- 1Community Psychosocial Research (COMPRES), North-West University, Mafikeng, South Africa

- 2Department of Psychology, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

Introduction: Spirituality has been recognized as a potential coping mechanism and source of strength for some students. However, its relationship with academic resilience remains underexplored, especially among South African students. This study aimed to explore the relationship between spirituality and academic resilience among university undergraduate students at a South African university.

Methods: A correlational research design was employed, using a web-based questionnaire that combined the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale and the Academic Resilience Scale-30, which included adaptive help seeking, academic reflecting, academic perseverance, negative affect and emotional response and academic reflecting. The Academic Resilience Framework was used as a guiding theoretical framework for this study, supported by theoretical perspectives on spirituality and self-transcendence theory. Data was collected from 420 North-West University undergraduate students, aged between 18 years and older, with stratified random sampling employed (post ad hoc) on the analysis. Data was analyzed using descriptive analysis and inferential analysis that included bivariate correlation, hierarchical multiple regression, and structural equation modeling to test the study’s hypotheses.

Results: The results of bivariate correlation indicated that spirituality was positively correlated with perseverance, help-seeking, and academic resilience total scores but negatively associated with negative effects. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis results also indicated a positive relationship between spirituality, academic perseverance, academic reflection, adaptive help-seeking, and academic resilience but a negative relationship with negative affect and emotional response. Furthermore, results showed a positive relationship between spirituality and academic resilience in females than in their male counterparts and a negative relationship in participants aged between 18 and 21.

Conclusion: The study concluded that there was a positive correlation between spirituality, academic perseverance, academic reflection, and adaptive help-seeking, and academic resilience; however, it was negatively associated with negative effects. It is important for universities and healthcare professionals working with the student population to consider an individual’s spiritual dimension in their programs.

1 Introduction

Academic resilience is narrowed in an educational context to understand the student’s ability to thrive and succeed despite facing academic adversities (Cassidy, 2016). Martin (2013) further conceptualized academic resilience as the capacity to overcome risks and obstacles that impede academic progress. More specifically, it encompasses the ability to achieve better academic outcomes following challenges such as academic failure. In this study, key behavioral aspects that capture the essence of academic resilience are explored. These include adaptive help seeking, academic reflecting, academic perseverance, reduced negative affect, and emotional response (Cassidy, 2016; Latif and Amirullah, 2020). Prior studies have identified key factors that hinders students’ resilience. These include inadequate resources, food insecurity, excessive workload, diminished motivation, maladaptive lifestyle choices, difficulties comprehending course material, challenges in completing assignments, poor adaptation to academic demands, and ineffective study habits, low self-efficacy, poor emotional regulation, and lack of adaptive coping mechanisms (Thomas and Maree, 2022; Zungu, 2022). In light of this, some students avoid seeking help from peers or lecturers, leaving them to struggle in isolation. Instead of persisting through setbacks such as exam pressure, they may disengage or procrastinate. Stress and anxiety may further exacerbate negative emotions, reducing focus and problem-solving capacity. A lack of reflective learning strategies and low self-efficacy weaken students’ confidence and motivation (Cassidy, 2016).

Failure to engage in resilience-building behaviors may result in mental health challenges, poor academic performance, delayed graduation, and, in some cases, dropout from the university (Bantjes et al., 2021; Permatasari et al., 2021). To mitigate these risks, it is crucial that students reframe setbacks not as failures but as an opportunity for growth. Cultivating resilience requires adaptive help-seeking, reflective engagement with learning strategies, and sustained commitment to academic goals despite pressure or adversity (Cassidy, 2016). In this regard, coping mechanisms play a central role. These include reliance on social and emotional support, as well as religious and spiritual coping strategies (Latif and Amirullah, 2020).

Spirituality, in particular, represents a fundamental and intangible dimension of an individual’s existence, transcending the physical realm (Pirnazarov, 2020). It is typically described as an innate sense that provides individuals with meaning, inspiration, a sense of connection to others, self-control and purposeful life (Timmins and Caldeira, 2019). Spirituality significantly shapes individuals’ worldviews and informs their life choices (Engelbrecht-Aldworth and Wort, 2021). While spirituality is frequently intertwined with religious beliefs and practices, it can also be a deeply personal experience, reflecting a connection with oneself, a higher being, and nature (Gonzalez et al., 2021). In the South African context, spirituality is particularly diverse, reflecting the country’s rich multicultural heritage and encompassing different pathways to enhance an individual’s spiritual experience. To mention a few, they include African traditional practices, referring to ancestral appeasing, Christian-based practices, Islam, and Hinduism (Bila and Carbonatto, 2022; Knoetze, 2022). Building upon this understanding, individuals frequently maintain and deepen their spiritual connection through the use of prayer, cultural traditions, connecting with nature (i.e., visiting mountains, caves, and rivers), and meditation. These practices offer emotional and existential comfort, particularly in times of adversity, as they provide a sense of closeness to a higher being (Harris, 2016). A well-established spiritual connection has been linked to greater optimism during periods of adversity and an enhanced capacity to derive meaning from life through a perceived relationship with the divine. In the context of South African higher education, students turn to spiritual practices, including prayer, ukuphahla (speaking to ancestors), and fellowship, as coping mechanisms to navigate academic stress and anxiety (Gukurume, 2024; Otanga, 2023). Taking this into account, exploring the role of spirituality among university students is critical in understanding its potential function as a mechanism that fosters academic resilience (Chakradhar et al., 2023).

The significance of spirituality and academic resilience becomes evident where higher education students face various challenging issues, which are noted as a global predicament (Chankseliani et al., 2021; Du Plessis et al., 2023). These challenges include financial problems, lack of resources, and inadequate social support (Du Plessis et al., 2023). Developed nations like the United States of America and the United Kingdom have well-established and well-funded higher education systems, notwithstanding the growing economic and social gaps in higher education around the world. In contrast, countries in the global south continue to face challenges with limited resources, financial constraints, and inadequate infrastructure (Moshtari and Safarpour, 2024; Tsou, 2023). Africa, as one of the global south continents, has the occurrence of high dropout rates in higher institutions, which are attributed to poor wellbeing of students and community, perpetuated by broader socio-economic challenges, low-income levels, and limited funding opportunities (de Oliveira et al., 2021).

South African higher education students are no exception; like other global south counterparts, their academic success is influenced by a variety of interrelated factors, many of which pose significant challenges to their progress (Chetty and Pather, 2015). North-West University students are similarly affected, with the majority facing difficulties such as inadequate funding, unresolved debts, limited access to suitable accommodation, and persistent challenges associated with National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS). These include delayed or unpaid allowances, which result in students’ basic needs remaining unmet (Chikwana, 2018). Such challenges are likely to diminish students’ motivation to study and may ultimately lead to loss of hope. Consequently, it becomes essential for students to develop a range of coping mechanisms to sustain academic engagement. These insights highlight the critical role of spirituality as a mechanism that fosters academic resilience. As both are recognized as positive psychological resources, spirituality and academic resilience enhance students’ capacity to navigate adversity and increase the likelihood of achieving satisfying outcomes (Ahmed et al., 2020).

The proven value of spirituality in coping with academic adversity underscores the need to explore its relationship to academic resilience in higher education. This is particularly relevant in South Africa, where the higher education sector continues to grapple with a dropout rate exceeding 40% (Marwala and Mpedi, 2022). This is largely attributed to socio-economic challenges, inadequate academic and emotional support, lack of funding, and the use of ineffective coping strategies (Branson and Whitelaw, 2024; Masutha, 2022). Students who are vulnerable to academic adversity are likely to experience anxiety, depression, and maladaptive behaviors such as substance use (Ragusa et al., 2023). However, other students demonstrate adaptive coping strategies to buffer the impact of stressors, utilizing cognitive resources, social resources, and emotional resources (Engelbrecht et al., 2020). The emerging evidence suggests that spirituality may serve as a significant protective factor associated with enhanced wellbeing and academic persistence (Cherian et al., 2021; Imron et al., 2023). However, most existing South African research has primarily concentrated on spirituality and academic resilience in the context of basic education (Mapaling et al., 2023), with limited attention on university students (Van Breda and Theron, 2018). Exploring the influence of spirituality on academic resilience within higher education is therefore pivotal for informing targeted interventions aimed at improving students’ retention and psychological wellbeing in higher education.

1.1 Aim and objectives

The study explored the association between spirituality and academic resilience among North-West University undergraduate students, with the objective to:

1. Determine the relationship between spirituality and academic perseverance among university undergraduates.

2. Investigate the relationship between spirituality with negative affect and emotional response among university undergraduates.

3. Investigate the relationship between spirituality and academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking among university undergraduates.

4. Investigate the relationship between spirituality and academic resilience among university undergraduates.

1.2 Hypotheses

1. Spirituality will significantly and positively associate with academic perseverance among university undergraduates.

2. Spirituality will significantly associate positively with negative affect and emotional response to academics among university undergraduates.

3. Spirituality will significantly associate positively with academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking among university undergraduates.

4. Spirituality will significantly and positively associate with academic resilience among university undergraduates.

2 Literature review

Spirituality involves seeking a deep connection with the transcendent through daily experiences, fostering spiritual wellbeing by engaging with the divine in everyday life (Groves, 2021; Davis et al., 2023; Underwood and Teresi, 2002). Daily spiritual experiences can serve as perceived divine social support, offering emotional and practical assistance, which is relevant in understanding how spirituality may help students perform academically despite adversity. Within positive psychology, spirituality is recognized as a vital aspect of human experience and a resource for resilience. This study adopts Cassidy’s (2016) Academic Resilience Theory to explore how students maintain optimal academic functioning in the face of challenges. The theory highlights resilience as a process involving academic adversity, protective factors, such as spirituality and positive academic outcomes. The subsequent section of the literature review will discuss spirituality in relation to the core components of academic resilience, including negative affect and emotional response, academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking, academic perseverance, and overall academic resilience.

Adversity often triggers negative emotions that can impair an individual’s functioning, with depression and anxiety common among students whose goals are in jeopardy (Troy et al., 2023; Ang et al., 2021). Spirituality can influence how these emotions are managed, however, the direction of this influence depends on the meaning students attach to their experience. For instance, some scholars suggest spirituality may contribute to negative effects when individuals attribute misfortunes to divine punishment or abandonment (Fox, 2018), or experience scrupulosity, which is excessive guilt and anxiety over moral issues (Mancini et al., 2023). However, other studies report that higher daily spiritual engagement is linked to greater positive effects, reduced risk of depression, and substance use (Perez, 2021; Britt et al., 2022). In the South African context, spirituality was found to mitigate depression among medical students (Pillay et al., 2016). These findings point to underlying psychological dynamics where spirituality fosters positive affect, which in turn broadens cognitive flexibility, supports adaptive coping and proactive self-improvement (Yang and Wang, 2022).

