- 1Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior in the Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, United States

- 2College of Social Work, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, United States

Introduction: Historically Black Colleges and Universities have played a key role in advancing educational equity and remain essential in shaping a more inclusive and diverse research landscape. However, persistent structural barriers limit their full participation in national research priorities. There remains limited comprehensive awareness of the unique barriers and opportunities encountered by investigators within HBCUs. This study explores the experiences of investigators at HBCUs, examining the challenges and opportunities they encounter in conducting research.

Method: A two-phased exploratory approach was utilized, including a qualitative content analysis of grant entries from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF) and an online survey of HBCU investigators between February 7th and April 10th, 2024.

Results: The content analysis highlights HBCU faculty’s strong contributions to research areas of science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM), advanced technology and data science, environmental sciences, and health. The survey findings reveal challenges related to funding, research infrastructure, and a lack of targeted support for enhancing faculty research capabilities. Participants also highlighted several challenges, including administrative burdens, under-resourced support for research and activities, lack of funding, and the need for policy changes. Results suggest the pressing need for HBCUs to address workload balance, improve mentorship, provide professional support for grant submission, and reduce administrative burdens to increase the research productivity of investigators.

Discussion: Findings reinforce a strategic role in advocating equitable research policies and institutional support structures at HBCUs. Effective central leadership and sustained institutional support are essential for HBCUs to address these challenges. These efforts are not merely a measure of faculty productivity; they also contribute to broader national goals by enhancing the future research environment and promoting inclusive excellence in higher education, particularly for underrepresented institutions.

1 Introduction

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) emerged in the United States after the Civil War, with a focus on advancing educational opportunities primarily for African Americans (Gasman et al., 2023; Matthews, 2008). There are 105 accredited HBCUs across 21 states, with the majority in the Southeastern region, and they continue to play a critical role in serving underrepresented populations, advancing equity in higher education, and conducting research (Bonner et al., 2024; Dahl et al., 2022; Njoku and Murray, 2024). HBCUs often prioritize graduating students and ensuring a holistic educational experience with a focus on research and promoting inclusivity (Gasman et al., 2017; Ghebreyessus et al., 2022). In recent years, there has been a significant shift in various research areas in HBCU institutions, mostly due to the substantial contributions made by academics and scientists affiliated with HBCUs (Gasman et al., 2017; Rana et al., 2025; Upton and Tanenbaum, 2014). It is essential to recognize the dual role HBCUs play not only as educational institutions but also as key contributors to equity, diversity, and innovation within higher education. Despite systemic challenges, HBCUs produce a disproportionate number of Black professionals in academia, realizing the importance of achieving national diversity goals in higher education and workforce development (Gasman and Thai-Huy, 2019; Moore et al., 2016; Sexton et al., 2025).

HBCUs contribute substantially to the STEM field, producing high numbers of Black professionals and enhancing research capacity for leadership and faculty development (Ghebreyessus et al., 2022; Alexander, 2021; Echegoyen et al., 2025; Toldson, 2017). Contrary to the misconception that HBCUs primarily focus on the humanities, over 80% of their research falls within STEM disciplines, with additional contributions in the social sciences and environmental health (Ghebreyessus et al., 2022; Pamela, 2010).

Despite these contributions, HBCU researchers face significant challenges due to limited funding, funding cancelations, and under-resourced research infrastructures (Moore et al., 2012; Sara, 2022; Waite et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2022; Yasmin, 2025). In 2019, HBCUs received 178 times less funding than non-HBCUs from the largest U. S. foundation and experienced a 30% decline in funding from 2002 to 2019 (Mann, 2021; Rebekah, 2024). A preliminary review of 2020 data showed a rebound to $249 million, reflecting heightened pandemic-era philanthropic attention, although major structural inequities remain (Philanthropy News D, 2023). In 2024–2025, major gifts such as a $100 million grant from the Lilly Endowment to the United Negro College Fund and contributions from donors highlight renewed interest, though the sustainability of this support remains uncertain (Philanthropy News D, 2023; Annie, 2024; Jasper, 2025). The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the largest in the U. S. with assets over $67 billion, has invested heavily in education and global health but has offered far less support to HBCUs compared to predominantly white institutions (ABFE, 2023). These disparities eventually impact faculty recruitment, research productivity, and institutional growth (Livingston et al., 2023).

Faculty at other Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs), including Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) and Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), face comparable barriers such as insufficient mentoring opportunities, limited internal funding resources, and a lack of dedicated time for research activities (Echegoyen et al., 2025; Ives et al., 2023). These obstacles are often more pronounced for early-career and underrepresented minority (URM) faculty, who must manage substantial teaching responsibilities, experience added expectations tied to their identities, and operate within institutional environments that may place less emphasis on research (Rana et al., 2025; Echegoyen et al., 2025; Hoppe et al., 2019). In addition, research has shown that systemic inequities in federal grant review processes disproportionately disadvantage Black and Brown scholars, thereby reducing their chances of securing competitive research funding (Burton, 2023; Epps and Guidry, 2009; Escobar et al., 2021).

More recently, we observe a rising funding experience of HBCUs, showing a positive trend of heightened funding for these historically underfunded institutions (Bonner et al., 2024; Dahl et al., 2022). Federal allocations surpassed $6.5 billion, and endowments grew by 33% in 2021 (Njoku and Murray, 2024; Mann, 2021). Agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Science Foundation (NSF) have developed targeted programs to strengthen proposal development and support research collaborations at HBCUs (Toldson, 2017; NIST, 2018). HBCUs have also formed collaborative research partnerships with industry, government, and research-intensive institutions to access funds, resources, and expertise (Njoku and Murray, 2024; Echegoyen et al., 2025).

While earlier studies have examined funding and institutional barriers, few have centered their focus on HBCU investigators (Livingston et al., 2023; UIDP, 2023). Scholars have called for a multi-pronged approach to support HBCU research, including reducing faculty workload, enhancing administrative structures, improving access to mentoring, and revising grant application procedures to reduce barriers. Yet, the literature also emphasizes that institutional transformation efforts must align with the experiences of faculty at URM, understanding their specific needs, motivations, and institutional contexts (Escobar et al., 2021; Wilson and Guerra, 2021). Without that nuance, policy efforts may fail to address the real sources of inequity. There is still no comprehensive awareness of the unique barriers and opportunities encountered by researchers within HBCUs. Financial limitations and other considerable hurdles adversely impact the quality of research at HBCUs (Waite et al., 2023; Harrington et al., 2015). This study explores those experiences, highlighting both obstacles and opportunities to enhance research productivity and aims to inform policies and funding entities that could be shaped to the specific needs of HBCUs. It takes an exploratory approach, offering insight into how institutional structures and support systems can shape faculty research engagement and outcomes. Specifically, this study seeks to answer: What are the key barriers and enabling factors affecting research engagement among HBCU investigators?

2 Materials and methods

This study employed an exploratory two-phased approach where the first phase is a content analysis of federal (NIH and NSF) funding awarded to HBCUs, and the second phase is an online survey administered to HBCU faculty members.

2.1 First phase: content analysis

To explore funding patterns, we followed a qualitative content analysis approach (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Krippendorff, 2004) to allow categories to emerge directly from the raw data without imposing preconceived classifications. We analyzed the contents of the NIH and NSF websites to review grants awarded to HBCU investigators. This phase aims to identify broad themes in grant allocation and research focus among HBCUs. Our analysis included all active projects located during the search period from mid-August to mid-September 2023. We limited our search to this time to capture a consistent and reliable snapshot of federal funding, as NIH and NSF databases are continuously updated. This defined window also aligned with the start of our study period, allowing us to integrate the analysis with the subsequent survey phase in a systematic manner.

We used a map of HBCUs across the US1 to compile a complete list of all HBCUs. Focusing on HBCUs across states, our process began with a search for grants awarded to HBCUs on the NIH RePORTER website.2 Subsequently, we gathered data from the NSF website3 searching for awarded grants according to the listed HBCUs. This search allowed us to extract funding information. All grant details were systematically organized into separate Excel sheets for both entities, categorized by each state. We recorded specific grant details, including project title, principal investigator’s email address, state name, grant duration, and research focus. During the analysis procedure based on established qualitative research practices, a coding framework was developed deductively, drawing from research funding patterns and inductively refined during data extraction. Grant titles, abstracts, and keywords were reviewed to identify recurring themes and categorized by topical areas (e.g., biomedical sciences, engineering, education, community health). The analysis emphasized the frequency and thematic distribution of research topics and funding concentrations across states. Inter-coder agreement was checked for a subset of the data to ensure reliability.

