Abstract

Instructional leadership is vital for ensuring quality teaching and learning in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), particularly in Teacher Education Institutions (TEIs) that aim to sustain accreditation standards and enhance students' performance. This study was conducted from July 2023 to April 2024 in the Luzon Region, Philippines, aimed to develop a harmonized instructional leadership framework based on the best practices of six high-performing HEIs—two State Universities and Colleges (SUCs), two Private Institutions, and two Local Universities and Colleges (LUCs). Institutions were purposively selected based on stringent criteria, including accreditation status (PAASCU, AACCUP, ALCUCOA), ISO certification, Centers of Development/Excellence, national and global rankings, and consistent Licensure Examination for Teachers (LET) performance. Using a qualitative comparative multi-case study approach, data were gathered from 88 participants (administrators, faculty, and students) through validated semi-structured interviews, adding document analysis, and thematic analysis with intercoder validation. A panel of twelve (12) experts in leadership, management, curriculum, and instruction reviewed the framework. Findings led to a harmonized quality-assured instructional leadership framework with six phases (6) and twenty (20) interrelated components, promoting efficiency, adaptability, and continuous improvement. This structured, systematic and evidence-based guide supports instructional leaders in aligning institutional mechanisms with excellence standards, adaptable across diverse HEI contexts nationwide.

Introduction

Education is a vital driver of national development, and the quality of instruction in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) determines the competence, employability, and competitiveness of graduates. Around the world, quality assurance (QA) plays a pivotal role in operational management by guiding institutions to implement quality policies, aspirations, and directives (Qureshi and Ünlü, 2020). In the Philippine context, QA has become central to higher education reforms through accrediting agencies such as the Accrediting Agency of Chartered Colleges and Universities in the Philippines (AACCUP), Philippine Accrediting Association of Schools, Colleges and Universities (PAASCU), and Association of Local Colleges and Universities Commission on Accreditation (ALCUCOA), which aim to raise standards in Teacher Education Institutions (TEIs) and improve performance in the Licensure Examination for Teachers (LET). While these systems promote a culture of continuous improvement, disparities in governance, culture, and funding among State Universities and Colleges (SUCs), Private Institutions, and Local Universities and Colleges (LUCs) present challenges in sustaining consistent QA practices nationwide.

Globally, QA is fundamental to enhancing instructional techniques that foster analytical reasoning (Flavian, 2020) and is recognized for its role in knowledge creation, organizational learning, and stakeholder satisfaction (Basten and Haamann, 2018; Paniagua, 2019). It ensures services meet consumer needs and standards while fostering trust and loyalty. QA includes interactive strategies to reduce defects and shift focus from compliance to a quality culture aimed at continuous improvement in HEIs (Liu, 2019). However, regional variations in QA's application and limited evidence of its impact on educational quality persist, necessitating further research to establish a unified framework (Krooi et al., 2024).

Instructional leadership in HEIs involves leaders actively improving teaching and learning processes (Munna, 2023), fostering a shared understanding of learning, aligning performance with institutional vision, and engaging directly with curriculum and instruction (Shaked, 2023; Shaked and Benoliel, 2020). Yet higher education leaders often face difficulties enhancing instruction due to faculty autonomy and a limited focus on teaching quality (Townsend, 2019). QA supports instructional leadership by building teacher competence and performance standards (Wynne and Satchwell, 2020), but implementing QA systems presents challenges that require robust evaluation methods (Andriamiseza et al., 2023). Best practices link instructional leadership with QA, emphasizing cross-disciplinary participation and self-evaluation by academics (Abdallah and Musah, 2021).

Despite its potential, there remains no concrete process framework integrating QA and instructional leadership in TEIs (Cao and Li, 2014; Makhoul, 2019). This gap motivated the present study to document best practices from high-performing HEIs and develop a harmonized quality-assured instructional leadership framework that is structured, sustainable, and evidence-based for enhancing teaching quality, institutional performance, and continuous improvement across varied HEI contexts in the Philippines.

Conceptual framework

QA is a systematic method that ensures that services meet established standards. Instructional leadership focuses on the development of teaching and learning development (Díez et al., 2020). In HEIs, this entails fostering student competencies through an effective teaching-learning system that promotes both immediate and long-term success. Quality-assured instructional leadership integrates best practices with sound organizational structures, governance, and leadership to achieve institutional goals.

