- Department of English, School of Social Sciences and Languages, Vellore Institute of Technology, Chennai, India

In response to the escalating ecological crises, this study aims to propose a narrative-enhanced, psycho-emotional framework in environment education. This research integrates three interdisciplinary domains, ecopsychology, eco-emotions, and environmental narratives, to construct a method that strengthens learners’ ecological identity, emotional resilience, and pro-environmental behavior. Drawing from theories of environmental psychology, emotional regulation, and narrative pedagogy, the study explores how affective connections with nature, such as biophilia, topophilia, and eco-hope, can be cultivated through narrative-enhanced education. Using a qualitative approach, the paper analyses the influence of eco-emotions (both negative and positive) on learners’ attitudes and behaviors toward climate action, highlighting their potential for eco-consciousness. The findings emphasize that narrative-enhanced environmental education (NEEE) promotes psychological well-being, fosters human-nature attachment, and prepares learners to engage with climate actions with empathy. The study advocates for a paradigm shift in environmental education toward a method rooted in eco-emotions, ecological identity, and symbiotic learning. The paper advocates a paradigm shift in environmental education toward an emotionally rooted, identity-driven, and symbiotic model that promotes long-term ecological stewardship and a symbiocentric future.

Introduction

Current chronic environmental degradation, marked by the constant climate change and the loss of ecosystems due to natural or man-made calamities, highlights the immediate attention or innovative approaches to environmental education and awareness. While traditional methods often rely on scientific knowledge and rational arguments, research suggests that emotional engagement and narratives structured as stories could play a significant role in shaping pro-environmental behavior (Nakano and Hondo, 2023). In 1962, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring marked the beginning of modern environmental movements by emphasizing the need to protect the environment, highlighting that only through human awareness could harmonious coexistence between people and nature be achieved (Fang et al., 2022). Integrating ecopsychology, eco-emotions, and fictional narratives into environmental education provides a narrative-based approach that fosters a deep emotional connection with nature, enhancing environmental awareness and action (Corbett, 2021).

Ecopsychology, as a field, has long examined the interaction between humans and their surroundings, demonstrating how place attachment, environmental perception and cognition, and emotional responses to nature influence behavior. A meta-analytical study titled The Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-analysis shows that individuals with a strong connection with nature report higher levels of eudaimonic well-being, which are characterized as self-realization, personal growth, and purpose (Pritchard et al., 2019). While disconnection from natural spaces or constant climate changes and environmental degradation leads to stress and apathy. In the detailed study of the impacts of climate change on mental health, researchers highlight that “the effect of climate change can be direct or indirect, short-term or long-term.” Also, the “acute events can act through mechanisms similar to those of traumatic stress, leading to well-understood psychopathological patterns” (Cianconi et al., 2020). Ecopsychological theorists expand on this by emphasizing the emotional and psychological relationship between humans and the natural world, arguing that reconnecting with nature can lead to both personal healing and ecological responsibility. From the educational perspective, a growing body of research in environmental education underscores the power of storytelling as a tool for promoting pro-environmental behavior. The narrative method is an effective medium that focuses on the information by having a personal connection through glimpses of real-life experiences and interconnections between different topics, and emphasizing the significant concepts (Guazzini et al., 2025). By engaging learners through the narrative-based method, environmental education can move beyond abstract statistics to create meaningful connections that inspire individuals to participate in proper climate actions. This paper proposes a psycho-emotional method for environmental education that integrates ecopsychology, eco-emotions, and storytelling-based approaches. The method focuses on experiential learning, emotional engagement, and narrative-driven education to strengthen personal and collective responsibility for environmental conservation.

Method details

The research analyses the unified ideas of ecopsychology, eco-emotions and environmental education to foster environmental behavior effectively using a narrative-enhanced psycho-emotional method. Instead of acknowledging the psychopathological impacts of Eco-emotions, this study foregrounds the importance of incorporating these emotions in environment education. Even though the previous studies identified that nature-based activities ensure the human-nature attachments and the development of Eco-consciousness, they rarely incorporated the explicit psycho-emotional and narrative framework necessary for translating this awareness into sustained behavior. This research focuses more on how to achieve stronger connections with Nature by incorporating eco-emotions in environment education. The traditional environmental education methods have focused on the cognitive learning method, a model that has been criticized for failing to bridge the gap between knowledge and behavior (Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). This gave way to studying the interrelated ideas of ecopsychology and cognitive methods. The main objective of this method is to incorporate the concepts of Eco-emotions to develop hope, resilience, and pro-environmental behavior among learners. This study uses a qualitative approach to examine the nuanced ideas of eco-emotions, to foster effective environment-friendly behavior through narrative-enhanced environment education.

Environment education (EE)

