- Department of Arabic Language and Media, Faculty of Arts and Education, Arab American University-Palestine, Jenin, Palestine

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming journalism and media education, yet little is known about how conflict-affected, resource-constrained systems can adapt. This study addresses this gap by assessing the pedagogical and institutional readiness of Palestinian universities to integrate AI into journalism curricula, responding to the ethical and technological imperatives of the Fifth Industrial Revolution and drawing on institutional theory and decolonial AI perspectives. Using a convergent mixed-methods design, data were collected through a survey administered to 221 media students and interviews conducted with 36 faculty experts across nine West Bank universities. Quantitative results revealed moderate satisfaction, persistent infrastructure gaps, and a full mediation effect, whereby faculty readiness explained the link between infrastructure adequacy and student satisfaction, with students prioritizing AI ethics (82 percent), fake news detection, and newsroom automation, indicating a demand for critical and responsible AI education. Qualitative analysis identified seven themes, including epistemic disruption, interdisciplinary convergence, ethical reflexivity, and critical localism, reflecting calls for context-grounded curricular reform as experts rejected imported models in favour of programs rooted in local identity, justice, and sociopolitical context. Overall, the study proposes a triadic reform framework comprising epistemic reconfiguration, ethical anchoring, and pedagogical adaptability, extending institutional theory and decolonial AI discourse while offering a culturally responsive roadmap for AI curriculum reform in fragile academic systems, and calling for coordinated action among universities, ministries, and global partners to build inclusive, adaptive, and justice-centered AI literacy in media education.

1 Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is seen as the pivotal breakthrough technology of the current century, which has changed the way industries, governments, communication, and education systems operate globally (Katsamakas et al., 2024). By improved natural language processing (NLP), machine learning (ML), and automated content generation, AI is a welcome increment in productivity and creativity but still human labor, agency, and cognition have to be radically reshaped (Li et al., 2025). Therefore, higher education is experiencing a paradigmatic shift, particularly in such areas as journalism, communication, and media studies where technological convergence is resulting in the redefinition of professional roles, ethical frameworks, and pedagogical expectations (Tlili et al., 2021).

Still, these worldwide innovations cover up the differences that still exist between regions that have well-functioning innovation ecosystems and those that are structurally weak. For example, in areas affected by conflict and suffering from lack of resources such as Palestine, universities have difficulties in implementing changes in education caused by AI because they have limited infrastructure, fragmented policies, and poor access to digital tools (Al-Khatib and Shraim, 2023). Hence, figuring out ways in which AI can be used in an ethical and proper manner in Palestinian media education is not only a teaching requirement but also a priority for the country’s development.

The Fifth Industrial Revolution that the world is moving into is characterized by the close integration of human values with sophisticated AI systems. Therefore, educational institutions are expected not only to carry on their traditional role of knowledge providing but also to operate as innovation ecosystems (World Economic Forum, 2025). To be up to this challenge it is not enough to be technically skilled; it is a question of radically changing curricula to develop three essential competencies:

AI literacy involves the skills to create, effectively utilize, and critically evaluate AI tools. Ethical judgment refers to being aware of the bias in AI results, the transparency of algorithmic processes, and trustworthiness of the media. Interdisciplinary fluency refers to the integration of the technical, social, and communicative aspects of the expertise into the unified educational practices (OECD-EU, 2025).

The central problem of this study lies in the absence of a localized, contextually grounded framework for AI curriculum integration within Palestinian universities. While numerous institutions worldwide have already started to integrate AI in their media and journalism education, only a handful have considered how such integration could align with the local identity, ethical principles, and institutional realities of fragile higher education systems. This study offers a culturally sensitive and theoretically informed framework for the use of AI in media curricula in Palestine.

The necessity for such a radical change in teaching methods is evident from recent empirical studies. Apart from that, the GenAI Literacy Assessment Test (GLAT) revealed a considerable difference between students’ self-assessment of skills and their actual skills, thus indicating an immediate need for standardized and scalable AI readiness assessments in higher education (Splawa-Neyman, 2025). In addition, the study proposes that introducing large language models (LLMs) in the assessment system can serve as a means to change the traditional instructional methods to correspond to the new cognitive demands that focus on creativity and skills (Siddig, 2025).

In addition, as AI changes the way humans think, the three aspects being reflection, reasoning, and creative production, need curriculum models that not only memorize but also encourage metacognition, problem-solving, and original creation (Singh et al., 2025). This is particularly the case in the creative fields of journalism and media studies, where the rise of algorithmic content generation has, among other things, questioned the issues of authorship, originality, and editorial governance, which were considered as obvious before (Hsu, 2025). Existing educational models are frequently reported by research to be technologically dated; hence journalism education must still coevolve with AI’s expanding capabilities and accompanying ethical issues in order to be still relevant (Criddle and Jack, 2025).

Based on the researcher’s professional involvement with Palestinian media faculties and curriculum development, this research uses institutional theory as a main framework to explain how organizational norms, resources, and cognitive structures affect AI adoption. Along with a mixed-methods design, it also employs decolonial perspectives to be certain that AI curriculum reform in Palestine is not only about technological competence but also matters of epistemic justice and cultural authenticity.

2 Literature review

One of the main changes brought about by Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the transformation of both education and journalism. As a result, new initiatives demanding the development of AI literacy and its curriculum integration are appearing. To a great extent, instruments such as the OECD-EU AI Literacy Framework and Bloom’s Taxonomy serve to clarify the four domains Engage, Create, Manage, and Design as the levels of digital competence in higher education institutions. Normally, these models rely on the assumption of infrastructural stability and institutional alignment, whereas in scenarios of fragility and conflict, this might not be true. Tlili et al. (2021) warned that universal models should not be applied locally without adjustment, especially when the educational environment is systemically fragile as it is in Palestine.

Consequently, the recent regional research takes a side on the issue and points to the same limit. El-Ghetany (2024) studied AI and the education of journalism staff in universities of the Arab world and concluded that even though institutions in the region are progressively recognizing the necessity of an AI-driven curriculum in media, the execution is still at a very early stage due to factors such as lack of training for the staff, uneven infrastructure, and the absence of a unified curriculum standard. This seminar also stressed that Arab universities should make it their priority to implement AI in journalism education through locally tailored, ethically grounded approaches so as not to legitimize the Western models that are not suitable for regional realities.

Supporting this requirement for cultural adjustment, Splawa-Neyman (2025) created the Generative AI Literacy Assessment Test (GLAT) that measures proficiency in generative AI and still awaits validation for a non-Western education setting. To illustrate, Al-Batta et al. (2024) reported that while 87% of Palestinian nursing students had utilized generative AI tools, 91% of them had never been formally trained, thus unveiling a crucial gap between literacy and performance. The gap between high usage and low institutional instruction most likely applies to media students as well, who are increasingly using AI tools in an informal way but are not supported by formal curricula.

Based on-the-spot research in Palestine has unveiled a trend of raising curiosity and interest toward Artificial Intelligence-focused teaching methods. Omar et al. (2024) voiced that most of the faculty members in Palestine are optimistic about AI adoption in the educational sector but at the same time they complained about hurdles like poor digital infrastructure and lack of well-defined institutional policies. As a follow-up, the 2025 Birzeit University workshop titled “AI Ethics in Journalism Teaching” committed itself to the challenge by recognizing that faculty members need to be provided with hands-on, accountable, and transparent frameworks for the integration of journalism algorithmic sources. These two sets of evidence lead to the conclusion that local Palestinian academic institutions are getting closer to conceptual and theoretical approaches and more to practical and context-driven ones in terms of media literacy and AI.

The level necessary to ensure that a faculty is ready for the imperative of an AI-instructional culture is faculty preparedness itself. The TPACK framework of Mishra and Koehler (2006) is probably the most representative model in understanding the nuances of teaching with digital means, by stressing a depiction of how technology, pedagogy, and content knowledge interact with each other. Singh et al. (2025) cognitive scaffolding model goes further by showing how AI can be a tool to improve reflective reasoning and creative thinking. However, different institutions have different levels of capability to bring these model-based applications to life. According to Khalil and Belal (2023), in Palestine, the research shows that there are considerable disparities in the digital confidence and professional development of the teaching staff. Abdel Ghani et al. (2024) describe this trend in Palestine and say that the same is happening in Saudi Arabia, Al-Hindi (2022) also reported the situation in Egypt. While the TPACK framework is very instrumental at the theoretical level, it is still far from being deeply embedded in national policy and university curriculum across the Arab region.

