- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia

Introduction: The rapid advancement of generative artificial intelligence (AI) has created new opportunities and challenges in higher education, particularly in STEM disciplines. Understanding the factors that influence students' behavioral intention to adopt generative AI is essential for effective integration into learning environments. This study applies the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) to examine these factors among STEM students.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 464 STEM students at Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University in Saudi Arabia. Data were analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the proposed model. Model fit indices indicated good fit (χ2/df = 2.94, GFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.056, NFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.94).

Results: Performance expectancy (β = 0.491, p < 0.001), effort expectancy (β = 0.130, p < 0.001), social influence (β = 0.239, p < 0.001), and facilitating conditions (β = 0.213, p < 0.001) significantly predicted behavioral intention to adopt generative AI. Subgroup analyses revealed higher adoption intentions among female students, those with beginner-level computer experience, and students majoring in Engineering and Computer Science.

Discussion: The findings highlight the crucial role of perceived usefulness, ease of use, social norms, and institutional support in influencing AI adoption among STEM students. To enhance adoption, the study recommends improving digital infrastructure, providing targeted AI training, and promoting peer-led initiatives. Future research should investigate longitudinal and cross-cultural dynamics of AI adoption in education.

1 Introduction

Science, Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education represents a critical foundation for equipping students with the skills needed in today's digital and innovation-driven workforce (Aithal, 2025; Chasokela and Moyo, 2025). However, traditional instructional methods often fall short in helping students grasp complex concepts and stay engaged in their learning, especially as educational demands and industry expectations evolve (Scherer and Teo, 2019; Sungur Gül and Ateş, 2023; Plageras et al., 2023). In response, educators and institutions are increasingly exploring artificial intelligence (AI), particularly generative AI, as a transformative tool for enhancing STEM teaching and learning.

Generative AI technologies offer dynamic capabilities such as real-time feedback, personalized learning paths, and interactive environments that can increase student motivation and academic performance (Chen et al., 2022; Xu and Ouyang, 2022; Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2023). These tools have shown particular promise for students who struggle with traditional methods, enabling deeper engagement and improved understanding of abstract STEM concepts (Krasovskiy, 2020; McLaren et al., 2010; Hsieh and Chiu, 2019). Additionally, AI supports formative assessment by identifying students' strengths and weaknesses, allowing for more targeted instructional support (Hillmayr et al., 2020; Shin, 2020).

Despite these advantages, the adoption of AI in higher education remains uneven. Barriers include concerns about academic integrity, an issue extensively explored by Yusuf et al. (2024), whose cross-cultural study found that many perceive the use of GenAI in academic work as a form of cheating, highlighting deep ethical tensions and the need for clear regulatory policies. Similarly, these concerns are echoed across the literature, where barriers such as academic integrity, skepticism toward AI-generated content, infrastructural limitations, and insufficient faculty training are frequently cited (Abreh et al., 2025; Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Truong and Pham, 2025). These challenges highlight the need for more than just access to technology; successful integration depends on understanding the factors that influence user acceptance, particularly among students.

To explore these factors, researchers often apply the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), which identifies four key determinants of behavioral intention: performance expectancy (the belief that using a technology will lead to improved outcomes), effort expectancy (the perceived ease of use), social influence (the impact of others' expectations), and facilitating conditions (available resources and infrastructure) (Venkatesh et al., 2003). While UTAUT has proven effective in various educational contexts, the relative impact of each construct can differ across disciplines, cultural settings, and learner characteristics (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Ateş and Gündüzalp, 2025; Kumar et al., 2025; Lakulu et al., 2025).

Previous studies have produced mixed findings. Flores-Alonso et al. (2023) identified performance expectancy and self-efficacy as dominant factors in STEM adoption. In contrast, O‘dea and O'Dea (2023) emphasized the role of social influence and institutional support in non-STEM fields. Similarly, Du et al. (2025) and Han and Guo (2025) found differences in AI adoption across STEM and non-STEM disciplines, as well as across demographic groups. These inconsistencies suggest that AI adoption cannot follow a universal model but must instead be tailored to the unique demands of different academic disciplines, demographic subgroups, and educational environments. Moreover, many prior studies have primarily focused on Western or East Asian contexts such as the United States, China, or Malaysia (Mohamad Mozie et al., 2025; Lakulu et al., 2025), leaving a geographic gap in our understanding of how generative AI is perceived in Middle Eastern settings.

This study addresses these gaps by applying the UTAUT model to examine the behavioral intention of undergraduate STEM students in Saudi Arabia to use generative AI for academic purposes. It also explores how demographic and experiential variables, such as gender, field of specialization, and computer experience, shape students' perceptions and usage intentions. By focusing on a specific student population in a non-Western, Arab cultural context, this research contributes threefold: (1) it expands geographic representation in AI adoption studies, (2) it clarifies how the original UTAUT constructs function in STEM-specific, digital-native environments, and (3) it informs culturally responsive implementation strategies for integrating AI in higher education.

2 Literature review and hypothesis development

The This study builds upon the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) framework (Venkatesh et al., 2003) to investigate the behavioral intention of STEM students to adopt generative AI technologies in higher education. While UTAUT has been widely applied across diverse educational settings, the unique capabilities and complexities of generative AI call for a contextualized reinterpretation of its core constructs—performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions—within STEM learning environments.

Performance Expectancy (PE) reflects students' beliefs that using generative AI will enhance their academic performance through automation, personalized feedback, and improved problem-solving capabilities. Prior research highlights PE as a consistent and strong predictor of technology adoption (Venkatesh et al., 2003; Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2023). In STEM education, where mastery of complex concepts is critical, the potential for AI tools to support simulation, coding, and data analysis reinforces the relevance of PE (Chen et al., 2022; Xu and Ouyang, 2022). Therefore, this construct is expected to significantly influence students' intentions to adopt generative AI.

• Hypothesis 1 (H1): Performance expectancy positively affects STEM students' behavioral intention to use generative AI technologies.

Effort Expectancy (EE) pertains to the perceived ease of use of AI tools. Despite generative AI's increasingly intuitive interfaces, variability in students' technical expertise may influence their perceptions of usability (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Ateş and Gündüzalp, 2025). Research suggests that ease of use remains a critical determinant for adoption, particularly for those less experienced with advanced technologies (Suhail et al., 2024). In the context of generative AI, minimizing perceived complexity is essential to foster positive behavioral intentions.

• Hypothesis 2 (H2): Effort expectancy positively affects STEM students' behavioral intention to use generative AI technologies.

Social Influence (SI) captures the extent to which students perceive that important others—such as peers, faculty, and institutional leaders—endorse the use of AI technologies. As AI integration in higher education expands, normative pressures and endorsement by educators and peers can significantly shape adoption decisions (Han and Guo, 2025; Plageras et al., 2023). Given the ethical considerations and evolving discourse surrounding AI, social influence plays a crucial role in students' acceptance of generative AI tools.

• Hypothesis 3 (H3): Social influence positively affects STEM students' behavioral intention to use generative AI technologies.

Facilitating Conditions (FC) refer to the availability of technical infrastructure, training, and institutional support necessary for effective AI adoption. Prior studies demonstrate that adequate resources and assistance enhance students' capacity to utilize emerging technologies, bridging the gap between intention and actual use (Kumar et al., 2025; Mohamad Mozie et al., 2025). In the AI context, facilitating conditions include access to AI platforms, prompt engineering guidance, and reliable internet connectivity.

