- Department of Guidance and Values Education, College of Education, West Visayas State University, La Paz, Iloilo City, Philippines

Introduction: This study investigated the coping behaviors of 2,236 first-generation college students in the province of Iloilo, Philippines, focusing on how these learners manage academic, emotional, and socio-economic stressors through various strategies.

Methods: An embedded mixed-methods design was employed to gather both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative phase involved the administration of a coping behavior scale to 2,236 participants to determine patterns and variations in coping levels. The qualitative phase complemented this with in-depth interviews among nine purposively selected first-generation students, providing a richer understanding of their personal experiences and adaptive strategies. This combination allowed for the convergence of statistical findings with narrative insights.

Results: The quantitative results revealed a generally high level of coping among the respondents, with cognitive reappraisal (M = 3.01, SD = 0.61), spiritual support, and relaxation emerging as the most frequently utilized strategies. In contrast, social support and self-expression were only moderately practiced, indicating a tendency toward internalized coping mechanisms. High coping levels were consistent across sex, birth order, and income levels, though students from intact families reported greater use of social support, highlighting the influence of family structure. While there was no significant difference in the overall coping behaviors of the students, a significant relationship was observed among those from families experiencing disruption in relation to their birth order (ρ = −0.04, p = 0.19).

Discussion: The qualitative findings produced six major themes that deepened the quantitative results: (1) Weight of Familial Expectations and Financial Strain, (2) Coping Through Spiritual Anchoring, (3) Cognitive and Emotional Self-Regulation, (4) Selective Use of Social Support, (5) Birth Order and Coping Responsibility, and (6) Navigating Academic Overload and Emotional Fatigue. These themes illustrated the students’ adaptive behaviors rooted in cultural values, personal determination, and spiritual beliefs. Moreover, the findings revealed a multidimensional stress landscape among first-generation college students, underscoring their psychological resilience and strong reliance on spirituality, inner strength, and culturally embedded values. The integration of quantitative and qualitative data suggests that while these students experience multiple stressors, they exhibit adaptive and resourceful coping patterns. The study concludes by emphasizing the need for inclusive and context-sensitive psychosocial programs in higher education institutions that recognize and strengthen the coping resources of first-generation learners.

1 Introduction

In the Philippine context, empirical studies have emphasized the multifaceted challenges faced by first-generation college students (FGCS) as they transition into higher education. Research by Panganiban-Corales and Medina (2011) emphasized that Filipino students frequently rely on family and peer networks as primary coping resources, reflecting the collectivist orientation of Filipino culture. Liwag et al. (2022) further observed that students from intact family structures demonstrate stronger emotional resilience and more consistent use of social support mechanisms compared to those from families experiencing disruption. Meanwhile, Estanislao et al. (2020) highlighted the salience of spirituality and religiosity as culturally grounded coping strategies that enable FGCS to manage academic stress while maintaining a sense of purpose. More recently, Tuason et al. (2007) documented the role of communal resilience and adaptive behaviors in helping Filipino youth navigate systemic barriers such as poverty and limited institutional resources.

Recent empirical studies continue to emphasize the complexity of the transition to higher education for first-generation college students (FGCS), who face unique academic, social, and psychological challenges due to the absence of familial experience in navigating college systems. Musawar and Zulfiqar (2025) conducted a cross-sequential study in Pakistan revealing that FGCS enter university with lower academic readiness and less adaptive coping strategies compared to their continuing-generation peers, although these differences tend to diminish over the first few months of college. Complementing this, Adams et al. (2024) highlighted the significant mental health risks FGCS encounter, often stemming from cultural mismatches and “hidden curriculum” expectations. The hidden curriculum is mainly a way the teachers educate students on how to become good citizens and follow the norms of the society. Moreover, it is acknowledged as a socialization process of schooling. Hidden curriculum appears to be a way of transmitting the messages about values, attitude, and principles to the students (Abuzandah, 2021). These stressors are often exacerbated by feelings of family achievement guilt, as shown in Rivera et al.’s (2015) study, which demonstrated that reflecting on helping one’s family helped mitigate guilt and improved emotional regulation.

Family structure also remains a salient factor in shaping coping outcomes. Students from intact family systems often benefit from stronger emotional and logistical support, which enhances their ability to use adaptive coping strategies like social support and cognitive reappraisal (Smith et al., 2023). In contrast, students from family backgrounds experiencing disruption—such as single-parent or overseas-worker-led households—often exhibit a greater reliance on emotion-focused coping, including resignation or withdrawal, especially in the absence of structured mentorship or peer support. Glass (2023) found that mentorship programs such as iMentor significantly improved FGCS outcomes by building social capital and emotional resilience, underscoring the importance of institutional interventions.

In the context of this study, family structure is a critical dimension in understanding the developmental and coping processes of students, particularly first-generation college students (FGCS). An intact family structure refers to a household where both biological or adoptive parents are present and cohabiting, offering consistent emotional support, stability, and shared responsibilities in child-rearing. In contrast, a family structure experiencing disruption arises when this continuity is broken due to parental separation, divorce, death, or migration, often resulting in a single-parent or guardian-led household. Within Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979), the family is situated in the microsystem, the most immediate environment that directly influences an individual’s development and coping behaviors. Intact families typically provide stronger relational stability within this microsystem, fostering emotional security and accessible support networks, whereas families experiencing disruption may reduce consistency in guidance and coping resources. In the Philippine context, extended kinship and collectivist norms often serve as mesosystem supports that buffer the negative effects of disrupted structures.

In terms of coping, Ko et al. (2023) found that FGCS commonly face difficulties in developing independent learning habits and maintaining social networks, but those with stronger problem-solving skills and faculty engagement reported more successful adaptation. Spirituality, self-regulation, and reliance on institutional resources emerged as prominent coping strategies across various cultural contexts. For instance, Cheng et al. (2023) noted that Chinese FGCS frequently compensate for limited parental guidance by developing strong personal planning strategies and utilizing university support systems. Similarly, Ahmad et al. (2024) reported that Pakistani FGCS leaned on time management and peer collaboration, with gender playing a moderating role—female students showed higher academic readiness, while male students reported more externalized coping behaviors.

Together, these recent findings corroborate earlier frameworks by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Stebleton et al. (2014), which categorize coping into problem-focused and emotion-focused domains, influenced by individual and contextual factors. The literature consistently affirms that coping among FGCS is multi-layered, shaped by family dynamics, social expectations, institutional culture, and personal resilience. For higher education institutions, this implies the need for targeted, culturally responsive programs that address both the structural and emotional dimensions of the FGCS experience. Given the findings and gaps, this study explored on coping behaviors of FGCS in the Philippines, particularly in the province of Iloilo. By looking into these in the context of the Philippines, this study may shed light to how FGCS cope with demands through various strategies in terms of relaxation, social support, spiritual support, resignation, cognitive appraisal, problem-solving, self-expression, and diversion.

1.1 Research aim and focus

The primary aim of this study was to comprehensively determine the coping behaviors exhibited by college students at a rural state university in the Philippines, with a specific emphasis on how these behaviors might differ between students from intact family and family experiencing disruption. By employing an embedded mixed-methods approach, the research sought to provide both a broad quantitative assessment and an in-depth qualitative understanding of these vital adaptive strategies, with the following research questions:

1. What is the level of coping behaviors exhibited by college students at a rural state university in the Philippines when taken as a whole and classified according to family structure?

2. Is there a significant difference in the coping behaviors in terms of relaxation, social support, spiritual support, resignation, cognitive appraisal, problem-solving, self-expression, and diversion of college students from intact family and those with family experiencing disruption when grouped according to sex, birth order, estimated family monthly income?

3. Is there a significant relationship in the coping behaviors of college students from intact family and those from family experiencing disruption when grouped according to sex, birth order, estimated family monthly income?

4. What lived experiences and contextual factors explain the coping behaviors of first-generation college students in this setting?

More precisely, the study focused on ascertaining the overall level of various coping behaviors among the student population, including specific strategies such as cognitive reappraisal, relaxation, social support, spiritual support, resignation, problem-solving, self-expression, and diversion. The integration of qualitative inquiry further allowed for an exploration into the nuanced “how” and “why” behind these coping patterns, providing rich contextual data to complement the quantitative findings. These strategies are anchored in Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, which distinguishes between problem-focused and emotion-focused mechanisms, thereby offering a comprehensive framework for understanding how individuals adapt to stress. Moreover, these strategies capture both universal and culturally grounded forms of coping: cognitive reappraisal and problem-solving reflect adaptive, problem-focused approaches; relaxation and diversion represent stress-reduction techniques; while spiritual support and social support reflect collectivist, community-based, and faith-oriented practices that are particularly salient in the Filipino context (Estanislao et al., 2020; Tuason et al., 2007). Including Resignation and Self-Expression acknowledges less adaptive but realistic responses that students may employ when confronted with persistent stressors, such as financial strain or disrupted family support. By examining this spectrum of coping behaviors, the study provides a holistic understanding of how first-generation college students navigate academic, familial, and psychosocial challenges within their cultural and socio-economic contexts.

2 Methods

This overarching objective of this study was driven by the recognition that an individual’s formative family environment can significantly influence their development of coping mechanisms in response to life’s stressors, particularly during the demanding transition to higher education (Pamisa and Cabigas, 2025; Hukom and Madrigal, 2020). By strategically combining quantitative and qualitative approaches, the study ensured that each research question was addressed from both a statistical and experiential standpoint, thereby aligning the methodological choices with the dual aim of identifying patterns and uncovering the deeper “why” behind students’ coping behaviors. Having an embedded-mixed methods, the descriptive-correlational component directly addressed research questions concerning the prevalence of coping strategies and their relationship with demographic variables such as family structure and birth order, while the phenomenological inquiry provided answers to questions about the meaning and subjective impact of these coping processes.

