- 1Department of Pedagogy, Faculty of Social Sciences, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Astana, Kazakhstan

- 2Department of Education, Faculty of Education Sciences, Düzce University, Ankara, Türkiye

- 3Department of Pedagogy, Faculty of History and Education, Kazakhstan Pedagogical University named after U. Zhanibekov, Shymkent, Kazakhstan

This qualitative study explores the perceptions and experiences of teachers, school psychologists, and principals regarding bullying prevention among adolescent girls in schools in Shymkent, Kazakhstan. The research aims to understand the specific nature of bullying experienced by girls, assess the readiness of school staff to intervene, and identify the roles of key stakeholders in anti-bullying efforts. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 12 female and 2 male participants representing diverse roles in the school system. Thematic analysis revealed four key themes: (1) the relational and emotional nature of bullying among girls, (2) barriers to teacher intervention, including limited training and difficulty in recognizing covert behaviors, (3) collaborative efforts and multi-layered strategies for bullying prevention, and (4) the evolving gender dynamics in bullying patterns. While findings highlight promising practices such as anonymous surveys, role-playing activities, and partnerships with school psychologists, they also expose inconsistencies in school-wide policies and a need for standardized intervention protocols. The study underscores the importance of a whole-school approach and calls for targeted teacher training, structured coordination among staff, and policy-level reforms tailored to the cultural and systemic context of Kazakhstan.

1 Introduction

School bullying remains one of the most persistent challenges to students’ emotional well-being, academic success, and overall school climate. Defined as deliberate and repeated aggressive behavior that involves an imbalance of power (Olweus, 1993), bullying can manifest physically, verbally, socially, or digitally, and often leaves lasting psychological scars on victims (Katsikas and Thanos, 2025). Among adolescent students, particularly girls, bullying is frequently relational in nature, involving exclusion, rumor-spreading, and manipulation of social networks (Espelage et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2009). These less visible forms of bullying including covert social exclusion and cyberbullying are especially difficult to detect, as they often unfold in subtle interactions or in digital spaces beyond adult supervision (Tokunaga, 2010). Their invisibility heightens the harm for victims, who may experience long-term psychological consequences while receiving little support or recognition from teachers and school staff (Underwood, 2003).

In Kazakhstan, this issue takes on added cultural dimensions. Social and relational bullying is often intertwined with broader social hierarchies, gender norms, and cultural expectations around modesty and obedience, which discourage open confrontation or disclosure (Koptleuova, 2023). Cyberbullying has also gained prominence, with cases of humiliation via social media leading to severe psychological outcomes, sometimes even self-harm. Despite these pressing realities, research on bullying in Kazakhstan remains sparse, and even fewer studies have examined teachers’, school psychologists’, and principals’ perceptions of prevention strategies. While international literature has extensively documented the dynamics of covert bullying, its cultural manifestations in Central Asia and particularly in Kazakhstani schools remain largely underexplored. This gap underlines the need for context-specific insights into how educational professionals recognize and respond to these challenges.

Globally, large-scale studies reveal the urgency of tackling bullying: a UNESCO report found that one in three students worldwide has experienced bullying in some form (UNESCO, 2019). Regionally, approximately one in four students in Kazakhstan has reported experiencing bullying, with many cases unreported due to fear of retaliation or cultural stigma (UNESCO, 2019). These figures highlight not only the pervasiveness of the problem but also the necessity of culturally sensitive and systemic responses.

The complexity of school bullying necessitates a systemic response rather than relying solely on the actions of individual teachers. Research consistently emphasizes that effective prevention and intervention strategies must be integrated into a whole-school approach involving collaboration between teachers, school psychologists, counselors, and school principals (Swearer et al., 2010; Waseem and Nickerson, 2024). Yet, in many school contexts, particularly in systems where academic pressure dominates, teachers often feel isolated in their response efforts, constrained by limited time, insufficient training, or unclear institutional policies (Bradshaw, 2015; Yoon and Bauman, 2014). This fragmentation can undermine comprehensive anti-bullying strategies, resulting in inconsistent practices and reduced trust among students.

Collaboration among professionals is therefore widely recognized as a cornerstone of successful bullying prevention initiatives. Teachers play a critical frontline role in detecting early signs of bullying within the classroom, while school psychologists contribute with their specialized expertise in emotional and behavioral assessment. School principals, on the other hand, are instrumental in embedding anti-bullying frameworks into the school’s policy infrastructure, ensuring accountability and resource allocation (Rigby, 2020; Ttofi and Farrington, 2011). When these roles are siloed or weakly coordinated, intervention efforts risk becoming reactive, fragmented, or superficial. The urgency to develop a coherent and collaborative response is heightened by findings that many bullying incidents, especially those involving girls, remain unreported or unresolved due to their covert nature (Mishna et al., 2005; Nansel et al., 2001).

This study explores the shared responsibilities of teachers, psychologists, and school principals in schoolwide bullying prevention efforts. By situating the analysis within Kazakhstan’s cultural and institutional context, it aims to fill a significant research gap and contribute to the international literature on covert and relational bullying. Specifically, it investigates how collaboration is practiced, perceived, and institutionalized, with the goal of uncovering the conditions that facilitate or hinder effective team-based responses to bullying. In doing so, it offers practical insights for building more cohesive and proactive anti-bullying frameworks in Kazakhstan and beyond.

2 Literature review

2.1 Understanding school bullying: definitions and forms

School bullying is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon characterized by intentional aggression, repetition over time, and a power imbalance between perpetrator and victim (Olweus, 1993). While physical and verbal bullying are more visible, relational bullying especially among girls manifests in subtle ways such as social exclusion, rumor-spreading, and manipulation of friendships (Crick and Grotpeter, 1995 Wang et al., 2009). These covert forms of aggression can be emotionally damaging yet often go unnoticed by educators (Mishna et al., 2005). The rise of digital platforms has also expanded bullying into virtual spaces, giving rise to cyberbullying, which can occur anonymously and beyond school boundaries (Tokunaga, 2010). However, traditional in-school bullying remains prevalent and requires targeted, collaborative strategies for prevention and intervention, particularly when addressing gender-specific manifestations.

2.2 The need for a whole-school approach

Empirical studies increasingly support a whole-school approach to bullying prevention, where success depends not solely on individual actors but on systemic coordination (Swearer et al., 2010; van Aalst et al., 2024). Whole-school models emphasize shared responsibility among all educational stakeholders teachers, school leaders, mental health professionals, and parents to foster a safe and inclusive learning environment (Ttofi and Farrington, 2011). These models often incorporate school-wide policies, classroom-based instruction, social–emotional learning, and staff development. A meta-analysis by Ttofi and Farrington (2011) found that interventions were more effective when supported by consistent administrative leadership and when school personnel received training to recognize and act upon bullying behaviors. Yet, real-world implementation often falls short of this ideal due to fragmented responsibilities, unclear communication channels, or institutional inertia (González-Alonso et al., 2020). Recent studies in Central Asia similarly emphasize the hidden nature of bullying. For instance, research in Kazakhstan (Assylbekova et al., 2024) and Kyrgyzstan (Ayhan et al., 2025) highlights how covert forms such as social exclusion and gossip dominate, yet remain underreported due to cultural norms and limited institutional response mechanisms.

2.3 Teachers’ role in identifying and responding to bullying

Teachers are typically the first line of defense in school bullying situations. Their capacity to detect and respond effectively is crucial, especially since students rarely report incidents directly to adults (Yoon and Bauman, 2014). However, studies show that many teachers feel underprepared or unsupported, particularly when dealing with emotional or relational bullying that requires more than disciplinary action (Bauman and Del Rio, 2006). Teachers’ personal beliefs about the severity of bullying, their confidence in handling cases, and the presence of institutional support significantly affect their likelihood of intervening (Bradshaw et al., 2013). Moreover, teachers may struggle to balance academic responsibilities with social–emotional monitoring, particularly when incidents occur during instruction time (Rigby, 2020). This necessitates institutional structures that reduce the burden on individual teachers and promote a culture of shared responsibility.

2.4 The role of school psychologists and counselors

School psychologists and counselors play a specialized yet often underutilized role in bullying prevention. Their expertise in student mental health, peer relationships, and trauma-informed practices positions them as essential actors in both preventive education and targeted intervention (O’Brien et al., 2024). Effective bullying programs often include psychological assessments, conflict resolution training, and therapeutic support for victims and perpetrators alike (Swearer and Hymel, 2015). Despite their centrality, school psychologists are often spread too thin across multiple schools or overloaded with administrative tasks, limiting their proactive involvement (Bocanegra et al., 2017). Collaborative planning between teachers and psychologists is critical to ensure that psychological expertise informs classroom management and student relationship-building efforts.

