- 1National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

- 2Institute of Policy Studies, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Cross-sector educational partnerships are increasingly seen as critical levers for addressing educational inequities, with a growing shift from transactional support models to collaborative equity-driven ones. Community-based organizations are often involved in the support ecology for underprivileged youths to provide additional resources and services such as tutoring, school supplies, and access to technology. While such efforts appear to help reduce absenteeism and drop-outs, improve academic performance, and enhance general development and welfare, the role such organizations play is less examined in research. While international scholarship highlights equitable partnerships and independent community-based organization as part of a sustainable approach to support underprivileged students, less is known about how this unfolds in highly centralized, state-directed contexts. The paper addresses this gap by offering a Singaporean perspective where educational partnerships are shaped by a state-led developmental framework that privileges academic meritocracy and performance-based outcomes. Focusing on community-based organizations, the paper examines how those supporting underprivileged youths operate within the dominant “Learning as Social Service” model. This model provides remedial support to help students “catch up” and succeed within the existing system rather than address structural inequities. A critical discourse analysis on the annual reports of two key selected organizations of this model further explores their approaches, contributions as well as limitations of their partnerships to educational equity. The analysis reveals that while the organizations are well-placed to provide needed support for underprivileged youths, their work mainly falls within the frame of compensatory meritocracy that limits the equity pursuit by treating educational gaps as technical deficits rather than systemic issues. The paper argues for a reimagining of educational partnerships through the lens of collaborative governance and equity-centered practice—transformative approaches that center on community ownership, student agency and holistic development to address education disparities more effectively. By offering a Singaporean perspective on the intersection of educational equity and meritocratic culture, this paper contributes to the global discourse on how to strengthen equity in and through educational collaborations, particularly in outcomes-oriented, and highly structured environments.

Introduction

Educational partnerships have increasingly been positioned as vital levers for mitigating educational disparities and fostering systemic change in schools and communities. Such partnerships have been tapped to provide students from low-income backgrounds with tutoring, school supplies, access to technology, reduce absenteeism and drop-outs, improve academic performance, and enhance general development and welfare (e.g., Maier et al., 2017; van der Kleij et al., 2023).

In recent years, the field has shifted from transactional models of support toward more collaborative, equity-oriented frameworks that emphasize co-construction, mutual learning, and sustained engagement between schools, communities, and other actors (Penuel and Gallagher, 2017; Teemant et al., 2021). Such partnerships are most effective when designed to center equity—not only through targeted interventions, but through deeper relational infrastructures and shared ownerships. Key features include the centring of partners' voices (Hands, 2005, 2023), the inclusion of students as co-constructors (Mitra, 2014); shared decision-making and accountability (Henig et al., 2015); long-term commitment and solutions (Teemant et al., 2021); and collaborative leadership (e.g. Rubin, 2009).

Literature on educational partnerships from Anglophone countries often highlights community actors engaging as independent change agents or addressing systemic challenges through advocacy or root-cause interventions (e.g., Epstein, 1995; Sanders, 2001). These studies provide insights into one way that partnerships can be structured in decentralized contexts. In contrast, Singapore presents a perspective where partnerships take place within a state-led developmental framework that privileges academic meritocracy and performance outcomes (Tan K. P., 2008).

Within this system, community-based organizations are not oppositional actors but operate within state-sanctioned boundaries with educational partnerships shaped by state-mediated social policies and a highly regulated framework for public service provisions. Educational equity, while acknowledged in policy discourse, is primarily addressed through remediative strategies rather than structural reform—seeking to help disadvantaged students “catch up” rather than challenging the mechanisms that produce stratification. Yet the recent official emphasis on school-community partnerships place community-based organizations more firmly in the support ecology for students from low-income households indicating greater potential influence for the role of such organizations.

It should be mentioned that the word “community” is a conceptually rich and fluid term that is used in varied ways by different scholars. Epstein (1995) views community as a distinct yet interconnected part of the educational ecosystem, capable of influencing children's learning through formal and informal relationships and resources. Sanders (2001) elaborates that the community could include various actors who contribute to student learning and development such as business partners, social service agencies, faith-based organizations, and other civic groups. In the discussion of Singapore community-based organizations in this paper, we refer largely to the third sector that comprises many non-profit organizations such as social service organizations, social enterprises, and ethnic community-based organizations.

This paper contributes to the literature on educational partnerships by foregrounding the experiences of community-based organizations in Singapore. It represents an early collaborative effort between policy researchers working on the community sector and a social scientist researching education with the goal of exploring foundations for an educational equity network that brings together diverse partners across various sectors. An examination of the types of community-based organizations in Singapore reveals that they predominantly operate within a “Learning as a Social Service” paradigm which subscribes to compensatory meritocracy rather than questions and/or transforms the originating structures of inequity. Conducting a critical discourse analysis (CDA) on the annual reports of two key community-based organizations, each representing an important sub-category of the “Learning as a Social Service” model, the paper explores how these actors navigate the tensions between alignment with state priorities and aspirations and points to the potential for more transformative, equity-centered work. It examines how centralized governance structures, meritocratic norms, and performative pressures shape community-based organizations' roles and educational partnership practices, and what this means for the possibilities of equitable collaboration to enhance the equity ecology for disadvantaged students. Specifically, it addresses the two research questions: (1) How do community-based organizations' frame their role and partnerships in relation to Singapore's meritocratic narrative and what does this reveal about their approach to educational equity?; and (2) “How are key actors of educational partnerships represented in organizational discourses, and what implications do the representations have on modes of collaboration and equity?”.

The authors argue for a more nuanced understanding of collaborative governance that considers not only institutional capacity and coordination but also the relational, political, and discursive dimensions of partnerships operating in highly structured systems. The role of university researchers as knowledge brokers (Davidson and Penuel, 2019) who could facilitate the broader imagining of the “community” among stakeholders will also be explored. By offering a Singaporean perspective on the intersection of educational equity and performative culture, this paper contributes to the global discourse on how to strengthen equity in and through educational collaborations from the lens of community partners, particularly in fast-paced, outcomes-oriented, and highly structured environments.

Literature review

Educational partnerships and community organizations

Cross-sector educational partnerships have long been recognized for their potential to improve learning experiences and outcomes for underprivileged students. International literature on school-community partnerships, for instance, highlighted benefits such as improved academic performance (e.g., Heers and Van Klaveren, 2016; Epstein et al., 2002), enhanced cultural and social capital (e.g., van der Kleij et al., 2023) and reduced absenteeism and drop-out rates (e.g., Epstein and Sheldon, 2002). These outcomes are often enabled by pooling resources, knowledge, and networks across sectors, supporting a more holistic ecosystem of equity (Ainscow, 2015).

The rationale for involving community-based organizations in educational partnerships typically rests on the capacity to provide additional resources and expertise for holistic development of students while easing the growing demands on schools. Some frame community involvement as an extension of the instrumental purposes of education—preparing future workers aligned with economic development. Others emphasize the role of community partnerships in building social capital and supporting student wellbeing. While some regard community partnerships as crucial levers for school and educational improvement, others see them as avenues to contribute to the resilience and vitality of local communities. Indeed, scholars like Hands (2023) think that schools tend to marginalize low-income families even as they tried to assist them whereas community-based organizations, having a stronger relationship with and understanding of the families, could tap on community assets to support these families.

The literature suggests that while community-based organizations are not peripheral “stakeholders” but essential architects of equitable education, schools often steer the direction of educational partnerships determining partnership goals and occupying decision-making positions (Sanders, 2006). This school-dominant framing can obscure how asymmetries could limit the contributions of community partners. Examining partnerships through the lens of community-based organizations is thus vital to understanding both their role and constraints, as well as how these partnerships might be enhanced or reconfigured to advance educational equity.

