- Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

International schools—a relatively recent type of K-12 educational institution in Mainland China—have expanded rapidly in response to market demand. These profit-oriented schools use English as the primary language of instruction and offer international curricula, factors that heighten management complexity. Operating within the constraints of a socialist system presents additional challenges. This qualitative case study examines the management structures and challenges of such schools, focusing on the dual principal leadership model commonly adopted in these institutions. Data were collected from May to June 2024 through in-depth interviews with eight school leaders across two international schools in Guangzhou and Shenzhen—economically prosperous cities and key hubs for international school growth. Data analysis employed a three-level coding process to identify patterns and themes. Findings indicate that the adoption of the dual principal leadership structure is driven by the schools’ diverse cross-cultural characteristics and the complexities of localized operations, while also revealing tensions between marketing and educational logics in school management. The study proposes strategies to strengthen this leadership model and highlights considerations for its effective implementation. Theoretically, the research extends the application of institutional logics theory to the governance of international schools in market contexts, offering insights into leadership design and decision-making in internationalized school settings where cultural hybridity and institutional pluralism are prevalent.

Introduction

After the formation of the People’s Republic of China, for a long period of time, China was in a closed stage; private education did not exist in the social ownership system. Due to people’s increasing incomes and varied educational needs, private schools started to appear after the reform and opening-up policies in the 1980s (Postiglione, 2006). Since then, as China’s economy has experienced rapid growth, an increasing number of Chinese parents are able and willing to send their children to overseas schools. In addition to giving their kids a better education, these families find that sending their kids to international schools spares them from the intense competitiveness of National College Entrance Examination, which they may use to their advantage when applying to foreign universities (Miao and Qu, 2022).

Due to the aforementioned causes, a new type of private educational institution: the international school, has been established in Mainland China have expanded quickly in order to satisfy the market demand, providing the “luxury” product in today’s education market in Mainland China. As of 2019, there were 406 international schools in China, serving 624,000 students. It is anticipated that there will be about 550 foreign schools in the country by 2023 (Yang et al., 2020). However, running an international school in Mainland China is not an easy task. First of all, these schools are for-profit, relying entirely on tuition fees from parents to support their operations. Secondly, there are more demands on the management and operation of foreign curriculum schools due to the complicated cross-cultural backgrounds seen in these settings (Bunnell et al., 2016). Furthermore, operating in China—a socialist nation with strict ideology and cultural censorship—inevitably presents a number of difficulties.

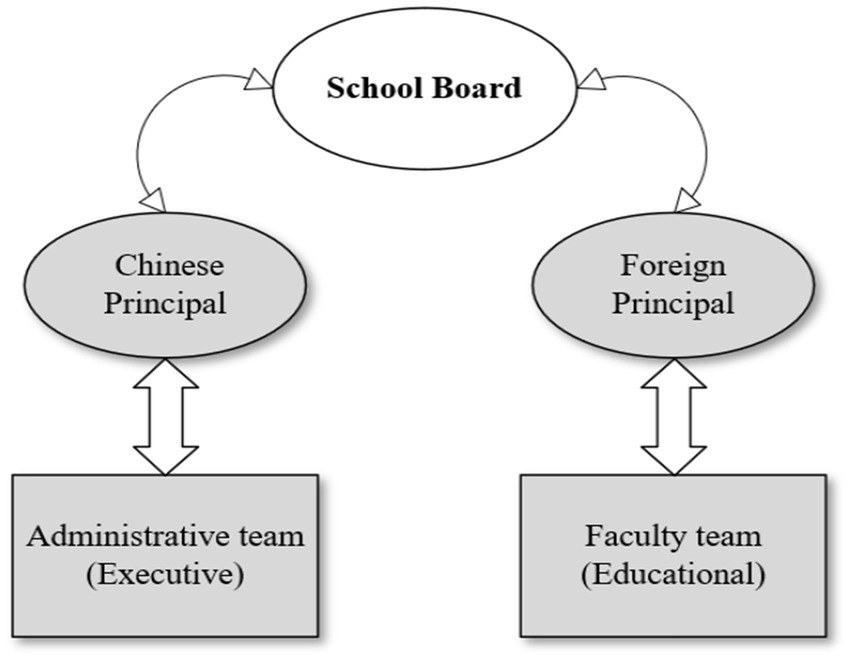

It is this unique situation that led to a dual principal leadership structure in the governance of these schools. The international elements of these schools enable them to charge higher tuition fees, but they also bring significant challenges to their management. In response to the above characteristics and challenges, the school boards usually employ a senior manager as the “CEO” or the executive principal to handle campus operations, local government relations, and financial affairs. In the context of Chinese schools, this “CEO” is often referred to as the Chinese Principal. Meanwhile, they also hire a Foreign Principal as the academic principal, leading the educational team, overseeing academic quality and the management of international curriculum (Miao and Qu, 2022). The two principals manage the school from different perspectives, with different job responsibilities and logics, which often leads to different opinions and conflicts. This kind of “ZHONGXIJIEHE” (中西結合, combination of Chinese and Western cultures) leadership structure provides us with an appropriate research entry point for understanding the governance models of these schools.

Given their relatively short existence, there has been little study conducted on these institutions’ management in Mainland China. In this research, the dual principal leadership structure of these international schools serves as an entry point for investigating critical issues in their management that require more attention and providing potential solutions. This not only can offer better improvement strategies for the stakeholders and practitioners of these schools, but it also enables education policymakers and scholars to comprehensively understand the current management condition of these schools in Mainland China. Based on a review of literature, this study adapts qualitative methodology to research two international schools in Mainland China. Through on-site observations and interviews, the study examines management issues related to the dual principal leadership structure in order to derive research conclusions. It is guided by three main research questions:

1) What are the features of the dual principal leadership structure in these international schools’ management? Why adopt this kind of structure?

2) What are the challenges and difficulties of the dual principal leadership structure?

3) How can we improve the dual principal leadership structure in these schools’ management?

Literature review

Dual principal leadership structure and management logic in private schools’ management

Dual principal leadership

Principals and other administrators must successfully take on these critical responsibilities for their schools to function effectively (Cunningham et al., 2022; Sergiovanni, 2009). However, nowadays, educational administrators are often as managers. Themes such as “cost-effectiveness, finance, integrity, efficiency, salary management, and personnel policies” are increasingly becoming important aspects in education (Sergiovanni, 2009). Schools are constantly giving principals more tasks and treating them like “superheroes” (Masters, 2013), causing them to struggle with balancing these dual roles, feeling stressed, and reducing their focus on educational management (Chairez, 2022). It is challenging for a school leader to be responsible for managing educational and managerial roles simultaneously, and the management of international schools are even more complex and have cross-cultural attributes (Supovitz, 2000; Machin, 2014). This phenomenon is more common in private, for-profit schools (Supovitz, 2000; Fisher, 2021).

Indeed, as the highest authority figure in a school, principals have shouldered too many responsibilities, leaving them overburdened, with many responsibilities far removed from the role of educators (Bunnell, 2008; Machin, 2014). The model of dual leadership or co-principalship is seen as a potential “survival strategy” for overloaded principals (Supovitz, 2000). In the decades following Drucker’s (1954) idea of the ‘one man is best’ leadership model, the number of articles discovering the positive impacts of dual leadership or co-principals in many disciplines has been steadily expanding. For example, Co-principals leadership can minimize stress and job errors (Eckman and Kelber, 2009; Gronn and Hamilton, 2004), avoid conflicts (Masters, 2013; Wexler Eckman, 2006), and improve the creativity of school leaders (Shockley and Smith, 1981; Pan and Chen, 2021).

Dual leadership exists in different forms worldwide. It has been employed in various fields in the People’s Republic of China since 1949, including the education sector (Bell, 2016). The difference is that it is an administrative and political division of management. In public schools in China, Party building, ideology, and politics are led by a party secretary, while the principal is responsible for teaching and administration, and both are jointly responsible for the school’s party committee (Cunningham et al., 2022). In Australia, dual principal leadership began to be used in some principal-lacking areas in schools in the 1980s, bringing about positive impacts and allowing the principal to not have to be a “superhero” and to have more time to focus on education (Masters, 2013; Fisher, 2021).