• Hypothesis 4 (H4): Facilitating conditions positively affect STEM students' behavioral intention to use generative AI technologies.

In addition to the direct effects of these constructs, this study incorporates moderating variables to examine how individual differences influence the strength and direction of the relationships. Moderators include gender, academic specialization, and computer experience, which prior research links to varying perceptions and adoption patterns in technology acceptance (Devi et al., 2025; Han and Guo, 2025; Suhail et al., 2024).

Gender may moderate relationships by reflecting differential trust, risk perceptions, and familiarity with AI technologies (Suhail et al., 2024). Academic specialization captures domain-specific exposure and perceived relevance, with STEM students potentially exhibiting stronger performance expectancy effects due to greater alignment with their coursework (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024). Computer experience relates to digital literacy and self-efficacy, likely amplifying the influence of performance expectancy while attenuating the impact of effort expectancy (Han and Guo, 2025).

• Hypothesis 5a (H5a): Gender moderates the structural relationships between UTAUT constructs and behavioral intention.

• Hypothesis 5b (H5b): Academic specialization moderates the structural relationships between UTAUT constructs and behavioral intention.

• Hypothesis 5c (H5c): Computer experience moderates the structural relationships between UTAUT constructs and behavioral intention.

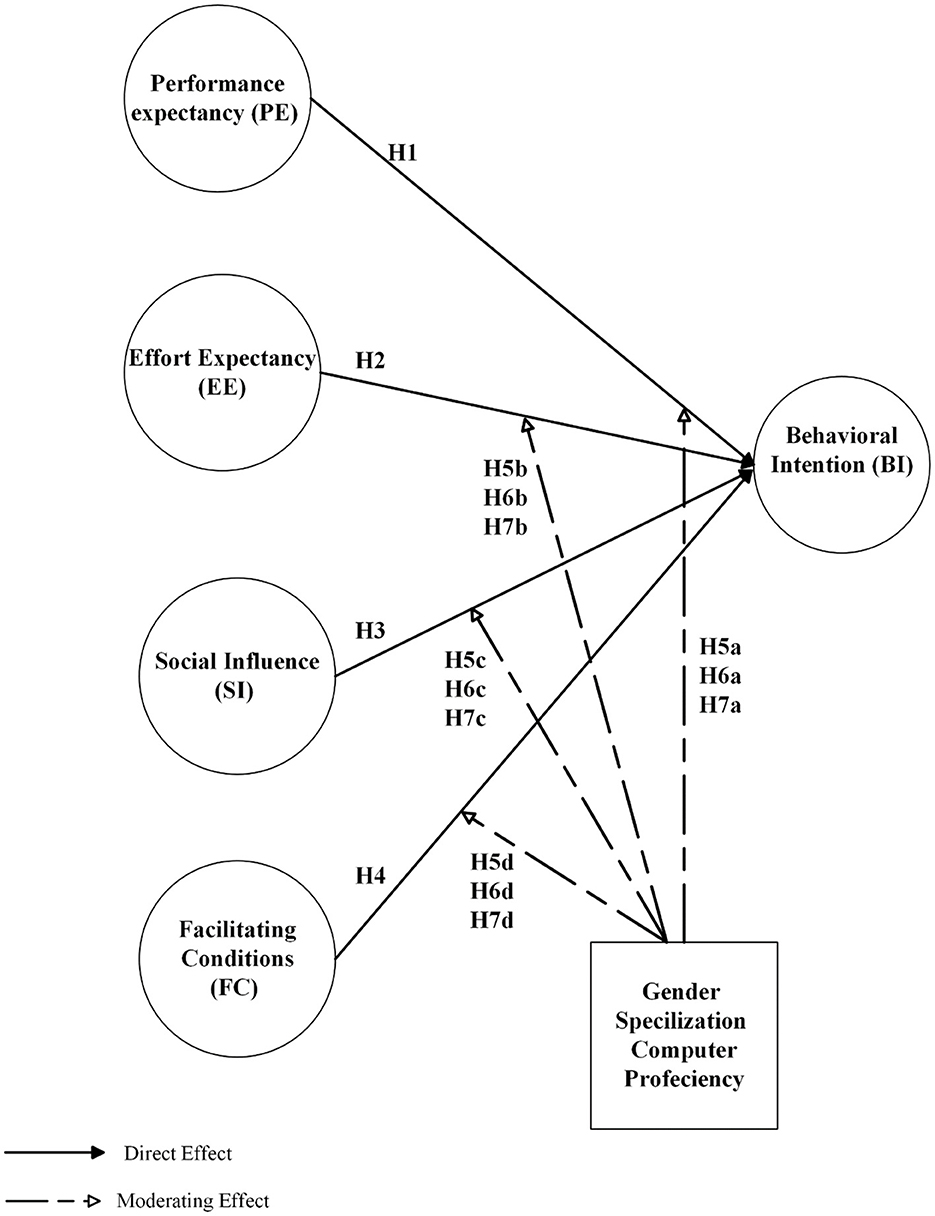

By situating these constructs and moderating variables within the context of generative AI adoption in a Saudi Arabian STEM student population, this study aims to extend theoretical understanding and provide culturally responsive insights for effective AI integration in higher education (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model based on UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

3 Methodology

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional design using a structured questionnaire to examine the factors influencing STEM students' behavioral intention to adopt generative AI technologies in education. The study was guided by the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) framework, which has been widely applied in technology adoption research. A two-stage analytical procedure was used to analyze the data using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), conducted through SmartPLS 4.0.

3.1 Sample

The target population consisted of STEM students enrolled at a public university in Saudi Arabia. An online questionnaire was distributed via institutional email, allowing participants to complete the survey at their convenience. This approach aimed to promote voluntary participation and candid responses. A total of 464 valid responses were collected for analysis.

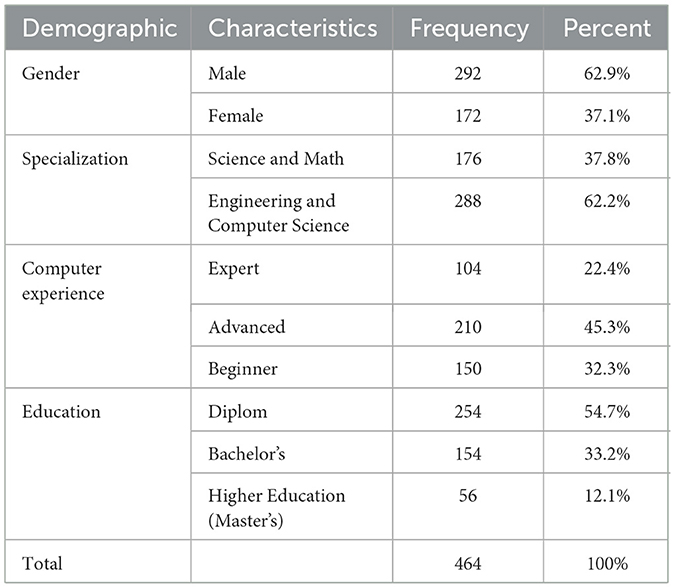

The demographic profile of the participants reflected a balanced sample in terms of gender, academic specialization, and experience. Of the respondents, 62.9% were male and 37.1% were female. Regarding specialization, 37.8% were from Science and Mathematics, while 62.2% were from Engineering and Computer Science. In terms of academic experience, 22.4% were experts, 45.3% were advanced, and 32.3% were beginners. As for educational qualifications, 54.7% held a diploma, 33.2% had a bachelor's degree, and 12.1% held a master's or doctorate (see Table 1).

