Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruption to education systems worldwide, and exacerbated existing challenges in the teaching profession. The dual demands of academic instruction and pastoral care placed a considerable amount of emotional burden on teachers, compounded by increased exposure to the traumatic experiences of students. This heightened risk of vicarious trauma among teachers has been underexplored, particularly in the context of Victoria, Australia, where one of the world's longest government-mandated lockdowns was implemented.

Methods:

This study builds on previous research by examining how teachers' roles and responsibilities informally evolved in response to external pressures during the pandemic. Drawing on interview and focus group data from 25 educators in public and private schools across Victoria in 2022, the findings were coded via NVIVO software version 12 and thematically analyzed.

Results:

Findings suggest that roles of educators evolved during the pandemic as their responsibilities expanded beyond academic instruction to include more pastoral care for students. This, in turn, disclosed different pathways through which educators were exposed to traumatic content from their students, families and other educators. As a result, many participants felt vicarious trauma symptoms, which is explored as various negative emotions.

Conclusion:

This study highlights the risk of vicarious trauma becoming an issue within the teaching profession. It underscores the need for further research to understand how vicarious trauma is affecting the teaching profession.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruption to education systems worldwide, forcing an abrupt transition to online learning and exacerbating existing challenges in the teaching profession (Beames et al., 2021; Van Bergen and Daniel, 2023). Teaching has long been recognized as a high-stress profession (Carroll et al., 2022), with educators navigating multiple work-related stressors, including heavy workload, time pressures, limited resources, and performance expectations. Additional challenges such as lack of support, poor work-life balance and societal pressures further contribute to strain (De Nobile, 2016; Mockler and Stacey, 2021; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2015). The pandemic amplified these challenges and introduced new ones, significantly expanding teachers' responsibilities beyond traditional academic instruction (Van Bergen and Daniel, 2023; Pressley et al., 2021; Kotowski et al., 2022).

Research indicates that the pandemic has led to a significant rise in psychological distress and trauma among young people. For example, Salmon et al. (2023) examined the psychological toll of the pandemic on young adults with a history of adverse childhood experiences. Their study of 664 individuals aged 16–21 in Manitoba, Canada, found that COVID-19-related stressors—including emotional and relational conflict, elevated stress, anxiety, and depression, increased use of alcohol and cannabis, and lack of emotional support—contributed to significant declines in mental health. In Australia, the pandemic restrictions were associated with increases in emergency department presentations for eating disorders, anxiety and self-harm among youth (Hiscock et al., 2022). This occurred against a backdrop of already substantial rates of childhood trauma and maltreatment. Mathews et al. (2023) conducted a study of 8,503 Australians aged 16 and over in 2021, that found nearly 40% of respondents reported exposure to domestic violence during their childhood, alongside significant rates of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. In addition, families experienced increased stress due to pandemic-related uncertainty, weaker social connections, and financial instability (Kaleveld et al., 2020).

The compounding stressors faced by students and families often manifested in the classroom, requiring teachers to take on additional responsibilities beyond their traditional roles. As students and families experienced increased stress and distress, teachers faced growing demands on their time and responsibilities, balancing online instruction, administrative tasks, and pastoral (emotional) care (Flack et al., 2020; Flanagan et al., 2024; Gore et al., 2021). This shift required teachers to conduct more frequent check-ins with families, provide intensive emotional support for students, and prioritize connection over academic instruction—sometimes feeling more like crisis management or babysitting rather than teaching (Van Bergen and Daniel, 2023; Flanagan et al., 2024). The dual demands of academic instruction and pastoral care placed a considerable emotional burden on teachers, with research indicating that students' social isolation and decreased wellbeing were key sources of concern and anxiety for educators (Flack et al., 2020). Teachers faced heightened emotional strain from continual exposure to students' distress—an experience that aligns with vicarious trauma, a phenomenon where repeated exposure to others' suffering leads to emotional exhaustion and psychological distress (Joubert et al., 2013; Hydon et al., 2015). The cascading effects of these stressors have significantly impacted teacher mental health and wellbeing (Billett et al., 2023), with the rapid shift to online teaching during the pandemic exacerbating workload, role complexity, anxiety, and burnout among teachers (Van Bergen and Daniel, 2023; Pressley et al., 2021; Kotowski et al., 2022). The impacts from these stressors are still being felt in the post-pandemic period (Ha et al., 2025).

This expanded supportive role, combined with repeated exposure to students' and families' distress, intensified the risk of vicarious trauma among teachers. While prior research has documented the immediate challenges teachers faced during the pandemic's early phases, less is known about how sustained role and responsibility expansions combined with increased indirect exposure to trauma have affected teachers' wellbeing following the pandemic. The prolonged disruptions in Victoria, Australia—which endured the world's longest mandated lockdown (McLaren et al., 2024) —likely intensified these pressures, yet little is known about the psychological effects on teachers. To better understand the effects of these role shifts and stressors, this study builds on existing research (Van Bergen and Daniel, 2023; Berger and Nott, 2024; Oberg et al., 2023; Ormiston et al., 2022) by examining teachers' experiences in Victoria through and following the COVID-19 public health restrictions, focusing on two broad research questions:

-

(1) How did the teachers' roles and responsibilities evolve during and after the government mandated restrictions, and how did these changes influence their exposure to traumatic content?

-

(2) To what extent were teachers exposed to traumatic content during and after the government mandated restrictions, and how did this exposure affect their mental health and professional wellbeing?

By addressing these questions, this study contributes to the literature on the enduring effects of pandemic-related role changes and extends current understandings of vicarious trauma in teaching, providing crucial insights for developing effective support strategies and ensuring the sustainability of the teaching profession in the post-pandemic period (Ha et al., 2025; Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited, 2023; Brandenburg et al., 2024).

Vicarious trauma in teachers

The adverse impacts of vicarious trauma have been well documented. The most significant is the negative shift in thinking and behaviors affecting overall worldview (Pearlman and Saakvitne, 1995; Molnar et al., 2017). Additional vicarious trauma symptoms fall into three broad categories that overlap considerably with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): intrusive thoughts, avoidance behaviors and negative changes in mood (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Vicarious trauma differs from PTSD in both its cause and manifestation because it arises from indirect exposure to others' traumatic experiences and develops cumulatively (Pearlman and Saakvitne, 1995). Because of these defining characteristics, vicarious trauma is a silent hazard in the workplace.

Originally identified in therapists (Pearlman and Saakvitne, 1995), vicarious trauma is now recognized as a risk in professions requiring prolonged empathy based engagement with trauma. Nurses are at high risk, for example, because they empathize with patients while often witnessing their distress (Isobel and Thomas, 2022; Wu et al., 2024). Similar risks are evident for social workers (Ashley-Binge and Cousins, 2020), justice personnel (Iversen and Robertson, 2021) and researchers (Moran and Asquith, 2020). The unprecedented challenges faced by teachers during and after the pandemic restrictions, namely the increase in student distress and role expansion, created conditions analogous to those identified in professions with recognized vicarious trauma risks. Despite this risk profile, the research on vicarious trauma in teachers is scant.