Many international schools in non-English-speaking countries have two principals one from the host country and one from a foreign country, forming a dual principal leadership structure in their management (Miao and Qu, 2022). It is quite common in the mainstream market of these international schools in the Asia region, it helps the foreign principal who are not familiar with local conditions (Machin, 2014). In these international schools established in non-English speaking countries, the dual principal leadership structure is not originally intended to lighten the principal’s burden or reduce decision-making risks, but rather to address practical issues in school operations (Bunnell, 2008; Wu and Koh, 2022).

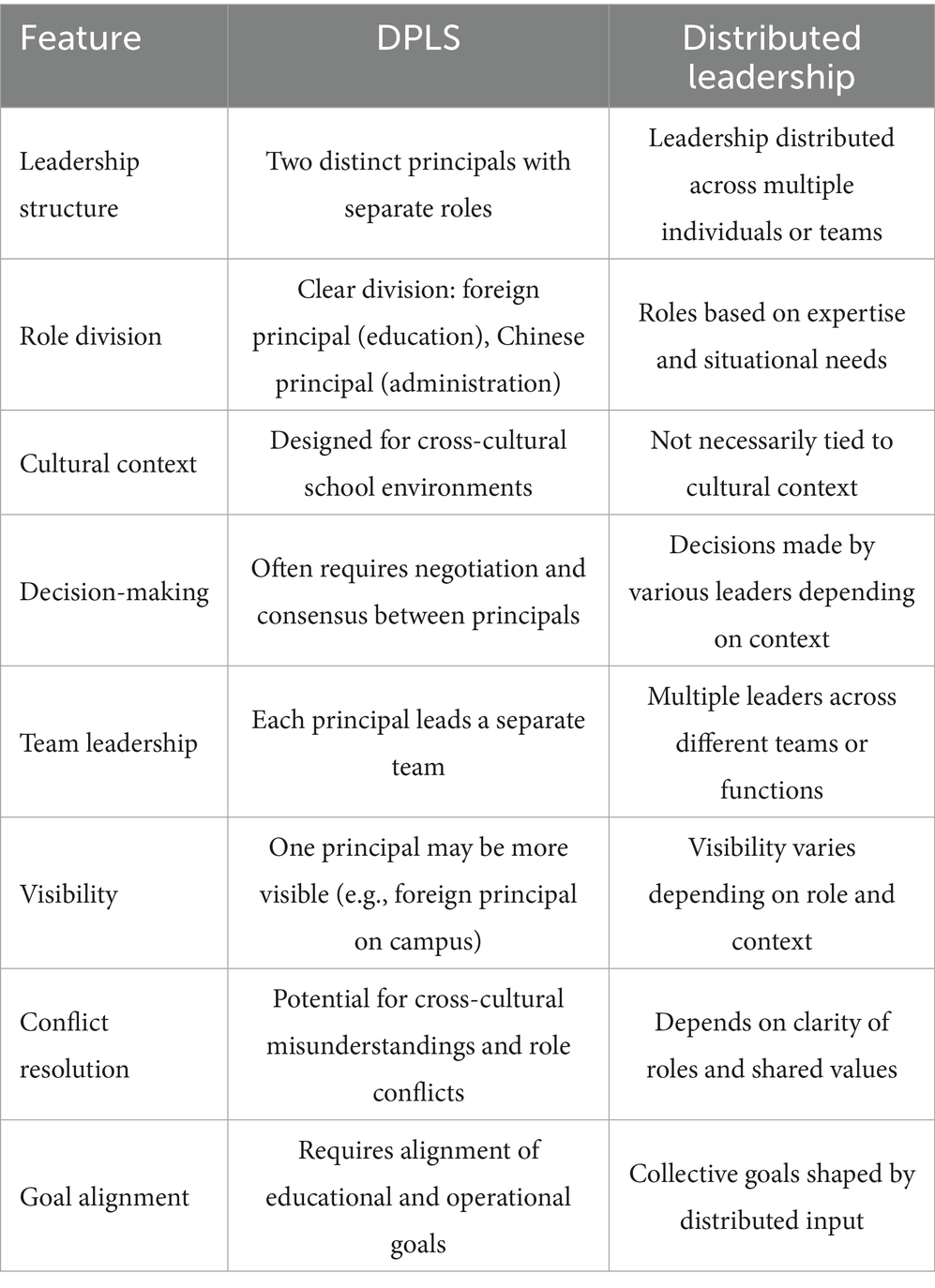

In this study, the term “Dual principal leadership structure” is used to refer to a principal accountability system jointly formed by one executive principal, who is a local, and a foreign principal, who is a foreigner (Figure 1). In some contexts, the executive principal may also be referred to as the host country principal or executive manager, while the foreign principal may be referred to as the academic principal. The Chinese executive principal is typically a person familiar with the local context, working as the CEO of the school, mainly responsible for the school’s basic operational management, financial management, human resources management, and administrative affairs, including relations with the local government education bureau. While the foreign principal is a foreigner experienced in international education and schools’ management, generally responsible for the management of the international curriculum, and foreign staff. The two principals complement and balance each other, jointly leading and managing all school affairs while remaining accountable to the school’s board and owners.

Dual management logic in private schools

As to Hayden and Thompson’s (2013), international schools across the globe can be broadly categorized into three types. Traditional international schools of type A serve children of diplomats and families who live overseas for an extended period of time, offering education to meet their basic needs and are run on non-profit; the second type, Type B, ideological international schools, are established with the goal of advancing an international viewpoint through their curricula. However, the landscape of foreign schools has seen substantial changes recently due to the emergence of Type C, or non-traditional schools. They are privately owned and run with the intention of creating profit for their owners. These schools are viewed as profitable businesses by investors. Chain schools run by for-profit businesses have become more prevalent as a result of the rise in for-profit international schools (Hayden and Thompson, 2013).

International schools are truly private organizations that primarily operate through student tuition revenue (Hayden and Thompson, 2008). These schools need to be financially self-sufficient and must comply with the laws of the host country while operating in their unique ways (Pan and Chen, 2021). At the same time, they must maintain the quality of their education in order to attract more parents on the market.

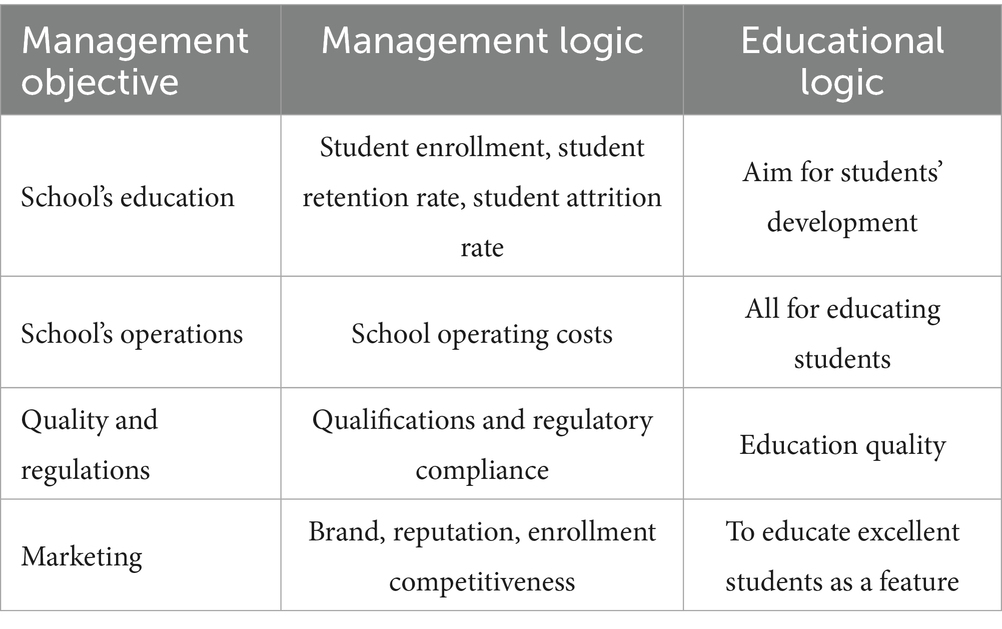

Private schools’ leaders have two different logics in the process of managing a school: management logic and educational logic. If either side is overly dominant, it will have a negative impact on the development of such schools (Ozga, 2009).