2.5 School principals as strategic enablers of prevention

School principals and vice principals are vital for embedding anti-bullying policies into the broader institutional framework. Their leadership determines whether anti-bullying initiatives are treated as core priorities or peripheral activities (Smith, 2018). School principals allocate resources, set disciplinary policies, oversee staff training, and shape school climate through modeling and policy enforcement. Research shows that administrative support is positively correlated with teachers’ likelihood to intervene in bullying incidents (Dedousis-Wallace et al., 2013). Conversely, lack of visible leadership or follow-through from school leaders often leads to staff disillusionment or passive compliance with ineffective protocols (Hong and Espelage, 2012).

2.6 Inter-professional collaboration in bullying prevention

Collaboration across school roles is both a theoretical ideal and a practical necessity. Studies highlight that interdisciplinary cooperation between classroom teachers, special educators, counselors, and school principals leads to more timely identification of bullying, consistency in response, and holistic student support (Craig et al., 2007). However, successful collaboration depends on clear communication, shared goals, and mutual respect between professionals (Kenny et al., 2023). Barriers to collaboration often include role ambiguity, time constraints, and hierarchical school cultures that limit cross-role dialog (Herkama et al., 2022). Therefore, structured team-based interventions and professional learning communities can foster alignment and collective efficacy in bullying prevention efforts.

2.7 The Kazakhstan context

In Kazakhstan, bullying behaviors are also shaped by cultural and social norms. Collectivist values encourage conformity and discourage confrontation, making victims reluctant to report incidents. Gendered expectations such as modesty, obedience, and preserving family honor further silence adolescent girls, while boys are often excused for physical aggression as part of masculinity norms (Koptleuova, 2023). These cultural dynamics not only mask the prevalence of bullying but also complicate the adoption of Western-derived intervention models. In Kazakhstan, bullying in schools referred to as “қорлау” has gained increasing attention in recent years, particularly due to rising concerns about school safety and student well-being. A UNESCO (2019) report found that approximately 1 in 4 students in Kazakhstan had experienced bullying, with many cases going unreported due to fear of retaliation or lack of trust in adult interventions.

Kazakhstani schools typically operate within a centralized educational structure, where class teachers (“сынып жетекшілері”) play a central role in student supervision and moral development. However, school psychologists often face large student caseloads, and teacher training on bullying is limited to one-off seminars or written policy guidelines (Assylbekova et al., 2024). Moreover, cultural expectations about conflict avoidance and collective harmony can sometimes prevent open discussion of peer aggression, especially among girls (Koptleuova, 2023). Although national education reforms under the “Kazakhstan 2050” strategy emphasize student well-being, practical challenges persist in implementing comprehensive bullying prevention programs (Duisenova and Kylyshbayeva, 2016). Therefore, examining how Kazakhstani schools facilitate or struggle with inter-professional collaboration in bullying prevention can offer important insights for policy and practice. Prominent intervention models such as the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (Olweus, 1993) and Finland’s KiVa Program (Kärnä et al., 2011) have demonstrated the effectiveness of structured, school-wide approaches that combine curriculum, teacher training, and student involvement. Although developed in different cultural contexts, these models provide useful frameworks for Kazakhstan, where prevention programs remain fragmented and policy implementation inconsistent.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Research method

This study adopts a qualitative case study methodology to explore the collaborative roles of teachers, school psychologists, and school principals in bullying prevention efforts within a single school context. A qualitative approach is particularly well-suited for examining complex, context-bound social phenomena such as school-based collaboration, which involves interpersonal dynamics, institutional structures, and cultural nuances that cannot be adequately captured through quantitative metrics alone (Creswell and Poth, 2018). Rather than measuring predefined variables, this study seeks to understand the lived experiences, perceptions, and interrelations of key educational actors in their efforts to prevent bullying among students, especially adolescent girls. The case study design is chosen for its strength in offering an in-depth, holistic investigation of a real-world setting (Yin, 2018). Since the aim of the research is to explore the collaborative processes and institutional practices within a specific school rather than to generalize across a broad population a single case study allows for the detailed exploration of context-specific dynamics, policies, and actor perspectives. This design supports the examination of both individual and institutional behaviors and how they intersect within the ecosystem of school bullying prevention. Moreover, a case study enables the triangulation of multiple data sources including interviews, observations, and policy documents which enhances the credibility and richness of the findings (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016).

3.2 Participants

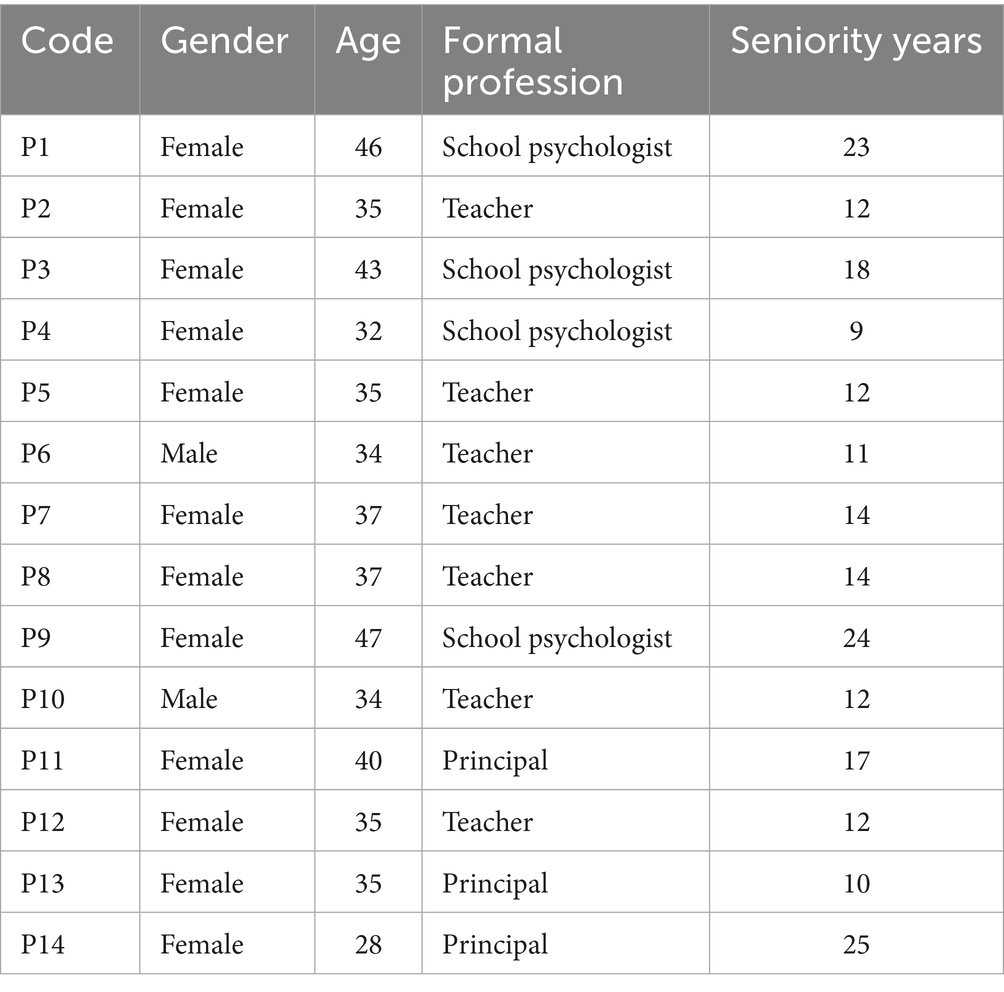

This study involved 12 female and 2 male participants working in secondary schools located in Shymkent, Kazakhstan. The participants were purposefully selected to reflect diverse professional roles involved in bullying prevention at the school level. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling based on their direct professional engagement in bullying prevention. Selection criteria included (a) at least 5 years of professional experience in teaching, counseling, or school administration; (b) current involvement in addressing or managing bullying incidents; and (c) representation from diverse roles to capture multiple perspectives. Although students and parents were not direct participants in this study, observational data on classroom interactions and follow-up reflections with teachers provided indirect insights into student dynamics and parental involvement. They included teachers (n = 7), school psychologists (n = 4), and school principals (n = 3). All participants had direct experience working with adolescent girls and were actively engaged in educational, psychological, or administrative interventions aimed at preventing bullying in school contexts. Participants ranged in age from 28 to 47 years, with an average age of approximately 37 years. Their professional experience also varied widely, with seniority ranging from 5 to 24 years (mean = 13.2 years), offering both early-career and veteran insights into bullying-related issues in schools. The psychologists had an average of 18.5 years of experience, while teachers averaged 12.4 years, and principals had an average of 17.3 years of professional service. Table 1 shows some details of participants. This distribution provided a balanced perspective: teachers as frontline observers, psychologists as specialists, and principals as policy enforcers. Such variation enriched the data by capturing experiences from daily classroom monitoring to institutional leadership.