Equity comprises fairness and inclusion, emphasizing the need for education systems to enable all individuals to reach their full potential regardless of background, while ensuring access to a minimum standard of education for all (OECD, 2012). Yet equity should not be conflated with equality. Whereas, equality focuses on uniform distribution, equity recognizes qualitative differences and focuses on responsiveness to structural disparities (Teng et al., 2019). This distinction is crucial for thinking about educational partnerships, as educational equity requires more than resource alignment. It demands transformation across several domains.

Scholars such as Ishimaru (2019) and Henig et al. (2015) argue that equitable partnerships must address issues of power, knowledge, representation, and governance. Equity entails more than equal participation or uniform resource distribution; it requires addressing historical and systemic disparities in decision-making, whose voices are heard, and which forms of knowledge are legitimized. Families and children/youths/students should also be positioned as active partners rather than passive beneficiaries in the equity ecology, to ensure ground impact on those the partnerships are supposed to cater to (Ozer, 2016; Valli et al., 2016; Ishimaru, 2019). Ainscow et al. (2013) notion of an “ecology of equity” captures the complex web of processes at work in the pursuit of educational equity which he encapsulated under “within schools,” “between schools” and “beyond schools.” The concept shifts the focus from “fixing” students to transforming schools and systems. It underscores the interconnections between educational and other sectors, and the importance of various actors, including the state, community-based organizations, corporates, schools, families and students—in shaping equitable ecosystems.

Successful partnerships depend not only on the resource exchange but also on relational infrastructure: shared vision, mutual trust, power-sharing, sustained leadership, and brokering actors who can bridge cultural and institutional divides, and “epistemic cultures” (Penuel and Gallagher, 2017) illustrated in research-practice partnerships scholarship. Research–practice partnerships (RPPs), for instance, exemplify a shift from transactional service delivery to collaborative governance, where schools, researchers, and communities co-construct knowledge and interventions aligned with local equity goals (Farrell et al., 2021). Such models recognize that systemic and sustainable change is shaped not just by technical solutions but also social dynamics, including who defines problems and what constitutes legitimate support.

Crucially, the formation and outcomes of such partnerships are deeply embedded in socio-political context. Norms around accountability, institutional autonomy, and the broader role of civil society all shape how partnerships are designed and enacted. While much existing research draws on Anglophone contexts where civil society is assumed to act as a check or complement to the state, the Singapore case offers a compelling counterpoint. The success of these partnerships, however, is deeply conditioned by local sociopolitical contexts.

The Singapore context

Singapore's governance model offers a distinctive context for studying educational partnerships. The state's strong regulatory and developmental presence in both the education and social sectors means that community-based organizations do not typically emerge in opposition to the state, but rather function within state-sanctioned frameworks. The consolidation of all local schools under the Ministry of Education (MOE) since independence in 1965 reflects the state's central role in shaping not only education policy but also how equity is conceptualized and operationalized.

Unlike the advocacy-driven role commonly associated with civil society organizations elsewhere, contemporary post-colonial Singapore presents a divergent model where the state is a strong presence in the social and educational sectors and shapes the operations in the sectors with top-down structures. Civil society exists within a communitarian logic where the third sector is expected to complement rather than confront state efforts (Ang, 2017).

Post-colonial restructuring in Singapore saw a diminishment of organic, community-initiated organizations in favor of state-linked grassroots bodies (or what some scholars termed as “parapolitical” entities) and statutory boards (Hill and Lian, 2013). The relationship between the Singaporean government and social sector has been described as “government-dominant,” with authorities exercising regulatory control through legal, institutional, and financial mechanisms to ensure accountability (Haque, 2018). Social sector organizations are now typically registered under state-regulated bodies and fall under the purview of the National Council of Social Service (NCSS), itself a statutory board of the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF).

Through funding schemes, networking platforms, and regulatory oversight, the state orchestrates much of the social sector's operation. In some cases, government officials sit on social organizations' advisory boards. Even as these organizations are tasked with serving the needs of vulnerable communities, they do so in ways that align with state priorities and are often framed as service providers rather than independent advocates. This has led to the description of them as apolitical organizations co-opted by the state (Tang, 2022).

Despite approximately 80% of social sector organizations operating under NCSS oversight, this arrangement does not signify a shift toward state welfarism (Haque, 2018). The Singaporean state has consistently resisted fostering dependency, wary of the “crutch mentality” that could arise from overreliance on government support. Instead, organizations in the social sector are often strategically positioned as service providers, facilitating the delivery of social services deemed necessary by the state. This dynamic fosters a subordinate—rather than antagonistic—relationship, wherein these organizations function as extensions of state priorities rather than as independent entities emerging to fill gaps left by state failures—a common scenario in many countries.

The authoritarian governance model in Singapore shapes both the education sector and educational partnerships. Academic meritocracy has framed Singapore's education as a fair system rewarding individual ability and effort (Tan C., 2008). Following independence, all local schools—excluding international institutions—were integrated into a national education system under the centralized oversight of MOE. As a developmental state with limited natural resources, Singapore strategically aligned education with economic imperatives, prioritizing the cultivation of human capital to meet labor market demands. Academic streaming and high-stakes examinations became key sorting mechanisms to efficiently allocate manpower.

This system has intensified competition with students often describing schools as “examination preparation centers” and “battlegrounds” (Heng and Pereira, 2020, p. 550–551). Perhaps unsurprisingly, this perspective of an “educational arms race” (Gee, 2012) has fueled a billion-dollar private tutoring industry, with the top 20 percent of households by income spending 4 times more than the bottom 20 percent (Department of Statistics Singapore, 2024). With the rise of “parentocracy” (Tan, 2019), the overrepresentation of the lower band of achievers with low socio-economic status (Wang et al., 2014), is a concern, particularly with declining intergenerational social mobility (Ng, 2014).

The Singapore state has for the longest time been providing disadvantaged students a leg up through the provisions of financial assistance and learning support schemes. More recently, the state's infrastructure enables partnerships through formal platforms and national programs, such as the Uplifting Pupils in Life and Inspiring Families Taskforce (UPLIFT), established in 2018. UPLIFT and its successor units in the MOE emphasize upstream interventions through support of the family and absenteeism reduction, indicating a stronger cross-ministry and cross-sector orientation to the pursuit of educational equality. Research has yet to emerge on the outcomes of such interventions.

With equity typically interpreted in the official discourse as “equality of opportunity” (Teng et al., 2019), interventions designed to help individuals better navigate the competitive examinations and performance-based sorting could be said to align with a logic of “compensatory meritocracy” that does not fundamentally alter the structure of the system. This way, they stop short of addressing the structural roots of inequalities that stem from unequal starting points, particularly along socioeconomic and ethnic lines (Tan, 2019; Tan C., 2008), or from early channeling of lower performing students into vocational educational pathways (Mardiana et al., 2020).

Community organizations that support low-income students thus must navigate a culture of performativity (Tan C., 2008), which can limit their work to remedial interventions rather than structural change. As such, many partnerships in Singapore reinforce compensatory meritocracy by offering academic enrichment and remedial support to help students “catch up” within existing systems, rather than questioning or transforming the structures that create inequity in the first place. The performative nature of Singapore's meritocracy also constrains young people's agency, especially those from less privileged backgrounds, making it harder to pursue flourishing lives (Teng and Layne, 2024). Top-down partnership structures compel cross-agency collaboration but do not necessarily foster relationships for sustainable collaborative work. For instance, one community-based organization reported that schools often treated community partners as vendors providing a service rather than as partners in student development (Ip, 2018). Additionally, despite years of community engagement, school-based counselors lack the familiarity with available community resources/services (Low, 2014), highlighting persistent disconnects in cross sector engagements.

