Abstract

Character strengths play an important role in the healthy development of children and adolescents. However, assessing and nurturing these strengths in educational settings remain challenging. First, this review addresses the challenges of using scales to assess character strengths in children and adolescents. The currently available scales consist of many items, which makes responding to these scales burdensome for children and adolescents and leads to difficulty in using them in busy school settings. To overcome this problem, the study emphasizes the need to develop short scales that can efficiently collect data and minimize the burden on children and adolescents. Second, the review pinpoints challenges in implementing character strength interventions for children and adolescents in the said settings. We emphasize elucidating the role of interventions in the educational curriculum, thus decreasing their duration and simplifying their contents. Addressing the challenges of assessing and nurturing character strengths among children and adolescents and bridging the gap between basic research and educational practice encourage their healthy development.

1 Introduction

Character strengths are positive personality traits that influence thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Peterson and Seligman, 2004). They play a crucial role in promoting mental and physical health (Carr et al., 2021; Schutte and Malouff, 2019). Character strengths are a central theme in positive psychology, which explores optimal human functioning based on scientific evidence, and numerous findings continue to be reported and vigorously debated (Feraco and Casali, 2025; Ruch and Stahlmann, 2024). The results of basic research on character strengths have been applied to educational practices that intend to assess and nurture the character strengths of children and adolescents to encourage healthy development (Lavy, 2020).

Character strengths are linked to several well-established moral and developmental theories that provide important foundations for understanding their measurement and cultivation in school settings. For example, self-determination theory has been successfully applied across various domains including education and healthcare, and that theory posits that fulfilling basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—supports autonomous and controlled motivations, performance, engagement, vitality, and psychological wellbeing (Deci and Ryan, 2000). When individuals use character strengths such as kindness and teamwork, they experience enhanced autonomy through self-directed behavior, increased competence through effective action, and deeper relatedness through social connections (Gradito Dubord and Forest, 2023; Linley et al., 2010). This theoretical foundation explains why character strength interventions consistently promote intrinsic motivation and wellbeing in educational settings.

Virtue ethics provides a theoretical framework and critical foundation for understanding character strengths as moral excellence. Peterson and Seligman (2004) developed their classification and theoretical grounds of character strengths as a social science that emphasize the cultivation of virtues to achieve moral excellence. This approach systematically identifies and empirically examines character strengths to provide evidence-based methods for promoting human flourishing. Bright et al. (2025) extend a perspective foundation on building deep virtue theory in positive social science, citing logical and developmental perspective flaws in some existing weak theories of virtues. They propose four principles for comprehensive virtue theories, including the characteristic principle, which conceptualizes virtues as habitual dispositions that foster personality development. This emphasizes the importance of developmental approaches in nurturing character strengths. Han (2019) demonstrates the connection between Peterson and Seligman's model and moral education through Aristotelian virtue ethics. Their factor-analytic review suggests that the model encompasses both first-order virtues (e.g., character strengths such as kindness and gratitude) and second-order virtues (e.g., practical wisdom, or phronesis, that guides the appropriate expression of first-order virtues). This indicates that the model captures not only individual strengths, but also the integrative wisdom necessary for moral decision-making, thus supporting its systematic relevance to character education.

Character strengths are closely related to civic education theory and predict civic actions, such as volunteering and community involvement (Oosterhoff et al., 2022; Peterson and Seligman, 2004). This theory emphasizes developing citizens capable of democratic participation and social contribution, positioning character strengths as fundamental psychological resources for active citizenship (Metzger et al., 2016; Oosterhoff et al., 2022). Character strengths, such as fairness and leadership, motivate engagement in democratic processes, while character strengths, such as leadership and teamwork, foster community engagement and collective action (Peterson and Seligman, 2004). These civic applications of character strengths demonstrate their importance not only for individual development but also for community wellbeing and democratic participation. Therefore, nurturing character strengths contributes to the broader educational objective of cultivating engaged citizens who can actively participate in a democratic society and promote community wellbeing.

Finally, within social and emotional learning frameworks, character strengths can complement and reinforce the development of core competencies. The five social and emotional learning competencies—self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making—are the areas in which character strengths can manifest in educational contexts (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2020). For example, prudence and self-regulation support self-management, and gratitude and kindness enhance social awareness. Social and emotional learning programs already have strong empirical support demonstrating improvements in social and emotional skills, attitudes, behavior, and academic performance (Durlak et al., 2011). However, integrating character strengths interventions may further reinforce these competencies. Character strengths interventions can consolidate and cultivate the skills learned through social and emotional learning by framing them as enduring personal traits that promote both individual flourishing and positive social interactions. This may promote the long-term retention and generalization of social and emotional learning outcomes.

However, several practical challenges must be addressed in order to assess and nurture the character strengths of children and adolescents, promoting their healthy development based on these theoretical and empirical research findings. This review presents findings and challenges related to assessing and nurturing the character strengths of children and adolescents. Additionally, it offers insights on connecting basic research findings to educational practice and overcoming these challenges.