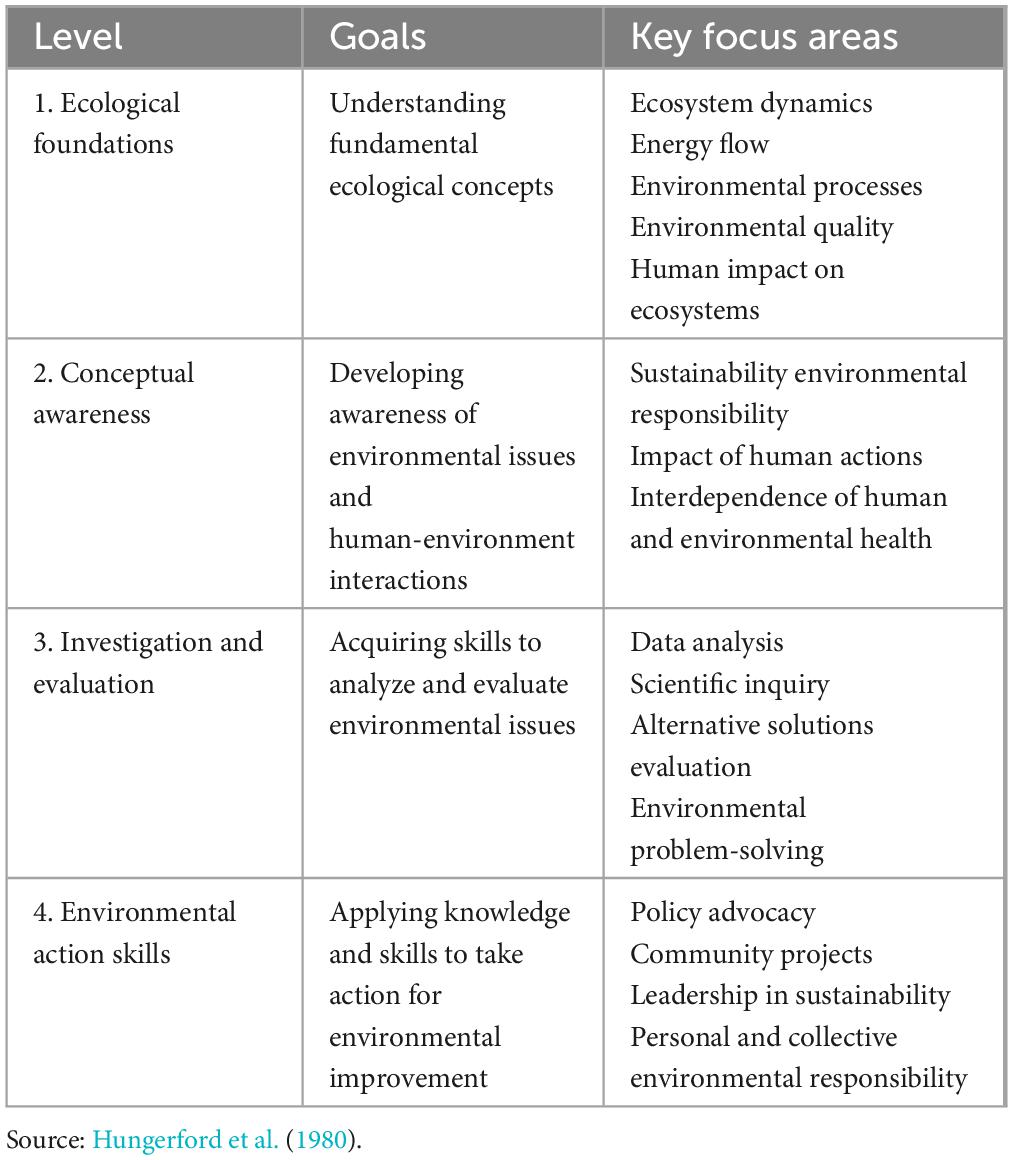

In the past few decades, the research interest in the field of environmental education (EE) has bloomed and been established further in various schools of theories, with the term itself appearing as early as 1948 and gaining significant momentum throughout the 1960s (Carter and Simmons, 2010). According to Stapp (1969), the father of Environmental Education (EE), it is defined as the aim at “producing a citizenry that is knowledgeable concerning the biophysical environment and its associated problems, aware of how to help solve these problems, and motivated to work toward their solution.” This foundational definition, emphasizing knowledge, awareness, and motivated action, continues to guide the field’s efforts to cultivate environmentally literate citizens, particularly in the context of the global climate crisis (Corbett, 2021). The goal of Environment education is to cultivate citizens who are concerned about the environment and willing to take steps for their actions, educate them about the root cause of the ecological issues, and equip them with active and positive environment-friendly behaviors (Fang et al., 2022; Stapp, 1969). In Hungerford et al. (1980), curriculum developers established goals for developing environmental education, drawing on the ideas of William B. Stapp, Harvey, and the Tbilisi Intergovernmental Conference. The four levels of environmental education goals are shown in the table below. The first level, “Ecological foundation,” seeks to provide sufficient knowledge, including the human impact and the ecosystem, concerning the environmental issues. The “Conceptual Awareness” guides the learners to develop an awareness of the individual and collective actions that have a greater influence on the environmental issue (Hungerford et al., 1980). The third level, “Investigation and evaluation,” equips students with the analytical skills necessary to evaluate environmental issues via problem-solving, scientific research, and data analysis. The final level, “Environment Action Skills,” guides the learners to be involved in positive environmental actions and sustainability, highlighting both individual and group accountability for the quality of the environment (Table 1).

The escalating global concern over climate change and environment degradation has cemented the critical relevance of these issues to both societies at large and the younger generation. Thus, environment education has been integrated as a form of action and solution in educational curricula (Leimbach and Milstein, 2022). Given the growing public concern over environmental issues, education must address this significant issue and assess the possible long-term effects of environmental degradation (Tilbury, 1995). Tilbury’s (1995) three-fold approach to Environment Education for Sustainability (EEFS) emphasizes three distinct pedagogical strategies, namely Education about the Environment, Education in Environment, and Education for the Environment. The objectives of these strategies are to educate awareness and to develop the knowledge and understanding about human-nature interactions (Tilbury, 1995).

