- 1Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 2School of Education, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, United States

- 3California Education Partners, San Francisco, CA, United States

- 4Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 5National Network of Education Research Practice Partnerships, Rice University, Houston, TX, United States

Educational leaders and researchers have stressed the value of centering communities in research. Yet, substantive research collaborations have remained the exception rather than the rule. Critical, organizational, and learning theories suggest the need to modify research systems, organizations, and infrastructure for the broad adoption of collaborative paradigms. We present a framework for normalizing collaborative research in the field of education: a desire for research impact animates these changes and will require actions that support egalitarian funding, power-leveling design, deliberate learning opportunities, expansive communication, and justice-aligned incentives. We build on the work of the Collaborative Education Research Collective to explore our framework through a sample of eight researchers’ vignettes describing their collaborative learning experiences. We find that authors center their narratives on individually compelling experiences with research impact, design, and learning opportunities. However, less emphasized action areas of our framework—funding, communication, and incentives—highlight the importance of expanding from individual to organizational change. Our findings and illustrative examples serve as a charge to proactively advance the role of research in creating more liberated educational futures.

Introduction

Despite more than a century of efforts to realize the democratic ideals of expanded opportunities for youth, inequities in educational outcomes persist. Among the many “hard resets” necessary to achieve the transformation of school systems and practices toward equity (Ladson-Billings, 2021) is the historical relationship between education research, practice, and communities (Conaway, 2020; Oakes, 2017). Education research has often worked independently of school systems and the youth and families they serve, developing innovations that are then intended to translate into practice (Coburn and Penuel, 2016). This research has been done in ways that have often reinforced, rather than interrogated, oppressive settler-colonial perspectives (Paris, 2019).

Collaborative approaches to education research challenge this unidirectional flow of knowledge from research to practice and can take many forms. Research-practice partnerships (RPPs; Farrell et al., 2021), youth participatory action research (YPAR; Ozer et al., 2024), design-based implementation research (DBIR; Fishman and Penuel, 2018), and community-engaged research (London et al., 2022) are all examples of collaborative approaches to educational research. Each of these approaches operates from a shared stance that research can be a powerful tool to realize educational equity and justice, but only if the practice of research disrupts historical trends of extracting from communities, centering researcher knowledge over local knowledge, and separating research from its context.

Despite these shifts, collaborative education approaches remain niche; we ask, what would it take to make collaborative approaches the norm? Over the past five years, we organized a collective effort to define ways to broaden participation in collaborative education research (Collaborative Education Research Collective, 2023). This work included a multi-phase process by which the collective identified that ongoing learning in collaborative research settings benefits from moving beyond a static list of competencies to a set of probing questions (Randall, 2021). The questions were organized into five interconnected categories:

a. System landscape in which educational research is situated;

b. Interpersonal relationships that position all collaborators positively and powerfully;

c. Intrapersonal relationships that beckon individuals to examine their own postures;

d. Resources mobilized for more equitable educational systems; and

e. Educational research methods employed for the needs of local communities.

The CERC report concluded with the reminder that “building a field of collaborative education research requires coalition building that will take time and the involvement of multiple organizations, leaders, and individuals who are willing to build bridges, share power, collaborate, and break down historically unjust systems” (Collaborative Education Research Collective, 2023, p. 29).

These collective efforts and recent scholarship around collaborative education research stress that it is critical to identify ways that ‘research-side’ systems and organizations–which wield considerable power over the research enterprise, including the determination of research priorities; content, form and pace of knowledge production; and distribution of resources–must transform so that collaborative learning can grow and thrive (Gamoran, 2022; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022; Yamashiro et al., 2022). Building on existing scholarship (Farrell et al., 2021; Henrick et al., 2017; Sjölund et al., 2022; York et al., 2020), we focused on the implications of CERC’s charge to research institutions.

In this study, we present a framework meant to influence the transformation of systems, organizations, and infrastructures to coherently foster greater participation in collaborative education research. Our framework reflects the intersection of research traditions we represent as scholars: critical theories that compel us to interrogate existing power structures; organizational theories, which articulate how systems form, function, and change; and the learning sciences, which provide principles for the design of learning environments richly informed by cultural and historical contexts. Conceptually, these literatures all point to the necessity of changes in institutional systems, organizations, and infrastructures if collaborative education research is to become the norm. In particular, we draw on these traditions to argue for an imperative to acknowledge dynamics of power and privilege; name and disrupt dominant norms, assumptions, and roles; and design for change across systems and contexts. Our experiences with CERC and insights from these literatures motivate our framework for Action to Empower Collaborative Education Research. The framework names six action areas for research institutions: research impact, egalitarian funding, power-leveling design, deliberate learning opportunities, expansive communication, and justice-aligned incentives. While we stress the power of institutional action for transforming research systems and organizations, the framework also offers insight to individuals seeking to promote collaborative research within their spheres of influence.

In what follows, we justify and describe our framework as a set of actions that are necessary to normalize collaborative education research. We then use the framework as a lens for making sense of eight CERC members’ vignettes describing collaborative education research experiences. Finally, we consider what the framework illuminates about these vignettes, including implications for movement from individual to organizational action.

Transformation of research at the intersection of critical, organizational, and learning perspectives: a review of literature

Critical, organizational, and learning theories offer insights for understanding the complexity of educational change required for collaborative research. Though often siloed, all three bodies of knowledge teach that existing forms of practice are self-perpetuating unless they are intentionally disrupted. Critical theories remind us of centuries-old systems of oppression and inequity that persist despite efforts to change research endeavors (e.g., Paris and Winn, 2013; Patel, 2015; Tuck and Yang, 2014). Decades of organizational research provide examples of efforts to change educational practice in ways that merely result in surface-level or technical tweaks (e.g., Tyack and Cuban, 1997) as well as of organizations that seek to maintain their legitimacy by changing discourse but not action (e.g., Meyer and Rowan, 1977). Furthermore, studies of collaboratively learning new forms of practice show that approaches that focus on individuals, such as one-off events and transmission of information, rarely lead to transformative change (e.g., Lave and Wenger, 1991). Insights from each of these traditions meaningfully inform efforts to transform the practice of individuals and organizations involved in education research. These literatures converge in three areas: (1) acknowledging dynamics of power and privilege; (2) naming and disrupting dominant norms, assumptions, and roles; and (3) infusing change across systems and contexts. We identify these areas of convergence as orienting commitments to normalize collaborative research.

Acknowledge power and privilege in research

Education research is often positioned as apolitical or neutral. However, critical perspectives emphasize that all efforts for engagement and change in educational systems are inherently political (Apple et al., 2009; Lubienski et al., 2014). Endeavors to transform systems at the intersection of research and practice attend to and transform political dynamics: conflicts between different value structures. In fact, movements for change are situated within the power dynamics of the communities that are interacting (Yamashiro et al., 2022). For example, research knowledge and theory are often elevated to the status of “Truth” in comparison to practitioner knowledge, which can result in long-standing patterns of trauma, extraction, and disrespect between researchers, educational practitioners, and communities (Chicago Beyond, 2019; Patel, 2015).

Additionally, inequitable societal structures based on race, gender, sexuality, and class shape who holds particular roles, who has power, and who has access to necessary resources (e.g., Chavez et al., 2008; Kirkland, 2019). White supremacy and settler colonialism have had tangible consequences for the privilege and status of racialized people (Delgado and Stefancic, 2001). Critical theories suggest that it is not only an obligation to understand societal injustices but also to address them through fundamental shifts in the ways researchers interact with communities. Tuck and Yang (2014) suggest acts of refusal, stating that “refusal attempts to place limits on conquest and the colonized knowledge by marking what is off limits, what is sacred, and what cannot be known” (p. 225). Patel (2015) suggests another approach, describing the concept of “answerability”–a practice of “being responsible, accountable, and being part of an exchange” so that research resists manifestations of oppression in educational systems (p. 73).