Given the conceptual overlap between PTSD and vicarious trauma, PTSD incidence can demonstrate as a proxy indicator for vicarious trauma (Lerias and Byrne, 2003). A mini meta-analysis completed during the pandemic revealed approximately 11% of teachers exhibited PTSD or symptoms consistent with PSTD (Idoiaga Mondragon et al., 2023). The majority of the studies included in the meta-analysis were carried out in China (four) and Bulgaria (one), including two studies on university teachers, two on school teachers and one examining all teachers. These findings suggest teachers may indirectly experience their students' trauma, resulting in emotional, physical and cognitive responses (Idoiaga Mondragon et al., 2023). Thus, research suggests that teachers, with growing exposure to student trauma through expanded role expectations (Van Bergen and Daniel, 2023; Flanagan et al., 2024), increased disclosures and the rising prevalence of mental health challenges (Hiscock et al., 2022), may be at risk of vicarious trauma.

To understand the psychological toll of teaching during the pandemic, it is useful to examine related constructs that overlap with vicarious trauma and offer insights into how empathy-based stress manifests across professions, including education (Rauvola et al., 2019). For example, compassion fatigue describes the physical and emotional exhaustion experienced by professionals after prolonged, continuous and intense exposure to others' distress (Figley, 1995). In comparison, secondary traumatic stress focuses on the immediate and acute stress reaction that is caused by the knowledge of a traumatic event experienced by others (Figley, 1999). These concepts and vicarious trauma are often researched alongside burnout, a term broadly used to describe a state of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion from prolonged exposure to stress (Hydon et al., 2015; Freudenberger, 1974). Previous research on these constructs in educational settings provides a foundation for examining educators' pandemic experiences and the impacts of empathy-based stress on the profession.

Educational research examining the impact that trauma-exposed students have on teachers points to a high risk of compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress and burnout among teachers (Berger and Nott, 2024; Oberg et al., 2023; Ormiston et al., 2022; Oberg et al., 2024). Oberg et al. (2024) investigated educator wellbeing in Australian teachers. To understand the current prevalence of compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress and burnout, the researchers surveyed 1,612 participants using the Professional Quality of Life Survey (ProQOL). The highest percentage of teachers was classified as experiencing moderate levels of burnout (46.96%), secondary traumatic stress (41.50%) and compassion satisfaction (42.56%).

Other studies have also found that secondary traumatic stress is experienced by Australian teachers. Fraser et al. (2024) conducted a mixed methods study to understand the extent of secondary trauma on educators and found that 38% of 2,285 survey participants experience secondary traumatic stress often or very often. Alarmingly, 40.1% of educators rated their exposure to secondary trauma at work an 8 or more out of 10, which is considered to be high or very high. Other educational research has focused on burnout in teachers and the factors associated with the cause of burnout. As part of Oberg et al. (2024) study, it also investigated burnout as a construct of compassion fatigue in Australian teachers. The study suggests that burnout and secondary traumatic stress contribute to compassion fatigue and can severely impact the teacher's ability to connect with their students. Highlighting the importance of considering teacher trauma training, this study found that the more confident the teachers felt in their abilities, the less likely they were to experience burnout, reducing the risk of emotional exhaustion in teachers.

A number of contributing factors were identified when looking at the educational research examining the impact trauma-exposed students have on teachers. For example, Berger and Nott (2024) conducted an online survey with 302 Victorian teachers from both regional and metropolitan areas. The study found teachers with a personal history of trauma in conjunction with an exposure to student trauma predicted burnout, compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress. Oberg et al. (2023) drew on established literature on compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress and burnout, and found a lack of trauma-specific training in combination with the role complexity experienced during COVID-19 compounded the effects of traumatic content in teachers.

Given the documented surge in student distress and trauma during the pandemic, combined with teachers' expanded responsibilities and the high prevalence of empathy-based stress in educational settings, examining vicarious trauma among teachers during this period is critical for understanding the full psychological impact the pandemic has had on the teaching profession. This research aims to understand the unique challenges faced by educators by exploring how teaching roles and responsibilities evolved during and after the COVID-19 public health restrictions in Victoria, Australia through the lens of vicarious trauma.

Materials and methods

Study design

The research was undertaken in Victoria, Australia, in 2022. The study emerged from the first author's interest in educational wellbeing and an identified gap in understanding pandemic-era changes to teaching conditions. Research questions were shaped by the second, third and fifth authors' concurrent research on vicarious trauma in other professions. The study design builds on similar studies exploring mental health in schools (Giles-Kaye et al., 2023; Levkovich, 2020). A qualitative approach using interviews and focus groups was undertaken to understand, describe and interpret human behaviors and the meanings individuals make of their experiences (Levkovich, 2020; Creswell and Poth, 2017). A case study method provided an in-depth account of events and experiences, offering insight into the social dynamics within the practice-orientated field of education (Meyer, 2000; Merriam, 1998).

Ethical mitigation

Human ethics approval was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee via written and verbal consent. Department of Education and Training ethics was not applicable as data was collected at more than one school. Participant wellbeing was at the forefront of every interaction. Following ethical guidelines of autonomy, justice, integrity and competence each participant was issued with an explanatory statement which included, an introduction to the research, possible benefits and risks, confidentiality clauses, an explanation of the storage of data and the contact details for support services in case of participant distress. Further, participants were reminded that their participation is voluntary and they could withdraw from the research at any time.

The focus groups were held on the respective school's property and each participant was given an explanatory statement. The interviews were held via zoom and each participant was given an explanatory statement. At the start of the focus groups and interviews, researchers asked participants to provide verbal consent, confirmed the session would be audio recorded, and discussed confidentiality parameters. Participants were informed that while researchers would maintain confidentiality, the group nature of the discussion meant absolute confidentiality could not be guaranteed. Accordingly, all participants were asked to respect privacy of information shared. To mitigate any risks or harms, participants were read out the following statement before the start and at the end of the focus groups and interviews:

“If the topics discussed in the focus group cause you discomfort, please contact your workplace Employee Assist Program, your general practitioner or Lifeline (13 11 14).”

Research team and reflexivity

Both first and second authors conducted the interviews and focus groups, and coded and analyzed the data. The first and second authors are outsiders of the research population (Dwyer and Buckle, 2009), and identify as women. The first author is an early career qualitative researcher, who currently researches injury prevention. The second author holds a PhD and has more than 10 years of experience as a qualitative researcher. These professional experiences shaped researchers' biases, assumptions and approaches to conducting analyses, with the first author being through the education system more recently and the second author having more of a retrospective view. As outsiders to the research population, both authors were aware of the potential for their positionality to influence data collection and interpretation. Throughout the research process, both authors engaged in reflexive practices, such as keeping reflective journals and regularly discussing their perspectives and assumptions with each other. This reflexivity helped to identify and mitigate potential biases, and to ensure that the voices and experiences of participants were represented as authentically as possible. The authors also considered how their gender and professional backgrounds might shape interactions with participants, the framing of questions, and the interpretation of findings, and took steps to remain open to alternative interpretations and to seek participant validation where possible.

Sampling and recruitment

Three schools were identified that represented diversity in location, sector (government and private), socio-economic status (SES) and student age ranges (primary and secondary) (Chatters et al., 2024; Shea et al., 2022). However, one of the schools, a metropolitan public primary school, withdrew due to pandemic-related constraints. The first author contacted and met with principals at both schools to explain the research and participation requirements. These meetings secured institutional support and formal agreement for school participation.

Initially, a purposive sampling strategy was implemented to recruit teacher participants (Bryman, 2016; Liamputtong, 2009). However, due to recruitment challenges, a snowball sampling approach was subsequently adopted (Bryman, 2016). Selection criteria for participants included being employed as an educator between 2020 and 2021, which included school teachers, leaders, teacher aides as well as wellbeing counselors due to their regular student interactions.