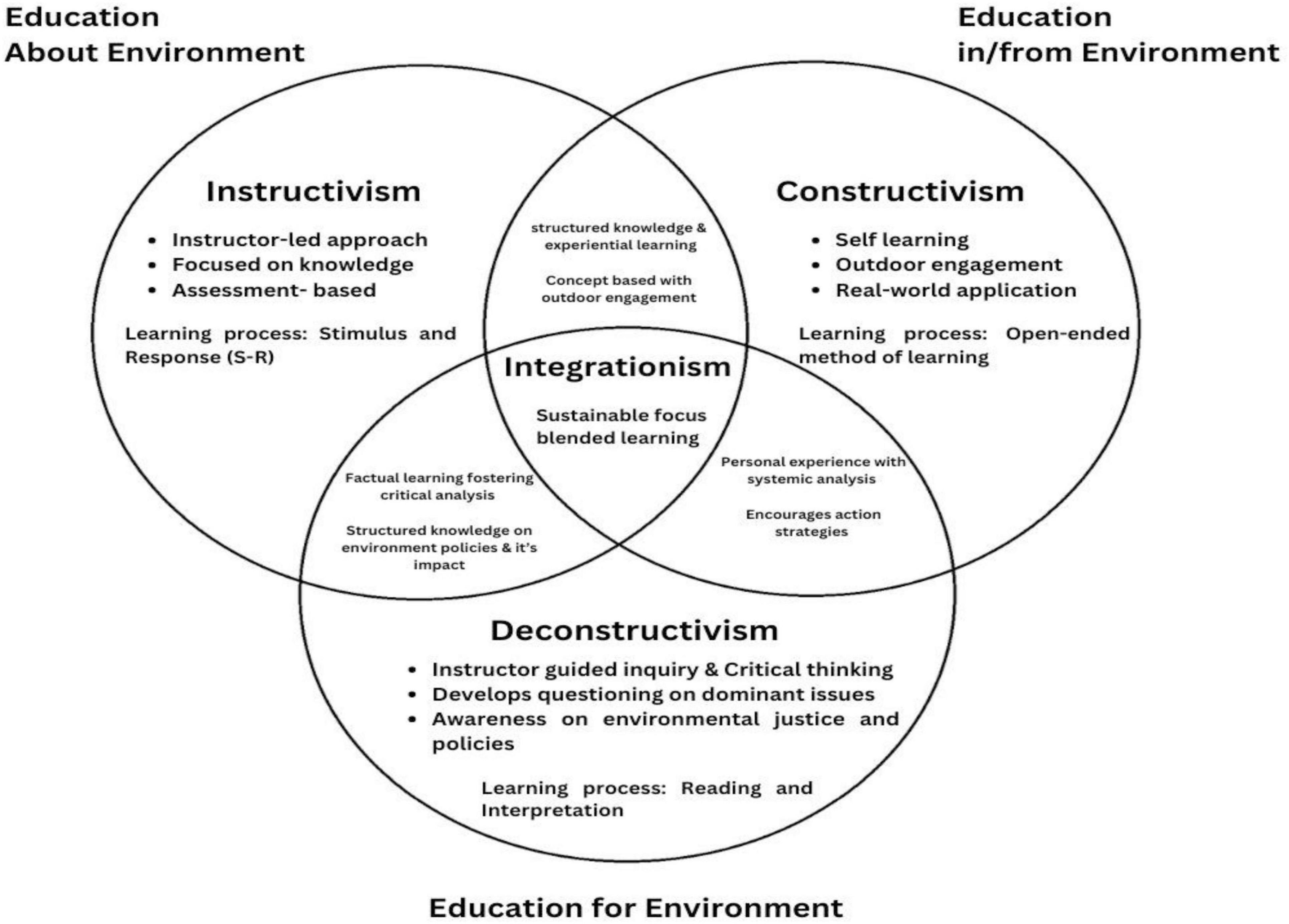

Figure 1 illustrates the themes and different pedagogical approaches of environmental education by categorizing them into instructivism, deconstructivism, constructivism, and the integrated environmental educational approach, which is integrationism. “Instructivism,” a traditional teaching approach, emphasizes direct instruction and instructor-led learning, which focuses on transmitting information about environmental education and emphasizes the significance of professional development in relation to curriculum objectives (Onyesolu et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2022). This approach provides a learning method where the learners’ knowledge is constructed within the disciplines of ecology. The learning method asserts that the teachers are the primary learning agents, it doesn’t give room for self-discovery to the learners. Education about the environment aims to teach learners about the environmental concepts, which paves the way for critically examining issues logically and constructively (Fang et al., 2022). This theme of environmental education, which reflects the synoptic elements, reflects the basic knowledge of understanding the principles and our complex relationship with the environment (Palmer, 1998; Schools Council, Project Environment, 1974).

Figure 1. Venn diagram of environmental education approaches [adapted from “The Living Environmental Education” by Fang et al. (2022)].

The next term, “Deconstructivism,” pertains to the environment for education, encourages critical questioning and concerns a learning method with values, attitudes, and positive actions reflecting ethical knowledge on the policies and social justice (Palmer, 1998). This method guides the learners in generating critical theories and ideas, but it cannot be actively present in the process of environmental improvement (Fang et al., 2022). The term “Constructivism” is a learning theory that posits people built their knowledge and comprehension of the world through experiencing the environment and reflecting on those experiences. It is a philosophical idea derived from the psychological term cognitivism and adopts a philosophical stand of “non-objectivism” (Harasim, 2017). This approach emphasizes education in or from the environment and encourages the learners to perform hands-on training, self-discovery, experimental activities, and real-world application. Finally, the “Integrationism” approach blends these methodologies, combining structured knowledge with experiential learning to foster a well-rounded understanding and active engagement in sustainability practices.

Environmental psychology and cognitive learning models

In the 21st century, there has been a rise in environmental degradation, such as pollution, deforestation, global warming, climate change, etc., which have a greater impact on the global ecosystem (Reid et al., 2005). Environmental Psychology is a branch of psychology that studies the relationship between humans and nature to enhance human well-being and improve man-environment relations (Steg et al., 2012; Bonnes and Carrus, 2017). For this psycho-emotional framework, two domains are critical: the study of environmental stress and psychological restoration, and the investigation of environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior. The environment in which humans currently live is often faced with physical conditions that are chronic, powerful environmental distress, which leads to psychological stresses and negative emotions that have an effect on individuals. The extensive research on the impact of environmental stressors on cognitive functions points out that climate change, temperature, etc., affect simple and complex cognitive performance, which leads to cognitive fatigue and reduced productivity of individuals (Taylor et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2019). The research from the contrasting viewpoint was conducted in the field of ecopsychology, which addresses how the physical environment can restore mental well-being and promote cognitive functions in a restorative environment (Bonnes and Carrus, 2017). The Restorative environment is an environment where one can restore the effectiveness of mental energies or cognitive fatigue that are depleted from direct attention toward the climate crisis (Kaplan and Kaplan, 1989).

Rachel and Stephen Kaplan’s Attention Restorative Theory (ART) propose that spending time with the environment restores the ability to concentrate when the restorative environment meets the four requirements: the chance to (1) “be away” from everyday stresses, (2) experience expansive spaces and contexts (“extent”); (3) engage in activities that are “compatible” with our intrinsic motivations, and (4) critically experience stimuli that are “softly fascinating” (Kaplan, 1995). This combination of factors encourages “involuntary” or “indirect attention” and enables our “voluntary” or “directed” attention capacities to recover and restore (Tilbury, 1995; Ohly et al., 2016).

The rising climate phenomena and ecological deterioration lead to rapid changes in the environment at local and global levels (IPCC, 2023). These damages to the ecosystem also impact human activities and will continue in the future. In recent decades, environmental psychology studies have addressed the need for environmental concern, also known as pro-environmental behavior. Pro-environmental behaviors refer to the actions taken by individuals to minimize environmental harm and actively participate in restoring the ecological balance by performing necessary steps like recycling, conserving resources like reducing energy consumption, saving water, and taking steps to reduce one’s carbon footprint, ecological conservation, and wildlife protection.

This pro-environmental behavior is supported by the Moral Norm Activation Theory (MNAT), originally proposed by Schwartz (1977). As summarized by Stern (2000), MNAT holds that altruistic behavior, including PEB, occurs in response to personal moral norms. These norms are activated when individuals perceive that conditions pose threats to others (awareness of adverse consequences, or AC) and believe that their actions could mitigate those consequences (ascription of responsibility to self, or AR). In this study, these selected domains of ecopsychology show a significant yield in the development of cognitive learning.

The main goal of Environmental Education (EE) is to improve human values regarding the environment and develop a sense of responsibility toward ecological systems. These can be achieved by behavioral and cognitive-based learning methods. The widely used learning methods are the Bloom-style Learning method, the Hungerford-style learning method, and the ABC emotion learning theory. The Bloom-style learning method divides the environmental educational goals into cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains (Bloom et al., 1956). The cognition aspect of this learning method is to develop knowledge based on the environment and apply that acquired knowledge to an action. The Hungerford style of learning method divides the goals into knowledge, attitude, and behavior areas (Fang et al., 2022). Hungerford believes that in Environmental Education, “Knowledge” has an effect on the “attitude” of an individual, and that has an effect on the “behavior” that provides positive actions toward the natural crisis. This makes the Hungerford-style learning method have an ultimate impact on environmental literacy and human pro-environmental behavior (Hungerford and Volk, 1990). Ellis’s (1957) ABC emotion theory, A equates to “Activating” or “Induced events,” B is “Beliefs,” and C is “Consequences” that trigger human emotional and behavioral consequences. Ultimately, as suggested by Fang et al. (2022), the future of Environmental Education lies in the integration of these metacognitive models to ensure “emotional growth” and the development of a “mature mind.” This integrated approach refines mature personal traits and promotes a model of “responsible environmental behavior” by allowing individuals to achieve control over unreasonable thoughts and self-adjust toward ecological goals. This synthesis of cognitive learning and emotional development forms the conceptual basis for our proposed Psycho-Emotional Framework.