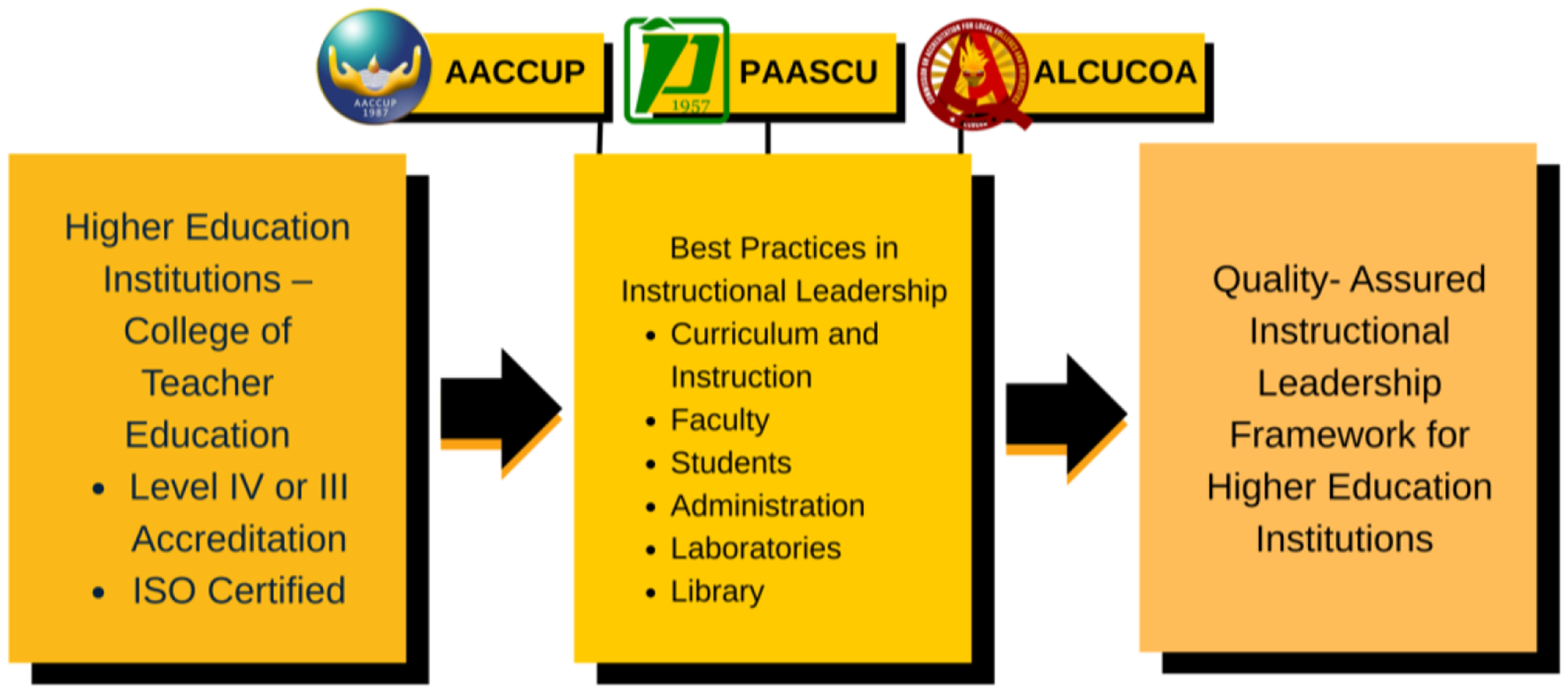

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of this study, which seeks to identify best practices and core processes in quality-assured instructional leadership across high-performing HEIs. The study serves as a foundation for the development of a proposed framework designed to sustain robust quality assurance mechanisms and enhance teaching and learning outcomes. Data were gathered through in-depth interviews and document analyses conducted in Level III and IV accredited and ISO-certified HEIs. Accreditation standards from key quality assurance bodies—namely the AACCUP for SUCs, PAASCU for private institutions, and the ALCUCOA for LUCs—were also examined.

Figure 1

Conceptual framework of the study.

This highlights shared parameters in instructional leadership such as curriculum and instruction, faculty, student services, administration, laboratories and libraries. These elements were analyzed to determine the foundational components of sustainable quality assurance practices in instruction.

This study contributes to the practice of instructional leadership by offering an evidence-based framework that institutional leaders, accreditation bodies, and policy-makers can utilize to reinforce quality standards in instruction. By synthesizing practices from exemplary HEIs and aligning them with accreditation benchmarks, the proposed framework provides evidence-based, structured, and adaptable guide for continuous instructional improvement. It enables institutions to benchmark their leadership practices, align resources with quality goals, and implement data-driven decision-making processes to elevate educational delivery and institutional effectiveness.

Methodology

Research design

This study employed a qualitative comparative method using a multi-case study approach, allowing a deeper understanding of how participants experienced and interpreted practices within their institutions. Qualitative research provides comprehensive and naturalistic insights, focusing on social units rather than on isolated factors (Cao and Li, 2014). It emphasizes detailed descriptive data, helping clarify participants' perspectives and the meanings they assign to the phenomena. Multi-case studies enhance robustness and reliability by replicating outcomes across cases (Ridder, 2017). This highlights the fact that evidence from multiple cases often yields more convincing and well-developed findings.

