- 1Higher Education Development Research Group, Department of Education, Faculty I, University of Vechta, Vechta, Germany

- 2German Institute for Adult Education – Leibniz Centre for Lifelong Learning, Bonn, Germany

This study explores the implementation of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in Belarusian schools, focusing on changes before and after the 2020 political crisis. It examines the feasibility of ESD in a context marked by civic repression, centralized control, and the dismantling of civil society. A mixed-methods design was applied, combining Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of six national policy documents with content analysis of focus group interviews with teachers and students. Findings from the CDA show that Belarusian education strategies between 2016 and 2020 rhetorically aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, state discourse marginalizes civil society and non-formal education, while framing ESD narrowly as environmental literacy and health and safety education. Participation, inclusion, reflexivity, and the political dimension of sustainability—core elements in European ESD frameworks—are absent. Focus group interviews revealed that, despite these limitations, teachers drew on state education programs, local authority support, and “safe” ecological themes to maintain participatory and project-based learning. After 2020, these adaptive strategies were largely dismantled as civil society actors were dissolved, networks eroded, and ESD was reframed to serve ideological purposes. Educators reported profound transformative experiences, characterized by fear, psychological strain, and survival strategies such as avoiding controversial topics or working within discreet peer networks (“small circles”). This study underscores both the fragility and persistence of ESD in authoritarian contexts and calls for further research on how bottom-up educational practices can be supported without placing educators at risk.

Introduction

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is widely recognized as a transformative approach that equips young people with the competencies to contribute to ecologically resilient and socially just societies (UN General Assembly, 2012; UNECE, 2022; UNESCO, 2007). Since the 1990s, education has been positioned as a central driver of sustainable transitions (UN General Assembly, 2015; UNESCO, 2014). Yet international declarations often overlook the diversity of ESD interpretations across regional and national contexts. These differences are particularly visible when comparing UNESCO's policy-oriented framing with the more critical and participatory conceptualizations found in European and North American scholarship.

Understanding how ESD has developed in Belarus requires consideration of both perspectives. UNESCO's approach—largely goal-driven and standardized—focuses on embedding environmental, economic, and social dimensions into curricula and aligning education systems with global agendas such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This framing offers structural and policy-level coherence but tends to prioritize measurable outcomes over locally embedded practices. By contrast, European and North American scholars conceptualize ESD as a dynamic, transformative process that emphasizes critical reflection, democratic participation, and the cultivation of agency. Together, these perspectives provide the framework for analyzing how ESD took shape in Belarusian schools, evolved through periods of limited liberalization, and was later reshaped under authoritarian pressures, particularly after the political crisis of 2020.

In Belarus, ESD developed along a distinct trajectory. It was shaped by translated UNESCO documents, the country's experience in environmental education, and Soviet and post-Soviet pedagogical traditions. Exchanges were stronger within the Russian-speaking educational sphere than with the critical debates prevalent in European discourse (Zhuk et al., 2015). Grassroots initiatives launched in the 1990s by educators, civil society actors, and local communities—often with international support—laid the foundation for sustainability-related learning (Koshel and Samersava, 2008). These efforts gradually connected with formal education through networks and local development projects, though their integration into systemic educational policy remained limited. This historical context is key to understanding the opportunities, constraints, and resilience of ESD in Belarus, which this study examines through three guiding questions:

Which conceptual dimensions of ESD, as identified in international scholarship, are critical for understanding the Belarusian school context?

What opportunities have existed in Belarusian schools to foster equitable, participatory, and sustainability-oriented learning environments, despite systemic constraints?

What barriers have impeded, and continue to impede, the integration of ESD principles and engagement with sustainability issues in Belarusian schools?

To address the first question and provide a framework for analyzing the Belarusian case, the following section outlines how European and North American scholars conceptualize ESD, highlighting the participatory, competence-based, and transformative dimensions that underpin much of the international academic discourse.

In European and North American scholarship, ESD is seen as a critical, participatory, and political process that goes beyond content delivery or prescriptive training. Building on Scott and Gough (2003), Vare and Scott (2007) identify two complementary dimensions: ESD 1, which equips learners with the knowledge and skills to to address immediate sustainability challenges, and ESD 2, which develops competencies for reflection, deliberation, and navigating complex dilemmas. Wals (2011) further highlights the importance of fostering democratic learning environments that support reflexivity, critical thinking, and the co-creation of meaning. He argues that sustainability learning should create spaces for pluralism, dialogue, and shared responsibility, enabling learners to navigate uncertainty and complexity while engaging in collaborative, transformative action. In this view, ESD nurtures learners' civic competencies by fostering qualities such as confidence, empathy, and perspective-switching.

Within the German tradition, ESD is understood as a competence-oriented concept grounded in Gestaltungskompetenz—the capacity to collaboratively shape sustainable societal transformation while building autonomy and democratic agency (de Haan, 2010; Dannenberg and Grapentin, 2016). This conception frames ESD as a form of political education: empowering learners not only to acquire knowledge but to critically reflect on power relations, deliberate on contested futures, and engage as active citizens. Scholars emphasize that Gestaltungskompetenz fosters critical thinking, participatory culture, and co-responsibility needed for transformative action (Bormann, 2013; Michelsen and Fischer, 2019; Overwien, 2010; Rieckmann, 2020; Singer-Brodowski, 2016).

With scarce awareness of these international conceptualizations, sustainability-related education in Belarus took shape in the mid-1990s largely through grassroots environmental initiatives. Local educators in cooperation with local communities developed diverse projects, including school forestry programs, mentoring initiatives, and eco-festivals, often supported by civil society organizations and international donors (Koshel and Savelava, 2014). Schools took part in networks such as the Partner Schools for Sustainable Development, the international SPARE project, and the Green Schools Network, which facilitated professional development, exchange of practices, and resource sharing [Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2017]. One distinctive Belarusian contribution to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) has been the notion of “grandchildren-oriented thinking” (vnuko-orientirovannoe myshlenie), a concept developed by teachers and local community activists to express responsibility toward future generations while preserving local identity and cultural continuity. It reflects a grassroots understanding of sustainability, sustained by educators who drew on intergenerational dialogue, community knowledge, and place-based traditions to support innovative educational practices and civic engagement (Savelava and Kulik, 2023). Within the Belarusian context, this approach illustrates how sustainability discourse has evolved locally, linking global ESD values to national narratives of care, memory, and moral duty.

Between the mid-2000s and 2020, these efforts expanded. More than 200 local sustainable development strategies were adopted (Koshel and Samersava, 2008), schools implemented elective courses on biodiversity and responsible consumption (Andreenko et al., 2007; Shimova, 2010), and educators and students participated in mobility programs like Erasmus+ and eTwinning [Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2017]. The Belarusian government also adopted national strategies linking ESD to youth development, green economy, and teacher training [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM), 2017; Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2020), 2020; Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM), 2021; Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE), 2021, 2024; Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2021]. Despite these developments, many initiatives failed to become systematically embedded in the education system. ESD was scarcely integrated into teacher education or national competence frameworks (Office of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, 2022).

A brief liberalization between 2014 and 2020 opened new opportunities. Civil society organizations, including the Association “Education for Sustainable Development,” collaborated with state institutions such as the Belarusian State Pedagogical Maxim-Tank-University (BSPU). These partnerships revitalized earlier structures supporting the UNECE ESD Strategy, led to national conferences and school festivals on sustainability education, and in 2017, resulted in the designation of BSPU and the Association as the Regional Center of Expertise on ESD by the United Nations University's Institute for Advanced Studies. A 2017 joint report by Belarusian institutions provided the most detailed review of ESD implementation in the country, proposing a context-based whole-school approach to sustainability practices [Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2017].

The events of 2020 marked a decisive turning point for Belarusian civil society and its educational landscape. The mass protests, driven by calls for justice and civic freedoms, were met with repression (Mateo, 2022; Rudnik, 2025). More than two-thirds of NGOs active in the environmental and educational sectors were liquidated, dismantling collaborative networks and eroding opportunities for resource sharing and peer support (Korshunau, 2024). Values associated with civil society—justice, solidarity, and participation—once embedded in environmental education, were redefined by the state as threats to the regime. Educators engaged in sustainability and civic-oriented education were among those targeted, facing dismissal, forced emigration, or intimidation. By 2024, nearly all non-state schools and informal education centers had been closed, and opportunities for international cooperation had dwindled. State schooling grew increasingly militarized and ideologically rigid, with sustainability-related content limited to ecological literacy framed within state-approved narratives [Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2023; Tereshkovich, 2024]. This governance shift has direct implications for ESD, narrowing the space for participatory, critical, and transformative pedagogies.