3.3 Data collection, analyze, and trustworthiness

Data were collected from five public secondary schools in Shymkent, Kazakhstan to explore how teachers, psychologists, and principals collaborate in preventing bullying among adolescent girls. Sessions were audio-recorded with consent and supported by field notes. Following observations, brief reflective discussions were held with participants using anonymized observation notes to gather their interpretations of classroom dynamics and bullying-related incidents. In-depth interviews were conducted with 14 participants seven teachers, four psychologists, and three principals. Conducted in Kazakh or Russian, the interviews explored their experiences and collaborative efforts in addressing bullying. The core interview questions included the following:

• What types of bullying among adolescent girls have you observed at your school?

• In your opinion, what are the main causes of bullying among girls?

• How prepared do you feel to identify and respond to bullying situations?

• What specific actions have you taken in your professional experience to prevent or stop bullying?

All interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent and later transcribed verbatim for thematic analysis. In total, over nearly 11 h of interview data were collected. The interview protocol was designed to elicit both personal reflections and institutional insights, enabling the research to capture multiple layers of the collaborative dynamic in anti-bullying efforts. This sequential data collection approach allowed for triangulation, enhancing the credibility and depth of the findings.

Semi-structured interviews were guided by an interview protocol that included open-ended core questions and follow-up probes (e.g., “Can you provide a concrete example?” or “How did colleagues respond in that situation?”). Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step framework: (1) familiarization with data through repeated reading of transcripts, (2) generation of initial codes, (3) searching for patterns across codes, (4) reviewing candidate themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) producing the final narrative report. Several strategies were employed to enhance the trustworthiness of findings and reduce researcher bias. Triangulation was achieved by combining interview data with school policy documents. Member checking was conducted by sharing preliminary interpretations with four participants to confirm accuracy. Reflexive journaling was maintained throughout the research to document the researchers’ assumptions and decisions. In addition, coding and theme development were discussed with a peer researcher to ensure intersubjective validation and reduce individual subjectivity.

4 Results

4.1 Theme 1: main causes of bullying among adolescent girls

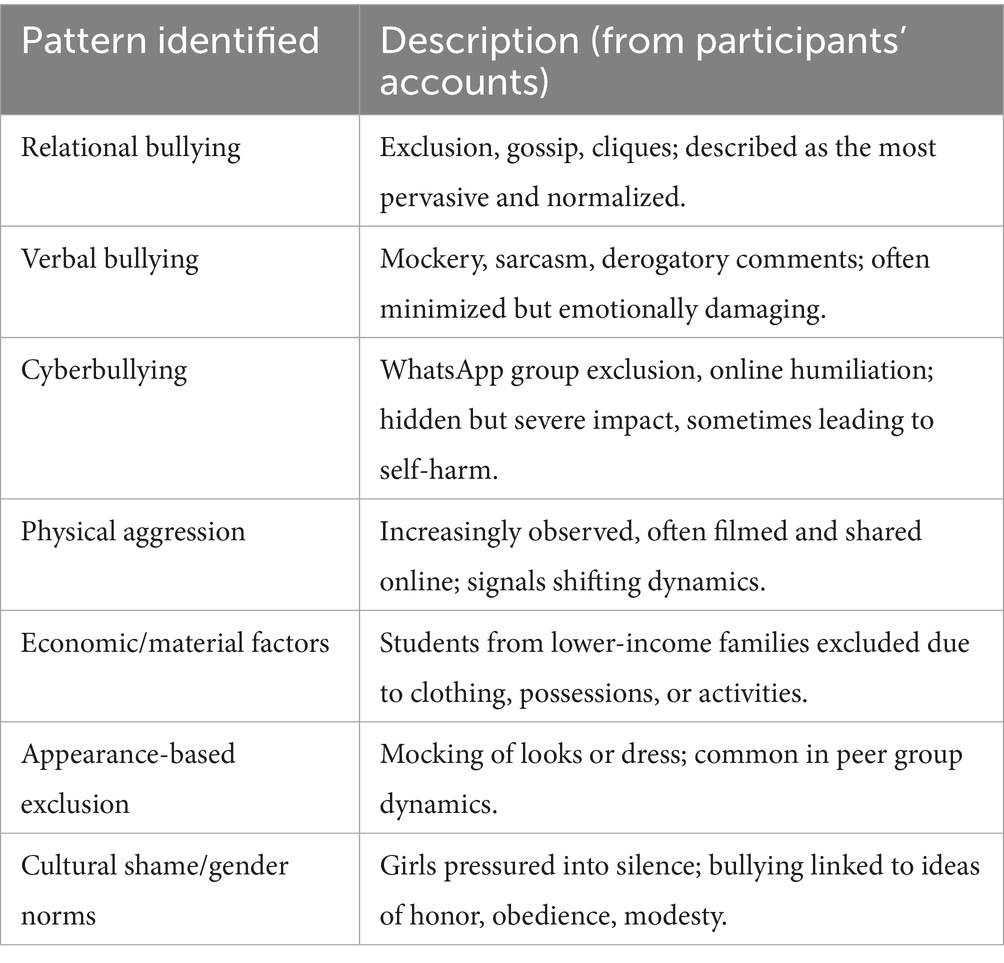

Teachers identified the main causes of bullying among girls as rooted in relational dynamics like exclusion, jealousy, and peer group cliques. Many noted that girls often use subtle tactics ignoring, gossiping, or isolating others to assert control. Socioeconomic differences also contribute, with girls from less affluent families more likely to be excluded. Several participants highlighted the rise of cyberbullying, which is harder to detect but deeply harmful. Table 2 shows some causes and types of bullying among girls.

As shown in Table 2, relational bullying emerged as the dominant form, with participants describing it as ‘routine’ and often unnoticed by adults. Cyberbullying, while less visible, was portrayed as deeply destructive, especially given cultural taboos around shame. Socioeconomic and appearance-based differences further compounded exclusionary practices, reinforcing stratification within peer groups. Out of 14 participants, 9 emphasized relational bullying as the most frequent, while 6 stressed cyberbullying as increasingly destructive. This indicates that while relational aggression remains the most pervasive form, teachers increasingly recognize the severity of digital bullying.

4.1.1 The pervasiveness and normalization of relational bullying

One of the most dominant findings across participants was the pervasive nature of relational bullying, often expressed through social exclusion, indirect aggression, and manipulation of friendships. This type of bullying, while subtle, was repeatedly described as a routine part of adolescent girlhood and one that is frequently misinterpreted or overlooked by adults. Participant 1 articulated this mechanism with clarity, emphasizing how friendship cliques and material inequalities often trigger social exclusion:

“One of the primary causes of bullying among girls is when two girls become close friends and deliberately exclude a third girl, either by not including her in their social circle or by disagreeing with her opinions. Additionally, material inequality can also play a role for example, if two girls can afford to buy the things they want regularly while the third girl cannot due to financial limitations, she may be excluded from the group.”

This quote underscores how economic status becomes a proxy for social belonging, leading to exclusionary behaviors that reflect broader social stratification within school settings. The implications of such exclusions go beyond temporary hurt they erode girls’ sense of belonging and reinforce feelings of inferiority. Likewise, Participant 13 provided a powerful account of digitally mediated exclusion, stating:

“Girls often form separate groups and isolate others. For example, they create private WhatsApp groups and deliberately exclude certain girls. This kind of behavior deeply affects the excluded student, making her feel unwanted and withdrawn. She begins to think that she does not belong anywhere, and that no one sees her.”

This testimony reveals not only the psychological damage of exclusion but also the increasingly hybrid nature of bullying, where social aggression continues seamlessly across physical and digital spaces. Such behaviors foster an environment where isolation is normalized and emotional suffering is hidden beneath everyday interactions.

4.1.2 Verbal bullying and emotional abuse

Another widely acknowledged form of bullying among girls was verbal aggression, including mocking, teasing, gossiping, and derogatory comments. These behaviors are often minimized by both students and teachers but are described by participants as emotionally destructive and far-reaching. Participant 10 recounted the pervasive nature of verbal bullying and how it intersects with gender and intelligence stereotypes:

“Yes, various forms of bullying directed at girls can be observed. These include both verbal and non-verbal bullying, gender-based mockery, and teasing. There are also cases of teasing related to girls’ thinking abilities girls who are either too quiet or too outspoken are labeled in a hurtful way, and this often leads to further isolation.” This quote draws attention to how bullying not only enforces social conformity but also punishes deviation from gender norms. Girls who do not fit the expected behavioral mold become easy targets, and the mocking often escalates into chronic social marginalization.

