- 1School of Education, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, United States

- 2Kinder Institute, Rice University, Houston, TX, United States

- 3UnityPoint Health, West Des Moines, IA, United States

This paper introduces a framework aimed at designing equity-centered boundary infrastructure that supports learning at the intersection of research and practice. Drawing on sociocultural learning theory and influenced by a multi-district equity initiative, the framework outlines four interconnected design principles: contextual responsiveness, disruption of power dynamics, support for transformational learning, and attention to enactment. To demonstrate the framework’s application, we focus on the redesign of a traditional research tool, the research brief, reimagining it to foster transformational learning and support systems change. We conclude by exploring the implications of this framework for the design and study of boundary infrastructure.

1 Introduction

Recent calls for educational transformation have emphasized the need to reconsider how research and practice knowledge contribute to equitable educational ecosystems (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2022). While collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and communities holds great promise for advancing these goals (Ishimaru, 2019), these efforts require more than goodwill or shared goals. They require intentional structures, routines, and tools that support sustained learning across cultural, organizational, and epistemological boundaries (Farrell et al., 2022; Akkerman et al., 2021). We refer to these elements as boundary infrastructure: the tools (e.g., artifacts, protocols), practices (e.g., collaborative routines), and roles that enable meaningful engagement across different sites of practice (Bohannon et al., 2025; Chen, 2024; Dreier, 2008, 2009; Penuel, 2019; Wenger, 2000).

However, boundary infrastructure is not always designed or enacted in ways that challenge existing hierarchies or exclusionary practices. Even in collaborations normatively focused on learning or systems change, structures can default to dominant norms about whose knowledge counts or who defines the problem space (Diamond and Gomez, 2023; Doucet, 2021; Vetter et al., 2022). If and when these norms become institutionalized (Anderson and Colyvas, 2021), they can marginalize community and practitioner knowledge, prioritizing technical solutions over contextual responsiveness and adaptation. In other words, without deliberate attention to these dynamics, even equity-focused collaborations risk reproducing the very hierarchies they aim to transform (Anderson and Hayes, 2023; Doucet, 2021; Ishimaru et al., 2022; Tanksley and Estrada, 2022).

We propose a framework for designing equity-centered boundary infrastructure that operates at the intersection of research and practice. This framework is explicitly responsive to context, engages with power dynamics, and reflects transformative learning processes. These mechanisms serve as a foundational guide for developing tools and practices that engage research to foster transformative systems change in education. To illustrate this framework, we apply it to a commonly used resource designed to connect research and practice: the research brief. A research brief is a concise summary of research findings aimed at a non-academic audience. By drawing on a multi-district equity-focused initiative, we demonstrate how even well-established tools can be reimagined, when incorporated into learning opportunities, to act as catalysts for change. Finally, we discuss the implications of this framework for the design and study of equity-centered boundary infrastructure.

2 Reimagining research briefs

For decades, educational improvement efforts have promoted the use of research to inform policy and practice. These efforts often rely on a dominant model of research use, one that assumes research is produced by experts, translated into simplified formats, and then adopted by practitioners in the field (Farley-Ripple et al., 2018; Weiss, 1986, 1998). This model treats the process as linear and rational: research is discovered, disseminated, or transferred, and applied (e.g., Lavis et al., 2003; Drolet and Lorenzi, 2011). In this view, a core challenge is how to make research more accessible, accessible, visible, and actionable for end users.

Research briefs (or research-informed policy briefs, research summaries, and the like) often reflect this logic. Designed to summarize complex findings into short, digestible takeaways, briefs aim to make research “usable” for time-strapped educators and policymakers. Their design typically prioritizes clarity, brevity, and generalizability, and they often reflect the assumption that if authors present findings clearly and efficiently, practitioners will be more likely to change their thinking or behavior (Antonopoulou et al., 2021; Shakir et al., 2021; Lavis et al., 2009; Whitehurst, 2003; Uneke et al., 2015).

However, despite their popularity, there is little evidence that research briefs fulfill this promise (Arnautu and Dagenais, 2021; Beynon et al., 2012a, 2012b; Petkovic et al., 2018). Empirical studies have found that briefs have a limited influence on changing beliefs, influencing decisions, or prompting action (Beynon et al., 2012a, 2012b; Masset et al., 2013), particularly when distributed without deeper engagement (Moat et al., 2013). A recent systematic review in health policy sought to assess the effectiveness of evidence summaries on policymakers’ use of the evidence (Petkovic et al., 2018). Of the six randomized control trials included, none of these studies examined how policymakers actually utilized evidence in their decision-making (or lack thereof). Two studies relied on self-report measures from policymakers, finding that there was little to no difference in how they used the summaries.

This limited impact reflects a deeper misalignment between the assumptions underlying traditional brief design and what research tells us about how educators engage with evidence in their day-to-day practice. First, research use is inseparable from context. Educators encounter research in dynamic, real-world environments shaped by policy pressures, institutional routines, competing priorities, and community needs (Huguet et al., 2021; Ming and Goldenberg, 2021; Penuel et al., 2017). They interpret findings through the lens of their lived experiences and the specific histories, cultures, and challenges of the places where they work (Grooms et al., 2025; Moje, 2022). What appears to “work” in one district may not work in another, not because of implementation failure, but because research cannot be divorced from the social and political conditions in which it is taken up (Ghiso and Campano, 2024; Gutiérrez and Penuel, 2014; Welton et al., 2018). Briefs that present research as universally applicable risk erasing these contextual realities and overlooking the adaptations required for meaningful change (Arcury et al., 2017; Bell, 2019).

Second, how research is produced, shared, and legitimized reflects underlying power dynamics about whose knowledge counts (Muñiz et al., 2025). Too often, research dissemination privileges academic and technical knowledge while devaluing the lived expertise of educators and communities (Kirkland, 2019; Doucet, 2021). Research briefs can unintentionally reinforce these hierarchies. In the name of simplicity, they may flatten complexity, present findings as settled truths, and sideline community-rooted knowledge, especially that of historically marginalized groups (Chicago Beyond, 2019; Diamond, 2021). These dynamics can reproduce historical patterns of exclusion and extraction in educational research (Patel, 2015). In particular, efforts focused on equity-centered change require attention to whose voices it amplifies and whose perspectives it ignores.

Third, engagement with research is a process of sensemaking, interpretation, and learning (Honig et al., 2017; Coburn et al., 2009). Educators interpret research ideas through their professional roles, organizational contexts, and cognitive frameworks (Spillane et al., 2002; Coburn and Stein, 2010). This work is social and situated, where research becomes meaningful through dialogue, negotiation, and local relevance (Honig et al., 2017; Ming and Goldenberg, 2021; Wenger, 2000). Traditional briefs, designed for clarity and efficiency, can fail to support this interpretive work; they may offer information but ultimately provide limited support for meaning-making or reflection towards application in context.

Taken together, these areas highlight the limitations of conventional research briefs and point to the need for a new approach. To contribute to equity-centered systems change, research briefs—and other forms of infrastructure—can be reimagined in intentional ways to connect research to local values and histories, invite multiple forms of knowledge into the conversation, and support the negotiation of meaning. We turn to sociocultural theories of learning as a guiding lens for design.

3 Conceptual foundations

Sociocultural learning theory focuses attention on the interactions of people, tools, and contexts for learning, particularly within and across different communities of practice, such as researchers, practitioners, and policymakers (Wenger, 2000). This lens has proven especially valuable in understanding how knowledge is constructed and mobilized in joint activities (Penuel et al., 2015; Suchman, 1994). In particular, we draw on ideas from cultural-historical activity theory (e.g., Engeström, 2000; Engeström et al., 1995; Sannino and Engeström, 2018) and social practice theory (e.g., Lave and Wenger, 2002; Wenger, 1999, 2000).

A central concept in this framing is the boundary, a metaphor for the cultural, professional, organizational, or institutional distinctions that arise when individuals from different communities come together (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011; Akkerman and Bruining, 2016; Engeström et al., 1995, 2003). Learning at the boundary does not happen automatically, nor is it guaranteed (Ward et al., 2011). Boundary encounters often involve discontinuities, moments when communication breaks down, understanding falters, or collaboration stalls (Bronkhorst and Akkerman, 2016). Rather than being instances to be avoided, these moments can become generative sites of learning if surfaced and navigated intentionally (Engeström et al., 1995; Akkerman and Bakker, 2011).

The structures that mediate these processes make up what scholars refer to as boundary infrastructure (Star, 2002). Within this infrastructure, boundary objects (Star, 1999; Star, 2010; Star and Griesemer, 1989) can play a key role. These are material or conceptual artifacts that help coordinate meaning across groups by being both adaptable to local needs and shared enough to facilitate coordination across groups. The meaning of boundary objects is not static; instead, they gain significance in their use, through iterative interpretation and interaction (Wenger, 2000). For example, Johnson et al. (2016) discuss the development and application of an instructional rubric that served different purposes for various stakeholders. Teachers used the rubrics to guide student learning, district leaders drew on them to clarify standards, and researchers engaged the rubrics to study educational practice. Although the initial rubric had limitations (i.e., misalignment with teachers’ needs), adjusting the rubrics collaboratively ultimately improved their usefulness across role groups and fostered joint work among groups as well (Johnson et al., 2016).