2.2 Second phase: survey among HBCU investigators

2.2.1 Participants

The survey targeted Principal Investigators (PIs) directly affiliated with HBCUs who had received grants either from the NIH or NSF. We obtained the email addresses of PIs from grant databases. We extracted all PI contacts combinedly from the NSF website, while it was necessary to visit each grant’s webpage for NIH. Altogether, 306 email addresses were successfully obtained, with 139 from NIH and 167 from NSF websites.

2.2.2 Instruments

The development of the survey tool was guided by a review of relevant literature utilizing published research as a basis for creating the survey questionnaire (Matthews, 2008; Toldson, 2017; Moore et al., 2012). The tool underwent multiple revisions and was reviewed by the research team before finalization. The survey encompassed 40 questions categorized into 10 sections, featuring 2–4 questions per category. Eight questions were open-ended, with the remaining being close-ended and employing various question forms. Subsequently, we conducted a pilot test of the survey tool with the internal research team to identify any further revisions required. Following the completion of necessary revisions the survey tool was finalized.

2.2.3 Data collection procedure

The survey tool was formatted into an online survey platform named “Qualtrics XM” for which we created a survey link (Qualtrics, 2025). We sent the survey link to all 306 selected PI’s email addresses obtained from the grantee websites. Of the 306 emails, 18 (7 from NIH PIs’ and 11 from NSF) bounced back during the distribution of the survey link. Thus, we followed up with 288 PI emails. Data collection took place between February 7th and April 10th, 2024. Even after sending out weekly reminders to encourage participation, we had a low response rate (7%), leading us to extend the deadline and to engage in a personalized email outreach strategy, acknowledging the busy schedules and workloads of the PIs. The final survey is based on 43 completed responses, resulting in a 15% response rate.

2.2.4 Analysis approach

For the phase 1 study, we conducted a qualitative content analysis of funded grants and categorized them by topic area based on the titles, abstracts, and keywords on the websites. This approach, rooted in qualitative content analysis methodology, allowed for both manifest and latent content interpretation (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005). Through this, we obtained a detailed description of the distribution and focus of grants across states and research areas. This phase aimed to explore the funding trends across states and research priorities. For the second phase PI survey data were collected through Qualtrics and downloaded into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (IBM Corp, 2014). Respondents used a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the degree to which they described the balance of conducting research compared to teaching, student advisement, and service commitments. Finally, we used descriptive statistics, performing frequency and percentages.

We imported the qualitative responses from the survey into NVivo version 14, a qualitative data analysis software (Lumivero, 2023). Given that the data were extracted from a self-administered survey and the responses were focused and concise, initial coding was straightforward, leading to the identification of concepts and patterns. Responses were analyzed thematically within each domain. During analysis, we extracted direct quotations to illustrate the views and experiences of the faculty members.

3 Results

3.1 Phase 1: content analysis

3.1.1 Distribution of grant-receiving HBCUs across the states

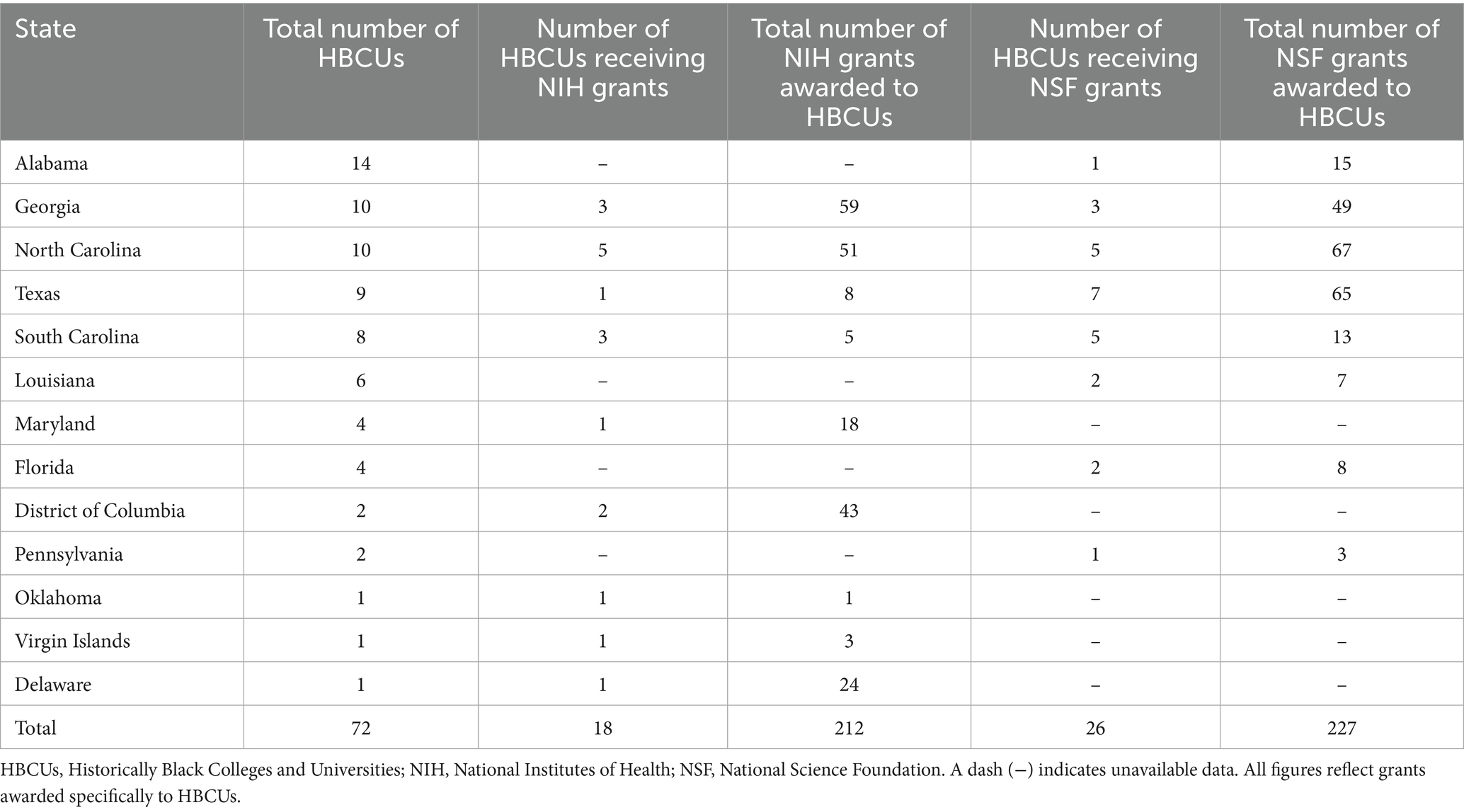

Of the 105 HBCUs, 72 institutions received grants from either the NIH or NSF during the study period. In total, 18 HBCUs received 212 NIH awards across 9 states, while 26 HBCUs received 227 NSF awards across 8 states. North Carolina and Georgia were the leading recipients of NIH funding, receiving 51 and 59 grants, respectively. The District of Columbia and Delaware followed with 43 and 24 NIH grants, respectively. For NSF funding, North Carolina and Texas led with 67 and 65 grants, followed by Georgia (Allen and Jewell, 2002) and Alabama (Toldson, 2017). States such as Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, and the Virgin Islands received fewer grants overall (Table 1). The results show that although NIH and NSF funding reached many HBCUs, most of the awards were concentrated in just a few states.

3.1.2 Description of NIH grants funded at HBCUs

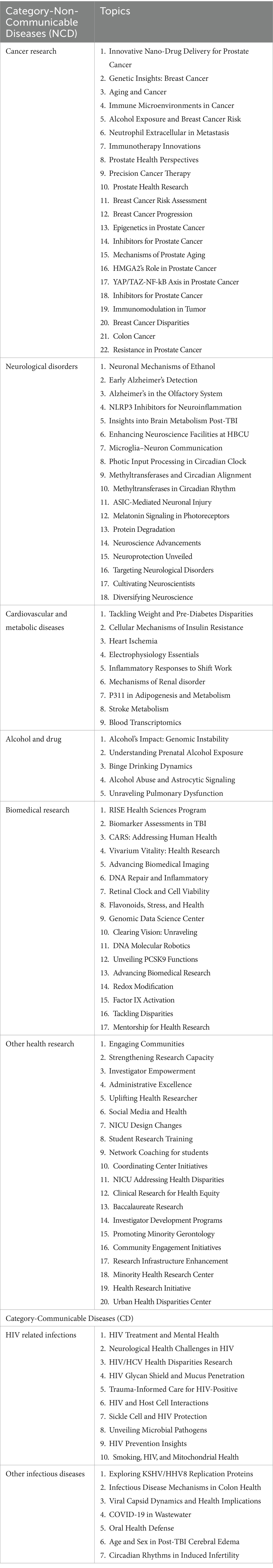

NIH grants were categorized into non-communicable diseases (NCDs), communicable diseases (CDs), and other health-related topics (Table 2). Among the NCD-related projects, there were 18 distinct cancer-focused grants, 16 focused on neurological disorders, and 9 related to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Alcohol and drug-related topics appeared in 4 grants, while 14 grants supported biomedical and translational research initiatives. Approximately 12 grants focused on communicable diseases, primarily HIV and other infections. An additional 30 grants covered other topics such as community engagement, research infrastructure, student mentoring, health disparities, and public health innovation.