3.2 Data collection and instrument design

Data were collected through a structured online questionnaire adapted from the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) and its extended model, UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al., 2003, 2012). The instrument was designed to evaluate key determinants of generative AI adoption among STEM university students in higher education.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Scientific Research Committee at a public university in Saudi Arabia (Approval No. SCBR-525/2025) on August 24, 2025. Data collection took place between August 25 and September 2, 2025. Before participation, all respondents provided informed consent electronically. The questionnaire was administered through the institutional students' email to ensure confidentiality and academic integrity.

The questionnaire consisted of two primary sections:

• The first section captured demographic data, including gender, academic specialization, educational level, and self-assessed computer proficiency.

• The second section assessed five core UTAUT constructs: performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), facilitating conditions (FC), social influence (SI), and behavioral intention (BI) to use generative AI in academic settings.

These constructs were measured using 18 items, rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Creswell and Creswell, 2017). The instrument was reviewed to ensure construct validity and alignment with the study's research objectives and theoretical framework. A complete list of items is provided in Appendix 1.

3.3 Data analysis

To validate the proposed research model and examine the relationships among UTAUT constructs, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was applied using SmartPLS version 4.0. PLS-SEM is particularly suitable for analyzing complex models involving latent constructs and moderation effects. It has been extensively used in recent educational technology research due to its predictive capability and ability to generate robust results from small to medium sample sizes (Abreh et al., 2025; Hair et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2025; Lakulu et al., 2025).

The analysis followed a structured two-stage procedure, consistent with established PLS-SEM guidelines:

Stage 1: measurement model assessment

The measurement model was evaluated to determine the reliability and validity of the latent constructs:

• Internal consistency reliability was confirmed through Cronbach's alpha and Composite Reliability (CR), with all values exceeding the 0.70 threshold.

• Convergent validity was assessed using Average Variance Extracted (AVE), with all constructs reporting AVE values above 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

• Discriminant validity was examined using both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio. The results showed that the square roots of AVEs were greater than inter-construct correlations, and HTMT values were all below 0.90, confirming adequate discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015).

Stage 2: Structural Model Assessment

The structural model was then analyzed to test the hypothesized relationships between the UTAUT constructs:

• Path coefficients, t-values, and p-values were obtained through a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples.

• The model's explanatory power was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2).

• Effect sizes (f2) and predictive relevance (Q2) were calculated to evaluate the relative impact and predictive capability of each path.

To complement the structural analysis, descriptive statistics were computed using SPSS (Version 25) to profile the demographic characteristics of the sample and assess its representativeness. The data demonstrated an approximately normal distribution, supporting the appropriateness of the statistical procedures employed.

4 Results

4.1 A pilot testing

A pilot study was conducted with a sample of 40 students to evaluate the preliminary reliability of the questionnaire. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed among the items corresponding to each latent construct. All coefficients exceeded 0.70, indicating satisfactory internal consistency and suggesting that the instrument demonstrated acceptable initial reliability.

4.2 Assisting the measurement model

The evaluation of the measurement model involves establishing its validity and reliability (Hair et al., 2022). Convergent and discriminant validity are used to assess the validity of the measurement model.

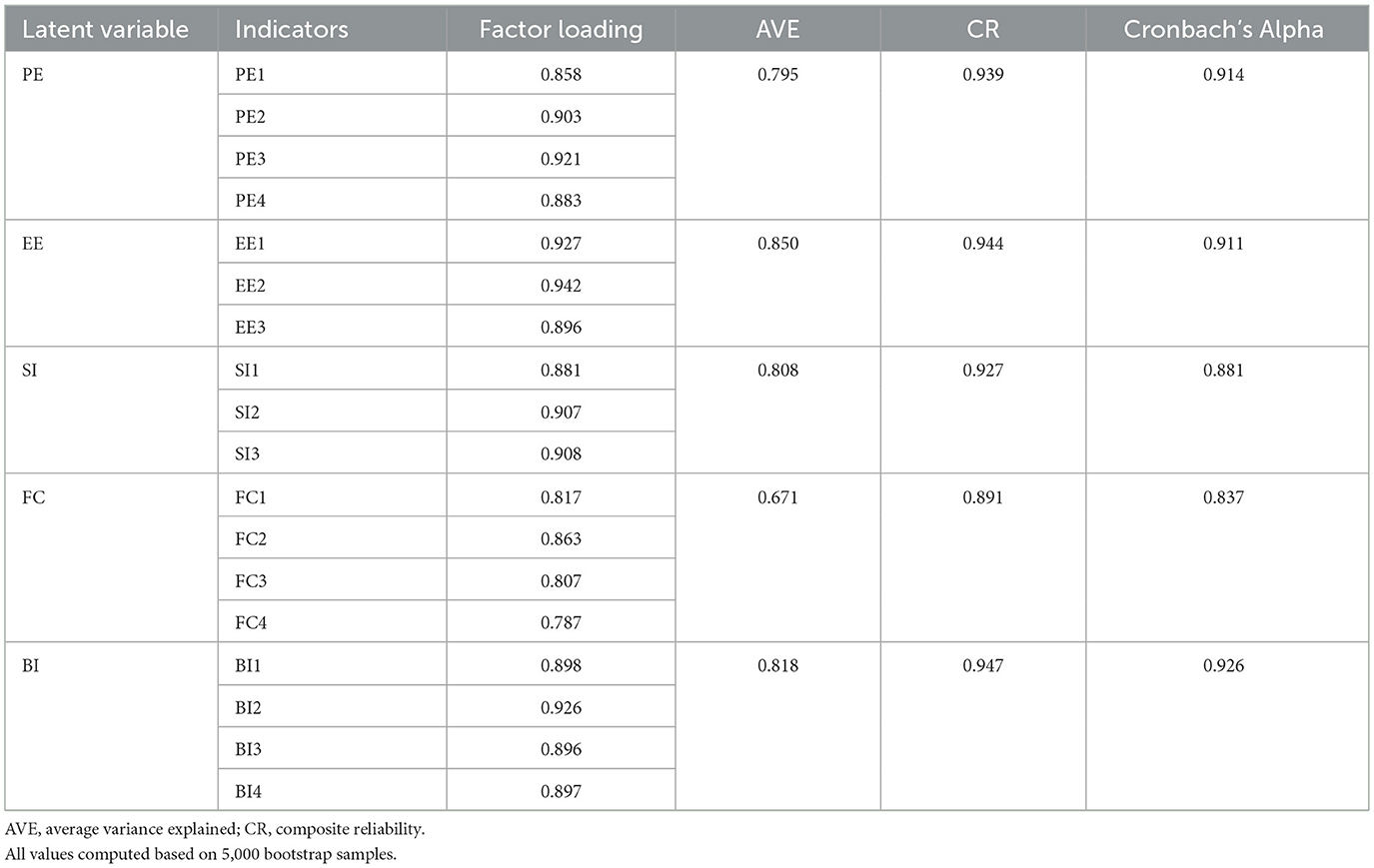

• As shown in Tables 2, 3, the values of the standardized factor loading measuring the underlying constructs exceeded the threshold value of 0.70, confirming indicator reliability and convergent validity. Furthermore, the values of the average variance explained (AVE) surpassed the minimum cutoff point of 0.50 across all latent variables. Hence, this study established convergent validity for each latent variable.