These two different logics are also the different positional logics of the two principals in the dual principal leadership structure (Table 1). Undeniably, the for-profit nature of these private schools endows them with the operational characteristics of commercial companies, thereby imparting their leaders, the principals, with responsibilities similar to those for a CEO. However, most educators with a passion for education and a sense of responsibility do not appreciate the influence of these commercial factors (Liu, 2022). For example, in Malaysia, another thriving market for commercialized international schools, the foreign principals of these schools frequently question whether they are working for a company or for education (Bailey and Gibson, 2019).

In other Asian regions, such as Thailand and Singapore, the situation is generally similar. The foreign principals of international schools are challenged with the commercial components on campus (Machin, 2014). They feel that “business manager is challenging the authority of the principal.” Some consider this beneficial as they are pushed to minimize their responsibilities, allowing them to focus completely on the area where principals feel most professionally comfortable—the field of educational leadership. Research has also indicated that young principals may have more idealism about education and often have a higher perception of these non-educational commercial features. Less experienced principals with fewer than 5 years in a principal post seemed to find the barrier between the educational and commercial domains more permeable (Murphy and Cuban, 1990; Machin, 2014).

Private education and international schools in Mainland China

The emergence of private schools in China can be related to several factors, such as the country’s economic changes that have resulted in increased prosperity, a shortage of formal public schools, and a growing variety of educational needs (Postiglione, 2006). In the past, the state-owned system in China prohibited the establishment of private institutions, as per Lin (2006). In the early 1990s, China’s confirmation of its dedication to reform and opening up resulted in the explosive growth of private education, the middle class’s impact on education became apparent (Liu, 2016).

With the significant boost that economic reforms and opening up brought to China, the domestic middle-class population began to emerge and grow. A small number of schools, known as “key schools,” and the emergence of a large number of elite private schools in the 1990s responded to the new middle class’s demand for high-quality education. Clearly, these schools were only affordable to the middle class. At that time, the parents who were able to send their children to these elite private schools were mostly business proprietors, private entrepreneurs, state company managers, government officials, urban white-collar professionals, and overseas Chinese conducting business in China (Lin, 2006).

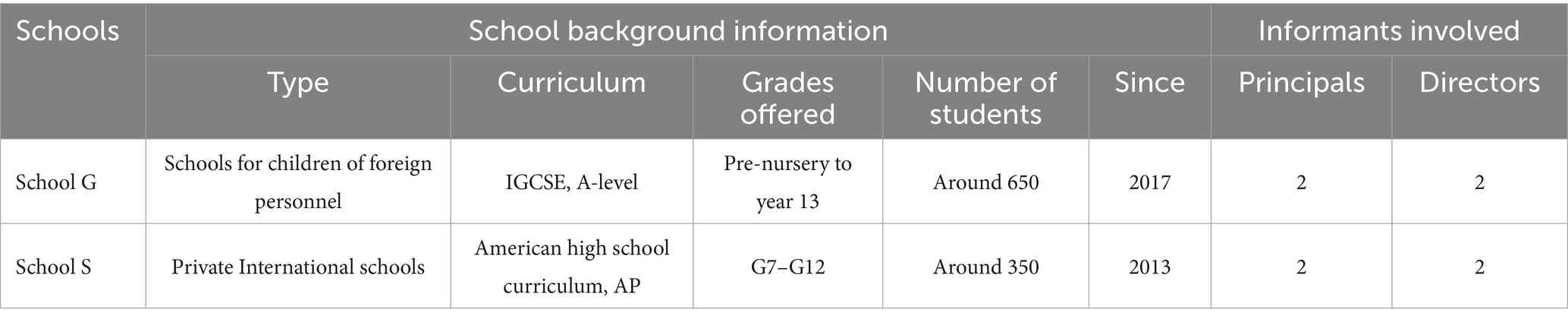

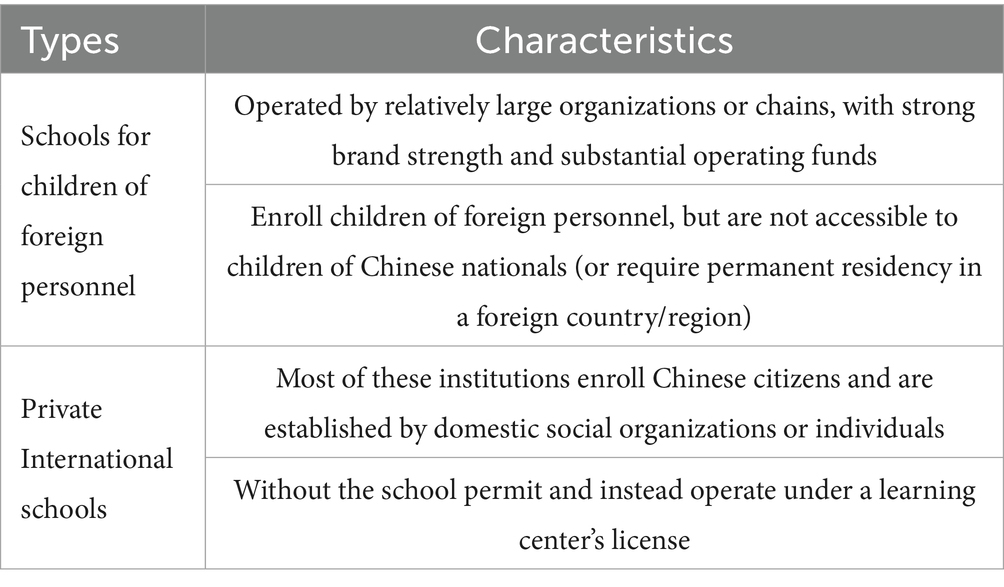

These days, an increasing number of families are capable of sending their children abroad for higher education. This trend has created a demand for more expensive educational options, leading to the establishment of international schools. These schools charge higher fees and provide a more “premium” education for families with the financial capability to afford it. The geographical distribution of private international schools is positively correlated with the economic situation (Hayden and Thompson, 2013). In Mainland China, first-tier cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen have high levels of economic development, leading to a higher demand for international schools (Liu, 2016). The tuition fees of international schools in these four cities have reached the top level globally. The average tuition fee for international schools worldwide is $8,623 USD, but there are also varying gaps. For example, the annual average tuition fee in India is $3,195 USD, in Malaysia it is $6,318 USD, and in China it is as high as $16,340 USD (Miao and Qu, 2022). The diversity of international schools in Mainland China is reflected in their choices of different international curricula in education. Apart from the more common International Baccalaureate (IB) program, mainstream schools also adopt “British” or “American” curricula, as well as the Canadian BC curriculum. Currently, many schools are offering a mix of various curricula to attract more families for enrollment advantages (Liu, 2016). These international schools are promoting the internationalization of education in China and meeting diverse educational needs. The human-centered management, cultivation of students’ global citizenship literacy, and other advanced concepts and high-quality services in international schools could have positive implications and applied in public schools in China to enhance the quality and standard of domestic education (Liu and Apple, 2023; Wu and Koh, 2022). Based on official definitions, the mainstream types of international schools in Mainland China fall into two categories: schools for children of foreign personnel and private international schools (Miao and Qu, 2022). Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of these two types, which together represent the dominant forms of international schooling in the Mainland context.

Table 2. Mainstream types of international schools in Mainland China (based on official definitions).

However, the quality of these private international schools in China varies greatly. The main issues include school operation motivations are questionable, focus too much on profit motives, lack of standards for the quality of international education, high staff turnover and even admissions of students who do not meet the requirements in order to collect high fees. Additionally, conflicts in education and management philosophies may arise between the management and investors of international schools. “Over-commercialization” may be the reason behind these issues (Liu, 2016; Liu, 2022).

Methodology

In this study, the researcher aims to discover the problems and challenges within the dual principal leadership structure of international schools, in order to develop strategies for enhancement and improvement of its implementation. Qualitative research begins with the utilization of explanatory/theoretical frameworks, aiming to make sense of individual or collective attributions to social or human issues (Creswell, 2013; Urquhart, 2022). Qualitative research is suitable for in-depth exploration and conclusion derivation in studies with small sample sizes. Only through qualitative interviews and participation can we unlock subjective meanings, while allowing us to have a more open and flexible design (Creswell, 2013).