Corresponding studies of different but similar settings have been a major source of evidence in support of these claims. Şen (2025) reviewed the curricula of journalism education in universities in Turkey and observed that integration of AI in a local level was mostly a theoretical issue, with the main focus being on ethical aspects and awareness of algorithms, while the lab-based courses like data journalism or AI-powered production were very few. There was a significant difference in this imbalance especially between public and private universities, which unveiled the manner in which infrastructural resource inequalities influence the implementation of curriculum. In like manner, research in Jordan has revealed that media students have strong behavioral and cognitive motivations to use AI tools in the creation of visuals, audio, and text, but at the same time, there is a lack of local frameworks for institutions to facilitate such practices (Omar et al., 2024). Taken together, these publications illustrate an emerging consensus in the region about the necessity of practical, locally relevant AI education in the media area.

TPACK is more about the technology side. What about TAM? It examines the adoption from the user’s perspective: How useful is the thing, how easy it is, and finally their behavior toward acceptance. As Peláez-Sánchez et al. (2024) emphasize, even the best pedagogical potential will not be implemented if there is system unreliability or if teachers feel that there is no institutional support. In environments where resources are limited, these perceptual barriers usually dominate over the technical ones, thus it is much more valuable to make trust-building efforts alongside doing the work on the infrastructure.

The need for a flexible pedagogical approach is even more urgent in crisis zones. Crisis pedagogy, as per Veletsianos and Houlden (2020), revolves around relationality, hybrid delivery, and curriculum adaptation. Salem and Ayyash (2024) present the situation of the model being used in the Gaza Strip as an example, where AI deployment and delivery had to switch to offline mode due to low-bandwidth considerations. So, these examples show that AI implementation should not be considered only as a technical problem that needs a solution; rather, they should be treated as a relational and pedagogical process that is influenced by the context and crisis. This AI-led change in journalism outside of the traditional educational sector is causing the rise of ethical, epistemological, and labor-related issues, which Brennen et al. (2020) refer to as techno-skepticism. They define technoschauvinism as the blind and uncritical glorification of automation over human judgment, a stance that may result in editorial values being neglected. Siddig (2025), however, is in favor of the augmentation collaborative model where AI is a collaborator and not a replacement in newsrooms. Concurrently, Papamitsiou et al. (2022) support the incorporation of responsible AI frameworks in journalism and media education that focus on the issues of transparency, human oversight, and epistemic justice.

Policy bodies have already started to react to these ethical challenges by setting new standards for classrooms and newsrooms. UNESCO, 2023’s (2023, 2025) Guidance on Generative AI in Education and Research outlines the responsibilities of institutions concerning the training of teachers, the integrity of the assessment, and the governance of data, which are all essential dimensions for curriculum designers in journalism and communication programs. Similarly, the Porlezza and Schapals (2024) study has taken a step forward in the direction of journalism ethics in academic contexts by implementing clear regulations that limit the publishing of AI-generated content without human review, thus providing a practical reference for journalism ethics teaching.

Though these groundbreaking models are available, feeble media systems fail to give them a proper response. García-López and Trujillo-Liñán (2024) argue that AI ethical and regulatory frameworks in education are generally ill-equipped to monitor enforcement in developing contexts, which increases the risk of misinformation and digital colonialism. Their systematic review offers ample information that supports the worries raised by Papamitsiou et al. (2022) and other researchers that bias in algorithms and deepfakes exacerbate the instability of the environment in those areas that are less equipped with media literacy infrastructure. The level of AI readiness in higher education is substantially different across the Arab world. Alotaibi and Alshehri (2023) is of the opinion that a rapid AI adoption process can be expected in the Gulf as a result of top-down investments and infrastructure. On the other hand, Boumediene (2023) and Bukhari (2023) convey the message that the Maghreb is still going through a phase of stagnation where the old policy frameworks and lack of ethical oversight are the reasons that innovation is being slowed down. Emirtekin (2025) reflects the similar pattern, he says that AI-driven automated assessment systems are, for the most part, not in harmony with local pedagogical values or governance structures.

The introduction of AI in Palestine is mainly through informal channels. Al-Khatib and Shraim (2023) reveal that the absence of a national AI policy, lack of proper infrastructure, and insufficient faculty training are some of the factors that impede the formal adoption of AI. Nevertheless, a few institutions are still experiencing an era of innovation. Unpublished internal documents from An-Najah University (2023) show that there was a substantial change in the mood of the faculty toward AI, as well as an increase in participation of students, hence it can be deduced that a culture of experimentation is gradually getting established that is still a little bit unstable. The variations signify differentiated policy strategies that consider the local capabilities and the innovation ecosystems. Moreover, the interaction of AI with human cognition and creativity in journalism education is the subject of a new definition. Hsu (2025) states that generative AI not only automates content production but also changes the cognitive and creative processes that are the basis of journalistic inquiry. This view, when combined with Buisson’s scaffolding theory, calls for curricula that equip students with the technical skills as well as the ability to think critically and reflect. However, Papamitsiou et al. (2022) point out that the majority of media programs in difficult regions still follow a linear, outdated pedagogy that does not equip students with the necessary skills for algorithmic media ecosystems.

One of the aspects pointed out by emerging critiques is the colonial epistemologies that are still dominant in AI systems used worldwide. Al Jazeera’s investigative reporting (2023) and decolonial theorists’ scholarship highlight the fact that most of AI systems developed in the West tend to exclude non-Western ways of knowledge, languages, and cultural expressions. To ensure the ethical design of AI, Papamitsiou et al. (2022) emphasize the need for AI to be based on epistemic pluralism and to allow for algorithmic accountability in local communities. The situation in Palestine, where journalism and media production are not only the tools of resistance but also become the means of surveillance, is such that these issues are not a matter of academic debate, rather they are the necessities of the civics.

While there is increasing attention to the pedagogical and ethical use of AI, very few of them have acknowledged the challenges that such applications may face in an environment affected by conflict and lack of resources. Through a conceptual framework, this work, as a research, attempts to fill that void by integrating aspects of institutional readiness, decolonial ethics, and crisis-responsive pedagogy. The research of Joudi (2024) and Abdel Ghani et al. (2024) reveal how the curricula have been fragmented due to the factors at play in the region; however, this paper goes beyond that by investigating the possibility of structural fragility being balanced by situationally-responsive innovation and critical pedagogy.

To put it simply, the reviewed materials point to a three-pronged model for curriculum change: firstly, rethought from an epistemological viewpoint (via TPACK, AI literacy, decolonial critique); secondly, morally grounded (this can be achieved through AI design that is responsible and transparent); and thirdly, pedagogically flexible (the use of crisis-trained strategies). The amalgamation thus formed offers a principal platform for the onward AI-informed journalism curricula development meant for locales where digital progress has to contend with the limitations of the existing structures, the complexity of ethics, and geopolitical instability.

The bulk of regional and global literature, which is progressively becoming more extensive, basically leads to three major insights that are of great importance for this study: (1) The need for the implementation of a practice-based AI learning approach in Arab media programs is very strong, however, the curricular responses are still disjointed; (2) the ability and administration of the institution—rather than the technology - are what ultimately lead to the successful adoption; and (3) the presence of morally sound frameworks like the UNESCO’s standards gives real examples that Palestinian universities can modify to localize culturally and professionally appropriate AI education.

3 Methodology

The research utilizes a Convergent Parallel Mixed-Methods Design that combines both quantitative and qualitative methods to examine how prepared the Palestinian media education systems are for the implementation of artificial intelligence (AI). The quantitative part of the study was based on a structured questionnaire that was given to media students, while the qualitative part of the study consisted of semi-structured interviews with academic experts of media and communication faculties in Palestinian universities in the West Bank. Such a design allowed the simultaneous gathering and analysis of student perceptions and institutional assessments, thus enabling triangulation and deepening the interpretive level of the results. The convergent design helped a lot in matching the numerical trends of student satisfaction with the rich thematic depth of the expert narratives.