Eco-emotions

Living organisms are more biologically stable with guided and stable climate systems, but they tend to be more sensitive to sudden climate changes or atmospheric differences. That term is called Meteorosensitivity, susceptibility to changes in weather and atmospheric conditions (i.e., temperature, humidity, brightness, rate of airflow, thunderstorms, etc.) (Cianconi et al., 2023). The Psychopathological phenomenon that an individual can experience due to these weather changes is called “Meteoropathy,” which is derived from the Greek words “Meteora” (Things high in the air or celestial phenomena) and “Pathos,” meaning illness, suffering, or pain (Mazza et al., 2011). The symptoms of this can be psychophysical (i.e., irritability, mental and physical weakness, hypertension, headache, hyperalgesia, etc.) (Cianconi et al., 2023). The climate emotions, or ecological emotions, are defined as affective phenomena that are significantly experienced by chronic climate deviations. There may be various kinds of factors that influence people’s emotions in an ecological context, such as the general situation in one’s life, one’s temperament, daily events, social dynamics, and climate change impacts (Pihkala, 2022; Kurth and Pihkala, 2022). “Climate emotions” or “Eco-emotions” were recently coined by researchers to address the emotional experience of ecological changes or chronic climatic degradations (Cianconi et al., 2023). The emotions referred to are not just any emotions but rather mental states (i.e., relatively consent behavior, conditions, and thoughts) and mental health syndromes (i.e., characterized by a series of symptoms) (Cianconi et al., 2023; Pihkala, 2022).

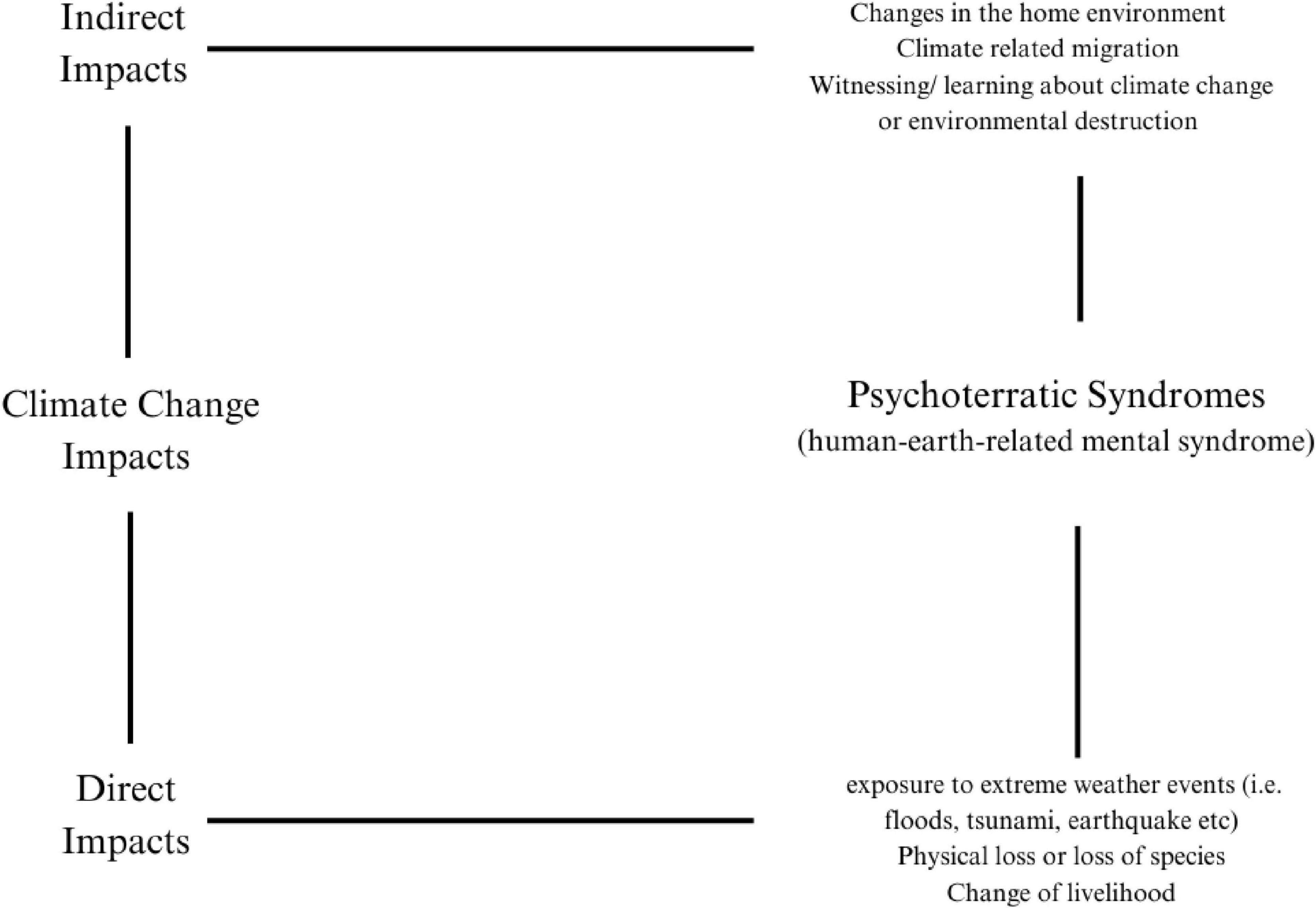

Glenn Albrecht, an Australian professor and environmentalist, introduced the term “Solastalgia” in 2003, which talks about the human distress over a particular locality or home environment, closely related to the term place attachment of an individual. The development of Solastalgia leads to the emergence of the term that denotes the human-earth-related mental syndrome, “Psychoterratic syndrome.” “Psychoterratic illness is defined as earth-related mental illness where people’s mental wellbeing (psyche) is threatened by the severing of “healthy” links between themselves and their home/territory (Albrecht et al., 2007). The term “Psychoterratic Syndrome” turned out to be an umbrella term for earth-related syndromes like eco-anxiety, eco-grief, eco-distress, eco-guilt, eco-shame, eco-paralysis, eco-phobia, eco-anger, environmental trauma, environmental PTSD, etc., (Cianconi et al., 2023; Pihkala, 2022). The Figure 2 illustrates the direct and indirect impacts of climate change that affect the psychological well-being of humans.

Figure 2. The psychological consequences of climate change: direct and indirect impacts leading to psychoterratic syndromes [adapted from Albrecht (2019), Berry et al. (2009)].