Similarly, organizational perspectives suggest that deliberate reflexivity is necessary to prevent the concentration of research power within the university (Sydow et al., 2020). Within research institutions and organizations, specific roles (e.g., tenured faculty), decision-making policies (e.g., promotion expectations), organizations (e.g., funders), and ideologies (e.g., Whiteness) carry more power than others (Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Gamoran, 2022; Vakil et al., 2016). For example, Sullivan et al. (2001) describe these organizational structures that reinforce power differences as (a) financial control by the research institution, (b) hierarchical decision-making structures that serve the research institution, and (c) structures that position the members of the research institution as “the experts” or “provider” and the community members as the “client.” Similarly, Coburn et al. (2008) describe how positional authority is privileged during organizational negotiations. These perspectives help explain how an imbalance of power privileges knowledge and expertise in the hands of research entities, notably universities. For collaborative education research to become the norm, research-side actors must be committed to upending power and privilege imbalances in research.

Name and disrupt dominant norms, assumptions, and roles

In order to decenter the power researchers wield over the research process, it is important to consider means by which these imbalances manifest: norms and assumptions, including logics, conceptions, frames, and narratives (e.g., Coburn, 2006). We use norms and assumptions to capture the typically implicit ideas and related patterns of interaction that are accepted as normative within a particular context. Critical, organizational, and learning perspectives increasingly surface the implications of enacting dominant norms. We draw particular inspiration from sociocultural learning theories, which emphasize that local, social, and institutional contexts send strong messages about the obligations and identities an individual should fulfill to be recognized as competent and successful in their role (Sfard and Prusak, 2005). Interrogating norms, assumptions, and roles moves beyond what actors do to how and why they do it (e.g., Galloway and Ishimaru, 2020; Kazemi et al., 2022). Without an intentional disruption of norms and assumptions, existing forms of practice persist.

While we cannot provide a comprehensive list of the norms and assumptions to be disrupted here, we can examine critical, organizational, and learning theories for insights. Critical perspectives highlight the persistence of norms and assumptions related to Whiteness and colonialism that remain deeply ingrained in research activities and practices (e.g., Patel, 2015). For example, presuming that Whiteness is a credential discounts people of color–regardless of their formal training–to the detriment of collaborative engagement (Tanksley and Estrada, 2022). Organizational perspectives examine the role of institutional logics, or taken-for-granted assumptions, beliefs, or practices that shape how actors within particular organizations participate (Friedland and Alford, 1991). One such logic suggests that bureaucratic hierarchy is the best tool for governing academic research. Privileging a bureaucratic logic can decrease communities’ agency by presuming that research ethics are better governed by Institutional Review Boards than by community-based research processes (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2024; Oyewole et al., 2023).

In a related vein, sociocultural learning perspectives emphasize that local, social, and institutional contexts send strong messages about the set of normative obligations and identities an individual should fulfill to be recognized as competent and successful in their role (Holland et al., 1998; Wenger, 1998). In education, these expectations span a range of roles, including students, families, community members, teachers, leaders, improvement consultants, researchers, academic deans, and funders (e.g., Farrell et al., 2019; Glazer and Peurach, 2015; Mehta and Fine, 2015; Resnick, 2023). For individuals in any of these roles to participate in new ways, norms and assumptions about competence in these roles will need to be disrupted. In addition, they will need to establish the trust necessary to interact in these ways (Putnam and Borko, 2000). For collaborative education research to become the norm, organizations will need to intentionally foster new normative assumptions about what it means to be a “good” researcher, funder, educator, or community member in research endeavors.

Design for change across systems and contexts

Finally, we cannot isolate the shift to collaborative research to individual people or organizations. Meaningful change efforts recognize that the ways individuals and organizations participate in research processes are situated within complex social and political contexts (Putnam and Borko, 2000; Shirrell et al., 2023; Collaborative Education Research Collective, 2023). From a learning sciences perspective, the situation in which an individual learns is a fundamental part of what is learned. As much as acquiring a specific set of concepts and skills, learning is a process of enculturation into the discourses and practices of a community (Cobb and Bowers, 1999; Lave and Wenger, 1991). From critical perspectives, all individuals and organizations participate within established systems of inequity and injustice (Diamond, 2021). From an organizational perspective, logics from the broader field can shape and be reproduced within the formal structure of organizations (e.g., organizational routines, positions, tools) as well as influence how individuals function within that system (Ray, 2019; Woulfin and Weiner, 2019).

Across all three perspectives, there is an emphasis on coherence across systems and contexts. Here, we define coherence as the alignment of underlying ideas and goals across a system, including experiences, interactions, tools, resources, events, accountability and evaluation practices. All three perspectives emphasize the perils of incoherence. For example, critical race theory suggests that in order to reconcile belief in the color-evasive American Dream with persistent racial oppression, token Black individuals are given privileges within existing structures of racial domination in higher education (Crenshaw, 1988). In this case, institutions respond to incoherence by granting access to a few. The learning sciences show that when contexts are incoherent, a person’s knowing and learning in one context may be unavailable or nonexistent in the other (Greeno et al., 1996). Organizational research finds that incoherence between actual and stated policies can provide organizations legitimacy but not stimulate change. As an illustration, “collaboration” can be used without being precisely defined (Campbell, 2024), organically initiated (Armstrong et al., 2021; Datnow, 2011), democratically coordinated (Keddie, 2015), or adequately supported (Datnow, 2018). These are all factors that divorce collaboration from its presumed impact. Organizational theory suggests that this disconnect can be addressed by recoupling the use of “collaboration” as a term with the use of collaboration as a practice (Yurkofsky, 2020). Consequently, collaborative education research requires a coherent commitment to educational justice.

Creating change through collaborative research in practice requires the involvement and sensemaking of community members at all levels–from the classroom to the school board. Similarly, durable change in support of collaborative research depends on research-side partners incorporating best practices and new learning into their research systems and contexts (Kim et al., 2023). For collaborative education research to become the norm, organizations and individuals must make changes in funding, design, learning opportunities, communication, and incentives, all in service of research impact.

A framework for action to empower collaboration education research

Though these theoretical perspectives provide a vital orientation, we argue that they must be tied to concrete, actionable mechanisms for institutional change. Grounded in our literature review and insights from CERC, we identify six areas that promote the enactment of our orienting commitments: research impact, egalitarian funding, power-leveling design, deliberate learning opportunities, expansive communication, and justice-aligned incentives. Recognizing the disproportionate influence research-side actors have in shaping the research process, we focus on their roles and responsibilities while also underscoring the importance of future work that addresses the contributions and needs of practice-side and community partners.1

While our interest in institutional change privileges using the framework to guide organizational policy, the framework can also inform individual efforts in service of collaborative research. Social movements, after all, are stimulated by individual action (Christiansen, 2011).

We posit that in order to empower collaborative research, research-side actors need to design for change across systems and contexts by attending to each action area in ways that (1) acknowledge power and privilege in research and (2) name and disrupt dominant norms, assumptions and roles (Figure 1). When fully enacted, all six actions lie at the intersection of these commitments. We accompany each action area with guiding questions to support critical reflection and transformation.

Research impact

How do we facilitate engagement with research to create a more just world?

Historically, academia has been positioned as the quintessential site of knowledge generation. Particularly in the social sciences, research impact has been widely viewed as findings being taken up to change the fabric of society. Retaining distance between researchers and research subjects was viewed as a necessary tool for obtaining unbiased and widely applicable findings.

