- 1Department of Psychology, Education and Child Studies, Erasmus University of Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 2iHUB – Alliance of Youth Care, Mental Health Care, and Educational Organizations, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 3Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 4Research Centre Innovations in Care, Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 5Research Centre Urban Talent, Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, Rotterdam, Netherlands

Introduction: Youth in residential care (RC) face the highest risk of unfavorable educational outcomes among all out-of-home care (OHC) settings. While some consistent factors are known from previous research, the voices of youth and their caregivers remain largely absent, limiting insight into their unique context and opportunities for meaningful improvement.

Methods: This participatory qualitative study examined the educational pathways of 26 youth (aged 12–21) with RC experience and 7 caregivers. Autobiographical interviews explored participants’ experiences and elicited recommendations for professional practice. Data were analyzed using a Grounded Theory approach. In line with participatory action research (PAR), youth with lived experience contributed as co-researchers throughout the study.

Results: Participants’ experiences were organized into four key themes: (1) awareness of difficulties and their impact, (2) the need for and lack of perspective, (3) longing to be seen and heard, and (4) personal strengths and perceived support. Regarding recommendations for professionals, youth and caregivers emphasized the importance of being genuinely seen and heard, offering attuned motivational support, enabling youth competencies, and fostering a broader, future-oriented perspective involving caregivers and trusted network figures. A genuine connection between professionals and youth was seen as essential, yet often missing in practice.

Discussion: These findings underscore the need for trauma-informed, youth-centered approaches in RC. Key implications include co-constructing educational pathways with youth promoting autonomy, involving caregivers and trusted network members, and equipping professionals with trauma-informed training. By fostering collaboration and relational continuity, professionals can strengthen both educational engagement and psychosocial well-being among youth in RC.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, research has consistently demonstrated unfavorable educational outcomes for youth in Out-of-Home Care (OHC) (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021; Montserrat and Casas, 2018; O’Higgins et al., 2017; Vinnerljung et al., 2005). OHC refers to 24-h care arrangements in which children and adolescents are temporarily or permanently removed from their families of origin due to adverse family circumstances and/or severe behavioral or emotional difficulties. Placement types range from kinship care and non-relative foster care to residential care (RC) (Gao et al., 2017; Huefner et al., 2010).

Among these, youth in RC occupy the most vulnerable position regarding unfavorable educational pathways and outcomes. RC is defined as professionally staffed group living facilities, not licensed as hospitals, that offer care or mental health treatment across a continuum of settings from family-like group homes to secure residential and psychiatric facilities (Barth, 2002; De Swart et al., 2012). Youth in RC are disproportionately represented in special education (Lagerlöf, 2016; Montserrat and Casas, 2018), exhibit high rates of school dropout (Ozawa and Hirata, 2019), and demonstrate poorer academic achievement and educational attainment compared to their same-aged peers in other forms of OHC (e.g., kinship care and foster care). Consequently, they experience the most disadvantaged socio-economic outcomes throughout adulthood (Sacker et al., 2022).

These unfavorable outcomes are concerning, particularly because positive educational pathways play a crucial role in youth development. Such pathways—defined as the education and care received by youth over time, including transitions between different types of schooling (Hanson et al., 2001)—when characterized by stability and support, are associated with better mental health and more favorable social and economic outcomes in adulthood. (Dill et al., 2012; Sacker et al., 2022). Despite the aforementioned adverse outcomes, which place youth in RC at a disadvantage, relatively little research has been conducted on this group in relation to their educational pathways (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021).

1.1 Previous research: factors influencing educational pathways for youth in RC

Previous research has shed light on specific factors impacting the educational pathways of youth in RC. Recently, a systematic review by Garcia-Molsosa et al. (2021) identified consistent risk and protective factors impacting the educational pathways of youth in RC. One of these consistent factors is the presence or absence of supportive relationships with caregivers and teachers. Support, affection, positive perceptions, attitudes, and expectations of caregivers are positively correlated with the academic achievement of youth in RC. However, youth in RC often lack these supportive relationships. For example, these youth often experience a lack of parental involvement, low academic expectations, and a lack of engagement in school-related activities, as well as instability among professional staff in RC (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021; Marion and Mann-Feder, 2020). Youth in RC are also at risk of normative, controlling, or repressive reactions from professionals in RC and schools, including the use of seclusion and restraint (Bramsen et al., 2019, 2021; De Valk et al., 2017; LeBel et al., 2010). As a result, youth feel unaccepted and experience a lack of trusting, supportive relationships (Bramsen et al., 2019, 2021).

Besides the importance of relationships with supportive adults, relationships with peers also play a critical role in the educational pathways and outcomes of youth in RC. For example, research indicates that supportive relationships, a sense of belonging, and connectedness are positively correlated with school satisfaction and adjustment for youth in RC (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021). Conversely, peer relationships can be challenging and a source of conflict for youth in RC, often due to stigmatization, difficulties in developing effective social skills, and a higher risk of social exclusion (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021; Stein, 2012; Trout et al., 2008).

Furthermore, the numerous placements and school settings of youth in RC disrupt the ability to build stable relationships with peers, teachers, and other important adults (Herbers et al., 2013). The number of placements and school changes is consistently related to poor educational outcomes, with youth in RC showing the highest prevalence of placement and school changes compared to youth in foster care and kinship care (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021).

Lastly, one of the most consistent factors strongly associated with lower educational attainment among youth in RC is the presence of individual factors such as gender (boys) and the severity of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021; Harder et al., 2014; Montserrat and Casas, 2018). Youth in RC tend to be the group in OHC that occupies the most vulnerable position considering the severity of problems on individual, family, and peer dimensions (Leloux-Opmeer et al., 2016). Garcia-Molsosa et al. (2021) stated that ‘it may be concluded that the “particularly difficult profile” of children in RC makes them more prone to school failure and dropout…’ (Garcia-Molsosa et al., 2021, p. 8).

Although existing evidence has identified consistent factors influencing the educational pathways of youth in RC, it often fails to move beyond the notion of this aforementioned ‘difficult profile.’ The specific lived experiences and contextual realities of this group are insufficiently acknowledged. Moreover, critical questions remain regarding the mechanisms, timing, and circumstances under which these factors impact educational outcomes (Marion and Tchuindibi, 2024). Empirical research on effective strategies to improve the educational pathways of youth in RC remains limited.

1.2 The importance of youth and caregiver voices

To date, qualitative studies that include the voices of youth in RC are scarce. However, evidence indicates that youth perspectives may reveal different priorities and forms of knowledge compared to studies that rely solely on adult perspectives, such as those of health care providers, caregivers, and policy makers (Holland, 2009). Including youth perspectives in research can be conducted using Participatory Action Research (PAR; International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research [ICPHR], 2013), a methodology aimed at improving the conditions of a specific group (youth and their caregivers) through equal collaboration between participants, such as youth with lived experience and researchers from the outset. Fine (2018) sharpens this commitment by centering questions of power, injustice, and voice, urging researchers to critically reflect on their positionality, interrogate existing power structures, and form meaningful coalitions that challenge the status quo. This critical PAR (CPAR) approach emphasizes creating collaborative spaces where previously silenced perspectives are heard and valued, enabling historically marginalized groups to contribute to new possibilities and transformative change.

Although collaboration with youth with lived experience in the role of co-researchers is still scarce in the field of youth care, a recent review in mental health care concluded that these experts can provide an “insider perspective in the data analysis and design process” (de Beer et al., 2024; p. 2477). Consequently, this leads to a deeper understanding of the results and the targeting of relevant interventions. Moreover, for youth themselves, an active (and expert) role may have an empowering effect, as it allows them to create change based on their experiences (Kim, 2016).

1.3 The present study

The aims of the present qualitative study are therefore (1) to gain in-depth insights into the educational pathways of youth in RC and (2) to provide recommendations for improvement to professionals in the field of youth care and special education settings by focusing on the perspective of youth and caregivers. This study will employ a PAR approach engaging youth with lived experience as co-researchers.

2 Methods

2.1 Setting and methodology framework

The current study is part of the research project Stay on Track in the Academic Workplace of Transforming Together (ST-RAW; Samen Transformeren Rotterdamse Academische Werkplaats in Dutch). Stay on Track (SOT) is a four-year Dutch initiative specifically aimed at improving the educational pathways for youth who have experienced or are currently experiencing RC. This project was led by researchers from Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences (part of the Stay on Track consortium). It involved seven youth care and (special) secondary education institutions within the Rotterdam metropolitan region (Rijnmond area). The consortium also engaged a broad range of stakeholders from practice, including youth, their caregivers, teachers, and professionals, as well as representatives from policy, academia, and education within the Rijnmond area in the Netherlands. The Stay on Track (SOT) project is grounded in the principles of CPAR (Fine, 2018; International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research [ICPHR], 2013).

Within the SOT project, the perspectives of youth were central. In the early stages of the project, youth with lived experience of interrupted educational pathways due to personal, social, or psychological problems were engaged as co-researchers. This included youth who had direct involvement in youth care and special education, as well as those affected by insufficient access to such support. Four youth with lived experiences were recruited via an open call following an open invitation disseminated through the seven participating organizations, Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences, and an expert-by-experience network in youth care (Expex). Interested candidates submitted a brief motivation letter and participated in an introductory conversation designed to explore mutual expectations and assess whether collaboration with other members of the Stay on Track Consortium (researchers from Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences) would be a suitable fit for all involved. Some youth chose not to continue thereafter, either because participation did not align with their current life circumstances or was perceived as too demanding. Active efforts were made to ensure that the final group of four youth with lived experience embodied diversity across gender, ethnicity, educational background, and experiences in special education and youth care, including various forms of RC with variation in both duration and placement type (e.g., open, secure, and mental health settings).