• As for reliability assessment, the results shown in Table 3 indicate that the values of both composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach's alpha exceeded the minimum acceptable value of 0.70 for internal consistency reliability across all latent variables. Therefore, the reliability of all latent variables was established.

• Table 4 shows the results of the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) and the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which were used for discriminant validity assessment. Using HTMT, all values were below the cut-off value of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015). Moreover, the Fornell-Larcker method indicated that none of the off-diagonal correlations exceeded the square root of the AVE, confirming the discriminant validity of the latent variables. Thus, the discriminant validity of all latent variables was established.

4.3 Assessment of the structural model

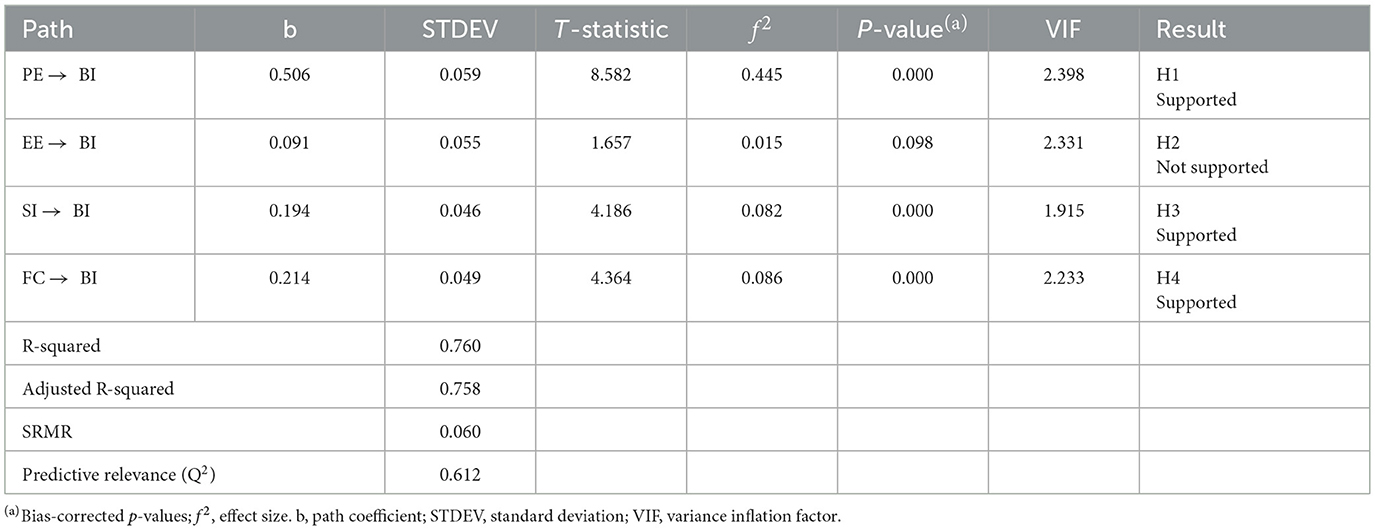

The initial step is to assess the presence of multicollinearity among the exogenous constructs, which occurs when two exogenous latent variables are highly correlated or when their variance inflation factor (VIF) exceeds the threshold value of 5.00, or ideally, remains below 3.00 (Hair et al., 2019). The study employs a standard PLS model and then evaluates the values of VIF for the exogenous variables, presenting the results in Table 5. The results reveal that none of the VIFs exceeded 3.0, confirming the absence of this problem.

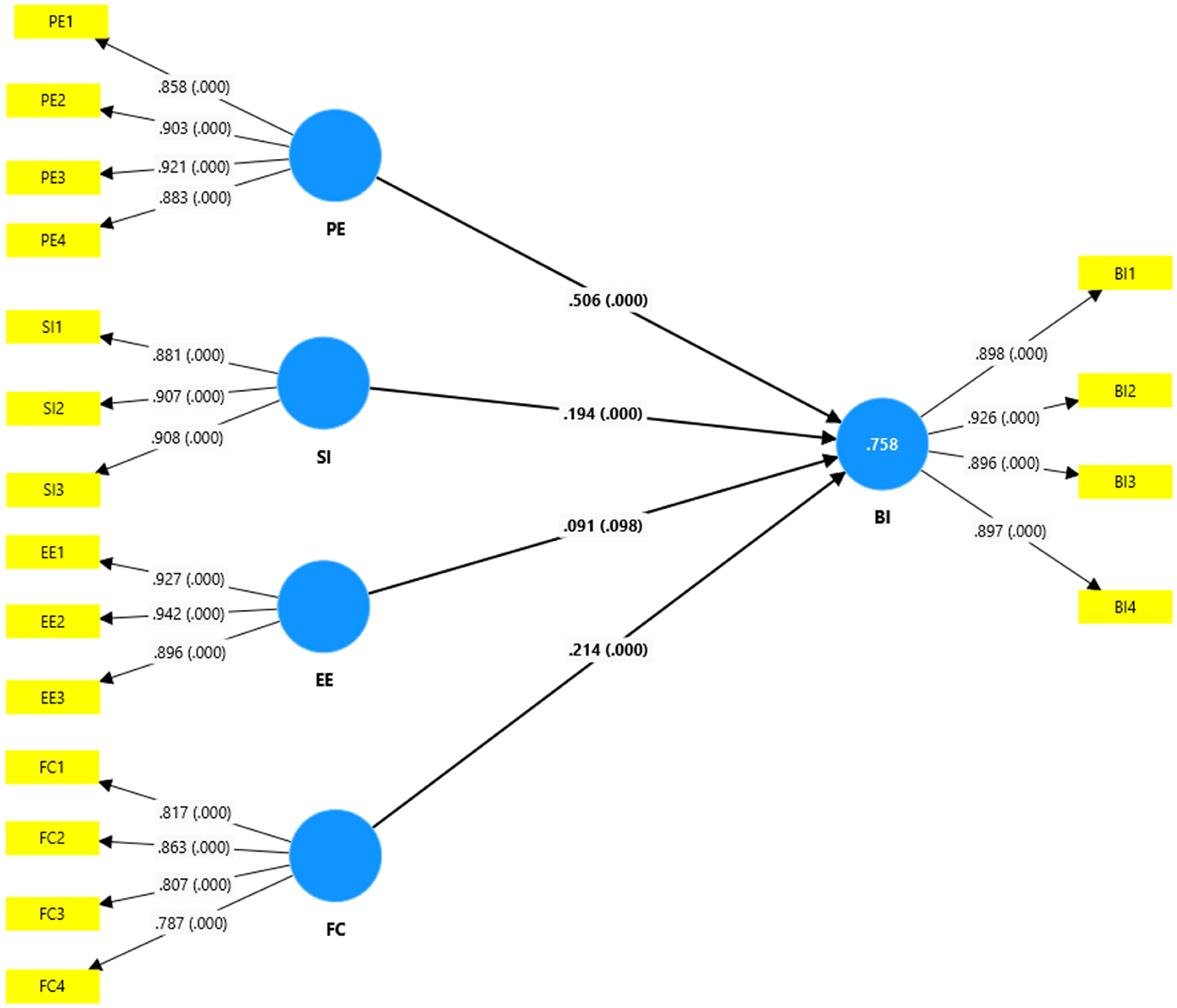

Once the absence of multicollinearity was confirmed, the study employed a PLS-SEM with a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (with 5,000 samples) to estimate the path coefficients and assess their significance. However, before examining the study hypotheses, it is important to evaluate the goodness of fit of the structural model (Hair et al., 2022). The goodness of fit of the structural model was assessed using the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), the coefficient of determination (R2), and the cross-validated redundancy measure, also known as predictive relevance (Q2). As displayed in Table 5, the structural model exhibits a good fit, as evidenced by an SRMR value of 0.060, which is below the recommended threshold of 0.08 (Henseler et al., 2014). Furthermore, the adjusted R2 value of 0.758 indicates that the structural model has strong explanatory power, accounting for a significant proportion of variance in BI (Hair et al., 2022). The Q2 value of 0.612 confirms that the model possesses predictive validity (Falk and Miller, 1992). These findings highlight the validity of the structural model. The estimated structural model is illustrated in Figure 2, which reports the standardized factor loadings and path coefficients along with their respective p-values.