The Singapore context offers unique insights on global discussions on community partnerships in education. In contrast to models where community-based organizations emerge to counter state neglect or policy gaps, Singapore demonstrates how such organizations can operate within a tightly regulated, developmental state framework. This raises important questions about autonomy, agency, and partnership dynamics in contexts where the state is both an enabler and gatekeeper. This paper therefore offers needed insights into how such cross-sector collaborations could be enriched by reviewing the role community-based organizations in Singapore play in contributing toward educational equity.

Landscape of community organizations focused on educational equity

Community-based organizations fall within the traditionally termed “Civil Society” or Social Service sector in a tri-sector partnership model, and are typically called charity-based, not-for-profit, non-governmental, philanthropic or voluntary-based organizations, based on their founding legacy (Salamon et al., 2003). To facilitate discussion around our research questions in this paper, we have re-categorized the relevant organizations that are key players in the educational equity ecology by function, purpose, course of action, positioning of partners and involvement of children and youth in collaborative governance. These are described in the five broad categories below:

Learning as a social service

Due to overprofessionalization, there has been a shift in focus from broader societal needs to individualistic models in the contemporary practice of social work. As highlighted by Kam (2014), this shift manifests in the increasing emphasis on clinical therapies, which can inadvertently neglect the social dimensions critical to fostering social justice. Findings from Apgar and Zerrusen (2024) also indicate that the focus of social work curricula has narrowed, and this limited focus can jeopardize the profession's ability to effect meaningful change at broader social levels, as the education of future social workers increasingly leans toward specialization at the expense of understanding systemic and structural dynamics. As such, there is a large group of organizations providing what we call “Learning as a Social Service,” which focuses on the direct provision of educational and developmental programs, services, and support to students and families.

A diverse group of organizations offer “Learning as a Social Service,” ranging from large, state-sanctioned institutions to specialized youth agencies and after-school care providers. This is the predominant category many organizations are classified in. Central to Singapore's model of social support and educational equity are the Ethnic Self-Help Groups (SHGs) based on the major ethnic groups: the Singapore Indian Development Association (SINDA), the Council for the Development of Singapore Malay/Muslim Community (Yayasan MENDAKI), and the Chinese Development Assistance Council (CDAC). These are unique, state-sanctioned organizations funded through a mandatory monthly contribution from the salaries of their respective community members, supplemented by matching government grants. Their mandate is to uplift their communities, with education as a primary lever for social mobility.

The structure and function of the SHGs reveal a core component of Singapore's social compact. They operate as a quasi-governmental layer of the equity ecosystem, delivering targeted welfare and educational services that are state-endorsed and co-funded but community-led. This model is a strategic choice, allowing the state to channel resources for specific interventions that address the historical, cultural, and socio-economic challenges unique to each community, which a centralized, universal system might struggle to do effectively. At the same time, it reinforces the national narrative of multiracialism, self-reliance, and shared responsibility. By framing the work of addressing ethnic disparities as a community-led effort supported by the state, this model fosters community ownership and delivers culturally contextualized support, from MENDAKI's preschool programs to CDAC's family support initiatives and SINDA's targeted tutorials.

Operating within the same space, aside from the SHGs, there are also a number of specialized agencies focusing on providing holistic support to youth, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds or facing significant adversity. These organizations operate on the principle that academic success is deeply intertwined with socio-emotional wellbeing and a supportive environment. Campus Impact exemplifies this approach, offering a multi-faceted support system that combines academic programs like homework supervision and small-group tuition with therapeutic services to help young people process emotions and resolve conflicts because unaddressed emotional stress is a significant barrier to learning. Impart Limited provides individualized support for youth at critical educational junctures, such as the years leading up to national secondary school leaving examinations. It integrates academics, career exploration, and financial literacy, while its Launchpad programme offers urgent, personalized academic intervention for those preparing for exams. Impart's model is particularly innovative in its approach to sustainability and community empowerment. Other agencies use innovative pedagogies to engage vulnerable youth. River Academy, for instance, caters to children from less-privileged homes (K1 to P6) using the Reggio-Emilia approach. This child-led, multidisciplinary method, which incorporates music, visual art, and drama, provides a learning experience that these children might not otherwise access, helping to build confidence and cater to diverse learning styles.

Informal education efforts

An important and distinct category of educational support has emerged from grassroots innovation and community action in recent years: entrepreneurial changemakers and resident-led community efforts. Though often informal and volunteer-driven, these efforts are deeply embedded in the lived experiences of local communities. Unlike professionally managed services, these initiatives rely more on social capital, trust and cultural norms of mutual aid. Within this larger category, a distinction can be made between initiatives spearheaded by entrepreneurial changemakers and those driven by residents. The latter manifests more closely to academic focused support programmes to improve students' literacy and numeracy (e.g., Readable), or structured homework support and study groups (e.g., EduHope SG). These efforts serve primarily to complement the existing education system and help underprivileged students catch-up academically. This stands in contrast to the organic, folksy, neighborly assistance that embodies a contemporary interpretation of the traditional “kampung” or community spirit, characterized by mutual aid, social cohesion, and communal child-rearing. This communal ethos is exemplified by leveraging shared spaces, such as Mdm. Sarinah's “Champs programme” at a Community Club, which provides complimentary tuition facilitated by volunteers from Yayasan MENDAKI; or Mdm. Marlina's “Community Fridge” which provides free food (e.g., vegetables, meat, snacks, milk) to address basic needs that support children's nutrition and school readiness.

Forging school-to-work pathways

Complementing the academically focused support systems are organizations dedicated to the crucial transition from education to employment. These groups broaden the definition of success beyond purely academic qualifications, creating and validating alternative pathways for young people, especially those who may not thrive in the traditional academic track. The YMCA of Singapore is a key provider in this space, offering a suite of programs tailored to diverse youth populations. They have a 6-month initiative designed for out-of-school youth and youth-at-risk (aged 14–21) to enhance their employability. Praxium, a social enterprise, is founded on the principle of “Praxis”—learning through action and application. They help young people aged 14–24 discover their purpose and passion, believing that this intrinsic motivation is key to navigating the future of work. The founder's own story underscores the value of out-of-class, passion-driven learning in building relevant career skills. Similarly, The Astronauts Collective (TAC) works to improve access to career knowledge and professional networks, providing mentoring and industry exposure for high-needs pre-tertiary youths from challenging backgrounds, connecting them with role models to explore careers and build motivation.

Policy research and advocacy organizations

These aim for systemic change through research, policy recommendations, and public awareness. Only a handful of organizations occupy this space, and they do not have close relationships with the state. The HEAD Foundation, an International Charitable organization in Singapore, functions as a thought leadership center. While its mission has broadened beyond Higher Education for Asian Development (HEAD) to include various aspects of education and healthcare, with an emphasis on improving lives in less developed parts of Southeast Asia, its contribution to educational equity in Singapore, though significant, is often indirect. The foundation supports projects that have maximum positive impact, such as early childhood education, STEM, and leadership training for educators. In contrast, Every Child SG is a grassroots advocacy group, founded by parents concerned about the Singaporean education system's ability to prepare children for the future. Led by parents, its explicit mission is to update the primary education system to be “future-ready,” fostering holistic attributes like creativity, critical thinking, resilience, and self-esteem alongside academic skills. The group's activities are directly aimed at systemic reform, evidenced by their White Paper, “Toward a Future-Ready Education System for Every Child,” and extensive public surveys. These surveys, with over 700 responses, indicate overwhelming public support for significant changes, including capping primary school class sizes at 25, making the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) optional, and increasing the number of specialized support staff like clinical psychologists and learning support educators in schools.