The four youth with lived experience were integral members of the SOT Consortium, actively participating in all key meetings that shaped the project, including its development, data analysis, and dissemination of findings. Although the initial objective to enhance the educational pathways of youth living (temporarily) outside their homes was established before their involvement, the youth with lived experience made substantive contributions. These included refining the project’s focus, as reflected in the renaming from “Back on Track” to “Stay on Track,” assisting in the development of interview protocols, and contributing to the creation of recruitment materials, including written invitations, flyers, posters for partner organizations, and videos. Youth with lived experience conducted a subset of the interviews. Additionally, they were involved in coding the interview data and actively contributed to interpretative discussions regarding the results and manuscript preparation. To facilitate meaningful youth engagement, researchers from the SOT Consortium at Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences provided collaborative training and professional development sessions covering interviewing techniques, qualitative data analysis and coding, spoken word methodologies, and strategies for knowledge dissemination.

The current qualitative study represents the initial phase of the SOT project, focusing on exploring the perspectives of youth and caregivers regarding their educational pathways in RC. Findings from these interviews will serve as the foundation for collaboratively developing practical building blocks that enhance the alignment of youth care and education. This co-creation process will involve the SOT Consortium, including youth with lived experience and stakeholders, such as youth from the participating organizations, ensuring that the resulting interventions are grounded in lived experience and tailored for effective application within youth care and educational settings.

2.2 Procedure

We identified and selected participants through convenience sampling, inviting youth aged 12 to 23 years with experience in RC (present or past) to participate. To maximize variation in sociodemographic characteristics, such as gender, age, ethnic background, intellectual and psychological disabilities, and RC or educational setting, recruitment was conducted via seven participating organizations offering (special) secondary education and youth care services, with a distinct focus and client population. Recruitment efforts were concentrated in the Rotterdam metropolitan region (Rijnmond area) in the Netherlands, a region marked by high levels of ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. Recruitment materials, including an information letter, were developed through an intensive collaboration among researchers, youth with lived experience, and experienced expert caregiver groups. Furthermore, an accompanying video featuring the four youth with lived experience, inviting other youth to participate in the interviews based on their own experiences, was distributed. In the case of caregiver participants, initial outreach was conducted by youth participants themselves. Due to a limited initial response, a supplementary invitation was later distributed by the chair of the experience expert council of one of the participating youth care organizations. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, their confidentiality, and their voluntary participation in the project. They could withdraw from the study at any time.

After participants agreed to participate, we scheduled the interview online (during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19 pandemic)) or, if possible, at a location of their choice. Before the interview, informed consent procedures were carefully explained to each participant to ensure full understanding. Written and oral consent were obtained before participation. Informed consent for youth under the age of 16 was given by the parent or guardian and by the youth themselves (for those aged 12–16 years). Students and experienced expert co-researchers from the Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences conducted the interviews between October 2020 and February 2021. Interviewers were trained and supervised by experienced interviewers and researchers (IB and SD; Consortium SOT). One of the authors (AP) conducted additional interviews between March and May 2022 to complete the data regarding caregivers’ perspectives. Participants received a €15 gift card upon completion of the interview. The interviewers and researchers had no prior knowledge of the participants and vice versa. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min, were audio-recorded, and were transcribed verbatim.

All participants (28 youth and eight caregivers) completed the interview. One parent withdrew their participation after the interview. Two youth participants were excluded from the final sample due to unverifiable informed consent documentation at the time of data verification, resulting in a final sample of 26 youth participants and seven caregivers. We applied the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (Tong et al., 2007) to promote transparency and ensure clear and comprehensive reporting of the study methods.

2.3 Participants

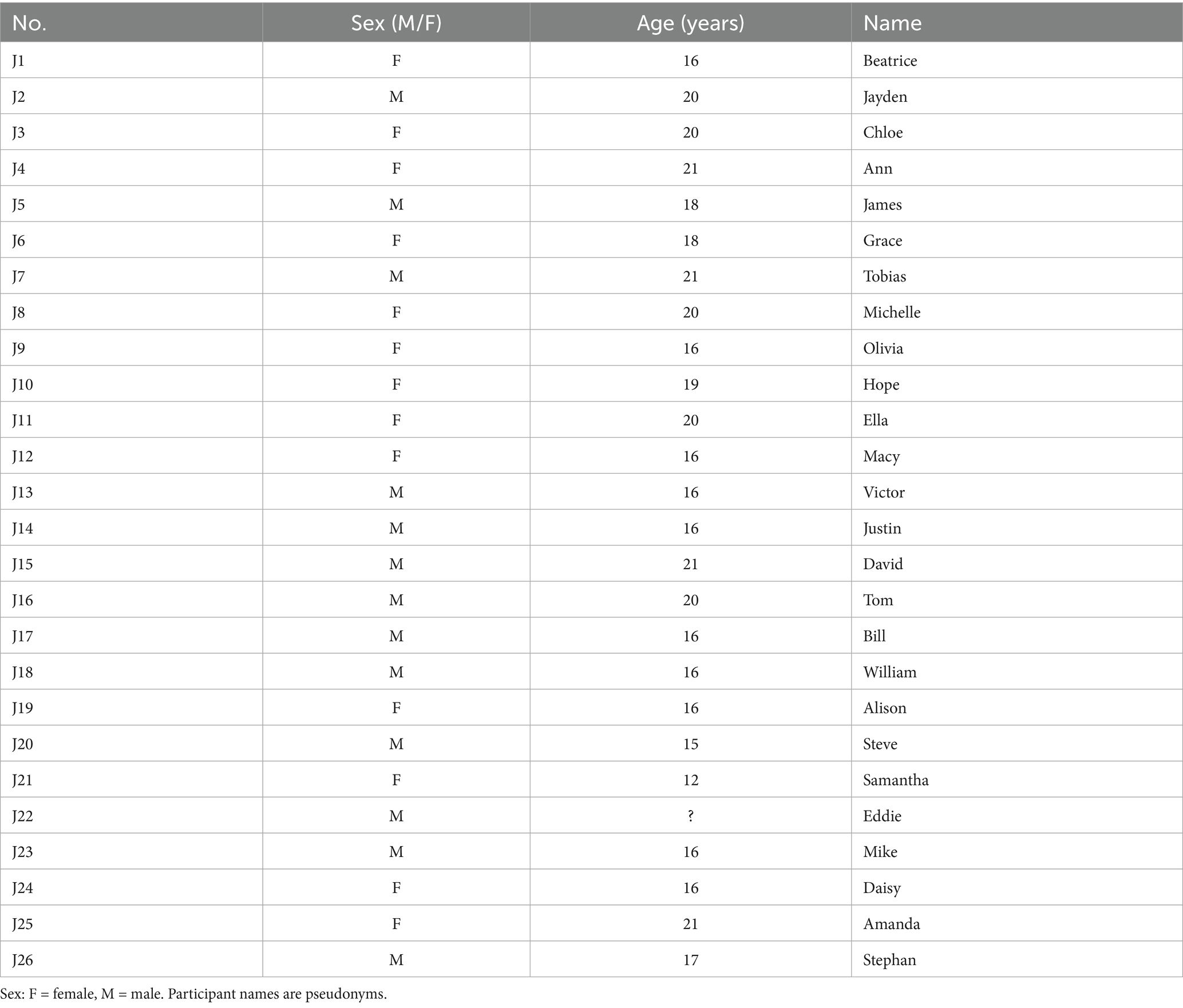

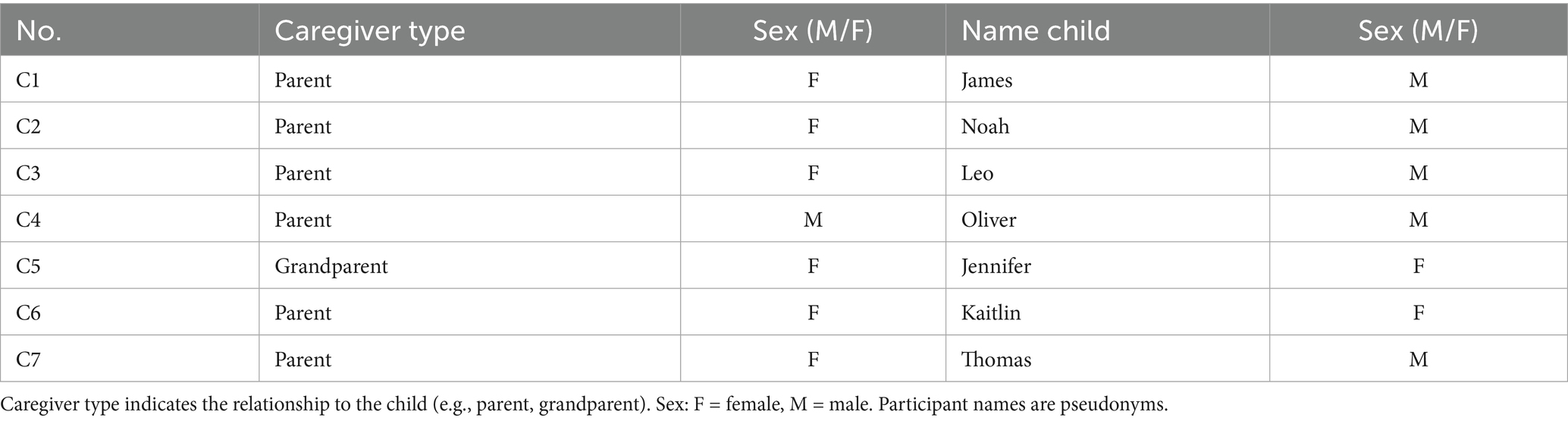

The final sample consisted of 26 youth participants (13 boys and 13 girls) in the age range between 12 and 21 years old (M = 17.76; SD = 2.42; see Table 1 for demographics) and seven caregivers (see Table 2).