Participants

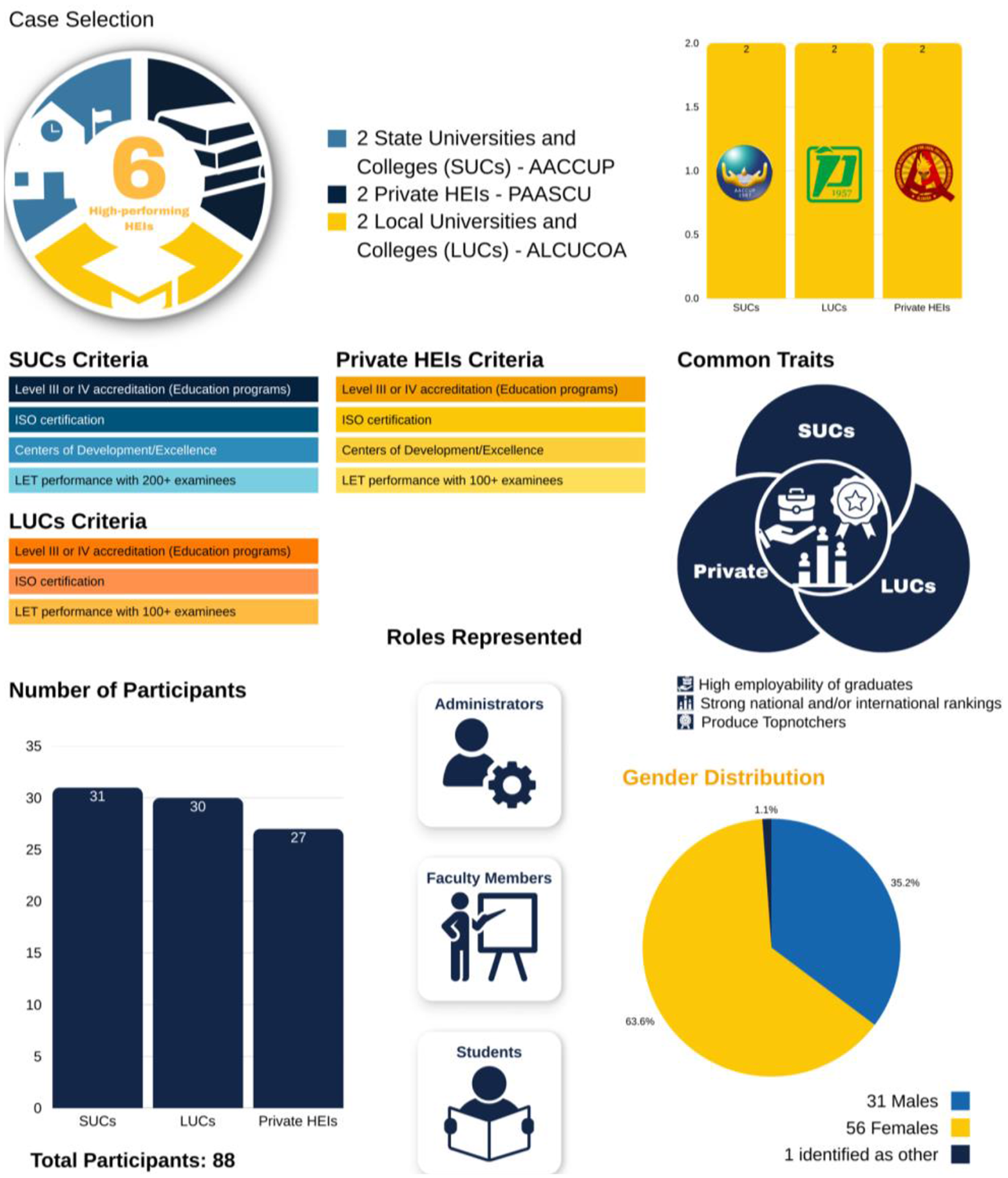

Figure 2 demonstrated the profiling covered six high-performing HEIs focusing on TEIs: two SUCs, two Private Institutions, and two LUCs. The PAASCU, AACCUP, and ALCUCOA standards guided the evaluation of instructional leadership. Additionally, purposive sampling, known for its selective approach, was used to identify participants based on their specific qualifications (Robinson, 2014). SUCs require Level III institutions, Level III or IV accreditation in education programs, ISO certification, center of development and/or center of excellence, and consistent LET performance with over 200 examinees. Private HEIs and LUCs had similar standards with varying LET participant counts, and LUCs did not have a center of development and/or center of excellence. The selected HEIs also demonstrated national and global rankings, high performance, and high employability.

Figure 2

Profiling of the participants.

This study involved 88 participants from six high-performing HEIs across three categories. Participants included administrators, faculty members, and students, with a gender distribution of 31 males, 56 females, and one identifying as other. SUC 1 had a total of 15 participants, comprising six administrators, four faculty members, and five students, whereas SUC 2 included 16 participants, with a balanced mix of administrators, faculty, and students. Private Institutions 1 and 2 collectively contributed 27 participants, with slightly higher representation from students and administrators. On the other hand, the LUCs accounted for 30 participants, with a notable female majority, particularly among administrators and students. The sample reflects diverse roles and perspectives, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of instructional leadership practices across institutions.

Instrumentation

The study used semi-structured interview guides aligned with PAASCU, AACCUP, and ALCUCOA accreditation parameters to capture instructional leadership practices. Additionally, institutional documents such as policy manuals, accreditation reports, and program performance records were gathered for document analysis to supplement interview data.

Data gathering and analysis process

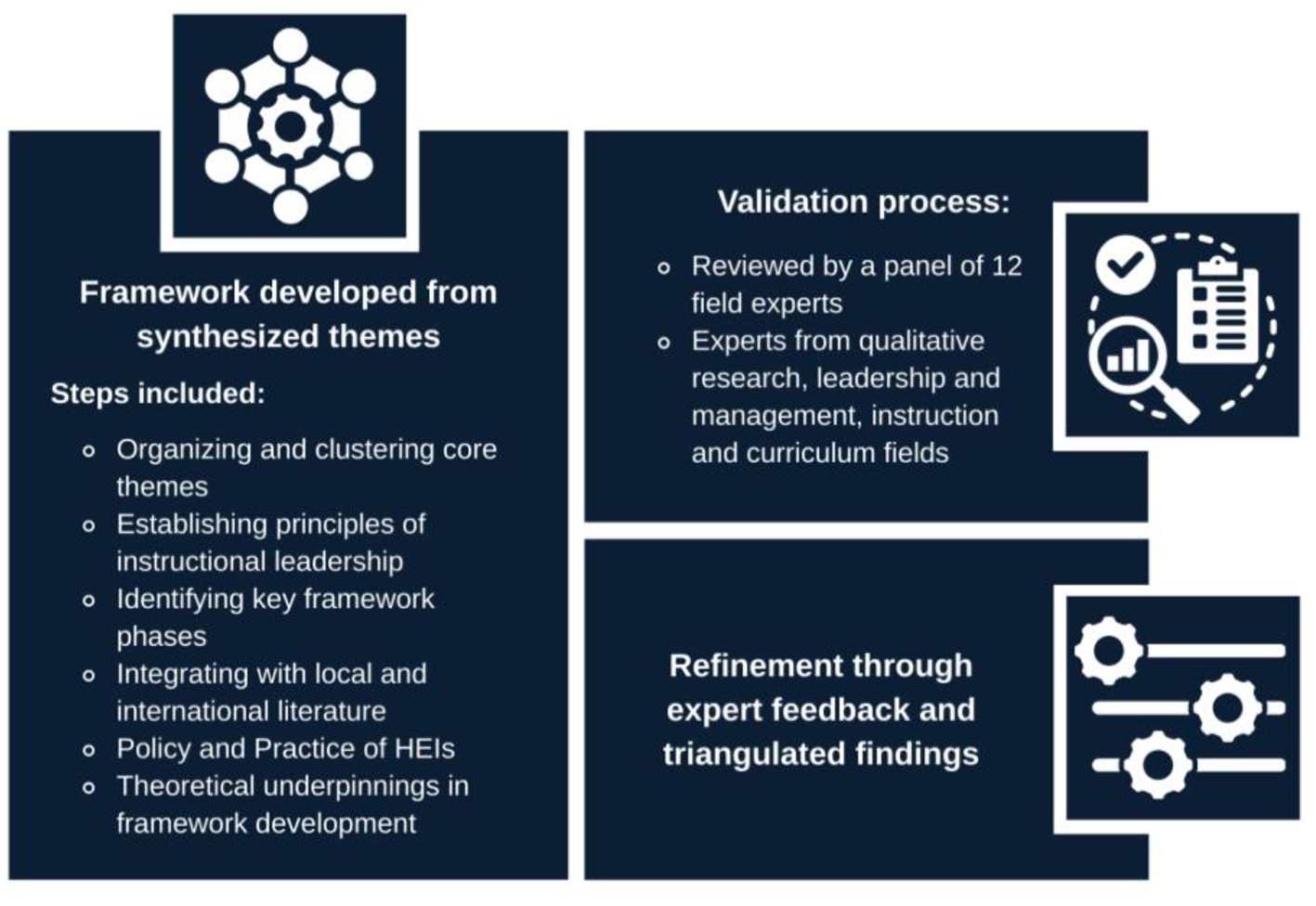

Interviews were conducted with administrators, faculty members, and students with signed informed consent (Supplementary material) from the six HEIs from July 2023 to April 2024 in the Luzon Region, Philippines. Figure 3 demonstrated that all interviews were transcribed, translated, and thematized. Document analysis was used to triangulate findings from the interviews. Thematic saturation was determined when no new insights emerged from the data.

Figure 3

Thematic analysis and data validation process.

