- 1Centro de Estudios Generales, Universidad de los Andes, Santiago, Chile

- 2Faculty of Education Sciences of Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

- 3Faculty of Education Sciences and Humanities of Universidad Internacional de La Rioja, Logroño, Spain

Introduction: This pilot study investigates teachers’ perceptions of motivations, opportunities, and barriers associated with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) across different educational levels. Understanding these perceptions is essential for identifying factors that foster or hinder the integration of sustainability into educational practice.

Methods: A quantitative design was employed using a validated self-completion online questionnaire distributed to a non-probability sample of 150 teachers in Spain. All participants had prior experience in ESD and voluntarily provided written informed consent.

Results: The findings indicate that transcendent motivations, particularly the desire to contribute to the common good, are the most significant drivers. Institutional cooperation and the integration of sustainability into the strategic planning of educational institutions are perceived as key opportunities. Conversely, barriers such as consumerism and the need for specialized ESD training were identified. Strong positive correlations emerged between intrinsic and transcendent motivations and perceived opportunities for ESD.

Discussion: These results highlight the importance of reinforcing motivations and institutional opportunities to foster sustainable behaviors in educational settings. As one of the few quantitative studies examining teachers’ perceptions of ESD across all educational levels, this research provides a valuable foundation for informing future teacher education programs and public policy initiatives in sustainability education.

Introduction

Continuous warnings about global warming and its consequences on the human population, coming from scientific reports (IPCC, 2023; Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), 2024; World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2024), the media (El Mundo, 2024; El País, 2024a,b; The Guardian, 2024; The New York Times, 2024), and social networks (Mercado and Teso, 2024) are producing a significant, and not always positive effect on citizens (Hickman et al., 2021). Some people are becoming more aware and change their habits, especially when the impact of climate change is local, such as the drought-stricken Spanish coast (Miranda, 2024; Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico, 2024). However, the vast majority continues without changing their behavior toward responsible climate action, and denial or passive attitudes are observed. On the one hand, at elections taking place in different European regions in 2024, certain political parties consider climate change and the measures to be taken as an ideology or fanaticism. On the other hand, how can public awareness of the climate change emergency be raised without provoking eco-anxiety? One of the privileged means to advance with regard to sustainable development, and climate action in particular, is education at all levels: early childhood, primary, secondary, and higher education; both formal and informal (UNESCO, 2020; UNESCO, 2014; Gutiérrez et al., 2006). Ultimately, the aim is to highlight that “climate change disrupts education, while education can shape the human potential for climate change adaptation or mitigation in several ways” (UNESCO & Monitoring and Sustainability Education Research Institute, University of Saskatchewan, 2024, p. 1). Numerous authors recognize the potential and key role of education to share knowledge, reflect, promote values, encourage certain behaviors, and seek solutions to planetary problems (Gorski et al., 2023; Leal et al., 2021). Education also enables developing the necessary skills for the individual and systemic transformation that ESD requires (UNESCO, 2023; Barth and Rieckmann, 2011; Wiek et al., 2011).

“Educators remain key actors in facilitating learners’ transition to sustainable ways of life, in an age where information is available everywhere and their role is undergoing great change. Educators in all educational settings can help learners understand the complex choices that sustainable development requires and motivate them to transform themselves and society.” (UNESCO, 2020, p. 30).

As can be expected, such a leading role for teachers requires training and support to deepen their knowledge, values, and attitudes related to sustainability. They need to be capable of designing teaching-learning scenarios that enable the development of key competencies in sustainability (Bianchi et al., 2022; Brundiers et al., 2021; Eichinger et al., 2022; Gutiérrez and Blanco, 2023; Scherak and Rieckmann, 2020; UNESCO, 2014; UNESCO, 2022b).

Research in Germany showed that both teachers and students in compulsory education want more opportunities for ESD (Eichinger et al., 2022). This desire is often frustrated due to a lack of time and space in the curricula of both compulsory and higher education. In a UNESCO survey of over 58,000 teachers worldwide, “the teachers who said they faced obstacles due to lack of time (approximately 11% of all respondents) indicated that the main reason was the saturation of curricula with different priorities” (UNESCO, 2022b, p. 45). In Sweden, a study showed that less than half of all higher education institutions have achieved integration of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), or have systematically followed up on them (Gorski et al., 2023). Previous studies have been conducted in Spain on teachers’ training needs in ESD. It is perceived that pre-service teachers need to develop critical thinking skills for them to be able to collaborate in socio-environmental problem-solving when they become teachers (Varela-Losada et al., 2019). When higher education teachers are asked about motivations related to the inclusion of sustainability education in their teaching, they consider the holistic conception of sustainability is important. They also believe it is essential to make the ethical dimension that underpins it visible by integrating sustainability training (Busquets et al., 2021). However, there are no known previous studies in the Spanish educational context that analyze perceptions of motivations, opportunities, and barriers regarding ESD through a Likert scale questionnaire applied to teachers across different levels of education.

In addition to incorporating the SDGs, consistency of educational institutions with sustainability values is necessary to move toward sustainability. This is what Tilbury (2011) calls a systemic or connected view of sustainability across institutions, which is necessary to transform the educational experience of students and lead social change for sustainability.

The key role of teachers in ESD is therefore undeniable for both individual and societal change. The effectiveness of their role does not only depend on their knowledge of the topic, but also on the motivations, opportunities and possible barriers related to ESD they perceive in their environment (Mulder et al., 2015; UNESCO, 2022a,b). Although initiatives to train teachers exist, the results of the survey conducted by UNESCO (2022b) show that only one third of the respondents feel prepared to explain topics related to climate change and sustainable consumption well, and comment they lack material and structural support.

It is hence important to know teachers’ perceptions of the opportunities and potential barriers they encounter in the teaching-learning process of sustainability and the motivation they have to engage and involve their students in order to successfully address the challenge of ESD. This knowledge may contribute to redirecting training, building on the strengths that motivate them the most and the opportunities they perceive in their environment. It may also help to try and remove, or lower, barriers and their influence on ESD. The variables analyzed in this paper are explained below: intrinsic, extrinsic, and transcendent motivation, opportunities, and barriers related to ESD.

In this study, motivation is understood as Ruiz Martín (2021) defines it: the force or emotional impulse that leads us to initiate or maintain a behavior with a specific objective. This impulse can be of different types in accordance with where the driving force comes from, and, depending on this, motivation can be intrinsic, extrinsic, or transcendent. Ruiz Martín (2021) points out that when a value is intrinsic to the person pushing to act, motivation is intrinsic. Some define it as “the impetus to do something because it is inherently satisfying rather than being influenced by extrinsic instigators” (Aslam and Rawal, 2019, p. 3). This motivation differs from extrinsic motivation because, in extrinsic motivation, the strength of the motivation results from the desirable consequences of the action (Ruiz Martín, 2021), often incentives or the instrumental value the behavior may have (Ryan and Deci, 2020).

Extrinsic motivation, according to Ryan and Deci (2020), can be divided into different subtypes, ranging from external regulation, which concerns behaviors driven by the pursuit of rewards and avoidance of punishments; introjected regulation, which refers to extrinsic motivation that has been partially internalized; identified motivation, in which the person consciously identifies with the value of an activity; and integrated regulation, where the person not only recognizes and identifies with the value of the activity, but also finds it to be consistent with other core interests and values.

The concept of transcendent motivation is more recent and is understood as “that kind of force that leads people to act because of the usefulness - the consequences - of their actions for another person or other people” (Pérez-López, 1997, p. 18). In this research, transcendent motivation was incorporated as a deep force necessary for behavioral change (Francis, 2015 n. 15, 200 and 211). This is similar to what Howell and Allen (2019) point out about the experiences that led educators in Great Britain to engage in climate change mitigation. In this case, the motivations were concerns related to social justice.