2.1 Research design

The research design employed for this study was an embedded mixed-methods approach (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2017), providing a robust framework to thoroughly investigate the coping behaviors of college students. This design strategically combined both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The dominant component was a descriptive-correlational research design, which served to systematically characterize the student population and the prevalence of various coping behaviors. Descriptive research, as noted by McCombes (2023), accurately and systematically describes a population, situation, or phenomenon by answering “what,” “where,” “when,” and “how” questions. Furthermore, correlational research investigates relationships between variables without manipulation or control by the researcher, reflecting the strength and direction of those relationships (Bhandari, 2023; Salkind, 2010). This quantitative aspect allowed for the identification of patterns and relationships among variables—such as family structure and the reported levels of different coping strategies—providing a broad statistical overview. Complementing the quantitative data, a qualitative component grounded in descriptive phenomenology was carefully embedded to offer deeper, more nuanced insights into the students’ lived experiences and coping processes (Giorgi, 2009; Moustakas, 1994). This phenomenological dimension involved the collection of rich, first-person narrative data through semi-structured interviews, guided by key questions aimed at uncovering the essence of the phenomenon under study. The interview questions were intentionally crafted to elicit detailed, reflective responses about the specific challenges faced by first-generation college students (FGCS), their subjective coping mechanisms, the perceived impact of family setup and birth order on their coping abilities, and their sources of emotional and social support during times of distress. Consistent with Husserl’s (1970) principle of epoché or bracketing, the researcher consciously set aside personal biases and prior knowledge to fully attend to the participants’ descriptions, enabling the essence of their lived experiences to emerge authentically. As Creswell and Plano Clark (2017) emphasize, integrating qualitative methods in a mixed-methods framework enables researchers to understand complex phenomena more deeply by adding contextual meaning to quantitative trends. This approach provided the “why” behind the statistical findings, giving voice to students’ unique perspectives and grounding their coping behaviors within their social and personal realities.

The coping strategies explored in this study—relaxation, social support, spiritual support, resignation, cognitive appraisal, problem-solving, self-expression, and diversion in the context of the FGCS. First, relaxation is widely recognized as an effective stress management technique. Relaxation strategies such as deep breathing, mindfulness, and progressive muscle relaxation reduce physiological arousal and improve focus (Varvogli and Darviri, 2011). Moreover, social support serves as a critical buffer against stress. Cohen and Wills (1985) emphasized its protective role in promoting psychological wellbeing by reducing the perception of stress and enhancing coping capacity. Spiritual support has been shown to foster resilience and meaning-making during adversity. Pargament (1997) defined religious coping as the use of faith-based beliefs and practices to manage stress, offering a sense of purpose and hope. Resignation, while less adaptive, reflects a form of emotion-focused coping when stressors appear uncontrollable. Endler and Parker (1990) categorized resignation or avoidance as emotion-oriented coping, which may provide short-term relief but often hinders problem resolution. Meanwhile, cognitive appraisal lies at the core of stress and coping theory. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) described it as the process by which individuals evaluate stressors and determine available coping options. Students who engaged in positive reappraisal reframed challenges as manageable, which aligned with quantitative findings linking cognitive appraisal to higher resilience and qualitative accounts showing its role in reshaping educational perspectives. Added to this, problem-solving is a central form of problem-focused coping. Heppner and Petersen (1982) argued that effective problem-solving enhances adaptability and reduces stress by actively addressing stressors. Self-expression has been linked to emotional regulation and psychological wellbeing. Pennebaker (1997) highlighted expressive writing as a way to transform emotional experiences into structured narratives, promoting healing and clarity. Lastly, diversion strategies provide temporary relief by shifting attention away from stressors. Compas et al. (2001) noted that engaging in activities such as hobbies, recreation, or entertainment can reduce emotional distress, though their long-term adaptiveness depends on balance with active coping.

By weaving together statistical patterns and lived experiences, the study demonstrated that coping strategies are multidimensional, shaped by both personal contexts and broader social structures. The embedded mixed-methods approach allowed for a comprehensive understanding: the quantitative analysis offered clarity on “what” strategies students employed and “how often,” while the qualitative findings illuminated “why” these strategies mattered and “how” they were meaningfully integrated into students’ lives. This dual perspective underscores that coping behaviors are not only functional responses to stress but also deeply personal narratives of resilience, identity, and adaptation.

2.2 Participants

The study population comprised 7,754 students enrolled during the academic year 2023–2024 at state university in the province of Iloilo, Philippines. To obtain the research sample, a voluntary response sampling method was utilized over a two-week period in March 2024. A substantial number of students, specifically 2, 236, participated in the survey, resulting in a response rate of 28.84%. According to the Kantar Group (2023), a good survey response rate generally falls between 5% and 30%, with anything above 30% considered excellent, though the benchmark varies depending on the context and research design. Furthermore, a two-stage quota sampling technique was employed. This involved first establishing quotas for different subgroups within the student population (e.g., based on family structure) and then using convenience sampling to select participants from within each predefined quota. In this study, a predefined quota was applied to secure balanced representation of participants across key demographic variables central to the research. Eligible participants were first-generation college students, voluntarily participating in the study, and living with Filipino families residing in Iloilo, Philippines. Using a two-stage quota sampling technique, quotas were initially established for subgroups such as family structure, sex, birth order, and income classification. Within each subgroup, participants were then recruited through convenience sampling until the desired numbers were met. As Tuovila (2024) explains, sampling allows researchers to make inferences about large populations from smaller, manageable subsets, thereby ensuring both feasibility and relevance. This approach enabled the study to reflect the diversity of the student population while remaining aligned with its focus on coping behaviors and family structures.

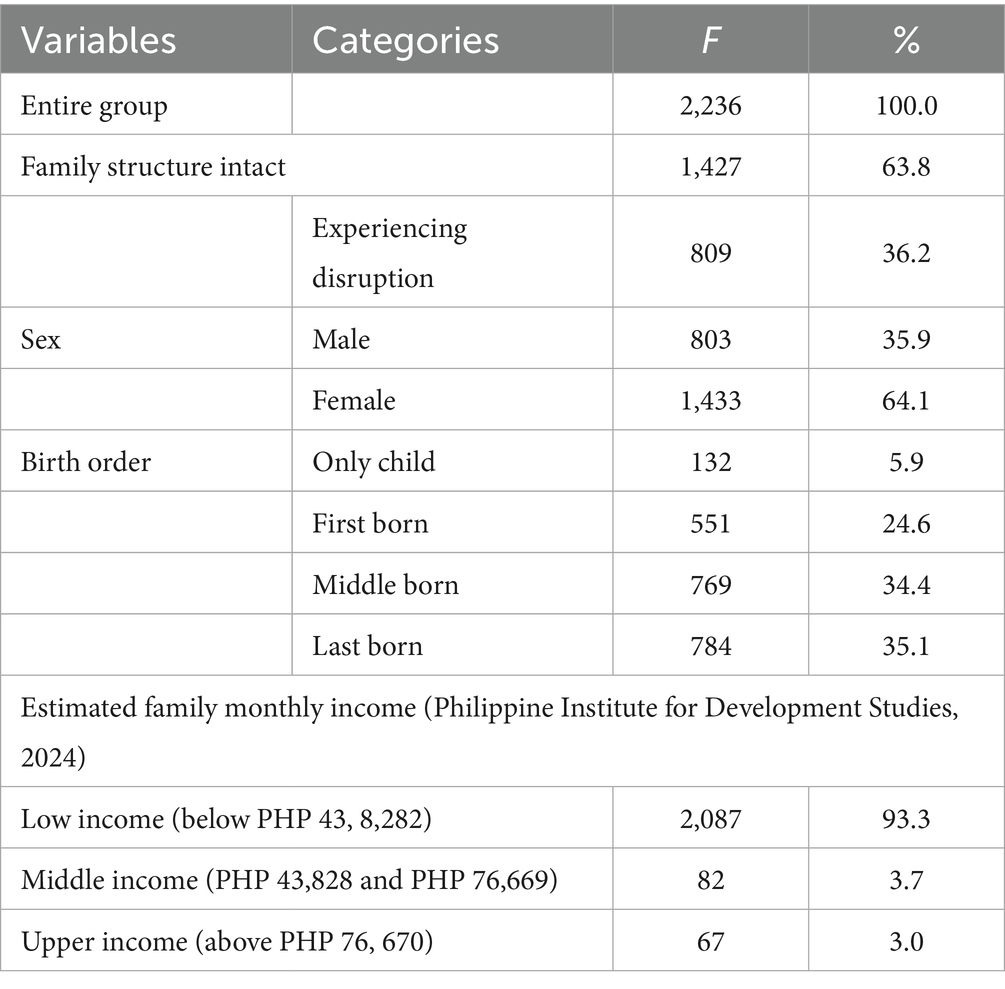

Based on Table 1, the research involved a total of 2, 236 participants, illustrating the demographics of the study. The majority of these participants, specifically 1,427 individuals (63.8%), reported belonging to intact family structures, while 809 individuals (36.2%) came from a family structure which experience disruption. In terms of sex, the group was predominantly female, comprising 1,433 participants (64.1%), with males making up the remaining 803 participants (35.9%). Regarding birth order, the largest proportion of participants were last-born (784 individuals or 35.1%), closely followed by middle-born (769 individuals or 34.4%). First-born participants accounted for 551 individuals (24.6%), and only children represented the smallest group with 132 individuals (5.9%). An analysis of their estimated family monthly income, based on the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (2024), revealed that an overwhelming 93.3% of the participants (2087 individuals) belonged to low-income families [below Philippine Peso (PHP) 43,282]. A smaller percentage, 3.7% (82 individuals), were from middle-income families (between PHP 43,282 and PHP 76,669), and the smallest group, 3.0% (67 individuals), were from upper-income families (above PHP 76,670).