This study fully complied with the University Code of Research Ethics and Guidelines for Review as stipulated in BOR Resolution No. U-2303 s. 2015, with REC-code 07212023-225-FR.

Additionally, thematic analysis was applied to identify patterns and themes within the data. Validation was achieved using multiple data sources (Campbell et al., 2020). Two intercoder analysts cross-checked the themes identified by the researcher to ensure consistency and confirm that the themes accurately represented the data.

Framework development and validation process

Figure 4 illustrated framework development process was based on identified themes, involving systematic organization and synthesis of patterns or concepts into a coherent structure that addressed the research objectives. Core principles of instructional leadership were anchored on HEI practices and policies, supported by related literature and studies.

Figure 4

Framework development and validation process.

Key phases of framework design were guided by the study objectives, showing how each phase was interrelated. Validation involved expert review and triangulation. A panel of twelve (12) field experts comprising practitioners and scholars with recognized expertise in quality assurance, educational leadership, management, curriculum, and instruction who scrutinized the framework's development, structure, and constructs. These experts practice their profession as leaders in their respective institutions, serve as accreditors in various accrediting agencies, hold doctoral degrees in educational leadership and management, contribute as curricularists in the field, engage as practitioners in the classroom setting, and publish research papers in the field of leadership and management.

Results and discussion

In analyzing the comparative data across the three categories of HEIs, several key themes emerged that were utilized in the development of a harmonized quality-assured instructional leadership framework. Each institutional category has the best practices, challenges, and areas for potential contributions to harmonization. This comparative analysis highlights the distinctive approaches that each institution adopts and their shared goals in various aspects.

Best practices in quality instructional leadership across participating HEIs

The best practices across participating HEIs revealed distinct approaches to instructional leadership, faculty qualifications, student learning, infrastructure, research, and institutional services, each reflecting their mandates and priorities.

Strategic and integrated leadership, SUCs emphasize structured governance aligned with CHED policies and accreditation standards, ensuring sustainability and excellence, as stated by the SUC faculty: “To maintain, sustain, and enhance anything about instructional leadership or any practices, it is following the norms or the standard, or the policies being implemented by the CHED, even the practices that are mostly being used by the college for years and decades.” It asserts that structured governance frameworks in public institutions enhance institutional sustainability and quality assurance (Javed and Alenezi, 2023). Private institutions adopt entrepreneurial leadership, fostering adaptability and market-driven decisions, while LUCs align leadership with regional needs, emphasizing local partnerships. This finding highlights that private HEIs tend to be more flexible and market-responsive, whereas public institutions operate within strict regulatory frameworks (Bolton, 2019).

Meanwhile, Faculty qualifications also differ, with SUCs prioritizing compliance with national standards by ensuring that faculties hold advanced degrees and engage in continuous training. Private institutions, as noted by a faculty member, “have been very supportive of sending faculty members to enhance their skills through training… I have participated in national trainings,” focus on industry-aligned hiring and professional development, whereas LUCs prioritize practical training but often face resource constraints. This emphasizes the role of faculty qualifications and continuous development in maintaining instructional quality (Harvey, 2024).

Additionally, student-centric pedagogies further highlight institutional differences, as SUCs implement outcomes-based education (OBE) with competency-based learning, private institutions leverage technology-enhanced learning like blended learning, and LUCs integrate practical, localized applications to strengthen real-world skills, with one student noting the importance of “active learning where the students are engaged… using critical thinking skills in solving problems and applying what we learned.” These findings resonate with the advocacy of OBE and constructivist teaching methods for fostering deep learning (Loughlin et al., 2021). Holistic learning experiences also vary, with SUCs integrating co-curricular leadership programs, private institutions emphasizing wellness and career services, and LUCs focusing on community immersion. As one SUC student remarked, “Apparently, we don't just stay inside the university… we have extension programs and services.” This supports Jia's (2025) claim that holistic student development programs enhance retention and graduate employability.

Similarly, infrastructure investments reflect financial capacities, with SUCs benefiting from government support for state-of-the-art facilities, private institutions prioritizing modern resources to attract students, and LUCs relying on local partnerships, though students stress the need for “updated and accessible” learning materials which underscores the role of adequate educational infrastructure in improving student performance (Arjanto and Telussa, 2024).

Moreover, research, extension, and internationalization efforts show SUCs engaging in national and international collaborations, private HEIs focusing on applied research and global partnerships, and LUCs centering on community-based research, with a faculty member emphasizing that “community engagement and partnerships are vital for sustainability.” These observations are consistent with (Alsharari 2019), who argues that internationalization strategies vary among HEIs based on institutional priorities and resource availability. Institutional services further illustrate differences, as SUCs provide extensive government-funded scholarships and health services, private HEIs offer career mentorship and alumni networks, and LUCs leverage local initiatives despite limited resources, with a private HEI student recognizing continued institutional support: “…even until you take exams or board exams, they will help you so that you can achieve your goals.” This supports the work of (Johnson et al. 2022), who emphasized that strong student support services contribute to academic success and retention. These best practices highlight how SUCs, private HEIs, and LUCs play a critical role in ensuring quality education through various but effective strategies tailored to their institutional contexts.

Analysis of the identified best practices were quality-assured

Across SUCs, LUCs, and Private Institutions reveal several quality-assured practices essential for advancing educational excellence and sustainability. Governance mechanisms in these institutions emphasize strategic leadership and stakeholder collaboration, with SUCs aligning their frameworks with the CHED regulations to ensure compliance and continuous improvement. As one SUC faculty member noted, “To maintain, sustain, and enhance anything regarding instructional leadership or any practices, it is following the norms or the standard, or the policies being implemented by CHED.” This aligns with studies on accountability, compliance, and faculty development (Aithal and Maiya, 2024). Private institutions, with a focus on entrepreneurial leadership, adapt rapidly to market dynamics, as highlighted by a Private Institution administrator: “Budget is not really a hindrance to implementing projects or programs... it's about how you perceive things and how you can turn challenges into opportunities.” This reflects the views of (Gu et al. 2018), who focus on market-relevant skills and specialization. LUCs, on the other hand, leverage local government partnerships for localized development goals, as emphasized by an LUC administrator: “We try to improve our instruction and our policies and guidelines to make students' lives easier,” aligning with community-based leadership (Arar and Oplatka, 2022) and contextualized professional development (Langset et al., 2018).