Our commitments reject this assumption. Specifically, they promote stepping beyond the “academic industrial complex” toward scholar-activism (Smith, 1999; Tuck and Yang, 2014, p. 238). Researchers, practitioners, and community members can jointly enact research-based strategies to initiate restorative actions and advance just policies (Vetter et al., 2022; Wilson, 2021). Collaborative research projects are relational, egalitarian, and impactful to the youth, families, and educators often pushed to the periphery. Additionally, they prompt researchers to reflect on their own practice (Martínez and Martinez, 2024). Impact that is meaningful for all involved sits at the heart of collaborative education research.

Egalitarian funding

How does what we fund reflect a value in collaborative practice?

Even when research is conducted in partnerships, in many cases the inequitable distribution of funds worsens the inequitable distribution of power in collaborative projects. Within the current researcher-led funding model, a divide exists between “expert scholars” and “novice practitioners.” Our commitments highlight rejecting the paternalism that dictates that researchers should be sole money managers (London et al., 2022). Instead, budgets should be negotiated with all partners on equal footing. If budgets are moral documents (King, 1967), researchers must ensure their budgets reflect the resources required for research to go beyond academic findings into action. These line items can include compensating practitioners for their contributions to research design and data analysis rather than solely considering research implementation as part of their jobs. More foundationally, simplifying funding applications can empower organizations without researchers and grant-writing capacity to still lead the proposal process (Arce-Trigatti and Spitzley, 2020). Further, some organizations would need to revise their eligibility requirements to expand the types of individuals and organizations qualified to apply for funding (Rivera and Chun, 2022).2 These shifts require funders (e.g., philanthropic, governmental) to change their assumptions about appropriate research roles and adjust their policies in ways that will expand funding access to a broader range of roles and institutions.

Within research institutions, supporting collaborative research requires funding partnership infrastructure, including partnership brokers, meetings, and training (Penuel, 2019; Wentworth et al., 2023). Consistent funding in research organizations and partnership infrastructure is significant given the turbulence that characterizes many school districts and educational organizations.

Power-leveling design

How are we embodying commitments to justice in the research process?

Collaborative research processes are different from traditional research in ways that are reflected in project design. Rather than keeping to tightly bound schedules and analysis plans, at its best, collaborative research is flexible and responsive to the needs of all partners (Arce-Trigatti et al., 2022; Turley and Stevens, 2015). These fluctuations can stem from the needs of students, educators, youth workers, or entire systems. Additionally, collaborative research addresses the ways practice-side and community partners have historically been marginalized in research. This reenvisioning requires the development of routines for relationship building, check-ins, and consensus building (Penuel and Gallagher, 2017). The emphasis on humanizing research experiences refuses the “quantity over quality” norm of White supremacy culture (Okun, 2021).

The unique features of collaborative education research suggest the value of dedicated faculty or staff with related expertise. In particular, Institutional Review Boards can train reviewers to understand the unique mechanics and ethics of collaborative research (Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2024).

Deliberate learning opportunities

How do our learning opportunities reflect the complexity of collaborative research?

A fundamentally different approach necessitates new types of learning opportunities. Collaborative Education Research Collective (2023) urges the field to use the framework to create courses, developmental pathways, resource libraries, and conversation guides. Though there has been deserved attention to these structured learning opportunities, there is also value in experiential learning in practice and community settings (i.e., research apprenticeships; Davidson et al., 2020). As collaborative research is normalized, such learning should be more systematically incorporated into curricula and ongoing professional development.

Expansive communication

How do research-sharing practices support action by a broad cross-section of community members?

Collaborative education research involves open, multidirectional dialogue between research, practice, and community partners. However, an overreliance on communication through peer-reviewed journals has posed an impediment to transparent communication (Cook et al., 2024; Day et al., 2020). Foremost, these venues are often inaccessible for the communities where the research was conducted. Researchers can address this shortcoming by directly communicating with communities through town halls, board meetings, and other forums (McDavitt et al., 2016). Additionally, research findings can be shared through products that are accessible to non-academic audiences: op-eds, brochures, videos, murals, and other means recommended by partners (Ozer et al., 2021).

Beyond new forms of communication, traditional forms of research communication can support collaborative aims by being shared more rapidly (e.g., pre-prints) and widely to those without journal access (e.g., open access publications; Fleming et al., 2021).

Justice-aligned incentives

How are our measures of success aligned with community engagement and impact?

Critical race theory posits that racial justice can be advanced when the interests of White and racialized people converge (Delgado and Stefancic, 2001). It follows that shifting incentives in the historically White academy can promote justice that is aligned with the goals of antiracist collaborative education research. The research apparatus can reconstruct its notion of rigorous scholarship by celebrating the movement of research into action, the time required to do collaborative scholarship, and the communication of collaborative researchers with diverse audiences (Foster, 2010; Gamoran, 2022).

Valuing collaborative research can be conveyed when writing recommendation letters; reviewing articles, grants, and tenure and promotion cases; and conferring awards to scholars and scholarship. In addition to non-pecuniary recognition, collaborative research can be incentivized through funding.

Data and methods

We conducted a qualitative analysis using a sample of vignettes authored by individuals engaged in collaborative education research. Our findings highlight the most frequently represented themes in these researchers’ narratives and identify promising practices that might guide future action.

Context and participants

Our nine-member design team was brought together by a private foundation grant intended to identify the learning necessary for collaborative education research. In the summer of 2022, we hosted three virtual open-access discussions to engage the field in this endeavor. More than 150 interested researchers, practitioners, and community partners participated in these discussions advertised through email lists and social media.

These sessions initially focused on generating lists of skills, knowledge, and dispositions necessary for collaborative education research. Participants then reflected on these lists and applied a critical lens to consider how research frameworks might disrupt entrenched systems of oppression.

Sources of data

As we coordinated the writing of the CERC report, we offered contributors the opportunity to share their personal stories. Our November 2022 call invited submissions of first-person vignettes (approximately 500 words) capturing how contributors or others developed, engaged in, or supported collaborative education research, and asking them to:

• Describe learning about collaborative education research;

• Share efforts to create learning opportunities for others;

• Reflect on conditions that support effective collaboration; and

• Connect their stories to CERC’s themes and share lessons learned.

From over 80 attendees who initially expressed interest in engaging in some collaborative writing, we received 11 completed vignettes (Collaborative Education Research Collective, 2023). One of the vignettes was excluded from our analysis because it was a hypothetical reflection on what they hoped to learn about collaborative research, and not reflections of actual lived experiences. We asked the remaining 10 authors whether they were open to including their vignettes in our analysis and eight authors elected to participate.

The majority of the authors are self-identified researchers who work for universities, research institutes, and nonprofit organizations. Our data offered us a glimpse into the stories these authors chose to highlight when asked to recount a slice of their rich experiences. Their autobiographical inquiries illuminate broader themes but also represent their processes of personal reflection (Ilić-Rajković and Luković, 2013).

Data analysis

We developed a set of deductive codes guided by our framework (Pearse, 2019). In addition to the six action areas that served as parent codes, we developed subcodes based on specific manifestations of the areas in practice (Table 1). We first calibrated our coding on two vignettes, with two sets of two researchers independently coding the vignettes and holding conversations about the meanings of the codes. Then, we refined the categories before a subset of three members of our team coded each of the remaining vignettes.

Though the subcodes were an important tool for making sense of each action area, the number of subcodes posed a challenge for reliability (O’Connor and Joffe, 2020). Thus, our overall and inter-rater analysis focused on the parent codes. In our individual coding of the remaining six vignettes, the three coders had 85% intercoder reliability. We subsequently adjudicated differences in our coding in service of consensus.