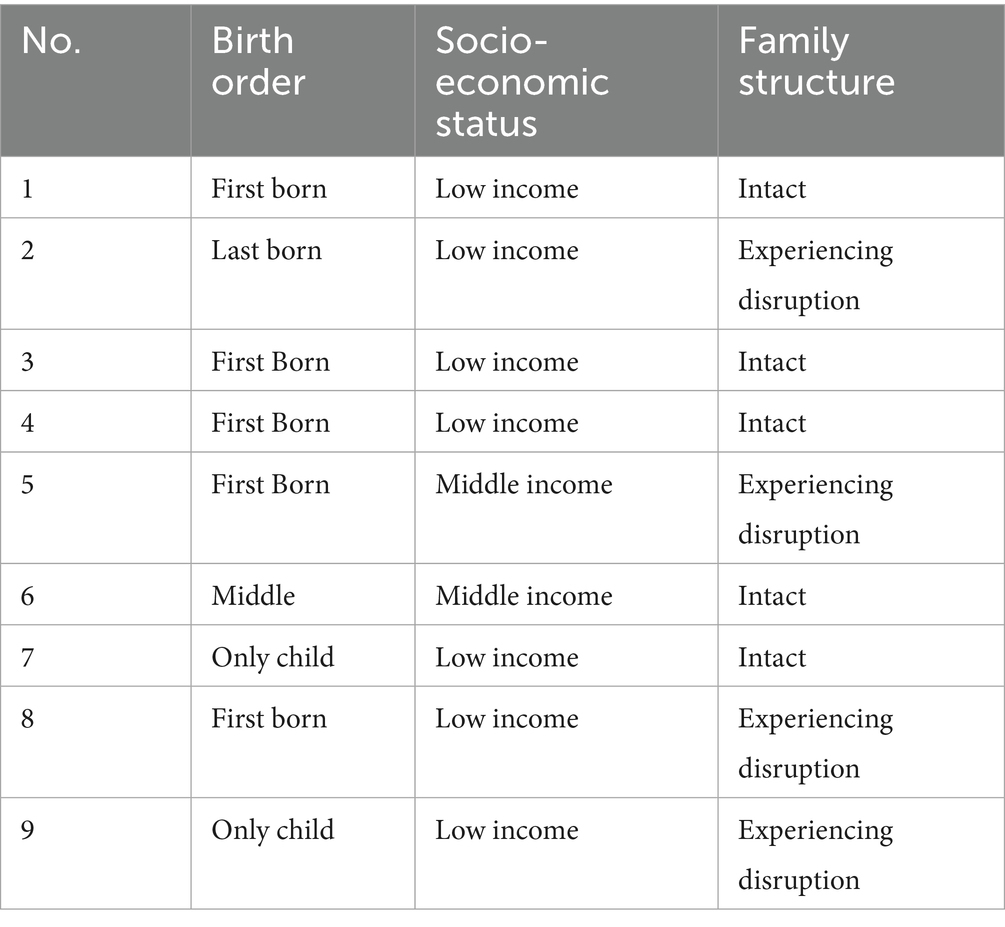

For the next phase, Table 2 illustrates the demographics of the participants who volunteered to be a part of the interview on first-generation college students.

2.3 Data collection procedures

This study employed an embedded mixed methods design; wherein qualitative data were integrated into a primarily quantitative framework to gain deeper insight into the coping behaviors of first-generation college students (FGCS). For the quantitative component, a coping behavior scale was administered to a large sample of students. The survey was distributed during the academic term, and participants were given clear instructions on how to complete the instrument. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was secured prior to administration. Completed questionnaires were collected, organized, and checked for completeness before being prepared for further processing.

To enhance and contextualize these numerical findings, a qualitative component grounded in descriptive phenomenology was embedded in the design (Moustakas, 1994; Giorgi, 2009). A subset of participants was purposively selected for semi-structured interviews that explored their lived experiences related to coping, including the influence of family dynamics, birth order, and sources of support. The interview protocol was designed to elicit deep, reflective responses aligned with the phenomenological aim of describing the essence of the phenomenon without imposing pre-existing theories (Husserl, 1970). Some questions posed during the interview include: What are some of the biggest challenges you have faced as a college student so far? (Establishes context for coping experiences); In what ways do you think your family background—like being the first in your family to go to college or your financial situation—affects how you deal with stress? (Connects demographic background with coping patterns); and Can you give examples of situations where you felt you handled stress well—or not so well? What did you do? (Elicits specific coping behaviors).

2.4 Data analysis

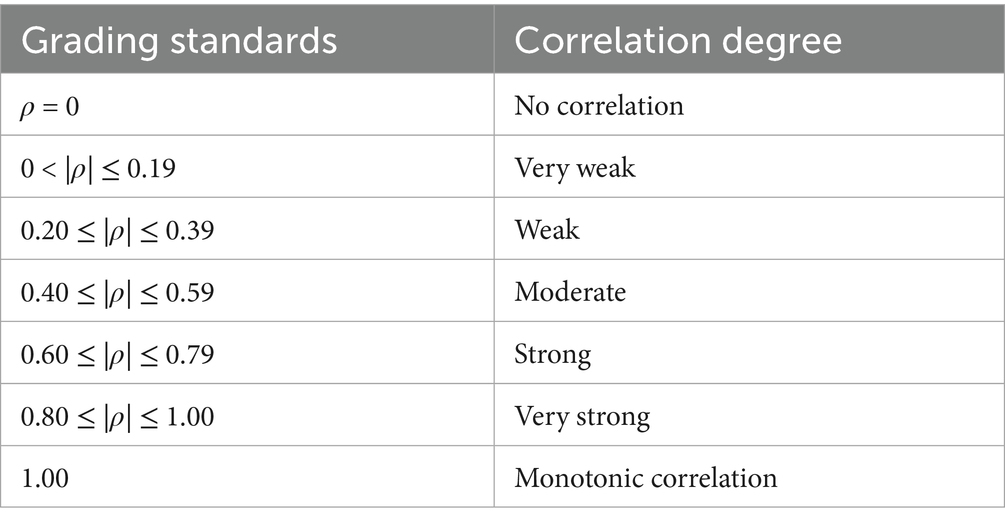

As an embedded mixed methods design, the quantitative component involved administering a researcher-made and validated coping behavior scale to a large sample of students. Descriptive statistics, specifically means (M) and standard deviations (SD), were computed to determine the average levels and variability of coping strategies employed. These numerical results were interpreted using a predefined scale, allowing for a clear classification of coping behaviors as “Very High,” “High,” “Moderate,” or “Low” (West et al., 2024). The data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U Test to determine significant differences in coping behaviors of first-generation college students when grouped according to sex, birth order, estimated family monthly income, and family structure, as well as Spearman’s rho to examine correlations between these demographic variables and coping strategies. Non-parametric tests were employed due to the ordinal nature and non-normal distribution of the data, with results interpreted at a 0.05 level of significance, with the following grading standards and degrees:

To complement and deepen these findings, a qualitative component grounded in descriptive phenomenology was embedded, following the methodological foundations of Moustakas (1994) and Colaizzi (1978). A purposive subset of participants was selected for semi-structured interviews aimed at eliciting rich, first-person narratives of their lived experiences related to coping with academic and personal stressors. For the qualitative component, participants were purposively selected based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and depth of the lived experiences captured. Students were included if they were first-generation college students currently enrolled at the rural state university in Iloilo, Philippines, belonged to either intact family or family experiencing disruption as defined in the study, and voluntarily agreed to participate by providing informed consent. Only those willing to engage in semi-structured interviews and reflect on their coping experiences were considered, as phenomenological inquiry relies on rich, first-person narratives to uncover the essence of a phenomenon (Moustakas, 1994). Conversely, students were excluded if they were not first-generation college students, were unwilling or unable to provide informed consent, declined or withdrew from interviews, or had incomplete demographic information, particularly regarding family structure classification. These criteria ensured that the participants selected could provide authentic, detailed accounts that align with the phenomenological aim of describing the meaning and structure of coping behaviors as they are experienced. Interview questions explored themes such as specific coping challenges, the perceived influence of family setup and birth order, and sources of support. Thematic analysis was employed to analyze the qualitative data, beginning with bracketing to set aside researcher biases (Giorgi, 2009), followed by coding of significant statements, clustering into broader categories, and synthesizing emergent themes.

The qualitative data were analyzed by the researcher using rigorous thematic analysis consistent with phenomenological procedures. This involved multiple stages: (1) horizontalization, or treating all statements as equally significant at the initial coding stage; (2) clustering of meaning units into significant categories; and (3) synthesizing these into central themes that conveyed the invariant structures of the coping experience (Moustakas, 1994). Bracketing was employed throughout to ensure that researcher biases and assumptions were consciously set aside, allowing the participants’ authentic voices to emerge (Giorgi, 2009).

This dual analytical approach ensured methodological triangulation and reinforced the study’s credibility by leveraging the statistical generalizability of quantitative data alongside the contextual richness of qualitative narratives. The integration of both forms of data provided a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the coping mechanisms among FGCS, highlighting not only how frequently certain behaviors are used, but also why and how students experience and enact them in real-life contexts.

This approach was consistent with recent studies exploring student stress and coping from a phenomenological perspective (Cortes et al., 2022; Morake and Xue, 2025). Themes such as self-reliance, familial responsibility, and peer support surfaced as critical components of FGCS coping experiences, reinforcing findings from recent research on first-generation students’ psychosocial adjustment (Azpeitia et al., 2023; Couoh, 2023). By combining quantitative measurement with qualitative interpretation, this study achieved both statistical generalizability and contextual richness, ensuring that the voices of FGCS were authentically represented and that the complexity of their coping mechanisms was fully understood.

2.5 Ethical considerations

This study strictly adhered to ethical standards to ensure the protection and dignity of participants. A letter of correspondence was addressed to the University. Then, the request was coursed through the office of student support services which helped in facilitating the conduct of the study for the college students. While there were no monetary benefits provided to the participants, a simple refreshment for the students to participate in this study were given by the researcher. Informed consent was obtained after explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature, with participants free to withdraw at any point without consequences. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained by coding responses and reporting results in aggregate form, while data were securely stored and will be disposed of in line with institutional policy. Potential risks, such as emotional discomfort when discussing coping or family background, were minimized by assuring participants of the option to skip questions and by providing referral information for counseling services. Cultural sensitivity was upheld by framing questions in a respectful manner, mindful of Filipino values such as hiya (shame) and religiosity.