This study sheds light on how a fragile yet vibrant infrastructure for sustainability learning was dismantled and reoriented under authoritarian pressure. By analyzing the narratives of students and educators alongside official policy discourses, it examines the conditions under which ESD emerges, survives, or collapses in politically constrained environments.

Materials and methods

Research design and analytical frameworks

This study adopts a qualitative mixed-methods design, combining (a) Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of six Belarusian national policy documents and (b) qualitative analysis of focus groups interviews with migrated Belarusian students and teachers residing in Belarus. The two data sources were integrated at the stage of interpretation (convergent approach) to analyze the possibilities and constraints of implementing ESD in authoritarian education contexts.

Critical discourse analysis (CDA)

A critical discourse analysis CDA (Fairclough and Wodak, 1997; Wodak, 2014) was conducted on six key national policy documents adopted between 2017 and 2024: the National Strategy for Sustainable Socio-Economic Development until 2030 [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM), 2017]; the National Strategy for Sustainable Development until 2035 [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2020), 2020]; the State Program “Education and Youth Policy” for 2021–2025 [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM), 2021]; the Concept for the Development of Pedagogical Education for 2021–2025 [Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2021]; the National Action Plan for the Development of Green Economy for 2021–2025 [Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE), 2021]; and the Project of the National Strategy for Sustainable Development until 2040 [Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE), 2024]. These documents were selected after a preliminary screening of all nationally adopted policy frameworks available in the web catalog of the National Library of Belarus that explicitly addressed both sustainability and education. The inclusion criteria prioritized comprehensive strategic documents that define the state's approach to sustainable development and education policy at the national level, ensuring coverage of both environmental and pedagogical dimensions.

Using a combined inductive–deductive coding approach, we first identified themes from the texts (e.g., patriotism, loyalty, digitalization, marginal role of NGOs) and then interpreted them through CDA frameworks (Fairclough, 2003; Hyatt, 2013). Keyword frequency and co-occurrence checks (e.g., “state,” “civil society,” “ESD,” “participation,” “traditional values”) supported claims about salience and omission (see Supplementary Tables 1, 2. Frequency checks matrix across six documents).

Following Fairclough's three-dimensional CDA model, recent educational policy analyses have shown how discourse reinforces institutional power and shapes meaning in formal systems (Taylor, 2004; Wodak, 2014). We assumed that discursive practices, understood as social practices, carry ideological implications and reproduce unequal power relations. Based on this assumption, we applied a CDA lens (The Critical Policy Discourse Analysis Frame), suggested by Hyatt (2013) to examine which policies supported ESD practices, which offered methodological guidance, and to what extent ESD was promoted or subordinated to state ideology.

Focus group interviews, recruitment, and ethics

To explore lived experiences of sustainability practices in schools, we conducted nine focus group interviews between June and December 2024 with 26 participants: 20 Belarusian adolescents (aged 15–19; 12 boys and 8 girls) and six teachers (two men and four women, aged 41–67). The students had emigrated to Poland and Germany following the political crackdown, while the teachers included both in-service and dismissed professionals currently residing in Belarus. Participants were recruited through purposive and snowball sampling, using diaspora chat groups for students and closed professional networks for teachers. Due to institutional restrictions and safety concerns, recruitment through schools or public media in Belarus was not possible. Only trusted individuals with prior links to the research team were invited to participate.

The inclusion criteria required that adolescent participants had attended Belarusian secondary schools prior to emigration and that teacher participants had experience working in the Belarusian school system, either currently or before 2020. Students represented a range of urban and rural schools, while teachers had 20–30 years of professional experience across different subjects. Seven focus group interviews with student participants were conducted in person—two in Bremen (Germany), three in Wrocław (Poland), and two in Warsaw (Poland)—during June and July 2024. To minimize risks and accommodate distance, two online focus group interviews with teachers were conducted in December 2024. Each group typically included three participants, except for one with two.

All focus groups were conducted in a permissive and non-threatening atmosphere to encourage open discussion (Krueger and Casey, 2015); in several cases, the conversation evolved into problem-centered interviews, allowing for deeper narrative reflection (Witzel and Reiter, 2012). Each session lasted 2–3 h, was audio-recorded and transcribed, and subsequently analyzed using ATLAS.ti.

To ensure confidentiality, participants were anonymized with the following coding system: ST = student group, T = teacher group; the first number indicates the focus group (1–9), and the second the participant within that group (e.g., ST4_1 refers to participant 1 in student focus group 4). All participants provided informed consent, and parental consent was obtained for minors. Ethical approval was granted by the relevant university ethics committee, and all procedures complied with established standards for research involving vulnerable populations and politically sensitive contexts.