3.1.3 Description of NSF grants funded at HBCUs

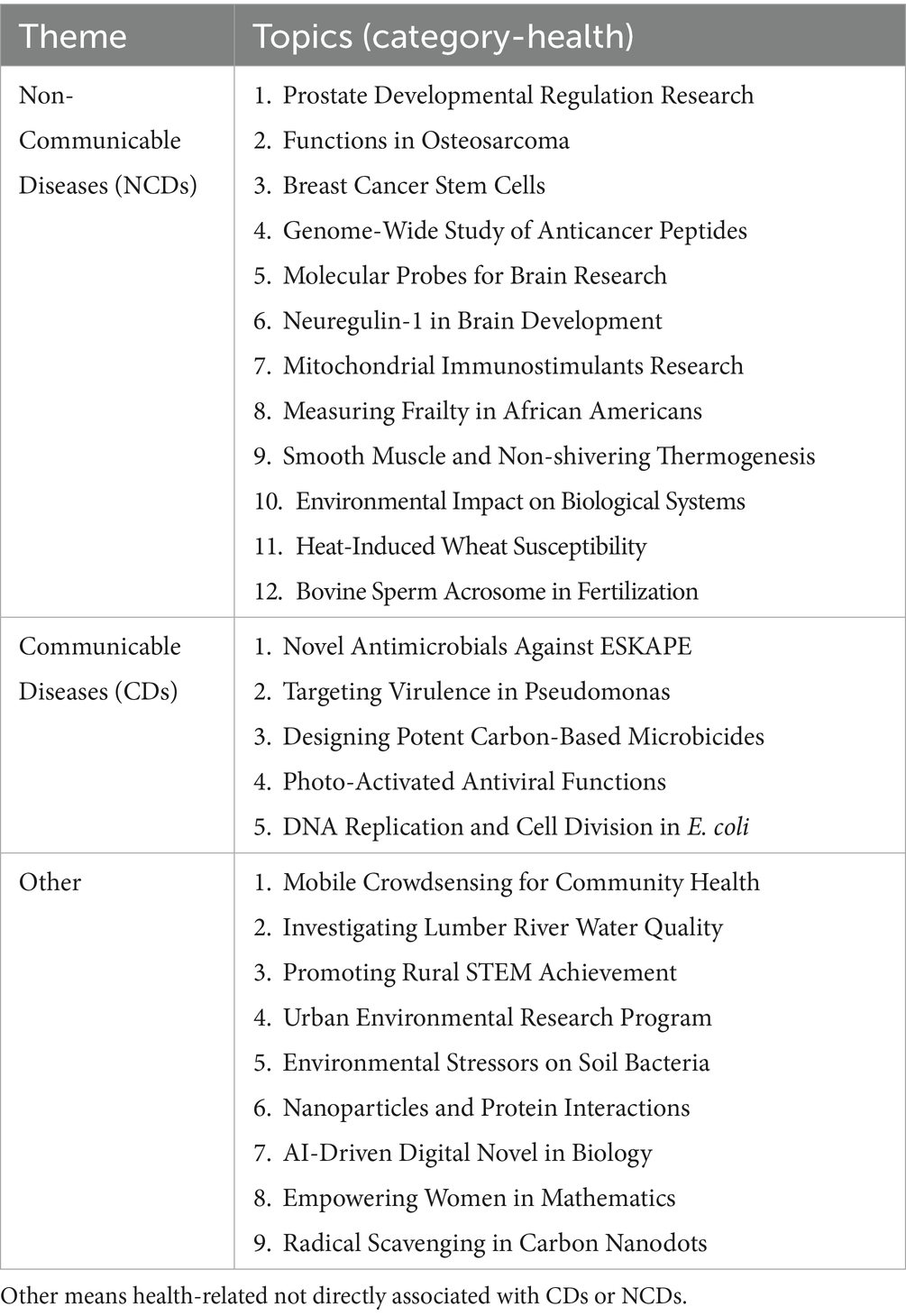

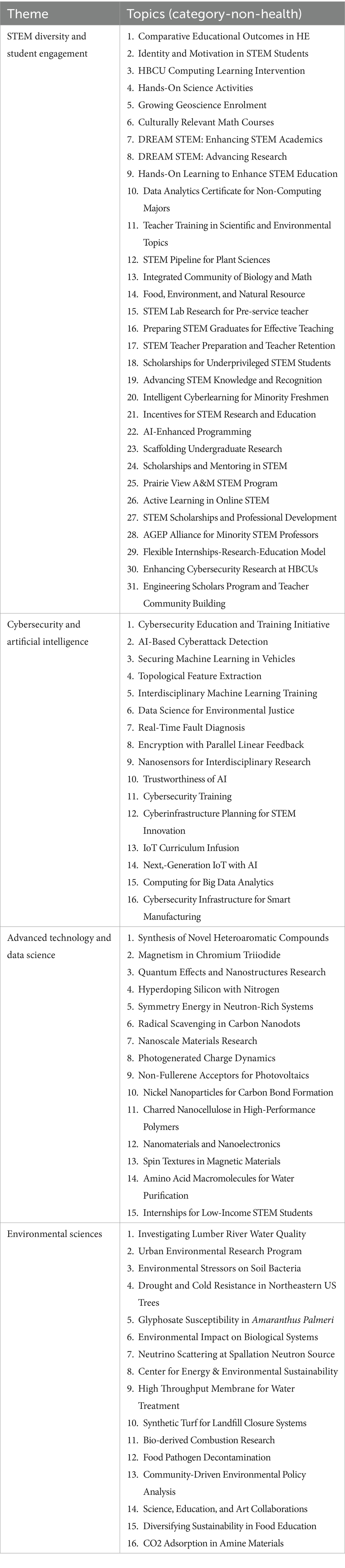

Of the 227 NSF grants awarded to HBCUs, 27 grants (approximately 12%) were classified as health-related: cancer biology, neurodevelopment, antimicrobial resistance, and environmental health (Table 3). The remaining 200 grants (88%) were non-health-focused and categorized into four major research domains (Table 4). These included 34 grants on STEM diversity and student engagement, 20 on advanced technology and data science, 17 on cybersecurity and artificial intelligence, and 17 on environmental sciences. An additional 112 grants covered a wide range of topics, reflecting the breadth of NSF-supported research at HBCUs.

3.1.4 NIH and NSF funding patterns across public/private and Carnegie classification

Among the NIH and NSF grant-receiving HBCUs in our sample, 58% (18/31) were public and 42% (13/31) were private (Table 5). Looking specifically at agency-level distributions, 61% of NIH-funded awardees were public institutions and 39% private, reflecting NIH’s concentration in larger, state-supported universities. For NSF, awards were more evenly distributed, with 54% of recipients being public and 46% private. When viewed as proportions within each group, 56% of public HBCUs and 46% of private HBCUs received NIH funding, while 67% of public and 77% of private HBCUs received NSF funding. This suggests that NIH support was somewhat more concentrated among public institutions, whereas NSF resources reached both public and private HBCUs at comparable rates, with slightly greater participation among privates.

Of the 43 principal investigators (PIs) who responded in the qualitative portion of the study, the majority were affiliated with public HBCUs. Despite this distribution, no distinctive differences were observed in the experiences reported by faculty at public versus private institutions. Instead, respondents described shared challenges and opportunities, largely shaped by institutional context and funding-related constraints.