Positionality and relationality

One of our overarching commitments for normalizing collaborative education research advocates for an interrogation of power and privilege in research. Thus, we present some of the positions we hold to reflect upon the lenses we bring to the project (Ríos and Patel, 2023). Each member of our team was affiliated with an R1 university where we worked as (or with) faculty, staff, or graduate students. All of us either hold or are pursuing a PhD. Eight of us previously worked as K-12 classroom teachers and each of us had experience with research-practice partnerships. All members of our team are women, and eight are White.

Throughout our research process, we sought to stretch the bounds of our own perspectives by inviting the public into conversations with CERC through public websites, listservs, social media, and outreach to strategic partners. Further, we were attentive to the experiences of different types of institutions (e.g., universities with different Carnegie Classifications, foundations, cross-institutional networks) and regions of the United States. Even when diversity in these dimensions was not in our sample, we considered them and aimed to surface their unique features in our discussion section. Our intentional inclusion attempted to honor the history of humanizing, collaborative inquiry exemplified by critical participatory action research (Kemmis et al., 2014), Black community-university collaborations (Stuart, 2023), and countless others who have refused the specter of objectivity for collaborative research in service of justice.

Findings

In their recounting of collaborative research experiences, the authors highlighted examples of research impact, power-leveling design, and deliberate learning opportunities. We explore these dimensions of our framework with examples from their narratives.

Research impact

Vignette authors described ways collaborative research met their practice-side or community partner’s immediate needs or shaped their own understanding of the research process. Their narratives reflect both outward-facing impact (on schools, communities, and systems) and inward-facing impact (on researchers themselves).

Providing value to practice and community partners

Many authors provided concrete evidence of the ways their projects made an impact on individuals and organizations. These stories highlighted the ways that collaborative research was recognized and valued by partners outside of research institutions. For example, Farley-Ripple (2023) ties her project to the needs of students when she writes,

Recently, the faculty member received a call from a support professional working at the school, sharing that a student had specifically asked them to reach out to him to bring the program back after a lull since the start of the COVID pandemic. (p. A3)

In a similar vein, Tate (2023) shares that a research-practice partnership participant reflected on the affirming nature of the collaborative space,

Today was great. Being back with such thoughtful, knowledgeable humans is food for my brain and soul. You all take care of us and this is one space where I feel my teaching experience is and knowledge is truly valued. (p. A16)

These comments highlight the importance researchers placed on supporting the needs of those working most closely with students–direct impact that might be further downstream in less collaborative projects. They stress that practice is at “the heart of the project” (Tate, 2023, p. A16).

Other authors described using their expertise to offer systematic evaluations of programs. However, these assessments were done alongside practice partners with the intention of collaborative improvement, rather than evaluations conducted with an eye toward external critique. Furthermore, these examples suggested that the evaluation process was educative for practitioners and fostered research relationships. For example, Klien (2023) explains:

We sought to coalesce around a shared understanding of the activities and interest in the research, in this case by developing a logic model. This created an opportunity to build trust and open, productive communication around our specific research and evaluation goals. (p. A7)

These examples provide a personal account of how collaborative research goes beyond delivering findings at the end of the research process to fostering ongoing conversations that shape the ways practice partners understand their work and organizational missions.

Shaping researcher sensemaking

Beyond describing the benefits of their projects for partners, authors also reflected on how collaborations shaped their own perspectives and professional practices. In response to the prompt to share lessons learned, many vignettes revealed that engaging in collaboration led to their rethinking of research itself–its goals, processes, and distribution of power. For example, Goldstein (2023) described how engaging with school district leaders shifted her understanding of knowledge production and scholarly identity:

What we have learned is crucial in collaborative education research, is ontological humility (Kofman, 2013). Collaborative research involves co-building new knowledge together. To do so requires some level of shared understanding or mental mapping about the endeavor. Showing up for our joint work with an ontologically humble stance has allowed our feedback loop (co-teaching) to generate these shared understandings and mental maps—which were absolutely not present at the outset of our partnership. Being ontologically humble means recognizing and valuing both partners as researchers and as practitioners. (p. A5)

These learnings represent a concrete example of joint work shifting a researcher’s approach to scholarship. The reflections advise that humility directs researchers to meet practitioner needs in collaborative endeavors–a different orientation than researcher-centered paradigms.

Power-leveling design

Most vignettes emphasized the collaborative features of their projects. These design decisions revealed their conception of what is most important in collaborative education research: being flexible to the needs of practice partners and incorporating routines for partner relationship building.

Flexible to the needs of partners

Several authors described how collaborative work required significant adaptability as projects evolved in real time. As described by Villavicencio (2023):

The reality of working with community partners, however, means that even the best laid plans may need to be revisited or revamped. In our work, we have faced 6-month delays, shifts in the scope of our data collection, and replacements of entire study sites. Preparing students for this level of unpredictability and modeling how to remain flexible in the face of inevitable change is critical if we want our research to remain relevant and responsive to the needs of our partners. (p. A22)

Such pivots require that researchers adjust more rapidly than traditional academic processes. For example, Tate (2023) mentions that her team supported the needs of their collaborators by ensuring researchers’ “reflections [were] coded and shared back to the group in a timely manner so the project [could] quickly shift directions in response to concerns or opportunities raised by participants” (p. A16). Authors’ including these pivots in their vignettes suggests that elevating the needs of practice represented a notable deviation from traditional research timelines.

Routines that cultivate research relationships with partners

Several authors described how they intentionally structured collaborative routines to build trust and redistribute power within the research process. These routines such as regular meetings, co-planning sessions, and shared decision-making moved beyond logistics into essential tools for fostering equity and partnership. For example, Goldstein (2023) details how her preparation for a course co-taught with district leaders is intentionally structured to foster transparent relationships.

We are together ongoingly, in weekly meetings to prepare to co-teach and to debrief our teaching, as well as in all day in-person classes once each month. During co-teaching, university faculty have come to understand district needs and priorities more deeply, which allows us to tailor instructional content to meet those needs and priorities. This has involved growth that was uncomfortable at times; university faculty are often accustomed to remaining in their domain of expertise and are not typically forced to authentically stretch and adapt. Doing so has engendered an enormous level of trust. (p. A4)

This excerpt illustrates how collaborative routines are not transactional, but relational. In this context, meetings were not merely for communicating information; they were relational spaces where trust was built, roles were negotiated, and the traditional power dynamics of researchers over practitioners were reconfigured.

Often, given the time necessary to promote new norms of engagement, these opportunities to connect were ongoing. As related by Sjölund (2023),

A recurring event at the strategic and decision-making meetings involved school leaders, researchers, and the coordinator from an independent institute discussing their expectations for working together. This was seen as important to avoid ambiguity and uncertainty in each other’s roles. (p. A13)

These routines represent an investment in relationships and a respect for the insights of practice partners in the research process.

Deliberate learning opportunities

In response to the prompt to recount their learning experiences, several authors paid attention to the environments in which their learning occurred. They shared examples of learning outside practice settings in anticipation of collaborative engagement and guided learning within practice settings. In their brief narratives, many authors introduced these settings as a backdrop for describing their projects’ impact and design features.

Learning outside of practice and community settings

Since many authors in our sample were affiliated with universities, it is perhaps unsurprising that they featured learning in university classrooms. Villavicencio (2023) explained how she mentored graduate student researchers interested in collaborative education research:

Before our research begins, students spend ample time exploring the organization(s) we are working with, their histories, trajectories, and current developments. In our work with Internationals (a network of schools that serves recently arrived immigrant youth), for example, students spent a quarter in their roles as research assistants closely studying the organization’s website and policy briefs for mission and common terminology, met a number of its leaders and staff, joined an Internationals webinar to understand its offerings for schools, and reviewed archived video footage to notice changes over time. (p. A21)

Her approach reflects the expectation that collaborative research benefits from understanding particular contexts. It reflects a graduated approach to research training that eased students into new research projects through learning outside of practice settings. Other authors detailed a bi-directional process of moving between learning within and beyond practice settings. Loehr (2023) shared that as a graduate student, her learning was a result of “throwing [herself] into the world of research-practice partnerships (RPP coursework, literature, and networks) and applying that learning while initiating and leading an RPP” (p. A8).