In education, teachers’ motivation for what they teach is an important aspect because it helps them convey the interest in learning content or developing certain skills (Batlle, 2013) to students. According to Ruiz Martín (2021), the brain is sensitive to the emotional component that accompanies the behavior of peers. Because of this, when a teacher is passionate about the teaching-learning process, the emotion it arouses is contagious, and can awaken curiosity and fascination in students. This motivation in teachers can be enhanced or hindered depending on the opportunities or possible barriers teachers detect in their daily work. As teachers’ motivation has hardly been explored in Spain, this study aims to analyze it in the context of Spanish teachers’ perceptions of ESD at all educational levels.

In this paper, the term barrier in the context of ESD is used following what Blanco-Portela et al. (2020) define as a series of obstacles on the way to sustainability, and resistance to change pre-established operational systems. The barriers considered in the study are some of the ones highlighted in research on the subject, such as conceptual difficulties regarding the term sustainability, resistance to change, teaching difficulties linked to a lack of competencies or methodological resources, and a lack of communication and information (Albareda-Tiana et al., 2017; Blanco-Portela et al., 2020; Veiga-Avila et al., 2017). A lack of structural support from schools, training institutions, communities, education systems and governments at all levels is also identified as a barrier to ESD (UNESCO, 2022a). One of the difficulties for teachers is related to how to carry out the assessment of students’ sustainability competency, and the lack of curriculum coverage of ESD (UNESCO, 2022b).

Opportunities mainly refer to what could promote sustainability through certain behaviors, initiatives, or knowledge of the topic (Sánchez-Carracedo et al., 2021). In the report: “Teachers have their say: motivations, skills, and opportunities to teach Education for Sustainable Development and global citizenship,” teacher preparation at the individual level (motivation and skills), and at the system level (skills and opportunities) is shown (UNESCO, 2022b). Being aware of the importance and urgency of incorporating these contents and competencies into the teaching-learning process is also necessary. Moreover, the importance of involving teachers in defining policies, curricula, and assessment methods, as well as supporting teacher leadership and autonomy, creating a school environment conducive to ESD, and fostering greater collaboration with academic institutions is stressed (UNESCO, 2022b).

Building on previous reflections and research, this study aims to explore teachers’ perceptions of motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers or difficulties regarding ESD by means of a Likert scale questionnaire. This instrument was developed by the authors based on a review of the existing literature to understand the perceptions of teachers at all education levels regarding ESD. These issues, which are the focus of this research, have hardly been explored in the Spanish educational context. Previous studies are all qualitative.

This study also aims to find possible correlations between the items related to each of the three factors: motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers. For this purpose, the following research objectives were formulated:

1. Identify teachers’ self-reported motivations for ESD.

2. Explore the opportunities and barriers teachers perceive with regard to ESD.

3. Analyze possible correlations between the above variables.

It is considered that the results of this study may be important to propose lines of action in pre-service and in-service teacher training in the Spanish educational context. They are also relevant to enquire into what else could be done for both compulsory and higher education to continue working on ESD.

Materials and methods

This quantitative research, a pilot study of an exploratory nature, was conducted using an online self-completion questionnaire administered to a sample of 150 Spanish teachers from different cities across the country and from all education levels.

Instrument

The questionnaire developed, through a review of the existing literature on the subject, aims to measure three variables: teachers’ self-reported motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers at different levels of education (from early childhood to university) regarding ESD and climate education. It starts with a section on general information, in which the participants answer questions related to gender, age, years of teaching, the level of education at which they teach, and the place where they teach.