Data collection and analysis

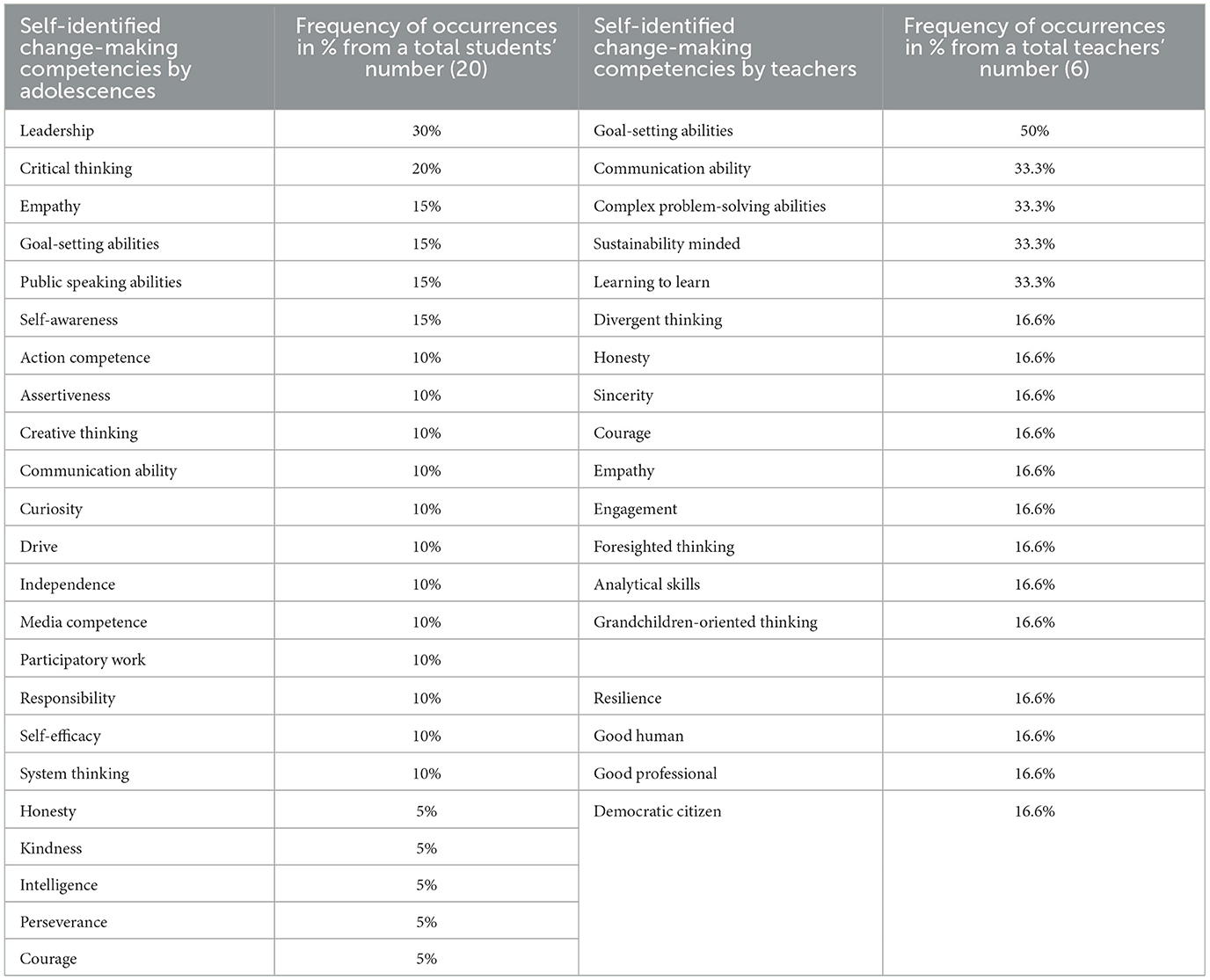

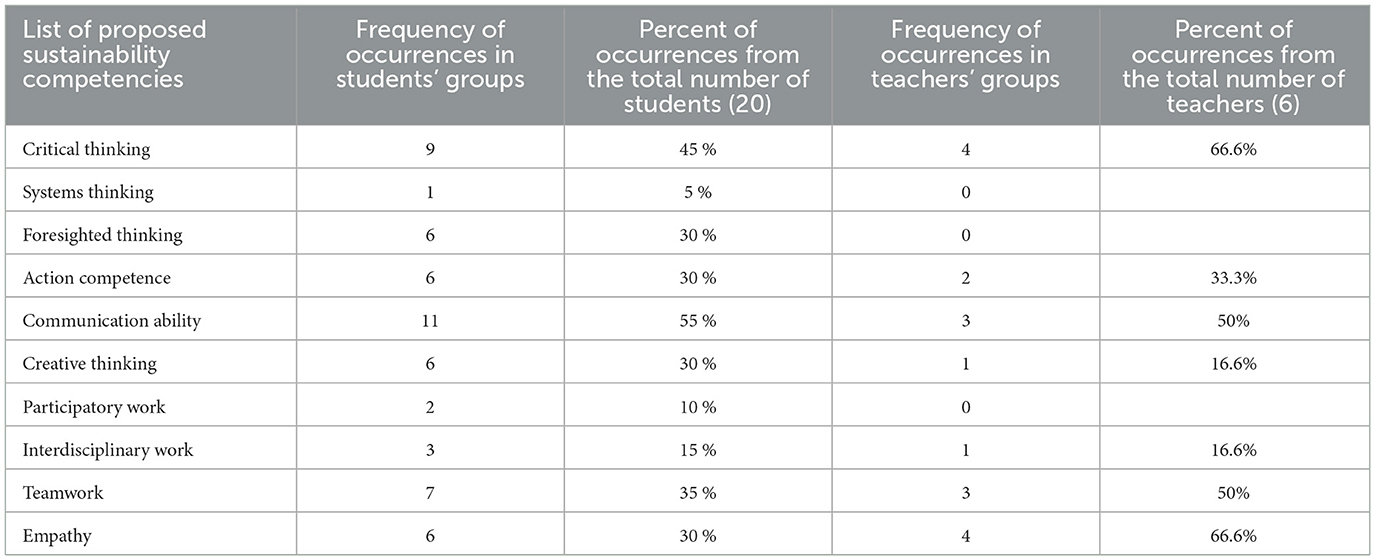

Both interview guides were structured around the whole-school approach to sustainability (Mogren et al., 2019; Tilbury and Wortman, 2005; UNESCO, 2017), addressing four dimensions: teaching and learning, school facilities, partnerships, and participation. The guides introduced the concept of sustainability, invited reflections on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and concluded with a competence-cards exercise. Participants selected up to three competencies they regarded as most important from a list of ten widely recognized sustainability competencies (Sposab and Rieckmann, 2024)—critical thinking, systems thinking, foresighted thinking, action competence, communication, creative thinking, participatory skills, interdisciplinary work, teamwork, and empathy—and explained their choices (see Table 1).

The student guide emphasized perceptions of ESD practices in Belarusian schools compared with current experiences in Poland and Germany, while the teacher guide focused on professional experiences of embedding ESD in teaching, facilities, and extracurricular projects. Teachers were also asked to reflect on participatory structures in Belarusian schools before and after 2020 and their relevance for practice, drawing on perspectives that view teacher leadership as crucial for embedding ESD even within constrained systems (Ghamrawi et al., 2025).

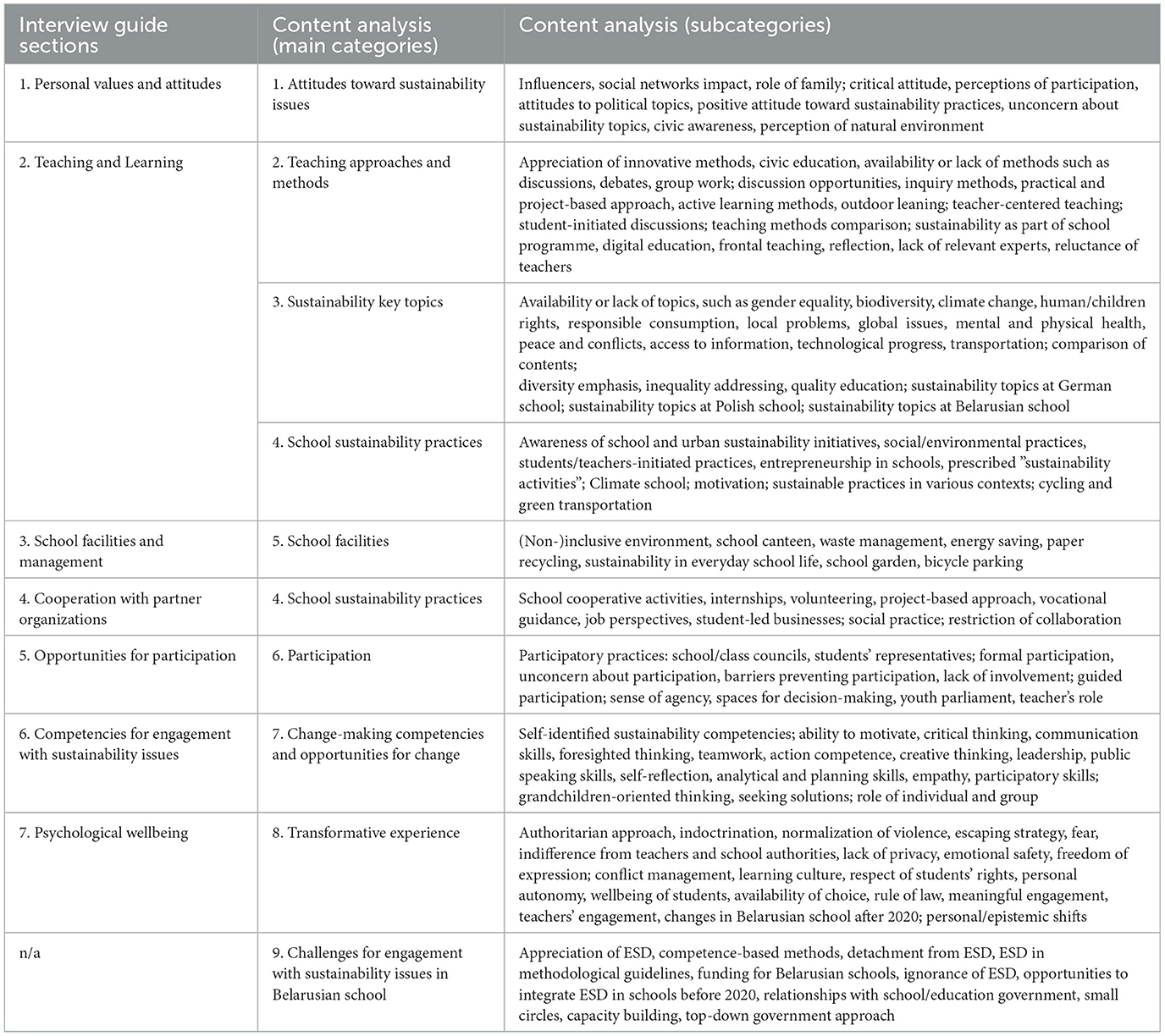

Analysis of the anonymized interview transcripts (in Russian and Belarusian) was conducted using a hermeneutic and category-based coding approach in ATLAS.ti, following established procedures of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2014) and thematic coding (Kuckartz, 2014). A combined deductive–inductive strategy guided the coding process: a preliminary framework derived from the research questions and interview sections was piloted, revised, and applied across two coding cycles (Rädiker and Kuckartz, 2020). Text segments were coded with thematic and analytical labels, yielding nine main categories and 185 subcategories, which correspond to the major thematic domains of the interview guide (see Table 2). Interviews were interpreted within their communicative and cultural context (Bohnsack et al., 2010), acknowledging that meanings are co-constructed through shared socio-political experience. Coding was performed iteratively and collaboratively: two researchers independently coded a subset of interviews, compared results, and refined the codebook to ensure consistency and transparency.