3 Results

3.1 Level of coping behaviors among first-generation college students

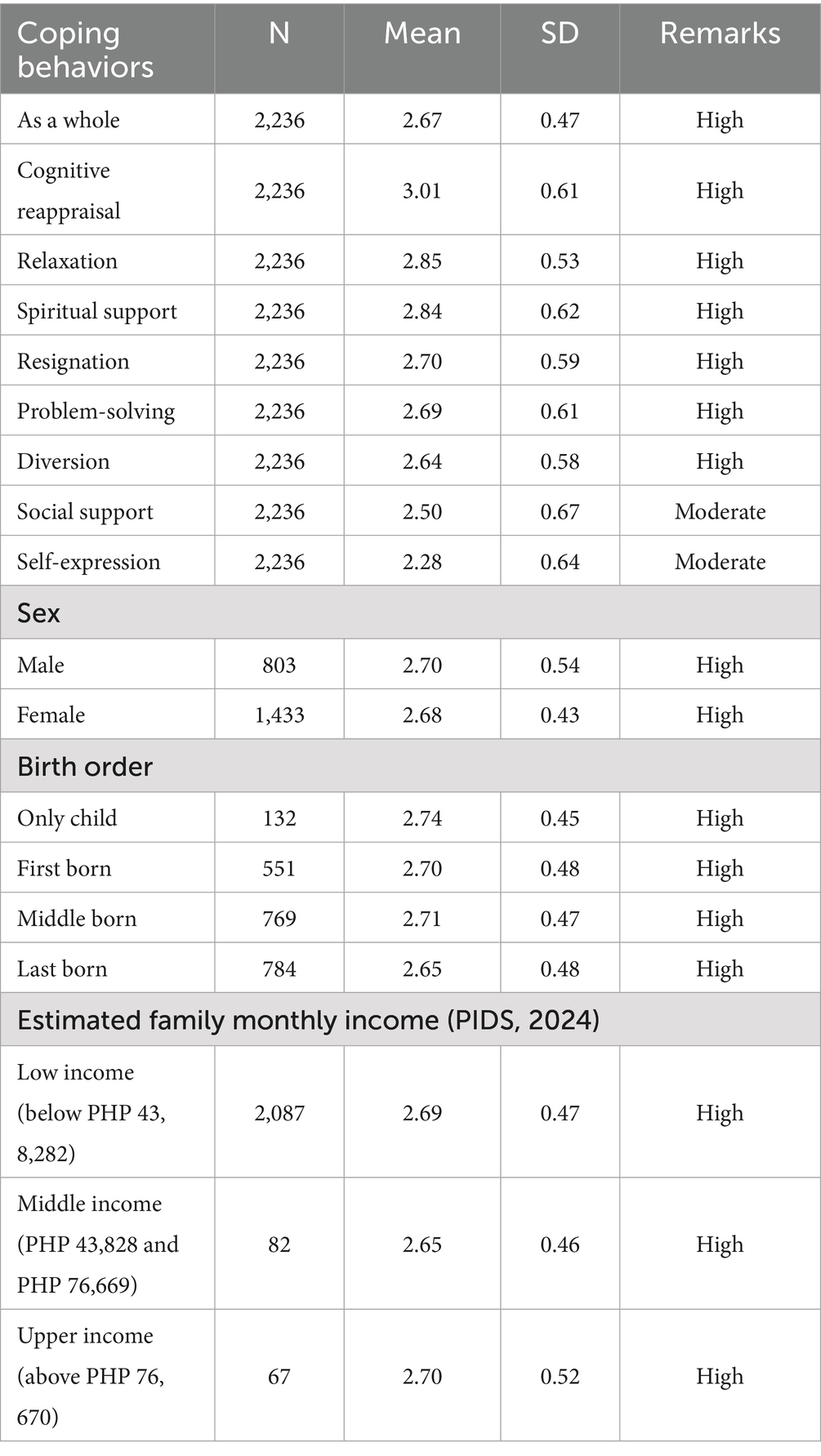

Table 3 provides an in-depth look into the coping behaviors of the 2,236 participants, examining how they utilize strategies such as relaxation, social support, spiritual support, resignation, cognitive reappraisal, problem-solving, self-expression, and diversion.

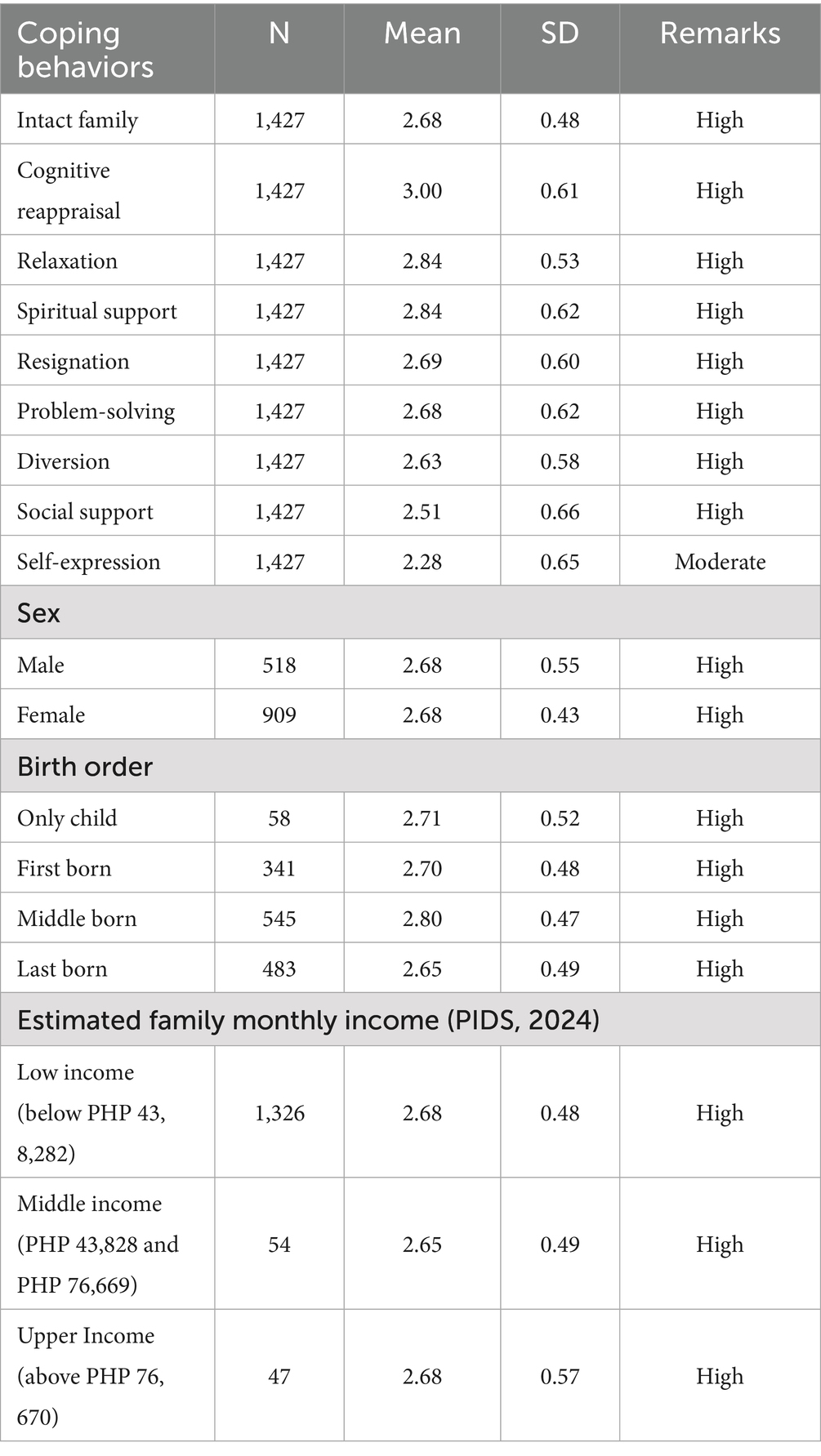

Overall, the participants exhibit a high level of coping, with Cognitive Reappraisal being the most frequently employed strategy, boasting the highest mean (M = 3.01, SD = 0.61). Spiritual Support and Relaxation also stand out as highly utilized coping mechanisms (M = 2.85, SD = 0.53) and (M = 2.84, SD = 0.62) respectively. Other coping behaviors like resignation, problem-solving, and diversion also registered high usage. Interestingly, social support and self-expression were noted as moderate coping behaviors, (M = 2.50, SD = 0.67) and (M = 2.28, SD = 0.64) respectively, indicating relatively less reliance on these compared to others. When analyzing by sex, both male (M = 2.70, SD = 0.54) and female (mean = 2.68, SD = 0.43) participants demonstrated high overall coping levels. Similarly, a consistent pattern of high coping was observed across all birth order categories: only children (M = 2.74, SD = 0.45), First born (M = 2.70, SD = 0.48), middle born (M = 2.71, SD = 0.47), and last born (M = 2.65, SD = 0.48). Furthermore, the data stratified by estimated family monthly income (PIDS, 2024) reveals that participants across all income brackets—low income (M = 2.69, SD = 0.47), middle income (M = 2.65, SD = 0.46), and upper income (M = 2.70, SD = 0.52)—consistently reported high levels of coping behaviors. This consistent “high” remark across various demographic divisions suggests a general resilience in coping strategies among the study’s participants.