Institutional theory was the main analytical lens that informed both the quantitative and qualitative parts of the study. As part of the student questionnaire development, institutional theory was used to guide the operationalization of infrastructure adequacy, faculty readiness, and student satisfaction that are the three pillars of institutional environments, i.e., regulative, normative, and cognitive (Scott, 2014). Every survey item was intended to reflect one or more of these aspects, thus linking the institutional framework to individual perceptions. In addition, the qualitative phase was also aligned with institutional logics theory as the interview framework and coding framework highlighted the ways in which organizational norms, governance structures, and cultural-cognitive beliefs influence curriculum reform processes. The code labels such as “bureaucratic inertia,” “policy rigidity,” and “faculty autonomy” were essentially the institutional constructs from which the authors of the paper drew and further refined during axial coding to reflect their relational dynamics in Palestinian higher education. The alignment made it possible for Institutional Theory to be the organizing principle that led the researchers through the stages of sampling, data collection, and analysis rather than just being a conceptual background.

The study was carried out in all nine accredited Palestinian universities in the West Bank that offer bachelor’s or master’s degree programs in media and communication. These universities were chosen to guarantee not only a wide geographic representation (northern, central, and southern regions) but also a difference in the type of institutions (governmental, semi-governmental, private, and national). The overall number of students in the field of media in these universities is around 2,345 people.

Sampling Procedures. The research resorted to two different methods of sample selection that were used for each part of the design.

• Quantitative sampling: 221 students filled out the questionnaire between July 6 and 12, 2025. The sampling frame included the two most likely sources of the students, whom are the media and journalism students from the 9 universities. To select the candidates for the survey, a random simple-probability method was used so that any of the students can be part of the survey with the same chance. The number of people required for the sample was figured out through Cochran’s formula (n = Z2 pq/e2) at a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error which resulted in a minimum of 210 respondents. To take care of the situation when some of the respondents may not answer, 10% more was added and thus, the final n = 221. Besides the official email lists and faculty announcements, recruitment also took place in the WhatsApp and Facebook groups where interested students could get more information and instructions about the process. The respondents must meet the condition of being full-time undergraduate students, who have completed at least one media-technology or AI-related subject.

• Qualitative sampling: 36 academic experts of various backgrounds and experiences were purposively selected and interviewed between June 21 and 30, 2025. A maximum-variation purposive sampling approach was used to ensure diversity in rank, discipline, and type of institution. The inclusion criteria were the acquisition of a postgraduate degree (MA or PhD), experience of at least 5 years in teaching or professional work in media or AI-related fields, and involvement in curriculum development or departmental policy committees. By this purposeful variation, representativeness and theoretical saturation, which are in line with the institutional-theory focus of multi-level perspectives (organizational and individual), were enhanced. Besides the institutional theory, the mixed-methods design also represented a multi-level logic of analysis. Quantitative indicators show institutional edifices and formalized routines (e.g., infrastructure adequacy), while qualitative data reveal normative and cultural-cognitive mechanisms such as values, professional norms, and faculty agency. The design gave the researcher an opportunity to fathom how the interplay of systemic constraints and individual attitudes as well as institutional culture could affect AI curriculum readiness.

Data collection encompassed two complementary procedures. In the first place, a structured questionnaire was disseminated online through Google Forms among media students. The questionnaire included Likert-scale items evaluating satisfaction, faculty readiness, and infrastructure adequacy; binary indicators reflecting perceived curricular challenges; and a checklist recognizing AI localization priorities. Anonymity and voluntariness characterized the participation. To assure the dependability (Cronbach’s α = 0.84) and the understandability of the items, a pilot test with 20 students was made; after the expert support of two senior methodologists, minor wording revisions were done.

As a complement, semi-structured interviews were held with academic experts. The interviews, consented to by the participants, were done either face-to-face or remotely via Zoom, WhatsApp, or telephone. The average time of each meeting was between 40 and 60 min, and the discussion followed a seven-thematic protocol: curricular design, infrastructure, faculty development, ethics, governance, localization barriers, and AI policy. Field notes and audio recordings were among the methods used to record the sessions and, therefore, ensure the contextual accuracy.

Data from a survey were saved from Microsoft Forms and analyzed using SPSS v29, JASP, and AMOS/R (lavaan) to carry out a detailed statistical investigation, including structural equation modeling. The first screening revealed that there were less than 5% of missing data for each item, which were handled by multiple imputation with listwise deletion for the sensitivity checks. Reliability was in a comprehensive manner Cronbach’s α for the Likert-based scales and KR-20 for the binary items. Construct validity was the measurement by both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Description of the statistics was extended by the inclusion of central tendency, dispersion, and distribution shape measures, while norms of normality and homogeneity were tested through Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. The inferential analyses were supplemented by Spearman’s correlations, multiple regression, Welch’s ANOVA with Games–Howell post-hoc tests, and SEM with WLSMV estimation to test a mediation model relating infrastructure, faculty readiness, and satisfaction. Effect sizes and confidence intervals were presented throughout the study, and each model was subjected to robustness checks, with post hoc power analysis showing high statistical sensitivity (1–β > 0.95).

The interview transcripts were examined with MAXQDA 24, in line with Braun and Clarke’s (2006) reflexive thematic analysis framework. Open coding was independently performed by two researchers, with inter-coder reliability of κ = 0.82 on 20% of the transcripts. The 214 codes were merged into 42 axial categories, from which seven dominant themes were inductively derived. These themes include:

Interview 31 was the point at which thematic saturation was achieved, with no new codes being identified thereafter. An audit trail was used to record coding decisions, and member checking with five participants was employed to confirm the accuracy of the interpretation.

An initial inspection of the instruments was carried out by a panel of four university scholars specializing in digital media and communication sciences. Minor changes were made after a detailed review of the items in the questionnaires to clarify and make the items more relevant. To confirm the theoretical validity, EFA and CFA were used to ascertain that each Likert scale represented a different latent variable with good model fit indices (e.g., CFI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.06).

The research used a descriptive-analytical methodology based on a multiple case study design, which allowed an in-depth study of the implementation of AI in the media education sector. The quantitative part made it possible to assess the experiences of students and the readiness of institutions, while the qualitative part provided the elites’ view of the systemic, infrastructural, and epistemological aspects. These methods combined to provide a comprehensive, locally grounded understanding of the issues, priorities, and practical solutions for AI-responsive curriculum reform in Palestinian media faculties (Khlouf, 2024; Assaf Dima, 2020).

4 Results

4.1 Quantitative findings

Survey data were initially collected through Microsoft Forms and later processed using SPSS v29, JASP, and AMOS/R (lavaan) to create a single statistical model with structural equation modeling that represents the data from various statistical techniques and tests. At first, the screening revealed that the missing data accounted for less than 5% of each item, and hence, multiple imputations with listwise deletions for sensitivity checks were used to deal with them. Reliability was also measured through Cronbach’s a for scales based on the Likert method and KR-20 for binary items. Validity of constructs was measured through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Descriptive statistics were supported by characteristics of central tendency, dispersion, and distribution shape, while signs of normality and homogeneity were tested by Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests correspondingly. The inferential analyses included the Spearman’s correlations, multiple regression, Welch’s ANOVA with Games-Howell post hoc tests, and SEM with WLSMV estimation for testing a mediation model that links infrastructure, faculty readiness, and satisfaction. Throughout the study, effect sizes and confidence intervals were reported, and all models underwent robustness checks. There was post hoc power analysis to confirm that the study was statistically sensitive (1-β > 0.95).

4.1.1 Objective 1: descriptive statistics overview

The student survey preliminary analysis (N = 221) provided evidence of moderate perception levels of AI integration in media programs at Palestinian universities. Main variables were evaluated on a 3-point Likert-type scale (1 = Low, 2 = Moderate, 3 = High), and the descriptive results were represented in Table 1.

• Satisfaction with AI-related curricular efforts yielded a mean of M = 2.17, SD = 0.83, suggesting that students perceived institutional efforts as moderately developed.

• Faculty readiness scored higher, M = 2.84, SD = 0.91, indicating that students generally viewed their instructors as moderately to well-prepared for AI integration.

• Infrastructure adequacy averaged M = 2.26, SD = 0.76, reflecting somewhat limited but developing technical readiness (e.g., lab and equipment support).

• Challenge scores, which were based on four binary indicators (range = 0–4), averaged M = 2.43, SD = 1.02, and thus pointed to a fairly high level of AI-related barriers that were most commonly faculty resistance, ethical concerns, and lack of skills.

Psychometric testing with the Shapiro-Wilk method showed that all continuous variables had significant deviations from normal distribution (p < 0.01). Nevertheless, the values for skewness and kurtosis were still within the permissible limits (| skew| < 1.0, | kurtosis| < 1.5), thus allowing for the use of non-parametric methods in the occurrence of such cases.