Carnegie-classified HBCUs were represented in our awardee sample, with seven institutions identified as one R1 and six R2, while the remaining were presented as non-Carnegie (Table 5). Overall, 23% (7/31) of awardees were Carnegie-classified HBCUs, compared to 77% (24/31) that were non-Carnegie. Carnegie institutions demonstrated a clear advantage, with most receiving awards from both NIH and NSF, whereas non-Carnegie institutions showed more fragmented funding patterns, often limited to a single agency. A subset of non-Carnegie HBCUs particularly smaller private liberal arts and theological colleges also received federal awards.

3.2 Phase 2: PI survey results (quantitative)

3.2.1 Sociodemographic and professional information

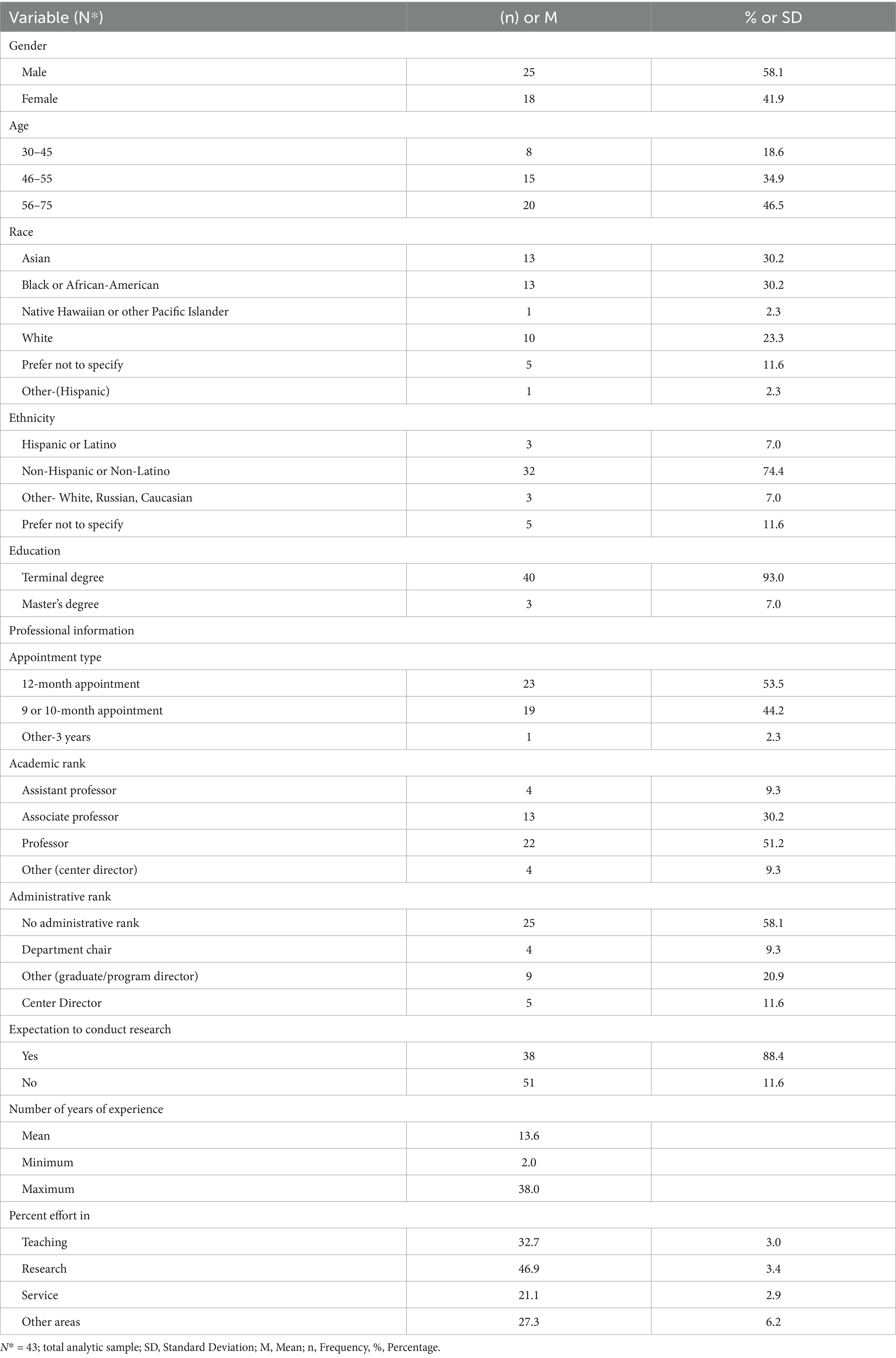

The survey included 43 faculty members from HBCUs across the United States. The majority were male (58.1%), with 18.6% between 30–45 years, 34.9% between 46–55 years, and 46.5% between 56–75 years. Racial composition was evenly split between Asian and Black or African American participants (30.2% each), with White participants comprising 23.3%. Most respondents identified as Non-Hispanic or Non-Latino (74.4%) (Table 6).

Regarding educational attainment, 93.0% held terminal degrees, while 7.0% had a Master’s degree. Appointment types varied: 53.5% were on 12-month contracts, 44.2% on 9 or 10-month contracts, and one respondent had a 3-year appointment. Academic ranks included Professors (51.2%), Associate Professors (30.2%), Assistant Professors (9.3%), and others (9.3%). Administrative roles were held by 41.8% of participants, including Department Chairs (9.3%), Graduate or Program Directors (20.9%), and Center Directors (11.6%). A significant majority (88.4%) were expected to conduct research. On average, participants had 13.6 years of experience at their current institution (range: 2–38 years). Effort distribution across responsibilities was: teaching (M = 32.7%, SD = 3.0), research (M = 46.9%, SD = 3.4), service (M = 21.1%, SD = 2.9), and other areas (M = 27.3%, SD = 6.2) (see Table 6).

Most survey respondents were affiliated with public HBCUs, while a smaller proportion represented private institutions. Institutional classifications also varied: most public universities were designated R2 (high research activity), only one was classified as R1, private medical schools were categorized as Special Focus institutions, and smaller private colleges were baccalaureate-level. This distribution highlights the diversity of research capacity and missions represented in the sample.

Respondents’ disciplinary backgrounds and research interests reflected both breadth and mission-driven priorities. Most were clustered in STEM and health sciences (biology, chemistry, neuroscience, computer science, and clinical research), while a smaller group represented social sciences, humanities, and education. Research interests often linked biomedical fields such as cancer, neuroscience, aging, and health disparities to community engagement and equity. Others emphasized STEM and computational fields, and a third theme centered on social justice, race and intersectionality. These patterns reflect the range of disciplinary expertise and research interests represented among HBCU faculty in the sample.