Pro-environmental behavior and cognitive reappraisal

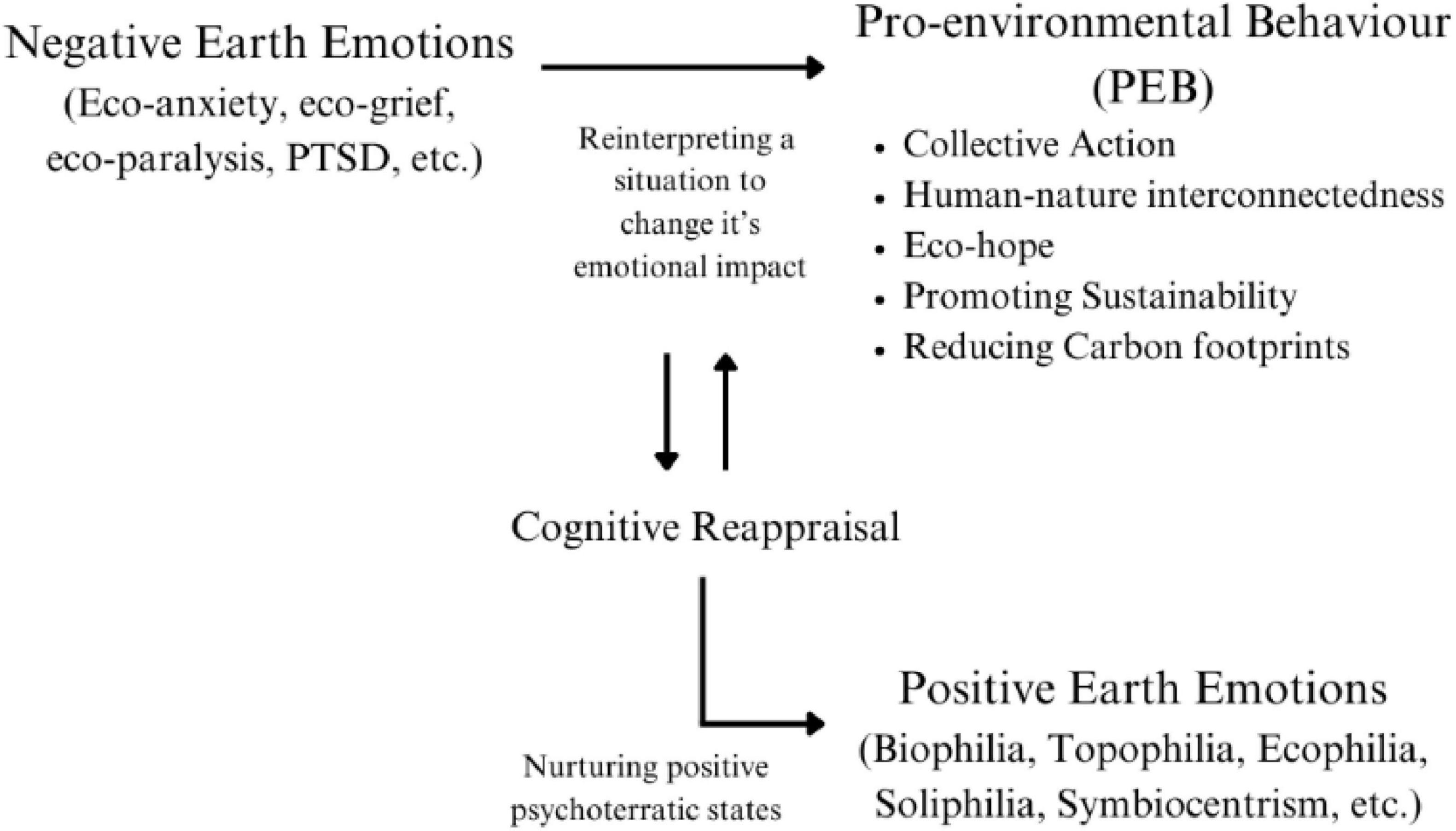

Cognitive reappraisal is an emotional regulation strategy that got much attention during the 2000s, primarily driven by the influential works of Gross (1998), Gross and Thompson (2007). It is an antecedent-focused emotion control method where an individual reinterprets a situation to change its emotional impact, rather than suppressing or avoiding the emotion itself (Gross, 1998). Cognitive reappraisal is an antecedent-focused emotion control method that begins before the emotional responses are apparent. It refers to cognitive changes produced in response to a circumstance (Wang and Yin, 2023). In the research conducted by Panno et al. (2015, 2017) to study the environment and behavior, researchers highlight that the emotional regulation strategies (i.e., cognitive reappraisal) promise novel insights into the development of environment-friendly behavior and motivate individuals to reduce their ecological footprints. The rise of eco-emotion studies and psychoterratic syndromes led to the discovery of varied symptoms caused by climate change threats and concurrent environmental degradation. For example, higher eco-anxiety symptoms are associated with different health issues such as insomnia, anxiety, stress, chronic mental distress, uncontrollability, helplessness, hopelessness, etc., (Cianconi et al., 2023; Boluda-Verdú et al., 2022). This spectrum of negative psychoterratic emotions, including eco-grief and eco-paralysis, functionally impairs the cognitive processes necessary for calm reflection and problem-solving, manifesting as difficulties in remaining calm, concentrating, and feeling control over one’s life (Stewart, 2021). In the work “Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World,” Glenn Albrecht categorized Earth-related human emotions into Negative and Positive Earth Emotions. Negative earth emotions vary from slight to individuals at the extreme edge of emotional and psychological responses to human desolation and separation from nature. These emotions are expressed by people who have not given up on their attachment to nature and life (Albrecht, 2019). Scholarly interest in the affective dimensions of pro-environmental behavior has grown substantially, with a burgeoning body of literature examining the interplay between emotions, cognitive processes, and sustainability-related actions. Recent studies highlight how negative environmental emotions (i.e., eco-anxiety, guilt, and eco-paralysis) promote positive environmental actions (i.e., human-nature connectedness, eco-hope, and collective action), which shape environmental engagement, underscoring the need for nuanced theoretical and empirical approaches in this rapidly advancing domain (Stanley et al., 2021; Fritsche et al., 2017; Kovács et al., 2024). The empirical study was conducted in the context of behavioral and climate actions and found that the participants’ frequent use of cognitive reappraisal predicted stronger environmental motivation and greater participation in sustainability efforts (Panno et al., 2015). Positive Earth emotions like Biophilia, Ecophilia, Topophilia, and Soliphilia nurture pro-environmental actions by reinforcing an individual’s sense of human-nature connectedness (Schultz, 2002). This innate psychological bond with nature is repeatedly shown to be a key predictor of pro-environmental behavior across various contexts (Teixeira et al., 2022). Glenn Albrecht stated that the positive psychoterratic conditions are achieved through the reintegration of humans with both the physical and the built symbioment (Albrecht, 2019). The symbioment refers to an environment characterized by the mutual flourishing of all life forms (Albrecht, 2019). The corresponding ideological shift is the sumbiocentric perspective, which moves beyond human-centered (Anthropocentric) concepts by prioritizing the vital role of symbiosis in all human affairs (Albrecht, 2019). Positive Psychoterratic states are not merely affective responses but form the psychological infrastructure for pro-environmental behavior, resilience, and sustainable creativity. The development of affective ecology is made possible by this emotional reintegration, which promotes a change in environmental awareness from domination to symbiosis. Under such a paradigm, Ecophilia, biophilia, and topophilia provide the emotional framework for the Symbiocene, a framework that can be fostered through the use of cognitive reappraisal methods and Environmental Education (Figure 3).