2.4 Instruments

To gain insight into the educational pathways of youth and their parents, we used in-depth autobiographical interviews (Nijhof, 2000). Interviews were semi-structured with a set of open-ended standardized questions guided by a life course perspective divided over three main topics: (i) the educational pathway of youth (e.g., what was it like for you? Can you tell your story about your life and school?); (ii) their views regarding their academic future (e.g., you have talked about your life and school career so far. How would you like things to continue with school?); and (iii) recommendations for youth care and educational professionals (e.g., what recommendations, tips, or advice do you have for us from your story about your school career? What can the school or the institution learn from you?). The formulations of the questions in the interview format were constructed in collaboration with researchers (FC, AP), the Stay on Track consortium (IB, SD, youth with lived experience), and experts from experience caregiver groups, allowing and encouraging participants to speak openly.

2.5 Data analysis

Since the interviews were performed by different students, two authors (AP and KB) evaluated the interviews for quality (Moerman, 2014). We created a checklist to assess several aspects of quality, whether there was information available regarding the youth’s educational pathways (relevance), respondents’ feelings or personal events related to educational pathways (depth), the amount of information available from the respondent (amount), and the extent to which respondents described different themes and codes (elaborateness). Furthermore, we checked if the answers of participants were influenced by probing mistakes of the interviewer (suggestive questions or making two or more requests in one return; Moerman, 2014). Authors KB and AP agreed not to include a few paraphrases from youth within some interviews when these were clearly influenced by probing mistakes (e.g., interviewer: ‘I guess that made you sad? Youth: ‘Yes, indeed’).

After transcribing the interviews, three pairs of authors (IB, FC, SD, and youth with lived experience) each coded two youth interviews independently using the Grounded Theory approach (Corbin and Strauss, 1990). Each pair was composed of a researcher and one youth with lived experience serving as a co-researcher. The three pairs of authors discussed the coding results of the six interviews together afterwards and agreed on a set of codes to apply for subsequent transcripts, organized in a code tree. Afterwards, seven researchers from one of the youth care organizations involved in the project performed further coding using Microsoft Excel for the youth interviews. Authors AP and KB coded the seven interviews with caregivers.

We used a combined approach of deductive and inductive analysis (Van Staa and Evers, 2010). Authors and the consortium discussed new codes that arose and created a second code tree, which was applied to all previous and subsequent transcripts. Afterwards, authors KB and CK performed axial and selective coding. No additional codes emerged after 35 interviews, indicating that data saturation was reached and no further interviews were needed. Subsequently, the first author (KB) deductively compared the key themes by rereading the transcripts (using the bracketing method), thereby limiting possible adverse effects of prejudices that could have affected the research process (Tufford and Newman, 2012).

The final code tree and results were discussed with the youth with lived experience of the SOT Consortium and with experts by experience caregivers. Both groups agreed on the code tree and felt that their stories were represented accurately.

3 Results

“If I just got the right help—maybe talked to someone about it, about my aggression—then things would just be better now. I would be in school, doing a higher level. Maybe I would have graduated in two years, maybe I would even have my own place, and a good income, you know, just everything. I would be further ahead in society than I am now.

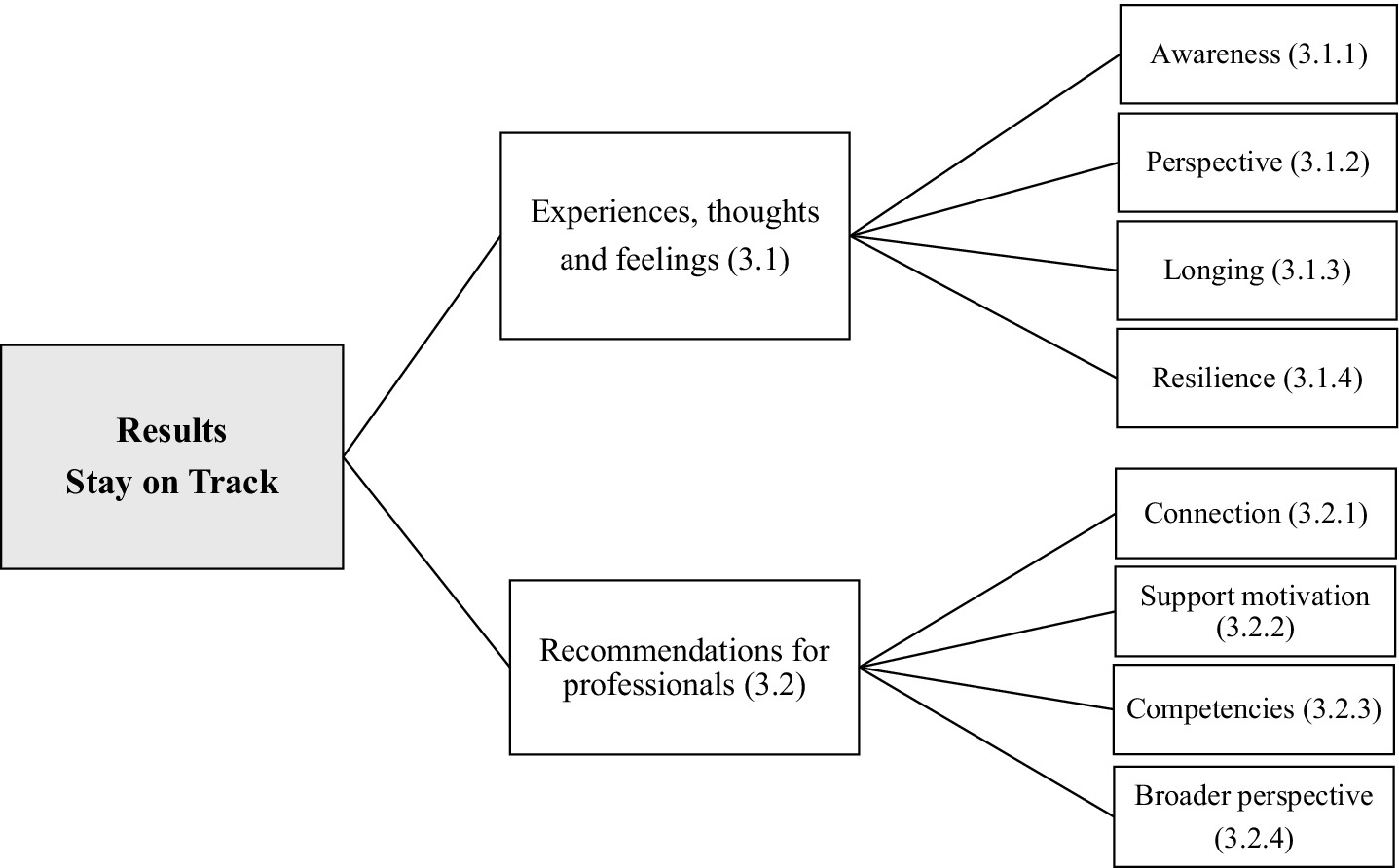

We first present the experiences, thoughts, and feelings of youth and their caregivers in relation to educational pathways, after which we outline their recommendations for professionals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Code tree of all results, including experiences and recommendations, with references to the corresponding (sub)paragraphs.

3.1 Experiences, thoughts, and feelings of youth and their caregivers

Experiences, thoughts, and feelings of youth and their caregivers regarding the youth’s educational pathways were gathered through interviews. Following thematic analysis, four themes emerged from the data: (i) awareness of problems and their impact, (ii) the need for and a lack of perspective, (iii) the desire to be seen and heard (longing), and (iv) personal strengths and perceived support (resilience).