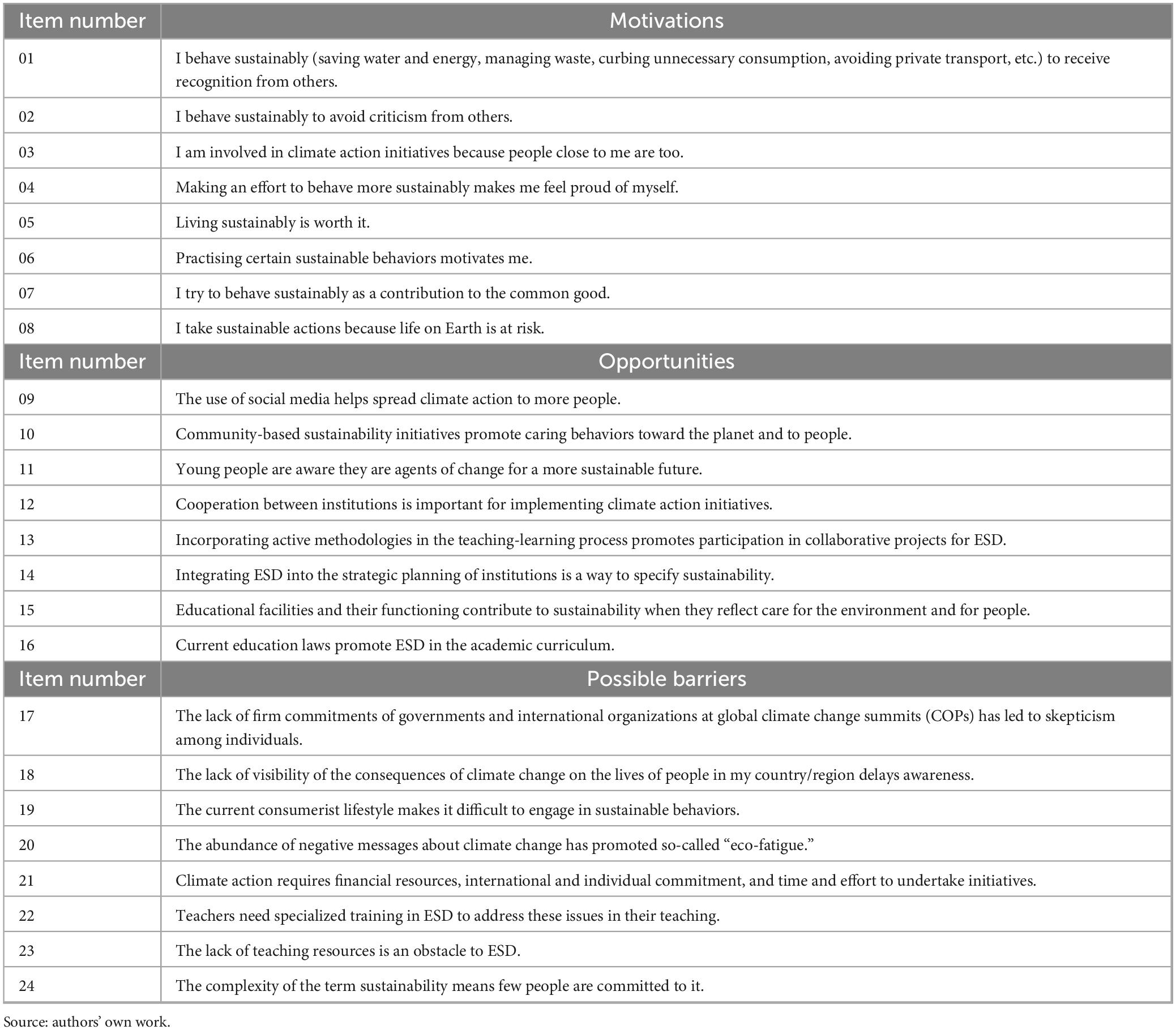

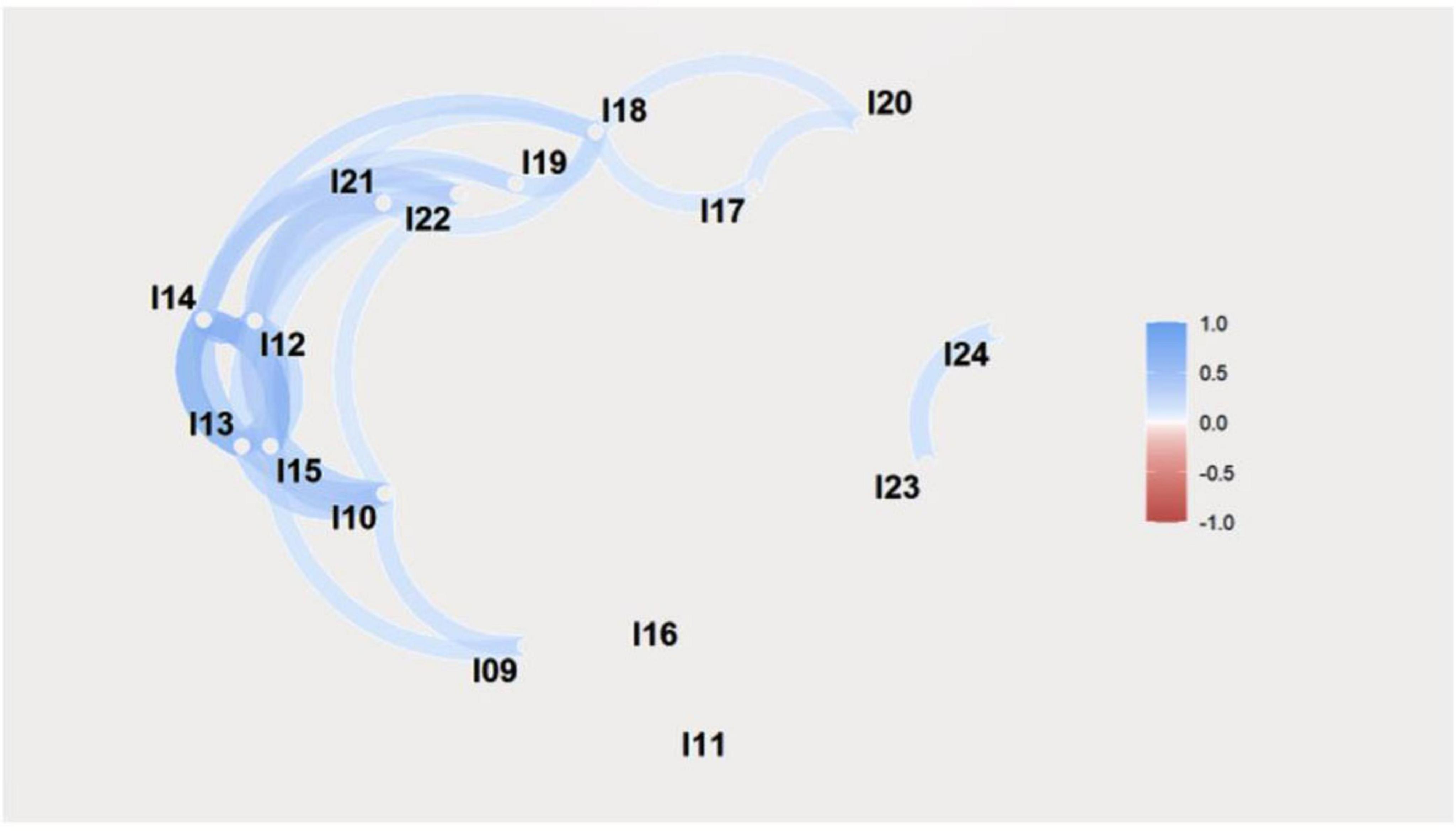

Table 1 includes 24 items, eight for each of the three variables (motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers) to be answered in accordance with the degree of agreement using a Likert scale that includes the following options: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree and strongly disagree.

Table 1. Questionnaire items on motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

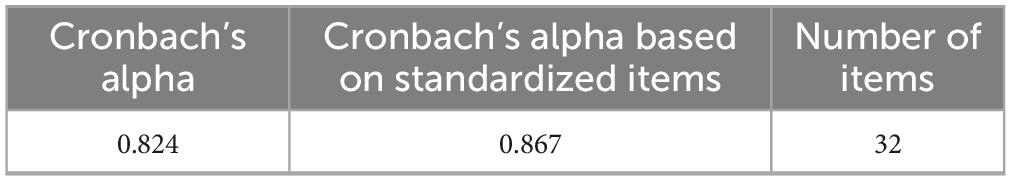

The validity, relevance, and pertinence of the scale were tested by means of the opinion of over 10 experts in ESD and motivation. All of them are teachers in different faculties at three Spanish universities. Using a table with 24 items, they wrote their suggestions with regard to the proper understanding of the statements, repetitions, and omissions of key aspects in each of the three variables. After receiving their comments, the instrument was redesigned. Some of the items were eliminated, the wording of others was improved, and the concept of transcendent motivation was included. An online pilot test was carried out with 45 university teachers, and, using their responses, Cronbach’s alpha, which determines the internal consistency of the questionnaire, was calculated. The result obtained was 0.824, which indicates the survey is reliable (see Table 2).

To assess the reliability or internal consistency of each factor in the questionnaire, McDonald’s Omega coefficient (ω) was calculated using the responses of the 150 teachers. The results obtained were as follows: motivations (ω = 0.898), opportunities (ω = 0.954), and barriers (ω = 0.815).

According to standard psychometric criteria, values of ω ≥ 0.90 indicate excellent internal consistency (as observed in the opportunities variable), while values between 0.80 and 0.89 reflect good internal consistency (as in motivations and barriers) (Ventura-León and Caycho-Rodríguez, 2017).

Sample and data collection

The self-completion questionnaire in digital format was distributed by e-mail to a number of teachers in Spain, mainly from Catalonia (69% of the total) that work at educational institutions from early childhood to university, and that have previous experience in ESD. A non-probability sampling method was used, consisting of Spanish teachers with experience in ESD who voluntarily agreed to participate during the data collection period. Although the aim was for teachers with experience in ESD from all over Spain and from all education levels to respond to the questionnaire, higher education teachers from Catalonia that were close to the authors responded spontaneously.