Academic reflection is a critical cognitive process that enable students to transform setbacks into opportunities for growth, thereby strengthening academic resilience (Elias, 2010). Reflection involves a continuous process in which students evaluate, review and analyse their experiences to formulate an action plan for future learning and development (Pei et al., 2020). For instance, when students underperform in an assessment, they may engage in a reflective process that involves seeking feedback and guidance to improve future outcomes (Cavilla, 2017). Spirituality can enhance this reflective capacity through constant prayer, immersion in nature and participation in spiritual meditation practices (Ezealah, 2019). These practices not only strengthen problem-solving abilities but also foster deeper engagement in the learning process to enhance academic resilience. In addition, reflection is often complemented by adaptive help-seeking, whereby students turn to available resources to address challenges, often through positive social interactions with peers, teachers, or other support sources rather than withdrawing (Li et al., 2023; Chou and Chang, 2021). In this regard, spirituality can serve as both a moral compass and a behavioral regulator. For some students, spiritual or religious beliefs forbid them to engage in maladaptive behaviors such as the use of substances (Teo et al., 2021), reinforcing healthier patterns of resilience. However, students with more external locus of control are less likely to engage in the reflective learning process as they attribute their misfortunes to external factors (Pachón-Basallo et al., 2022; Sagone and Indiana, 2021). Additionally, gender disparities may shape coping preferences, whereby men might require more problem-focused coping while women use emotion-focused strategies, hence the framework may not yield the same results to both groups.

Low academic motivation, manifesting through behaviors such as procrastination, inattentiveness, and course repetition, is a common barrier to academic success and resilience (Imron et al., 2023). From a psychological perspective, motivation fuels persistence, goal-directed behavior and the ability to withstand academic adversity. Spirituality can strengthen these motivational dynamics by fostering a sense of flow and purpose in learning, this meaning making process enhances perseverance, a core element of academic resilience (Cherian et al., 2021; Sargeant and Yoxall, 2023). However, an overemphasis on academic outcomes may increase stress and, and paradoxically, weaken spiritual engagement (Zhou et al., 2024; Mendoza, 2022). Conversely, spiritual beliefs have been shown to strengthen motivation and persistence during academic adversity (Villacís et al., 2021; Imron et al., 2023). Gender-related tendencies may further influence these dynamics, as male rely in logic or engage in risk-taking behaviors, which can undermine sustained focus and resilience in academic context.

Academic adversities are experienced globally, although they might differ from one context to another (Allwood et al., 2021). Also, spirituality is a global phenomenon individuals possess to cope with adversities (Algahtani et al., 2022). For instance, a study by Chakradhar et al. (2023) reported a positive relationship between spirituality and resilience among social work students in the U.S. Chakradhar and colleagues further mentioned that most students indicated that praying offered emotional relief, connectedness, and meaning making. Similarly, studies conducted with Indian, Vietnamese, Iranian, Chinese and New Zealand undergraduate students found a significant positive relationship between spirituality and academic resilience regardless of their cultural background (Cherian et al., 2021). Therefore, irrespective of our diversity, spirituality plays a positive role in determining an individual’s response to adversity and has healing and qualities that enhance growth (Chakradhar et al., 2023).

Sub-Saharan African countries experience various socio-economic challenges (Nyaruaba et al., 2022). Studies have identified several challenges, including poverty amongst other social ills, as prevalent issues in countries such as Nigeria and Zambia (Okechukwu et al., 2022). The Afrocentric values of religion and spirituality played a role in the provision of a sense of security, meaning, stability and purpose in the face of adversity, such as the loss of a significant other and financial deprivation for Ghanaian students (Abukari, 2018). A study by van Breda and Theron (2018) suggested that spiritual beliefs were a dominant factor for the academic achievement of young school children from disadvantaged backgrounds in South Africa because they promote connectedness, offer guidance and positive meaning-making. The posture or attitude is related to Viktor Frankl’s view that human beings have the will to achieve a sense of meaning and purpose in life (Cuncic, 2023). Accordingly, a study by Swart (2021) suggests South African school children, in the face of adversities, use traditional ancestral practice, prayer, and attending church. Faith in a higher power gives them the courage to live their lives and provide comfort during challenging times (Dey and Parayil, 2020). Although studies suggest that spirituality can serve as a significant source of academic resilience for many students, reliance on spiritual beliefs for some students may undermine personal agency, leading students to overlook practical problem-solving strategies that are crucial in overcoming academic adversities (Fuertes, 2024). Some authors argue that spiritual practices may not benefit all students, as their effectiveness depends on individual beliefs and cultural context (Smith and Bernard, 2023; Van Cappellen et al., 2023). In terms of gender and age variations, females tend to be more resilient than males, likely due to greater engagement in spiritual practices and help-seeking behaviors (Romano et al., 2021; Vardy et al., 2023; Yalcin-Siedentopf et al., 2021). Conversely, younger students, especially first-years, often struggle to adapt to higher education due to limited coping skills and sometimes prioritizing social activities and alcohol use over academics (Cage et al., 2021; Ibáñez-Cubillas et al., 2023). Furthermore, resilience tends to increase with age as individuals gain life experience, while students under 20 often rely on caregivers, limiting their ability to manage academic stress independently (Edara et al., 2021; Rossi et al., 2021; O'Shea et al., 2024).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study design

A correlational research design was adopted to investigate spirituality and academic resilience among North-West University Undergraduate students. A correlational study was used because it examines the relationship between two or more variables and typically involves two or more scales to collect data (Gravetter and Forzano, 2018; Seeram, 2019), making it suitable for this study on spirituality and academic resilience. Thus, the study used Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) and Academic Resilience Scale-30 (ARS-30).

3.2 Study setting

This study was conducted at North-West University (NWU), South Africa. NWU was the fourth-largest university in terms of enrolment in 2024, with a total headcount of 41,566 undergraduate students. Moreover, NWU is located within two provinces in South Africa, which are North-West Province and Gauteng Province. It has three campuses, namely, Mahikeng Campus (MC), Potchefstroom Campus (PC) and Vanderbijlpark Campus (VC). It forms part of institutions of students that are affected by academic adversities.

3.3 Population

The study’s population consisted of undergraduate contact students from North-West University (NWU), which comprises of three campuses: Mahikeng, Potchefstroom, and Vanderbijlpark. NWU was selected as the study site due to budget and time constraints, the accessibility of gatekeepers, and the manageable scope of the population.

3.4 Sampling, sampling technique, and sample size

Stratified random sampling was adopted in the current study (post ad hoc). Stratified random sampling is a type of sampling that entails the process of dividing the targeted population into subgroups with similar characteristics (Kobus, 2019). This sampling was useful to ensure that the demographic characteristics of students were well represented in the current study. Different demographic characteristics, such as sex, age, and campus location characterize the population of North-West University undergraduate students.

The Yamane formula was used to calculate the sample size from the total number of the targeted population.

According to Yamane (1967), is simplified sampling size generating formula, whereby:

• n = signifies the sample size

• N = signifies the population under study

• e = signifies the margin error (0.05)

• n = N/ (1 + N (e)2) = 39,058/(1 + 39,058 (0.05)2) = 396 sample

Of 39,058 undergraduate students across the NWU’s three campuses (Mahikeng, Potchefstoom, and Vanderbijilpark) as at (year the data was collected), the Yamane formular was used to arrive at 396 participants. The sample was increased to 420 to increase generalization of the findings (Borodovsky, 2022).

3.4.1 Sample inclusion criteria

The current study comprised undergraduate students who were registered at North-West University in 2023 and were from all racial groups, all ethnic groups and both males and females. This was because undergraduate contact students are mostly pressured to finish the course within a stipulated period (mostly 3–4 years), and the workload becomes more as they proceed to the following levels of the course.

3.4.2 Sample exclusion criteria

The current study did not include part-time students, open distance learning students, and postgraduate students. Mostly, part-time students are often employed and taking fewer courses and assumed to face less academic risk than full-time contact students. Similarly, open-distance students face fewer challenges as they often study at their own pace, do on-the-job training and experience less school-related fees.

3.5 Ethical procedure

The ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at the North-West University with the study number NWU-00195-23-S1. The study was conducted in line with the Helsinki declaration on studies involving humans. A consent form outlining the following terms: voluntary participation, anonymity, and confidentiality, was provided. Participants could withdraw any time, were given, and strictly adhered to.

3.6 Data collection procedure

A recruitment period was designated to advertise the study and enroll participants who met the inclusion criteria. An advertisement poster was developed for this purpose. Permission to disseminate the advertisement was obtained through the North-West University (NWU) eFundi platform,1 the institution’s official course management and online learning system. The researcher created an online questionnaire that was divided into four sections. Section one consisted of the consent form, outlining terms, including voluntary participation, anonymity, confidentiality, and provision for participants to withdraw any time, and section two with demographic information questions that sought to collect demographic information of the participants. Section three consisted of the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES), a 16-item self-report measure to measure the spiritual experience of students (Underwood and Teresi, 2002). Section four entailed the Academic Resilience Scale (ARS-30), a 30-item that explores the process of resilience in the academic aspects of students (Cassidy, 2016). The questionnaire was digitized using Google Forms, and the access link was included in the eFundi portal, enabling eligible participants complete the questionnaire online, using their own internet-connected devices (i.e., smartphones, laptops, etc.). The following are the description of the sale used.

3.6.1 Measurements

3.6.1.1 Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) by Lynn G. Underwood