A specific analytical focus was placed on transformative experience coding, informed by transformative experience theory (Paul, 2014) and transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1991; Illeris, 2013). This stage of analysis identified narrative instances where participants described profound professional or personal changes related to sustainability and education. Inductive subcategories included themes such as indoctrination, normalization of violence, fear, loss of autonomy, meaningful engagement, and teacher involvement. Through iterative comparison and interpretation, these accounts were grouped deductively into a broader transformative experience category, conceptualized as sequences of disruption, reflection, and adaptation. Four recurring dimensions were identified: (1) politically motivated dismissal or demotion; (2) narrowing or loss of educational spaces for sustainability practices; (3) collapse of peer collaboration and international partnerships; and (4) increasing ideological influence within school communities.

Results

Critical discourse analysis

The analysis of six policy documents adopted between 2017 and 2024 [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM), 2017; Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2020), 2020; Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM), 2021; Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2021; Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE), 2021, 2024] revealed several recurring tendencies in how Belarusian education governance frames sustainability and participation (see Supplementary Tables 1, 2). One prominent feature is language-based exclusion: the dominance of Russian in official documents marginalizes Belarusian speakers and reproduces linguistic discrimination within education. A second is the glorification of the state, consistently presented as the sole legitimate authority ensuring stability and order, while alternative perspectives are omitted. For example, the Strategy until 2035 states: “Belarus is advancing rapidly… enthusiastically supported by the general public, the business community, and government institutions” [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2020), 2020, p. 10].

Closely linked is the marginalization of civil society. References to stakeholder consultation are rare, and civil society is described as a supporting mechanism for state goals: “Cultivating civil society as an instrument of state policy for sustainable development” [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM), 2017, p. 143]. The draft 2040 Strategy mentions civil society only three times, always in terms of value alignment. Frequency checks highlight the imbalance: the word “state” appears 90–140 times per strategy, whereas “civil society” declines from 18 to just 3 mentions. Non-formal education is also largely absent, with only 0–2 mentions across documents.

A further tendency is the avoidance of accountability. Policy texts highlight achievements but rarely acknowledge systemic challenges such as resource shortages or lack of qualified staff. Responsibility for implementation is shifted to schools without providing adequate support or incentives. At the same time, sustainability is persistently framed through technological progress, digitalization, innovation, and economic growth, with these terms occurring 50–400 times per document—far exceeding references to participation or rights. This emphasis positions education as an instrument of competitiveness, narrowing ESD to labor-market skills.

Finally, ESD itself is presented narrowly. References are infrequent, often reduced to ecological awareness, health safety, or digitalization. Competence-based approaches are noted, but the specifics of sustainability competencies remain undefined, and issues such as digital inequality or cybersecurity are absent [Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2021]. Links to international ESD frameworks are minimal.

Discursive legitimation strategies reinforce these tendencies. Following Fairclough's (2003) modes, authorization and mythopoesis dominate, portraying education as stable and successful, requiring no substantial reform. One document claims: “National education in the Republic of Belarus is traditionally one of the highest values of the Belarusian people… The choice of course toward creating a social state has allowed for the determination of the correct strategy for the functioning and development of the education system” [Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd), 2021, p. 6]. Binary framings such as “traditional values” and “truthful interpretation of history” further monopolize civic and cultural narratives [Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE), 2024, p. 16, 32]. Civic competencies and cultural heritage are redefined within a patriotic logic, particularly after 2020, when official discourse emphasized a “patriotic vector” in civic education [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2020), 2020, p. 26].

At the semantic and grammatical level, abstract agency and passivization are pervasive. Passive forms (e.g., “key efforts will be concentrated,” “it is planned to establish”) obscure responsibility and imply universal consensus (Hyatt, 2013). Depersonalized and generalizing formulations such as “all,” “each,” or “fully” reinforce the image of a benevolent state: “All necessary conditions have been created for individual freedom and its integration into the social context” [Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE), 2024, p. 16]. By contrast, inclusive pronouns such as “we” or “our” are absent, limiting possibilities for identification and ownership. Abstract formulations like “the population's commitment” or “Belarus” are frequently used to obscure agency: “The citizens of Belarus are confident about the future” [Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2020), 2020, p. 11].

In sum, the discourse of Belarusian sustainability and education policy systematically privileges state authority, marginalizes alternative voices, and narrows ESD to techno-economic goals, leaving little space for participatory or democratic approaches.

Content analysis of focus group interviews

The interviews revealed diverse perspectives on the presence—and absence—of ESD practices in Belarusian schools. While student accounts were often brief and reflective of limited exposure to ESD, teachers provided nuanced insights into both structural opportunities and persistent constraints surrounding sustainability education before and after 2020. Their responses are organized into thematic categories derived through both inductive and deductive content analysis (Table 2).

Attitudes toward sustainability issues

Most educators—and some adolescents—demonstrated familiarity with the SDGs. Students often linked sustainability to human rights, gender equality, and climate action, with several citing social media as a key source of information: “I've been following different Insta and TikTok accounts about feminism and climate stuff. Before that, I mostly just heard my mum and older sister talking about it” (ST 4_1). In contrast, teachers tended to associate sustainable development primarily with ecology, responsibility, and progress. Importantly, many educators' understandings of ESD were shaped through involvement in non-governmental or European education projects, rather than Belarusian state-led initiatives.

Teachers' perspectives on ESD clustered around three main categories: (1) No exposure, often characterized by a complete absence of ESD-related content in professional development or teacher training: “There was nothing of sustainability topics in our training—neither within professional development courses nor in teaching methodology groups” (T8_1); (2) Self-initiative, where educators introduced some topics informally, without institutional support: “I brought topics, like gender equality or diversity into my lessons informally. The school leadership was indifferent” (T9_3); and (3) External collaboration, where support from NGOs and European programs enabled more systematic engagement: “We worked with local NGOS and had Erasmus+ support through them. That's how we built our extracurricular programs” (T8_1).

Key sustainability topics

The content covered under sustainability topics largely focused on ecological or safety-related themes—such as health protection and Internet safety—typically presented in a depoliticized, technical tone. Students noted the lack of meaningful dialogue: “Climate change or biodiversity—it's taught like from a textbook. No real discussion” (ST2_2); “Human rights… It was discussed, but very carefully” (ST7_2).

Teachers generally adhered to the state curriculum, with limited autonomy even in discussing officially mandated topics such as energy conservation. As one teacher explained, “In our work with children, while talking about environment, we touch on responsibility and reflect on future generations. But these are just informal conversations during homeroom or informational sessions” (T8_1).

However, some educators described using class hours or extracurricular spaces to address local challenges with students like waterbody overgrowth and youth migration from villages, in ways that fostered student agency, critical thinking, and responsible consumption. For instance, one recounted an ecology project: “I believed that our project (producing paper from reed) was beneficial for the village because the ponds were really becoming overgrown with reeds” (T9_3). Such efforts were more common before 2020, when schools could initiate and implement their own programs: “Back then, in the mid-2000s, we had almost a golden time. As a school administration, we could introduce hours for ecology… and develop the programs ourselves” (T9_2).

Following the 2020 crackdown, many teachers restricted critical or non-mandated topics—such as social justice or government accountability—to trusted settings or small student groups. This pattern, labeled “small circles” in the coding process, appeared in 15 separate accounts: “We talk about these things constantly, yes, but only at the class level” (T8_3).

Teaching approaches and methods

Teachers predominantly demonstrated an understanding of the importance of active learning methods for developing competencies. They emphasized student involvement, problem-solving, and collaboration in teaching: “We integrate teamwork into every lesson. Students know their role and don't just wait to be told what to do.” (T8_2) “Even when working with texts, I ask students to analyze information and form their opinions. I encourage them to develop empathy and human qualities.” (T8_3) “We used brainstorming to get everyone involved. Students appreciated seeing their ideas acknowledged.” (T9_1).