Alternative schooling systems

There are also organizations championing alternative educational systems such as home schools or democratic schools. These alternative child-centered schooling systems are often coupled with pedagogical approaches such as self-directed or collaborative learning that could better cultivate student agency and cater to individual student's needs offering a reprieve from the pressures of the conventional examination-oriented performative system and school environment, catering to families seeking such options. These families also created their own “ground up” network to share resources and offer mutual support. Organizations like Home School Singapore offer resources, consultations, and a community platform for the growing number of homeschooling families. While official statistics from the MOE (Ministry of Education, 2020) indicate that the number of homeschooled children at the primary level (regulated under the Compulsory Education Act) has remained small and stable at around 50 children per cohort. Driving this niche community are organizations that offer resources and support. Little U functions as a microschool consultancy, specializing in personalized education and running its own microschool, “The Learnery.”

Critically, it directly confronts the perception that such alternatives are only for the affluent by stating its services are “affordable even for low-income families.” Furthermore, it addresses the challenge of credentialing by preparing homeschooled teens for college, using a competency-based record that moves beyond traditional grades. The government's policy of permitting homeschooling, while subjecting it to rigorous approval and monitoring processes (including curriculum plans and annual progress reports to MOE), acts as a strategic management tool. It accommodates a small but often vocal minority, allowing for diversity at the margins without fundamentally altering the standardized, meritocratic core of the national system.

Simultaneously, the very existence and the arguments put forth by these groups serve as a living critique of the mainstream system's potential limitations. Their emphasis on flexibility, personalized learning, and student wellbeing implicitly highlights areas where the conventional model may fall short for some learners. A key challenge in the meritocraticacy narrative that has guided Singapore's educational planning to date, is that privilege to different groups of students and their families does not look the same. In many cases, it is difficult for the state to act on these disparities without available data-driven evidence to accommodate these suggestions. For example, local academics such as Dr. Susan Rickard-Liow conducted many important studies with children learning Malay in Singapore (Rickard Liow and Lee, 2004; Jalil and Liow, 2008) to use data to demonstrate to parents, medical doctors and educators why it is inappropriate to misdiagnose Malay speaking children as being dyslexic or language-delayed due to initial differences in their English spelling abilities. The primary challenge for this sector as a whole remains broader societal acceptance, given that unconventional pathways are often still viewed as a last resort rather than a proactive choice.

Methodology

This study employs a qualitative research design using Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) to investigate how partnerships involving community-based organizations contribute to educational equity in Singapore. CDA is a well-established qualitative research approach that systematically examines language in use within social and political contexts, focusing on how discourse shapes and is shaped by power relations, ideologies, and social structures (Fairclough, 2013; van Dijk, 2001). Particularly concerned with how unequal power relations are enacted, reproduced, legitimized, and resisted by text and talk, CDA involves analyzing not only the explicit meaning of discourse but also the underlying ideological assumptions and social relations embedded in language (Sibley-White, 2019). The main assumption is that language is both reflective and constitutive of social realities and thus are worthy of analysis (Wood and Kroger, 2000). As a research tool, CDA is widely used in diverse fields such as political science, sociology and linguistics as it allows researchers to analyze texts in a systematic manner to unpack complex institutional discourses (Chouliaraki and Fairclough, 2010).

The present study employs a CDA approach to examine patterns of language use vis-à-vis structures of power through an examination of the most recent Annual General Reports of two selected community-based organizations published in 2024. Prior scholarship demonstrates that annual reports of institutions are multi-voiced texts that strategically recontextualize organizational activity (e.g., van Leeuwen, 2013) for funders, government agencies and the public. Precisely due to their curated nature, what is foregrounded or left unsaid in the authoritative self representational texts can point to the organization's self-positioning in the broader ecosystem, ideological alignments and the power dynamics with clients. Omissions and euphemisms can be as revealing as the narratives they contain. For instance de Salvo (2020) suggests how intergovernmental organizations obscure systemic failures by highlighting simplified solutions in their reports. Given that CDA relies on a nuanced understanding of systematic theory and relationships within Singapore's educational ecology, we elected to conduct an in-depth analysis of the latest annual report from each organization which suffice for our purposes as the discourse does not shift much through the years. It is not uncommon for research engaging CDA to focus on intensive analysis of a single text to gain in-depth insights (e.g., Wodak and Meyer, 2009; Gee, 2014). Thus, for an exploratory study like this where there is little local preceding research in this area, two annual reports from two organizations enable sufficient analysis that have implications for future research and cross-sector collaborations to enhance educational equity. Given the funding and regulatory framework that community-based organizations in Singapore operate within, as well as the dominant official educational and social discourses they have to navigate around, topics such as power relations and inequality are less likely to generate forthcoming responses in more interactional research approaches. The choice of CDA thus offers a more fruitful approach as an initial stepping stone to uncover underlying sociopolitical ideologies and patterns that elucidate how partnerships, power and policy are situated in the context of the Singaporean educational ecology.

At this point, however, we like to acknowledge how our approach could have limited the potential benefits of triangulation with varied data sources such as program data and observations. This is something that should be addressed in future studies to advance research in the area.

As with other qualitative research tools, in CDA, the researcher is the instrument through which the data are interpreted. Reflexive dialogue between the authors on data framing was carried out with mindful avoidance of deficit approaches to ensure researcher bias was minimized, especially given that all researchers were educated in Singapore and are at a privileged position within local universities, writing about equity for the underprivileged within the same system.