Participant 11 described how even everyday verbal exchanges can carry hurtful undertones that gradually wear down a student’s confidence: “We mostly observe verbal bullying, such as insults, mocking, or offensive remarks. Social exclusion is also common when a student is isolated or deliberately left out of the group. Sometimes it’s not what is said, but the way things are said, or when everyone laughs except the one being targeted. That silence speaks loudly.” This reflection highlights the emotional violence embedded in tone, silence, and group dynamics, reinforcing that bullying is often executed through unspoken yet coordinated behaviors.

4.1.3 The rise of cyberbullying and physical aggression

Participants also expressed increasing concern about cyberbullying, which, unlike traditional forms, occurs persistently and often invisibly to teachers. The emotional harm inflicted through digital platforms can be sudden, overwhelming, and public. Participant 3 offered a deeply unsettling account of the escalating consequences of cyberbullying in Kazakhstan’s cultural context: “Cyberbullying is rampant across the country there are incidents where girls commit suicide by jumping from high buildings due to being humiliated or threatened via social media and messaging apps. These girls, unable to endure the shame in our cultural context, take their own lives. They are trapped between fear, shame, and the lack of someone to trust.” This quote reflects not only the extreme psychological harm caused by digital harassment but also the cultural silencing mechanisms such as shame and honor that prevent girls from speaking up or seeking help. The intersection of technology and tradition, in this case, creates a particularly dangerous space for vulnerable girls.

In addition to digital violence, multiple participants noted an alarming increase in physical altercations among girls. As Participant 4 put it: “We’ve had several incidents recently where girls fought in the schoolyard. They recorded it on their phones and shared it. What’s worrying is how normal it seems to them. The boundary between verbal aggression and physical aggression is getting blurry.” The rise in physical aggression, once considered rare among girls, signals a shift in the expression of power and status among adolescents, potentially influenced by media portrayals of violence and the viral nature of online content.

4.1.4 Divergent school contexts and hidden realities

Interestingly, not all participants reported high rates of bullying. Participant 2, who works in an elite academic institution, stated: “I work at a school for gifted students, where students generally exhibit high levels of discipline and maintain respectful relationships with one another. There are no noticeable forms of open or covert bullying among the girls. Some students may appear introverted and avoid interacting with peers, but this is usually due to their individual personality traits rather than exclusion by others.” While this account may reflect a genuinely low rate of observable bullying, it also reveals a potential blind spot. In schools where academic success and discipline are highly prized, relational bullying may be more discreet, and introversion may mask emotional withdrawal caused by peer rejection. The assumption that high-achieving students are immune to bullying risks overlooking the hidden forms of suffering.

4.1.5 Gender, cultural shame, and emotional repercussions

Finally, several participants linked bullying to gender expectations and cultural shame, which exacerbate the emotional toll on girls. Participant 14 explained: “Relational bullying is quite common girls exclude each other, mock, say hurtful words, and damage interpersonal relationships. These behaviors may seem small individually, but over time, they destroy friendships and create a toxic atmosphere where no one feels safe.” Such views suggest that bullying functions not just as an act of aggression but as a tool of social positioning, with girls using it to control group dynamics and protect their status. Cultural norms around female modesty, obedience, and emotional restraint mean that victims are often hesitant to report or confront their bullies, perpetuating cycles of silence and internalized distress.

4.2 Theme 2: readiness to identify and respond to bullying

Participants expressed varying degrees of preparedness to identify and respond to bullying among adolescent girls, highlighting diverse strategies, barriers, and personal reflections.

4.2.1 Excerpt 1: participant 2’s responses

“I consider myself well-prepared. As a teacher, I closely observe each student and pay attention to their emotional well-being. When difficulties arise, I am ready to speak with the student privately and, if necessary, collaborate with the school psychologist to address the issue.”

As Excerpt 1 illustrates, Participant 2 demonstrated a proactive stance toward bullying intervention, emphasizing careful observation, emotional attentiveness, and the readiness to collaborate with specialized staff. Such an approach reflects an understanding that bullying intervention requires both individual initiative and teamwork.

4.2.2 Excerpt 2: participant 13’s responses

“I would say I’m partially prepared to identify bullying cases. I can usually detect overt verbal or social bullying. However, hidden forms of bullying especially cyberbullying are harder to detect. Students do not want to show their phones, and as teachers, we do not have the authority to monitor their online activities. One of the main barriers in Kazakhstani schools is the lack of a fully implemented and clear mechanism to address bullying. Moreover, parents sometimes refuse to accept that their child may have aggressive behavior and instead blame the teacher. This undermines the teacher’s motivation to intervene. What helps me most is experience and close collaboration with the school psychologist. If there is proper support from school administration, psychologists, and parents, I would feel completely ready to deal with bullying effectively.”

As Excerpt 2 clearly shows, Participant 13 highlighted critical institutional and systemic challenges, such as insufficient policy frameworks, limited teacher authority, and parental resistance. These challenges significantly hinder teacher readiness despite substantial professional experience. Participant 13’s perspective underscores the necessity for integrated systemic support to enhance teachers’ confidence and effectiveness in intervention.

4.2.3 Excerpt 3: participant 1’s responses

“If I were to assess my own readiness to identify and respond to bullying cases, I cannot confidently say I am 100% prepared. Recognizing different types of bullying and effectively addressing them is often beyond the capabilities of a subject teacher alone. These issues usually require the involvement of school psychologists or social workers. Therefore, if I witness any unusual or concerning behavior, I report it to the appropriate specialists.”

As depicted in Excerpt 3, Participant 1 expressed uncertainty and reliance on specialist intervention. This response highlights an important recognition of professional limits, emphasizing the crucial role of multidisciplinary collaboration in effectively managing bullying situations.

4.2.4 Excerpt 4: participant 3’s responses

“I cannot say I feel fully prepared yet because sometimes, when I try to intervene, I end up being blamed. There is no real justice in our country.”

Excerpt 4 poignantly reflects Participant 3’s deep frustration with systemic injustice, indicating significant emotional and professional obstacles faced by teachers who attempt intervention without adequate institutional support. This statement powerfully demonstrates how broader societal attitudes and structural deficiencies affect teachers’ motivation and perceived readiness to respond effectively.

4.2.5 Excerpt 5: participant 5’s responses

“I always try my best to identify bullying, especially among girls. Compared to boys, it is much harder to detect bullying among girls because it is often subtle for example, excluding someone from a WhatsApp group or other online spaces. Such behavior is not easily noticeable from the outside. To detect it, we need to do a lot of work. I try to observe social dynamics by speaking with some of the more outgoing or socially active girls and engaging them in conversation, which can help me understand the hidden interactions.”

Participant 5’s detailed strategy, as highlighted in Excerpt 5, underscores the nuanced understanding and proactive approaches teachers must adopt to detect subtle forms of relational bullying. It further reveals the considerable effort required from teachers to uncover hidden social dynamics, reinforcing the need for ongoing professional training and support systems. These excerpts collectively illustrate a range of teacher experiences, strategies, and challenges regarding their readiness to effectively identify and address bullying, emphasizing the necessity for structured institutional support, clear policies, and multidisciplinary collaboration. Teachers’ ability to act depends less on individual commitment than on institutional support. The lack of standardized national training, absence of clear anti-bullying protocols, and weak parental-school cooperation mean responses remain inconsistent.