3.2 Coping behaviors of first-generation college students in terms of family structures

3.2.1 Coping behaviors in an intact family structure

As indicated in Table 4, the study enrolled a substantial cohort of 2,236 participants, predominantly female (64.1%) and largely hailing from intact family structures (63.8%). A majority are from low-income families (93.3%), with only small proportions from middle (3.7%) and upper (3.0%) income brackets, indicating that the findings are most applicable to a lower socio-economic context in the Philippines. In terms of birth order, the distribution was fairly balanced across first-born (24.6%), middle-born (34.4%), and last-born (35.1%) individuals, with only children forming a minor segment (5.9%). Overall, the participants from an intact family demonstrated a high level of coping, with an average mean of 2.68. Delving into specific strategies, Cognitive reappraisal emerged as the most frequently utilized coping mechanism, followed closely by relaxation and Spiritual Support which are considered “High” in Table 4. While Resignation, Problem-Solving, and Diversion also showed high utilization, Social Support and Self-Expression were comparatively less employed by the entire group, being rated as “Moderate.”

A more granular analysis revealed remarkable consistency in overall coping levels across various demographic categories. Both male and female participants reported similarly high coping scores, as did individuals from all birth order categories (only, first, middle, and last born). Furthermore, the high overall coping was sustained across all income brackets—low, middle, and upper—suggesting that the general capacity for coping was not significantly differentiated by these demographic factors within this sample. However, a crucial distinction emerged when examining coping behaviors specifically within the intact family subgroup. While the overall coping level for this group remained high, aligning with the general trend, a notable shift occurred in the perceived effectiveness of Social Support. For participants from intact families, Social Support was rated as “High” (M = 2.51), in contrast to its “Moderate” rating when considering the entire study population. This finding strongly suggests that an intact family structure plays a pivotal role in enhancing individuals’ access to or perception of robust social support as a coping resource. The other coping strategies for the intact family subgroup largely mirrored the hierarchy observed in the overall group, with Cognitive Reappraisal, Relaxation, and Spiritual Support remaining paramount. This comprehensive analysis thus highlights both the widespread high coping abilities within the sample, predominantly driven by cognitive and spiritual strategies, and the specific reinforcing role of intact family structures in leveraging social support.

3.2.2 Coping behaviors in a family experiencing disruption

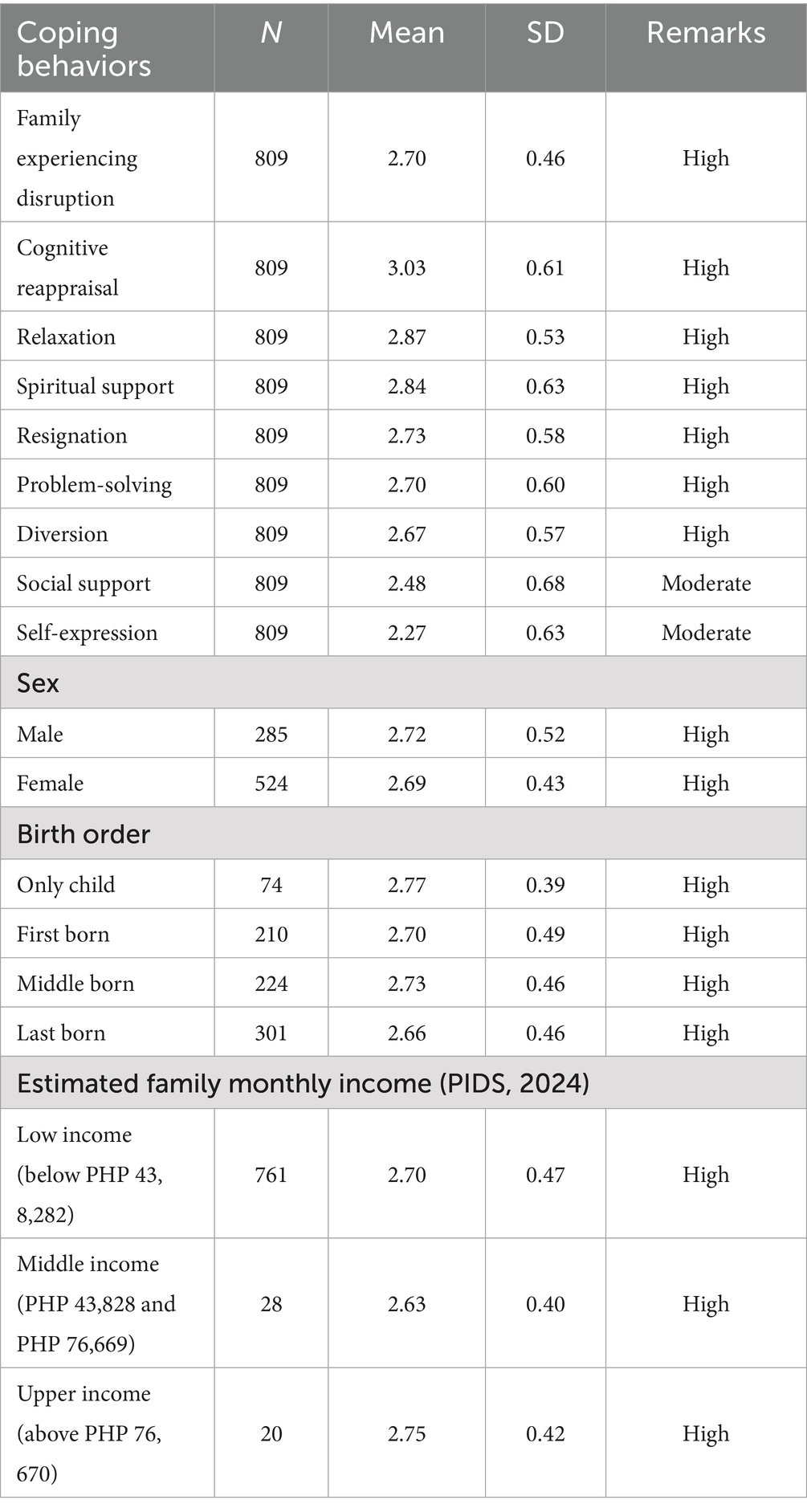

In Table 5, the study comprehensively examined 2,236 participants, with a notable demographic skew toward females (64.1%) and individuals from low-income families (93.3%), suggesting the findings are particularly reflective of this socio-economic stratum in the Philippines. While the majority of participants (63.8%) came from intact families, a substantial 36.2% were family backgrounds experiencing disruption. Across the entire cohort, a consistently high level of overall coping was observed (M = 2.67), with cognitive reappraisal, relaxation, and spiritual support standing out as the most frequently employed strategies. In contrast, social support and self-expression were utilized less, consistently falling into the “Moderate” range. This general pattern of high coping, and the specific hierarchy of coping strategies, held true across various demographic breakdowns, including sex, birth order, and estimated family monthly income, with no significant differences in overall coping levels across these categories.

A more detailed analysis comparing coping behaviors in participants from families experiencing disruption (N = 809) with the overall group further illuminated these trends. This family subgroup also reported a “High” level of overall coping (M = 2.70), remarkably similar to the overall study population. Their preferred coping strategies largely mirrored the entire group’s, with cognitive reappraisal, relaxation, and spiritual support being the most prominent. Crucially, for both the overall group and the family experiencing disruption subgroup, Social Support remained a “Moderate” coping strategy, suggesting that for individuals experiencing family disruption, or in the general population of this study, social support is not as primary a coping mechanism as cognitive reframing or spiritual practices. This contrasts with observations from intact family subgroups (as per previous analysis, not directly in these provided tables but a related finding), where social support was rated “High,” indicating a potential differentiating role of intact family structures in leveraging social support. Ultimately, the data consistently points to a robust coping capacity across this diverse Filipino sample, with a reliance on internal and spiritual resources, and less emphasis on social support, especially in the context of family structures experiencing disruption.

3.3 Comparative analysis of coping behaviors among first-generation college students

3.3.1 Significant difference of coping behaviors among first-generation college students according to sex, birth order, estimated family monthly income