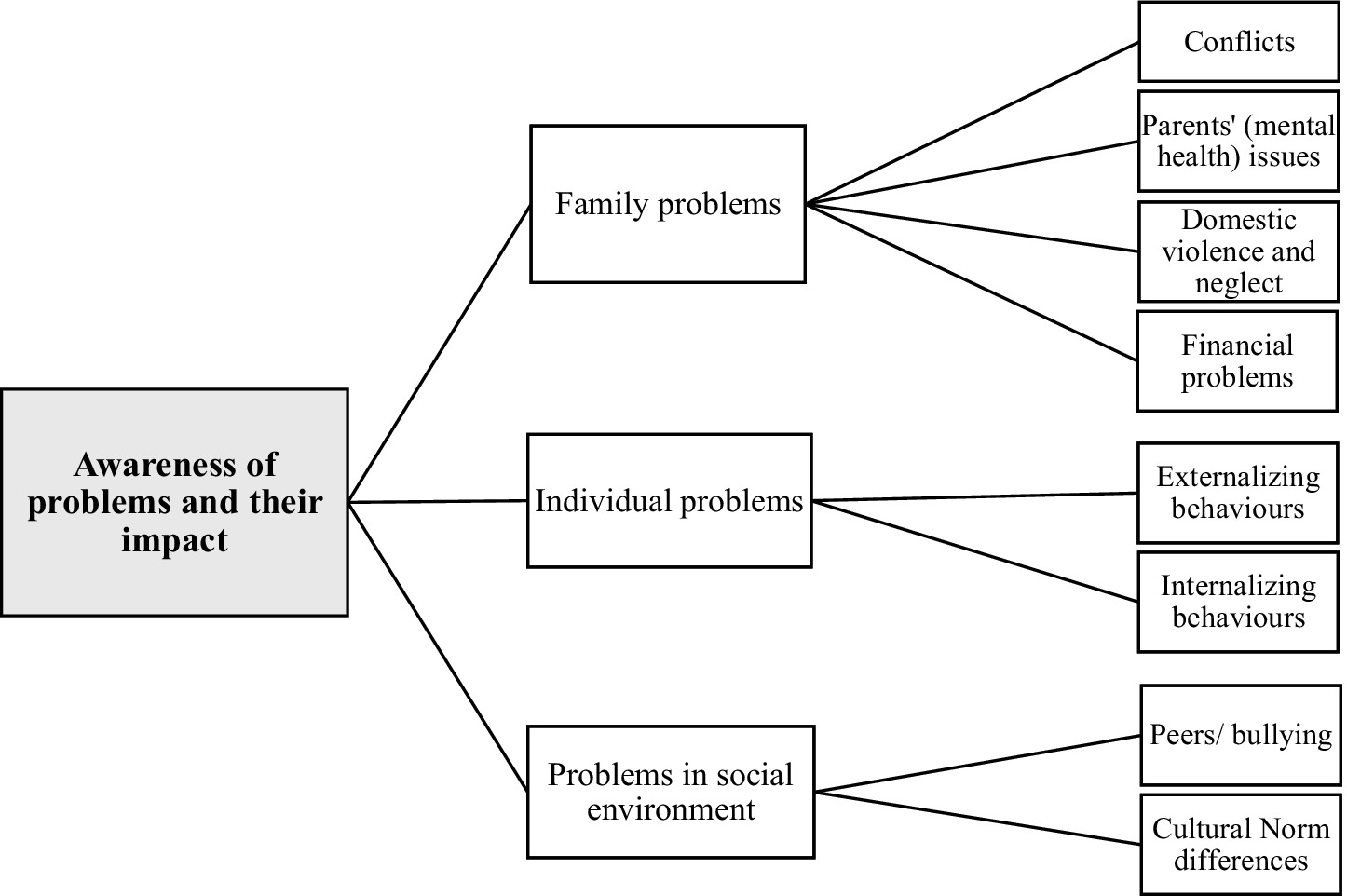

3.1.1 Awareness of problems and difficulties and their impact

Both youth and caregivers reported awareness of problems and difficulties within the family, as well as issues in their social environment that impeded the youth’s educational pathways (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Code tree of youth and caregivers’ experiences regarding awareness of problems and their impact.

Overall, the youth reported family problems during the interviews using sentences like ‘when it was not going well at home’ and ‘when I had problems at home.’ Youth and caregivers reported experiences of multiple adverse events in relation to their birth (and foster care) families. Reports mainly characterized conflicts and strained relationships between parents and between parents and youth. One quarter of youth reported direct experiences of neglect and witnessing domestic violence. Multiple youths reported experiences of their parents struggling with physical and mental health problems. Most of these experiences involved parents suffering from drug abuse or being involved in drug-related criminality. Lastly, some youth reported experiencing tension at home because of financial problems. Youth reflected on these experiences and mentioned the impact of these circumstances in relation to worrying and feelings of stress or indifference. This consequently impacted their educational pathways, like Alison (16-year-old) told during the interview:

My mother got diagnosed with breast cancer when I was in junior high school. As a result, I did not focus on my studies at all at school. I was preoccupied with other things. My mind was completely elsewhere, so school was not important to me at that time … I chose to help my mother because she went into debt because of my father after the divorce. My father left us with very bad debts … I tried to help my mother; however, at the age of 14, it is not easy to find a part-time job. So, I decided to make money the wrong way, and then I thought, at least I am helping my mom out this way. It is the wrong thought, I know, but for me, at that particular moment, I thought that maybe this was a good solution. After a while, I realized that what I did was not right.

Both youth and caregivers described the youth’s externalizing behavior problems, such as impulsivity, oppositional behavior, boundary-seeking behavior, drug abuse, and delinquent behaviors. These externalizing behaviors interrupted the youth’s school experiences, causing conflicts with peers and teachers, which led to suspension or expulsion from school. A majority of youth reflected on their externalizing behavioral problems as being the result of adversities they had encountered in their (early) lives, as mentioned by 20-year-old Tom:

Why I became aggressive: I was beaten, not just a slap, really beaten. That was just as it was, and then you carry that burden and take it with you, also outside of the house. Because you have this anger, but it is your father, you cannot hit him back. You are young; you cannot do anything. Then you want to express that anger elsewhere, which is why most young people are just angry. When you come to youth care, the staff may label you and they say: “This one has aggression problems; we are going to lock him up.”

Some youth and caregivers reported youth internalizing problems: depressive symptoms, anxiety, traumatic symptoms, and experiencing stress. These symptoms consequently led to difficulties in concentration and a lack of focus at school.

Finally, several youth and caregivers reported that the youth had experienced bullying, which left a deep impression on their educational pathway. A few youths and one caregiver emphasized the impact of cultural difference: being a minority in Western society made them feel out of place in school and care.

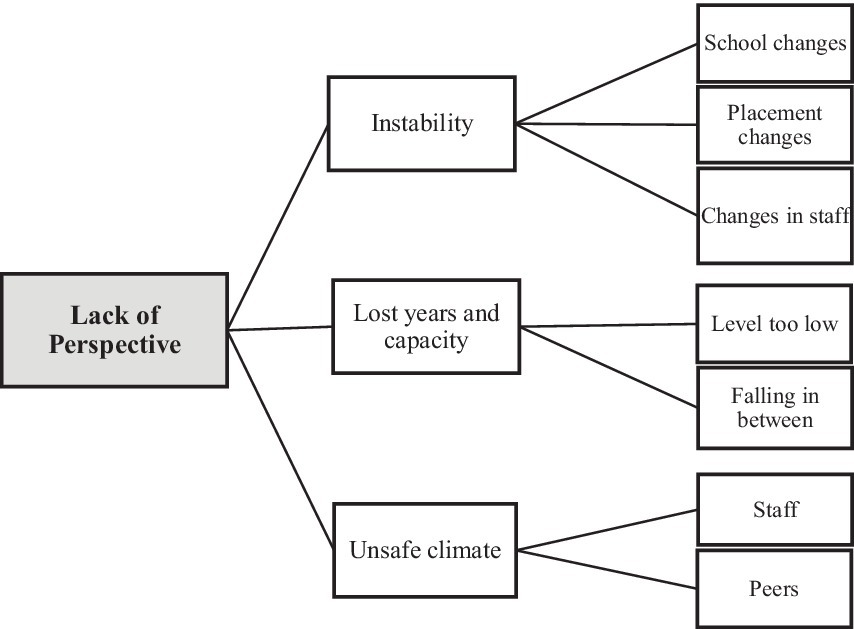

3.1.2 The need for and lack of perspective

The experience of being placed outside the home and its impact was mentioned by almost all youth and caregivers. They reported a need for and a lack of perspective while in care and special education settings, due to various aspects of instability, the experience of lost years, and an unsafe climate (see Figure 3 for code tree).

Youth and caregivers reported experiences of instability in the youth’s educational pathways. Youth experienced several placement changes and school changes and mentioned their impact, like the mother of Leo: “An out-of-home placement that is very intense for a six-year-old. So yes, you go to another school after, and there you all let it happen to you.” Placement changes and school changes went hand in hand. Some youth and caregivers reported school changes as a consequence of some youth and caregivers reported school changes as a consequence of unmet educational needs, primarily associated with behavioral challenges.

Furthermore, a majority of youth and caregivers reported numerous changes in staff both inside and outside RC. These changes were attributable not only to frequent placement and school transitions, but also to high staff turnover in youth care and special education settings. One father reported being involved with 104 different professionals, and one youth experienced 40 guardians in her life since the age of two. Some of these youth and caregivers mentioned the effect these changes had on their well-being, like 16-year-old Alison mentioned:

Um, well, then suddenly there was a guardian, she suddenly became my guardian. I didn’t know anything either then she said: “Yes, hi, I am your guardian.” So, I thought to myself, “Who are you, you know?” I’m pretty… yeah, actually a bitch when I’m angry, and when I don’t know what’s going on, I get really mean, very quickly.

And how these changes sometimes affected their educational pathways, as Beatrice reported:

“I have experienced now that when she (her teacher) is not here anymore, my school work is going more slowly … And I told Mary (the principal): You can’t leave now, I got attached to you, why are you leaving?”

Youth and caregivers alike experienced lost years of schooling and a loss of the youth’s abilities and talents. A frequently reported problem by youth and caregivers was that youth received education at a lower level than their abilities warranted. Some reported that the behavioral problems and/or the burden from familial problems stood in the way of obtaining a higher level. More frequently, youth experienced a lack of adequate academic level in residential settings. Youth with a higher educational level (preparing them for (applied) University) reported that there were no possibilities other than to follow a lower educational level. Some youth even reported that school was more like ‘a daytime activity’ in RC, and care was placed above schooling. Twenty-year-old Michelle stated:

The moment you enter an in-care situation, the total perspective is eliminated. You know, you’re already there because it is not going well, and then your school, for some youth, their only perspective, is being omitted at that moment; taken away from you. That really sucks. I really felt shitty about that.

Consequently, after leaving RC, youth often reported being demotivated to achieve a higher level or having to work ten times harder to return to their actual level, resulting in ‘lost years.’ These ‘lost years’ were also a consequence of ‘falling in between’ as a result of the placement changes. The transition from one school to another often got delayed due to problems finding a suitable school or having to wait for the new academic year to start.

Half of the youth and caregivers described the repressive and unsafe climate in care and schools. Some youths reported a repressive climate characterized by numerous rules imposed by teachers and residential staff. Other youth reported the unpredictability of the staff, particularly when they fixated on fellow peers or classmates. Moreover, youth reported different problems in which they were negatively influenced by their peers, for example, by observing aggressive classmates (who got fixated), ongoing turmoil in care groups and classrooms, fights in school, and (secret) drug use. Justin, 16 years old, for example, told the interviewer:

It was really chaotic in the RC group lately. Really bad, but just nights along; set off fire alarms, kicking in doors, smashing windows. It is really fuck*d up if you go through this every night, with the consequence I had to skip school for a week because of all this.