Figure 2. The structural model for the direct effects, based on UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

4.4 Direct hypothesis testing

The results presented in Table 5 indicate a statistically significant and direct relationship between PE and BI (β = 0.506, t-statistic = 8.582, p-value = 0.000). As PE increases by one standard deviation, BI increases by 0.506 standard deviations. The effect size of 0.445 indicates a moderate effect of PE on BI (Hair and Alamer, 2022). Therefore, the findings provide strong evidence to support the acceptance of the first hypothesis (H1). However, the empirical analysis yields an insignificant effect of EE on BI, demonstrating that no relationship between EE and BI (b = 0.091, t-statistic = 1.657 <1.96, p-value = 0.098 > 0.05). Therefore, the second hypothesis (H2) is not supported.

The findings of this study also reveal a statistically significant and positive effect of SI on BI, with an estimated standardized path coefficient of 0.194 (t-statistic = 4.186, p-value = 0.000 <0.05). Meanwhile, its effect size is 0.082, which signifies a modest effect (Hair and Alamer, 2022). Hence, the third hypothesis (H3) of this study is strongly supported, indicating a positive linkage between the SI and BI among students in Saudi Arabia. This result highlights that a one-standard-deviation increase in SI corresponds to a 0.194-standard-deviation increase in BI. Likewise, the results demonstrate that the effect of FC was positive, with a standardized path coefficient of 0.214. This estimated coefficient was statistically significant because it was associated with a t-statistic of 4.364 > 1.96 and a p-value = 0.000 <0.05. The effect size was 0.086, signifying a modest effect of FC on BI (Hair and Alamer, 2022). This finding supports the fourth hypothesis (H4), confirming that general education students in Saudi Arabia perceived that FC positively impacted their perceived BI toward including AI technology in education. BI increases by 0.214 standard deviations with a one standard deviation increase in FC.

4.5 Results of moderation testing

The moderating effects of gender, specialization, and computer experience are examined using multi-group analysis (MGA). This approach is appropriate when the moderator is a categorical variable rather than a continuous one (Hair et al., 2022; Sarstedt et al., 2011). Using this approach, the data is divided into distinct groups (e.g., male vs. female), allowing for a direct comparison of structural path coefficients across groups (Hair et al., 2022). The researcher employs a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 samples. Accordingly, a moderation effect is considered significant if the differences in the path coefficients are statistically significant across the categories of the moderator variable (Henseler, 2007; Sarstedt et al., 2011).

4.5.1 Moderation effect of gender

The moderating effect of gender is examined by conducting separate PLS-SEM models for male and female samples through assessing the significance of the difference between the two estimated coefficients for males and females in MGA. The results are shown in Table 6. The results indicated that none of the relationships are significantly moderated by gender (p-values > 0.05). These findings do not support the first part of the fifth hypothesis (H5a). More specifically, none of the sub-hypotheses (H5a, H5b, H5c, and H5d) are supported, indicating that the effects of PE, EE, SI, and FC on BI did not differ significantly by gender.

4.5.2 Moderation effect of specialization

Similarly, this study examines the moderating effect of specialization (Science vs. Engineering) on the relationships between PE, EE, SI, and FC, on the one hand, and BI, on the other. The results of the MGA displayed in Table 7 revealed that the effect of PE on BI was significantly stronger among engineering and computer science students (βECS = 0.625) than among science and mathematics students (βSM = 0.419), with the difference reaching statistical significance (difference in β = −0.205, p-value = 0.047 <0.05). This finding supports H6a and suggests that students in computer science and engineering have a more positive perception of the expected performance benefits of AI technologies, which in turn influences their intention to adopt them. Conversely, the moderating effects of specialization are not significant for the other UTAUT predictors, including EE (Δ β = 0.197, p-value = 0.723), SI (Δβ = 0.141, p-value = 0.064), and FC (Δβ = −0.037, p-value = 0.102). These results provided strong evidence that did not support H6b, H6c, and H6d.

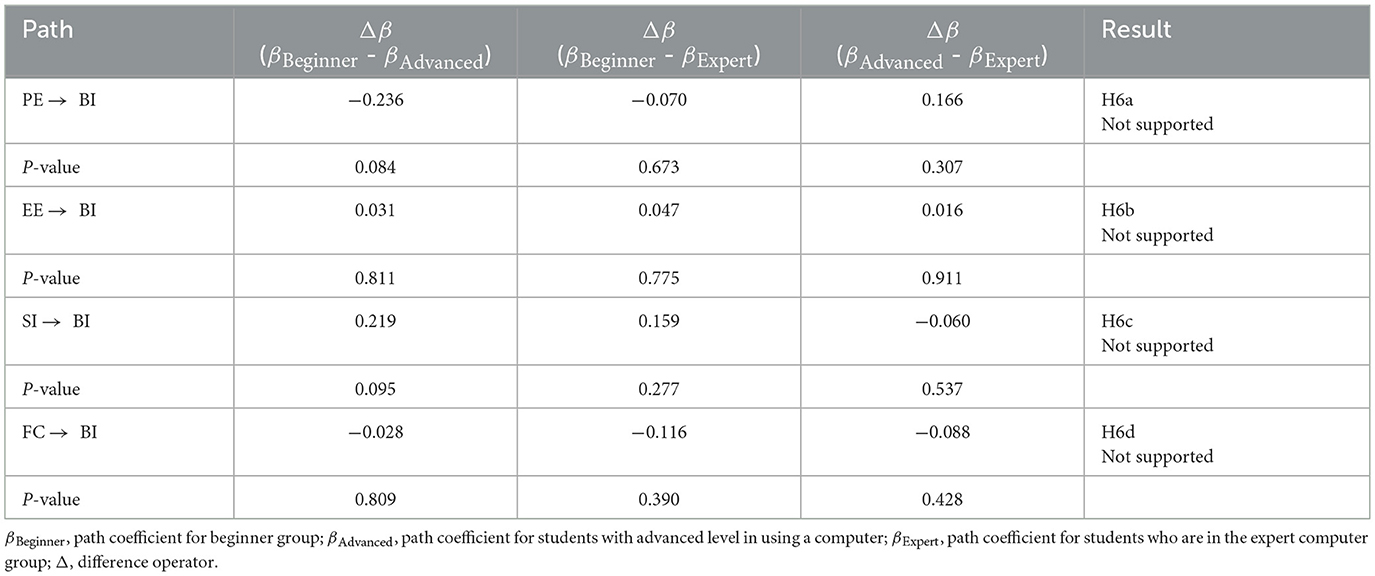

4.5.3 Moderation effect of computer experience

The results of the MGA are shown in Table 8, which indicates that the level of computer experience did not impact the perceived PE, EE, SI, and FC on the BI perception among students in Saudi Arabia. Hence, the study provides strong evidence that does not support H7a, H7b, H7c, and H7d. Accordingly, the direct links between UTAUT variables and BI do not vary by the level of computer proficiency.