Narrative-enhanced environmental education (NEEE)

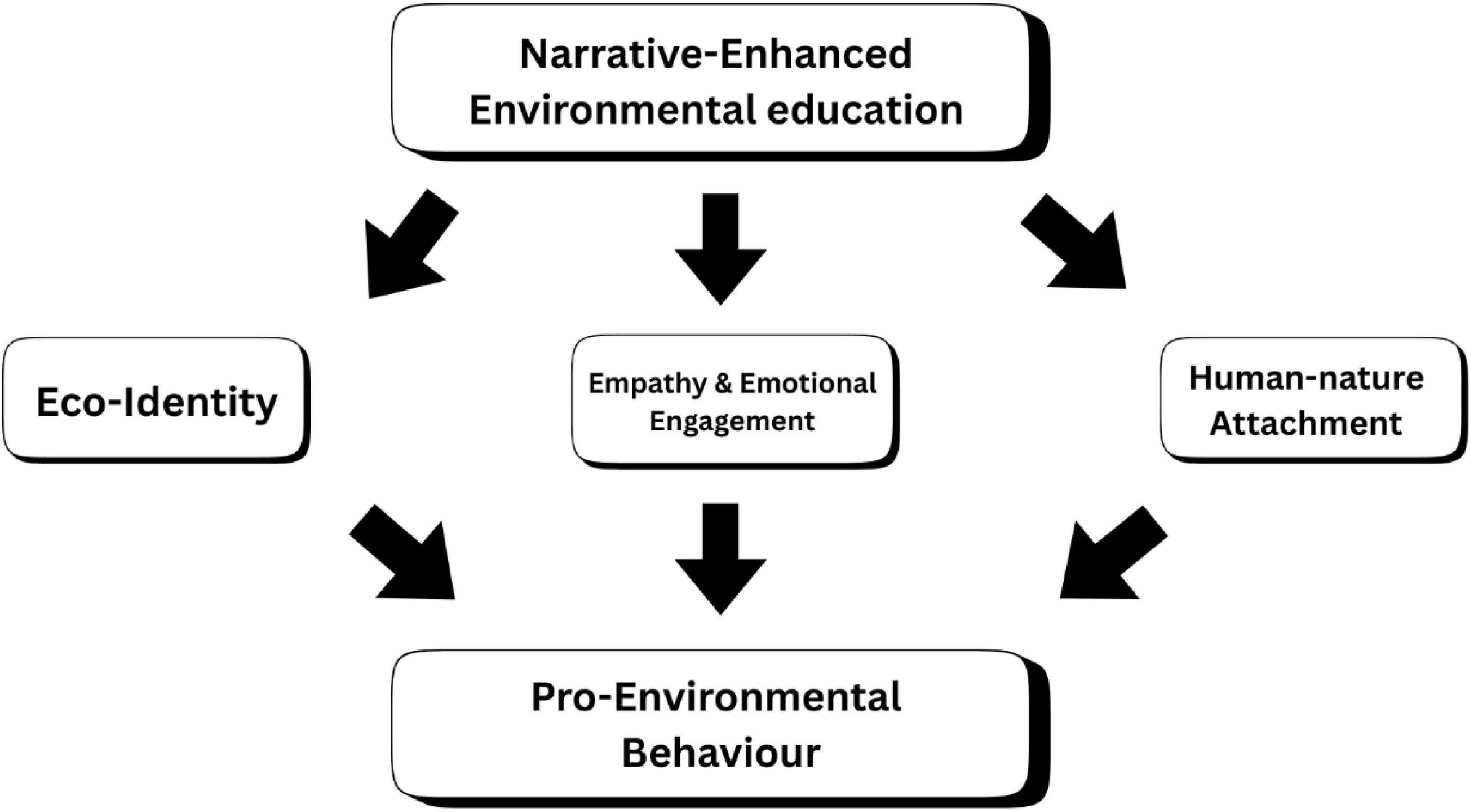

The narrative-based approach in Environment Education offers a hands-on experience to the learners, integrating affective, cognitive, and moral dimensions by leveraging storytelling as a transformative pedagogical tool. In the study conducted on children aged 6–8 years old, the researchers found that the narrative-based education significantly improves their environmental attitudes and awareness. However, the study also found that the achievement of pro-environmental behavior among the children is insignificant. The researchers conducted short video clippings about wildlife and humans as a narrative method, in an interval of 1 day and 7-days intervals. The time interval for nurturing pro-environmental behavior in a short period turned out to be difficult. To make children socialize with environmental actions and the formation of pro-environmental behavior requires continuous learning and time (Yang et al., 2022). One of the recommended methods to cope with negative earth emotions, for collective learning and strategic communication, is storytelling for social and behavior change (Wang et al., 2023). The narrative method has been enhanced as a purposeful attempt to influence our feelings, thinking, and collective action for sustainability (Joosse et al., 2023). The fact-based narratives have minimal effect on motivating individuals to be eco-conscious, but also embodied cognition for environmental action. The primary goal of climate communication is to persuade lay audiences as to the (a) severity of the problem and (b) need for action. In the study that deals with Stories Versus Facts, which triggers emotion and action, the researchers argued that, unlike stories, analytical narratives did not reflect upon the emotional arousal eliciting pro-environmental behavior (Morris et al., 2019). Narrative-enhanced environmental education works on multiple methods for pro-environmental behavior development that are Eco-identities, empathy and emotional engagement, and human-nature attachment. Mitchell Thomashow introduced the term Eco-identity in his notable work “Ecological Identity: Becoming a Reflective Environmentalist” (1985). It is a way to understand how individuals perceive themselves in the natural environment. Also refers to the ways people construct their sense of self based on their experiences with nature, environmental values, and ethical considerations regarding ecological systems (Thomashow, 1995). Thomashow aims “to show how an ecological worldview can be used to interpret personal experience, and how that interpretation leads to new ways of understanding personal identity” (Pomeroy, 1995). The ability to manage Eco-emotions through cognitive reappraisal can aid in the development of shaping an individual’s ecological identity and nurturing pro-environmental behaviors. These behaviors enhance one’s environmental awareness, fostering a stronger connection to nature, which is achieved through narrative-enhanced environmental education. This enhanced method of environmental education cultivates empathy and emotional engagement effectively, leading to a deeper understanding and appreciation of nature (Yang et al., 2022). Educational method that intervenes based on empathy and emotions could have a long-lasting effect on the learners because of the ability to change an individual’s or children’s internal thinking and intrinsic motivation for environmental protection (Darner, 2010). In the study, set in a preschool context, the researchers discovered that reading picture books that foster empathy with nature is a more efficient approach to environmental activism (Li et al., 2024). Instead of factual teaching methods, stories that present environmental issues as a plot enable young learners to easily align themselves with their cognitive development (Altun, 2018). The educational method that focuses on developing empathy and emotional engagement toward nature results in the possible development of climate action. Human-nature attachments refer to humans’ innate tendency, which forms an emotional bond toward nature. Biophilia asserts that humans have a built-in innate affinity for nature and other forms of life (Kellert and Wilson, 1995). This attachment also helps to build the foundation for pro-environmental actions and one’s ecological identity for long-term environmental stewardship. As Glenn Albrecht envisions, the symbiocene is an era of positive affirmations of life that offers the possibility of the complete reintegration of the human body, psyche, and culture with the rest of life (Albrecht, 2019). The term symbiocene puts flesh on the idea of human-nature interconnectedness. Narrative-focused education can be a pedagogical pathway to achieve human-nature attachment for an individual or collective pro-environmental behavior. Figure 4 below presents a model showing how Narrative-enhanced environmental education fosters Pro-Environmental Behavior through empathy and emotional engagement. This engagement fosters three key factors: Eco-Identity (integrating environmental values into one’s self), Human-Nature Attachment (emotional bond with nature), and Empathy itself as a central emotional driver. Together, these elements motivate individuals to adopt environmentally responsible actions. The model highlights the role of storytelling in shaping identity, emotional connection, and sustainable behavior.