3.2.2 Experience in research activities at their institution

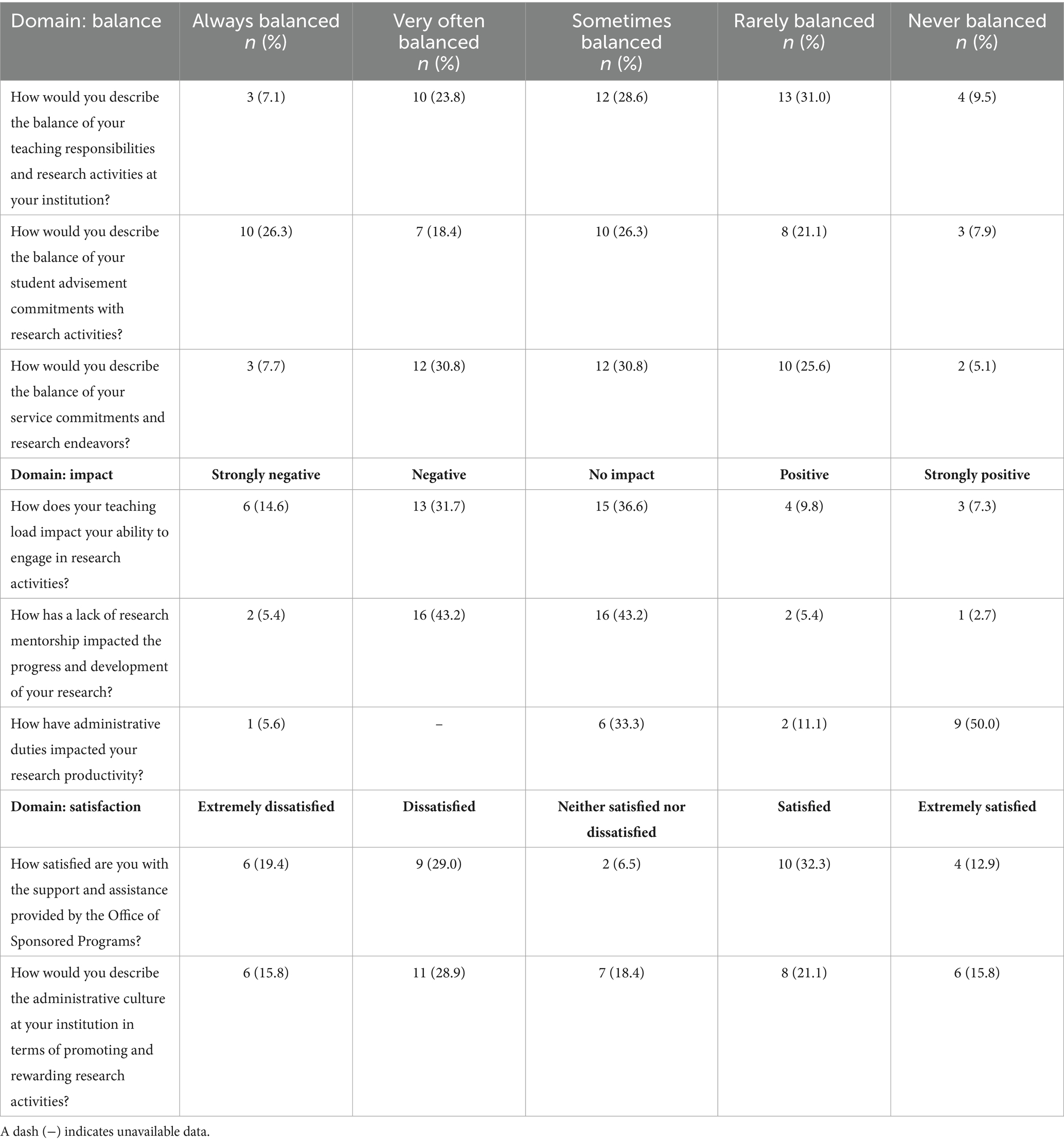

Participants described their activities balancing research, teaching, service commitments, and other work, their satisfaction with their institution’s administrative culture, and the collaborative research engaged in Table 7.

3.2.2.1 Balancing research activities with other academic responsibilities

Faculty members reported a range of experiences when balancing research with other academic responsibilities. Balancing research with teaching posed substantial challenges, with only 7.1% of respondents indicating they always achieved this balance, while 31.0% reported rarely doing so. Similarly, balance between student advisement and research responsibilities was inconsistent: 18.4% of participants reported very often achieving this balance, whereas 21.1% stated they rarely did. A comparable trend was observed in managing service commitments, with just 7.7% of faculty always maintaining balance, and 25.6% reporting rare success in doing so.

3.2.2.2 Impact of other responsibilities while doing research

Faculty reported that the impact of other responsibilities on research progress was extensive. Nearly half (46.3%) of the respondents indicated that teaching loads negatively or strongly negatively affected their ability to engage in research. Lack of structured research mentorship also emerged as a critical barrier: 48.6% of faculty members reported that the absence of mentoring opportunities had a detrimental impact on their research trajectory. Administrative duties were reported to be a particularly burdensome factor, with more than half of the participants strongly agreeing that such responsibilities reduced their capacity for productive research.

3.2.2.3 Satisfaction with institutional support and administrative culture

Participants’ satisfaction with institutional support and the administrative culture was mixed, highlighting areas for potential improvement. The Office of Sponsored Programs received polarized evaluations, with 48.4% of respondents expressing dissatisfaction or extreme dissatisfaction, while 45.2% reported satisfaction or extreme satisfaction. Similarly, perceptions of the institutional culture regarding the promotion and reward of research efforts were divided. While 44.7% of faculty were dissatisfied or extremely dissatisfied with their institution’s approach, 55.3% indicated satisfaction.

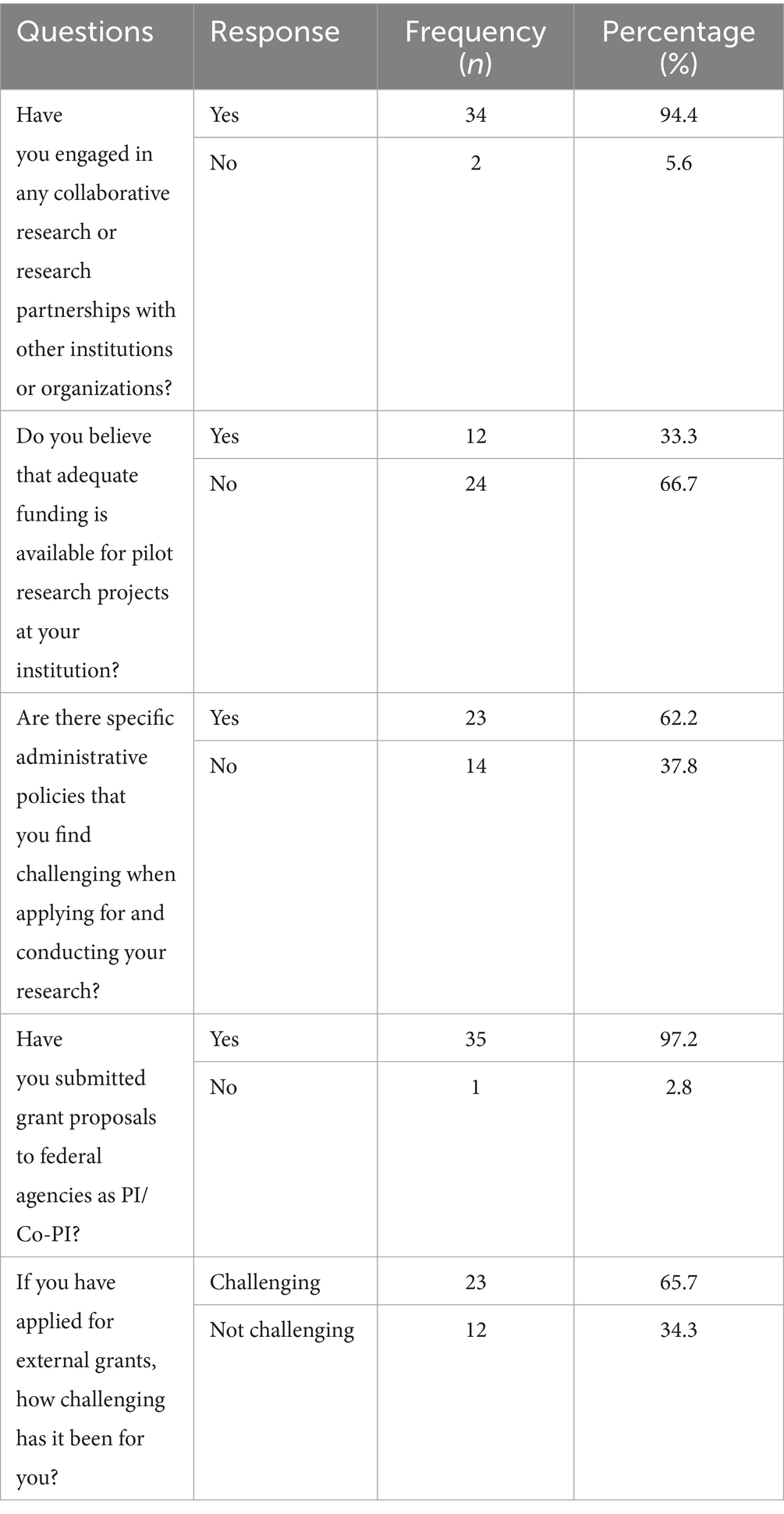

3.2.3 Collaborative research, funding availability, and administrative challenges

The vast majority of survey participants (94.4%) reported engaging in collaborative research including collaboration within their institutions or through partnerships with external organizations. Only a small fraction (5.6%) of faculty did not participate in collaborative research. Regarding pilot research funding, 66.7% of participants did not believe sufficient funding was available. These responses reflect the perceived limitations in financial support for initiating research projects.

In assessing institutional support for research, 55.3% of faculty members felt the administrative culture at their institution as either somewhat or very unsupportive of promoting and rewarding research activities. About institutional policies, 62.2% of participants found encountering specific policies that they found challenging during the application or implementation of research.

Among the faculty surveyed, 97.2% had submitted grant proposals to federal agencies as a PI or Co-PI. Of these, 65.0% reported that they found the process of applying for grants challenging. These results indicated the extent of grant-seeking activity and faculty perspectives on institutional and administrative support (Table 8).