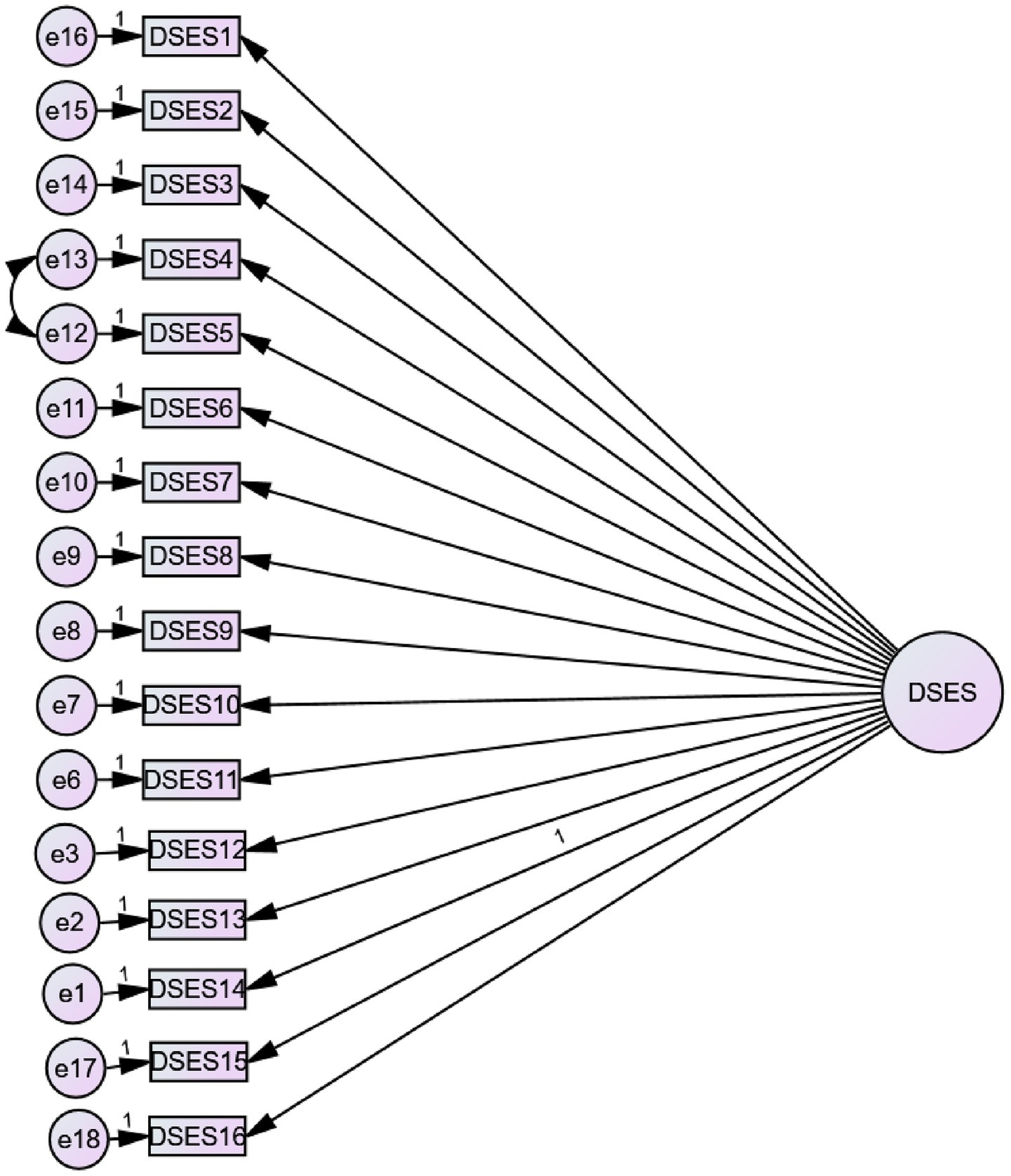

The Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES), developed by Underwood (2011), is a 16-item self-report measure, 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from (1 = many times, 2 = every day, 3 = most days, 4 = some days, 5 = once in a while, 6 = never) which accounts for item 1–15. The 16th item has four response categories (not close at all, somewhat close, very close, and as close as possible). It is designed to assess an individual’s ordinary connection experience with the transcendent in daily life. Various cultures have used the scale effectively (Underwood, 2011). The scale is scored in a manner that lower scores correspond to more frequent Daily Spiritual experiences, such as the score of 1, “many times a day” (Underwood, 2011). DSES Cronbach alpha of the scale has a high internal consistency of 0.89–0.95, with test–retest reliability of 0.85. The English version of the scale has been validated for use in South African students, with an internal consistency of 0.85. Therefore, the 16-item DSES is valid for use in South Africa to measure spiritual experience (Shube, 2020). With the current study, the Cronbach alpha indicated high-reliability coefficient ranging between 0.74 and 0.90.

Reliability and construct validity of this scale from the analysis, an initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) performed on the Daily Spiritual Experience Scale (DSES) showed a less-than-fair model fit for the data given the poor CFI and RMSEA values, χ2 (104) = 533.53, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.86, RMSEA = 0.10 [90% CI = (0.09, 0.11)], and SRMR = 0.06. Modification indices (MI) suggested covarying the error terms of items 4 (“I find strength in my religion or spirituality”) and 5 (“I find comfort in my religion or spirituality”). After the covariation, an acceptable model fit was obtained for the DSES scores, χ2 (103) = 390.11, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.08 [90% CI = (0.07, 0.09)] and SRMR = 0.06. Figure 1 presents the CFA for the DSES with standardized loadings.

3.6.1.2 Academic Resilience Scale (ARS-30) by Simon Cassidy

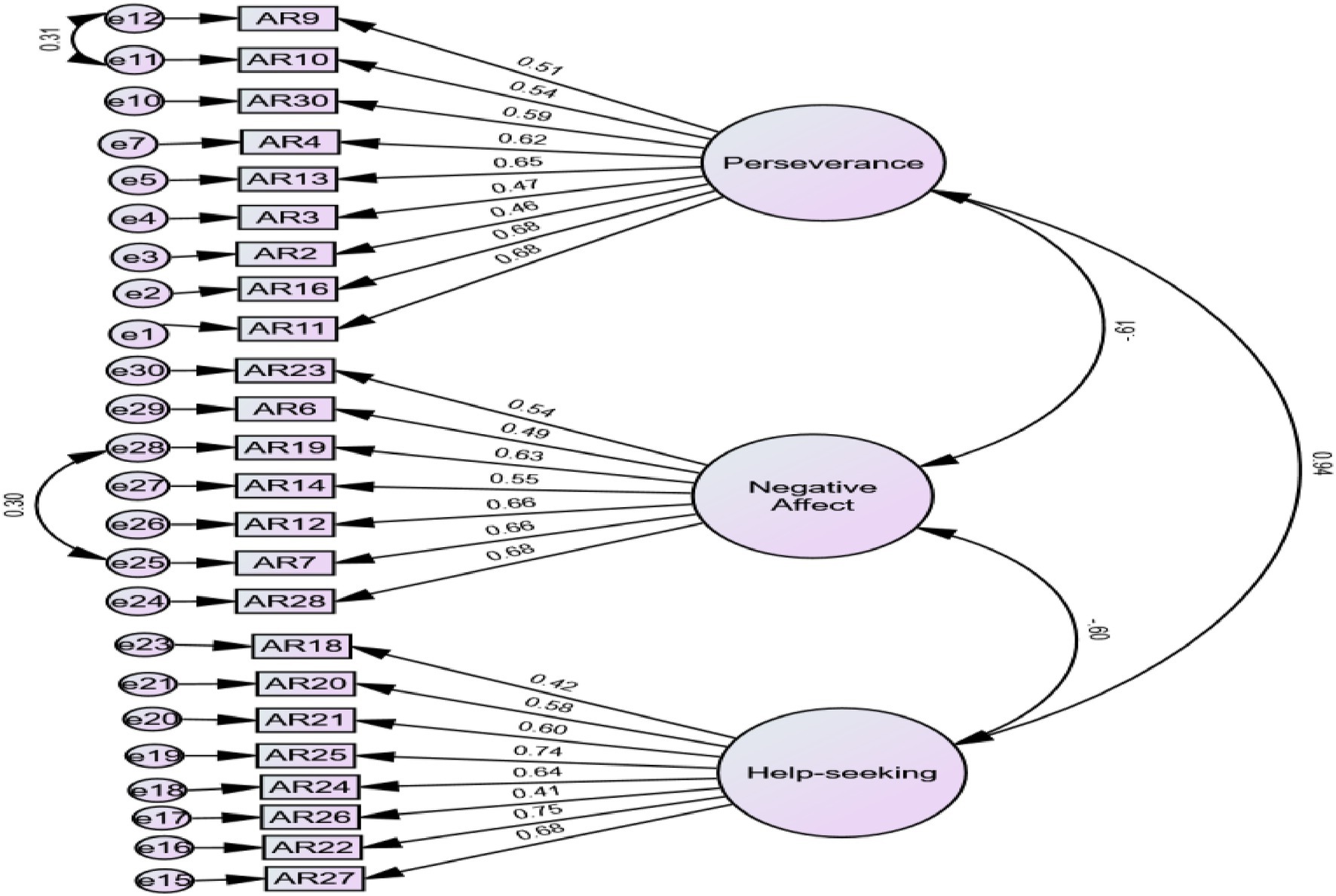

The Academic Resilience Scale (ARS-30), developed by Cassidy (2016), is a 30-item scale with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). For each item, scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores representing stronger agreement with the statement. ARS-30 has high reliability for use with a Cronbach alpha of 0.90 for the global scale, which satisfies the minimum requirement of Cronbach Alpha coefficient of 0.70. The ARS-30 has 3 subscales which demonstrated high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.83 for perseverance (items 1–5, 8–11, 13, 15–17, 30), 0.80 for reflection and adaptive help-seeking (items 18, 20–22, 24–27, 29), and 0.78 for negative affect and emotional response (items 6, 7, 12, 14, 19, 23, 28). Although ARS-30 has not been formally validated in South Africa, it has been widely used in local research. For example, Adigun and Ndwandwe (2022) studied academic resilience among deaf learners; Aloka (2023) explored its role in academic adjustment among first-year distance learners; and Mapaling et al. (2023) examined its link to entrepreneurship education. Each ARS-30 item is scored from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating stronger agreement. Total scores range from 30 to 150, with higher scores reflecting greater academic resilience (Cassidy, 2016).

From the analysis on reliability and construct validity of this scale, the initial CFA for the ARS-30 subscales showed a poor model fit: χ2 (402) = 1,052.97, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.83; RMSEA = 0.06 (90% CI: 0.06–0.07); SRMR = 0.07. Items with low standardized loadings (0.09–0.38) were removed from further analysis: items 8, 1, 5, 17, and 15 (perseverance subscale) and item 29 (help-seeking). Additionally, error terms were covaried for items 9 and 10 (perseverance), and items 7 and 19 (negative affect). These modifications improved model fit to acceptable levels: χ2 (247) = 578.22, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.057 (90% CI: 0.05–0.06); SRMR = 0.06. Figure 2 presents the final CFA model for the ARS with standardized loadings. The internal consistency coefficients of scores on study instruments. All scales and subscales have high-reliability coefficients ranging between 0.74 and 0.90, as presented in Table 1.

3.7 Data analysis

Data was analyzed using IBM Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 29. Descriptive statistics (e.g., frequencies and percentages) summarized demographic variables (Fernandes et al., 2019; Murphy, 2021), while inferential statistics tested the relationship between spirituality and academic resilience and tested all focal variables. Bivariate correlation analysis was used to examine the relationship between spirituality, academic resilience, and other focal variables. Hierarchal Multiple Regression Analysis was also used to test all the study’s hypotheses regarding the relationship between spirituality (independent variable) and academic perseverance, academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking, negative affect and emotional response, and academic resilience (dependent variables). Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed as a multivariate tool to examine relationships among observed and latent variables, including spirituality, academic perseverance, academic reflection and help-seeking, negative effect and emotional response, academic resilience, and demographic factors (age, gender, campus location) (Kline, 2023). SEM allowed for testing multiple hypotheses within a unified model and assessing the fit of the conceptual framework. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted on the DSES and ARS-30 prior to data analysis, with reliability and validity results presented in the scales description above.