The objective of this qualitative research study was to answer the following three research questions:

1) What are the features of the dual principal leadership structure in these international schools’ management? Why adopt this kind of structure?

2) What are the challenges and difficulties of the dual principal leadership structure?

3) How can we improve the dual principal leadership structure in these schools’ management?

Selection of participants and data collection

Guangzhou and Shenzhen are two cities located in Guangdong Province, and are home to the largest number of foreign nationals (including Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan residents) in Mainland China (National Bureau of Statistics, 2021). They are also the most international cities in Mainland China, giving rise to two of the most thriving markets for international education. Considering the above reasons, this study has selected two international schools from Guangzhou and Shenzhen as case schools.

In this study, they will be referred to as School G (located in Guangzhou), a group operated international school serving the children of foreign personnel. And School S (located in Shenzhen), a privately operated international school primarily serving children from Mainland Chinese families. The background information for the two case schools is shown in Table 3.

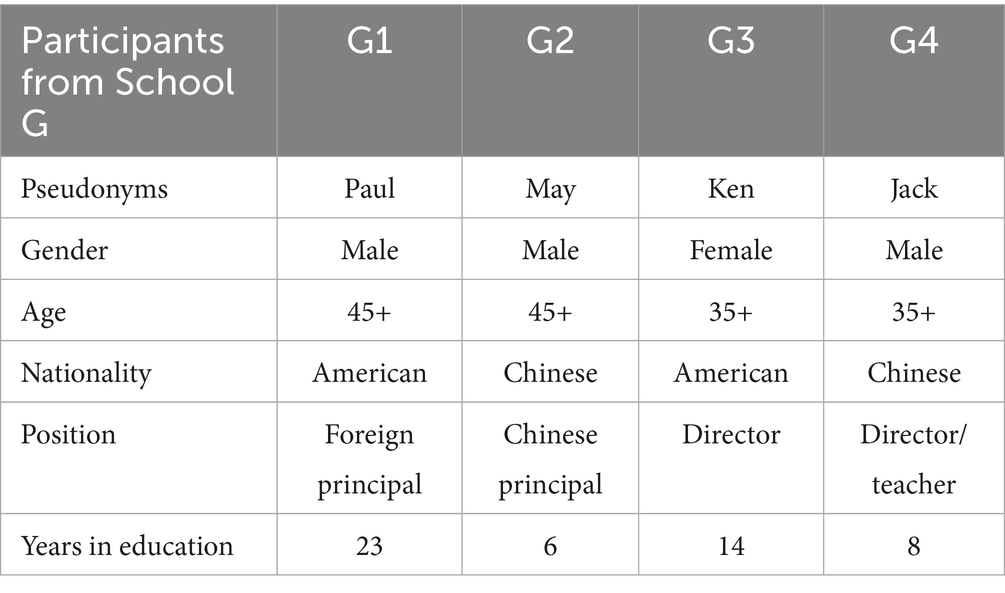

In each school, both the Chinese and foreign principals are involved in the interviews. Additionally, the perspective of an outsider allows us to consider the topic from a different angle (Lareau, 2021). School directors working under the leadership of the two principals, including individuals at the director level (one focusing more on academic management and the other on administrative management), were also invited to participate in this study in order to gain a better understanding of the research questions from their perspectives.

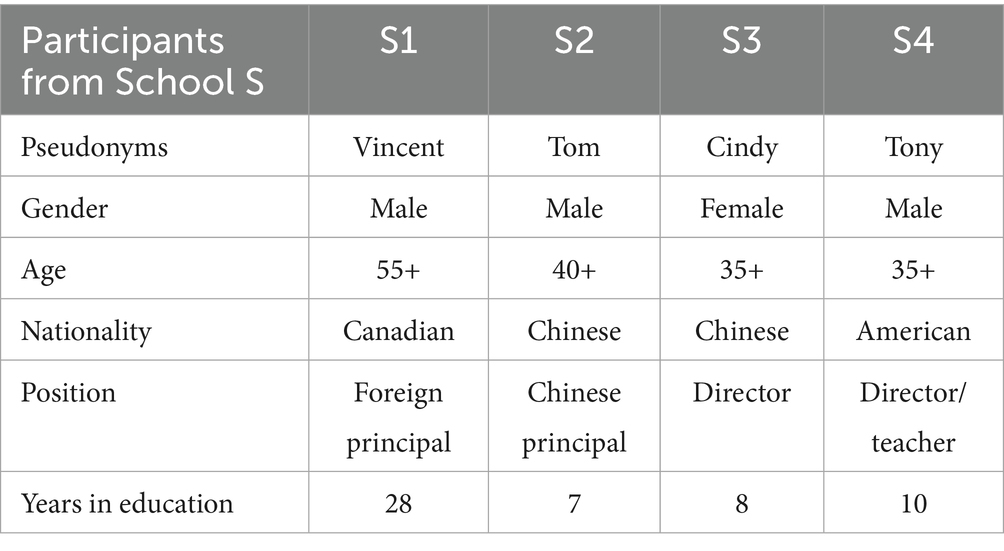

Participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure relevance to the research questions. Recruitment was conducted through direct contact with the schools, and participation was voluntary. Given that this study focuses on the leadership structure of international schools, participants were intentionally limited to core management personnel—namely, the two principals and closely affiliated directors—whose proximity to the leadership tier provides deeper insights into the research questions. Finally, four school principals and four school directors from two international schools in Guangzhou and Shenzhen are included in this study.

After obtaining ethical approval, the researcher conducted the interviews during May and June of 2024. Each interview lasted approximately 45–60 min. The interview protocol followed a semi-structured format, allowing flexibility while maintaining consistency across participants. It was divided into three phases. Firstly, a series of questions about the participants’ background information were used as opening questions to warm up and build rapport, enabling a more in-depth discussion of subsequent topics. In the second phase, the interview questions were related to their roles and responsibilities in these international schools, prompting them to discuss any conflicts and contradictions they encountered at work. In the final phase, the questions delved into more profound issues, asking participants for their own insights and suggestions, as well as their ideal dual principal leadership structure.

With participants’ knowledge and consent, all interviews were recorded to be transcribed for analysis in the next stage. Transcriptions were conducted by the researcher and cross-checked for accuracy. For interviews conducted in Chinese, translation into English was performed by the researcher and then reconfirmed with the interviewees to ensure accuracy. In addition to interviews, the researcher conducted limited on-site observations during school visits and reviewed internal documents such as organizational charts, job descriptions, and meeting minutes to triangulate data sources. The participant’s information summary is shown in Tables 4, 5.

Data analysis

During the data analysis process, each of the eight interview transcripts was analysed line by line. The researcher followed a three-level coding process: open coding to identify initial concepts, axial coding to explore relationships among categories, and selective coding to integrate and refine themes. Coding was conducted by the author using NVivo software. Saturation was reached when no new themes emerged from the interviews, which occurred after the eighth participant. To ensure trustworthiness, member checking was conducted by sharing preliminary findings with participants for feedback (Charmaz, 2014, pp. 33–198). Peer debriefing with academic colleagues helped validate interpretations and reduce researcher bias.