2 Overview and challenge

2.1 Assessing character strengths among children and adolescents

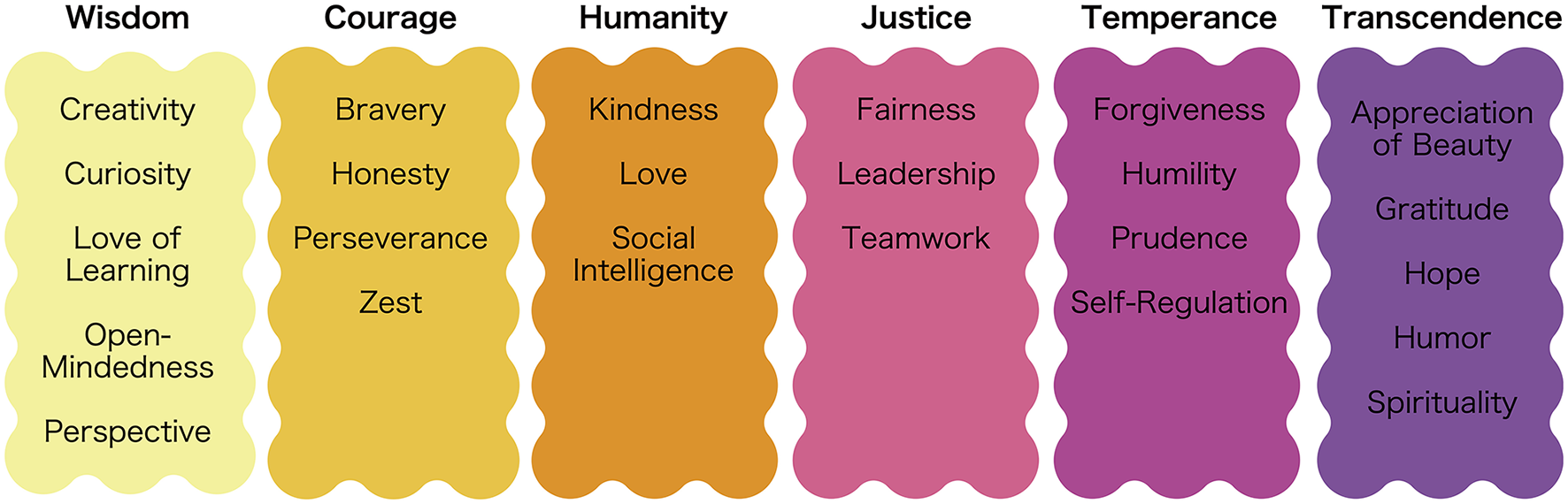

First, the review presents an assessment of character strengths in adults in which the Values-in-Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) is the most representative (Arbenz et al., 2023; McGrath, 2025; Peterson and Seligman, 2004; Ruch et al., 2010). The scale puts forward conceptually organized 6 virtues and 24 character strengths (Figure 1). For example, character strengths such as hope, zest, and perseverance are positively associated with life satisfaction but negatively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress (Feraco et al., 2022; Ruch et al., 2014). While the VIA-IS consists of 240 items, short versions include the Character Strengths Rating Form (Ruch et al., 2014) and Character Strengths Test 24 (Shimai and Urata, 2023), which consists of only 24 items—one-tenth of the VIA-IS.

Figure 1

The VIA classification of virtues and character strengths.

We then present the assessment of character strengths for children and adolescents. While the abovementioned measures were developed for adults, the VIA-IS for Youth (VIA-Youth; Park and Peterson, 2006) and its revised version (VIA-Youth-Revised [VIA-Y-R]; Jermann and McGrath, 2024) were developed for children and adolescents aged between 8 and17 years (Table 1). The VIA-Youth consists of 198 items, while the VIA-Y-R consists of 98 items. For example, character strengths such as gratitude, zest, and love of learning were positively associated with school-related satisfaction, academic self-efficacy, and positive classroom behavior among children and adolescents aged 10–14 years (Weber and Ruch, 2012).

Table 1

| Scale | Version | Target age | Age extension | Items | Item reduction | Advantages | Disadvantages | Differences | Reliability | Validity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal consistency | Test-retest reliability | Content validity | Construct validity | |||||||||

| Character strengths | ||||||||||||

| VIA-Youth | Full | 10–17 | — | 198 | — | Comprehensive | Very large number of items and very high respondent burden | — | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| VIA-Y-R | Short | 8–17 | Extended to age 8 | 98 | 51% | Extension of age range | Large number of items, high respondent burden, and reliability not examined | Age range extension, item reduction, and reliability unexamined | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Strengths knowledge | ||||||||||||

| SKS-C | Full | 10–12 | — | 8 | — | Convenient, simple, and short | Limited age range | — | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| SSKS-C | Ultra-short | 10–12 | No change | 2 | 75% | Convenient, simple, and ultra-short | Limited age range | Item reduction and improved practicality | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Strengths use | ||||||||||||

| SUS-C | Full | 10–12 | — | 14 | — | Convenient, simple, and short | Limited age range | — | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| SSUS-C | Ultra-short | 10–12 | No change | 2 | 86% | Convenient, simple, and ultra-short | Limited age range | Item reduction and improved practicality | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

Comparison of the full and short versions of the character strengths, strengths knowledge, and strengths use scales for children and adolescents.