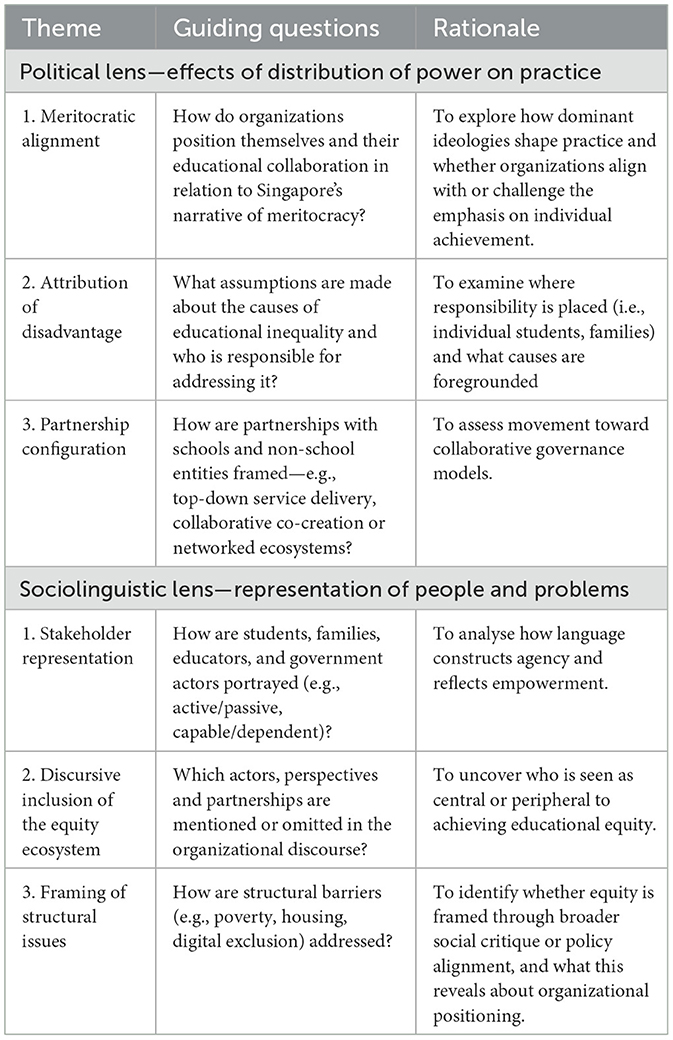

For the purposes of this paper, we opted to use a coding framework (please refer to Table 1) employing dual lenses (the Political and the Sociolinguistic) to code the texts informed by guiding questions derived from the two research questions: 1. “How do community-based organizations” frame their role and partnerships in relation to Singapore's meritocratic narrative and what does this reveal about their approach to educational equity?; 2. “How are key actors of educational partnerships represented in organizational discourses, and what implications do the representations have on modes of collaboration and equity?”. The Political lens and the Sociolinguistic lens were selected to ensure a comprehensive framework through which we could read the same text to understand the intent behind the words used in these narratives. While the Political and Sociolinguistic lenses both examine how discourse might reflect or reinforce ideological concepts such as meritocracy and equity, the focus of each lens is different. The Political lens offers a broader conceptual frame which focuses primarily on institutional roles and power (i.e., what organizations do and why). On the other hand, the Sociolinguistic lens focuses primarily on framing and positioning, which allows us to glean insights into representations of actors and problems (i.e., how organizations justify their programming). Employing dual lenses in our guided coding framework allows the excavation of layered insights that might surface any tensions or contradictions that community-based organizations demonstrate with regards to educational equity. Our goal with this analysis plan is to explain what is being said and what that narrative might reveal about the social and institutional context within which these Singaporean community-based organizations operate.

Two members of the research team conducted the initial coding according to their disciplinary training, with a political scientist coding under the “Political” lens and a psycholinguist coding under the “Sociolinguistic” lens. Both researchers independently read the same texts and coded for the specific themes within their assigned research frame. This division of labor ensured coding was grounded in disciplinary knowledge while maintaining exposure to the same data corpus. To enhance interpretive consistency and strengthen inter-coder reliability, the researchers engaged in iterative cross checking. After their initial coding round, they discussed and compared how the same passages were interpreted through the Political and Sociolinguistic lenses. Through this process, overlaps or divergences were identified, potential blind spots and assumptions were interrogated, refining the coding scheme and co-construction of key themes. The process aligns with CDA traditions that emphasize negotiated interpretation and reflexivity over mechanical reliability metrics (Phillips et al., 2008).

Case study selection

Among the various community-based organizations addressing educational inequality, those in the “Learning as a Social Service” category are most commonly viewed by parents and guardians as the first line of support for improving social mobility for their children. While these organizations typically operate as service providers which view their role as agencies that supplement and complement the existing, state-governed educational system, the same can be said of other organizations with a more policy research and advocacy driven mandate (see Appendix A for a table of community-based organizations operating in Singapore).

Given the authoritarian context in Singapore, it is more pragmatic to examine organizations that operate within the dominant paradigm to explore their potential for advancing educational equity. This is because the funding structure and organizational mandate make it easier for organizations to focus on their mission of improving educational equity. As the literature suggests, partnerships may range from compensatory or systemic; transactional or relational—highlighting the importance of careful selection to enable meaningful comparison. To understand how existing partnerships for educational equity function, we selected one organization from each sub-category within the “Learning as a Social Service” type to analyse: SINDA (SHG sub-category), and SHINE (specialized sub-category).

SINDA and SHINE were chosen as case-studies due to their influence and reach. SINDA has reached over 28, 000 individuals annually and engaged with high-level partnerships with the Ministry of Education and other self-help groups (SINDA, 2025); while SHINE has maintained over 200 community partners and received strategic appointments by the government to operate two key youth outreach programmes on mental health, Youth Community Outreach Team (CREST-Youth) and Youth Integrated Team (YIT), in the same region (SHINE, 2024). Additionally, researcher familiarity was another reason for selection. A key member of our research team—the Head of Department at the Institute of Policy Studies' Policy Lab—was invited to serve on their research committees to provide guidance. The inclusion of policy researchers to provide evidence-based suggestions reflects a willingness to collaborate with academics and engage in evidence-informed practice aimed at improving educational equity in Singapore.

Singapore Indian Development Association

Established in 1991, SINDA is a ethnic self-help group for the South Asian diaspora (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Sri Lankan) in Singapore that focuses on education and social mobility. The founders included members of parliament and Director of Welfare at then Ministry of Community Development. As mentioned in Appendix A, Ethnic-based Self-Help Groups are unique to Singapore and are dedicated to uplifting the Singaporean South Asian community by fostering a well-educated, resilient, and confident populace. SINDA aspires to “journey with families and individuals to help them reach their aspirations, creating a thriving community for all”. While SINDA's initial and primary focus was on tackling educational underperformance through tutorial programs, over the decades, SINDA has evolved significantly, broadening its mission to encompass a more “holistic” approach that extends beyond academics. This expanded focus now includes inspiring youth through mentorship, building stronger families via support services, and providing community assistance with financial aid schemes.

SHINE Children and Youth Services

Originating in 1976 by Mr Francis Thomas, then-principal of St. Andrew's School, who envisioned a support system for students with academic potential hindered by personal or environmental difficulties. The initial focus was squarely on school-based support to help these students succeed. The organization has evolved into a multifaceted agency focused on children and youth development. This transformation involved expanding its services to include professional school social work, educational psychology, community outreach patrols to prevent youth crime, intensive individual and family therapy, and most recently, an innovative long-term mentoring programme designed to break intergenerational poverty. This strategic evolution from a specific student-centric service to a comprehensive support system demonstrates SHINE's commitment to furthering their cause “to be a leading social work organization in enabling children and youths to maximize their potential.”

By studying two well-established organizations with a long history in Singapore—one closely aligned with MOE (SINDA), and the other more embedded in open collaborative community-based youth work with peer organizations (SHINE). The examination of the nature of partnerships within the “Learning as a Social Service” group offers insights into how partnerships manifest in relation to Singapore's meritocratic framework and how they respond to educational disparities.

Findings

Positioning as complementary state-endorsed service providers for beneficiaries

As organizations operating within the paradigm of “Learning as a Social Service,” both SINDA and SHINE play important roles in facilitating access to information, financial aid, supplementary academic programs, wellbeing programs and mentorship. There is a strong emphasis on “uplifting” underprivileged students through academic support. SINDA, for instance, pointed to its contribution to existing school operations through its after-school tutorial programme, STEP (SINDA, 2025, p. 18), and school-based tutorial programme, TEACH (SINDA, 2025, p. 18).

It is also evident from the annual reports of both organizations that they have an integral role within a larger eco-system of support that consists of state actors, non-profit and private sector actors, with schools, religious organizations, residents' committees and even corporates among others cited as partners. For instance SINDA collaborates with the Ministry of Social and Family Development to facilitate government financial schemes (SINDA, 2025, p. 58), the partnering of the Singapore Press Holdings Foundation for newspaper access (SINDA, 2025, p. 58) and the Health Promotion Board for nutritious food distribution (SINDA, 2025, p. 68). SHINE works with the Ministry of Education office specifically supporting students from underprivileged backgrounds (SHINE, 2024, p. 26) and it is also appointed by the Agency for Integrated Care established by the Ministry of Health to deliver a youth mental health awareness and prevention programme (SHINE, 2024, p. 30).