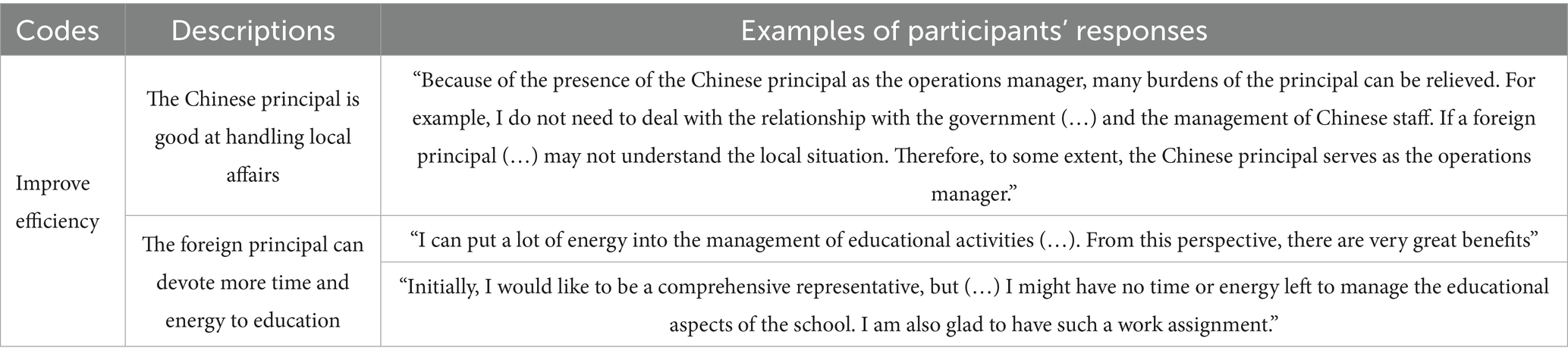

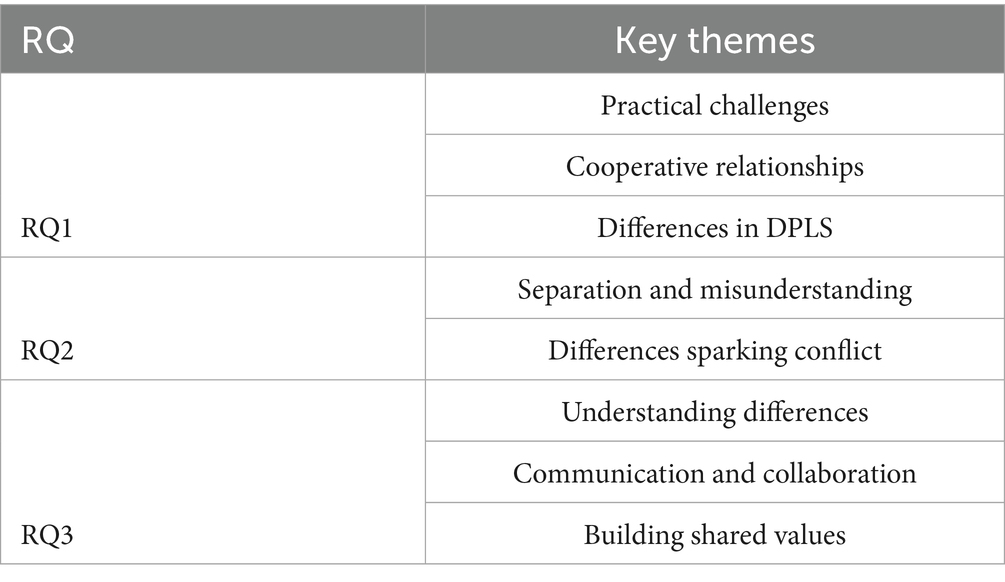

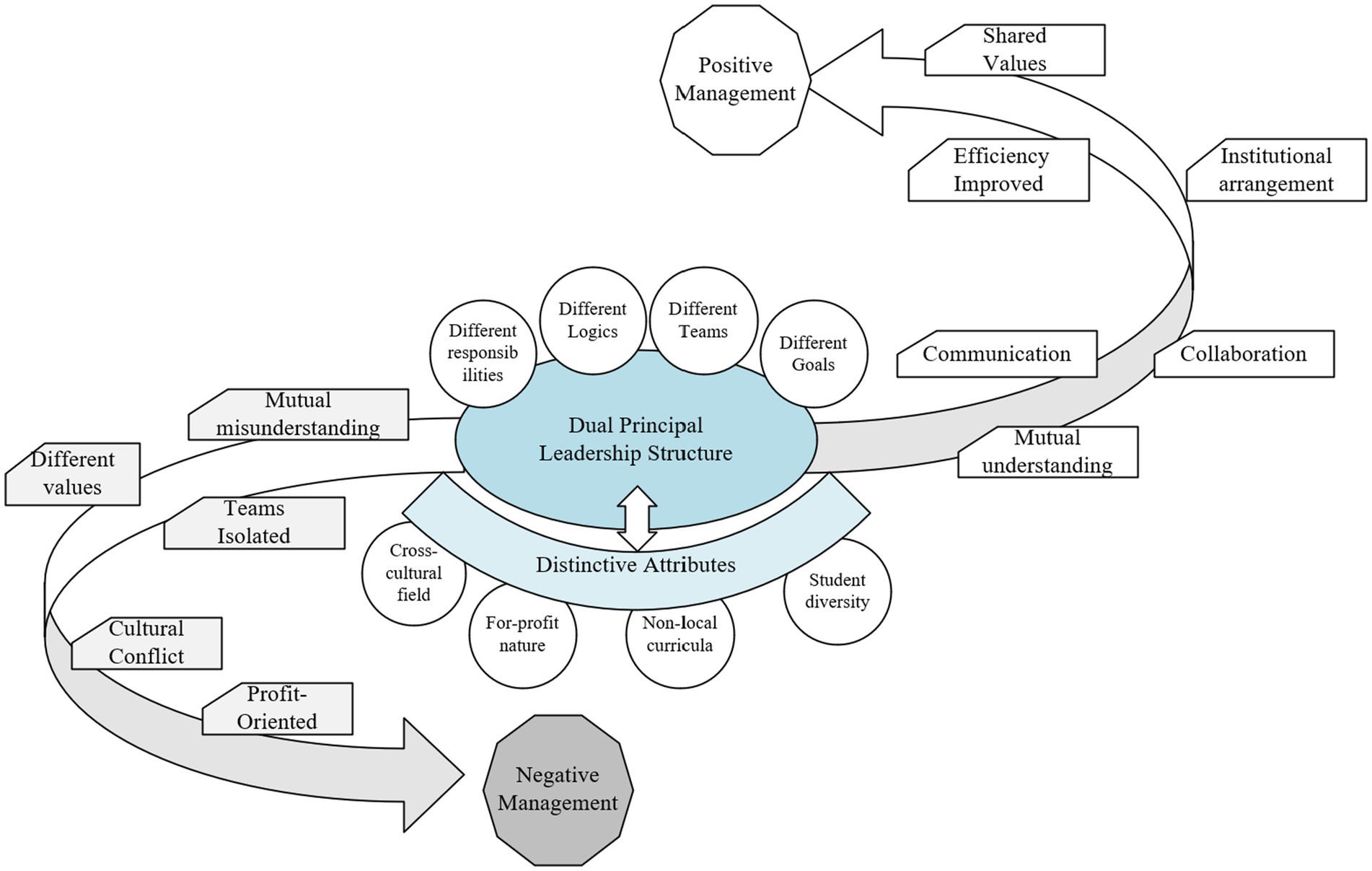

After the three levels of the coding process, the researcher discovered that these international schools have many distinctive characteristics that differ from public schools. Their students are diversified, and the schools in host countries use non-local curricula with English as the major medium of teaching. They are organizations having cross-cultural features and operate with a for-profit nature. These characters contribute to the dual principal leadership structure in school administration, resulting in different roles, logics, and work goals for both sides and their teams. Meanwhile, the various differences and distinctions lead to two different orientations in the management of these schools. Communicating, collaborating, understanding each other, and establishing institutional arrangements can help achieve shared values, improve management efficiency, and promote positive school management (Table 6).

On the other hand, misunderstandings between the two sides and different values regarding school management, in the absence of communication, may further result in isolated teams, exacerbating cultural conflict. Furthermore, these schools may gradually transform into profit-oriented institutions, leading to a negative impact on school management and overlooking educational quality.

The theoretical diagram as illustrated in Figure 2 is presented through the analysis, summarization, and relationship mapping of the codes in the data analysis, based on three-level coding of interview data. Diagrams offer a visual means to grasp the relative relationships, power structures, and directional flows within data analysis, effectively illustrating categories and their connections (Charmaz, 2006, pp. 115–121; Charmaz, 2014). Contributing factors (e.g., different response styles, logics, teams, and goals) and distinctive contextual attributes (e.g., cross-cultural field, for-profit nature, non-local curricula, student diversity) are shown as influencing the operation of the DPLS. Arrows indicate potential pathways toward negative outcomes (e.g., profit-orientation, cultural conflict, team isolation) or positive outcomes (e.g., shared values, improved efficiency, collaboration), depending on the quality of communication and institutional arrangements.

Figure 2. The theoretical diagram: dynamics of the dual principal leadership structure—positive and negative orientations.