Participating schools included: School A, a private regional primary and secondary school with 150 teaching staff; and School B, a metropolitan public primary school with 36 staff, adding leadership perspectives. Educators from Schools A and B were invited to participate in a focus group via an email from their respective school wellbeing officers. After the focus groups, the research team distributed an invitation to participate, encouraging focus group participants to share it with their contacts to be interviewed individually. The invitation was also circulated on social media platforms, including the Teach for Australia Facebook page. The recruitment period went from 14/03/2022 to 17/06/2022.

School demographics and characteristics

Schools A and B cover a broad range of SES status' from 5 (most advantaged) to 1 (most disadvantaged). Schools A and B represented diversity across key demographics including:

-

- Most and least advantaged SES status

-

- Public and private sector

-

- Metropolitan and regional locations

-

- Primary and secondary age group

To maintain anonymity, only general demographic characteristics are reported.

Participant demographics and characteristics

The study included 25 participants with varying years of teaching experience, ages and representation from both private and government schools (Table 1). The group comprised of 6 male and 17 female participants. The years of teaching ranged from 2–40 years and age of educators ranged from 20s−60s. Nineteen participants identified as primarily teachers, three as teachers with additional wellbeing responsibilities, one as a teacher's aide and two as having a leadership position. Table 1 shows the demographic data that was collected from participants.

Table 1

| Demographic | % of total number of participants |

|---|---|

| Age range | |

| 20 s | 12% |

| 30 s | 40% |

| 40 s | 20% |

| 50 s | 16% |

| 60 s | 12% |

| Unknown | 0% |

| Years teaching | |

| 0–5 | 28% |

| 6–11 | 28% |

| 12–20 | 16% |

| 20+ | 24% |

| Unknown | 4% |

| Student cohort | |

| Primary school | 52% |

| Secondary school | 32% |

| Specialist school | 12% |

| Both primary and secondary school | 4% |

Demographics of participants.

Data collection

Data collection involved three focus groups with 17 participants from Schools A and B and eight online semi-structured interviews. Focus groups were chosen as a method of data collection as they create context for the researcher as complex behaviors or motivations can be explored in dialogue (Litosseliti, 2003; Morgan, 1993). Two 45-min focus groups were held at School A during lunchtime with six participants each, and one 90-min focus group at School C after school with six participants. All sessions were conducted in English, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

Interview participants included an educator who could not attend the arranged times of the focus groups, educators who contacted the research team after seeing the social media post about the project, and educators who contacted the research team because they learned about the project from another educator. Semi-structured interviews help the researcher better understand participants' opinions and experiences (King and Hugh-Jones, 2018). Interviews were conducted online via Zoom and lasted approximately 45 min.

A series of predetermined open-ended questions and prompts addressed the following topics: job satisfaction and school support, mental health at work, hearing of traumatic stories, and knowledge of vicarious trauma. For example, under the topic: mental health at work, participants were asked, “How do you speak about mental health at your workplace?” to understand if the participant had a supportive workplace/environment, which is a protective factor for vicarious trauma. And, “How often and in what ways do you engage with traumatic content at work?,” to understand their experiences with traumatic content. Focus group and interview questions were informed by the literature and concurrent research on vicarious trauma conducted by the third author. Facilitators reiterated the support services available to participants before and after data collection.

Data analysis

The first and second authors conducted two data analysis phases aligning with thematic analysis principles (Braun and Clarke, 2021). Data were analyzed inductively via NVivo 12 software using reflexive thematic analysis. Themes were identified from the data.

In the first phase, the lead author read the scripts multiple times to familiarize themselves with the data. They identified main themes and central ideas and generated initial codes, such as interaction with traumatic content, type and amount of support services and not having a clear job description. Discussions about the first phase of analysis were formative to the authors' collective understanding of the teachers' perspectives and helped the authors navigate ideological and epistemological differences as they made sense of the data (Paris and Winn, 2014). This process helped them to debate and understand emerging themes.

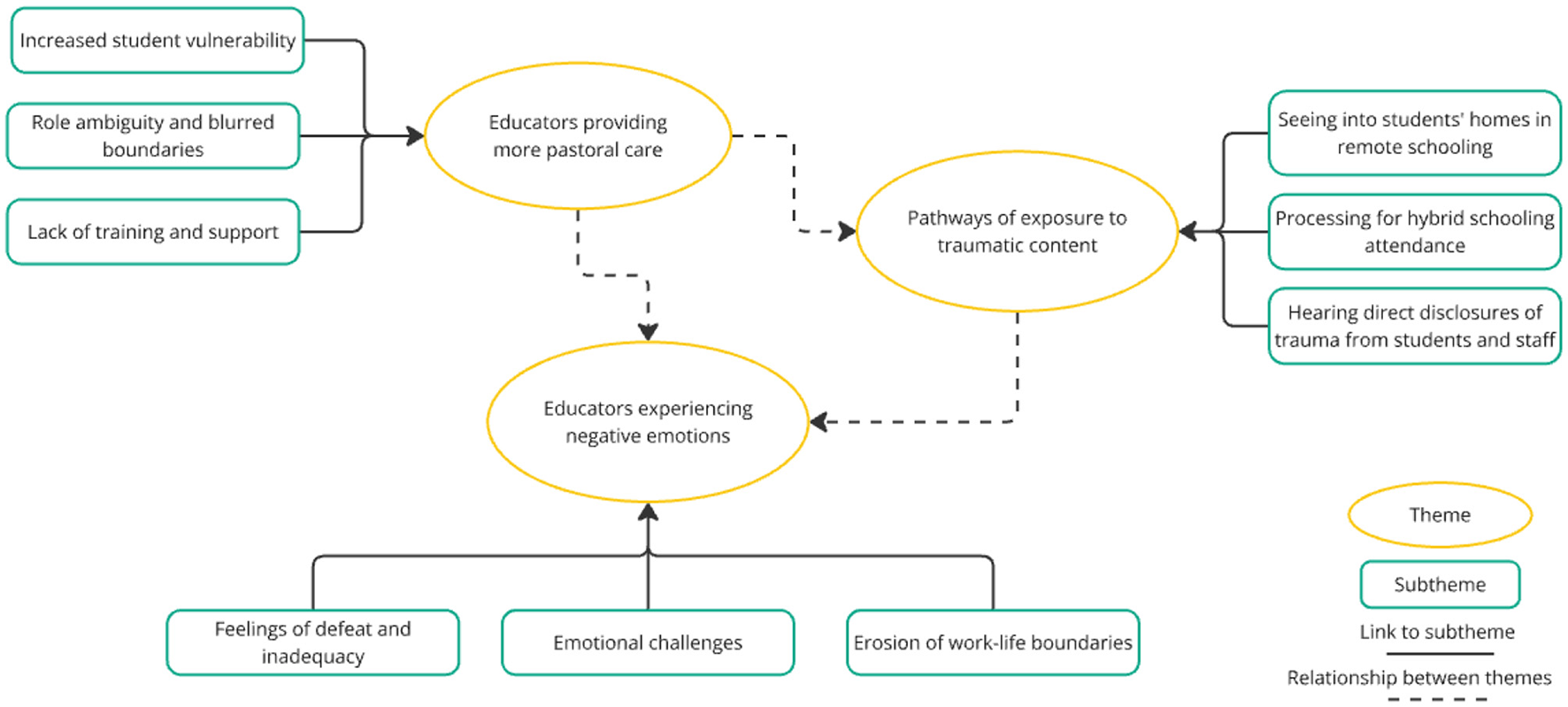

In the second phase and to support rigor, the first and second authors examined the initial general themes that emerged from the first phase and established a connection (similar or different) across all interviews and focus groups and within the literature. As per steps four and five in Braun and Clarke's (2021) reflexive thematic analysis principles, themes were reviewed, defined and coded via naming. The analysis yielded three key themes and nine subthemes, each connected to specific aspects of the research questions. For example, the theme of “educators providing more pastoral care” was supported by the subthemes of “increased student vulnerability,” “role ambiguity and blurred boundaries” and “lack of training and support.” By centring teachers' perspectives, this reflexive analysis provided a comprehensive view of how teachers' experiences align with and expand upon the research objectives.