5 Discussion

This study investigated the behavioral intention of undergraduate STEM students in Saudi Arabia to adopt generative AI for academic purposes, applying the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) as the theoretical framework. The findings offer both theoretical and practical insights, highlighting how core UTAUT constructs, performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI), and facilitating conditions (FC).

5.1 Performance expectancy as a dominant predictor

Consistent with prior research (e.g., Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Hsieh and Chiu, 2019), performance expectancy emerged as the strongest and most significant predictor of behavioral intention (β = 0.506, p < 0.001). Also, this aligns with findings from other UTAUT-based studies in diverse STEM contexts, such as Devi et al. (2025), Du et al. (2025), and Kumar et al. (2025), all of which highlight the centrality of performance-related perceptions in driving AI adoption. This finding reinforces the notion that students are most inclined to adopt AI tools when they perceive tangible academic benefits, such as improved understanding, efficiency, or academic performance. The moderate effect size (f2 = 0.445) indicates that performance-related beliefs are not only statistically significant but practically impactful in shaping students‘ technology adoption behaviors. These results corroborate theoretical assumptions within UTAUT and empirical studies in similar educational contexts (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Deng et al., 2023; Hsieh and Chiu, 2019; Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2023). In STEM and AI adoption contexts, numerous studies report similar findings: for example, Du et al. (2025) found that performance expectancy (alongside hedonic motivation and price value) significantly predicted mathematics teachers' intention to use AI in China. Similarly, Lakulu et al. (2025) observed that performance expectancy strongly influenced the adoption of AI-powered mobile learning among Malaysian students.

However, there is variation. Ateş and Gündüzalp (2025) integrated UTAUT2 and GETAMEL frameworks and found that enjoyment, self-efficacy, anxiety, and experience mediated or moderated the influence of perceived usefulness. That suggests that in some contexts, performance expectancy alone may not fully explain intention, and other psychological or contextual factors play a stronger role. In our study's context, the strong predictive power of PE might partly reflect the high relevance of AI to STEM fields, or may be strengthened by students' prior exposure to technologically rich environments.

Additionally, the finding that performance expectancy had a stronger influence on behavioral intention among engineering and computer science students compared to those in science and mathematics aligns with existing research highlighting the role of academic specialization in shaping technology adoption. Han and Guo (2025), for example, reported that STEM students tend to place greater emphasis on perceived usefulness than their non-STEM counterparts. This supports the disciplinary relevance hypothesis, which suggests that students in fields more directly engaged with technology are more likely to recognize and value the performance benefits of AI tools (Kersten and Pape, 2024; Hsieh and Chiu, 2019). These results point to the importance of tailoring AI integration strategies to the specific needs and expectations of different academic disciplines within STEM education.

5.2 The limited role of effort expectancy

A striking and somewhat unexpected finding in this study is that effort expectancy (EE) did not significantly predict behavioral intention to adopt generative AI tools among Saudi STEM undergraduates (β = 0.091, p = 0.098). This result contrasts with several prior studies, where EE played a meaningful role in shaping technology adoption—particularly in populations with lower digital fluency or more limited exposure to emerging technologies (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Ateş and Gündüzalp, 2025; Devi et al., 2025; Mohamad Mozie et al., 2025). For example, in a study on gamified STEM learning in Kuwait, Aljamaan et al. (2025) found that effort expectancy significantly influenced students' learning enjoyment, which in turn shaped behavioral intention. Similarly, Devi et al. (2025) reported that effort expectancy was a critical determinant among women in STEM in India, suggesting the salience of ease-of-use perceptions in contexts where confidence or familiarity with digital tools may vary.

However, the findings align more closely with studies that emphasize the contextual and domain-specific nature of EE. Han and Guo (2025), for instance, found that effort expectancy had a stronger influence on non-STEM students than on STEM students, implying that those with greater technical exposure perceive AI tools as inherently less difficult to use. Du et al. (2025) and Lakulu et al. (2025) also highlighted how EE's significance can diminish in settings where users are technically proficient or accustomed to using complex educational technologies. These studies suggest that technical familiarity and disciplinary background are crucial moderators of EE's predictive power.

In the current context, several factors may explain the diminished role of EE. First, Saudi STEM students generally demonstrate a high level of digital literacy and routine interaction with technical systems, reducing the perceived effort associated with adopting generative AI. Technologies that may seem daunting to less digitally inclined users are likely viewed as manageable—or even intuitive—by this population. Second, many generative AI tools have matured significantly in usability, often featuring user-friendly, conversational interfaces that lower the threshold for engagement without requiring deep technical training. Third, institutional and cultural factors, such as mandated digital skill development, integration of AI tools in coursework, or the presence of robust IT support, may have further alleviated any perceived barriers to use.

Notably, the absence of significant moderating effects by gender, specialization, or computer experience reinforces the conclusion that ease of use may no longer serve as a differentiating factor within this user group. In other words, EE may have become a baseline expectation among digitally fluent learners rather than a driver of adoption—assumed rather than actively evaluated. This finding further contributes to the growing body of research that challenges the generalizability of EE as a universally important factor within the UTAUT model (Kumar et al., 2025; Sarstedt et al., 2011).

Ultimately, this divergence highlights the need for context-sensitive interpretations of UTAUT constructs. While EE remains important in certain environments, especially those involving novice users, marginalized groups, or non-STEM disciplines, its relevance may decline in high-tech, high-competence contexts where digital tools are seen as standard components of academic life.

5.3 The role of social influence and facilitating conditions

Social influence (SI) had a statistically significant but modest effect on behavioral intention (β = 0.194, p < 0.001; f2 = 0.082), consistent with recent findings that emphasize the situational and cultural variability of this construct (Plageras et al., 2023; Kersten and Pape, 2024). In the Saudi context, where collective norms, authority figures, and institutional expectations may play a stronger role than in more individualistic societies, the impact of peers, instructors, and university messaging emerges as a meaningful, albeit secondary, influence on students' adoption of generative AI. This finding is echoed in other culturally similar contexts; for example, Abreh et al. (2025) reported that subjective norm and perceived social good were significant predictors of AI learning intentions among STEM students in Ghana. These parallels highlight how social conformity and perceived collective benefit can meaningfully shape students' behavioral intentions in regions with strong communal values.

Similarly, facilitating conditions (FC) showed a significant yet modest influence on behavioral intention (β = 0.214, p < 0.001; f2 = 0.086), emphasizing the importance of technological infrastructure, institutional support, and resource availability. This finding aligns with a wide body of literature emphasizing institutional readiness as a core enabler of AI adoption in higher education (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024; Kumar et al., 2025; Mohamad Mozie et al., 2025; Truong and Pham, 2025). Notably, facilitating conditions did not vary significantly across gender, specialization, or computer experience in this study—suggesting that adequate access to infrastructure and support is relatively evenly distributed among Saudi STEM students.

Comparable results have been found in other national contexts. For instance, studies in India (Kumar et al., 2025), Malaysia (Lakulu et al., 2025), and Turkey (Ateş and Gündüzalp, 2025) also confirm that institutional support systems, digital access, and user guidance are cross-cutting determinants of successful technology integration. Together, these findings underscore that while SI and FC may not be the strongest predictors, they are nonetheless essential elements of a supportive educational environment that fosters AI adoption—particularly in contexts with emerging or evolving digital ecosystems.