Finding

The three main research questions in this study aim to discover the characteristics of the dual principal leadership structure and the issues existing in this leadership structure in the management of international schools, from the perspectives of the main leaders within the school’s management structure, with both the two principals and the directors. The contradictions and current situation highlighted in the interviews will help mend the deficiencies present in the current leadership structure and provide suggestions for its improvement. Through the analysis of interviews on the three main research questions, the table below presents the main themes that emerged in the interviews (Table 7).

RQ1: What are the features of the dual principal leadership (DPLS) in these international schools’ management? Why adopt this structure?

For schools management issues in reality

Although the DPLS has subtle differences in their practical operation, the reason why these schools adopt this leadership structure is to solve the problems in their daily management.

These international schools are called “international” is mainly because the education they offer belongs to a curriculum different from that of the host country, using English as the primary medium of instruction (Hayden and Thompson, 2013). The foreign principal is mainly responsible for their own areas of expertise—curriculum development, educational quality management, and management of foreign teachers. The Chinese principal spends most of their time dealing with the local government and adhering to policies from the education bureau (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School S, May 2024). The Chinese principal of School S believes that “for foreigners, it is difficult to understand the “ZHONGGUOGUOQING’ (中國國情, China’s national condition), as well as the way things are done in China (Cindy, School S, Director, originally in Chinese; English translation by the author).”

Conflicts that occur between individuals or social groups separated by cultural boundaries can be considered “cross-cultural conflicts” (Murray and Avruch, 2000). In two schools, the educational staff teams have a large number of teachers from different countries, and the operation of the schools also relies on the support of local Chinese staff in administrative, human resources management, and admissions positions. Due to the diverse cultural backgrounds of the school staff, they have many differences in educational concepts and other beliefs. In both schools, the two principals are leaders in their respective roles, overseeing the teams and serving their groups as leaders (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School S, May 2024).

Furthermore, apart from the team’s cross-cultural characteristics and non-local courses and education, the interviewees also highlighted many other concerns that emphasize the need for dual principal leadership structure:

(a) A significant number of Chinese students are unfamiliar with the methods of teaching used by foreign teachers and still require support and guidance from Chinese teachers in their studies pursuits. The Chinese principal also guiding the team of Chinese teaching assistants and homeroom teachers (Cindy, School S, Director, originally in Chinese; English translation by the author).

(b) Chinese parents have stronger demands, and they have expectations for the school’s education that they imagine (…). It is hard for foreign teachers to answer calls after work (Tom, School S, Chinese Principal, originally in Chinese; English translation by the author).

(c) The education industry is not fully open to foreign capital in many countries and regions (…) like China, does not allow foreign capital to operate schools independently. They must operate jointly with capital within China. Sometimes the two principals represent the voices of the two investor groups (Vincent, School S, Foreign Principal).

(d) Schools like ours are living in the reality (.) we need the profit for survival. Therefore, it is necessary to have a steward in charge of supervising the account book (May, School G, Chinese Principal, originally in Chinese; English translation by the author).

(e) We need local employees to help with the operation, while foreign employees are needed to look after education and instruction. The division of labor between the two is very clear (.). They are more like the leaders of two teams, with the Chinese principal leading the administrative and logistical team, and the foreign principal leading the teacher team (Ken, School G, Director).

(f) I am happy to have such a workload distribution. I do not need to spend a lot of time meeting with local governments (.) I have more energy to focus on the education and teaching (Paul, School G, Foreign Principal).

On the stage or behind the scene: differences in DPLS between the two schools

In School G, although there is no specific position of “Chinese Principal” in the management structure, there is actually a leader (referred to as the Chief Executive Officer) behind the scenes responsible for the administrative and operational work on campus. The Chinese Principal, May, spends most of the time working at the group’s headquarters in the city center. The foreign principal is the direct leader on campus for most of the time, teachers can still feel the pressure and limitations from the Chinese executive officer. This structural distinction, evident in whether the role of the Chinese Principal is positioned on the stage or behind the scenes, stems from the market positioning differences between the two case schools. School G is more inclined to project its highly internationalized elements to the market, whereas School S seeks to present to parents a coexistence of both Chinese and foreign elements (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School G, May 2024).

Jack mentioned, “We can feel that the foreign principal does not have absolute power over campus affairs, and many decisions always involve the participation of the other side. This issue was more pronounced during the pandemic (Jack, School G, Director, originally in Chinese; English translation by the author).” Ken pointed out, “Both sides need to consider each other’s situations, which adds complexity to many issues (Ken, School G, Director).” Paul, the foreign principal of School G, pointed out,

“Many localized factors do need to be handled, such as the positions like foreign affairs officers in international schools to handle issues such as visas for foreign staff. The ‘Chinese principal’ you mentioned is like the highest-level ‘local affairs officer’ dealing with the localization of school operations.”

In School S, the offices of the two principals are arranged next door to each other, which leads to more opportunities for communication, making the DPLS more apparent (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School S, May 2024). The Chinese principal is involved in more decisions on campus and has a greater influence, perhaps because they have more local students and parents. Of course, such an arrangement also makes the school’s management work more “troublesome” or “exhausting.” Cindy pointed this out:

“One of the principals holds the leadership authority in education, while the other holds the leadership authority in school administration. Many affairs need the merging of both aspects. Sometimes we need to make many adjustments based on their two different ideas. There have also been cases where the opposition from one side has resulted to the entire plan being unable to be done (Cindy, School S, Director, originally in Chinese; English translation by the author).”

RQ2: What are the challenges and difficulties of the DPLS?

Separation and misunderstanding

Two principals hold two different positions, leading their respective teams responsible for particular parts of the institution. Most of the Chinese staff do not have summer or winter holidays and work long hours on weekdays, especially in the boarding school, School S. It is not uncommon for them to handle campus situations and reply to messages from Chinese leaders after work. In contrast, the vacation time and after-work hours for foreign teachers are better safeguarded. There is also a significant difference in salary between the two teams.

In both schools, Chinese and foreign staff form relatively independent teams under the DPLS, each with their own considerations when participating in school work. For example, Chinese staff consider it irresponsible for foreign teachers to not respond to messages after school, and foreign teachers feel that their Chinese colleagues are not sufficiently supportive. Ken even believes that sometimes his local coworkers may use government policy as an excuse for not providing support, letting them know that some things cannot be done. He mentioned,

“Sometimes we do not know whether some demands come from government department requirements or are due to operational considerations (…) the executive team is more dominant (Ken, School G, Director).”

During the interviews, the Chinese principals and the administrative teams they led were more focused on how to maintain smooth school operations. They emphasized more on the “reasonable,” “flexible,” and “realistic conditions.” On the other hand, the foreign principals and the teachers seemed to place more emphasis on their educational principles. The two principals hold similar points of view when it comes to defending the interests of their own groups, viewing it as an expression of their power (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School G, May 2024). Paul stated that when disputes arise, he would provide opinions from an educational professional perspective.

“If I choose to compromise every time when the dispute arises, then I would also lose my authority to lead my team (Paul, School G, Foreign Principal).”

Differences lead to conflicts

Both principals share a common goal: they are committed to the development of the school through collaborative efforts with their respective teams. However, in their daily duties, the two positions follow different directions. The executive principal needs to be careful keeper of the school account books, strictly monitoring the school’s income and expenses and focusing more on the “commercial” and “management” elements. On the other side, the foreign principals need to thrive in their areas of expertise—leading the teaching team to provide high-quality education, enabling students to achieve better academic outcomes, and guaranteeing a good campus experience for both students and parents.

During the interviews at School G, the interviewees mentioned some details about conflicts caused by different goals and logic in the work of the two teams. For example, the goal of the admissions team is to recruit as many students as possible for the school. They may interpret concerns from children and their parents about the school as a lack of “good service” provided by the teaching team. Conversely, the teaching team may also view the existence of certain students with poor academic performance within the school as a mistake made by the admissions team (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School G, May 2024).