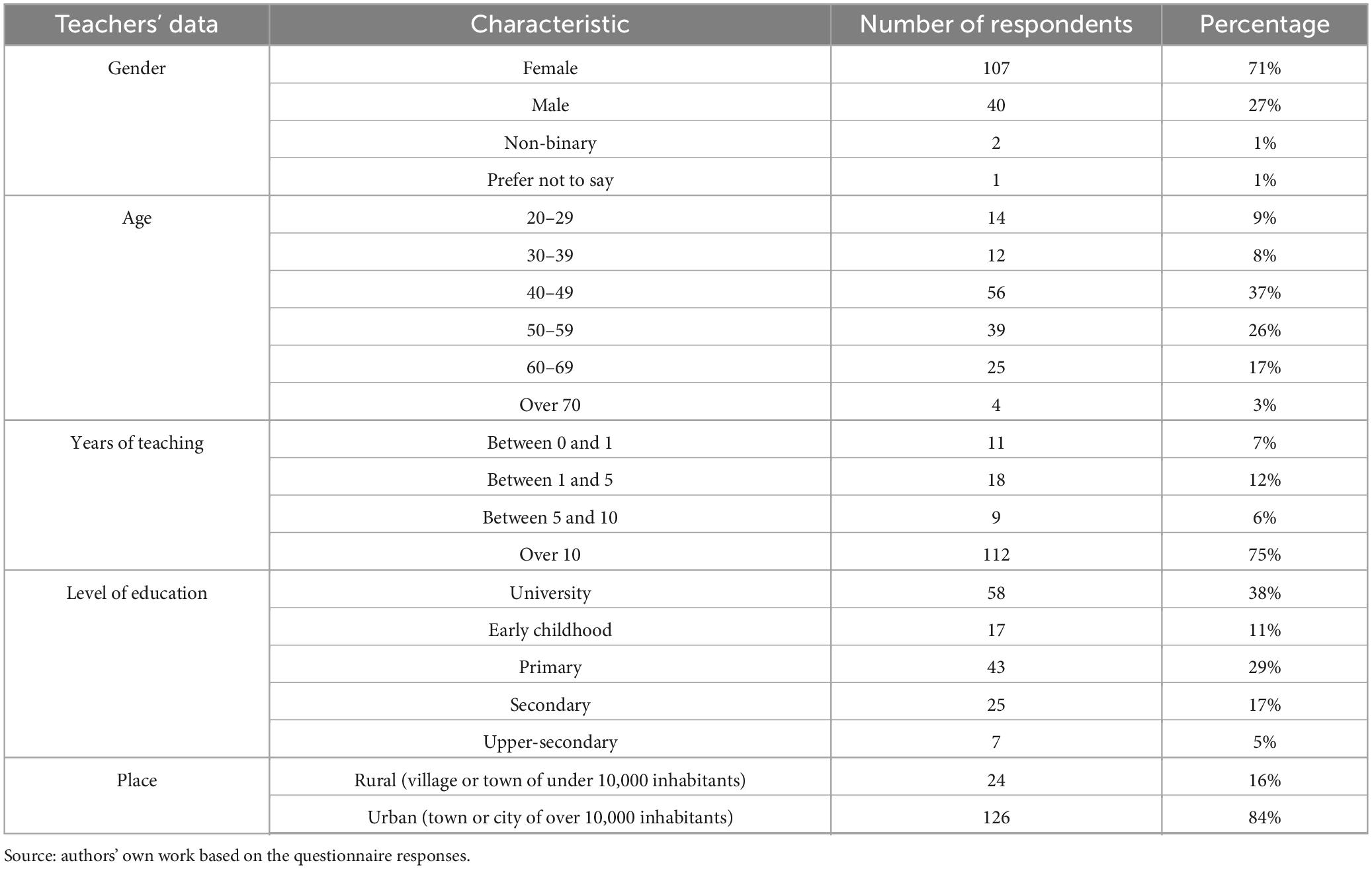

Over a period of one and a half months, between March and April 2024, responses from 150 teachers were received. The participants gave their written consent for their personal data and responses to be processed anonymously in this research project. The characteristics of the respondents who made up the sample are included in Table 3.

Data analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out for each of the variables using the results obtained. For each of the 24 items, the percentage obtained for the five levels of agreement on the Likert scale was calculated. This allowed us to see whether the responses were spread out or concentrated in some of the response options.

The relationships between the items of the three variables were then examined using Spearman’s rank because they had a non-parametric distribution. In this analysis, correlations with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. They were classified by magnitude, considering those with a positive correlation coefficient r equal to or greater than 0.50 as strong.

This statistical technique was implemented following the methodology described by Kuckartz et al. (2013). It enabled finding consistent relationships between items.

To visualize the correlations identified, the network analysis software was used. It represents each variable as a node and the relationships between them by means of lines. The proximity between the nodes indicates the strength of the correlation, while the color of the lines indicates if the relationship is positive (blue) or negative (red).

Results

The analysis of the results of the responses to the questionnaire from the 150 participating teachers provides insights that may contribute to pre-service and in-service teacher training in ESD and climate change. Some of the results could also be considered when including these topics in education curricula and public policies. In subsequent studies, the results could be analyzed in accordance with the education level at which the teachers teach. The contributions could hence be more specific.

The participating teachers’ most significant responses, divided into motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers regarding ESD and climate change, are described below.

Results of the “motivations” variable

With regard to motivations, there were items referring to extrinsic, intrinsic, and transcendent motivations. The responses related to extrinsic motivations vary depending on the type of impetus or driving force. Recognition from others is an important drive, while criticism from others is not. The “group effect,” i.e., acting in a certain way because others do so is a relevant impetus only for some. As shown in Figure 1, in item 01, 79% of the teachers strongly agree or agree that recognition from others influences sustainable behavior. However, possible criticism from others is not a factor that influences sustainable behavior. In item 02, 78% of the sample say they strongly disagree or disagree that negative opinions of others influence their actions. As for being involved in activities related to climate action because people close to them are too, the answers are spread out: 24.7% neither agree nor agree, 48% disagree or strongly disagree, and 27.3% agree or strongly agree in item 03.

Intrinsic motivations could be considered powerful to encourage people to adopt sustainable behaviors. This can be seen in the results of items 04 and 06 shown in Figure 1. In these two items, the strongly agree and agree responses are over 80%. The first item, 04, refers to feeling proud of oneself in making an effort to behave more sustainably and scores 85.3%. The second item, 06, is about how practising sustainable behaviors is motivating, and 87.3% tick the options of strongly agree or agree.

The motivations perceived to be the most “powerful” are the transcendent ones, in which all three items obtain over 90% of strongly agree and agree responses. This is recognized in items 05, 07, and 08 in Figure 1. The item that attains the highest degree of agreement, 97.3% of strongly agree or agree responses, is the one related to contributing to the common good (item 07). The item with the second highest degree of agreement is 05, which states that it is worth living sustainably, obtaining 95.3% strongly agree or agree responses. Finally, the item on whether sustainable actions are taken because life on Earth is at risk (item 08) reaches 92.7% agreement, 48.7% strongly agreeing, and 44% agreeing.

These results show that teachers, in general, share the same hierarchy of motivations toward sustainability: first transcendent motivations, then intrinsic, and finally extrinsic motivations.

The predominance of transcendent motivations might show that teachers have a sense of ethics, and a commitment to the common good. Furthermore, considering how important intrinsic motivations are to them, it can be deduced that most teachers have internalized sustainability as a value, and require less energy or extrinsic force to engage in sustainable behavior.