Intentional efforts can connect boundary objects to boundary practices, the structured social interactions that bring together individuals from different communities, such as researchers, practitioners, or policymakers, to engage collaboratively across cultural, organizational, or disciplinary lines. Boundary practices refer to the interactive routines in which participants negotiate meaning, exchange ideas, and co-construct knowledge (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011). For example, one example of a boundary practice was the recurring network meetings that brought together educators and leaders from multiple districts to collaboratively work on improving mathematics instruction (Bohannon et al., 2025). These meetings, held every 2 months, involved shared mathematics activities, analysis of district and network data, and discussions to test and refine instructional strategies across classrooms. They involved county staff, partners, and district-level educators, including teachers, principals, instructional coaches, and district staff. They reflected a sustained routine that connected individuals across organizational boundaries and supported joint work.

To be effective, boundary infrastructure needs to enable coordination across different groups, roles, and settings while also supporting meaningful activity within each group. A boundary object functions as such only when it both facilitates collaboration across organizational or role-based divides and simultaneously mediates activity within each setting, adapting to the distinct practices, languages, and priorities of each (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011; Star, 2010). This dual function—bridging across boundaries while remaining coherent within them—is what allows boundary infrastructure to sustain shared work, while honoring the diverse forms of expertise and engagement within each community (Bowker and Star, 1999; Star and Griesemer, 1989). Without this ability to operate across and within, infrastructure risks becoming either too generic to be actionable or too narrowly tailored to a single group (Star, 1999).

Finally, designing boundary infrastructure requires attending to how learning unfolds through participation in socially and culturally situated practices (Lave and Wenger, 2002; Wenger, 1999, 2000). In this view, everyday norms, routines, tools, and structures reflect power dynamics of who is considered a legitimate participant, whose knowledge is valued, and whose questions or practices are centered or dismissed (Holland and Lave, 2019; Wertsch and Rupert, 1993). Boundary infrastructures that aim to connect different communities of practice must be intentionally designed to recognize and address power asymmetries between those communities. Without attention to how authority, norms, and institutional structures shape participation, such infrastructures risk reinforcing existing hierarchies rather than enabling equitable learning and practice (Grossman et al., 1999).

4 Design framework for boundary infrastructure

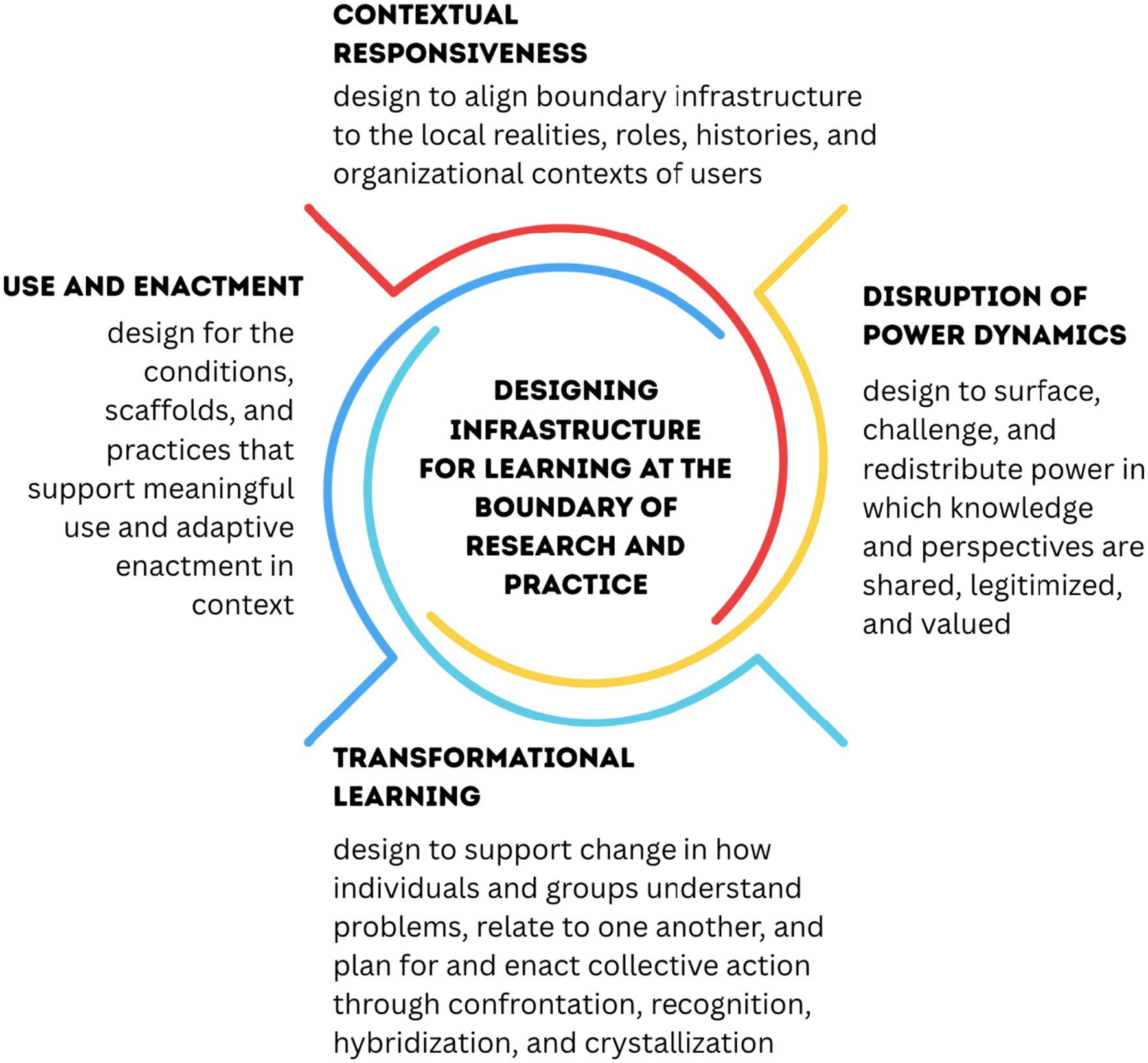

We propose a set of design dimensions that bridge this conceptual foundation with the practical work of creating tools and activities that enable context-sensitive, power-aware learning across diverse settings. Although we describe them separately, these four dimensions are overlapping and mutually reinforcing considerations to guide the design and enactment of boundary infrastructure (Figure 1).

4.1 Design for contextual responsiveness

Ideally, designers develop boundary infrastructure to support research-practice interactions with close attention to the contexts, roles, and relational histories of the involved communities and systems. Relevance and utility depend on how well boundary infrastructure aligns with users’ local realities, needs, challenges, timelines, and paces of work (Akkerman et al., 2021; Gutiérrez and Penuel, 2014; Farley-Ripple et al., 2018; Ming and Goldenberg, 2021; Penuel et al., 2017), not because it fits a one-size-fits-all template for tools or routines. Therefore, effective boundary infrastructure enables the explicit negotiation of questions that are deeply rooted in the specific conditions and priorities of its users, allowing research to contribute ideas (Ackerley and Balka, 2024). Multiple strategies for rooting infrastructure in users’ needs or preferences already exist, such as incorporating multiple opportunities for review or feedback, or, when possible, co-construction (Bekker et al., 2010), which allows the content or form of tools to reflect local conditions best. Ideally, boundary infrastructure is adaptable and flexible enough to create entry points for multiple role groups, organizations, geographic settings, and political or cultural environments.

4.2 Design to disrupt power hierarchies

At the boundaries between educational practice, communities, and research, there are (as always) a variety of power dynamics. Some treat research knowledge and theory as “Truth” in comparison to practitioner or community knowledge. Indeed, there are longstanding patterns of trauma, extraction, and disrespect between researchers, educational practitioners, and communities (Chicago Beyond, 2019). Intersecting dynamics of race, gender, class, (dis)ability, and language actively shape whose experiences communities center, whose knowledge they legitimize, and how people engage, participate, and co-construct problems and solutions in collective work (Bang and Vossoughi, 2016; Vakil et al., 2016; Zavala, 2016).

Boundary infrastructure is inherently political, situated within the power dynamics of those who develop and use it. Infrastructure is always produced within existing contexts of normative relationships, power dynamics, and assumptions about the value of certain forms of knowledge (Hawkins et al., 2017; Huvila, 2011). The development, content, and use of boundary infrastructure can thus either perpetuate or disrupt these existing assumptions and dynamics (Ballard et al., 2023; Oswick and Robertson, 2009).

4.3 Design for transformational learning

While Akkerman and Bakker (2011) highlight several pathways for learning, we focus on transformative learning as a central aim of boundary infrastructure. By transformation, we mean a change in how individuals and groups perceive problems, interact with one another, and plan for and implement collective action.

Akkerman and Bakker (2011) propose that transformational learning unfolds through non-linear phases, each of which can be supported by intentionally designed boundary infrastructure. The first phase, confrontation, involves identifying and surfacing equity-relevant tensions. These are issues or questions where values, assumptions, or lived experiences might conflict. Here, effective design creates openings for critical reflection and (re)thinking. The second phase, recognition, occurs when individuals come to see that their local challenges reflect broader, systemic issues. By engaging together through cross-context dialogue or synthesis activities, participants may notice patterns across roles and locales, helping them shift from isolated struggles to a shared problem space. In the third phase, hybridization, designers can bring together diverse perspectives into active dialogue for epistemic negotiation, where assumptions are interrogated and new, integrated understandings might emerge. This phase requires designing in ways that validate multiple forms and intentionally creating space for new ways of knowing. Finally, crystallization involves synthesizing these new insights into actionable, context-sensitive strategies. Boundary infrastructure might support this phase through shared documentation or iterative tools that help teams co-construct practices responsive to their local realities. These phases can unfold in sequence but more commonly unfold in ways that designers cannot predict ahead of time. Further, practices that are crystallized can be reshaped, or even undone entirely, particularly as collaborative efforts fall apart.