4.1.2 Demographic characteristics

• Gender distribution: 58% female, 42% male

• Academic level: first-year (18%), second-year (21%), third-year (24%), fourth-year (22%), postgraduate (15%)

• University type: public (45%), private (48%), non-profit (6%), national (1%).

Figure 1 visually represents the average scores of three main institutional factors that were used to gauge student perceptions: AI curricula satisfaction, faculty readiness, and infrastructure adequacy. According to Figure 1, the faculty readiness was rated the highest by students (M = 2.84), followed by infrastructure adequacy (M = 2.26) and curriculum satisfaction (M = 2.17). The pattern here indicates that students see their teachers as somewhat competent in AI integration, but they are less confident in the quality of institutional support and the curricula. These impressions reflect the earlier qualitative data that point to an unequal distribution of resources and the absence of formal training structures.

Figure 1. Mean scores of student-rated institutional metrics (N = 221). Values reflect responses on a 3-point Likert scale (1 = Low, 3 = High).

4.1.3 Objective 2: predictor of faculty readiness

A simple linear regression was used to evaluate if students’ views of the sufficiency of the infrastructure could significantly forecast their views of the faculty readiness to integrate AI into journalism curricula.

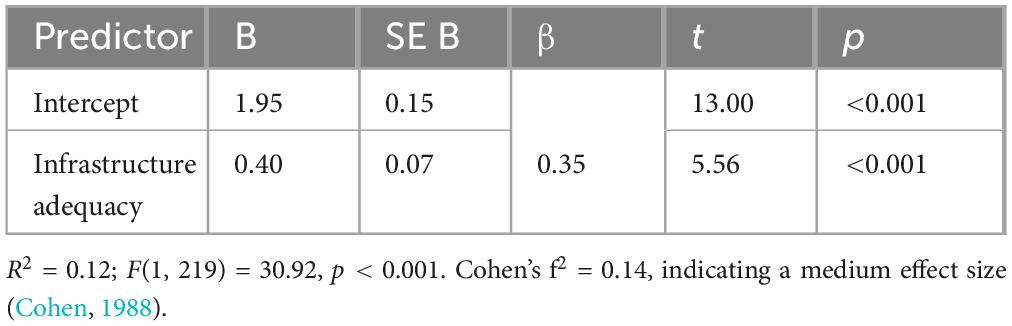

The model was statistically significant: F(1, 219) = 30.92, p < 0.001, explaining approximately 12% of the variance in faculty readiness (R2 = 0.12). The regression coefficients are shown in Table 2.

When students saw the infrastructure at their university as adequate, they were significantly more likely to perceive their faculty as ready for AI integration. The standardized beta coefficient (β = 0.35) shows a moderate positive relationship. The model accounted for 12% of the change in the faculty readiness perception with a medium effect size (f2 = 0.14), thus pointing to the real importance of institutional infrastructure as a vehicle for faculty capability.

4.1.4 Objective 3: relationship between perceived challenges and satisfaction

In order to examine whether perceived institutional and pedagogical challenges hindered the integration of AI that led to lower student satisfaction, a composite challenge index was created (range: 0–4). This index was based on binary items that reflected barriers such as resistance of the faculty, lack of technical skills, and ethical reluctance.

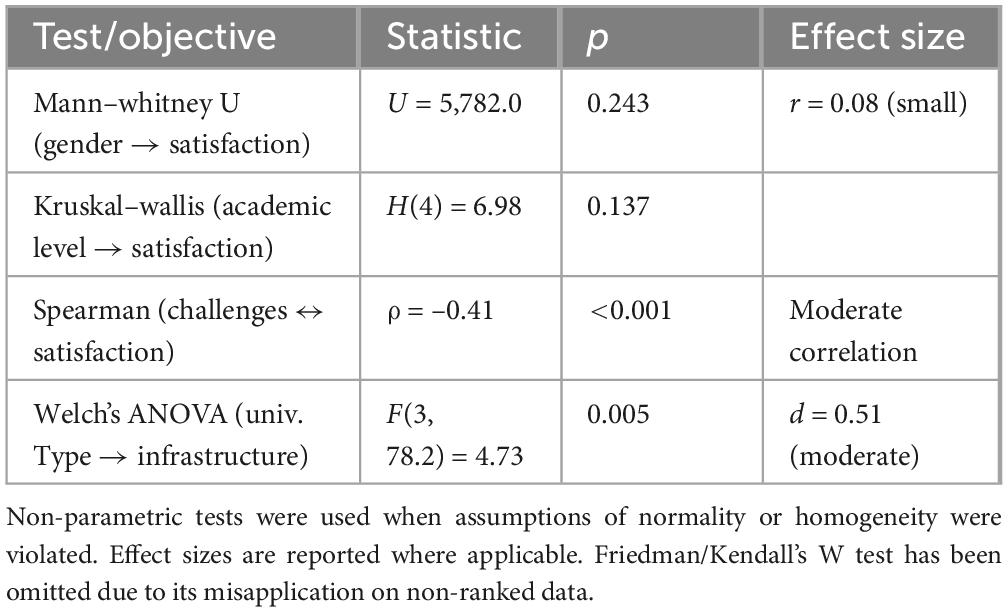

Since the variables were not normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk p < 0.01), a non-parametric correlation was used. Spearman’s rank-order correlation showed a statistically significant moderate negative relationship: ρ(221) = –0.41, p < 0.001

Students who recognized numerous difficulties in the implementation of AI such as the fact that faculty members are not trained, the unwillingness to use AI, or the ethical uncertainty were significantly more likely to report low satisfaction with their academic programs. The correlation coefficient (ρ = –0.41) denotes a medium effect size (Cohen, 1988), thus, institutional readiness has a considerable impact on students’ perceptions of the quality of the AI-enhanced curriculum.