Results

The key themes and their associated subthemes are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Key themes (circles) and related subthemes (squares) from focus groups and interviews.

The findings focus on three key themes. The first theme is the evolving role of educators, as their responsibilities expanded beyond academic instruction to include greater pastoral care for students. The second theme examines the pathways through which educators were exposed to traumatic content. Finally, the third theme explores the negative emotions educators experienced as a result of both.

Theme 1: educators providing more pastoral care

Increased student vulnerability

Participants consistently highlighted how the increased vulnerability of students required them to take on greater pastoral care responsibilities, often at the expense of their ability to focus on educational instruction. Educator J reflected on the evolution of teachers' responsibilities, stating,

“I think over the last 10 years or so the fact that – or even the last five years, we're more expected as teachers or as educationalists to take on – to understand trauma of children and their families, and then how we deal with that very differently to maybe what we did 15 years ago when we had less understanding of it.” (Educator J)

Building on this reflection, Educator I described how addressing students' basic social skills and behaviors had become a primary focus of daily routines, often disrupting academic instruction:

“Because right now, you're trying to teach them how to have respect, have manners with please and thank yous. How to not push through a door when someone's trying to get in or out of a room. Like, real basic stuff. You're doing all of that before you even start to teach, and then that takes time, and then this is why, and it's rippling into then I'm not teaching the content that I need to get through in this lesson because I'm dealing with all that shit. And then it keeps day in, day out. It's from year five to year 11.” (Educator I)

The Victorian government's shift to remote and hybrid schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic further intensified these growing demands on teachers. While ensuring education continuity, this transition also exposed and exacerbated challenges for many students. As Educator J explained, students previously identified by their schools as vulnerable faced heightened risks as families struggled with growing economic pressures and isolation:

“…the further through the pandemic experience we went, and I say that and we're still in it, but in terms of the periods of remote learning and strict lockdowns, the further through that you could see the pressure intensify for people falling into that category of vulnerability, there was so much distress that was present and becoming ever more present.” (Educator J)

Participants reported an increase in the overall number of vulnerable students and a significant escalation in the intensity of their needs. Educator D observed, “…there are more kids presenting more needs. And the behaviors of some of the students coming back to school are more escalated more often.” Many students also struggled with conflict resolution and social reintegration after prolonged isolation:

“And the kids too, they're probably copping the negativity at home with parents fighting with financial issues or all that stuff, and then they come into school and not only have they missed so much learning, but that social interaction, they're copping conflicts left, right and center from their friends because they can't resolve anything.” (Educator L)

Participants described how some students struggled to manage pressures at home and school, which they attributed to a lack of resilience. Educator Z reflected on students' difficulty coping with challenges:

“I noticed that students, they're so not resilient. They crumple as soon as something gets too hard and they walk away from it. So, they don't have the ability to keep trying and failing, but keep trying. It's just that's too hard… Like, the meltdowns, seriously. It's like, ‘Can you guys stop for a minute and have a look at the way you're behaving?”' (Educator Z)

Role ambiguity and blurred boundaries

As students' emotional and social needs grew, teachers struggled with a lack of clarity about their responsibilities and uncertain role boundaries. Educator E described how these shifting expectations blurred the lines between home and school:

“I feel like the home and school boundaries are blurred a lot more… so teachers were expected to check in with the students and not just in their allocated periods throughout the week. It's become this holistic mode now where we need to make sure that we're looking after the students' mental health sometimes even more than we are their academics.” (Educator E)

Some educators sought to set personal boundaries to navigate these challenges, balancing care for students with an awareness of their own professional limitations. Educator D emphasized the importance of clarity in teachers' roles:

“I think it's quite important to draw a not-too-hard-and-fast line in the sand, but offer support and offer care without inflating my ability to help them as a health care professional. And without confusing the role of a teacher, which is already quite versatile.” (Educator D)

Lack of training and support

While teachers were increasingly expected to provide emotional support, many felt unprepared and unequipped due to a lack of training and guidance. A participant in a wellbeing role highlighted this concern, noting that many teachers were expected to manage student mental health issues despite lacking the necessary training:

“…they didn't have the experience that wellbeing [teachers did], because we are dealing with it every day… So, a lot of them were really, really concerned about the mental health of a lot of their students. So, they were definitely not equipped to engage with that.” (Educator A)

Participants emphasized the difficulty of navigating these challenges without adequate support. For example, Educator W said, “…And if [students] come to you with problems, I tend to just pass them onto the leader, because I'm not really equipped to deal with it”. Beyond the absence of formal training, participants also highlighted gaps in leadership support following difficult encounters with students. Educator A reflected on how senior staff often lacked the necessary skills to provide meaningful support to teachers:

“I definitely think there's a real lack of training of senior people in schools on how to engage with that [teacher] after that point [an incident]. And those structures of not being able to take a lesson off sometimes… or following up for the two weeks [after an incident with a student/family]. But that's in replacement of true support, really… How can we expect our teachers to know what to do when a situation arises?” (Educator A)

Many educators felt this lack of support took a toll on their wellbeing, particularly as they struggled with the emotional burden of student trauma without clear institutional guidance. Educator E explained, “Leadership don't give us do's and don'ts on how to help these students, and COVID really showed this.”

Theme 2: pathways of exposure to traumatic content

Seeing into students' homes in remote schooling

Participants described how their expanded roles brought them into closer contact with students' personal challenges and family crises, particularly during remote and hybrid learning. One significant source of trauma exposure was the unfiltered view into students' home environments during remote teaching, which revealed family dysfunction, poverty, and other distressing circumstances:

“A student of mine, his mum had been diagnosed with terminal cancer. His dad had just had a stroke. There were also visa issues. So, a lot going on for this young man and his family, and I saw all of this from my living room.” (Educator A)

Other educators similarly described the emotional toll of witnessing student hardship. Educator I recalled, “I was also doing catch up tutoring, and a lot of the students in there were victims of trauma from the lockdown. It was really sad for me to see.” Educator C expressed frustration with the emotional distance created by online learning, “I hated the online [teaching]. The kids felt so far away from me.”

Processing for hybrid schooling attendance

Hybrid teaching, which combined in-person instruction for vulnerable students and children of authorized workers with remote learning for others, created another pathway for trauma exposure. Educators noted that the process of identifying and supporting vulnerable students required direct engagement with families, many of whom disclosed distressing stories.