4.4 Design for use and enactment, not just designation

A final principle in designing boundary infrastructure is attending to the difference between tools as designated boundary objects and as boundary objects-in-use (Levina and Vaast, 2005; Melville-Richards et al., 2020). Designated boundary objects are tools or routines intended to support engagement across roles or communities. However, the mere act of designating a tool as a boundary object does not guarantee that it will enable meaningful interaction, sensemaking, or change. Designation, which can come from power attributed to certain actors in a change effort, can constrain the potential for a tool to become a powerful boundary object (Spee and Jarzabkowski, 2009; Wertsch and Rupert, 1993). Tools may remain superficial or compliance-driven (Jabbar and Childs, 2022; Wronowski et al., 2022) if they do not resonate with participants’ contexts, disrupt existing power dynamics, or support the kinds of learning interactions that lead to transformation (Philip et al., 2016). In contrast, boundary objects-in-use are those that become meaningful in their enactment. They are taken up, adapted, and used in different ways that reflect the new possibilities across research and practice boundaries (Campos et al., 2024; Furman, 2022).

This principle carries two key design implications. First, it underscores the importance of designing the artifact itself (e.g., a research brief or protocol) alongside the conditions, practices, facilitation moves, and other scaffolds that support how people might engage with it, and to different ends. In this case, supporting the use of the artifact involves ensuring alignment with the local context, attending to power relations, and providing support for engagement in transformational learning. Second, it urges designers to examine and reflect on how people enact and use tools in practice. This work involves gathering feedback, observing patterns of uptake or resistance, iterating based on whether the tool fosters the intended shifts in understanding, relationships, or collective action, and redesigning in the future (Campos et al., 2024).

5 Illustrating the framework

We focus on one commonly used tool, the research brief, as an example of how even familiar resources can be reimagined to support equity-centered research use better. We illustrate how the design framework, emphasizing contextual responsiveness, disrupting power, supporting transformational learning, and designing for use, shaped both the development and enactment of Problem of Practice (PoP) Briefs and associated learning sessions. Drawing on design notes, field notes, artifacts, and participant feedback from this experience, we present an analytical example of crafting boundary infrastructure to support equity-focused, cross-boundary learning in complex systems. We aim to illustrate, not provide a universal model.

5.1 Context

The Equity-Centered Principal Pipeline Initiative (ECPI) was a multi-year, cross-district initiative focused on advancing equity in school leadership development. The initiative had two primary goals. First, eight public school districts worked to plan and implement system-level changes aimed at achieving educational equity through leadership pipelines. Each district received significant, multi-year grants along with technical assistance to support their efforts. Second, ECPI aimed to contribute to the broader knowledge base on equity-centered leadership, producing research that could benefit both participating districts and the field at large. The Wallace Foundation provided funding for these efforts.

As part of ECPI, the eight districts participated in a professional learning community (PLC) that met three times each year. Each district sent a District Partnership Team (DPT), which included central office leaders from various departments, school-level leaders, university partners involved in principal preparation, and representatives from state education agencies. Additionally, staff from the Foundation, technical assistance providers, consultants, and ECPI researchers participated in these meetings. Our team’s role in ECPI was to design strategies that connect research with practice, supporting the meaningful use of research across districts. In this particular instance, “our team” includes the authors of this paper and our colleagues who were involved in development of the briefs.

At the initial PLC convenings, we observed that research was framed mainly and presented in traditional ways, as reflected in our analysis of PLC agendas, materials, and field notes. Research served primarily to justify and motivate the structure of the initiative, drawing on studies that emphasized the importance of school leadership and positioned principal pipelines as an “effective, feasible, and affordable” strategy for school improvement (Gates et al., 2019). This framing reinforced a view of research as a source of established truths, something to be accepted and acted upon rather than interrogated or adapted. Additionally, ECPI researchers were positioned in conventional roles as observers or data collectors, often serving as peripheral or “outsiders” to the sensemaking and strategy work of the districts themselves. Generally speaking, little attention focused on strategies for supporting engagement with research as a part of the active, ongoing work of ECPI leaders. We aimed to design at this intersection of existing research, knowledge of local contexts, and cross-site learning.

We acknowledge that our position as an ECPI research team tasked with designing and testing strategies linking research and practice conferred a level of authority over how knowledge is curated, represented, and legitimized. To mitigate the influence of this positional authority, we built in a series of checks throughout the design process including incorporating multiple forms of knowledge and developing a review process that engaged individuals with diverse perspectives, including differences in racial and ethnic identity, professional roles (district leader, network leader, researchers), and lived experiences. These steps were aimed at surfacing blind spots, challenging assumptions, and expanding the boundaries of what was considered legitimate knowledge. Finally, we paired the brief with a learning session designed to put any of these ideas in conversation with local wisdom and cross-district insights. Nonetheless, we recognize that these efforts, while necessary, were likely not sufficient to eliminate all embedded power asymmetries.

5.2 Goals and rationale

Within this context, two goals guided our design process to develop and contribute a series of Problems of Practice (PoP) Briefs, paired with facilitated cross-district learning sessions at the PLC in 2022.

First, we aimed to reposition research in ECPI. We sought to intentionally shift research from static evidence to a resource for reflection, dialogue, and shared problem-solving, exploring the deeply situated complexities of districts’ equity-centered leadership work. Furthermore, we designed the Briefs and learning sessions to surface and connect multiple forms of knowledge, including research insights, practitioner expertise, and local context wisdom, without privileging one above the others. Second, we sought to support district teams in identifying actionable strategies and directions that were relevant to their local contexts. The design aimed to encourage participants to surface questions, reflect on the constraints and assets of their systems, and develop strategies for equity-driven change that they could implement within their contexts.

Our design process led to the creation of both the PoP briefs (designed to serve as boundary objects) and the collaborative learning sessions (designed to serve as a boundary practice) as an integrated infrastructure for cross-role and cross-district engagement around research and locally driven problems of practice.

5.3 Designing the briefs

5.3.1 Focus

Each Brief centered on a district-defined problem of practice, grounded in the concrete challenges districts were navigating in their efforts to build and sustain equity-centered leadership pipelines. These questions emerged during earlier PLC conversations. While the original questions reflected the specific needs and experiences of individual districts, we made intentional adjustments to ensure they were appropriate and relevant across district contexts. We shared the revised PoP questions with key leaders at each district to ensure they continued to reflect local priorities and concerns. The final versions of the questions aimed to surface both the specificity of the originating district’s experience and the broader relevance of the issue across diverse district contexts. PoP questions included the following:

• What kinds of organizational structures are necessary to develop integrated equity-focused leadership development models across silos?

• How can departments deliberately and intentionally align their respective efforts so that programs, professional learning, resources, and supports result in the development of equity-centered leadership?

• What does a tiered system of principal support look like (from recruitment to placement, development, and assessment) that supports equity-centered leadership?

• How can we align pre-service preparation and hiring efforts to create equity-centered leadership pipelines?

• How do we shift the principal supervisor role from evaluator to coach of equity-centered leadership?

• How do we establish a job-embedded support system for developing equity-centered Assistant Principals?

• How can we integrate principal voices from within the district while also navigating relationships with external partners, all while scaling the work?

• How can we leverage individual commitments to equity into a coherent district culture and strategy that advances equity-centered leadership?

5.3.2 Content

Each of these questions reflected areas where research might provide insights. However, we intentionally curated the information in each Brief in ways that expanded what “counted” as relevant knowledge, thus challenging traditional power dynamics in knowledge production. First, each Brief drew from peer-reviewed research as well as practitioner-authored materials, leadership blogs, professional reports, etc. Second, in deciding what materials to bring forward, we sought to elevate the expertise of scholars and practitioners of color, as well as those whose contributions might be less prevalent in dominant academic channels (Dworkin et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2022). Third, given that equity-centered pipeline initiatives represent a relatively new and understudied area in education, we drew on related literature from other fields, including systems change, change management, critical accounts of educational change, adult and systems learning, policy implementation, and transformational change. Finally, the briefs also reflected “gray matter” that could potentially be useful for the issue at hand (Paez, 2017). Overall, this approach repositioned research as one among many valid sources of insight and reflected the position that a single research report or paper would provide “the answer” to complex problems of practice and systems change.

5.3.3 Structure

We structured each Brief as a concise tool, 3–4 pages in length, that combined a framed challenge (1 page), a synthesis of relevant ideas and strategies (1–2 pages), and a set of structured prompts to guide context-specific thinking (1 page).

The structure of the PoP reflected opportunities for the phases of transformational learning for those who engaged with it (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011). The first section aimed to foster both confrontation with the focal problem of practice and recognition of a shared problem space by articulating and validating why the problem of practice is a complex challenge. Drawing on Schön’s (1992) insight that “in real-world practice, problems do not present themselves as givens, they must be constructed from the materials of problematic situations which are puzzling, troubling, and uncertain” (p. 39–40), the Brief allocated approximately a quarter of its space to problem framing. This section aimed to contextualize the issue, clarify boundaries around what was or was not included, and surface deeper understandings of the systemic root causes embedded in organizational or systems practices and structures.