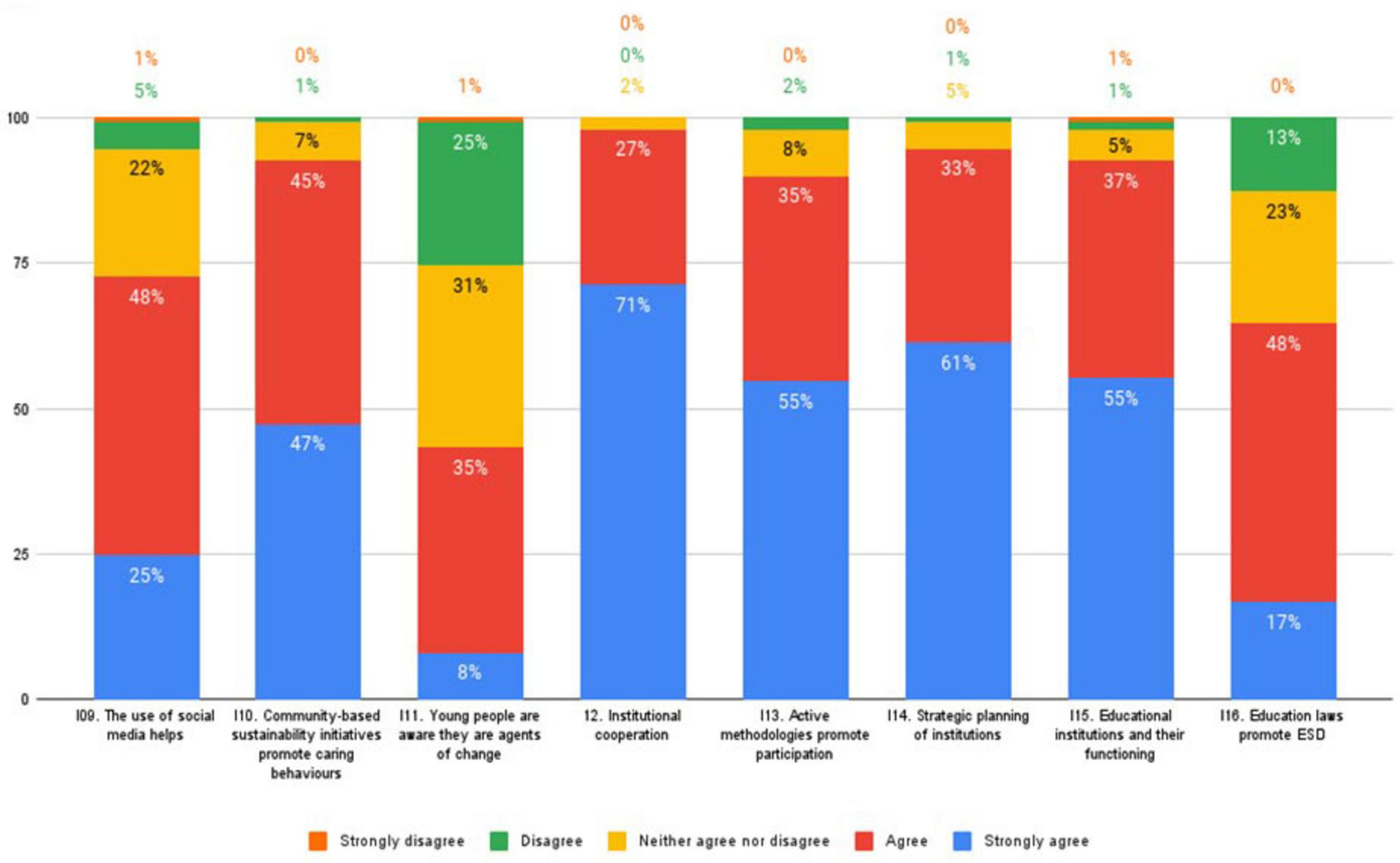

Results of the “opportunities” variable

As shown in Figure 2, in the sample as a whole, 99% of the teachers maintain cooperation between institutions is the most important opportunity to be considered for climate action initiatives (item 12). Figure 2 also identifies four items the 150 respondents consider to be a driving force of ESD, attaining 90% of strongly agree and agree responses. These items are number 10, community-based sustainability initiatives that promote caring behaviors; 13, incorporating active methodologies in the teaching-learning process; 14, integrating ESD into the strategic planning of institutions; and 15, educational facilities and their functioning that contribute to sustainability when they reflect care for the environment and for people.

Conversely, they do not consider youth to be agents of change for a more sustainable future as a significant opportunity (item 11). Responses to this statement ranged from strongly disagree to disagree (25%), neither agree nor disagree (31%), and strongly agree to agree (43%). Regarding the fact that current education laws promote ESD (item 16), 65% of the teachers strongly agree or agree (see Figure 2).

From the above, it can be inferred that most teachers consider current educational program offer several opportunities for ESD. According to the latest education laws (both at state and regional level), working on sustainability or eco-social skills at all education levels is recommended.

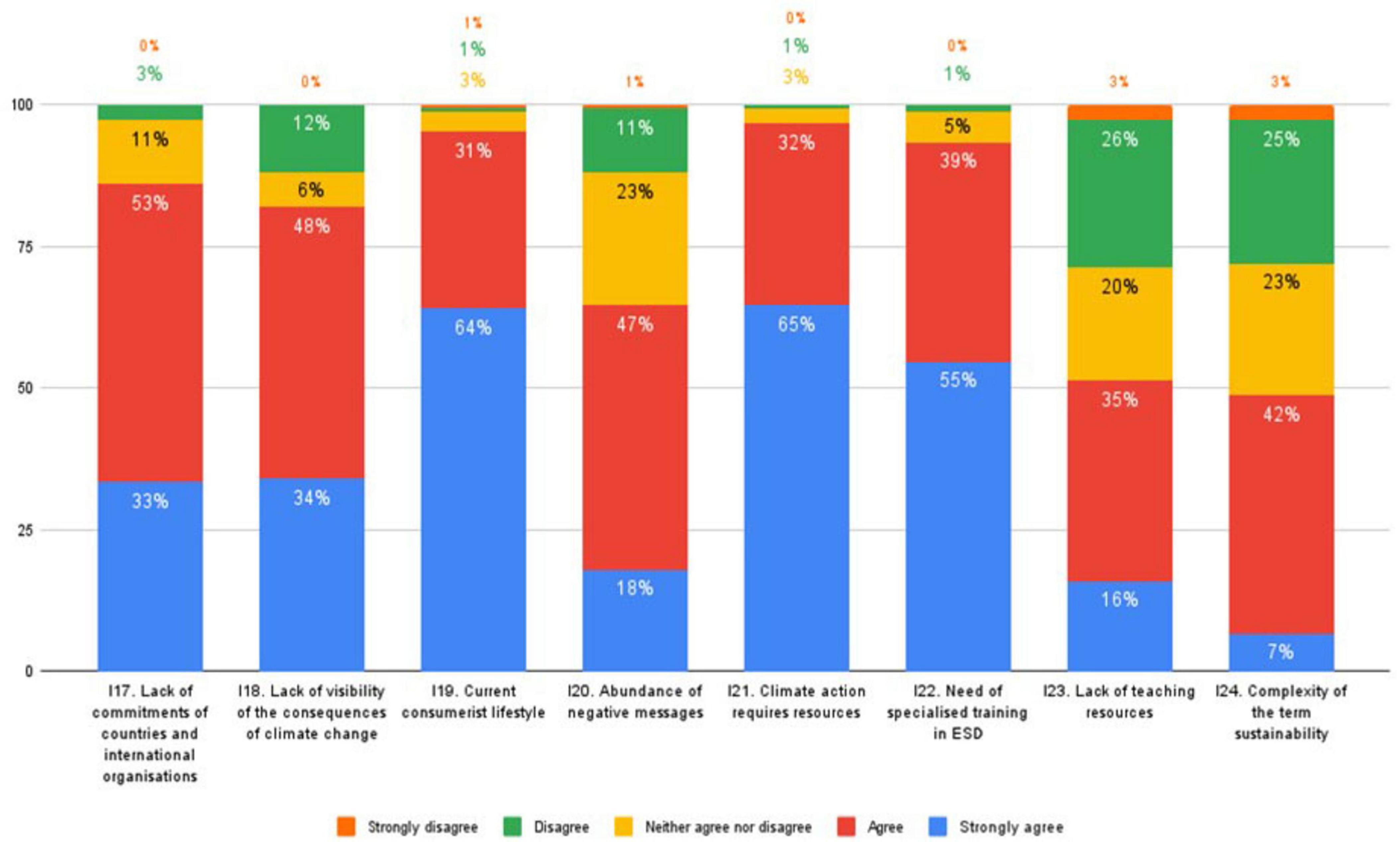

Results of the “barriers” variable

The analysis of the results of the items on possible barriers related to ESD shown in Figure 3 reveals the major barrier encountered was item 21, which refers to the fact that climate action requires commitments at all levels for initiatives to be undertaken. A total of 97% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this. The agreement in this item depends on the age of the respondents. The older the respondents are, the more strongly they agree. Greater diversity of opinions is found in younger respondents. This may be because teachers with more years of experience have stronger motivations, and are more convinced of the need for commitment to climate action. Also worthy of note is the high number of participants, 96%, that agree or strongly agree with item 19, which states that the current consumerist lifestyle makes sustainable behavior difficult, and, in item 22, 94% agree or strongly agree that teachers need specialized training in ESD.

Teachers also see the lack of firm commitments of governments and international organizations at world summits (item 17), and the lack of visibility of the consequences of climate change (item 18) as barriers. Figure 3 shows that 86% of the respondents strongly agree or agree with the first item, and 81% with the second.