4 Results

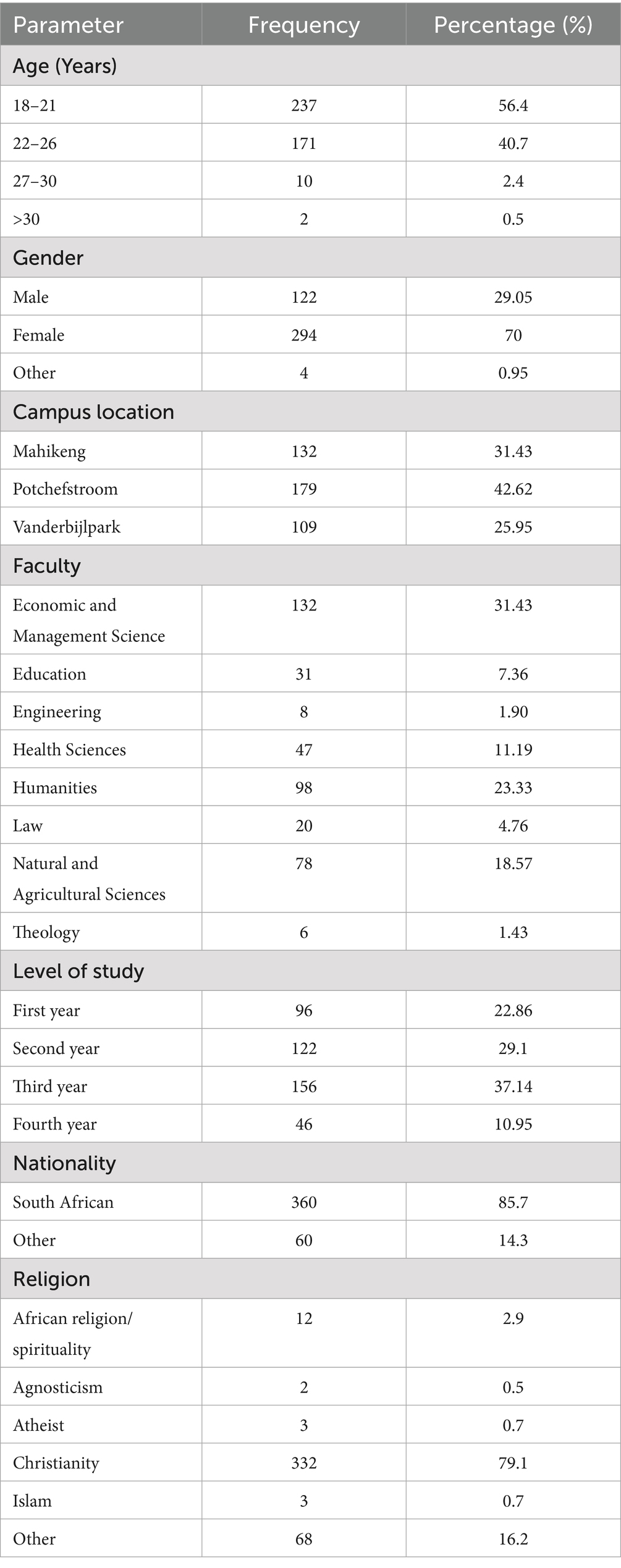

4.1 Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic indicators

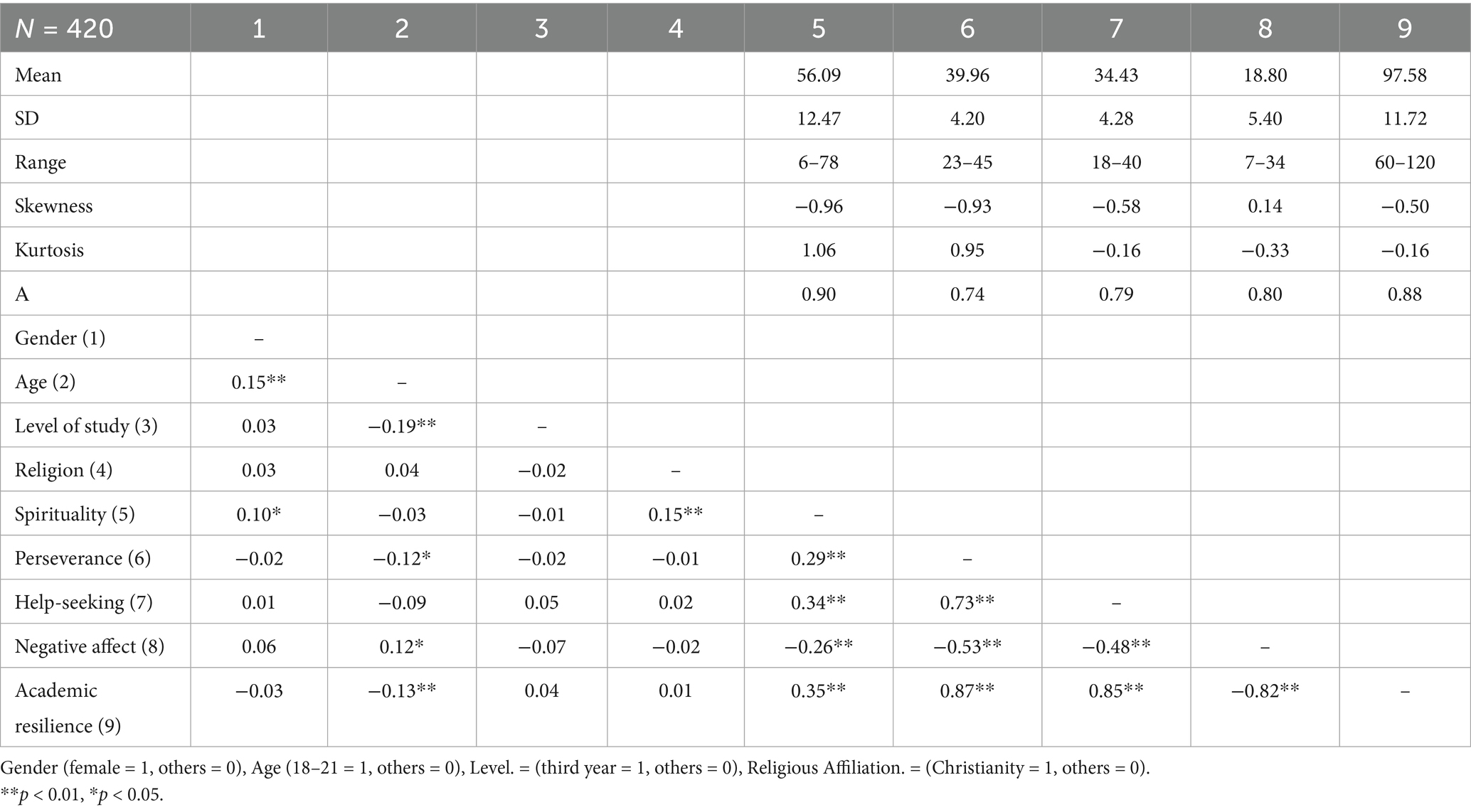

The study considered sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, campus location, faculty, level of study, nationality, and religious affiliation. As shown in Table 2, most participants were aged 18–21 (56.4%), female (70%), and from the Potchefstroom campus (42.6%). Most were enrolled in the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences (31.43%) and in their third year of study (37.14%). A large proportion identified as Christian (79.1%) and South African nationals accounted for by (85.7%).

4.2 Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics

The results of bivariate relationships among variables are displayed in Table 1. All focal variables were significantly correlated with each other. Spirituality was positively correlated with perseverance (r = 0.29, p < 0.001), help-seeking (r = 0.34, p < 0.001) and academic resilience total scores (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) but negatively associated with negative effects (r = −0.26, p < 0.001). Of all the demographic variables, only age was significantly associated with academic resilience and some of its subscales, albeit at weak levels. Specifically, being of age 18–21 was associated with lower perseverance (r = −0.12, p < 0.01), high negative affect (r = 0.12, p < 0.01) and low academic resilience (r = −0.13, p < 0.01).