Learning within practice and community settings

Other vignettes focused specific attention to how learning took place within collaborative research settings, often alongside practice-side partners. Tran (2023) reflects on the collective learning of a four-person team as they worked to develop a social studies professional development that honored their experiences as women of color:

We approached our collaboration in education research the same way that we approached our initial collaboration as co-planners and co-facilitators—leaning into each of our strengths. As we worked together on the writing, we started to form our conceptions of our process and content for collaborative learning from the [professional development]. In terms of the process, the four of us approached our collaboration in complementary ways—inviting one another, celebrating one another, building on one another, and offering different pathways and ideas to one another. (p. A18)

This vignette describes the learning of professionals engaging as peers. Other authors mentioned senior scholars or academic advisors helping learners develop as researchers through their experiences in the field. These directed experiences often took place within research assistantships through an apprenticeship model.

Expanding beyond the vignettes: a discussion

We drew on a sample of researcher-authored vignettes to illustrate practices that support the normalization of collaborative education research. Across these narratives, the authors emphasized three areas from an individual lens: research impact, power-leveling design, and deliberate learning opportunities. Their examples spanned contexts, but most were rooted in their perspective as researchers. This positioning is likely appropriate for a framework centered on change in research-side institutions.

Still, as critical race theorist Delgado (1989) reminds us, who tells our stories shapes the stories we tell. Critical race theory stresses the importance of critiquing master narratives that reproduce dominant discourses, specifically around the normalcy of White supremacy (Espino, 2012). In contrast, counter-narratives can be communicated through counter-stories “told for the purpose of resisting a socially shared narrative used to justify the oppression of a social group” (Kinloch et al., 2020; Lindemann, 2020, p. 286). We recognize that our efforts, situated in universities, are part of an educational ecosystem that has a role in reproducing dominant ideologies. Thus, while our findings offer a useful entry point into understanding the features of research entities committed to collaborative education research, they are by no means complete or are they a comprehensive evaluation of our conceptual framework.

Given these limitations, we discuss elements of the framework beyond those emphasized in the vignettes. Notably, the vignettes did not foreground organizational actions or experiences related to egalitarian funding, expansive communication, or justice-aligned incentives. While it is likely that the projects involved organizational support as well as decisions about budgets, external communication, or recognition structures, such dimensions were not central to the stories shared.

This absence may suggest that, in the context of personal reflection, researchers tend to highlight experiences they find most meaningful—such as those related to practice impact, relational design, and professional learning. Topics like funding mechanisms, dissemination strategies, or incentive structures, while important, may feel more administrative or institutional in nature and thus less compelling for narrative exploration. Nevertheless, these less featured action areas help us narrow our attention on promising paths to empowering collaborative education research.

In this section, we discuss the challenge of organizational change; feature expansive communication as a low-cost strategy for strengthening collaborative research; and advocate for the inclusion of a broader set of institutions in collaborative education research discourses.

The challenge of organizational change

Among the action areas, the vignettes gave relatively little attention to egalitarian funding, expansive communication, or justice-aligned incentives. Across all the action areas, the vignettes offered less description of organizational, rather than individual, actions to support collaborative efforts. Their narrative decisions could suggest that they found these dimensions less personally compelling or more difficult to capture in brief, first-person narratives. Additionally, these areas often involve slow-moving institutional processes—such as changing grant procedures, tenure policies, or hiring structures—which are less amenable to storytelling than immediate relational or instructional shifts.

While the framework draws upon critical, organizational, and learning theories to call for infusing change across systems and contexts, the narratives gravitated toward individual action over systemic reform. This focus reflects a broader pattern: structural change is slow, difficult, and perhaps resistant to storytelling from individual’s retrospective accounts. Yet transformation of the research ecosystem depends precisely on those deeper shifts. For example, rather than solely training researchers to apply for community-engaged grants, institutions must also revise the grantmaking process itself.

Skeptics of our approach might argue that an insistence on comprehensive, institutional reform will stifle individual activity or minimize the value of intermediate achievements. We contend that it need not be an either-or proposition. Wins can be celebrated while maintaining the urgent need to create new systems, organizations, and infrastructures.

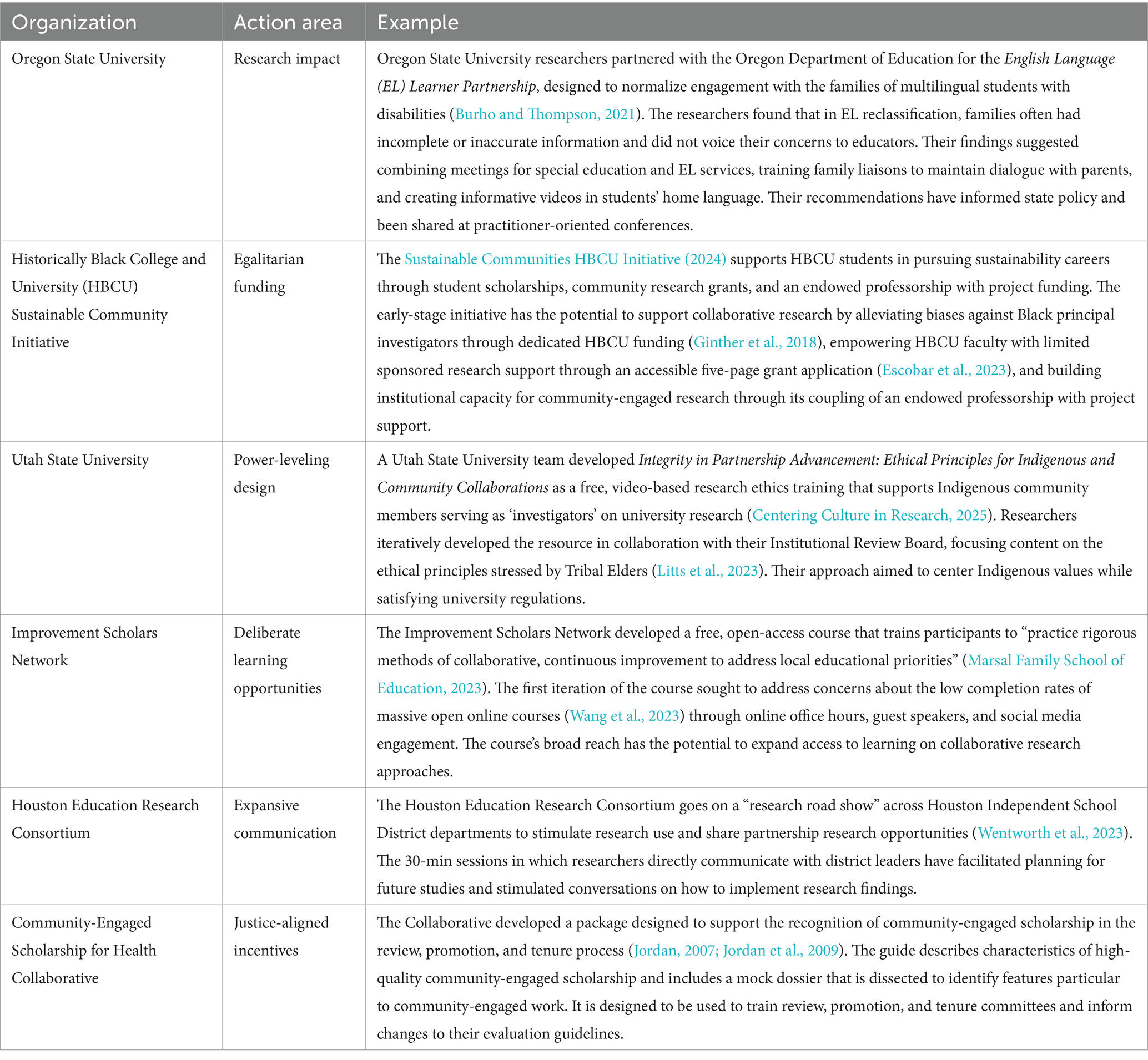

We draw from our experiences with CERC and other collaborative efforts to offer illustrations of institutional actions that can empower collaborative education research (Table 2). These examples also feature less represented focal populations and institution types.