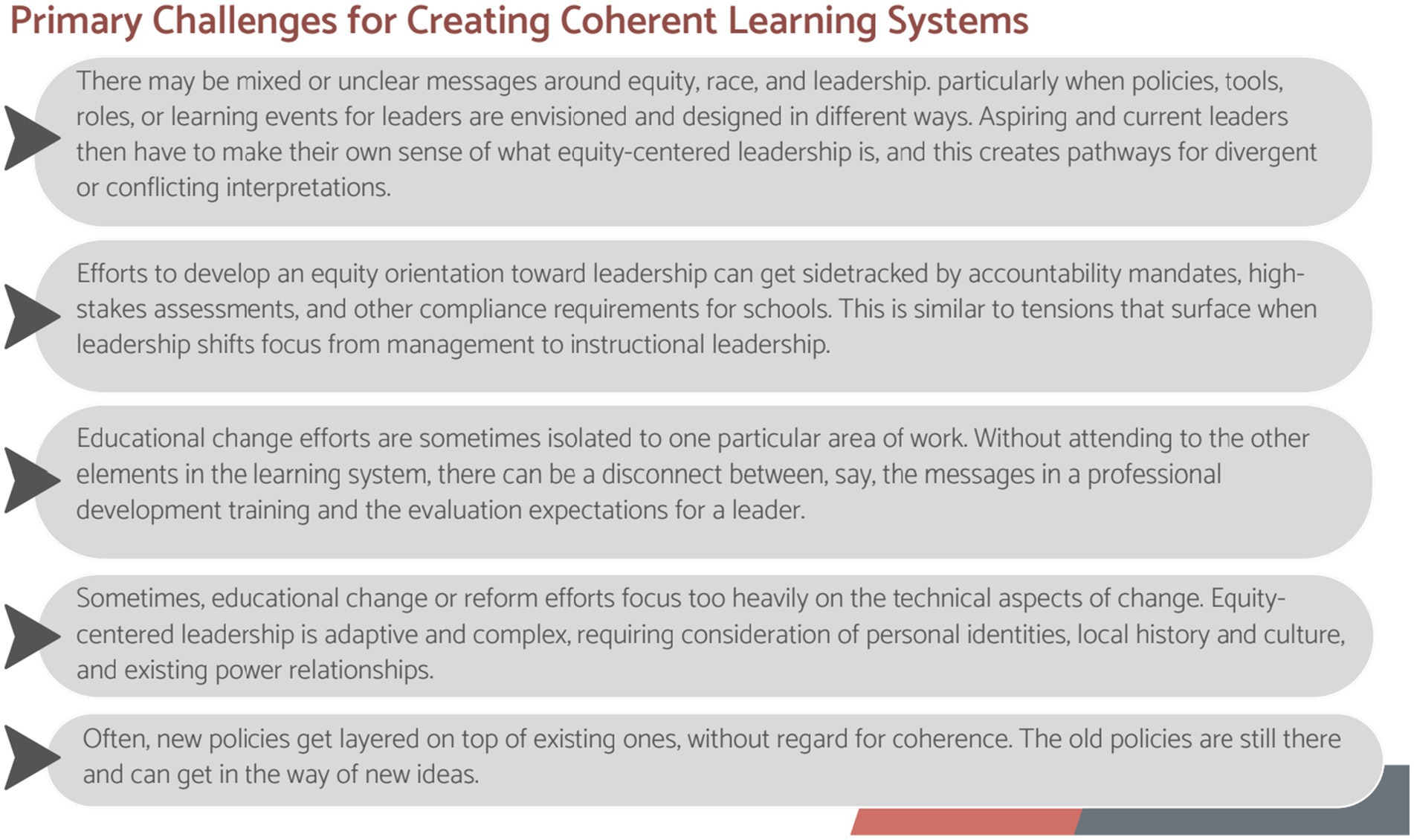

For instance, in the Brief related to the challenge of creating coherent learning systems for equity-centered leadership, the first page included the text shown in Figure 2. The goal of this section was to convey that research from other contexts also recognized the challenges within the problems of practice surfaced by district leaders.

The next section of the Brief focused on presenting a set of ideas drawn from various sources, including research. This section did not present prescriptive solutions but offered an adaptable menu of strategies for participants to consider, recognizing that “there is no one right answer,” and that educators would need to contextualize in each district’s unique setting, constraints, and assets. In this way, the section had the potential to contribute to hybridization by broadening leaders’ understanding of possible approaches that they might adapt and incorporate into their unique contexts.

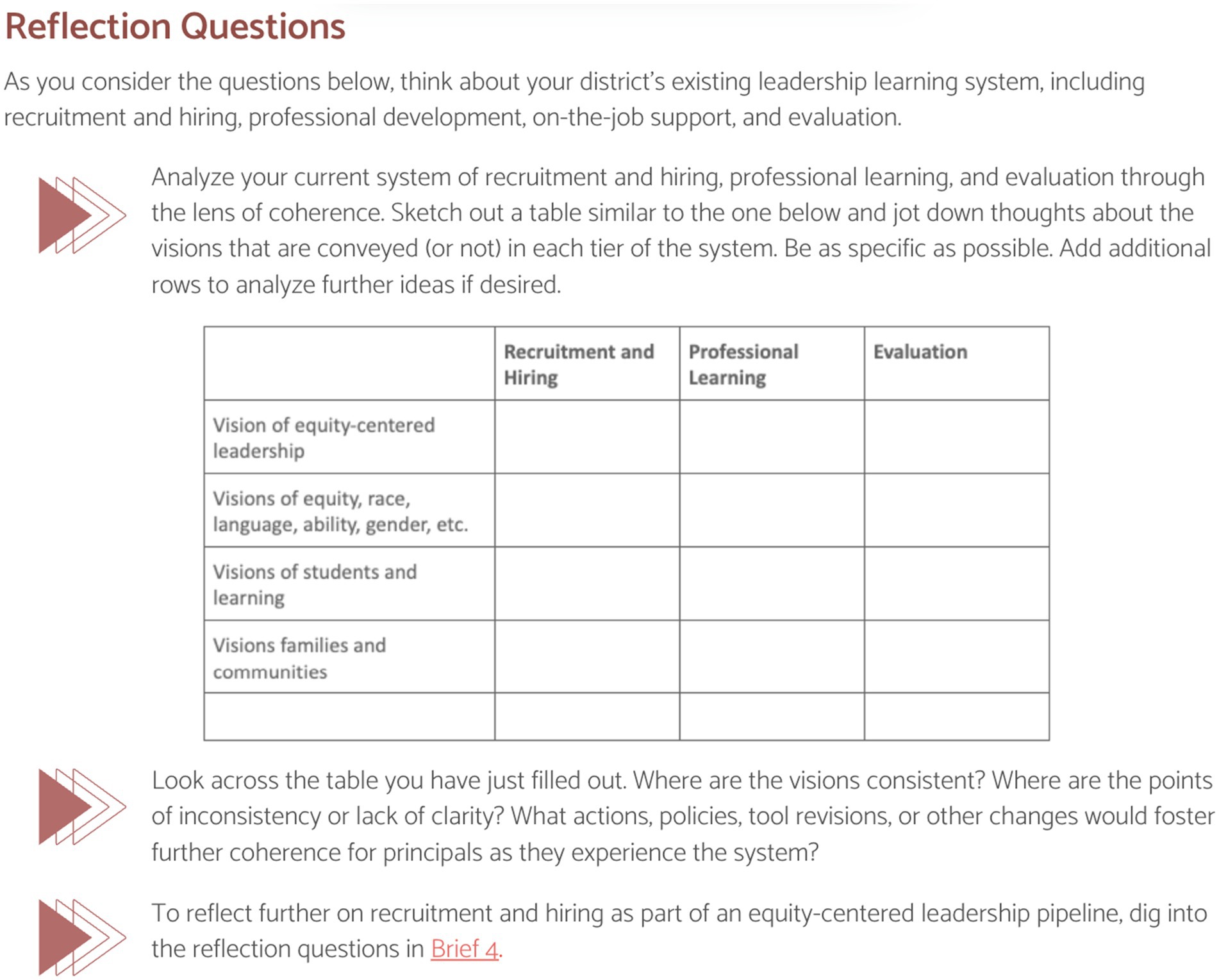

We dedicated the final quarter of the Brief to reflection and thinking tools, designed to guide participants through a structured process of sense-making, ideally moving them towards crystallizing new understandings of their systems and taking some concrete next steps. This reflective space was both retrospective, helping participants make sense of how they had previously understood and responded to the issue, and prospective, orienting toward future action, possibility, and adaptation (Weick et al., 2005). This structure fundamentally differs from conventional research briefs, which often emphasize recommendations for “what works” without attention to context, adaptation, or the complexity of real-world systems. We intentionally designed these reflections as activities rather than stand-alone recommendations or even discrete questions.

For example, Figure 3 illustrates one of the reflection activities included in the Brief on creating coherent learning systems for equity-centered leadership (similar to Figure 2, above). In this example, we designed the activity to engage leaders in applying some of the conceptual tools introduced in the Brief to the complexity of their contexts. We supported this activity within the learning session space (described further below), and we also sought to make it adaptable enough to be taken up by a group of leaders outside of a PLC learning session.

Ideas from research were represented in the text through embedded hyperlinks to publicly available resources, rather than via traditional academic citation structures. We included an “Additional References” section at the end of each document, prioritizing accessible materials authored by ECPI researchers. This approach reflects an intentional strategy to support research use by potentially leveraging the potential relationships between ECPI educators and researchers (Penuel et al., 2017).