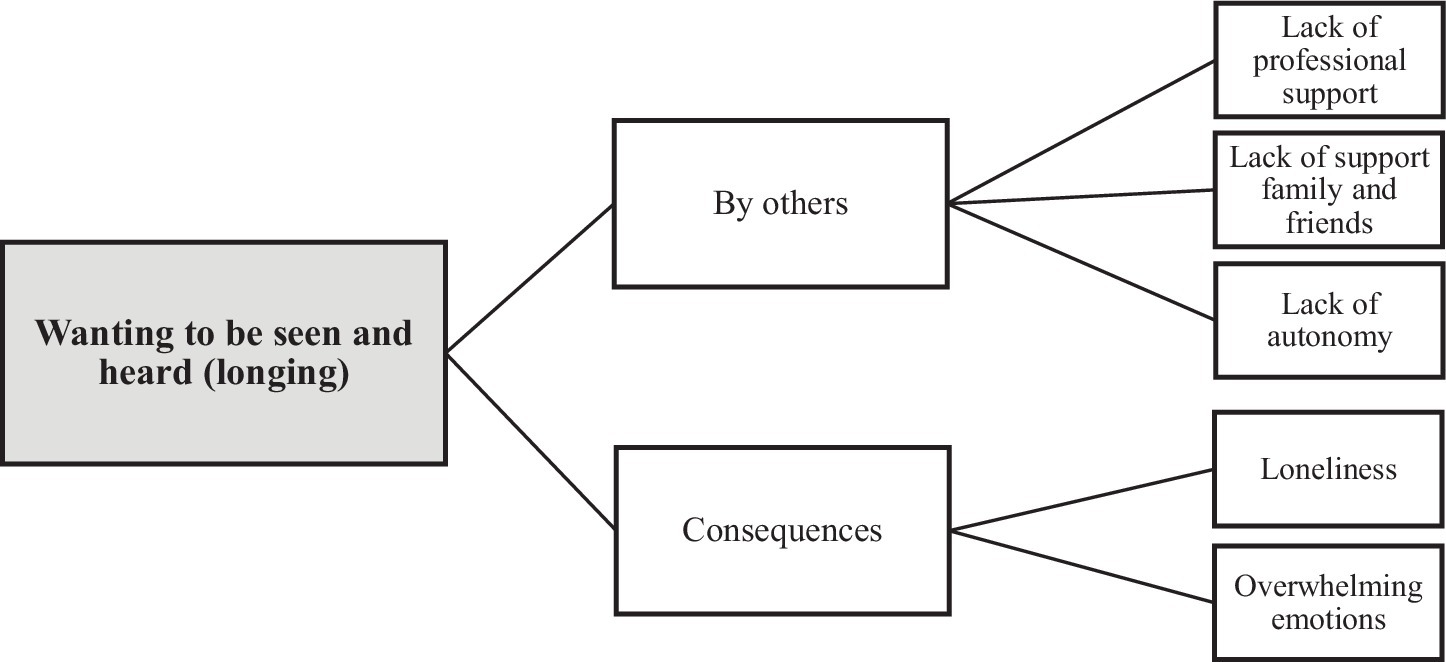

3.1.3 Longing: wanting to be seen and heard

Both youth and their caregivers reported a desire to be seen and heard by others. Moreover, they reported feelings of a lack of autonomy in youth’s educational pathways and a lack of support. Consequently, the problems youth faced, the lack of perspective and feelings not being seen and heard, led to further feelings of loneliness and overwhelming feelings such as anxiety, anger, and sadness (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Code tree of youth and caregivers’ experiences regarding wanting to be seen and heard (longing).

A major theme was the lack of autonomy while in care and special education. Almost all youth and caregivers reported youth not being heard in their educational trajectories. “Yes, all the teachers were talking about me in a kind of conference room, whether I could go to another school, yes or no. I was very tense because all the teachers were talking about me.” (Eddie, age unknown).

Almost all youth reported experiences of a lack of support from professionals in both care and education, in which they did not feel supported, did not feel seen and acknowledged, and did not feel trusted. All caregivers reported a lack of communication or cooperation with professionals in both care settings and schools, with this issue being particularly evident in school settings. Some caregivers reported how that made them feel left out. Moreover, half of the caregivers reported dealing with feeling stigmatized for out-of-home placement by institutions or their social network. Caregivers reported feelings of failure, shame, and guilt toward their role as a parent.

A couple of youth and caregivers reported that they had to tell their story to professionals over and over again, and that professionals only read the files, which made both youth and caregivers feel uncomfortable, mainly because of feeling stigmatized. Furthermore, a lack of communication between care and school settings also resulted in professionals being unaware of the background and circumstances of youth. For example, the grandmother (primary caregiver) of Jennifer reported on an incident in which the school teachers in the RC setting were not aware of Jennifer’s sexual trauma:

And for every child that is being placed here, take a look at what happened to them; look in their files. And see how you can all handle this. … Now she is all upset, and it all happens again … (inaudible). Because she is getting angry now, no one can help her. Only me. She called me immediately and told me: “We have to talk right now. Grandma, I am so, so sad. I just want to destroy the whole school right now...”.

A majority of youth and caregivers reported feelings of loneliness or not being seen. Youth often did not feel supported by friends or family. This loneliness often led youth and caregivers to ‘deal’ and ‘struggle’ with even more stress and emotions such as sadness, anger, anxiety, or indifference, like 21-year-old Amanda stated: “Because if youth are feeling alone or abandoned. Then they really go off the rails. I speak a little bit from experience here, too.”

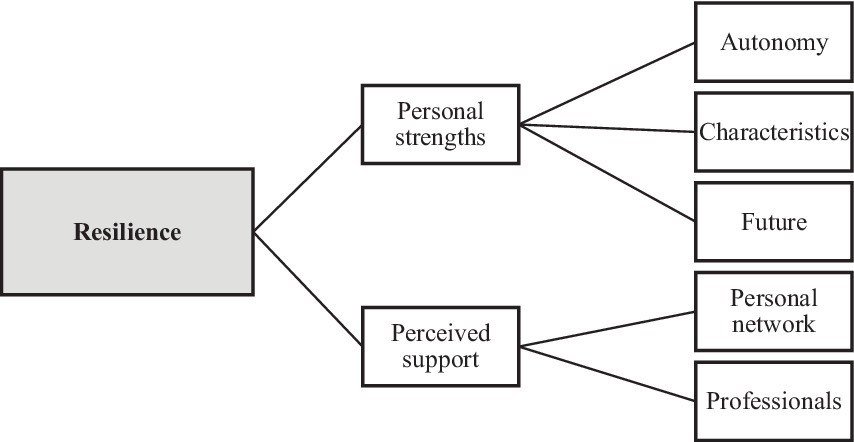

3.1.4 Resilience

Despite the adversity and difficulties, a prominent theme in the experiences of youth and caregivers is their resilience. Youth and caregivers reported personal strengths and perceived support that helped them deal with the difficulties they faced (Figure 5).

Youth reported several personal strengths. Youth took control over their situation, set goals, made decisions themselves, and, if possible, had the desire to do it themselves. Moreover, youth and caregivers reported various characteristics that helped them cope with the problems they faced. Youth reported being self-reflective and self-aware, willing to talk about their problems, possessing self-discipline, being a ‘go-getter,’ and having the will to help others. These strengths helped them in some cases to view earlier experiences from a different perspective, change their own mindset or behavior, and gain confidence.

More than half of the caregivers reported feelings of doubt and reflecting on thoughts, considering pushing or stimulating their children, and making decisions regarding their educational pathways, versus supporting their children’s autonomy. All caregivers also reported taking the lead and initiative to contact schools, engaging in conversations with teachers, and other professionals.

Both youth and caregivers reported the youth’s interests, ideas, or wishes regarding further education or professions, which made them willing to graduate and obtain a diploma. Olivia, 16 years old, said: “Ehm… since I was eight years old. I’ve wanted my own breakfast/lunch café. In later life, just all by myself…. School was a huge motivator…(…). Because I want my own lunch café so badly.”

Both youth and caregivers reported experiences of perceived support from their professional and personal networks. The majority of youth and caregivers indicated that they had received some form of support from a professional working in the field of care or education support in which they felt seen, understood, and trusted. Notably, this usually concerned one person who was of value to them and made a difference, such as a teacher, principal, internal supervisor, guardian, or therapist.

Some youth reported the help of their personal networks, which helped them during their educational pathways. Although few of them reported help from their parents, since contact was absent or fraught, more (but not all) youth reported support from a family member or friends. Tobias, 21 years old, mentioned how the support of his grandfather helped him:

Yes, my grandfather, who used to motivate me and argue with my guardian about “Why is that boy doing that academic level instead of the recommended level?” He did motivate me a lot to get the best out of myself.