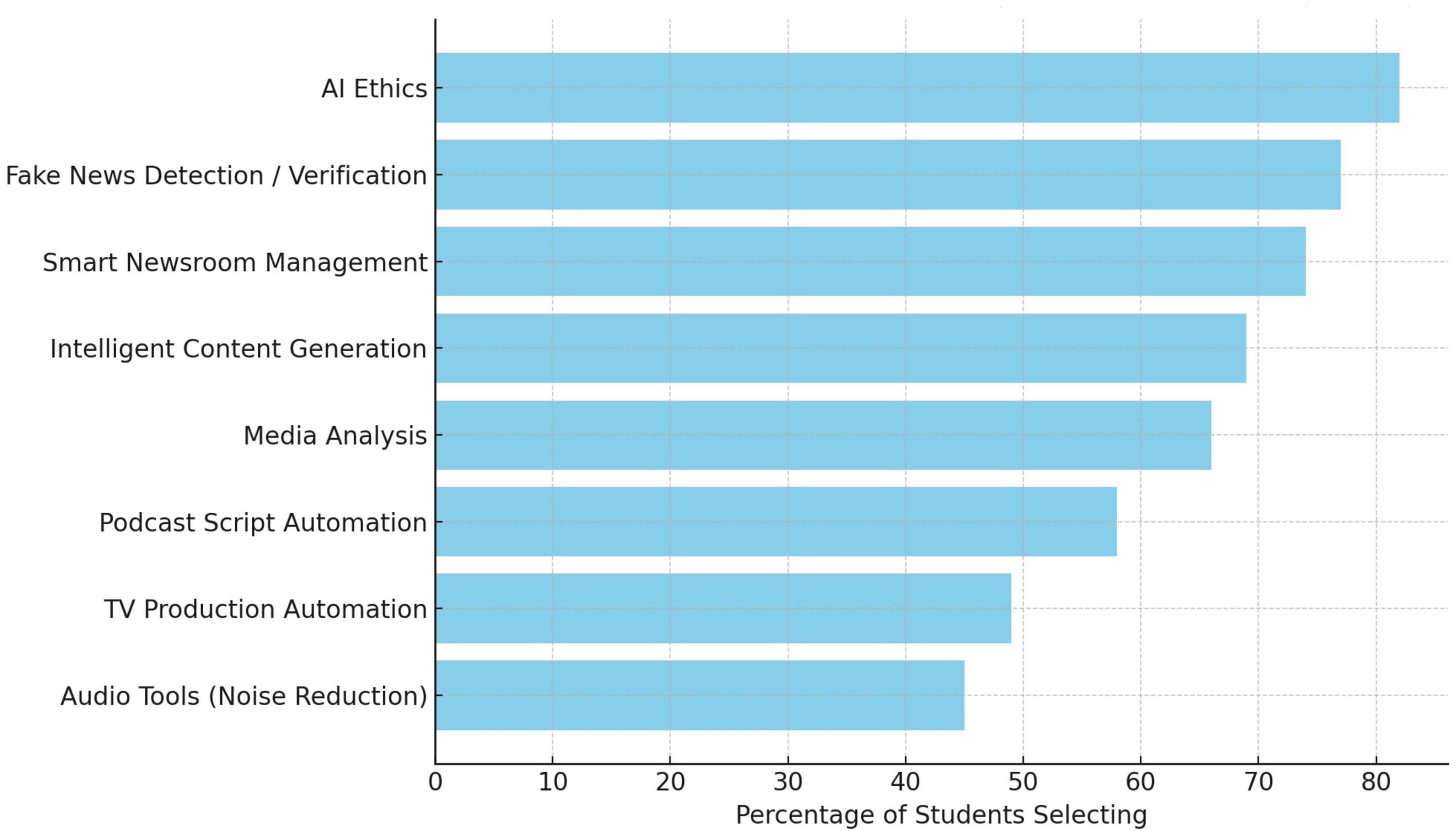

4.1.5 Objective 4: priority domains for AI localization in journalism and media curricula

Students’ preferences for localizing AI in journalism curricula were examined through a frequency-based analysis of an 8-item checklist. In this checklist, students had the option to select multiple priority domains. Each item was considered a binary variable (selected = 1, not selected = 0), with the results shown in Table 3.

Top-Box Frequency Analysis showed that students most often supported the inclusion of AI Ethics (82%) in media curricula, followed by Fake News Detection and Verification (77%), Smart Newsroom Management (74%), and Intelligent Content Generation Tools (69%). The mentioned preferences reflect that students prioritize ethical awareness, content credibility, and practical newsroom applications when considering AI-driven media education. The complete response distribution is available in Table 3.

In order to understand interest at the domain level better, Figure 2 reflects the distribution of student preferences for the integration of AI curriculum in different domain areas.

Figure 2. Percentage of students endorsing each AI integration domain (multiple responses allowed). AI ethics, fake news detection, and smart newsroom management were most frequently selected.

The main takeaway from Figure 2 is the strong focus on ethical and verification-related aspects of the AI curriculum. More than 80% of the students marked AI ethics as a must, and therefore their first choice. Consequently, the topics ontology and automation of the verification process followed by the ethical AI and privacy in the newsroom. A demand for AI education is embodied in these discoveries, which not only support the enhancement of journalistic integrity but also necessitate the strengthening of critical thinking skills instead of the mere production of news by AI. Therefore, it explicitly utters the need for epistemic and ethical anchoring in future curriculum reform.

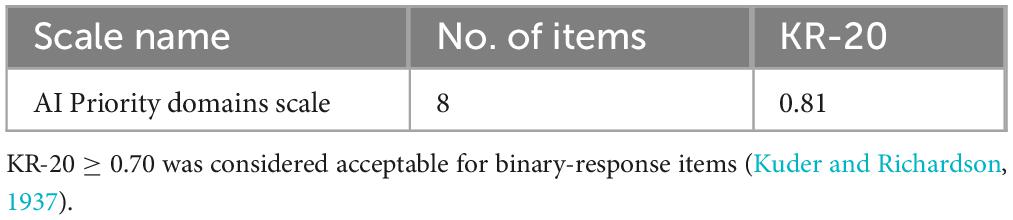

4.1.6 Internal consistency of the domain checklist

In order to evaluate the internal reliability of the eight binary items, Kuder–Richardson Formula 20 (KR-20) was utilized in place of Cronbach’s α (which is for continuous data). The scale showed reasonable internal consistency: Internal reliability results for the domain checklist are reported in Table 4.

AI Ethics and Fake News Detection were the two most prominent domains that students pointed out as the ones that should be localized in the curriculum. The fairly even distribution among the rest of the items indicates that students see numerous potential applications of AI in journalism education. Since the selections were binary and no ranking instructions were given, it was decided not to perform a Friedman test or Kendall’s W, as both require ordinal/ranked data. The range of options chosen, however, indicates that student preferences are not homogeneous, which could mean that students have different levels of institutional exposure to AI or that their schools have different curricular priorities concerning AI.

4.1.7 Objective 5: infrastructure adequacy across university types

A Welch’s ANOVA was utilized to evaluate whether students’ perceptions of infrastructure adequacy vary across different types of institutions. This method was chosen because of the unequal group sizes and the significant difference in variances across the groups as confirmed by Levene’s test (p = 0.041). The test pointed to a statistically significant influence of the type of university on infrastructure adequacy: F(3, 78.2) = 4.73, p = 0.005. The Games–Howell post hoc comparisons indicated that students of non-profit universities reported significantly lower infrastructure adequacy than those of public universities (p = 0.004). The corresponding Cohen’s d = 0.51, which indicates a moderate effect size (Cohen, 1988).

The findings imply that public schools are generally seen as being better equipped to provide AI-integrated education, while non-profit schools seem to be more constrained in terms of resources. Such differences can continue the advantage of some institutions over others, leading to the decrease of satisfaction and the limitation of the effectiveness of AI-related curricular reform.

4.1.8 Structural equation modeling (SEM): faculty readiness as a mediator

4.1.8.1 Model rationale

Working with institutional theory and previous regression results, a mediation model was utilized to check if the impact of infrastructure adequacy on student satisfaction was, in fact, a factor that was passing through faculty readiness perception.

4.1.8.1.1 Estimation method and model fit

The WLSMV estimator (Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance adjusted) was used to estimate the model. This method is suitable for ordinal indicators like Likert-type items.

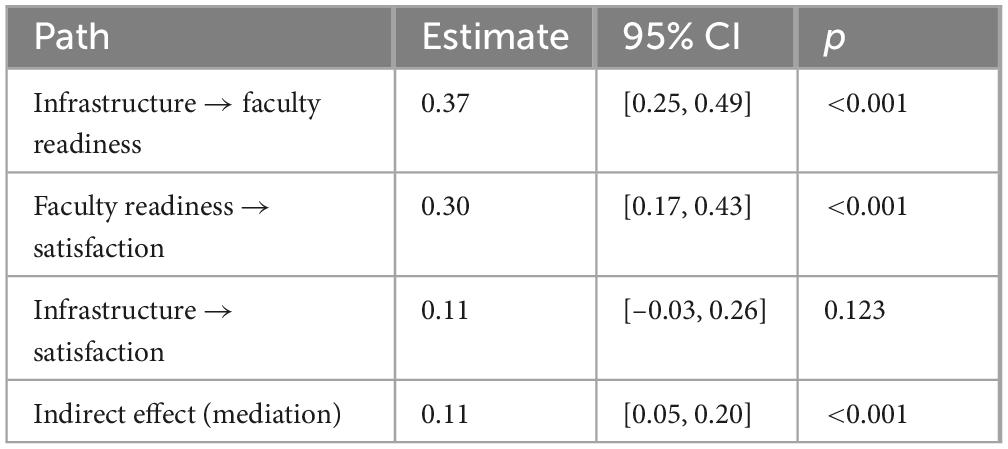

The fit of the model, as judged by the statistics, was perfect:

• χ2(1) = 2.38, p = 0.123

• CFI = 0.99

• RMSEA = 0.048

• SRMR = 0.027

The straightway from infrastructure to satisfaction did not show a significant effect (p = 0.123), however, the indirect effect through faculty readiness was significant and moderate in size (β = 0.11, 95% CI [0.05, 0.20]). The arrangement of the data is in agreement with a model of full mediation, which implies that infrastructure by itself is not a predictor of satisfaction if not along with the perception of instructional preparedness. Path estimates and mediation results are presented in Table 5.

Firstly, the findings highlight the decisive role of faculty readiness in the process of AI curricular adoption, which aligns with institutional theory that stresses the significance of internal capacity together with technological resources.

4.1.8.2 Robustness and sensitivity analyses

• Missing Data: Item-level missingness (<5%) was addressed via multiple imputation using predictive mean matching (20 iterations).

• Sensitivity Check: Models were re-estimated using listwise deletion, yielding nearly identical path estimates.

• Post Hoc Power Analysis: Power for the regression model predicting faculty readiness was estimated at 0.99, indicating that the model was sufficiently sensitive to moderate to large effects with N = 221. However, the power to detect indirect effects in SEM (especially with a non-significant direct path) is generally lower and, therefore, should be considered only to a limited extent. A summary of all inferential tests by objective is presented in Table 6.