Figure 4. Narrative-enhanced environmental education (NEEE) and its psychological pathways to action.

Conclusion

The proposed framework integrates ecopsychology, eco-emotions, and Narrative-Enhanced Environment Education (NEEE) to form a comprehensive psycho-emotional method for fostering environmental awareness and pro-environmental behavior. As climate change and ecological degradation continue to exert psychological and emotional pressure on individuals, there is an urgent need to reimagine environmental education not just as a cognitive enterprise but as an emotionally resonant one. This study demonstrates that incorporating emotional intelligence, narrative engagement, and psychological reflection into environmental education can cultivate eco-identities, human–nature attachment, and empathy and emotional engagement, which are the three essential pillars for long-term ecological consciousness. Furthermore, the narrative method offers learners the opportunity to emotionally connect with ecological themes through story, metaphor, and memory, fostering empathy and deepening their sense of belonging in the natural world. The narrative-enhanced environmental education provides a transformation affectively. Nurturing the emotional scaffolding required to respond to environmental challenges with resilience, hope, and responsibility. The integration of storytelling, emotional regulation, and Ecopsychological awareness forms a pathway to what Glenn Albrecht envisions as the Symbiocene. A future era characterized by harmonious human-nature relationships and positive psychoterratic states. This study reaffirms the necessity of moving beyond fact-based environmental education toward a nuanced narrative-enhanced approach.

This holistic, emotionally grounded pedagogy prepares learners to act not only with knowledge but with empathy, identity, and environment-friendly action.

Author contributions

HJ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. GC: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albrecht, G. (2019). Earth emotions: New words for a new world. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Albrecht, G., Sartore, G., Connor, L., Higginbotham, N., Freeman, S., Kelly, B., et al. (2007). Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australasian Psychiatry 15, S95–S98. doi: 10.1080/10398560701701288

Altun, D. (2018). Preschoolers’ pro-environmental orientations and theory of mind: Ecocentrism and anthropocentrism in ecological dilemmas. Early Child Deve. Care 190, 1820–1832. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2018.1542385

Berry, H., Bowen, K., and Kjellstrom, T. (2009). Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. Int. J. Public Health 55, 123–132. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0112-0

Bloom, B. S., Englehart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., and Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, 1st Edn. Harlow: Longman.

Boluda-Verdú, I., Senent-Valero, M., Casas-Escolano, M., Matijasevich, A., and Pastor-Valero, M. (2022). Fear for the future: Eco-anxiety and health implications, a systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 84:101904. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101904

Bonnes, M., and Carrus, G. (2017). Environmental psychology, overview?. Amsterdam: Elsevier, doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-809324-5.05554-1

Carter, R., and Simmons, B. (2010). The history and philosophy of environmental education. Berlin: Springer, 3–16. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9222-9_1

Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., and Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Front. Psychiatry 11:74. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00074

Cianconi, P., Hanife, B., Grillo, F., Betro, S., Lesmana, C. B. J., and Janiri, L. (2023). Eco-emotions and psychoterratic syndromes: Reshaping mental health assessment under climate change. Yale J. Biol. Med. 96, 211–226. doi: 10.59249/earx2427

Corbett, J. (2021). Communicating the climate crisis: New directions for facing what lies ahead. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

Darner, R. (2010). Self-determination theory as a guide to fostering environmental motivation. J. Environ. Educ. 40, 39–49. doi: 10.3200/joee.40.2.39-49

Fang, W., Hassan, A., and LePage, B. A. (2022). “Introduction to environmental education,” in Sustainable development goals series eds W. Fang, A. Hassan, and B. A. LePage (Berlin: Springer), 3–24. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-4234-1_1

Fritsche, I., Barth, M., Jugert, P., Masson, T., and Reese, G. (2017). A social identity model of pro-environmental action (SIMPEA). Psychol. Rev. 125, 245–269. doi: 10.1037/rev0000090

Gross, J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 224–237. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224

Gross, J., and Thompson, R. (2007). “Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations,” in Handbook of emotion regulation, ed. J. J. Gross (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 3–24.

Guazzini, A., Valdrighi, G., and Duradoni, M. (2025). The relationship between connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behaviors: A systematic review. Sustainability 17:3686. doi: 10.3390/su17083686

Harasim, L. (2017). Learning theory and online technologies. Milton Park: Routledge eBooks, doi: 10.4324/9780203846933

Hungerford, H. R., and Volk, T. L. (1990). Changing learner behavior through environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 21, 8–21. doi: 10.1080/00958964.1990.10753743

Hungerford, H., Peyton, R. B., and Wilke, R. J. (1980). Goals for curriculum development in environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 11, 42–47. doi: 10.1080/00958964.1980.9941381

IPCC (2023). Climate Change 2023: synthesis report, summary for policymakers. contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. Geneva: IPCC, doi: 10.59327/ipcc/ar6-9789291691647.001

Joosse, S., Westin, M., Möckel, F., Keasey, H., and Lorenzen, S. (2023). Storytelling to save the planet: Who gets to say what is sustainable, who tells the stories, and who should listen and change? J. Environ. Plann. Manag. 67, 1909–1927. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2023.2258276

Kaplan, R., and Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 15, 169–182. doi: 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Kollmuss, A., and Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally, and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 8, 239–260. doi: 10.1080/13504620220145401

Kovács, L. N., Jordan, G., Berglund, F., Holden, B., Niehoff, E., Pohl, F., et al. (2024). Acting as we feel: Which emotional responses to the climate crisis motivate climate action. J. Environ. Psychol. 96:102327. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2024.102327

Kurth, C., and Pihkala, P. (2022). Eco-anxiety: What it is and why it matters. Front. Psychol. 13:981814. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.981814

Leimbach, T., and Milstein, T. (2022). Learning to change: Climate action pedagogy. Australian J. Adult Learn. 62:3.

Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Huang, Q., Deng, J., Deng, X., and Li, J. (2024). Empathy with nature promotes pro-environmental attitudes in preschool children. PsyCh J. 13, 598–607. doi: 10.1002/pchj.735

Martin, K., McLeod, E., Périard, J., Rattray, B., Keegan, R., and Pyne, D. B. (2019). The impact of environmental stress on cognitive performance: A systematic review. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 61, 1205–1246. doi: 10.1177/0018720819839817

Mazza, M., Di Nicola, M., Catalano, V., Callea, A., Martinotti, G., Harnic, D., et al. (2011). Description and validation of a questionnaire for the detection of meteoropathy and meteorosensitivity: the METEO-Q. Comprehensive Psychiatry 53, 103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.002

Morris, B. S., Chrysochou, P., Christensen, J. D., Orquin, J. L., Barraza, J., Zak, P. J., et al. (2019). Stories vs. facts: triggering emotion and action-taking on climate change. Clim. Change 154, 19–36. doi: 10.1007/s10584-019-02425-6

Nakano, Y., and Hondo, H. (2023). Narrative or logical? The effects of information format on pro-environmental behavior. Sustainability 15:1354. doi: 10.3390/su15021354

Ohly, H., White, M. P., Wheeler, B. W., Bethel, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Nikolaou, V., et al. (2016). Attention restoration theory: A systematic review of the attention restoration potential of exposure to natural environments. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 19, 305–343. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2016.1196155

Onyesolu, M. O., and Nwasor, V. C., Ositanwosu, O. E., and Iwegbuna, O. N. (2013). Pedagogy: Instructivism to socio-constructivism through virtual reality. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Applic. 4, 40–47. doi: 10.14569/ijacsa.2013.040907

Palmer, J. (1998). Environmental education in the 21st century: theory, practice, progress and promise. Milton Park: Routledge.

Panno, A., Carrus, G., Maricchiolo, F., and Mannetti, L. (2015). Cognitive reappraisal and pro-environmental behavior: The role of global climate change perception. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 858–867. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2162

Panno, A., Giacomantonio, M., Carrus, G., Maricchiolo, F., Pirchio, S., and Mannetti, L. (2017). Mindfulness, pro-environmental behavior, and belief in climate change: The mediating role of social dominance. Environ. Behav. 50, 864–888. doi: 10.1177/0013916517718887

Pihkala, P. (2022). Toward a taxonomy of climate emotions. Front. Climate 3:738154. doi: 10.3389/fclim.2021.738154

Pomeroy, C. (1995). Ecological identity: Becoming a reflective environmentalist, by Mitchell Thomashow. The Massachusetts institute of technology press, 1995. J. Polit. Ecol. 2, 47–51. doi: 10.2458/v2i1.20170

Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., and McEwan, K. (2019). The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 21, 1145–1167. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6

Reid, W., Mooney, H., Cropper, A., Capistrano, D., Carpenter, S., Chopra, K., et al. (2005). Millennium ecosystem assessment synthesis report. The Hague: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

Schools Council, Project Environment (1974). Land use in secondary schools. Schools Council. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?q=land+AND+use&ff1=subSecondary+Education&pg=8&id=ED073916 (accessed May 19, 2025).

Schultz, P. (2002). Inclusion with nature: the psychology of human-nature relations. Berlin: Springer, 61–78. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0995-0_4

Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 10, 221–279. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60358-5

Stanley, S. K., Hogg, T. L., Leviston, Z., and Walker, I. (2021). From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J. Climate Change and Health 1:100003. doi: 10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100003

Stapp, W. B. (1969). The concept of environmental education. Environ. Educ. 1, 30–31. doi: 10.1080/00139254.1969.10801479

Steg, L., Van Den Berg, A. E., and De Groot, J. I. M. (2012). Environmental psychology: an introduction. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Stern, P. C. (2000). New Environmental Theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 56, 407–424. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00175

Stewart, A. E. (2021). Psychometric properties of the climate change worry scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:494. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020494

Taylor, L., Watkins, S. L., Marshall, H., Dascombe, B. J., and Foster, J. (2016). The impact of different environmental conditions on cognitive Function: A focused review. Front. Physiol. 6:372. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00372

Teixeira, A., Gabriel, R., Martinho, J., Santos, M., Faria, A., Oliveira, I., et al. (2022). Pro-Environmental behaviours: Relationship with nature visits, connectedness to nature and physical activity. Am. J. Health Promot. 37, 12–29. doi: 10.1177/08901171221119089

Thomashow, M. (1995). Ecological identity: becoming a reflective environmentalist. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Tilbury, D. (1995). Environmental Education for Sustainability: Defining the new focus of environmental education in the 1990s. Environ. Educ. Res. 1, 195–212. doi: 10.1080/1350462950010206

Wang, H., Safer, D. L., Cosentino, M., Cooper, R., Van Susteren, L., Coren, E., et al. (2023). Coping with eco-anxiety: An interdisciplinary perspective for collective learning and strategic communication. The J. Climate Change Health 9:100211. doi: 10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100211

Wang, Y., and Yin, B. (2023). A new understanding of the cognitive reappraisal technique: An extension based on the schema theory. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 17:1174585. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2023.1174585

Keywords: ecopsychology, eco-emotions, environmental education, cognitive reappraisal, narrative pedagogy, pro-environmental behavior, symbiocene, human-nature attachment

Citation: J HNK and Chithra GK (2025) A psycho-emotional framework for environmental education: integrating ecopsychology, eco-emotions, and eco-narratives. Front. Educ. 10:1657999. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1657999

Received: 08 July 2025; Revised: 26 October 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Annalisa Valle, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Sara Abercrombie, Northern Arizona University, United StatesErtan Çetinkaya, Ministry of National Education, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 J and Chithra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gandhapodi K. Chithra, Y2hpdGhyYS5nYW5kaGFwb2RpQHZpdC5hYy5pbg==

Harish Nair K. J.

Harish Nair K. J. Gandhapodi K. Chithra*

Gandhapodi K. Chithra*