Efforts to foster creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and communication were sustained through discreet, innovative practices. One teacher described an online pedagogical tool co-created within a professional online community, which has since been designated as extremist by the Belarusian authorities: “We developed a lesson design tool compiling techniques to build the four Cs—methods teachers could implement easily.” (T8_3)

The use of evidence-based learning, including working with archival materials was highlighted as a means of engaging students meaningfully: “If there are facts, figures, and firsthand accounts, students understand the issue isn't just theoretical.” (T9_2)

Despite understanding the importance of these methods, teachers lacked consistent professional development in active learning and ESD. Innovative practices were typically introduced through self-directed learning, peer-to peer education or international collaborations rather than formal state training programs.

Sustainability school practices, challenges for engagement with ESD in Belarusian school

Teachers mainly reported efforts to integrate sustainability by addressing local issues and involving the community. In addition to the longstanding practice of paper collection—established in schools since Soviet times—they mentioned newer initiatives such as collecting plastic caps, disposing of expired medications, and collaborating with forestry services on climate adaptation projects. These “safe” environmental projects (T9_2) were generally accepted within the ideological boundaries of the education system.

Partnerships—with NGOs, local entrepreneurs, or international bodies—were described as crucial but increasingly difficult to maintain. Teachers emphasized that support from local authorities often determined the success of such initiatives: “When the district head saw the coherence of the new educational environment, she became a supporter” (T9_1). Some educators, especially those with leadership experience, described leveraging system opportunities to implement ideas, such as turning their schools into experimental platforms for innovative projects: “Under the guise of innovative projects approved by the Ministry of Education, you could experiment freely—pursuing the initiatives you believed in, testing them, and then scaling them” (T9_1).

Despite systemic constraints, respondents expressed pride in the tangible impact of their work: “This is the kind of creativity where you can bring all your ideas to life—maybe not all at once, but most of them. Step by step, like building blocks, you create an educational space.” (T8_1); “The youth entrepreneurship incubator showed our students that rural life can be viable” (T9_1).

Participation

Participation was addressed as a key aspect of ESD, with interviewees reflecting on opportunities for student involvement using Hart's Ladder of Youth Participation (Hart, 1992). Consistent with research linking participatory opportunities to students' development of action competence for sustainability (Torsdottir et al., 2024), educators reported that, alongside numerous instances of ‘formal participation' (mentioned over 40 times), students were sometimes consulted and informed, engaged in joint decision-making with adults, and, in some cases, initiated and directed their own activities within the school community. One teacher noted that students contributed suggestions to local authorities, which were positively received (T8_3). Teachers reported the existence of school councils and self-governance bodies but noted that fostering a culture of participation required ongoing effort. Council members—both students and teachers—often needed reminders to share discussion outcomes with their peers (T9_1). Active students were sometimes invited to contribute to local sustainability strategies, an approach categorized as “guided participation.” However, particularly in rural schools, teachers observed that only a small number of students could independently generate and propose initiatives, indicating the persistence of paternalistic dynamics even among educators experienced in organizing ESD-related practices. As one teacher observed, “Only a few students could propose initiatives on their own” (T9_2), reflecting broader tendencies toward adult-directed forms of engagement.

Change-making competencies and opportunities for change

Participants were invited to discuss the competencies needed to apply sustainability principles in schools. At first phase of this exercise students and teachers reflected on which competencies or change-making skills should be developed to help young people address environmental, social, economic, cultural, and political challenges, preparing them as “change-makers” for a sustainable future. Among adolescents, leadership qualities emerged as the most frequently cited change-making competency, alongside communication, public speaking, critical thinking, and goal-setting (Table 1). “For example, if someone in school fights for others' rights and can present ideas effectively, they can inspire action” (ST4_3). “Public speaking helps to present problems and make others think” (ST1_2).

Educators similarly emphasized goal-setting and communication but provided rather a nuanced breakdown of leadership into key components: as problem-solving, learning-to-learn, divergent thinking, foresighted thinking, and analytical skills. They also discussed “grandchildren-oriented thinking” a term emerged in professional communities' discussions about ESD in Belarus.

Adolescents highlighted self-development qualities such as self-awareness, assertiveness, perseverance, courage, and empathy, while educators also valued honesty, courage, empathy, and engagement. These competencies can be seen as indicators of the transformative experiences participants encountered within the education system, as they represent capacities often developed when individuals navigate disruption, negotiate conflicting values, and adjust to shifts in social and institutional expectations. Developing these competencies frequently involves critical reflection on previously held assumptions and roles, fostering a sense of resilience and agency, even under restrictive conditions. As one teacher expressed, “The most important thing is to teach them to preserve human dignity” (T8_3). Another emphasized relational integrity: “To be honest and sincere—I probably meant that if people sense insincerity in you, you won't gain allies, and no one will support you” (T8_1). These reflections suggest that personal values and ethical orientation are seen as integral to educational impact.

To explore engagement with competencies, we drew on UNESCO's framework of sustainability competencies (UNESCO, 2017) and recent research on secondary school education (Sposab and Rieckmann, 2024). Participants were presented with a set of ten cards, each depicting one of the 10 widely recognized sustainability competencies together with a short explanation of its meaning. After reviewing the cards, they were asked to select up to three and justify their choices.

Across both groups, critical thinking and communication consistently ranked highest (selected by 45% to 65% of respondents), while over 30% identified action competence, empathy, and teamwork as essential (Table 3).

Illustrating this, one student stated: “Action competence is essential because solving problems requires action, even if it involves mistakes” (ST1_2). Another noted the collaborative dimension of learning: “Teamwork is about everyone working together, not having a leader” (ST3_3). Teachers also addressed the challenges of embedding these values in practice: “Teamwork is difficult because students resist working in groups they didn't choose, but I explain its importance” (T9_3).

Teachers most frequently highlighted leadership, communication, critical thinking, public speaking, and goal-setting as essential competencies for young people to address sustainability challenges (Table 3). They also emphasized the importance of developing the 4Cs—communication, critical thinking, collaboration, and creativity—alongside emotional intelligence and what they referred to as “skills for sustainable personal development.” These were often associated with the officially introduced concept of functional literacy. In parallel, participants referred to the culturally resonant idea of “grandchildren-oriented thinking,” which for them embodied sustainability values deeply embedded in Belarusian traditions—particularly a holistic concern for both people and the natural environment, understood as inseparable and transmitted across generations.

Transformative experience

This category primarily reflects the experiences of teachers, as students' transformations were largely tied to migration and encounters with new learning environments. Educators described profound professional and personal challenges after the 2020 political crisis. Subcategories such as Relationships with authorities, Decision-making spaces, and ESD in guidelines pointed to structural constraints, while Fear, Lack of safety, and Indoctrination captured the psychological insecurity affecting both teachers and students.

Before 2020, many teachers created small spaces for active learning using brainstorming, workshops, and simulations on relatively “safe” topics such as biodiversity or climate adaptation (T8_3, T9_1). These approaches encouraged reflection and critical thinking. After 2020, however, methods once supported as engaging became regarded by administrators as undesirable or even threatening.

Analysis revealed four recurring dimensions of transformative experience that show how authoritarian restrictions reshaped educators' realities:

1. Politically motivated dismissal or demotion. Several teachers reported losing positions or being downgraded for perceived disloyalty. Such sanctions, functioning as warnings, generated fear and withdrawal rather than reflection. As one noted: “I avoid commenting on sensitive topics after 2020… I don't forbid students, but I don't comment” (T8_2).

2. Loss of educational spaces for sustainability practices. Learning environments and cross-curricular initiatives were redirected toward ideological content. Teachers described emotional strain: “Then, everything that had been done turned out to be seen as hostile—the things we were proud of” (T8_3).

3. Collapse of peer collaboration and international partnerships. Teacher networks and school partnerships dissolved, undermining communities of practice and reinforcing isolation. “Supervisors care only about meeting targets and compliance, not about innovative projects or partnerships” (T9_2).

4. Growing ideological influence on schools and communities. Ideological narratives increasingly shaped classrooms, parent meetings, and extracurriculars, reframing civic and ecological initiatives in patriotic terms. As one teacher remarked: “An uneducated patriot… is the ideal graduate who will ensure Belarus's sustainable development” (T9_1).

Together, these dimensions illustrate how possibilities for transformative learning are curtailed. Educators still carve out discreet spaces for reflection, but their practices remain heavily shaped by repression and ideological control.