3.2 Recommendations for professionals by youth and caregivers

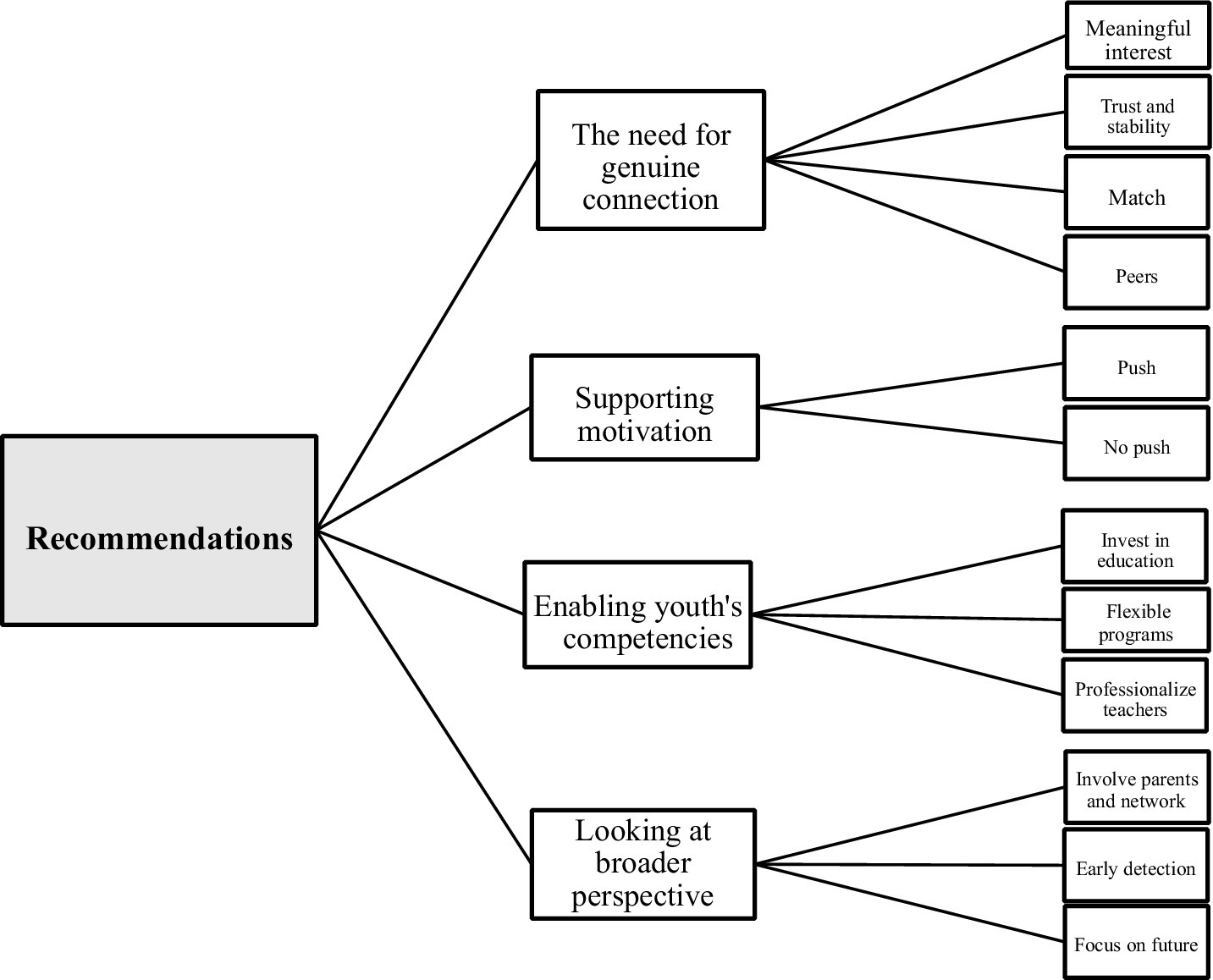

Both youth and caregivers reported recommendations for professionals concerning the importance of genuine connection, supporting youth’s motivation, enabling youth’s competencies, and looking at the young person from a broader perspective (see Figure 6).

3.2.1 Genuine connection

All youth and caregivers reported receiving multiple pieces of advice from professionals regarding the importance of genuine connection. Most recommendations focused on showing meaningful interest, fostering trusting and stable relationships, leveling with youth, and paying attention to peer relationships.

The majority of both youth and caregivers underscored the importance of professionals demonstrating a meaningful interest in youth, actively listening to them, and seeking to understand the individual beyond the behaviors they exhibit, as Michelle (20 years old) stated:

There is also an internal supervisor at school, for example, who understands the broader issues and can support the teachers with them. This person can also talk to pupils, saying things like, “Hey, what’s the matter?” (…) “Why aren’t you listening? What’s the reason? Why are you doing this?”

A majority of the youth and caregivers reported that the youth needed someone they can trust completely to prevent them from feeling left alone. Some youth and caregivers emphasized the importance of stability in these relations, especially across changes in school or residence. They wanted to have one person they can always go to.

A few youths stated that a good match between youth and professionals is needed to build a sense of relatedness. For some youth, it is essential that professionals connect with them, for example, by ‘talking to them in their own language’ and using clear communication (do what you say). Not only do a few young people need to feel a sense of relatedness with professionals, but peer relationships are also important to them. Therefore, some youth advised professionals to take more action against bullying and drug use.

3.2.2 Supporting motivation: to push or not to push

Youth differ in their recommendations regarding the extent to which they think youth need a little push to stay motivated for schoolwork. Some youth emphasized that they did not want to be pushed, as Bill (16 years old) mentioned:

If they tell you to do this and that, I am not going to do that. I will get angry that they shouldn't be so focused on authority, being strict, and all that. I cannot handle that, and I think many other youths in here cannot either. Just needed a conversation. They should have just talked to me.

Other youth and a few caregivers thought that youth need a little push to get motivated:

They need that little push, because, you know, I get it myself. Maybe they’re smoking weed, everything feels too much, applying for jobs is just overwhelming. But if someone says, “Hey, you know what, I’ll go with you, I’ll help you make a CV, I’ll help you find work,” then they actually get motivated, you know? (Tom, 20 years old).

3.2.3 Enabling youth’s competencies

Some youth and caregivers recommended investing in sufficient education, personalized programs, and professionalizing teachers by focusing on improving knowledge in mental health care. Youth reported the importance of offering education that matches their level, including accessible professional teachers at all levels. Furthermore, they recommended prioritizing education alongside care, so that youth can access further training or programs later on.

I think that if you are in an institution, you do have just to make sure that children can get enough education to still be at the same level they were at, because otherwise, later, when you leave there at the age of 18, for example, they probably won’t accept you anymore.

Moreover, one youth and a few caregivers emphasized the importance of individualized and flexible programs in which learning, adjustments to match individual needs, and focusing on the child’s strengths can help meet the youth’s competencies.

3.2.4 Looking at a broader perspective

Caregivers’ (not youth) recommendations for professionals focus on the involvement of parents and the network of youth, also during the time the child does not live at home. According to caregivers, professionals have to invest in communicating with them, keep them up to date, and genuinely collaborate with them. As the mother of Sean mentioned:

To look at the extent to which a parent can still help. Because eventually, when a child has to go back into society, he will have to rely on me again. So, I expect them to guide me throughout the entire process.

Furthermore, caregivers (and one youth) emphasized the importance of school in focusing on the future of youth to motivate them in their schoolwork. Caregivers also recommended that schools/institutions could be a place for earlier detection of problems, so larger problems in the future could be prevented, for example, by detecting deviant behavior at primary school age, as the father of Oliver mentioned:

Besides the family, a child spends most of their time at school. So if kids, if teachers see that a child is different, that really deserves attention from the neighborhood teams. From youth care. So you have to make that shift from an institution that just takes in kids when things have gone wrong, to being at the front line in the neighborhood, at that school, where you can actually notice kids. And then maybe special education or a special class.

4 Discussion

The aims of this participatory qualitative study were to (1) examine the experiences of youth and caregivers regarding youth’s educational pathways in RC and (2) gather their recommendations for improvement. The experiences of youth and caregivers consisted of four main themes: awareness of problems and difficulties and their impact, the need for and lack of perspective, wanting to be seen and heard (longing), and personal strengths and perceived support (resilience). Youth and caregivers recommended that professionals truly see and hear them by emphasizing the importance of genuine connection, exploring ways to support youth to stay motivated, enabling youth competencies, and taking a broader perspective.

4.1 Findings and implications for practice and research

One of the noteworthy results was the majority of youth and caregivers reporting the youth’s adverse early childhood experiences and how these often resulted in feelings of anger, aggression, and impulsivity. Furthermore, the youth explained that professionals mostly responded to their observable behaviors, while the underlying causes of that behavior and other accompanying feelings remained unrecognized. As a result, many youths reported that they did not receive the support they required and consequently felt unseen and alone, which led to further feelings of helplessness and anger. Furthermore, both school and RC were often perceived by the youth in the present study as unstable and unsafe environments. This finding contrasts with previous research on foster and kinship care youth, which has shown that school can serve as a haven and offer stability amidst the chaos and unpredictability of their home lives (Townsend et al., 2020). The adverse childhood experiences of youth in the present study, combined with these enduring challenges in care and schools, contribute to the evidence of risk for retraumatization among youth in RC (Ames and Loebach, 2023; Bramsen et al., 2021; De Valk et al., 2017). Youth’s experiences described in this study contribute to a more nuanced appreciation for what has previously been labeled the “difficult profile” (e.g., behavioral problems) of youth in RC (Cheung et al., 2012; Leloux-Opmeer et al., 2016; Montserrat and Casas, 2018). The narratives in the present study invite a shift in perspective: from viewing youth through the lens of their “problems” to understanding who they are, what they have lived through, and what they need to feel safe, supported, and motivated. Although it is widely acknowledged that many youth in the RC system have a history of long-lasting and complex trauma, which affects both emotion regulation (Hummer et al., 2010; Ko et al., 2008) and learning (Teicher et al., 2003), the experiences of youth and caregivers in our study suggest that this knowledge is still insufficiently recognized and applied in residential and (special) educational settings.

The feelings of not being seen were often intensified by the limited influence youth had over decisions impacting their lives, reflecting a broader lack of autonomy. Regarding the recommendation that professionals should offer youth more encouragement or a push to help them motivate for school, the youth’s opinions were divided. A crucial nuance, however, emerges from participants’ narratives: rather than acting from a position of authority, professionals are encouraged to work with youth exploring educational options together, assisting with job applications, or supporting them in completing homework, rather than directing such actions at them. These findings are consistent with self-determination theory, which posits that promoting autonomous motivation involves encouraging youth while ensuring that they feel seen, heard, and meaningfully involved in the activity (Ryan and Deci, 2017). In contrast, offering a ‘push’ without acknowledging the young person’s perspective may result in controlled motivation or even amotivation. The varying responses of youth to such encouragement can therefore be understood in light of the environment’s sensitivity to their psychological needs (Van der Helm et al., 2018). Previous research on teachers’ voices in RC settings further suggests that, despite teachers’ commitment to this population, many professionals struggle to effectively address the emotional and behavioral needs of children in RC (Morales-Ocaña and Pérez-García, 2020).