VIA-Youth, Values-in-Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth (Park and Peterson, 2006); VIA-Y-R, Values-in-Action Inventory of Strengths-Youth-Revised (Jermann and McGrath, 2024); SKS-C, Strengths Knowledge Scale for Children (Oguni and Otake, 2017); SSKS-C, short versions of the Strengths Knowledge Scale for Children (Oguni et al., 2025); SUS-C, Strengths Use Scale for Children (Oguni and Otake, 2017); and SSUS-C, short versions of the Strengths Use Scale for Children (Oguni et al., 2025); ✓, sufficient evidence available; –, no published evidence available.

Alternatively, Govindji and Linley (2007) pointed out the importance of focusing on a more general sense that is not limited to specific character strengths. Thus, they developed the Strengths Knowledge Scale (SKS) to measure awareness of having strengths and the Strengths Use Scale (SUS) to measure the use of strengths. These scales were initially developed for adults (Govindji and Linley, 2007; Takahashi and Morimoto, 2015; Wood et al., 2011), but versions for children and adolescents with age-appropriate language were eventually created (Oguni and Otake, 2017). The SKS and SKS for Children (SKS-C) consist of eight items each, while the SUS and SUS for Children (SUS-C) consist of 14 items each (Table 1). For example, strength knowledge and strength use among children and adolescents aged 8–18 years were positively associated with physical health and subjective wellbeing and negatively associated with depression and stress (Duan et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2018; Oguni and Otake, 2017). Additionally, strength knowledge and strength use in children and adolescents aged 11–18 years were positively associated with school belonging, academic motivation, and grade point average (Arslan et al., 2023; Duan et al., 2018).

However, the large number of items in these scales presents several practical challenges. The first issue is the burden for children and adolescents in terms of responding to a large number of items. They exhibit difficulty in maintaining concentration, while the response time is lengthy (Galesic and Bosnjak, 2009; Rolstad et al., 2011). Consequently, the large number of items reduces the quality of the data and negatively affects the reliability of the results. Importantly, overburdening children and adolescents raises ethical concerns. The second issue pertains to schools' reluctance to cooperate with research given that curriculum overload is currently an issue in many countries and regions (Majoni, 2017; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020). Schools in countries and regions with curriculum overload are typically reluctant to participate in surveys that utilize scales with a large number of items. Even if schools are willing to cooperate, administering this type of survey may be difficult due to numerous school activities. Additionally, schools that are not accustomed to participating in research may be reluctant to adopt such a scale and may only agree to participate in an infrequent survey that includes scales with a few items. The third is the overall time burden of the research. For example, the SKS-C and SUS-C have fewer items than the VIA-Youth and the VIA-Youth-R. However, using as few items as possible for each scale is preferable, because surveys and intervention research use multiple indicators and tasks. In fact, surveys in educational settings require scales with fewer items to minimize the burden on children and adolescents and reduce survey time (Ahlen et al., 2018; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2010).

To conduct basic research and educational practices on character strengths in children and adolescents, developing short scales that enable quick and efficient data collection while minimizing the burden on these groups is necessary. For example, Oguni et al. (2025) aimed to develop a short version of the SKS-C (SSKS-C) and the SUS-C (SSUS-C) using item response theory. Based on discrimination, difficulty, and test information, they developed the SSKS-C and the SSUS-C, which consist of one factor and two items, respectively (Table 1). The SSKS-C and SSUS-C directly reflect the core definitions of strength knowledge and strength use, capturing them concisely without including unnecessary elements (Oguni et al., 2025). Despite the significant reduction in the number of items, both short versions have sufficient measurement accuracy, equivalent to that of the full versions. Oguni et al. (2025) also tested the reliability and validity of the SSKS-C and SSUS-C. As a result, they demonstrated that the SSKS-C and SSUS-C have high internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Furthermore, they showed that the SSKS-C and SSUS-C were positively correlated with life satisfaction and classroom adjustment and negatively correlated with depression and stress. Therefore, the SSKS-C and SSUS-C showed sufficient reliability and validity, which is equivalent to that of the full versions.