There is some disparity of opinion in item 20, which concerns eco-fatigue. As can be seen in Figure 3, 65% of the respondents say they agree or strongly agree, and 12% disagree. Similarly, in item 23, which refers to the lack of teaching resources as an obstacle or barrier to ESD, 52% agree, while 29% disagree. In item 24, the complexity of the term sustainability does not seem to be one of the most important barriers for the majority of teachers. 49% say it is a barrier, while 28% do not consider it to be a barrier.

Results of the correlations between variables

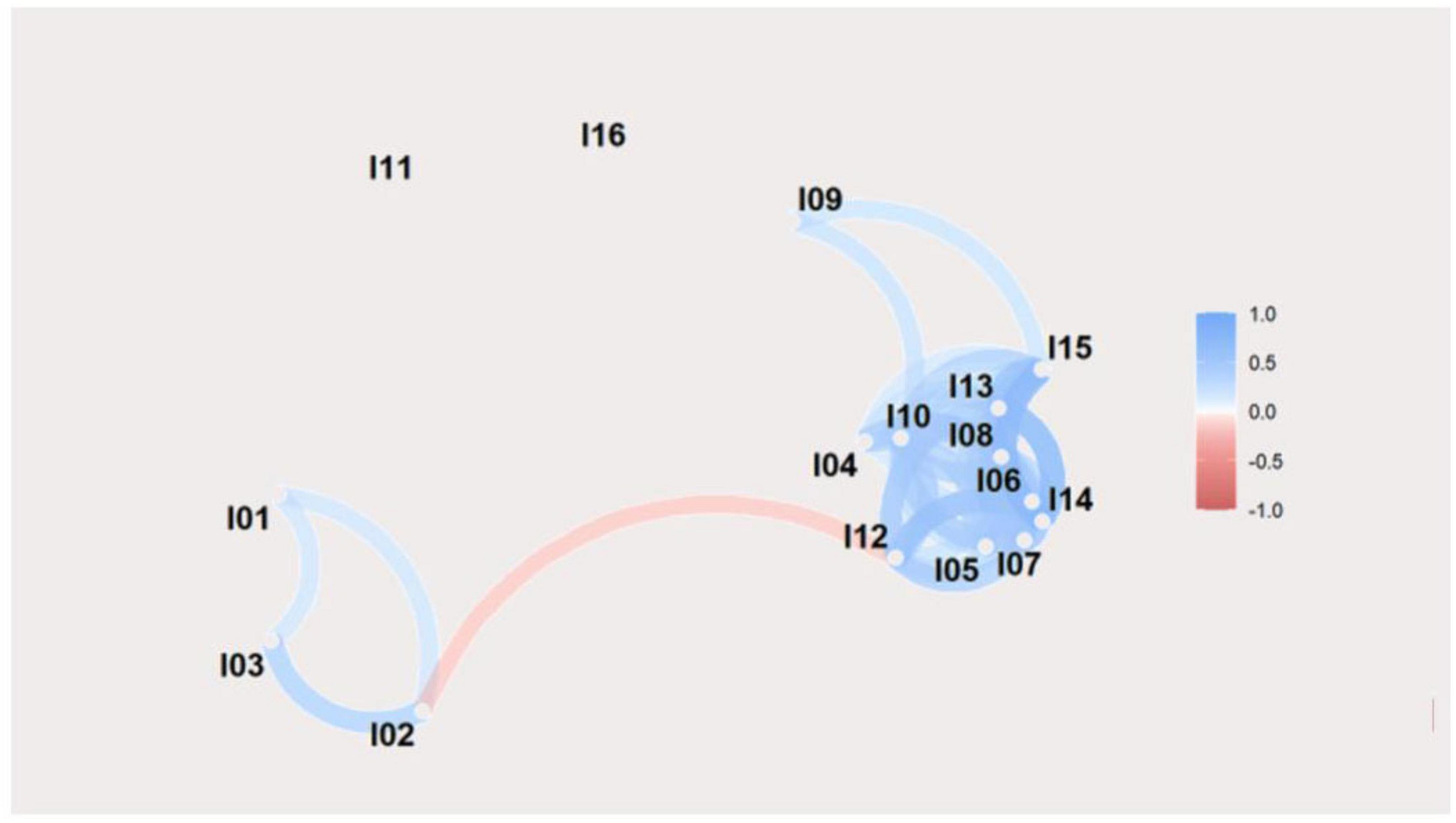

When analyzing possible correlations between the results of the motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers related to ESD, significant correlations were only found between motivations and opportunities, and between opportunities and possible barriers. The correlations between motivations and possible barriers were not significant. In other words, no consistent relationships were found between these items. Significant correlations are those that have a positive direction with an r-value between 1 and 0.5, and which appear as close nodes and blue lines (positive relationship) in Figures 4, 5.

Figure 4. Correlations between motivations and opportunities for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Items 01 to 08 are related to motivations and items 09 to 016 are related to opportunities. Source: authors’ own work.

Figure 5. Correlations between opportunities and potential barriers for Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Items 09 to 16 are linked to opportunities, and those from 17 to 24 to possible barriers. Source: authors’ own work.

The lack of correlation between motivations and potential barriers can be explained by the fact that the teachers who responded to the questionnaire are experienced in ESD, and have intrinsic motivations. Their convictions are hence stronger than the obstacles they encounter along the way. The purpose of ESD is so valuable to them that it helps them overcome potential difficulties.

The eight significant correlations between motivations and opportunities are shown in Figure 4 between the following variables:

Practising certain sustainable behaviors is motivating and integrating ESD into the strategic planning of institutions (I06 and I14 with r = 0.54).

The transcendent motivation item in which the teachers recognize they engage in sustainable behaviors as a contribution to the common good (I07) correlates with the following opportunities: the existence of community-based sustainability initiatives (I10) (r = 0.56); cooperation between institutions (I12) (r = 0.52); integrating ESD into the strategic planning of institutions (I14) (r = 0.55); and finally, educational facilities and their functioning reflecting care for the environment and for people (I15) (r = 0.53).

The transcendent motivation item that states sustainable actions are taken because life on Earth is at risk (I08) has positive correlations with the following opportunities: the existence of community-based sustainability initiatives that promote caring for the planet and for people (I10) (r = 0.5), and educational facilities and their functioning reflecting care for the environment and for people (I15) (r = 0.5).

The significant correlation between opportunities and possible barriers appears in only one case, which is shown in Figure 5. It is the average positive relationship (r = 0.46) between cooperation between institutions for effective ESD or climate action initiatives (I12) and the need for financial resources, international and individual commitment, time and effort (I21).

Discussion

The analysis of the results obtained helps us answer the research objectives set out: (1) identify teachers’ self-reported motivations for ESD; (2) explore the opportunities and barriers teachers perceive with regard to ESD, and (3) analyze possible correlations between the above variables.

With respect to the first research objective on teachers’ motivations, the results show that teachers with experience in ESD have all three types of motivations (extrinsic, intrinsic, and transcendent) as forces to practise sustainable behaviors. With little or no motivation, students could hardly be “enthused” (UNESCO, 2022b; Mulder et al., 2015). However, when assessing the different motivations, the three items related to transcendent motivations (items 05, 07 and 08 in Figure 1) have the greatest weight, especially the desire to contribute to the common good, where 97% of the 150 respondents strongly agree or agree. This result is in line with what Howell and Allen (2019) found in their research on the motives teachers in England had to mitigate climate change. To them, social justice is the strongest transcendent motivation for climate action or sustainable behavior. From this evidence, it can be concluded that the consequences of one’s own behavior, directly or indirectly, both on other people and on the natural environment, are the most important reasons not to carry out certain actions that could harm them. It seems that, in order to achieve behavior changes, instead of working on external rewards or incentives, that is, extrinsic motivations, it would be better to focus on promoting care for others and for what surrounds us, as Francis (2015) points out. Teachers, and, of course, learners, need to have intrinsic and transcendent motivations in favor of climate action and sustainability if they want to contribute to a more sustainable world through their behavior.