In terms of faculty development, SUCs focus on maintaining faculty credentials and encouraging research-driven instruction in alignment with national standards. A faculty member in an SUC stated, “There is supporting the integration of technology and improving the facilities at the school,” underlining the institution's commitment to enhancing faculty competence and teaching quality. Private institutions emphasize specialization and market-relevant skills, as reflected by an administrator from a Private Institution: “We should be creative and resourceful... it's a matter of how you can turn challenges into opportunities.” LUCs focus on tailoring professional development to local needs, engaging faculty in lifelong learning, with one LUC faculty member commenting, “We actively engage in lifelong learning through research initiatives, ensuring a holistic and dynamic educational experience.”

Simultaneously, curriculum development reflects institutional missions and societal needs, with SUCs implementing outcome-based frameworks that align with national standards. Private institutions adopt innovative and interdisciplinary approaches, whereas LUCs focus on labor market relevance. One LUC administrator shared, “We try to improve our instruction and our policies... to make students' lives easier,” highlighting a student-centered approach to curriculum. These practices are reviewed regularly to align with current trends and ensure that they address future workforce needs. Infrastructure improvements, which are crucial for supporting teaching and learning, vary depending on the institutional resources.

Conversely, SUCs benefit from government funding, allowing for advanced facilities such as research labs, whereas Private Institutions strategically invest in modern infrastructure to enhance competitiveness. An administrator from a Private Institution emphasized the importance of budget management for quality assurance: “When it comes to accreditation activities, that is the top priority of the administration.” LUCs, although more resource-constrained, optimize local government support and innovative solutions to enhance infrastructure.

Furthermore, research and extension services are also key, with SUCs advancing their national development goals and engaging in community-focused extension programs. A participant from LUC reflected on this, stating, “Let's support what is the mission and vision of the institution by providing materials that can support not only academic needs but also research needs.” Quality assurance mechanisms are ingrained across all institutions, with accreditation processes, benchmarking, and performance evaluations forming the basis for continuous improvement. An LUC administrator emphasized the importance of quality assurance, saying, “Quality assurance... is one of the foundations to secure the level program accreditation set by the ALCUCOA.” QA, including accreditation and benchmarking, underpins continuous improvements in all institutions (Tasopoulou and Tsiotras, 2017).

Process of sustainability in quality-assured practices in instructional leadership

This involves continuous effort in strategic planning, faculty development, curriculum responsiveness, and stakeholder engagement. Across SUCs, LUCs, and private institutions, these institutions emphasize alignment with regulatory frameworks, national goals, and local needs to ensure long-term success. Effective leadership is crucial for sustaining education quality. In this context, SUCs focus on aligning with national development goals through centralized governance and CHED regulations (Chao, 2022). Private institutions take advantage of flexible policies for continuous improvement, whereas LUCs prioritize meeting the needs of local government units and communities (Gera, 2016). Strategic leadership includes proactive policymaking and data-driven decision making (Hwang et al., 2021). As one private faculty member mentioned, “Despite being a small college, education always prides itself on the quality of its faculty.”

Faculty development plays a vital role in ensuring a high instructional quality. SUCs invest in advanced degrees and professional growth, aligning with national standards, whereas private institutions focus on faculty specialization to meet market demands (Matkin, 2022). LUCs face challenges due to limited resources, but still strive to create robust development programs, which include funding, participation in seminars, and involvement in research. An LUC faculty member highlighted that “the successful implementation of faculty development programs... requires careful planning, alignment with institutional goals, and adequate resources.” These faculty-development initiatives ensure that institutions remain competitive in their efforts to provide high-quality education.

Curriculum development is another key component of sustaining instructional leadership. All institutions continuously revise their curricula based on national educational goals, labor market demands, and community needs (Ortiga, 2017). SUCs integrate research into their curricula to align with national standards, while private institutions innovate to attract competitive enrollment. LUCs focus on creating community-responsive programs that meet local needs (Johnson, 2014). Stakeholder feedback, labor market trends, and accreditation agencies ensure that curricula meet established quality standards. As a private administrator noted, “Learning outcomes must be measured based on their achievement in the test... and the licensure is a testament to that.” This iterative process ensures alignment of the curriculum with the desired educational outcomes.

Furthermore, institutions emphasize holistic educational enhancement and student success through student-centered pedagogies. SUCs use diverse learning strategies, private institutions focus on personalized learning, and LUCs incorporate practical approaches that are tied to local contexts. Monitoring student success through engagement, graduation rates, and employment outcomes leads to continuous improvement (Price and Tovar, 2014). The SUC faculty reflected, “During the pandemic, innovative research and learning strategies were developed to cope with the needs arising from the pandemic.” This adaptability ensures that institutions continue to support students in achieving their academic and career goals even during challenging times.

Simultaneously, research engagement and institutional linkages also play important roles in sustaining quality education. SUCs and LUCs are active in government-mandated research, whereas private institutions engage in industry partnerships that help strengthen their research capabilities. Local, national, and international collaborations have further enhanced these efforts. An LUC administrator pointed out, “We need to collaborate with other institutions... to increase resources and services.” These partnerships provide not only opportunities for academic collaboration but also support capacity building and international exchange, ensuring that institutions remain at the forefront of research and innovation (Ul Hassan et al., 2025).

Ultimately, quality assurance mechanisms, including governance and continuous improvement, are critical for sustaining educational standards. In SUCs, governance is closely tied to regulatory compliance, whereas private institutions maintain flexible yet rigorous quality systems. LUCs continue to strive to improve their local resource constraints. The integration of quality assurance frameworks, supported by evidence-based decision-making, ensures high standards and guides continuous progress (Durmuş Senyapar and Bayindir, 2024). A private administrator shared, “The approach to instructional leadership is highly consultative... it's a process of considering policies, standards, and guidelines, and tailoring them to fit the institutional context.” These frameworks ensure that instructional practices are aligned with institutional goals and national education standards.

Performance tracking, resource optimization, and stakeholder collaboration are critical for the refinement of institutional strategies. Institutions utilize data on student performance, faculty productivity, and research outputs to inform strategic decisions (Agasisti and Bowers, 2017). An LUC faculty member emphasized, “The training is great... and they have been taught the right content... this is the result which I think is quality education.” Continuous assessment through benchmarking, tracer studies, and performance evaluations enables institutions to adapt and enhance their instructional practices over time, thus reinforcing their commitment to quality education.

The development of harmonized quality assured instructional leadership framework for higher education institutions- teacher education institutions

This framework synthesizes best practices from six high-performing HEIs, offering an adaptable evidence-based approach to instructional leadership. Recognizing diversity in governance, resources, and institutional cultures, it moves beyond a one-size-fits-all model by identifying strategies that enhance student success, ensure quality assurance, and promote sustainable education. Rooted in insights from institutional documents and interviews, the framework aligns leadership adaptability with institutional needs and goals, fostering collaboration across different HEI categories, while maintaining institutional uniqueness.