However, developing short scales requires careful psychometric consideration. Although short scales have practical advantages, there are potential limitations inherent in item reduction. For example, Goetz et al. (2013) and Smith et al. (2000) caution that reducing the number of items may limit a scale's ability to capture the full complexity of a psychological trait by narrowing construct coverage. Ultra-short scales, such as the SSKS-C and SSUS-C, present unique challenges, including potentially reduced measurement stability and limited ability to detect subtle individual differences across diverse populations. These concerns underscore the critical importance of rigorous psychometric validation during the development process. The SSKS-C and SSUS-C were designed to address these limitations through the systematic application of item response theory (Oguni et al., 2025). This approach enabled the selection of the most informative items while maintaining measurement accuracy equivalent to that of the full versions. However, as with all short scales, it is important to understand the appropriate application situations to achieve these scales' optimal performance. The short versions, SSKS-C and SSUS-C, are well-suited for large-scale research studies and educational screenings where time is limited and efficient assessments are necessary. They are also a practical and efficient alternative in studies with repeated measurements or multiple outcome assessments. This allows researchers to obtain valuable information while minimizing participant burden. The full versions, SKS-C and SUS-C, may offer additional detail for detailed individual profiling or intervention studies where detecting subtle changes over time is particularly important. Although the current validation demonstrates sufficient psychometric properties within the studied populations, continued evaluation across diverse cultural contexts, age groups, and educational settings is necessary to establish the generalizability and robustness of these scales. Ongoing validation ensures that the practical advantages of short scales do not compromise measurement quality. Ultimately, this allows researchers and practitioners to select the most appropriate scale for specific situations and needs.

2.2 Nurturing character strengths among children and adolescents

Interventions that target character strengths are effective in improving the wellbeing of children and adolescents (Proctor et al., 2011; Quinlan et al., 2015). For example, the Awesome Us strengths program, developed in New Zealand, encourages children and adolescents aged 9–12 years to discuss recent events in terms of character strengths and to share their own and others' character strengths (Quinlan et al., 2015). The program aims to teach participants that perceptions of character strengths vary across individuals and that using character strengths is part of daily life. The results demonstrated that improvement in positive emotions and class cohesion and a decrease in class friction. Additionally, the Strengths Gym program, which was developed in the United Kingdom, encourages children and adolescents between the ages of 12 and 14 years to learn about character strengths, recognize their own and others' strengths, and apply them (Proctor et al., 2011). The authors reported increases in positive emotions and life satisfaction. These findings imply that nurturing character strengths in children and adolescents can yield various benefits.

However, certain challenges must be overcome to nurture the character strengths of children and adolescents. The current review presents the educational environment in Japan as an example of these challenges. In Japan, the elementary, junior high, and high school curricula are based on courses of study by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (2017). The curricula include core subjects, such as the Japanese language, mathematics, and science, as well as moral education, special activities, and career education (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, 2017). Many school events and club activities are also conducted. Additionally, in the upper grades, class time, study content, and homework increase. Furthermore, the working hours of teachers in Japan are much longer than those of teachers in other countries (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, 2020). Thus, the schedules of children, adolescents, and teachers in educational settings in Japan are hectic. The subsequent text presents the practical challenges that prevent the implementation of interventions for nurturing character strengths among children and adolescents in Japanese school settings.

The first issues pertain to curriculum positioning. The curriculum in Japan is organized according to course of study; thus, identifying the placement of interventions for character strengths in the curriculum is important (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, 2017). Currently, character strength interventions are implemented during class time through special activities (Izumi, 2019). However, the consistency between these interventions and educational content lacks a comprehensive discussion. For example, Izumi et al. (2021) propose the development of a cross-curricular approach that follows the learning and teaching processes of multiple subjects and domains instead of a single one. Doing so will enable the continuous implementation of character strength interventions in school settings. This approach is significant because it cultivates self-understanding, which is necessary for vocational education (Izumi et al., 2021). It can also be implemented continuously, because it is based on multiple subjects in the curriculum (Izumi et al., 2021). The second issue refers to the time and period of intervention. Character strength interventions consist of several sessions lasting from 60 min to 90 min conducted over weeks or months (Proctor et al., 2011; Quinlan et al., 2015). Implementing these costly interventions is difficult in countries and regions with curriculum overload. Therefore, identifying elements that produce strong intervention effects and developing short-term interventions that focus on these elements are necessary initiatives. The third issue denotes intervention content. Typically, researchers conduct interventions for character strengths. However, to sustain these interventions in school settings, implementation by teachers who have close contact with children and adolescents is desirable. Therefore, the time and period of the intervention must be shortened and simplified. For example, the Strengths Tree application was developed for children and aimed to cultivate a flower of strengths by identifying one's own and others' character strengths (Abe, 2023). By combining the application with two brief lessons on strengths (45 min and 15 min), interventions for character strengths that can be easily and continuously implemented were developed. Implementing these intervention programs in school settings is easy. Thus, they reduce the burden on teachers by shortening the implementation period and increasing ease of implementation. This aspect is important when formulating sustainable intervention programs in school settings. Therefore, to implement interventions for character strengths in school settings, elucidating their place in the curriculum, shortening the time and period of intervention, and simplifying the content of the intervention are necessary aspects.