4.2 Qualitative findings

4.2.1 Interview participant profiles

The qualitative part of the research was a series of semi-structured interviews with 36 academic experts from media and communication departments in Palestinian universities. The participants were the senior faculty members, department heads, and curriculum specialists, each having more than 5 years of experience in media education. The sample had the different types of institutions (public, private, national) and the different areas (northern, central, southern West Bank) as its characteristics.

In order to keep the participants’ identities confidential, pseudonyms are used when referring to them (e.g., Expert 1, Expert 2).

4.2.2 Theme 1: AI as an epistemic catalyst for curriculum redesign

Every participant agreed that artificial intelligence should not be considered only a technology tool, but it is a transformational power that is changing the very basis for how knowledge is gained in media education. Instead of simply presenting AI as a separate course or skill, the experts were calling for a total curricular change based on a new understanding of knowledge production, truth, authorship, and verification in the era of algorithms.

The change necessitates treating AI as part of core media theory, ethics, journalism, and literacy courses with the help of which students get re-acquainted with the concept of “media literacy” in a machine-mediated environment. The theme was recognized as the most fundamental one and, therefore, was brought up in the context of curricular gaps (Q2), possible interventions (Q5), and course priorities (Q7).

The thematic analysis brought forward three key subthemes that explained the impact of AI on journalism education. Epistemic disruption (25 mentions) reflected the idea of rethinking how media knowledge is produced and taught. Algorithmic logics (19 mentions) revealed the concerns about how automation changes news verification and editorial processes. Reimagining media literacy (28 mentions) pointed to the necessity to embed algorithmic awareness and data ethics in the core curricula. All these subthemes together highlight the urgent call for the fundamental change of the curriculum.

“We’re not just teaching students how to report anymore, we’re teaching them how to question machines that report.” (Expert 7)

“AI changes how knowledge is produced and verified; our curriculum has to show that radical change in knowledge.” (Expert 14)

“The old dichotomy of theory vs. practice disappears when AI is actually the method of media thinking.” (Expert 29)

Experts argued that the traditional journalism curriculum, which assumes human gatekeeping and straightforward storytelling, fails to explain the complexity of information flows that are influenced by machine learning, algorithmic filtering, and data-driven decision-making.

The strong presence of these issues in the experts’ views shows that there is a growing consensus among them that any reform aimed at integrating AI into Palestinian media curricula should not start with tools but rather with an epistemological reorientation that fundamentally changes the way students are taught to define, critique, and produce knowledge in AI-mediated environments. This topic not only changes the media curriculum content but also questions the foundation of media pedagogy.

4.2.3 Theme 2: interdisciplinary convergence and systems thinking

Participants widely agreed that the integration of AI into media education requires moving beyond traditional departmental boundaries. This theme captures the call for interdisciplinary convergence between media studies, computer science, data analytics, philosophy, and design thinking. AI literacy was described as fundamentally cross-sectoral, necessitating partnerships and co-teaching strategies that reflect the hybrid nature of emerging media practices.

Experts emphasized that no single discipline can adequately address the epistemic, technical, and ethical challenges posed by AI. Instead, they advocated for a systems-thinking approach that prepares students to navigate complex, interconnected domains of knowledge and practice.

Thematic analysis identified three key subthemes related to curriculum redesign for AI integration. Interdisciplinary co-teaching, cited by 24 participants, emphasized collaboration between journalism, computer science, and ethics faculty. Curricular modularity (22 mentions) reflected calls for flexible, project-based course structures. Systems thinking orientation, mentioned by 18 participants, highlighted the need to frame journalism as part of broader data and algorithmic ecosystems. These subthemes collectively point to a structural shift in how AI should be embedded in media education.

“We need to abandon the silo model. Media and AI must be co-taught with computer scientists, designers, and philosophers.” (Expert 5)

“Curricula should be modular and built on interdisciplinary clusters editing meets coding, ethics meets machine learning.” (Expert 12)

“An AI-literate journalist must speak both the language of code and the grammar of public discourse.” (Expert 21)

This theme was reinforced across discussions in Questions 1, 3, 5, and 7, particularly when experts outlined actionable reforms such as course redesign, team-teaching models, and institutional partnerships with technology programs.

theme signals a shift from discipline-specific content delivery to interdisciplinary collaboration. Experts envision a curriculum where AI is not isolated in elective courses but integrated across content areas through modular, systems-oriented design. This model mirrors how media content is now produced in real-world, multi-specialist environments, and prepares students for collaborative workflows central to AI-enhanced media production.

4.2.4 Theme 3: ethical reflexivity and critical agency

Experts agreed that one of the first things to do is to implant the sensible questioning of ethics in every media lesson that includes AI. Instead of treating ethics just as a separate unit or a module that students can choose, the participants spoke for a curricular ethicization where ethical literacy is a transversal competency that is common to all courses which deal with data use, automation, journalism, and digital production.

The range of the ethical issues pointed out was very broad and they included algorithmic bias, surveillance capitalism, misinformation, and loss of human agency. The participants emphasized that students have to be given the necessary skills not only to handle AI tools but also to be able to challenge the logics and results of those tools at local, regional, and global levels.

Investigators uncovered three main subthemes that broadly pointed to the moral aspects of using AI in media education. The term critical digital agency was brought up by 26 participants and it referred to the need of giving power to students in order that they challenge and critically navigate AI systems. The issue of algorithmic bias and discrimination was discussed as a major concern in 23 instances and it indicated that as a result of AI social inequities might be reinforced in the production of the news. The participants (21) who mentioned surveillance and data ethics most of all, concentrated on the necessity of instructing students to understand and oppose the data practices that are not transparent. These subthemes, when considered together, call for embedding ethical reflexivity across journalism curricula as being of the utmost urgency.

“Students should learn how to read against the algorithm and be able to question its inherent assumptions.” (Expert 30)

“AI ethics is not a question of right or wrong, but rather power, invisibility, and systemic inequality.” (Expert 11)

“Giving students critical agency when the AI is present, means, essentially, making them understand that they are not only influenced by technology, but they can also influence it.” (Expert 17)

The theme emphasizes the need of students’ being transformed from mere consumers of AI into critical agents who can question the societal and technological aspects of AI. Experts said that within the Palestinian context, which is characterized by digital surveillance, geopolitical marginalization, and cultural erasure, ethical reflexivity should not be seen only as a theoretical issue but rather as a civic imperative. Curriculum should enable students to deal with the ethical issues of AI and thus, prepare them as justice-oriented media practitioners.

4.2.5 Theme 4: infrastructural precarity and digital divide

Most of the participants strongly argued that the differences in technological infrastructure in Palestinian universities have a major impact on the integration of AI in media education. The theme discusses the physical and logistical aspects which limit the use of AI tools. These include old hardware, unstable internet connection, and lack of access to licensed software and computational resources.

Moreover, the participants explained that the infrastructural gaps are not just technical issues but they also structurally create the differences that exist between well-equipped urban and less-equipped rural institutions, public and private universities as well as students coming from different socio-economic backgrounds.

Thematic analysis revealed three subthemes which pointed to the structural barriers that hindered the integration of AI in media education. Technological infrastructure deficiencies that were referred to by 28 participants, were the problems of outdated labs, limited equipment, and unreliable internet. Urban-rural digital divide that was mentioned 21 times, pointed to the differences in access to digital resources between the two geographical areas. Student-level inequities that were referred to by 19 participants pointed to the discrepancies in the availability of personal devices and digital literacy among students. Together, these subthemes reveal the multi-layered nature of the infrastructural precariousness in Palestinian universities.

“In some universities, we do not even have fully operational labs, let alone GPU servers for AI training.” (Expert 8)

“If we don’t have reliable internet and updated machines, then talking about AI integration is just a waste of time.” (Expert 22)

“There is a digital divide even among students, some have personal laptops while others cannot afford mobile data.” (Expert 36)

These infrastructural problems were often associated with the themes of institutional governance (Theme 5) and curricular feasibility (Theme 7), which showed that they had an impact across the board.

This theme points to the fact that materials prerequisites for AI education have to be taken care of first before a curricular redesign or an AI literacy initiative can be successful. Experts emphasized that capacity-building should comprise national funding schemes, international partnerships, and open-access resource strategies to overcome these differences. The unstable situation of the infrastructure is still the main reason for the implementation of AI to be fair and sustainable in Palestinian media education, which is going through a deep crisis.