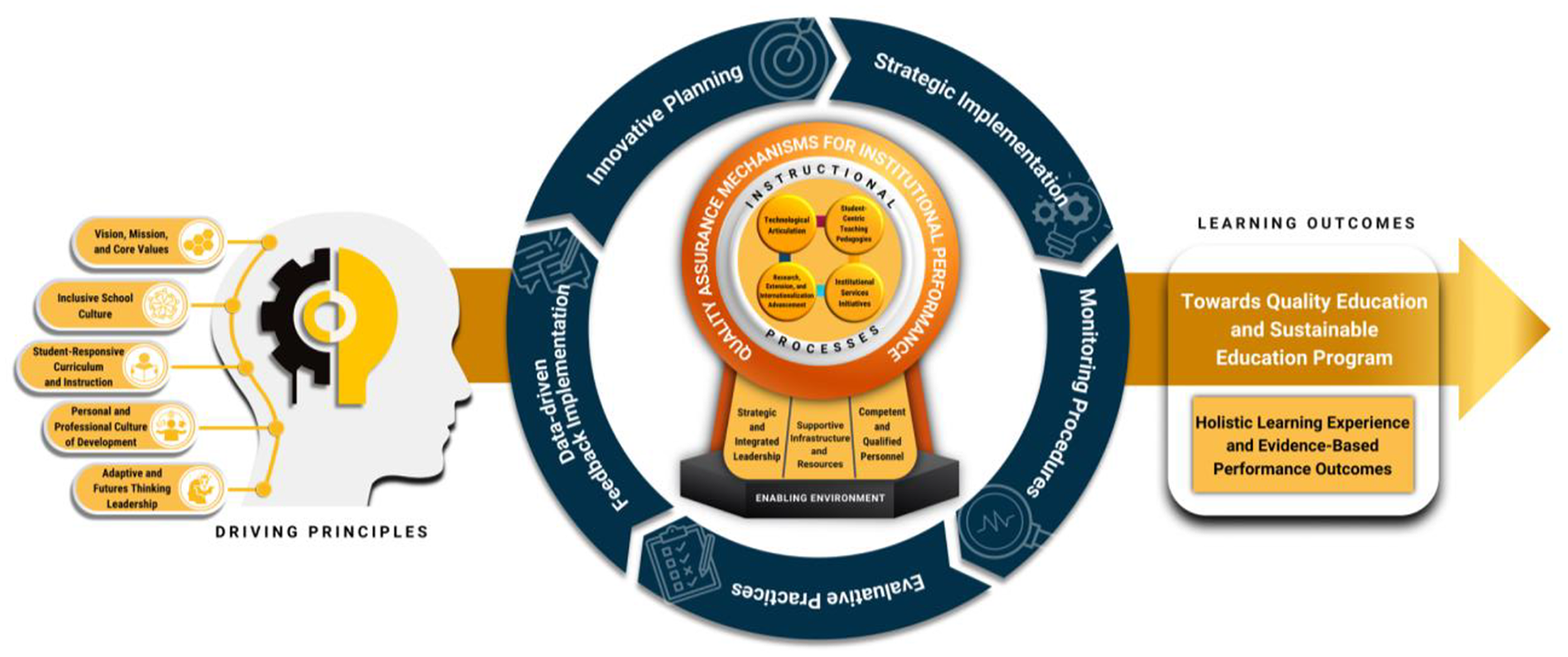

In Figure 5, it provides a structured, systematic, and evidence-based pathway for improving teaching and learning that aligns with national and international accreditation standards. It equips instructional leaders with high-impact strategies, clear and measurable goals, and mechanisms for continuous refinement, based on stakeholder feedback and performance data. Recognizing that excellence is an evolving process, it emphasizes regular review and adaptation to meet the emerging educational challenges. In addition, the framework ensures consistency in evaluating and enhancing instructional leadership by integrating foundational principles that support the development, implementation, and sustainability of best practices. Through a systematic and inclusive approach, it actively involves stakeholders; strengthens leadership competencies; and establishes goals aligned with the institution's vision, mission, goals, and objectives (VMGO), ultimately fostering a high-quality education system that produces well-prepared and globally competitive graduates.

Figure 5

Harmonized quality-assured instructional leadership framework for higher education institutions with a focus on teacher education.

Figure 5 is also structured into multiple phases consisting of six (6) phases (i.e., driving principles, enabling environment, instructional processes, arching pillar of instructional processes, process of sustenance, and continuous improvement, and learning outcomes) and a total of twenty (20) components that are considered integral parts in building a quality-assured instructional leadership framework within the HEI. It integrates both a democratic education lens and a transformational leadership lens, promoting inclusiveness, participatory decision-making, and inspiring stakeholders to work collaboratively toward shared educational goals. Quality is defined as meeting evolving standards while addressing institutional and student needs.

(1) The framework is anchored in guiding principles essential to effective instructional leadership: a clear vision, mission, and core values that align leadership efforts; adaptive and futures-thinking leadership that enables institutions to navigate emerging challenges; an inclusive school culture that fosters equity and engagement; a student-responsive curriculum and instruction that adapts to diverse learning needs; and personal and professional culture of development to ensure instructional leaders remain equipped with the necessary expertise.

(2) An enabling environment is critical for the success of instructional leadership, which consists of three key elements: strategic and integrated leadership, which aligns institutional practices with long-term goals; competent and qualified personnel, emphasizing faculty recruitment, training, and retention; and supportive infrastructure and resources, including technology, laboratories, and libraries, that enhance student engagement.

(3) The framework highlights instructional processes that facilitate effective teaching and learning, including technological integration to enhance accessibility, student-centered pedagogies that promote interactive learning, and institutional service initiatives that support holistic student development. Additionally, research, extension services, and internationalization initiatives strengthen global competencies and graduate employability, aligning educational outcomes with industrial demands.

(4) Quality assurance mechanisms for institutional performance is arching pillar of instructional processes to have systematic and analytical methods and measures for institutional structures, policies, and practices promoting good services and operations that fulfill predetermined performance and quality standards.

(5) Sustenance and continuous improvement of the framework require innovative planning, strategic implementation, monitoring procedures, evaluative practices, and data-driven feedback implementation to ensure responsiveness to evolving educational needs.

