., ed. R. L. Linn (New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc; American Council on Education), 13–103.

Meyer, J., Fleckenstein, J., Krüger, M., Keller, S. D., and Hübner, N. (2024). Read at home to do well at school: informal reading predicts achievement and motivation in English as a foreign language. Front. Psychol. 14:1289600. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1289600

Muñoz, C., and Cadierno, T. (2021). How do differences in exposure affect English language learning? A comparison of teenagers in two learning environments. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 11, 185–212. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.2.2

Neagu, T., Eklöf, H., Laukaityte, I., and Wedman, J. (2025). Reading, watching and gaming: exploring the relationships between extramural English activities and academic L2 English reading comprehension in a Swedish university admissions test context. Educ. Inq. 15, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/20004508.2025.2556572

Pae, T. I. (2012). Causes of gender DIF on an EFL language test: a multiple-data analysis over nine years. Lang. Test. 29, 533–554. doi: 10.1177/0265532211434027

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., and Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of game-based learning. Educ. Psychol. 50, 258–283. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533

R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing[Computer software]. Vienna, Austria. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed April 10, 2025).

Reardon, S. F., Kalogrides, D., Fahle, E. M., Podolsky, A., and Zárate, R. C. (2018). The Relationship between test item format and gender achievement gaps on math and ELA tests in fourth and eighth grades. Educ. Res. 47, 284–294. doi: 10.3102/0013189X18762105

Revelle, W. (2025). psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research (Version 2.2.5). Northwestern University. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=psych (Accessed August 26, 2025).

Riukula, K. (2023). Gender differences in multiple-choice questions and the risk of losing points. J. Finnish Econ. Assoc. 4:122157. doi: 10.33358/jfea.122157

Shaw, A. (2012). Do you identify as a gamer? Gender, race, sexuality, and gamer identity. New Media Soc. 14, 28–44. doi: 10.1177/1461444811410394

Sigurjónsdóttir, S., and Nowenstein, I. (2021). Language acquisition in the digital age: L2 English input effects on children's L1 Icelandic. Second Lang. Res. 37, 697–723. doi: 10.1177/02676583211005505

Sörman, D. E., Ljungberg, J. K., and Rönnlund, M. (2018). Reading habits among older adults in relation to level and 15-year changes in verbal fluency and episodic recall. Front. Psychol. 9:1872. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01872

Stage, C., and Ögren, G. (2004). The Swedish Scholastic Assessment Test (SweSAT). Development, Results and Experiences. (Report No. EM 49:2004). Umeå University.

Stage, C., and Ögren, G. (2010). Högskoleprovet våren och hösten 2010: provdeltagaregruppens sammansättning och resultat [The Higher Education Entrance Examination in Spring and Fall 2010: Composition and Results of the Test-Taker Group]. (Report No. BVM 43:2010). Umeå University.

Stenlund, T., Eklöf, H., and Lyrén, P. E. (2016). Group differences in test-taking behaviour: an example from a high-stakes testing program. Assess. Educ.: Princ. Policy Pract. 24, 4–20. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1142935

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English Matters: Out-of-School English and Its Impact on Swedish Ninth Graders' Oral Proficiency and Vocabulary (Doctoral dissertation). Karlstad University. Available online at: http://kau.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:275141 (Accessed January 16, 2023).

Sundqvist, P. (2013). “Categorization of digital games in English language learning studies: Introducing the SSI Model,” in 2013 EUROCALL Conference Èvora, Portugal Proceedings: 20 Years of EUROCALL: Learning From the Past, Looking to the Future, eds. L. Bradley and S. Thouësny (Dublin; Voillans: Research-Publishing.net), 231–237. doi: 10.14705/rpnet.2013.000166

Sundqvist, P. (2019). Commercial-off-the-shelf games in the digital wild and L2 learner vocabulary. Lang. Learn. Technol. 23, 87–113. doi: 10.64152/10125/44674

Sundqvist, P. (2024). Extramural English as an individual difference variable in L2 research: methodology matters. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 44, 79–91. doi: 10.1017/S0267190524000072

Sundqvist, P., and Sylvén, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in Teaching and Learning: From Theory and Research to Practice. Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-46048-6

Sundqvist, P., and Uztosun, M. S. (2024). Extramural English in Scandinavia and Asia: scale development, learner engagement, and perceived speaking ability. TESOL Q. 58, 1638–1665. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3296

Sundqvist, P., and Wikström, P. (2015). Out-of-school digital gameplay and in-school L2 English vocabulary outcomes. System 51, 65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2015.04.001

Swedish Internet Foundation (2023). Svenskarna och internet 2023: En årlig studie av svenska folkets internetvanor [The Swedes and the Internet 2023: An Annual Survey of the Internet Habits of Swedish People]. Available online at: https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/ (Accessed October 11, 2023).

Swedish Media Council (2023). Ungar och medier 2023: En statistisk undersökning av ungas medievanor och attityder till medieanvändning [Young People and the Media 2023: A Survey of Young People's Media Habits and Attitudes Towards Media Use]. Available online at: https://mediemyndigheten.se/globalassets/rapporter-och-analyser/ungar-och-medier/ungar–medier-2023_anpassad.pdf (Accessed June 19, 2025).

Sylvén, L. K., and Löwenadler, J. (2023). “Let's play videos and L2 academic vocabulary,” in Digital Games in Language Learning, eds. M. Peterson and N. Jabbari (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 93–108. doi: 10.4324/9781003240075-6

Sylvén, L. K., and Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL 24, 302–321. doi: 10.1017/S095834401200016X

Tran, L., and Miralpeix, I. (2024). Out-of-school exposure to English in EFL teenage learners: is it related to academic performance? Educ. Sci. 14:393. doi: 10.3390/educsci14040393

Warnby, M. (2022). Receptive academic vocabulary knowledge and extramural English involvement–is there a correlation? ITL—Int. J. Appl. Ling. 173, 120–152. doi: 10.1075/itl.21021.war

Wedman, J. (2017). Reasons for gender-related differential item functioning in a college admissions test. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 62, 959–970. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2017.1402365

Wedman, J., and Laukaityte, I. (2025). Validity Evidence Based on the Internal Structure of a College Admission Test (Paper presentation). QRM Conference 2025, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. (Version 3.5.1). Available online at: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (Accessed May 16, 2025).

Keywords: test fairness, gender differences, language proficiency, informal English learning, Mantel-Haenszel, college admission test

Citation: Neagu T and Laukaityte I (2025) Gender-related differential item functioning in SweSAT verbal subtests: the role of extramural English activities in first and foreign language performance. Front. Educ. 10:1656734. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1656734

Received: 30 June 2025; Accepted: 04 September 2025;

Published: 24 September 2025.

Edited by:

Gavin T. L. Brown, The University of Auckland, New ZealandReviewed by:

Farshad Effatpanah, Technical University Dortmund, GermanyKuo-Zheng Feng, National Chengchi University, Taiwan

Copyright © 2025 Neagu and Laukaityte. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Teodora Neagu, dGVvZG9yYS5uZWFndUB1bXUuc2U=

Teodora Neagu

Teodora Neagu Inga Laukaityte

Inga Laukaityte