3.3 Results from PI survey (qualitative)

The qualitative findings captured a wide range of faculty experiences navigating the complex balance among teaching, research, and service at HBCUs. Participants consistently pointed to administrative burdens, limited research support, and the lack of clear institutional policies as key obstacles. Many expressed the need for reduced administrative workload and increased assistance to meaningfully engage in research. Overall, the findings highlighted the importance of institutional changes to better support faculty for a more research-friendly academic environment.

3.3.1 Improving institutional support for balancing teaching and research

Participants highlighted the urgent need for greater institutional support to balance research with teaching and administrative duties. Key recommendations included hiring teaching and research assistants, postdoctoral fellows, and adopting team-based teaching models to reduce individual burden and teaching load. Faculty called for aligning teaching duties with research expectations, increasing research funding, and ensuring timely disbursement of funds. Several participants also advocated for smaller class sizes, more teaching support, and incentive structures to recognize research excellence. Many also emphasized the need to reduce administrative responsibilities and improve institutional administrator competence. As one department chair shared “My issue is the amount of administrative duties the chairperson has. There is no conflict between teaching and research but research and administrative duties are a different story” (Professor and Department Chair).

3.3.2 Improving administrative and work support for better service commitment

Participants reported a strong need for better administrative support for their service commitments. Many faculty members expressed frustration with handling administrative tasks like purchasing, travel orders, and reimbursement duties that detract from their core responsibilities. One assistant professor shared:

Having administrators work on purchasing, and signing receipt forms would help. We only have 1 purchasing agent for 70 faculty. This is not sustainable. I also perform all travel orders for my students. We have no purchase cards, so I have to pay out of pocket for travel and receive reimbursements months later. (Assistant Professor)

Faculty also called for more flexible work policies, including remote work options and realistic expectations, particularly for untenured faculty. As one associate professor noted, “Lessening the burden and the reduction of unrealistic duties and flexible work schedules would be helpful, particularly for untenured faculty” (Associate Professor). Additionally, suggestions were made for more effective meeting schedules and minimizing committee work. Participants mentioned the need for better planning and accountability.

3.3.3 Strengthening support for the student advisement role

Participants emphasized the need for improved administrative and advising support to reduce faculty burden and enhance the effectiveness of student advisement. They suggested the hiring of dedicated advisors, implementing technology to streamline advising processes, and protecting junior faculty from excessive advising duties. Many advocated for systemic changes such as reducing the number of advisees per faculty member and improving overall support for students. One department chair explained, “I include student advising as part of the Chair’s responsibilities. And, student advising is not the same as mentoring (research), which I do as well” (Department Chair).

Respondents also called for clearer role definitions between advising and mentoring, stricter adherence to advising deadlines, and the introduction of skill-building workshops. Better scheduling practices were proposed to optimize the advisement process.

Advising responsibilities take up a significant amount of time and often overshadow my ability to focus on research. Having dedicated advisors for students would allow faculty like me to maintain productivity in both teaching and scholarship. (Associate Professor)

3.3.4 Strengthening support from the Office of Sponsored Programs

Participants expressed the need for improved Office of Sponsored Programs (OSP) services to reduce administrative burden and streamline grant processes. They identified the need for better support for proposal writing, assistance with locating funding opportunities, and managing deadlines. Faculty emphasized the importance of dedicated administrative help for both pre- and post-award grant management, including purchasing and hiring. A respondent noted the need for stronger leadership; “There was a desire for better staffing within the OSP, including the appointment of a responsible director to oversee operations and ensure accountability” (Professor).

Having knowledgeable, communicative staff to guide faculty through grant processes was identified as a crucial area for improvement.

3.3.5 Expanding mentorship opportunities for researchers

Participants highlighted the need for stronger institutional support to develop structured and effective mentorship programs. Many advocated for leveraging both internal and external opportunities, including creating centralized pools of qualified mentors and encouraging cross-institutional collaborations. A key concern was that tenured faculty often disengage from research, limiting their mentoring capacity. Effective mentorship, respondents emphasized, requires dedicated time, institutional recognition, and compensation. As one respondent mentioned, “The mentors should be given enough free time and recognition. True mentoring is not supported because the time of a mentor is not compensated” (Associate Professor).

While structured programs were recommended, several participants valued informal mentorship based on strong personal relationships. Additional suggestions included incorporating mentorship activities into annual evaluations for senior faculty, offering mini-grants for mentor-mentee research, and establishing mentor groups across institutions. Participants also supported initiatives such as exchange programs and connections with federal agencies and industry to broaden mentoring networks and enhance career development opportunities.

3.3.6 Support and incentives to enhance research engagement

Participants highlighted the need for stronger institutional and financial support to sustain faculty research. Key recommendations included dedicated research funds, competitive salaries, reduced teaching loads, and recognition of research in faculty evaluations. Institutions were encouraged to provide protected time for research, assist with grant applications, and encourage a culture that values research alongside teaching. As one respondent shared, “The lack of support for faculty researchers is discouraging for them. The university administration cheers on and recognizes their efforts to get grants but does not provide support to sustain them” (Professor and Associate Vice President).

This sentiment reflects a broader call for policies that move beyond symbolic recognition to provide sustained, practical support for faculty research.

3.3.7 Resources to support grant submission and success

Participants emphasized the need for stronger administrative and professional support throughout the grant submission process. Skilled staff were seen as essential for assisting with grant writing, proposal reviews, and budget development. Some suggested mandatory mock reviews to strengthen applications prior to submission. In addition to procedural support, faculty especially early-career researchers stressed the importance of release time, start-up funds, equipment, and graduate student support. These resources were viewed as critical for initiating research and competing for external funding. As one senior participant explained,

New faculty need release time and startup funds so that they can get research going right out of the gate. Once they have spent a few years doing 100% teaching, they are not even able to take advantage of the pilot grant activities. (Professor and Associate Vice President)

Respondents also called for improved infrastructure, equitable access to pilot funding, and stronger support for community-engaged research. Respondents also emphasized the value of training opportunities such as workshops, peer reviews, NIH-led sessions, and the importance of mentorship for new faculty. As one respondent stated, “Being connected with senior collaborators and a productive research team doing similar research would have been invaluable; it significantly impact on my grant success rate” (Professor).

Simplifying grant procedures and increasing pre-award support were seen as essential steps to reduce administrative burdens and enhance competitiveness, which is also essential for successful grant submission.

4 Discussion

This section synthesizes the findings from the content analysis and PI survey, linking them to broader issues of diversity, institutional equity, and faculty development within higher education institutions. HBCUs play a crucial role in promoting inclusive research agendas, addressing health disparities, and building a diverse STEM and health sciences workforce. However, persistent structural barriers limit their full participation in national research priorities.

The first phase of the research revealed a strong emphasis on diversity in STEM, consistent with the NSF’s strategic goals to broaden participation among underrepresented groups. HBCUs have demonstrated leadership in advancing research in NCDs, CDs, mental health, and cybersecurity, areas that align with both national health priorities and future-focused technology needs (Ghebreyessus et al., 2022; NIST, 2018; World Health Organization, 2021; Hart, 2024). Their capacity to conduct research in community-based interventions reflects their engagement with local needs and health equity goals (Njoku and Murray, 2024; Gasman et al., 2017; Wilson and Guerra, 2021). These findings affirm the unique role of HBCUs in advancing innovation while promoting educational justice. Sustained investment would reinforce their capacity to promote equity and expand a diverse, innovative workforce.

The second phase of the PI survey documented that despite high engagement, HBCU faculty face significant barriers to research related to heavy teaching loads, administrative duties, and service expectations. Faculty frequently reported difficulties balancing research with student advisement, committee responsibilities, and departmental obligations. Team-based teaching models and reduced teaching loads for active researchers were recommended strategies to overcome these challenges (Escobar et al., 2021; Beech et al., 2020; Ransdell et al., 2021). Faculty stressed the need for institutions to reduce bureaucratic hurdles and reallocate administrative tasks away from researchers, enabling them to focus more on scholarship (Ives et al., 2023; Guthrie et al., 2017). These findings align with prior research showing that excessive burdens hinder productivity and reduce research time, reinforcing the need to streamline faculty workloads to enhance both productivity and satisfaction.

Mixed satisfaction with institutional support and administrative culture suggested opportunities for improvement. While some expressed satisfaction with certain aspects, there are clear areas for improvement, particularly in the OSP and the overall administrative culture for promoting and rewarding research. These findings highlight the urgent need for HBCUs to enhance their support structures from institutional administration to better support faculty researchers. These findings align with earlier studies (Gasman et al., 2023; Burton, 2023) and emphasize the importance of a supportive institutional culture.