4.2.6 Theme 5: institutional logics and governance constraints

Governance structures at the institutional level and national regulatory frameworks were identified by participants as factors that not only determine the opportunities but also the constraints for AI integration in media curricula. The theme conveys the complex nature of the interaction of these two forces—the one being the groundbreaking potential, and the other, the bureaucratic inertia. Few of the experts have said that the enforcement of top-down policies has a tendency to close the curricular reform initiatives that come from the bottom up.

The freedom of the teachers to make the courses was mentioned in most of the interviews and in all of the discussions, as it being restricted by old accreditation systems, rigid ministry guidelines, and the lack of coordination between institutions. Experts see slow approval cycles, conservative decision-making, and hierarchical communication within universities as the main reasons that impede the timely adaptation of the curriculum.

Three subthemes highlight the institutional limitations for AI curriculum development. Bureaucratic inertia and delays, described by 27 participants, refer to the slowness of approval processes and resistance to change. Lack of curricular autonomy (24 mentions) pointed to the restriction of decision-making power at the departmental level. Misalignment with accreditation standards, mentioned by 20 participants, illustrated difficulties in the incorporation of innovative content within inflexible national frameworks. In sum, these subthemes reveal systemic governance issues at the governance level that hamper timely and flexible curriculum reforms.

“Even if faculty were to agree on a reform, it might take years before the reform finally goes through academic councils and ministries.” (Expert 6)

“The flexibility is almost non-existent; we still have to find ways to incorporate the new content within the old bureaucratic frameworks.” (Expert 18)

“If the ministry doesn’t give AI an official recognition as a part of the media field, then we are not allowed to create AI courses.” (Expert 25)

The theme also revolved around the perception of inter-institutional politics, the limited fund allocation, and the prevalence of standard academic metrics in assessing the quality of the curriculum.

According to this theme, the issue of curricular innovation goes beyond being just a pedagogical matter and it is rather a challenge of governance. The experts pointed out that the transformative use of AI in the curriculum not only requires faculty readiness but also calls for institutional agility, revised policy frameworks, curricular authority at the local level, and the readiness to move away from the old evaluation systems. If there is no change in the structure both at the institutional and national level, the modernization of media education will be at the risk of getting stuck in the same place.

4.2.7 Theme 6: socio-political contingencies and critical localism

This theme reflects the experts’ acknowledgment that Palestinian media education needs to be based on and considerate of the socio-political realities of the region. Participants highlighted that AI integration should not be a context-neutral process, rather it should be consistent with local morals, linguistic identity, political limitations, and cultural narratives which not only determine the media practice’s possibilities but also its obligations in Palestine.

Several experts condemned the adoption of Western AI models and the media education framework without any changes that fit the particular challenges of institutions and students in Palestine. They advocated for the localism which critically addresses the indigenous epistemologies, linguistic authenticity, and decolonial pedagogies as its main points.

The thematic analysis has identified three subthemes that accentuated the requirement for AI locally grounded in education to be engaged in media. Cultural and linguistic specificity that was discussed by 26 participants pointed to the necessity of constructing AI tools and curricula that reflect the Palestinian language, identity, and values. Contextual resistance and decolonization (23 mentions) were concepts that the participants used to express their worries that the AI frameworks that have been brought in might push the local narratives to the background. The geopolitical constraints on AI implementation, a point made by 19 participants, were referring to barriers caused by the occupation such as limited access to technology and the unstable situation of the area. These subthemes, when taken together, point to the need for AI education to be integrated as part of a culturally and politically responsive framework.

“If we are merely replicating AI media models from the West, then we are removing our context and becoming dependent again.” (Expert 10)

“AI applications have to be passed through our socio-political lens, otherwise, they continue to work against us by reinforcing narratives that do not take us into account.” (Expert 23)

“Palestinian media education should not only be about the resistance against the occupation but also against epistemic colonization.” (Expert 6)

Most of the theme were reflected in the answers to questions 4, 5, and 6. Those questions were about ethical frameworks, changes in the curriculum, and difficulties in the implementation of AI.

These latter points bring to light the necessity for Palestinian universities to rescue curricular sovereignty, not only in a politically aware manner but also by being locally rooted through the creation of media and AI programs. Experts were urging to equip students not only with the necessary technical skills but also with the skills of critical interrogation of the technologies that are imported, resisting being marginalized in terms of knowledge and creating media that helps in the identity, dignity, and agency of the Palestinians. Hence, the creation of AI-equipped curriculum has to be influenced by critical localism so that it is in harmony with the regional realities and can attract culturally sustaining pedagogies.

4.2.8 Theme 7: actionable course architectures and pedagogical modularity

The final theme illustrates the specific educational strategies experts planned to integrate AI into media education in Palestine. Participants repeatedly emphasized the necessity of a modular and flexible course design that would be able to respond to the fast-changing nature of AI tools and applications. Instead of treating AI as one fixed topic in existing courses, it would be better to have a scaffolded structure of core and elective modules through which the student’s competency is developed gradually in theory, practice, and ethics.

Such changes also involved starting courses of algorithmic journalism, data storytelling, media automation, and AI-assisted investigative reporting, and AI literacy training being progressively integrated into trad plus journalism, communication theory, and media ethics courses.

The practical strategies of AI implementation in media education were reflected in those three subthemes which raised their voices most frequently. Twenty-five participants brought up the modular curriculum design as they found course structures should be not only flexible but also scalable to be able to absorb changes of institutional capacities. The second idea of the role specific AI paths, which was mentioned 20 times, implied the establishment of different tracks for different media sectors such as reporting, editing or production so that the users could choose a specialization. Agile curriculum updating referred to by 22 participants, was the idea that puts the central point of a very quick response to course changes that are in line with rapid innovations in technology. These subthemes, in combination, point to the necessity of designing AI curricula that are not only adaptive but also application-focused.

“We need to go beyond general overviews to stackable modules that learners can self-direct based on their specialization and requirements.” (Expert 13)

“The next step would be curricular flexibility. AI curricula should be different every year, not every accreditation cycle.” (Expert 28)

“Structure should revolve around student profiles. Those wanting to do editing, coding, or reporting, each will require different AI pathways.” (Expert 31)

The topic was very prominent in the response to Question 2, 5, and 7, where the respondents described their preferred course formats, sequencing, and practical integration mechanisms.

The theme here indicates a move back to pedagogical pragmatism and readiness for the future. The experts view modularity not only as a means to deal with the complexity of the content, but also as a method to empower both students and instructors during a time of technological change. The emphasis on adaptability and role-specific customization indicates a shift from general AI teaching to targeted curricular pathways, thus ensuring that they are relevant to the different student goals and institutional capacities. The call for frequent curriculum updates also mirrors the need for institutional agility if they want to be able to keep pace with AI advances in media production and communication.

5 Discussion

It is a vital question due to the rapidly changing requirements of the Fifth Industrial Revolution how well the Palestinian media faculties are pedagogically and institutionally ready to integrate AI in their journalism curricula. They employed a convergent mixed-methods design and gathered quantitative data from 221 media students, and qualitative data from 36 academic experts in nine universities in the West Bank. The differences between the two strands in these instances reveal a very large gap between the revolutionary potential of AI and the present level of Palestinian media education.

Students rated their AI-related curriculum experience as mediocre only, and this view also came through the qualitative interviews, where faculty and curriculum experts showed their worries about not only the outdated laboratories but also the poorly furnished infrastructures and the lack of institutional support. The issues raised were not limited to gender or academic level and, therefore, they pointed to a systemic problem. The Palestinian institutional stagnation has been very often talked about in the region, and various studies have identified bureaucratic fragmentation and infrastructural inertia as the main factors that hinder AI reform (Al-Khatib and Shraim, 2023; Boumediene, 2023).

This research also unveiled a strong inverse relationship between perceived structural challenges and satisfaction, thus confirming that logistic problems, such as an unstable internet connection and a lack of faculty training, lower the students’ trust in the quality of the curriculum. These situations correspond to Al-Hindi (2022) findings, who provides evidence of comparable obstructions to digital transformation in the academic environments of the countries that share a border with Palestine, and Abdel Ghani et al. (2024) who argue that faculty readiness is the main factor that leads to the successful implementation of digital pedagogy in Arab contexts.