Although this review primarily focused on the educational environment in Japan, similar challenges, such as curriculum overload, time constraints, and teacher workload, are reported in other countries and regions (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020). For example, character strengths interventions in the United Kingdom (Strengths Gym) and New Zealand (Awesome Us) have been shown to be effective (Proctor et al., 2011; Quinlan et al., 2015). However, as in Japan, developers of these programs have pointed out the need to use short self-report scales to reduce participants' burden and to adopt methods that are convenient for schools (Proctor et al., 2011; Quinlan et al., 2015). Therefore, when implementing these programs in countries or regions with more time and structural constraints, modifications to the intervention period and content may be necessary.

Similar challenges are observed in other parts of Asia. For example, the educational systems in China and South Korea are often characterized by high academic pressure and exam-oriented curriculum, which limits the time available for non-academic programs (Dello-Iacovo, 2009; Kim and Kim, 2021). Nevertheless, some programs have emerged that incorporate character strengths and social-emotional learning into moral education and homeroom activities. In Singapore, for example, the Ministry of Education has emphasized values and character education, incorporating related activities into its national Character and Citizenship Education curriculum (Sim and Tham, 2025). However, even within these structured frameworks, the practical implementation of character strength interventions often competes with academic priorities, and teachers face similar constraints in terms of time and resources. These examples suggest that implementing character strength interventions requires adapting to specific educational environments and institutional contexts, not only in Japan but also in other countries.

3 Ethical considerations in assessing and nurturing character strengths among children and adolescents

Assessing and nurturing character strengths in educational settings involves not only practical challenges, but also significant ethical considerations. When conducting research with children and adolescents, it is crucial to consider informed consent/assent, the right to refuse/withdraw, cultural sensitivity, and the risk of bias. International guidelines establish these ethical principles to protect the rights and wellbeing of children and adolescents (American Psychological Association, 2017; British Educational Research Association, 2024; International School Psychology Association, 2021; United Nations General Assembly, 1989).

Ensuring informed consent and assent is a central ethical requirement. To ensure that parents/guardians and children/adolescents understand the purpose, procedures, and potential impacts of participation, informed consent and assent processes must be carefully implemented (American Psychological Association, 2017; British Educational Research Association, 2024; International School Psychology Association, 2021). United Nations General Assembly (1989) established that children and adolescents have the right to express their views on matters affecting them. This requires assent processes to be developmentally appropriate and provide genuine opportunities for meaningful participation. In school settings, this means providing age-appropriate explanations, using visual aids, and employing simplified language when necessary. It is crucial to ensure that children and adolescents understand that they can ask questions and that their questions will be answered in an age-appropriate manner (Truscott and Benton, 2024; United Nations General Assembly, 1989). Similarly, children and adolescents have the fundamental right to refuse or withdraw from participation without facing negative consequences, thereby safeguarding their autonomy. International guidelines emphasize that researchers must establish clear procedures to ensure that children and adolescents who refuse or withdraw from participation are not disadvantaged (British Educational Research Association, 2024; International School Psychology Association, 2021). These principles are essential not only for ethical compliance but also for building trust with children/adolescents, families, and schools.

Cultural sensitivity and risk of bias must also be considered. According to international guidelines, assessment tools should be culturally adapted to different cultural contexts rather than simply translated (British Educational Research Association, 2024; International School Psychology Association, 2021). For example, in psychotherapy for children and adolescents, researchers have noted that directly translating programs is insufficient for promoting learning, reducing cognitive load, and supporting retention (Bernal et al., 2009; Ishikawa et al., 2023). Similar considerations apply to assessments and interventions of character strengths. These require careful adaptation of examples, activities, and interpretation frameworks to reflect the values and norms of the target population. The risk of bias arises when cultural, linguistic, or socioeconomic factors unintentionally influence the outcomes of an assessment intervention (Bachrach and Newcomer, 2002). In school settings, this involves establishing review processes for assessment materials, consulting with cultural advisors, creating diverse assessment teams, and implementing ongoing evaluations of potential biases in procedures and interpretations. Without these safeguards, assessments and interventions may be ineffective for certain populations and perpetuate educational inequities rather than address them.

4 Conclusions

This review presented previous findings and identified challenges in assessing and nurturing character strengths among children and adolescents. To bridge the gap between basic research and educational practice, it is essential to address these challenges and explore solutions based on two decades of research on character strengths. Specifically, we proposed two primary directions: developing short scales and establishing efficient and effective interventions for implementation in school settings. Future research should further refine these scales and interventions to ensure they are realistic and feasible within the constraints of school settings.

The international context reveals that these challenges are not unique to Japan. Comparisons with educational systems in countries such as the United Kingdom, New Zealand, China, South Korea, and Singapore reveal common issues, including curriculum overload, time constraints, and teacher workload. These cross-national comparisons provide three critical insights that directly inform our implementation recommendations. First, the cases of the United Kingdom and New Zealand suggest that the sustainability of interventions depends on practical considerations, such as minimizing participant burden and aligning implementation methods with the constraints of school settings, even when the interventions demonstrate effectiveness (Proctor et al., 2011; Quinlan et al., 2015). Second, the cases of Asian educational systems, including those in China, South Korea, and Singapore, demonstrate that successful implementation necessitates modifications to exam-oriented curricula, restricted instructional time, and conflicting academic priorities (Dello-Iacovo, 2009; Kim and Kim, 2021; Sim and Tham, 2025). In these contexts, interventions must be flexible and adapted to specific institutional and cultural environments rather than applied uniformly (Bachrach and Newcomer, 2002; Bernal et al., 2009; Ishikawa et al., 2023). Third, the case of Singapore highlights the potential benefits of embedding character strengths activities within existing curricular structures, as in the Character and Citizenship Education curriculum (Sim and Tham, 2025). This integration approach provides a practical method for incorporating character strengths activities into existing curricula without imposing additional burdens on students or teachers.