Regarding the second research objective on opportunities, 98% of the teachers that participated in the questionnaire stress cooperation and synergy between institutions committed to ESD (item 12). This is similar to what is stated in the UNESCO report (UNESCO, 2022b). In addition to cooperation, Tilbury’s (2011) systemic view, or the consistency of educational institutions with sustainability, is also important for 94% of the teachers, as it is essential for integral sustainability education (item 14). On the other hand, as Eichinger et al. (2022) point out, teachers want more opportunities to develop sustainability competencies and values to achieve both individual and societal transformation.

As for the most important barriers perceived regarding ESD, the survey results highlight the commitments and resources required for sustainable behavior (97% strongly agree or agree with item 21), and the current consumerist lifestyle of Western societies (95% strongly agree or agree with item 19). Although the latter is not directly related to teaching, it is to be expected that if students do not want to change habits toward more frugal behavior, they may be less receptive to developing competencies linked to climate action. This could explain why young people do not see themselves as agents of change. They are less willing to change their lifestyle, and expect solutions to come from the state or from companies.

In accordance with Blanco-Portela et al. (2018), Albareda-Tiana et al. (2017), Veiga-Avila et al. (2017), 94% of the teachers with experience in ESD point out that the lack of specialized training in ESD is a major obstacle to transmitting ESD (item 22). They also agree that the commitment of governments and international organizations through agreements, conventions, or laws is necessary (86% strongly agree or agree with item 17).

Although Blanco-Portela et al. (2018) indicate the conceptual difficulty around the term sustainability is an important barrier, in the questionnaire distributed to the 150 teachers, less than 50% consider it an obstacle to sustainable behaviors. This may be explained by the fact that the respondents are teachers with experience and knowledge of ESD.

Concerning the third research objective, when reviewing the correlations between motivations, opportunities, and barriers, it is worthy of note that only intrinsic and transcendent motivations have significant correlations with opportunities (r = equal to or greater than 0.5, positive, and grouped). The strongest relationships are between sustainable behaviors for the common good (item 07), the existence of community-based sustainability initiatives (item 10), and integrating sustainability into the strategic planning of institutions (item 14).

Extrinsic motivations are left out, which confirms that only those who seek their own wellbeing or the wellbeing of others engage in caring behaviors, are willing to change certain behaviors, even if it takes effort, and appreciate what contributes to this end (community-based initiatives, cooperation between institutions, integrating sustainability into strategic planning, etc.). The sum of motivations and opportunities for ESD could lead to changing mindsets and adopting pro-sustainability behaviors, as Ruiz Martín (2021), Francis (2015) maintain.

Conclusion

Based on this exploratory study conducted through a self-completion questionnaire applied to 150 teachers with previous experience in ESD —focusing on their perceptions of motivations, opportunities, and possible barriers for ESD in the context of early childhood, compulsory, and higher education—the following conclusions can be drawn. They should be interpreted bearing in mind this is a correlational study, but provides relevant evidence of the relationships between the variables studied. The importance of reinforcing intrinsic and transcendental motivations for ESD, such as caring for life and the pursuit of the common good, is highlighted, as the results suggest that these are more influential than external incentives. Firstly, it highlights the promotion of sustainable behaviors through greater awareness and the development of intrinsic motivations and values. Secondly, it is important to stress the importance of promoting teacher training in sustainability and the integration of ESD objectives in educational institutions, as well as in public policies and in teacher training centers, which could facilitate their practical incorporation into educational environments and improve educational opportunities in sustainability-related topics. Finally, the study emphasizes the need to address the barriers associated with consumerist lifestyles and lifestyle changes, which involves overcoming practical and attitudinal challenges in the implementation of ESD. In this regard, institutional cooperation and coherence between strategic planning, infrastructure and environmental management in institutions appear to be essential to ensure that these motivations are translated into concrete actions within the education system.

Limitations

Although the research was carried out with 150 Spanish teachers that have previous experience in ESD, the results could be replicated and transferred to other contexts, given the cultural richness and complex reality of Spain with its cultural and linguistic variety, socio-economic levels, and high percentage of vulnerable population. The sample was plural in terms of age, gender, and the level of education in which the participants teach. Therefore, the lessons drawn from the research may be useful for those who want to thoughtfully apply ESD in other contexts. Furthermore, the fact that most of the participants in the study have been teaching for over 10 years suggests their responses are based on experience and maturity, providing them with a more universal value.

Despite the above qualities, one of the limitations of this study is that it does not explore the perceptions, experiences, and context of the participants in depth, as it is a quantitative study. Future research should therefore incorporate qualitative or mixed methodologies to complement the findings and offer a more comprehensive view. It should also segment the results in accordance with the education level at which teaching takes place in order to refine the study and narrow down the proposals. In spite of these limitations, the results obtained provide valuable information for professionals who wish to continue promoting ESD.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. The research protocol received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and provided their written informed consent prior to completing the questionnaire.

Author contributions

MV-A: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA-T: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MG-M: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. MF: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors are grateful for the financial support received (Grant 00081 CLIMA 2024) from the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR) of the Catalan Government. The name of the project is EDUCLIMA: Mesurar l’impacte positiu de les accions fetes per mitigar el canvi climàtic. Educació climàtica a la Universitat i des de la Universitat (Measuring the positive impact of actions taken to mitigate climate change. Climate education at the university and from the University).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the survey respondents and to four reviewers for their valuable comments. We would also like to thank Ann Swinnen for the feedback and helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albareda-Tiana, S., Fernández-Morilla, M., Mallarach-Carrera, J. M., and Vidal-Ramèntol, S. (2017). Barreras para la sostenibilidad integral en la Universidad [Barriers to comprehensive sustainability at the University]. Rev. Iberoamericana Educ. 73, 253–272. Spanish. doi: 10.35362/rie730301

Aslam, A., and Rawal, S. (2019). The role of intrinsic motivation in Education System Reform. Oxford Partnership for Education Research and Analysis. London: STiR Education.

Barth, M., and Rieckmann, M. (2011). Academic staff development as a catalyst for curriculum change towards education for sustainable development: An output perspective. J. Cleaner Production 26, 28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.12.011

Batlle, R. (2013). El aprendizaje-servicio en España [Service-learning in Spain]. El contagio de una revolución pedagógica necesaria [The contagion of a necessary pedagogical revolution]. Spanish. Barcelona: PPC

Bianchi, G., Pisiotis, U., Cabrera Giraldez, M., Bacigalupo, M., and Punie, Y. (2022). GreenComp. “The European sustainaibility competence framework”, EUR 30955 EN. Spanish. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, JRC128040 doi: 10.2760/13286

Blanco-Portela, N., Poza-Vilches, M. D. F., Junyent-Pubill, M., Collazo-Expósito, L., Solís-Espallargas, M. D. C., and Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. (2020). Estrategia de investigación-acción participativa para el desarrollo profesional del profesorado universitario en educación para la sostenibilidad: “Academy sustainability Latinoamérica” (ACSULA) [Participatory action research strategy for the professional development of university professors in sustainability education: “Academy sustainability latin America” (ACSULA)]. Profesorado Rev. Curriculum Formación Profesorado 24, 99–123. Spanish. doi: 10.30827/profesorado.v24i3.15555

Blanco-Portela, N., R-Pertierra, L., Benayas, J., and Lozano, R. (2018). Sustainability leaders’ perceptions on the drivers for and the barriers to the integration of sustainability in Latin American higher education institutions. Sustainability 10:2954. doi: 10.3390/su10082954

Brundiers, K., Barth, M., Cebrián, G., Cohen, M., Diaz, L., Doucette-Remington, S., et al. (2021). Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustainability Sci. 16, 13–29. doi: 10.1007/s11625-020-00838-2

Busquets, P., Segalas, J., Gomera, A., Antúnez, M., Ruiz-Morales, J., Albareda-Tiana, S., et al. (2021). Sustainability education in the Spanish higher education system: Faculty practice, concerns and needs. Sustainability 13:8389. doi: 10.3390/su13158389

Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) (2024). European State of the climate 2023, Full report: Climate.copernicus.eu/ESOTC/2023. Bonn: Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Eichinger, M., Bechtoldt, M., Bui, I. T. M., Grund, J., Keller, J., Lau, A. G., et al. (2022). Evaluating the public climate school—A school-based programme to promote climate awareness and action in students: Protocol of a cluster-controlled pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8039. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138039

El País (2024b). Sólo con un uso sostenible de los recursos se podrá acabar con la pobreza. Madrid: El País.