4.3 Theme 3: working together to create bully-free learning environments

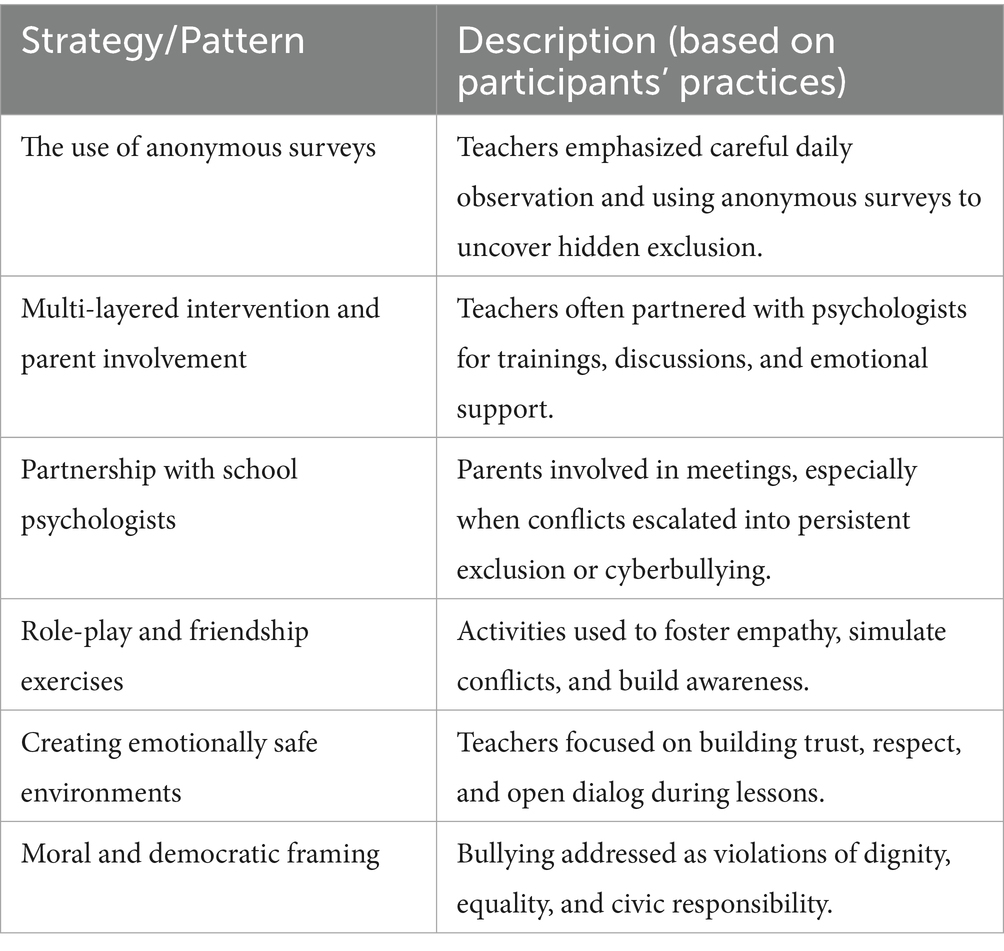

The third theme focuses on teachers’ concrete actions to prevent bullying, illustrating diverse approaches including awareness-raising activities, structured classroom interventions, collaboration with psychologists, and parent engagement. Table 3 Shows some strategies used by participants to prevent bullying.

The strategies presented in Table 3 reveal a multi-layered approach. Teachers did not rely on a single tactic but combined classroom-based exercises (role-play, friendship activities), institutional partnerships (psychologists, administrators), and parental engagement. A notable theme was the use of anonymous surveys, which helped uncover hidden relational bullying and guided early interventions. Teachers also framed their actions within moral and civic values, signaling a strong ethical dimension to their preventive efforts. However, participants also emphasized that such collaborative strategies are often improvised rather than guided by official policy frameworks. This reliance on teachers’ creativity reflects a gap in Kazakhstan’s centralized education system, where national directives on bullying remain general and lack operational clarity.

4.3.1 The use of anonymous surveys

This sub-category refers to teachers’ use of regular, confidential surveys to uncover hidden forms of bullying, particularly social exclusion and relational aggression. Such surveys allow students to express their perceptions and experiences without fear of exposure or retaliation. One powerful example mentioned by participants was asking indirect social questions like, “Which three classmates would you invite to your birthday?” and “Which three classmates would you not invite?” These non-threatening, reflective prompts helped identify students who were consistently excluded or isolated indicators of relational bullying that may not be outwardly visible during regular classroom interactions.

Teachers emphasized that even when a class appears harmonious on the surface, anonymous feedback often reveals underlying social tensions. By analyzing these patterns, participants can initiate early interventions, hold individual or group conversations, and monitor students at risk of being marginalized. This strategy also enhances teachers’ understanding of classroom dynamics and provides actionable insights for psychological support staff.

Interviewee (P9): Every 2 weeks, I conduct anonymous surveys among students, even if everything seems fine on the surface.

Researcher: What kind of questions do you ask?

Interviewee (P9): For example, “Which three classmates would you invite to your birthday?” and “Which three classmates would you not invite to your birthday?” This help reveal patterns of exclusion.

As Excerpt 1 shows, the teacher uses strategic questioning to uncover hidden social hierarchies and exclusion among students. This pre-emptive approach enables early detection of relational bullying and allows for timely interventions in classroom dynamics.

4.3.2 Multi-layered intervention and parent involvement

This sub-category captures a comprehensive and collaborative approach to bullying prevention, where participants respond to incidents through a sequence of targeted actions involving multiple stakeholders students, teachers, parents, school administrators, and psychologists. Participants described real-life situations in which relational bullying, particularly among girls, required more than just classroom discipline or brief counselling sessions.

Multi-layered intervention typically began with individual conversations with the students directly involved both the aggressor and the victim to explore the emotional context and underlying causes. This was followed by whole-group sessions, where the broader social dynamics of the class were addressed. In some cases, despite these initial efforts, the bullying behavior persisted, often moving into digital spaces (e.g., exclusion from class group chats). When classroom strategies proved insufficient, teachers escalated the issue to school leadership and involved parents.

Interviewee (P10): We organized seminars and training sessions, and in one specific case, I held private conversations with both the victim and the aggressor. Later, the issue was addressed in a group meeting involving all the girls.

Researcher: Did the problem resolve?

Interviewee (P10): Not immediately. The conflict continued online. Eventually, I involved the administration and parents. During the parent meeting, the situation was discussed openly, and parents began to acknowledge their daughters’ behaviors. The exclusion finally stopped after this full-circle intervention.

Excerpt 2 demonstrates a layered response that spans individual guidance, peer mediation, institutional involvement, and parental cooperation. The complexity of the case underlines the importance of persistence and multi-stakeholder engagement in conflict resolution.

4.3.3 Partnership with school psychologists

This sub-category emphasizes the collaborative relationship between teachers and school psychologists in both the prevention and intervention phases of bullying. Participants frequently highlighted that, while subject and homeroom teachers are often the first to notice behavioral changes or receive complaints from students, school psychologists provide the specialized knowledge and psychological tools necessary to address bullying in depth.

In many cases, teachers reported initiating cooperation by referring students to psychologists when emotional distress, social withdrawal, or signs of peer conflict were observed. These referrals were followed by joint planning of preventive activities, such as class-wide discussions, empathy training, or peer relationship exercises. Some participants described co-facilitating workshops or classroom sessions with psychologists on topics such as friendship, emotional regulation, and respectful communication.

Interviewee (P12): Together with the school psychologist, we ran training sessions and group discussions.

Researcher: What were the topics?

Interviewee (P12): Friendship, communication, empathy basically themes that help students relate to one another better. We also used educational films and video clips.

As Excerpt 3 indicates, the teacher collaborates with school psychologists to provide psychoeducational content aimed at enhancing students’ social and emotional competencies. These interventions were not only reactive but proactively fostered a sense of peer belonging.

4.3.4 Creating emotionally safe environments

This sub-category focuses on the proactive strategies employed by participants to foster a school climate where students particularly adolescent girls feel valued, heard, and emotionally secure. Rather than responding only when bullying occurs, participants described building daily relational foundations that prevent bullying behaviors from developing in the first place. Teachers emphasized the importance of establishing trust-based relationships with students by listening attentively, validating their emotions, and promoting open dialog during lessons or class meetings. Emotional safety was often nurtured through ongoing discussions around mutual respect, digital etiquette, and empathy, especially during homeroom or value-based sessions.

Interviewee (P2): In every lesson, I focus on building trust. I listen to every opinion and promote emotional safety. During class meetings, we discuss mutual respect and digital etiquette.

Researcher: So, you treat each class as a space for values education?

Interviewee (P2): Exactly.

Excerpt 4 illustrates a preventive pedagogical stance where the emotional tone of the classroom is shaped consistently through daily teacher-student interactions. This values-based atmosphere sets the groundwork for respectful and inclusive student behavior.

4.3.5 Role-play and friendship exercises

Role-play was used to simulate real-life conflict scenarios or bullying incidents, allowing students to step into the shoes of both the victim and the aggressor. Teachers noted that such exercises created moments of reflection and emotional realization, especially when students recognized the psychological harm caused by exclusion, mockery, or verbal aggression. These activities served not only to increase awareness but also to encourage behavioral change through emotional insight.

Interviewee (P4): I’ve held educational sessions and used role-playing exercises to help students better understand emotions. I’ve also conducted one-on-one meetings with girls involved in conflicts.

This excerpt highlights experiential learning techniques such as role-play, used to enhance emotional intelligence and encourage behavioral change. These sessions enabled deeper interpersonal awareness among students, especially girls involved in covert forms of bullying.

4.3.6 Moral and democratic framing

Participants explained that when bullying was observed whether verbal, relational, or physical they intervened not only to stop the behavior but also to initiate value-based conversations. In these discussions, students were reminded that every individual deserves respect, and that discrimination, exclusion, or humiliation violates shared community norms. Teachers framed these actions as antithetical to democratic principles, such as gender equality, mutual respect, and the protection of vulnerable individuals.

Interviewee (P9): When I observe bullying verbal or physical I intervene immediately. I explain that such behavior contradicts the values of mutual respect and gender equality. We frame it as an issue of human dignity and civic responsibility.