(6) Its learning outcomes cover quality education, sustainable education programs, holistic learning experiences, and evidence-based performance outcomes, measured by national and international recognition, licensure exam performance, and graduate employability.

Implication to policy and practice

The three HEI categories showcase best practices within their unique contexts; however, sustaining, improving, and fostering innovation through cross-institutional collaboration is vital. Key recommendations include harmonizing accreditation standards (AACCUP, PAASCU, and ALCUCOA) and incorporating sustainability metrics for consistent evaluation. Inclusive criteria for COE and COD designations should ensure equal opportunities for LUCs along with financial and technical support for infrastructure, faculty development, and research initiatives.

The CHED may implement national faculty qualification standards and provide scholarships for graduate and doctoral studies, particularly benefiting LUCs. Baseline standards for libraries, laboratories, and ICT facilities should be established, with resource sharing being encouraged in underserved areas. Consortia among SUCs, LUCs, and private institutions can enhance collaboration, share best practices, and collectively address challenges.

Additional funding for LUCs should focus on infrastructure, faculty development, and research with partnerships fostered by LGUs and industries. Leadership competencies across HEIs can be harmonized by blending SUC governance, LUC community focus, and private institutions' entrepreneurial mindsets. Promoting global collaboration and knowledge sharing are essential for exchanging best practices, research, and innovative teaching methods.

A centralized national monitoring system should track institutional performance, accreditation, and CHED policy implementation. Finally, fostering collaboration within HEIs, improving processes, and adopting inclusive curricula will address diverse stakeholder needs and ensure continuous improvement to meet the evolving educational demands.

Limitation of the study

This study focused on three categories of Teacher Education Institutions (TEIs)—two SUCs, two private institutions, and two LUCs—within Luzon (NCR, Regions IV-A, III, and II). While these six institutions met exemplary performance criteria, the limited sample size and geographic scope mean the findings may not represent all HEI typologies nationwide. In particular, the framework may not fully capture the realities of TEIs in the Visayas and Mindanao regions, nor those outside the TEI sector. Differences in governance, institutional culture, resources, and funding further demonstrate that “best practices” identified in one category or region may not be directly transferable to others. Moreover, data collection relied solely on institutional documents and participant interviews; thus, accuracy and depth depended on the availability of records and the willingness of participants to share information. Potential gaps or biases may have influenced the comprehensiveness of the analysis. Given these limitations, caution must be exercised against overgeneralizing the results. Future research should refine the framework by testing it in more diverse institutional and regional contexts, including Visayas, Mindanao, and non-TEI sectors, while also assessing long-term outcomes to strengthen its nationwide relevance and effectiveness.

Conclusion

This study highlights the value of identifying best practices and addressing challenges across different categories of HEIs to inform targeted policies and initiatives. Through the experiences of six high-performing TEIs, a harmonized, quality-assured instructional leadership framework was developed, grounded in principles that enhance teaching quality, institutional performance, inclusivity, and continuous improvement. Structured into six (6) phases and twenty (20) interconnected components, the framework offers a structured, systematic, and evidence-based approach adaptable to diverse HEI contexts. It underscores the importance of equity, stakeholder engagement, and alignment with quality assurance standards. While acknowledging contextual differences among HEIs, the framework provides practical guidance for instructional leaders, policymakers, and practitioners aiming to strengthen leadership practices and sustain quality education in a dynamic environment.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Philippine Normal University-Research Ethics Committee-REC Code: 07212023-225-FR. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JA: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Commission on Higher Education through the Scholarships for Instructors' Knowledge Advancement Program (CHED-SIKAP).

Acknowledgments

A special and heartfelt thanks to my research adviser, Dr. Maria Glenda O. De Lara, and the panelists whose invaluable guidance, insightful wisdom, and constructive feedback have been instrumental in shaping this paper. Their commitment to my academic growth and belief in my potential have inspired me to strive for quality and excellence. I am truly grateful for their mentorship and support. Likewise, I wish to extend my profound and heartfelt gratitude to all the participating TEIs and to every participant who willingly and graciously embraced the opportunity to be part of my study. Your time, openness, and generosity have truly breathed life into this research.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1663289/full#supplementary-material

References

1

AbdallahA. K.MusahM. B. (2021). Effects of teacher licensing on educators' professionalism: UAE case in local perception. Heliyon7:e08348. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08348

2

AgasistiT.BowersA. J. (2017). “Data analytics and decision making in education: towards the educational data scientist as a key actor in schools and higher education institutions,” in Handbook of Contemporary Education Economics, eds. JohnesG.JohnesJ.AgasistiT.López-TorresL. (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing), 184–210. 10.4337/9781785369070.00014

3

AithalP. S.MaiyaA. K. (2024). Development of a new conceptual model for improvement of the quality services of higher education institutions in academic, administrative, and research areas. SSRN Electronic J. 8, 260–308. 10.2139/ssrn.4770790

4

AlsharariN. M. (2019). Internationalization market and higher education field: institutional perspectives. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 34, 315–334. 10.1108/IJEM-12-2018-0402

5

AndriamisezaR.SilvestreF.ParmentierJ.-F.BroisinJ. (2023). How learning analytics can help orchestration of formative assessment? Data-driven recommendations for technology- enhanced learning. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol.16, 804–819.10.1109/TLT.2023.3265528

6

ArarK.OplatkaI. (2022). “Community Based Leadership,” in Advanced Theories of Educational Leadership, eds. ArarK.OplatkaI. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 14, 49–62. 10.1007/978-3-031-14510

7

ArjantoP.TelussaR. P. (2024). Educational management strategies: linking infrastructure, student activities, and academic performance. JPPI10:163. 10.29210/020244097

8

BastenD.HaamannT. (2018). Approaches for organizational learning: a literature review. SAGE Open8:215824401879422. 10.1177/2158244018794224

9

BoltonD. (2019). Marketised higher education: implications for corporate social responsibility and social licence to operate. J. Sustain. Res. 1:e190014. 10.20900/jsr20190014

10

CampbellS.GreenwoodM.PriorS.ShearerT.WalkemK.YoungS.et al. (2020). Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 25, 652–661. 10.1177/1744987120927206

11

CaoY.LiX. (2014). Quality and quality assurance in Chinese private higher education: a multi-dimensional analysis and a proposed framework. Qual. Assur. Educ. 22, 65–87. 10.1108/QAE-09-2011-0061