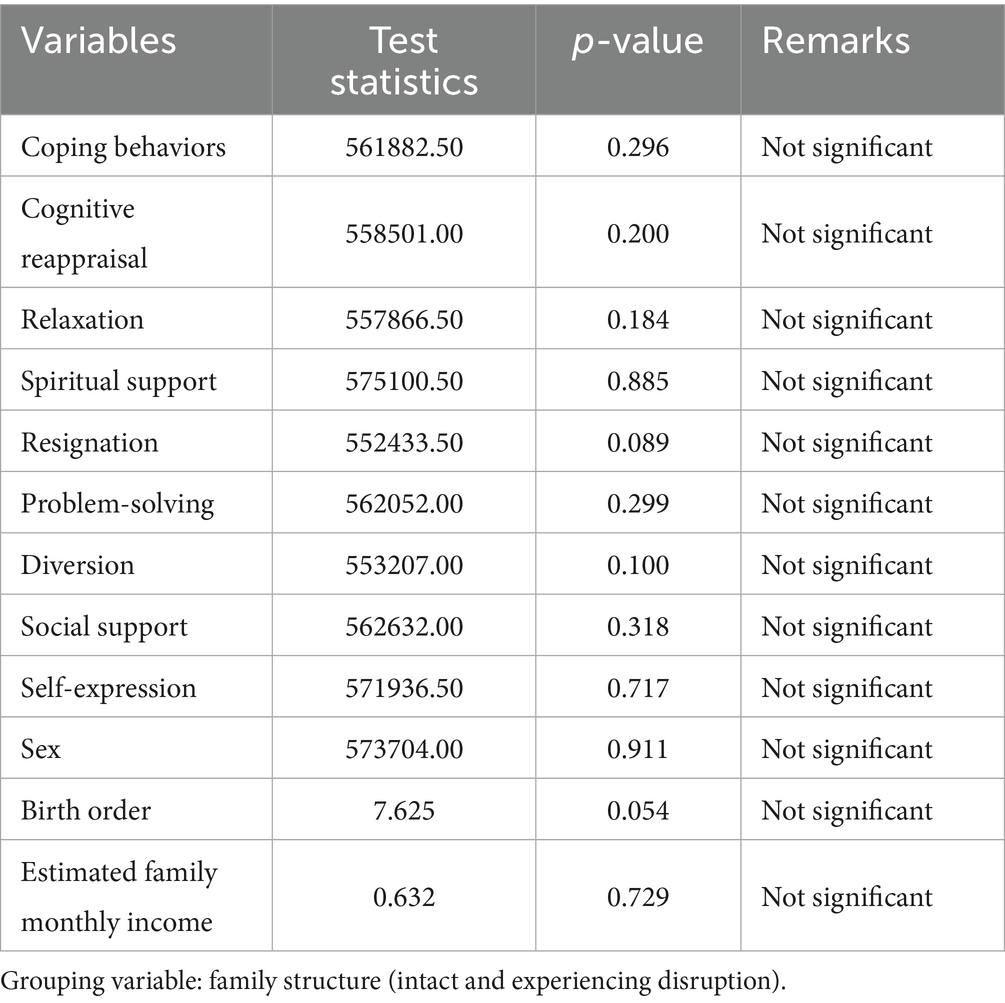

As shown in Table 6, the coping mechanisms of college students, whether from intact families or families experiencing disruption, did not significantly differ when compared by family structure (U = 561,882.50, p = 0.30). Similarly, no significant differences were observed across specific coping strategies, including cognitive reappraisal (U = 558,501.00, p = 0.20), relaxation (U = 557,866.50, p = 0.18), spiritual support (U = 575,100.50, p = 0.89), resignation (U = 552,433.50, p = 0.09), problem-solving (U = 562,052.00, p = 0.30), diversion (U = 553,207.00, p = 0.10), social support (U = 562,632.00, p = 0.32), and self-expression (U = 19,571,936.50, p = 0.72). Furthermore, coping behaviors showed no significant differences when students were grouped according to sex (U = 573,704.00, p = 0.91), birth order (U = 7.625, p = 0.054), or estimated family monthly income (U = 0.632, p = 0.729).

Table 6. Significant difference in the coping behaviors of FGCS from intact family and family experiencing disruption.

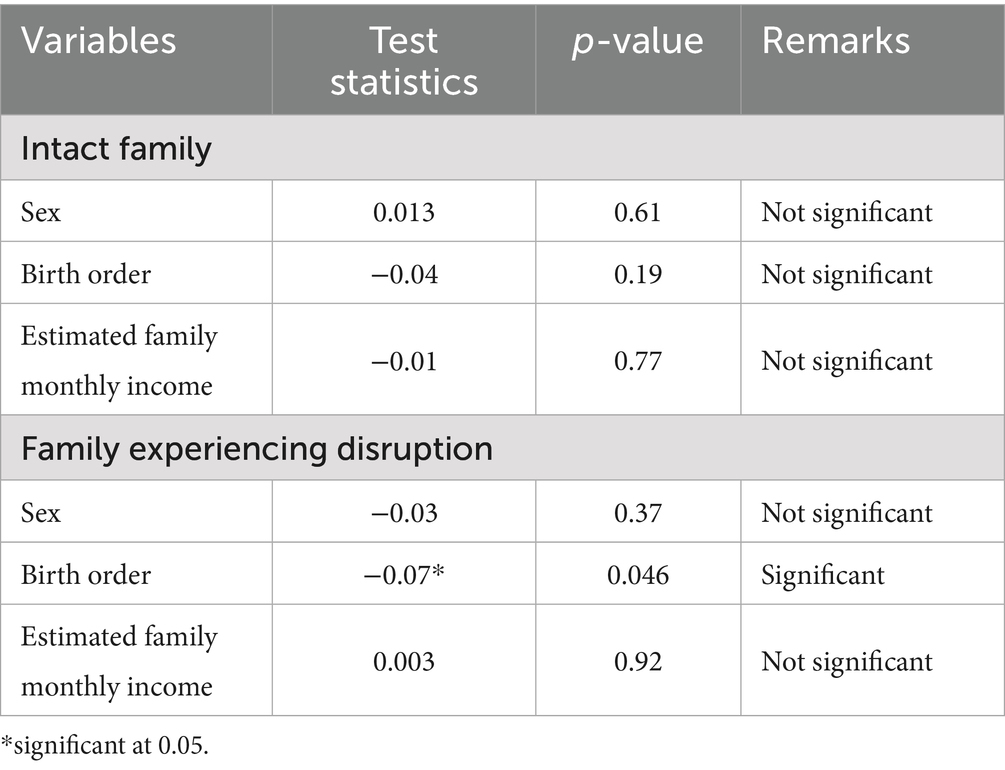

3.3.2 Significant relationship of coping behaviors among first-generation college students according to sex, birth order, estimated family monthly income

Given in Table 7, the coping behaviors of college students from intact families showed no significant relationship when grouped according to sex (ρ = 0.013, p = 0.61), birth order (ρ = −0.04, p = 0.19), and estimated family monthly income (ρ = −0.01, p = 0.77). For students from families experiencing disruption, coping behaviors revealed a significant negative correlation when grouped according to birth order (ρ = −0.01, p = 0.76). However, no significant correlation was found when grouped according to sex (ρ = −0.03, p = 0.37) and estimated family monthly income (ρ = 0.003, p = 0.92).

Table 7. Correlation of coping behaviors of FGCS from intact family and family experiencing disruption.

3.4 Lived experiences of coping behaviors among first-generation college students

3.4.1 The weight of familial responsibility and financial precarity

This theme encapsulates the significant pressure first-generation students feel to succeed, often driven by their families’ hopes and the stark reality of financial limitations. Their academic journey is deeply intertwined with their family’s wellbeing and future prospects, leading to unique forms of stress and motivation.

Financial Strain as a Primary Obstacle. Participant 1, who is a first-born and comes from an intact family, explicitly states, “As a first-generation college student, one of the challenges I encountered is financial problem. It is hard to focus on my studies.” The sentiment is echoed by Participant 5, an eldest child and from a family experiencing disruption, “Para sa akon ang commonly faced namon is financial problem and the pressure.” [For me, we commonly face financial problem and pressure.]

The Burden of Being the “Family’s Hope.” Participant 3, a working student and eldest from an intact family, articulates the immense pressure of being the family’s hope: “As a first-generation college student who is a working student, I try my best to improve, given nga maging hamon kay ako palang ang hope sa aming pamilya namon.” [I will be the first and only hope of my family.]

Sacrificing Personal Wellbeing for Family. The connection between financial status, basic needs, and academic performance is also evident. Participant 6, a middle child from an intact family, mentioned, “Many students facing or going hungry can affect how they perform in their studies. If students are hungry or thirsty, they cannot think critically.”

3.4.2 Multifaceted academic and emotional overload

This theme highlights the combined burden of academic demands (high scores, workload management) and intense emotional stressors (overthinking, self-isolation, pressure from parents). Students face not only the challenges inherent in college but also the added psychological strain of their first-generation status.

Social Support. This is a consistently highly ranked coping mechanism, with multiple students indicating it as their choice or the most frequently used coping behavior. As a last-born child from a low-income family experiencing disruption, Participant 2 mentioned “Going to my friends or any one people to help me comfort.” This was supported by those first-generation students from low-income intact families such as Participant 3 who said “I usually talk to my friends and my family if I feel stress” and Participant 7 who added “Reach out to my family and friends comfort me and give me strength and advice to my problem.”

Spiritual Support. This mechanism appears frequently among the choices, signifying its pervasive use. Participant 8 who comes from a low-income family experiencing disruption states, “I always pray to God that makes me happy whenever I feel unsafe and when I have a problem” and Participant 4 from a low-income intact family highlights, “I always turn to God because, with all of my problems, I feel like I am offering them to God and I can do everything by trusting Him.”

Relaxation/Self-Care (including physical activity). This category encompasses various methods aimed at calming oneself and is present across all top ranks. From intact family structure, Participant 1 said “When I feel stressed, I make myself calm or relax” and Participant 4 mentioned “I go to the room and sleeping then after sleeping I do breathing exercises and pray.” This was also affirmed by one of the participants from family structure experiencing disruption such as from Participant 2 who elaborated “I dance,” and “exercising and exerting myself on a physical activity.”

3.4.3 Birth order as a determinant of responsibility and pressure

The Eldest Child as the Family’s Hope and Provider. Participant 3, eldest child from an intact family explicitly states the profound responsibility they feel: “Yes, as the eldest one in the family all my siblings always depend on me, they always say that as the eldest, I have the full responsibility and try to support my family especially your younger brothers.” Participant 5, another eldest child from a family experiencing disruption reinforces this, expressing the pressure to “graduate in college, because I think I need to maghanap nang magandang trabaho and malaking sweldo.” [find a decent job and earn a big amount of salary.]

The Middle Child’s Adaptability Amidst Pressure. Participant 6, a middle child’s experience from an intact family, points to a different kind of pressure and a need for adaptability, said: “As a middle child, grabe gid and pressure sa akon nga kada adlaw para may ipa-allowance lang sakon.” [As a middle child, I have experienced an extreme pressure because I have to have my allowance everyday.]

The Only Child’s Unique Challenge of Isolation and Direct Parental Expectation. While seemingly less burdened by sibling responsibilities, Participant 9, the “only child” narrative reveals a unique challenge who said: “Being an only child with the presence of my parent is quite a delimma. Because dealing with pressure and responsibility might really overwhelm me and I cannot completely face everything. Having no one to confide your experiences with as well because even introverts like me need basic human interaction too.” Participant 8, another only child who is also a first born in a family experiencing disruption states, “As an only child the pressure for me is not much, but dapat mag-focus pageskwela kag matapos gid ko sa pageskwela.” [I need to focus and finish my studies on time.]

3.4.4 Navigating high stakes: the interplay of familial expectation, financial constraint, and academic pressure

The Direct Impact of Financial Strain on Academic Focus. Many students highlight how their family’s financial struggles directly impede their ability to concentrate on their studies. Participant 8 explicitly states, “As a first-generation college student, one of the challenges I encountered is financial problem because it’s hard to best to focus on my studies.” This is further underscored by the Participant 3’s observation from a low-income family that “Many students are going to school hungry. They cannot focus. It is very important that they need to fill their stomachs to think critically.”