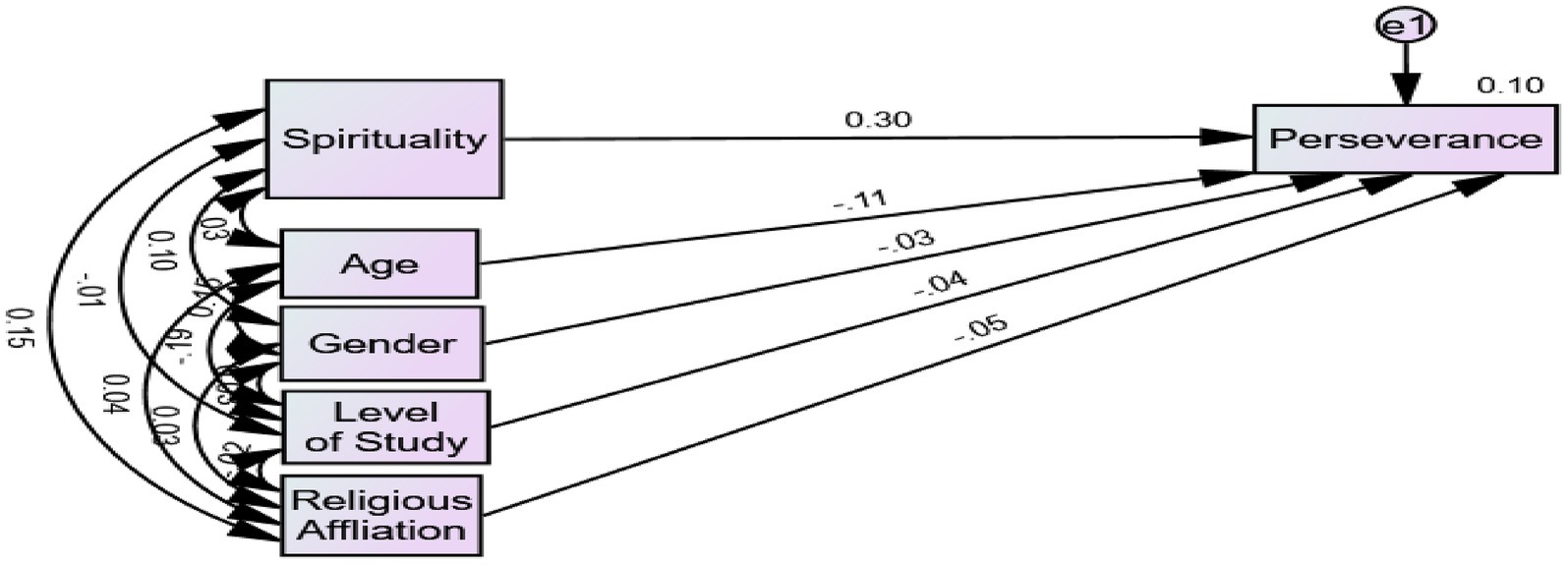

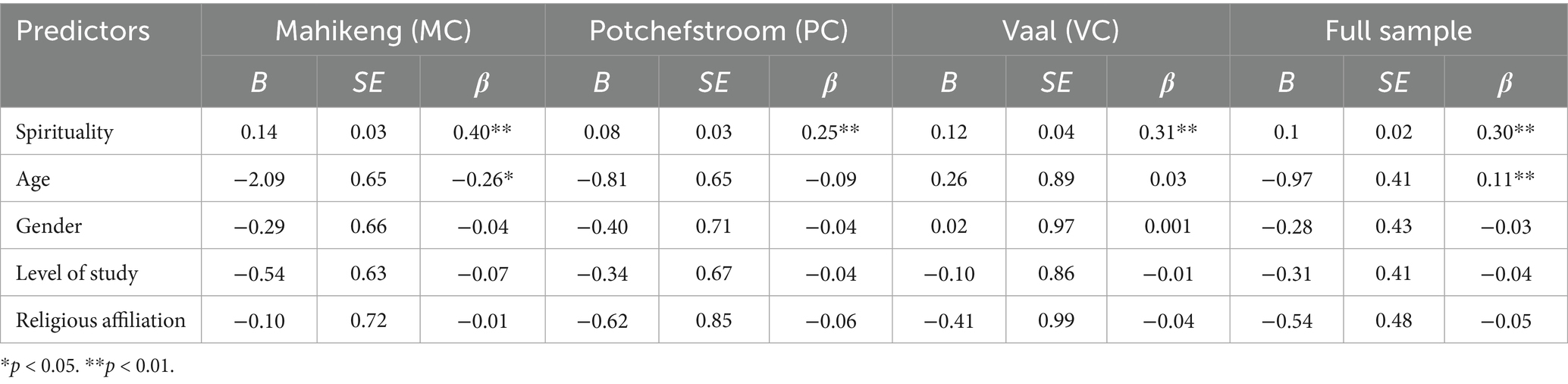

Hypothesis 1: It was hypothesized that spirituality will significantly associate positively with academic perseverance among North-West University undergraduate students. This hypothesis was examined using multiple regression analysis, with academic perseverance regressed on spirituality while controlling gender, age, level of study, and religious affiliation. The standardized path estimates are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Spirituality predicting academic perseverance while controlling for socio-demographics. The model in this figure is for the total sample.

The regression analysis results for samples obtained from the three NWU campuses and for the total sample are displayed in Table 3. Outcomes show that high spirituality significantly predicts high academic perseverance across samples from the three campuses [MC (β = 0.40, p < 0.001), PC (β = 0.25, p < 0.001), VC (β = 0.31, p < 0.001)] and the whole sample (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). Of all the control variables, only age was significantly associated with academic perseverance in MC (β = −0.26, p < 0.05) and the total samples (β = −0.11, p < 0.01). Specifically, being aged 18–21 was associated with low perseverance. The model predicted 21, 6, 11 and 10% variances in academic perseverance in MC, PC, Vaal and the total sample, respectively.

Table 3. Summary of the multiple regression analysis on the relationship between spirituality and academic perseverance stratified by campus location.

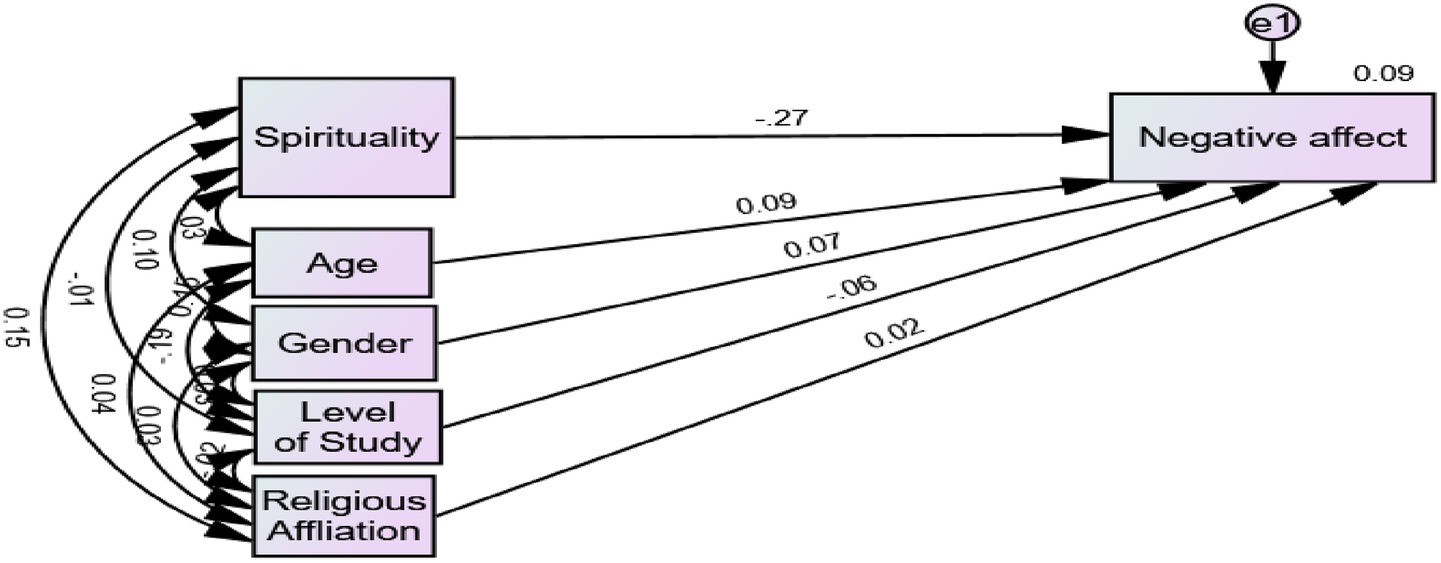

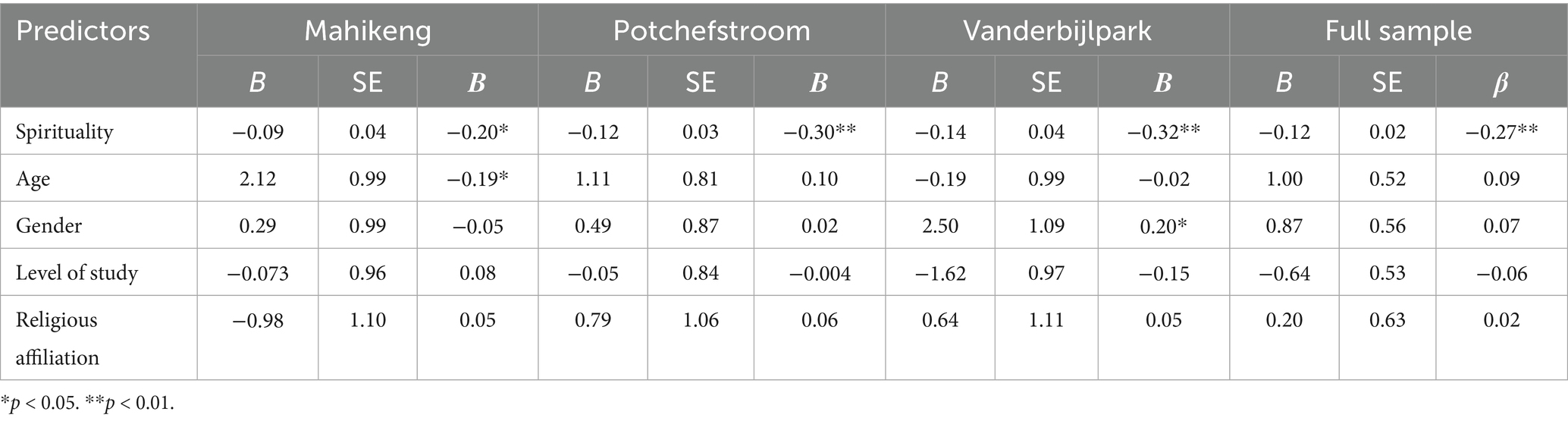

Hypothesis 2: Spirituality will significantly associate positively with negative affect and emotional response among North-West University undergraduate students. This was tested using multiple regression while controlling gender, age, level of study, and religious affiliation. Standardized estimates are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Spirituality predicting negative affect and emotional response. The model in this figure is for the total sample.

Table 4 shows that high spirituality significantly predicted low negative affect and emotional response across samples from the three campuses [MC (β = −0.20, p < 0.05), PC (β = −0.30, p < 0.001), VC (β = −0.32, p < 0.001)] and the total sample (β = −0.27, p < 0.001). The control variables, age and gender, were significantly associated with negative affect and emotional response in MC (β = 0.19, p < 0.03) and VC (β = −0.20, p < 0.02) campuses, respectively. Specifically, being aged 18–21 was associated with more negative affect and emotional response, while being a female was related to less negative affect and emotional response. The model predicted 8, 9, 16 and 9% variances in negative affect and emotional response in MC, PC, VC and the total sample, respectively.

Table 4. Summary of the multiple regression analysis on the relationship between spirituality and negative affect and emotional response stratified by campus location.