Despite available funding, many HBCUs are unable to apply due to inadequate support capacity (Allen and Jewell, 2002). Mandatory mock reviews, proposal editing, and user-friendly application platforms were suggested as strategies to increase submission efficiency and success rates (Guthrie et al., 2017; Bollen et al., 2017). Simplifying grant processes remains a long-standing concern, echoing critiques from decades past (Cicchetti, 1991; Liang et al., 2021). Dedicated teams for grant preparation and post-award management would significantly reduce faculty burden and enable more robust engagement in externally funded research.

Effective mentorship was identified as both a challenge and a potential lever for faculty development. Participants noted that while informal mentoring relationships can be impactful, structured programs with clear expectations and incentives are essential to sustain long-term mentoring cultures (Bonner et al., 2024; Alexander, 2021; Höylä et al., 2016). New faculty especially benefit from guidance in grant writing, budgeting, and navigating institutional systems. Mini-grants to support mentor-mentee collaborations, cross-institutional mentoring with Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs) or industry partners, and recognition of mentoring in evaluations were proposed strategies to improve the academic environment (Ives et al., 2023; Burton, 2023). Promoting mentorship as a core institutional value could strengthen retention and career advancement among underrepresented faculty. Agencies could conduct regular reviews of grant distribution to identify and address regional or institutional inequities in funding, ensuring all HBCUs have equitable access to resources (Campbell et al., 2020; Pier et al., 2018).

These study findings reinforce a strategic role in advocating equitable research policies and institutional support structures at HBCUs. Our findings highlight the need for policies that reduce administrative barriers, strengthen mentorship, and expand equitable funding for HBCUs. Such measures would enhance faculty research capacity and advance national diversity goals, consistent with calls for inclusive research training environments (Harrington, 2022). Addressing institutional inequities in funding, simplifying administrative processes, and enhancing support systems are crucial for creating a research-conducive culture. We verified the current Carnegie research tiers for HBCUs as of 2025 (American Council on Education, 2025). Our findings indicate that while federally funded research remains concentrated in Carnegie-designated universities, both NIH and especially NSF programs have also provided meaningful support to non-Carnegie HBCUs with more limited research infrastructure (JBHE, 2025). Also, our findings of public-private funding patterns indicate that NIH support remains concentrated in larger public HBCUs, whereas NSF funding is more evenly distributed, offering greater access for smaller private institutions (Williams and Davis, 2019). Given the dynamic role of HBCUs in promoting diversity, agencies should regularly review grant distributions to ensure equitable access to resources across institutions (Sexton et al., 2025; Guthrie et al., 2017; Blundell et al., 2020). By using these findings to inform policy changes and support models, research in these institutions can cultivate a more inclusive and empowering environment for faculty at HBCUs and beyond. Eventually, this improvement is not just a count of faculty productivity; it is central to fulfilling national goals around innovation, public health, and inclusive excellence in higher education and research.

4.1 Study strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study lies in its exploratory mixed-methods approach, which allowed for both depth and breadth in understanding funding trends and investigator experiences. The integration of content analysis with investigator perspectives offered valuable insights into grant focus areas and institutional challenges. Although HBCUs encompass a diverse range of institutions, our study was limited by a small sample size constrains generalizability, but this exploratory study itself provides insights into engagement challenges for this population. The consistency of responses across participants adds weight to the identified themes while pointing to the importance of larger, future investigations.

Despite the small sample size, survey findings revealed several insights into obstacles faced by researchers at HBCUs, suggesting non-respondents may face similar or even greater barriers. This study demonstrates the importance of institutional leadership focusing on open dialog with faculty members toward solutions that benefit the researcher, institution, and the greater community. Furthermore, the reliance on self-administered answers for open-ended questions may restrict the depth of information gathered, as respondents might not have offered comprehensive details in their responses. Employing alternative data collection methods for more detailed insights from respondents would be beneficial for future studies. Since our sample was limited to NIH and NSF grantees, we did not capture the perspectives of unfunded applicants; future studies should include these voices to better assess barriers faced by HBCUs. Moreover, this study was limited to awarded HBCUs only. Future studies should compare HBCUs award trends with non-HBCU institutions to provide a clearer benchmark for assessing funding disparities.

5 Conclusion

The content analysis of NSF and NIH grants awarded to HBCUs reveals these institutions’ diverse research priorities and strengths, particularly in advancing inclusive and community-relevant scholarship. These findings highlight the critical role of HBCUs in driving innovation and addressing systemic disparities in academia. Further exploration is needed to understand the factors contributing to regional funding gaps and how such inequities can be addressed to help all HBCUs realize their full research potential. Survey findings highlight the urgent need to improve faculty support in workload balance, mentorship, and administrative infrastructure to promote a more conducive research environment. This study provides a foundation for future inquiry into strengthening HBCUs’ research capacity. Recent federal reports show over $140 million in NIH and NSF grant cancelations at HBCUs, including more than $10 million at the sole R1 HBCU, which disrupts the research environment (Jasper, 2025). These developments highlight funding volatility and reinforce the need to interpret trends carefully, as short-term policy shifts may affect institutions differently based on research capacity. By spotlighting structural and strategic needs, it contributes to broader efforts to enhance diversity and inclusion in higher education. These insights offer actionable strategies for institutional leaders to better support historically underrepresented researchers and make equity a systemic priority. With sustained support and targeted investment, HBCUs are positioned to play an increasingly transformative role in shaping a more diverse and just academic landscape. By building on their existing capabilities and addressing systemic challenges, HBCUs have the potential to play an even more transformative role in driving innovation, equity, and social change.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Aging under Grant number P30 AG059294.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the participants for generously giving their time during the virtual data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

ABFE (2023). Philanthropy and HBCUs foundation funding to historically black colleges and universities. New York, NY: ABFE.

Alexander, V. (2021). A case study: An examination of historically black colleges and universities’ recruitment of non-black students. Columbus, GA: Columbus State University.

Allen, W. R., and Jewell, J. O. (2002). A backward glance forward: past, present and future perspectives on historically black colleges and universities. Rev. High. Educ. 25, 241–261. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2002.0007

American Council on Education. Carnegie classification of institutions of higher education [internet]. (2025). Available online at: https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/.

Annie, M. $100 million gift from Lilly Endowment to united negro college fund will support HBCU endowments. (2024).

Beech, B. M., Norris, K. C., Thorpe, R. J., Heitman, E., and Bruce, M. A. (2020). Conversation cafés and conceptual framework formation for research training and mentoring of underrepresented faculty at historically black colleges and universities: obesity health disparities (OHD) pride program. Ethn. Dis. 30, 83–90. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.1.83

Blundell, G. E., Castañeda, D. A., and Lee, J. (2020). A multi-institutional study of factors influencing faculty satisfaction with online teaching and learning. Online Learn. J. 24, 229–253. doi: 10.24059/olj.v24i4.2175

Bollen, J., Crandall, D., Junk, D., Ding, Y., and Börner, K. (2017). An efficient system to fund science: from proposal review to peer-to-peer distributions. Scientometrics 110, 521–528. doi: 10.1007/s11192-016-2110-3

Bonner, F. A., Marbley, A. F., Flowers, A. M., Burrell-Craft, K., Jennings, M. E., Louis, D. A., et al. (2024). Reconciling our strivings: historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in contemporary contexts. Gift. Child Today 47, 45–64. doi: 10.1177/10762175231205917

Burton, A. Historically black colleges and universities’ faculty experiences with online course design. (2023).

Campbell, K. M., Kaur-Walker, K., Singh, S., Braxton, M. M., Acheampong, C., White, C. D., et al. (2020). Institutional and faculty partnerships to promote learner preparedness for health professions education. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 8, 1315–1321. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00893-6

Cicchetti, D. V. (1991). The reliability of peer review for manuscript and grant submissions: a cross-disciplinary investigation. Behav. Brain Sci. 14, 119–186.

Dahl, S., Strayhorn, T., Reid, M., Coca, V., and Goldrick-Rab, S. (2022). Basic needs insecurity at historically black colleges and universities: A #RealCollegeHBCU report. Philadelphia, PA: Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice.

Echegoyen, L. E., Mehta, K. M., Hueffer, K., Kagey, J. D., Keller, T. E., Morgan, K. M., et al. (2025). Factors associated with applying to graduate/professional degrees for students engaged in undergraduate research experiences at minority serving institutions. Front. Educ. 10:1589105. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1589105

Elo, S., and Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Epps, I. E., and Guidry, J. J. (2009). Building capacities among minority institutions to conduct disability research: what is the problem. J. Minority Disabil. Res. Pract. 3, 1–10.