Based on these cross-national insights, we propose concrete recommendations for educators, policymakers, and curriculum developers. For educators, short scales such as the SSKS-C and SSUS-C can be administered during homeroom periods at regular intervals throughout the year, allowing for systematic monitoring without an additional time burden. Educators can incorporate the use of character strengths into daily classroom routines such as recognizing acts of kindness during peer interactions, expressing gratitude during group work, demonstrating leadership in collaborative projects, and practicing teamwork when achieving shared learning goals. For policymakers, professional development workshops can be incorporated into existing teacher training schedules, and character strengths can be recognized as measurable learning outcomes alongside academic metrics in school evaluation frameworks. Budget allocations for assessment tools and digital platforms should be provided to support implementation. These efforts are consistent with broader educational visions emphasizing the promotion of both individual and collective wellbeing (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, 2023; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019). Policymakers can support students' personal development and contribute to the overall wellbeing of society by integrating character strengths education into school settings, thus advancing the overarching goals of contemporary education policy. For curriculum developers, the successful implementation of modular approaches in Asian contexts suggests creating brief, standalone modules that teachers can integrate into core subjects, such as moral education, social studies, or homeroom activities. Each module should include step-by-step guides, culturally adapted discussion prompts, and simple assessment rubrics that require minimal preparation. Furthermore, curriculum developers can use assessment results to evaluate how current educational policies support the cultivation of character strengths in children and adolescents and to inform curriculum improvements from a curriculum management perspective. These recommendations address the time constraints, resource limitations, and need for contextual adaptation identified through international comparisons. They ensure that character strengths interventions can be implemented sustainably across diverse educational contexts while maintaining theoretical integrity and practical feasibility.

Statements

Author contributions

RO: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TI: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. NA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. KO: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants 24K16681 and 23K12873.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abe N. (2023). “Attempt to develop a strengths intervention that combines class and daily activities,” in Proceedings of the 87th Annual Convention of the Japanese Psychological Association, 906. 10.4992/pacjpa.87.0_3C-046-PP

2

Ahlen J. Vigerland S. Ghaderi A. (2018). Development of the spence children's anxiety scale-short version (SCAS-S). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess.40, 288–304. 10.1007/s10862-017-9637-3

3

American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. American Psychological Association. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code (Accessed August 9, 2025).

4

Arbenz G. C. Gander F. Ruch W. (2023). Breadth, polarity, and emergence of character strengths and their relevance for assessment. J. Posit. Psychol.18, 383–393. 10.1080/17439760.2021.2018026

5

Arslan G. Allen K. A. Waters L. (2023). Strength-based parenting and academic motivation in adolescents returning to school after COVID-19 school closure: exploring the effect of school belonging and strength use. Psychol. Rep.126, 2940–2962. 10.1177/00332941221087915

6

Bachrach C. Newcomer S. F. (2002). Addressing bias in intervention research: summary of a workshop. J. Adoles. Health31, 311–321. 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00395-6

7

Bernal G. Jiménez-Chafey M. I. Domenech Rodríguez M. M. (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: a resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pr.40, 361–368. 10.1037/a0016401

8

Bright D. S. Stansbury J. M. Winn B. A. (2025). We need deep theories of virtues: four principles for advancing research on virtues in positive social science. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol.10:16. 10.1007/s41042-024-00210-0

9

British Educational Research Association (2024). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, 5th Edn. British Educational Research Association. Available online at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-fifth-edition-2024 (Accessed August 9, 2025).

10

Carr A. Cullen K. Keeney C. Canning C. Mooney O. Chinseallaigh E. et al . (2021). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol.16, 749–769. 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

11

Collaborative for Academic Social, and Emotional Learning. (2020). What Is the CASEL Framework? CASEL. Available online at: https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/ (Accessed August 9, 2025).