Another key finding concerns the substantial number of recommendations made by both youth and caregivers, underscoring the critical role of professionals in fostering genuine and attuned connections with youth in RC. In order to feel seen and heard, both groups emphasize the importance of professionals demonstrating genuine interest, dedicating one-on-one time, and investing in the development of trusting and stable relationships. Furthermore, their experiences illustrate that even a single individual, whether from their personal network or a professional context, can have a significant impact through seemingly small gestures, such as showing sincere interest or simply checking in on how they are doing. These findings align closely with principles of trauma-informed care, which emphasize safety, trustworthiness, and relational connection as foundational to effective support for individuals with histories of trauma (Bath, 2008).

However, building positive relationships with youth with traumatic and adverse backgrounds can be challenging for professionals. These youths’ early childhood relationships, often characterized by emotional insecurity, can form a blueprint for relationships later in life: dysfunctional beliefs about self, others, and the world, and an overreactive stress system take hold, resulting in disorganized emotional and behavioral problems in the classroom (Brunzell et al., 2016). In order to meet the needs of youth in RC, training in a trauma-informed approach for professionals in schools and residential care is urgently needed. A trauma-informed approach emphasizes the importance of knowledge and awareness among professionals about the impact of adverse childhood experiences and their consequences on (brain) development, health, learning, and behavioral problems. This knowledge and awareness can help professionals engage in a calmer, warmer, and more empathic manner, putting into words the stress and emotions underlying the youth’s behavior (Bryson et al., 2017), which has also been suggested in previous research as important for building a strong professional–youth alliance in RC (Roest, 2022). Specifically for educational settings, research into the effects of trauma-informed approaches is scarce. We need further research into its effects on changes in teachers’ perspectives and the relationships between school, students, and families (Avery et al., 2021).

In light of these relationships between professionals, students, and families, the perspectives of caregivers in the present study offer further insight into the theme of relational support. Caregivers in our study frequently reported feeling excluded from meaningful collaboration, especially in educational settings, despite a strong desire and capacity to support their children. Their experiences suggest that they take too long to be seen, heard, and acknowledged in their caregiving roles. This is particularly relevant given the many transitions youth experience while in care, such as changes in placement, school, and professionals, where involving a consistent adult figure can offer much-needed continuity. Whether a parent, grandparent, or mentor, these figures often made a crucial difference in the lives of youth, as described by the experiences of youth in this study. In trauma-informed care, recognizing the importance of these consistent, supportive figures is essential, as they can help bridge the gap between youth and professionals, providing a sense of stability and emotional security. Actively involving caregivers and trusted network figures should therefore be seen as a vital component of supportive, youth-centered educational pathways.

A final implication for practice and policy in the present study is the importance of recognizing and enabling youth’s competencies in RC. The findings of this study reveal that the educational pathways of these youth are frequently marked by instability, including repeated placement changes and interruptions, which contribute to a substantial loss of instructional time. Moreover, the educational facilities within RC often fail to meet the academic level and developmental needs of the youth. To restore a sense of perspective and future orientation, it is essential to acknowledge the critical role of education during residential placement. This includes creating opportunities that enable youth to engage in learning environments aligned with their abilities and interests. Ensuring access to appropriate, high-quality education within residential settings is therefore a fundamental step toward helping youth stay on track and realize their full potential.

4.2 Limitations and strengths

The major strength of this study lies in its participatory approach, which amplifies the voices of youth and caregivers to gain deeper insight into their educational experiences. Using a PAR design, researchers worked together with youth with lived experience—and occasionally caregivers—as co-researchers, fostering democratic participation, respect, and collective action to examine the challenges faced by youth in RC and their caregivers. An expert panel of caregivers contributed early on by co-developing recruitment materials and later reviewing the final code tree, ensuring their perspectives were meaningfully integrated. Youth with lived experience, involved as core members of the SOT Consortium from the project’s outset, worked closely with researchers to shape the study design, developed interview questions, and collaboratively coded and interpreted the data. This collaboration was intentionally guided by critical PAR frameworks (Fine, 2018; International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research [ICPHR], 2013) and informed by lessons from previous PAR (Van Vliet, 2020), ensuring that youth voices remained central throughout.

It should be noted that the present study is not without limitations. Firstly, the interviews were conducted by multiple young students with limited experience in this field. To mitigate these potential risks, students received training and supervision from experienced interviewers, followed by a quality check that was performed afterwards (Moerman, 2014). Furthermore, due to COVID-19, some interviews were conducted online (via Teams), which may have made building rapport with youth more difficult. However, the distance of online interviewing and participating from a private location can be beneficial when discussing difficult topics (Donison et al., 2023).

Another limitation in our study involved the use of convenience sampling to recruit both young people and their caregivers. Although convenience sampling may introduce bias and limit the generalizability of findings, in qualitative research, such approaches are often justified as they enable the collection of rich, in-depth data from information-rich cases (Jager et al., 2017). Furthermore, the active involvement of youth with lived experience in the recruitment process potentially reduced participation barriers and fostered trust among potential participants. Combined with participant recruitment across seven diverse youth care and educational organizations in a highly heterogeneous urban region of the Netherlands, this approach enabled the inclusion of a diverse sample with a range of residential and educational experiences.

The recruitment of caregivers proved to be a challenging process. Caregivers were at first invited by an information letter distributed by participating youth, resulting in only one caregiver participant. At a later date, caregivers were recruited by the head of a caregiver experience experts council. Their voices, although important to be heard, may not be representative of the wider group of caregivers who are difficult to reach. Moreover, we also noted that among youth in our study, there were multiple reports of a background of familial problems such as maltreatment or neglect, often due to parental psychiatric problems. The voice of these parents may be underrepresented.

5 Conclusion

This participatory qualitative study highlights the challenges that youth in RC and their caregivers face in educational pathways. Findings emphasize the role of early adverse experiences in shaping unaddressed behavioral and emotional difficulties, leading to feelings of being unseen and unsupported. The experiences of youth in the present study call for trauma-informed, relational approaches that foster autonomy and emotional safety, beyond behavior management.

Furthermore, educational systems in RC and the schools that youth attend throughout their educational pathways should provide continuity, individualized support, and opportunities, enabling them to maintain a sense of purpose and future orientation. Results imply that professionals should co-create these trajectories with youth, fostering autonomy and active engagement rather than compliance. Moreover, involving caregivers or trusted network figures is essential for feelings of continuity and stability. Both youth and caregivers emphasize the importance of trusting, attuned relationships with professionals. However, establishing these connections is challenging in emotionally dysregulated environments, underscoring the need for trauma-informed training for professionals in both care and educational settings.

Overall, the study advocates for systemic change that combines trauma-informed and youth-centered approaches, with future research exploring the impact on educational outcomes for youth in RC.

Data availability statement

The (raw) datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to ethical and privacy considerations. The anonymized datasets that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Erasmus University DPECS Research Ethics Review Committee (approval no. 20-062). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. All participants (youth aged 12–21 and caregivers) provided informed consent prior to enrollment in the study, with parental or guardian consent additionally obtained for youth under 16.

Group members of stay on track consortium

The Stay on Track consortium, part of Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences (Research Centre Urban Talent), is a core team of lecturer–researchers and youth with lived experience, supervised by Professor Dr. Frans Spierings (lector), which led the four-year Stay on Track project. Dr. Inge Bramsen, a senior researcher and initiator, served as the first-phase project leader, and Dr. Szabinka Dudevszky, a researcher and senior lecturer involved from the start, later served as project leader in subsequent phases of the project.

Author contributions

KB: Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft. CK: Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. IB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. AP: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. FC: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation. AH: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SD: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by ZonMw, The Netherlands, under the Stay on Track project (grant no. 10190022010016).

Acknowledgments

First, we sincerely thank four youth with lived experience of the Stay on Track consortium for their contributions in the first phase of the Stay on Track project: Yorrick Klinger, Yasmin Rustom, Yorrick van der Ent, and Sulyvienne Ersilia. Moreover, we thank all youth and caregivers for sharing their stories, making this study possible. Furthermore, we thank all students of Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences who contributed to the data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative artificial intelligence (ChatGPT-4o, OpenAI, 2025) was used in the preparation of this manuscript solely to improve the clarity and fluency of language in accordance with academic English standards. The authors reviewed and verified AI-assisted outputs to ensure accuracy and appropriateness.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ames, R. L., and Loebach, J. E. (2023). Applying trauma-informed design principles to therapeutic residential care facilities to reduce retraumatization and promote resiliency among youth in care. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 16, 805–817. doi: 10.1007/s40653-023-00528-y

Avery, J. C., Morris, H., Galvin, E., Misso, M., Savaglio, M., and Skouteris, H. (2021). Systematic review of school-wide trauma-informed approaches. J. Child Adol. Trauma 14, 381–397. doi: 10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1

Barth, R. P. (2002). Institutions vs. foster homes: The empirical base for the second century of debate. Chapel Hill, NC: Annie E. Casey Foundation, University of North Carolina, School of Social Work, Jordan Institute for Families.