Discussion

Our findings show that a fragile but vibrant infrastructure for ESD in Belarus—built through teacher initiative, local projects, and selective partnerships—was progressively narrowed and reoriented after 2020. Policy discourse aligned rhetorically with SDGs yet reduced ESD to techno-economic goals (digitalization, STEM, green economy) and marginalized civil society, while schools intensified patriotic-ideological content and administrative control. In this context, educators shifted from open, participatory methods to risk-avoidant “small circles,” maintaining critical and competence-oriented practices only discreetly and at personal cost. Students' accounts confirmed limited deliberation on contested topics and instrumental framing of sustainability in school routines. Together, these patterns highlight both ESD's fragility under authoritarian governance and the adaptive agency of teachers and students working within tight constraints.

As an interpretive lens, our results align with a dual ESD framing: ESD1 (functional skills and compliance with immediate goals) was amplified, while ESD2 (critical reflection, deliberation, civic agency) was curtailed (Vare and Scott, 2007); similarly, competence-oriented ESD (e.g., Gestaltungskompetenz) was visible mainly in discreet peer practices, not in policy or whole-school structures (de Haan, 2010). We therefore read the post-2020 landscape as one where participatory and transformative ESD survives in pockets, rather than systemically.

Belarusian ESD in the context of international and theoretical frameworks

Belarusian experiences with ESD must be read in light of international debates, yet they also reveal distinct specificities. Internationally, ESD is conceived as participatory and transformative, supporting competencies such as critical thinking, agency, and intergenerational responsibility (UNESCO, 2017; Wals, 2011). In European contexts, especially Germany and Scandinavia, research has stressed civic agency and whole-school approaches, while North American literature has highlighted experiential and community-based learning.

Belarusian educators and schools drew inspiration from these global debates but often adapted them locally, most notably through the idea of “grandchildren-oriented thinking” (Savelava and Kulik, 2023), which links sustainability to moral responsibility and community-based learning. The present findings extend this perspective, showing how such grassroots understandings continue to shape educators' and students' values even in post-migration and transnational contexts.

At the same time, official strategies presented a narrowing of ESD. They increasingly equated it with techno-economic modernization and patriotic socialization, excluding broader civic or political aspects (see Supplementary Tables 1, 2 for detailed CDA results). This reflects a wider international pattern of “SDG-washing” (Alkan and Kamasak, 2023; Szklarski, 2024), in which achievements are rhetorically highlighted while deficits—such as scarce funding, weak professional capacity building, and the silencing of civil society—remain unaddressed. Yet research also shows that, when adapted through participatory and context-sensitive processes, ESD can be a catalyst for local transitions toward the SDGs (Kioupi and Voulvoulis, 2022). It is precisely this political and participatory dimension, regarded as vital by scholars (Bormann, 2013; Singer-Brodowski, 2016; Huckle and Wals, 2015), that was absent in Belarusian pedagogical research and education management.

This creates a paradox: Belarusian discourse aligns rhetorically with international agendas but in practice excludes core ESD elements such as participation, reflexivity, and civil society involvement.

These patterns resonate also with authoritarian education dynamics in post-socialist and comparative contexts. Silova (2010) argues that post-socialist educational systems often fold into modernization narratives, marginalizing dissent and civil society in favor of state-led growth agendas. Aydarova's (2019) analysis of Russian reforms as “political theater” similarly shows how change is staged to legitimize state control rather than foster critical educator agency. Comparable constraints are evident in Turkey, where teachers report limited time, resources, and administrative support for eco-citizenship initiatives, while students' environmental engagement remains framed in depoliticized, non-confrontational terms (Öztürk, 2023). These parallels suggest that Belarusian ESD is not an isolated case, but part of broader regional patterns where state agendas, institutional inertia, and cultural pressures constrain the transformative potential of sustainability and citizenship education.

Transformations and constraints: educators' experiences post-2020

The 2020 crisis profoundly altered the possibilities for ESD practice in Belarusian schools. Teachers in this study reported heightened repression, with proactive educators facing professional sanctions or informal pressures, and the pedagogical approaches that once supported critical thinking being reframed within state-driven ideological narratives. Proactive educators have faced professional sanctions or informal pressures, and methodologies such as project- or problem-based learning have been losing their reflective and critical dimensions as they have been absorbed into state-driven ideological narratives (Mateo, 2022; Rudnik, 2025; Tereshkovich, 2024). This shift illustrates how authoritarian constraint undermines ESD's deliberative dimension — a move from ESD2-style critical inquiry to ESD1-style procedural compliance (Vare and Scott, 2007). Teachers who once led participatory clubs or local projects spoke of retreating into isolated pedagogical practice.

Before 2020, despite the constraints of a centralized system, many teachers managed to create spaces for participatory learning using brainstorming, workshops, games, and project-based activities—often focusing on “safe” topics such as biodiversity conservation and climate adaptation (Koshel and Savelava, 2014). These approaches fostered critical thinking and reflection, aligning with the transformative potential described by Sterling (2010). After 2020, however, such spaces contracted sharply. Interviewees described how ecology and civic engagement topics were displaced by patriotic and ideological content, with school plans rebranded from “educational activities” to “ideological and educational work.”

Teachers depicted the post-2020 school environment as dominated by fear, indoctrination, and what some referred to as “normalized violence.” Many abandoned student-centered approaches, shifting toward compliance-focused teaching to avoid professional risks. Coping strategies varied: some educators avoided controversial subjects, reduced extracurricular initiatives, or overextended their working hours to secure their positions; others reoriented their energy toward personal development or sought alternative venues for meaningful educational work. Informal “small circles” emerged as particularly significant in this context—trust-based networks that functioned as protective micro-contexts for critical dialogue, collaborative problem-solving, and mutual support. Within these spaces, elements of transformative learning could still occur, enabling participants to reflect critically on their roles, experiment with alternative approaches, and reaffirm values, even when formal institutional channels had closed.

The dismantling of teacher-driven innovations further underscored the state's disinterest in grassroots educational initiatives, even when apolitical in content. For example, the Adukavanka online community—which had co-developed lesson planning tools to foster 4C competencies and brought together over 1,000 educators—was dismantled by the authorities in 2024.

These experiences align closely with Paul's (2014) notion of transformative experience, encompassing both epistemic shifts (painful insights into “what it is like” to teach under authoritarian conditions) and personal transformations (changes in values, identity, and professional goals). The dissonance between long-held assumptions and the post-2020 reality represents the kind of disorienting dilemmas described in transformative learning theory, where emotional disruption and loss of orientation can catalyze deep identity work and, in some cases, personal growth (Illeris, 2013; Mezirow, 2000). For some teachers, these pressures prompted a cautious reorientation toward personal development or the cultivation of small peer-support networks; for others, they resulted in withdrawal from proactive educational efforts entirely.

Limitations

This study is based on a small and highly specific sample of 26 participants recruited mainly through diaspora networks, which substantially limits the generalizability of the findings. Focus group interviews were therefore context-specific and exploratory, as researchers in exile could not access in-service educators, policymakers, or families inside Belarus. Moreover, students—representing typical school environments with limited ESD exposure—were contrasted with teachers who, due to prior ESD collaborations, had greater familiarity with such practices. These sample differences shaped participants' perspectives, but taken together they provide valuable insight into how opportunities and constraints for ESD are perceived under authoritarian conditions.

Implications for ESD and future research

The Belarusian case illustrates both the fragility of ESD under authoritarian governance and the resilience of grassroots actors. While systemic pressures have curtailed participatory and transformative practices, local educators continued—often discreetly—to foster sustainability competencies through adaptive, context-specific strategies. Concepts such as functional literacy, the 4Cs (communication, critical thinking, collaboration, creativity), and “grandchildren-oriented thinking” exemplify how global ESD principles can be localized to reflect cultural and social realities, even in politically constrained environments (Gruenewald, 2003; Wals, 2011).

For ESD scholarship, these findings underline the importance of examining how transformative pedagogies operate—or are suppressed—in contexts where governance architectures restrict critical engagement. They also point to the need for refining transformative learning theories to account for conditions in which epistemic and metacognitive shifts carry significant personal risks and require deliberate survival strategies. Extending this theorization would involve integrating perspectives from critical policy discourse analysis (Hyatt, 2013; Taylor, 2004; Wodak, 2014) to capture how ideological narratives shape the space for transformative learning.