As shown in Excerpt 6, teachers often embed anti-bullying messages in broader ethical and democratic discourses. This framing helps students internalize moral reasoning that discourages exclusionary or aggressive behavior. Together, these excerpts provide a rich portrait of school-based actions taken by participants to prevent bullying. The strategies reveal a shared commitment to relational health, proactive engagement, and inclusive learning environments.

4.4 Theme 4: gender-specific characteristics of bullying

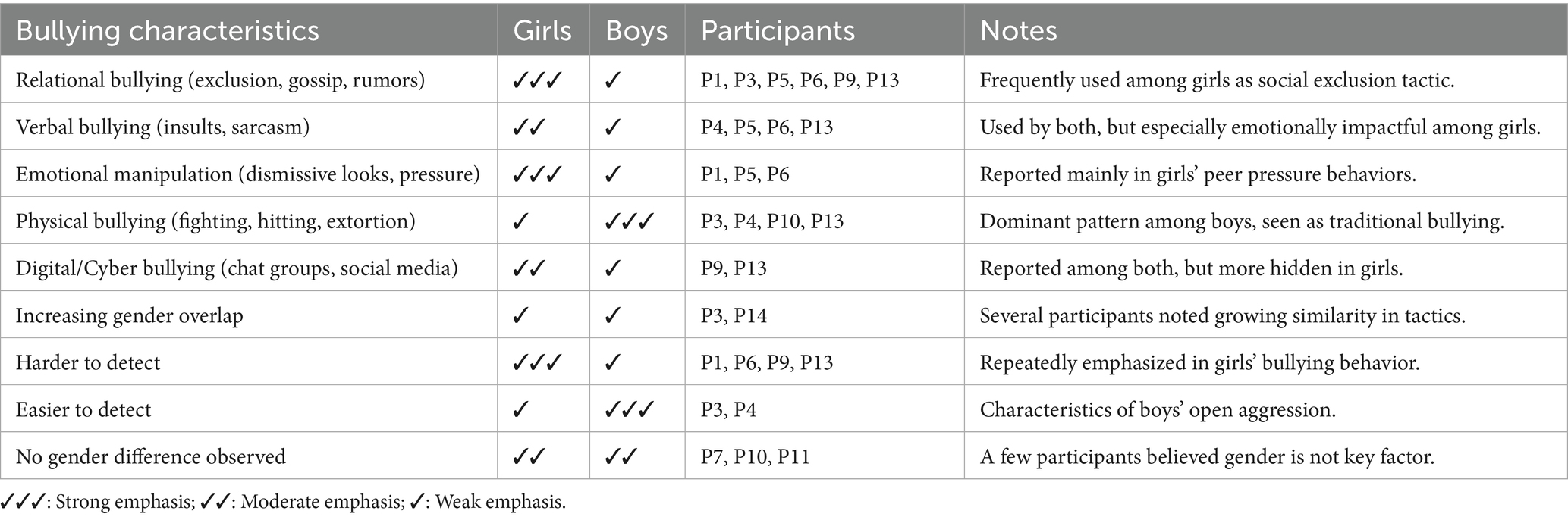

Participants widely agreed that bullying tends to manifest differently among boys and girls, with girls typically engaging in more covert, emotional, and relational forms of aggression, while boys often display overt and physical behavior. However, several teachers also noted that these traditional distinctions are becoming less pronounced over time. Table 4 shows bullying characteristics with participants.

4.4.1 Relational and emotional bullying among girls

A prominent view among participants was that bullying among girls is often subtle, emotionally intense, and psychologically damaging. One interviewee explained, “Bullying among girls can be more emotionally cruel compared to boys. While boys might engage in physical fights, girls tend to exclude others from their social groups, use sarcasm, or make belittling comments to lower someone’s self-esteem” (P5). This comment highlights how girls’ bullying often targets a peer’s sense of worth and belonging, leading to long-term emotional consequences rather than visible physical injuries. Another participant described the emotional tactics used: “Bullying among girls tends to be more emotional in nature. It often manifests as exclusion, dismissive looks, or social pressure within peer groups. Compared to boys, these forms of bullying are more subtle and harder to detect, yet their emotional impact can be much deeper” (P6). This statement draws attention to the sophisticated social strategies that girls may use to exert control or dominance, which makes adult detection more challenging.

4.4.2 Contrast with boys’ bullying patterns

In contrast, multiple participants emphasized that boys are more likely to engage in physical bullying. One teacher stated, “Among girls, bullying mostly takes the form of verbal attacks and exclusion. Among boys, it is more physical such as demanding money, hitting, or fighting” (P4), clearly differentiating the gendered patterns of aggression. Another added, “Usually, boys engage in physical bullying like fighting, while girls resort to social exclusion and gossip. However, nowadays, boys are becoming gossipier, and girls are becoming more physically aggressive, so the differences are decreasing” (P3). This evolving dynamic suggests that gender norms around bullying are shifting, potentially influenced by broader cultural or societal changes.

4.4.3 Difficulty in detection and intervention

Teachers noted that because of the hidden nature of girls’ bullying especially tactics like social exclusion, rumor-spreading, and emotional manipulation it can take much longer to identify and address. One participant reflected, “In the case of girls, it might take several months before the issue is noticed, often only when it escalates. Therefore, it’s crucial to engage girls in meaningful conversations and pay close attention to their behavior” (P1). This quote underscores the need for proactive engagement and attentive monitoring of girls’ social dynamics by participants. Another teacher elaborated on the specific tactics used: “Among girls, bullying tends to be more covert and indirect for example, spreading rumors, jealousy, exclusion from social groups, convincing others not to interact with someone, or removing someone from a chat group” (P9). These examples show how digital communication tools can amplify relational aggression, making it harder for school staff to monitor or intervene. The difficulty of detecting girls’ bullying is compounded by cultural expectations of modesty and silence, which discourage girls from reporting aggression. Teachers’ testimonies thus highlight not only the covert nature of relational bullying but also how cultural values intensify its invisibility.

4.4.4 Alternative views: no significant gender differences

While most participants observed gender-specific tendencies, a minority believed that bullying behavior depends more on individual temperament than gender. As one teacher remarked, “Whether a student is a boy or a girl, if they have inner aggression, they may become involved in bullying. That said, girls often express it more through words and social behavior” (P11). This nuanced perspective recognizes that gendered patterns exist, but not all students conform to them. Another participant noted, “I do not think there is a significant gender difference in bullying. Bullying is a harmful behavior and must always be condemned” (P10). This egalitarian stance reframes the issue by emphasizing the universal unacceptability of bullying rather than its gendered characteristics.