12

ChaoR. Y. (2022). “Higher education in the Philippines,” in International Handbook on Education in South East Asia, eds. SymacoL. P.HaydenM. (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pvt. Ltd.), 1–28. 10.1007/978-981-16-8136-3_7-2

13

DíezF.VillaA.LópezA. L.IraurgiI. (2020). Impact of quality management systems in the performance of educational centers: educational policies and management processes. Heliyon6:e03824. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03824

14

Durmuş SenyaparH. N.BayindirR. (2024). Quality assurance in higher education in the 21st century: strategies and practices for new generation universities. High. Educ. Govern. Policy5, 115–133. 10.55993/hegp.1573331

15

FlavianH. (2020). “From Pedagogy to Quality Assurance in Education: An International Perspective,” in From Pedagogy to Quality Assurance in Education: An International Perspective, ed. FlavianH. (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 3–9. 10.1108/978-1-83867-106-820201002

16

GeraW. (2016). Public participation in environmental governance in the Philippines: the challenge of consolidation in engaging the state. Land Use Policy52, 501–510. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.02.021

17

GuJ.LiX.WangL. (2018). “Specialized Higher Education,” in Higher Education in China, eds. GuJ.LiX.WangL. (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pvt. Ltd.), 91–11510.1007/978-981-13-0845-1_5

18

HarveyL. (2024). What have we learned from 30 years of quality in higher education: academics' views of quality assurance. Qual. High. Educ. 30, 360–375. 10.1080/13538322.2024.2385793

19

HwangS.NamT.HaH. (2021). From evidence-based policy making to data-driven administration: proposing the data vs. value framework. Int. Rev. Public Admin. 26, 291–307. 10.1080/12294659.2021.1974176

20

JavedY.AleneziM. (2023). A case study on sustainable quality assurance in higher education. Sustainability15:8136. 10.3390/su15108136

21

JiaR. (2025). Practical application and industry relevance: the role of off-campus training in student skill development. Educ. Infor. Technol. 30, 15719–15755. 10.1007/s10639-025-13408-9

22

JohnsonC.GitayR.Abdel-SalamA.-S. G.BenSaidA.IsmailR.Naji Al-TameemiR. A.et al. (2022). Student support in higher education: campus service utilization, impact, and challenges. Heliyon8:e12559. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12559

23

JohnsonL. (2014). Culturally responsive leadership for community empowerment. Multicult. Educ. Rev. 6, 145–170. 10.1080/2005615X.2014.11102915

24

KrooiM.WhittinghamJ.BeausaertS. (2024). Introducing the 3P conceptual model of internal quality assurance in higher education: a systematic literature review. Stud. Educ. Eval. 82:101360. 10.1016/j.stueduc.2024.101360

25

LangsetI. D.JacobsenD. Y.HaugsbakkenH. (2018). Digital professional development: towards acollaborative learning approach for taking higher education intothe digitalized age. Nordic J. Digital Literacy13, 24–39. 10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2018-01-03

26

LiuS. (2019). External Higher Education Quality Assurance in China, 1st Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. 10.4324/9781315122403-1

27

LoughlinC.Lygo-BakerS.Lindberg-SandÅ. (2021). Reclaiming constructive alignment. Eur. J. High. Educ. 11, 119–136. 10.1080/21568235.2020.1816197

28

MakhoulS. A. (2019). Higher education accreditation, quality assurance and their impact to teaching and learning enhancement. J. Economic Admin. Sci. 35, 235–250. 10.1108/JEAS-08-2018-0092

29

MatkinG. W. (2022). Reshaping university continuing education: leadership imperatives for thriving in a changing and competitive market. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 36, 3–18. 10.1080/08923647.2021.1996217

30

MunnaA. S. (2023). Instructional leadership and role of module leaders. International J. Educ. Reform32, 1–17. 10.1177/10567879211042321

31

OrtigaY. Y. (2017). The flexible university: higher education and the global production of migrant labor. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 38, 485–499. 10.1080/01425692.2015.1113857

32

PaniaguaF. G. (2019). “Quality Assurance in Online Education: A Development Process to Design High-Quality Courses,” in Social Computing and Social Media. Communication and Social Communities, ed. MeiselwitzG. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 11579, 182–194. 10.1007/978-3-030-21905-5_14

33

PriceD. V.TovarE. (2014). Student engagement and institutional graduation rates: identifying high-impact educational practices for community colleges. Commun. Coll. J. Res. Pract. 38, 766–782. 10.1080/10668926.2012.719481

34

QureshiH. A.ÜnlüZ. (2020). Beyond the paradigm conflicts: a four-step coding instrument for grounded theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods19:160940692092818. 10.1177/1609406920928188

35

RidderH. G. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Res. 10, 281–305. 10.1007/s40685-017-0045-z

36

RobinsonO. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: a theoretical and practical guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 11, 25–41. 10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

37

ShakedH. (2023). Instructional leadership in school middle leaders. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 37, 1288–1302. 10.1108/IJEM-03-2023-0089

38

ShakedH.BenolielP. S. (2020). Instructional boundary management: the complementarity of instructional leadership and boundary management. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 48, 821–839. 10.1177/1741143219846905

39

TasopoulouK.TsiotrasG. (2017). Benchmarking towards excellence in higher education. Benchmarking24, 617–634. 10.1108/BIJ-03-2016-0036

40

TownsendT. (Ed.). (2019). Instructional Leadership and Leadership for Learning in Schools: Understanding Theories of Leading. Cham: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-23736-3

41

Ul HassanM.MurtazaA.RashidK. (2025). Redefining higher education institutions (heis) in the era of globalisation and global crises: a proposal for future sustainability. Eur. J. Educ. 60:e12822. 10.1111/ejed.12822

42

WynneC. W.SatchwellD. (2020). Revolution in the trenches: building capacity through quality assurance in Belize: a case study. Qual. High. Educ. 26, 174–191. 10.1080/13538322.2020.1759189

Summary

Keywords

instructional leadership, quality assurance, higher education institutions, quality education, teacher education institutions, quality-assured instructional leadership framework

Citation

Aquino JMDR (2025) Best practices of high performing higher education institutions in the Philippines towards the development of harmonized quality-assured instructional leadership framework. Front. Educ. 10:1663289. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1663289

Received

10 July 2025

Accepted

29 September 2025

Published

31 October 2025

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Yoon Fah Lay, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia

Reviewed by

John Mark R. Asio, Gordon College, Philippines

Rany Sam, National University of Battambang, Cambodia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Aquino.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: John Michael Del Rosario Aquino johnmichael.aquino@lspu.edu.ph

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.