The Overwhelming Pressure of Being the “Family’s Hope.” First-generation students often carry the immense weight of their family’s aspirations. Participant 4 , a working student from a low-income family, articulates this emotional burden powerfully: “I need to strive harder and manage my time purposively.”

The Combined Stress of Academic Demands and External Pressures. The challenges extend beyond just finances to include intense academic demands and other external pressures. Participant 1 from an intact family describes facing “academic and personal input especially when I am balancing my daily outputs and the pressure to finish them all.” Participant 5 from a family experiencing disruption lists a multitude of stressors including “stress, self-isolation, pressure of dealing with parents, exaggerated imaginations, financial, no enough food, lack of socialization and finally is being alone.”

4 Discussion

The findings presented in Sections 3.1 and 3.2 of the study offer compelling empirical evidence of the high coping capacity among first-generation college students in the Philippines, regardless of sex, birth order, or socio-economic background. These results are consistent with a growing body of literature emphasizing resilience among marginalized student populations (Stebleton et al., 2014; Ramos and Kaslow, 2021). The overall high coping levels, particularly the dominant use of Cognitive Reappraisal (M = 3.01), are consistent with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) Transactional Model of Stress and Coping, which categorizes this strategy as an adaptive, problem-focused mechanism. First-generation students, who often face systemic and socio-cultural stressors (Jehangir, 2010), appear to benefit from reframing stressful situations cognitively—thus protecting academic motivation and psychological wellbeing. These findings highlight the need for higher education institutions to institutionalize resilience-building programs and integrate coping strategy training into student development frameworks. At the level of practical application, faculty and student support offices may design workshops, counseling sessions, and peer mentorship initiatives that cultivate adaptive strategies like cognitive reappraisal, while also addressing barriers that exacerbate stress among first-generation college students. It is essential to note that students should not endure these barriers and the ultimate goal is to remove these systemic barriers for them to achieve better academic outcomes.

Additionally, high engagement in Spiritual Support (M = 2.85) and Relaxation (M = 2.84) reflects culturally grounded coping patterns in collectivist societies like the Philippines. Studies by Estanislao et al. (2020) and Tuason et al. (2007) highlight the centrality of religiosity and meditative practices as vital Filipino coping anchors, especially when external support structures are limited. Interestingly, Social Support (M = 2.50) and Self-Expression (M = 2.28) were only moderately used, which aligns with existing research suggesting that Filipino students, particularly those from lower-income and family experiencing disruption backgrounds, may underutilize peer and institutional networks due to perceived stigma or self-reliance norms (David et al., 2019; Gonzales et al., 2022). These findings may also reflect cultural norms of hiya (shame) and emotional restraint, which could suppress outward self-expression or help-seeking behaviors.

From a policy standpoint, these insights give importance to developing student support services that are culturally responsive—integrating faith-based, mindfulness, and relaxation activities into wellness programs, while also addressing cultural barriers to help-seeking. In terms of practice, universities may foster safe spaces and peer-support initiatives that normalize self-expression, reduce stigma, and encourage students to engage in institutional networks without fear of judgment.

A significant pattern emerged when comparing participants from intact family versus family experiencing disruption. Students from intact families rated Social Support as a “High” coping behavior (M = 2.51), unlike those from families experiencing disruption, where it remained “Moderate.” This corroborates Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (1979), which underscores the foundational role of the family microsystem in shaping psychological resilience and support-seeking behavior. Similarly, research by Liwag et al. (2022) notes that students with stable family units often access more consistent emotional and instrumental support, thus increasing their reliance on social networks during academic stress. Despite traditional assumptions, coping behaviors did not significantly vary across sex, birth order, or income levels, suggesting a homogeneous resilience profile among these first-generation students. This uniformity, especially within a predominantly low-income cohort (93.3%), underscores a communal resilience and cultural adaptation among Filipino youth in navigating educational barriers—a finding supported by previous national studies (e.g., Panganiban-Corales and Medina, 2011). According Blackwell and Pinder (2014), first-generation college students were not encouraged by family to attend college but their inner drive to attend college to achieve a better way of life for themselves led to them being the first in their families to attend and to graduate from college. From a policy perspective, these findings call for higher education institutions to design inclusive support systems that extend beyond family structures, particularly to students from disrupted households who may lack consistent emotional or instrumental backing. In terms of practice, universities can strengthen mentorship programs, guidance counseling, and peer-led initiatives to replicate the protective role of intact family systems, thereby leveling the support landscape for all students.

The findings suggest that the coping behaviors of first-generation college students are generally consistent regardless of family structure, sex, birth order, or estimated family monthly income, indicating that demographic variables exert minimal influence on how students manage stress. This implies that higher education institutions should prioritize inclusive and equitable support systems—such as universal coping-skills training, resilience-building workshops, peer mentorship programs, and accessible counseling services—rather than tailoring interventions narrowly to specific subgroups. At the policy level, institutionalizing comprehensive guidance and mental health programs would ensure that all first-generation students, regardless of background, benefit from structured coping resources. In practice, a holistic approach that integrates academic, emotional, social, and spiritual wellbeing is recommended to strengthen adaptive coping across diverse student populations, while also giving attention to sibling dynamics in families experiencing disruption where a weak negative correlation by birth order was noted.

In terms of the comparative analysis, the findings suggest that the coping behaviors of first-generation college students are generally consistent regardless of family structure, sex, birth order, or estimated family monthly income, indicating that demographic variables exert minimal influence on how students manage stress. This aligns with recent studies showing that first-generation students’ coping strategies are shaped more by individual resilience and institutional contexts than by background characteristics (Chang et al., 2020; Helmbrecht and Ayars, 2021). It further implies that higher education institutions should prioritize inclusive and equitable support systems—such as universal coping-skills training, resilience-building workshops, peer mentorship programs, and accessible counseling services—rather than tailoring interventions narrowly to specific subgroups. At the policy level, institutionalizing comprehensive guidance and mental health programs is vital, as evidence shows that structured support systems significantly improve wellbeing and academic persistence among first-generation students (LeBouef and Sieving, 2025; Ramos, 2022). In practice, a holistic approach that integrates academic, emotional, social, and spiritual wellbeing is recommended to strengthen adaptive coping across diverse student populations (Huerta and Fishman, 2024; Wang et al., 2022).

The qualitative narratives in Section 3.4 provide a rich, nuanced understanding of the internal and external pressures faced by first-generation college students, complementing the earlier quantitative findings. These lived experiences validate and contextualize the reported high levels of coping, revealing how students manage emotional, financial, and academic stress through culturally and personally resonant strategies. Four core themes emerge from this analysis: the weight of familial responsibility and financial precarity, multifaceted academic and emotional overload, birth order as a determinant of responsibility and pressure, and navigating high stakes: the interplay of familial expectation, financial constraint, and academic pressure.

The experiences shared by students underscore how economic disadvantage and familial hope are interlinked forces that shape the coping landscape of first-generation learners. Consistent with empirical studies (e.g., Covarrubias et al., 2019; Engle and Tinto, 2008), financial strain emerges as the most consistent stressor, inhibiting academic concentration and performance. The succeeding theme aligns closely with literature describing first-generation students’ “double load”—balancing academic performance while managing unique emotional and psychological stress (Stephens et al., 2012). The coping strategies highlighted here support the quantitative data and show strong reliance on internalized and spiritual coping, including prayer, relaxation, and peer interaction. Birth order emerges as a socio-cultural determinant of coping stress and expectation, a concept supported by existing Filipino psychosocial research (Liwag, 2022; Yacat, 2005). Eldest children consistently report heightened responsibility and the expectation to serve as economic contributors.

This integrative theme reflects the intersectionality of stressors that compound in the lives of first-generation students: low-income background, family expectation, and academic rigor. The pressure to achieve academically while being financially insecure is not just a logistical challenge but an emotional and existential weight. As Participant 5 outlines, the constellation of stressors—financial instability, social isolation, and parental expectations—forms a complex web of chronic stress that necessitates multi-layered coping. These findings resonate with research by Wilbur and Roscigno (2016), which outlines how class-based inequalities, combined with institutional academic pressures, create psychosocial dilemmas for first-generation students, often leading to emotional burnout or disengagement if unaddressed. The results of the study highlight the innate resilience of FGCS which implies a strategic plan from higher education institutions in the Philippines to focus on the need for a targeted, culturally-responsive programs to address structural and emotional dimensions of these college students.

5 Conclusion

This study provides strong quantitative and qualitative evidence of the resilience and coping capacity of first-generation college students (FGCS) in the Philippines. Across demographic variables—sex, birth order, and socioeconomic background—students demonstrated consistently high levels of adaptive coping, with cognitive reappraisal emerging as the most dominant strategy. This aligns with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) model of stress and coping, emphasizing the role of reframing in maintaining psychological wellbeing and academic motivation despite systemic and socio-cultural stressors. Complementary qualitative insights reveal that coping among FGCS is not only an individual process but also deeply rooted in cultural and familial contexts, highlighting the significance of spirituality, relaxation, and familial expectations as mediating factors. The distinction between students from intact family and family experiencing disruption further underscores Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) assertion of the family’s central role in resilience, while the uniformity of coping across a predominantly low-income population signals a shared cultural adaptation and communal resilience among Filipino youth. These findings have clear implications for higher education policy and practice. Additionally, while demographic predictors showed little influence, attention to sibling dynamics in families experiencing disruption may be warranted, given the weak negative correlation by birth order observed in this study. Institutions may institutionalize resilience-building initiatives, develop culturally responsive student support services, and design inclusive programs that bridge gaps for students from family structures experiencing disruption. Practical interventions, such as workshops, counseling, faith-based programs, and mentorship opportunities, can strengthen both internal and external coping resources while dismantling stigma around help-seeking.