One of the major points that the paper conveys is that faculty readiness can be regarded as the main factor which influences students’ satisfaction with AI curricula. Structural equation modeling was used to verify that educational infrastructure on its own without pedagogical readiness will not bring the desired results, therefore the funds allocated for equipment will not lead to significant educational outcomes. The stated evidence in numbers serves here as a quantitative support for the TPACK framework (Mishra and Koehler, 2006), which assumes that the most effective technological integration should be based on the intersection of technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge. In-depth interviews also helped to uncover the conclusion that the cooperation of the faculties of journalism, computer science, and ethics is necessary for the AI teaching to be effective which is in line with the Khalil and Belal (2023) mixed-methods study on Palestinian faculty perspectives.

Students mention that they would like to see more AI-based applications in the fields of ethics, fake news detection, and intelligent newsroom systems. On the other hand, the difference in their choices most probably is due to variations in their level of exposure and coherence of the curriculum. This is in line with the curricular fragmentation that Joudi (2024) has reported and lack of unified AI frameworks in Arab higher education. Faculty members feel the need for a profound epistemological change in journalism education, in which AI is not just one of the topics, but becomes a core, transdisciplinary, and foundational subject. This is in agreement with the propositions made by Tlili et al. (2021) and Peláez-Sánchez et al. (2024) to re-conceptualize media education through algorithmic literacy and systems-level thinking.

The research data point to the existence of differences in AI preparedness that depend on the kind of institution providing education. Those who study in non-profit universities have reported that their infrastructure was much weaker than that of the public-sector universities and accordingly, there is a digital divide due to the different levels of resources. Similar worries about the situation have been expressed by Alotaibi and Alshehri (2023), who noticed the uneven AI integration in the institutions of the Gulf. The differences show the gradual pattern of exclusion in academic contexts that come after conflicts and they imply the urgent call for the redistribution of resources and reform in governance (Salem and Ayyash, 2024).

Bureaucratic inertia, strict accreditation structures, and fragmented planning were named as factors that consistently hindered any curricular reform. These issues are similar to the institutional problems that the article by Katsamakas et al. (2024) highlights. They argue that without reorganization of the whole system, the AI transformation in universities is just a show. Additionally, participants of this research talked that AI curricular reforms should avoid the pitfall of simply copying Western models. This idea finds support in the discussion of algorithmic colonialism and cognitive displacement (Al Jazeera, 2023; Singh et al., 2025).

The demand for reform based on local culture corresponds with the decolonial AI scholarship, which guides educational institutions to accept local epistemologies, recognize that each language has its own characteristics, and also be aware of the sociopolitical constraints (Veletsianos and Houlden, 2020). From this point of view, the incorporation of AI is a matter of narrative agency-the tool that enables local knowledge systems to be heard against global algorithmic hegemonies. In the same vein, Khlouf (2024) says that the media in Palestine not only are getting ready for AI but through it, they are shaping their identity, resistance, and relevance.

This study presents a triadic framework as a means to lead such changes. The very first, epistemic reconfiguration, signifies throwing away hierarchical knowledge structures and opting for systems thinking as well as interdisciplinary pedagogy. The second, ethical and contextual anchoring, requires that AI ethics be based on the local community this is the position of García-López and Trujillo-Liñán (2024), who suggest the design of algorithms that are culturally sensitive in the field of education. Lastly, pedagogical actionability is about having modular and adaptive curricular tools that are at once reflective of institutional constraints and technological dynamism. The present model is an extension of the OECD-EU (2025) AI Literacy Framework through its embedding in conflict-affected learning environments.

On a theoretical level, the study merges institutional theory, critical pedagogy, and decolonial AI perspectives. On a practical level, it is a call for an urgent collaboration among ministries, universities, and international stakeholders to finance curriculum design that is locally tailored, faculty training in AI ethics, and the development of infrastructure that is fair. Though the omission of Gaza-based universities and the reliance on self-reporting are still its limitations, the methodological triangulation used gives more trust to the findings. Future research could also explore how such interventions as robot journalism or an algorithmic verification course impact student epistemologies, civic awareness, and employability (Siddig, 2025; Splawa-Neyman, 2025).

Ultimately, the study communicates that teaching against the algorithm is not only a form of resistance to automation but also the comeback of narrative sovereignty and educational justice in digitally stratified societies.

6 Conclusion

The study was an evidence-based reaction to a level question regarding to what extent Palestinian universities might align the use of AI in the teaching of the journalism and media. As a result of being in the middle of digitization and structural vulnerability, the findings depict a divided terrain that is not only greatly affected by the lack of infrastructure but also by the pedagogical inertia, governance limitations, and ethical aspects. A convergent mixed-methods research design revealed that faculty readiness was the single most factor that influenced student satisfaction and genuine curricular changes, even more than the state of the infrastructure. This finding shifts the discussion from merely calling for the technology to be invested in and toward the human and institutional side of the matter which is responsible for turning digital tools into educational benefits.

In line with the opinions of academic experts, the case of AI is a very loud signal that it should not be merely regarded as a technological innovation that is used to facilitate tasks. Rather, it is an epistemic force that questions the basic ideas of truth, authorship, and professional practice. Consequently, the use of technology in education was a curriculum-shaping necessity: the matter should be dealt with ethically and reflexively, at the same time, interdisciplinary collaboration and contextual awareness aspects were considered, keeping in mind that the culture and politics of Palestine are the determining factors. The threefold model with epistemic restructuring, ethical-contextual grounding, and pedagogical operability as its core provides a context-aware and theoretically informed interlocutor for confronting these imperatives in fragile, conflict-affected academic milieu.

While this research was confined to higher education institutions in the West Bank and its results mainly depict the situation of the universities in those governorates, the universities in Gaza are not very different in terms of working conditions, infrastructure, and resources, and staff qualifications. This is mostly because the standards for higher education set by the Accreditation and Quality Assurance Commission of the Ministry of Higher Education are quite consistent and they are applied equally to all the institutions regardless of their location.

Accordingly, this study may be of future benefit to universities in the Gaza Strip, particularly in the event of stabilized conditions and the resumption of higher education activities as they were prior to the 2023–2025 war.

Ultimately, improved internet connections or modern computer labs will not be the major factors that pave the way for AI literacy education in the Palestinian media. The transition requires a thorough and courageous revisiting of the knowledge framework, daring policy changes that bring the accreditation in line with ethical AI skills, and pedagogical ingenuity to create syllabuses that not only acquaint students with the operation of algorithms but also with their critique and change. Considering that the media in the region is both a tool of resistance and a sufferer of repression, equipping students with AI-aware, critically grounded, and locally relevant journalistic skills is not only an academic need but also a civic duty.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. For student participants, written digital consent was secured via Google Forms prior to survey completion. For academic experts, verbal informed consent was obtained before interviews, as per the approved protocol. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Arts and Education at Arab American University—Jenin (IRB Approval No. 4/25, dated 03-05-2025). All procedures complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and national research ethics regulations in Palestine. Data were collected anonymously and handled in accordance with institutional privacy and confidentiality standards. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to the Arab American University—Palestine for its support and for providing the institutional environment that made this research possible.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdel Ghani, R., Al-Harbi, K., Al-Shammari, N., and Al-Ruhaile, N. (2024). Requirements for employing artificial intelligence applications in university education from the perspective of faculty members at Umm Al-Qura university. Educ. J. 118, 193–235. doi: 10.21608/edusohag.2023.246482.1365

Al-Batta, A., Alareer, M., and AlHaddad, A. (2024). Palestinian University students’ use of generative AI tools: Insights from nursing and academic writing. Cogent Educ. 11:2380622. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2024.2380622

Al-Khatib, B., and Shraim, K. (2023). Barriers to AI adoption in conflict-affected academic settings: The case of palestine. Technol. Pedagogy Educ. 32, 45–63. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2023.2230945

An-Najah University (2023). Internal report on AI attitudes and usage. Nablus: An-Najah University. [Unpublished institutional report]

Alotaibi, N. S., and Alshehri, A. H. (2023). Prospers and obstacles in using artificial intelligence in Saudi Arabia higher education institutions–the potential of AI-based learning outcomes. Sustainability 15:10723. doi: 10.3390/su151310723

Assaf Dima (2020). The use of digital public relations in the work of higher education institutions: Case study of ‘Arab American’ and ‘Khaddouri’ universities. Master’s thesis, Jenin: Arab American University.

Boumediene, K. (2023). Artificial intelligence technology in media institutions: A field study on a sample of algerian journalists. Int. J. Soc. Commun. 10, 607–623.