In School S, over a period of 7 years, the position of foreign principal has been held by three different principals. Two directors from S School plainly believed that the school had many “commercial” features in its management; they believe that the Chinese principal and the foreign principal have distinct emphases on their separate positions and their teams, which is one of the key reasons for the disagreement. Cindy, who served as a principal assistant in School S and assisted three foreign principals of the school. Cindy noted that she had encountered a foreign principal who indicated that he struggled to play the “mascot” role (serving as a symbolic representation of the school’s international character) for school marketing and recruitment throughout the majority of his working hours (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School S, May 2024). Tony, who has worked in an administrative role in School S and also served as an assistant in the education department, remarked that he could feel the existence of two different teams with two different directions and logics at work. He believed,

“Sometimes you can feel that we are on one ship with two captains (Tony, School S, Director).”

RQ3: How can we improve the DPLS in these schools’ management?

Understanding differences

If the two principals can better understand each other’s responsibilities and the challenges and pressures they face in their roles, they can better understand each other’s difficulties from each other’s perspectives.

This point is almost a consensus reached by all the interviewees. Beyond the differences in the responsibilities of the two principals, it is also important how they lead their teams to understand each other’s cultural and logical differences. Vincent believes that it is important for foreign education workers to understand the local culture and national conditions. He stated,

“If some issues indeed conform to the local conditions and rules, then certain changes can be made instead of insisting on the original idea, leading to a confrontational situation. Many Chinese employees understand what we are facing better (Vincent, School S, Foreign Principal).”

Communication and collaboration

Communication is an important step in understanding differences and achieving collaboration. Vincent believes that taking the initiative to communicate and address misunderstandings is also important because these conflicts hinder the team’s progress. Vincent used a metaphor to describe the situation:

“The two principals and two teams are like two parallel trains, carrying the entire school together. If the two tracks are no longer parallel (.) I am willing to adjust the tracks (proactively resolve conflicts) (Vincent, School S, Foreign Principal).”

In School S, the offices of the Chinese principal and the foreign principal are adjacent to each other. The teams on both sides will have weekly meetings to discuss campus affairs (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School S, May 2024). Tom pointed out that many issues can be resolved in a timely manner through communication. Both sides express their views and suggestions on campus affairs in meetings. Although there may still be differences in understanding, this is positive for the school’s operations. According to Tony’s campus experience, he believes that the school is a place where “rumors” are more likely to occur, not only because of the large number of faculty and staff from different cultural backgrounds but also because students are active spreaders of rumors. “For many evaluations of teachers or school arrangements, mutual trust and collaboration between different positions can only be achieved through timely communication (Tony, School S, Director).”

Shared values

In the interviews, four principals discussed the importance of shared values and a common vision for development. Undoubtedly, it is very important whether the two principals and the teams they lead can reach a common understanding and values. Participants pointed out their agreement with the necessity of shared values, despite their varied definitions. Some believe that shared values need to be created at the beginning of team creation, while others consider it something that needs to be gained through mutual understanding in actual work. In conclusion, if managers and teachers at the school do not have values that are higher than commercial logic, the quality of education and sustainable development of the school may be seriously affected (Researcher’s fieldnotes, School S, June 2024).

Paul believed that there should be sufficient communication and groundwork for a common theory at the construction of the DPLS. Vincent believed,

“We are here helping our students, and market-oriented operations are related to every school employee. As long as it does not affect the quality of school education, I do not think there is any harm. Our ultimate goal needs to remain the same, that is, to commit to better education (Vincent, School S, Foreign Principal).”

Jack said, “In the end, everything should return to education itself and student development. The product we provide to the market is the school’s education, so the quality of the school’s education is particularly crucial (Jack, School G, Director, originally in Chinese; English translation by the author).”

Discussion

DPLS: a dual-core solution in the complex field

In contrast to distributed leadership, which emphasizes the flexible allocation of leadership responsibilities across multiple actors according to expertise and situational demands, the DPLS represents a more fixed, role-differentiated, and culturally embedded leadership model (Printy and Liu, 2020). This distinction is particularly salient in the context of international schools, where the integration of global pedagogical standards with local governance requirements necessitates a dual-core leadership arrangement. Compared to distributed leadership, which emphasizes the flexible distribution of leadership responsibilities across various individuals based on expertise and context, DPLS presents a more structured and culturally anchored leadership model. This dual-core structure is particularly suited to international schools operating in cross-cultural environments, where the integration of global educational standards and local governance requirements necessitates specialized leadership roles (Gümüş et al., 2020; Ertem, 2021).

Through the analysis of the three main research questions, we understand the necessity of the DPLS in the management of these international schools. The hiring of foreign principals is reasonable, as they are the leaders of the international curriculum in education and market branding, overseeing the international curriculum in schools and the foreign teaching team behind it. However, the challenge and difficulty come from the fact that these institutions need to face local cultural restrictions and relatively rigorous school laws in China. Moreover, the operation and management of the school cannot be separated from the participation of local staff, who, together with foreign staff, create two different cultural teams inside the campus (Zhang, 2016). The parents and students of the school also have diverse characteristics, such as some leaning towards the strict requirements of traditional Chinese parents on student performance, while others hope that students in international schools can have less test pressure and develop in all aspects.

Furthermore, these institutions are not public schools that exist for the public good; their funding for organizational operation and growth comes almost entirely from student tuition payments (Hayden and Thompson, 2008; Miao and Qu, 2022). For the investors behind the schools, whether the school will turn a profit in its operations is a major concern. Undoubtedly, meeting the different “needs” of parents and kids is something that needs to be considered seriously in the process of school operations. A Chinese leader who comprehends the local conditions, can lead a team of local people, is familiar with the concepts of Chinese parents, and has experience in managing Chinese firms has effectively filled the gap in cross-cultural management (Table 8).

Differences and similarities: rooted in market orientation?

In this study, the two case schools are classified as different types of schools according to the definition of the Chinese official education management department. The School G is for children of foreign personnel, and their students must be foreigners or Chinese citizens with foreign status, including residents of Hong Kong, Macao, or Taiwan. The School S is a private international school with a mix of foreign and local Chinese students, with the majority being Chinese citizens.

It is almost certain that the power of the Chinese principals is bigger at both schools. They also have higher work stability and have closer relationships with the school investors. However, there are differences in the DPLS between the two schools. This is reflected in the fact that the Chinese principal of School G is generally “behind the scenes,” often not in the school office and not engaged in student activities, but the staff are aware that the Chinese principal is the final decision-maker. School G is more willing to present a more “international” image to the market and foreign parents.

On the other hand, the Chinese principal of School S is more often “on the stage,” leading the team of homeroom teachers to participate in parent-school communication and being more involved in school events. The foreign principal of School S is more open to taking on some role-playing responsibilities based on the instructions of the Chinese principal at specific events. They intentionally make their parents aware that although the school uses foreign curriculum and English as a medium of teaching, their education still retains positive components of Chinese schools and maintains reasonably strong moral and educational criteria. The differences seem to be for the same reason: to showcase their distinctive features to their potential customers in the market rather than improve their education.

Improvement and enhancement for DPLS

Different job responsibilities have led to inevitable collaboration difficulties and challenges between the two principals and the teams they lead. Based on the responses of the interviewees to Research Question Three, we can understand some potential strategies and methods to improve and enhance this structure in the future.

First, many interviewees believed that communication is an important method to eliminate misunderstandings and build trust between both parties. As one interviewee mentioned, the shared view might be emphasized at the beginning of team building, and it is important to place individuals with similar values in the team or leadership positions. However, people’s attitudes are always changeable. Perhaps integrating “communication” and “collaboration” into the school’s management arrangements is the most reliable solution. We can see that the DPLS at School S created a more collaborative relationship between both sides. Apart from the school’s intention to incorporate more elements of Chinese education, we have reason to believe that this also reflects sound institutional arrangements in School S that actively facilitate communication between the two sides. In School S, both teams hold weekly meetings, and the offices of the two leaders are located only 10 steps apart. Such arrangements, at the institutional level, are undoubtedly effective in fostering communication and collaboration across teams.

The for-profit nature and disagreements among teams may not be absolute elements affecting the overall development of a school. Excellent educational quality in a school can boost brand recognition and reputation, promoting school development and generating a virtuous cycle. It is crucial for the two leaders and their teams to recognize that they are not independently completing their individual obligations (school profitability and maintaining educational quality), but rather, working together towards the overall achievement of the school.