The legitimizing power of these named partnerships is prominently featured in the annual reports. The STAR programme's launch was “graced by the STAR Champions, Deputy Prime Minister Mr Gan Kim Yong, Senior Parliamentary Secretary Eric Chua, and Adviser Don Wee, alongside other key stakeholders and partners from MOE UPLIFT Programme Office, People's Association, South West Community Development Council, Octava Foundation and The Moh Family Foundation” (SHINE, 2024, p. 27) publicly embedding the programme within top-tier political and community support networks. Moreover, SHINE underscores its deep institutional integration by proudly noting it was “awarded the Minister for Home Affairs National Day Award 2023 for our close partnership with the Home Team” (SHINE, 2024, p. 26), directly linking its outreach success to strong governmental ties.

The merits in the state's strong presence in such partnerships is the efficiency of the mobilization of resources and manpower and perhaps also the need for the organizations' accountability to public money.

Remediative support within state endorsed meritocracy

For organizations like SINDA and SHINE operating within Singapore's pervasive meritocratic framework, their foundational work inevitably aligns with this ideology. This alignment inherently shifts the focus of intervention toward individual and familial circumstances, effectively depoliticizing the broader structural factors contributing to educational and social inequality.

SHINE's programmes, such as the STAR initiative, explicitly articulate goals within this meritocratic paradigm. It was “launched to ensure children from disadvantaged circumstances have access to opportunities to succeed and achieve the goal of social mobility” (SHINE, 2024, p. 2). This language squarely places the onus on the individual child to succeed through provided opportunities, echoing the national emphasis on upward mobility through personal effort. Even when acknowledging background factors, the solution offered is individualized; for instance, in supporting a child named Alice, SHINE noted a key challenge: “As Alice's mother did not speak much English, Alice had limited exposure to the language or reading at home.” (SHINE, 2024, p. 27). SHINE's programmes, such as the STAR initiative, explicitly articulate goals within this meritocratic paradigm. It was “launched to ensure children from disadvantaged circumstances have access to opportunities to succeed and achieve the goal of social mobility” (SHINE, 2024, p. 27). The intervention then became about providing direct support to Alice to “maximize her education potential” (SHINE, 2024, p. 27), rather than addressing systemic linguistic support or integration for families.

SINDA's approach mirrors this strong alignment with meritocratic ideology. Its mission—“To build a well-educated, resilient and confident community of Indians that stands together with the other communities in contributing to the progress of multi-racial Singapore” (SINDA, 2025, p. 1)—links community uplift to individual educational attainment and resilience, framed within a national progress narrative. This is evident in the SINDA Annual General Report, which opens with statistics highlighting Indian students‘ achievements in national examinations, such as the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE), General Cambridge Examination Normal, Ordinary and Advanced Levels (SINDA, 2025, p. 7–12). Many of SINDA's programmes support the school syllabus with the aim to improve students' academic performance. Its academic offerings are designed to “provide the curricula and resources they need to enhance their academic performance and increase their potential, despite family, social, or economic circumstances” (SINDA, 2025, p. 13) suggesting that individual effort, bolstered by SINDA's resources, can overcome personal challenges. While SINDA does acknowledge and address financial hardship, it frames this as a barrier to individual educational access rather than a symptom of systemic economic inequality. This is evident in the two mentions of financial hardships: “SINDA bursaries offer education-related financial assistance to low-income and deserving families” (SINDA, 2025, p. 57) and “Easing the financial burdens of families, Back to School Festival Kits provide students with stationery and shoe vouchers” (SINDA, 2025, p. 57). These interventions are designed to alleviate individual family burdens to enable participation in education.

This approach places responsibility for success on individuals and families with minimal attention to broader structural barriers. Those unable to “catch up” are seen as needing specialized, expert help—reinforcing a model of compensatory meritocracy while the role of the state and larger community is to provide additional individual-level support to those who are falling behind. There is little or no attention on fixing the system itself; the analogy is to fix, train, or equip the players who are not doing so well, instead of modifying the game itself to be more fair.

For SINDA, the meaning of holistic support, whilst broadly encompassing, is actually stacked on services designed to help youth do well academically, with other forms of support serving as enablers. Tuition is prioritized to support academic outcomes. But services are stacked to ensure family issues, behavioral issues, and/or financial issues which could get in the way are addressed to pave the way for improvement in academic performance. This is implicitly driven by key performance indicators that often track the academic achievement gap between Indian students and others (SINDA, 2025, p. 7–12), solidifying the focus on academic results. Furthermore, many service providers care about education because they are aligned with the preparation of a workforce that will deliver economic growth, thereby supporting school-to-work pathways. SINDA, for example, proudly highlights its industry mentorship through collaboration in the Indian Business-Leaders' Roundtable (SINDA-IBR), which “draws on its members' vast experience, expertise and networks to uplift the Singaporean Indian community… [offering] multidimensional support that covers financial help, student mentorship and career opportunities” (SINDA, 2025, p. 67) directly linking educational support to economic contribution. However, the omission or softening of the structural causes of inequality within the narrative, glorifies individual achievement. This makes their families, and the students themselves believe in the narrative of meritocracy. In this way, there is little push for systemic change from the most vulnerable within the system, given that the system has demonstrably uplifted their own children.

Varying degree of collaborative governance

While both SINDA and SHINE extensively engage other entities and explicitly state their commitment to collaborative efforts, the nature of these collaborations does not yet consistently extend to deeper co-creation or shared decision-making, hallmarks of robust collaborative governance in equitable partnerships (Henig et al., 2015). This distinction lies in whether partners collectively set strategic agendas and diffuse power, or primarily contribute to the execution and scaling of pre-defined initiatives.

Both organizations consider themselves to be collaborative and indeed maintain a multitude of partners. SHINE proudly declares:“We are especially proud of our collaborative efforts with government agencies, community-based organizations, and stakeholders. Together, we have strengthened our outreach and expanded our services, ensuring that no child is left behind. Our partnerships have allowed us to leverage resources effectively and share best practices, ultimately enhancing the quality of support we provide“ (SHINE, 2024, p. 2). This statement, like many in non-profit annual reports, serves as a testament to their broad network. Similarly, SINDA asserts: “From community and grassroots organizations to religious and ethnic groups, we forge collaborations with all, tapping our collective resources and expertise to engage individuals in the community and fuel our outreach efforts“ (SINDA, 2025, p. 61). They also highlight “strong collaborative partnerships between schools, parents and teachers” (SINDA, 2025, p. 18) for their Teach programme and “strong partnership with community stakeholders such as schools, religious organizations and residents' committees” (SINDA, 2025, p. 18) for The Guide programme. In both organizations, there is a significant degree of control over programme conceptualization and execution for their target clients. In SINDA, students, parents, and community members are consistently and almost exclusively, represented as beneficiaries of support, whilst the organization and its partners are robustly depicted as the active, initiating agents providing it. The discourse clearly positions SINDA as the orchestrator of interventions, as seen in statements like: “SINDA works to realize the potential in every child. Designed to meet the varied learning abilities and capacities of each student, our academic programmes provide the curricula and resources they need to enhance their academic performance and increase their potential, despite family, social, or economic circumstances“ (SINDA, 2025, p. 13). Similarly, SINDA's programmes are described as “champion[ing] the development of Indian youths, nurturing them to fulfill their potential and achieve success. Through customized motivational and mentorship programmes, we instill positive values, shape good character and build confidence to develop youths, and help them flourish in positive peer circles and emerge as capable, well-adjusted adults“ (SINDA, 2025, p. 23). Even volunteer involvement is framed within SINDA's initiatives, where “A total of 411 tutors were part of SINDA's educational initiatives“ (SINDA, 2025, p. 14) underscoring their integration into the organization's pre-defined framework. This consistent linguistic pattern firmly establishes SINDA as the primary designer, orchestrator, and ultimate authority over its interventions, with clients largely positioned as beneficiaries.