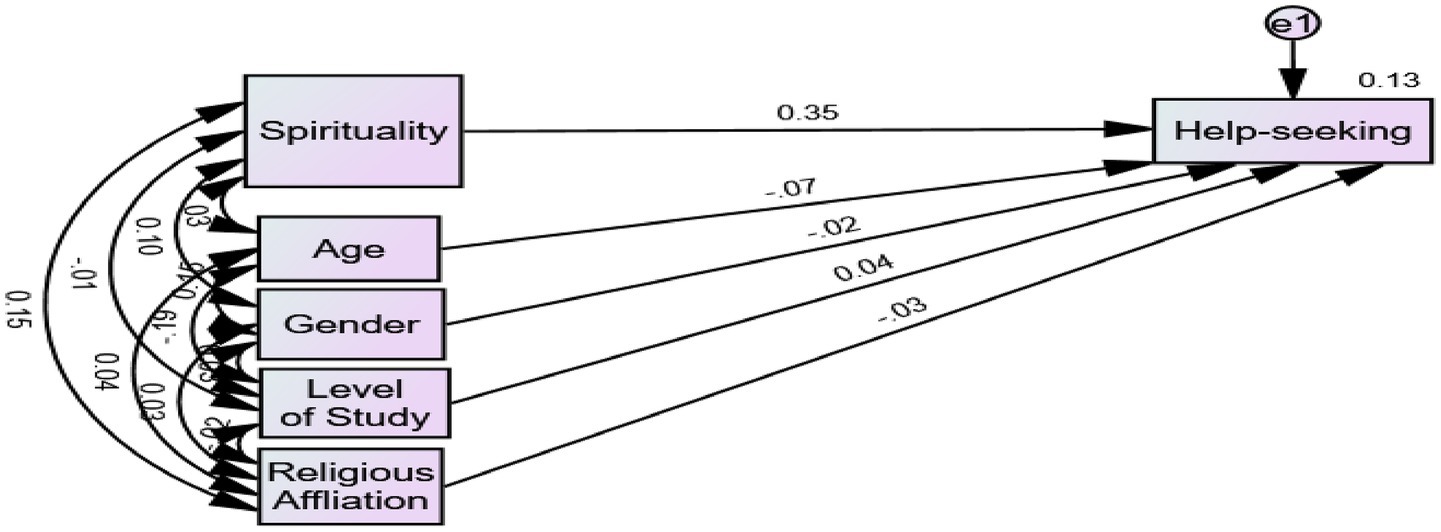

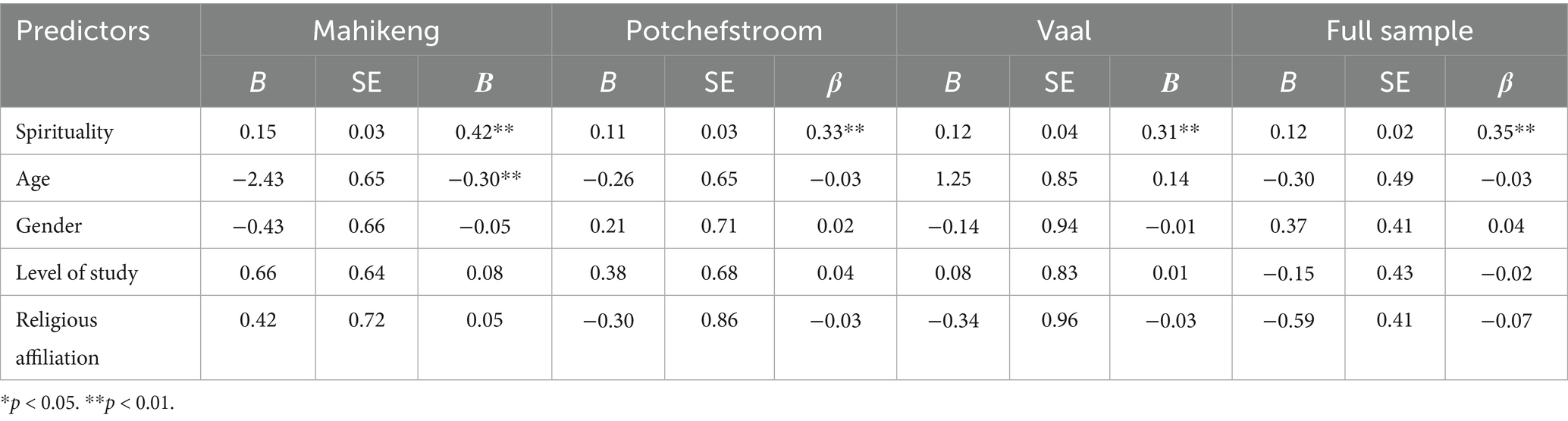

Hypothesis 3: Spirituality will significantly associate positively with academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking among North-West University undergraduate students. This was tested using multiple regression, controlling for gender, age, level of study, and religious affiliation. Standardized estimates are shown in the path diagram in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Spirituality predicting academic reflecting and adaptive help-seeking. The model in this figure is for the total sample.

Table 5 indicates that high spirituality significantly predicts high academic reflecting and adaptive help-seeking across samples from the three campuses [MC (β = 0.42, p < 0.001), PC (β = 0.33, p < 0.001), VC (β = 0.31, p < 0.001)] and the total sample (β = 0.35, p < 0.001). Only the control variable, age, was significantly associated with academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking in Mahikeng (β = −0.30, p < 001). Specifically, age 18–21 was associated with low academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking. The model predicted 26, 11, 12 and 13% variances in academic reflecting and adaptive help-seeking in MC, PC, VC and the total sample, respectively.

Table 5. Summary of the multiple regression analysis on the relationship between spirituality and academic reflecting and adaptive help-seeking stratified by campus location.

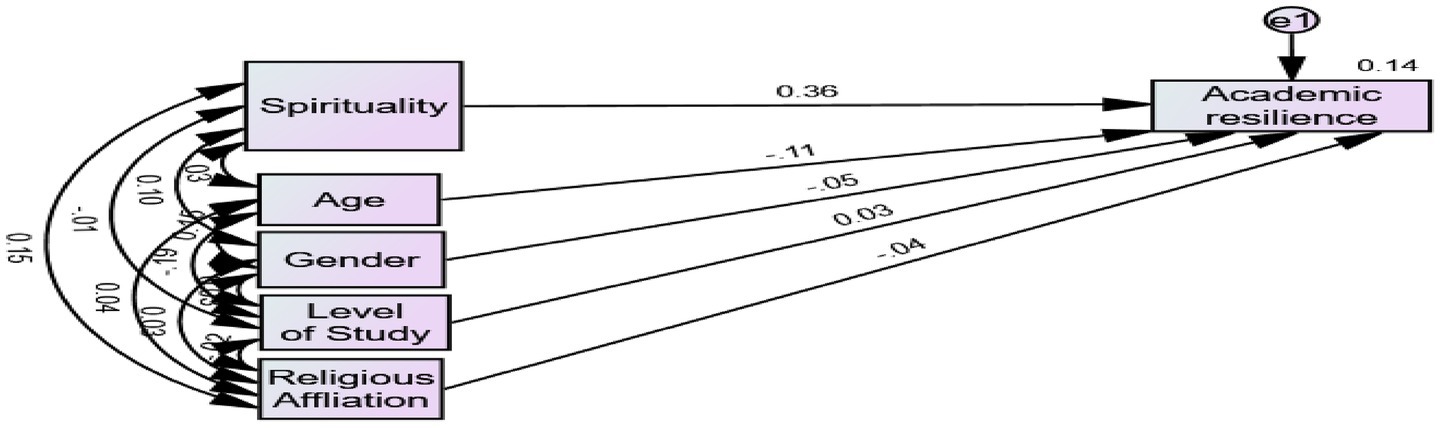

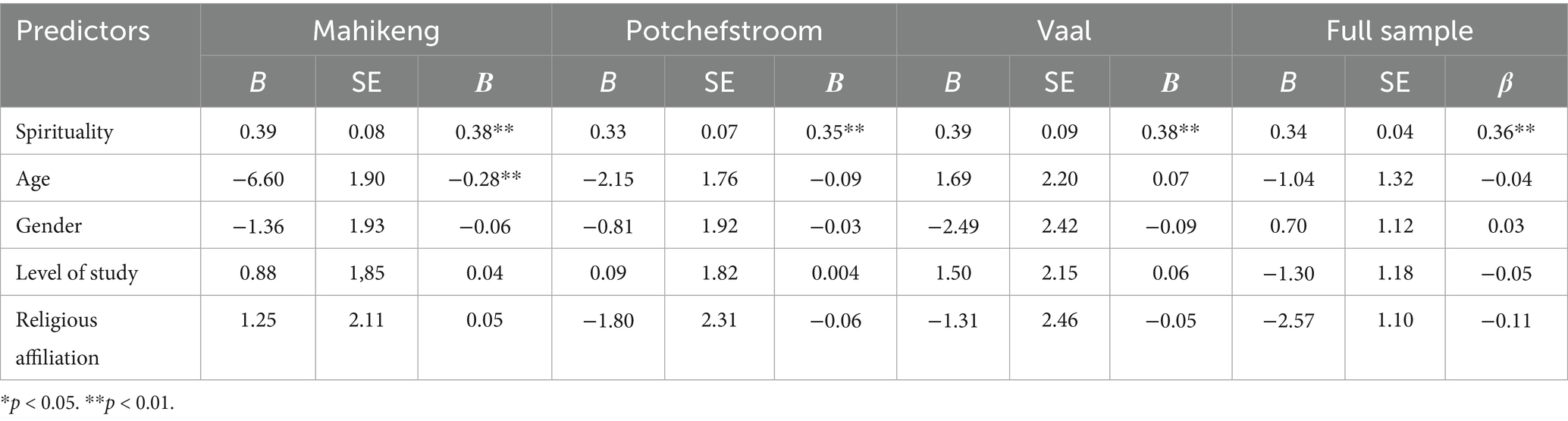

Hypothesis 4: Spirituality will significantly positively associate with academic resilience among North-West University undergraduate students. This was tested using multiple regression, controlling for gender, age, level of study, and religious affiliation. Standardized estimates are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Spirituality predicting academic resilience while controlling for socio-demographics. The model in this figure is for the total sample.

Table 6 indicates that high spirituality significantly predicted high academic resilience across samples from the three campuses [MC (β = 0.38, p < 0.001), PC (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), VC (β = 0.38, p < 0.001)] and the total sample (β = 0.36, p < 0.001). Only the control variable, age, was significantly associated with academic resilience in MC (β = −0.28, p < 0.001). Specifically, age 18–21 was associated with low academic resilience. The model predicted 21, 11, 17 and 14% variances in academic reflecting and adaptive help-seeking in MC, PC, VC and the total sample, respectively.

Table 6. Summary of the multiple regression analysis on the relationship between spirituality and academic resilience stratified by campus location.

5 Discussion

The study results indicated high spirituality significantly correlated with and predicted greater academic perseverance across all three campuses of North-West University. Among the sociodemographic variables, only age showed a significant association—specifically in Mahikeng—where students aged 18–21 reported lower perseverance. This aligns with previous studies showing that spiritually engaged students often draw motivation from a belief in a higher purpose, which helps them persist despite challenges (Imron et al., 2023; Villacís et al., 2021). Spirituality thus appears to act as a protective factor, as suggested by academic resilience theory, enabling students to cope with adversity and maintain commitment to academic goals (Cassidy, 2016). Spiritual theory similarly highlights how spiritual experiences foster meaning, purpose, and engagement (Cuncic, 2023), which may explain why students with high spirituality persevere instead of giving up. Students under 21 may struggle with motivation and resilience due to transitional challenges and increased independence. This is supported by research showing younger students are more likely to disengage academically (Ibáñez-Cubillas et al., 2023), sometimes prioritizing social activities and alcohol use over academics (Cage et al., 2021).

The results indicated that spirituality was associated with low negative affect and emotional response from NWU undergraduate students, contradicting the hypothesis and previous findings that associated spirituality with increased positive emotions and life satisfaction (Yang and Wang, 2022; Perez, 2021; Britt et al., 2022). This may reflect the influence of student context and experiences on emotional responses to academics. Despite this, literature shows spirituality promotes mental wellbeing and reduces risks of depression, substance abuse (Cherian et al., 2021; Pillay et al., 2016; Perez, 2021). Theories of spirituality and self-transcendence support its role in enhancing positive affect, meaning, and purpose (Pirnazarov, 2020; You and Lim, 2019; Timmins and Caldeira, 2019). Additionally, younger students (18–21) and males reported higher negative affect, consistent with research suggesting younger students struggle more with academic stress (Ibáñez-Cubillas et al., 2023). Institutions should therefore offer support interventions, such as study skills and exam preparation workshops.