Finally, we opted to format the Briefs using the graphic design program Canva as a visually compelling, interactive PDF document that compiled all eight of the briefs. This design decision was rooted in being responsive to the local district context. We assumed that official-looking documents (as opposed to unformatted Word Documents) were more likely to be perceived as usable and valuable by busy district leaders. This formatting also included embedded links and links between individual Briefs, to make the compilation of briefs a resource that leaders could return to and engage with in new ways over time as their learning needs and interests evolved.

As a designated boundary object, the PoP Brief format and structure were likely unfamiliar to many PLC participants. For practitioners and community members, the Brief offered a novel synthesis, framing the locally defined challenge, introducing conceptual tools, and incorporating accessible insights from existing research. From a traditional research perspective, the Briefs were also unconventional. They were grounded in district-identified problems of practice rather than researcher-defined inquiry questions, and they included substantive reflection prompts to spark dialogue about the design and implementation of ECPI efforts in local contexts.

5.4 Designing the learning session

Engaging with multiple forms of information (including research) requires people to interpret ideas, explore their relevance to local contexts, and collaboratively identify or adapt solutions, often in light of the financial, political, material, and temporal constraints of district life (Coburn et al., 2020; Huguet et al., 2021; National Research Council, 2012).

We designed an in-person, 2 hour learning session structured around Problems of Practice (PoPs). Participants were organized into 10 groups, each situated in a separate room and composed of approximately 15–20 people. Each group focused on one selected PoP. Due to high interest in two particular PoPs, we offered concurrent sessions for those topics, resulting in two separate groups exploring the same PoP. Within each group, the session included structured opportunities for smaller breakout discussions, during which participants engaged in conversations in groups of 3–4 individuals. During the sessions, participants engaged with Google documents as structured notes pages for each PoP, allowing everyone access to one anothers’ thinking.

5.4.1 Structure

To intentionally disrupt traditional power dynamics around whose knowledge “counts,” we opened the session with a shared framing statement:

Powerful strategies for advancing equity-centered transformation in schools emerge at the intersection of knowledge and wisdom from local context, personal experience, professional expertise, and research.

This framing signaled a commitment to multiple forms of knowledge and aimed to set the tone for collaborative inquiry, where all voices and perspectives would be welcome and valued. To do so, we invited participants to bring their diverse identities, experiences, and perspectives into the conversation as essential assets to the work together. Figure 4 shows the slide used to prompt participants to consider the full range of experiences relevant to our shared work.

The session was structured to provide extended, deliberate time for sensemaking, reflection, and knowledge integration in mixed-district groups. Across multiple cycles during the two-hour session, participants engaged with each section of the PoP Brief through layered modalities: first through individual reflection, then by contributing to a shared Google Doc, and finally through small-group and whole-group discussions.

Our use of a shared, public Google Doc served several design goals aligned with boundary-crossing and equity principles. First, participants could engage in multiple ways, depending on their comfort and communication preferences. Second, it helped surface localized insights, giving public visibility to local knowledge that might otherwise remain private. Third, it legitimized emergent, situated insights by treating them as equally valuable contributions to the collective learning. Finally, the Google Doc-supported hybridization encouraged participants to integrate ideas from the Briefs with their own and others’ lived and professional experiences, co-constructing new understandings.

Finally, each session had two facilitators, one from the “Leadership” community (i.e., a consultant hired by the Foundation who had an extensive background and experience in K-12 leadership) and the “research” community (i.e., an ECPI research member or member of the Foundation who had a research background). Researcher facilitators were intentionally chosen based on their orientations towards, and past experiences with, facilitating at the intersection of research and practice in ways that disrupt power dynamics. Facilitators played equal roles in guiding and supporting the conversation. The design aimed to include multiple perspectives during the session, rather than allowing participants to perceive it as an activity driven solely by researchers. In this vein, we encouraged the Leadership Facilitator to open, introduce, and frame the session’s goals. Furthermore, in our pursuit of disrupting power dynamics at the boundary between research and practice, we explicitly instructed facilitators not to convey that the Briefs possess all the answers or hold more useful knowledge than leaders’ own experiences and knowledge.

5.5 Learning at the boundaries: a session vignette

Within and across the learning sessions, participants engaged in structured conversations that surfaced critical insights, tensions, and questions related to the Problems of Practice (PoPs). These small-group conversations served as generative sites for sensemaking, where participants built on one another’s ideas, interrogated research-based concepts, and introduced new directions for inquiry. Learning unfolded not in a linear arc but through dynamic exchanges that reflected the four boundary-crossing mechanisms proposed by Akkerman and Bakker (2011): confrontation, recognition, hybridization, and crystallization.

To illustrate, we consider one group with three leaders from different districts and an ECPI research team member. The group focused on the Brief that outlined the persistent challenge of siloing in district central offices. The PoP Brief defined siloing as a common issue in large districts, where departments operate independently, and cross-departmental collaboration is minimal. This framing served as a moment of confrontation, surfacing a shared tension that allowed them to reflect critically on their organizational dynamics.

During the dialogue, the group members began to recognize and name how their localized experiences reflected broader systemic patterns. District leaders shared what siloing looked like within their central offices, based on their different vantage points. They also drew on past experiences in other roles or settings as a way to surface their prior understandings and develop a shared understanding of what siloing in central offices was and some of its consequences.

The group then began to integrate and hybridize diverse sources of knowledge, including personal experiences and research-based ideas, to gain new insights. Two leaders shared stories of how they sought to redesign meeting spaces to break down siloes within their districts. A third leader introduced the book The Art of Gathering and shared how she applied its principles to plan more inclusive, cross-departmental leadership meetings. The member of the ECPI research team contributed a complementary idea from research in classroom settings, highlighting how engagement deepens when learners interact with peers’ ideas rather than passively receiving information (Cobb et al., 2018). After discussing what made specific meetings more generative and how leadership structures could support authentic co-creation, the group note taker recorded the following statement in the shared Google Doc: “Co-creating helps break down the silos, rather than reporting out.” Participants developed this idea through dialogue and joint sensemaking, rather than from a predefined element in the Brief.

Opportunities for critical refinement also surfaced. One district leader questioned the universality of the Brief’s framing, suggesting that siloing may manifest differently, or not at all, in smaller districts, which presumably had fewer people in their central office staff. They collectively wondered how smaller districts distributed responsibilities and coordinated work. This comment prompted another group member to note on the Google document:“It is helpful to learn from districts of other sizes.” From this interaction, a new idea emerged, one that contrasted with the original framing of the PoP and offered a new direction for consideration.

Finally, the group’s ideas began to crystallize, as leaders surfaced new questions or directions for future inquiry, and identified possible next steps within their own districts. For instance, one district leader wondered when and if well-intended efforts to increase collaboration might lead to “meeting fatigue” and blurred responsibilities. The shared document reflected this new question, one that acknowledged the complexity and potential tradeoffs involved in breaking down siloed work: “What are the unintended consequences of breaking down silos?” For all groups, we sought to nudge leaders towards crystallization by having each of them write down and then share one new idea or insight related to the focal problem of practice that they intended to bring back to their colleagues in their own districts.

Together, this episode illustrates how the intentional design of the sessions created opportunities for participants to surface tensions, recognize shared patterns, integrate knowledge from multiple sources, and begin articulating new strategies, all key mechanisms in transformational learning across roles and systems.

5.6 Learning for future design

Our design framework highlights that even well-intended tools do not automatically function as intended simply by their design. While it might be tempting to assume that a tool “worked” as designed or that the learning session did support learning, designers must examine the enactment of the tool in diverse contexts and gather feedback to inform iterative redesign. Below, we demonstrate two ways in which we gathered and reflected on the enactment of the PoP Briefs, considering (1) the adaptation that happened across sessions and (2) how the PoP Briefs or ideas from the learning sessions were discussed or taken up outside of the learning session.

5.6.1 Learning from variation in enactment in the learning sessions

The PLC sessions were intentionally structured to support extended engagement with the Briefs across district boundaries. However, with over a dozen rooms running simultaneously, each with a different research–leadership facilitator pair, we knew that the conditions of enactment could vary significantly. Some facilitation teams had prior relationships and engaged in pre-session planning, while others met for the first time and took a more improvisational approach. Differences in familiarity with the Briefs, assumptions about facilitation roles, and experience with past PLC norms also shaped how sessions unfolded.

Post-session survey data confirmed that adaptation was a common occurrence. Ten of thirteen facilitators reported adjusting timing, altering discussion formats, or reinterpreting their facilitation stance in response to group dynamics. We do not treat this variation as an implementation error, but rather as evidence that enactment of boundary objects and practices is an interpretive act, shaped by real-time judgment and context. This insight reinforces the design principle that supporting use involves designing for principled flexibility, offering facilitators enough structure to remain aligned with learning and equity goals, while allowing room to adapt. For future design efforts, we identified a need to provide more explicit guidance on facilitation roles (particularly where they diverge from previous or traditional PLC norms) and provide opportunities for advanced planning between facilitation partners.

5.6.2 Learning about enactment beyond the learning sessions

Finally, we sought to understand how the Briefs or ideas from the learning sessions were incorporated into district conversations that followed. Each District Partnership Team (DPT) convened a post-PLC meeting, and members of our team attended a subset of these to observe whether the Briefs or related ideas contributed to their discussions.

In several cases, we saw signs of engagement. In one district, a cabinet-level leader who had participated in the session on coherent learning systems reflected on the matrix activity shown in Figure 3:

Our principal evaluation does not in any way, shape, or form align with our vision of equity-centered leadership. I don’t know what you did in your Problem of Practice session, but when we got to that part of the matrix for evaluation, I was like, ‘nope, nope, nope.