4.5 Theme fifth: understanding the roles of school staff in bullying prevention

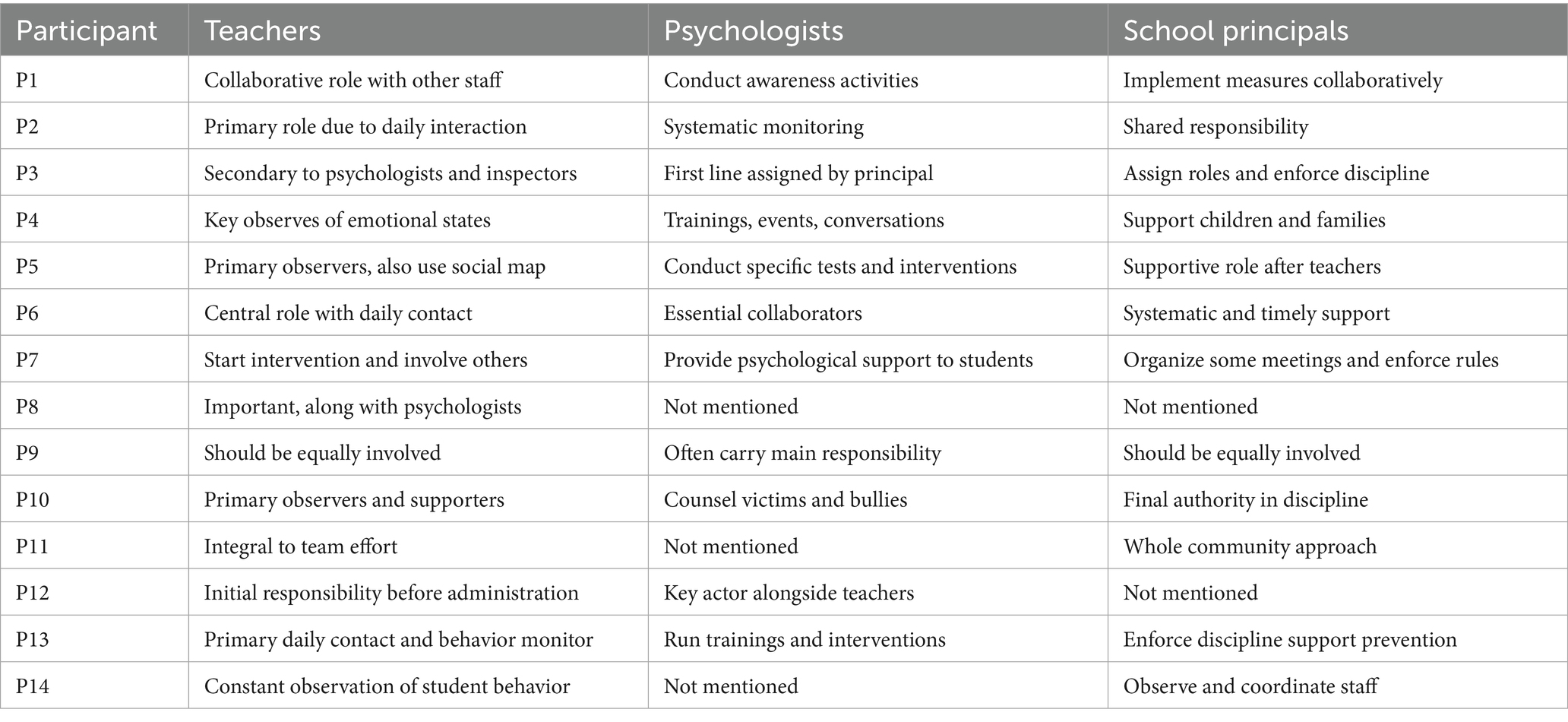

Participants consistently emphasized that preventing bullying is a shared responsibility that depends on collaboration between multiple stakeholders within the school community. Rather than attributing the responsibility to a single group, most participants described an interdependent system in which teachers, school psychologists, and administrators all play critical and complementary roles. Table 5 shows key roles of school staff in bullying prevention according to participant’s views.

Table 5 shows how participants perceive the distinct yet interconnected roles of teachers, psychologists, and school principals in preventing bullying. Teachers are consistently described as the primary observers and first responders due to their daily contact with students. Psychologists are recognized for providing targeted interventions and emotional support, though their role is occasionally underutilized or absent in some accounts. Principals are generally portrayed as supportive enforcers, responsible for discipline and coordination. The responses emphasize that collaboration across all roles is essential, though the degree of involvement and clarity of responsibility varies among schools.

4.5.1 The central role of teachers in daily observation and intervention

Many interviewees pointed to homeroom or class teachers as the frontline defenders against bullying. Their continuous interaction with students gives them unique insight into peer relationships, social dynamics, and sudden behavioral shifts. As one teacher explained, “The class teacher plays the most important role. They interact with students regularly greets them in the morning, sees them off after school, and works with them during breaks and class activities” (P5). This quote reflects a relational proximity that enables class teachers to notice subtle signs of social exclusion or emotional withdrawal before these issues escalate into more serious bullying cases. Participants also noted the importance of subject teachers, who can complement the work of class teachers by observing how students behave in different learning environments. “Subject teachers also play a crucial role, as they observe student participation and behavior during lessons” (P5). This points to a distributed model of vigilance, where all teaching staff are involved in creating a protective net around students.

4.5.2 Psychologists as specialists in emotional and Behavioral support

Participants frequently emphasized the key role of school psychologists, especially when bullying cases require deeper emotional insight, intervention, or therapy. “Psychologists conduct various trainings, events, and individual conversations with students” (P4), one participant stated, highlighting their capacity to address both the symptoms and root causes of bullying. Others described a more reactive approach: “At the school level, the administration first assigns psychologists and inspectors to work with the students. If bullying continues, the perpetrator’s parents are fined” (P3). While this reflects a more disciplinary perspective, it reinforces the psychologist’s central role as an early responder and behavior specialist. Still, one concern echoed by some teachers was the over-reliance on psychologists, which could inadvertently limit broader staff engagement. “Currently, the responsibility often falls solely on school psychologists. However, I believe all staff members teachers, administrators, and psychologists should be equally involved” (P9). This quote critiques the siloed model of prevention and calls for a more integrated approach across school roles.

4.5.3 School principals as policy enforcers and institutional leaders

School administrators were frequently mentioned as essential actors particularly when it comes to setting policies, enforcing rules, and supporting other professionals. One participant noted that administrators should “provide systematic and timely support for all staff involved in addressing bullying” (P6). This support is not limited to logistics or enforcement but includes cultivating a school climate in which anti-bullying efforts are prioritized. Other participants described how administrators help communicate consequences clearly: “At larger school meetings, administrators especially those responsible for discipline and student rights should explain the consequences of bullying… This makes students more conscious and encourages them to avoid such behavior” (P7). This strategic visibility helps reinforce a culture of accountability and awareness throughout the school.

4.5.4 A call for collective action

Most teachers ultimately viewed bullying prevention as a shared mission. As one put it plainly, “The entire school staff must work together. The student must be under constant observation” (P14). This quote reinforces the importance of daily vigilance and cross-role coordination. Another echoed the same collective spirit: “If everyone knows their role and acts as a team, we can prevent bullying” (P11). Such statements encapsulate the widespread belief that an effective anti-bullying framework must go beyond the efforts of isolated individuals. Although participants recognized collaboration as essential, their descriptions pointed to the absence of formalized structures for teamwork. This inconsistency mirrors broader national challenges: Kazakhstan has emphasized student well-being in policy rhetoric, yet lacks a standardized framework for inter-professional collaboration on bullying. This gap often leaves schools to rely on informal or ad hoc cooperation.

5 Discussion

This study explored teachers’, psychologists’ and school principals’ perceptions and actions related to preventing bullying among adolescent girls in schools in Kazakhstan. Our findings underscore the nuanced, relational nature of bullying among girls, emphasizing covert behaviors such as social exclusion, verbal aggression, and cyberbullying. These outcomes align with previous research, which consistently highlights that relational aggression and social exclusion are predominant forms of bullying among girls (Crick and Grotpeter, 1995; Smith, 2018). Teachers in our study identified these subtle bullying behaviors as difficult to detect, often remaining hidden until situations escalate significantly. This finding resonates with earlier studies, suggesting that covert bullying often poses challenges for timely detection and intervention by school staff (Cross et al., 2015).

A significant aspect of our findings pertains to teachers’ readiness to identify and respond to bullying. Teachers generally acknowledged gaps in their preparedness, particularly highlighting difficulties in recognizing indirect bullying forms like social exclusion and cyberbullying. This result mirrors findings from international studies, indicating that teachers often lack adequate training and confidence to effectively manage bullying, especially when dealing with less visible forms (Bauman and Del Rio, 2006; Yoon and Bauman, 2014). Specifically, in the context of Kazakhstan, our findings underline the importance of targeted professional development programs aimed at enhancing teachers’ skills in identifying and responding to subtle bullying behaviors.

The collaborative aspect of bullying prevention emerged strongly in our results. Participants emphasized the necessity of coordinated efforts involving teachers, school psychologists, and administrators to successfully manage bullying incidents. Similar to our findings, the literature emphasizes a comprehensive, school-wide approach as most effective in preventing bullying, with clearly defined roles and responsibilities (Olweus, 1993; Rigby, 2020). The involvement of school psychologists was frequently highlighted as critical, reflecting their specialized skills in emotional and psychological intervention. However, our study also revealed variability in the practical engagement of psychologists in different schools, indicating a potential area for policy-level improvement within Kazakhstan’s education system.

Regarding gender-specific bullying characteristics, our findings clearly indicate that bullying among adolescent girls tends to be predominantly relational and emotionally damaging. Teachers described the bullying behaviors among girls as socially manipulative and psychologically intense, aligning with international research on relational aggression (Underwood, 2003). However, some teachers reported increasing incidents of physical bullying among girls, suggesting shifts in traditional gender roles and behaviors that may require adjustments in intervention strategies.

In the broader Kazakhstani educational context, our findings suggest an urgent need for clearer policy guidelines and structured mechanisms for addressing bullying. Current practices vary considerably across schools, reflecting inconsistencies and gaps in the implementation of national policies. This scenario aligns with prior research in Kazakhstan, emphasizing the necessity of systemic changes, including standardized protocols and comprehensive teacher training programs for bullying prevention and intervention (Assylbekova et al., 2024).

The strength of our study lies in its rich qualitative insights, capturing authentic teacher experiences and perspectives across diverse school contexts. By centering teachers’ voices, we provided nuanced understanding of the practical realities faced in bullying prevention. However, our study is not without limitations. The sample size, while adequate for qualitative inquiry, limits generalizability. Furthermore, we relied solely on teachers’ self-reports, which could introduce subjective biases. Future studies could benefit from incorporating perspectives of students and parents, and employing observational methodologies to triangulate and enhance the reliability of findings.