5.1 Limitations and future directions

Future research may expand on these findings by conducting longitudinal, path analysis or multiple regression, and comparative studies to track the sustainability of coping strategies, assess their impact on persistence and academic success, and further explore the interplay of cultural constructs such as hiya and collectivism in shaping help-seeking behaviors among FGCS. This study reaffirms the strength of FGCS in navigating adversity and highlights the responsibility of higher education institutions to create equitable, supportive, and culturally attuned environments that foster both academic achievement and psychological wellbeing.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because this study only focused on the lived experience of the participants. It did not involve any interventions. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AT-S: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the participation of the first-generation students who voluntarily shared their lived experiences. The author extends her heartfelt gratitude to the College of Education, West Visayas State University, Philippines.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abuzandah, S. (2021). The hidden curriculum. Afr. J. Educ. Manag. Teach. Entrep. Stud. 2, 22–25. doi: 10.5897/AJEMATES2021.0021

Adams, R. M., Thompson, L. J., and Reyes, C. M. (2024). Mental health challenges and cultural mismatch among first-generation college students: the hidden curriculum of higher education. J. Adolesc. Health 74, 215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.11.001

Ahmad, S., Javed, F., and Khan, A. (2024). Gender differences in academic preparedness and coping strategies among first-generation university students in Pakistan. J. Educ. Psychol. Practice 14, 44–59.

Azpeitia, J., Lazaro, Y. M., Ruvalcaba, S. A., and Bacio, G. A. (2023). “It’s easy to feel alone, but when you have community…”: first-generation students’ academic and psychosocial adjustment over the first year of college. J. Adolesc. Res. doi: 10.1177/07435584231169095

Bhandari, P. (2023). Correlational research: definition, types and examples. Scribbr. Available online at: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/correlational-research/ (Accessed March 15, 2025).

Blackwell, E., and Pinder, P. J. (2014). What are the motivational factors of first-generation minority college students who overcome their family histories to pursue higher education? Coll. Stud. J. 48, 45–56.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Available at: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674224575

Chang, J., Wang, S.-W., Mancini, C., McGrath-Mahrer, B., and Orama de Jesus, S. (2020). The complexity of cultural mismatch in higher education: norms affecting first-generation college students’ coping and help-seeking behaviors. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 26, 280–294. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000311

Cheng, L., Wang, Y., and Li, J. (2023). Coping strategies and institutional support: a study on first-generation college students in China. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 97:102717. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2023.102717

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Colaizzi, P. F. (1978). “Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it” in Existential-phenomenological alternatives for psychology. eds. R. S. Valle and M. King (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 48–71.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., and Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol. Bull. 127, 87–127. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87

Cortes, V. M., Perez, L. E., McCarthy, J. O., Rumol, B. J., and Tulod, F. K. (2022). The coping mechanisms of first-year students in online classes: a descriptive phenomenological study. Int. J. Humanit. Educ. Dev. 4, 116–125. doi: 10.22161/ijhed.4.3.15

Couoh, D. A. (2023). Coping strategies among Latina first-generation college students experiencing depression, anxiety, and imposter syndrome: A scoping review [master’s thesis, California State University, Northridge]. Northridge, CA: CSUN ScholarWorks.

Covarrubias, R., Valle, I., and Stone, J. (2019). Critical race theory meets cultural capital: community cultural wealth and the chican@ educational pipeline. Race Ethn. Educ. 22, 496–515. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2019.1573328

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

David, C. C., Alburo, R. A., and Uy-Tioco, C. B. (2019). Mental health and help-seeking behavior among Filipino college students. Philip. J. Psychol. 52, 19–41.

Endler, N. S., and Parker, J. D. A. (1990). Coping inventory for stressful situations (CISS): manual. Toronto, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

Engle, J., and Tinto, V. (2008). Moving beyond access: college success for low-income, first-generation students : Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education.

Estanislao, S., Tolentino, R. B., and Reyes, A. (2020). Religion and coping among Filipino college students. Liw: University of the Philippines Press.

Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: a modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Glass, R. D. (2023). Mentorship and social capital: supporting first-generation students through structured interventions. Urban Rev. 55, 493–512. doi: 10.1007/s11256-022-00645-z

Gonzales, J., Gozum, I., and Llego, M. (2022). Barriers to counseling and psychological help among Philippine students. Asia-Pacific Educ. Rev. 23, 73–85. doi: 10.1007/s12564-022-09747-5

Helmbrecht, B., and Ayars, C. (2021). Predictors of stress in first-generation college students. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 58, 214–226. doi: 10.1080/19496591.2020.1853552

Heppner, P. P., and Petersen, C. H. (1982). The development and implications of a personal problem-solving inventory. J. Couns. Psychol. 29, 66–75. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.29.1.66

Huerta, E., and Fishman, R. (2024). The struggle of first-generation college students and mental health [Report]. Long Beach, CA: California State University Scholars. Available at: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/1257b157q

Hukom, E. C., and Madrigal, D. V. (2020). Family environment and resilience among Filipino adolescents: basis for a proposed psycho-educational program. Philip. Soc. Sci. J. 3, 44–52. doi: 10.52006/main.v3i2.235

Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology (D. Carr, Trans.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. (Original work published 1936)

Jehangir, R. R. (2010). Higher education and first-generation students: cultivating community, voice, and place for the new majority. Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230105709

Kantar Group. (2023). What is a good survey response rate? Kantar. Available online at: https://www.kantar.com/inspiration/research-services/what-is-a-good-survey-response-rate-pf (Accessed March 15, 2025).

Ko, M. P., Li, A. Y., and Tan, E. (2023). Profiles of academic and cultural coping among first-generation college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 64, 455–470. doi: 10.1177/15210251231188508

LeBouef, S., and Sieving, R. (2025). Promoting mental health and academic success among first-generation college students: insights for health-care professionals. J. Adolesc. Health 76, 529–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2024.11.243

Liwag, M. E. C. (2022). Role of family expectations in Filipino youth’s psychological development. Philipp. J. Psychol. 55, 18–34.

Liwag, M. E. C., De La Cruz, A. S., and Reyes, M. E. (2022). Family structures and adolescent coping strategies in the Philippines. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 39, 103–120. doi: 10.1007/s10560-021-00783-4

McCombes, S. (2023). Descriptive research design: definition, methods and examples. Scribbr. Available online at: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/descriptive-research/ (Accessed March 10, 2025).

Morake, O. O., and Xue, M. (2025). Exploring stress among international college students in China. arXiv, arXiv:2403.15290. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2503.14139

Musawar, S., and Zulfiqar, A. (2025). Transitioning to college: a cross-sequential study of readiness and coping in first-generation and continuing-generation students. Front. Psychol. 16:1537850. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1537850

Pamisa, R. A., and Cabigas, J. R. (2025). Coping mechanisms and academic resilience of first-generation college students in Mindanao. J. Educ. Hum. Resour. Dev. 13, 112–126.

Panganiban-Corales, A. T., and Medina, M. F. (2011). Family resources, family function and caregiver strain in primary caregivers of children with chronic illness. J. ASEAN Feder. Endocrine Soc. 26, 20–27. doi: 10.15605/jafes.026.01.05

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religion and coping: theory, research, practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1997). Opening up: the healing power of expressing emotions. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ramos, L. (2022). Mexican origin first-generation college students and basic needs insecurity. J. Committed Soc.Change Race Ethnicity 8, 116–134. doi: 10.15763/issn.2642-2387.2022.8.2.115-142

Ramos, M. M., and Kaslow, N. J. (2021). Resilience and psychological outcomes among first-generation college students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 69, 721–729. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1706532

Rivera, L. M., Forquer, E. E., and Rangel, M. A. (2015). Stress and family achievement guilt among Latino first-generation college students. J. Hisp. High. Educ. 14, 105–119. doi: 10.1177/1538192714564911

Salkind, N. J. (2010). Encyclopedia of research design. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781412961288

Smith, A. L., Munoz, J., and Patel, R. (2023). A scoping review of psychosocial risks and resilience among first-generation college students. Rev. Educ. 11:e3418. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3418

Stebleton, M. J., Soria, K. M., and Huesman, R. L. (2014). First-generation students’ sense of belonging, mental health, and use of counseling services at public research universities. J. Coll. Couns. 17, 6–20. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2014.00044.x

Stephens, N. M., Fryberg, S. A., Markus, H. R., Johnson, C. S., and Covarrubias, R. (2012). Unseen disadvantage: how American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 1178–1197. doi: 10.1037/a0027143

Tuason, M. T. G., Taylor, A. R., Rollings, K., Harris, R., and Martin, J. (2007). On family influence: the family’s role in self-efficacy and depression among Filipinos. J. Psychol. 141, 493–520. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.141.5.493-520

Tuovila, A. (2024). Sampling: Definition, importance, types, and examples : Investopedia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sampling.asp

Varvogli, L., and Darviri, C. (2011). Stress management techniques: evidence-based procedures that reduce stress and promote health. Health Sci. J. 5, 74–89.

Wang, W., Tang, F., and DeLaquil, T. (2022). Assessing mental health of first-generation students. Front. Psychol. 13:1002389. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1002389

West, H. M., Flain, L., Davies, R. M., Shelley, B., and Edginton, O. T. (2024). Medical student wellbeing during COVID-19: a qualitative study of challenges, coping strategies, and sources of support. BMC Psychol. 12:179. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-01606-w

Wilbur, T. G., and Roscigno, V. J. (2016). First-generation disadvantage and college enrollment/completion. Sociol. Inq. 86, 217–244. doi: 10.1111/soin.12125

Keywords: family structures, coping behaviors, first generation, cognitive reappraisal, first-generation college students, psychological resilience

Citation: Tangco-Siason A (2025) Coping behaviors of first-generation college students across family structures. Front. Educ. 10:1676887. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1676887

Edited by:

Elizabeth Fraser Selkirk Hannah, University of Dundee, United KingdomReviewed by:

Francis Thaise A. Cimene, University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, PhilippinesStephanie Cuellar, Texas Christian University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Tangco-Siason. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amabel Tangco-Siason, YXRzaWFzb25Ad3ZzdS5lZHUucGg=

Amabel Tangco-Siason

Amabel Tangco-Siason