A nuanced difference emerges when comparing the depth of co-creation and agenda-setting. SINDA appears to have more carefully curated its partnerships, operating with a more defined set of actors who primarily contribute to SINDA's pre-existing programmes and objectives. Their collaborations often focus on “tapping our collective resources and expertise to engage individuals… and fuel our outreach efforts” (SINDA, 2025, p. 61) implying a focus on expanding the reach of SINDA's own agenda rather than jointly developing new ones. For example, the “Joint Learning Fiesta served as a platform for SHGs to share best practices with tutors” (SINDA, 2025, p. 22) which, while collaborative, is framed around improving the delivery of existing academic support.

SHINE, on the other hand, allows for more explicit co-creation and space for other organizations' agendas, particularly at the programme conceptualization level. There is stronger evidence that they create environments where power is more distributed and decisions are made together in specific contexts. The most compelling example is in the conceptualization of their flagship STAR programme: “SHINE, together with RFI, OF, and Ministry of Education UPLIFT Programme Office (MOE UPO), formed a work group and embarked on the journey to conceptualize such a programme in Singapore“ (SHINE, 2024, p. 26). This demonstrates a multi-stakeholder work group actively involved in the genesis of a programme's design. Partners are not merely portrayed as funders or implementers, but as active participants in the conceptualization and strategic design of new initiatives, indicating a higher degree of co-creation than simply supporting existing ones. Furthermore, SHINE's Youth Community Development Team (YCDT) aims to strengthen partnerships by “Growing alongside partners by mutual sharing of resources, expertise and networks, we hope to bring about greater impact in the community through youth volunteerism” (SHINE, 2024, p. 33). The phrase “growing alongside partners by mutual sharing” in particular, signifies a more reciprocal and potentially co-creative dynamic in future collaborations. In addition, whilst also operating from a professional-led stance, SHINE holds space for partners to co-develop services, which are still primarily done for youths, making them less youth-directed or led in a strategic sense. For instance, the MOE teacher who is a teacher on the Youth Community Outreach Patrol (COP), a youth outreach programme stated, “The team from SHINE have been more than just a partner; they have been an integral part of our Youth COP family” (SHINE, 2024, p. 29) suggesting a deep embedding within the school's structure, yet still as an “integral part” of their existing “family.” However, despite these instances of co-development and integration, the overall service delivery retains a strong professional, top-down leadership, with SHINE often being the lead organization responsible. For example, in Youth COP, “SHINE Social Workers recruit and equip youth with the necessary skills, knowledge and attitudes to serve alongside the Police Officers” (SHINE, 2024, p. 28) clearly defining SHINE's role as the implementer for youth.

Furthermore, a nuanced difference can be observed in how each organization refers to its partners. SHINE tends to explicitly name a wider array of specific corporate, philanthropic, and governmental entities in relation to specific programme genesis and expansion, actively underscoring their integral and active role in shaping and supporting SHINE's work. For example, SHINE highlights that “the timely partnership with Research for Impact (RFI) and Octava Foundation (OF) and their White Paper: Toward Greater Equity Among Young Learners in Singapore also reinforced SHINE's findings” (SHINE, 2024, p. 26). This clearly demonstrates partners' contribution to the very intellectual and empirical foundation of SHINE's programmes, lending external validation and academic rigor.

Beyond traditional support, SHINE's narrative details how partners contribute to its capacity and strategic execution. Its collaboration with the Development Bank of Singapore (DBS) via Project V, a national pilot project involving multiple government and social service agencies, exemplifies large-scale, multi-agency strategic volunteering. Not only did DBS volunteers “enable service delivery through smooth execution of the programmes and allowed more beneficiaries' needs to be met” (SHINE, 2024, p. 39) but they also engaged in “skills-based volunteering by conducting social media workshops for SHINE staff and interns” (SHINE, 2024, p. 39) and “mentoring a group of SHINE communications interns” (SHINE, 2024, p. 39). This illustrates a diversified, capacity-building support that goes beyond mere funding or simple service delivery, indicating a more reciprocal flow of expertise. Furthermore, SHINE explicitly details how “Partnerships with educational and medical institutions, government agencies, non-profits, and volunteers to ensure we have a functioning ecosystem to render effective help…supported us via training, co-management of cases, resourcing and more, thereby enabling us to scale and sustain our efforts. There were also opportunities to share our learnings from research and evaluation to promote greater social-health-technology integration in our service delivery” (SHINE, 2024, p. 31). This complex interplay, involving co-management of cases and mutual sharing of research learnings, points toward a more robust, integrated, and potentially co-governed operational model. This contrasts with partners primarily operating within an organization's existing, pre-defined initiatives, positioning SHINE's approach as leaning more toward collaborative strategy and shared credibility.

Student positioned as passive beneficiaries rather than co-creators

However, organizations might list many partnerships—sometimes as a badge of honor—but having partnerships does not automatically mean they share decision-making with their partners, stakeholders, or their clients, the children and youth themselves. The evidence suggests that many of these collaborations are instrumental, focusing on efficient service delivery rather than joint strategic governance. For instance, SHINE's partners “supported us via training, co-management of cases, resourcing and more, thereby enabling us to scale and sustain our efforts” (SHINE, 2024, p. 31) indicating a supportive role for SHINE's existing initiatives. Similarly, DBS volunteers with SHINE “enabled service delivery through smooth execution of the programmes and allowed more beneficiaries' needs to be met” (SHINE, 2024, p. 39) highlighting execution rather than co-design. SINDA's description of “411 tutors [being] part of SINDA's educational initiatives (p. 21)” and “corporates… support[ing] tertiary-level students” (SINDA, 2025, p. 27) also points to partners providing support within SINDA's established frameworks. These examples demonstrate collaborations that enhance programme delivery but do not inherently signify shared strategic oversight or decision-making. Existing literature suggests that including youths in the actual development and implementation processes rather than mere consultation can be more inclusive and fruitful (Hands, 2014).

A subtle difference in the way that these two organizations refer to their clients reveal some indication about their beliefs regarding their level of autonomy. For instance, SINDA tends to regard their clients primarily as “students” while SHINE looks at them as “youths”; which signals the latter's assumed maturity relative to the broader term “children.” There are also instances of youth involvement in content development: “Through the attachment [of Temasek Junior College students], students attempted at the development of youth volunteer training modules and presented their learnings on volunteer management” (SHINE, 2024, p. 33) which indicates space for their direct input into programme elements. Whilst SHINE ultimately remains the lead agency delivering services for youths, these instances suggest a greater openness to collaborative agenda-setting and shared development, moving beyond mere resource provision or execution.

Discussion and recommendations

Limits to addressing systemic issues in complementary models

While community-based organizations like SINDA and SHINE exemplify the complementary model of partnerships, offering much-needed supplementary support, their work is shaped by the centralized governance of structures and performative meritocratic logics that define Singapore's educational system. Their resources and multiple partnerships place them in good positions to offer remediative support in the short term. But partnership efforts often could not go beyond the compensatory meritocratic frame of helping students “catch up” in a performance-driven system that inadvertently reinforces rather than challenges the dominant meritocratic narratives. For instance, SINDA's collaborative efforts at the Indian Business-Leaders' Roundtable (SINDA-IBR) links educational support to employability and workforce readiness aligning with state-defined priorities around economic productivity. The report notes that it “draws on its members' vast experience, expertise and networks to uplift the Singaporean Indian community. Today, IBR and its 176 members surround SINDA's beneficiaries with multidimensional support that covers financial help, student mentorship and career opportunities” (SINDA, 2025, p. 67). Such instrumental orientation to equity treats educational gaps as technical deficits to be managed rather than structural inequalities to be dismantled.