This moment of reflection suggested that the Brief had prompted a questioning of current systems, a key design goal. While we cannot infer long-term change from this comment, it highlights the Brief’s role in connecting to local insights and possible actions.

In another district, a leader proposed integrating the PoP process more deeply into ongoing DPT work:

That model [referring to the PoP brief and session], at least for me, was probably the deepest learning of the PLC. We were wondering, could we do some versions of those reflection activities? Could we bring new problems of practice as we’re implementing and have research colleagues help find tools or articles?

This comment highlighted the Brief’s potential as reusable boundary infrastructure, a structure that could be applied outside the PLC environment to local district work and potentially adapted to support future dilemmas. Indeed, after the PLC, in this district, we were invited to support a conversation with a new group of leaders using the PoP brief and associated activities as a part of their local planning for district change.

6 Discussion and conclusions

Designers aiming to connect research and practice for equity-centered change must carefully consider context, power dynamics, transformational learning, and the enactment of tools and routines. We present a theory-informed framework for equity-centered boundary infrastructure that actively promotes learning across the boundaries of research and practice. This framework emphasizes four key dimensions—contextual responsiveness, disrupting power dynamics, supporting transformational learning, and focusing on use and enactment rather than mere designation—as essential for creating boundary infrastructure that can support equity-centered change. We identify two potential applications for this framework: (1) enhancing the design of effective boundary infrastructure and (2) evaluating whether that infrastructure is fulfilling its intended purpose in practice or leading to unforeseen outcomes.

6.1 Designing boundary infrastructure with the framework

With this framework, we demonstrate how even conventional tools, such as a research brief, can be intentionally designed and used to support reflection, dialogue, and shared meaning-making. However, the insights from the framework are applicable beyond research briefs. The same design principles could apply to any structure that aims to bridge the boundaries between research and practice. This framework can help design and implement research-practice partnership meetings, establish continuous improvement routines, facilitate professional learning experiences, develop coaching models, or create research-informed curricular tools.

For example, applying this framework to a meeting with researchers and practitioners could involve crafting an agenda that prioritizes practitioner-defined problems and includes activities to engage participants in reflecting on power dynamics within their collaborative efforts. It might also create opportunities for knowledge co-construction by encouraging dialogue and sharing diverse perspectives. Similarly, when designing a research-informed professional learning session, one could shift away from traditional formats like a “sage on the stage” lecture. Instead, the focus could be on scaffolding collaborative sensemaking activities that foster the co-creation of strategies tailored to participants’ specific local contexts.

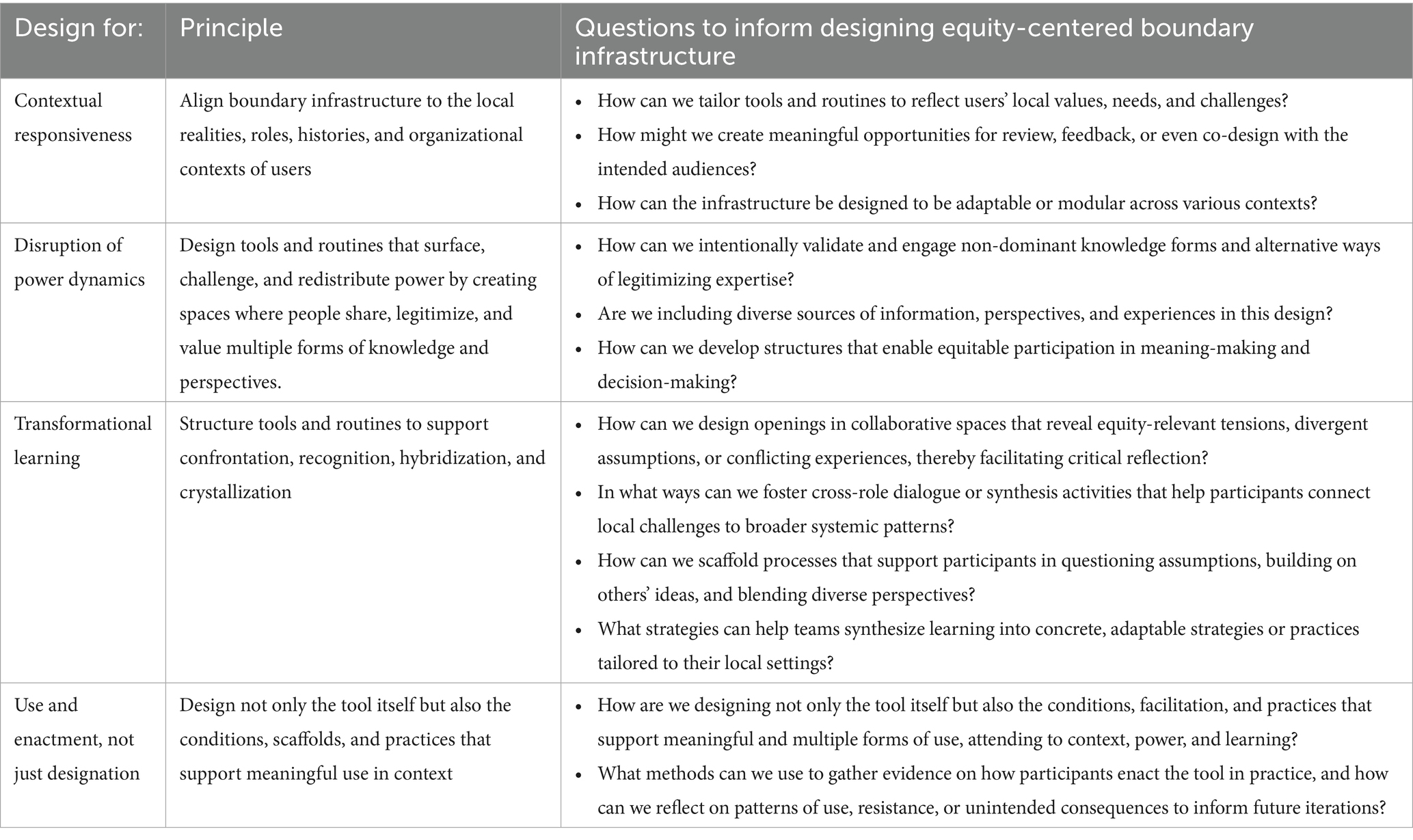

To assist in these efforts, Table 1 outlines the core principles from the design framework alongside questions that designers can consider. These questions can guide the development of more equitable boundary infrastructure, ensuring that both research and practice are better aligned to promote transformative change in education.

6.2 Studying the design and enactment of boundary infrastructure with the framework

This framework also serves as a valuable lens for examining the conditions under which boundary infrastructure functions effectively. By focusing on its four core dimensions (contextual responsiveness, power dynamics, transformational learning, and use and enactment), researchers can gain insights into how tools, routines, and practices are implemented and how they actually work within real-world settings. This guidance allows for targeted investigations into the effectiveness of various components of boundary infrastructure. By studying these aspects, we can better understand the factors that influence whether such boundary infrastructure fosters equity-centered change and identify potential barriers that may hinder their success in practice.

For instance, the dimension of contextual responsiveness prompts us to consider the degree to which boundary infrastructure aligns with or reflects the specific realities, roles, and histories of participants. Designers of boundary infrastructure might ask: Do users experience the tools and routines as relevant? Are they adaptable to the local practice conditions? Do the tools and routines function to coordinate work within a joint enterprise that involves contributions from people from different role groups, with different expertise, and with different proximity to power and authority within the system? Observing how participants engage with tools, including whether they adapt, ignore, or simply comply, can provide important insights into whether the infrastructure is effectively responding and reflecting the complexity of local contexts.

Second, the dimension of disrupting power dynamics prompts designers and facilitators to examine whose knowledge they center in collaborative processes. Are community members, practitioners, and historically marginalized stakeholders able to define problems meaningfully and contribute their expertise? If and how does the infrastructure reinforce existing hierarchies that privilege research-based knowledge over lived experience? Researchers can reveal how people negotiate and produce power dynamics in boundary spaces by documenting patterns of participation, voice, and influence through observation, interviews, or analysis of collaborative artifacts (see Coburn et al., 2008).

For instance, as part of our own design process, we recognized that the act of curating research carries the potential to either reinforce or disrupt dominant knowledge hierarchies. Starting with practitioner-identified problems of practice, we curated materials that included peer-reviewed research alongside practitioner-authored work, community-based publications, and gray matter across multiple bodies of literature. To enhance perspective-taking and reduce blind spots, each Brief underwent internal review by our team members who have multiple lived experiences and relevant perspectives/areas of expertise. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, we structured interactions around the Briefs that aimed to create opportunities for learning and additional new perspectives. While these efforts did not eliminate the power asymmetries inherent in knowledge production, they reflected an intentional effort to broaden the boundaries of what counted as “valid” knowledge.

A focus on transformational learning provides another critical lens. Here, researchers might look for evidence that participants are not simply exchanging information but are engaging in the transformational learning mechanisms described in boundary crossing theory (Akkerman and Bakker, 2011): confrontation, recognition, hybridization, and crystallization. Are tensions and divergent perspectives surfaced and addressed? Do participants come to see how their local challenges reflect and connect to broader systemic patterns? Are new, integrated ways of thinking developed and with what influence on individual and collective decisions or behaviors?