Spirituality positively predicted academic reflection and adaptive help-seeking among NWU students. This supports findings that spiritually inclined students engage in reflection, seek feedback, and learn from setbacks (Cavilla, 2017; Ezealah, 2019). They also show positive help-seeking behaviors, turning to peers or lecturers rather than withdrawing (Chou and Chang, 2021). Spirituality fosters coping, social connectedness, and self-control (Timmins and Caldeira, 2019), while discouraging maladaptive behaviors like substance use (Teo et al., 2021). Overall, it supports academic resilience and mental wellbeing.

Bivariate correlation and hierarchical multiple regression results confirmed a positive relationship between spirituality and academic resilience, supporting the study’s hypothesis. Prior research similarly found that spirituality enhances academic resilience across diverse student populations (Chakradhar et al., 2023; Cherian et al., 2021). Spirituality acts as a coping mechanism and buffer against academic challenges (Gukurume, 2024; Otanga, 2023). The academic resilience framework identifies spirituality as a key protective factor (Cassidy, 2016), while the theory of spirituality frames it as a path to meaning and psychological strength in adversity (Sargeant and Yoxall, 2023). Spirituality also enhances social connectedness and control, promoting resilience (Chakradhar et al., 2023), and aligns with the spiritual theory, which links spiritual wellbeing with hope, life satisfaction, and meaning (Imron et al., 2023; Groves, 2021).

Overall, literature, theory, and results affirm that adversity itself does not determine outcomes, rather, how students respond to it, using protective factors like spirituality, is key. Notably, students aged 18–20 showed lower levels of spirituality and resilience, likely due to developmental factors, limited life experience, and reduced spiritual engagement (Edara et al., 2021). Resilience tends to increase with age as individuals face and manage more challenges (Cage et al., 2021; O'Shea et al., 2024).

6 Conclusion

Academic challenges pose global concerns, affecting student performance and retention. Yet, some students demonstrate resilience, maintaining academic success despite adversity. Spirituality emerges as a key protective factor, positively related to academic resilience, adaptive help-seeking, and perseverance, while mitigating negative emotional responses among NWU undergraduates. This indicates spirituality not only sustains resilience but also helps manage emotional difficulties effectively. Although positive relationships exist across focal variables, variations by age and gender were observed, warranting consideration. These findings underscore the value of integrating spiritual activities, such as mindfulness, meditation, prayer, and traditional African practices into university programs to support diverse student needs and foster resilience. Educators should recognize spirituality’s role in coping with academic pressure by incorporating spiritual wellbeing discussions in advising, offering workshops that include spiritual components, and creating supportive spaces for spiritual exploration. In health practice, especially counseling, addressing clients’ spiritual dimensions enhances holistic care and therapeutic effectiveness. Training practitioners to conduct spiritual assessments respects individual beliefs and aligns interventions with clients’ sources of strength. For policymakers and university administrators, these results advocate for inclusive frameworks acknowledging diverse spiritual practices as essential to student wellbeing and academic success. Integrating spirituality into student support services can improve validation, engagement, and outcomes.

The study used a quantitative methodology, which limits the depth of exploration into spirituality and academic resilience due to their subjective nature. Limitations include reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce response bias, introduced selection bias, favoring students with internet access and willingness to engage with spiritual topics, and the use of ARS-30, which has not been validated in the South African context, potentially affecting validity. Furthermore, quantitative analysis may overlook contextual nuances and have possible technique bias. To mitigate these limitations, CFA was used to assess the measurement tools, and participants were encouraged to respond honestly. Future research may consider broader geographic scope to increase the generalizability of the findings and should employ qualitative methods to deepen insights into spirituality’s role in academic resilience, exploring cultural factors across varied student populations to enrich understanding and support.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by North-West University-Human Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. CO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Expenses such as participant airtime, statistical analysis, and language editing were funded by the North-West Department of Health Bursary and North-West University postgraduate bursary.

Acknowledgments

Sincere gratitude to all key role players who contributed to this study, and gratefully acknowledge the participants for their time, effort, and willingness to be involved in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Abukari, Z. (2018). “Not giving up”: Ghanaian students’ perspectives on resilience, risk, and academic achievement. SAGE Open 8:2158244018820378. doi: 10.1177/2158244018820378

Adigun, O. T., and Ndwandwe, N. D. (2022). Academic resilience among deaf learners during e-learning in the COVID-19 era. Res. Soc. Sci. Technol. 7, 27–48. doi: 10.46303/ressat.2022.8

Ahmed, M. A., Hashim, S., and Yaacob, N. R. N. (2020). Islamic spirituality, resilience and achievement motivation of Yemeni refugee students: a proposed conceptual framework. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 19, 322–342. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.19.4.19

Allwood, M. A., Ford, J. D., and Levendosky, A. (2021). Introduction to the special issue: disproportionate trauma, stress, and adversities as a pathway to health disparities among disenfranchised groups globally. J. Trauma. Stress. 34, 899–904. doi: 10.1002/jts.22743

Algahtani, F. D., Alsaif, B., Ahmed, A. A., Almishaal, A. A., Obeidat, S. T, Mohamed, R. F, et al. (2022). Using spiritual connections to cope with stress and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 915290. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.915290

Aloka, P. J. (2023). Academic resilience as predictor of academic adjustment among freshmen in distance learning programme at one public university. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 151–161. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.8151109

Ang, W. H. D., Shorey, S., Hoo, M. X. Y., Chew, H. S. J., and Lau, Y. (2021). The role of resilience in higher education: a meta-ethnographic analysis of students' experiences. J. Prof. Nurs. 37, 1092–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.08.010

Bantjes, J., Saal, W., Gericke, F., Lochner, C., Roos, J., Auerbach, R. P., et al. (2021). Mental health and academic failure among first-year university students in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 51, 396–408. doi: 10.1177/0081246320963204

Bila, N. J., and Carbonatto, C. L. (2022). Culture and help-seeking behaviour in the rural communities of Limpopo, South Africa: unearthing beliefs of mental health care users and caregivers. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 25, 543–562. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2022.2097210

Borodovsky, J. T. (2022). Generalizability and representativeness: considerations for internet-based research on substance use behaviours. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 30:466. doi: 10.1037/pha0000581

Branson, N., and Whitelaw, E. (2024). South African student retention during 2020: evidence from system-wide higher education institutional data. S. Afr. J. Econ. 92, 9–30. doi: 10.1111/saje.12361

Britt, K. C., Kwak, J., Acton, G., Richards, K. C., Hamilton, J., and Radhakrishnan, K. (2022). Measures of religion and spirituality in dementia: an integrative review. Alzheimer's Dementia Transl. Res. Clin. Intervent. 8:e12352. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12352

Cage, E., Jones, E., Ryan, G., Hughes, G., and Spanner, L. (2021). Student mental health and transitions into, through and out of university: student and staff perspectives. J. Furth. High. Educ. 45, 1076–1089. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2021.1875203

Cassidy, S. (2016). The academic resilience scale (ARS-30): a new multidimensional construct measure. Front. Psychol. 7, 1–17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01787

Cavilla, D. (2017). The effects of student reflection on academic performance and motivation. SAGE Open 7:2158244017733790. doi: 10.1177/2158244017733790

Chakradhar, K., Arumugham, P., and Venkataraman, M. (2023). The relationship between spirituality, resilience, and perceived stress among social work students: implications for educators. Soc. Work. Educ. 42, 1163–1180. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2022.2072482

Chankseliani, M., Qoraboyev, I., and Gimranova, D. (2021). Higher education contributing to local, national, and global development: new empirical and conceptual insights. High. Educ. 81, 109–127. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00565-8

Cherian, J., Kumari, P., and Sinha, S. P. (2021). Self-concept, emotional maturity and spirituality as predictors of academic resilience among undergraduate students. IJAR 7, 7–11. Available online at: https://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/2021/vol7issue1/PartA/7-1-6-936.pdf

Chikwana, A. (2018). Financial aid and the wellbeing of south African university students: a case study of NSFAS. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 32, 48–67.

Chou, C. Y., and Chang, C. H. (2021). Developing adaptive help-seeking regulation mechanisms for different help-seeking tendencies. Educ. Technol. Soc. 24, 54–66.

Cuncic, A. (2023). What to know about logotherapy: This type of therapy helps you find your purpose in life. Verywell Mind. Available online at: https://www.verywellmind.com/an-overview-of-victor-frankl-s-logotherapy-4159308

Davis, E. B., Day, J. M., Lindia, P. A., Lemke, A. W., King, S. N. S., Singh, K., et al. (2023). Religious/spiritual development and positive psychology: toward an integrative theory. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/waqd5

de Oliveira, C. F., Sobral, S. R., Ferreira, M. J., and Moreira, F. (2021). How does learning analytics contribute to prevent students’ dropout in higher education: a systematic literature review. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 5:64. doi: 10.3390/bdcc5040064

Dey, A. M., and Parayil, T. J. (2020). Spiritual life during testing times: how spirituality can help. Vinayasadhana 11, 27–33. Available online at: https://dvkjournals.in/index.php/vs/article/view/3237/2959

Du Plessis, C. F., Guse, T., and Du Plessis, G. A. (2023). “I am grateful that i still live under one roof with my family”: gratitude among South African university students. Emerg. Adulthood 11, 923–932. doi: 10.1177/2167696820970690

Edara, I. R., Del Castillo, F., Ching, G. S., and Del Castillo, C. D. (2021). Religiosity, emotions, resilience, and wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study of Taiwanese university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:6381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18126381

Engelbrecht, L., Mostert, K., Pienaar, J., and Kahl, C. (2020). Coping processes of South African first-year university students: an exploratory study. J. Stud. Aff. Afr. 8, 1–16. doi: 10.24085/jsaa.v8i2.4443

Engelbrecht-Aldworth, E., and Wort, A. R. (2021). The evolution of defining spirituality over the last century. Vir die Musiekleier/To the Music Director 41, 102–140.

Ezealah, I. Q. (2019). The role of self-reflection in the spiritual quest to make meaning of experiences : Clemson University.

Fernandes, E., Holanda, M., Victorino, M., Borges, V., Carvalho, R., and Van Erven, G. (2019). Educational data mining: Predictive analysis of academic performance of public school public-school students in the capital of Brazil. Journal of Business Research, 94, 335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.02.012

Fox, M. V. (2018). The meanings of the book of job. J. Bibl. Lit. 137, 7–18. doi: 10.1353/jbl.2018.0001

Fuertes, A. (2024). Students in higher education explore the practice of gratitude as spirituality and its impact on well-being. Religion 15:1078. doi: 10.3390/rel15091078

Gonzalez, M. B., Sittner, K. J., Saniguq Ullrich, J., and Walls, M. L. (2021). Spiritual connectedness through prayer as a mediator of the relationship between indigenous language use and positive mental health. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 27, 746–757. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000466

Gravetter, F. J., and Forzano, L. A. B. (2018). Research methods for the behavioural sciences. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Groves, P. (2021). “Spiritual and religious influences” in The handbook of alcohol use (Academic Press), 399–417. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-816720-5.00008-6

Gukurume, S. (2024). Pentecostalism, ontological (in) security and the everyday lives of international university students in South Africa. Afr. Ident. 22, 412–429. doi: 10.1080/14725843.2022.2034598

Harris, L. S. (2016). Effects of gender and spirituality on adults' resilience to daily non-traumatic stressors. (Doctoral dissertation): Walden University.