5.4 Moderation by demographics: limited but specific

The current study found limited moderating effects of demographic variables on technology acceptance, with only academic specialization significantly influencing the relationship between performance expectancy (PE) and behavioral intention (BI). This aligns with prior research by Truong and Pham (2025) and Mohamad Mozie et al. (2025), who observed minimal gender differences in technology acceptance in digitally fluent contexts. The absence of significant moderation by gender or computer experience likely reflects a baseline level of digital competence among STEM students, reducing variability in perceived technological barriers. In contrast, the significant moderation by academic specialization supports findings by Han and Guo (2025), who noted substantial variation in AI adoption across STEM sub-disciplines. This pattern emphasizes the influence of domain-specific relevance in shaping students' perceptions of generative AI's utility, reinforcing arguments by Ateş and Gündüzalp (2025), Du et al. (2025), and Flores-Alonso et al. (2023) regarding the importance of context-sensitive implementation and the recalibration of traditional technology acceptance predictors based on disciplinary needs.

5.5 Implications for practice

The results of this study have several important implications for educators, institutions, and policymakers:

• Focus on demonstrating performance benefits: To increase generative AI adoption, institutions should highlight how these tools directly support academic performance, such as improving understanding of complex STEM topics, enhancing problem-solving skills, or enabling more efficient study practices.

• Tailor implementation by discipline: Since the perceived usefulness of AI varies across STEM specializations, AI adoption strategies should be customized to align with the unique needs and expectations of each academic field.

• Enhance institutional support: While facilitating conditions had only a modest effect, their significance confirms the necessity of adequate technological infrastructure, training, and institutional endorsement to encourage widespread adoption.

• Leverage social influence strategically: Institutional and peer encouragement can play a meaningful role in influencing adoption, especially in culturally collective societies. Initiatives such as peer-led workshops or faculty showcases could enhance the social legitimacy of AI use in learning.

5.6 Theoretical contributions

This study contributes to the growing body of literature applying the UTAUT model in educational settings by:

• Validating UTAUT, STEM-focused university context, thereby enhancing its cross-cultural applicability.

• Demonstrating that performance expectancy remains the most robust predictor of AI adoption intentions in higher education.

• Revealing nuanced insights into the role of academic specialization, suggesting that perceived benefits of AI tools vary significantly depending on disciplinary context.

• Challenging the relevance of effort expectancy and demographic moderators in contexts with high digital literacy.

5.7 Limitations and future research

Despite the valuable insights offered by this study, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the use of a cross-sectional research design restricts the ability to draw causal inferences regarding the relationships between the UTAUT constructs and STEM students' behavioral intention. Longitudinal studies are recommended to capture the dynamic evolution of students‘ perceptions and usage behaviors over time.

Second, the study was conducted at a single university in Saudi Arabia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider incorporating more diverse institutional settings, both within the region and internationally, to capture broader cultural, institutional, and disciplinary variations in AI adoption among STEM students.

Third, while the UTAUT model offered a robust theoretical foundation, it may not fully capture the complexity of STEM students' decision-making processes regarding emerging technologies. Integrating additional constructs such as perceived risk, perceived enjoyment, or AI self-efficacy may enhance explanatory power and provide a more nuanced understanding of students' attitudes toward generative AI.

Furthermore, future studies could extend the current framework by examining how UTAUT factors relate to global trends in online learning, lifelong learning, and continuous professional development, particularly as AI tools become increasingly integrated into digital and remote education platforms.

Finally, employing a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative techniques such as interviews or focus groups with quantitative surveys, would offer a more comprehensive perspective. This would allow researchers to triangulate findings, deepen contextual understanding, and capture the subjective experiences and motivations underlying students' adoption behaviors.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported via funding from Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, project number PSAU/2025/R/1446.

Acknowledgments

The author extends sincere appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for supporting and funding this research work through project number PSAU/2025/2/37034.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abreh, M. K., Arthur, F., Akwetey, F. A., and Nortey, S. A. (2025). Modelling STEM students' intention to learn artificial intelligence (AI) in Ghana: a PLS-SEM and fsQCA approach. Discover Artif. Intell. 5:223. doi: 10.1007/s44163-025-00466-8

Acosta-Enriquez, B. G., Farroñan, E. V. R., Zapata, L. I. V., Garcia, F. S. M., Rabanal-León, H. C., Angaspilco, J. E. M., et al. (2024). Acceptance of artificial intelligence in university contexts: a conceptual analysis based on UTAUT2 theory. Heliyon 10:e38315. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38315

Aithal, P. S. (2025). Holistic education redefined: integrating STEM with arts, environment, spirituality, and sports through the seven-factor/Saptha-Mukhi student development model. PIJMESS 2, 1–52. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.14722931

Aljamaan, A., Alsaber, A., Emmanuel, C., and Alkandari, A. (2025). Leveling up learning effectiveness in STEM education through gamification: an empirical study on behavioral intention and digital literacy among undergraduate students in Kuwait. Front. Educ. 10:1586466. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1586466

Ateş, H., and Gündüzalp, C. (2025). Proposing a conceptual model for the adoption of artificial intelligence by teachers in STEM education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 33, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2025.2457350

Chasokela, D., and Moyo, F. (2025). “Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics learning technology implementation to address 21st-century skills: the Zimbabwean higher education context,” in Insights into International Higher Education Leadership and the Skills Gap, eds. M. Kayyali, and B. Christiansen (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 319–344. doi: 10.4018/979-8-3693-3443-0.ch013

Chen, X., Zou, D., Xie, H., Cheng, G., and Liu, C. (2022). Two decades of artificial intelligence in education. Educ. Technol. Soc. 25, 28–47. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11209-y

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Deng, P., Chen, B., and Wang, L. (2023). Predicting students' continued intention to use E-learning platform for college English study: the mediating effect of E-satisfaction and habit. Front. Psychol. 14:1182980. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1182980

Devi, M. G. S., Sivashanmugam, N., Dhanalakshmi, H. S., Rupa, H. S., and Lakshmi, M. K. (2025). Analyzing factors influencing digital technology adoption among women in STEM: a UTAUT2 model perspective from India. Cuestiones de Fisioterapia 54, 7891–7904. doi: 10.48047/CU

Du, W., Cao, Y., Tang, M., Wang, F., and Wang, G. (2025). Factors influencing AI adoption by Chinese mathematics teachers in STEM education. Sci. Rep. 15:20429. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-06476-x

Falk, R. F., and Miller, N. B. (1992). A Primer for Soft Modeling. Akron: University of Akron Press.

Flores-Alonso, S. I., Diaz, N. V. M., Kapphahn, J., Mott, O., Dworaczyk, D., Luna-García, R., et al. (2023). “Introduction to AI in undergraduate engineering education,” in 2023 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (Piscataway, NJ: IEEE). Available online at: https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10568306 (Accessed July 17, 2025).

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D.F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 18, 382–388. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800313

Hair, J., and Alamer, A. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Ling. 1:100027. doi: 10.1016/j.rmal.2022.100027

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2022). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7

Han, F., and Guo, J. (2025). How does university students' academic major (STEM vs. non-STEM) affect their acceptance of e-learning: a multi-group analysis. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Higher Educ. 22:41. doi: 10.1186/s41239-025-00543-z

Henseler, J. (2007). “A new and simple approach to multi-group analysis in partial least squares path modeling,” in Proceedings of the PLS'07 International Symposium, eds. H. Martens, and T. Næs (CAPE Town: SAS Institute), 104–107.