The fourth dimension, use and enactment, highlights how a tool’s design does not guarantee its intended impact. Studying use and enactment requires paying attention to how participants interact with the infrastructure: Are they reshaping it to fit their contexts? Are certain elements ignored, resisted, or understood in different ways? When are people engaging out of compliance (and with what consequences for sustained change), and when does learning reflect equity-centered change? Gathering data on patterns of uptake, adaptation, or resistance provides critical feedback about whether the infrastructure supports the intended learning and equity goals.

To investigate these questions, designers of boundary infrastructure could draw on a range of methods (see Bohannon et al., 2025). Observation during meetings or collaborative sessions can capture how participants engage with boundary tools in real-time and how conversations unfold across lines of role and expertise, attending to power dynamics in that space. Surveys and interviews can elicit participants’ reflections on whether they experienced the tools as relevant to their context, whether they disrupt power in their settings, and whether they are conducive to learning. Artifact analysis (i.e., examining shared documents, meeting notes, collaborative work products, or revisions to tools) might offer evidence of how knowledge was constructed, negotiated, or contested. Researchers could conduct longitudinal case studies to track how people sustain, adapt, or abandon infrastructure over time.

The examples from our project illustrate how the framework can offer valuable insights into both the design and study of boundary infrastructure. Although our data collection was intentionally limited (consisting of facilitator surveys, exit tickets, observation notes from post-Professional Learning Community (PLC) meetings, and session artifacts), the framework enabled us to uncover patterns that might otherwise have gone unnoticed. For instance, while including more voices in discussions is typically viewed as essential to promoting equity-focused change, the framework led us to explore questions like: What occurs when we create multiple avenues for engagement among participants? Are all voices equally influential in shaping the conversation and guiding new ideas, or do certain voices maintain more power? This line of questioning pushes us beyond merely achieving surface-level inclusion and encourages a deeper examination of how activity design influences support for participation.

Additionally, the framework’s distinction between designated and enacted tools highlights instances where tools or practices do not function as intended, such as the varied facilitation styles we observed across different sessions. These insights prompt critical questions: What aspects should we focus on when outcomes deviate from our expectations, and what assumptions or underlying constraints might we have overlooked? By fostering this type of inquiry, the framework can help us identify when longstanding norms or routines need reassessment to facilitate new and more effective ways of working.

Author contributions

CF: Investigation, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AR: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Visualization. TW: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. PA-T: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. KB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This publication is based on research commissioned and funded by The Wallace Foundation as part of its mission to support and share effective ideas and practices, Grant # 20210131.

Acknowledgments

We are so grateful to learn alongside the educators and leaders involved in the eight ECPI districts. We also thank Sarah Duran, Jackquelin Bristol, and Brian Lightfoot for the original development of the Briefs.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ackerley, C., and Balka, E. (2024). Navigating boundaries in coproduced research: a situational analysis of researchers’ experiences within integrated knowledge translation projects. Evid. Policy 20, 119–140. doi: 10.1332/174426421X16880459012690

Akkerman, S., and Bruining, T. (2016). Multilevel boundary crossing in a professional development school partnership. J. Learn. Sci. 25, 240–284. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2016.1147448

Akkerman, S. F., and Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 132–169. doi: 10.3102/0034654311404435

Akkerman, S. F., Bakker, A., and Penuel, W. R. (2021). Relevance of educational research: an ontological conceptualisation. Educ. Res. 50, 416–424. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211028239

Anderson, E., and Hayes, S. D. (2023). Continuous improvement: A leadership process for school improvement. Charlotte, NC: IAP.

Anderson, E. R., and Colyvas, J. A. (2021). What sticks and why? A MoRe institutional framework for education research. Teach. Coll. Rec. 123, 1–34. doi: 10.1177/016146812112300705

Antonopoulou, P., Chadwick, P., McGee, O., Sniehotta, F. F., Meyer, C., Lorencatto, F., et al. (2021). Research engagement with policy makers: A practical guide to writing policy briefs. NIHR: Policy Research Unit in Behavioural Science. Available online at: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10141871/1/A%20practical%20guide%20to%20writing%20policy%20briefs.pdf

Arcury, T. A., Wiggins, M. F., Brooke, C., Jensen, A., Summers, P., Mora, D. C., et al. (2017). Using 'policy briefs' to present scientific results of CBPR: farmworkers in North Carolina. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 11, 137–147. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2017.0018

Arnautu, D., and Dagenais, C. (2021). Use and effectiveness of policy briefs as a knowledge transfer tool: a scoping review. Humanit. soc. sci. commun. 8, 1–14. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00885-9

Ballard, H. L., Calabrese Barton, A., and Upadhyay, B. (2023). Community-driven science and science education: living in and navigating the edges of equity, justice, and science learning. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 60, 1613–1626. doi: 10.1002/tea.21880

Bang, M., and Vossoughi, S. (2016). Participatory design research and educational justice: studying learning and relations within social change making. Cogn. Instr. 34, 173–193. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2016.1181879

Bekker, M., van Egmond, S., Wehrens, R., Putters, K., and Bal, R. (2010). Linking research and policy in Dutch healthcare: infrastructure, innovations and impacts. Evid. Policy 6, 237–253. doi: 10.1332/174426410X502464

Bell, P. (2019). Infrastructuring teacher learning about equitable science instruction. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 30, 681–690. doi: 10.1080/1046560X.2019.1668218

Beynon, P., Chapoy, C., Gaarder, M., and Masset, E. (2012a). What difference does a policy brief make? Full report of an IDS, 3ie, Norad study. London, UK: Institute of Development Studies and the international initiative for impact evaluation (3ie)

Beynon, P., Gaarder, M., Chapoy, C., and Masset, E. (2012b). Passing on the hot potato: lessons from a policy brief experiment. IDS Bull. 43, 68–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2012.00365.x

Bohannon, A. X., Farrell, C. C., and Cook, S. (2025). Overcoming or overstepping? Boundary infrastructure for learning in the context of continuous improvement research-practice partnership. Front. Educ. 9:1441856. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1441856

Bowker, G. C., and Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bronkhorst, L. H., and Akkerman, S. F. (2016). At the boundary of school: continuity and discontinuity in learning across contexts. Educ. Res. Rev. 19, 18–35. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2016.04.001

Campos, F., Nguyen, H., Ahn, J., and Jackson, K. (2024). Leveraging cultural forms in human-centred learning analytics design. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 55, 769–784. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13384

Chen, B. (2024). A framework for infrastructuring sustainable innovations in education. J. Learn. Sci. 33, 583–612. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2024.2320159

Chicago Beyond (2019). Why am I always being researched? Chicago beyond equity series, volume one. Chicago, IL. Available online at: https://chicagobeyond.org/insights/philanthropy/why-am-i-always-being-researched/

Cobb, P., Jackson, K., Henrick, E. C., and Smith, T. M.MIST Project (2018). Systems for instructional improvement: Creating coherence from the classroom to the district office : Harvard Education Press.

Coburn, C. E., Bae, S., and Turner, E. O. (2008). Authority, status, and the dynamics of insider-outsider partnerships at the district level. Peabody J. Educ. 83, 364–399. doi: 10.1080/01619560802222350

Coburn, C. E., Honig, M. I., and Stein, M. K. (2009). “What’s the evidence on districts’ use of evidence?” in The role of research in educational improvement. eds. J. Bransford, D. Stipek, N. Vye, L. Gomez, and D. Lam (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press), 67–87.

Coburn, C.E., Spillane, J.P., Bohannon, A.X., Allen, A.R., Ceperich, R., Beneke, A., et al. (2020). The role of organizational routines in research use in four large urban school districts. Technical report no. 5. Boulder, CO: National Center for research in policy and practice.

Coburn, C. E., and Stein, M. K. (2010). Research and practice in education: building alliances, bridging the divide. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Diamond, J. (2021). Racial equity and research practice partnerships 2.0: a critical reflection. William T. Grant Foundation.

Diamond, J. B., and Gomez, L. M. (2023). Disrupting white supremacy and anti-black racism in educational organizations. Educ. Res. doi: 10.3102/0013189X231161054

Doucet, F. (2021). Identifying and testing strategies to improve the use of antiracist research evidence through critical race lenses. William T. Grant Foundation.

Dreier, O. (2009). Persons in structures of social practice. Theory Psychol. 19, 193–212. doi: 10.1177/0959354309103539

Dreier, O. (2008). “Learning in structures of social practice” in A qualitative stance: In memory of Steinar Kvale, 1937–2008. eds. K. Nielsen, S. Brinkmann, C. Elmholdt, L. Tanggaard, P. a. Musaeus, and G. Kraft (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press), 85–96.