Gorski, A.-T., Ranf, E.-D., Badea, D., Halmaghi, E.-E., and Gorski, H. (2023). Education for sustainability—Some bibliometric insights. Sustainability 15:14916. doi: 10.3390/su152014916

Gutiérrez, J., Benayas, J., and Calvo, S. (2006). Educación para el desarrollo sostenible: Evaluación de retos y oportunidades del decenio 2005-2014 [Education for sustainable development: Assessment of challenges and opportunities for the decade 2005-2014]. Rev. Iberoamericana Educ. 40, 25–69. Spanish. doi: 10.35362/rie400781

Gutiérrez, M. M., and Blanco, N. (2023). Educación para el desarrollo sostenible y percepción de la comunidad universitaria: Caso Universidad Simón Bolívar [Education for sustainable development and the perception of the university community: The case of Simón Bolívar University]. Rev. Educ. Ambiental Sostenibilidad 5:10. Spanish. doi: 10.25267/Rev_educ_ambient_sostenibilidad.2023.v5.i1.1202

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R., Mayall, E., et al. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet Health 5:e863–e873. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3

Howell, R. A., and Allen, S. (2019). Significant life experiences, motivations and values of climate change educators. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 813–831. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2016.1158242

IPCC (2023). “Sections,” in Climate change 2023: Synthesis report. contribution of working groups I, II and III to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, eds Core Writing Team, H. Lee, and J. Romero (Geneva: IPCC), 35–115. doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

Kuckartz, U., Rädiker, S., Ebert, T., and Schehl, J. (2013). Statistik: eine verständliche einführung. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Leal, F. W., Will, M., Shiel, C., Paço, A., Farinha, C. S., Lovren, V. O., et al. (2021). Towards a common future: Revising the evolution of university-based sustainability research literature. Int. J. Sustainable Dev. World Ecol. 28, 503–517. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2021.1881651

Mercado, M., and Teso, G. (2024). Ética de la comunicación ambiental y del cambio climático [Ethics of environmental and climate change communication]. Spanish. Tokyo: Tecnos

Ministerio para la Transició,n Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (2024). Informe mensual de seguimiento de la situación de sequía y escasez: Mayo de 2024. Subdirección general de planificación hidrológica, dirección general del Agua, secretaría de estado de medio ambiente [Monthly drought and shortage monitoring report: May 2024. subdirectorate general for hydrological planning, directorate general for water, secretariat of state for the environment]. Spanish. EspañaCórdoba.

Miranda, L. (2024). La gran noticia esperada: el agua potable vuelve al Norte de Córdoba [The long-awaited big news: drinking water returns to northern Córdoba]. Spanish. España.

Mulder, K. F., Ferrer, D., Segalas Coral, J., Kordas, O., Nikiforovich, E., and Pereverza, K. (2015). Motivating students and lecturers for education in sustainable development. Int. J. Sustainability High. Educ. 16, 385–401. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-03-2014-0033

Pérez-López, J. A. (1997). Liderazgo. ediciones folio [Leadership. Folio editions]. Spanish. Grao: Barcelona

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101860. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sánchez-Carracedo, F., Sureda, B., Moreno-Pino, F. M., and Romero-Portillo, D. (2021). Education for sustainable development in Spanish engineering degrees: Case study. J. Cleaner Production 294, 126322. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126322

Scherak, L., and Rieckmann, M. (2020). Developing ESD competences in higher education institutions-sta? training at the university of vechta. Sustainability 12:10336. doi: 10.3390/su122410336

Tilbury, D. (2011). Higher education for sustainability: A global overview of commitment and progress. Higher Education’s Commitment to sustainability: from understanding to action. Palgrave Macmillan, 18–28.

UNESCO (2014). Hoja de ruta de la UNESCO para la implementación del programa de acción mundial sobre educación para el desarrollo Sostenible [UNESCO roadmap for the implementation of the global action programme on education for sustainable development]. Spanish. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2020). Educación para el desarrollo sostenible. Hoja de ruta. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374896

UNESCO (2022a). Aprender por el planeta: revisión mundial de cómo los temas relacionados con el medio ambiente están integrados en la educación [Learning for the planet: A global review of how environmental issues are integrated into education]. Spanish. Paris: UNESCO

UNESCO (2022b). El profesorado opina: motivación, habilidades y oportunidades para enseñar la educación para el desarrollo sostenible y la ciudadanía mundial [Teachers’ opinions: Motivation, skills, and opportunities for teaching education for sustainable development and global citizenship]. Spanish. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2023). Informe sobre la aplicación de la Educación para el Desarrollo Sostenible (EDS) para 2030 y la Declaración de Berlín [Report on the implementation of education for sustainable development (ESD) for 2030 and the Berlin Declaration]. Spanish. Paris: UNESCO

UNESCO & Monitoring and Sustainability Education Research Institute, University of Saskatchewan (2024). Education and climate change: Learning to act for people and planet. Paris: UNESCO.

Varela-Losada, M., Arias-Correa, A., Pérez-Rodríguez, U., and Vega-Marcote, P. (2019). How can teachers be encouraged to commit to sustainability? Evaluation of a teacher-training experience in Spain. Sustainability 11:4309. doi: 10.3390/su11164309

Veiga-Avila, L., Leal-Filho, W., Brandli, L., Macgregor, C. J., Molthan-Hill, P., Özuyar, P. G., et al. (2017). Barriers to innovation and sustainability at universities around the world. J. Cleaner Production 164, 1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.07.025

Ventura-León, J. L.Caycho-Rodríguez, T. (2017). El coeficiente omega: Un método alternativo para la estimación de la fiabilidad. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Niñez y Juv. 15, 625–627.

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., and Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Sci. 6, 203–218. doi: 10.1007/s11625-011-0132-6

Keywords: SDG4: EDS, SDG4: quality education, SDG13: climate action, motivations, opportunities, barriers

Citation: Vergara-Arteaga M, Albareda-Tiana S, Graell-Martín M and Fuentes Loss M (2025) Spanish teachers’ perceptions of motivations, opportunities, and barriers regarding Education for Sustainable Development: an exploratory study. Front. Educ. 10:1662244. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1662244

Received: 08 July 2025; Accepted: 15 August 2025;

Published: 08 September 2025.

Edited by:

Paitoon Pimdee, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, ThailandReviewed by:

Isaac Corbacho, University of Extremadura, SpainYonis Gulzar, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2025 Vergara-Arteaga, Albareda-Tiana, Graell-Martín and Fuentes Loss. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcela Vergara-Arteaga, bXZlcmdhcmFhQHVhbmRlcy5jbA==; bXZlcmdhcmFAdWljLmVz

Marcela Vergara-Arteaga

Marcela Vergara-Arteaga Silvia Albareda-Tiana2

Silvia Albareda-Tiana2