Rather than operating as true partners with equal stakes in the partnership, many entities within the existing education system function more as vendors to the schools, delivering predetermined, and often piecemeal, services without deeper collaboration or shared strategic vision. This transactional dynamic often manifests in a strong emphasis on programmatic interventions, particularly those geared toward academic outcomes. Many of these include widespread tuition programs aimed at improving grades and auxiliary support initiatives designed to bolster socio-emotional development and resilience, all with the underlying goal of enhancing scholastic achievement. Furthermore, the pronounced focus on facilitating school-to-work pathways, is largely driven by the imperative of supporting broader economic development. This emphasis on vocational training and career preparation highlights a utilitarian approach to education and service provision, where the primary objective is to equip individuals with skills directly applicable to the workforce. While undoubtedly crucial for economic growth, this singular focus might inadvertently overshadow other equally vital aspects of holistic development and societal wellbeing. The challenge lies in expanding these limited degrees of freedom, transforming vendor-client relationships into genuine partnerships, and broadening the scope of service provision beyond a purely economic and academic lens to encompass a more comprehensive understanding of individual and community needs.

In the long run, partnerships efforts by learning service providers involved in compensatory meritocracy risk sponsoring and even contributing to the private tuition industry. Affluent parents can continually outpace these interventions by investing in premium services as evidenced by the “massive S$1.8 billion commercial private tuition industry” (Tushara, 2025). In mitigating gaps through subsidized or group tuition rather than seeking systemic reforms to reduce reliance on private tuition, market inequities are accepted as inevitable and their consequences merely to be managed. Over time, the community sector risks becoming a safety valve for systemic gaps, normalizing stratified outcomes while limiting opportunities to reimagine more inclusive structures.

Addressing educational equity beyond the paradigm of compensatory meritocracy

Although both selected organizations examined above belong to the “Learning as Social Service” category, SHINE demonstrates the possibility of going beyond mere service delivery by holding co-creation space for partners, resulting in more meaningful collaborative governance and mutual learning. The organization's openness to involving youths in agenda setting is also promising. Its approach suggests there is room for mindful ways of designing programs and partnerships beyond mere subscription to compensatory meritocracy. It is unclear whether SHINE's greater openness signifies an emerging trend in the sector or if it is an isolated case. Perhaps the more distant proximity to the state allowed more space for SHINE to maneuver compared to SINDA. Future research can investigate the factors and enablers that led SHINE to do things a little differently from other organizations in the “Learning as Social Service” group to understand how the equity network the authors are part of can work with these organizations to explore different approaches to equity and collaborative governance.

While the landscape of educational support is predominantly made up of service providers complementing the existing paradigm, there is untapped transformative potential of approaches espoused, say, by alternative and democratic schools and policy advocacy organizations which could be tapped further to widen strategies toward systemic issues of inequity. The policy research and advocacy organizations offer analysis on the impact of systemic issues and possible solutions while the alternative and democratic schools prioritize equitable partnerships, student agency, foster holistic development beyond rote academics, and often experiment with flexible pedagogies and assessments to create more inclusive and responsive learning environments.

If these organization types could have some discursive impact and/or representation in better resourced educational partnerships, perhaps collaborative inquiry across a wider range of partners could help with addressing systemic issues. As discussed earlier in the paper, effective and sustainable educational partnerships depend not only on the exchanges of resources but also on a robust relational infrastructure that include a shared vision, power sharing, mutual trust and sustained leadership (Penuel and Gallagher, 2017).

Beyond formal institutions, informal education efforts led by local changemakers and residents supporting community-led approaches to learning, such as parent-led childcare or resident-led after-school care, offer significant promise. These models leverage local knowledge, resources, and social capital, ensuring support is culturally relevant, responsive to specific community needs, and builds collective ownership over children's wellbeing and development.

Conducting empirical research into educational partnerships to enhance the equity ecology

This paper represents the first stage of a broader programme that seeks to enhance the ecology of equity in Singapore by establishing a preliminary understanding of the role and perspectives of community-based organizations that are less discussed in educational partnerships literature. This understanding is valuable for future studies to gather direct evidence of the effectiveness as well as impact of such partnerships. With greater official emphasis and support on the partnerships involving community-based organizations, how such partnerships could be further leveraged to advance the equity ecology is crucial knowledge. This is especially important as schools in Singapore are still caught up in the academic meritocratic framework. Community-based organizations have a little more space to maneuver not being directly under the education ministry's purview. There is definitely a need for empirical research into the workings and outcomes of these organizations' partnerships on education to explore ways of circumventing the meritocratic framework to provide more holistic developments and empowerment of underprivileged children/youths.

Expanding the role of university researchers as cultural brokers of educational partnerships

As our analysis showed, current collaborations are often too carefully curated, focusing on remediative support rather than deeper co-creation. Not everyone has a seat at the table. Yet the ecology of equity needs an expansion of partnerships going beyond conventional configurations of schools, state agencies, and professional service providers, to include groups such as advocacy and alternative education groups mentioned above could better contribute toward addressing the “wicked problems” of educational inequity. However, organizations operating on the complementary model may be concerned about working with others who work outside of that model. There is thus a role for knowledge and cultural brokers (Penuel et al., 2015) other than the state to come in to facilitate such co-creative collaborations that could tap on each partner's distinct strengths. Possibly knowledge brokers who come from a more “neutral” background, such as university researchers, could facilitate various cross-sector and even within sector partnerships that could help bring in ideas on pedagogical approaches to more equitable partnerships as well as to contribute toward strategies on managing systemic issues (Hands, 2023; Teemant et al., 2021; Rubin, 2009). University researchers can act as an intermediary between the sectors, to broker partnerships that can effect systemic change. The educational equity network that the authors of this paper are a part of, or other similar platforms, could serve as crucial channels where different groups such as the five types of community-based organizations mentioned, school personnel, and university researchers could be brought together for collaborative inquiry, in the hope of forging new synergies and pathways to systems change. For a start, the organizers of the network could facilitate the sharing of data, the building of relational trust, shape norms and also conversations on power relations between schools, families and communities, all of which contribute toward effective sustainable partnerships (Henig et al., 2015; Penuel and Gallagher, 2017; Penuel, 2017). This network could also facilitate long-term partnerships between researchers and community-based organizations and even youths to adopt design-based implementation research and/or community-based participatory research to co-design equity-centered programs and initiatives (Penuel et al., 2020).

Unlocking emancipatory possibilities through inclusive, co-creative youth- led partnerships

To truly address the “wicked problems” of educational inequity, partnerships must move beyond tightly curated collaborations that merely support dominant paradigms. Instead, there is a need to foster inclusive and co-creative partnerships centring on youth agency and shared decision-making so that sustainable impact truly reaches those the support efforts target.

Often in youth programming, children and youths may be invited to participate but not shape the structures of goals of the programmes. In both SINDA and SHINE's discourse, well-meaning support appears to operate primarily on a “do for” rather than “do with” or “do by” approach. A truly collaborative governance model, especially when involving youth, needs to see the young not just as recipients or beneficiaries of adult-led programmes, but as active and legitimate stakeholders with important views and the ability to contribute meaningfully. As the disability sector advocates, it should be “nothing about us without us.”