12

Deci E. L. Ryan R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq.11, 227–268. 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

13

Dello-Iacovo B. (2009). Curriculum reform and ‘quality education'in China: an overview. Int. J. Educ. Dev.29, 241–249. 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.02.008

14

Duan W. Li J. Mu W. (2018). Psychometric characteristics of strengths knowledge scale and strengths use scale among adolescents. J. Psychoeduc. Assess.36, 756–760. 10.1177/0734282917705593

15

Durlak J. A. Weissberg R. P. Dymnicki A. B. Taylor R. D. Schellinger K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students' social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev.82, 405–432. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

16

Feraco T. Casali N. (2025). 20 years of character strengths: a bibliometric review. J. Happ. Stud.26:34. 10.1007/s10902-025-00869-5

17

Feraco T. Casali N. Meneghetti C. (2022). Do strengths converge into virtues? An item- virtue, and scale-level analysis of the Italian values in action inventory of strengths-120. J. Personal. Assess.104, 395–407. 10.1080/00223891.2021.1934481

18

Galesic M. Bosnjak M. (2009). Effects of questionnaire length on participation and indicators of response quality in a web survey. Public Opin. Q.73, 349–360. 10.1093/poq/nfp031

19

Goetz C. Coste J. Lemetayer F. Rat A. C. Montel S. Recchia S. et al . (2013). Item reduction based on rigorous methodological guidelines is necessary to maintain validity when shortening composite measurement scales. J. Clin. Epidemiol.66, 710–718. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.12.015

20

Govindji R. Linley P. A. (2007). Strengths use, self-concordance and wellbeing: implications for strengths coaching and coaching psychologists. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev.2, 143–153. 10.53841/bpsicpr.2007.2.2.143

21

Gradito Dubord M. A. Forest J. (2023). Focusing on strengths or weaknesses? Using self-determination theory to explain why a strengths-based approach has more impact on optimal functioning than deficit correction. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol.8, 87–113. 10.1007/s41042-022-00079-x

22

Han H. (2019). The VIA inventory of strengths, positive youth development, and moral education. J. Posit. Psychol.14, 32–40. 10.1080/17439760.2018.1528378

23

International School Psychology Association (2021). Code of Ethics. Available online at: https://ispaweb.org/2021/06/17/ispa-code-of-ethics/ (Accessed August 27, 2025).

24

Ishikawa S. I. Kishida K. Takahashi T. Fujisato H. Urao Y. Matsubara K. et al . (2023). Cultural adaptation and implementation of cognitive-behavioral psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in Japanese youth. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev.26, 727–750. 10.1007/s10567-023-00446-3

25

Izumi T. (2019). Recognizing and utilizing character strengths to promote psycho-educational services: a short-term intervention program for children. Japanese J. School Psychol.19, 41–54. (In Japanese with English abstract.) 10.24583/jjspedit.19.1_41

26

Izumi T. Ishi S. Takayama M. Ueyama T. Takahashi R. Okamoto A. et al . (2021). Development and verification of a cross-curriculum for career education based on psychological education that promotes children's self-understanding: through practice in multiple schools using a wide support system. J. Sci. School.22, 1–13. (In Japanese with English abstract.)

27

Jermann M. McGrath R. E. (2024). Revising the via-youth: I. Development and interrater convergence. J. Posit. Psychol.19, 554–565. 10.1080/17439760.2023.2282775

28

Kim S. W. Kim L. Y. (2021). Happiness education and the free year program in South Korea. Comp. Educ.57, 247–266. 10.1080/03050068.2020.1812233

29

Lai M. K. Leung C. Kwok S. Y. Hui A. N. Lo H. H. Leung J. T. et al . (2018). A multidimensional PERMA-H positive education model, general satisfaction of school life, and character strengths use in Hong Kong senior primary school students: confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis using the APASO-II. Front. Psychol.9:1090. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01090

30

Lavy S. (2020). A review of character strengths interventions in twenty-first-century schools: their importance and how they can be fostered. Appl. Res. Qual. Life15, 573–596. 10.1007/s11482-018-9700-6

31

Linley P. A. Nielsen K. M. Gillett R. Biswas-Diener R. (2010). Using signature strengths in pursuit of goals: effects on goal progress, need satisfaction, and wellbeing, and implications for coaching psychologists. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev.5, 6–15. 10.53841/bpsicpr.2010.5.1.6

32

Majoni C. (2017). Curriculum overload and its impact on teacher effectiveness in primary schools. Eur. J. Educ. Stud.3, 155–162. 10.5281/zenodo.290597

33

McGrath R. E. (2025). Self-reported character strengths over 21 years. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol.10:6. 10.1007/s41042-024-00200-2

34

Metzger A. Syvertsen A. K. Oosterhoff B. Babskie E. Wray-Lake L. (2016). How children understand civic actions: a mixed methods perspective. J. Adoles. Res.31, 507–535. 10.1177/0743558415610002

35

Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. (2017). Courses of Study. Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/new-cs/1384661.htm (Accessed July 8, 2025).

36

Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. (2020). Teaching and Learning International Survey. Available ONLINE at: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/toukei/data/Others/1349189.htm (Accessed July 8, 2025).

37

Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. (2023). Improving Wellbeing: Directions in the Next Basic Plan for the Promotion of Education. Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/kaigisiryo/2019/09/1421377_00041.html (Accessed August 27, 2025).