That said, the individual-centered focus of these narratives offers insight into how collaborative education research can continue—even in the absence of strong institutional support. Researchers can influence sub-organizational culture through small, often informal actions: recommending courses on collaborative methods to students, encouraging colleagues to adopt more inclusive budgeting practices, or prioritizing the review of collaborative scholarship despite limited time. In other words, these personal practices may represent entry points for cultural change. The vignettes remind us that while broad policy shifts are essential, much of the work of transforming research systems can be supported through everyday decisions made by individual actors.

A promising strategy: expansive communication

Among the action areas less featured in our narratives, we highlight expansive communication as a relatively low-cost strategy for extending research impact. Therefore, we urge researchers and research institutions to expand the avenues they use to connect with communities about research. This engagement can come in the form of following up with research participants with emergent findings (rather than at the end of a long publication process), building public communication skills (e.g., data visualization, op-ed writing), partnering with individuals with communications/marketing expertise, and using preprint forums. Though these efforts require time, they can be done with minimal additional cost to individuals. Further, these opportunities to share the research process and its impact can begin to increase public confidence in higher education’s value at a moment when the sector is threatened (Rios et al., 2025).

Broader institutional inclusion

Our experiences with collaborative education discourses including CERC suggest that there are a subset of institutions less prominently featured in collaborative research discourses: R2 universities, master’s colleges and universities, HBCUs, minority-serving institutions, tribal colleges, community colleges, and liberal arts colleges. Though these institutions may not devote tens of millions of dollars to research or confer doctorates (American Council on Education, 2025a), many of their faculty conduct research by building upon longstanding relationships with diverse communities. For example, though not focused on research, the Carnegie Elective Classification for Community Engagement recognizes institutions of all types that intentionally and deeply engage with their local communities and have institutional structures that are supportive of engaged work (American Council on Education, 2025b). These contributions suggest there may be value in cultivating cross-institutional partnerships (e.g., an R1 and community college), legitimating smaller research projects, and engaging these institutions’ faculty in discussions on collaborative methods.

Conclusion

In this paper, we presented six interconnected areas of action intended to guide the transformation of educational research systems, organizations, and infrastructures. Through the vignettes, we witnessed how researchers demonstrated the potential of collaborative education research, especially in the areas of research impact, power-leveling design, and deliberate learning opportunities. These examples illustrate what is possible when individual actors engage in intentional, equity-centered practices. However, realizing the full promise of collaborative research requires more than isolated efforts. It demands collective action to reconfigure the broader institutional conditions in which research takes place. The remaining action areas—egalitarian funding, expansive communication, and justice-aligned incentives—point to systemic levers necessary for more durable and far-reaching transformation.

Retaining the status quo is comfortable—and preserves the educational and positional privilege conferred to most readers of this academic article, including us as its authors. Despite community impact plans and inclusion statements, current research infrastructure reflects a commitment to retaining the height of the ivory tower. As a member of CERC noted, the existence of advocates of collaborative research suggests there are enemies of the same work. Dislodging these opponents will require coalitions. These coalitions will include important institutional actors in the educational landscape: faculty members, university administrations, funders, Institutional Review Boards, and professional organizations. But they must also involve the powerful voices of students, leaders whose activism has already manifested Ethnic Studies departments and campus centers for minoritized students (Biondi, 2012). Beyond the bounds of campus, potential partners and communities must be given meaningful power to shape new directions in educational research.

Just as the research methods elevated in this piece emphasize coming together in partnerships, these changes to education research infrastructure will be best accomplished by working cross-institutionally. There have been efforts to build strategic networks through the American Educational Research Association’s Special Interest Groups (SIGs), Collaborative Education Research Collective, Education Deans for Justice and Equity, National Network of Education Research-Practice Partnerships (NNERPP), Rising Educational Scholars Helping Advance Partnership and Equity (RESHAPE), and the Urban Research-Base Action Network (URBAN). Now, those relationships must be marshaled for fieldwide action. Rejecting the primacy of academic expertise will allow us to partner with on-the-ground organizers to effect this change.

The theoretical traditions that informed this work, including critical, organizational, and learning fields, already make strong arguments for the importance of transforming research systems, organizations, and infrastructure in service of equity. The educational, political, economic, and environmental crises we face demand less reflection and more action (Ladson-Billings, 2021). The framework and accompanying examples we present suggest ways individuals and organizations can take steps to normalize collaborative education research within their own contexts. Yet beyond these suggestions, there is unbounded potential to create new tools in service of new futures (Lorde, 1984). Achieving these aims demands that we come together to move collective education research from trite actualities to liberatory possibilities (Kelley, 2002).

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: the Collaborative Education Research Collective (2023). Toward a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. https://hewlett.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Collaborative-Education-Research.pdf.

Author contributions

KO: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. EF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PA-T: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

^Further, each constituent practice-side group deserves attention. For example, expanding the collaborative research engagement of youth will require very different support than that needed by school district administrators.

^We appreciate a thoughtful reviewer for raising this point.

References

American Council on Education. (2025a). About the Carnegie classification®. Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Available online at: http://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/carnegie-classification/

American Council on Education. (2025b). The elective classification for community engagement. Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Available online at: https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/elective-classifications/community-engagement/

Apple, M. W., Au, W., and Gandin, L. A. (2009). The Routledge international handbook of critical education : Routledge.

Arce-Trigatti, P., Klein, K., and Lee, J. S. (2022). Are research-practice partnerships responsive to partners’ needs? Exploring research activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Policy 37, 170–199. doi: 10.1177/08959048221134584,

Arce-Trigatti, P., and Spitzley, N. (2020). “Why am I always being researched?” an application to RPPs, part 1. NNERPP Extra 2, 9–14.

Armstrong, P. W., Brown, C., and Chapman, C. J. (2021). School-to-school collaboration in England: A configurative review of the empirical evidence. Rev. Educ. 9, 319–351. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3248

Burho, J., and Thompson, K. (2021). Parent engagement in reclassification for English learner students with disabilities. J. Family Diversity Educ. 4, 20–41. doi: 10.53956/jfde.2021.155

Campbell, P. (2024). Conceptualising collaboration for educational change: the role of leadership and governance. School Leadership Management 44, 347–372. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2024.2355469

Centering Culture in Research. (2025). Integrity in partnership advancement: ethical principles for indigenous and community collaborations. Centering culture in Research. Available online at: https://centeringculture.org/ipa (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Chavez, V., Duran, B., Baker, Q. E., Avila, M., and Wallerstein, N. (2008). “The dance of race and privilege in community-based participatory research” in Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. eds. M. Minkler and N. Wallerstein, vol. 2nd (Jossey-Bass), 91–105.

Chicago Beyond. (2019). Why am I always being researched? A guidebook for community organizations, researchers, and funders to help us get from insufficient understanding to more authentic truth (Chicago Beyond Equity Series). Chicago Beyond.

Christiansen, J. (2011). “Four stages of social movements. In Editors of Salem Press” in Sociology reference guide: Theories of social movements. Editors of Salem Press (Salem Press), 14–25.