Future research should investigate how educators navigate such environments, how peer networks and transnational collaborations can sustain critical competencies over time, and how students' transformative experiences—explored in a companion study—intersect with these dynamics. Comparative studies across other politically constrained contexts could further elucidate the adaptive strategies and micro-contexts, such as “small circles,” that enable ESD to persist despite systemic restrictions.

Conclusion

This study examined the opportunities and constraints for engaging with sustainability in Belarusian schools before and after the 2020 political crisis, combining critical discourse analysis of six policy documents with interviews with educators and students. The analysis highlights a stark contrast between state narratives—where ESD was rhetorically linked to the SDGs but narrowed to environmental literacy, safety awareness, and ideological loyalty—and grassroots practices, where teachers fostered participatory skills and context-specific competencies, such as grandchildren-oriented thinking, through local projects and ecological initiatives.

After 2020, these fragile openings largely closed. Four recurring dimensions of transformative experience emerged: politically motivated dismissals, the loss of educational spaces for sustainability, the collapse of peer and international collaboration, and growing ideological influence on school communities. Educators responded with survival strategies, ranging from non-formal online peer communities, discreet circles of support to withdrawal from proactive engagement.

These findings underline both the fragility of ESD in authoritarian contexts and the resilience of educators who adapt to sustain critical learning under pressure. Supporting such context-driven practices and exploring how transnational collaborations might provide safe spaces for exchange remain crucial tasks for future research.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because due to ethical considerations and the sensitivity of the data, including the participation of minors, teachers currently residing in Belarus, and individuals affected by forced migration, the anonymized transcripts of the focus group interviews cannot be made publicly available. Public release could pose security and professional risks for some participants, particularly educators still working in Belarus. Researchers may request limited, anonymized excerpts for academic purposes by contacting the corresponding author, subject to additional ethical review and approval. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Kate Sposab ay5zcG9zb2JAZ21haWwuY29t.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Vechta. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

KS: Software, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. MR: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision. AP: Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the DAAD Hilde Domin Program and by funds from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Vechta.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Belarusian diaspora communities in Wrocław, Warsaw, and Bremen, particularly the youth club Fundacja Spadczyna Białorusi, for their support in participant recruitment and for providing welcoming spaces for the focus group interviews. Special gratitude is extended to the Belarusian teachers who, despite residing and working in Belarus under challenging and often risky conditions, generously shared their time, experiences, and reflections. Their courage and openness have been invaluable to this study. The authors also wish to thank the reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments, which greatly contributed to improving the clarity and quality of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used OpenAI's ChatGPT (version GPT-4.2, 2025) to support the preparation of this manuscript. The tool was used exclusively for language refinement, grammar editing, and suggestions for improving clarity and conciseness. All content, analyses, and interpretations were developed by the author(s), and the final manuscript was critically reviewed and approved by all co-authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1682669/full#supplementary-material

References

Alkan, D. P., and Kamasak, R. (2023). “The practice of “Sustainable Development Goals washing” in developing countries,” in Proceedings of the 6th International Academic Conference on Management and Economics, 15–22. doi: 10.33422/6th.conferenceme.2023.03.150

Andreenko, N., Lastovka, I., and Yablonskaya, Y. (Eds.) (2007). Устойчивое развитие в школе [Sustainability in School]. Minsk: Orekh. Russian.

Aydarova, E. (2019). Teacher Education Reform as Political Theater: Russian Policy Dramas. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. doi: 10.1515/9781438476162

Bohnsack, R., Pfaff, N., and Weller, W. (2010). Qualitative Analysis and Documentary Method in International Educational Research. Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich. doi: 10.3224/86649236

Bormann, I. (2013). “Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung–von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart: Institutionalisierung, Thematisierung, aktuelle Entwicklungen,” in Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Aktuelle theoretische Konzepte und Beispiele praktischer Umsetzung, eds. N. Pütz, M. K. W. Schweer, and N. Logemann (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang), 11–29.

Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2017). Национальная стратегия устойчивого социально-экономического развития Pеспублики Беларусь на период до 2030 г. [National strategy for sustainable socio-economic development of the Republic of Belarus until 2030]. Minsk: CoM. Russian.

Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2020). Национальная стратегия устойчивого развития Pеспублики Беларусь на период до 2035 г [National Strategy for Sustainable Development of the Republic of Belarus until 2035]. Minsk: CoM. Russian.

Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus (CoM) (2021). Государственная программа “Образование и молодежная политика” на 2021–2025 годы [State Programme ‘Education and Youth Policy' for 2021–2025]. Minsk. Russian. Available online at: https://adu.by/images/2021/02/gos-pr-obrazovanie-molod-politika-2021-2025.pdf (Accessed January 14, 2025).

Dannenberg, S., and Grapentin, T. (2016). Education for sustainable development – learning for transformation. The example of Germany. J. Fut. Stud. 20, 7–20. doi: 10.6531/JFS.2016.20(3).A7

de Haan, G. (2010). The development of ESD-related competencies in supportive institutional frameworks. Int. Rev. Educ. 56, 315–328. doi: 10.1007/s11159-010-9157-9

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourse and Text: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203697078

Fairclough, N., and Wodak, R. (1997). “Critical discourse analysis,” in Discourse as Social Interaction, 1st Edn., ed. T. A. van Dijk (London: Sage), 258–284.

Ghamrawi, N., Shal, T., Ghamrawi, N. A. R., Abu-Tineh, A., and Alshaboul, Y. (2025). Unleashing the potential of teacher leadership for ESD: reconceptualising teacher agency as a pillar for school transformation. Front. Educ. 10:1614623. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1614623

Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). The best of both worlds: a critical pedagogy of place. Educ. Res. 32, 3–12. doi: 10.3102/0013189X032004003

Hart, R. A. (1992). Children's Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship. Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre.

Huckle, J., and Wals, A. E. J. (2015). The UN decade of education for sustainable development: business as usual in the end. Environ. Educ. Res. 21, 491–505. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1011084

Hyatt, D. (2013). The critical policy discourse analysis frame: helping doctoral students engage with the educational policy analysis. Teach. High. Educ. 18, 833–845. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2013.795935

Illeris, K. (2013). Transformative Learning and Identity. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203795286

Kioupi, V., and Voulvoulis, N. (2022). Education for sustainable development as the catalyst for local transitions toward the sustainable development goals. Front. Sust. 3:889904. doi: 10.3389/frsus.2022.889904

Korshunau, G. (2024). The Belarus Barometer of Repression. Second Quarter of 2024. Vilnius: Center for New Ideas. Available online at: https://newideas.center/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/barometr-represij-2-2024-en.pdf (Accessed January 12, 2025).

Koshel, N., and Samersava, N. (Eds.). (2008). Партнерская сеть школ устойчивого развития: межрегиональное сотрудничество и устойчивые изменения [School Local Agenda-21: A Manual for General Secondary Schools]. Minsk: Academy of Postgraduate Education. Russian.

Koshel, N., and Savelava, S. (Eds.). (2014). Партнерская сеть школ устойчивого развития: межрегиональное сотрудничество и устойчивые изменения [Partner Schools Network for Sustainable Development: Interregional Cooperation and Sustainable Changes]. Minsk: Academy for Postgraduate Education. Russian.

Krueger, R. A., and Casey, M. A. (2015). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software. London: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781446288719

Mateo, E. (2022). “All of Belarus has come out onto the streets”: exploring nationwide protest and the role of pre-existing social networks. Post-Soviet Affairs 38, 26–42. doi: 10.1080/1060586X.2022.2026127

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Klagenfurt: Beltz. Available online at: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (Accessed July 25, 2025).

Mezirow, J. D. (2000). Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Michelsen, G., and Fischer, D. (2019). Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Schriftenreihe Nachhaltigkeit Heft 2. Wiesbaden: Hessische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung.

Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE) (2021). Национальный план действий по развитию зеленой экономики в Pеспублике Беларусь на период 2021–2025 [National Action Plan for the Development of Green Economy in the Republic of Belarus for 2021–2025]. Minsk. Russian. Available online at: https://sdgs.by/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/o-natsionalnom-plane-dejstvij-po-razvitiju-zelenoj-ekonomiki-v-respublike-belarus-na-2021-2025-gody.pdf (Accessed January 14, 2025).

Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus (MoE) (2024). Проект национальной стратегии устойчивого развития Pеспублики Беларусь на период до 2040 г. [Project of the National Strategy for Sustainable Development Until 2040]. Minsk. Russian. Available online at: https://economy.gov.by/uploads/files/NSUR/proekt-Natsionalnoj-strategii-ustojchivogo-razvitija-na-period-do-2040-goda.pdf (Accessed January 18, 2025).

Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd) (2017). Отчет за 2015–2016 гг. и за истекший период 2017 года о прогрессе по приоритетным областям действий Стратегии ЕЭК ООН для образования в интересах устойчивого развитие [Report for 2015–2016 and for the Past Period of 2017 on Progress in Priority Areas of Action of the UNECE Strategy for ESD]. Russian. Available online at: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/esd/12_MeetSC/Documents/Belarus_country_report_final.pdf (Accessed January 14, 2025).

Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd) (2021). Концепция развития педагогического образования в Pеспублике Беларусь на 2021–2025 годы [Concept of Development of Pedagogical Education in the Republic of Belarus for 2021–2025]. Minsk. Russian. Available online at: https://crpo.bspu.by/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/koncepcija-buklet_.pdf (Accessed January 14, 2025).

Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus (MoEd) (2023). Факультативный курс для 10–11 классов средней школы “Устойчивое развитие” [Elective Course for Grades 10–11 of Secondary School “Sustainable Development”]. Russian. Available online at: https://adu.by/images/2023/geogr/fz_ustoichivoe_razvitie_10-11kl.pdf (Accessed January 14, 2025).

Mogren, A., Gericke, N., and Scherp, H. Å. (2019). Whole school approaches to education for sustainable development: a model that links to school improvement. Environ. Educ. Res. 25, 508–531. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2018.1455074

Office of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya (2022). Belarusian Civil Society Report on Sustainable Development Goals Implementation. Vilnius: Friedrich-Ebert-Foundation. Available online at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1PrGqKMyGltBmakwty5ku-L1XbJaELvqS/view (Accessed January 14, 2025).

Overwien, B. (2010). Globalisierung und Globales Lernen: bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Schulmagazin 5–10, 7–10. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvddzxz4.3

Öztürk, O. (2023). Scientific studies on climate change, children and education: current situation and suggestions. J. Educ. Sci. Environ. Health 9, 16–28. doi: 10.55549/jeseh.1231249

Paul, L. A. (2014). Transformative Choice in Transformative Experience. Oxford: Oxford Academic. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198717959.001.0001

Rädiker, S., and Kuckartz, U. (2020). Focused Analysis of Qualitative Interviews with MAXQDA. Berlin: MAXQDA Press.

Rieckmann, M. (2020). Emancipatory and transformative global citizenship education in formal and informal settings: empowering learners to change structures. Tertium Compar. 26, 174–186. doi: 10.25656/01:25339

Rudnik, A. (2025). Practices and agencies in the Belarusian protests of 2020. J. Contemp. Politics. 77, 537–560. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2025.2495338

Savelava, S., and Kulik, V. (2023). Локализация ЦУP на местном уровне: роль и возможности образования [SDGs Localization at the Local Level: The Role and Opportunities of Education]. Konin: Belarus and World, 3, 88–112. Russian. Available online at: https://kamunikat.org/belarus-i-svet-vesnik-belaruskay-akademii-3-2023 (Accessed January 17, 2025).

Scott, W. A. H., and Gough, S. R. (2003). Sustainable Development and Learning: Framing the Issues. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Shimova, O. (2010). Устойчивое развитие [Sustainable Development: a Textbook for Students, Postgraduates, and Teachers of Higher Educational Institutions of Economic and Environmental Profiles, as Well as Specialists in Ecological-Economic and Socio-Economic Forecasting]. Minsk: Belarusian State Economic University. Russian.

Silova, I. (2010). Rediscovering post-socialism in comparative education. Int. Perspect. Educ. Soc. 14, 1–24. doi: 10.1108/S1479-3679(2010)0000014004

Singer-Brodowski, M. (2016). Transformative Bildung durch transformatives Lernen. Zur Notwendigkeit der erziehungswissenschaftlichen Fundierung einer neuen Idee. Zeitschrift für Int. Bildungsforschung und Entwicklungspädagogik 39, 13–17. doi: 10.25656/01:15443

Sposab, K., and Rieckmann, M. (2024). Development of sustainability competencies in secondary school education: a scoping literature review. Sustainability 16:10228. doi: 10.3390/su162310228

Sterling, S. (2010). Transformative learning and sustainability: sketching the conceptual ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 5, 17–33.

Szklarski, B. (2024). Teaching civics for sustainability in post-authoritarian order: the challenges of developing progressive citizenship in new democracies–lessons from Poland. J. Adult Continu. Educ. 31. doi: 10.1177/14779714241276832

Taylor, S. (2004). Researching educational policy and change in ‘new times': using critical discourse analysis. J. Educ. Policy 19, 433–451. doi: 10.1080/0268093042000227483

Tereshkovich, P. (2024). Current Trends in the Development of the Education Sector in the Republic of Belarus. Analytical Article No. 10. Belarus Research Network on Neighborhood Policy. Available online at: https://belarusnetwork.org/publications/analytical-article-no-10-current-trends-in-the-development-of-the-education-sector-in-the-republic-of-belarus/ (Accessed January 18, 2025).

Tilbury, D., and Wortman, D. (2005). Whole school approaches to sustainability. Geogr. Educ. 18, 22–30.

Torsdottir, A. E., Olsson, D., Sinnes, A. T., and Wals, A. (2024). The relationship between student participation and students' self-perceived action competence for sustainability in a whole school approach. Environ. Educ. Res. 30, 1308–1326. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2024.2326462

UN General Assembly (2012). The Future We Want. Outcome Document of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: United Nations. Available online at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/futurewewant.html (Accessed August 28, 2024).

UN General Assembly (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. New York, NY: United Nations. Available online at: https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/2015/en/111816 (Accessed August 15, 2024).

UNECE (2022). Engaging Young People in the Implementation of ESD in the UNECE Region: Good Practices in the Engagement of Youth. Geneva: UNECE. Available online at: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Engaging_Young_People_web_final_05.09.2022.pdf (Accessed August 29, 2024).

UNESCO (2007). Good Practices in Education for Sustainable Development in the UNECE Region. Education for Sustainable Development in Action. Good Practices N° 2. Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2014). Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Program on Education for Sustainable Development. Paris: UNESCO. Available online at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002305/230514e.pdf (Accessed September 12, 2024).

UNESCO (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO. Available online at: https://www.unesco.de/sites/default/files/2018-08/unesco_education_for_sustainable_development_goals.pdf (Accessed January 18, 2025).

Vare, P., and Scott, W. (2007). Learning for a change: exploring the relationship between education and sustainable development. J. Educ. Sust. Dev. 1, 191–198. doi: 10.1177/097340820700100209

Wals, A. E. J. (2011). Learning our way to sustainability. J. Educ. Sust. Dev. 4, 177–186. doi: 10.1177/097340821100500208

Witzel, A., and Reiter, H. (2012). The Problem-Centred Interview: Principles and Practice. London: Sage Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781446288030

Wodak, R. (2014). “Critical discourse analysis,” in The Routledge Companion to English Studies, eds. C. Leung and B. V. Street (London: Routledge), 302–317.

Keywords: Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), sustainability education in authoritarian contexts, Belarusian schools, teacher and student perspectives, transformative learning, critical discourse analysis, pedagogical autonomy, bottom-up educational practices

Citation: Sposab K, Rieckmann M and Pozniak A (2025) Education for Sustainable Development in authoritarian contexts—Lessons from policy, practice and lived experiences in Belarusian schools. Front. Educ. 10:1682669. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1682669

Received: 09 August 2025; Accepted: 18 November 2025;

Published: 18 December 2025.

Edited by:

José Luis Ortega-Martín, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Fatima Zahra Sahli, Ibn Tofail University, MoroccoConcetta Tino, Ministry of Education, Universities and Research, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Sposab, Rieckmann and Pozniak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kate Sposab, a2F0ZS5zcG9zYWJAbWFpbC51bmktdmVjaHRhLmRl

Kate Sposab

Kate Sposab Marco Rieckmann

Marco Rieckmann Alexandra Pozniak

Alexandra Pozniak