Bath, H. (2008). The three pillars of trauma-informed care. Reclaiming Child. Youth 17, 17–21. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

Bramsen, I., Kuiper, C., Willemse, K., and Cardol, M. (2019). My path towards living on my own: voices of youth leaving Dutch secure residential care. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 36, 365–380. doi: 10.1007/s10560-018-0564-2

Bramsen, I., Kuiper, C., Willemse, K., and Cardol, M. (2021). The creation of my path: a method to strengthen relational autonomy for youth with complex needs. JAYS 4, 31–50. doi: 10.1007/s43151-020-00029-x

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2016). Trauma-informed positive education: using positive psychology to strengthen vulnerable students. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 20, 63–83. doi: 10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x

Bryson, S. A., Gauvin, E., Jamieson, A., Rathgeber, M., Faulkner-Gibson, L., Bell, S., et al. (2017). What are effective strategies for implementing trauma‑informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Syst. 11, Article 36:36. doi: 10.1186/s13033-017-0137-3

Cheung, C., Lwin, K., and Jenkins, J. M. (2012). Helping youth in care succeed: influence of caregiver involvement on academic achievement. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.033

Corbin, J. M., and Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 13, 3–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00988593

de Beer, C. R. M., Nooteboom, L. A., van Domburgh, L., de Vreugd, M., Schoones, J. W., and Vermeiren, R. R. J. M. (2024). A systematic review exploring youth peer support for young people with mental health problems. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 33, 2471–2484. doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-02120-5

De Swart, J. J. W., Van den Broek, H., Stams, G. J. J. M., Asscher, J. J., Van der Laan, P. H., Holsbrink-Engels, G. A., et al. (2012). The effectiveness of institutional youth care over the past three decades: a meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1818–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.05.015

de Valk, S., Kuiper, C., Van der Helm, G. H. P., Maas, A. J. J. A., and Stams, G. J. J. M. (2017). Repression in residential youth care: a qualitative study examining the experiences of adolescents in open, secure and forensic institutions. J. Adolesc. Res. 34, 757–782. doi: 10.1177/0743558417719188

Dill, K., Flynn, R. J., Hollingshead, M., and Fernandes, A. (2012). Improving the educational achievement of young people in out-of-home care. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 34, 1081–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.031

Donison, L., Raby, R., Waboso, N., Sheppard, L. C., Grossman, K., Harding, E., et al. (2023). ‘I’m going to call my friend to join us’: connections and challenges in online video interviews with children during COVID-19. Child. Geogr. 22, 134–148. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2023.2253176

Fine, M. (2018). Just research in contentious times: Widening the methodological imagination. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gao, M., Brännström, L., and Almquist, Y. B. (2017). Exposure to out-of-home care in childhood and adult all-cause mortality: a cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, dyw295–dyw1017. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw295

Garcia-Molsosa, M., Collet-Sabé, J., and Montserrat, C. (2021). What are the factors influencing the school functioning of children in residential care: a systematic review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 120:105740. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105740

Hanson, M. J., Horn, E., Sandall, S., Beckman, P., Morgan, M., Marquart, J., et al. (2001). After preschool inclusion: children’s educational pathways over the early school years. Except. Child. 68, 65–83. doi: 10.1177/001440290106800104

Harder, A. T., Huyghen, A. N., Knot-Dickscheit, J., Kalverboer, M. E., Köngeter, S., Zeller, M., et al. (2014). Education secured? The school performance of adolescents in secure residential youth care. Child Youth Care Forum 43, 251–268. doi: 10.1007/s10566-013-9232-z

Herbers, J. E., Reynolds, A. J., and Chen, C. (2013). School mobility and developmental outcomes in young adulthood. Dev. Psychopathol. 25, 501–515. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001204

Holland, S. (2009). Listening to children in care: a review of methodological and theoretical approaches to understanding looked after children’s perspectives. Child. Soc. 23, 226–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00213.x

Huefner, J. C., James, S., Ringle, J., Thompson, R. W., and Daly, D. L. (2010). Patterns of movement for youth within an integrated continuum of residential services. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 32, 857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.02.005

Hummer, V. L., Dollard, N., Robst, J., and Armstrong, M. I. (2010). Innovations in implementation of trauma-informed care practices in youth residential treatment: a curriculum for organizational change. Child Welfare 89, 79–95.

International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research [ICPHR] (2013). Position paper 1: What is participatory Health Research? Version: Mai 2013. Berlin: International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research.

Jager, J., Putnick, D. L., and Bornstein, M. H. (2017). More than just convenient: the scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 82, 13–30. doi: 10.1111/mono.12296

Kim, J. (2016). Youth involvement in participatory action research (PAR): challenges and barriers. Crit. Soc. Work 17, 38–53. doi: 10.22329/csw.v17i1.5891

Ko, S., Ford, J., Kassam-Adams, N., Berkowitz, S. J., Wilson, C., Wong, M., et al. (2008). Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 39, 396–404. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.4.396

Lagerlöf, H. (2016). School related resources and potential to exercise self-determination for young people in Swedish out-of-home care. Adoption Fostering 40, 378–391. doi: 10.1177/0308575916647660

LeBel, J., Huckshorn, K. A., and Caldwell, B. (2010). Restraint use in residential programs: why are best practices ignored? Child Welfare 89, 169–187

Leloux-Opmeer, H., Kuiper, C., Swaab, H., and Scholte, E. (2016). Characteristics of children in foster care, family-style group care, and residential care: a scoping review. J. Child Fam. Stud. 25, 2357–2371. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0418-5

Marion, E., and Mann-Feder, V. (2020). Supporting the educational attainment of youth in residential care: from issues to controversies. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 113:104969. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104969

Marion, E., and Tchuindibi, L. (2024). The educational experience of young people in residential care through the lens of learning careers. Br. Educ. Res. J. 50, 545–562. doi: 10.1002/berj.3922

Moerman, G. (2014). Probing behaviour in open interviews: a field experiment on the effects of probing tactics on quality and content of the received information. Netherlands: Vrije Universiteit.

Montserrat, C., and Casas, F. (2018). The education of children and adolescents in out-of-home care: a problem or an opportunity? Results of a longitudinal study. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 21, 750–763. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2017.1318832

Morales-Ocaña, A., and Pérez-García, P. (2020). Children living in residential care from teachers’ voices. Eur. J. Soc. Work. 23, 658–671. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2018.1532956

Nijhof, G. (2000). Life stories: the method of autobiographical research in sociology. [Levensverhalen: de methode van autobiografisch onderzoek in de sociologie]. Amsterdam: Boom.

O’Higgins, A., Sebba, J., and Gardner, F. (2017). What are the factors associated with educational achievement for children in kinship or foster care: a systematic review. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 79, 198–220. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.004

Ozawa, E., and Hirata, Y. (2019). High school dropout rates of Japanese youth in residential care: an examination of major risk factors. Behav. Sci. 10:19. doi: 10.3390/bs10010019

Roest, J. J. (2022). The therapeutic alliance in child and adolescent psychotherapy and residential youth care. Doctoral dissertation. University of Amsterdam.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. doi: 10.1521/978.14625/28806

Sacker, A., Lacey, R. E., Maughan, B., and Murray, E. T. (2022). Out-of-home care in childhood and socio-economic functioning in adulthood: ONS longitudinal study 1971–2011. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 132:106300. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106300

Stein, M. (2012). Young people leaving care: Supporting pathways to adulthood. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Teicher, M., Andersen, S., Polcari, A., Anderson, C. M., Navalta, C. P., and Kim, D. M. (2003). The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 27, 33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00007-1

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., and Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Townsend, I. M., Berger, E. P., and Reupert, A. E. (2020). Systematic review of the educational experiences of children in care: children’s perspectives. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 111:104835. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104835

Trout, A. L., Hagaman, J., Casey, K., Reid, R., and Epstein, M. H. (2008). The academic status of children and youth in out-of-home care: a review of the literature. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 30, 979–994. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.11.019

Tufford, L., and Newman, P. (2012). Bracketing in qualitative research. Qual. Soc. Work. 11, 80–96. doi: 10.1177/1473325010368316

Van der Helm, G. H. P., Kuiper, C. H. Z., and Stams, G. J. J. M. (2018). Group climate and treatment motivation in secure residential and forensic youth care from the perspective of self determination theory. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 93, 339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.028

Van Staa, A., and Evers, J. (2010). 'Thick analysis': a strategy to enhance the quality of qualitative data analysis. ['thick analysis': strategie om de kwaliteit van kwalitatieve data-analyse te verhogen]. KWALON 43:2. doi: 10.5117/2010.015.001.002

Van Vliet, J. (2020) in Pioneers: lessons learned. Participatory action research with psychologically vulnerable youth. [Koplopers: Lessons learned. Participatief actieonderzoek met psychisch kwetsbare jongeren]. eds. F. Spierings and S. Dudevszky (Rotterdam: Rotterdam University of Applied Science).

Keywords: youth, education, residential care, experiences, participatory action research

Citation: Bruidegom K, Kuiper C, Bramsen I, De Pooter A, Collet F, Dudevszky S and Harder A (2025) “They should have just talked to me”: educational pathways of youth in residential care – a participatory action research study. Front. Educ. 10:1667432. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1667432

Edited by:

Weifeng Han, Flinders University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Sam Redgate, Northumbria University, United KingdomVanessa Fournier, Centre de Recherche Universitaire pour les Jeunes et les Familles, Canada

Copyright © 2025 Bruidegom, Kuiper, Bramsen, De Pooter, Collet, Dudevszky and Harder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kiki Bruidegom, a2lraS5icnVpZGVnb21AaWh1Yi5ubA==

†ORCID: Kiki Bruidegom, orcid.org/0009-0005-0570-0852

Chris Kuiper, orcid.org/0000-0002-6650-6288

Inge Bramsen, orcid.org/0000-0002-5044-6153

Szabinka Dudevszky, orcid.org/0009-0004-7290-8680

Annemiek Harder, orcid.org/0000-0002-3809-9427

Kiki Bruidegom

Kiki Bruidegom Chris Kuiper2,3†

Chris Kuiper2,3† Annemiek Harder

Annemiek Harder