Drolet, B. C., and Lorenzi, N. M. (2011). Translational research: understanding the continuum from bench to bedside. Transl. Res. 157, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.10.002

Dworkin, J., Zurn, P., and Bassett, D. S. (2020). (in)citing action to realize an equitable future. Neuron 106, 890–894. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.05.011

Engeström, Y. (2000). Activity theory as a framework for analyzing and redesigning work. Ergonomics 43, 960–974. doi: 10.1080/001401300409143

Engeström, Y., Engeström, R., and Karkkainen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learn. Instr. 5, 319–336. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(95)00021-6

Engeström, Y., Engeström, R., and Kerosuo, H. (2003). The discursive construction of collaborative care. Appl. Linguis. 24, 286–315. doi: 10.1093/applin/24.3.286

Farley-Ripple, E. N., May, H., Karpyn, A., Tilley, K., and McDonough, K. (2018). Rethinking connections between research and practice in education: a conceptual framework. Educ. Res. 47, 235–245. doi: 10.3102/0013189X18761042

Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A., Anderson, E. R., Bohannon, A. X., Coburn, C. E., et al. (2022). Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research–practice partnerships. Educ Res, 51, 197–208. doi: 10.3102/00

Furman, K. (2022). Epistemic bunkers. Soc. Epistemol. 37, 197–207. doi: 10.1080/02691728.2022.2122756

Gates, S. M., Baird, M. D., Master, B. K., and Chavez-Herrerias, E. R. (2019). Principal pipelines: A feasible, affordable, and effective way for districts to improve schools. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2666.html

Ghiso, M. P., and Campano, G. (2024). Methods for community-based research: Advancing educational justice and epistemic rights. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Grooms, A. A., Peters, A. L., and Lopez, E. (2025). When past is present and future: how contextualising a community’s historical context can shape the development of equity-focused principal pipelines. Urban Rev. 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s11256-025-00738-8

Grossman, P. L., Smagorinsky, P., and Valencia, S. (1999). Appropriating tools for teaching English: A theoretical framework for research on learning to teach. Am. J. Educ. 8, 1–29.doi: 10.1086/444230

Gutiérrez, K. D., and Penuel, W. R. (2014). Relevance to practice as a criterion for rigor. Educ. Res. 43, 19–23. doi: 10.3102/0013189X13520289

Hawkins, B., Pye, A., and Correia, F. (2017). Boundary objects, power, and learning: the matter of developing sustainable practice in organizations. Manag. Learn. 48, 292–310. doi: 10.1177/1350507616677199

Holland, D., and Lave, J. (2019). Social practice theory and the historical production of persons. In: Edwards, A., Fleer, M., Bøttcher, L. (eds) Cultural-Historical Approaches to Studying Learning and Development. Perspectives in Cultural-Historical Research, vol 6. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-6826-4_15

Honig, M. I., Venkateswaran, N., and McNeil, P. (2017). Research use as learning: the case of fundamental change in school district central offices. Am. Educ. Res. J. 54, 938–971. doi: 10.3102/0002831217712466

Huguet, A., Coburn, C. E., Farrell, C. C., Kim, D. H., and Allen, A.-R. (2021). Constraints, values, and information: how leaders in one district justify their positions during instructional decision making. Am Educ Res J, 58, 710–747. doi: 10.3102/0002831221993824

Huvila, I. (2011). The politics of boundary objects: hegemonic interventions and the making of a document. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 62, 2528–2539. doi: 10.1002/asi.21639

Ishimaru, A. M. (2019). Just schools: Building equitable collaborations with families and communities. Teachers College Press.

Ishimaru, A. M., Barajas-López, F., Sun, M., Scarlett, K., and Anderson, E. (2022). Transforming the role of RPPs in remaking educational systems. Educ. Res. 51, 465–473. doi: 10.3102/0013189X221098077

Jabbar, H., and Childs, J. (2022). “Critical perspectives on the contexts of improvement research in education” in The foundational handbook on improvement research in education. eds. J. D. Bryk, A. S. Mehta, and K. M. Frumin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press), 241–261.

Johnson, R., Severance, S., Penuel, W. R., and Leary, H. (2016). Teachers, tasks, and tensions: Lessons from a research–practice partnership. J. Math. Teach. Educ. 19, 169–185. doi: 10.1007/s10857-015-9338-3

Kirkland, D. E. (2019). No small matters: Reimagining the use of research evidence from a racial justice perspective. New York: William T. Grant Foundation.

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (2002). “Practice, person, social world” in An introduction to Vygotsky. Ed. H. Daniels (London: Routledge), 155–162.

Lavis, J. N., Permanand, G., Oxman, A. D., Lewin, S., and Fretheim, A. (2009). SUPPORT tools for evidence-informed health policymaking (STP) 13: preparing and using policy briefs to support evidence-informed policymaking. Health Res. Policy Syst. 7:S13. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S13

Lavis, J. N., Robertson, D., Woodside, J. M., McLeod, C. B., and Abelson, J.Knowledge Transfer Study Group (2003). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q. 81, 221–172. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052

Levina, N., and Vaast, E. (2005). The emergence of boundary spanning competence in practice: implications for implementation and use of information systems. MIS Q. 29, 335–363. doi: 10.2307/25148682

Masset, E., Gaarder, M., Beynon, P., and Chapoy, C. (2013). What is the impact of a policy brief? Results of an experiment in research dissemination. J. Dev. Eff. 5, 50–63. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2012.759257

Melville-Richards, L., Rycroft-Malone, J., Burton, C., and Wilkinson, J. (2020). Making authentic: exploring boundary objects and bricolage in knowledge mobilisation through National Health Service-university partnerships. Evid. Policy 16, 517–539. doi: 10.1332/174426419X15623134271106

Ming, N. C., and Goldenberg, L. B. (2021). Research worth using: (re)framing research evidence quality for educational policymaking and practice. Rev. Res. Educ. 45, 129–169. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211069073

Moat, K. A., Lavis, J. N., Clancy, S. J., El-Jardali, F., and Pantoja, T. (2013). Evidence briefs and deliberative dialogues: perceptions and intentions to act on what was learnt. Bull. World Health Organ. 92, 20–28. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.116806

Moje, E. B. (2022). Remaking research tools: toward transforming systems of inequality through social science research. Socius 8:1694. doi: 10.1177/23780231221081694

Muñiz, R., Okello, W. K., Lewis, M. M., Achampong, G., Mata, A., and Meyers, S. (2025). A critical knowledge praxis framework for educational policymakers and practitioners. Educ. Res. 54, 348–357. doi: 10.3102/0013189X251333699

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2022). The future of education research at IES: Advancing an equity-oriented science. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council. (2012). Using Science as Evidence in Public Policy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/13460

Oswick, C., and Robertson, M. (2009). Boundary objects reconsidered: from bridges and anchors to barricades and mazes. J. Chang. Manag. 9, 179–193. doi: 10.1080/14697010902879137

Paez, A. (2017). Gray literature: an important resource in systematic reviews. J. Evid. Based Med. 10, 233–240. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12266

Patel, L. (2015). Decolonizing educational research: From ownership to answerability. New York: Routledge.

Penuel, W. R. (2019). Infrastructuring as a practice of design-based research for supporting and studying equitable implementation and sustainability of innovations. J. Learn. Sci. 28, 659–677. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2018.1552151

Penuel, W. R., Allen, A. R., Coburn, C. E., and Farrell, C. (2015). Conceptualizing Research–Practice Partnerships as Joint Work at Boundaries. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 20, 182–197. doi: 10.1080/10824669.2014.988334

Penuel, W. R., Briggs, D. C., Davidson, K. L., Herlihy, C., Sherer, D., Hill, H. C., et al. (2017). How school and district leaders access, perceive, and use research. AERA Open 3. doi: 10.1177/2332858417705370

Petkovic, J., Welch, V., Jacob, M. H., Yoganathan, M., Ayala, A. P., Cunningham, H., et al. (2018). Do evidence summaries increase health policymakers' use of evidence from systematic reviews? A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 14, 1–52. doi: 10.4073/csr.2018.8

Philip, T. M., Olivares-Pasillas, M. C., and Rocha, J. (2016). Becoming racially literate about data and data-literate about race: data visualizations in the classroom as a site of racial-ideological micro-contestations. Cogn. Instr. 34, 361–388. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2016.1210418

Sannino, A., and Engeström, Y. (2018). Cultural-historical activity theory: founding insights and new challenges. Cult. Psychol. 14, 43–56. doi: 10.17759/chp.2018140304

Schön, D. A. (1992). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Routledge.

Shah, V., Cuglievan-Mindreau, G., and Flessa, J. (2022). Reforming for racial justice: a narrative synthesis and critique of the literature on district reform in Ontario over 25 years. Canad. J. Educ. Admin. Policy 198, 35–54. doi: 10.7202/1086426ar

Shakir, F. N., Kazi, M. R., Chowdhury, N., Baig, K., Shahid, M., and Turin, T. C. (2021). Developing policy briefs as a knowledge engagement tool to mobilize research towards implementation or translate knowledge to action. South East Asia J. Public Health 11, 10–19. Available online at: https://seajph-phfbd.org/index.php/seajph/article/view/8

Spee, A. P., and Jarzabkowski, P. (2009). Strategy tools as boundary objects. Strateg. Organ. 7, 223–232. doi: 10.1177/1476127009102674

Spillane, J. P., Reiser, B. J., and Reimer, T. (2002). Policy implementation and cognition: reframing and refocusing implementation research. Rev. Educ. Res. 72, 387–431. doi: 10.3102/00346543072003387

Star, S. L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. Am. Behav. Sci. 43, 377–391. doi: 10.1177/00027649921955326

Star, S. L. (2002). Infrastructure and ethnographic practice: working on the fringes. Scand. J. Inf. Syst. 14:6. Available online at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol14/iss2/6

Star, S. L. (2010). This is not a boundary object: reflections on the origin of a concept. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 35, 601–617. doi: 10.1177/0162243910377624

Star, S. L., and Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, 'translations' and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci. 19, 387–420. doi: 10.1177/030631289019003001

Suchman, L. A. (1994). Working relations of technology production and use. Comput. Support. Coop. Work 2, 21–39.

Tanksley, T., and Estrada, C. (2022). Toward a critical race RPP: how race, power and positionality inform research practice partnerships. Int. J. Res. Methods Educ. 45, 397–409. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2022.2097218