Escobar, M., Bell, Z. K., Qazi, M., Kotoye, C. O., and Arcediano, F. (2021). Faculty time allocation at historically black universities and its relationship to institutional expectations. Front. Psychol. 12:734426. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734426

Gasman, M., Ekpe, L., Ginsberg, A. C., Lockett, A. W., and Samayoa, A. C. (2023). Why aspiring leaders choose to lead historically black colleges and universities. Innov. High. Educ. 48, 637–654. doi: 10.1007/s10755-022-09644-3

Gasman, M., Smith, T., Ye, C., and Nguyen, T.-H. (2017). HBCUs and the production of doctors. AIMS Public Health 4, 579–589. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2017.6.579

Gasman, M., and Thai-Huy, N. (2019). Making black scientists: A call to action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ghebreyessus, K., Ndip, E. M., Waddell, M. K., Asojo, O. A., and Njoki, P. N. (2022). Cultivating success through undergraduate research experience in a historically black college and university. J. Chem. Educ. 99, 307–316. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.1c00416

Guthrie, S., Ghiga, I., and Wooding, S. (2017). What do we know about grant peer review in the health sciences? Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Harrington, M. A. (2022). Diversity in neuroscience education: a perspective from a historically black institution. J. Neurosci. Res. 100, 1538–1544. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24911

Harrington, T. G., Melissa, A., Smolinski, A. L., and Mazen, S. (2015). In infusing undergraduate research into historically black colleges and universities curricula. Washington, DC: Council on Undergraduate Research.

Hart, D. Improving HBCU cybersecurity programs to build a capable workforce. [Internet] (2024). Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2024/04/30/improving-hbcu-cybersecurity-programs-to-build-a-capable-workforce/ (Accessed October 6, 2025).

Hoppe, T. A., Litovitz, A., Willis, K. A., Meseroll, R. A., Perkins, M. J., Hutchins, B. I., et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. (2019).

Höylä, T., Bartneck, C., and Tiihonen, T. (2016). The consequences of competition: simulating the effects of research grant allocation strategies. Scientometrics 108, 263–288. doi: 10.1007/s11192-016-1940-3

Hsieh, F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Ives, J., Drayton, B., Hobbs, K., and Falk, J. (2023). The impact of a multimodal professional network on developing social capital and research capacity of faculty at historically black colleges and universities. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 7391–7411. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11464-z

JBHE. HBCUs that currently are designated R2 research universities [internet]. (2025). Available online at: https://jbhe.com/2025/02/hbcus-that-currently-are-designated-r2-research-universities/.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 413.

Liang, C. M. K., LR, D. K., and Hashemi-Beni, L. (2021). Best practices and lessons learned in grant writing for ag/applied economists to engage in interdisciplinary studies. Appl. Econ. Teach. Resour. 3, 25–42. doi: 10.22004/ag.econ.312078

Livingston, V., Nevels, B. J., Chung, I., Ericksen, K. S., Duncan, E., Manley, C. K., et al. (2023). The enigma of resilience at an HBCU during a global pandemic. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 33, 825–845. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2022.2100028

Lumivero. NVivo. Version 14 [Internet] Denver, CO: Lumivero; (2023). Available online at: https://lumivero.com/product/nvivo-14/ (Accessed October 6, 2025).

Mann, B. (2021). A publication of the National Center for education statistics at IES. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Matthews, C. M. (2008). Federal research and development funding at historically black colleges and universities. Washington, DC: U.S. Congress.

Moore, C. L., Aref, F., Manyibe, E. O., and Davis, E. (2016). Minority entity disability, health, independent living, and rehabilitation research productivity facilitators: a review and synthesis of the literature and policy. Langston, OK: Langston University Rehabilitation Research and Training Center Contract No.: 2.

Moore, C. L., Johnson, J. E., Manyibe, E. O., Washington, A. L., and Uchegbu, N. (2012). Barriers to the participation of historically black colleges and universities in the federal disability and rehabilitation research and development enterprise: The researchers' perspective. Langston, OK: Langston University Rehabilitation Research and Training Center.

Njoku, N., and Murray, L. (2024). Greater funding, greater needs: A report on HBCU funding during COVID-19 and a case for continued support. Washington, DC: United Negro College Fund Contract No.: 2.

Pamela, L. (2010). Partnerships and collaborations in higher education. ASHE High. Educ. Rep. 36, 1–115. doi: 10.1002/aehe.3602

Pier, E. L., Brauer, M., Filut, A., Kaatz, A., Raclaw, J., Nathan, M. J., et al. (2018). Low agreement among reviewers evaluating the same NIH grant applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2952–2957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1714379115

Qualtrics, X. M. Qualtrics XM: The leading experience management software [internet] Provo (UT)2023 (2025). Available online at: https://www.qualtrics.com.

Rana, K. S., Alvey, E., Flavell, C. R., Gough, J., and Mahomed, A. (2025). Editorial: advancing equity: exploring EDI in higher education institutes. Front. Educ. 10:1621185. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1621185

Ransdell, L. B., Lane, T. S., Schwartz, A. L., Wayment, H. A., and Baldwin, J. A. (2021). Mentoring new and early-stage investigators and underrepresented minority faculty for research success in health-related fields: an integrative literature review (2010-2020). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1–35. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020432

Rebekah, B. Amid HBCUs’ financial challenges, New Funding Offers Renewed Hope. Nonprofit Quarterly. (2024).

Sara, W. Striving for the ‘gold standard’[internet]: Insight higher education. (2022). Available online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/11/02/some-hbcus-strive-r-1-status-record-research-dollars (Accessed October 6, 2025).

Sexton, K. K., Gibbons, M. M., Hardin, E. E., Cook, K. D., Hoch, J., and Ault, H. R. (2025). Historically underrepresented students: influences of rurality, parent education level and family income on graduate school intentions. Front. Educ. 10:1569432. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1569432

Toldson, I. A. (2017). Drivers and barriers of success for HBCU researchers submitting STEM proposals to the national science foundation (editor’s commentary). J. Negro Educ. 86, 415–421. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.4.0415

Upton, R., and Tanenbaum, C. (2014). The role of historically black colleges and universities as pathway providers: Institutional pathways to the STEM PhD among black students. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Waite, R., Varghese, J., VanRiel, Y., Smith, T., Singletary, G., Shtayermman, O., et al. (2023). Promoting health equity with HBCUs: breaking away from structural racism. Nurs. Outlook 71, 123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2022.101913

Williams, K. L., and Davis, B. L. (2019). Public and private investments and divestments in historically black colleges and universities. Educ. Inf. Technol. 24, 233–245. Available online at: https://www.acenet.edu/Documents/Public-and-Private-Investments-and-Divestments-in-HBCUs.pdf

Williams, E. M., Nelson, J., Francis, D., Corbin, K., Link, G., Caldwell, T., et al. (2022). Formative research to promote lupus awareness and early screening at historically black college and university (HBCU) communities in South Carolina. BMC Rheumatol. 6:92. doi: 10.1186/s41927-022-00323-6

Wilson, T., and Guerra, R. (2021). WIP: From lack of time to stigma: Barriers facing faculty at minority serving institutions pursuing federally funded research. Lincoln, NE: Frontiers in Education Conference.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases, rehabilitation and disability. [internet] Geneva, CH: WHO; (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/research (Accessed October 6, 2025).

Yasmin, B. Advancing equity through HBCU leadership [Internet]. PEAK; (2025). Available online at: https://www.peakgrantmaking.org/insights/advancing-equity-through-hbcu-leadership/

Keywords: HBCU, federal funds, content analysis, NIH, NSF, investigators’ experience

Citation: Akter S, Hucek FA, McCollum Q, Levkoff SE and Friedman DB (2025) Exploring research and scholarship at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: insights from federal funding patterns and investigator experiences. Front. Educ. 10:1665901. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1665901

Edited by:

Anil Shanker, Meharry Medical College, United StatesReviewed by:

Omari Swinton, Howard University, United StatesReginald Miller, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, United States

Copyright © 2025 Akter, Hucek, McCollum, Levkoff and Friedman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela B. Friedman, ZGZyaWVkbWFAbWFpbGJveC5zYy5lZHU=

Sayema Akter1

Sayema Akter1 Quentin McCollum

Quentin McCollum Sue E. Levkoff

Sue E. Levkoff Daniela B. Friedman

Daniela B. Friedman