“I noticed even with families, in the processes that we were expected to follow to book children in for essential workers, but also to bring in forcibly those children that were classed as being vulnerable, it meant that we [educators] were more exposed to the presentation of trauma or traumatic stories and events based on the processes that we had to implement.” (Educator K)

“…[parents or guardians] had to bring their kids in [to school] because there was domestic violence situations occurring in their home, or similar. So, we were the constant point of contact, and as the staff cycled through that care…” (Educator J)

Hearing direct disclosures of trauma from students and staff

Beyond witnessing hardship through remote and hybrid learning, educators also faced increased direct disclosures from students seeking support. Participants recalled stories of family violence, neglect, financial hardship, addiction, and mental health struggles. For example, Educator Y shared, “I've had one incident where a student told me she had bruising from a parent.” Similarly, Educator F recalled, “I had a boy show me all cuts up his arms. That's something I distinctly remember. So, I was a bit shaken by that.” While Educator I commented, “She told me her boyfriend had smacked her and [she] needed some advice on how to tell her parents.” Exposure to trauma was not limited to student disclosures; educators also shared distressing stories with one another, reinforcing the emotional burden, “The stories [colleagues] would tell me were sort of hard to believe because they were so traumatic” (Educator B).

While some educators were accustomed to handling traumatic content in their roles, participants noted the pandemic and lockdowns increased the volume and severity of such encounters. Educator D shared, “I'd say lockdown exacerbated [traumatic content], maybe, but we were already burning out by then anyway.” Several participants described the overwhelming regularity of trauma exposure, particularly those working in wellbeing roles:

“How often? I don't think it would be an exaggeration to say every day. That would be a bit skewed because I worked in wellbeing. I would say as a teacher, it would be at least once or twice a week and in wellbeing, every day.” (Educator A)

“…every day, they were subjected to it over and over and over again, and whilst there was a lot of support and camaraderie it's still something that you can't wash it off, you carry it with you.” (Educator J)

The cumulative exposure to traumatic content, combined with increased pastoral care demands, resulted in heightened emotional distress among educators.

Theme 3: educators experiencing negative emotions

Feelings of defeat and inadequacy

Participants discussed feeling overwhelmed by the unpredictable and relentless teaching environment, particularly as they navigated increasing emotional demands. For example, Educator M reflected on this challenge:

“And we're used to being good at our work. We're used to being able to do it. We're used to being able to fix it, and when you can't it's a real gut reaction. And it's hard to feel fully satisfied when the rug is being pulled out from underneath you at any turn whether it is you've got people away, you can't get relief teachers, you've got kids dropping with COVID, and then you've got more, more, more, just more accountability, you've got all this stuff to do.” (Educator M)

Educator A emphasized the emotional toll of repeated exposure to student trauma, describing how teachers had little opportunity to process distressing disclosures:

“Student tells you something really terrible, you bottle it up, you move on, you teach your next class. The next student tells you something terrible, you bottle it up, you move on, you teach next class. You've got a pile of marking. You've got a pile of planning. And then, eventually it will get too much and you will burst, whatever that looks like for you.” (Educator A)

Many participants reported feeling inadequate when responding to student trauma, often worrying that they might unintentionally worsen students' problems by failing to provide “the correct advice” (Educator X). This sense of inadequacy was frequently linked to a lack of comprehensive training in handling complex trauma, leaving educators feeling unqualified and “not right for the job” (Educator I). Educators also described a lack of institutional support, which compounded these challenges. As Educator E explained, many teachers struggled with the emotional toll of student trauma without adequate guidance or resources:

“I've got many friends who are in different schools who absolutely don't have support within their schools, and their mental wellbeing has absolutely suffered over their teaching career. That's been really sad and really hard to grasp…” (Educator E)

Emotional challenges

Reflecting on the emotional impact of these challenges, Educator M described their state as “…turmoil. I'd tell my [partner], I can't do this anymore.” Over half of the participants spoke openly about heightened anxiety and hypervigilance, reporting increased emotional distress while managing student trauma. For example, Educator C stated, “I ended up going to the toilet and was just crying…I take on a lot on a lot of how they [students] are feeling sometimes.” Similarly, Educator A noted how exposure to student trauma heightened their awareness of distress in their personal life, stating they were “hypervigilant of what friends and family were going through at that time.”

Participants also reported heightened stress and concern for students' safety during remote learning. Many described feeling unsettled when students failed to log in for online classes. As Educator Z explained, “…if a student didn't log in online to a particular lesson over that lockdown period… my first thought went to, ‘I need to know where are they? Why are they not in class?” Educator F shared similar concerns, “I think it was definitely more intensive in lockdown. And if they're not at school, if they're absent, okay, why has this kid been absent for four days straight, what's going on here, you know?” Suicide emerged as a recurring and deeply distressing issue, with some participants recounting the emotional impact of losing a student. Apart of this heightened stress was re-experiencing student trauma. Educator I described feeling “like a wreck” when their students sought comfort after a tragic event, saying, “I still think about it! It doesn't ever leave you.” Re-experiencing also resulted in sleep disturbances, with Educator J waking at 3 a.m. from worry, Educator A dreaming about students, and Educator B acknowledging, “sometimes you have sleepless nights, for sure.”

Erosion of work-life boundaries

The emotional challenges from the job also extended into participants' personal lives, often affecting their behavior with loved ones. Educator C described how heightened empathy influenced their interactions with family, constantly checking up on them, stating “You don't even realize you're doing it.” Similarly, Educator J stated, “I think you are starting to take that [trauma] home a lot more, and you're thinking about it a lot more.” Educator Y provided a detailed account of how exposure to trauma lingers:

“I think [student trauma] is one of those things that you do take home with you. And I guess it doesn't just go away, and one thing happens and it's solved. But it's usually something that I'll either try to speak with my partner about it, or you sit there in bed at night thinking about it before you fall asleep. But then I guess eventually it fizzles away, and hopefully is resolved. But you don't always get that closure. So, in that case, I think it's just time, and it dissolves, and something new comes up and takes priority.” (Educator Y)

Discussion

This study sought to understand the experiences of educators during and after the COVID-19 public health restrictions in Victoria, Australia. It focused on changes to roles and responsibilities and the extent educators were exposed to traumatic content. These findings illustrated that during the most intense periods of the COVID-19 pandemic, which included COVID-19 containment measures such as government mandated stay-at-home orders, educators' roles were reshaped. This reshaping included expanded pastoral care responsibilities. The result of this role expansion was educators experiencing increased exposure to new pathways of traumatic content, which lead to heightened emotional distress. Findings revealed this phenomena continued after the public health restrictions were lifted. To better understand the cumulative impact of these changes, the discussion will examine these findings through the lens of vicarious trauma.

Prior research has established that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased trauma exposure among students (Salmon et al., 2023; Hiscock et al., 2022). Educators in this study confirmed this trend, reporting that previously identified vulnerable students became more at risk of a negative change in mental health status, while some students not previously considered vulnerable were newly categorized as such. Consistent with research on complex and challenging behaviors in children and young people (Macnamara, 2020; Greeson et al., 2014), participants described difficulties managing trauma-related behaviors while simultaneously addressing students' emotional needs.

As students' mental health and social challenges intensified, so did teachers' pastoral care responsibilities, often at the expense of instructional time. Educators described spending significant portions of their day addressing students' emotional regulation, behavioral issues, and interpersonal conflicts, which detracted from their ability to deliver academic content. Some educators expressed frustration that their role had expanded beyond education to include responsibilities typically associated with counseling and crisis intervention. This aligns with Klusmann, Aldrup (Klusmann et al., 2023) and Kupers, Mouw (Kupers et al., 2022), who found that teachers' workloads significantly increased during the pandemic due to rising pastoral care expectations. Significantly, our findings revealed that the expanded pastoral role assumed by teachers during the pandemic had not returned to pre-pandemic levels. Despite the formal end of lockdowns and return to traditional classroom settings, participants consistently reported remaining in an intensified caregiving role, with one participant summarizing this ongoing reality as 'we're still in it.' This suggests that the crisis-driven role expansion has become entrenched as a new baseline expectation rather than a temporary adaptation. This is particularly concerning given the increased exposure to traumatic content associated with the pastoral care role.