38

Oguni R. Izumi T. Abe N. Shimotsukasa T. (2025). Strengths knowledge scale and strengths use scale for children: development of short version scale using item response theory. J. Health Psychol. Res.38, 33–4710.11560/jhpr.240122215

39

Oguni R. Otake K. (2017). Development of the children's version of the strengths knowledge and strengths use scales. Japanese J. Personal.26, 89–91. (In Japanese with English abstract.) 10.2132/personality.26.1.8

40

Oosterhoff B. Whillock S. Tintzman C. Poppler A. (2022). Temporal associations between character strengths and civic action: a daily diary study. J. Posit. Psychol.17, 729–741. 10.1080/17439760.2021.1940247

41

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2019). The OECD Learning Compass 2030. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/tools/oecd-learning-compass-2030.html (Accessed August 27, 2025).

42

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020). Curriculum Overload: A Way Forward. Available online at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-fifth-edition-2024 (Accessed July 8, 2025). 10.1787/3081ceca-en

43

Park N. Peterson C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: the development and validation of the values in action inventory of strengths for youth. J. Adoles.29, 891–909. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.011

44

Peterson C. Seligman M. E. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford University Press.

45

Proctor C. Tsukayama E. Wood A. M. Maltby J. Eades J. F. Linley P. A. (2011). Strengths gym: the impact of a character strengths-based intervention on the life satisfaction and wellbeing of adolescents. J. Posit. Psychol.6, 377–388. 10.1080/17439760.2011.594079

46

Quinlan D. M. Swain N. Cameron C. Vella-Brodrick D. A. (2015). How ‘other people matter' in a classroom-based strengths intervention: exploring interpersonal strategies and classroom outcomes. J. Posit. Psychol.10, 77–89. 10.1080/17439760.2014.920407

47

Ravens-Sieberer U. Erhart M. Rajmil L. Herdman M. Auquier P. Bruil J. et al . (2010). Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: a short measure for children and adolescents' wellbeing and health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res.19, 1487–1500. 10.1007/s11136-010-9706-5

48

Rolstad S. Adler J. Rydén A. (2011). Response burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health14, 1101–1108. 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.003

49

Ruch W. Martínez-Martí M. L. Proyer R. T. Harzer C. (2014). The character strengths rating form (CSRF): development and initial assessment of a 24-item rating scale to assess character strengths. Personal. Individ. Differ.68, 53–58. 10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.042

50

Ruch W. Proyer R. T. Harzer C. Park N. Peterson C. Seligman M. E. (2010). Values in action inventory of strengths (VIA-IS). J. Individ. Differ.31, 138–149. 10.1027/1614-0001/a000022

51

Ruch W. Stahlmann A. G. (2024). Ten do's and don'ts of character strengths research. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol.9, 1–35. 10.1007/s41042-024-00155-4

52

Schutte N. S. Malouff J. M. (2019). The impact of signature character strengths interventions: a meta-analysis. J. Happ. Stud.20, 1179–1196. 10.1007/s10902-018-9990-2

53

Shimai S. Urata Y. (2023). Development and validation of the character strengths test 24 (CST24): a brief measure of 24 character strengths. BMC Psychol.11:238. 10.1186/s40359-023-01280-6

54

Sim J. B. Y. Tham P. H. H. (2025). Demystifying character education for the Singapore context. J. Moral Educ.54, 203–219. 10.1080/03057240.2023.2260957

55

Smith G. T. McCarthy D. M. Anderson K. G. (2000). On the sins of short-form development. Psychol. Assess.12, 102–111. 10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.102

56

Takahashi M. Morimoto Y. (2015). Development of the Japanese version of the Strength Knowledge Scale (SKS) and investigation of its reliability and validity. Japanese J. Personal.24, 170–172. (In Japanese with English abstract.) 10.2132/personality.24.170

57

Truscott J. Benton L. (2024). ‘But, what is a researcher?' Developing a novel ethics resource to support informed consent with young children. Child. Geogr.22, 396–403. 10.1080/14733285.2023.2292551

58

United Nations General Assembly (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child (Accessed August 27, 2025).

59

Weber M. Ruch W. (2012). The role of a good character in 12-year-old school children: do character strengths matter in the classroom?Child Indic. Res.5, 317–334. 10.1007/s12187-011-9128-0

60

Wood A. M. Linley P. A. Maltby J. Kashdan T. B. Hurling R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in wellbeing over time: a longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Personal. Individ. Differ.50, 15–19. 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.004

Summary

Keywords

character strengths, strengths knowledge, strengths use, scale, intervention, children, adolescents, school

Citation

Oguni R, Izumi T, Abe N and Otake K (2025) Assessing and nurturing character strengths among children and adolescents: overview and challenges. Front. Educ. 10:1662099. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1662099

Received

08 July 2025

Accepted

08 September 2025

Published

30 September 2025

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Ioannis Dimakos, University of Patras, Greece

Reviewed by

Nila Zaimatus Septiana, Institut Agama Islam Negeri Parepare, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Oguni, Izumi, Abe and Otake.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ryuji Oguni ryuji.oguni@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.