Cobb, P., and Bowers, J. (1999). Cognitive and situated learning perspectives in theory and practice. Educ. Res. 28, 4–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X028002004

Coburn, C. E. (2006). Framing the problem of reading instruction: using frame analysis to uncover the microprocesses of policy implementation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 43, 343–349. doi: 10.3102/00028312043003343

Coburn, C. E., Bae, S., and Turner, E. O. (2008). Authority, status, and the dynamics of insider–outsider partnerships at the district level. Peabody J. Educ. 83, 364–399. doi: 10.1080/01619560802222350

Coburn, C. E., and Penuel, W. R. (2016). Research–practice partnerships in education: outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educ. Res. 45, 48–54. doi: 10.3102/0013189X16631750

Conaway, C. (2020). Maximizing research use in the world we actually live. Education Finance Policy 15, 1–10. doi: 10.1162/edfp_a_00299

Cook, B. G., McClain, S., Corr, F., Waterfield, D. A., Welker, N. P., Fleming, J. I., et al. (2024). Pushing past the paywall: accessing open peer-reviewed research. Teach. Except. Child. 58, 54–62. doi: 10.1177/00400599241257436,

Collaborative Education Research Collective (2023). Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning : The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Crenshaw, K. W. (1988). Race, reform, and retrenchment: transformation and legitimation in antidiscrimination law. Harv. Law Rev. 101, 1331–1387. doi: 10.2307/1341398

Datnow, A. (2011). Collaboration and contrived collegiality: revisiting Hargreaves in the age of accountability. J. Educ. Chang. 12, 147–158. doi: 10.1007/s10833-011-9154-1

Datnow, A. (2018). Time for change? The emotions of teacher collaboration and reform. J. Professional Capital Community 3, 157–172. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-12-2017-0028

Davidson, K. L., Bell, A., Riedy, R., Sandoval, C., Wegemer, C., Clark, T., et al. (2020). “Preparing researchers to participate in collaborative research” in ICLS 2020 proceedings, 2563–2570.

Day, S., Rennie, S., Luo, D., and Tucker, J. D. (2020). Open to the public: paywalls and the public rationale for open access medical research publishing. Research Involvement Engagement 6:8. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-0182-y,

Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. Mich. Law Rev. 87, 2411–2441. doi: 10.2307/1289308

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical race theory: An introduction : New York University Press.

Diamond, J. B. (2021). Racial equity and research practice partnerships 2.0: A critical reflection. William T. Grant Foundation.

Diamond, J. B., and Gomez, L. M. (2023). Disrupting white supremacy and Anti-Black racism in educational organizations. Educ. Res. 1610. doi: 10.3102/0013189X231161054,

Escobar, M., Qazi, M., Majewski, H., and Jeelani, S. (2023). Barriers and facilitators to obtaining external funding at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs). J. STEM Educ. 24.

Espino, M. M. (2012). Seeking the “truth” in the stories we tell: the role of critical race epistemology in higher education research. Rev. High. Educ. 36, 31–67. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2012.0048

Farley-Ripple, E. (2023). “Faculty fellowships for collaborative education research” in Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. ed. Collaborative Education Research Collective (The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), A2–A3.

Farrell, C. C., Harrison, C., and Coburn, C. E. (2019). “What the hell is this, and who the hell are you?” role and identity negotiation in research-practice partnerships. AERA Open 5, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/2332858419849595,

Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Coburn, C. E., Daniel, J., and Steup, L. (2021). Research-practice partnerships in education: The state of the field. William T. Grant Foundation.

Fishman, B., and Penuel, W. (2018). “Design-based implementation research” in International handbook of the learning sciences (Routledge), 393–400.

Fleming, J. I., Wilson, S. E., Hart, S. A., Therrien, W. J., and Cook, B. G. (2021). Open accessibility in education research: enhancing the credibility, equity, impact, and efficiency of research. Educ. Psychol. 56, 110–121. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2021.1897593,

Foster, K. (2010). Taking a stand: community-engaged scholarship on the tenure track. J. Community Engagement Scholarship 3. doi: 10.54656/GTHV1244

Friedland, R., and Alford, R. R. (1991). “Bringing society back in: symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions” in The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. eds. W. W. Powell and P. J. DiMaggio (University of Chicago Press), 232–263.

Galloway, M. K., and Ishimaru, A. M. (2020). Leading equity teams: the role of formal leaders in building organizational capacity for equity. J. Educ. Students Placed Risk 25, 107–125. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2019.1699413

Gamoran, A. (2022). Advancing institutional change to encourage faculty participation in research-practice partnerships. Educ. Policy 37, 31–55. doi: 10.1177/08959048221131564,

Ginther, D. K., Basner, J., Jensen, U., Schnell, J., Kington, R., and Schaffer, W. T. (2018). Publications as predictors of racial and ethnic differences in NIH research awards. PLoS One 13:e0205929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205929,

Glazer, J. L., and Peurach, D. J. (2015). Occupational control in education: the logic and leverage of epistemic communities. Harv. Educ. Rev. 85, 172–202. doi: 10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.172

Goldstein, J. (2023). “Co-teaching with ontological humility in leadership preparation” in Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. ed. Collaborative Education Research Collective (The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), A4–A5.

Greeno, J. G., Collins, A. M., and Resnick, L. B. (1996). “Cognition and learning” in Handbook of educational psychology. eds. D. C. Berliner and R. C. Calfee (Macmillan), 15–46.

Henrick, E. C., Cobb, P., Penuel, W. R., Jackson, K., and Clark, T. (2017). Assessing research-practice partnerships: Five dimensions of effectiveness. William T. Grant Foundation.

Hinnant-Crawford, B., Bonney, E. N., Perry, J. A., Bozack, A. R., Peterson, D. S., Crow, R., et al. (2024). Continuous improvement, institutional review boards, and resistance to practitioner scholarship. Educ. Res. 53, 46–53. doi: 10.3102/0013189X231208413

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W.Jr., Skinner, D., and Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds : Harvard University Press.

Ilić-Rajković, A., and Luković, I. (2013). “Autobiography in educational research” in Contemporary issues of education quality. eds. M. Despotović and E. Hebib (University of Belgrade: Faculty of Philosophy), 455–468.

Jordan, C. M. (Ed.). (2007). Community-engaged scholarship review, promotion & tenure package. Peer review workgroup, community-engaged scholarship for health collaborative, community-campus partnerships for health.

Jordan, C. M., Joosten, Y. A., Leugers, R. C., and Shields, S. L. (2009). The community-engaged scholarship review, promotion, and tenure package: A guide for faculty and committee members. Community Engaged Scholarship Collaborative 20, 66–86.

Kazemi, E., Resnick, A. F., and Gibbons, L. (2022). Principal leadership for school-wide transformation of elementary mathematics teaching: why the principal’s conception of teacher learning matters. Am. Educ. Res. J. 59, 1051–1089. doi: 10.3102/00028312221130706

Keddie, A. (2015). School autonomy, accountability and collaboration: A critical review. J. Educ. Administration History 47, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/00220620.2015.974146

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., and Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: doing critical participatory action research : Springer Singapore.

Kim, M., Shapiro, V. B., Ozer, E. J., Stone, S., Villa, B., Schotland, M., et al. (2023). University’s absorptive capacity for collaborative research: examining challenges and opportunities for organizational learning to engage in research with community partners. J. Community Pract. 31, 397–409. doi: 10.1080/10705422.2023.2273912,

King, M.LJr (1967). The other America. Available online at: https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/191473

Kinloch, V., Penn, C., and Burkhard, T. (2020). Black lives matter: storying, identities, and counternarratives. J. Lit. Res. 52, 382–405. doi: 10.1177/1086296X20966372

Kirkland, D. E. (2019). No small matters: Reimagining the use of research evidence from a racial justice perspective. William T. Grant Foundation.