Educators identified multiple pathways through which they were exposed to traumatic content, many of which intensified during lockdowns and continued after restrictions were lifted. Remote and hybrid learning provided an unfiltered view into students' home environments, while regular engagement with distressed families as part of arranging hybrid schooling further immersed educators in trauma narratives and crisis situations. During and beyond the immediate pandemic environment, direct disclosures from students regarding trauma increased, leaving teachers to navigate difficult conversations and determine appropriate responses. Further, colleagues also played a role in reinforcing an emotionally charged work environment, as teachers frequently shared distressing student cases with each other. While intended as peer support, this regular exchange of traumatic content contributed to a workplace culture saturated with secondary exposure to trauma.

This study's findings on digital, school-based, and peer exposure pathways, combined with evidenced intensification of exposure, contrast and extend the existing literature in significant ways. For example, Goudarzi, Hasanvand (Goudarzi et al., 2023) conducted a study in a university context, which found that there was a reduction in interpersonal interactions between teachers and students and an increase in the quality of education during the pandemic, via e-learning. Conversely, the results of the present study was the confirmation of the educator's role in trauma narratives. These contrasting findings could highlight the difference in duty of care among university and school-based educators and how this impacts wellbeing. Despite these differences, this current study's identification of technology and peer mediated exposure to trauma and its impacts, adds a critical dimension to understanding trauma transmission mechanisms among educators. Furthermore, beyond the novel sources of traumatic exposure, the current findings highlight the continued significance of non-COVID-specific exposure pathways that remain embedded within teachers' expanded pastoral roles. Such findings suggest teacher-to-teacher transmission of traumatic content and direct student disclosures represent enduring occupational specific hazards that extend well beyond the pandemic's acute phase. The persistence of these exposure pathways, coupled with the sustained nature of role expansion, may contribute significantly to the current crisis in teacher retention and wellbeing documented across educational systems, see Cuervo and Vera-Toscano (2025), who investigated the key factors driving teachers to leave the profession.

Participants provided clear evidence that the changes necessitated by COVID-19 impacted teacher wellbeing through increased exposure to traumatic content. Educators reported experiencing heightened stress, sleep disturbances, and intrusive thoughts related to their students' trauma. Some noted that the impacts extended beyond the classroom, affecting their personal relationships and interactions with family members. Furthermore, participants also described a shift in their overall worldview, one of the most defining symptoms of vicarious trauma (Pearlman and Saakvitne, 1995; Molnar et al., 2017; Rauvola et al., 2019). Some reported becoming hypervigilant about student safety, worrying about students outside of work hours, and struggling to detach from distressing cases. The increasing emotional toll was particularly evident in cases where teachers had to intervene in student crises, including cases of self-harm and suicidal ideation. This constellation of symptoms is consistent with vicarious trauma theory that posits prolonged exposure to others' distress can lead to changes in self-perception, emotional regulation, and cognitive functioning (Pearlman and Saakvitne, 1995) and suggests the pandemic context created heightened risk for teachers. Research on the teaching profession supports such findings. For example, Hydon et al. (2015) and Joubert et al. (2013), emphasized that teachers in crisis intervention roles are at heightened risk of developing vicarious trauma symptoms. Furthermore, the documented persistence of symptoms 2 years post-pandemic suggests that teachers are experiencing sustained stress and risk; a finding consistent with Ha et al. (2025), who reported that many teachers are still reporting high levels of burnout post the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2021) and into 2022.

Interestingly, this study found insufficient resources and lack of institutional support contributed to risk of vicarious trauma among participants. Unlike trained trauma professionals such as psychologists and social workers, teachers rarely receive formal training in trauma processing, debriefing, or emotional self-regulation (Oberg et al., 2023). The findings showed, without adequate training or institutional support, participants were left to manage these emotionally challenging experiences on their own, increasing their vulnerability to burnout and long-term psychological strain even after the pandemic's height. This cumulative burden aligns with findings from Oberg et al. (2023), who highlight that teachers—unlike trained trauma professionals—receive little to no guidance on processing secondary trauma. This finding presents a critical opportunity for educational systems to develop and implement targeted and proactive interventions and trauma-informed supports specifically designed to mitigate vicarious trauma risks among teaching staff.

Collectively, the findings from this study build on previous research examining empathy based stress in teachers (Van Bergen and Daniel, 2023; Berger and Nott, 2024; Oberg et al., 2023; Ormiston et al., 2022), by demonstrating the cumulative impact the multiple pandemic-related role changes had on teachers. By documenting the vicarious trauma risk factors – sustained caring responsibilities and cumulative exposure to traumatic content – and symptomology consistent with vicarious trauma, the findings highlight vicarious trauma as a valid and useful conceptualization of educators' exposure to traumatic content beyond the symptoms of compassion fatigue and burnout. This re-conceptualization combined with the enduring nature of the widely document role expansion has significant implications for teachers' ongoing exposure risks, as they continue to manage complex student mental health presentations without commensurate increases in professional support or training.

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. Participation bias may have occurred due to the opt-in recruitment process. Teachers who volunteered may have had greater exposure to traumatic content or experienced higher levels of work-related stress than those who did not participate, potentially limiting the findings' representativeness of the broader teaching population. Additionally, recall bias is a concern, as participants were recalling experiences spanning more than 2-years. The sampling techniques, including purposive and snowball sampling, may have also introduced biases. Snowball sampling could have led to participant homogeneity, potentially underrepresenting isolated individuals or those with differing perspectives. This may limit the generalisability of the findings to the wider teaching cohort.

The inclusion of teacher aides and school wellbeing counselors alongside classroom teachers and leadership may have introduced variability in the findings. These roles likely experienced different levels of exposure to traumatic content and student behaviors, as well as differing coping mechanisms. However, as 19 of 25 participants identified primarily as classroom teachers, this limitation is somewhat mitigated.

Longitudinal studies are particularly needed to examine the long-term mental health impacts of trauma exposure on teachers and identify risk factors that inform targeted interventions (Kim et al., 2022; Symon and Cassell, 2012). These studies could also evaluate how systemic changes–such as trauma-informed training programs and workload management strategies—support teachers' wellbeing and retention, as well as refining school-specific interventions for diverse educational contexts. Another priority is understanding how systemic factors, such as adequate training and unrealistic expectations, contribute to teachers' feelings of inadequacy and vulnerability to vicarious trauma. Addressing these root causes through policy and professional development could strengthen teacher confidence and resilience (Oberg et al., 2024).

This study provides a high-level understanding of the impacts of vicarious trauma in the teaching profession during and following the COVID-19 public health restrictions in Victoria, Australia. With more teachers leaving the profession now more than ever (Cuervo and Vera-Toscano, 2025), there is need for further research on how traumatic content impacts the teaching profession uniquely and the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in education.