Henseler, J., Dijkstra, T. K., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., Diamantopoulos, A., Straub, D. W., et al. (2014). Common beliefs and reality about PLS: comments on R€onkk€o and evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 17, 182–209. doi: 10.1177/1094428114526928

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hillmayr, D., Ziernwald, L., Reinhold, F., Hofer, S. I., and Reiss, K. M. (2020). The potential of digital tools to enhance mathematics and science learning in secondary schools: a context-specific meta-analysis. Comp. Educ. 153:103897. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103897

Hsieh, C. C., and Chiu, F. Y. (2019). “The UTAUT model applied to examine the STEM in high school robot subject instruction,” in International Congress on Education and Technology in Sciences (Cham: Springer), 36–46. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-45344-2_4

Kersten, P., and Pape, M. M. (2024). “AI chatbots in university courses from the perspective of first semester STEM students,” in EDULEARN24 Proceedings (Palma, Spain: IATED), 945–952. doi: 10.21125/edulearn.2024.0337

Krasovskiy, D. (2020). The challenges and benefits of adopting AI in STEM education. Available online at: https://upjourney.com/the-challenges-and-benefits-of-adopting-ai-in-stem-education (Accessed July 17, 2025).

Kumar, M., Tyagi, R., Gaumat, A., and Rani, J. (2025). Students' perceptions and readiness for AI-enhanced learning: a Utaut-based study in Indian higher education institutions. J. Mark. Soc. Res. 2, 495–500. doi: 10.61336/jmsr/25-03-61

Lakulu, M. M., Izkair, A. S., Harfiez Abdul Muttalib, M. F., and Zainuddin, N. A. (2025). Understanding AI and mobile learning adoption in malaysian universities: a UTAUT-based model. Int. J. Interact. Mobile Technol. 19, 80–111. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v19i11.52977

McLaren, B. M., Scheuer, O., and Mikšátko, J. (2010). Supporting collaborative learning and e-discussions using artificial intelligence techniques. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 20, 1–46. doi: 10.3233/JAI-2010-0001

Mohamad Mozie, N., Ghazali, N., and Ali Husin, L. I. (2025). Adopting artificial intelligence in higher education: insights from the UTAUT framework on student intentions. Adv. Bus. Res. Int. J. 11, 71–79. doi: 10.24191/abrij.v11i1.8641

O‘dea, X., and O'Dea, M. (2023). Is artificial intelligence really the next big thing in learning and teaching in higher education? A conceptual paper. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 20, 1–17. doi: 10.53761/1.20.5.06

Plageras, A., Kalovrektis, K., Xenakis, A., and Vavougios, D. (2023). “The application of TPACK in the methodology of the flipped classroom and with the evaluation of the UTAUT to measure the impact of stem activities in improving the understanding of concepts of applied sciences,” in EDULEARN23 Proceedings (Palma, Spain: IATED), 569–575. doi: 10.21125/edulearn.2023.0243

Romero-Rodríguez, J. M., Ramírez-Montoya, M. S., Buenestado-Fernández, M., and Lara-Lara, F. (2023). Use of ChatGPT at university as a tool for complex thinking: students' perceived usefulness. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 12, 323–339. doi: 10.7821/naer.2023.7.1458

Sarstedt, M., Henseler, J., and Ringle, C. M. (2011). Multi-group analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: alternative methods and empirical results. Adv. Int. Mark. 22, 195–218. doi: 10.1108/S1474-7979(2011)0000022012

Scherer, R., and Teo, T. (2019). Editorial to the special section-Technology acceptance models: what we know and what we (still) do not know. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 50, 2387–2393. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12866

Shin, D. (2020). User perceptions of algorithmic decisions in the personalized AI system: perceptual evaluation of fairness, accountability, transparency, and explainability. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 64, 541–565. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2020.1843357

Suhail, F., Adel, M., Al-Emran, M., and AlQudah, A. A. (2024). Are students ready for robots in higher education? Examining the adoption of robots by integrating UTAUT2 and TTF using a hybrid SEM-ANN approach. Technol. Soc. 77:102524. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102524

Sungur Gül, K., and Ateş, H. (2023). An examination of the effect of technology-based STEM education training in the framework of technology acceptance model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 8761–8787. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11539-x

Truong, V. L., and Pham, L. P. C. (2025). Determinants of adopting 3D technology integrated with artificial intelligence in STEM higher education: a UTAUT2 model approach. Comp. Appl. Eng. Educ. 33:e70019. doi: 10.1002/cae.70019

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q. 27, 425–478. doi: 10.2307/30036540

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., and Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 36, 157–178. doi: 10.2307/41410412

Xu, W., and Ouyang, F. (2022). The application of AI technologies in STEM education: a systematic review from 2011 to 2021. Int. J. STEM Educ. 9:59. doi: 10.1186/s40594-022-00377-5

Yusuf, A., Pervin, N., and Román-González, M. (2024). Generative AI and the future of higher education: a threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Higher Educ. 21:21. doi: 10.1186/s41239-024-00453-6

Appendix 1

Part One: Demographic Information:

Gender: Male - Female

Field of Specialization: Administrative/Educational/Health/ Scientific/Engineering (including engineering and computer engineering)

Academic Level: First/Second/Third/Fourth/Fifth/Sixth/Seventh/ Eighth

Academic Level: Diploma/Bachelor's/ Master's

Computer Experience: Beginner - Advanced - Expert

Part Two: Factors Influencing Students' Behavioral Intention to Use Generative AI in Education

Strongly Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree Items

Axis 1: Expected Performance

1. I believe that generative AI will increase my ability to complete tasks and assignments.

2. I believe that generative AI will help me obtain important information during my learning.

3. I believe that generative AI will increase my academic productivity.

4. I believe that generative AI will benefit my overall learning.

Axis 2: Expected Effort

1. I believe that it will be easy to master using Generative AI in My Learning.

2. I think it will be easy for me to become proficient in using generative AI.

3. I think it will be easy for me to become proficient in using generative AI applications.

Axis 3: Social Influence

1. My teacher and peers believe I should use generative AI in my learning.

2. People I influence believe I should use generative AI in my learning.

3. People whose opinions I care about support my use of generative AI in my learning.

Axis 4: Facilitating Factors

1. I have the necessary resources (computer, internet, etc.) to use generative AI in my learning.

2. The devices I currently use in my learning are compatible with generative AI.

3. I receive appropriate technical support when I encounter a problem related to using generative AI in my learning.

4. I have the necessary knowledge to use generative AI in my learning.

Axis 5: Behavioral Intention to Use Generative AI

1. I intend to use generative AI in the near future.

2. I plan to use generative AI in my learning over the coming months.

3. I will seek to use generative AI in my learning when I have the opportunity.

4. I expect to use generative AI in my learning shortly.

Keywords: behavioral intention, generative AI, higher education, STEM, technology adoption, UTAUT

Citation: BinJwair A (2025) Predicting STEM students' adoption of generative AI in academic contexts: an application of the UTAUT model. Front. Educ. 10:1669750. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1669750

Received: 22 July 2025; Accepted: 31 October 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Xiang Hu, Renmin University of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Leonidas Gavrilas, University of Ioannina, GreeceAbdullahi Yusuf, Sokoto State University, Nigeria

Heni Mulyani, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 BinJwair. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amani BinJwair, ZHIuYWFzajIwMDdAZ21haWwuY29t

Amani BinJwair

Amani BinJwair