Klien, K. (2023). “Collaborating with an out of school program provider on a program evaluation design” in Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. ed. Collaborative Education Research Collective (The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), A6–A7.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). I’m here for the hard re-set: post pandemic pedagogy to preserve our culture. Equity Excell. Educ. 54, 68–78. doi: 10.1080/10665684.2020.1863883

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation : Cambridge University Press.

Lindemann, H. (2020). Counter the counterstory: narrative approaches to narratives. J. Ethics Soc. Philos. 17, 286–298. doi: 10.26556/jesp.v17i3.1172

Litts, B., Tehee, M., and Vouvalis, N. (2023). Building ethical infrastructure for community partnership work: the ‘how to engage your IRB’ edition. Center for Integrative Research in Computing and Learning Sciences. Available online at: https://circls.org/partnerships-for-change-partnership-structures-ethical-infrastructure (Accessed October 16, 2023).

Loehr, A. (2023). “Building collaborative partnerships by taking risks and being vulnerable” in Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. ed. Collaborative Education Research Collective (The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), A8–A9.

London, R. A., Glass, R. D., Chang, E., Sabati, S., and Nojan, S. (2022). “We are about life changing research”: community partner perspectives on community-engaged research collaborations. J. Higher Education Outreach Engagement 26, 19–36.

Lorde, A. (1984). “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” in Sister outsider: Essays and speeches (Crossing Press), 110–114.

Lubienski, C., Scott, J., and DeBray, E. (2014). The politics of research production, promotion, and utilization in educational policy. Educ. Policy 28, 131–144. doi: 10.1177/0895904813515329

Marsal Family School of Education. (2023). Transforming education in an interconnected world launch experience: January-April 2024. Available online at: https://marsal.umich.edu/academics-admissions/degrees/online/transforming-education-interconnected-world

Martínez, R. A., and Martinez, D. C. (2024). Learning in dialogue with Latinx children of immigrants: reflections on the co-emergence of collaborative linguistic inquiry and critical pedagogical praxis. Urban Educ. 59, 577–599. doi: 10.1177/00420859221082670

McDavitt, B., Bogart, L. M., Mutchler, M. G., Wagner, G. J., Green, H. D., Lawrence, S. J., et al. (2016). Dissemination as dialogue: building trust and sharing research findings through community engagement. Prev. Chronic Dis. 13:150473. doi: 10.5888/pcd13.150473,

Mehta, J., and Fine, S. (2015). Bringing values back in: how purposes shape practices in coherent school designs. J. Educ. Chang. 16, 483–510. doi: 10.1007/s10833-015-9263-3

Meyer, J. W., and Rowan, B. (1977). Institutional organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 83, 340–363. doi: 10.1086/226550

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2022). The future of education research at IES: advancing an equity-oriented science : The National Academies Press.

O’Connor, C., and Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods 19, 1–13. doi: 10.1177/1609406919899220,

Oakes, J. (2017). 2016 AERA presidential address: public scholarship: education research for a diverse democracy. Educ. Res. 47, 91–104. doi: 10.3102/0013189X17746402,

Okun, T. (2021). White supremacy culture – still here. Available online at: http://www.whitesupremacyculture.info/

Oyewole, K. A., Karn, S. K., Classen, J., and Yurkofsky, M. M. (2023). Equitable research-practice partnerships: A multilevel reimagining. Assembly 5, 40–59.

Ozer, E. J., Abraczinskas, M., Suleiman, A. B., Kennedy, H., and Nash, A. (2024). Youth-led participatory action research and developmental science: intersections and innovations. Annual Review Developmental Psychology 6, 401–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-devpsych-010923-100158

Ozer, E. J., Langhout, R. D., and Weinstein, R. S. (2021). Promoting institutional change to support public psychology: innovations and challenges at the University of California. Am. Psychol. 76, 1293–1306. doi: 10.1037/amp0000877,

Paris, D. (2019). Naming beyond the white settler colonial gaze in educational research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 32, 217–224. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2019.1576943

Paris, D., and Winn, M. T. (Eds.) (2013). Humanizing research: Decolonizing qualitative inquiry with youth and communities : SAGE Publications.

Pearse, N. (2019). An illustration of a deductive pattern matching procedure in qualitative leadership research. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 17. doi: 10.34190/JBRM.17.3.004

Penuel, W. R. (2019). Infrastructuring as a practice of design-based research for supporting and studying equitable implementation and sustainability of innovations. J. Learn. Sci. 28, 659–677. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2018.1552151,

Penuel, W. R., and Gallagher, D. J. (2017). Creating research-practice partnerships in education : Harvard Education Press.

Putnam, R. T., and Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educ. Res. 29, 4–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X029001004

Randall, J. (2021). “Color-neutral” is not a thing: redefining construct definition and representation through a justice-oriented critical antiracist lens. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 40, 82–90. doi: 10.1111/emip.12429

Ray, V. (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 84, 26–53. doi: 10.1177/0003122418822335

Resnick, A. F. (2023). “Attending to role identities within continuous improvement” in Continuous improvement: A leadership process for school improvement. eds. E. Anderson and S. D. Hayes (Information Age Publishing).

Ríos, C. D. L., and Patel, L. (2023). Positions, positionality, and relationality in educational research. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 1–12, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2023.2268036,

Rios, K., Roth, Z. C., and Coleman, T. J. (2025). The importance of scientists’ intellectual humility for communicating effectively across ideological and identity-based divides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 122:e2400930121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2400930121,

Rivera, P., and Chun, M. (2022). Unpacking the power dynamics of funding research-practice partnerships. Educ. Policy 37, 101–121. doi: 10.1177/08959048221134585,

Sfard, A., and Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities. In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educ. Res. 34, 14–22. doi: 10.3102/0013189X034004014

Shirrell, M., Glazer, J. L., Duff, M., and Freed, D. (2023). The winds of changes: how research alliances respond to and manage shifting field-level logics. Am. Educ. Res. J. 60, 1221–1257. doi: 10.3102/00028312231193401

Sjölund, S. (2023). “Learning to negotiate the rules of collaboration” in Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. ed. Collaborative Education Research Collective (The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), A13–A14.

Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., and Ryve, A. (2022). Mapping roles in research-practice partnerships: A systematic literature review. Educ. Rev. 75, 1490–1518. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.2023103,

Stuart, P. H. (2023). The Philadelphia negro: community-university research collaboration in the 1890s. J. Community Pract. 31, 266–283. doi: 10.1080/10705422.2023.2282216,

Sullivan, M., Kone, A., Senturia, K. D., Chrisman, N. J., Ciske, S. J., and Krieger, J. W. (2001). Researcher and researched-community perspectives: toward bridging the gap. Health Educ. Behav. 28, 130–149. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800202,

Sustainable Communities HBCU Initiative. (2024). Sustainable communities HBCU initiative. Available online at: https://hbcusci.org/ (Accessed November 7, 2024).

Sydow, J., Schreyögg, G., and Koch, J. (2020). On the theory of organizational path dependence: clarifications, replies to objections, and extensions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 45, 717–734. doi: 10.5465/amr.2020.0163

Tanksley, T., and Estrada, C. (2022). Toward a critical race RPP: how race, power and positionality inform research practice partnerships. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 45, 397–409. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2022.2097218,

Tate, R. (2023). “An unexpected opportunity: pandemic helps motivate engagement in collaborative research” in Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. ed. Collaborative Education Research Collective (The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), A15–A16.

Tran, V. A. (2023). “A meta-reflection on educator collaboration” in Towards a field for collaborative education research: Developing a framework for the complexity of necessary learning. ed. Collaborative Education Research Collective (The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation), A17–A18.