Limitation

In this study, eight participants from two international schools were included in the data collection. The number of participants may limit the study’s generalizability. However, the primary focus of this study is not on generalizability, but rather on researching the leadership structure of such schools. Secondly, according to the definition of the Chinese government, there are three types of international schools in Mainland China (Miao and Qu, 2022). In addition to the schools for children of foreign personnel (School G) and private international schools (School S) in this study, another interesting type is the international curriculum department or class established within public schools. This type of department typically collaborates with external educational organizations to operate the curriculum. Do these schools also have the structure in their management? Due to limitations in resources, this study was unable to research and compare the three types of international schools in Mainland China. As the research involves their respective schools’ leadership structures, exposing their own shortcomings, the researcher may have difficulty ensuring that all statements in interviews were accurate. It must be acknowledged that there may be certain biases or reservations present.

Conclusion

After the implementation of the reform and opening-up policy, China has become more involved in the process of economic globalization. These changes have contributed to the development of international schools, a new type of educational institution, in Mainland China. However, as the number of international schools in Mainland China has grown significantly, the public is questioning their educational quality. Some argue that these schools cater only to the wealthy class in China, transferring their economic capital to cultural capital for their descendants, as proposed by Bourdieu (1986).

These schools being a relatively new type of educational institution in Mainland China, have a short history. Research on these schools is still limited, with many gaps in the existing literature. This study focuses on the dual principal leadership structure of these schools as the starting point, based on qualitative data collected through semi-structured interviews and field studies. By investigating the “why” and “what” of this structure, the study aims to uncover the characteristics of governance in these schools, further investigate the challenges and difficulties faced by this structure in practical school management, provide potential enhancement strategies and improvement recommendations, and identify the issues that these schools need to address in Mainland China.

These findings invite us to pay more attention to the management status of these for-profit schools and consider how to maintain the balance between educational quality and profitability in the operation of these for-profit international schools. At the same time, it is likely to provide suggestions for the stakeholders, practitioners in these international schools on how, in a complex cross-cultural campus environment, to achieve positive school governance through the design of institutional arrangements. It may also enable educational policymakers and scholars to fully understand the situation of these schools in Mainland China, introduce more reasonable policy decisions, and further research this type of school.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JL: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Validation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bailey, L., and Gibson, M. T. (2019). International school principals: routes to headship and key challenges of their role. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 48, 1007–1025. doi: 10.1177/1741143219884686

Bell, D. A. (2016). The China model: political meritocracy and the limits of democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. ed. J. Richardson (New York: Greenwood Press).

Bunnell, T. (2008). The Yew Chung model of dual culture co-principalship: a unique form of distributed leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 11, 191–210. doi: 10.1080/13603120701721813

Bunnell, T., Fertig, M., and James, C. (2016). What is international about international schools? An institutional legitimacy perspective. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 42, 408–423. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2016.1195735

Chairez, C. C. (2022). Principal perspectives on the dual roles of manager and instructional leader. Walden dissertations and doctoral studies. US: Walden University.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. UK: Sage Publications Ltd.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Cunningham, C., Zhang, W., Striepe, M., and Rhodes, D. (2022). Dual leadership in Chinese schools challenges executive principalships as best fit for 21st century educational development. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 89:531:102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102531

Eckman, E., and Kelber, S. T. (2009). The co-principalship: an alternative to the traditional Principalship. Planning and changing. 40, 86–102. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/213081876.pdf (Accessed July 1, 2024).

Ertem, H. Y. (2021). Relationship of school leadership with school outcomes: a meta-analysis study. Int. Educ. Stud. 14:31. doi: 10.5539/ies.v14n5p31

Fisher, D. (2021). Educational leadership and the impact of societal culture on effective practices. J. Res. Int. Educ. 20, 134–153. doi: 10.1177/14752409211032531

Gronn, P., and Hamilton, A. (2004). A bit more life in the leadership? Co-principalship as distributed leadership practice. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 3, 3–35. doi: 10.1076/lpos.3.1.3.27842

Gümüş, S., Arar, K., and Oplatka, I. (2020). Review of international research on school leadership for social justice, equity and diversity. J. Educ. Adm. Hist. 53, 81–99. doi: 10.1080/00220620.2020.1862767

Hayden, M, and Thompson, John Jeffrey and for I (2008). International Schools: Growth and Influence. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific & Cultural Organization.

Hayden, M., and Thompson, J. (2013). “International schools: antecedents, current issues and metaphors for the future” in International education and schools: moving beyond the first 40years. ed. R. Pearce (London: Bloomsbury Academic), 3–24.

Lareau, A (2021). Listening to people: a practical guide to interviewing, participant observation, data analysis, and writing it all up. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press.

Lin, J. (2006). Educational stratification and the new middle class. In Education and social change in China: Inequality in a market economy Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe. (pp. 179–198).

Liu, S. (2016). Becoming international: High school choices and educational experiences of Chinese students who choose to go to US colleges. PhD Thesis. Madison, US: The University of Wisconsin.

Liu, L. (2022). Opportunities and challenges for private education in china: a policy review of the Revisions to Implementation regulations of the private education promotion law of the People’s Republic of China. ECNU Rev. Educ. 6:209653112211208. doi: 10.1177/20965311221120829

Liu, S. Z., and Apple, M. W. (2023). Reconstructing choice: parental choice of internationally-oriented “public” high schools in China. Crit. Stud. Educ. 65, 217–234. doi: 10.1080/17508487.2023.2249958

Machin, D. (2014). Professional educator or professional manager? The contested role of the for-profit international school principal. J. Res. Int. Educ. 13, 19–29. doi: 10.1177/1475240914521347

Masters, Y. (2013). Co-principalship: are two heads better than one? Int. J. Cross Discipl. Subj. Educ. 4, 1213–1221. doi: 10.20533/ijcdse.2042.6364.2013.0170

Miao, L., and Qu, M. (2022). Global development of international schools and Chinese practices. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press.

Murphy, J. T., and Cuban, L. (1990). The managerial imperative and the practice of leadership in schools. Hist. Educ. Q. 30:268. doi: 10.2307/368679

Murray, J. S., and Avruch, K. (2000). Culture and conflict resolution. Contemp. Sociol. 29:643. doi: 10.2307/2654578

National Bureau of Statistics (2021) Bulletin of the seventh National Census. Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202105/t20210511_1817203.html (Accessed April 10, 2024).

Ozga, J. (2009). Governing education through data in England: from regulation to self‐evaluation. J. Educ. Policy. 24, 149–162. doi: 10.1080/02680930902733121

Pan, H. W., and Chen, W. (2021). How principal leadership facilitates teacher learning through teacher leadership: determining the critical path. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 49, 454–470. doi: 10.1177/1741143220913553

Postiglione, G. A. (2006). Education and social change in China: inequality in a market economy. Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe.

Printy, S., and Liu, Y. (2020). Distributed leadership globally: the interactive nature of principal and teacher leadership in 32 countries. Educ. Adm. Q. 57:0013161X2092654. doi: 10.1177/0013161x20926548

Shockley, R. E., and Smith, D. D. (1981). The co-principal: looking at realities. Clear. House 55, 90–93. doi: 10.1080/00098655.1981.9958220

Urquhart, C. (2022). Grounded theory for qualitative research. London: SAGE. Available at: https://digital.casalini.it/9781529766981

Wexler Eckman, E. (2006). Co-principals: Characteristics of Dual Leadership Teams. Leadership and Policy in Schools. 5, 89–107. doi: 10.1080/15700760600549596

Wu, W., and Koh, A. (2022). Being “international” differently: a comparative study of transnational approaches to international schooling in China. Educ. Rev. 74, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.1887819

Yang, D., Yang, M., and Huang, S. (2020). The development report of China’s education (2020). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press (China).

Keywords: leadership structure, principal leadership, school governance, educational leadership, international schools, private school, international schools in Mainland China, schools in China

Citation: Li J (2025) The dual principal leadership structure in international schools’ management: a study based on two schools in Mainland China. Front. Educ. 10:1683084. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1683084

Edited by:

María J. Hernández-Amorós, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Jawatir Pardosi, Mulawarman University, IndonesiaChien-Chih Chen, National Taipei University of Education, Taiwan

Copyright © 2025 Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiayi Li, bWFyay1sanlAb3V0bG9vay5jb20=

Jiayi Li

Jiayi Li