Conclusion

This study builds on existing research by examining the profound impacts of role changes and trauma exposure on teachers during and following the COVID-19 public health restrictions in Victoria, Australia. It highlights how educators' roles were reshaped to provide more pastoral care to students and the sustained nature of this role expansion. Further, findings detailed the pathways that exposed educators to traumatic content and the negative emotions associated with the cumulative effects of student trauma. These changes significantly contributed to educator stress and vicarious trauma symptoms. Participants reported feeling inadequate and overwhelmed by the dual demands of addressing educational and emotional needs in an increasingly complex role—challenges exacerbated by insufficient systemic support, or a lack of training and guidance from leadership.

These findings emphasize the need for further research to understand how vicarious trauma is affecting the teaching population. This research is essential for retaining a supported teaching workforce. These findings also call for the need to explore systemic reforms, including specialized trauma-informed training and institutional changes, to relieve teachers of the disproportionate burden placed on them.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data will be available by the authors upon request, with limitations due to anonymity of participations.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

OC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SO: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SA: Writing – review & editing. JM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the teachers who participated in this research. Further, the authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Jimmy Twin and Ms Amanda Moo for reviewing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

2

Ashley-Binge S. Cousins C. (2020). Individual and organisational practices addressing social workers' experiences of vicarious trauma. Practice32, 191–207. 10.1080/09503153.2019.1620201

3

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited (2023). Spotlight: Australia's teacher workforce today.

4

Beames J. R. Christensen H. Werner-Seidler A. (2021). School teachers: the forgotten frontline workers of Covid-19. Austr. Psychiatry. 29, 420–2. 10.1177/10398562211006145

5

Berger E. Nott D. (2024). Predictors of compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction among Australian teachers. Psychol. Trauma Theor. Res.Pract. Policy16, 1309–18. 10.1037/tra0001573

6

Billett P. Turner K. Li X. (2023). Australian teacher stress, well-being, self-efficacy, and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sch. 60, 1394–414. 10.1002/pits.22713

7

Brandenburg R. Larsen E. Simpson A. Sallis R. Trần D. (2024). “I left the teaching profession … and this is what I am doing now”: a national study of teacher attrition. Austr. Educ. Res. 51, 2381–400. 10.1007/s13384-024-00697-1

8

Braun V. Clarke V. (2021). Thematic analysis: a practical guide. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

9

Bryman A. (2016). Social research methods/Alan Bryman. 5th Edn. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

10

Carroll A. Forrest K. Sanders-O'Connor E. Flynn L. Bower J. M. Fynes-Clinton S. et al . (2022). Teacher stress and burnout in Australia: examining the role of intrapersonal and environmental factors. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 25, 441–469. 10.1007/s11218-022-09686-7

11

Chatters R. Dimairo M. Cooper C. Ditta S. Woodward J. Biggs K. et al . (2024). Exploring the barriers to, and importance of, participant diversity in early-phase clinical trials: an interview-based qualitative study of professionals and patient and public representatives. BMJ Open. 14:e075547. 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075547

12

Creswell J. W. Poth C. N. (2017). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

13

Cuervo H. Vera-Toscano E. (2025). Teacher retention and attrition: understanding why teachers leave and their post-teaching pathways in Australia. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 1–18. 10.1080/02188791.2025.2473356

14

De Nobile J. (2016). Organisational communication and its relationships with occupational stress of primary school staff in Western Australia. Austr. Educ. Res. 43, 185–201. 10.1007/s13384-015-0197-9

15

Dwyer S. C. Buckle J. L. (2009). The space between: on being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Met. 8, 54–63. 10.1177/160940690900800105

16

Figley C. (1999). “Compassion Fatigue: Toward a New Understanding of the Cost of Caring,” in Secondary Traumatic Stress, Sidran Institute ed. B.H. Stamm (Towson, MD, Sidran Press) 3–28.

17

Figley C. R. (1995). “Compassion Fatigue: Toward a New Understanding of the Costs of Caring,” in Secondary Traumatic Stress: Self-Care Issues for Clinicians, Researchers, and Educators, ed. B. H. Stamm (Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press) 3–28.

18

Flack C. B. Walker L. Bickerstaff A. Earle H. Margetts C. (2020). Educator perspectives on the impact of COVID-19 on teaching and learning in Australia and New Zealand. Melbourne, Australia: Pivot Professional Learning.

19

Flanagan A. M. Cormier D. C. Daniels L. M. Tremblay M. (2024). Exploring how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted teacher expectations in schools. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 27, 2199–231. 10.1007/s11218-024-09924-0

20

Fraser A. Molineux J. Armageo C. Meneses I. (2024).The Silent Cost: Impact and Management of Secondary Trauma in Educators (2024 Interim Report). Sydney, Australia: The Energy Factory and Deakin University.

21

Freudenberger H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Iss. 30, 159–65. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

22

Giles-Kaye A. Quach J. Oberklaid F. O'Connor M. Darling S. Dawson G. et al . (2023). Supporting children's mental health in primary schools: a qualitative exploration of educator perspectives. Austr. Educ. Res. 50, 1281–301. 10.1007/s13384-022-00558-9

23

Gore J. Fray L. Miller A. Harris J. Taggart W. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: an empirical study. Austr. Educ. Res. 48, 605–37. 10.1007/s13384-021-00436-w

24

Goudarzi E. Hasanvand S. Raoufi S. Amini M. (2023). The sudden transition to online learning: Teachers' experiences of teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE18:e0287520. 10.1371/journal.pone.0287520

25

Greeson J. K. Briggs E. C. Layne C. M. Belcher H. M. Ostrowski S. A. Kim S. et al . (2014). Traumatic childhood experiences in the 21st century: broadening and building on the ACE studies with data from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. J. Interpers. Viol. 29, 536–56. 10.1177/0886260513505217

26

Ha C. Pressley T. Marshall D. T. (2025). Teacher voices matter: the role of teacher autonomy in enhancing job satisfaction and mitigating burnout. PLoS ONE20:e0317471. 10.1371/journal.pone.0317471

27

Hiscock H. Chu W. O'Reilly G. Freed G. L. White M. Danchin M. et al . (2022). Association between COVID-19 restrictions and emergency department presentations for paediatric mental health in Victoria, Australia. Austr. Health Rev. 46, 529–36. 10.1071/AH22015

28

Hydon S. Wong M. Langley A. K. Stein B. D. Kataoka S. H. (2015). Preventing secondary traumatic stress in educators. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N Am. 24, 319–33. 10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.003

29

Idoiaga Mondragon N. Fernandez I. L. Ozamiz-Etxebarria N. Villagrasa B. Santabárbara J. (2023). PTSD (Posttraumatic Stress Disorder) in teachers: a mini meta-analysis during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health20:1802. 10.3390/ijerph20031802

30

Isobel S. Thomas M. (2022). Vicarious trauma and nursing: an integrative review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 31, 247–59. 10.1111/inm.12953

31

Iversen S. Robertson N. (2021). Prevalence and predictors of secondary trauma in the legal profession: a systematic review. Psychiatry Psychol. Law28, 802–22. 10.1080/13218719.2020.1855270

32

Joubert L. Hocking A. Hampson R. (2013). Social work in oncology—Managing vicarious trauma—The positive impact of professional supervision. Soc. Work Health Care52, 296–310. 10.1080/00981389.2012.737902

33

Kaleveld L. Bock C. Maycock-Sayce R. (2020). COVID-19 and Mental Health. Centre for Social Impact.