Ibáñez-Cubillas, P., López-Rodríguez, S., Martínez-Sánchez, I., and Rodríguez, J. Á. (2023). Multicausal analysis of the dropout of university students from teacher training studies in Andalusia. Front. Educ. 8, 116–120. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1111620

Imron, I., Mawardi, I., and Şen, A. (2023). The influence of spirituality on academic engagement through achievement motivation and resilience. Int. J. Islam. Educ. Psychol. 4, 314–326. doi: 10.18196/ijiep.v4i2.19428

Knoetze, J. J. (2022). Theological education, spiritual formation and leadership development in Africa: what does god have to do with it? HTS Teol. Stud./Theol. Stud. 78:1–6. doi: 10.4102/hts.v78i4.7521

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications. USA, NY.

Latif, S., and Amirullah, M. (2020). Students’ academic resilience profiles based on gender and cohort. Jurnal Kajian Bimbingan dan Konseling 5, 175–182. doi: 10.17977/um001v5i42020p175

Li, R., Che Hassan, N., and Saharuddin, N. (2023). College student’s academic help-seeking behavior: a systematic literature review. Behav. Sci. 13:637. doi: 10.3390/bs13080637

Mancini, C. J., Quilliam, V., Camilleri, C., and Sammut, S. (2023). Spirituality and negative religious coping, but not positive religious coping, differentially mediate the relationship between scrupulosity and mental health: a cross-sectional study. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 14:100680. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100680

Mapaling, C., Webb, P., and du Plooy, B. (2023). “I would help the lecturer with marking”: entrepreneurial education insights on academic resilience from the perspectives of engineering students in South Africa. Transf. Entrepr. Educ. 177:177–196. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-11578-3_10

Martin, A. J. (2013). Academic buoyancy and academic resilience: exploringevery day and classic resilience in the face of academic adversity. Sch. Psychol. Int. 34, 488–500. doi: 10.1177/0143034312472759

Marwala, T., and Mpedi, L. (2022). If we want to fix our economy, we must increase university graduation rates. Daily Maverick. Available online at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2022-11-29-if-we-want-to-fix-our-economy-we-must-increase-university-graduation-rates/

Masutha, M. (2022). Highs, lows and turning points in marginalised transitions and experiences of noncompletion amongst pushed dropouts in South African higher education. Educ Sci, 12:1–16. doi: 10.3390/edusci12090608

Mendoza, L. B. (2022). Impact of spirituality on academic performance of students. EPRA Int. J. Multidis. Res. (IJMR) 8:211–217. doi: 10.36713/epra2013

Moshtari, M., and Safarpour, A. (2024). Challenges and strategies for the internationalization of higher education in low-income East African countries. High. Educ. 87, 89–109. doi: 10.1007/s10734-023-00994-1

Murphy, K. R. (2021). In praise of Table 1: The importance of making better use of descriptive statistics. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14, 461–477. doi: 10.1017/iop.2021.90

Nyaruaba, R., Okoye, C. O., Akan, O. D., Mwaliko, C., Ebido, C. C., Ayoola, A., et al. (2022). Socio-economic impacts of emerging infectious diseases in Africa. Infect. Dis. 54, 315–324. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.2022195

Okechukwu, F. O., Ogba, K. T., Nwufo, J. I., Ogba, M., Onyekachi, B. N., Nwanosike, C. I., et al. (2022). Academic stress and suicidal ideation: moderating roles of coping style and resilience. BMC Psychiatry 22, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04063-2

O'Shea, S., May, J., Stone, C., and Delahunty, J. (2024). First-in-family students, university experience and family life: motivations, transitions and participation. Cham: Springer Nature, 294.

Otanga, T. O. (2023). Towards a Christian theology of African ancestors. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Pachón-Basallo, M., de la Fuente, J., González-Torres, M. C., Martínez-Vicente, J. M., Peralta-Sánchez, F. J., and Vera-Martínez, M. M. (2022). Effects of factors of self-regulation vs. factors of external regulation of learning in self-regulated study. Front. Psychol. 13:968733. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.968733

Pei, X., Jin, Y., Zheng, T., and Zhao, J. (2020). Longitudinal effect of a technology-enhanced learning environment on sixth-grade students’ science learning: the role of reflection. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 42, 271–289. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2019.1710000

Perez, J. A. (2021). The associations among gratitude, spirituality, and positive/negative affect: a test of mediation. Acad. Lasalliana J. Educ. Human. 3, 61–72.

Permatasari, N., Ashari, F. R., and Ismail, N. (2021). Contribution of perceived social support (peer, family, and teacher) to academic resilience during COVID-19. Golden Ratio Soc. Sci. Educ. 1, 01–12. doi: 10.52970/grsse.v1i1.94

Pillay, N., Ramlall, S., and Burns, J. K. (2016). Spirituality, depression and quality of life in medical students in KwaZulu-Natal. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 22:6. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v22i1.731

Pirnazarov, N. (2020). Philosophical analysis of the issue of spirituality. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 29, 1630–1632.

Ragusa, A., González-Bernal, J., Trigueros, R., Caggiano, V., Navarro, N., Minguez-Minguez, L. A., et al. (2023). Effects of academic self-regulation on procrastination, academic stress and anxiety, resilience and academic performance in a sample of Spanish secondary school students. Front. Psychol. 14:1073529. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1073529

Romano, L., Angelini, G., Consiglio, P., and Fiorilli, C. (2021). Academic resilience and engagement in high school students: the mediating role of perceived teacher emotional support. Eur. J. Invest. Health Psychol. Educ. 11, 334–344. doi: 10.3390/ejihpe11020025

Rossi, R., Jannini, T. B., Socci, V., Pacitti, F., and Lorenzo, G. D. (2021). Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown measures in Italy: association with mental health outcomes and age. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12:635832. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635832

Sagone, E., and Indiana, M. L. (2021). Are decision-making styles, locus of control, and average grades in exams correlated with procrastination in university students? Educ. Sci. 11:300. doi: 10.3390/educsci11060300

Sargeant, S., and Yoxall, J. (2023). Psychology and spirituality: reviewing developments in history, method and practice. J. Relig. Health 62, 1159–1174. doi: 10.1007/s10943-022-01731-1

Shube, I. M. (2020). Validation of the daily spiritual experience scale in a group of black South African students (Doctoral dissertation): North-West University (South-Africa).

Smith, B. W., and Bernard, M. L. (2023). Resilience through a spiritual lens: diverse perspectives and challenges. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 15, 290–302.

Swart, M. L. (2021). Understanding how hope manifests for South African youth during times of adversity (Master’s thesis): University of Pretoria (South Africa).

Teo, D. C. L., Duchonova, K., Kariman, S., and Ng, J. (2021). “Religion, spirituality, belief systems and suicide” in Suicide by self-immolation: biopsychosocial and transcultural aspects, eds. C. A. Alfonso, P. S. Chandra, and T. G. Schulze (Springer Nature Switzerland AG) pp. 183–200. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-62613-6_14

Thomas, T. A., and Maree, D. (2022). Student factors affecting academic success among undergraduate students at two south African higher education institutions. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 52, 99–111. doi: 10.1177/0081246320986287

Timmins, F., and Caldeira, S. (2019). Spirituality in healthcare: perspectives for innovative practice, vol. 10. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 978–973.

Troy, A. S., Willroth, E. C., Shallcross, A. J., Giuliani, N. R., Gross, J. J., and Mauss, I. B. (2023). Psychological resilience: an affect-regulation framework. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 74, 547–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-020122-041854

Underwood, L. G. (2011). The daily spiritual experience scale: overview and results. Religion 2, 29–50. doi: 10.3390/rel2010029

Underwood, L. G., and Teresi, J. A. (2002). The daily spiritual experience scale: development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann. Behav. Med. 24, 22–33. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04

Van Breda, A. D., and Theron, L. C. (2018). A critical review of south African child and youth resilience studies, 2009–2017. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 91, 237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.022

Van Cappellen, P., Edwards, M. E., and Shiota, M. N. (2023). The complexities of gratitude in resilience: cultural and individual variability. Emotion 23, 221–235.

Vardy, T., Moya, C., Placek, C. D., Apicella, C. L., Bolyanatz, A. H., Cohen, E., et al. (2023). “The religiosity gender gap in 14 diverse societies” in The evolution of religion and morality (London, UK: Routledge).

Villacís, J. L., de la Fuente, J., and Naval, C. (2021). Good character at college: the combined role of second-order character strength factors and phronesis motivation in undergraduate academic outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:8263. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168263

Yalcin-Siedentopf, N., Pichler, T., Welte, A. S., Hoertnagl, C. M., Klasen, C. C., Kemmler, G., et al. (2021). Sex matters: stress perception and the relevance of resilience and perceived social support in emerging adults. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 24, 403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00737-020-01076-2

Yang, S., and Wang, W. (2022). The role of academic resilience, motivational intensity and their relationship in EFL learners' academic achievement. Front. Psychol. 12, 1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.823537

You, S., and Lim, S. A. (2019). Religious orientation and subjective well-being: The mediating role of meaning in life. Journal of Psychology and Theology 47:34–47. doi: 10.1177/0091647118795180

Zhou, Z., Tavan, H., Kavarizadeh, F., Sarokhani, M., and Sayehmiri, K. (2024). The relationship between emotional intelligence, spiritual intelligence, and student achievement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 24:217. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05208-5

Keywords: spirituality, academic resilience, undergraduate students, university, South Africa

Citation: Lehihi TG, Tsabedze WF, Oduaran CA and Onyencho VC (2025) Exploring the spirituality and academic resilience among university undergraduate students. Front. Educ. 10:1671316. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1671316

Edited by:

Sajodin Sajodin, University of Aisyiyah Bandung, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Hazhira Qudsyi, Islamic University of Indonesia, IndonesiaZahida Aziz Sial, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Pakistan

Shigang Ge, Guangzhou Institute of Science and Technology, China

Copyright © 2025 Lehihi, Tsabedze, Oduaran and Onyencho. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Thuto G. Lehihi, dGh1dG9sZWhpaGlAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Thuto G. Lehihi, orcid.org/0000-0001-6554-578X

Wandile F. Tsabedze, orcid.org/0000-0002-6845-1460

Choja A. Oduaran, orcid.org/0000-0001-8815-3930

Victor Chidi Onyencho, orcid.org/0000-0001-7738-4020

Thuto G. Lehihi

Thuto G. Lehihi Wandile F. Tsabedze

Wandile F. Tsabedze Choja A. Oduaran

Choja A. Oduaran Victor Chidi Onyencho

Victor Chidi Onyencho