6 Conclusions and recommendations

This study examined the perceptions and actions of teachers, psychologists, and school principals regarding the prevention of bullying among adolescent girls in Kazakhstani schools. The findings indicate that bullying among girls is predominantly relational and covert, expressed through exclusion, gossip, and cyberbullying. These subtle forms of aggression are often overlooked by educators and remain difficult to address within the existing school framework. Teachers expressed varying levels of preparedness, with some adopting proactive strategies while others felt constrained by a lack of institutional support. Psychologists and principals were identified as essential actors, yet their involvement was uneven and often dependent on individual initiative rather than systematic structures. Such variation reflects broader policy gaps and highlights the urgent need for clearer national guidelines, consistent training, and school-wide mechanisms that promote collaborative action.

To strengthen bullying prevention in Kazakhstan, policymakers should look to internationally validated models such as the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program and Finland’s KiVa Program, both of which emphasize whole-school engagement, staff training, and the integration of parents and students in prevention efforts. While these models provide effective frameworks, they must be adapted to Kazakhstan’s unique cultural and social realities. Norms related to modesty, honor, and collectivism shape how students experience and report bullying, meaning that interventions must be culturally sensitive to resonate with local contexts. For example, awareness-raising activities should incorporate community values and address the role of cultural shame in silencing victims, while training programs must equip educators to recognize both overt and covert forms of bullying in ways that reflect Kazakhstan’s educational traditions and centralized governance.

Another key implication of this study is the necessity of broader stakeholder involvement. While teachers, psychologists, and principals remain at the forefront of prevention, meaningful progress requires active participation from students and parents. Structured opportunities for parent workshops, peer mediation activities, and student-led initiatives can extend prevention beyond classroom walls and cultivate a culture of shared responsibility. Ensuring that school psychologists have manageable caseloads and institutional authority, and that principals embed collaborative practices into school policy, will also be essential for sustaining whole-school approaches.

At the same time, this study is limited by its small sample size, single-city focus, and reliance solely on the perspectives of education professionals. The absence of direct input from students and parents constrains the comprehensiveness of the findings and points to the need for future research that integrates multiple voices and school contexts. Longitudinal and comparative studies across regions of Kazakhstan would further illuminate how national reforms translate into practice. By combining internationally tested frameworks with sensitivity to Kazakhstan’s cultural environment and systemic challenges, schools can move toward more coherent and sustainable approaches to preventing bullying and ensuring the well-being of all students.

Author contributions

MT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Translation to English and language-fluency control.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Assylbekova, M., Saikhymuratova, I., Atmaca, T., Somzhurek, B., and Slambekova, T. S. (2024). Hidden wounds: unveiling the impact of social ostracism and bullying in university life (comparison of Kazakhstan and Türkiye). Cogent Educ. 11:2434774. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2024.2434774

Ayhan, N., Akman, E., and Narmamatova, T. (2025). Digital transformation and cyberbullying in education: an evaluation on children in Kyrgyzstan. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 30:8058. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2025.2498058

Bauman, S., and Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers’ responses to bullying scenarios: comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 219–231. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.219

Bocanegra, J., Rossen, E., and Grapin, S. L. (2017). Factors associated with graduate students’ decisions to enter school psychology. Research Reports. 2, 1–10.

Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). Translating research to practice in bullying prevention. Am. Psychol. 70, 322–332. doi: 10.1037/a0039114

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., O’Brennan, L. M., and Gulemetova, M. (2013). Teachers’ and education support professionals’ perspectives on bullying and prevention: findings from a national education association study. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 42, 280–297.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Craig, W., Pepler, D., and Blais, J. (2007). Responding to bullying: what works? Sch. Psychol. Int. 28, 465–477. doi: 10.1177/0143034307084136

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE.

Crick, N. R., and Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 66, 710–722. doi: 10.2307/1131945

Cross, D., Lester, L., and Barnes, A. (2015). A longitudinal study of the social and emotional predictors and consequences of cyber and traditional bullying victimisation. Int. J. Public Health 60, 207–217. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0655-1

Dedousis-Wallace, A., Shute, R., Varlow, M., Murrihy, R., and Kidman, T. (2013). Predictors of teacher intervention in indirect bullying at school and outcome of a professional development presentation for teachers. Educ. Psychol. 34, 862–875. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.785385

Duisenova, S. M., and Kylyshbayeva, B. N. (2016). Educational strategies of Kazakhstan Universities graduates. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6, 71–76.

Espelage, D. L., Basile, K. C., and Hamburger, M. E. (2012). Bullying perpetration and subsequent sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. J. Adolesc. Health 50, 60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.015

González-Alonso, F., Guillén-Gámez, F. D., and de Castro-Hernández, R. M. (2020). Methodological analysis of the effect of an anti-bullying programme in secondary education through communicative competence: a pre-test–post-test study with a control-experimental group. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:3047. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093047

Herkama, S., Kontio, M., Sainio, M., Turunen, T., Poskiparta, E., and Salmivalli, C. (2022). Facilitators and barriers to the sustainability of a school-based bullying prevention program. Prev. Sci. 23, 954–968. doi: 10.1007/s11121-022-01368-2

Hong, J. S., and Espelage, D. L. (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003

Kärnä, A., Voeten, M., Little, T. D., Poskiparta, E., Kaljonen, A., and Salmivalli, C. A. (2011). Large-scale evaluation of the KiVa antibullying program: grades 4-6. Child Dev. 82, 311–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01557.x

Katsikas, A., and Thanos, T. (2025). Factors contributing to the manifestation of school bullying: school principals’ perspectives. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 1-18, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2025.2475293

Kenny, N., McCoy, S., and O’Higgins Norman, J. (2023). A whole education approach to inclusive education: an integrated model to guide planning, policy, and provision. Educ. Sci. 13:959. doi: 10.3390/educsci13090959

Koptleuova, D. (2023). The effects of verbal school bullying on the academic performance of teenage victims in Kazakhstan: the necessary support for victims. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/dnzy9

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Mishna, F., Scarcello, I., Pepler, D., and Wiener, J. (2005). Teachers’ understanding of bullying. Can. J. Educ./Rev. Can. Educ. 28, 718–738. doi: 10.2307/4126452

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., and Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth. JAMA 285, 2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094

O’Brien, S. O., Campbell, M. A., and Whiteford, C. (2024). Exploring the role of school psychologists/counsellors in addressing bullying: current practices and suggested future directions. J. Psychol. Couns. Schools 34, 388–398. doi: 10.1177/20556365241295299

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do? Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Rigby, K. (2020). How teachers deal with cases of bullying at school: what victims say. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:2338. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072338

Swearer, S. M., Espelage, D. L., Vaillancourt, T., and Hymel, S. (2010). What can be done about school bullying? Linking research to educational practice. Educ. Res. 39, 38–47. doi: 10.3102/0013189X09357622

Swearer, S. M., and Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. Am. Psychol. 70, 344–353. doi: 10.1037/a0038929

Tokunaga, R. S. (2010). Following you home from school: a critical review of cyberbullying research. Comput. Human Behav. 26, 277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014

Ttofi, M. M., and Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs. J. Exp. Criminol. 7, 27–56. doi: 10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

UNESCO (2019). Behind the numbers: Ending school violence and bullying. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

van Aalst, D. A., Huitsing, G., and Veenstra, R. (2024). A systematic review on primary school teachers’ characteristics and behaviors in identifying, preventing, and reducing bullying. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 6, 124–137. doi: 10.1007/s42380-022-00145-7

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., and Nansel, T. R. (2009). Relational bullying among adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 45, 368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021

Waseem, M., and Nickerson, A. B. (2024). Bullying: issues and challenges in prevention and intervention. Curr. Psychol. 43, 9270–9279. doi: 10.1007/s12144-023-05083-1

Keywords: bullying prevention, adolescent girls, Kazakhstan, school collaboration, school climate

Citation: Tulenbaevna MM, Atmaca T, Tursynkyzy AK, Mamadaliyev S and Zholdasovna KZ (2025) Collaborative roles in schoolwide bullying prevention: teachers’, psychologists’, and school principals’ shared responsibilities. Front. Educ. 10:1677350. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1677350

Edited by:

Michelle Finestone, University of Pretoria, South AfricaReviewed by:

Sadaruddin Sadaruddin, Universitas Islam Makassar, IndonesiaIrma Prasetyowati, University of Jember, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Tulenbaevna, Atmaca, Tursynkyzy, Mamadaliyev and Zholdasovna. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Atemova Khalipa Tursynkyzy, a2FsaXBhdGVtb3ZhYUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Myrzapeissova Meruyert Tulenbaevna1

Myrzapeissova Meruyert Tulenbaevna1 Taner Atmaca

Taner Atmaca