34

Kim L. E. Oxley L. Asbury K. (2022). “My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open”: a longitudinal study of teachers' mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 92, 299–318. 10.1111/bjep.12450

35

King N. Hugh-Jones S. (2018). The interview in qualitative research.London, UK: Sage, 121–144.

36

Klusmann U. Aldrup K. Roloff-Bruchmann J. Carstensen B. Wartenberg G. Hansen J. et al . (2023). Teachers' emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 pandemic: Levels, changes, and relations to pandemic-specific demands. Teach. Teach. Educ. 121:103908. 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103908

37

Kotowski S. E. Davis K. G. Barratt C. L. Davis K. Kotowski S. (2022). Teachers feeling the burden of COVID-19: Impact on well-being, stress, and burnout. WORK71, 407–15. 10.3233/WOR-210994

38

Kupers E. Mouw J. M. Fokkens-Bruinsma M. (2022). Teaching in times of COVID-19: a mixed-method study into teachers' teaching practices, psychological needs, stress, and well-being. Teach.Teach. Educ. 115:103724. 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103724

39

Lerias D. Byrne M. K. (2003). Vicarious traumatization: symptoms and predictors. Stress Health19, 129–38. 10.1002/smi.969

40

Levkovich I. (2020). “The weight falls on my shoulders”: perceptions of compassion fatigue among israeli preschool teachers. Asia Pac. J. Res. Early Child. Educ. 14, 91–112. 10.17206/apjrece.2020.14.3.91

41

Liamputtong P. (2009). Qualitative data analysis: conceptual and practical considerations. Health Promot. J. Austr. 20, 133–9. 10.1071/HE09133

42

Litosseliti L. (2003). Using Focus Groups in Research: A&C Black. 104.

43

Macnamara N. (2020). Making sense of complex and challenging behaviours. Centre for Excellence in Theraputic Care.

44

Mathews B. Pacella R. Scott J. G. Finkelhor D. Meinck F. Higgins D. J. et al . (2023). The prevalence of child maltreatment in Australia: findings from a national survey. Med. J. Aust. 218 Suppl 6, S13–s8. 10.5694/mja2.51873

45

McLaren S. Green E. C. R. Anderson M. Finch M. (2024). The importance of active-learning, student support, and peer teaching networks: a case study from the world's longest COVID-19 lockdown in Melbourne, Australia. J. Geosci. Educ. 72, 303–17. 10.1080/10899995.2023.2242071

46

Merriam S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. 2nd Edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

47

Meyer J. (2000). Qualitative research in health care. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. BMJ. 320, 178–81. 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178

48

Mockler N. Stacey M. (2021). Evidence of teaching practice in an age of accountability: when what can be counted isn't all that counts. Oxford Rev. Educ. 47, 170–88. 10.1080/03054985.2020.1822794

49

Molnar B. E. Sprang G. Killian K. D. Gottfried R. Emery V. Bride B. E. et al . (2017). Advancing science and practice for vicarious traumatization/secondary traumatic stress: a research agenda. Traumatology23, 129–42. 10.1037/trm0000122

50

Moran R. J. Asquith N. L. (2020). Understanding the vicarious trauma and emotional labour of criminological research. Met. Innov.13:205979912092608. 10.1177/2059799120926085

51

Morgan D. L. (1993). Qualitative content analysis: a guide to paths not taken. Qual. Health Res. 3, 112–21. 10.1177/104973239300300107

52

Oberg G. Carroll A. Macmahon S. (2023). Compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress in teachers: How they contribute to burnout and how they are related to trauma-awareness. Front. Educ. 8. 10.3389/feduc.2023.1128618

53

Oberg G. Macmahon S. Carroll A. (2024). Assessing the interplay: teacher efficacy, compassion fatigue, and educator well-being in Australia. Austr. Educ. Res. 52. 10.1007/s13384-024-00755-8

54

Ormiston H. E. Nygaard M. A. Apgar S. A. (2022). Systematic review of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue in teachers. Sch. Mental Health14, 802–17. 10.1007/s12310-022-09525-2

55

Paris D. Winn M. T. (2014). Humanizing Research: Decolonizing Qualitative Inquiry with Youth and Communities. 55 City Road, London: SAGE Publications, Inc. Available online at: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/humanizing-research-decolonizing-qualitative-inquiry-with-youth-communities (Accessed May 5, 2023).

56

Pearlman L. A. Saakvitne K. W. (1995). Trauma and the Therapist: Countertransference and Vicarious Traumatization in Psychotherapy With Incest Survivors. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company, xix, 451-xix.

57

Pressley T. Ha C. Learn E. (2021). Teacher stress and anxiety during COVID-19: an empirical study. Sch. Psychol. 36, 367–76. 10.1037/spq0000468

58

Rauvola R. S. Vega D. M. Lavigne K. N. (2019). Compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization: a qualitative review and research agenda. Occupat. Health Sci. 3, 297–336. 10.1007/s41542-019-00045-1

59

Salmon S. Taillieu T. L. Stewart-Tufescu A. MacMillan H. L. Tonmyr L. Gonzalez A. et al . (2023). Stressors and symptoms associated with a history of adverse childhood experiences among older adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Manitoba, Canada. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 43, 27–39. 10.24095/hpcdp.43.1.03

60

Shea L. Pesa J. Geonnotti G. Powell V. Kahn C. Peters W. et al . (2022). Improving diversity in study participation: Patient perspectives on barriers, racial differences and the role of communities. Health Expect. 25, 1979–87. 10.1111/hex.13554

61

Skaalvik E. M. Skaalvik S. (2015). Job satisfaction, stress and coping strategies in the teaching profession-what do teachers say?Int. Educ. Stud. 8, 181–92. 10.5539/ies.v8n3p181

62

Symon G. Cassell C. (2012). Qualitative Organizational Research: Core Methods and Current Challenges. 55 City Road,London: SAGE Publications, Inc. Available online at: https://sk.sagepub.com/dict/mono/qualitative-organizational-research-core-methods-and-current-challenges/toc (Accessed July 31, 2024).

63

Van Bergen P. Daniel E. (2023). “I miss seeing the kids!”: Australian teachers' changing roles, preferences, and positive and negative experiences of remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Austr. Educ. Res.50, 1457–76. 10.1007/s13384-022-00565-w

64

Wu Y. Bo E. Yang E. Mao Y. Wang Q. Cao H. et al . (2024). Vicarious trauma in nursing: a hybrid concept analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 33, 724–39. 10.1111/jocn.16918

Summary

Keywords

burnout, COVID-19 pandemic, secondary traumatic stress, teachers, vicarious trauma

Citation

Crivari O, Oxford S, Schroder C, Anderson S and McMillan J (2025) “It's something you can't wash off; you carry it with you”: a qualitative study into teachers' experiences of vicarious trauma symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Victoria, Australia. Front. Educ. 10:1659431. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1659431

Received

04 July 2025

Accepted

29 September 2025

Published

16 October 2025

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Katie Howard, University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Amanda Nuttall, Leeds Trinity University, United Kingdom

Melissa Tremblay, University of Alberta, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Crivari, Oxford, Schroder, Anderson and McMillan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olivia Crivari olivia.crivari@monash.edu

†ORCID: Olivia Crivari orcid.org/0009-0008-1182-6242

Sarah Oxford orcid.org/0000-0002-2277-8433

Carmen Schroder orcid.org/0009-0001-3507-8575

Sarah Anderson orcid.org/0000-0002-9932-3285

Janine McMillan orcid.org/0000-0002-1615-4237

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.